Simple Planar Microstrip Crossover Coupler with Independent Control over Bandwidth and Selectivity

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design Requirements

- Excellent Port Matching: All ports must be well-matched to 50 Ω within the operating band to minimize signal reflections and ensure maximum power transfer.

- Low Insertion Loss: The through paths must exhibit low insertion loss to ensure minimal signal attenuation as signals transit the crossover.

- High Isolation: A critical requirement is to achieve high isolation between the two independent signal paths and across all non-transmitting ports. This minimizes crosstalk and ensures signal integrity.

- Compact Physical Footprint: The crossover must be significantly smaller than conventional designs to meet the miniaturization demands of contemporary circuits and systems.

- Defined Operating Bandwidth: The component must meet the specified performance criteria (matching, insertion loss, and isolation) over a defined fractional bandwidth (8–10%) centered at 2.4 GHz.

- Enhanced Out-of-Band Rejection: The design should effectively suppress unwanted signals and harmonics outside the intended operating frequency range, contributing to overall system electromagnetic compatibility.

- Simple: The design should be realized using planar microstrip technology, leveraging its advantages in terms of ease of fabrication and integration.

2.2. Full-Wave Simulation Environment

- Frequency Range: Simulations were conducted across the range of 1.5 GHz to 3.0 GHz to capture the full passband and out-of-band rejection characteristics.

- Port Excitation: All four ports of the crossover were excited using 50 Ohm wave-ports.

- Boundary Conditions: The structure was enclosed within an air box defined by an open radiation boundary condition, placed at a minimum distance of λ/4 (one quarter wavelength at the lowest frequency) from the edges of the structure.

- Mesh Settings: An adaptive tetrahedral mesh was employed across the entire structure and substrate volume.

- Convergence Criteria: The Delta S-parameter convergence criterion was set to 0.02, with a maximum limit of 20 adaptive passes to achieve sufficient accuracy in the S-parameter results and a minimum of two successive converged passes.

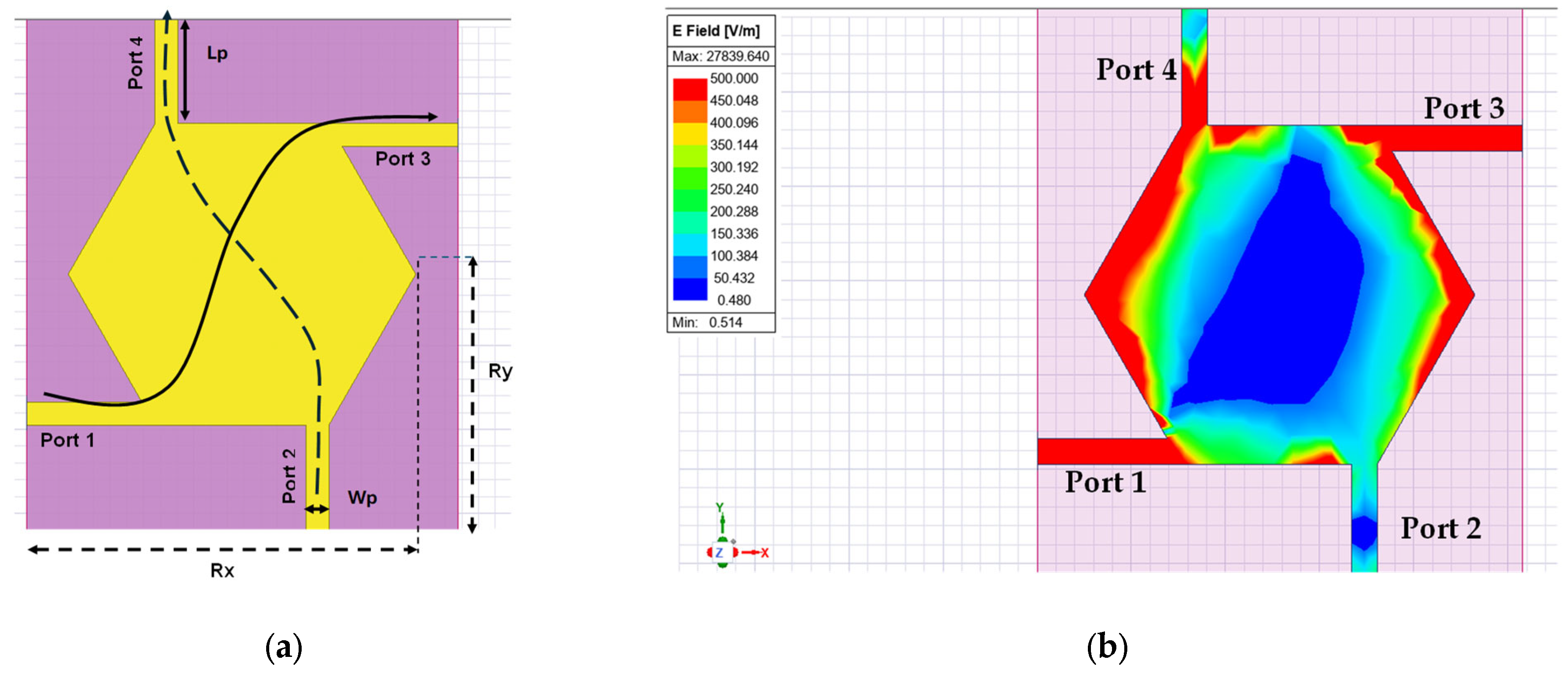

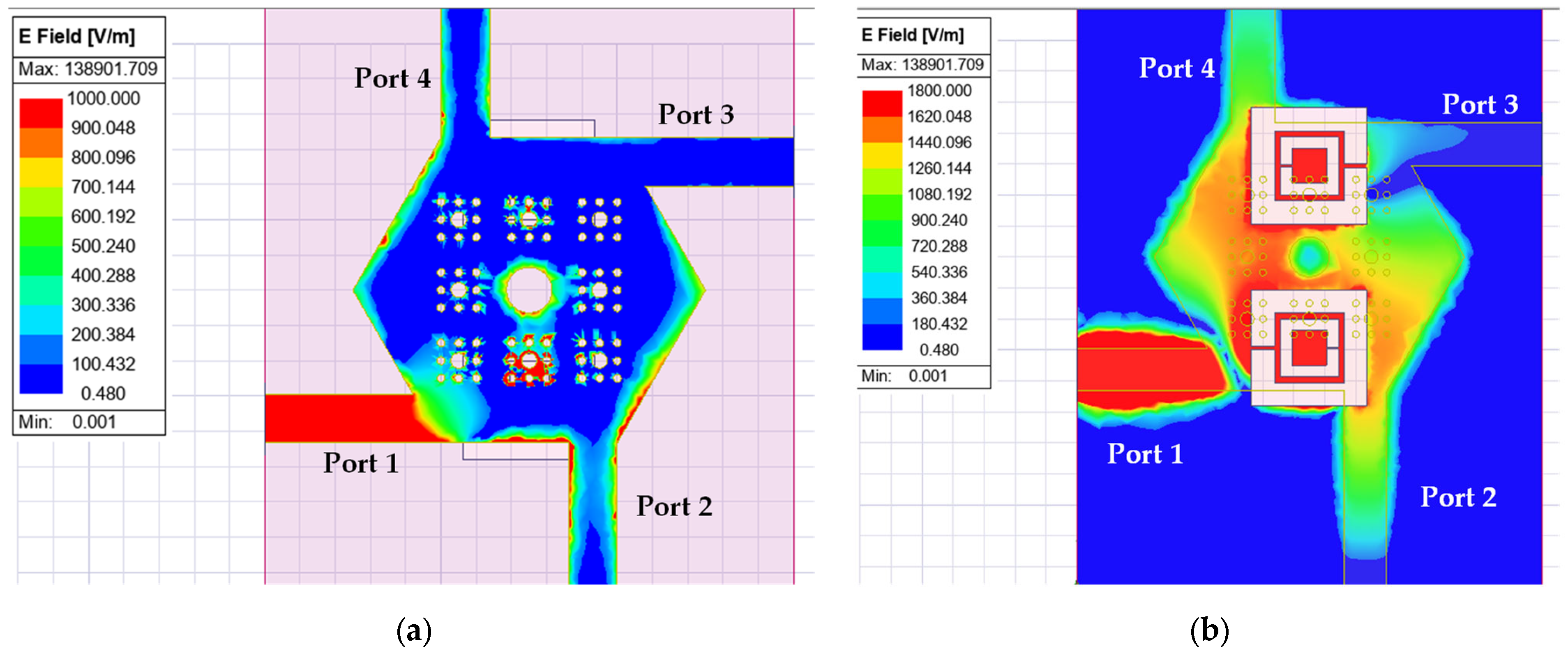

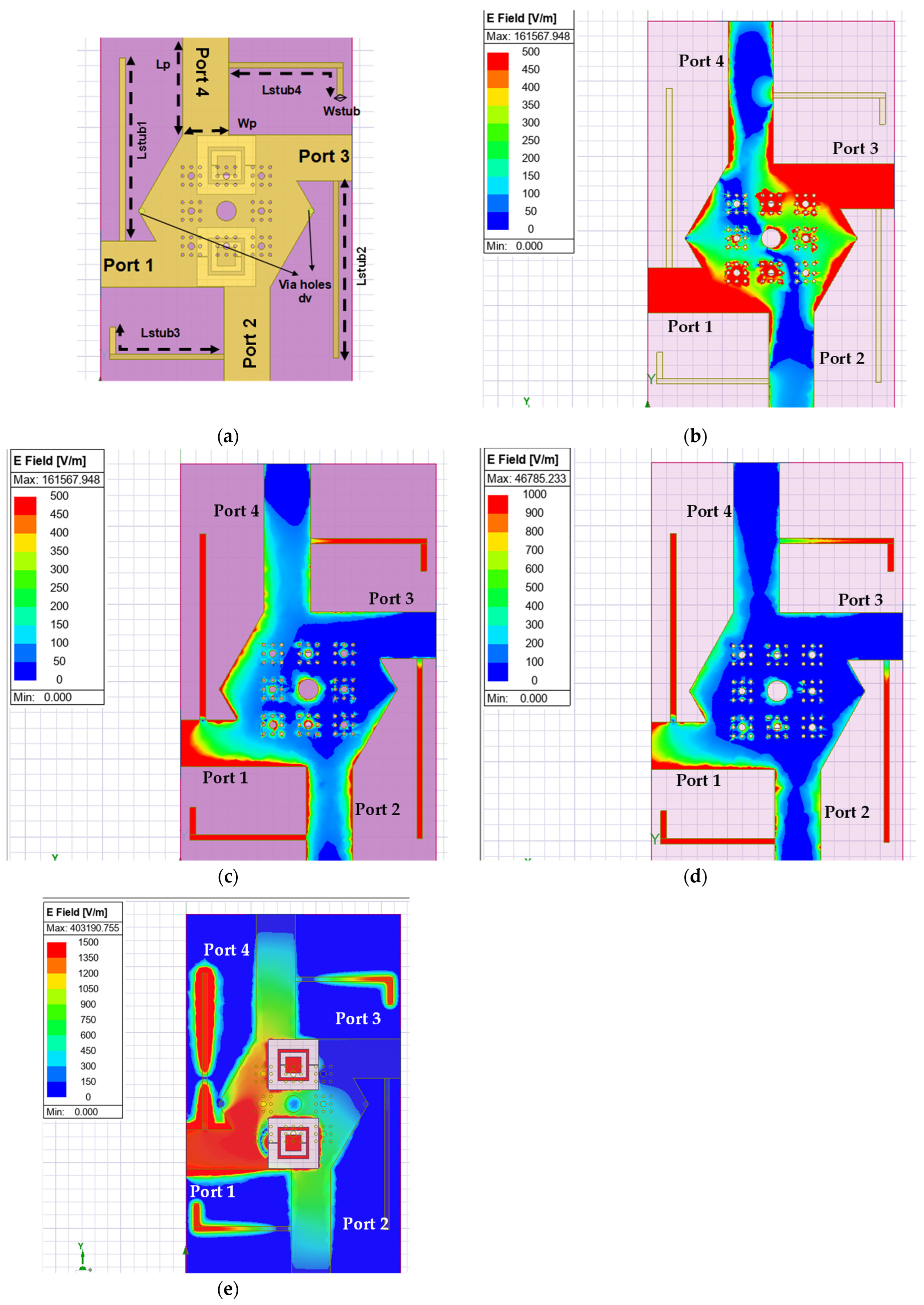

2.3. Compact Hexagonal Crossover with Serpenski and DGS

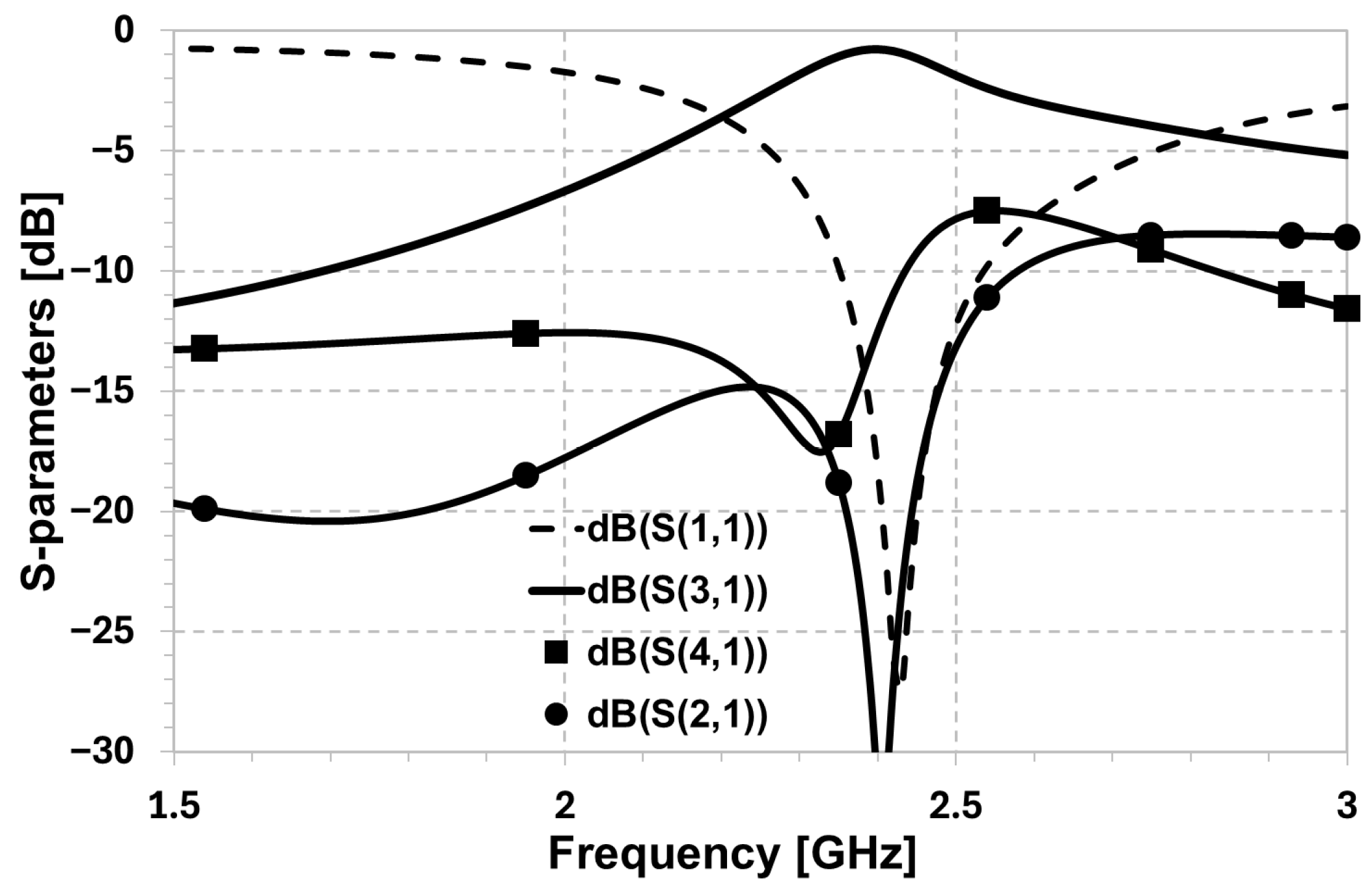

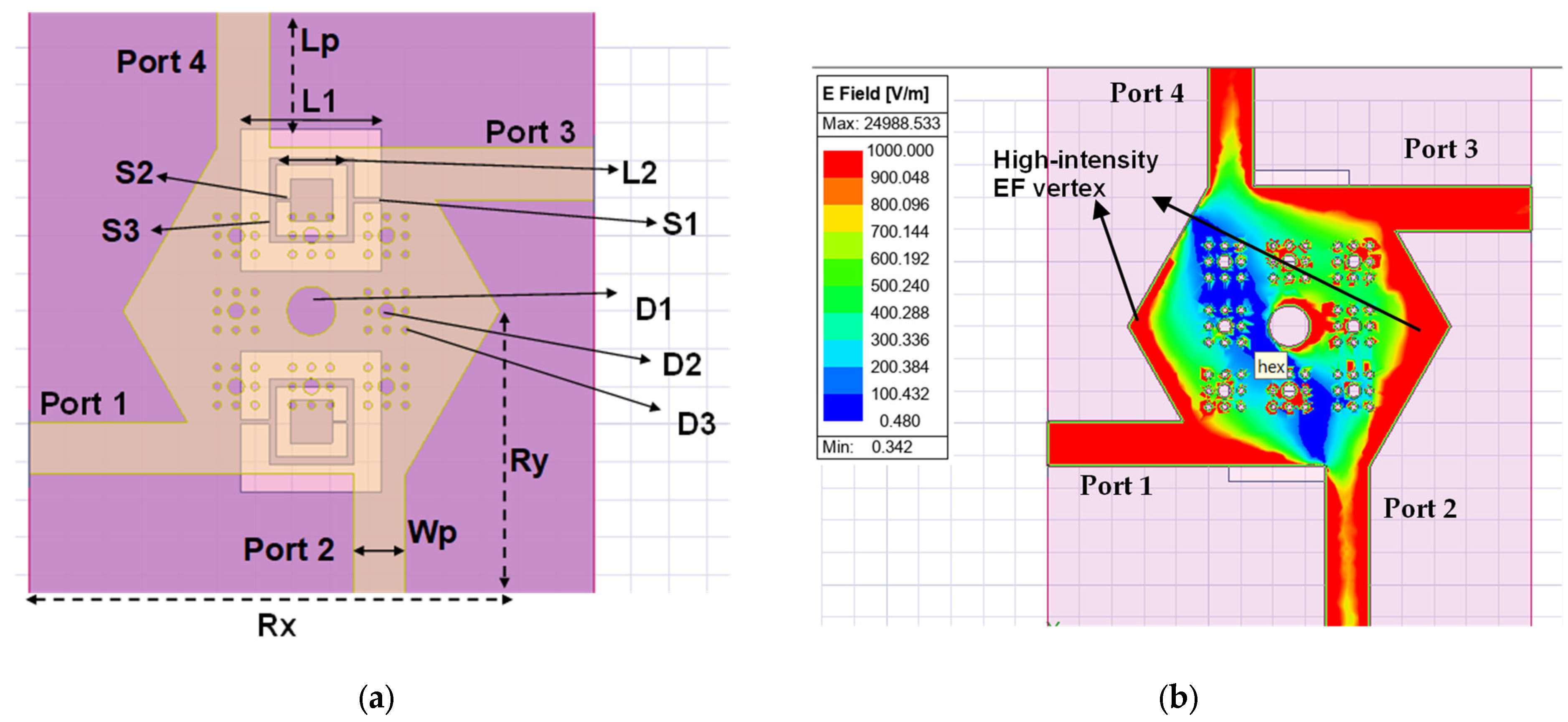

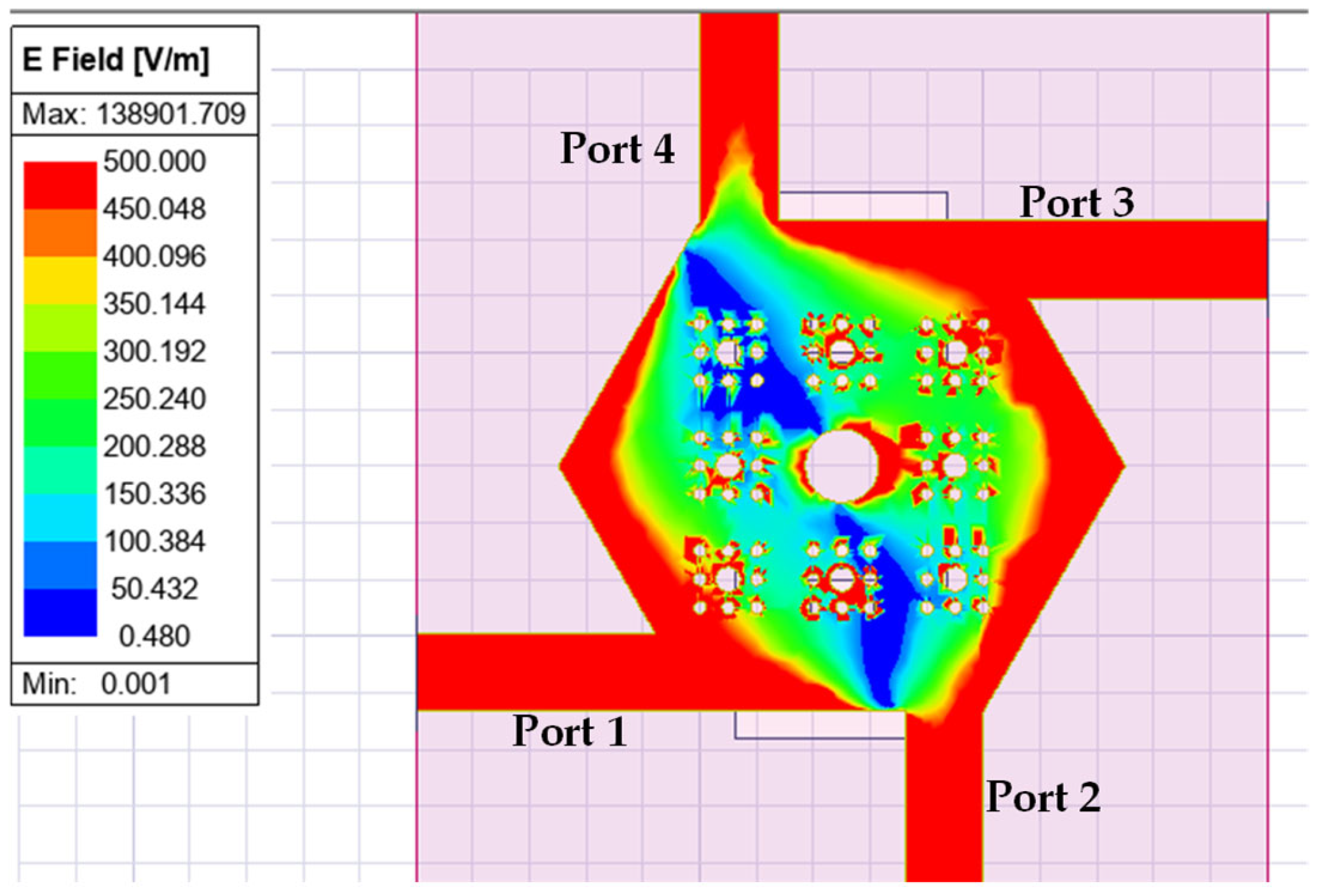

3. Modified Compact Hexagonal Crossover

3.1. Lower Band Transmission Zero

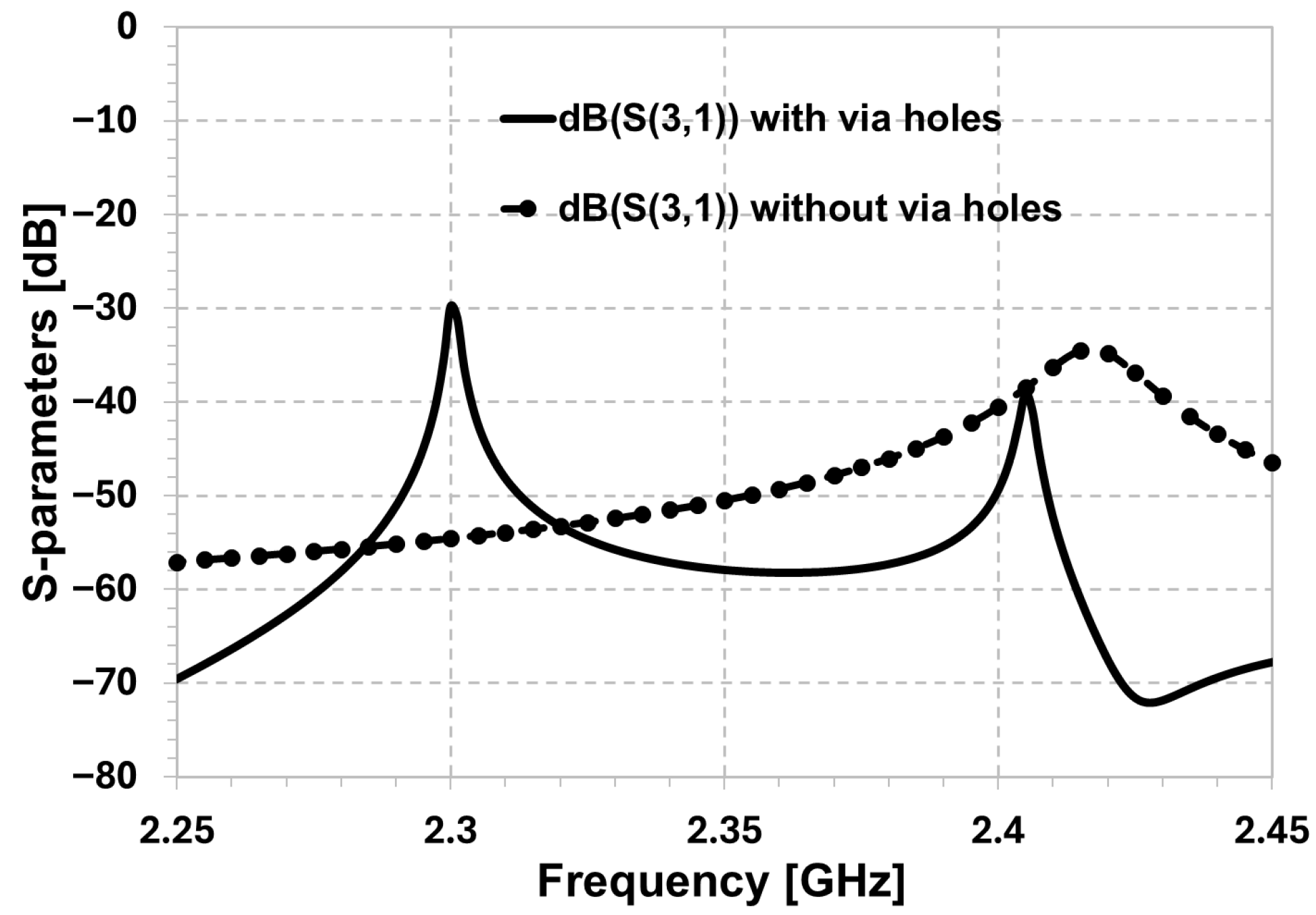

3.2. Grounded via Holes

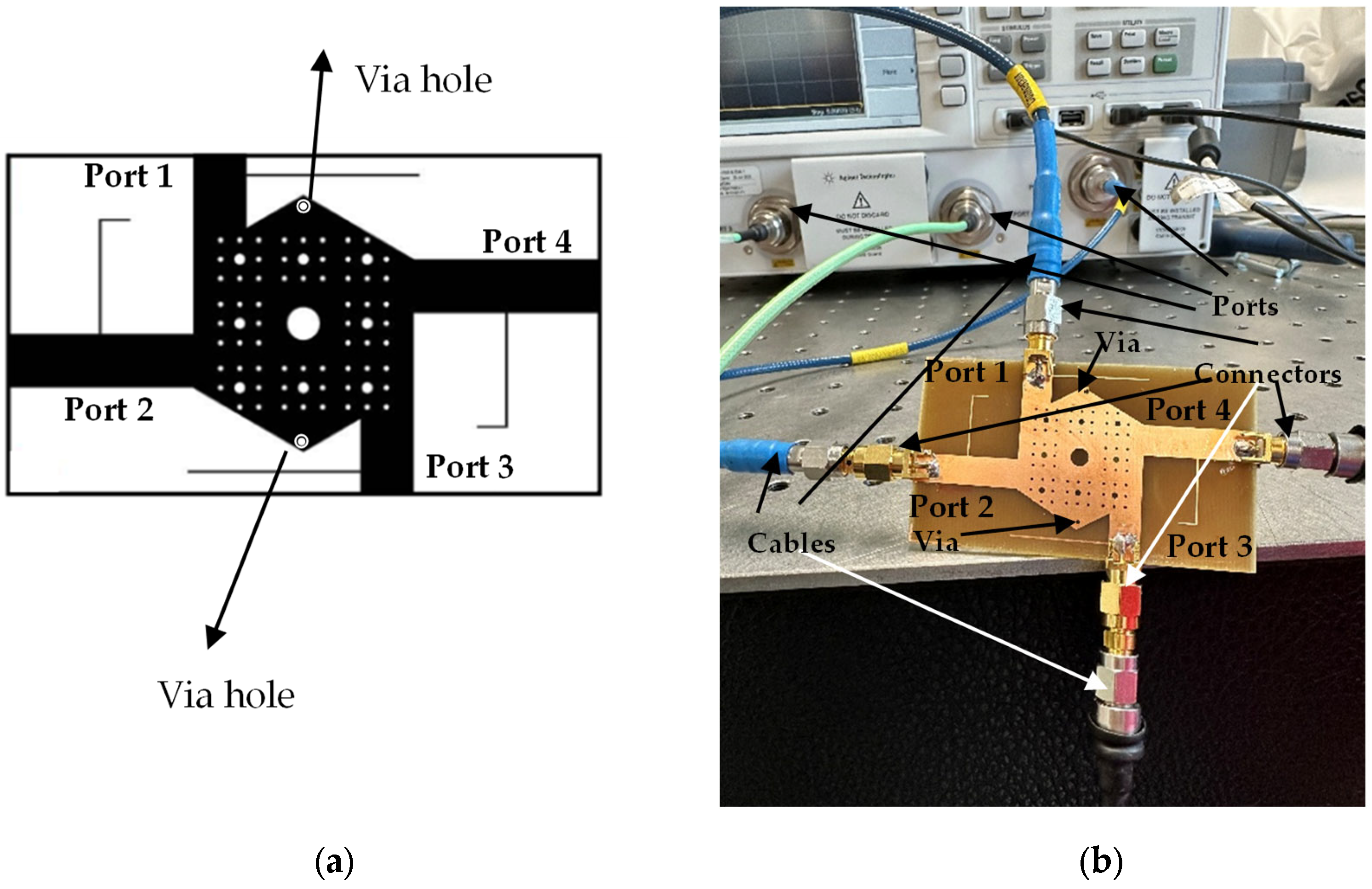

3.3. Modified Crossover

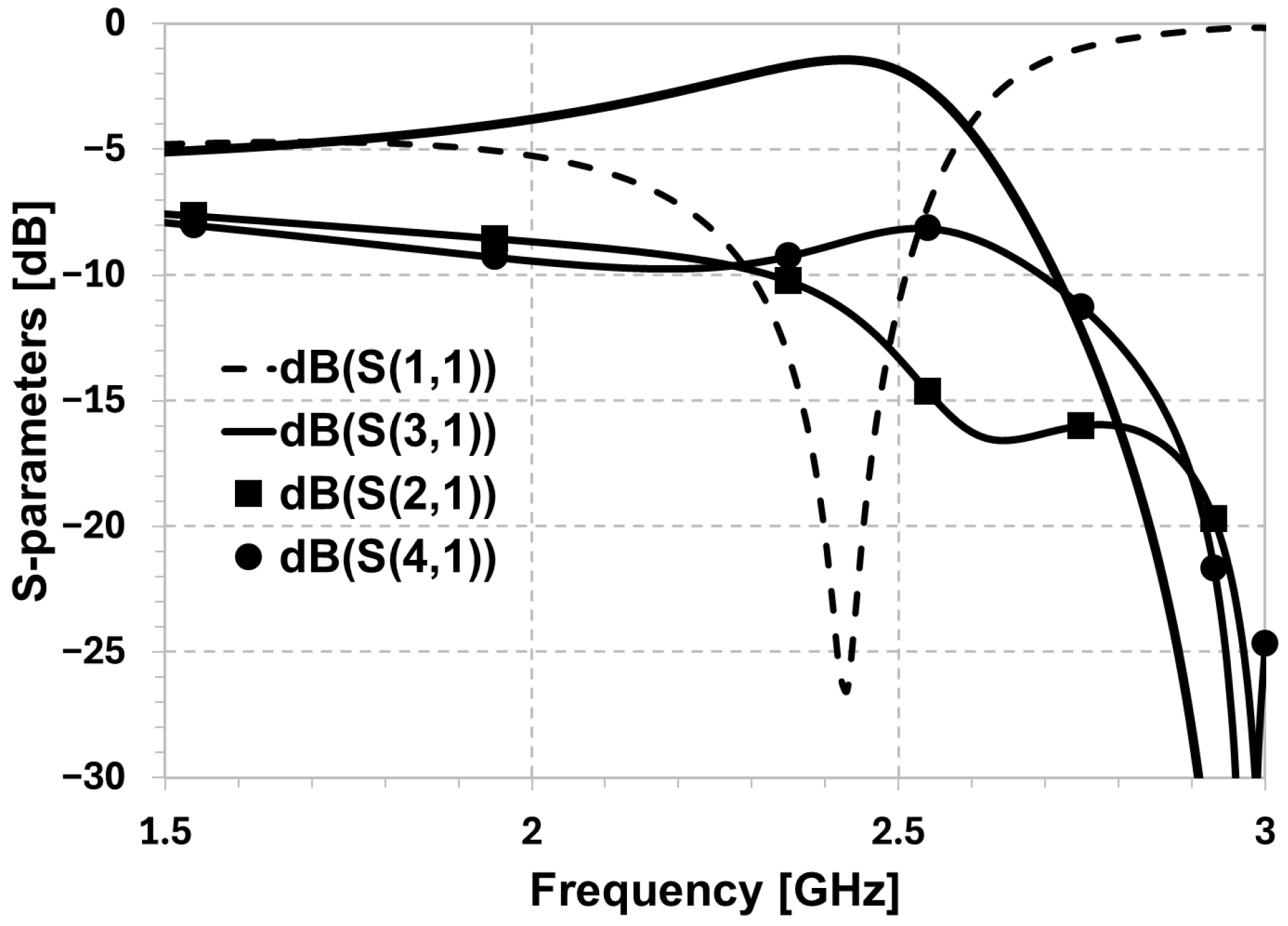

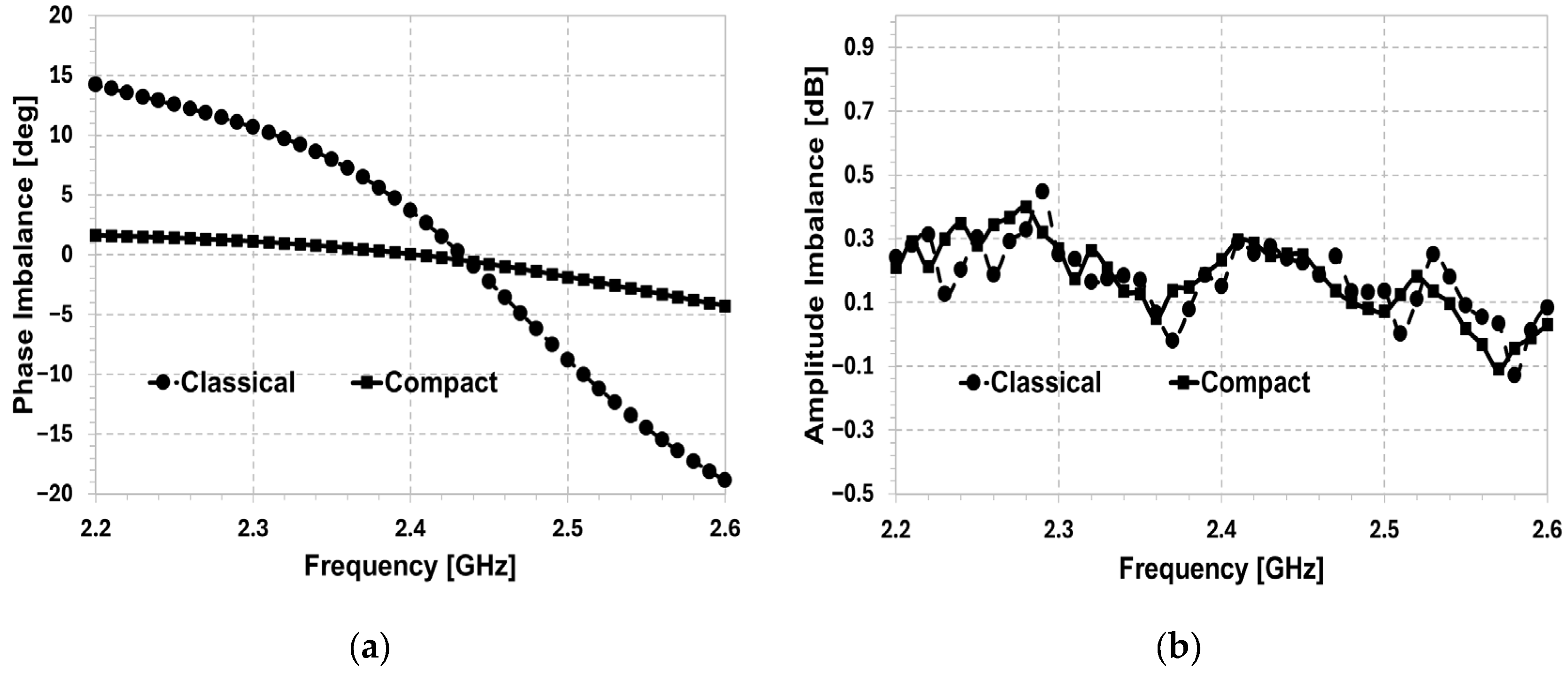

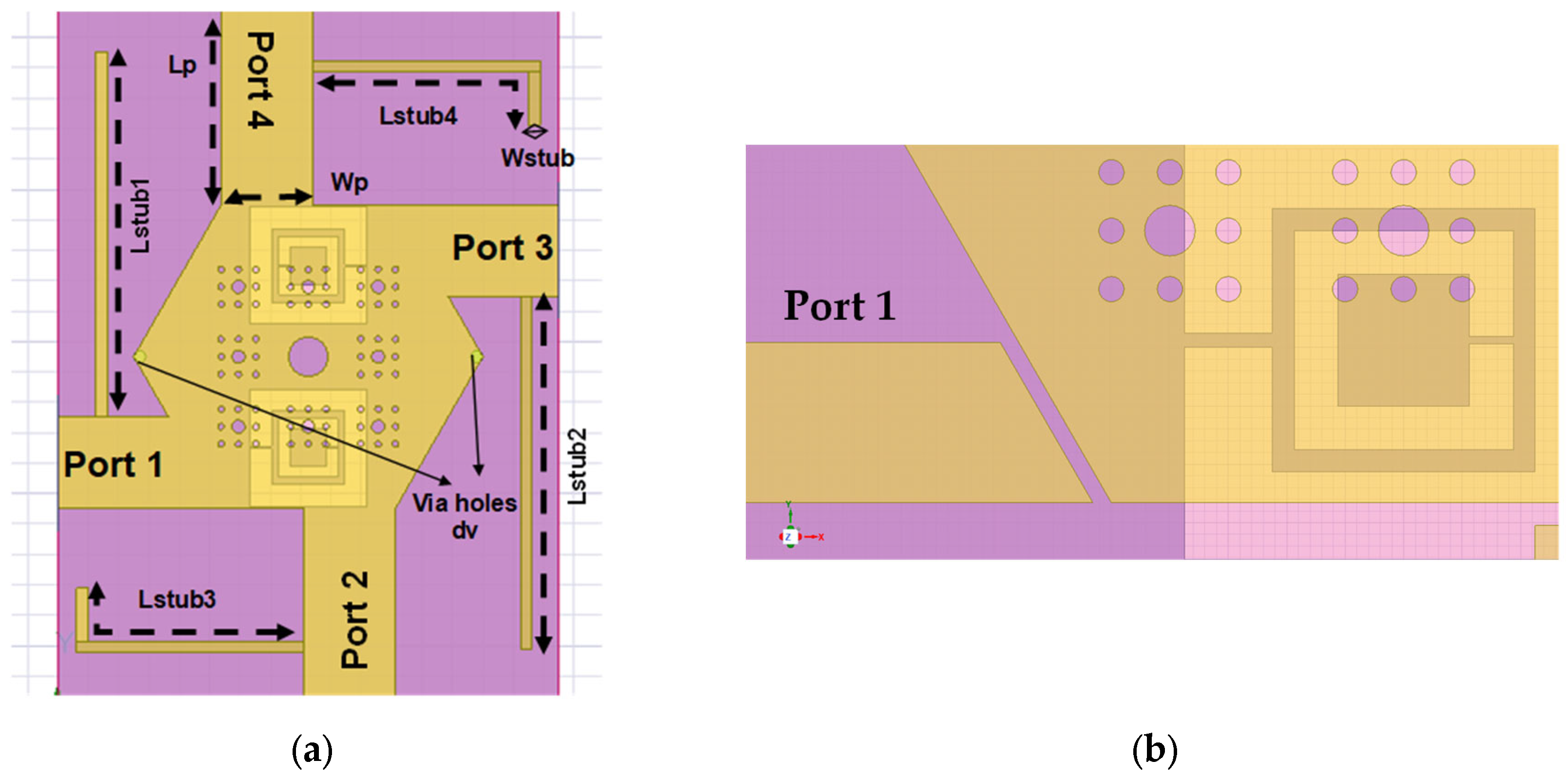

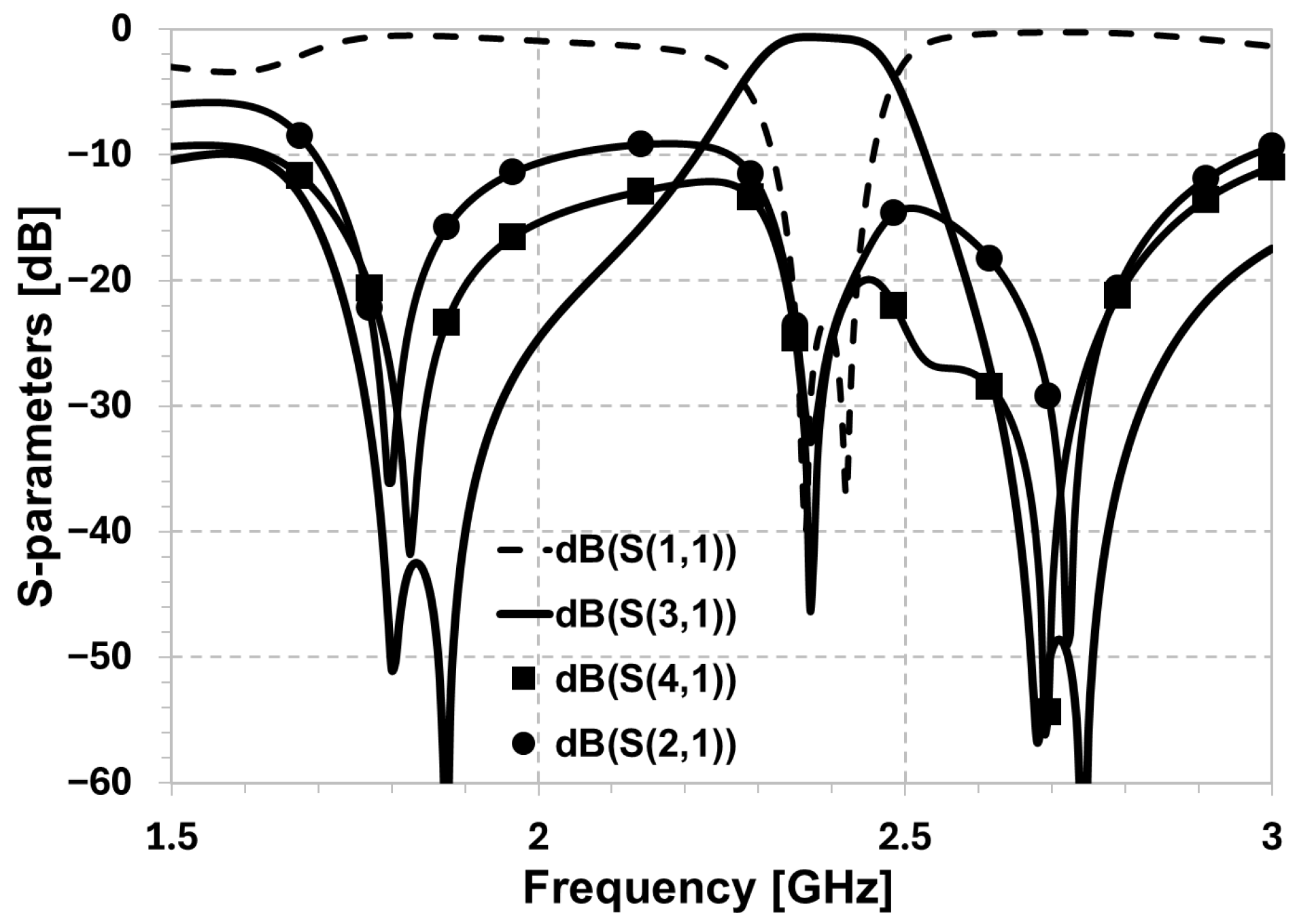

4. Response-Controlled Compact Hexagonal Crossover

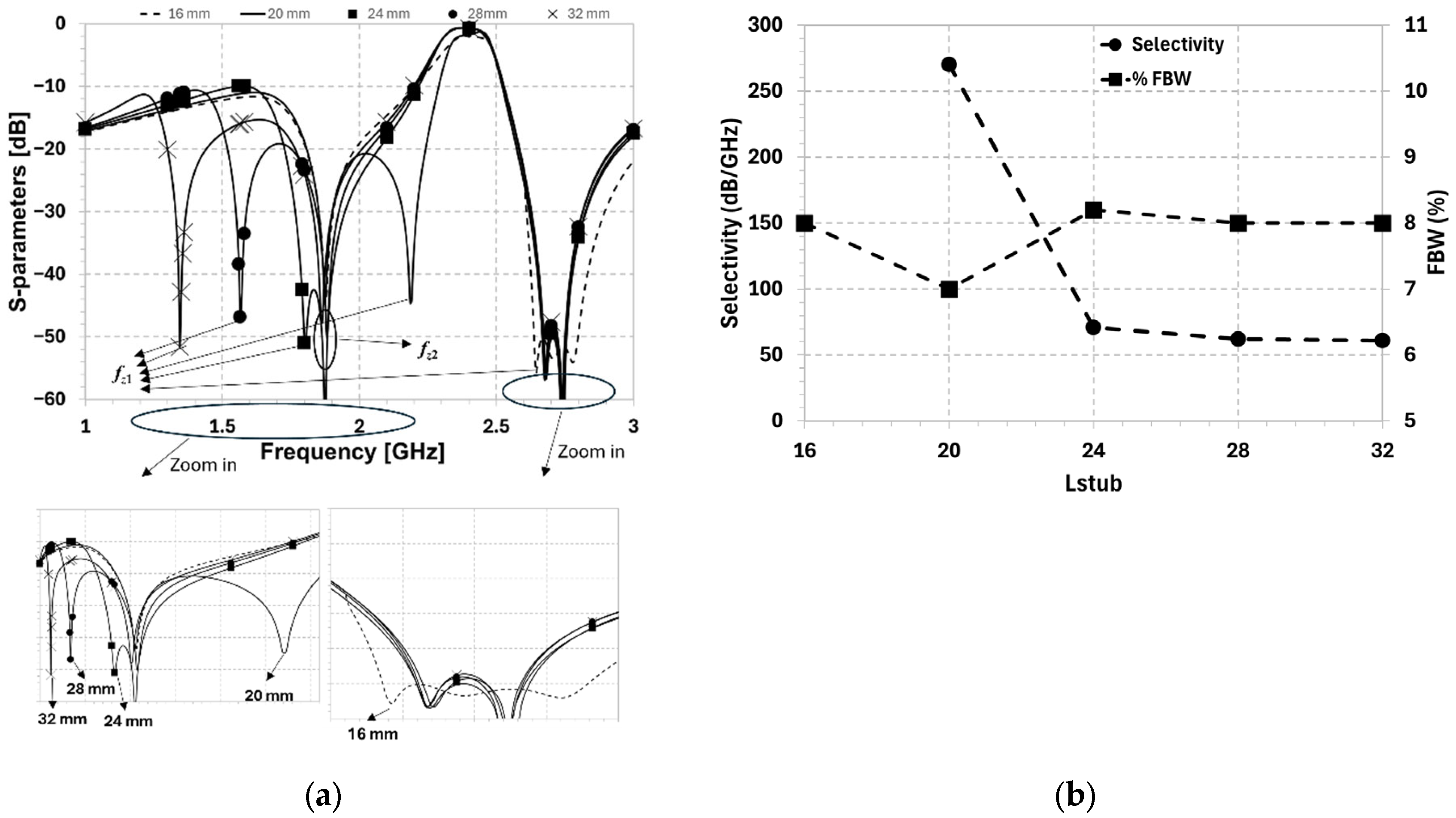

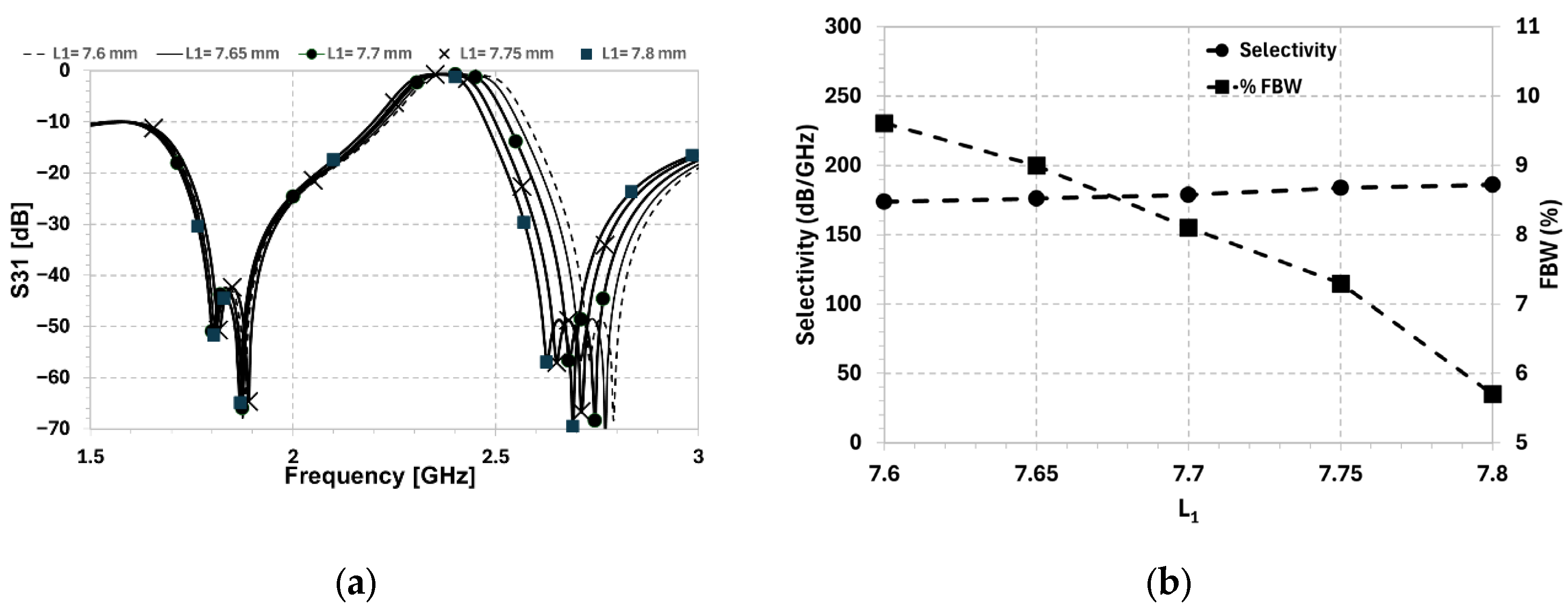

4.1. Loading Stubs: Selectivity Control

4.2. DGS: FBW Control

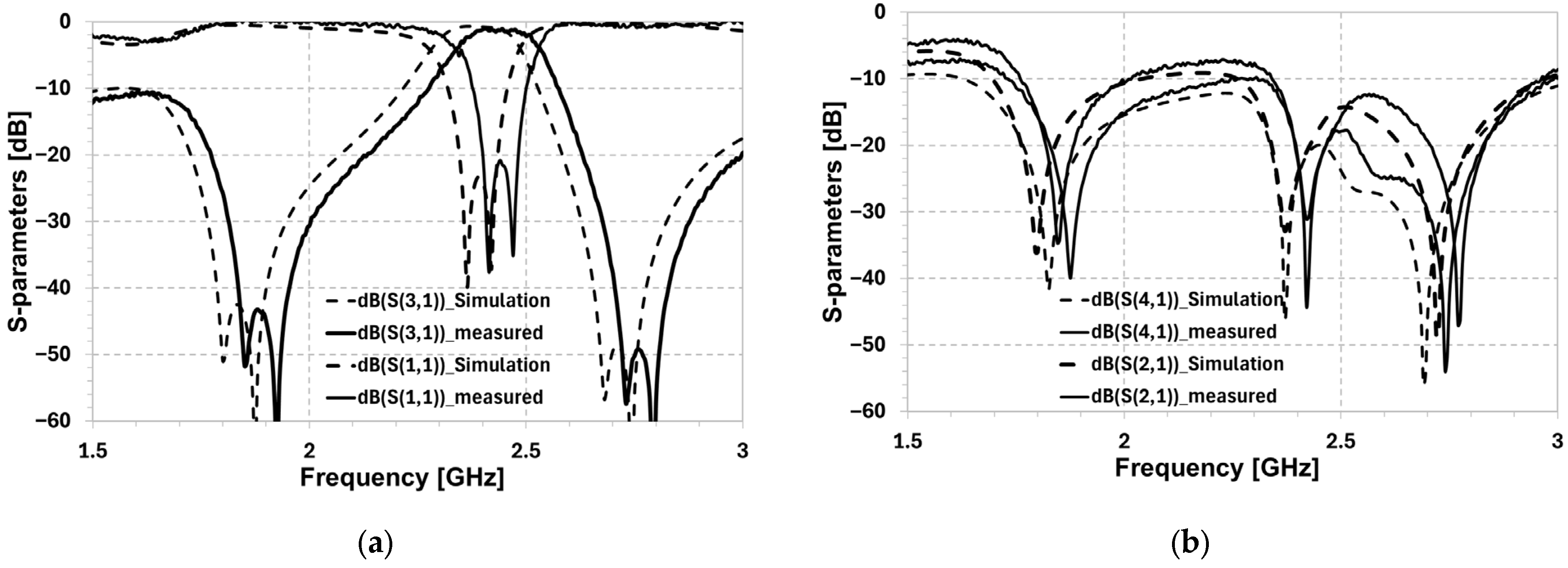

5. Results

6. Discussion

- fc (GHz): Center frequency.

- FBW (%): Fractional Bandwidth, calculated at the −3 dB insertion loss level.

- IL (dB): Insertion Loss (S31), measured at fc.

- Iso. (dB): Isolation, measured at fc (min (|S21|, |S41|)).

- RL (dB): Return Loss (S11), measured at fc.

- Size (mm2): Total footprint area.

- Complex.: The complexity. A qualitative assessment of fabrication difficulty (+ = complex, ++ = highly complex, e.g., SIW).

- Selectiv.: The Selectivity. A qualitative measure based on the number and proximity of transmission zeros to the passband (High, Moderate, and Low).

- Tunab.: The Tunability. A Binary indicator of frequency response adjustment capability (Yes/No).

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yerli, M.; Palandöken, M. A compact microstrip Planar crossover for LTE applications. Int. J. Adv. Nat. Sci. Eng. Res. 2023, 7, 473–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.K.; Kumar, P.; Ray, K.P.; Padhy, B.B. High Performance Low Cost Square Microstrip Crossovers. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE Wireless Antenna and Microwave Symposium (WAMS), Chennai, India, 5–8 June 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Zhang, Z.; Feng, Z.; Iskander, M.F. A compact wideband microstrip crossover. IEEE Microw. Wirel. Compon. Lett. 2012, 22, 254–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, Y.-H.; Lin, E.D.; Chen, Y.-Y. A Planar balanced crossover. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Tech. 2016, 64, 1812–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiou, Y.-C.; Lai, S.-W.; Kuo, J.-T. Analysis and design of double-ring crossover junction with arbitrary diagonal port impedances. In Proceedings of the 2009 Asia Pacific Microwave Conference, Singapore, 7–10 December 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Pang, Y.-H.; Li, J.-J. A Planar Wideband Balanced Crossover. IEEE Trans. Compon. Packag. Manuf. Technol. 2018, 8, 1807–1814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yerli, M.; Palandöken, M. Γ shaped slotted compact circular crossover for communication applications at 2.45 GHz. Int. J. Adv. Nat. Sci. Eng. Res. 2023, 7, 115–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henin, B.; Abbosh, A. Wideband planar microstrip crossover with high power handling capability and low distortion. Microw. Opt. Technol. Lett. 2012, 55, 439–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banat, M.A.; Dib, N.I. Design of miniaturized patch crossover based on superformula slot shapes. Int. J. Electr. Comput. Eng. 2022, 12, 5145–5152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nachouane, H.; Najid, A.; Tribak, A.; Riouch, F. Broadband 4 × 4 Butler matrix using wideband 90 hybrid couplers and crossovers for beamforming networks. In Proceedings of the 2014 International Conference on Multimedia Computing and Systems (ICMCS), Marrakech, Morocco, 14–16 April 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, B.; Zhang, G.; Zhou, X.; Li, N.; Tang, W.; Yang, J. Substrate-Integrated Waveguide Filtering Crossover Based on 3-D Assembly. IEEE Microw. Wirel. Technol. Lett. 2023, 33, 523–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, P.R.; Warrier, P.M.; Menon, S.K. Substrate Integrated Waveguide Based 4-Port Crossover for Beam-Forming Applications. In Proceedings of the Information Systems Design and Intelligent Applications, Visakhapatnam, India, 8–9 January 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, X.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, S.; Liu, H.; Gao, M.; Fang, S. A novel Balanced-to-Balanced filtering crossover with wideband isolation and Common-Mode suppression. Microw. Opt. Technol. Lett. 2024, 66, e70044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purnima, G.; Menon, S.K. Microstrip patch based high isolation planar crossover for beamforming applications. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International WIE Conference on Electrical and Computer Engineering (WIECON-ECE), Pune, India, 19–21 December 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Akra, M.; Issa, H.; Pistono, E.; Jrad, A.; Corrao, N.; Ferrari, P. Parallel-coupled Stub-loaded Resonator filters with wide spurious suppression. In Proceedings of the 2012 42nd European Microwave Conference, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 29 October–1 November 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammed, W.; Philippe, F.; Cedric, D. mm-wave Dual-Mode Grounded Microstrip Patch BandPass Filter on 55-nm BiCMOS. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE MTT-S International Microwave Filter Workshop (IMFW), Perugia, Italy, 17–19 November 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, H.; Wang, Y.; Abbosh, A.M. Broadband microwave crossover using parallel-coupled microstrip lines and short-ended stubs. IET Microw. Antennas Propag. 2014, 9, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Zhao, X.; Liu, X.; Shi, X. Analysis and design of compact planar crossover. In Proceedings of the 2015 Asia-Pacific Microwave Conference (APMC), Nanjing, China, 6–9 December 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Q.-Y.; Zhang, X.Y.; Gao, L. Novel Compact Planar Crossover With Bandpass Response Based on Cross-Shaped Resonator. IEEE Trans. Compon. Packag. Manuf. Technol. 2017, 7, 2018–2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Sun, S. Modified window shape-based crossover with enhanced bandwidth. Int. J. RF Microw. Comput.-Aided Eng. 2020, 31, e22503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karthikeyan, S.S. Compact dual-band substrate integrated waveguide crossover with high isolation. Prog. Electromagn. Res. Lett. 2019, 83, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.; Choi, J. Miniaturized multi-section crossover with open stub. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE International Symposium on Antennas and Propagation & USNC/URSI National Radio Science Meeting, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 19–24 July 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Z.-w.; Pang, Y.-h. Compact planar dual-band crossover using two-section branch-line coupler. Electron. Lett. 2012, 48, 1348–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna, I.S.; Barik, R.K.; Karthikeyan, S.S. Analysis and Design of a Planar Crossover for Dual-Frequency Applications. In Proceedings of the 2017 14th IEEE India Council International Conference (INDICON), Roorkee, India, 15–17 December 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, A.K.; Kumar, P.; Ray, K.P.; Padhy, B.B. Miniaturized Circular Slotted Crossovers with Defected Ground Structures. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Microwaves, Antennas, and Propagation Conference (MAPCON), Hyderabad, India, 9–13 December 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, Q.; Yang, N.; Chen, R.-S.; Huang, G.-L.; Chen, F.-C.; Wang, Y. Design of Filtering Crossover Based on 180 Filtering Couplers. IEEE Trans. Compon. Packag. Manuf. Technol. 2024, 14, 309–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Rx | Ry | D1 | L1 | W1 | S1 | S2 | S3 | Wp | Lp |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 | 26 | 2.6 | 7.5 | 1.45 | 0.25 | 0.125 | 0.375 | 2.75 | 8.4 |

| Rx | Ry | D1 | L1 | L2 | S1 | Lstub1 | Lstub2 | Lstub3,4 | dv | Wstub | Wp | Lp |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 28 | 29 | 2.6 | 7.7 | 3.85 | 0.15 | 24 | 23.75 | 18.5 | 0.8 | 0.75 | 6 | 7.3 |

| Ref. | Fc (GHz) | FBW (%) | IL (dB) | Iso. (dB) | RL (dB) | Size (mm2) | Complex. | Selectiv. | Tunab. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [14] | 2.4 | 12.5 | 0.55 | 35 | 28 | 253 | - | low | no |

| [17] | 2.4 | 12.5 | 0.5 | 15 | 22 | 31 × 31 | - | low | no |

| [18] | 2.4 | 25 | 0.5 | 20 | 15 | 39.4 × 27 | + | low | no |

| [19] | 2.4 | 4.4 | 1.46 | 23 | 20 | 21.6 × 31.6 | + | high | yes |

| [20] | 2.4 | 40 | 1 | 15 | 15 | 50 × 50 | + | moderate | no |

| [21] | 2.4 | 10.9 | 1 | 40 | 20 | 43.2 × 43.2 | ++ | low | yes |

| [22] | 2.5 | 22 | 0.5 | 20 | 20 | 29.3 × 9.3 | - | low | no |

| [23] | 2.4 | 3.35 | 1.35 | 20 | 30 | 60.3 × 48.9 | - | high | no |

| [24] | 2.4 | 3.75 | 0.88 | 30 | 20 | 32.4 × 37.2 | - | low | no |

| [25] | 2.5 | 9.35 | 0.58 | 25 | 30 | 35.5 × 35.5 | - | low | no |

| [26] | 2.4 | 10 | 1.8 | 15 | 10 | 90 × 45 | - | high | no |

| our work | 2.4 | 2.28–2.5 | 1 | 25 | 25 | 33 × 58 | - | high | yes |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kaddour, D.; Issa, H. Simple Planar Microstrip Crossover Coupler with Independent Control over Bandwidth and Selectivity. Electronics 2025, 14, 4737. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14234737

Kaddour D, Issa H. Simple Planar Microstrip Crossover Coupler with Independent Control over Bandwidth and Selectivity. Electronics. 2025; 14(23):4737. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14234737

Chicago/Turabian StyleKaddour, Darine, and Hamza Issa. 2025. "Simple Planar Microstrip Crossover Coupler with Independent Control over Bandwidth and Selectivity" Electronics 14, no. 23: 4737. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14234737

APA StyleKaddour, D., & Issa, H. (2025). Simple Planar Microstrip Crossover Coupler with Independent Control over Bandwidth and Selectivity. Electronics, 14(23), 4737. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14234737