Abstract

Evaluating the coherence of visual narrative sequences extracted from image collections remains a challenge in digital humanities and computational journalism. While mathematical coherence metrics based on visual embeddings provide objective measures, they require computational resources and technical expertise to interpret. We propose using vision-language models (VLMs) as judges to evaluate visual narrative coherence, comparing two approaches: caption-based evaluation that converts images to text descriptions and direct vision evaluation that processes images without intermediate text generation. Through experiments on 126 narratives from historical photographs, we show that both approaches achieve weak-to-moderate correlations with mathematical coherence metrics (r = 0.28–0.36) while differing in reliability and efficiency. Direct VLM evaluation achieves higher inter-rater reliability ( vs. ) but requires more computation time after initial caption generation. Both methods successfully discriminate between human-curated, algorithmically extracted, and random narratives, with all pairwise comparisons achieving statistical significance (, with five of six comparisons at ). Human sequences consistently score highest, followed by algorithmic extractions, then random sequences. Our findings indicate that the choice between approaches depends on application requirements: caption-based for efficient large-scale screening versus direct vision for consistent curatorial assessment.

1. Introduction

The extraction and evaluation of coherent narratives from visual collections has emerged as a challenge in digital humanities, computational journalism, and cultural heritage preservation [1,2]. While progress has been made in evaluating text-based narratives through mathematical coherence metrics and LLM-as-a-judge approaches [3,4], the assessment of visual narrative sequences remains unexplored. This gap is pronounced in domains such as historical photograph analysis, where understanding the narrative connections between images supports knowledge discovery and archival organization.

Visual narratives, defined as sequences of images that form coherent stories, pose evaluation challenges compared to their textual counterparts. Traditional approaches rely on mathematical coherence metrics based on embedding similarities, which require computational resources and technical expertise to interpret [5]. When a visual narrative achieves a coherence score of 0.73, domain experts such as historians, archivists, and journalists often lack the mathematical background needed to interpret angular similarities in embedding spaces or Jensen–Shannon divergence calculations.

Recent advances in vision-language models (VLMs) have opened possibilities for multimodal evaluation tasks [6]. The success of LLM-as-a-judge approaches in various domains suggests that similar paradigms might be applicable to visual content [7]. However, a question remains: Should we evaluate visual narratives by first converting them to textual descriptions, or can direct vision assessment provide different results?

This work investigates two contrasting approaches to visual narrative evaluation. The first is a caption-based method that generates textual descriptions of images before applying LLM evaluation. The second is a direct VLM approach that assesses image sequences without intermediate text generation. Through experiments on historical photographs from the ROGER dataset [5], we address three research questions. First, we examine whether VLM-as-a-judge approaches can serve as proxies for mathematical coherence metrics in visual narrative evaluation. Second, we investigate how caption-based and direct vision approaches compare in terms of correlation with mathematical coherence, inter-rater reliability, and computational efficiency. Third, we explore the practical implications of choosing between these approaches for real-world applications.

The main contributions of our work are as follows: (i) a systematic comparison of caption-based versus direct vision approaches, revealing trade-offs between speed, reliability, and correlation with mathematical metrics; (ii) showing that both approaches achieve similar correlations with mathematical coherence (r ≈ 0.35) despite operating in different modalities, suggesting that narrative quality assessment transcends specific representation formats; (iii) establishes that the VLM-based evaluation achieves higher inter-rater reliability () compared to caption-based approaches (), although at an increased computational cost; (iv) showing that both methods discriminate between human-curated, algorithmically extracted, and random narratives with statistical significance.

2. Related Work

2.1. Visual Narrative Construction and Evaluation

The field of visual narrative analysis has evolved from early work on visual storytelling [8] to approaches for extracting coherent sequences from image collections [9]. The Narrative Maps algorithm [10], originally designed for text, has been adapted for visual narratives by replacing textual embeddings with visual features. Recent work has demonstrated the feasibility of adapting text-based narrative extraction algorithms to image data from collections of historical photographs [11]. However, evaluation remains challenging, as mathematical coherence metrics, while objective, have interpretability issues due to their embedding-based definition.

Historical photograph analysis presents challenges for narrative evaluation. Edwards [12] conceptualizes photographic collections as “material performances of history,” suggesting that narratives emerge both from intentional documentary strategies and subsequent historical interpretation, leaving multiple potentially valid narratives existing within the same collection.

In particular, we note that the narrative structures that we identify in historical photographic collections may not represent explicit authorial intent. Following Schwartz and Cook’s concept of “historical performance” [13], we recognize that narrative coherence in historical photographic collections emerges from both intentional documentary strategies and retrospective historical interpretation. While we cannot definitively establish the narrative intent of the authors, the temporal and thematic relationships between photographs create implicit narrative possibilities that our evaluation methods seek to assess [11].

2.2. Evolution from LLMs to VLMs in Evaluation Tasks

The emergence of LLM-as-a-judge approaches has transformed evaluation across NLP tasks [14]. Recent studies demonstrate that LLMs can assess narrative coherence, achieving correlations with human judgments exceeding 0.80 in some domains [15]. The extension to multimodal evaluation through VLMs represents a natural progression.

Despite the fact that GPT-4o and similar models have shown advanced capabilities in visual understanding tasks [16], including image description, visual question answering, and cross-modal reasoning, their application to narrative evaluation remains underexplored. While some work has used VLMs for story generation evaluation [17], the assessment of algorithmically extracted visual sequences presents different challenges.

Furthermore, the reliability of VLM evaluation has been questioned in recent studies: bias concerns, including position bias and verbosity bias [18], affect both textual and visual evaluation. To address these issues, multi-agent approaches have emerged as a possible solution. In particular, ensemble methods have shown improved consistency over single evaluators [19].

In addition, recent work on visual coherence assessment [20] suggests that some aspects of narrative quality are inherently visual and may be lost in textual translation. However, the question of whether caption-based or direct approaches better capture narrative coherence remains open. In this context, caption-based methods provide interpretability and allow the use of existing text-based evaluation methods [21]. However, such approaches potentially lose visual information that cannot be expressed in text. In contrast, direct vision-based approaches would be able to preserve visual information but would require models capable of visual reasoning and would have a higher computational cost.

In particular, regarding the computational cost of the evaluation schemes, we note that the evaluation time scales linearly with the length of the narrative but quadratically with the pairs of comparisons, making pairwise evaluation impractical for large collections [22]. However, cost analyses report that the use of VLMs leads to a reduction of 98% compared to human evaluation in industrial applications [23].

2.3. Reliability and Agreement in VLM-Based Evaluation

VLMs achieve documented human agreement levels of 70% overall, with pairwise comparison reaching 79.3% agreement according to the MLLM-as-a-Judge benchmark [24]. These established reliability levels inform expectations for VLM-based narrative evaluation and provide benchmarks for assessing evaluation quality. Studies examining multi-agent systems report that performance improvements plateau after 3–5 agents, while computational costs continue scaling linearly [4,25]. This finding suggests that the use of three independent judges balances statistical reliability with computational feasibility for narrative evaluation tasks. The Prometheus-Vision model achieves a Pearson correlation of 0.786 with human evaluators on vision-language benchmarks, demonstrating open-source alternatives [26]. However, GPT-4’s documented performance in narrative tasks and stable API availability make it suitable for establishing baseline evaluation protocols.

Including unreliable judges in evaluation ensembles can degrade overall performance, with visual language model studies warning against indiscriminate ensemble construction [27]. In this context, a temperature setting of 0.7 provides sufficient stochasticity for multi-agent diversity while maintaining evaluation coherence, as shown in previous studies [4].

2.4. Caption-Based Versus Direct Vision Evaluation Paradigms

The choice between caption-based and direct vision evaluation involves documented trade-offs. In particular, a previous study on knowledge-intensive visual question answering reported that caption-based approaches match or exceed direct image processing performance when language models compensate for caption limitations [28]. This finding motivates our comparison of both approaches for narrative assessment.

Furthermore, industrial applications document order-of-magnitude efficiency differences between caption-based and direct vision processing, with caption approaches requiring substantially fewer computational resources [23]. This efficiency gap suggests that practical deployment may require choosing between speed and evaluation mode. However, the loss of information inherent in caption generation affects downstream evaluation. Furthermore, visual storytelling research documents that textual descriptions fail to capture spatial relationships, visual style, and implicit emotional content [8]. These limitations suggest that caption-based evaluation may introduce additional variance through the intermediate representation step.

In addition, previous studies on the evaluation of automatically extracted narratives in text show diminishing returns from additional complexity in the evaluation prompt, with simple prompts achieving performance within 10-15% of complex approaches [4]. Confidence calibration studies have shown that both GPT-4o and Gemini Pro exhibit overconfidence in their evaluations [29]. Fixed scoring scales with explicit anchors provide reference points that can reduce relative scoring variance compared to an unconstrained assessment. Thus, simple structured evaluation methods with VLMs could be sufficient for most practical evaluations of extracted narratives.

2.5. Hallucination and Structured Output Constraints

VLM hallucination studies report 100% accuracy in familiar visual content but only 17% accuracy in counterfactual images, indicating the dependence on training data patterns [30]. This risk of hallucination motivates the use of constrained output formats in evaluation tasks. Structured output formats reduce evaluation errors compared to free-form responses [31]. In this context, JSON schemas and function-calling APIs provide mechanisms to enforce consistent scoring while limiting opportunities for fabrication.

2.6. Historical and Cultural Context in Visual Evaluation

The evaluation of historical photographs with VLMs faces specific challenges due to the nature of historical images and their context. In particular, scholars have documented the disparities between Western and non-Western cultural content in vision-language models [32]. These biases affect the consistency of the evaluation for cross-cultural narratives and historical expeditions. While VLMs show competence with contemporary imagery, their performance in historical content remains understudied. The temporal distance between training data (predominantly modern) and historical photographs may introduce systematic evaluation biases. Providing explicit temporal context and dataset-specific prompting partially addresses these limitations in our experiments. Visual anthropology frameworks establish that historical photographs function as both documentary evidence and cultural interpretation [12]. Thus, multiple evaluation approaches may be necessary: caption-based for interpretive aspects and direct vision for visual evidence preservation.

3. Methodology

3.1. Dataset and Experimental Setup

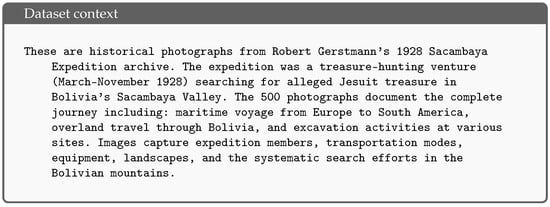

We evaluated our approaches using the ROGER dataset [11], which contains 501 photographs from Robert Gerstmann’s 1928 Sacambaya Expedition in Bolivia [9]. This treasure hunt expedition provides a source for narrative extraction, with images that capture the journey from maritime departure through overland travel to excavation activities.

The dataset includes expert-curated baseline narratives of varying lengths (5–30 images) that serve as human ground truth. A domain expert with deep knowledge of the expedition created these baselines using primary documentary sources, including S.D. Jolly’s 1934 narrative account “The Treasure Trail” [33] and contemporary newspaper reports [34]. The images were labeled according to expedition stages, such as marine transport and excavation sites, with approximate dates providing partial supervision for narrative extraction.

3.2. Narrative Extraction Methods

We extract three types of narratives to establish a quality gradient. Human baselines consist of expert-curated sequences that follow the historical chronology of the expedition, ranging from 5 to 30 images. These represent the gold standard for narrative coherence. Narrative Maps extraction employs algorithmically extracted paths using a semi-supervised adaptation of the Narrative Maps algorithm [10]. The algorithm maximizes the minimum coherence between consecutive images while ensuring coverage of different thematic clusters, with 10 replications extracted for each baseline length. Random sampling provides baseline narratives created by randomly selecting images between fixed start and end points, maintaining chronological order but without coherence optimization. These establish a lower bound for narrative quality.

3.3. Evaluation Framework

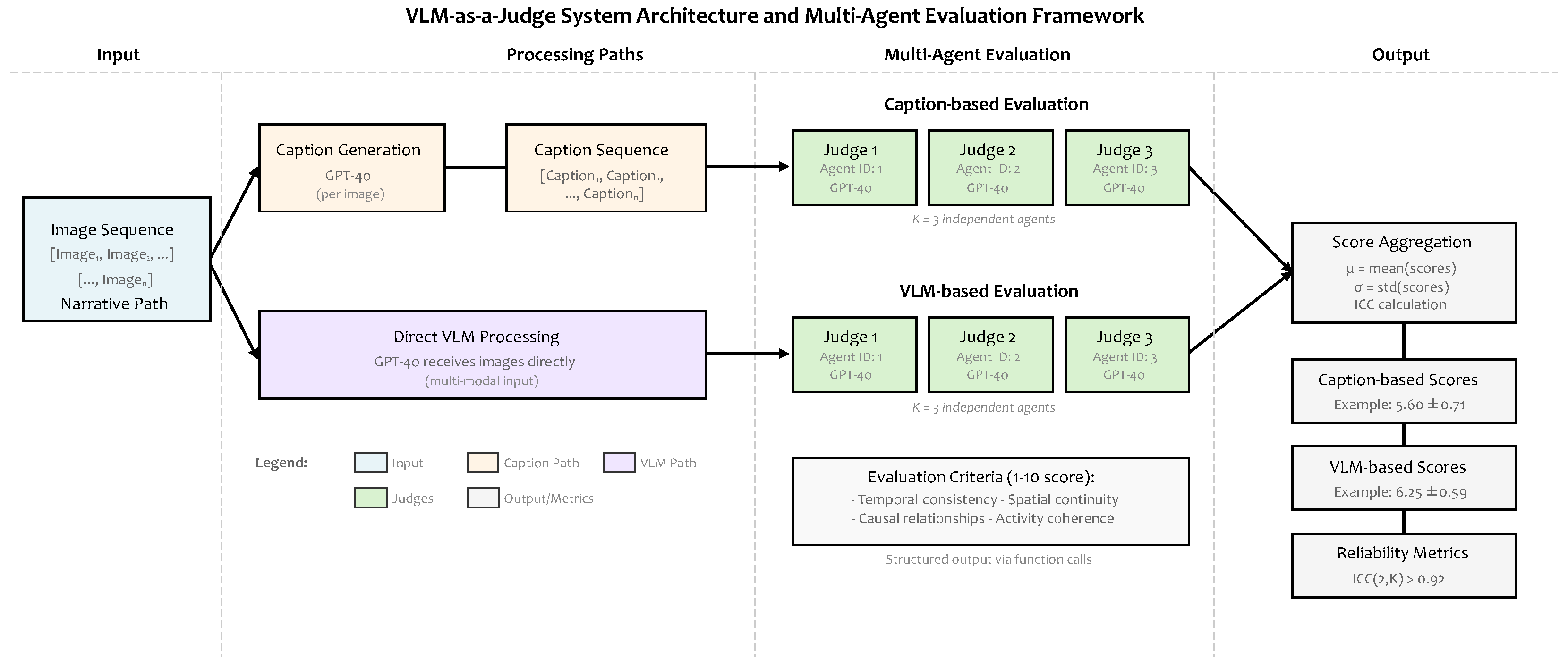

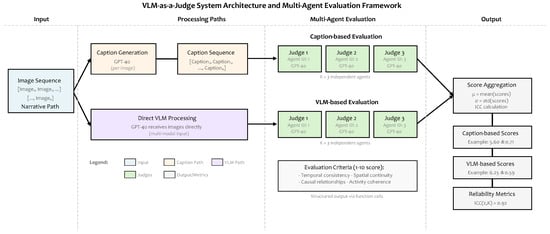

Our evaluation framework compares two different approaches for assessing visual narrative coherence, each with distinct computational and methodological trade-offs. The first approach converts visual content to textual descriptions before applying linguistic evaluation techniques, leveraging established LLM capabilities for narrative assessment. The second approach directly processes image sequences through vision-language models, preserving visual information that may resist textual representation. To ensure reliability and measure consistency across both methods, we employ multiple independent judge agents with structured output constraints. Figure 1 illustrates the complete evaluation architecture, showing how image sequences flow through each approach to produce comparable coherence scores and reliability metrics.

Figure 1.

Comparative evaluation framework for VLM-as-a-Judge approaches. The diagram illustrates two contrasting methods for evaluating visual narrative coherence: (1) Caption-based evaluation (upper pathway) that first converts images to textual descriptions using GPT-4o before applying linguistic evaluation and (2) direct VLM evaluation (lower pathway) that processes images directly through a multi-modal input. Both methods employ independent judge agents to ensure reliability. The evaluation criteria focus on four dimensions: temporal consistency, spatial continuity, causal relationships, and activity coherence, with structured output constraining scores to a 1–10 scale. Final aggregation computes mean scores, standard deviation, and inter-rater reliability (ICC) to enable a systematic comparison between the two approaches.

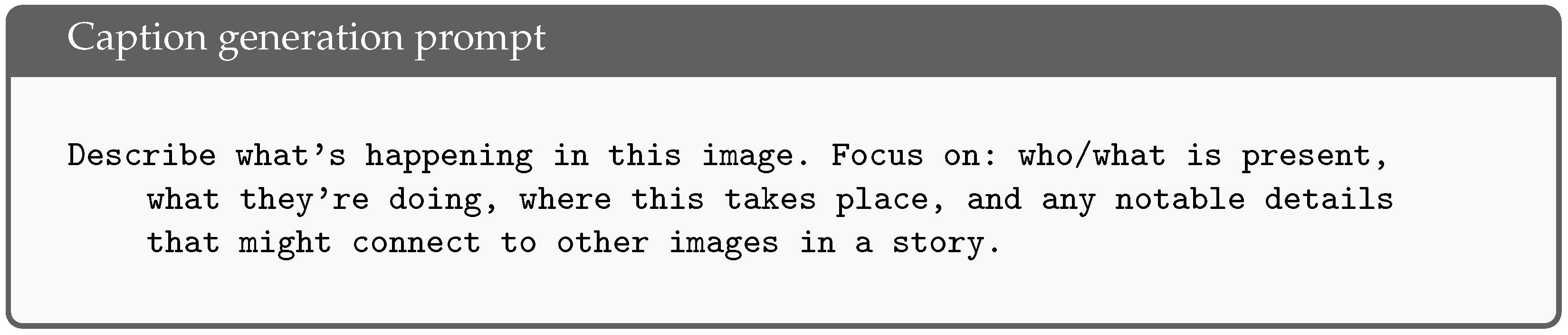

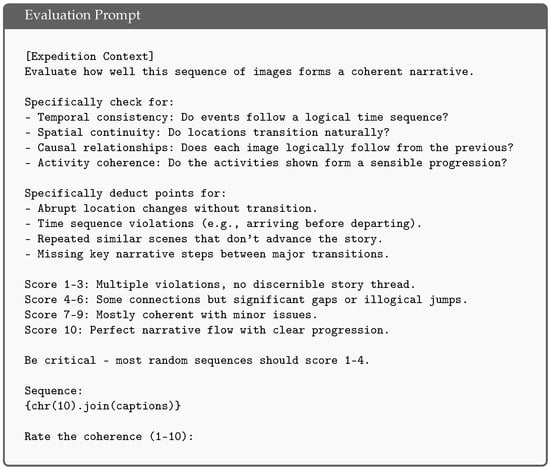

Caption-Based and Direct VLM Evaluation: First, the caption-based approach consists of two stages. First, we generate textual descriptions of each image using GPT-4o with the following prompt, as shown in Figure 2. Captions are cached to avoid redundant generation, with each image receiving a 150–200-word description. We incorporate available metadata, including location tags and dates, when present. The evaluation phase uses GPT-4o with the structured prompt shown in Figure 3.

Figure 2.

Caption generation prompt.

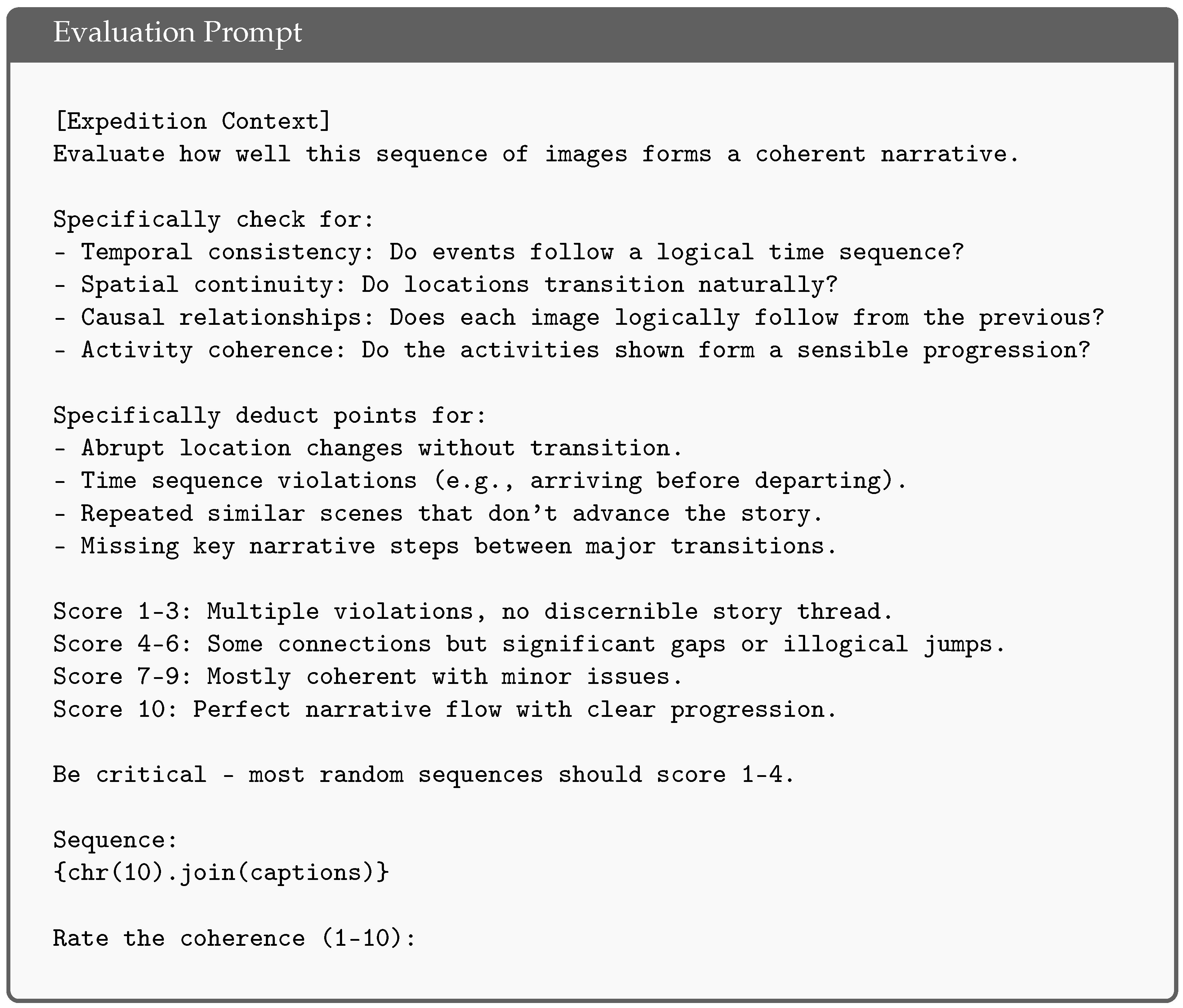

Figure 3.

Evaluation prompt for both approaches. [Expedition Context] refers to an additional string that includes a general description of Robert Gerstmann’s expedition to provide context to the language model.

Second, the VLM approach directly evaluates image sequences without intermediate text generation. The images are resized to 512 × 512 pixels and encoded as base64 strings. The evaluation uses the same prompt structure that focuses on visual elements shown in Figure 3, removing the part with the captions and simply including the encoded images with the proper narrative ordering.

The expedition context inserted into each prompt is provided in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Dataset context provided to the evaluation models.

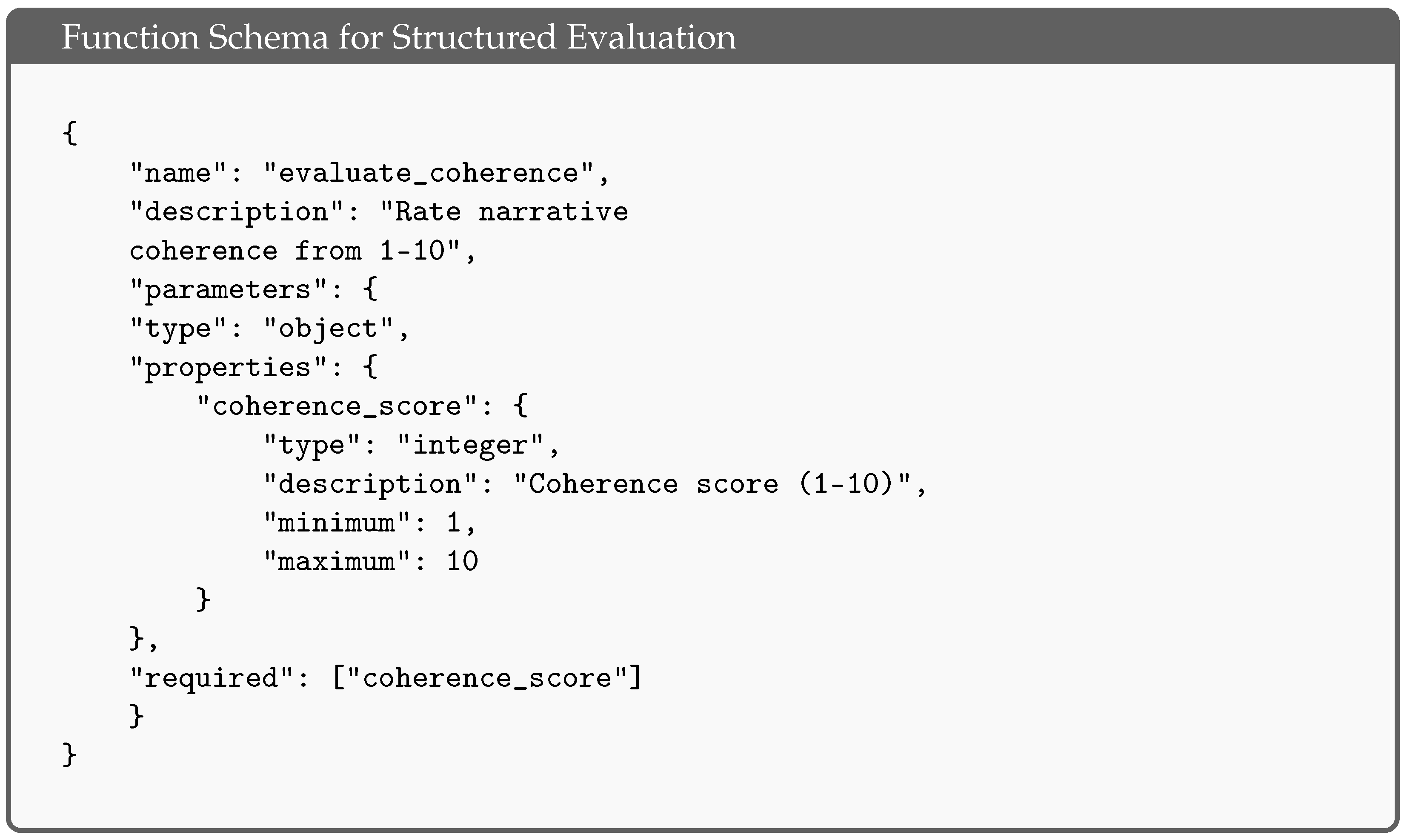

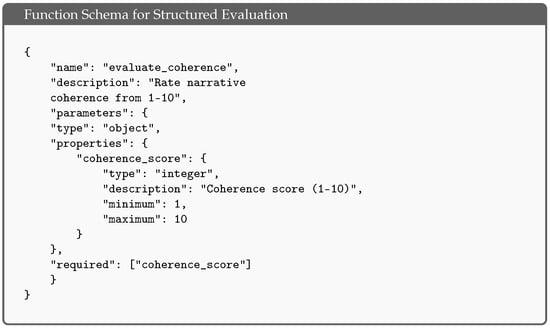

Structured Output Schema: To ensure consistent evaluations, we employ OpenAI’s function-calling feature with predefined schemas. The evaluation function schema is defined as shown in Figure 5 and is based on previous work on LLM-as-a-judge approaches for narrative extraction evaluation [4].

Figure 5.

Function schema for both of our evaluated judge models.

Multi-agent Setup: To ensure reliability and measure consistency, we employ K independent evaluator agents, with based on previous studies indicating that a number of agents from 3 to 5 is sufficient for reliable evaluations [4,25]. Each agent uses a temperature setting of 0.7 with different random seeds to introduce controlled variation through sampling randomness.

3.4. Mathematical Coherence Baseline

We compute mathematical coherence following established methods in narrative extraction [3,5]. Contemporary vision-language embedding models employ various architectures—BLIP-2 achieves improved alignment through Q-Former architectures [35], while SigLIP uses sigmoid loss for efficiency [36]. Our prior work used DETR for visual feature extraction [11].

For this study, visual features are extracted using CLIP (clip-vit-base-patch32) [37], producing 512-dimensional embeddings for each image. This choice provides established embedding-based coherence metrics that serve as a reference point for validating our VLM-as-a-judge approaches.

The coherence between consecutive images i and j in a narrative path is calculated as

where

- are the CLIP embeddings for the images i and j;

- represents the angular similarity of the images in the embedding space;

- are cluster membership probability distributions;

- represents topic similarity based on Jensen-Shannon divergence.

This metric, previously validated for text-based narrative evaluation using LLM-as-a-judge approaches [4], is extended here to the visual domain. For narratives without explicit clustering, we use uniform distributions, resulting in and coherence determined solely by visual similarity.

For each narrative path, we compute three summary metrics:

- Minimum coherence: The lowest value between consecutive pairs (weakest link).

- Average coherence: Mean across all consecutive pairs.

- DTW distance: Dynamic Time Warping distance to human baseline narratives.

3.5. Evaluation Metrics

We assess performance through multiple metrics. The correlation analysis employs Pearson correlations between the VLM and caption scores with mathematical coherence. Inter-rater reliability uses the Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC) and Cronbach’s to measure agreement between independent judges. Discrimination ability is measured through Cohen’s d effect sizes and t-tests comparing scores between narrative types. Computational efficiency tracks execution time and token usage for each approach.

4. Results

We evaluated 126 image narratives from the ROGER dataset using caption-based and direct VLM approaches, with each narrative assessed by independent judges to ensure reliability. Our evaluation encompassed three narrative sources: human-curated baselines (), algorithmically extracted sequences using the Narrative Maps algorithm (), and random chronological paths (), providing a clear quality gradient for the assessment.

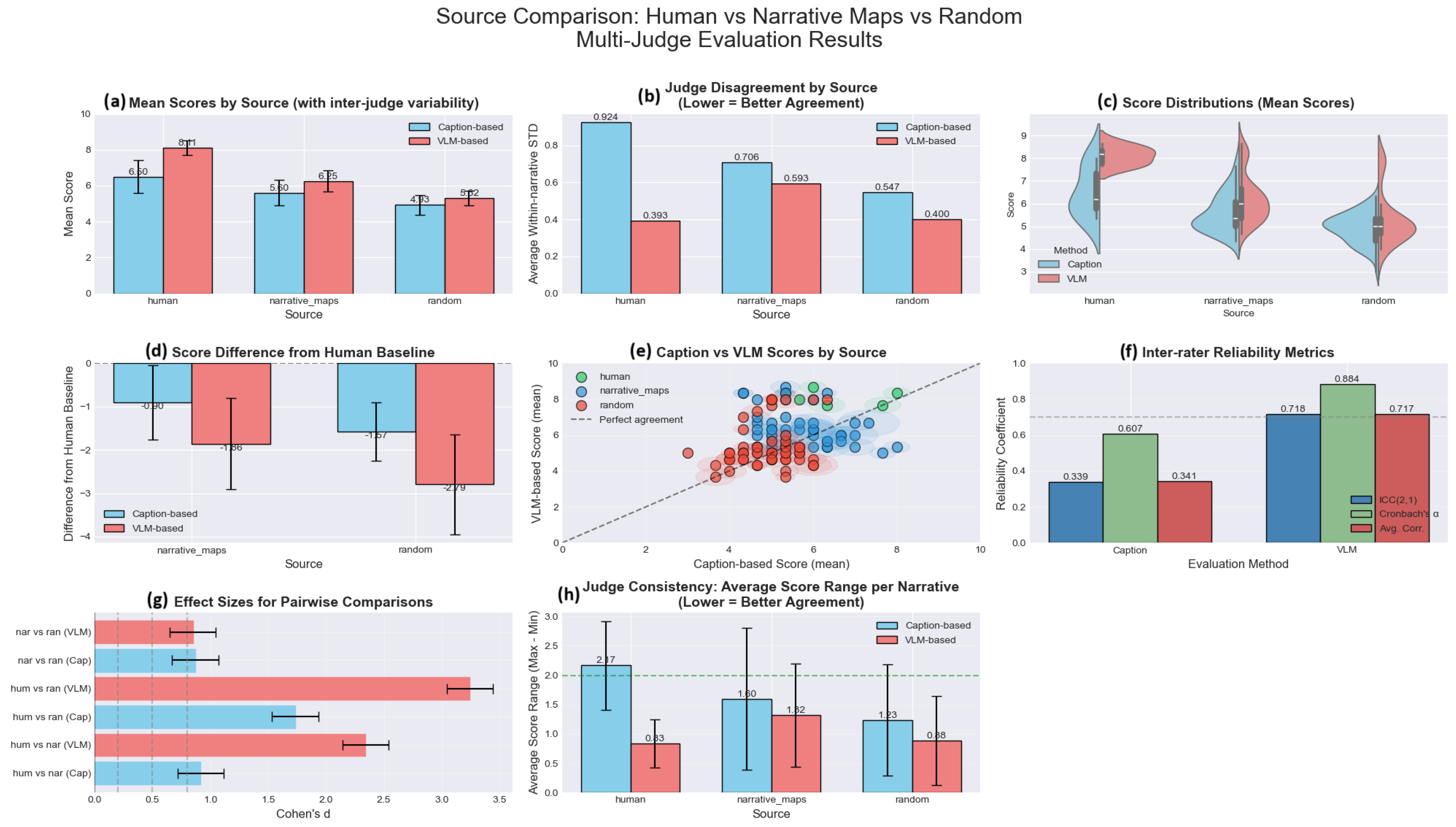

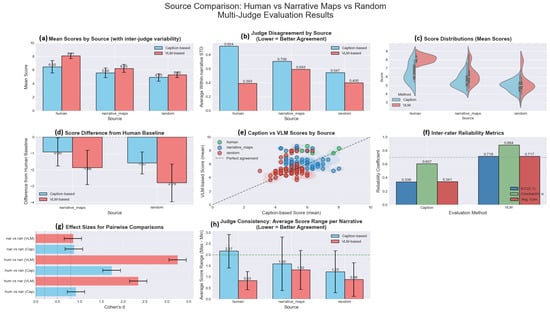

Figure 6 presents an analysis of our multi-judge evaluation results. The mean scores by source (panel a) demonstrate clear quality stratification: human baselines achieve the highest scores (caption: , VLM: ), followed by Narrative Maps (caption: , VLM: ), with random sequences scoring lowest (caption: , VLM: ). Judge disagreement analysis (panel b) shows superior agreement for VLM evaluation, with consistently lower within-narrative standard deviations across all sources.

Figure 6.

Comparison of narrative quality across three sources (human ground truth, Narrative Maps algorithm, and random baseline) evaluated by two approaches: Caption-based (converting images to text) and direct VLM-based assessment. Each narrative was independently scored by 3 judges. (a) Mean coherence scores (1–10 scale) with inter-judge variability shown as error bars, demonstrating clear separation between sources with Human > Narrative Maps > Random. (b) Average within-narrative standard deviation quantifying judge disagreement, where lower values indicate better agreement. (c) Violin plots showing score distributions across all narratives per source. (d) Performance gaps relative to human baseline show differences between algorithmic approaches and ground truth. (e) Scatter plot comparing evaluation methods shows weak correlation () with systematic differences in scoring scales. (f) Inter-rater reliability metrics indicate moderate reliability for VLM-based () and poor reliability for caption-based () evaluation. (g) Cohen’s d effect sizes confirm statistically significant differences between all source pairs. (h) Judge consistency measured by score range per narrative shows that VLM judges achieve better agreement than caption judges.

The score distributions (panel c) and the difference from the human baseline (panel d) confirm that both methods successfully discriminate between narrative types, although the evaluation of VLM shows greater separation between quality levels. The caption versus the VLM scatter plot (panel e) shows a weak correlation between the methods (), suggesting that they capture different aspects of narrative coherence. In particular, the reliability metrics between the judges (panel f) show a higher reliability of VLMs with versus caption-based .

The effect size analysis (panel g) confirms statistical significance across all pairwise comparisons, while the consistency measurements of the judges (panel h) show that the VLM judges achieve better agreement with lower score ranges per narrative. These patterns establish that while both approaches identify narrative quality gradients, they operate through distinct evaluation mechanisms—caption-based focuses on semantic coherence and VLM emphasizes visual continuity.

4.1. Overall Performance Comparison

Table 1 presents evaluation scores for all narrative types, demonstrating that both the VLM and caption-based methods successfully identify the quality gradients of the narrative.

Table 1.

Evaluation scores by narrative source and method.

The results validate our evaluation framework across all three assessment approaches. Human-curated narratives consistently achieve the highest scores, showing that expert-selected sequences represent the quality benchmark. Narrative Maps extractions score above random sampling yet below human curation, confirming that the algorithmic extraction method produces coherent narratives superior to chance while not reaching expert-level selection. Random chronological sampling produces the lowest scores on all metrics and serves as an effective lower bound. This consistent ranking pattern (Human > Narrative Maps > Random) holds across caption-based evaluation, VLM-based evaluation, and mathematical coherence metrics, providing convergent validity for our assessment methods. While the VLM approach uses a different scoring scale (systematically 0.61–1.86 points higher), both evaluation methods and the mathematical coherence metric agree on relative narrative quality, suggesting that our VLM-as-a-judge approaches successfully capture the same underlying narrative coherence that mathematical metrics measure.

4.2. Correlation with Mathematical Coherence

Despite operating in different modalities, both approaches achieve similar correlations with mathematical coherence metrics, as presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Correlation with mathematical coherence.

The correlation magnitudes of approximately 0.35 warrant contextual interpretation. These moderate correlations are reasonable given that (1) perfect correlation would indicate redundancy between mathematical and judge-based metrics, (2) the consistent discrimination between narrative types (all ) demonstrates practical utility regardless of absolute correlation values, and (3) the evaluation bridges fundamentally different assessment paradigms (embedding geometry versus semantic judgment). These correlations suffice for our primary goal of establishing whether VLM-based evaluation can serve as a proxy for mathematical coherence metrics.

Beyond mathematical coherence, we employ the DTW distance as a complementary metric. DTW measures how algorithmically extracted sequences align with human-curated ground truth narratives, quantifying agreement with expert curatorial judgment. The opposite signs for the DTW distance correlation show a fundamental divergence in evaluation philosophy. Caption-based scores increase with the DTW distance (), indicating disagreement with human baselines, while VLM scores decrease (), indicating agreement. This suggests that caption-based evaluation may prioritize linguistic coherence over visual narrative structure, while VLM evaluation aligns more closely with human curatorial judgment.

Alternative evaluation metrics from other domains are not directly applicable to our task. Edit Distance and Longest Common Subsequence assume discrete symbols rather than continuous image sequences [38]. Video understanding metrics—such as temporal IoU [39], frame-level precision/recall, or clip ordering accuracy [40]—require predetermined event boundaries unavailable in exploratory narrative extraction. Perceptual metrics such as FID [41] or LPIPS [42] evaluate visual quality rather than narrative coherence. Graph-based metrics such as betweenness centrality [43] measure structural properties but not semantic coherence.

We selected mathematical coherence as our primary baseline because it (1) directly measures what narrative extraction algorithms optimize, (2) requires no ground truth beyond end-point specification, and (3) provides interpretable values (0–1 range) validated in prior work. Moderate correlations with VLM evaluations () combined with the DTW divergence patterns suggest that both approaches capture complementary aspects of narrative quality: mathematical coherence focuses on embedding geometry, while VLM judges assess semantic flow, with VLM better matching human curatorial decisions.

4.3. Inter-Rater Reliability

Table 3 presents inter-rater reliability metrics from our experiments with independent judges evaluating 126 narratives.

Table 3.

Inter-rater reliability and agreement metrics across evaluation methods.

The VLM-based approach demonstrates substantially higher inter-rater reliability than caption-based evaluation across all metrics. The single-judge VLM evaluation achieves moderate reliability (), while the caption-based evaluation shows poor reliability (). When averaging across three judges, VLM reaches good reliability (ICC(2,3) = 0.884) while caption-based achieves only moderate reliability (). Pairwise correlations confirm this pattern, with the VLM judges showing strong agreement (mean ) compared to weak agreement for the caption-based judges (mean ). The higher within-narrative variability for caption-based evaluation, particularly for human narratives (STD = 0.924 vs. 0.393), suggests that evaluating from textual descriptions rather than visual content directly introduces additional sources of disagreement, as judges interpret the same linguistic descriptions differently.

4.4. Statistical Discrimination Between Narrative Types

Both evaluation methods successfully discriminate between narrative types with varying degrees of statistical significance. Table 4 presents pairwise comparison results including effect sizes.

Table 4.

Statistical comparison between narrative types. Effect sizes indicate practical significance (small: , medium: , large: ).

The VLM-based approach demonstrates superior discrimination capabilities with larger effect sizes for comparisons involving human baselines (mean for human comparisons) compared to caption-based evaluation (mean for human comparisons). In particular, the VLM method achieves a very large effect size () when distinguishing human-curated narratives from random sequences, indicating a strong sensitivity to narrative quality. Both methods maintain statistical significance for all pairwise comparisons (), and most comparisons reach . The smaller sample size for human narratives () compared to algorithmic methods () reflects the limited availability of expert-curated ground truth sequences in the ROGER dataset.

The limited number of human-curated baselines () reflects practical constraints common in digital humanities research, where expert annotation requires deep domain knowledge and careful analysis of primary sources. While the sample size is small, the effect sizes presented in Table 4 exceed Cohen’s benchmarks for “large” effects (), with human comparisons yielding . Such effect sizes suggest adequate statistical power to detect meaningful differences between narrative types despite the imbalance in sample size.

4.5. Computational Efficiency

The caption-based approach presents speed advantages over direct VLM evaluation, even after accounting for initial setup costs. Table 5 presents the computational requirements measured during our experiments with 126 narratives.

Table 5.

Computational efficiency comparison between evaluation methods.

The experimental results show an efficiency trade-off that depends on both dataset size and evaluation scope. The evaluation times in Table 5 are derived by multiplying the measured per-narrative times by the number of narratives (126) and judges (3), which yields approximately 325 s for caption-based evaluation and 3515 s for VLM-based evaluation. While caption-based evaluation processes narratives 10.8× faster than VLM-based evaluation after initial setup (0.86 s vs. 9.30 s per narrative), this advantage requires amortizing the one-time caption generation cost. With an estimated 2.5 s per unique image, processing the complete ROGER dataset of 501 images requires approximately 20.9 min of initial setup, establishing a break-even point at approximately 50 narratives (, where I represents unique images).

For our experiments with 126 narratives from 501 images, the caption-based approach completes faster even in a first-run scenario (26.3 min vs. 58.6 min for VLM-based). This advantage becomes more pronounced for subsequent evaluations, as cached captions eliminate the setup cost entirely, reducing the per-experiment time from 26.3 to 5.4 min. However, this relationship scales with the size of the dataset: small collections () favor caption-based approaches for nearly all use cases, medium collections () require case-by-case analysis, while large archives () favor VLM-based evaluation unless conducting extensive systematic studies involving hundreds of narratives. Applications requiring repeated evaluations, parameter tuning, or multiple experimental conditions on the same image collection would benefit from caption-based caching, while one-time exploratory analyses of large archives favor the VLM approach despite longer per-narrative processing times.

However, the efficiency of the evaluation process must be contextualized within the broader narrative extraction pipeline. As documented in our survey [3], current narrative extraction algorithms present significant computational challenges: the Narrative Maps algorithm requires solving linear programs [10], while pathfinding approaches require computing pairwise coherence scores across entire collections [5]. Thus, narrative extraction itself involves substantial computational overhead that must be considered alongside evaluation costs, which we have omitted to focus purely on the evaluation procedure.

4.6. Alternative Evaluation Baselines and Metrics

While our work compares caption-based and direct vision approaches against mathematical coherence metrics, we acknowledge that other evaluation paradigms exist. Human evaluation remains the gold standard but is prohibitively expensive on scale [7,14]. Automated video understanding metrics, such as temporal IoU [44] or event ordering accuracy [45], assume ground truth event sequences that are not available in general narrative extraction tasks. Visual storytelling metrics such as VIST [8] evaluate generated stories rather than extracted sequences. Our mathematical coherence baseline, while imperfect, provides a consistent and interpretable metric validated in prior narrative extraction work [5,10]. The moderate correlations that we observe () align with early-stage evaluation systems in other domains before optimization.

4.7. Qualitative Observations

We note that caption-based evaluations focus on semantic connections and narrative logic, noting journey narratives from ship departure to inland travel or identifying temporal inconsistencies when arrival at excavation sites is shown before overland travel. VLM-based evaluations emphasize visual continuity and compositional elements, observing consistency in photographic style and period clothing, or noting transitions from maritime scenes to mountain landscapes. These differences suggest that the approaches capture different aspects of narrative quality.

4.8. Reasoning-Based Model Exploration

We conducted additional experiments with Qwen2.5-VL:7b, a recent open-source vision-language model, on a subset of our dataset (6 human-generated narratives, 30 narrative maps, and 30 random narratives) comparing the two evaluation methods (caption-based and VLM-based).

Table 6 presents the comparative results. Qwen showed discriminative capabilities in both caption-based and direct vision modes, successfully distinguishing between narrative types. These results are consistent with the GPT-4o evaluation. However, the model exhibited unexpected behavior: caption-based evaluation produced more intuitive score patterns (Human > Narrative Maps > Random) with means of , , and , respectively. In contrast, direct vision evaluation showed a reversed pattern for Narrative Maps (), scoring higher than human baselines (), suggesting a potential sensitivity to visual characteristics not captured in textual descriptions.

Table 6.

Qwen2.5-VL:7b evaluation results across narrative types.

The high variance in Qwen’s evaluations ( to ) compared to GPT-4o ( to ) suggests that while reasoning-based open-source models show promise, they can require additional calibration for narrative evaluation tasks. An in-depth comparison across multiple reasoning-based architectures would require extensive experimentation beyond the scope of this work. However, these preliminary results indicate that the choice of model significantly affects the narrative evaluation.

4.9. Narrative Breaking Point Identification

To address whether evaluation models can provide actionable diagnostic feedback, we tested GPT-4o’s ability to score individual transitions and identify weak points within narratives. We evaluated 66 complete narratives (6 human, 30 Narrative Maps, 30 random) by having the model score each consecutive image pair transition on a 1–10 scale.

The results showed clear differentiation by narrative source: human narratives received mean transition scores of , Narrative Maps sequences scored , and random sequences scored . While the differences between human and Narrative Maps narratives were minimal (), both algorithmic and human-curated sequences demonstrated superior transition quality compared to random baselines ().

The model consistently identified specific transition types as disruptive: abrupt location changes without contextual bridges (e.g., “ocean voyage to mountain excavation without overland travel”), temporal inversions (“arrival at excavation site before departure from port”), and thematic discontinuities (“equipment preparation followed by unrelated landscape”). This diagnostic capability suggests potential for incorporating transition-level feedback into narrative extraction algorithms, enabling iterative refinement of weak connections rather than holistic rejection of suboptimal sequences.

However, further validation of breaking point identification would require ground truth annotation of transition quality, a labor-intensive process requiring expert judgment for each consecutive image pair. We leave such a detailed validation for future work while noting that the consistent patterns observed across narrative types support the model’s ability to identify structural weaknesses.

4.10. In-Context Learning Effects

To investigate whether providing example narratives improves evaluation consistency, we conducted experiments with and without in-context learning anchors. Using GPT-4o, we evaluated 55 narratives under two conditions: (1) with examples showing a high-quality human narrative (score: 8) and a low-quality random narrative (score: 3) and (2) without examples using only the standard evaluation prompt. The reduced sample size reflects the exclusion of the sample narratives themselves from the evaluation (five human baselines were evaluated, with one reserved as a positive example).

Table 7 presents the results. Contrary to our expectation that examples would reduce variance, in-context learning actually increased evaluation variability across all narrative types. The human narratives showed identical means () but a higher standard deviation with examples ( vs. ). The Narrative Maps sequences displayed similar patterns (with: ; without: ), as did random sequences (with: ; without: ).

Table 7.

In-context learning effects on evaluation consistency.

This unexpected result suggests that, while in-context examples may help calibrate absolute scoring scales, they introduce additional variance through example-specific anchoring effects. Judges may interpret the provided examples differently, leading to divergent scoring strategies rather than convergent calibration. For production systems prioritizing consistency over absolute accuracy, our findings suggest that omitting in-context examples may yield more stable evaluations, although this conclusion requires validation across different example selection strategies and narrative domains.

5. Discussion

5.1. Complementary Strengths of Each Approach

Our results suggest a speed–reliability trade-off between caption-based and VLM approaches for visual narrative evaluation. The speed advantage of the caption-based method, which processes narratives ten times faster, could make it practical for large-scale applications that do not require high consistency. In contrast, the reliability of the VLM approach, with an ICC of 0.718 compared to 0.339 for captions, provides consistent assessments.

The correlations with mathematical coherence of approximately 0.35 suggest that both methods capture aspects of narrative quality through mechanisms different from embedding-based approaches. The caption-based approach leverages linguistic representations of visual content, benefiting from the training of the underlying LLMs on textual narratives. The VLM approach preserves visual information that may be difficult to express textually, such as compositional consistency or photographic style.

5.2. The Reliability–Speed Trade-Off

The difference in inter-rater reliability merits consideration. The lower ICC of the caption approach (0.339) indicates variability between judges when interpreting the same textual descriptions. While all judges receive identical pre-generated captions, the linguistic representation of visual content appears to introduce more ambiguity in evaluation compared to direct visual assessment. Textual descriptions may allow for more varied interpretations of narrative coherence, as judges must infer visual continuity from words rather than directly observing it.

The reliability of the VLM approach (0.718) suggests that direct vision evaluation provides stable assessment criteria. When judges see the same visual information simultaneously, they converge on similar quality judgments. This reliability advantage may justify the computational cost for applications that require consistent evaluation standards.

While caption-based evaluation offers computational efficiency advantages (26.3 vs. 58.6 min for 126 narratives), the practical significance of this 32-min difference diminishes when contextualized against research time scales and quality considerations. For our experimental scope, this translates to approximately 5 additional seconds per evaluation—a negligible cost relative to the ICC improvement from 0.339 to 0.718 and the alignment with human curatorial judgment (DTW correlations of vs. ). The caption-based approach’s efficiency advantage becomes meaningful primarily in three scenarios: (1) real-time or interactive applications requiring immediate feedback, (2) truly massive-scale evaluations involving thousands of narratives where time costs compound significantly, or (3) resource-constrained environments with strict computational budgets. For typical research applications that involve systematic evaluation of image collections, the superior reliability and validity of the VLM approach justify the computational overhead.

5.3. Implications for Different Application Domains

Our findings suggest some potential selection criteria for choosing between approaches in the domain of historical photographic archives. For example, in large-scale screening applications such as archive processing, the caption-based approach offers advantages. In particular, the ability to cache descriptions enables efficient re-evaluation and provides human-readable intermediate outputs useful for debugging. In contrast, for curatorial decisions and academic research, the reliability of the VLM approach could justify the additional computational cost. Moreover, the higher inter-rater agreement reduces the need for multiple evaluations to achieve consensus. However, for interactive systems, a hybrid approach might be optimal, using a caption-based evaluation for initial screening followed by a detailed VLM evaluation for promising candidates.

The architectural differences between approaches—caption-based operating on linguistic representations while VLM processes visual information directly—suggest that the reliability–efficiency trade-off we observe may transcend specific visual domains. However, the absolute values of the correlation and ICC metrics would depend on the characteristics of the dataset, including the temporal period, photographic conventions, and cultural context. Further validation in other domains is necessary to check the generalizability of these findings.

5.4. Understanding the DTW Distance Divergence

The divergent DTW correlations show that caption-based and VLM approaches not only process narratives differently but also disagree on what constitutes alignment with human curatorial judgment. The caption-based evaluation shows a positive correlation with the DTW distance (), which means that higher scores occur when narratives differ more from human baselines. This method may prioritize linguistic connections over visual narrative structure. The VLM approach shows the opposite pattern with a negative correlation ()—its scores decrease as the distance from human baselines increases. These results indicate that the VLM-based evaluation matches human curatorial choices more closely and may preserve visual narrative elements that are difficult to express in text. This finding has implications for applications requiring human-like narrative assessment: systems that seek to replicate human curatorial decisions should favor VLM evaluation despite computational costs, while those seeking alternative narrative perspectives could benefit from the different criteria of caption-based evaluation.

5.5. Limitations

Our work is not without limitations. First, our evaluation focused on a single dataset with specific characteristics that present unique evaluation challenges that may not represent broader visual narrative contexts (e.g., news photography or social media stories). In contrast, contemporary image collections employ different photographic techniques and narrative conventions, while news photography and social media stories follow domain-specific visual languages that we do not explore. Thus, the historical nature of our dataset, consisting of 1928 photographs, may favor evaluation approaches that perform differently on contemporary images.

In addition, the temporal gap between the photographs in the ROGER dataset and the predominantly modern training data from VLMs could introduce uncertainties that we cannot quantify. While we provide explicit historical context in our evaluation prompts, we cannot determine how differences in photographic techniques, visual conventions, and subject matter could affect the evaluation. Furthermore, the cross-cultural context of the expedition, which documents European explorers in Bolivia, adds cultural complexity that our evaluation design does not address. The English-only evaluation leaves unanswered questions about the narrative cross-linguistic assessment. Moreover, our results reflect the capabilities of GPT-4o, which may not transfer to other VLMs or future architectures. However, we expect that VLMs will improve and become more reliable as the field continues to advance.

We further highlight that the sample size imbalance in our experimental design leads to some statistical limitations: with only 6 human-curated baselines compared to 60 algorithmically generated narratives for each method, our comparisons suffer from possibly not having sufficient statistical power. In particular, the 10:1 sample size ratio could break the underlying assumptions of some parametric tests, affecting our ability to detect true differences. While we report large effect sizes for comparisons against the human baseline (Cohen’s ), these may be overestimated due to the small reference group. The limited availability of expert-curated narratives—a common constraint in digital humanities research—means that our conclusions about human baseline performance should be interpreted cautiously. To mitigate these issues, we report effect sizes alongside p-values, as effect sizes are less sensitive to sample size imbalance (although they may still be overestimated); we also use non-parametric tests where appropriate and focus on consistent patterns across multiple metrics rather than individual significance tests. Future work should expand the collection of human baselines to provide adequate statistical comparisons. Additionally, the small human sample size limits our ability to detect heterogeneity in human curatorial strategies, as six narratives may not fully represent the range of valid narrative constructions possible from the collection.

Regarding our methodological choices, we deliberately kept consistent prompts throughout the experiments to isolate the effect of the evaluation modality. Our previous work has shown that simple prompts achieve 85-90% of the performance of complex prompts in narrative extraction evaluation [4]. While prompt engineering could improve absolute scores, our focus was on comparing caption-based versus direct vision approaches under equivalent conditions. Production deployments would benefit from prompt optimization, but our comparative findings about modality trade-offs should remain valid. Despite these limitations, our primary contribution—establishing a comparative framework between caption-based and direct VLM approaches—provides value for practitioners choosing between evaluation modalities. Finally, we note that both evaluation methods were able to discriminate between the three categories of narratives (human-curated, algorithmically extracted, and random narratives).

5.6. Future Directions

Our work opens some potential research avenues for investigation. For example, future work could explore mixed approaches that combine the strengths of caption-based and direct vision evaluations (e.g., through weighted combinations or meta-learning to optimize the trade-off between reliability and efficiency). Testing on more types of visual narratives (e.g., news sequences, instructional images, or social media stories) could help evaluate whether the results we obtained in this specific domain are generalizable. Furthermore, developing methods to visualize what drives VLM coherence judgments could improve interpretability and trust. Finally, examining how cultural factors influence visual narrative evaluation could inform international applications.

6. Conclusions

This work presents the first systematic comparison of caption-based versus direct vision approaches to evaluate visual narrative coherence. Through experiments on historical photographs, we demonstrate that both methods discriminate between human-curated, algorithmically extracted, and random narratives with distinct trade-offs.

Our findings establish that both approaches achieve similar correlations with average mathematical coherence (), although caption-based evaluation shows slightly weaker correlation with minimum coherence (), suggesting that narrative quality assessment transcends specific modalities. VLM evaluation offers inter-rater reliability with an ICC of 0.718 compared to 0.339 for captions, at the cost of ten times longer processing time, presenting a trade-off for practitioners that could be justified by substantially higher reliability and alignment with human judgment for most research applications, with caption-based approaches reserved for scenarios requiring real-time evaluation or processing at massive scale. Both methods distinguish between narrative qualities, with human narratives scoring higher than Narrative Maps extractions, which score higher than random sequences, all with p-values below 0.001, validating their use as evaluation proxies. The opposite correlations with human baselines suggest that the approaches could capture different aspects of narrative quality.

Our work establishes that current VLMs can facilitate visual narrative assessment for practitioners without technical expertise. Furthermore, these results have practical implications for narrative extraction projects in digital humanities or computational journalism, since VLM-based evaluation could provide an efficient screening tool. Future work could explore hybrid approaches that combine the efficiency of caption-based methods with the reliability of VLM-based evaluation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.K.; methodology, B.K., C.M., and D.U.; software, B.K.; validation, C.M., D.U., M.M., and M.C.C.; formal analysis, C.M., M.M., M.C.C., and D.U.; investigation, B.K., M.M., and M.C.C.; resources, C.M., B.K., and M.M.; data curation, M.M.; writing—original draft preparation, all authors; writing—review and editing, all authors; visualization, B.K.; supervision, C.M.; project administration, C.M.; funding acquisition, C.M. and B.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Agencia Nacional de Investigación y Desarrollo (ANID) FONDEF ID25I10169 and FONDECYT de Iniciación 11250039.

Data Availability Statement

The ROGER dataset is available at the ROGER Concept Narratives repository https://github.com/faustogerman/ROGER-Concept-Narratives (accessed on 15 September 2025).

Acknowledgments

We thank the Robert Gerstmann Archive for providing access to the historical photograph collection. During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used Grammarly and Writefull integrated with Overleaf for the purposes of paraphrasing and improving English writing. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Arnold, T.; Tilton, L. Distant viewing: Analyzing large visual corpora. Digit. Scholarsh. Humanit. 2019, 34, i3–i16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wevers, M.; Vriend, N.; De Bruin, A. What to do with 2,000,000 historical press photos? The challenges and opportunities of applying a scene detection algorithm to a digitised press photo collection. TMG J. Media Hist. 2022, 25, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keith, B.; Mitra, T.; North, C. A survey on event-based news narrative extraction. ACM Comput. Surv. 2023, 55, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keith, B. LLM-as-a-Judge Approaches as Proxies for Mathematical Coherence in Narrative Extraction. Electronics 2025, 14, 2735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- German, F.; Keith, B.; North, C. Narrative Trails: A Method for Coherent Storyline Extraction via Maximum Capacity Path Optimization. In Proceedings of the Text2Story Workshop at ECIR, Lucca, Italy, 10 April 2025; pp. 15–22. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Li, C.; Wu, Q.; Lee, Y.J. Visual instruction tuning. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 36: Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems 2023, NeurIPS 2023, New Orleans, LA, USA, 10–16 December 2024; Volume 36. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, L.; Chiang, W.L.; Sheng, Y.; Zhuang, S.; Wu, Z.; Zhuang, Y.; Lin, Z.; Li, Z.; Li, D.; Xing, E.; et al. Judging LLM-as-a-Judge with MT-Bench and Chatbot Arena. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2023, 36, 46595–46623. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, T.H.; Ferraro, F.; Mostafazadeh, N.; Misra, I.; Agrawal, A.; Devlin, J.; Girshick, R.; He, X.; Kohli, P.; Batra, D.; et al. Visual storytelling. In Proceedings of the 2016 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, San Diego, CA, USA, 12–17 June 2016; pp. 1233–1239. [Google Scholar]

- Matus, M.; Urrutia, D.; Meneses, C.; Keith, B. ROGER: Extracting Narratives Using Large Language Models from Robert Gerstmann’s Historical Photo Archive of the Sacambaya Expedition in 1928. In Proceedings of the Text2Story@ ECIR, Glasgow, Scotland, 24 March 2024; pp. 53–64. [Google Scholar]

- Keith Norambuena, B.F.; Mitra, T. Narrative Maps: An Algorithmic Approach to Represent and Extract Information Narratives. Proc. ACM Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2021, 4, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- German, F.; Keith, B.; Matus, M.; Urrutia, D.; Meneses, C. Semi-Supervised Image-Based Narrative Extraction: A Case Study with Historical Photographic Records. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2501.09884. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, E. Photography and the material performance of the past. History and Theory 2009, 48, 130–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, J.M.; Cook, T. Archives, records, and power: The making of modern memory. Arch. Sci. 2002, 2, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Dong, Q.; Chen, J.; Su, H.; Zhou, Y.; Ai, Q.; Ye, Z.; Liu, Y. LLMs-as-Judges: A Comprehensive Survey on LLM-Based Evaluation Methods. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2412.05579. [Google Scholar]

- Naismith, B.; Mulcaire, P.; Burstein, J. Automated evaluation of written discourse coherence using GPT-4. In Proceedings of the 18th Workshop on Innovative Use of NLP for Building Educational Applications (BEA 2023), Toronto, ON, Canada, 13 July 2023; pp. 394–403. [Google Scholar]

- OpenAI. GPT-4, Technical Report. arXiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Chen, W.; Wang, Y.F.; Wang, W.Y. No metrics are perfect: Adversarial reward learning for visual storytelling. In Proceedings of the 56th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 15–20 July 2018; pp. 899–909. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, J.; Wang, Y.; Huang, Y.; Chen, D.; Zhang, Q.; Moniz, N.; Gao, T.; Geyer, W.; Huang, C.; Chen, P.Y.; et al. Justice or prejudice? Quantifying biases in llm-as-a-judge. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.02736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verga, P.; Hofstatter, S.; Althammer, S.; Su, Y.; Piktus, A.; Arkhangorodsky, A.; Xu, M.; White, N.; Lewis, P. Replacing Judges with Juries: Evaluating LLM Generations with a Panel of Diverse Models. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2404.18796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castricato, L.; Frazier, S.; Balloch, J.; Riedl, M. Fabula Entropy Indexing: Objective Measures of Story Coherence. In Proceedings of the Third Workshop on Narrative Understanding, Virtual, 11 June 2021; pp. 84–94. [Google Scholar]

- Amorim, E.; Campos, R.; Jorge, A.; Mota, P.; Almeida, R. text2story: A python toolkit to extract and visualize story components of narrative text. In Proceedings of the 2024 Joint International Conference on Computational Linguistics, Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC-COLING 2024), Torino, Italy, 20–25 May 2024; pp. 15761–15772. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Tian, X. Consistent prompt learning for vision-language models. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2025, 310, 112974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q.; Zhang, J.; Gockel, J.; Wakin, M.B.; Brice, C.; Zhang, X. QA-VLM: Providing human-interpretable quality assessment for wire-feed laser additive manufacturing parts with Vision Language Models. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2508.16661. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, D.; Chen, R.; Zhang, S.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, Q.; Zhou, P.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y. MLLM-as-a-Judge: Assessing Multimodal LLM-as-a-Judge with Vision-Language Benchmark. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2402.04788. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Z.; Zhang, B.; Li, P.; Ma, X.; Yuan, T.; Fan, Y.; Wu, Y.; Jia, Y.; Zhu, S.C.; Li, Q. Multi-modal agent tuning: Building a vlm-driven agent for efficient tool usage. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2412.15606. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.; Kim, S.; Yoon, S.H.; Kim, G.; Seo, M. Prometheus-Vision: Vision-Language Model as a Judge for Fine-Grained Evaluation. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL 2024, St. Julian’s, Malta, 12–14 August 2024; pp. 672–689. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, M.; Zhang, W. Is your video language model a reliable judge? arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.05977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salaberria, A.; Azkune, G.; de Lacalle, O.L.; Soroa, A.; Agirre, E. Image captioning for effective use of language models in knowledge-based visual question answering. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 212, 118669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groot, T.; Valdenegro-Toro, M. Overconfidence is key: Verbalized uncertainty evaluation in large language and vision-language models. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2405.02917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Du, Y.; Zhou, K.; Wang, J.; Zhao, W.X.; Wen, J.R. Evaluating Object Hallucination in Large Vision-Language Models. In Proceedings of the 2023 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Singapore, 6–10 December 2023; pp. 20–35. [Google Scholar]

- Bechard, P.; Ayala, O. Reducing hallucination in structured outputs via Retrieval-Augmented Generation. In Proceedings of the 2024 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies (Volume 6: Industry Track), Mexico City, Mexico, 16–21 June 2024; pp. 228–238. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.; Park, J.; Lee, M.; Kim, S.; Choi, Y. Evaluating Visual and Cultural Interpretation: The K-Viscuit Benchmark with Human-VLM Collaboration. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2406.16469. [Google Scholar]

- Jolly, S.D. The Treasure Trail; John Long: London, UK, 1934. [Google Scholar]

- Quisbert Condori, P. Entre ingenieros y aventureros. Robert Gerstmann y el tesoro de Sacambaya. In Imágenes de la Revolución Industrial: Robert Gerstmann en las Minas de Bolivia (1925–1936); Plural Editores: La Paz, Bolivia, 2015; Chapter 3; pp. 47–64. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Li, D.; Savarese, S.; Hoi, S. Blip-2: Bootstrapping language-image pre-training with frozen image encoders and large language models. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Honolulu, HI, USA, 23–29 July 2023; pp. 19730–19742. [Google Scholar]

- Zhai, X.; Mustafa, B.; Kolesnikov, A.; Beyer, L. Sigmoid loss for language image pre-training. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Paris, France, 4–6 October 2023; pp. 11975–11986. [Google Scholar]

- Radford, A.; Kim, J.W.; Hallacy, C.; Ramesh, A.; Goh, G.; Agarwal, S.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A.; Mishkin, P.; Clark, J.; et al. Learning transferable visual models from natural language supervision. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Virtual, 18–24 July 2021; pp. 8748–8763. [Google Scholar]

- Apostolico, A. String editing and longest common subsequences. In Handbook of Formal Languages: Volume 2—Linear Modeling: Background and Application; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 361–398. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, S.; Song, Y.; Ma, C.; Yang, X. Iou attack: Towards temporally coherent black-box adversarial attack for visual object tracking. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Virtual, 19–25 June 2021; pp. 6709–6718. [Google Scholar]

- Elhenawy, M.; Ashqar, H.I.; Rakotonirainy, A.; Alhadidi, T.I.; Jaber, A.; Tami, M.A. Vision-language models for autonomous driving: Clip-based dynamic scene understanding. Electronics 2025, 14, 1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayasumana, S.; Ramalingam, S.; Veit, A.; Glasner, D.; Chakrabarti, A.; Kumar, S. Rethinking fid: Towards a better evaluation metric for image generation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 17–21 June 2024; pp. 9307–9315. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, R.; Isola, P.; Efros, A.A.; Shechtman, E.; Wang, O. The unreasonable effectiveness of deep features as a perceptual metric. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018; pp. 586–595. [Google Scholar]

- Dolev, S.; Elovici, Y.; Puzis, R. Routing betweenness centrality. J. ACM 2010, 57, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shou, Z.; Wang, D.; Chang, S.F. Temporal action localization in untrimmed videos via multi-stage cnns. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 1049–1058. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, D.; Xiao, J.; Zhao, Z.; Shao, J.; Xie, D.; Zhuang, Y. Self-supervised spatiotemporal learning via video clip order prediction. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 10334–10343. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).