Abstract

Federated learning (FL) offers a distributed approach for the collaborative training of machine learning models across decentralized clients while safeguarding data privacy. This characteristic makes FL well suited for privacy-sensitive fields such as healthcare and finance. However, addressing the heterogeneity caused by nonindependent and identically distributed (non-IID) data remains a significant challenge for traditional FL methods. To address these issues, the enhancing clustered federated learning with adaptive similarity (AS-CFL) algorithm, which dynamically forms client clusters based on model update similarity and uses a forward-incentive mechanism to improve collaborative training efficiency among similar clients, is proposed in this study. Experimental results on the MNIST and EMNIST datasets reveal that compared with baseline methods such as the CFL, IFCA, and FedAvg models, the AS-CFL algorithm achieves faster convergence—reducing the number of communication rounds by approximately 20%—while maintaining competitive accuracy, demonstrating its effectiveness in heterogeneous FL scenarios.

1. Introduction

Federated learning (FL) offers a distributed approach for the collaborative training of machine learning models across decentralized clients using a data-stay-local policy, making it suitable for privacy-sensitive areas such as healthcare and finance [1,2]. This method involves the use of distributed devices—including smartphones, IoT sensors, and edge servers—to enhance model performance [3] without exchanging raw data, complying with stringent privacy regulations such as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), thereby ensuring that data privacy and local processing are feasible [4,5,6].

However, managing the heterogeneity caused by nonindependent and identically distributed (non-IID) data poses significant challenges to traditional FL methods [7,8]. Non-IID data, resulting from variations in user preferences [9], device capabilities [10], or data collection methods, lead to differing client data distributions, causing divergence between local and global models; this results in reduced classification accuracy [11], slower convergence, and insufficient generalization [12,13]. In a typical image classification task [14,15,16], one client might predominantly handle daytime images, while another focuses on nighttime images, resulting in conflicting model updates that impact training effectiveness [17].

To address the challenge of statistical heterogeneity, a variety of strategies have been proposed in the literature [18]. These can be broadly categorized into three main directions: personalized federated learning, which aims to tailor models for individual clients [19]; meta-learning approaches, which train a global model that can be quickly adapted to local data; and federated multi-task learning, where different client groups are treated as related but distinct tasks [8]. Clustered Federated Learning (CFL), the focus of this paper, is a prominent and effective strategy within this third category, aiming to group clients with similar data distributions to train shared personalized models.

Clustered federated learning (CFL) addresses the heterogeneity caused by nonindependent and identically distributed (non-IID) data by grouping clients with similar data distributions to train personalized models for each cluster [12,20,21]. This approach involves the use of clustering mechanisms to identify specific data patterns, mitigating the impact of heterogeneity on model performance [22]. For example, clients with similar image types can form a cluster, enabling the development of a model tailored to their shared characteristics. However, existing CFL methods face several critical limitations that hinder their practical applicability. Firstly, static approaches like IFCA require the number of clusters to be predefined, which is impractical in real-world scenarios where the underlying client structure is unknown and may evolve [21]. Secondly, while dynamic methods exist, their computational complexity, particularly the need to compute a full client-to-client similarity matrix, often presents a significant scalability bottleneck [23]. Finally, most methods lack a formal mechanism to evaluate and incentivize client contributions to cluster quality, potentially leading to the formation of suboptimal or noisy client groups [24,25]. These gaps highlight the need for a framework like AS-CFL, which integrates dynamic adjustment, an incentive mechanism, and efficiency optimizations.

To address these challenges, the enhancing clustered federated learning with adaptive similarity (AS-CFL) algorithm, a novel framework that enhances the performance of the CFL algorithm through dynamic adjustment based on model update similarity, is proposed in this work. In this method, clients that enhance cluster model performance are prioritized, employing a forward-incentive mechanism to improve clustering accuracy and robustness. The method involves the use of an expectation-maximization (EM) framework [26]. To address data heterogeneity, the computational burden of similarity computation and model aggregation is reduced through low-rank matrix factorization, ensuring scalability for large neural networks [27]. Additionally, a privacy-enhancing noise mechanism is integrated to provide further privacy protection for sensitive applications such as medical diagnostics. Extensive experiments (Section 4) reveal that the AS-CFL algorithm achieves 90% peak accuracy in approximately 40 communication rounds, which is approximately 20% lower than the best CFL baseline, while maintaining competitive accuracy on the MNIST and EMNIST datasets. These results highlight the ability of the AS-CFL algorithm to adapt to complex data distributions, positioning it as a promising solution for real-world federated learning scenarios. This work provides a comprehensive, scalable, and privacy-preserving framework for the CFL algorithm that is suitable for domains that require robust handling of heterogeneous data.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews the related work in federated learning and its variants. Section 3 details our proposed AS-CFL methodology, including its core components. Section 4 presents the experimental setup, results, and analysis. Finally, Section 5 concludes the paper and discusses future research directions.

2. Related Work

2.1. Federated Learning (FL)

Federated Learning (FL), prototyped by the FedAvg algorithm, is a distributed learning paradigm that trains models on decentralized data while preserving user privacy [1,28]. This architecture has proven invaluable in sensitive domains like healthcare and finance. However, the performance of FedAvg degrades significantly under the statistical heterogeneity inherent in real-world data [7]. This heterogeneity, known as the non-independent and identically distributed (Non-IID) problem, is a primary obstacle in FL [8]. The literature categorizes this challenge into several types, including label distribution skew, feature distribution skew, and quantity skew, all of which cause “client drift” and hinder model convergence [13].

A significant body of research aims to mitigate this issue. Algorithm-based approaches modify the optimization process. For instance, FedProx introduces a proximal term to local objectives to limit drift [29]. SCAFFOLD utilizes control variates to correct for client-side optimization disparities [30], while FedDyn dynamically adjusts the local objective function to align with the global objective over time [31].

Another major direction is model-based personalization. Instead of a single global model, this paradigm provides tailored models. Techniques include meta-learning, as seen in Per-FedAvg [19]. Clustered Federated Learning (CFL), the focus of this work, has emerged as a particularly effective and practical strategy within this personalization domain.

2.2. Clustered Federated Learning (CFL)

Clustered Federated Learning (CFL) directly addresses data heterogeneity by partitioning the client population into clusters based on the similarity of their data distributions, and subsequently training a distinct personalized model for each cluster [12,20,21]. This paradigm avoids the negative interference caused by aggregating highly divergent model updates, a common issue in standard FedAvg. The success of CFL hinges on two key components: the metric used to measure client similarity and the algorithm used to form the clusters [12].

A foundational approach for measuring similarity is to use the cosine similarity of client model updates as a proxy for the underlying data distribution similarity [12]. This metric is robust to differences in the magnitude of updates and focuses on the directional alignment of gradients, which is indicative of shared data patterns. While effective, other metrics such as the L2 distance or even differences in model loss on a shared dataset have also been explored, each with different trade-offs in computational cost and representational power.

Existing CFL methodologies can be broadly categorized by their clustering strategy, with a clear evolution from static to dynamic approaches, as summarized in Table 1. Static clustering approaches, such as the seminal Iterated Federated Clustering Algorithm (IFCA) [21], established a foundational two-stage process: clients are first assigned to one of K clusters based on which cluster model performs best on their local data, after which each cluster model is updated using only the data from its assigned clients. The primary drawback of such static methods is the rigid assumption that the number of clusters, K, must be predefined and remains fixed throughout training. This is impractical in many real-world scenarios where the underlying structure of the client population is unknown and may evolve over time [32].

Table 1.

Summary of Existing Clustered Federated Learning Algorithms.

To overcome this limitation, a significant line of research has focused on dynamic clustering approaches. An early and influential method, FL + HC, employs hierarchical clustering on the server to dynamically form client groups without pre-specifying K [23]. While innovative, its reliance on constructing a full client-to-client similarity matrix results in an O(N2) computational complexity, which presents a major scalability bottleneck for systems with a large number of clients. Building on this, methods like AdaCFL have sought to improve efficiency by introducing a pre-clustering step to reduce the number of clients involved in the expensive hierarchical clustering phase. Other dynamic methods, such as Multi-center Federated Learning, have explored using K-Means, but this can be inefficient for the high-dimensional data of model updates [38] and is sensitive to initialization and outliers.

Further comparisons are warranted against other novel clustering strategies. For instance, some works propose static, pre-training clustering by analyzing data subspaces via principal angles [41]. This differs from AS-CFL, which performs dynamic, during-training adjustments based on model updates, allowing it to adapt to evolving client distributions. More recently, adaptive methods [42] like FedAC [40] have emerged, which also share the goal of dynamic clustering. AS-CFL is differentiated by two key contributions:

- (1)

- its superior scalability via low-rank matrix factorization () for similarity computation, compared to standard K-Means approaches

- (2)

- its unique positive incentive mechanism (Section 3.2.1), which adds a layer of performance-based quality control to cluster formation that distance-based methods lack.

Concurrent to improving adaptability, recent works have begun to address other critical challenges within the CFL framework. Recognizing that clustering can lead to performance disparities, fairness in CFL has become an important research topic, with methods like FAIR-CFL incorporating fairness constraints to ensure that all client groups achieve a baseline level of performance. Similarly, as CFL is deployed in sensitive applications, privacy has been a key concern, leading to the development of Privacy-Preserving CFL frameworks that integrate formal privacy mechanisms like differential privacy [43] with the clustering process [22]. Furthermore, the impact of data imbalance [44] within clusters has been specifically targeted by approaches such as Weighted CFL [37].

Despite this rich body of work, a persistent challenge remains in finding a solution that is simultaneously adaptive, computationally scalable, communication-efficient, and robust to both data heterogeneity and imbalance. Many dynamic methods are computationally heavy, while more efficient methods may sacrifice clustering accuracy. This highlights the need for a framework like our proposed AS-CFL, which aims to strike a better balance across these multifaceted challenges.

2.3. Communication Efficiency in Federated Learning

Communication overhead is a primary bottleneck in FL. Classic client-side compression techniques include quantization (QSGD) [45] and sparsification (Deep Gradient Compression) [46]. Another popular approach is federated distillation (FedGKT) [47]. The advent of large foundation models has spurred a highly influential trend in the use of parameter-efficient fine-tuning (PEFT) methods. FedLoRA, for example, adapts techniques like Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA) to FL, where clients only train and transmit small adapter matrices. Our work contributes differently: our application of low-rank factorization is on the similarity matrix to reduce the computational complexity of the clustering process on the server side [27].

2.4. Client Selection and Contribution Evaluation

In large-scale FL systems, client selection is crucial [48]. Beyond random selection, intelligent strategies have been developed. Power-of-Choice demonstrated that allowing clients with higher local loss to self-select can accelerate convergence [24]. Systems like Oort prioritize clients based on both statistical utility and system performance [25], while methods like q-FFL focus on ensuring fairness [49]. More recently, Active Federated Learning frameworks have been proposed, where the server actively queries the most informative clients to improve model training with fewer participants [50]. Our positive incentive mechanism is related to this line of work. However, unlike most methods focused on improving a single global model, our mechanism is uniquely designed to evaluate a client’s contribution to a specific cluster, directly improving the quality and cohesion of the personalized cluster models [25].

3. Methodology

The similarity-adaptive clustered federated learning (AS-CFL) algorithm, which is designed to address non-IID challenges in federated learning through a combination of similarity-adaptive clustering, positive incentives, low-rank matrix factorization, and a privacy-preserving aggregation method, is introduced in this section [8,12,23]. The methodology is structured to balance classification accuracy, computational scalability, and privacy preservation, making AS-CFL suitable for large-scale, privacy-sensitive applications [2,51].

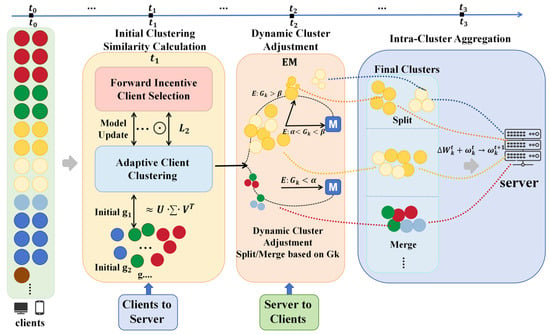

Figure 1 illustrates the three-stage workflow of the AS-CFL system. In Stage 1 (Initial Clustering), all clients perform local training and transmit their model updates to the central server, which then computes an adaptive similarity matrix and performs an incentive-based initial clustering. Stage 2 (Dynamic Cluster Adjustment) entails a cluster refinement process, where the server dynamically splits or merges the initial clusters based on the dispersion-to-separation ratio to optimize the cluster structure. Finally, in Stage 3 (Intra-Cluster Aggregation), the server independently aggregates the model updates within each refined cluster to generate personalized models for the subsequent round. This entire three-stage process is reiterated in each communication round, enabling AS-CFL to dynamically adapt to data heterogeneity and improve both clustering efficiency and model performance [20,37,52].

Figure 1.

Framework of the similarity-adaptive clustered federated learning (AS-CFL) algorithm. The different colors represent distinct client clusters, which are dynamically formed, adjusted (split/merged), and aggregated throughout the three-stage process.

To precisely articulate the design of the proposed AS-CFL framework, a set of key mathematical notations is used throughout the methodology. For clarity and easy reference, these symbols and their descriptions are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

List of key notations and their descriptions.

3.1. Problem Formulation

Consider a federated learning system with clients, each containing a non-IID dataset of size . The objective is to partition the clients into clusters, where each cluster trains a personalized model with parameters to minimize the aggregated loss, as follows:

where is the set of clients in cluster , is the total data size in the cluster, and is the local loss for client , with a loss function. The challenge lies in determining the optimal number of clusters, , and assigning clients to clusters based on their data distributions, which are not directly accessible due to privacy constraints.

3.2. Initial Clustering with Adaptive Similarity

3.2.1. Similarity Matrix and Incentive Mechanism

The AS-CFL algorithm measures the similarity between clients based on the cosine similarity of their model updates, which serves as a proxy for the similarity of data distributions [12]. For clients and , with local model updates after one or more local training epochs, the cosine similarity is defined as follows:

where represents the dot product, and is the L2 norm. Cosine similarity is robust to differences in update magnitude and is focused on directional alignment, which is indicative of shared data patterns. To enhance clustering accuracy, the AS-CFL algorithm employs a positive incentive mechanism [24]. A client is assigned to cluster if its inclusion improves the cluster’s model performance on a validation set, as follows:

Here, the performance of the temporarily aggregated model, which includes client i, is evaluated on a small, publicly available proxy dataset () held by the server. In our experiments (using MNIST/EMNIST), this was a randomly sampled, IID subset of the global test set, containing data from all classes. Using an IID proxy set is suitable and necessary, as it provides a neutral benchmark to measure the cluster’s generalization capability without introducing new biases. This dataset is entirely independent of any client’s private data, thus preserving the core privacy principles of federated learning. This mechanism ensures that clusters form with clients that contribute positively to the model’s performance, thereby reducing the inclusion of outliers or clients with divergent data distributions. The threshold is fine-tuned via cross-validation to balance cluster cohesion and inclusivity.

To ensure computational feasibility, a greedy candidate pruning strategy is adopted: for each candidate cluster, only the top 20% most similar clients are evaluated on the server-held validation set; the search stops at the first client that fails to improve accuracy by 3%. The temporary aggregate model is created using a single weighted average, eliminating the need for retraining. This reduces the evaluation cost from O(S2) to O(S) forward passes per round while maintaining the incentive effect.

3.2.2. Low-Rank Approximation and Greedy Clustering

The AS-CFL algorithm constructs a similarity matrix, , where each element . Computing directly for large and high-dimensional models is computationally expensive, with a complexity of , where is the model dimension [52]. To address this, the AS-CFL algorithm applies low-rank matrix factorization to approximate as follows:

where , , and is the rank. This factorization is applied to a subset of model parameters, specifically weights near the output layer, which are most indicative of task-specific patterns. The computational complexity is reduced to , enabling scalability for large client populations [53]. The rank, r, is selected based on an explained-variance ratio ≥ 95% on the output-layer weights, ensuring that task-specific information is preserved while reducing computations by an order of magnitude. Initial cluster generation proceeds in two steps:

- (i)

- a representativeness score is computed for each unassigned client (data-size weighted centrality);

- (ii)

- the highest-scoring client is selected as the seed, it is expanded with the greedy incentive test until no more positives are found, and this process is repeated until all the clients are assigned.

Thus, the initial K is data-driven and requires no preset value.

3.2.3. Data Imbalance Adjustment

To address data imbalance due to varying dataset sizes among clients, the AS-CFL algorithm adjusts the number of local training iterations for each client as follows:

where is the number of local epochs for client , and BS is a fixed batch size [23]. This ensures that clients with smaller datasets perform more iterations, helping sufficiently with model updates and mitigating bias toward clients with larger datasets [37]. The ceiling function ensures that at least one epoch is performed, maintaining training stability.

Additionally, a minimum of 10 local epochs is enforced (as detailed in Algorithm 1, line 5) to ensure that each client’s model updates are sufficiently meaningful for the subsequent aggregation process, thereby preventing underfitting, especially for clients with larger datasets that would otherwise perform very few epochs.

| Algorithm 1: AS-CFL |

| Input: Initial global model parameters , set of all clients total rounds , batch size . Output: A set of personalized cluster models 1. Server executes: 2. Initialize cluster models for the first round: 3. for each communication round do: 4. Broadcast cluster models to clients in their 5. for each client in parallel do 6. Receive its cluster model 7. Compute local epochs 8. Perform local training for () epochs to get local model 9. Compute model update 10. Send to the server. 11. end for 12. Server executes: 13. // --- Stage 1: Initial Clustering --- 14. Receive all model updates . 15. Compute similarity matrix using cosine similarity on with low-rank factorization. 16. Perform initial greedy clustering using the positive incentive mechanism to form initial clusters 17. // --- Stage 2: Dynamic Cluster Adjustment --- 18. Let final clusters . 19. for each cluster } do 20. Compute the dispersion-to-separation ratio 21. if then Split and update . 22. else if then Merge and update . 23. end if 24. end for 25. // --- Stage 3: Intra-Cluster Aggregation --- 26. for each final cluster do 27. // Add noise to updates before aggregation 28. for each final cluster do 29. let = {} 30. for each client i in do 31. 32. add to 33. // Aggregate noisy updates 34. 35. end for 36. end for 37. Return final personalized models {} |

3.3. Dynamic Cluster Adjustment

To adapt to different data distributions, the AS-CFL algorithm dynamically adjusts the number of clusters using an expectation-maximization (EM) algorithm. In the E-step, clients are reassigned to clusters on the basis of the shortest distance to cluster centers, as follows:

where if the client is assigned to cluster ; otherwise, is the current center of cluster . In the M-step, cluster centers are updated as a weighted average of client updates as follows:

The EM process iterates until convergence, typically within 5–10 iterations, to ensure stable cluster assignments. Instead of the ratio, the dispersion-to-separation ratio is employed. For each client, , the ratio is expressed as follows:

where Equation (8) defines the dispersion-to-separation ratio for clusters: the numerator measures the average intracluster distance, reflecting how tightly clients aggregate around their centroid, whereas the denominator indicates the Euclidean distance to the nearest foreign centroid, quantifying intercluster separation. A large value indicates a scattered cluster near its neighbor, whereas a small value signifies a compact cluster far from others. Specifically, we introduce a dispersion-to-separation ratio Equation (8) to evaluate the structural stability of each cluster. When the value of exceeds a predefined splitting threshold β (β = 0.8), it indicates either high internal dispersion within the cluster or poor separation from other clusters. In such cases, cluster k will be split into smaller sub-clusters. Conversely, if the value of falls below a predefined merging threshold ( = 0.2), implying high internal cohesion and good separation from other clusters, it may be merged with a nearby similar cluster to prevent over-segmentation and optimize the overall structure. Specifically, for a cluster with centroid S, these terms are calculated as follows: The intra-cluster dispersion, , is calculated as the average Euclidean distance between the model updates of clients in the cluster and their centroid:

The inter-cluster separation, , is defined as the Euclidean distance from the cluster’s centroid to the nearest other cluster’s centroid :

3.4. Intra-Cluster Aggregation

After the clusters have been dynamically adjusted in Stage 2, the final step in each communication round is to aggregate the model updates within each refined cluster. This process generates personalized models tailored to the specific data characteristics of each group for the next round.

The model for each cluster is updated by applying the weighted average of the local updates from its constituent clients to the cluster’s model from the previous round, . The weight for each client is proportional to the size of its local dataset, ensuring that clients with more data have a greater influence on the resulting cluster model. The update rule is defined as follows:

This intra-cluster aggregation strategy is a cornerstone of the CFL approach [12,22]. By aggregating updates only from clients with similar data distributions (as determined by the clustering stages), AS-CFL creates multiple specialized models instead of a single global one. This directly mitigates the negative impact of non-IID data, as the conflicting gradients from highly dissimilar clients are isolated in different clusters. This leads to more stable and accurate personalized models for each client group. These newly updated cluster models, {}, are then distributed back to the clients in their respective clusters, initiating the next communication round.

3.5. AS-CFL Algorithm Workflow

To seamlessly adapt to time-varying non-IID data, the AS-CFL algorithm compresses the entire training loop into a single-round closed pipeline. After broadcasting the current cluster models, the server allows each client to perform an adaptive number of local steps, calculated as the ceiling of the batch size divided by the local data size, and return low-rank compressed updates. The server then reconstructs the cosine similarity matrix, only retaining clients that improve validation accuracy through a positive incentive filter. It automatically splits or merges clusters based on the dispersion-to-separation ratio and injects calibrated Gaussian noise to each client’s update vector before aggregating them in a privacy-preserving manner. The refreshed cluster models are immediately redistributed, forming an iterative cycle that repeats until global convergence.

3.6. Complexity Analysis

A critical aspect of our AS-CFL algorithm is the management of computational costs, particularly when compared to the reduction in communication rounds. The algorithm’s computational load is partitioned between the clients and the server.

On the client side, the computational overhead is identical to that of standard FedAvg or CFL. All clustering-related operations, including similarity calculation and dynamic adjustment, are performed entirely on the server. As such, the client’s only tasks are to receive its cluster model and perform local training to compute its model update (). Our AS-CFL algorithm introduces no additional computational overhead to the clients.

On the server side, the primary computational bottleneck in traditional dynamic CFL approaches is the calculation of the full client-to-client similarity matrix, which has a prohibitive complexity of , where is the number of clients and is the model dimension. Our AS-CFL algorithm directly addresses this bottleneck. As detailed in Section 3.2.2, we employ low-rank factorization, which reduces the complexity of this critical step to , where is the rank . The other server-side operations, such as the positive incentive mechanism (requiring forward passes on the small proxy dataset) and the Gk ratio calculation (operating on clusters, ), are highly efficient in comparison.

This analysis demonstrates that AS-CFL makes a favorable trade-off: it introduces a manageable and highly scalable server-side computational cost per round, in exchange for the 20% reduction in total communication rounds. This highlights the algorithm’s overall efficiency and its suitability for large-scale, real-world deployments.

4. Experiments

4.1. Experimental Setup

To evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed AS-CFL algorithm, experiments were conducted on two benchmark datasets: the MNIST and EMNIST datasets. These datasets were modified to simulate nonindependent and identically distributed (non-IID) conditions, reflecting the heterogeneity of real-world data [7].

The AS-CFL algorithm is evaluated on two benchmark datasets, the MNIST (10 classes, 60,000 training images) and EMNIST (62 classes, 671,585 training images) datasets, modified to simulate non-IID conditions. Data are partitioned across 20 clients using Dirichlet distributions with concentration parameters , where lower values indicate greater heterogeneity. To simulate data imbalance, the client dataset sizes range from 10% to 60% of the total samples. The feature distribution skew [54,55] is introduced by applying random image rotations (0°, 90°, 180°, 270°) to each client’s data, mimicking real-world variations in data collection [17].

The hyper parameters include a learning rate of 0.1 (decayed by 0.99 per round), a batch size of 32, and ~10 local epochs per round. The differential privacy parameters are set to and , with the noise scale, calculated accordingly. The baselines include the FedAvg model, which aggregates all client updates into a single global model; the CFL approach, which uses cosine similarity for clustering with a fixed number of clusters; and the IFCA, which alternates between clustering and model optimization with fixed clusters.

The evaluation metrics include classification accuracy on the test sets (10,000 images for the MNIST dataset and 112,800 images for the EMNIST dataset) and convergence speed (the number of rounds required to reach 90% peak accuracy). Experiments are conducted in a simulated FL environment using PyTorch (Version 1.13.1), with 20 clients and 100 communication rounds.

All server-side computations were performed on a system equipped with an NVIDIA RTX 3080 GPU and an Intel Core i7-12700K CPU.

4.2. Results and Analysis

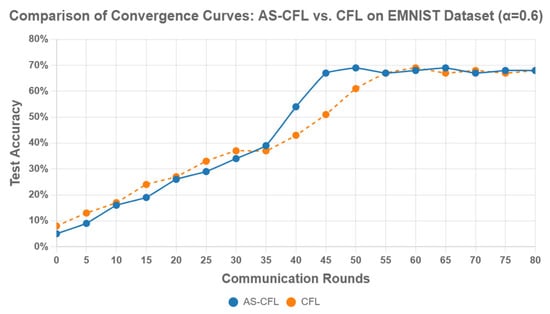

4.2.1. Convergence Speed

The convergence behavior of the AS-CFL and CFL algorithms on the EMNIST dataset (α = 0.6) is shown in Figure 2. The figure reveals two distinct learning patterns. The AS-CFL algorithm demonstrates a stable learning trajectory with a faster convergence rate, steadily improving its accuracy and reaching near-convergence in approximately 35-45 rounds via a sharp acceleration phase.

Figure 2.

Comparison of convergence curves between the AS-CFL and CFL algorithms.

In contrast, the baseline CFL, which utilizes a fixed clustering approach, exhibits a more gradual but less efficient convergence behavior. It progresses steadily but slower overall, eventually reaching a similar accuracy level after more rounds. While CFL achieves comparable results, its learning process is more predictable yet slower than AS-CFL.

This comparison highlights a key advantage of AS-CFL: its dynamic clustering and incentive mechanisms not only lead to faster convergence but also promote a more stable and reliable training process compared to methods with fixed clustering.

4.2.2. Classification Accuracy

The results, as presented in Table 3, reveal a nuanced performance landscape. At lower levels of data heterogeneity (α = 0.8 on MNIST and EMNIST), the AS-CFL algorithm demonstrates comparable or slightly lower accuracy than the baseline CFL, which performs well in simpler conditions. However, as data heterogeneity increases (i.e., α decreases), AS-CFL’s performance degrades more gracefully than all baselines. It surpasses CFL and shows increasingly superior accuracy in highly heterogeneous settings. For instance, on MNIST at α = 0.4, AS-CFL achieves 0.910, which is notably higher than CFL’s 0.905.

Table 3.

Classification Accuracy Under Varying Levels of Data Heterogeneity.

Significantly, both clustering methods, AS-CFL and CFL, consistently and substantially outperform FedAvg and IFCA, especially in non-IID settings. On MNIST with α = 0.4, FedAvg’s accuracy drops to 0.805. This trend is even more pronounced on the challenging EMNIST dataset, where at α = 0.4, AS-CFL’s accuracy of 0.682 is substantially higher than CFL’s 0.675, while FedAvg’s performance plummets to 0.500. This robust performance demonstrates that AS-CFL’s dynamic mechanisms are highly effective at mitigating the severe negative impacts of strong non-IID data, leading to more stable and accurate personalized models in challenging real-world scenarios.

4.2.3. Communication Efficiency and Robustness

Communication Efficiency: Compared with the CFL algorithm, the AS-CFL algorithm reduces communication rounds by 20% because its efficient clustering minimizes unnecessary client interactions. Low-rank aggregation reduces the average uplink traffic per round by approximately 30% (from 28.3 MB to 19.8 MB, averaged over 3 runs), indicating scalability in bandwidth-constrained environments. Compared with FedAvg, the AS-CFL algorithm achieves a 40% reduction in total communication cost, defined as the number of transmitted parameters.

Robustness Analysis: The AS-CFL algorithm is tested under client dropout conditions (10% random dropout per round). The accuracy remains stable (0.905 vs. 0.908), as the EM algorithm dynamically reassigns clients, and low-rank aggregation mitigates missing updates. This robustness enhances the applicability of the AS-CFL algorithm under unreliable network conditions.

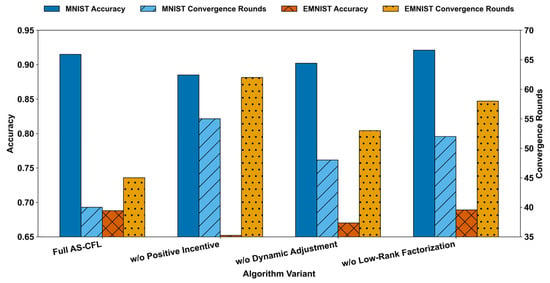

4.3. Ablation Study

To validate the necessity of each key component in the AS-CFL algorithm, experiments are conducted in which one component is removed at a time, and the effects on classification accuracy and convergence speed are evaluated, with the results presented in Figure 3 and Table 4. The experiments are performed on the MNIST and EMNIST datasets under non-IID conditions with the Dirichlet parameter of α = 0.6. The variants are as follows:

Figure 3.

Ablation Study: Accuracy (Left) and Convergence Rounds (Right) by Component.

Table 4.

Ablation Study Results on the MNIST and EMNIST Datasets.

- w/o Positive Incentive: The positive incentive mechanism is removed, and clients are assigned solely based on similarity without performance validation.

- w/o Dynamic Adjustment: Dynamic cluster adjustment using the EM algorithm and ratio is disabled, fixing the number of clusters to an initial value.

- w/o Low-Rank Factorization: The full similarity matrix is computed without low-rank approximation, increasing the computational overhead.

The results reveal that removing the positive incentive mechanism causes the greatest decrease in accuracy (3.4% on the MNIST dataset and 3.5% on the EMNIST dataset) and convergence speed (37.5% more rounds on the MNIST dataset), as it allows the inclusion of divergent clients, which degrades cluster quality. Without dynamic adjustment, the accuracy decreases by 1.7% on the MNIST dataset because of suboptimal cluster granularity in heterogeneous settings. Excluding low-rank factorization results in a marginal accuracy improvement (e.g., from 0.915 to 0.921 on MNIST), as the full similarity matrix provides more precise client relationship information. This is an expected finding. However, our core argument is that this tiny 0.6% accuracy gain comes at a disproportionately massive cost to efficiency (a 30% increase in required convergence rounds, from 40 to 52, as shown in the table). The purpose of low-rank decomposition is not to increase accuracy, but to make the clustering process computationally scalable. This highlights the critical role of low-rank approximation in balancing performance and computational scalability. These decreases demonstrate that each component is essential for AS-CFL performance, with synergistic effects enabling robust handling of non-IID data.

4.4. Hyperparameter Sensitivity Analysis

The sensitivity of the AS-CFL algorithm to key hyperparameters is analyzed to demonstrate its robustness across varying conditions. Experiments are conducted on the MNIST dataset unless otherwise specified.

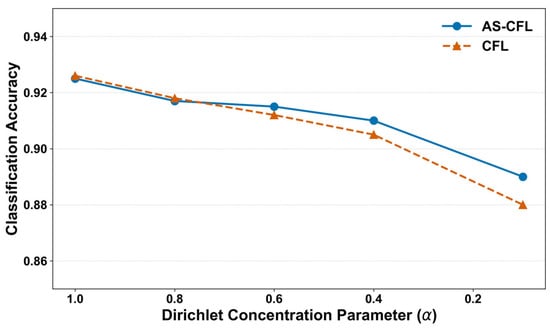

4.4.1. Impact of Dirichlet Concentration Parameter

The Dirichlet concentration parameter α is critical for controlling the degree of non-IID heterogeneity in our experiments; a lower α value indicates a higher data skew across clients. Figure 4 presents the performance of AS-CFL and the baseline CFL across a wide range of α values on the MNIST dataset.

Figure 4.

Classification Accuracy vs. Heterogeneity Level (α).

The results show two key trends. First, as expected, the accuracy of both algorithms degrades as heterogeneity increases (as decreases), confirming the challenge posed by non-IID data. Second, and more importantly, the performance of AS-CFL degrades more gracefully than that of CFL. At low heterogeneity (α = 1.0), CFL holds a marginal advantage (0.926 vs. 0.925). However, as the data skew becomes more severe, AS-CFL’s dynamic adjustment capabilities demonstrate their value. At = 0.6, AS-CFL surpasses CFL, and this performance gap widens further at α = 0.1, where AS-CFL leads by a significant margin (0.890 vs. 0.880). This analysis highlights the superior robustness of AS-CFL in highly heterogeneous environments, making it a more reliable choice for real-world scenarios where data distributions are highly skewed.

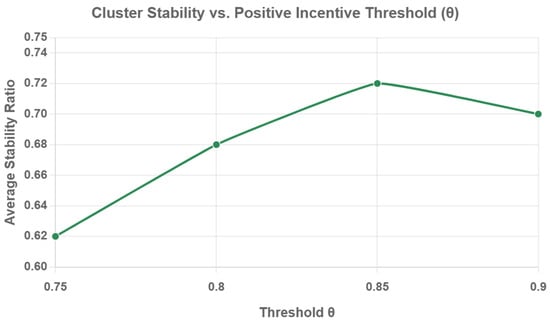

4.4.2. Positive Incentive Threshold

The positive incentive threshold θ is a key hyperparameter that determines whether a client is admitted into a cluster based on its performance contribution. To analyze its impact, we measure cluster stability, defined as the average Jaccard similarity of cluster memberships between consecutive communication rounds, at different values of θ. A higher value indicates more stable cluster formations over time.

As shown in Figure 5, cluster stability is sensitive to the value of θ. A lower threshold (θ = 0.75) results in lower stability (0.62), likely because it is too permissive, allowing clients with dissimilar data to join clusters and causing frequent reassignments in subsequent rounds. As the threshold increases, stability improves, peaking at θ = 0.85 with a stability score of 0.72. This suggests that θ = 0.85 strikes an optimal balance: it is strict enough to filter out detrimental clients but not so restrictive as to prevent beneficial clients from forming cohesive groups. When the threshold is set too high (θ = 0.90), stability slightly decreases again, possibly because the overly strict criterion hinders the formation of optimal clusters. These results indicate that while θ is an influential parameter, the algorithm’s performance is robust within a reasonable range (0.80–0.90), with 0.85 being the optimal choice in our experiments.

Figure 5.

Cluster Stability at Varying Values.

5. Conclusions and Future Work

Federated Learning (FL) has emerged as an attractive approach for training models on distributed networks, adept at handling issues like privacy preservation and collaborative training for heterogeneous clients. However, numerous systemic and technical impediments make the practical application of federated learning difficult in real-world applications. Specifically, the client’s non-IID data distribution often diminishes model accuracy and increases communication overhead in conventional FL. To tackle these challenges, Clustered Federated Learning (CFL) groups clients based on their similar data distributions and varying preferences. However, CFL methods present their own challenges due to the dynamic nature of client preferences and participation, the generation of streaming data, and the need to predetermine the number of clusters, which may not adequately represent the optimal clustering.

This study proposes AS-CFL, an enhanced clustering algorithm in an FL environment, to address these limitations. AS-CFL integrates an adaptive similarity computation mechanism using low-rank matrix factorization to enhance scalability for large client populations. It also employs a novel positive incentive mechanism to assess client contributions, dynamically adjusting poorly or wrongly clustered clients through a well-mechanized cluster stability analysis after every training round. Furthermore, the framework incorporates a dynamic cluster adjustment strategy (including split and merge operations) based on a dispersion-to-separation ratio to ensure the distinctiveness and coherence of clusters without requiring prior knowledge of the optimal number of clusters. The privacy-enhancing noise mechanism is also integrated to provide further data protection [56]. Our experimental results reveal that the AS-CFL algorithm not only achieves robust performance (90% peak accuracy in approximately 40 communication rounds on benchmark datasets) but also demonstrates superior scalability and adaptability compared to state-of-the-art CFL and prior works in adaptive CFL.

We must acknowledge a limitation of the current study regarding the datasets used for validation. Although MNIST and EMNIST are foundational datasets, which allowed us to establish a clear and controlled baseline comparison against foundational CFL works, we recognize that they are relatively simplistic and may not fully represent the complex non-IID challenges found in the real world. Therefore, a critical next step and a primary direction for our future research is to validate the robustness and scalability of AS-CFL on more complex, real-world-style datasets. This includes applying the framework to more challenging color-image datasets (such as CIFAR-10) and to non-image datasets from domains such as healthcare or finance, which present distinct types of data heterogeneity.

Future directions could concentrate on enhancing scalability via more advanced approximation similarity calculations for extensive systems, investigating applications across various fields such as healthcare and IoT, and creating automated systems for dynamic hyperparameter optimization. Furthermore, using sophisticated methodologies such as transformers or reinforcement learning may improve adaptability and robustness, while prioritizing energy-efficient designs would render the framework appropriate for resource-limited settings. These improvements seek to enhance the applicability and efficacy of the AS-CFL framework in practical federated learning contexts.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.Y. and Z.W.; Methodology, G.Y. and Z.W.; Software, Z.W.; validation, Z.W.; writing—original draft preparation, G.Y. and Z.W.; writing—review and editing, X.L. and Z.W.; supervision, G.Y.; project administration, X.Z.; funding acquisition, X.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (No.2023YFC3306204).

Data Availability Statement

The MNIST and EMNIST datasets used in this study are publicly available and can be downloaded from their respective official websites.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AS-CFL | Adaptive Similarity Clustered Federated Learning |

| CFL | Clustered Federated Learning |

| EM | Expectation-Maximization |

| FL | Federated Learning |

| IFCA | Iterative Federated Clustering Algorithm |

| IID | Independent and Identically Distributed |

| Non-IID | Non-Independent and Identically Distributed |

References

- McMahan, B.; Moore, E.; Ramage, D.; Hampson, S.; y Arcas, B.A. Communication-efficient learning of deep networks from decentralized data. In Proceedings of the Artificial Intelligence and Statistics, Fort Lauderdale, FL, USA, 20–22 April 2017; PMLR: Fort Lauderdale, FL, USA, 2017; pp. 1273–1282. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, W.; Chen, X.; Huang, S.; Xiong, G.; Yan, K.; Zhou, X. Federal learning edge network based sentiment analysis combating global COVID-19. Comput. Commun. 2023, 204, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Mi, Y.; Zhang, X.; Li, X. Task graph offloading via deep reinforcement learning in mobile edge computing. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2024, 158, 545–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, F.; Li, S.; Dai, H.; Hu, C.; Dou, W.; Ni, Q. A K-anonymity based schema for location privacy preservation. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Comput. 2019, 4, 156–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, L.; Wang, R.; Hu, C.; Li, S.; He, Q.; Xu, X. Time-aware distributed service recommendation with privacy-preservation. Inf. Sci. 2019, 480, 354–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Ni, Z.; Xu, Y.; Luo, E.; Chen, L.; Zhang, Y. A trustworthy industrial data management scheme based on redactable blockchain. J. Parallel Distrib. Comput. 2021, 152, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Xu, J.; Liu, S.; Jin, Y. Federated learning on non-IID data: A survey. Neurocomputing 2021, 465, 371–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kairouz, P.; McMahan, H.B.; Avent, B.; Bellet, A.; Bennis, M.; Bhagoji, A.N.; Bonawitz, K.; Charles, Z.; Cormode, G.; Cummings, R.; et al. Advances and open problems in federated learning. Found. Trends® Mach. Learn. 2021, 14, 1–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imran, M.; Yin, H.; Chen, T.; Nguyen, Q.V.H.; Zhou, A.; Zheng, K. ReFRS: Resource-efficient federated recommender system for dynamic and diversified user preferences. ACM Trans. Inf. Syst. 2023, 41, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, X. Truthful resource trading for dependent task offloading in heterogeneous edge computing. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2022, 133, 228–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Ji, H. Dual Channel Residual Learning for Denoising Path Tracing. Int. J. Image Graph. 2025, 25, 2550003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sattler, F.; Wiedemann, S.; Müller, K.R.; Samek, W. Robust and communication-efficient federated learning from non-iid data. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2019, 31, 3400–3413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Li, M.; Lai, L.; Suda, N.; Civin, D.; Chandra, V. Federated learning with non-iid data. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1806.00582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, X.-Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, X.; Wu, F.; You, X.; Gao, Y.; Shan, S.; Yang, J.Y. Multiset Feature Learning for Highly Imbalanced Data Classification. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2019, 43, 139–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; He, D.; Zhang, X. Efficient Algorithms for Approximate k-Radius Coverage Query on Large-Scale Road Networks. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2025, 26, 1631–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Wen, J.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, B.; Nie, L.; Zhang, M. Reliable Representation Learning for Incomplete Multi-View Missing Multi-Label Classification. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2025, 47, 4940–4956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Xu, X.; Liang, W.; Zeng, Z.; Yan, Z. Deep-learning-enhanced multitarget detection for end–edge–cloud surveillance in smart IoT. IEEE Internet Things J. 2021, 8, 12588–12596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, K.; Chi, H. Research on Printmaking Image Classification and Creation Based on Convolutional Neural Network. Int. J. Image Graph. 2025, 25, 2550019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallah, A.; Mokhtari, A.; Ozdaglar, A. Personalized federated learning with theoretical guarantees: A model-agnostic meta-learning approach. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2020, 33, 3557–3568. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, M.S.; Javaherian, S.; Xu, F.; Yuan, X.; Chen, L.; Tzeng, N.F. FedClust: Optimizing federated learning on non-IID data through weight-driven client clustering. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Parallel and Distributed Processing Symposium Workshops (IPDPSW), San Francisco, CA, USA, 27–31 May 2024; IEEE: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2024; pp. 1184–1186. [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh, A.; Chung, J.; Yin, D.; Ramchandran, K. An efficient framework for clustered federated learning. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2020, 33, 19586–19597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, G.; Chen, N.; He, J.; Jin, B.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Y. Privacy-preserving clustering federated learning for non-IID data. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2024, 154, 384–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briggs, C.; Fan, Z.; Andras, P. Federated learning with hierarchical clustering of local updates to improve training on non-IID data. In Proceedings of the International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN), Glasgow, UK, 19–24 July 2020; IEEE: Glasgow, UK, 2020; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, Y.J.; Wang, J.; Joshi, G. Client selection in federated learning: Convergence analysis and power-of-choice selection strategies. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2010.01243. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, F.; Zhu, X.; Madhyastha, H.V.; Chowdhury, M. Oort: Efficient federated learning via guided participant selection. In Proceedings of the 15th {USENIX} Symposium on Operating Systems Design and Implementation ({OSDI} 21), Online, 14–16 July 2021; pp. 19–35. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, L.; Zhang, X.; Dou, W.; Hu, C.; Yang, C.; Chen, J. A two-stage locality-sensitive hashing based approach for privacy-preserving mobile service recommendation in cross-platform edge environment. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2018, 88, 636–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Wen, J.; Xu, Y.; Yang, J.; Li, X.; Zhang, D. Enhanced Spatial Feature Learning for Weakly Supervised Object Detection. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2024, 35, 961–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Liang, W.; Kevin, I.; Wang, K.; Yan, Z.; Yang, L.T.; Jin, Q. Decentralized P2P federated learning for privacy-preserving and resilient mobile robotic systems. IEEE Wirel. Commun. 2023, 30, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Sahu, A.K.; Zaheer, M.; Sanjabi, M.; Talwalkar, A.; Smith, V. Federated optimization in heterogeneous networks. Proc. Mach. Learn. Syst. 2020, 2, 429–450. [Google Scholar]

- Karimireddy, S.P.; Kale, S.; Mohri, M.; Reddi, S.; Stich, S.; Suresh, A. Scaffold: Stochastic controlled averaging for federated learning. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, PMLR, Virtual Event, 13–18 July 2020; pp. 5132–5143. [Google Scholar]

- Acar, D.A.E.; Zhao, Y.; Navarro, R.M.; Mattina, M.; Whatmough, P.N.; Saligrama, V. Federated learning based on dynamic regularization. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2111.04263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Tang, H.; Zhao, T.; Chen, X.; Huang, Z. PyCFL: A python library for clustered federated learning. In Proceedings of the 31st International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence (IJCAI), Vienna, Austria, 23–29 July 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, M.; Liu, D.; Ji, X.; Liu, R.; Liang, L.; Chen, X.; Tan, Y. Fedgroup: Efficient federated learning via decomposed similarity-based clustering. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Intl Conf on Parallel & Distributed Processing with Applications, Big Data & Cloud Computing, Sustainable Computing & Communications, Social Computing & Networking (ISPA/BDCloud/SocialCom/SustainCom), New York, NY, USA, 30 September–3 October 2021; IEEE: New York City, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 228–237. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.; Al Hakim, E.; Haraldson, J.; Eriksson, H.; da Silva, J.M.B.; Fischione, C. Dynamic clustering in federated learning. In Proceedings of the ICC 2021-IEEE International Conference on Communications, Montreal, QC, Canada, 14–23 June 2021; IEEE: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2021; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, B.; Xing, T.; Liu, Z.; Wang, J.; Liu, X. Adaptive clustered federated learning for heterogeneous data in edge computing. Mob. Netw. Appl. 2022, 27, 1520–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, B.; Xing, T.; Liu, Z.; Xi, W.; Chen, X. Adaptive client clustering for efficient federated learning over non-iid and imbalanced data. IEEE Trans. Big Data 2022, 10, 1051–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhao, Z.; Hong, W.; Quek, T.Q.; Ding, Z. Clustered federated learning with model integration for non-iid data in wireless networks. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE Globecom Workshops (GC Wkshps), Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 4–8 December 2022; IEEE: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2022; pp. 1634–1639. [Google Scholar]

- Long, G.; Xie, M.; Shen, T.; Zhou, T.; Wang, X.; Jiang, J. Multi-center federated learning: Clients clustering for better personalization. World Wide Web 2023, 26, 481–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Seo, D. FedLC: Optimizing federated learning in non-IID data via label-wise clustering. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 42082–42095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, B.; Li, H.; Liu, Z.; Xing, T.; Hou, R.; Chen, X. FedAC: An Adaptive Clustered Federated Learning Framework for Heterogeneous Data. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2403.16460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, T.; Wang, Z.; Wu, Z.; Shariff, M.H.B.M.; Dick, R.P.; Mao, Z.M. Efficient Distribution Similarity Identification in Clustered Federated Learning via Principal Angles Between Client Data Subspaces. In Proceedings of the Eleventh International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), Kigali, Rwanda, 1–5 May 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, J.; Deng, S.; Fei, L.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, Y. Discriminative Regression With Adaptive Graph Diffusion. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2024, 35, 1797–1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Ren, J.; She, L.; Zhang, Y.; Qin, Z.; Ren, K. EdgeSanitizer: Locally differentially private deep inference at the edge for mobile data analytics. IEEE Internet Things J. 2019, 6, 5140–5151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M.; Saripalli, S.R.; Gupta, A.K.; Palta, P.; Pandey, D. Image Processing-Based Method of Evaluation of Stress from Grain Structures of Through Silicon Via (TSV). Int. J. Image Graph. 2025, 25, 2550008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alistarh, D.; Grubic, D.; Li, J.; Tomioka, R.; Vojnovic, M. QSGD: Communication-efficient SGD via gradient quantization and encoding. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017, 30. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Y.; Han, S.; Mao, H.; Wang, Y.; Dally, W.J. Deep gradient compression: Reducing the communication bandwidth for distributed training. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1712.01887. [Google Scholar]

- He, C.; Annavaram, M.; Avestimehr, S. Group knowledge transfer: Federated learning of large cnns at the edge. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2020, 33, 14068–14080. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X.; Ye, X.; Kevin, I.; Wang, K.; Liang, W.; Nair, N.K.C.; Jin, Q. Hierarchical federated learning with social context clustering-based participant selection for internet of medical things applications. IEEE Trans. Comput. Soc. Syst. 2023, 10, 1742–1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Sanjabi, M.; Beirami, A.; Smith, V. Fair resource allocation in federated learning. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1905.10497. [Google Scholar]

- Goetz, J.; Malik, K.; Bui, D.; Moon, S.; Liu, H.; Kumar, A. Active federated learning. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1909.12641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Liu, C.; Wen, J.; Xu, Y.; Yang, J.; Li, X. Spatial Continuity and Nonequal Importance in Salient Object Detection with Image-Category Supervision. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2025, 36, 8565–8576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A.; Hong, J.; Yin, D.; Ramchandran, K. Robust federated learning in a heterogeneous environment. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1906.06629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Chai, Y.; Sun, C.; Rui, X.; Mi, H.; Zhang, X.; Yu, P.S. A Weighted Symmetric Graph Embedding Approach for Link Prediction in Undirected Graphs. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2024, 54, 1037–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, F.; Dong, L.; Wang, K.; Yang, K.; Pan, C. Distributed resource scheduling for large-scale MEC systems: A multiagent ensemble deep reinforcement learning with imitation acceleration. IEEE Internet Things J. 2021, 9, 6597–6610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eshwarappa, L.; Rajput, G.G. Optimal Classification Model for Text Detection and Recognition in Video Frames. Int. J. Image Graph. 2025, 25, 2550014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Zhou, J.; Lin, Y.; Wei, J. Compressed sensing-based privacy preserving in labeled dynamic social networks. IEEE Syst. J. 2022, 17, 2201–2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).