Abstract

This paper applied an adapted design sprint approach, called a design summit, to educational prototyping. Design sprints provide a structure for applying design thinking and capturing user requirements that can be adapted to the needs of varied design contexts. However, finding a format that meets project requirements and brings in diverse stakeholders while also considering their availability can be difficult to construct using a traditional design sprint approach. Through four adapted stages of understanding, defining, iterating and prototyping towards a problem space, this paper presents a case study of a design summit applied to education/instructional design, specifically towards the problem of designing teacher professional development on the topic of the high ability (HA) student. A key feature in our applied approach is using concurrent prototyping, over many months, to achieve project outcomes. The case study presents the process and challenges of developing educational resources suited to the professional development of teachers and school leaders that need to support HA students. Through iteration, the results show how diverse stakeholders engaged and provided feedback to inform prototyping outcomes. Our design summit case study demonstrates how careful planning, focused elicitation of user requirements and an elongated and concurrent prototyping process results in outcomes that meet education stakeholder expectations and align with project requirements.

1. Introduction

Design thinking has gained prominence in recent years as a way of incorporating human/user requirements into the product/prototyping process [1,2]. Design thinking invites problem solving using a variety of techniques, often visual [3], to engage experts and end users in exploring a problem space and proposing solutions. Design thinking originated from Stanford University in the early 2000s, with the D School now utilizing design thinking in a variety of contexts, from technical prototyping development or opportunities to apply design thinking to ‘design your life’ [4]. Design thinking broadly encompasses five stages where a group of experts and end users will come together to: empathize, define, ideate, prototype and test. As a broad model, design thinking can be incorporated into a variety of situations and timeframes, guiding project groups towards the common goal of incorporating human needs throughout the process, increasing the likelihood of project success. Along with design thinking, design sprints have also become mainstream to rapidly prototype ideas and to promote radical thinking to better solve complex problems [5]. Design sprints originated from Google Ventures as a way for software developers to better connect with their user group in a time sensitive fashion [1]. Jake Knapp, John Zeratsky and Braden Kowitz describe design sprints as a way to bring together small teams to solve big problems and test new ideas in five days, through the phases of design, prototyping and testing [6]. Wangsa et al. [7] describe problem solving and a user centered approach to be the commonalities between design thinking and a design sprint. Both design thinking and design sprints engage internal and external stakeholders [8], with stakeholder involvement dependent on the project and resources available. Stakeholders form important aspects of the design process, bringing interest and an informed approach to defining project needs and validating outcomes [8].

Design sprints incorporate a component of prototyping, with varying degrees of prototyping quality and type [9] employed. Lauff et al. [10] defined 17 strategies for using prototypes to engage stakeholders, particularly during the early stages of design, to enhance designers’ ability to gather feedback, define problems, and iterate solutions effectively. Prototyping can also encourage iterative design and rapid visualization to improve idea communication [11]. Beyond a design sprint, project/product management approaches for prototyping, such as agile/iterative techniques, are often employed [12] to extend design ideas into systems. Design sprints have already been utilized in a variety of contexts [13] with disciplines like engineering design often demonstrating practice [8]. Wangsa et al. [7] identify time and team member composition as critical aspects of differentiation between design thinking, design sprints and agile approaches. To better suit the needs of education, the design sprint process must be adapted to accommodate the needs of educational stakeholders, to ensure they are available to participate, and to evaluate prototype outcomes in context. To demonstrate the application of an adapted design sprint this paper describes our design summit approach and demonstrates how this approach can be utilized in educational prototyping through a case study.

Our design summit as described in this paper brings together a variety of stakeholders to engage in stages of understanding, defining, iterating and prototyping towards a problem space in education/instructional design. A key feature of our design summit is the period of ‘focused’ activity where stakeholders participate in concerted and concentrated design efforts in half a day, rather than over many days like a design sprint [5]. This focused action provides a transfer of ideas between those involved [9], while also being mindful of stakeholders’ time. As a part of the design summit, focused action is then followed by an extended prototyping period (over three to six months) with concurrent prototyping and incremental validation and evaluation processes to protype a high-fidelity solution that is confirmed by education experts in context.

2. Literature Review: Adapting Design Sprints

A design sprint can be considered as design thinking applied to digital design, with agile project management processes incorporated [14]. These sprints generally ask a working party of domain experts and end users or stakeholders to provide focused efforts to: determine goals, produce a formal problem statement, conduct investigations to better understand the problem, sketch alternative solutions, make difficult decisions regarding the solution to test, build a realistic prototype and evaluate the prototype with the group [5]. Design sprints often occur over several days, asking stakeholders to engage exclusively in the entire ideation and prototyping process. However, a design sprint can be adapted for context [15], connect multidisciplinary teams [16] and come in a variety of formats [17]. A common denominator across recorded case studies describing design sprints in practice is the need to adapt the individual activities [13]; both to adjust to the time available for participants but also to accommodate the diversity of team composition [2]. Engaging a diverse set of users in problem-solving requires a concerted and time-focused approach, bringing together experts/stakeholders from a variety of domains to contribute to the problem space. Design sprints embody agile philosophy and are well suited to these variations with individual stages focused on working through processes associated with design thinking. A design sprint will attempt to test a realistic prototype of the selected solution with the project team, with varying degrees of prototype fidelity presented. Prototype fidelity in a design sprint can vary from low to high fidelity, depending on the project and resources available [6,18].

Bongiovanni et al. [3] report that the focus of a design sprint in certain contexts may focus on product/service, process, strategy or system levels of product iteration. The output from a design sprint does not need to be a technical solution, with Jake-Schoffman et al. [14] demonstrating the use of prototyping in a design sprint to enhance the process of providing behavioral medicine practice. Outcomes from a design sprint are not necessarily products either as sprint outcomes can focus on strategies relevant in the target domain. Design sprints have been variously applied to the development of educational material [18] and with educationalists as designers [19] that prototype content suits context. These benefit from an iterative prototyping approach that is subject to critical decisions from domain experts. Further, teachers are now themselves regularly engaged in the design sprint process in their classrooms [20]. However, as Kirschner [18] argues, asking primary and secondary school teachers to be designers is not always feasible nor desirable particularly if those involved in design require the skills associated with a teaching-technology specialist. Rather a broader view of embracing design cycles as a part of general teacher competencies requires asking for a variety of domain experts to contribute to the design process to determine effective classroom implementation. As a profession, teachers regularly engage in inquiry cycles that see them prototype, evaluate and test ideas in the classroom, often using crude prototyping techniques [21]. Prototyping strategies can all take a different amount of time to complete, and that time will vary based on the fidelity of the product and the feedback received through iteration [22]. Opportunities to explore prototyping outcomes that extend to high-fidelity prototypes and implementable products is required in a design sprint, with extended and concurrent prototyping suitable to provide an informed build and test feedback cycle.

Concurrent Prototyping

Various prototyping strategies exist to support product development [22,23,24], with Rodriguez-Calero et al. [22] (2020) defining 17 strategies just for the early design prototyping. Although prototyping of often associated with later stages of development (validation and testing) in early design, prototypes play a crucial role particularly in front-end design [25] with low-fidelity prototypes fostering a sense of progress while strengthening creative confidence to iterate on ideas [11]. They build confidence in designs, facilitate negotiations, understand stakeholder needs, define problems accurately and clarify design intentions [8]. Expert designers use prototypes dynamically throughout the design process [7] as prototypes help to reframe failure as a learning opportunity, reducing fear and increasing motivation [11]. Hansen and Özkil [13] discuss how prototyping can engage across parallel concepts to help explore the problem space, with the implementation of concurrent prototyping highlighting how the feedback loop received from regular stakeholder feedback (through iteration) informs the product development process and results in outcomes that better suit project feasibility [23]. The agile manifesto, particularly the SCRUM approach, defines iteration at a granular level yet also provides flexibility in adapting to project requirements using the practices of concurrent prototyping [12]. Prototypes are tools for communication and are used by a project/design to team as encoded communication tools, translating information between different stakeholders during different stages of the design process (early to late) [8]. Lauff et al. [10] argue that effective use of prototypes can shape organizational strategies and product development outcomes.

As a part of the design summit, concurrent prototyping can be deployed. Concurrent prototyping provides the opportunity to develop multiple artifacts that can be prototyped towards the defined problem space, removing redundancy or dependencies on any single element. The prototype quantity and quality differ from the typical proof-of-concept used in a concurrent product design sprint as more time is available to both iterate and finalize prototyping outcomes [5,22,23,24], resulting in outcomes that are available for pilot implementation. While concurrent prototyping remains strongly associated with the design summit process and intentions, the project team can determine the length of time to commit to prototyping outcomes and the fidelity of the prototype achieved. Further, contextual and iterative prototyping approaches enable the project team to meet design requirements in the real-world context [9]. Achievement of a minimum viable product can be achieved through longer periods of prototyping and regular feedback from both the project team and design summit stakeholders [2].

This paper puts forward the use of a design summit to explore the application of a design sprint for educational prototyping, and as another way to engage diverse users to iterate design ideas. A design summit differs from a design sprint in terms of the timing of activities and the way in which stakeholders engage throughout the process. A variety of stakeholders are asked to contribute throughout the design process [19] rather than only experts from a certain domain. Unlike the design sprint where all participants are assembled for a period of concentrated and coordinated effort [5], availability constraints on the participants require that a design summit be conducted over an extended period. A design summit takes into consideration the nuances of time and team members that are available for each individual stage, considering their involvement not just in a condensed period of understanding and ideation, but also during prototyping. The summit defines key moments for coordination and transfer of ideas between groups that carefully consider the availability of all stakeholders [2]. Key points of distinction between a design sprint and the design summit applied in this paper include an intensive and structured session conducted over a short period in one day with many experts involving progressive decomposition of stakeholders and project teams. This session is then followed by an extended prototyping period (over three to six months) with concurrent prototyping and incremental validation and evaluation processes [26] to extend prototyping outcomes towards a solution via implementation. The use of a design summit for educational prototyping is presented as a case study in this paper by describing the outcomes from a design summit engaged to help build a professional development/course design for primary and secondary school teachers, and school leaders, in Australia.

3. Context of Educational Prototyping

Educational prototyping occurred when a teacher professional development program on supporting students with HA was initiated by the government education body. The project team from an Australian university needed to design a professional development program to engage teachers and school leaders from both the primary and secondary school level and to create course material for this specialized education area. The core team of education and IT specialists were supported by a tender grant to develop and deliver the course in consultation with additional stakeholders: the staff of an organization dedicated to enhancing HA resources in schools, existing specialist teachers and school leaders who were already providing this support, and teachers in schools and school leaders who would be providing this support in future once they had completed the planned course. The government body that commissioned this work asked that the professional learning course for participants consist of one-and-a-half days of professional development activities and supplementary online materials. Components of the course were expected to be technical solutions that help stimulate the classroom experience of a teacher engaging with HA students. While the theoretical aspects of the course design were informed by our review of literature in this area [27], consideration was needed for how participants could best be supported to apply the theory in practice over a short period of time.

4. Methods

We utilized a case study approach to explore research outcomes [5] from investigating the application of a design summit to educational prototyping. To understand what was needed in a teacher professional development course on HA, we needed to hear from teachers in the primary, secondary and leader context. Using multiple sources of information [5], we evaluated the outcomes of our educational prototyping through two examples (presented in Section 5). We drew data from our design summit process using observations, expert feedback and a post-summit survey to develop our case study outcomes. Additionally, we engaged expert stakeholders to assist with the concurrent product iteration. Our design summit started in January of 2022.

4.1. Design Summit Process

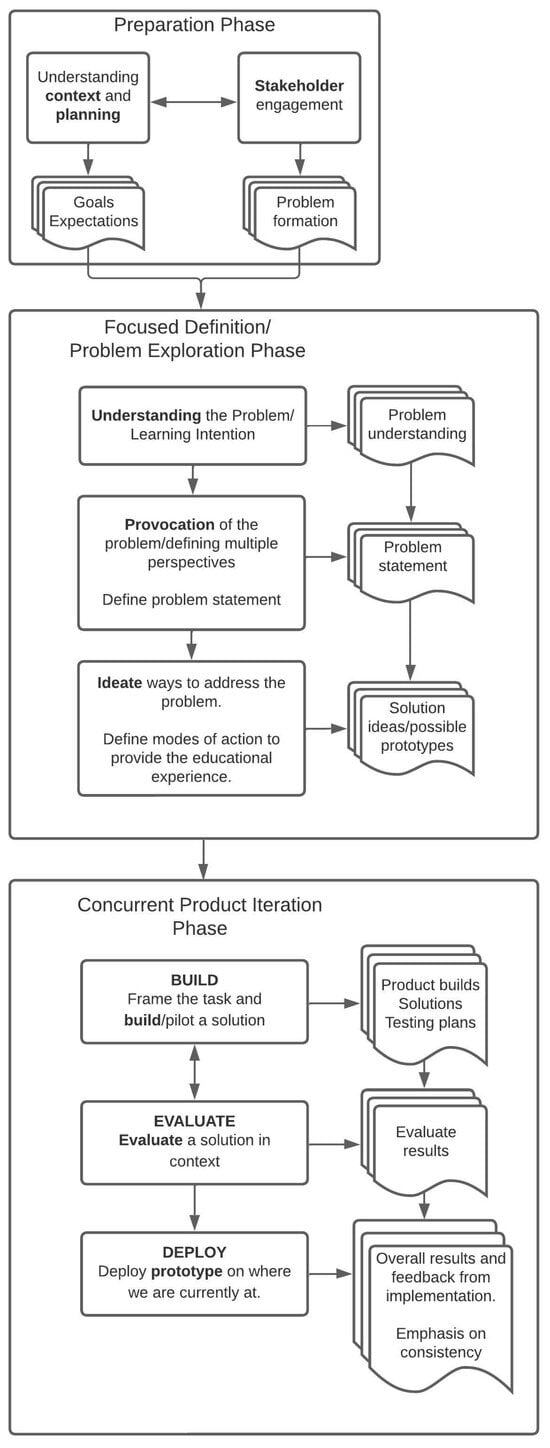

Cooperrider [4] describe their Appreciative Inquiry Summit as a model for ‘next level’ design thinking. They argue for the need for the “whole system in the room” when collaborating towards a problem solution. The design summit method utilized for educational prototyping takes forward this intent. Figure 1 summarizes the design summit process through three phases, along with indicating that groups of stakeholders are included at each stage through the Figures represented. A period of ‘focused action’ engages diverse stakeholders (project team, experts and end users) through pre-prepared content and activities to enable in-depth exploration of a problem domain, resulting in a problem statement to guide action. The problem domain, along with ideation of possible solutions, enables stakeholders to contribute to the co-design process and select the best possible products/solutions that address the project’s motivations, and align with the target user group. This enables the project team to prototype and iteratively verify and refine outcomes using expert and end user feedback.

Figure 1.

Overview of design summit phases.

Table 1 describes in detail the components or tasks in each phase of a design summit. In a design summit, a preparation phase starts the process by asking the team involved to engage in detailed planning for the design summit. Planning can take many months depending on the project requirements and team members involved. Preparation requires the team to have a thorough understanding of the problem domain in which stakeholders will be brought together. In addition, stakeholder engagement is an important preparation task, with project team members and experts identified for their contribution to the focused definition phase of the design summit. Preparation is crucial in ensuring that diverse stakeholder engagement is achieved throughout the periods where each stakeholder is available. Table 2 lists the categories of stakeholders that are employed in a design summit process, with our case study elaborating on how stakeholders engaged in educational prototyping.

Table 1.

Phases and tasks in a design summit.

Table 2.

Stakeholders in a design summit.

4.2. Stakeholders/Experts in a Design Summit

Stakeholders include those beyond the project team with experts across domains contributing towards problem formation and understanding of the context, particularly through the focused-action and concurrent product iteration stages (Table 1). Rodriguez-Calero et al. [22] describe stakeholders as end-users, regulatory bodies, business partners, and internal teams. In a design summit stakeholders visualize concepts, provide feedback, and refine requirements, and engage in a design summit through a variety of roles (Table 2). Stakeholders are required to have a vision for the problem being explored, have domain knowledge and experience, as well as an agile mindset to rapidly yet critically explore the problem space. Stakeholders are invited to participate in a design summit due to their diverse mindset, leadership in the subject domain, or design thinking mindset. It is important to obtain a range of sufficient expertise in a design summit, including those with long-term and more recent expertise to allow disparate viewpoints to be heard and identify a consensus towards prototyping [8]. In a design summit a diverse set of stakeholders are engaged as we do not assume a single expert in one area represents the consensus view for that area.

5. Case Study: Design Summit on Supporting High Ability (HA) Learners

As evidence to support the use of a design summit for educational prototyping, the following describes our case study from implementing our design summit approach to build a professional development course for primary, secondary school teachers and school leaders in Australia. Through a presentation of each stage of a design summit, we will present the results of our study that explore how an adapted design sprint can be utilized for educational prototyping. The preparation occurred from January to May of 2022, the focused definition/problem exploration phase occurred in May, and concurrent prototyping was enacted from June to November 2022. Our three broad phases and their associated processes and outcomes are described, to relate our design summit approach to the course development context.

5.1. Preparation Phase

The preparation phase of the design summit started with a goal: to create a professional learning course using Hyflex activities that would equip teachers and school leaders to support HA students in their individual schools. Further, the goal of the preparation phase is to prepare for focused action that could result in ideation across diverse outcomes. Table 3 list the stakeholders involved in our design summit preparation phase.

Table 3.

Preparation phase stakeholders.

The team needed to identify ways to collect insights into the current practices and perceived needs of the teachers and school leaders located in the Australian state that would host the professional learning. Design thinking advocates for a variety of activities to support the elaboration process [3]. Understanding current practice was critical to lead into initial problem formation; that being how to support high-ability students in the classroom. The project team members reviewed the context via literature, past research and course development and through their own professional experiences in schools, and engagement with stakeholders.

The preparation phase also needed to identify, recruit and schedule a significant number of experts (clients, evaluators and experts: practitioners, specialist and end-users) to participate in a phase of focused action/problem exploration, while also identifying the activities that they would undertake during this phase to elicit the relevant information [18]. A diverse set of current teachers (expert end-users) were asked to provide their time to contribute to the design summit. Over 40 experts were invited with 25 available to attend a period of focused action for the design summit. Experts were invited from widely distributed geographical locations across the state of Victoria, in Australia, with a variety of experience (2 years in the profession, to over 20 years). The broad range of expert teaching practitioners ensured that the design summit outcomes accurately represent the issues facing teachers in the support of students with HA and capture the wide range of needs from across different schools and circumstances.

As a part of the preparation phase, interactive activities were designed by the preparation phase stakeholders to provoke and elicit discussion during the focused definition/problem exploration phase from the invited experts. We planned for group icebreaker activities provided through an online bingo game with a custom designed card to initiate discussion on topics relevant to defining the goal and understanding the problem. We also planned for breakout sessions with a collaborative pinup board (https://pinup.com/ accessed on 30 January 2023) to respond to provocative ideas and practices identified in an earlier literature review. These were interleaved with polls to monitor consensus across all stakeholders. Padlet boards (https://padlet.com/ accessed on 30 January 2023) were used to brainstorm ideas and collect information about the issues identified and techniques currently being used to address them. Our focused definition phase required a stronger emphasis on eliciting information over discussion and brainstorming as logistic constraints required this stage to be conducted online [8]. The preparation phase planned for frequent switching between small group discussion to capture individual stakeholder viewpoints, and larger whole group activities so that the entire team could build on the ideas that emerge.

5.2. Focused Definition/Problem Exploration Phase

The focused definition/problem exploration phase of the design summit was run as a three-hour session conducted online using Zoom, due to a combination of factors relating to proximity to the COVID-19 outbreak and because it facilitated access to a large group. Utilizing the resources created in the preparation phase, 25 expert participants (teachers from primary and secondary schools in Australia) came together to understand, define and ideate the problem of how to provide training on how to support high-ability students in the classroom. Table 4 lists the participants involved in our focused action/problem definition phase.

Table 4.

Focused definition/problem exploration phase stakeholders.

The project manager and moderators guided participants through several activities and often acted as decisions makers to guide activities [19]. During the initial formulation of a shared understanding, we asked our participants to share their classroom/school challenges for working with students who are high ability (HA). The expert participants identified the following challenges:

- Student feedback or feedback improvement.

- Planning for differentiation.

- Challenging/extending HA students.

- Building school-wide practices.

- Remote learning experiences.

- Experience in teaching in HA, confidence of teachers.

- Stereotypes that HA students are well behaved (this is not true).

- Teachers are willing but need knowledge and consistency.

- Staff are allocated to subjects they have not taught.

To help in focusing on the problem of supporting HA students in the classroom, Table 5 summarizes the prompts and associated contributions received from participants when discussing the problem.

Table 5.

Focused definition problem identification.

A core method of data collection during the focused action was the use of breakout rooms. Following problem identification, we moved toward ideation and assigned different challenges to maximize the range of topics covered within the three-hour focused-action session. The moderators and project manager assisted by facilitating breakout groups. We set eight ideation challenges for participants. These are summarized in Table 6.

Table 6.

Focused definition ideation challenges.

During the summit, the forced closure of the breakout rooms and moving everyone back to the main meeting space acted like a circuit-breaker to the discussion/activity and returned participants to regroup with their peers. Ongoing access to the online collaboration space, emailed to participants afterwards as a reminder (i.e., Pinup and Padlet) allowed participants the opportunity to contribute outside of the allocated time frame as well. The online format for the design summit had the benefit that the contributions of every stakeholder are recorded within the online sites hosting each activity. This is important in a design summit to ensure continuity of information flow since different groups are involved in separate activities at each stage. This differs from a design sprint that maintains a whole-of-group consensus and instead ensures that contributions from individuals persist from one stage to the next [5]. Polling (voting) mechanisms are still retained in this format to ensure that points supported by multiple stakeholders retain a higher weight and can be taken forward into the iteration phase [2].

On completion of the focused definition phase the project manager and project team identified key outcomes from the summit by consolidating the ideas generated into common themes [21]. The outcomes from this phase of the design summit were identified as: course themes (related to educational outcomes for students with HA such as differentiation in HA and student profiling), utilization of 360-degree videos and immersive online experiences to simulate classroom practice, and the desire for access to resources and participation in professional development. These outcomes take the design summit forward towards concurrent prototyping, integrating stakeholder outcomes towards iterative prototyping testing in context.

5.3. Concurrent Prototyping in a Design Summit

Using the outcomes from the focused definition/problem exploration stage, the team entered a 6-month long phase of concurrent prototyping/product ideation. Selected ideas were taken forward from the focused definition phase such as the process of differentiation as being a fundamental concept required for the professional development of teachers working with high ability students. Existing written resources exist that cover this topic [25], as well as video presentations by experts who describe the principals involved. These were further extended with a thorough literature review [27] that would be available as a professional development resource. The project team identified through support of the focused definition phase outcomes the objective of developing additional resources beyond those currently available. These are the exemplars covered in the remainder of this case study. These would be distinctive in that they show the following:

- Are interactive and encourage active participation and provide agency for participants in determining the outcome.

- Provide opportunities to see the invisible (such as the reasoning by students as part of their thinking process).

- Require disassociation of personal identity to avoid risk to professional reputation and student identifiability/wellbeing.

- Explore the contextualized need to support a diverse range of high-ability students, across a range of disciplines, at various stages of learning [27].

- Can be used as a stand-alone resource, integrated with the other forms of teaching resource, and employed during Hyflex teaching practices where some participants are physically present while others joining synchronously online from across the state.

To engage in iterative/concurrent build and test that considers the above resources requirements, the following stakeholders engaged in this portion of the concurrent build and test process (Table 7). Our expert end users continued to be primary and secondary school teachers, identified during our preparation phase.

Table 7.

Concurrent product iteration phase stakeholders.

Of significance was that stakeholders were engaged in a variety of ways in elongated prototyping. For example, the technologist and interaction designers engaged in regular (daily) playtesting and feedback sessions facilitated through instant messaging. During these sessions product iteration focused on functionality, user experience and integration. To receive feedback from expert end users we conducted testing in context, in this case through testing the professional development course with teachers. Through integration of the prototypes in course content, direct feedback on the experience was received. The outcomes from playtesting and course testing informed prototyping going forward. Below, we describe both the build and test stages that occurred in prototype and how the project team, technologist and interaction designers used the feedback received on prototype one to drive the development of prototype two, while working concurrently on both prototypes.

5.3.1. Prototype Build One: Choose Your Own Adventure in VR

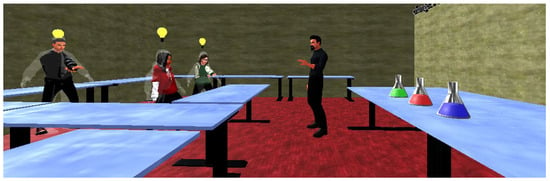

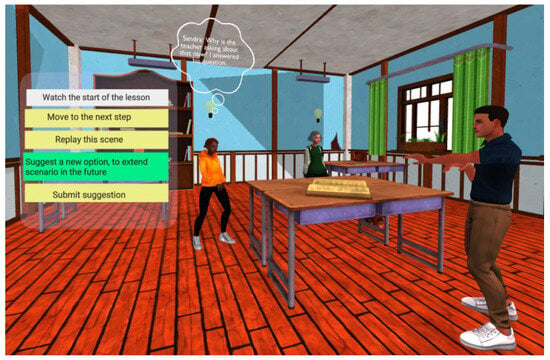

Prototype one is an interactive experience set in a classroom with a teacher and a number of students, some of whom represent HA students. The experience is presented in 3D, using Web-Based Virtual Reality. Figure 2 shows the environmental design of the prototype. The structure of the experience can be best described as a choose-your-own-adventure style narrative. The prototype has scene selection controls, with classroom discussion and student choice options displayed as buttons.

Figure 2.

Choose your own Adventure in VR Environment.

In the choose-your-own-adventure prototype, the teacher would present a lesson (in this case, a secondary level science lesson), and decision points would be introduced whenever an opportunity to practice differentiation arises. The participants would then have to decide on which action to follow based on their observations of the needs of individual students, as indicated by the interactions shown between students and teacher. Participants are free to move around the environment and observe the class from the perspective of the teacher, any one of the students, or any other position. Spatialized sound (in this case, volume changing by distance) allows the opportunity to eavesdrop on conversations between students by positioning the participant in proximity to the student.

When initiating prototyping, we built a script to navigate the participants through a structured scenario, with choice options made available for user selection. The script acted as a low-fidelity prototype to demonstrate to the project team how the concept of differentiation could be acted out in a mock classroom. Using the six Case Studies of High-Ability Students—Profile Checklist [25] available on the Victorian State Government Department of Education and Training’s FUSE website, the interaction designers and project teams developed a series of interactive choices and a broader narrative that aligned with each of the six-student profile ‘types’ so as to depict behaviors and attributes that could be used by participants to inform decisions around differentiation. Care needed to be taken when developing the script to leave in contentious content (i.e., teachers and students can make mistakes since the value of the simulation comes from how they might deal with these), avoid stereotypes (to capture the complexity of an individual who might have several motivating factors in any interaction), and enjoy the anonymity (express ideas without fear). This script was reviewed by the entire project team (see Table 7), both in terms of content and its relation to differentiation, with iteration of content over several script versions before implementation into a prototype virtual environment.

With the script prepared, the technologist and interaction designers moved towards prototype preparation using a game environment presented through web virtual reality. Rapid prototyping used motion capture to prepare synthetic avatars to represent the teacher and students in virtual classroom that could move and talk (see Figure 2 for an example of the characters generated). The project team wanted the participants to focus on the words, behaviors and interpersonal interactions of the avatars rather than the details of the experiment.

When developing the prototype, the project team realized that seeing the invisible part of behavior of the virtual students would be useful. A facility was added whereby clicking on an avatar causes a thought bubble to appear above their heads showing their reasoning at the time. This is particularly useful with HA students who may behave in a way that masks their abilities or may superficially appear to be disengaged from the learning experience [25]. The dual presentation of what is thought compared to what is spoken provides HA teachers with the opportunity to compare the internal and external personae of each student and alerts participants to the need to be aware that outward behaviors may not always tell the full story—a key learning outcome that we were aiming for with the design of this activity based on the feedback from the project team.

Furnishing for the classroom was included, but through further development and testing we elected not to include the distraction of physical objects that the avatars interact with (e.g., the test tubes and chemicals for the science experiment) to speed up prototyping outcomes towards a high-fidelity version available for testing with expert participants.

5.3.2. Prototype Evaluate/Test One: Choose Your Own Adventure in VR

The high-fidelity prototype ‘choose your own adventure’ was tested in August 2022 as part of a Hyflex course pilot with our expert end-users, i.e., teachers and school leaders (a session repeated with different participant groups over 2 days). The prototype was aligned to an activity on identifying or differentiating HA students in the classroom and made available to local and remote participants through being embedded into a learning management system. The prototype was successfully run across diverse devices, and engaged course participants in a shared immersive experience, gaining deeper insight into understanding HA students and embracing learnings from concurrent prototyping [25].

Prototype one used keyboard controls for locomotion, both for changing position and orientation. It was assumed that this control scheme would be simpler and was in line with the keyboard’s controls for other online experiences that provide comparable user experience. Through observation and feedback on prototype one, end users did indicate that these controls did adversely impact on their experience. Since the participants had just completed a previous activity which used the mouse to change orientation while viewing a 360-degree video the controls were changed to keyboard (movement) + mouse (orientation) for the session on the second day. Locomotion issues were not raised during the second session. From testing we found that controls schemes need to be both familiar, but also consistent across all the resources used during a course.

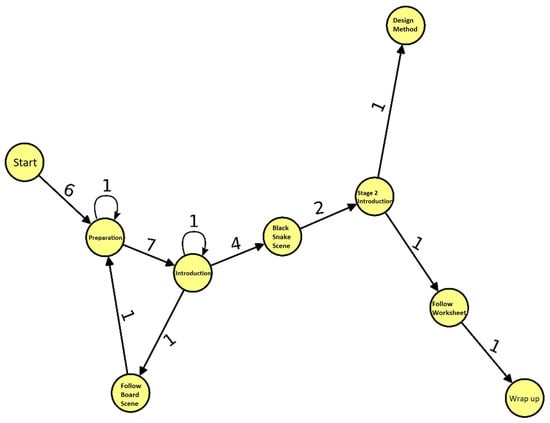

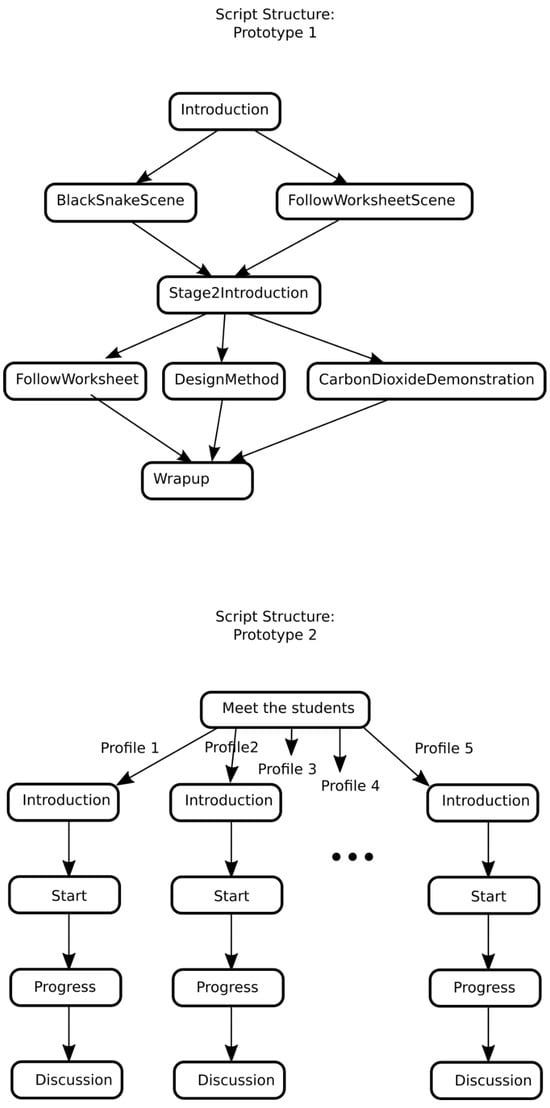

During evaluation with our expert end-users, it was evident that the time available for completing the experience was limited. When reviewing the choices made by the participants, many spent time replaying the introductory scene or exploring the setting and interacting with the avatars rather than progressing through the narrative. Figure 3 summarizes the progress of expert end-users when engaging with prototype one. The label on each edge indicates the number of times users transitioned between the two adjacent scenes. Few participants progressed beyond the preparation and introduction scenes. In hindsight, the initial script spent too much time on details that provide realism but do not have a direct bearing on the topic (e.g., teacher introducing the lesson in detail to the students). As an outcome of evaluation, we found that limiting exploration is better for activities with a time limit (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Analytics from evaluation of first prototype, the numbers represent user path selection.

Figure 4.

Changes to the script structure during each product iteration.

The outcomes from evaluating prototype one initiated further product iteration, resulting in prototype two where the build and test cycle are repeated utilizing the virtual environment and the scripts of prototype components (Figure 4).

5.3.3. Prototype Build Two: Student Profiling

In prototype two, the emphasis was changed from one of exploring teacher’s choices to that of profiling the different ’types’ of high-ability students for whom differentiation would be relevant. This is in recognition of the value received from engaging with the personalities of the avatars in the first prototype, rather than on instruction derived from a teacher in the virtual classroom. Exploration in prototype two was reduced by redeveloping the script, as shown in Figure 4, to reduce the choice element, replacing this with a single option at the start of the script where the participant picks one of five students to follow through the experience. In each scenario a virtual student would work with a partner (another HA student from a different profile) and the teacher to complete the science lesson 6. Figure 5 provides a close-up of a student’s thought that can be revealed through clicking on the light bulb above a student head. The student’s thoughts play a significant role in enriching the character of the student avatars. The reasoning process becomes important and so almost every scene includes details of the student’s thinking and reasoning during the process. The goal of the activity is now to create a profile of the selected student and relate this profile to the written descriptions provided by [25].

Figure 5.

Student Profiling in VR Student Thoughts.

5.3.4. Prototype Evaluate/Test Two: Student Profiling

The student profiling prototype was again evaluated through review with expert end users and clients, during delivery of the professional learning course on HA. The evaluation ran with a few minor technical challenges, such as issues with the integration of the experience with a new learning management system utilized as part of the HA course rollout, variations in individual devices used by experts and local bandwidth for remote participants. While these can all be addressed, it is worth noting that the structure of the design summit validation stage which integrates multiple prototypes was a necessary condition to identify these challenges.

The activity that scaffolded the student profiling activity started with an overview of the concept of profiling. Complications arose in that many of the student avatars wore similar attire (to represent the school uniform), and the simplified avatar representation did not provide sufficient detail to perform reliable identification by facial features alone. Comments from several end users indicated that they were using location in the scene as a proxy for student identity and were confused when a student’s position changed between scenes. Student names are included in the thought bubbles, but these are not visible until the participant triggers them. Given the nature of the time limited experience, identity cues for the avatars need to be explicit and distinctive. While some participants were enthusiastic about the full interactive virtual environment experience others did indicate a preference for a non-interactive version (such as a video and/or text script based on user experience preferences and technical constraints). Through the course delivery, end users focused on the content being explored, and the novelty/engaging nature of experience. Comments from participants collected during a post-design summit evaluation included: “I thought it was useful to discuss the specific challenges/student experience of high-ability students”, “it led to useful discussions with my group”, “This was very engaging and a cool way to present this info. Hadn’t seen it done that way before”. As an outcome of the activity, all participants correctly identified the profile associated with their assigned student (including some that appeared to exhibit some traits that ran across 2–3 of the profiles). Through expert review, protype two achieved the objectives of the design summit: to provide interactive and integrated resources into an activity about student profiles that can be included in the HA course as a formal product to help teachers explore how to apply differentiation.

Our case study has highlighted how to engage diverse stakeholders through the design process by describing the preparation required to include careful consideration of stakeholder time and skills throughout each phase of the design summit (as described in Table 1). Concurrent prototyping activities over many months enabled the design summit outcomes for education to be realized, with high fidelity prototyping resulting in a build available for testing and ultimate implementation into a course offering on HA. Along the way stakeholder feedback (such as expert end-user, see Table 2) was critical to inform the nuances of the prototype as it related to teaching students with HA. A shorter period of prototyping as a part of a design sprint would not have uncovered contextual details and feedback to ensure expert end-users (i.e., teachers!) got best use out of the prototypes developed [9]. For educational prototyping the ability to engage with diverse stakeholders was critical to communicating prototyping outcomes that were fit for the purpose of achieving design summit outcomes. Teachers make a critical contribution to the design process, particularly when considering prototyping in the classroom context [19]. Our case study and design summit method provide an approach for designers, technologists and project managers to consider when needing to engage in a design sprint or design thinking, offering an alternative over traditional design sprint approaches [5]. Through flexible phases that can be modified based on project requirements and stakeholder availability, a design summit can ensure prototyping outcomes can be validated with stakeholders in context. Like Rodriguez-Calero et al. [22] our approach adds to the field of design by providing actionable strategies that design teams can implement for effective stakeholder engagement, highlighting the importance of early iteration and concurrent prototyping to improve final product quality [2,26]. Early and ongoing stakeholder engagement enables multidisciplinary collaboration and the integration of diverse insight from the onset [25], ensuring prototyping occurs in context in agreement with stakeholder expectations [9].

6. Conclusions

A design summit can occur in many contexts [21] and addresses design thinking in a modified design sprint process. Core to the design summit approach are three phases of action (as shown in Figure 1) that engage a variety of stakeholders through purposeful activities that lead towards prototyping/product iteration. Stakeholder engagement forms critical consideration in each phase, ensuring maximum benefit can be obtained from those involved and towards project goals. This paper investigates the application of a design summit to educational prototyping, highlighting the need for a period of focused definition/problem exploration to elicit user requirements and ideate prototype ideas using a diverse set of stakeholders (Table 2), as relevant to the educational context. Through a phase of elongated and concurrent prototyping, ideation of prototypes can occur with high-fidelity outcomes being taken forward into implementation. This differs from the more traditional design sprint approach that may result in a prototype of a variety of different levels of fidelity. While prototypes form useful mechanisms for communication at all stages of the design process [8], our approach describes an alternative approach that enables prototyping to meet stakeholder expectations [11]. Our case study of educational prototyping describes how stakeholder engagement in defined phases informs the problem space, while helping the project team navigate towards testing of ideas through prototyping. Concurrent prototyping that engages stakeholders over time, while also testing in context, ensures outcomes meet stakeholders’ needs. In this case, through supporting teachers in understanding how differentiation can support a HA student.

The limitations of this study include the generalizability of the prototyping approach due to this being a single case evaluation. Outcomes from a design sprint will vary based on the experts involved and the domain being investigated. Future research is required to evaluate other prototyping processes that were informed by the design summit approach. Prototyping processes that do not share insights through concurrent prototyping need to be explored. By understanding what other prototyping processes may occur because of the condensed design summit process as described, we can better evaluate the suitability of the condensed design summit approach across multiple contexts beyond education.

Author Contributions

S.B., S.M., G.W.-B. and M.N. all contributed to the research design, data analysis and manuscript preparation. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study received ethics approval under: HAE-23-012.

Informed Consent Statement

All participants in this study were able to make informed consent regarding their participation.

Data Availability Statement

All data as presented in this paper is available from the author upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Arrington, T.L.; Willox, L. ‘I Need to Sit on My Hands and Put Tape on My Mouth’: Improving Teachers’ Design Thinking Knowledge, Skills, and Attitudes Through Professional Development. J. Form. Des. Learn. 2021, 5, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boloudakis, M.; Retalis, S.; Psaromiligkos, Y. Training Νovice teachers to design moodle-based units of learning using a CADMOS-enabled learning design sprint. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2018, 49, 1059–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bongiovanni, I.; Townson, P.; Kowalkiewicz, M. Bridging the academia-industry gap through design thinking: Research innovation sprints. In Research Handbook on Design Thinking; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2023; pp. 102–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooperrider, D.L. The Spark, the Flame, and the Torch: The Positive Arc of Systemic Strengths in the Appreciative Inquiry Design Summit. In Organizational Generativity: The Appreciative Inquiry Summit and a Scholarship of Transformation; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2013; pp. 211–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches, 3rd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kowitz, B.; Knapp, J.; Zeratsky, J. Sprint: How to Solve Big Problems and Test New Ideas in Just Five Days; Simon & Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Wangsa, K.; Chugh, R.; Karim, S.; Sandu, R. A comparative study between design thinking, agile, and design sprint methodologies. Int. J. Agil. Syst. Manag. 2022, 15, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deininger, M.; Daly, S.R.; Sienko, K.H.; Lee, J.C. Novice designers’ use of prototypes in engineering design. Des. Stud. 2017, 51, 25–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dresch, A.; Lacerda, D.P.; Antunes, J.A.V., Jr. Design Science Research; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauff, C.A.; Knight, D.; Kotys-Schwartz, D.; Rentschler, M.E. The role of prototypes in communication between stakeholders. Des. Stud. 2020, 66, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, V.G.; Canedo, E.D. Using design sprint as a facilitator in active learning for students in the requirements engineering course. In Proceedings of the 34th ACM/SIGAPP Symposium on Applied Computing, Limassol, Cyprus, 8–12 April 2019; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 1852–1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerber, E.; Carroll, M. The psychological experience of prototyping. Des. Stud. 2012, 33, 64–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, C.A.; Özkil, A.G. From Idea to Production: A Retrospective and Longitudinal Case Study of Prototypes and Prototyping Strategies. J. Mech. Des. 2020, 142, 031115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jake-Schoffman, D.E.; McVay, M.A. Using the Design Sprint process to enhance and accelerate behavioral medicine progress: A case study and guidance. Transl. Behav. Med. 2021, 11, 1099–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, B.; Crilly, N.; Ning, W.; Kristensson, P.O. Prototyping to elicit user requirements for product development: Using head-mounted augmented reality when designing interactive devices. Des. Stud. 2023, 84, 101147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keijzer-Broers, W.J.W.; de Reuver, M. Applying Agile Design Sprint Methods in Action Design Research: Prototyping a Health and Wellbeing Platform. In International Conference on Design Science Research in Information Systems; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 68–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwaber, K. Agile Project Managment with Scrum; Microsoft Press: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kirschner, P.A. Do we need teachers as designers of technology enhanced learning? Instr. Sci. 2015, 43, 309–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magistretti, S.; Dell’Era, C.; Doppio, N. Design sprint for SMEs: An organizational taxonomy based on configuration theory. Manag. Decis. 2020, 58, 1803–1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendonça de Sá Araújo, C.M.; Miranda Santos, I.; Dias Canedo, E.; Favacho de Araújo, A.P. Design Thinking Versus Design Sprint: A Comparative Study. In International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 291–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mor, Y.; Mogilevsky, O. The learning design studio: Collaborative design inquiry as teachers’ professional development. Res. Learn. Technol. 2013, 21, 22054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Calero, I.B.; Coulentianos, M.J.; Daly, S.R.; Burridge, J.; Sienko, K.H. Prototyping strategies for stakeholder engagement during front-end design: Design practitioners’ approaches in the medical device industry. Des. Stud. 2020, 71, 100977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Southall, H.; Marmion, M.; Davies, A. Adapting Jake Knapp’s Design Sprint Approach for AR/VR Applications in Digital Heritage. In Augmented Reality and Virtual Reality: The Power of AR and VR for Business; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soyupak, O. Embedding Design Sprint into Industrial Design Education. Des. Technol. Educ. Int. J. 2021, 26, 66–85. [Google Scholar]

- Victoria State Government Education and Training. Case Studies of High-Ability Students—Profile Checklist. In FUSE; 2020. Available online: https://fuse.education.vic.gov.au/Resource/LandingPage?ObjectId=a3971471-b85b-42ca-81f2-bc0b5607f995 (accessed on 1 September 2023).

- Žužek, T.; Gosar, Ž.; Kušar, J.; Berlec, T. A New Product Development Model for SMEs: Introducing Agility to the Plan-Driven Concurrent Product Development Approach. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žužek, T.; Kušar, J.; Rihar, L.; Berlec, T. Agile-Concurrent hybrid: A framework for concurrent product development using Scrum. Concurr. Eng. 2020, 28, 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).