1. Introduction

Contemporary digital communication systems often employ classic technological solutions. Digital modulation families like ASK, FSK, and PSK, along with OFDM technology and its derivatives, have been in use for several decades. LoRa modulation, despite being over a decade old, is still frequently touted as a novelty in the digital communications field.

Over the past ten years, as machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) have become established in image processing, the insights gained are progressively being applied to other domains, including digital communication systems, particularly those based on the end-to-end autoencoder concept.

This paper is structured as follows.

Section 2 presents an analysis of the relevant work and outlines our motivation for investigating the end-to-end (E2E) autoencoder based on the Walsh transform.

Section 3 details the simulation results and describes the design of the E2E autoencoder within an AI-enhanced communication system.

Section 4 discusses the experimental validation of the model in a laboratory setting using an SDR-based system setup. Finally,

Section 5 concludes this paper with a summary and future perspectives.

2. Relevant Work and Motivation

In this paper, we explore an alternative approach to digital modulation and waveform designs in AI-enhanced communications systems. A key focus is on the potential benefits of transitioning from Fast Fourier Transform (FFT)-based Orthogonal Frequency Division Multiplexing [

1,

2] to other transform-based modulations that better suit specific operational conditions [

3]. The proposed improvements include greater resistance against fading, Doppler effects in channels, enhanced phase noise resistance, and a reduced peak-to-average power ratio (PAPR). We investigate the usage of the Walsh–Hadamard transform (WHT) [

4] in digital communication. The inherent simplicity of Walsh–Hadamard (WH) [

5] basis functions suggests that WH-based [

6,

7] modulation could offer reduced complexity and improved performance compared with the traditional OFDM modulation technique. Walsh functions constitute a comprehensive and orthogonal set of functions that can be employed to represent any discrete function, analogous to how trigonometric functions are utilized in the Fourier transform. Consequently, Walsh functions serve as the discrete, digital equivalent of the continuous, analog system of trigonometric functions within the unit interval. Contrasting with the continuous nature of sine and cosine functions, Walsh functions are characterized by their piecewise constant nature, assuming values of −1 and +1 exclusively on sub-intervals delineated by dyadic fractions. A notable distinction between the Fourier transform and the Hadamard transform lies in their computational requirements: the Fourier transform necessitates irrational multiplication, whereas the Hadamard transform relies on sign flips.

N. Bouassida et al. in [

8] introduced a modulation scheme based on analog Walsh–Hadamard signal processing. R. Queheille et al. in [

9] proved that the concept can work using components off the shelf and demonstrated an arbitrary waveform generator that uses Walsh transformation. P. Ferrer et al. in [

10] extended the investigation of a Walsh transformation usage in 5G applications. These approaches suggest that baseband information symbols can be modulated using the Walsh domain.

The contemporary landscape of sub-THz ultra-wideband communications reveals significant gaps, particularly with the limitations of available transceivers and the physical characteristics of the channel. The system’s response to non-linear impairments and sensitivity to environmental conditions remains a largely uncharted territory. Adaptive adjustments of critical link-level parameters, such as frequency bandwidth and the modulation and coding schemes, are necessary and must be executed more swiftly than traditional, standardized systems allow [

11]. This leads to newly developed communication system solutions that must aim not only for adaptability to dynamic conditions but also for flexibility in performance to prevent drastic communication failures under slightly degraded conditions, thus ensuring a gradual decrease in system performance [

12].

In this paper, a dual strategy that integrates Walsh signal processing with AI-driven end-to-end system adaptation responsive to channel dynamics is presented. We posit that this integrated approach facilitates flexible communication systems capable of adapting smoothly to sub-terahertz radio-propagation conditions and hardware non-linearities. This paper focuses on the synergistic adaptation of both the transmitter and receiver, employing a neural network to learn channel variations and autonomously adjust, effectively enabling system-level equalization to mitigate channel distortions. Further discussion will elaborate on our vision for leveraging AI and Walsh processing to address dynamic channel tracking and compensation in complex channel environments through end-to-end communication solutions.

During the past few years, other authors have published some interesting scientific experiments and insights in the field. T. O’Shea et al. [

13] introduced a novel DL application for the physical layer of communication systems. They conceptualized a wireless communication system as an autoencoder and advocate for a new perspective on system design as an end-to-end process, optimizing transmitter and receiver components simultaneously. A key highlight of their paper was the use of convolutional neural networks (CNNs) to classify digital modulation techniques using raw IQ samples, achieving accuracy comparable to traditional methods that rely on features designed by human experts. This approach indicates potential performance enhancements in complex communication scenarios, particularly those challenging to model mathematically.

S. Dörner et al. [

14] expanded on the E2E autoencoder concept in digital communication, demonstrating the feasibility of learning transceiver and receiver implementations as deep neural networks optimized for various differentiable end-to-end performance metrics, like the block error rate (BLER). Their real-world application using two software-defined radio (SDR) systems showcases the practicality of such systems.

Furthering this line of research, T. O’Shea et al. [

15] conducted an in-depth study on the effectiveness of DL in classifying radio signals, utilizing USRP SDR boards in a real-life setup. They found that DL methods significantly enhance the sensitivity and accuracy of radio signal identification, particularly for short-duration observations.

H. Ye et al. [

16] presented simulation results for deep learning applications in channel estimation and signal detection within OFDM communication systems. They noted the advantages of DL when dealing with complex wireless channels characterized by distortions and interferences, demonstrating neural networks’ ability to learn channel characteristics. In a subsequent study, H. Ye et al. [

17] delved into E2E communication systems using a conditional generative adversarial network (GAN) for channel modeling. This approach is particularly useful given the variable nature of channel functions depending on time and environmental conditions. Their GAN-based model facilitates E2E learning of communication systems without requiring prior channel information.

A. Felix et al. [

18] explored the integration of E2E autoencoders with OFDM modulation, highlighting how this combination can address synchronization challenges and simplify equalization over multipath channels. They also noted the model’s ability to cope with hardware imperfections.

W. Yu et al. [

19] analyzed the potential of data-driven system design and optimization in the realm of machine learning, especially with deep neural networks. They presented a study using a MIMO (multiple in–multiple out) system model, illustrating how end-to-end training of a deep neural network with a substantial number of channel samples can lead to significant system-level enhancements. This ML-based approach shows promise in outperforming traditional model-based methods for solving optimization problems.

In conclusion, the advancements in the field of digital communication, particularly through the integration of machine learning and deep learning technologies, mark a shift in how communication systems are conceptualized, designed, and implemented. The research efforts discussed in this section, ranging from the application of end-to-end autoencoder models to the exploration of neural networks for channel estimation and signal detection, demonstrate an alternative approach to solely human-engineered solutions based on tractable models. This is particularly relevant considering the sub-terahertz channel complexities discussed in this report.

This brief review highlights the shift in the scientific community over the past five years toward incorporating deep learning into RF communication systems, particularly through the use of end-to-end (E2E) autoencoder architectures. Despite these advancements, significant challenges remain. Currently, practical experiments are predominantly confined to transmitting short messages across makeshift channels using prevalent SDR systems, notably USRP SDRs. These experiments are limited to the ISM bands (2.4 GHz), utilizing low bandwidth signals (1–5 MHz), and require substantial computational resources for deep learning network deployment.

Deep learning technology’s integration into contemporary digital communication systems can be considered a breakthrough, yet it is not without its difficulties. One key issue is channel evaluation. Most research relies on static simulation results for channel modeling, ignoring the need for dynamic channel assessment in modern communication systems.

Another concern is the dependency of DL methods on the quality and volume of training datasets. Forming adequate training data for channels that change dynamically is often challenging. Without extensive and varied datasets, DL methods cannot be reliably used. Dynamic channel variations necessitate frequent neural network adaptation, which increases the computational time and energy requirements, conflicting with the demand for real-time, cost-effective hardware.

Additionally, the ISM bands (2.4 GHz, 5.7 GHz, and 6 GHz) are increasingly congested with various IoT (Internet of Things) wireless technologies. Consequently, next-generation wireless communication systems are expected to shift from MHz and GHz to THz bands, offering vast-spectrum resources for high-speed communication. This transition underscores the necessity for innovative methods and techniques for channel estimation in the terahertz bands.

A comprehensive review of the existing literature indicated that communication systems based on Walsh–Hadamard sequences represent a relatively nascent research area. Notably, a comparative analysis of error-rate performance between OFDM and Walsh–Hadamard-coded systems is currently absent from published works. Therefore, the objective of the present investigation was to evaluate the efficacy of Walsh–Hadamard coding when integrated with machine learning (ML) models for communication system design and performance characterization.

In this paper, instead of relying on the training dataset, we construct the channel model algorithmically, as described in

Section 3.1. We incorporate dynamic, time-dependent amplitude and phase changes as well as additive white Gaussian noise. Although such a model does not represent the full complexity of real-world conditions, experiments performed using software-defined radio devices show that the channel model used in the training allows for successful transmission of the signals.

3. E2E Communication System in Walsh Domain

We consider a communication system consisting of a transmitter, a channel, and a receiver. The transmitter sends a message over the channel to the receiver. Each message can be represented by a sequence of bits of length

k; thus, the number of possible messages is

M = 2k. The receiver obtains a noisy and distorted version of the message and should produce an estimate of the original message. Such a communication system can be interpreted as an autoencoder [

20]. The autoencoder approach jointly optimizes both the transmitter and receiver with data transmitted through an assumed channel model [

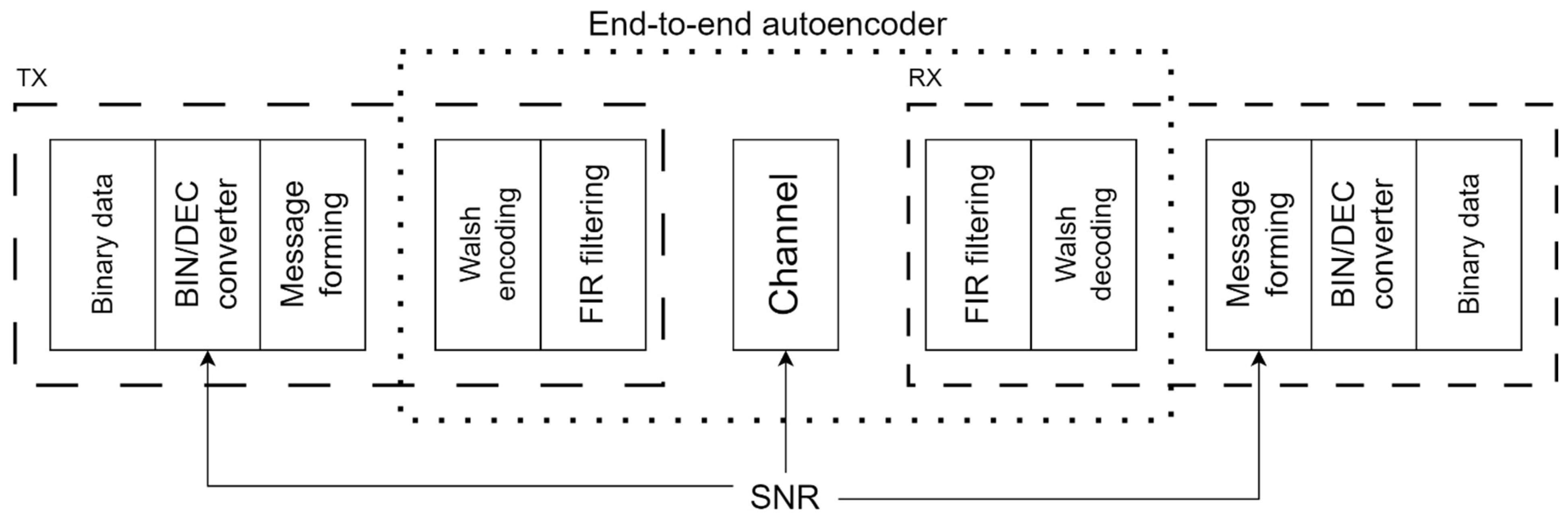

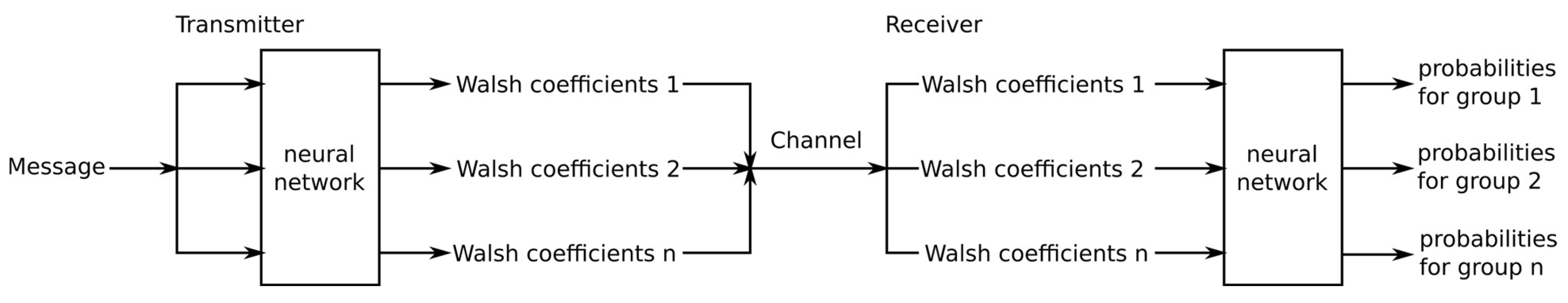

13]. The transmitter acts as an encoder network, while the receiver acts as the decoder network. The proposed Walsh-based communication system architecture used in end-to-end learning is presented in

Figure 1.

In the transmitter part, the binary data are grouped into sets of bits of length k. Those sequences are converted into a message number using a binary-to-decimal converter. The trainable transmitter neural network converts the message number to Walsh coefficients (in this article, we used 64 Walsh coefficients). After converting the Walsh coefficients into the time-domain signal, an FIR (finite impulse response) filter is used at the transmitter for bandwidth forming. The signal is sent to the channel and then to the receiver.

The receiver data are filtered using the FIR filter, converted from the time domain into Walsh coefficients, and passed to the receiver neural network. The output of the receiver neural network is the most probable message number. After decoding, a message is formed, and the data are converted back to binary form.

Similarly, as in [

14], the error rates can be improved by including a separate phase estimation neural network that predicts the complex multiplier from the time-domain signal. The signal is multiplied by this complex number before conversion to the Walsh coefficients in the receiver.

The number of bits k per transmitted message can be adapted to the state of the transmission channel. As shown in

Figure 1, the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) of the channel can be supplied to the transmitter. During training of the neural networks, both the transmitter and receiver, as well as the channel model, are on the same computer, and the SNR can be supplied externally as a parameter. For actual transmission of the signals using hardware implementation, the state of the channel can be estimated by the receiver and submitted to the transmitter using a separate feedback channel.

3.1. Chanel Model

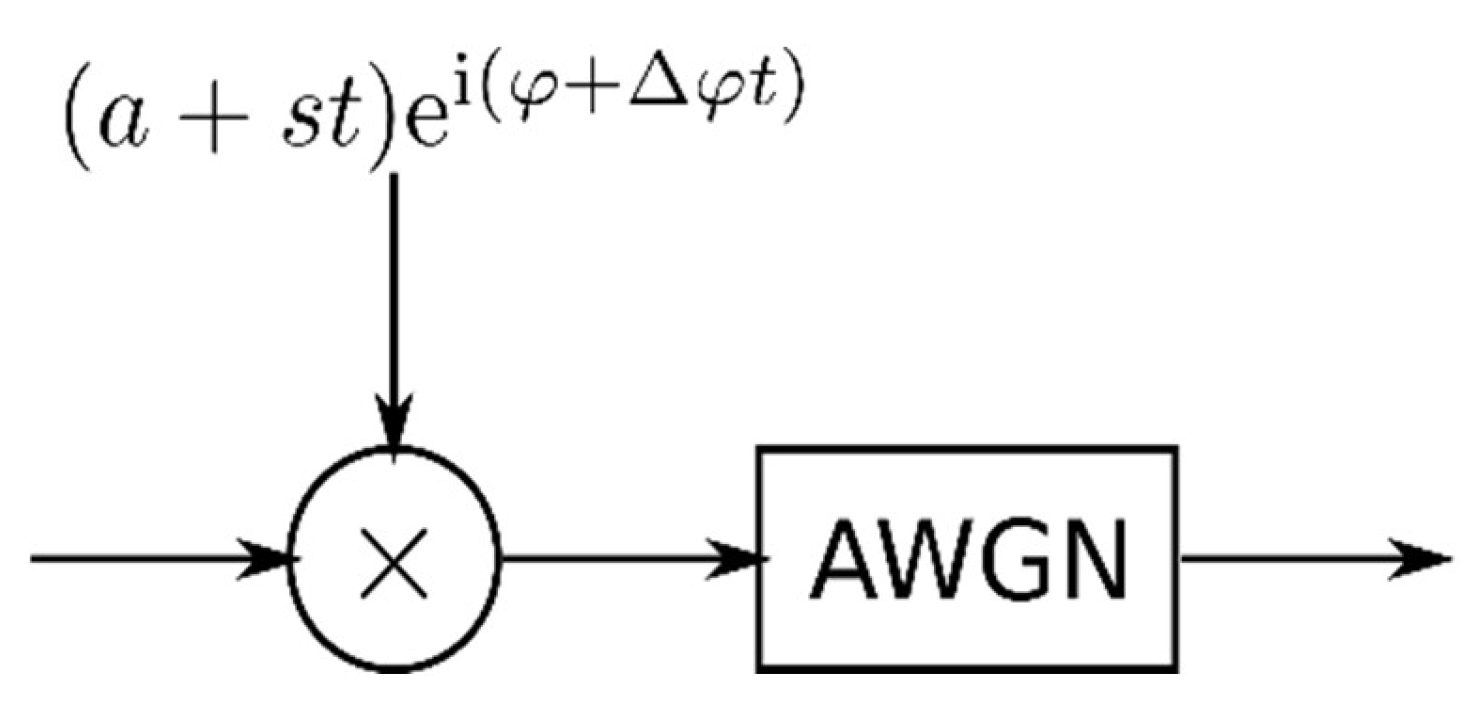

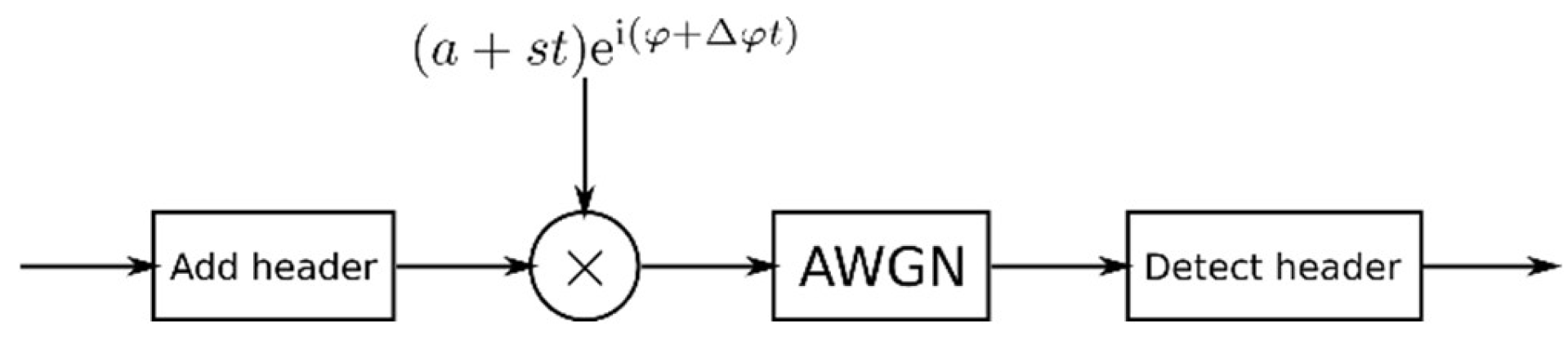

For the optimization of the end-to-end system using gradient descent, a differentiable channel model is needed. We implemented the channel shown in

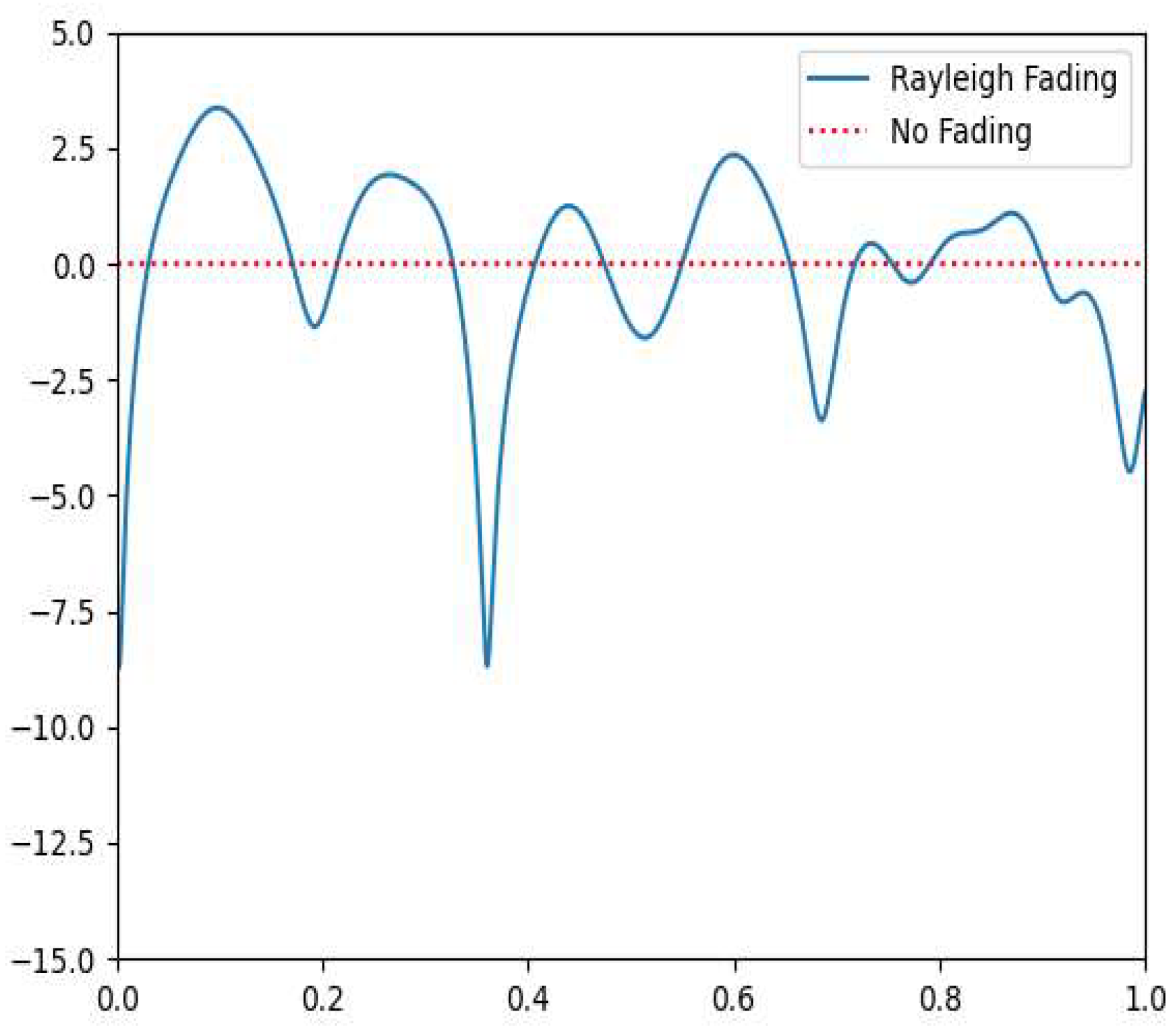

Figure 2. The channel model has no state and produces an output independent of the previously received inputs. In the channel, the signal is multiplied by a complex number representing the amplitude and phase changes of a signal. The amplitude and phase of this number can be time-dependent to represent time-varying, multipath fading channels. We limit time dependence only to the linear function because we assume that the duration of the message is short compared with characteristic times of change. The time-dependent phase also considers the mismatch between transmitter and receiver frequencies. In addition, the phase includes a fixed random part that represents propagation-related phase rotations. The time dependence of the amplitude models the fading effects, such as Rayleigh fading, as shown in

Figure 3.

For the additive white Gaussian noise (AWGN) channel, Gaussian noise is added with the noise power determined by the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR). Thus, the signal

r(t) after the channel is given by the following equation:

where

is the complex fading coefficient, and

n(t) is the additive Gaussian noise drawn from the complex normal distribution.

The current channel model employs linear time-dependent amplitude and phase variations combined with AWGN to emulate Rayleigh fading, which simplifies analysis but does not fully capture the complexity of THz propagation. Real-world THz channels exhibit multipath effects, phase noise, IQ imbalance, and nonlinear distortions that can significantly impact system performance. To improve generalizability, future work will incorporate standardized THz channel profiles such as IEEE 802.15.3d, along with impairments including phase noise, IQ imbalance, and hardware-induced nonlinearities. Additionally, modeling THz-specific phenomena like molecular absorption and frequency-selective fading will enable more realistic simulations. These enhancements will allow the end-to-end autoencoder to be evaluated under conditions closer to practical deployment scenarios.

3.2. Architecture and Training of Transmitter and Receiver Neural Networks

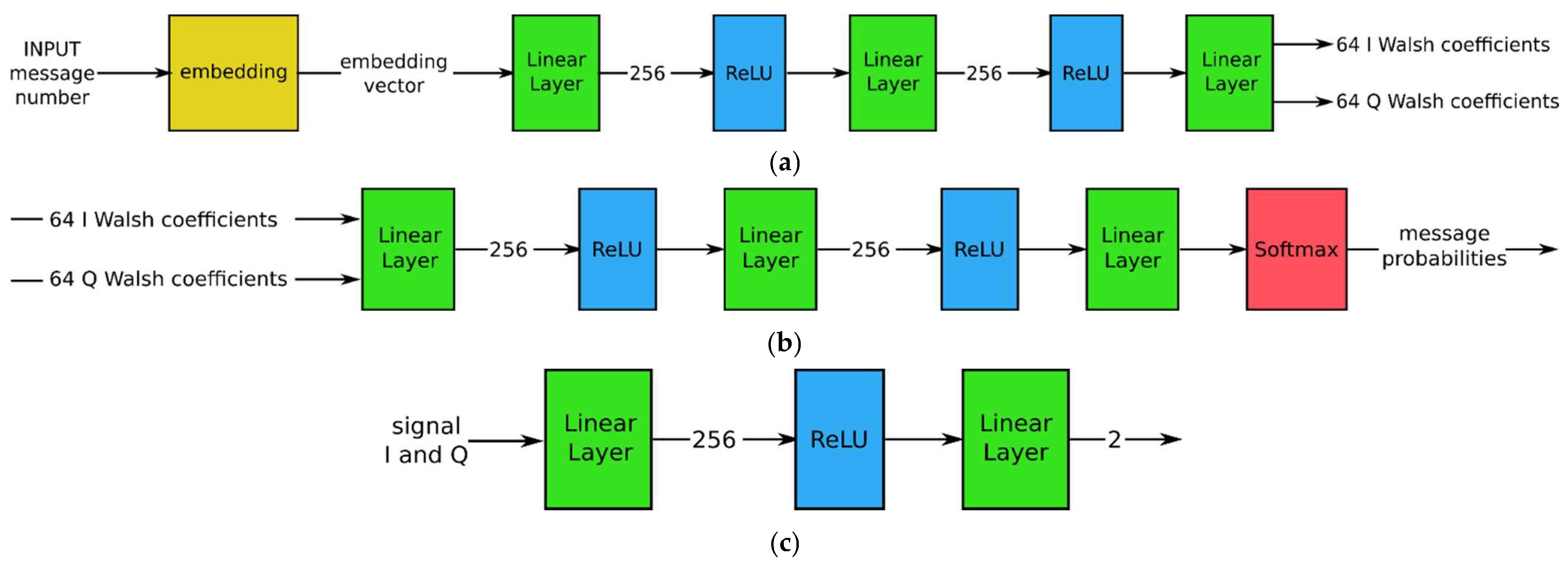

The architecture of the transmitter and receiver neural networks is shown in

Figure 4.

Following [

14], the transmitter consists of an embedding layer that converts a message number into an embedding vector and a multi-layer perceptron (MLP). The multi-layer neural network in the transmitter contains three fully connected linear layers with ReLU non-linear activation functions, except the last layer. The output of the last layer is interpreted as I and Q Walsh coefficients. Furthermore, in the transmitter, the Walsh coefficients are multiplied by the Walsh functions to form real-time I and Q signals.

In the receiver, the real-time I and Q signals are converted into Walsh coefficients using the inverse Walsh transform. Then, the Walsh coefficients are concatenated into one vector and supplied to the feedforward neural network consisting of three linear layers. The last layer of the receiver is SoftMax activation, which assigns a probability to each of the possible messages. In both the transmitter and the receiver, we used 256 as a hidden dimension. To allow an effective learning of features, the hidden dimension size was selected to be larger than the number of Walsh coefficients (64 complex numbers resulting in 128 real numbers). To limit the complexity of neural networks and the number of required operations, the hidden dimension size should be kept small, while still allowing sufficient performance. The specific hidden dimension size was chosen based on the performance on the validation data. The size of the embedding vector in the transmitter was also 256; the number of embeddings was determined by the number of messages, 2k. Similarly, the size of the last linear layer in the receiver was equal to the number of messages.

The phase estimation network in the receiver consists of two linear layers. The input to the phase estimation network is the I and Q components of the discretized time-domain signal; the output has two elements interpreted as the real and imaginary parts of a complex number.

For 8 bits per message, the transmitter neural network has 230,016 parameters; the receiver neural network has 198,146 parameters. After the transmitter neural network, the amplitude of the signal resulting from converting Walsh coefficients into the time domain is normalized. Similarly, the Walsh coefficients are normalized before the input to the receiver neural network. The computational complexity of the transmitter is 163,840 multiply–accumulate (MAC) operations; the computational complexity of the receiver is 197,120 MAC operations. For header detection, discussed in

Section 4.3, the required number of floating-point operations is around 8000. To transmit one message, one needs to perform 327,680 floating-point operations in the transmitter and 394,240 in the receiver. A sequence of headers and 16 messages, thus, requires 11,558,720 operations and transmits 16 × 8 = 128 bits. Thus, we have 90,303 floating-point operations per bit sent.

The process of training the end-to-end system proceeds as follows. First, random binary data are generated. In addition, for each message (or message group for the training with preamble headers), we randomly select from the predetermined range the parameters of the channel model: the linear slope

s, initial phase φ, and inter-sample phase offset Δ

φ of the multiplier and SNR of the AWGN. Random channel parameters during training allow for the resulting neural networks to be insensitive to the actual channel parameters. The autoencoder is trained using a cross-entropy loss function, using the message number as a label:

where

pn is the

n-th element of the output probabilities, with

n being the message number.

For training, we utilized a computer having a graphics processing unit (GPU) with a compute unified device architecture (CUDA). We used the AdamW optimizer with one cycle learning rate schedule [

21] and a batch size of 128 messages. The learning rate scheduling increased the learning rate according to a cosine law for 30% of the whole duration up to the maximum learning rate of 10

−3, with a starting learning rate of 4 × 10

−5. Training data for each epoch were randomly generated, each epoch containing 2

17 random combinations of channel parameters and message numbers. Channel parameters consisting of the initial phase φ, the inter-sample phase offset Δφ, the inter-sample amplitude slope s, and the SNR of the Gaussian noise were sampled from uniform distributions within the allowed parameter ranges. The hyperparameters were optimized on validation data containing 7560 items, which were generated ahead of time. To generate the validation data, combinations of channel parameters were uniformly sampled from allowed parameter ranges, and for each combination of channel parameters, all message numbers were included. For the remaining 70% of the learning duration, the learning rate decreased to zero according to a cosine law. Similarly, the exponential decay rate for the first moment estimates of the Adam optimizer (β1) was decreased to 0.85 and then increased again. The weights of the neural networks were subjected to regularization, and the weight decay parameter in the AdamW optimizer was 10

−2. The duration of the training was 60 epochs. The typical loss dependence on the training epoch during training is shown in

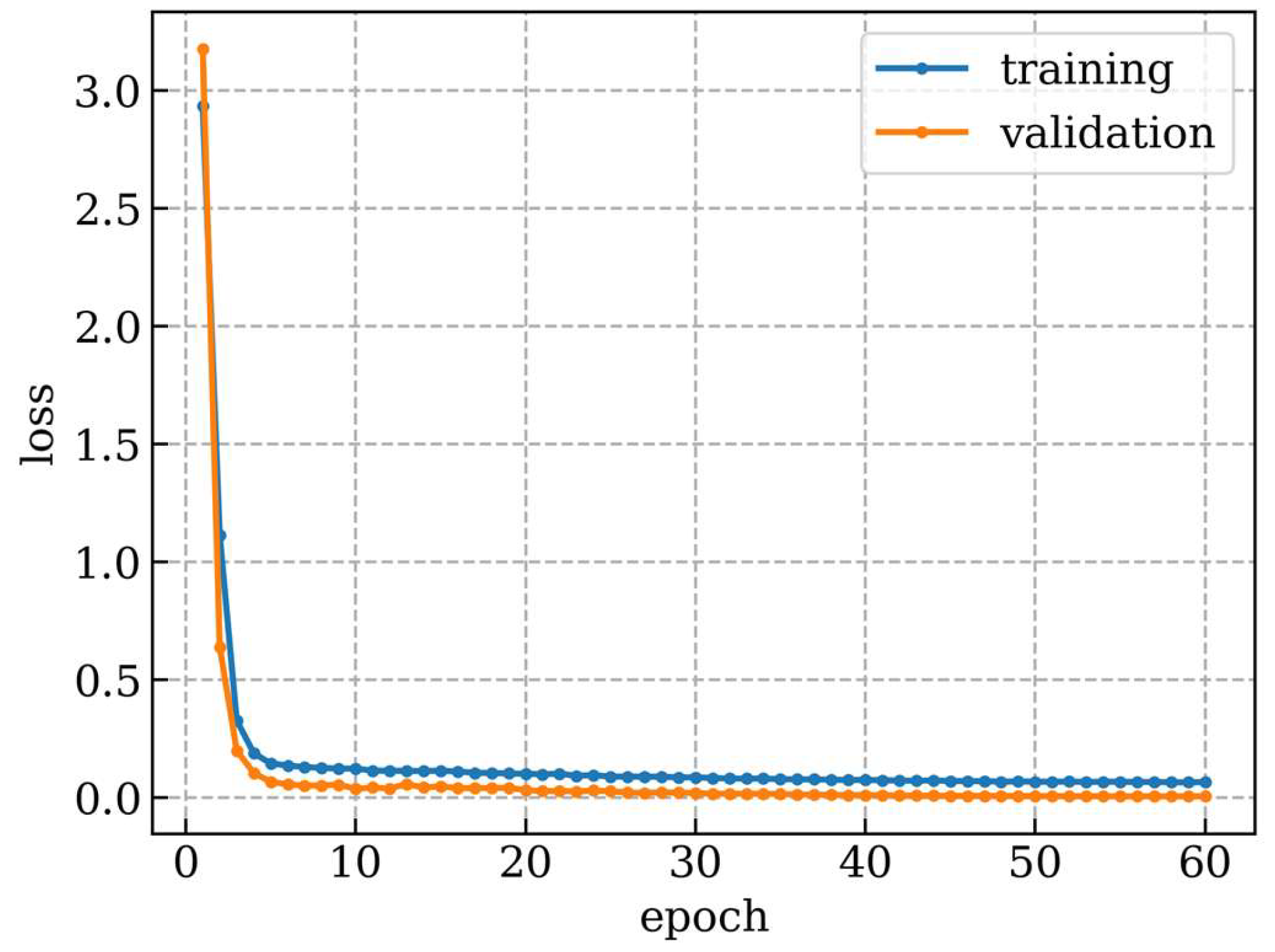

Figure 5. We see that the loss rapidly decreased for the first several epochs, after which the decrease became much more gradual. At first, we assumed an idealized communication system with perfect timing and frequency synchronization. For more realistic modeling, we prepended a header for synchronization.

3.3. Models for Larger Number of Bits per Message

When the number of bits per message is larger than eight, the neural network architectures, similar to that proposed in [

14], are not optimal due to the large number of parameters in the embedding layer. To reduce the number of parameters, in the case of a large number of bits, we employed parallel processing and transmission of groups of bits, similar to OFDM. The scheme of such a communication system is shown in

Figure 6.

The bits in the message are divided into groups of 8 bits, the number of groups ngroup being equal to the number of bytes in the message data. The 64 Walsh coefficients are divided into the same number of groups, and for each group of bits, a set of Walsh coefficient indexes is assigned.

The input to the transmitter neural network is a list of indexes of the length n

group instead of a single message index. All groups in the transmitter neural network are processed in parallel, and the output Walsh coefficients are reshaped to a sequence of 64 coefficients, which are then used to form a real-time transmitted signal. Similarly, in the receiver, the Walsh coefficients are divided into groups before being input to the receiver neural network, and the resulting groups are decoded in parallel, giving the prediction for each group. Such a method limits the number of messages relevant for the transmitter and receiver neural networks to 2

8 = 256. The neural networks can have the same architecture shown in

Figure 4, only the number of Walsh coefficients is smaller. Such an approach allows us to keep the number of parameters in neural networks small at the cost of an increased number of computational operations.

3.4. Model Adaptation for Different Values of SNR

Adaptive modulation and coding (AMC) methods allow for communication systems to adapt the transmission of data over a channel with varying operating conditions. The channel conditions are mapped to a particular modulation and coding scheme by considering the transmit power, expected channel use, and error rate [

22].

In this paper, we propose to use the same model architecture for multiple coded modulation schemes adapted to different SNR values in the channel. This method corresponds to multi-task learning (MTL) in deep learning research. MTL is concerned with the training of a single neural network to concurrently perform different but related tasks. This can be achieved by the network architecture design, model regularization, and training methods [

23].

To adapt to the different SNR values, we propose to use the same neural networks in the transmitter and the receiver for a different number of bits (1–8). In the transmitter, the number of embedding vectors is truncated depending on the number of bits, and in the receiver, the length of the output vector is truncated accordingly. That is, for the k bits, only the first 2k embedding vectors in the transmitter are used, whereas in the receiver, only the first 2k elements of the output of the last linear layer are supplied as an input to the SoftMax layer. In this approach, the size of the embedding layer in the transmitter and the size of the last layer of the receiver neural network are determined by the maximum allowed number of bits.

The optimal number of bits for a given SNR can be determined by training the end-to-end system and selecting a different number of bits per message so that the resulting error rate is minimized. For each SNR value, we select the maximal number of bits for which the SER value is larger than a threshold. We select the threshold of SER value equal to 0.01 or 1%.

After the dependence of the number of bits on the SNR is determined, the end-to-end system is trained by randomly selecting an SNR from the predetermined range and dynamically changing the number of bits per message. Dynamic changing during training is demonstrated to reduce the negative transfer between different tasks [

24]. Encountering different SNR values during the same training run forces the neural networks to adapt to different SNR values and not to specialize in a selected single SNR. Such training allows us to minimize catastrophic forgetting in multi-task learning. The proposed model architecture, where adaptation to different SNRs is achieved by a simple truncation, makes such a training procedure easy to implement.

Our proposed method is different from that of C.P. Davey et al. [

25]. We use the same neural networks for different code rates, whereas in [

25], neural networks have a common path, followed by a set of branches for different code rates. The encoder and decoder were also parameterized by the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) in [

26], where it was shown that learnt constellations are correlated with the given SNR.

4. Results

4.1. Modeling of E2E Learning in Walsh Domain

For training, we selected the parameters of the channel model as follows: the initial phase φ from the interval [0, 360], the inter-sample phase offset Δφ from the interval [−2, 2], and the inter-sample amplitude slope s from the interval [−0.005, +0.005].

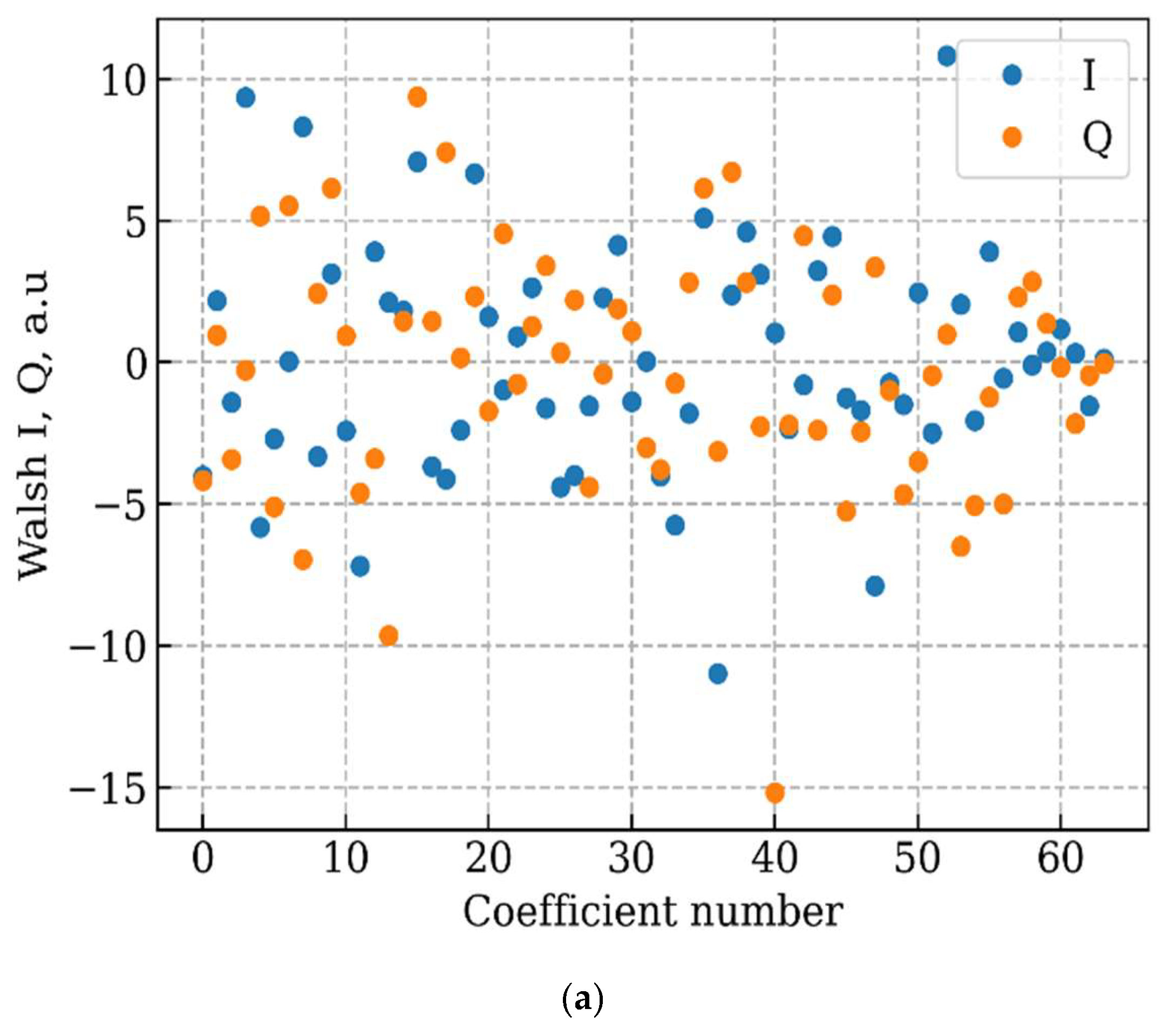

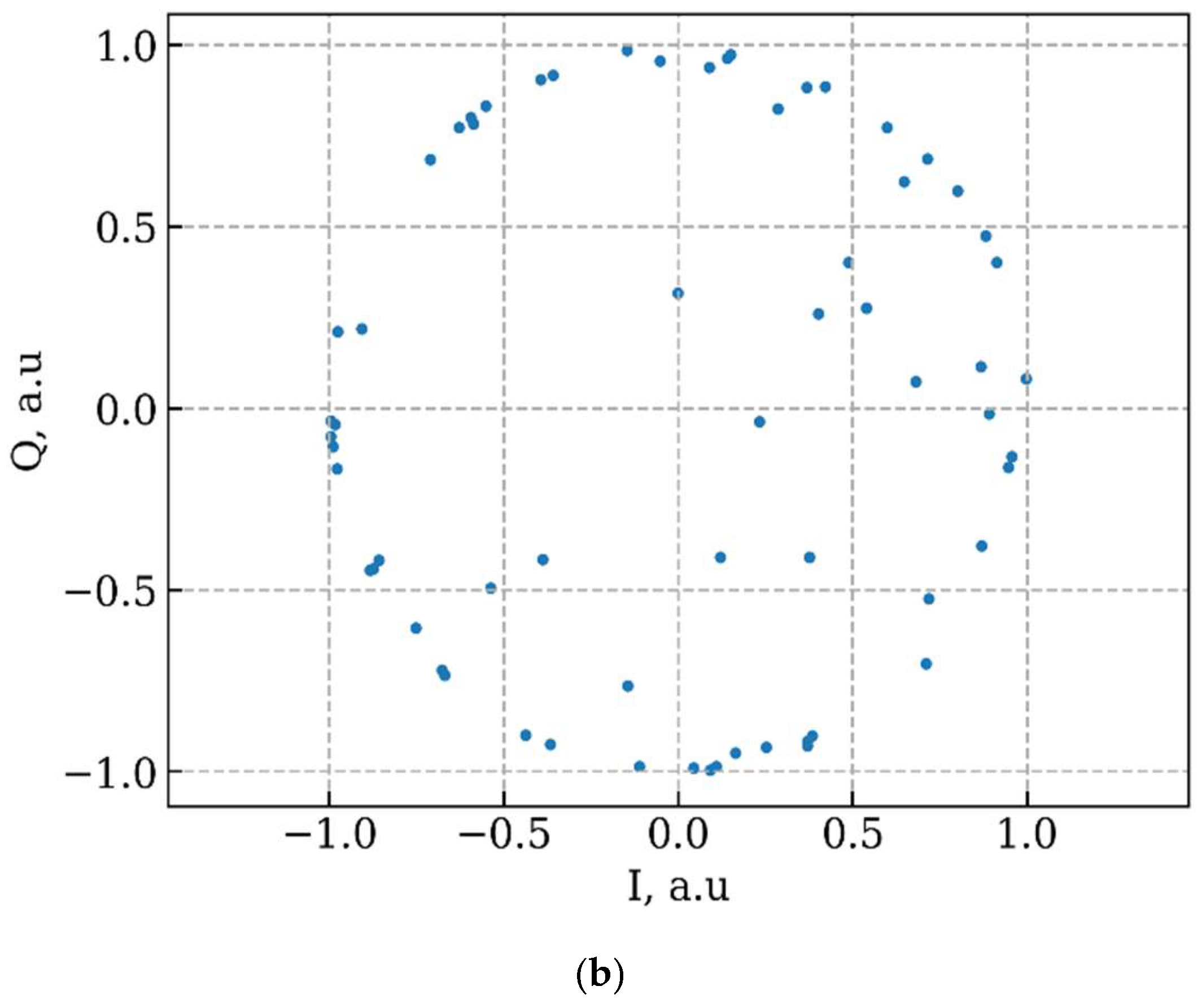

The Walsh coefficients of a message generated by a transmitter neural network and the corresponding IQ (signal in the time domain) constellation are shown in

Figure 7. As we can see, most points in the scatter plot fall on the unit circle. This way, the robustness of detection in the presence of noise is maximized. The learned constellation points at the output of the transmitter are not structured as in regular QAM. The transmitted samples are correlated over time, applying a form of optimized channel coding.

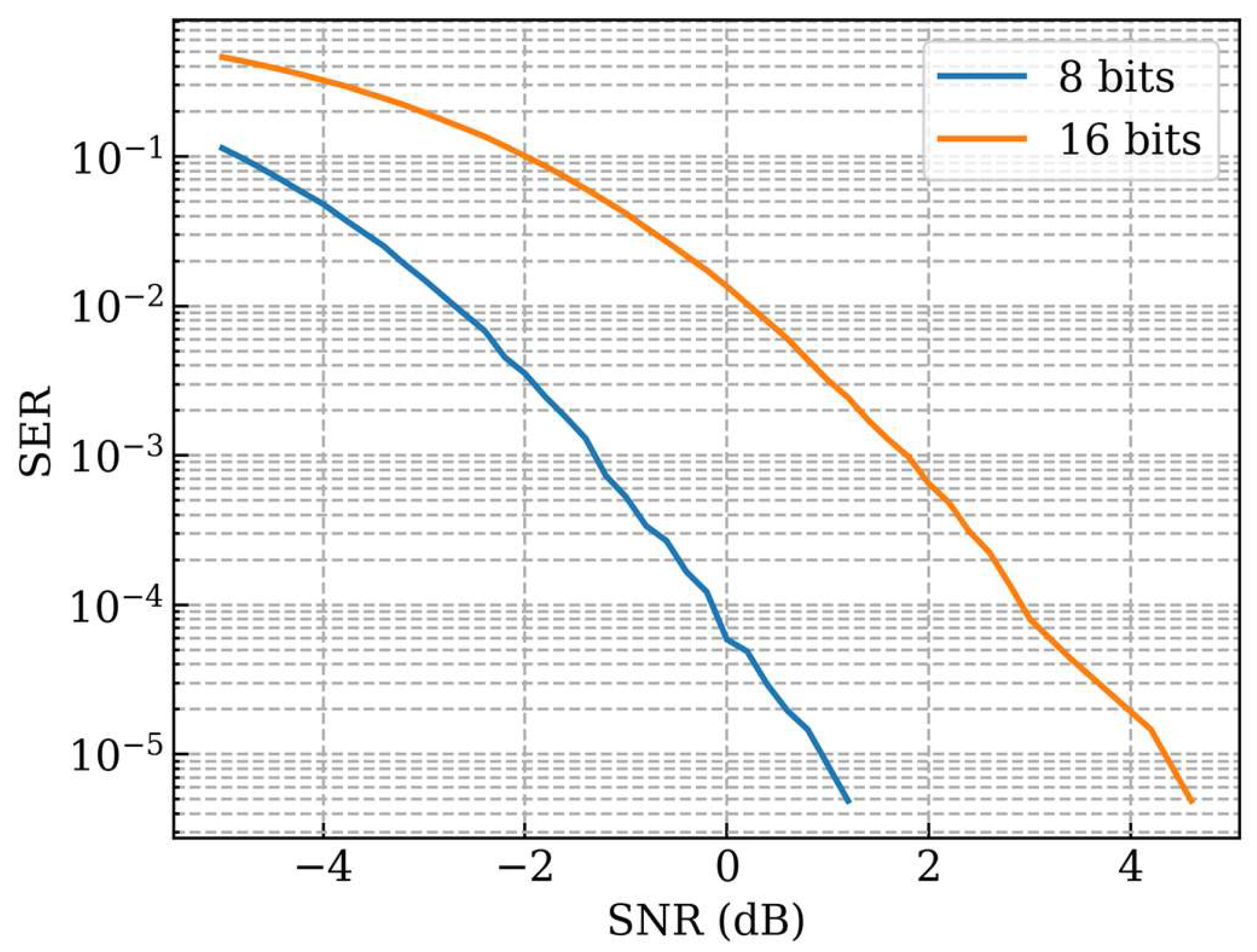

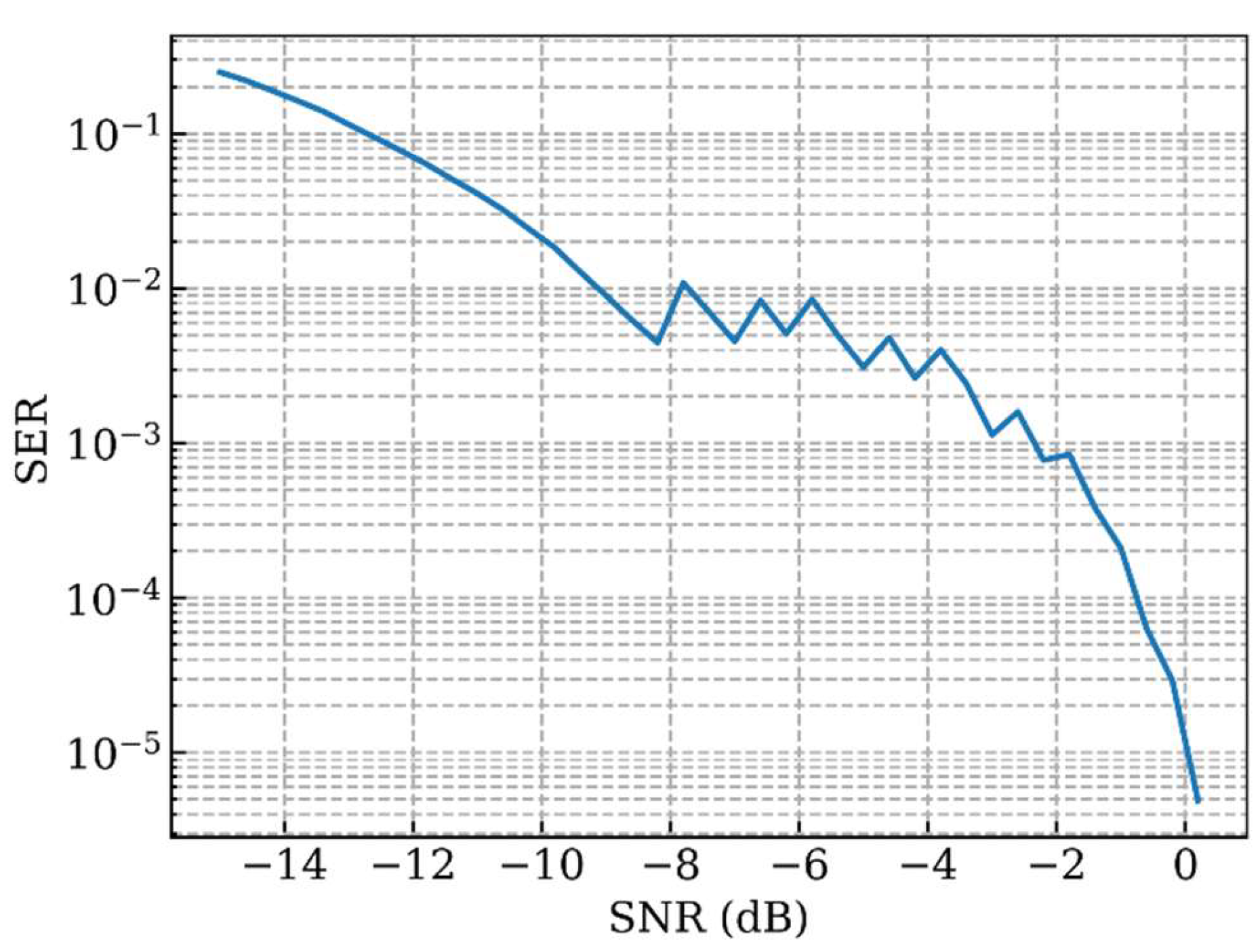

The dependence of the symbol error rate on the SNR when the message has 8 bits is shown in

Figure 8. When the message consists of 16 bits, the Walsh coefficients are divided into two groups processed in parallel. In this case, the dependence of the symbol error rate on the SNR is shown in

Figure 8. As we can see, when the number of bits per message increases, the symbol error rate increases.

4.2. Adaptation to Different SNR Values

The optimal number of bits for a given SNR can be determined by training the end-to-end system, as previously described, and selecting a different number of bits per message so that the resulting error rate is reduced. The results of the model adaptation for different SNRs are shown in

Figure 9.

We found that 8 bits per message yields an acceptable SER for a range of SNR values larger than a certain critical value. When the SNR becomes smaller than this value, the optimal number of bits almost linearly decreases with the SNR. For each SNR value, we select the maximal number of bits for which the SER value is larger than the threshold SER equal to 0.01 or 1%. To adapt to the different SNR values, we use the same neural networks in the transmitter and the receiver for a different number of bits (1–8). In the transmitter, the number of embedding vectors is truncated depending on the number of bits, and in the receiver, the length of the output vector is truncated accordingly. The constellations learned by the end-to-end system in the evaluation channel are shown in

Figure 10. Messages with low indices participate in transmissions with small as well as larger numbers of bits and, thus, are used in both large and small SNR situations. Thus, such messages are adapted to small SNRs, and to minimize the errors, they have points lying on the unit circle. In contrast, messages with a large index are employed only at a large number of bits and large SNR values. Since for such messages, the errors are less relevant, they also have points scattered inside the disk.

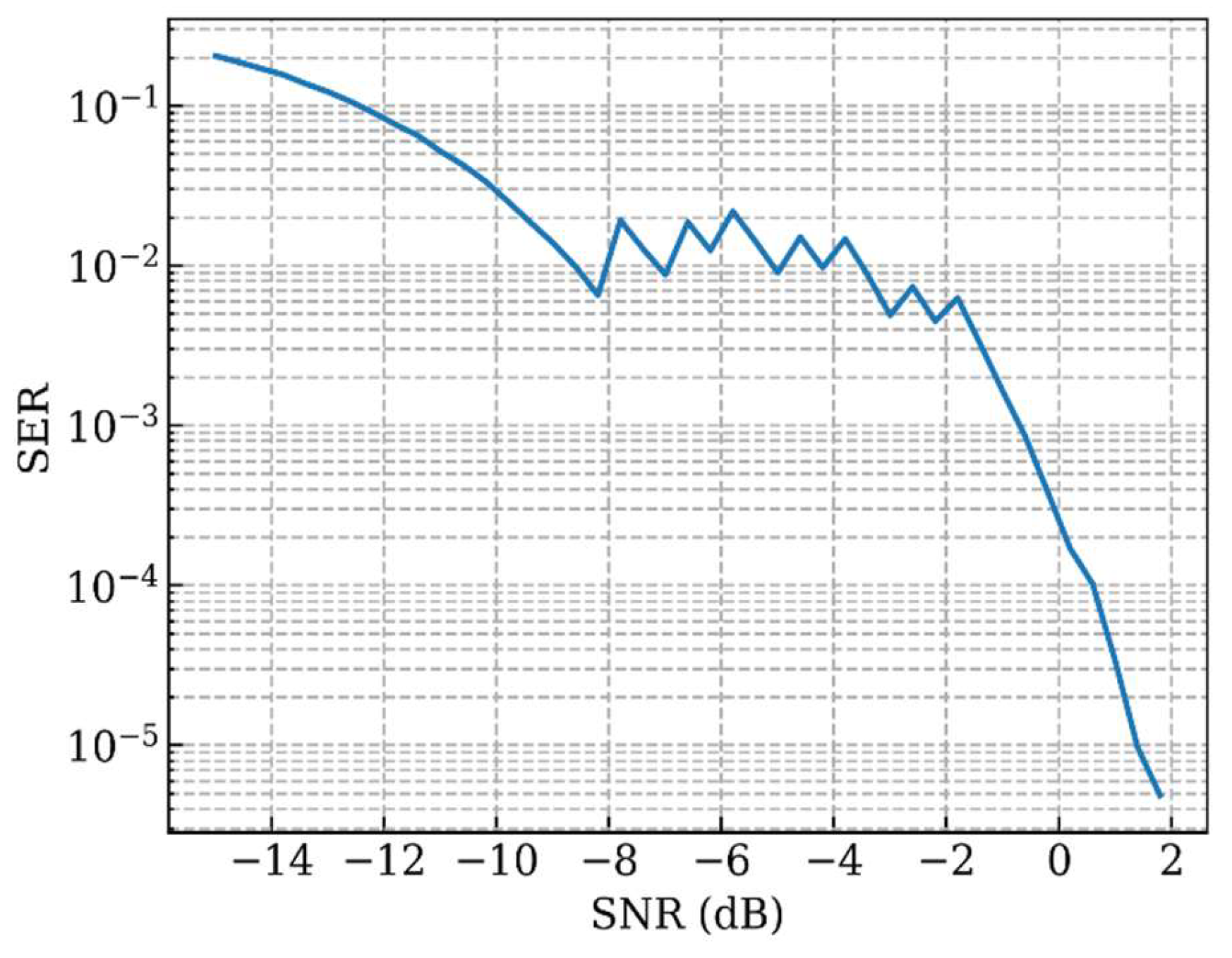

The dependence of the symbol error rate on the SNR with a varying number of bits per message is shown in

Figure 11. We can see that this method allows us to achieve low error rates for the SNR down to −10 dB. Since the number of bits per message can have only discrete values, the number of possible messages does not change smoothly. This limits the adaptation of the models and explains the jagged region in

Figure 11.

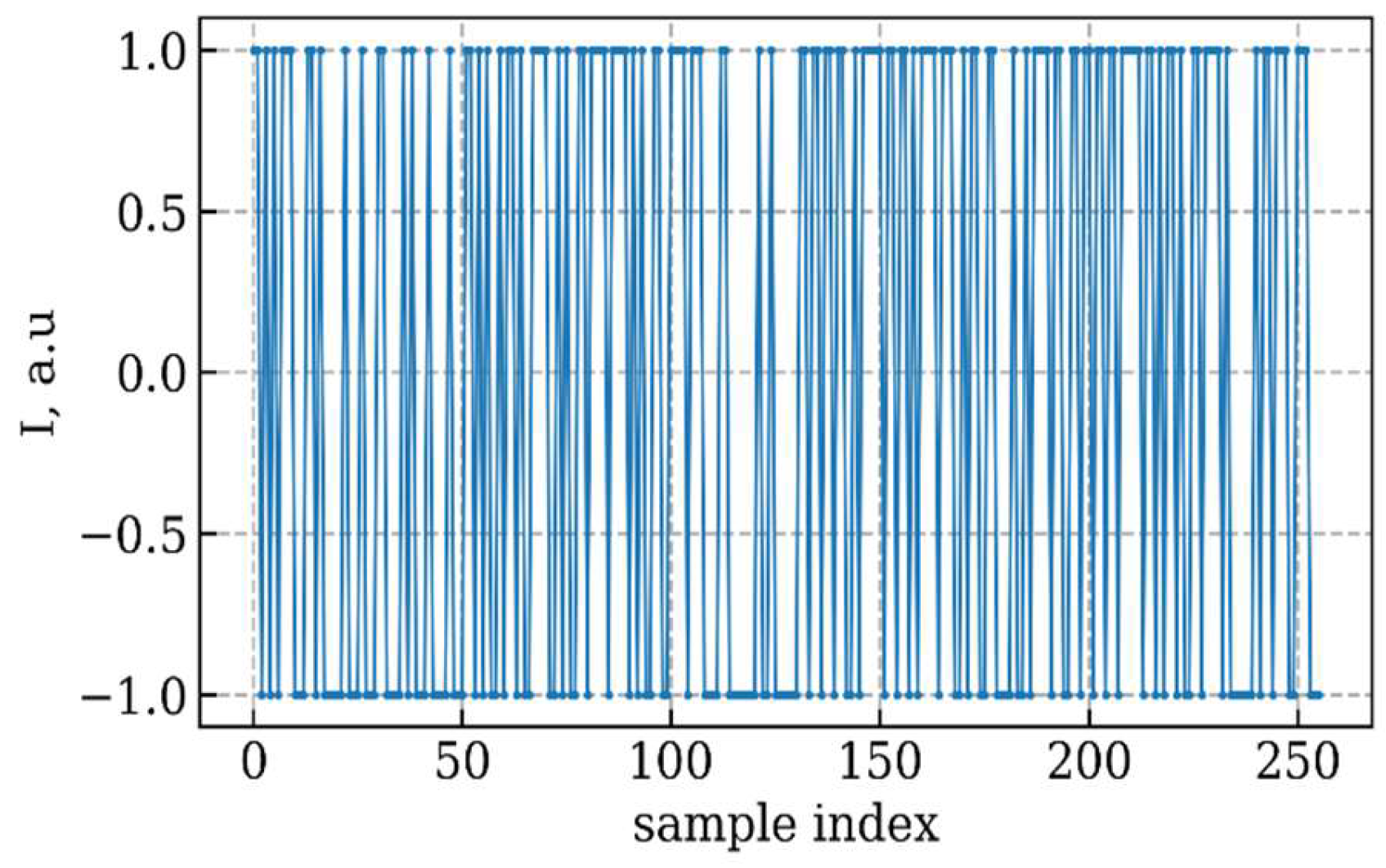

4.3. Modeling Results of Pilot-Preamble Assisted E2E Learning in Walsh Domain

In the absence of perfect timing, an efficient method to identify the start of each symbol is essential. To facilitate this, a header consisting of four messages is appended prior to the data payload. This header is generated using Binary Phase-Shift Keying (BPSK) modulation, employing a pseudo-random sequence of ±1 values. Header detection is accomplished through cross-correlation. When comparing two BPSK signals, the cross-correlation function evaluates the degree of similarity between them. If the signals are orthogonal (i.e., representing distinct data), the cross-correlation will ideally yield a value of zero, indicating no similarity. Upon detecting the header, a correlation peak will be observed. The form of the header is shown in

Figure 12.

The procedure for sending a message is modified as follows: after encoding the messages in the transmitter, a selected number of messages (i.e., 16) is concatenated into a message group, and the header is prepended to the message group. After the channel, the position of the header is detected by convolving the signal with the header, and the position of the message data is obtained. In the end-to-end system, we include the header addition and detection into the channel model, as shown in

Figure 13.

During the training phase of the end-to-end system, in order to learn to encode and decode the messages, the header detection is assumed to be perfect. Actual detection of the header is performed during the testing/evaluation phase. The header, as well as the contents of the messages, are passed from the transmitter to the receiver using the same channel. However, the parameters of the channel model describing the variation in the signal in time are reduced: the inter-sample phase offset Δ

φ is selected from the interval [−0.1, 0.1], and the inter-sample amplitude slope s from the interval [−0.0001, +0.0001]. Larger values of those channel parameters result in large errors in header detection. Scatter plots using all messages for a given SNR are shown in

Figure 14.

The number of bits per message is changed according to the value of the SNR. For a small SNR, the points are lying on the unit circle; for large SNR values, the points are also scattered inside the disk. The dependence of the symbol error rate on the SNR with varying numbers of bits per message and synchronization headers in the channel learned by the neural networks is shown in

Figure 15.

The results of the experiments show that imperfect detection of the header reduces accuracy for low SNR values and does not allow the receiver to decode the signals when the phase changes in the channel are too large.

4.4. Quantization of Proposed E2E Autoencoder Model

To prepare the transmitter and receiver neural networks for edge devices, the models were quantized using the tools provided by the PyTorch version 2.2 library. The weights and activations of the models were converted from 32-bit floats to 8-bit integers. We employed quantization-aware training (QAT), which typically results in the highest accuracy of quantized models. Employing quantization-aware training, all float values are rounded to mimic integer values, but all computations are still carried out with floating-point numbers. Before the quantization-aware training, the weights of the already trained float-based models were loaded. The same training dataset, described in

Section 3.2, was used for quantization-aware training. The AdamW optimizer and one cycle learning rate schedule were used, with a batch size of 128 messages, a maximum learning rate of 10

−5, and a weight decay parameter in the AdamW optimizer of 10

−2. The duration of the training was 40 epochs.

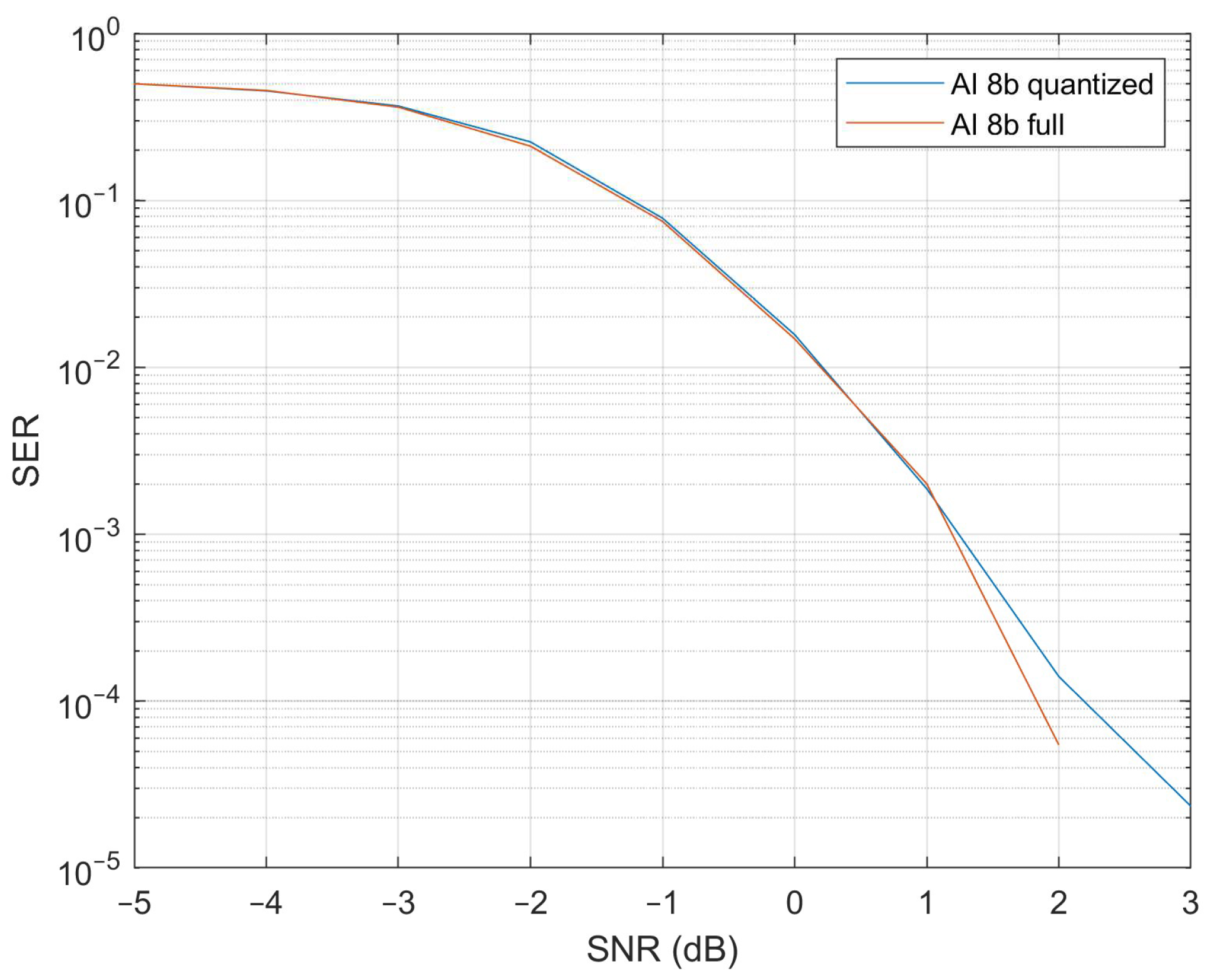

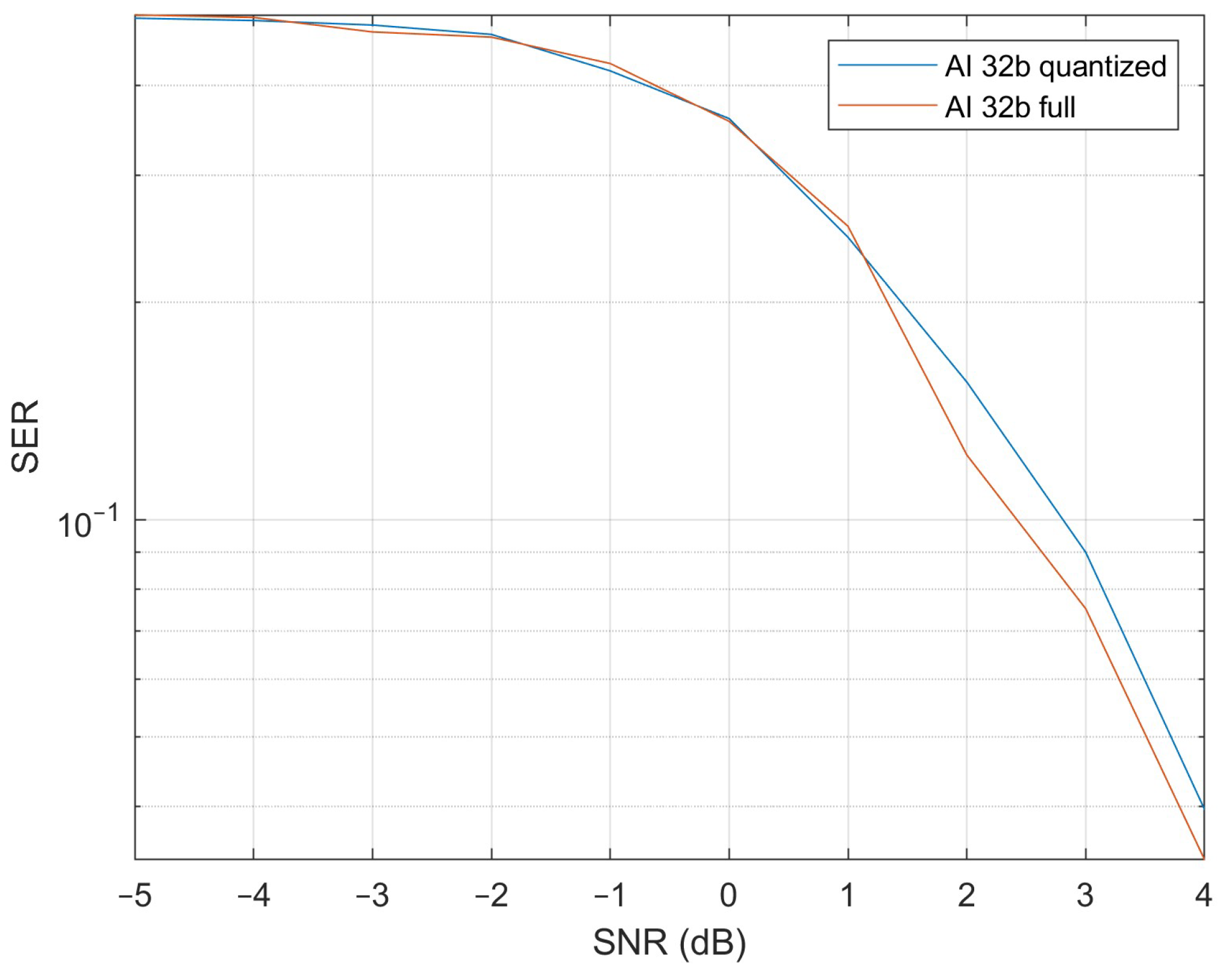

We estimated the data processing durations of the quantized and non-quantized models (8-bit and 32-bit versions) by passing 1000 messages to both quantized and non-quantized E2E autoencoder models. A previously described modeling structure using a header for synchronization purposes was used. Time measurements were made by starting the clock before providing binary data to the model and stopping the clock after receiving results. The results indicate that the data processing time can be reduced by a factor of two using the quantized versions with the same hardware equipment. In

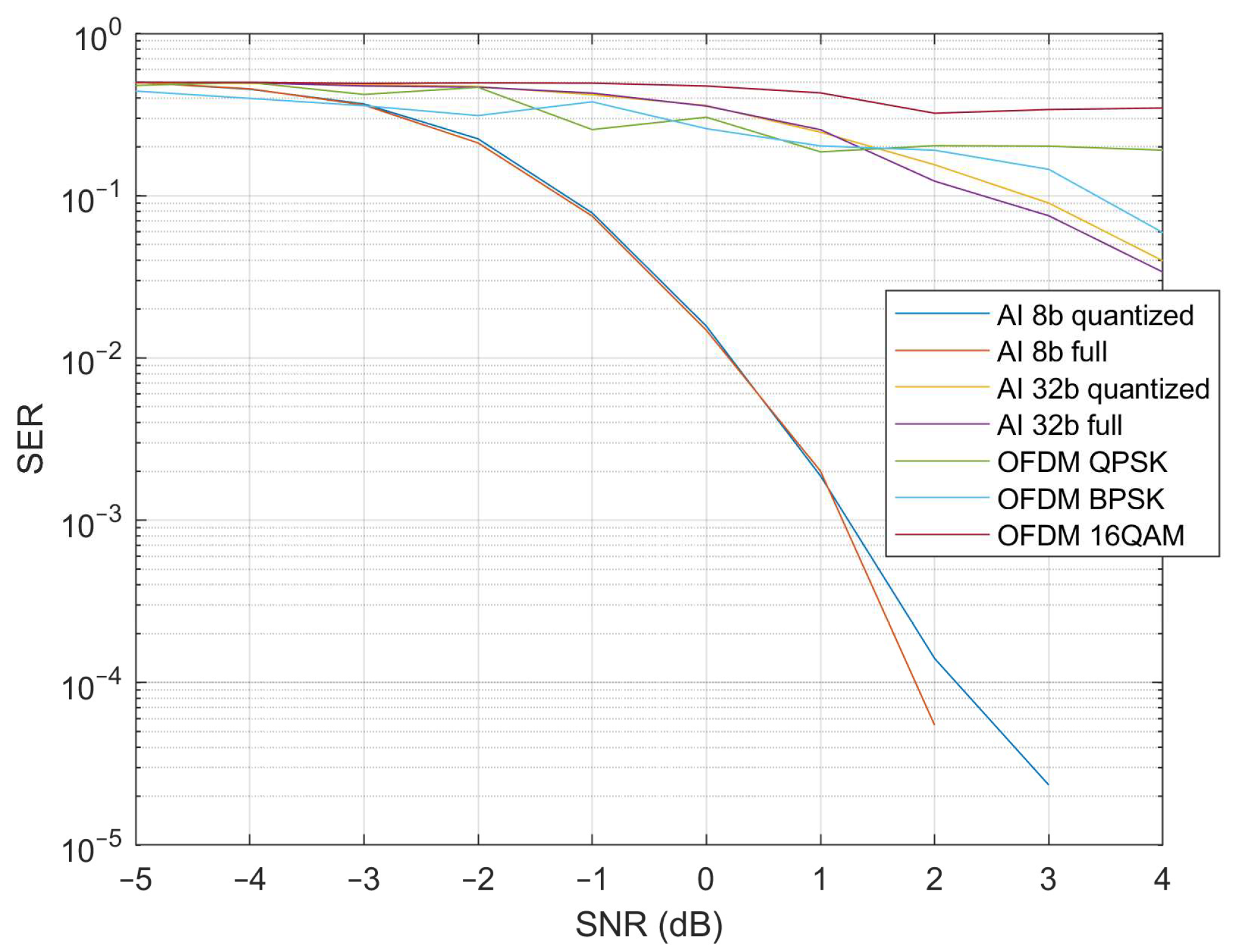

Figure 16 and

Figure 17, the SER performances of quantized and non-quantized (8-bit and 32-bit) E2E models are presented. As can be seen in

Figure 17, the SER of both models remains almost the same in the SNR range from −5 to 1 dB (staying in the range of −0.0026–0.0128). Small differences in the SER are visible starting from 1 dB. And the SER of the quantized 8-bit model approaches 0 when the SNR is 3 dB or higher. The non-quantized version SER reaches 0 at an SNR of 2 dB.

Figure 17 presents the SER of the 32-bit model. Here, the difference between the quantized and non-quantized models is visible over the whole SNR range, but the difference is small and stays between −0.026 and 0.0128. The SER approaches 0 when the SNR is 4 or higher.

4.5. Experimental Results and Discussion

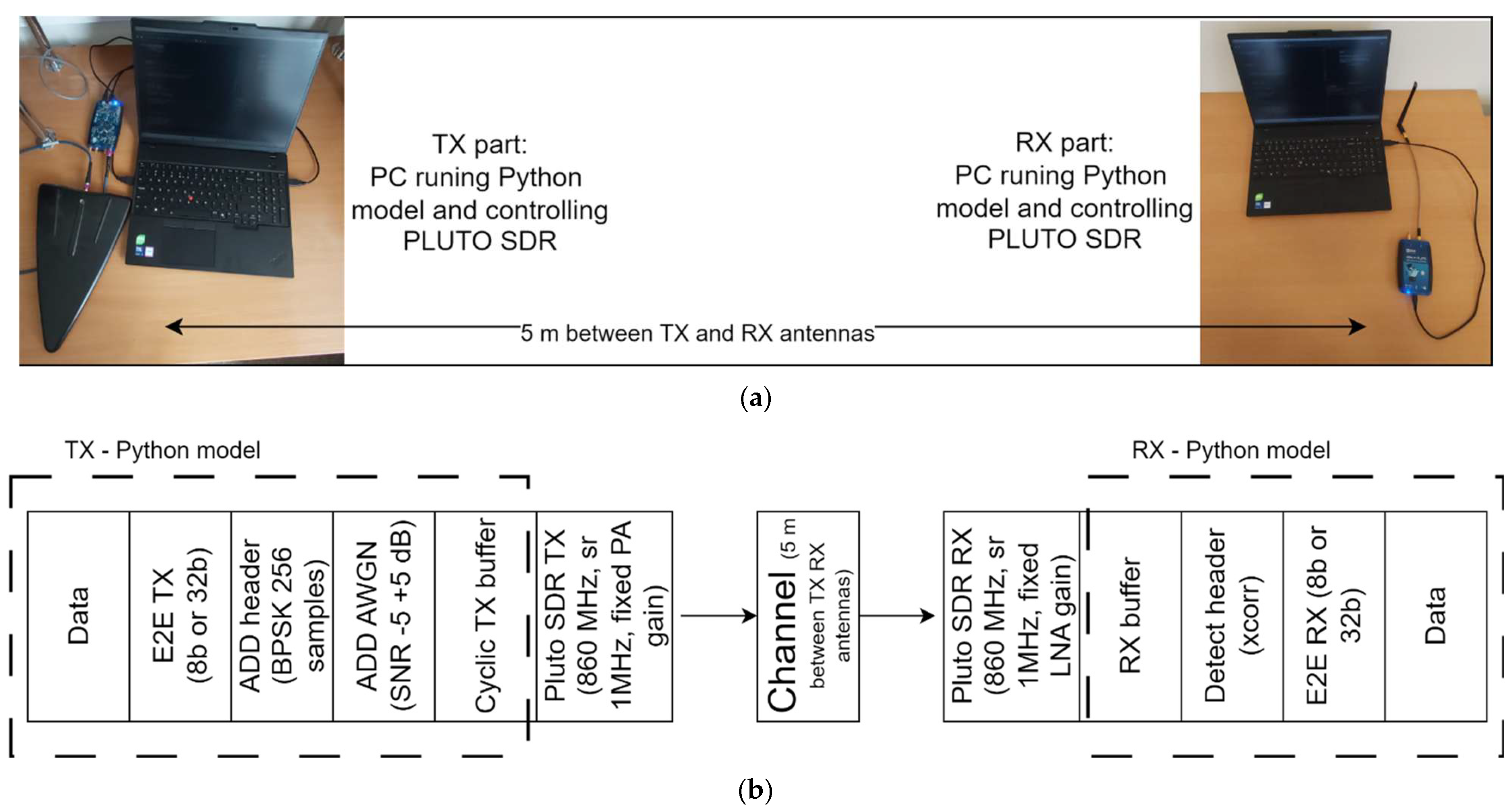

To test the proposed end-to-end scheme in real transmission, we implemented a transmission line using software-defined radio (SDR) devices. For the transmission experiment, two SDR devices were used. One Pluto SDR worked as the transmitter and another as the receiver. For the SDR device control notebooks running a Windows 11 operating system and Python 3.8 with ADI, Torch Python libraries were used. The SDR devices were placed in the laboratory with a 5 m distance between the TX and RX antennas. The whole scheme of the experiment and setup in the laboratory is shown in

Figure 18a,b. Two E2E models were tested experimentally: 8-bit and 32-bit. Random binary data were generated and grouped into messages of 8 or 32 bits. Messages were passed to the E2E TX model, and as output, 64 Walsh coefficients per message were generated. For synchronization purposes, the header of 256 BPSK samples was added before the first message. In total, per frame, 1000 messages were generated, and an IQ signal was formed (256 header samples + 1000 × 64 Walsh coefficient samples). For easier control of the channel influence on the transmitted IQ signal, the Pluto SDRs had fixed LNA (low noise amplifier) and PA (power amplifier) values. The SNR (signal-to-noise ratio) value was controlled by adding AWGN (additive white Gaussian noise) to the IQ signal. The final IQ signal was transferred to the cyclic TX buffer of Pluto SDR and transmitted repeatedly at 860 MHz using a 1 MHz sample rate. At the receiver, a three times bigger buffer was used so we could catch at least 2–3 frames from the transmitter. Firstly, using the buffered data, the header was detected with the use of the cross-correlation algorithm. Then raw IQ data were passed to the E2E RX model, and from the output, decoded messages could be received. For comparison of the AI-based Walsh E2E communication model with today’s widely used wireless communication techniques, using the same experimental setup, OFDM-modulated data were sent. It should be mentioned that no additional data recovery algorithms were used in the E2E model; therefore, no data correction algorithms were used in the OFDM model either. Three different OFDM signals were used. These OFDM parameters were used: first, - 1 signal, 64 FFT, BPSK modulation, 8 pilots, and CP 16 symbols; second, - 64 FFT, QPSK modulation, 8 pilots, and CP 16 symbols; and third, 64 FFT, 16QAM modulation, 8 pilots, and CP 16.

Figure 19 presents the experimental results, comparing the bit error rate (BER) versus the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR). The comparison includes both quantized and non-quantized versions of the end-to-end (E2E) model for 8-bit per packet signals. The results indicate that in the negative SNR range, both versions perform similarly. However, in the positive SNR range, the non-quantized version begins to operate error-free more quickly. This behavior is expected, as the non-quantized model, utilizing floating-point numbers, benefits from a larger dynamic range. A similar trend is observed with the 32-bit E2E model, where the BER remains higher across the entire SNR range. This is logical because the 32-bit model generates 64 Walsh coefficients, resulting in oversampling by a factor of two, whereas the 8-bit model achieves oversampling by a factor of eight (8 bits per message and 64 coefficients). As anticipated, the BER for Orthogonal Frequency-Division Multiplexing (OFDM) signals follows a predictable order: the lowest for Binary Phase-Shift Keying (BPSK), slightly higher for Quadrature Phase-Shift Keying (QPSK), and highest for 16-Quadrature Amplitude Modulation (16QAM). If we compare the results of OFDM vs. the E2E autoencoder, we can see that the 8-bit quantized and non-quantized versions perform better starting from −3 dB and higher values of the SNR. The 32-bit version of the E2E autoencoder starts to perform better from 1.5 dB, and for higher SNR values.

In this work, we focused on modeling an end-to-end (E2E) autoencoder-based communication system using Walsh functions for modulation and demodulation. While the symbol error rate (SER) and bit error rate (BER) were evaluated, a detailed analysis of computational complexity, energy efficiency, peak-to-average power ratio (PAPR) reduction, and latency was not performed. These metrics are highly dependent on the underlying hardware implementation, parallelization strategies, and quantization precision, which were beyond the scope of this study. Our experiments were conducted in a simulation environment without targeting a specific hardware platform; therefore, estimating FLOPs, latency, or power consumption would be speculative. Future work will include profiling the proposed architecture on representative hardware (e.g., FPGA, GPU, or ASIC) to provide a comprehensive comparison with OFDM in terms of complexity, efficiency, and real-time performance.

It must be mentioned that, in our implementation, the WHT-based autoencoder was not explicitly trained for error correction, nor was any separate coding mechanism introduced. The neural network was optimized solely for symbol mapping and reconstruction within the given channel model, without incorporating redundancy or coding layers. This design choice reflects the efficiency of end-to-end learning, where the model directly minimizes reconstruction error rather than implementing traditional coding schemes. While some studies have shown that end-to-end learning can implicitly capture coding-like structures during optimization [

13], this effect is highly dependent on architecture and training objectives. In our case, the network was trained without any additional constraints or loss components that would encourage coding behavior. Therefore, the performance gain observed is attributed to the modulation and reconstruction process rather than hidden coding mechanisms. For fairness, the OFDM baseline was evaluated under the same conditions—without additional error-correcting codes—ensuring that the comparison reflects modulation and reconstruction performance rather than coding gains. Future work may explore comparisons with OFDM-based autoencoders trained under similar end-to-end paradigms to provide a broader perspective on architecture-level differences.

Our study primarily focused on modeling an end-to-end (E2E) autoencoder-based communication system using Walsh functions for modulation and demodulation. While the SER and BER were evaluated, a detailed analysis of computational complexity, energy efficiency, PAPR reduction, and latency was not performed because these metrics are strongly hardware-dependent and require profiling on specific platforms (e.g., FPGA, GPU, or ASIC). Estimating FLOPs, latency, or power consumption in a purely simulation-based environment would be speculative. Nevertheless, the choice of the Walsh–Hadamard transform (WHT) over conventional FFT-based OFDM inherently reduces algorithmic complexity. The WHT relies only on addition and subtraction operations, avoiding complex multiplications that the FFT requires. This makes the WHT structurally simpler and theoretically faster, which suggests potential gains in inference speed and energy efficiency when implemented on hardware. However, formal complexity metrics and latency measurements are left for future work. Future research will include profiling the proposed architecture on representative hardware to quantify operation counts, parameter efficiency, and real-time performance relative to OFDM.

5. Conclusions and Future Work

The communication system implementing an E2E autoencoder using Walsh–Hadamard transform-based modulation could potentially offer reduced complexity and improved performance compared with traditional OFDM systems. This is due to the simplicity of WH basis functions, which use binary digits and avoid complex multiplications, making them more efficient and robust under specific conditions. Although the Walsh–Hadamard transform (WHT) offers computational simplicity and orthogonality, it has several limitations that must be considered. The WHT is sensitive to timing errors due to the abrupt transitions in Walsh functions, which can lead to performance degradation under jitter or synchronization issues. Additionally, scaling the WHT to very high data rates introduces hardware challenges, as generating and switching Walsh sequences at gigabit speeds requires precise timing and fast logic. These drawbacks primarily affect hardware implementation rather than algorithmic design. Mitigation strategies include using synchronization circuits, oversampling, and adaptive timing recovery to address timing sensitivity, while parallel and pipelined FPGA or ASIC architectures enable high-speed operation by exploiting WHT’s reliance on additions rather than multiplications. In our work, we focus on the software model of an end-to-end autoencoder, where these hardware constraints do not apply, but we acknowledge their relevance for practical deployment. The E2E autoencoder uses neural networks in both the transmitter and receiver to process and interpret signals, with specific design choices for embedding, layer structure, and normalization to ensure accurate message transmission and phase estimation. The proposed end-to-end system can be adapted to different SNR values using the same neural networks in the transmitter and receiver by varying the number of bits per message. We found that as the SNR decreases below a certain threshold, the number of bits per message decreases almost linearly. This method achieves low error rates down to −10 dB, though the discrete nature of bit values limits smooth adaptation, causing variability in error rates. Both quantized and non-quantized E2E models exhibit similar performance in the negative SNR range. However, in the positive SNR range, the non-quantized model demonstrates superior error-free operation due to its larger dynamic range. Experimental results indicate that the proposed E2E Walsh–Hadamard transform-based autoencoder, under identical conditions, surpasses the performance of a conventional OFDM system. Specifically, the 8-bit quantized and non-quantized versions exhibit enhanced performance from −3 dB and higher SNR values, whereas the 32-bit E2E autoencoder demonstrates superior performance starting at 1.5 dB and above.

One of our future works will be on the implementation of E2E autoencoder transmitter and receiver neural network models in FPGA. This will give more flexibility and computational power. Besides that, we plan to add various impairments to the E2E autoencoder model, such as IQ imbalance, power amplifier and mixer nonlinearities, phase noises, and synchronization-specific impairments, such as frequency and phase offsets, and train our models to deal with them. Then, it will be possible to compare our model with FFT-based OFDM under different channel conditions.