Abstract

Power conversion efficiency (PCE) of single-junction perovskite solar cells (PSCs) has already soared from 3.8% to more than 26%. Their potential for application in tandem architecture with silicon and other established solar technologies has been deemed the future of low-cost solar technology. However, the commercialization of this technology is critically limited by instability under operational and environmental stress. The instability in the PSCs stems from both internal mechanisms including ion migration, defect formation, and electrode or charge transport layer (CTL)-induced degradation as well as external stressors such as moisture, oxygen, heat, and illumination. A complete understanding of both the internal and external stimuli-induced degradation and their mitigation strategies is essential for improving the device’s longevity. This review aims to provide a complete overview of the degradation mechanisms and steps taken to mitigate the degradation issues. The first half of the review discusses the degradation mechanism caused by internal degradation factors and provides strategies to mitigate them, while the second half focuses on the external stressors and the approaches developed by the perovskite community to overcome them. The commercialization of PSCs will depend on a holistic approach that simultaneously ensures both intrinsically as well as extrinsically stable devices.

1. Introduction

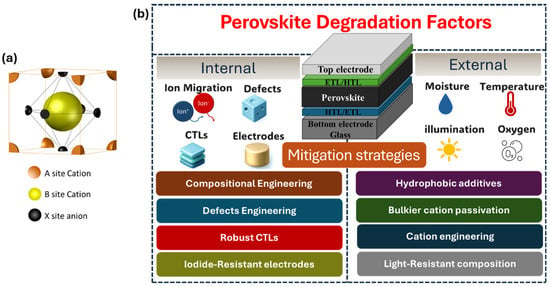

The trend in today’s solar industry is towards producing devices with high reliability, reduced cost, and enhanced performance. Perovskite-based photovoltaic (PV) technology has a promising performance with low cost and low pollution during both manufacturing and disposal, despite the existence of a small amount of lead in the thin perovskite layer [1]. Perovskites have formula ABX3 with a cubic unit cell shown in Figure 1a. The A-site species can be an organic, e.g., methylammonium MA+ or formamidinium FA+ , or an inorganic, e.g., cesium (Cs+) or a mixture of them [2]. Additions of guanidinium (Gu+), and Rubidium (Rb+) have also been reported [3,4]. The B-site has a metal cation, which is usually lead (Pb2+) or tin (Sn2+). The X-site contains a halide anion, which is usually iodide (I−), bromide (Br−), or chloride (Cl−) or a combination of them [5]. The use of perovskites in solar cells was first reported in 2009 with the power conversion efficiency (PCE) of 3.8% [6], which has increased to over 26% to date [7]. However, due to the intrinsic instabilities of the perovskite absorber layer, as well as the external degradants, the stability of the perovskite-based devices limits their adoption in the photovoltaic market.

Figure 1.

(a) Cubic structure of a perovskite unit cell (b) Graphical representation of degradation factors and mitigation strategies of a perovskite solar cell. The abbreviations CTLs, HTL, and ETL refer to charge transport layers, hole transport layer and electron transport layer, respectively.

A reliable solar cell has a high probability of performing its intended function for its design life of 25 to 30 years, under certain operating conditions [8]. Accelerated stress tests are developed to assess the reliability of PV modules; however, specific industrial qualification tests are not well-defined for the perovskite solar cells (PSCs). The stability of the PSC devices is often assessed using thermal cycling tests (200 cycles between −40 °C/85 °C) and damp heat test (1000 h at 85 °C and a relative humidity of 85%) as outlined in the International Electrotechnical Committee (IEC) 61646 guidelines. Additionally, International Summit on Organic PV Stability (ISOS) protocols are also employed to evaluate the durability of the perovskite PV cells [9]. While the inherent instability in the perovskites stems from their brittleness, mechanical fragility with low cohesion energy [10], and the ion-migration driven phase segregation, the heat and light-induced structural deformation further accelerate the internal degradation of the perovskite material [11]. At the same time, external degradants such as moisture, oxygen, light illumination including ultra-violet (UV) radiation, and thermal stress can cause the decomposition of the perovskite, thereby leading to performance deterioration over time [12]. A holistic approach that addresses both the internal and external degradation factors is a requisite for prospering the perovskite technology. Several reviews have previously summarized the stability challenges and mitigation strategies for perovskite stability including degradation mechanisms and remedies [13,14,15]. This review extends and complements these prior works by offering an updated survey of the literature through 2025. Moreover, this work provides a comprehensive discussion of stability testing based on methodologies beyond the standard IEC qualification tests. In addition to IEC 61646, we summarize and compare the ISOS testing series, lifetime evaluations, light soaking, and accelerated stress protocols that have been widely employed in recent research to assess long-term device stability. In the subsequent sections of this article, we shall discuss the internal and external degradation factors responsible for the instability caused in the perovskite solar cells (PSCs) and explore the measures the perovskite community has adopted to overcome the degradation (Figure 1b).

2. Internal Degradation Pathways and Mitigation Strategies

2.1. Ion-Migration-Induced Degradation

Ion migration is the movement of the ionic species within the perovskite bulk, or to the interfaces, or even to other layers within the PSCs. This phenomenon is primarily attributed to the soft lattice structure of the perovskite with weak bonding, which gives rise to the ionic defects within the perovskite, thereby generating the mobile ions [16]. The low activation energies for the halide anions (0.08–0.58 eV) as well as organic cations (0.46–0.84 eV) make them susceptible to migration in ambient conditions which further exacerbates in the presence of external stimuli such as temperature, electric bias, and light illumination [17,18,19]. Additionally, the polycrystalline nature of perovskite films gives rise to the defects and grain boundaries, which behave as dominating channels for the ion migration [20]. Although the ion migration within the perovskite bulk is considered reversible, they can cause a serious irreversible degradation of the PSCs if the ions move to other functional layers [21,22]. Thus, ion migration has been considered one of the prominent causes for decreasing the operational and long-term stability of the PSCs.

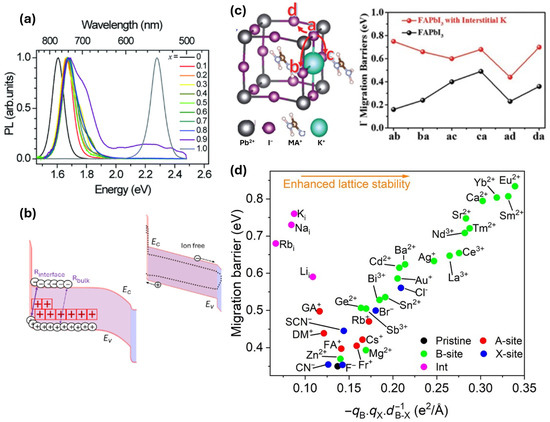

The ion migration leads to charge accumulation at the interfaces, which gives rise to unbalanced charge transport towards the ETL and HTL of a PSC device, thereby causing a mismatch in the forward and reverse current density-voltage (JV) scan of the PSC device called hysteresis [23]. The hysteresis would thus lead to inaccurate performance measurements and indicate the underlying instability in the PSC devices. Another effect of ion migration is the phase segregation observed in the multi-halide perovskites. Hoke et al., while studying MAPbBrxI3−x perovskite, found that Iodine-rich and Iodine-poor perovskite phases were formed within the perovskite film upon light illumination [24]. The photoluminescence (PL) characterization of the light soaked MAPb(BrxI1−x)3 film with 0.2 < x < 1 revealed an additional PL peak at 1.68 eV, which appeared in all the mixed-halide samples, irrespective of the halide composition and bandgap, see Figure 2a. This PL peak which appeared in all the light soaked mixed-halide composition samples corresponded to that of x = 0.2 perovskite phase, disappeared, however, after the samples were left in the dark for some time. They attribute this reversible peak shift to the ion-migration-induced segregation of halides which led to the formation of larger and smaller bandgap perovskites within the film, promoting the formation of trap states, thereby decreasing performance.

The ion migration has also been identified as a major degradation factor for photo-induced losses in the PSCs. A recent finding by Thiesbrummel et al. points out that the increased mobile halide ions during aging screens the built-in electric field, thereby leading to the accumulation of electronic charges (both holes and electrons) near the hole-selective contact (Figure 2b) [25]. This results in the increased recombination at the HTL–perovskite interface, causing significant decrease in the current density and the fill factor of the device. Likewise, the ion migration could give rise to unbalanced stoichiometric polarization in the perovskite absorber layer, enhancing the formation of detrimental anti-sites and metal interstitial defects [26,27]. These defects are prone to changing the photoactive perovskite α phase to photoinactive δ phase, causing the overall perovskite instability [28]. Furthermore, the mobile ions can enter the adjacent charge transport layers, thereby altering their properties and leading to the device instability. It has been observed that the penetration of mobile halide ions to commonly used hole transport layer such as 2,2′,7,7′-tetrakis(N,N-di-p-methoxyphenylamine)-9,9-spiro-bifluorene (spiro-OMeTAD) could prevent its oxidation, thereby reducing its electrical conductivity [21]. Also, the migration of halides from the active perovskite layer to the metal electrodes facilitates the formation of metal halides, causing irreversible degradation of the electrodes [22,29].

Strain has a significant effect on the stability of perovskite films and hence the PSC devices. In perovskite films, studies have shown that compressive strain reduces the bandgap of the perovskite material while increasing carrier mobility and the activation energy for iodide vacancy formation [30]. This helps to suppress ion migration and improve the stability of the device. In contrast, tensile strain has the opposite effect, promoting ion migration and faster degradation. However, excessive compression can cause the perovskite layer to delaminate from the substrate, while tension can lead to cracking. During the high-temperature annealing process, perovskite films often experience strong tensile strain due to the mismatch in thermal expansion coefficients between the perovskite and the glass substrate [31]. This strain, which can reach up to 1.6%, significantly affects the long-term stability of the film.

Mitigation Strategies

Various strategies have been adopted for minimizing the effect of ion migration in the PSCs. The incorporation of alkali cations in the perovskite layer and their interstitial occupancy leads to the suppression of ion migration [32,33]. The interstitial alkali cations can act as physical hinderances for the ions that tend to migrate through the interstitial channels. Furthermore, they could electrostatically bind with the halide anions, which are the most prominent mobile ions in the perovskite crystal, at their crystal lattice sites, thereby strengthening the perovskite crystal structure [34]. Also, the electrostatic binding of these cations with undercoordinated halide ions in the grain boundaries and surfaces neutralize and immobilize the dangling halides. For instance, Cao et al. found that the incorporation of potassium ion (K+) in interstitial sites increased the diffusion barriers for all ionic diffusion paths of the iodide ion by 0.48 eV, thereby mitigating the ionic migrations (Figure 2c) [32]. In addition to the incorporation of cations, the incorporation of anions has also led to increased migration barriers in PSCs. The interstitial occupancy of fluoride (F−) anions has led to more p-type doping in the perovskite material, which increases the formation energy of halide vacancies that ultimately lowers the halide ion migration in the perovskite layer. The incorporation of interstitial F− anion resulted in increased activation energy for iodide ions, thereby increasing the migration barrier by 0.26 eV [35]. As a result of this, unencapsulated CsPbI2Br-based PSCs retained 94% of their initial PCE even after 1000 h of continuous 1-sun illumination. However, a recent finding from Liang et al. pointed out that the B-site doping of the perovskites with multiple cations from alkaline earth and lanthanide groups increases the ion migration barrier by internally stabilizing the octahedra and the perovskite lattice, thereby outperforming the A and X-site substitutions as well as interstitial doping strategies (Figure 2d) [36]. They observed that the interstitial iodide ion diffusivity for pristine perovskites reduced from 6.4 × 10−8 cm2/s to 9.2 × 10−13 cm2/s upon doping the B-site with Eu–Yb–Ca (europium, ytterbium, and calcium) multiple dopants.

Compositional engineering of the A-site cation in perovskites with the introduction of larger dopants to create a steric hinderance for reducing the halide ion migration has been another effective strategy to improve the stability of the PSCs [4,37]. Tan et al. substituted MA cation in the perovskites partially by acetamidinium (CH3C(NH2)2+), which introduced size-mismatch-induced lattice distortions in the crystal, thereby sterically hindering the iodide migration with a higher activation energy of 0.68 eV compared to 0.45 eV for pristine MAPbI3 [38]. This led to an impressive T80 of more than 2000 h under continuous 1-sun illumination at open-circuit condition in ambient environment. Furthermore, the passivation of perovskite surface has proven to be another effective technique for the mitigation of the ion-migration-induced instability in the PSCs. The post treatment of perovskite films with appropriate cationic or anionic species can help passivate the defects and imperfections present at the perovskite/CTL interface which would otherwise act as a path for the ionic migration from perovskite towards the CTL and subsequently towards the electrodes. The use of ammonium salts for surface passivation has been a common strategy which can effectively mitigate surface defect states as well as impede the negative effect of excess lead iodide (PbI2). For instance, dimethylammonium trifluoroacetate (DMATFA) has been applied to the perovskite film surface in which DMA+ and TFA− ions synergistically managed the interfacial lead-based imperfections like Pb0, Vpb, or undercoordinated Pb2+ which resulted in increased activation energy of the iodide ion’s migration from 0.526 eV to 0.604 eV [39]. This led to the enhanced stability of the perovskite solar cell where the DMATFA-passivated device retained 91% of its initial PCE compared to 64% for the control device under maximum power point (MPP) and the cyclic J-V operational stability test. Similarly polymeric interfacial layers between perovskites and CTLs also effectively suppress the ion migration in perovskite solar cells to enhance the stability of the devices. In a recent study, Lin et al. introduced a multifunctional polymeric buffer layer made of magnetic endohedral metallofullerene (Nd@C32) dispersed in a PMMA polymer matrix [40]. This layer enhanced electron extraction and provided encapsulation in inverted PSCs, effectively suppressing ion migration. The electromagnetic-coupled channel ensured balanced carrier extraction between the hole and electron transport layers. As a result, ion interdiffusion is reduced and band alignment is improved, achieving certified efficiencies of 26.29% (0.08 cm2) and 23.08% (16 cm2 module). The unencapsulated devices maintained 82% of their initial efficiency after 2500 h of continuous operation under 1-sun illumination at 65 °C. Likewise, Li et al. evaporated a 2 nm layer of polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) between the perovskite absorber and C60 [41]. This layer encapsulated the perovskite and suppressed ion diffusion across the interface, leading to reduced non-radiative recombination. As a result, the device showed a slight improvement in power conversion efficiency, reaching 25.49%. More importantly, the PTFE-based devices retained 92.6% of their initial efficiency after 1500 h of air exposure. Another effective strategy to inhibit the ion-migration-induced instability in the PSCs is the incorporation of ultrathin inorganic oxide layer in the interfaces between perovskite and CTL and/or the CTL and electrode [42,43]. These oxide layers act as both a physical barrier preventing the mobile ions from migrating into adjacent CTLs or the electrode, and as chemical passivators that neutralize vacancy defects or undercoordinated ions in the perovskite surface, thereby lowering the migration pathways for the mobile ions. For instance, Artuk et al. utilized the thin AlOx interlayer between the perovskite absorber and the electron transport layer (ETL) which greatly improved the operational stability of the device with T80 lifetime improved from 80 h to 530 h [44]. The improvement in the lifetime of the device is attributed to inhibited ionic species (MA+, FA+, I−) removal from the perovskite absorber and the alumina layer slowing down the ingress of external moisture and oxygen. In another work, Chen et al. explored ytterbium oxide (YbOx) as a buffer layer between the ETL and the electrode, which acted as a barrier inhibiting the interdiffusion of harmful species into or outside the perovskite layer [45].

Figure 2.

(a) Normalized photoluminescence spectra of light-soaked MAPb(BrxI1−x)3 perovskite film with different compositions of iodide and bromide anions [24] (CC BY 3.0). (b) Schematic band diagram of HTL/Perovskite/ETL stack showcasing cation vacancy-induced electrons and hole accumulation at the HTL/Perovskite interface (inset: Ion free case); Ec and Ev are energy levels for the conduction and valence bands [25] (CC BY 4.0). (c) Illustration of iodide ion’s diffusion pathways in FAPbI3 perovskite with K+ ion at an interstitial site and comparison plot of iodide ion’s migration barriers with and without interstitial K+ ions [32] (reproduced with permission from John Wiley and Sons, copyright 2018) and (d) Interstitial iodide migration barrier as a function of doping different sites in perovskite crystal. Red, green, blue, magenta, and black dots denote substitutionally doped at A, B, X-site, interstitial doped and pristine perovskite, respectively [36] (Reproduced from Liang et al., Science Advances, 10.1126/sciadv.ads7054, 2025, AAAS.

The reduction in strain has been proven to reduce the ion migration in perovskite solar cells. Thus, strategies for reducing strain have been discussed in subsequent paragraphs. One effective way to reduce residual tensile strain in perovskite films is to lower the processing temperature. Park et al. demonstrated that the crystallization of FAPbI3 can be initiated at room temperature by adding volatile alkylammonium chlorides such as methylammonium chloride (MACl), propylammonium chloride (PACl), and butylammonium chloride (BACl) [46]. These additives promote the formation of intermediate phases that start organizing into a crystalline structure without introducing thermal strain. This early-stage ordering minimizes the need for high-temperature annealing, allowing final crystallization at a lower temperature. As a result, the devices achieved a certified PCE of 26.08% and retained 95% of their initial performance after 1000 h of continuous illumination under MPPT conditions.

Additives in the perovskite precursor can also help relieve thermal strain. For example, trimethylolpropane triacrylate (TMTA) undergoes in situ crosslinking during annealing to form a polymer scaffold at the film surface, where lattice distortion is most severe [47]. This scaffold acts as a mechanical brace, restricting lattice relaxation and anchoring the upper-film region during crystallization. It limits differential shrinkage between the surface and the bulk, converting residual tensile strain into slight compressive strain. Consequently, both phase stability and mechanical integrity are improved. Devices using this approach reached a PCE of 22.39% and maintained 95% of their initial efficiency after 4000 h of storage and 80% after 1248 h of continuous light soaking.

Introducing an intermediate layer is another effective strategy to mitigate thermal mismatch between the perovskite and adjacent layers. Octylammonium iodide (OAI) has been shown to reduce residual tensile stress from 77.7 MPa to 45 MPa [31]. Besides stress relaxation, OAI also passivates surface defects and suppresses non-radiative recombination, contributing to enhanced device performance and stability [48].

2.2. Defects-Induced Degradation

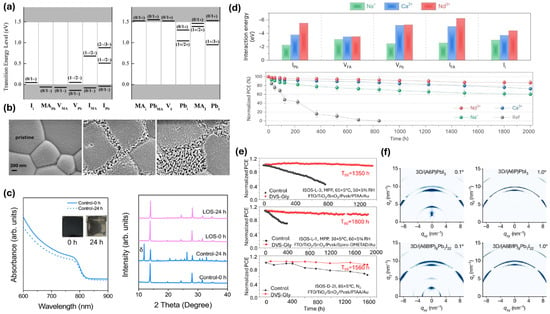

Defect states in the perovskite absorber layer are characterized by theoretical studies using first principal density functional theory. In a commonly used MAPbI3 perovskite structure, three vacancy defects, VMA, VPb, and VI, three interstitial defects, MAi, Pbi, and Ii, and six anti-site defects, MAPb, MAI, PbMA, PbI, IMA, and IPb, constitute a total of 12 intrinsic point defects (Figure 3a) [49]. The defects with low formation energy, which readily form during the crystallization of perovskites, namely VMA, VPb, VI, Ii, MAPb, MAI, and PbMA, form trap states very near to the conduction/valence band, acting as shallow defects [49]. As these defects do not form in the mid-gap states, they do not act as non-radiative recombination centers; instead, they could contribute to the ionic conduction-related issues in the device. Other defects with deep-level trap states such as IMA, IPb, Pbi, and PbI have higher formation energy, thus are less likely to form [49]. Thus, these intrinsic point defects do not act detrimental to the charge carriers generated within the perovskites. However, migration of the shallow charged point defects during the operational condition of a PSC could cause their accumulation at the interfaces inducing unintentional doping, thereby causing local band bending, hysteresis in JV-curves, phase segregation, and consequently degradation of the perovskites [1,50]. Also, apart from these intrinsic point defects, extrinsic defects like grain boundaries present in the polycrystalline perovskite films give rise to the trap states associated with lattice mismatch and disturbances in the regular arrangement of atoms [51]. A polycrystalline MAPbI3 with more grain boundaries has trap densities in the range from 1016 to 1017 cm−3, much higher than that of single crystal MAPbI3 (109–1010 cm−3) [52,53]. Another extrinsic defect that plays a major role in creating the trap states in the perovskite film is the surface. Surfaces give rise to dangling bonds, uncoordinated atoms, dislocations, etc., which act as recombination centers. This can increase the surface trap densities (~6 1017 cm−3) to two orders of magnitude higher than the bulk trap states (~5.8 1015 cm−3) [54].

The defect states in the perovskites can significantly degrade the performance as well as stability of the PSCs. They act as a charge carrier recombination center, thereby impeding the carrier collection. The mobile ionic species in the perovskite can migrate through the defects easily, so the defects trigger the ion-migration-induced degradation in the PSCs [55]. The degradation caused by external stimuli like moisture and oxygen is aggravated in the defective perovskite surface (Figure 3b) [56]. Tian et al. theoretically investigated the diffusion of water molecules in MAPbI3 perovskite using density functional theory (DFT) and found that water diffusion through grain boundaries and defects is easier compared to bulk perovskite [57]. The loose atomic packing fraction and large free volume at grain boundaries support the diffusion of water molecules, initially forming a loose covalent interaction between the undercoordinated Pb atom in perovskite surface and O atom in water. The weak and easily breakable Pb–O covalent bond offers little resistance to the inward diffusion of water molecule into the crystal forming H···O hydrogen bonds with the organic cation, eventually leading to crystal degradation. In contrast, the formation of Pb–O covalent bond by the dissociation of the Pb–I inorganic framework in the bulk perovskite is limited by very high energy barriers, thereby resisting moisture infiltration under similar conditions. The diffusion energy barrier for water molecules was as low as 0.07 eV for grain boundaries, 0.24 eV for diffusion from grain boundaries to the bulk, and 0.7 eV for diffusion in the pristine bulk. This lower barrier signifies that the grain boundaries are detrimental for water ingress and degradation of the PSCs. Likewise, the defects can act as the site for O2 adsorption [58] which can form a superoxide (O2−) on capturing a photoexcited electron during illumination. The perovskite films composed of smaller crystallites show a higher yield of superoxide which verifies the role of grain boundaries with defects towards the superoxide formation. Furthermore, theoretical calculations also reveal that the most favorable site for superoxide formation is the iodide vacancy site. For instance, the calculated formation energies of superoxide at different sites in the perovskite crystal are as follows: : −1.94 eV; the surface site, where the superoxide interacts with four neighboring iodide ions: −1.19 eV; : +0.29 eV; and : −0.23 eV [59]. These results further corroborate the role of grain boundaries and surfaces in oxygen-induced deterioration of perovskite films. The superoxide can react with the organic component of the perovskite absorber, thereby initiating the irreversible degradation of the absorber [60]. The defect states can also cause the transition of perovskites from photoactive alpha phase to inactive delta phase (Figure 3c) [61]. The iodine vacancy defects, which are easily generated during film deposition and device operation, cause the reduction in energy barrier for the phase transition, thereby triggering the alpha to delta phase transition.

Mitigation Strategies

Multiple approaches for lowering the extrinsic defects and immobilizing the internal unavoidable intrinsic point defects have been implemented to mitigate the defect-induced instabilities in the PSCs. The use of excess precursor material has been adopted for the reduction in the defect density as well as for the passivation of the grain boundaries. Park et al. studied the effect of excess lead iodide in the perovskite precursor and unraveled the mechanism of improved performance and stability [62]. They concluded that the excess PbI2 containing perovskite is less susceptible to defect formation during cleaving or lab air exposure. The excess PbI2 maintains higher I− ion activity during the crystallization of halide perovskites and thus shifts the reaction equilibrium towards the formation of halide perovskite with fewer iodide vacancies, which helps to lower the iodide vacancies’ formation during crystallization. They further found that excess PbI2 surrounds the perovskite grains rather than being confined to specific locations at the grain boundaries, which facilitates better charge transfer, reduces hysteresis, and leads to a more stable device. However, the photolysis of excess lead iodide could also give rise to metallic lead and iodine as decomposition products, which could possibly induce the degradation of the PSCs [63,64]. Thus, the use of excess lead iodide should be carefully optimized to balance its passivation benefits over the potential stability issues. Similar to excess lead iodide, an excess of organic precursor powder has also led to improvement in the performance and stability of the perovskite device. For instance, Son et al., using a high-resolution transmission electron microscope (HRTEM), showed that excess methylammonium iodide (excess 6 molar %) added in the precursor resided around the grain boundary suppressing the non-radiative recombination and facilitating the electron and hole extraction from the grain boundaries [65].

Another successful strategy for reducing the defect-induced instability in the PSCs is the cationic or anionic doping of the perovskite precursor. Alkali metal ion doping to the perovskite has resulted in significant improvement in grain size, thereby reducing the trap states [66]. Moreover, the Na+ and K+-ion doping led to a reduced trap-filled voltage to 0.28 V and 0.3 V, respectively, which is significantly lower than 0.48 V of undoped perovskite, thereby confirming the reduction in the trap states in the device. Furthermore, Zhao et al. explored the doping of trace amounts of multivalent cations such as Nd3+ and Ca2+ instead of high-dosage monovalent cations [67]. The interaction energies between the defects and Nd3+ were the highest, followed by those for Ca2+ and Na+ (Figure 3d). Trace amount of Nd3+ dopant (0.08 molar %) caused less strain in the perovskite crystal compared to high-dosage Na+ dopant (0.45 molar %), while increasing the energy barrier for VI migration to 2.8 eV (Ca+: 0.81 eV and Na+: 0.43 eV) from 0.37 eV for undoped perovskite film. The thermal stability of the devices greatly improved such that the unencapsulated devices in nitrogen environment at 85 °C maintained 86.4%, 72.7%, and 60.3% for Nd3+, Ca2+, and Na+ respectively after 2002 h (Figure 3d). Likewise, tetrafluoroborate (B) pseudohalide anion doped to Sn-Pb perovskite exhibited higher binding capacity with Sn2+/Pb2+ cations, which resulted in the lowered VI formation. This improved the light soaking stability of the devices; PSCs doped with the B anion maintained 88% of initial PCE until 1000 h of light illumination at maximum power point tracking (MPPT) measurement condition [68]. In another study, Liu et al. doped the perovskite with P anion, which controlled the crystallization via the formation of fully coordinated intermediate groups in the solution, ultimately decreasing the halide vacancies [69]. This strategy led to long-term stable devices with T80 at 4000 h under ambient storage (40–50% RH) and T80 at 1000 h under continuous illumination.

The Lewis acids and bases have the capability to accept and donate electron pairs to the uncoordinated charged species in the perovskite bulk or surface, making them suitable to mitigate the defects inside the perovskites. Different studies on the application of these materials for the enhancement of performance as well as stability of the PSC devices have been carried out. For instance, Ding et al. utilized Lewis base ionic liquid such as 1,3-bis(cyanomethyl)imidazolium chloride combined with methylammonium chloride as additive to the perovskite precursor and found that the nitrile group could passivate the uncoordinated Pb2+ sites and the chloride ion could occupy the halide vacancy sites [70]. By the use of 1H NMR spectroscopy, they further found that the additives slowed the decomposition of the organic MA+/FA+ cations. The PSCs retained 94.7% of their initial PCE after 1000 h of continuous 1-sun illumination, and maintained 84.5% of their initial PCE when subjected to continuous 1-sun illumination at 65 °C, demonstrating excellent stability metrics. Another study by Liang et al. made use of a low Lewis basic solvent divinyl sulfone (DVS) and treated the perovskite film with glycerinum to trigger the co-polymerization at the perovskite surface and grain boundary [71]. This strategy retarded the crystal growth rate from 0.073 S−1 to 0.061 S−1, thereby reducing the formation of defect states during the crystallization. Grazing incidence XRD performed at 50 nm near the surface and 200 nm in the bulk part of the film revealed that the tensile stress, which was present in the near surface region of the control sample, had diminished for the co-polymerized samples. This resulted in the excellent operational stability at elevated temperature (MPP, 65 °C, 50% RH, T98 at 1350 h) and room temperature (MPP, 60%RH, T90 at 1800 h) as well as thermal stability in the dark (85 °C, N2, T95 at 1560 h) (Figure 3e).

Recent efforts to reduce deep-level defects in perovskite films have focused on bulk passivation using tailored molecular agents. Liu et al. developed sulfonium-based passivators that can penetrate the perovskite lattice and directly interact with bulk defects, suppressing non-radiative recombination and improving charge transport [72]. These passivators increased power conversion efficiency from about 23.5% to 24.8%, with clear improvements in open-circuit voltage and fill factor. The treated devices also maintained over 90% of their initial efficiency after 1000 h of continuous illumination and thermal stress.

Apart from the bulk defects, interfacial defects also play a crucial role for the device longevity. The passivation of interfacial defects has been an important strategy not only to reduce the interfacial non-radiative recombination centers, but also to facilitate the charge transfer from the perovskite layer to the charge transport layers. The use of two-dimensional (2D) perovskite forming materials for the passivation of the perovskite surface has been a successful strategy to overcome the interface-related issues. For instance, Zhang et al. utilized guanidine halides (GuCl and GuI) for the passivation of bulk and surface defects of the perovskites [73]. From first principle theoretical calculation, they identified GuCl as suitable candidate for the bulk passivation, which could slow the crystal growth kinetics, giving rise to bigger grains and less defect state density, while GuI having a bulkier iodide group was deemed beneficial for the surface. It led to the formation of 2D Gu2PbI4, which passivated the interface for efficient hole transport, thereby enhancing the performance and stability of the device. In another study, Wang et al. designed a bilayer interface engineering strategy, implying phenyl ethyl ammonium iodide (PEAI) to form a 2D/3D heterojunction at the perovskite surface for interfacial defect passivation and a piperazinium iodide (PI) layer on top of the 2D/3D interface to induce surface dipoles for fine tuning the energy level alignment between the perovskite and the ETL [74]. This strategy led to increased n-type characteristic of the perovskite film, thereby facilitating the electron extraction, which led to better performance and the stability of the device. Furthermore, the presence of bulkier hydrophobic organic spacer cations along with stronger binding between the layers in 2D perovskites impart onto them better moisture as well as thermal stability. Application of these robust 2D perovskite layers atop the fragile 3D perovskite layer protects the 3D counterparts from the moisture ingress and maintains the structural integrity of the 3D perovskite device under elevated temperature [75,76]. Also, the application of a 2D perovskite layer on the 3D perovskites help minimize the ion migration issue, which has been a key challenge in the 3D perovskite’s stability. These properties of 2D perovskites thus impart long-term stability and higher performance in the 3D perovskite-based solar cells. Liu’s group, however, pointed out that the cations could migrate between 3D and 2D perovskite layers, resulting in octahedra distortion, and hence chose 2D perovskitoids instead of 2D perovskites for the surface passivation of their perovskite films [77]. The 2D perovskitoids help protect the 3D perovskite layer by reducing the cation diffusion within the heterostructure, thanks to extra π–π interactions between the flat, and well-aligned spacer molecules in the 2D perovskitoids layer. The 2D perovskitoids such as (A6BfP)8Pb7I22 (A6Bfp: n-aminohexyl-benz[f]-pthalamide) (Figure 3f) benefit from having higher stability compared to 2D perovskites such as (PEA)2PbI4 and provide the better defect passivating capacity. The thermal stability of the devices with 2D perovskitoids was greatly enhanced, which retained 85% of their initial PCE after 1250 h of continuous operation under 1-sun at 85 °C while the 2D perovskite devices had only 52% PCE retention.

Figure 3.

(a) Transition energy levels of intrinsic point defects in MAPbI3 perovskite [49] (reproduced with permission from AIP publishing, copyright 2014). (b) SEM image of Lead acetate (PbAc2) films showing oxygen-induced degradation initiating from the grain boundaries [56] (reproduced with permission from John Wiley and Sons, copyright 2017). (c) UV-Vis spectra of FAPbI3 perovskite film indicating transformation from alpha to delta phase (Inset: visual pictures of the tested film) and XRD spectra of the perovskite films depicting the transformation from alpha to delta phase [61] (CC bY 4.0). (d) Interaction energies of Nd3+, Ca2+ and Na+ cations incorporated in perovskite lattice with different negatively charged defects and thermal stability of those cations doped unencapsulated PSC [67] (reproduced with permission from Nature Springer, copyright 2022). (e) Stability enhancement in the divinyl sulfone (DVS) and glycerinum-treated PSCs tested under different conditions [71] (reproduced with permission from Nature Springer, copyright 2025) and (f) GIWAXS patterns of the 1D (A6P)PbI3/3D perovskite (top) and 2D (A6BfP)8Pb7I22/3D perovskite (bottom) heterostructure films at incident angles of 0.1° (left) and 1.0° (right) [77] (reproduced with permission from Nature Springer, copyright 2024).

2.3. Charge-Transport-Layer-Induced Degradation

Charge transfer layers (CTL) are necessary for the efficient separation of the photogenerated carriers from the perovskite absorber layer. A Perovskite absorber layer is often embedded between n-type and p-type semiconducting materials, which are termed as electron transport layer (ETL) and hole transport layer (HTL), respectively. Depending on which CTL is deposited first on the transparent conducting electrode, the perovskite solar cells are classified into regular (n-i-p) structure and inverted (p-i-n) structure. Different electron, hole transfer layers, and processing conditions are applicable for those different architectures. Different organic materials like spiro OMeTAD, poly[bis(4-phenyl)(2,4,6-trimethylphenyl)amine] (PTAA), poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene)polystyrene sulfonate (Pedot:PSS), poly(3-hexylthiophene) (P3HT), self-assembled monolayer (SAM) molecules like [2-(3,6-dimethoxy-9H-carbazol-9-yl)ethyl]phosphonic acid (MeO-2PACZ), [2-(3,6-dimethoxy-9H-carbazol-9-yl)butyl]phosphonic acid (MeO-4PACZ), etc., and inorganic materials like nickel oxide (NiOx), copper oxide (Cu2O), copper thiocyanate (CuSCN), molybdenum disulfide (MoS2), etc., have been used as HTL by the perovskite community [78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85]. Likewise, ETLs used in perovskite solar cells can also be divided into organic and inorganic categories. Carbon-based ETLs like fullerene (C-60), [6,6]-phenyl-C61-butyric acid methyl ester (PCBM), indene-C60 bisadduct (ICBA), pyrelene diimides (PDI), napthelene diimides (NDI), etc., are the common organic ETLs while titanium dioxide (TiO2), tin oxide (SnO2), zinc oxide (ZnO), ferric oxide (Fe2O3), tungsten trioxide (WO3), cerium (IV) oxide (CeO2), etc., are the common inorganic ETLs [86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96]. In this section, instability caused by the most commonly used CTLs and their mitigation strategies shall be discussed.

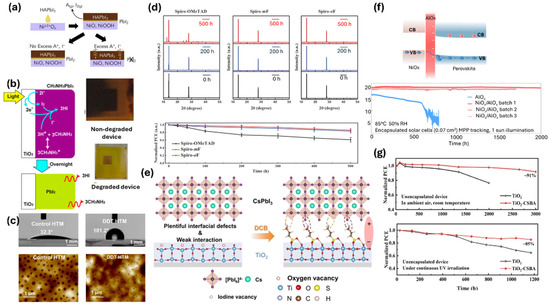

The most commonly used HTL in the high-performance n-i-p PSCs, spiro-OMeTAD, is intrinsically less conductive with lower hole mobility. It is doped with lithium bis(trifluoromethane)sulfonimide (LiTFSI) and 4-tert-butylpyridine (t-BP) for improving its conductivity [97]. Oxidation of the LiTFSI is essential to achieve improved conductivity; however, its hygroscopic nature allows it to absorb moisture during this process, leading to degradation of the underlying perovskite layer [98]. Additionally, the diffusion of Li+ ion from the HTL to the perovskite absorber layer has been observed, which lowers the hole conductivity of spiro-OMeTAD as well as induces instability in the absorber layer [99]. Furthermore, time of flight secondary ion mass spectroscopy (TOF SIMS) analysis has revealed the migration of t-BP or its fragments towards the absorber layer, which can induce perovskite degradation forming a PbI2–t-BP complex [100]. Another common HTL, PTAA, is also p-doped using LiTFSI and t-BP, similar to spiro-OMeTAD; thus, a similar instability mechanism as induced by spiro, can also occur in PTAA devices [101]. Similarly, PEDOT: PSS, another common HTL, introduces instability due to its acidity and high hygroscopicity, both of which can deteriorate device performance over time [102,103]. The most common inorganic HTL used in p-i-n PSC devices, NiOx, could induce degradation in the perovskite layer owing to the presence of undercoordinated metal cation sites (Ni3+) on its surface (Figure 4a) [104]. This cation can induce the formation of A-site-deficient PbI2 only layer at the interface between HTL and the absorber, which not only limits the performance but also the stability of the device over time. Likewise, Cheng et al. observed that the sol-gel-processed NiOx surface exhibited dipole character, which induced the adhesion of precursor ions on the NiOx surface during the film formation, thereby creating vacancy defect states in the interface which proved detrimental to the device stability [105].

Similarly to HTLs, ETLs, which are used for efficient electron extraction from the perovskite layer, could also induce instability in the PSC devices. A commonly utilized ETL for n-i-p regular structure perovskite solar cells, TiO2, is susceptible to inducing degradation in the perovskite layer due to its photocatalytic action in the presence of UV light (Figure 4b) [5]. Holes generated due to UV irradiation can extract electrons from organic materials as well as iodides, thereby causing the perovskite crystal decomposition [106]. Similarly, in a widely used inorganic ETL such as SnO2, increasing the concentration of oxygen vacancies is beneficial for enhancing electron mobility [107,108]. However, this also results in a higher positive charge on the Sn atoms, which can lead to an increased Pb–I bond length at the SnO2/perovskite interface, which can induce iodide interstitials, potentially accelerating device degradation [109]. Furthermore, high oxygen vacancies could deprotonate the organic cations, followed by their hydrolysis to form amides, which cause the decomposition of perovskites. Likewise, most common ETLs such as PCBM for p-i-n type solar cells strongly facilitate the photo-induced decomposition of perovskite films by absorbing the organic components (methylammonium halide) of the perovskite degradation products [110]. The cavity between the carbon spheres can easily accommodate those degradation products. Such intercalation of these products and their diffusion towards metal electrodes deteriorate the device stability.

Mitigation Strategies

The mitigation strategies employed to reduce CTL-induced degradation in PSCs are tailored to the specific degradation pathways caused by the CTLs. For example, in spiro-OMeTAD-based PSCs, degradation typically begins due to its prolonged oxidation time [69]. To address this, various oxidation-accelerating materials, such as vanadium oxide (V2O5) and alkylthiol additives (e.g., 1-dodecanethiol, DDT), have been introduced, which help to rapidly oxidize spiro-OMeTAD, thereby preventing degradation [111,112]. In addition to reducing oxidation time, the coordination between DDT and LiTFSI in the spiro-OMeTAD layer helps minimize the formation of pinholes and enhances the hydrophobicity of the layer (Figure 4c). This results in significantly improved device stability [84]. Likewise, the doping of spiro-OMeTAD to enhance the hydrophobicity of the layer has been used as another strategy to minimize the degradation [113,114]. For instance, the use of fluorinated spiro-OMeTAD as HTLs created kinetic barriers slowing the intrusion of O2 and moisture in the perovskite layer, maintaining its integrity (Figure 4d: XRD of perovskite films deposited on control and fluorinated spiro) [114]. This resulted in much-enhanced stability of the PSC devices. Another strategy is the use of dopant-free spiro-derived HTLs, which could oxidize without air assistance, thereby enhancing the stability of the devices [115,116,117]. The surface-induced degradation in another common inorganic HTL, NiOx, has been mitigated using various strategies. Boyd et al. utilized an excess A-site cation salt in the perovskite precursor to inhibit the formation of PbX2 hole extraction barrier at the perovskite–NiOx interface, which in turn enhanced both the performance as well as stability of the inverted PSCs [104]. Likewise, Mahmoudi et al. developed an innovative way of ensuring long-term stability and efficiency of perovskite devices by introducing p-type NiOx and highly conductive graphene into perovskite layer and inserting another NiOx interface layer between perovskite and the electron transporting layer. The strong chemical interaction and bonding between perovskite, NiOx, and graphene effectively reduces the side reaction between perovskite and oxygen and moisture, which resulted in the much-enhanced long-term stability, retaining 97–100% of the initial performance after 310 days under ambient condition (25–30 °C, RH = 45–55%) [118]. Passivation of the NiOx surface by oxide layers has also been implemented to enhance the device stability. One recent finding highlights the use of an ultrathin, ALD (atomic layer deposition)-coated alumina layer sandwiched between NiOx and perovskite which resulted in negative fixed charge passivation of the interface, which led to ultra-stable PSCs [119]. The passivated devices under 1-sun illumination at MPPT exhibited no loss in performance until 2000 h of measurement (Figure 4f). The use of SAM as HTL in inverted PSCs has led to enhanced performance; however, their instabilities often compromise the long-term stability of the devices. In a recent study, Jiang et al. introduced 3-azidopropyl phosphonic acid into 4-(7H-dibenzo[c,g]carbazol-7-yl)butyl phosphonic acid (CbzNaph) SAM to form a cross-linkable co-SAM, which improved the toughness and conformational stability of hole-selective interfaces [120]. This enhances interfacial adhesion and mechanical resilience. In addition, they used EDAI2 to reduce ion migration and non-radiative recombination. Together, these strategies enabled a power conversion efficiency of 26.17%. Stability tests following the ISOS-L2 protocol showed negligible PCE loss after 1000 h of MPPT and 98% retention after 700 thermal cycles.

The photocatalytic degradation in PSCs induced by TiO2-based ETLs in high-performing devices has been minimized using different approaches, like using UV absorption or downshifting layers [121,122,123], using different inorganic and organic materials as an interfacial layer between the ETL and perovskites [124,125,126,127], using alternative non-UV-sensitive ETL materials [128,129], etc. Qiu et al. utilized 4-aminobutyric acid (CA) and 3-amino-1propanesulfonic acid (SA) to construct an interfacial dipole between the titania and perovskite surface (Figure 4e), which helped in the reduction of interfacial defects, thereby enhancing UV stability of the CsPbI3 device [127]. Likewise, Wang et al. used 4-chloro-3-sulfamoylbenzoic acid (CSBA), which connected the TiO2 top surface and perovskite bottom surface, forming a molecular bridge at the TiO2/Perovskite interface which greatly reduced the interfacial degradation, thereby improving the ambient as well as UV stability of the devices (Figure 4g) [126]. Koo et al. utilized mesoporous MoS2 as an ETL alternative to TiO2 and obtained an impressive performance (>25% PCE) as well as photostability (1-sun illumination/2000 h/T90) of their PSCs [128]. Also, the use of surface-modified SnO2 as the ETL in PSC devices resulted in enhanced environmental stability compared to the TiO2–ETL devices [129,130].

Figure 4.

(a) Schematics of formation of lead halide (PbX2) hole extraction barrier at the NiOx/perovskite interface and strategic addition of excess A-site precursor to overcome the issue (PbI2 is the lead iodide layer between NiOx and perovskite) [104] (Reproduced with permission from Elsevier, Copyright 2020). (b) Schematics of TiO2-induced photo degradation of perovskite absorber layer [5] (Reproduced with permission from American Chemical Society, Copyright 2014). (c) Contact angle measurement on the spiro-ometad and 1-dodecanethiol (DDT)-doped spiro-ometad surfaces and corresponding atomic force microscopy measurement images. (d) Time evolution of XRD patterns of perovskite film with control and fluorinated spiro-ometad and the stability of corresponding PSCs [114] (Reproduced from Jeong et al., Science, 10.1126/science.abb7167 [2020], AAAS). (e) Schematic of interfacial dipole formation by using 4-aminobutyric acid and 3-amino-1-propanesulfonic acid molecules between TiO2 and perovskite layer [127] (Reproduced with permission from John Wiley and Sons, Copyright 2024). (f) Schematics of electronic structure and carrier distribution in conduction and valence band (CB, VB) of perovskite/NiOx interface passivated by ultrathin aluminum oxide (AlOx) and the corresponding device performances showing long-term operational stability [119] (Reproduced with permission from Springer Nature, Copyright 2023) and (g) enhanced UV and ambient stability of perovskite solar cells with titanium dioxide (TiO2) electron transport layer passivated by 4-chloro-3-sulfamoylbenzoic acid (CSBA) molecule [126] (Reproduced with permission from John Wiley and Sons, Copyright 2024).

2.4. Electrode-Material-Induced Degradation

Perovskite solar cells are typically fabricated starting with fluorine-doped tin oxide (FTO) or indium-doped tin oxide (ITO)-coated glass as the bottom electrode, onto which the active material is deposited between appropriate charge transport layers (CTLs) and finished with top electrode deposition [131]. The top electrode, which is near the atmosphere, must be robust enough to maintain its own stability while also protecting the underlying layers [132]. Generally, noble metals like silver (Ag) and gold (Au) are employed as top electrodes in PSCs, owing to their resistance to oxidation and corrosion. However, instabilities in the PSC devices related to the use of those electrodes have been observed, which shall be discussed in this section. Also, we shall provide the schemes adopted to overcome those instability issues.

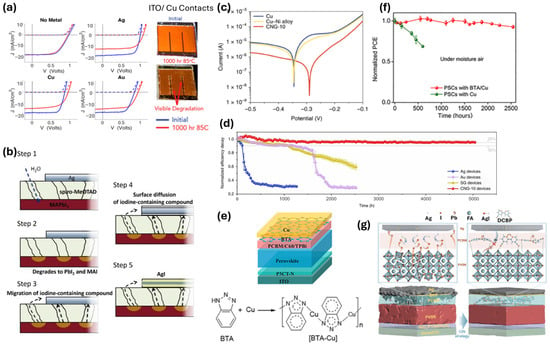

The migration of the top contact electrode to the active perovskite layer as well as the CTLs has been found to degrade the stability of PSCs. The degradation of perovskite material by the penetration of Au from top contact to the perovskite layer through spiro-OMeTAD has been reported by Domanski et al. [133]. The elemental depth profile using TOF-SIMS and inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICPMS) of the perovskite active layer revealed the presence of large amount of Au in 70 °C/15 h/1-sun MPPT-aged samples. The presence of Au in the active layer resulted in shunting of the device and introduced deep-level trap states in the perovskite active layer, leading to instability in the device. Although Au is deemed more stable against chemical degradation compared to other electrodes like Ag and Al, studies have pointed out that highly reactive polyiodide melts (MAI-nI2), that are released upon UV exposure from the iodide containing perovskite films, could chemically interact with Au, thereby forming a (MA)2Au2I6 phase at the Au/HTL interface, inducing intrinsic instability in the device [134]. Another study by Boyd et al. made use of different metal electrodes (Ag, Au and Cu) in their PSC devices and found thermal-induced degradation for all of them when the devices were heated at 85 °C (Figure 5a) [135]. They speculated that the metals diffused to the perovskite layer, thereby reacting with it to degrade the performance of the PSC over time. They further pointed out that the metal electrodes could also act as a sink for iodide migration from the perovskite, inducing the degradation of the PSC devices. Likewise, Kato et al. suggested that the pinholes in the spiro-OMeTAD layer make the perovskite vulnerable to moisture ingress, leading to the release of volatile iodine-containing species such as MAI and HI [136]. These species can then diffuse toward the top Ag layer, where they react to form a nonconductive AgI layer at the HTL/Ag interface (Figure 5b). Interestingly, the degradation of the perovskite active layer can also be initiated at the grain boundaries, driven by the thermodynamic tendency to form AgI within the Ag electrode, even in the absence of moisture. This process results in the release of mobile MA+ and I− ions, which can diffuse through the CTL and accumulate at the inner surface of the electrode, ultimately forming a highly detrimental AgI layer [137].

Copper can be a promising electrode material for the PSCs because of its excellent conductivity and low cost; however, the stability of the copper-based PSCs is also not satisfying. They can readily oxidize in air, forming CuO or Cu2O which reduces the conductivity and work function alignment with underlying layers. Also, the reactivity of copper with the perovskite constituents like the organic cations or the halide anions could result in degradation of both the perovskite and the copper electrode itself. Such reactions could be initiated by the diffusion of copper ions into the perovskite or through the diffusion of ions from perovskite to the copper electrode [138]. Such degradation of PSCs due to electrode degradation caused by the origination of mobile ions in the perovskite layer has also been studied for low-work-function metal electrodes like aluminum [139]. A comparison of different electrodes (Ag, Al, Au and Ni) for PSC revealed the most rapid degradation of Al-based PSC, exhibiting both the perovskite decomposition as well as the electrode’s corrosion.

Mitigation Strategies

Different approaches have been adopted to minimize the degradation of electrode materials to enhance the PSC longevity. One of them is the use of a physical barrier in between the HTL and the electrode layer. For instance, Domanski et al. utilized a chromium metal interlayer between the HTL and the gold electrode. The deposited chromium layer acted as a diffusion barrier between the gold electrode and the heat-stressed, crack-prone spiro-OMeTAD, effectively preventing gold migration across the HTL to the perovskite, thereby improving the device’s long-term operational stability [133]. Likewise, the use of semi-metal bismuth (Bi) as an interlayer between the HTL–electrode interface resulted in the inhibition of iodide-induced corrosion of the electrode as well as the penetration of electrode materials to the perovskite bulk via the CTL [140]. This strategy significantly improved the long-term storage stability of the target devices. The unencapsulated devices, with the Bi interlayer, retained 88% of their initial PCE after 6000 h, compared to only 33% PCE for the device without the Bi interlayer after just 1000 h under similar storage conditions (ambient air/dark). The chemical inertness and low penetration of compact bismuth on the perovskite layer during thermal aging not only inhibited the ion migration but also prevented the permeation of oxygen and water towards the perovskite film, thereby enhancing the stability of the PSC device. Another study by Lin et al. utilized chemical-vapor-deposited graphene as a bilayer on both sides of their copper–nickel alloy electrode [141]. The outer-layered graphene blocked the external degradants such as moisture and oxygen, while the inner graphene layer suppressed the ion migration and metal diffusion from and towards the perovskite layer. The graphene-composited electrode displayed a higher self-corrosion potential (Figure 5c), representing higher resistance to electrode corrosion. This resulted in the retention of more than 95% of initial PCE after 5000 h of continuous 1-sun illumination at MPPT (Figure 5d) [141].

Another successful approach for the mitigation of electrode corrosion and electrode-induced degradation in the perovskite active layer is using materials, which form a chemical anti-corrosion layer with the electrode material. This anti-corrosion layer inhibits the migration of perovskite ions as well as electrode atoms through them. Different materials such as benzotriazole, 2-mercaptobenzothiazole, 2,2′-(1,3-phenylene)-bis [5-(4-tert-butylphenyl)-1,3,4-oxadiazole], etc., have been found to bind with electrodes to form the corrosion-resistant layer, which greatly enhances the stability of the PSCs [142,143,144]. For instance, The benzotriazole (BTA) chemically coordinates with the Cu electrode and forms an insoluble and polymeric BTA–Cu film, suppressing corrosion of the Cu electrode and the reaction between the perovskite and the electrode (Figure 5e), which resulted in enhanced moisture stability of the device (Figure 5f) [142]. The incorporation of thiazole and thiol-based compounds to modify the bathocuproine (BCP) layer in p-i-n-type PSCs has also been reported, which facilitates chemical coordination between the additives and electrode atoms, leading to the formation of an anti-corrosion layer on the electrode’s bottom surface, significantly enhancing the stability of the PSC devices [145,146]. Likewise, Gong et al. incorporated a bipyridine derivative, 4,4′-dicyano-2,2′-bipyridine (DCBP) into PCBM in their p-i-n PSCs, enabling nitrogen coordination with the Ag electrode and facilitating charge transfer between surface iodide ions on the perovskite and the cyano groups in DCBP [147]. This dual interaction effectively blocked Ag diffusion and prevented iodide intrusion into the electrode (Figure 5g), which led to very stable devices (95% PCE retention, 2500 h, 1-sun MPPT and >90% PCE retention, 1500 h, 85 °C/85% RH).

Figure 5.

(a) Performance degradation of the thermally treated (85 °C) FA0.83Cs0.17Pb(I0.83Br0.17)3 perovskite solar cells with different top electrodes (no metal, silver, copper, and gold), blue curves and red curves correspond before and after thermal treatment, dashed and solid curves represent the dark and light JV curves respectively, and the inset picture shows visual degradation of Cu-based solar cells where degradation originates along the metal fingers [135] (Reproduced with permission from American Chemical Society, Copyright 2018). (b) Schematics representing the formation of silver iodide (AgI), thereby hindering the long-term stability of the perovskite-based solar cell device [136] (Reproduced with permission from John Wiley and Sons, Copyright 2015). (c) Tafel curves of the copper (Cu), copper–nickel (Cu–Ni alloy) and copper–nickel–graphene (CNG)-based electrodes showing enhanced electrochemical corrosion stability upon graphene coating [141] (Reproduced with permission from Springer Nature, Copyright 2022). (d) Operational stability of the encapsulated perovskite PV devices with silver (Ag), gold (Au), sprayed graphene (SG) and copper–nickel–graphene (CNG)-based electrodes [141] (Reproduced with permission from Springer Nature, Copyright 2022). (e) Device structure of perovskite solar cells implementing copper (Cu) as top electrode and benzotriazole (BTA) interlayer beneath it and chemical reaction depicting the formation of polymeric BTA–Cu film (Reproduced from [Xiaodong Li] et al., Science, 10.1126/sciadv.abd1580 [2020], AAAS). (f) Enhanced moisture stability of the solar cell device with polymeric BTA–Cu film [142] (Reproduced from [Xiaodong Li] et al., Science, 10.1126/sciadv.abd1580 [2020], AAAS) and (g) schematics illustrating the nitrogen coordination between the top silver (Ag) electrode atoms and 4,4′-dicyano-2,2′-bipyridine (DCBP) dopants in PCBM, which facilitates the stability of the perovskite solar cells [147] (CC BY 4.0).

The incorporation of carbon as an electrode material has significantly enhanced the stability of PSCs. Its hydrophobic nature and chemical inertness help protect the perovskite layer from external contaminants while also suppressing electrode-induced degradation [148,149]. This has led to highly stable devices, exhibiting no performance degradation even after one year of storage [150,151]. However, these carbon-based PSCs are limited by their PCEs, due to poor crystallinity of applicable perovskite materials and energy band mismatch between the perovskite and the carbon electrode [152,153]. Efforts to maximize the PCEs of the carbon-based PSCs have been conducted to benefit from their durability. Li et al. utilized a moisture-induced secondary growth strategy to improve the crystallinity and optimize the energy levels of the perovskite films and obtain remarkably high-performing carbon-based PSCs. Likewise, Tang et al. utilized an appropriately long alkylammonium spacer cation to form a 2D layer on top of 3D perovskite which balanced the defect passivation, interface charge separation, and charge transfer between the perovskite and carbon electrode in their HTL-free PSCs. This led to a record PCE of about 20% for carbon-based PSCs. Furthermore, no loss in PCE of the device after 1500 h storage in 50% RH/room temperature condition signifies the better stability of the carbon-based PSC.

3. External Degradation Pathways and Mitigation Strategies

3.1. Moisture-Induced Degradation

Atmospheric conditions have been observed to induce a very rapid degradation in the perovskites [154]. The degradation path can be associated with the volatility of hygroscopic nature of perovskite material and hydrophilicity of organic cations, which trigger the formation of defect states. Those defects accelerate the non-radiative recombination, diminish the charge–carrier lifetime, and consequently pave the way for the moisture or oxygen ingress as well as the ion migration [155]. Water acts as a catalyst that triggers the chemical decomposition of perovskites [156]. The decomposition of the perovskite active phase into its constituent components, namely PbI2 and CH3NH3I, is an irreversible process that compromises the integrity of the device [157,158]. The CH3NH3I further breaks down into CH3NH2 and HI, which, upon exposure to oxygen, undergo secondary reactions forming I2 and H2O [156], thereby further accelerating the degradation. Equations (1)–(6), presented below, detail the water-induced degradation mechanism in MAPbI3 perovskites.

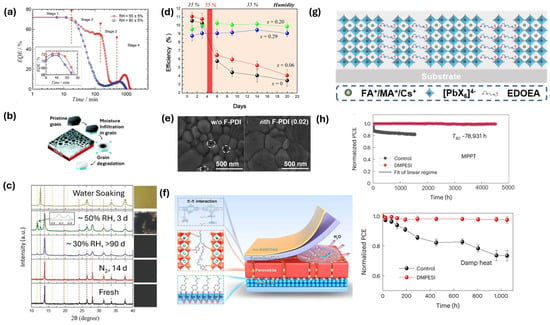

An investigation into the moisture-induced degradation of MAPbI3 single crystals and thin films revealed that, in the early stages of water exposure, a monohydrate perovskite phase forms. This phase is reversible and can fully revert to the original perovskite structure upon exposure to a dry atmosphere. However, prolonged exposure to moisture leads to the formation of a dihydrate phase, resulting in irreversible degradation and the formation of PbI2 within the device [157]. In another study, to understand the degradation mechanism, Song et al. utilized the laser-beam-induced current (LBIC) imaging method to investigate the spatial and temporal evolution of the external quantum efficiency (EQE) of PSCs under controlled humidity [158]. The temporal EQE curve reveals four distinct degradation stages (Figure 6a). In the first stage, an initial increase in EQE was observed, attributed to the passivation of interfacial traps at the perovskite–HTL interface. This was followed by a gradual decline in the second stage, associated with bulk changes in the doping level of the HTL and a reduction in hole collection efficiency within the HTL. The third stage was marked by a sudden drop in EQE, caused by the interaction of water molecules with the perovskite, leading to the formation of low-dimensional hydrated perovskite phases as described in Equations (1) and (2) above. Finally, the fourth stage resulted in irreversible degradation of the perovskite layer, driven by water-catalyzed decomposition into PbI2 and volatile by-products (Equations (3)–(6)). Similarly, Wang et al. investigated the influence of perovskite crystal quality on water-induced degradation [159]. Their study revealed that degradation initiates at amorphous and defect-rich grain boundaries and progressively propagates into the grain interiors (Figure 6b). Furthermore, they demonstrated that increasing the grain size effectively delays moisture-induced degradation, with the results exhibiting a linear dependence between grain size and degradation resistance.

Compared to MAPbI3, the FAPbI3 are more resistant to water-induced degradation. Yun et al. reported that FAPbI3 remains stable under ambient condition with relative humidity up to 30% at room temperature. However, when RH increases to 50%, decomposition occurs by the change in the phase, from the perovskite phase into a non-perovskite phase, which has a yellow color and a bandgap of 2.43 eV. The grain boundaries are assumed to serve as moisture pathways, which initiate the transition from the black perovskite phase to the yellow non-perovskite phase (Figure 6c) [160].

Mitigtation Strategies

Although the external moisture-induced degradation can be reduced significantly by a robust encapsulation, enhancing the internal moisture stability of the perovskite, along with interfacial layers, further aids in gaining better stability against moisture. Various strategies have been investigated to enhance the internal moisture resistance of perovskite devices, and this subsection provides a brief overview of these efforts.

Compositional engineering of the perovskite precursor has been one of the pioneering strategies towards increasing the moisture stability of the PSC devices. Partial replacement of iodides in the perovskite precursor by smaller bromides or chlorides can lead to enhanced Pb–X bonds and compact crystal lattice, which could provide better moisture resistance to the perovskite films. It has also been observed that chloride ion does not fully incorporate into perovskite lattice but acts as a crystal growth modulator promoting larger grain growth with fewer grain boundaries, thereby minimizing the moisture ingress. For instance, Buin et al. utilized both experimental as well as theoretical calculations to determine the stability of different MAPbX3 (X = I, Br, Cl) and found that the chloride perovskites were most stable [161]. Since chloride-based perovskites exhibit significantly lower power conversion efficiencies (PCEs) than their iodide counterparts due to their wider bandgaps, mixed-halide perovskites have been investigated to enhance device stability without compromising the efficiency. Noh et al. investigated the moisture stability of MAPb(I1−xBrx)3 perovskite and found that the cells with were more stable in the humid condition (Figure 6d) [162]. Moreover, the replacement of halides with pseudohalides has also led to enhanced moisture stability of the devices. Pseudohalides could potentially form stronger bonding in the perovskite crystal that lowers the probability of bond cleavage upon moisture exposure. Tai et al. investigated the use of thiocyanate (SCN−) anion in their MAPbI3−x(SCN)x PSC devices and found that the incorporation of (SCN−) not only boosted the moisture stability of their devices but also enhanced the perovskite film preparation in humid environment (70% R.H.) [163]. Recently, Tian et al. incorporated bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)imide (TFSI) pseudohalide in their perovskite precursors and discovered synergistic enhancement in both performance as well as moisture stability of the devices (ambient air/RH-(20–30)%/unencapsulated/T92-2400 h) [164]. Like anion engineering, cation site engineering has also led to significant improvement in the moisture stability of the PSC devices. Formamidinium (FA) cations, having more protons compared to the MA cations, can form enhanced hydrogen bonds with I− anion, thereby stabilizing the perovskite crystal structure, which in turn can enhance moisture stability to the device [165]. Incorporation of some cesium into the FA-based perovskite has been found to increase performance [2] and moisture stability [166]. Incorporation of small inorganic cations suppresses unfavorable phase transitions and reduces the lattice strain as well as defect density in the perovskite crystal, thereby imparting moisture stability to the PSC devices. For instance, Lee et al. fabricated FA0.9Cs0.1PbI3-based PSCs and compared their moisture stability (RH-40%) to pristine FAPbI3 and found that cesium incorporation enhanced the moisture stability by a great extent [167]. Moreover, the incorporation of triple cation FA, MA, and Cs in the perovskite devices resulted in higher stability to the moisture (RH (60–80)%, 15 days, 85% PCE retention) compared to the pristine MA-only PSC devices (40% PCE retention) [168].

Another strategy for enhancing the moisture stability of the perovskite material internally is by the passivation of the grain boundaries and defects in the bulk by using different hydrophobic moieties. Since the initiation of moisture ingress and degradation of the perovskites start from the grain boundaries, enhancement in the grain size and passivation of grain boundaries by hydrophobic entities can reduce the moisture-induced degradation in the PSCs [169]. For example, Gao et al. used amphiphilic fluorinated additive, 1,1,1-trifluoroethylammonium iodide, to their MAPbI3 perovskite which enhanced the perovskite morphology and uniformity. Furthermore, the hydrophobic fluorine entity led to enhanced moisture stability of the device (ambient storage, T92 = 120 days) [170]. Likewise, Yang et al. mixed fluorinated pyrelenediimide (F-PDI) into their perovskite film, which not only enhanced the crystallization of the films resulting in larger grain size (Figure 6e) but also increased the hydrophobicity of the grains by filling at the grain boundaries. This improved the moisture stability of the resulting devices by a great extent [171]. Recently, Hu et al. incorporated 1,1′-methylenbispyridinium dichloride which increased the hydrophobicity of the perovskite film significantly, evidenced by the moisture resistance of up to 180 s on completely water-immersed perovskite films. This resulted in the enhanced continuous operational stability (20 ± 5 °C, 60 ± 10% RH, T80 = 2000 h) of unencapsulated devices [172]. In addition to this, the incorporation of polymeric compound additives in the perovskite precursor has also brought a significant moisture stability in the perovskite devices [173,174,175,176]. The polymers which often contain aromatic rings with long chains are intrinsically hydrophobic, thereby forming a moisture-barrier layer around the perovskite grains. This barrier can act as moisture repellant which slows down the infusion of water molecules inside the perovskite lattice, thereby providing durability against moisture. For instance, Zheng et al. utilized a conductive polymer, polyaniline additive to their perovskite films, which significantly increased the hydrophobicity of the film resulting in the moisture stability of the unencapsulated devices (50% RH, T86 = 1600 h) [173]. Similarly, a research group recently led by Li et al. designed and synthesized a hyperbranched dopamine polymer adhesive (HPDA) which could form a stereoscopic network at the interfaces as well as the bulk of the whole device (Figure 6f), thereby increasing the toughness as well as moisture resistivity of their flexible PSC devices [176]. This strategy improved the bending durability of the flexible PSC devices at higher moisture conditions (bending radius = 3 mm, cycles = 1000, 65% RH, PCE retention = 94.7%). Also, the incorporation of hydrophobic, bulkier cations capable of forming 2D perovskites for grain boundary passivation has been explored for mitigating the moisture-induced instability in the PSC devices [177,178,179,180]. For instance, different diammonium spacer cation-based molecules were mixed with the perovskite precursor, resulting in enhanced crystallization as well as improved moisture resistance [179]. 2,2′-(ethylenedioxy)bis(ethylamine) (EDOEA) spacer cation resulted in Dion–Jacobson type 2D/3D perovskite (Figure 6g), which gave the best results with improved device performance as well as the moisture stability of the device (RH 50 ± 5%, T82 = 1560 h) [179]. In a more recent study, Zhang et al. tested different aromatic spacer cations in the perovskite precursors, among which the pyrenylbutanamine (PyBa) exhibited superior performance [180]. Due to the higher conjugation of spacer cations, the moisture stability of the device has been greatly improved (unencapsulated PSC, 80% RH, T80 = 1600 h). Along with hydrophobicity, the abilities of defect passivation and suppression of ion migration on the grain boundaries of 3D perovskites by the 2D perovskite layer help in mitigating moisture-induced degradation in the PSCs.

The perovskite surface is particularly susceptible to moisture ingress, which can degrade the film and compromise device stability. Thus, surface passivation has also emerged as an effective strategy to enhance the moisture resistance of perovskite solar cells. In addition to improving environmental stability, surface passivation reduces defect densities and promotes better interfacial contact with the upper CTL, facilitating more efficient charge extraction and contributing to higher PCE. Different organic as well as inorganic materials have been utilized for achieving the passivation of the perovskite surface to improve the performance and longevity. For instance, Jiang et al. used 4-fluorophenethylammonium iodide on the perovskite surface without further annealing, and the device showed improved performance as well as stability (ambient air 40% RH storage, T90 = 720 h) [181]. Further heat treatment of such alkylammonium salts after deposition on the perovskite surface leads to the formation of a 2D–3D interface, which might further enhance the moisture stability of the device. Liang et al. employed n-butylamine acetate instead of traditional spacer n-butylamine iodide, by which the strong ionic coordination between the spacer and perovskite framework is favorable for the formation of phase-pure layered perovskite with microscale vertically oriented grains [182]. The devices showed <10% efficiency degradation after storage under RH of 65 ± 10% for 4680 h, under operation at 85 °C for 558 h, or under continuous light illumination for 1100 h. Likewise, the use of sulfonium cations instead of alkylammonium cations has also resulted in improvements in the longevity of perovskite devices. Sulfonium cations exhibit stronger electrostatic interactions with the halide anions and, unlike alkylammonium cations, lack the hydrogen-bond-forming N-H bond, thereby providing greater hydrophobic protection against moisture. One such example is a study by Suo et al. where they make use of sulfonium-based molecules, dimethylphenylsulfonium iodide (DMPESI) for treating the perovskite surface, which resulted in excellent stability of the PSC devices. The devices show less than 1% PCE loss after 4500 h at MPPT, and less than 5% PCE loss under 1050 h of damp heat test (85 °C, 85% RH) as well as thermal cycling test (Figure 6h) [183]. Inorganic materials have stronger chemical bonds and stable chemistry, so they tend to make robust passivation layers as compared to the organic counterparts. Different inorganic metal oxides like AlOx, MoOx, ZrOx, etc., have been utilized for the passivation of the perovskite layer for enhancing the longevity of the devices [184,185,186]. As an example, Choi et al. used both an organic passivation layer (octylammonium iodide) and an ALD-coated thin inorganic AlOx layer for perovskite surface passivation. The solar cell devices with the combined organic and inorganic passivation retained 90% of their initial PCE after 1872 h under 85 °C and 85 % RH [187].

Figure 6.

(a) Laser-beam-induced current-external quantum efficiency (LBIC-EQE) of a perovskite solar cell as a function of time after humidity exposure [158] (Reproduced with permission from John Wiley and Sons, Copyright 2016). (b) Schematics illustrating water-induced degradation of perovskites starting from the grain boundaries [159] (Reproduced with permission from Royal Society of Chemistry, Copyright 2017). (c) XRD pattern of fresh, nitrogen (N2) stored and moisture-exposed (different levels) perovskite solar cells and corresponding pictures of the films are displayed on the side [160] (Reproduced with permission from John Wiley and Sons, Copyright 2018). (d) Moisture stability of the MAPb(I1−xBrx)3 perovskite solar cells [162] (Reproduced with permission from John American Chemical Society Copyright 2013). (e) Top-view scanning electron microscopy (SEM) image of the perovskite surface containing fluorinated pyrelenediimide (F-PDI), the dashed circles show the defective grain boundary in the control perovskite film [171] (Reproduced with permission from John Wiley and Sons, Copyright 2019). (f) Schematics showing the interaction of hyperbranched dopamine polymer adhesive (HPDA)with all other functional layers in the solar cell stack for improved moisture stability [176] (CC BY 4.0). (g) Schematic illustrating the arrangement of 2-dimensional (2D) Dion–Jacobson perovskite grown using large spacer cation 2,2′-(ethylenedioxy)bis(ethylamine) (EDOEA) in 3-dimensional perovskite precursor [179] (Reproduced with permission from John Wiley and Sons, Copyright 2021) and (h) long-term stability in the dimethylphenylsulfonium iodide (DMPESI) surface-treated perovskite solar cells in both maximum power point tracking (MPPT) measurement and damp heat test conditions [183] (CC BY 4.0).

3.2. Temperature-Induced Degradation

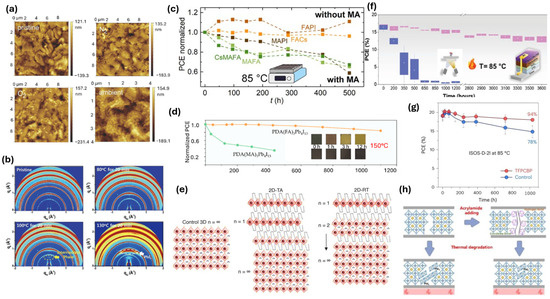

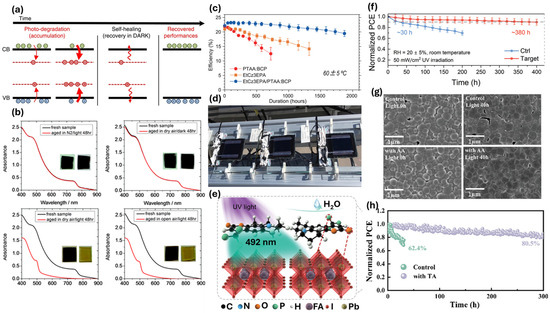

Photovoltaic devices are meant to be deployed in direct sunlight for harvesting solar energy. During regular operation, they often reach temperatures 20–30 °C above the ambient environment [188]. Therefore, under operating conditions, PV devices can experience significant temperature increases above ambient levels. These temperature rises are influenced by a combination of environmental factors, PV system design and installation parameters, and intrinsic thermal properties of the PV materials. To ensure their durability and performance, international standards, such as the IEC 61646 climate chamber tests, specify long-term stability testing at 85 °C. Therefore, addressing thermal instability is crucial for the widespread adoption of perovskite technology. In this section, we examine the impact of thermal stress on perovskite materials and discuss the strategies developed to mitigate temperature-induced degradation mechanisms.