Abstract

University course scheduling is a kind of timetable problem and can be mathematically formulated as an integer linear programming problem. Essentially, a university course scheduling problem is an optimization problem that aims at most efficiently minimizing a cost function according to a set of constraints. The huge searching space for the course scheduling problem means a long time will be needed to find the optimal solution. Therefore, some studies have used soft computing approaches to solve course scheduling problems in order to reduce the searching space. However, in order to use soft computing approaches to solve university course scheduling problems, we may need to design algorithms and conduct numerous experiments to achieve maximum efficiency. Thus, in this study, instead of employing soft computing methods, we propose a SWI-PROLOG-based expert system to solve the course scheduling problem. An experiment was conducted using real-world data from a department at a national university in southern Taiwan. During the experiment, each teacher in the department chose five preferential time slots. The experimental results have shown that about 99% of courses were scheduled in teachers’ five preferential time slots with an acceptable computational time of executing SWI-PROLOG (127 milliseconds on a regular personal computer). This study has thus provided a framework for solving course scheduling problems using an expert system. This would be the main contribution of this study.

1. Introduction

In school administration, how to schedule courses is an important issue for departmental staff members. From the perspective of operational research, course scheduling problems are timetable problems and could theoretically be solved by optimization methods. Mathematically, a course scheduling problem can be formulated as an integer linear programming problem [1]. In practical terms, course scheduling problems might need to be looked at case-by-case according to different constraints.

The search space for scheduling problems could be huge if these problems are complicated. This could probably mean a long computational time span will be needed in order to find optimal solutions. Therefore, some studies have utilized soft computing methods to decrease the search space and hence to also reduce the computational time. These soft computing methods include genetic algorithms, simulated annealing algorithms, and hybrid particle swarm optimizations. To solve the course scheduling problems with genetic algorithms, we need to define gene/chromosome structures, to formulate fitness functions, and to design the genetic operations (i.e., selections, crossovers, and mutations). Similarly, when using simulated annealing algorithms to solve course scheduling problems, we need to design cooling strategies in order to find better solutions. Using particle swarm optimization methods, solutions might quickly converge, falling into local optimums at an early stage.

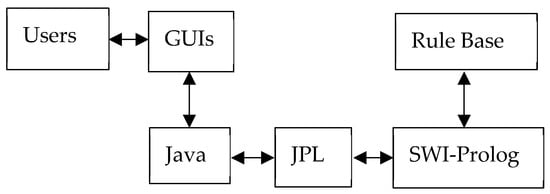

In this study, we are proposing an expert system for solving course scheduling problems based on SWI-PROLOG, an expert system programming language. SWI-PROLOG allows users to build a set of if-then rules and conducts auto-reasoning with its built-in inference engine. However, the user interface for SWI-PROLOG is a command-line-based interface, which is not suitable for modern computer applications. Therefore, to generate graphical user interfaces (GUIs) for this expert system, we use JPL as a bridge to connect SWI-PROLOG and the Java programming language. A real-world case study was also conducted using the proposed expert system, where the data were taken from a department at a national university in southern Taiwan.

2. Preliminary

2.1. Overview of SWI-PROLOG

Expert systems are one of the artificial intelligence approaches. An expert system conducts auto-reasoning according to a predefined rule base. There are three parts in an expert system: a rule base, an inference engine, and user interfaces. A rule base stores a set of “if-then” rules, which are extracted from the domain knowledge of human experts. In building expert systems, knowing how to extract human experts’ domain knowledge and to transfer this knowledge to a set of rules is an important task. Facts in an expert system describe the currently existing conditions (constraints) for this expert system. When performing reasoning, rules are ignited by facts. An inference engine is an auto-reasoning mechanism that finds the inference results according to the rules and facts in this expert system. It is very common to ignite rules recursively until the inference procedure completely stops. The property of recursive ignitions gives expert systems a powerful capacity to solve real-world problems. In an expert system, user interfaces allow users to define rules and facts and to display the reasoning results for this system.

SWI-PROLOG is one of the most popular expert system programming languages, with numerous successful applications in different areas. It is free software and provides online tutoring and user guidebooks on its official website. For SWI-PROLOG-based expert system builders, it is not necessary to implement an inference engine in order to perform reasoning processes since SWI-PROLOG already has a built-in inference engine. The main task in building expert systems is how to design a well-structured rule base to solve real-world problems. The user interface for SWI-PROLOG is a command-line-based console, which is not suitable for modern computer applications. To enhance the user interface, this study has utilized Java to establish the GUIs for better graphical visualizations. Essentially, SWI-PROLOG is an inference-based language with a very powerful auto-reasoning capacity. However, compared with traditional programming languages (e.g., Java, C/C++, C#, and Python), with SWI-PROLOG it is difficult to perform regular flow controls (e.g., for/looping, while/looping, if-else branches, etc.) and regular assignment operations. Many expert system applications are implemented by combining Java and SWI-PROLOG. In such applications, regular data manipulations, flow controls, and GUIs are implemented by Java, while the auto-reasoning is conducted by SWI-PROLOG. Here JPL, a Java archive file, acts a bridge to connect Java and SWI-PROLOG.

2.2. Syntax of SWI-PROLOG

- Facts:

The syntax of facts in SWI-PROLOG is demonstrated as follows:

fact_name(arguments) :- true/false.

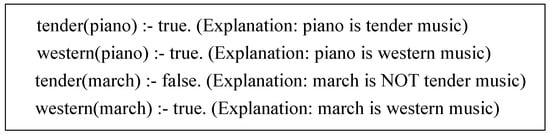

Figure 1 shows examples of facts.

Figure 1.

Examples of facts.

- Rules:

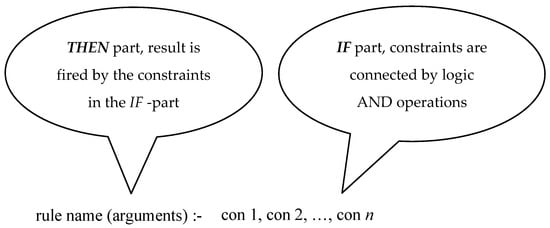

As mentioned earlier, a rule is an “IF-THEN” structured format. Figure 2 shows the structure of a rule in SWI-PROLOG. In this figure, the beginning of the rule is the THEN part, which can be considered as the name of this rule; the end of a rule is the IF part consisting of a set of constraints (con 1, con 2, …, con n). Each constraint is connected by a comma, so we may say that these constraints are composed of logical “AND” operations. The symbol “:-” is a separator between the THEN part and the IF part. As a rule, first-letter-capitalized words represent variables, and all-lowercase words represent symbols. For example, consider the following rule:

prefers(john, Music) :- western(Music), tender(Music).

Figure 2.

The Structure of a rule.

In this rule, john is a symbol and Music is a variable. This rule can be explained by the following sentence:

“If this music is western style and also tender, THEN john prefers this music.”

- Queries:

Queries are used to find the reasoning results according to facts and rules. Normally, a query utilizes a rule name with certain variables. If we send a query to SWI-PROLOG, SWI-PROLOG will return the reasoning results through its console-based user interface. For example, consider the facts shown in Figure 1. If the rule for these facts is defined as:

prefers(john, Music) :- western(Music), tender(Music).

Now we send the following query to SWI-PROLOG:

prefers(john, Music).

The SWI-PROLOG will return

Music = piano.

3. Related Work

Scheduling problems belong to the well-known problem domain of arranging tasks according to a set of limited resources. University course scheduling is one of the most common scheduling problems and can be solved by either operational research methods or artificial intelligence approaches. Naderi has utilized integer linear programming to solve a university course scheduling problem with four dimensions: lecturers, classrooms, courses, and days [1]. In this integer linear programming, preferences were used to measure the performance of the course scheduling problem. The objective function is to maximize these preferences based on a set of constraints for this problem. Wasfy and Aloul have applied advanced integer linear programming to solve a university course scheduling problem and have claimed that the integer linear programming method is suitable for solving reasonably sized course scheduling problems [2].

Wang has suggested general constraints for formulating the course scheduling problems using operational research methods [3]. However, these methods are complicated and probably spend a huge amount of computational time to obtain solutions. To reduce computational time, some studies have utilized soft computing methods to find solutions. Genetic algorithms are one of the most popular soft computing approaches to solve course scheduling problems. For example, Wang has applied a genetic algorithm to solve the course scheduling problem, where a one-dimensional structure was adopted to represent chromosomes, and penalty functions were used to evaluate the performance of the genetic algorithm [3]. Saptarini et al. have presented a distributed genetic algorithm to solve the course scheduling problem for a senior high school [4]. In this distributed genetic algorithm, the chromosomes were encoded by a two-dimensional structure, where the rows represented time slots for teaching and the columns represented classes. Another case study was conducted, where twenty-seven classes, sixty-one teachers, and two time slots (morning and afternoon) were used in this case study [4]. The results of this case study have shown that the use of a distributed genetic algorithm could help us to avoid being stuck in local optima. Moreover, Saptarini et al. have presented a comparative report on course scheduling problems using genetic algorithms where three selection methods were utilized for the comparison: roulette-wheel, tournament, and truncation selections [4]. Of these three selection methods, the truncation method has been suggested as the best one.

In addition, Naderi has reported on a comparative study of scheduling problems where three approaches were compared: an imperialist competitive algorithm, a simulated annealing algorithm, and a variable neighborhood search method [1]. The experimental results have shown that, of the three approaches, the imperialist competitive algorithm had the best performance. Gunawan, Ng, and Poh have proposed a hybrid method to solve the course scheduling problems [5]. This hybrid method combined an integer programming approach, a greedy heuristic, and a modified simulated annealing algorithm. Experimental results have suggested that this hybrid method could solve the problems with large-scale data sets. Wang has presented an improved adaptive genetic algorithm for solving the university course scheduling problems [6]. In this improved adaptive genetic algorithm, the fitness function was formulated according to the weights of class priorities, and the punishments of teachers’ satisfaction were employed as a means of measuring the performance. In [6], experiments have been conducted to validate the performance, where two counterpart algorithms, a traditional genetic algorithm and an adaptive genetic algorithm, were used to compare the performances of the algorithms. The experimental results have shown that the improved adaptive genetic algorithm outperformed both the traditional genetic algorithm and the adaptive genetic algorithm. In addition, Shiau has utilized a hybrid particle swarm optimization to model a course scheduling problem as a discrete optimization problem according to different preferences, where a repairing procedure was adopted to handle unfeasible solutions [7].

PROLOG uses a depth-first search algorithm to find a solution via a backtracking reasoning procedure. The search space for solving PROLOG-based applications might be huge. Thus, some studies have focused on how to enhance the search effectiveness for PROLOG-based applications using different approaches. An early study used “cut” predicators to implement a massively parallel PROLOG-based application, where an OR-parallel mechanism has been used to perform a distributed data-driven PROLOG abstract machine [8]. To reduce PROLOG search spaces, Lu and Liu have presented a best-first search strategy to dynamically generate possible best search paths during an inference process based on accumulated knowledge defined in a knowledge base [9]. Zhang and Hong have proposed a linear reduction model to further improve PROLOG’s search effectiveness by dividing a graphic problem into subproblems and solving these subproblems with AND/OR sub-graphics [10].

PROLOG is a good tool for modeling problems as rule-based knowledge structures and thus solving these problems via its built-in inference mechanism. For example, Chen and Li have used Visual PROLOG to establish the knowledge structure of stratigraphic correlation and connection [11]. Zhou and Dovier have utilized PROLOG to solve Sokoban game problems, where the problem was modeled as a shortest path problem by dividing the original problems into tabled subproblems and solving them via dynamic programming [12]. Countless PROLOG-based expert systems have been developed to solve real-world problems in many fields, such as the problems of silk relic pattern determination [13], design pattern detection in software structures [14], animal classification and diagnosis [15,16], package filtering in firewall design [17], semantic technology for the Internet of Things [18], and web programming [19].

Some early studies have tried to combine PROLOG with some AI approaches to solve more complicated problems. For example, Liya has used PROLOG to build a neural network model where a PROLOG-like knowledge structure and inference mechanism were utilized [20]. Yasui, Hamada, and Mukaidono have proposed fuzzy PROLOG, a model combining fuzzy theory and PROLOG, where fuzzy-like predicates, matching, and inference have been utilized for building expert systems [21]. Munoz-Hernandez and Wiguna have further used fuzzy PROLOG to determine the game strategy in a Robo Soccer game [22]. Medsker and Song have utilized PROLOG to implement a genetic algorithm and given this PROLOG-based genetic algorithm a very powerful reasoning ability [23]. In addition, an adaptive PROLOG programming language has been applied in solving a machine learning problem, where an Upper Confidence Bounds applied to Tree (UCT) has been applied to solve a multi-stage Markov decision process problem [24]. In this UCT, unlike traditional depth-first search in PROLOG, a best-first search strategy has been adopted to improve the searching effectiveness. In addition, PROLOG has been employed to implement a data mining application where a Naïve Bayes algorithm has been implemented with PROLOG, extending the logical reasoning capacity of the Naïve Bayes algorithm [25].

4. System Design

4.1. Structure

The proposed expert system utilizes two programming languages, SWI-PROLOG and Java. Figure 3 demonstrates the conceptual diagram for this system. As indicated in this figure, users interact with the expert system via GUIs, which were implemented by Java. JPL, a Java archive file, serves to connect Java and SWI-PROLOG. Java handles the data manipulations and performs necessary flow controls for the business process of the expert system. SWI-PROLOG conducts reasoning with its built-in inference engine according to the rule base.

Figure 3.

Concept diagram for the proposed expert system.

4.2. Requirements

This study conducted a case study to solve a real-world course scheduling problem. The data were taken from a software engineering and management department at a national university in southern Taiwan. This department has an undergraduate program with four classes (freshmen, sophomores, juniors, and seniors) and two master’s programs (soft engineering and soft management programs). Each of the master’s programs is a two-year program. The requirements of the course scheduling problem for this department are as follows:

- Number of faculty: 11.

- Each teacher normally teaches three courses per semester; in some special situations, a teacher might teach two or four courses.

- Each course is a three-hour successive time slot occupying a single morning or afternoon.

- Fridays are scheduled for educational courses for those students who are preparing to be high school teachers. Therefore, the department does not schedule any courses on Fridays.

- There are eight available time slots for this course scheduling problem, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Time slot encoding.

Table 1. Time slot encoding. - Each teacher gives eight priorities for the eight time slots, respectively, from one (first priority) to eight (last priority); the expert system will arrange the courses for each teacher based on his or her priorities.

- General education courses, physical education courses, and some university-required courses (e.g., Chinese, civil law, and public service courses) are restricted to specially reserved time slots for freshmen and sophomores.

4.3. Rule Bases

4.3.1. Core Concept and Sample Code

We explain the core concept of this study with a simple example. Suppose we need to make a timetable for a department in a university with the following constraints:

Number of classes: 4 (Class 1 to Class 4).

Number of time slots: 5 (Slot 1: Monday morning, Slot 2: Monday afternoon, Slot 3: Tuesday morning, Slot 4: Tuesday afternoon, and Slot 5: Wednesday morning).

Number of teachers: 5 (Teacher 1 to Teacher 5).

Number of courses: 16. For convenience, we use the notation Course M_N to encode these courses, where M is the class number and N is the nth course for Class M. For example, Course 3_4 indicates the fourth course for Class 3. The 16 courses are assigned to the four classes as follows.

- Class 1: Course 1_1, Course 1_2, Course 1_3

- Class 2: Course 2_1, Course 2_2, Course 2_3, Course 2_4, Course 2_5

- Class 3: Course 3_1, Course 3_2, Course 3_3, Course 3_4

- Class 4: Course 4_1, Course 4_2, Course 4_3, Course 4_4

These 16 courses are assigned to the five teachers as follows.

- Teacher 1: Course_1_1, Course_1_2, Course_2_3

- Teacher 2: Course_2_1, Course_2_4, Course_2_5

- Teacher 3: Course_2_2, Course_4_2, Course 4_3

- Teacher 4: Course_3_4, Course_4_1, Course_4_4

- Teacher 5: Course_1_3, Course_3_1, Course_3_2, Course_3_3

One of the possible timetables is shown in Table 2. The main criteria to schedule the timetable are shown as follows.

Table 2.

Possible timetable.

Each row indicates a particular class. Therefore, for each row, no duplicated courses are allowed; that is, for Course M_N, N cannot be duplicated for Class M.

Each column indicates a particular time slot. Therefore, no duplicated teachers are allowed for each column since a teacher cannot teach two or more courses at the same time slot.

One can manually schedule the timetable. However, when the numbers of classes, time slots, teachers, and courses increase, the problem becomes complicated and cannot be easily solved by a human. That is the reason why we use SWI-PROLOG to make timetables for course scheduling.

To make no duplications for each row and column, SWI-PROLOG provides a useful built-in function called “all_different (list)”, which means no duplicated elements are allowed in the list. Consider a list consisting of five elements as follows.

list1 = [e1, e2, e3, e4, e5].

If e1 to e5 are all different, all_different (list1) returns true; otherwise, it returns false.

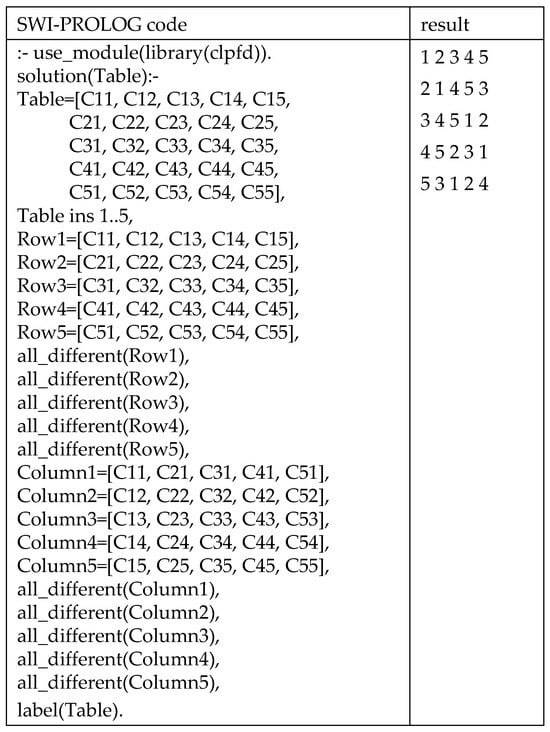

Basically, the timetable problem is somewhat similar to a Sudoku game; that is,

- All cells in each row are different, and

- All cells in each column are different.

Now, consider a 5 × 5 Sudoku table forming 25 cells. The 25 cells are then filled up with five numbers (1 to 5). We provide sample SWI-PROLOG code for solving this Sudoku problem, as shown in Figure 4. In the code shown in this figure, all_different (list) makes the numbers (1 to 5) in each row and each column all different. The sample code is quite simple, straightforward, and easy to design.

Figure 4.

Sample SWI-PROLOG code and the result.

4.3.2. Rule-Based Design

The constraints for designing the course scheduling problem are addressed as follows:

- (i)

- For each of the undergraduate and master’s classes there can be no duplication, i.e., each course for each class can be assigned only once.

- (ii)

- For each of the teachers, he or she cannot teach two courses simultaneously, i.e., no teacher can teach two or more courses in the same time slot.

In this study, we use the all_different function to satisfy the above constraints. For example, to implement the first constraint, consider a collection of courses (C11 to C18) for some class, say Class1, with the following syntax:

Class1 = [C11, C12, C13, C14, C15, C16, C17, C18].

If we send “all_different (Class1)” to SWI-PROLOG as a query, it will return a set of different courses for Class1 if there exist distinct courses for the solution. Similarly, to implement the second constraint, consider a collection of teachers (T1 to T8) for some time slot, say Slot1, with the following syntax:

Slot1 = [T1, T2, T3, T4, T5, T6, T7, T8].

Again, if we send “all_different (Slot1)” to SWI-PROLOG as a query, it will return a set of different teachers for this time slot (Slot1) if no duplicate teachers exist in Slot1, i.e., all teachers in this slot are all different.

As mentioned earlier, we use JPL as an interface to connect Java and SWI-PROLOG. Java sends queries to SWI-PROLOG via JPL. After reasoning, SWI-PROLOG sends back the inference results to Java. These results are encoded with a collection of key-value-paired maps. Java then shows the results for users via GUIs.

SWI-PROLOG uses a backtracking algorithm to find solutions, and sometimes it will spend a large searching space to find them. It is a very useful strategy to use a “cut” operation (symbolized by a “!” notation) to reduce searching space, avoiding unnecessary searching paths. Proper use of cut operations can significantly decrease searching time when performing inference. In this study, a cut operation was utilized at the end of the main rule to reduce the computational time.

5. Experiments and Scalability

5.1. Experiments and Results

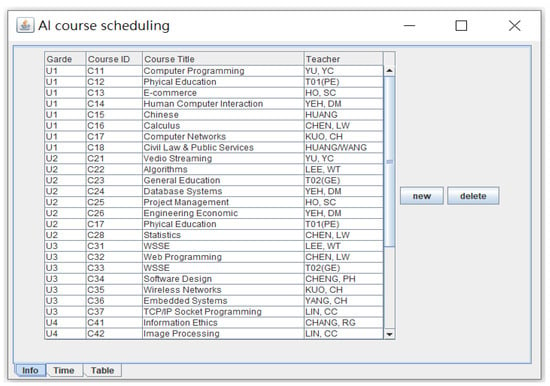

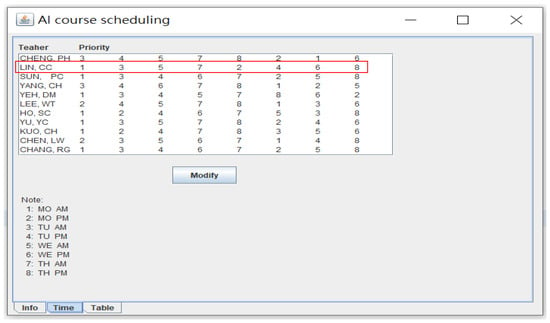

The data for the experiment were taken from a real-world dataset in the spring semester in the software engineering and management department at a national university in southern Taiwan. Figure 5 is the GUI for course management, showing the courses to be scheduled during this semester. In Figure 5, by clicking the “new” button, we can insert a course, and by clicking the “delete” button, we can delete a course. Figure 6 demonstrates the GUI for teachers’ preferred priorities regarding time slots as encoded in Table 1. For example, in Figure 6, the priority list of the preferred time slots for teaching for teacher Lin, CC (marked with a red rectangle for display purposes), is listed as follows:

Figure 5.

GUI for course management.

Figure 6.

GUI showing teachers’ priorities for preferred time slots.

- Priority 1: Time slot 1 (Monday morning).

- Priority 2: Time slot 3 (Tuesday morning)

- Priority 3: Time slot 5 (Wednesday morning)

- Priority 4: Time slot 7 (Thursday morning)

- Priority 5: Time slot 2 (Monday afternoon)

- Priority 6: Time slot 4 (Tuesday afternoon)

- Priority 7: Time slot 6 (Wednesday afternoon)

- Priority 8: Time slot 8 (Thursday afternoon)

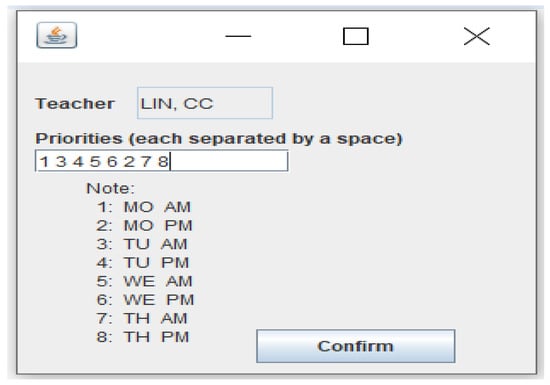

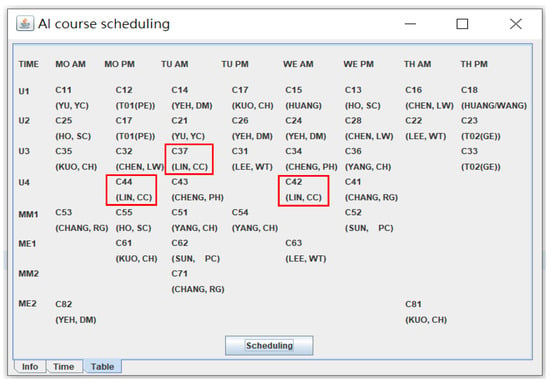

If we want to modify a particular teacher’s priorities regarding his or her preferred time slots, we may simply select this particular teacher and then click the “Modify” button in Figure 6. After doing this, the system will show the GUI in Figure 7 for modifying the priorities of the preferred time slots for this selected teacher (in this case, Teacher Lin, CC). Finally, the scheduling results for the department are shown in Figure 8. For example, in Figure 8 the time slots (marked with red rectangles) for Lin, CC are Monday afternoon (Priority 5), Tuesday morning (Priority 2), and Wednesday morning (Priority 3). All of his time slots are included in the first five priorities on his priority list.

Figure 7.

GUI for modifying priorities for preferred time slots.

Figure 8.

Course scheduling results.

The environment settings for the four experiments are shown as follows.

- Computer:

- CPU: Intel (R) Core (TM) i7-10700 CPU@2.90 GHz 2.90 GHz

- Memory: 64 GB

- OS: Windows 10 Professional, 64 bits

- SWI-PROLOG: SWI-PROLOG version 7.6.2, 64 bits

- Java: Java SE-1.8

- JPL: JPL7

We repeated the course scheduling process 30 times by randomly assigning teachers’ priorities regarding preferred time slots. The random numbers were generated by Java’s Random object with the no-argument constructor, where the random seed was the current system time in nanoseconds. The results are shown in Table 3. The average computational time of executing SWI-PROLOG for the 30 runs is 127 milliseconds. The percentage of teachers’ preferred time slots in their first five priorities is 99%. This is a very satisfactory result for the teachers, since almost all time slots generated by the proposed system are in their first five priorities.

Table 3.

Experimental results.

5.2. Scalability

We performed four experiments to validate the scalability of the proposed system according to different parameters such as numbers of classes, teachers, and courses. The number of time slots for the experiments is 10. In the experiments, we did not use GUIs of the proposed system. Instead, we used simple Java code necessary to control the process of the experiments. In addition, we assumed that each teacher was assigned three courses, which were randomly selected from the course pools. Each experiment was repeated 30 times. The CPU time was calculated by taking the averaged value of the 30 runs. All of the four experiments were successfully implemented; that is, all of the timetables for the four experiments were successfully generated. The results of the four experiments are summarized in Table 4. Through the four experiments, the scalability of the proposed timetable scheduling system is validated.

Table 4.

Results of scalability experiments.

6. Discussion

In this section, we discuss some practical issues related to this study and compare the features of existing constraint logic programming schemas with SWI-PROLOG.

6.1. Maintainability of Rule Bases

As mentioned earlier, the syntax of SWI-PROLOG is well-structured. It is easy to maintain rules to fit changes of constraints. For example, consider a rule consisting of three constraints (con 1, con 2, and con 3) as follows:

where args is the argument list for this rule. If one wants to add two more constraints (i.e., con 4 and con 5) into this rule, it can be simply modified as follows:

rule(args) :- con 1, con 2, con 3.

rule(args) :- con 1, con 2, con 3, con 4, con 5.

Furthermore, a rule can contain several rules as its sub-rules. It is easy to insert or to delete sub-rules in the original rule whenever necessary. For example, consider the following rule containing three sub-rules.

main_rule(args) :- sub_rule1(args), sub_rule2(args), sub_rule3(args).

If one wants to remove sub_rule2 from main_rule, it is simply modified as follows:

main_rule(args) :- sub_rule1(args), sub_rule3(args).

Similarly, if one wants to add one more sub-rule (sub_rule4) into main_rule, it is simply modified as follows:

main_rule(args) :- sub_rule1(args), sub_rule2(args), sub_rule3(args), sub_rule4(args).

For the problem domain of our study, it is very simple to add more constraints in our study. For example, suppose we originally have two rules for class assignment and time slot assignment (i.e., rule_class and rule_slot) for our timetable problem as follows:

main_rule(args) :- rule_class(args), rule_slot(args).

If we want to add more constraints related to room assignment, we first generate a new rule for these room constraints as follows:

rule_room :- room_con_1, room_con_2, … , room_con_n.

Then we add rule_room into main_rule as follows:

main_rule(args) :- rule_class(args), rule_slot(args), rule_room(args).

Now the timetable problem is implemented by considering three assignments: class, time slot, and room.

Summarily, the rule structure for SWI-PROLOG is well-organized. It is easy to design well-structured and easy to maintain rule bases.

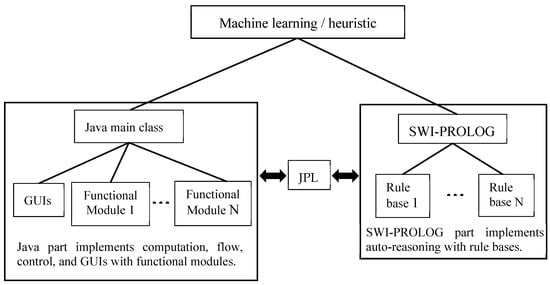

6.2. Interoperability Among SWI-PROLPG, Java, and Machine Learning/Heuristic Methods

The advantage of SWI-PROLOG is its powerful reasoning ability. However, the computation and flow control ability (i.e., while/for loop, if-else statements, etc.) of SWI-PROLOG is very weak. If we want to do both computation/flow control and reasoning, the best way is to use a traditional programming language and SWI-PROLOG at the same time. Fortunately, SWI-PROLOG provides an interface (i.e., JPL) to connect Java and SWI-PROLOG. Furthermore, SWI-PROLOG can be combined with machine learning/heuristic methods to establish a constraint-based machine learning system, where the knowledge obtained from machine learning/heuristic methods can be organized as rules for SWI-PROLOG. Figure 9 demonstrates a conceptual diagram for the interoperability among Java, SWI-PROLOG, and machine learning/heuristic methods.

Figure 9.

Conceptual diagram for the interoperation among Java, SWI-PROLOG, and machine learning.

6.3. Suggestions for SWI-PROLOG Programming

Traditional programming focuses on “how to design good algorithms” to solve problems with general-purpose programming languages such as Java, C/C++, C#, etc. On the other hand, SWI-PROLOG programming focuses on “how to design well-structured rules” to solve problems. This might be the main difference between traditional programming and SWI-PROLOG programming. Moreover, the sequence order of rules might actually affect the searching efficiency for SWI-PROLOG. Therefore, how to optimize the sequence order of rules to enhance searching efficiency is a good issue for SWI-PROLOG programming. Three steps are suggested for developing SWI-PROLOG-based applications as follows.

- Step 1: Focus on the knowledge structure of problem solving, including constraints, criteria, and the relationships among these constraints and criteria.

- Step 2: Transfer the knowledge structure into well-organized and easy to maintain rule bases.

- Step 3: Optimize the sequence order of rules, if necessary.

6.4. Comparison of Existing Constraint Logical Programming Schemas

We concisely compare the features of existing constraint logical programming schemas as follows.

Visual PROLOG (https://www.visual-prolog.com/features.htm. accessed on 12 October 2025)

- Commercial product.

- Fully object-oriented.

- Providing a friendly integrated development environment (IDE).

- Direct linkage with C/C++.

- Easy to develop GUI-based applications.

GNU PROLOG: (http://www.gprolog.org/#whatis. accessed on 12 October 2025)

- Free software.

- Bidirectional interface between PROLOG and C.

- More than 300 built-in predicates.

- Compatible with ISO standards of PROLOG.

- Providing a low-level Warren Abstract Machine (WAM) debugger.

SWI-PROLOG (https://www.swi-prolog.org/features.html. accessed on 12 October 2025)

- Free software.

- Small size: The kernel is about 1.6 MB (Ubuntu 22.04.so fil)

- Large scale: No limits on program size, atom length, term arity, etc.

- Use of UNICODE: Suitable for web and international applications.

- Multiple-threading and multiple core environment running on concurrent applications.

7. Conclusions

University course scheduling is a kind of timetable problem and mathematically can be formulated as an integer linear programming problem. Essentially, a university course scheduling problem is an optimization problem of minimizing a cost function. Solving university scheduling problems using operational research approaches might be time-consuming. Therefore, people use soft computing approaches to solve these problems. These soft computing approaches include genetic algorithms, simulated annealing methods, and particle swarm optimizations. To use genetic algorithms to solve university course scheduling problems, we need to first define chromosome structures, design the evolutionary strategies (crossover, selection, and mutations), and conduct numerous experiments to tune the performance. Using simulated annealing methods to solve university course scheduling problems also involves designing cooling strategies with different parameters. To obtain better results, using simulated annealing methods still means conducting numerous experiments and trying different values of parameters. Using particle swarm optimizations to solve university course scheduling problems might, however, cause us to become stuck in local optima due to the early convergence of iterations.

In this study, instead of using operational research approaches and soft computing methods, we proposed an SWI-PROLOG-based expert system to solve university course scheduling problems with a rule base. We focused on what the patterns (rules) needed to solve the university course schedule problems are, instead of implementing algorithms to solve these problems. The design of the rule base used to implement the problems is concise and straightforward, using some SWI-PROLOG built-in functions. Using SWI-PROLOG to implement the university course scheduling problems is easy to design and easy to maintain. The proposed system used Java to build GUIs and to perform some necessary logical and mathematical operations. JPL was employed as a bridge to connect SWI-PROLOG and Java. A real-world case study was also conducted where the experimental data were taken from a department at a national university in southern Taiwan. The experimental results have shown that the course scheduling problem for this department could be implemented within an acceptable computational time span, and the results were satisfactory. This study has provided a framework for solving university course scheduling problems using an SWI-PROLOG-based expert system according to a rule base. This would be the main contribution of this study.

The directions for possible future studies could be addressed as follows.

- Implementing course scheduling problems with more complicated cases.

- Reducing the computational time by optimizing the structure of the rule base.

- Comparing our SWI-PROLOG-based expert system with other heuristic methods such as particle swarm optimization (PSO), ant colony optimization (ACO), genetic algorithms (GAs), etc. Furthermore, combining our expert system with machine learning might also be a good topic for our future study.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.-C.L.; methodology, W.-Y.L. and C.-C.L.; software, W.-Y.L.; analysis, W.-Y.L. and C.-C.L.; writing, C.-C.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Naderi, B. Modeling and scheduling university course timetabling problems. Int. J. Res. Ind. Eng. 2016, 5, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Wasfy, A.; Aloul, F.A. Solving the University Class Scheduling Problem Using Advanced ILP Techniques. ResearchGate. 2007. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228634502_Solving_the_University_Class_Scheduling_Problem_Using_Advanced_ILP_Techniques (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Wang, Y.-Z. Using genetic algorithm methods to solve course scheduling problems. Expert Syst. Appl. 2003, 25, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saptarini, N.G.A.P.H.; Ciptayani, P.I.; Wisswani, N.W.; Suasnawa, I.W.; Indrayana, N.E. Comparing selection method in course scheduling using genetic algorithm. In Atlantis Highlights in Engineering/International Conference on Science and Technology (ICST 2018); Atlantis Press: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2018; Volume 1, pp. 574–578. [Google Scholar]

- Gunawan, A.; Ng, K.M.; Poh, K.L. Solving the teacher assignment-course scheduling problem by a hybrid algorithm. Int. Sch. Sci. Res. Innov. 2007, 1, 461–496. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.-J. Improved adaptive genetic algorithm for course scheduling in colleges and universities. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Learn. 2018, 13, 29–42. [Google Scholar]

- Shiau, D.-F. A hybrid particle swarm optimization for a university course scheduling problem with flexible preferences. Expert Syst. Appl. 2011, 38, 235–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kacsuk, P. Cut implementation in a massively parallel Prolog system. In Proceedings of the Euromicro Workshop on Parallel and Distributed Processing, Gran Canaria, Spain, 27–29 January 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, B.; Liu, Z. Prolog with best first search. In Proceedings of the 25th Chinese Control and Decision Conference (CCDC), Guiyang, China, 25–27 May 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.; Hong, S. A linear reduction model for parallel Prolog system. In Proceedings of the IEEE 4th International Conference on Cloud Computing and Big Data Analysis (ICCCBDA), Chengdu, China, 12–15 April 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Li, W. Application of visual prolog on stratigraphic correlation and connection. In Proceedings of the 2011 International Conference on Computer Science and Network Technology, Harbin, China, 24–26 December 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, N.; Dovier, A. A tabled Prolog program for solving Sokoban. In Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE 23rd International Conference on Tools with Artificial Intelligence, Boca Raton, FL, USA, 7–9 November 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Fan, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, S. Development of the silk relics expert system based on SWI-Prolog. In Proceedings of the 2015 Chinese Automation Congress (CAC), Wuhan, China, 27–29 November 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Stoianov, A.; Şora, I. Detecting patterns and antipatterns in software using Prolog rules. In Proceedings of the 2010 International Joint Conference on Computational Cybernetics and Technical Informatics, Timisoara, Romania, 27–29 May 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Babu, S.; Archana; Vineeth; Veena. Koyal—A multi-purpose expert system—MD-CoB-CoA knowledge representation using PROLOG in J2SE. In Proceedings of the 2011 3rd International Conference on Electronics Computer Technology, Kanyakumari, India, 8–10 April 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Pratama, R.; Wahyudi, R.; Marcos, H.; Budiati, I.; Khasanah, L.N.; Jaya, F.I.; Wijaya, F.P. Expert system for diagnosing vertebrate animals with Visual Prolog 8.0. In Proceedings of the 2018 3rd International Conference on Information Technology, Information System and Electrical Engineering (ICITISEE), Yogyakarta, Indonesia, 13–14 November 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Yu-gang, W.; Yin-mao, G.; Jian-xin, Y. Research on packet filter rules of the firewall based on Visual Prolog. In Proceedings of the 2008 International Conference on Computer Science and Software Engineering, Wuhan, China, 12–14 December 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Geng, D.; Gao, Q. Semantic web technology and prolog reasoning based task planning mechanism and application in smart home for Internet of Things. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 9th International Conference on Electronics Information and Emergency Communication (ICEIEC), Beijing, China, 12–14 July 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Szklarczyk, R. GNU Prolog-PHP multi-tier integration. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE 7th International Conference on Intelligent Data Acquisition and Advanced Computing Systems (IDAACS), Berlin, Germany, 12–14 September 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Liya, D. Neural Prolog-the concepts, construction and mechanism. In Proceedings of the 1995 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man and Cybernetics. Intelligent Systems for the 21st Century, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 22–25 October 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Yasui, H.; Hamada, Y.; Mukaidono, M. Fuzzy Prolog based on Lukasiewicz implication and bounded product. In Proceedings of the 1995 IEEE International Conference on Fuzzy Systems, Yokohama, Japan, 20–24 March 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Munoz-Hernandez, S.; Wiguna, W.S. Fuzzy Prolog as cognitive layer in RoboCupSoccer. In Proceedings of the 2007 IEEE Symposium on Computational Intelligence and Games, Honolulu, HI, USA, 1–5 April 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Medsker, C.; Song, I.Y. ProloGA: A Prolog implementation of a genetic algorithm. In Proceedings of the 1993 IEEE International Conference on Developing and Managing Intelligent System Projects, Washington, DC, USA, 29–31 March 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, B.; Liu, Z.; Gao, H. An adaptive prolog programming language with machine learning. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE 2nd International Conference on Cloud Computing and Intelligence Systems, Hangzhou, China, 30 October–1 November 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Malov, A.; Rodionov, S.; Kholod, I. The realization of Naive Bayes algorithm in the logic programming framework PROLOG. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE NW Russia Young Researchers in Electrical and Electronic Engineering Conference (EIConRusNW), Saint Petersburg, Russia, 2–3 February 2016. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).