Abstract

In this study, we propose a framework for synthesizing new characters by applying the features of a reference face to a source face using a diffusion model-based image editing technique. For an effective synthesis, a blank face of the sample is first generated by removing all features except the hairstyle, face shape, and skin tone. Then, facial features such as the eyes, eyebrows, nose, and mouth from the reference face are applied to the blank face of the source face. This strategy allows the creation of a new character that reflects the reference face’s features on the source face without producing unwanted artifacts or undesired blending of facial features.

1. Introduction

The increase in digital content such as webtoons and 2D animations requires more and more characters in various roles. The creation of a character heavily depends on the creativity of an artist. Character creation is a complicated process that combines creativity and technical skill since the quality of a character can significantly impact the immersion and success of the content. Recently, the progress of generative AI models has accelerated automatic character generation techniques for digital content on a great scale.

In recent years, deep learning-based image generation techniques based on generative adversarial networks (GANs) and diffusion models have established themselves as powerful tools in the field of image generation and editing [1,2,3,4,5,6]. These models demonstrate outstanding performance in synthesizing realistic and stylish images, especially in areas such as human faces and natural landscapes. However, they still face several limitations in character creation tasks. Character creation refers to the generation of stylized human figures, where the strict conditions required for human depiction must be satisfied, and the desired style must be applied without artifacts. The advances in diffusion models have enabled the development of high-resolution face editing technologies [7,8,9,10,11]. Techniques utilizing GANs and diffusion models struggle to effectively learn and apply the styles for characters in a consistent way. This is particularly challenging when synthesizing facial expressions that require fine emotional details. Additionally, prompt-based character generation methods [12,13,14,15,16] are difficult to apply, since there are inherent limitations in expressing facial features and desired styles through verbal descriptions.

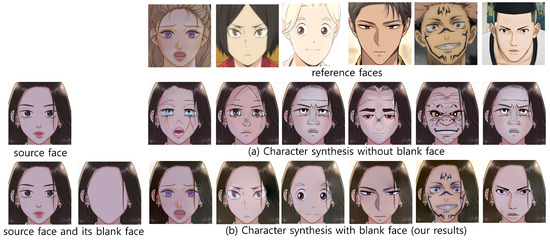

In this study, we propose a diffusion model-based character editing method that synthesizes a sample character onto the face of a reference character. We generate a blank face by removing all features from the reference character’s face except for the hair, face shape, and skin color. Next, we apply the facial features of the sample character, such as the eyes, eyebrows, nose, and mouth, to this blank face to reconstruct a new character. The reason for removing the key features of the reference character’s face is that diffusion model-based generation methods tend to strongly synthesize the sample character’s features with those of the reference character. This tendency presents a drawback, as it prevents the sample character from being effectively synthesized onto the reference character. Our result is illustrated in Figure 1, where we compare our results, which are generated from a blank face, with those generated without a blank face. We observe that the faces from the blank face show better results.

Figure 1.

A teaser: The results without blank faces are compared with those with blank faces (ours).

We demonstrate that our model outperforms the existing schemes based on GANs and diffusion models in character face generation through various experiments. Specifically, our approach offers a significant advantage in creative tasks by enabling more intuitive and user-friendly character face synthesis through the use of a desired style as a reference image.

2. Related Work

2.1. GAN-Based Image Editing

Image editing techniques based on Generative Adversarial Networks (GAN) present a powerful tool for adjusting specific attributes of images from text input. Abdal et al. [1] proposed a method for extracting image editing directions of StyleGAN in an unsupervised manner through Clip2StyleGAN, which has proven effective in generating images with various styles. Patashnik et al. [2] presented StyleCLIP which introduces a powerful method for modifying detailed characteristics of StyleGAN images based on text, while Xia et al. [3] developed TediGAN, a technique for generating and manipulating diverse facial images following textual instructions. Andonian et al. [4] presented Paint by Word and Radford et al. [5] developed the CLIP model and presented a great scale contribution to understanding and generating images based on natural language, laying the foundation for text-based image editing. Gal et al. [6] introduced a domain adaptation technique with StyleGAN-NADA, leveraging CLIP’s guidance to effectively adapt image generators across various domains.

2.2. Image Composition

Image composition that seamlessly blends characteristics from various images is one of the essential components in image editing tasks. Jia et al. [17] proposed a method for intuitive image composition through the Drag-and-Drop Pasting technique, while Chen et al. [18] developed realistic image composition techniques using adversarial learning. Guo et al. [19] introduced a method to maximize the coherence of composite images through Intrinsic Image Harmonization, and Xue et al. [20] presented an enhancing scheme for the texture of composed images by proposing a Deep Comprehensible Color Filter Learning Framework for high-resolution image harmonization.

2.3. Diffusion Model-Based Image Editing

Diffusion models have recently brought significant innovation to the field of image generation and editing. Ho et al. [21] introduced Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models, which present new possibilities for high-quality image synthesis. This approach has been widely adopted across various image generation and editing tasks. Rombach et al. [22] proposed Latent Diffusion Models for high-resolution image synthesis that allows more efficient and precise image generation.

Diffusion-based image editing techniques based on these models provide a powerful tool for manipulating images using text or visual instructions. Avrahami et al. [7] presented Blended Diffusion that allows text-based editing of natural images, while Hertz et al. [8] developed Prompt-to-Prompt Image Editing that achieves precise image editing through cross-attention control. Kawar et al. [9] developed IMAGIC which presents real-image editing based on text input, and Kim et al. [10] developed DiffusionCLIP, which is a more powerful and flexible method for manipulating images according to textual guidelines. Ruiz et al. [11] proposed Dreambooth for fine-tuning text-to-image diffusion models to a specific subject, enabling more refined image generation for a given reference.

2.4. Prompt-Based Image Editing

Diffusion-based image editing techniques using visual prompting focus on applying the style and characteristics of sample images in a reference image. Brown et al. [23] pioneered the possibilities for processing various visual inputs using language models, which formulated the basis for visual prompting techniques. Jia et al. [24] proposed a method called Visual Prompt Tuning, which achieves high performance with limited data by adjusting parts of the parameters of a pre-trained model. This approach enhances the adaptability of the model, especially for the quick adaptation to new tasks. However, it shows limitations in handling highly complex transformations in specific domains. Bar et al. [12] introduced an inpainting-based visual prompting technique, where specific regions of an image are masked and then restored based on sample images. This method can add natural details with consistency in the restored area. However, it may be constrained for large style transformations. Yang et al. [13] proposed a new image editing method using a diffusion model, which reflects the style and characteristics of a sample image. This model synthesizes new styles in the masked area based on the sample images. It shows high effectiveness in editing human faces. Even though this model precisely reflects the reference styles, it requires extensive training data and significant computational resources. Wang et al. [14,15] proposed a model that combines in-context learning with visual prompting, which enables adaptation to new tasks based on sample images. This approach offers the advantage of performing various image editing tasks with minimal data and demonstrates excellent model flexibility. However, due to the complexity of the model, the training requires a lot of temporal resources. Nguyen et al. [16] proposed a new method called “Visual Instruction Inversion” which executes image editing based on visual commands. This model allows intuitive image editing without text instructions. However, this model shows restricted performance for complex editing tasks. A multi-source domain information fusion network [25] and a domain feature decoupling network [26] can be applied to our approach to extracting facial features from a source face.

3. Our Method

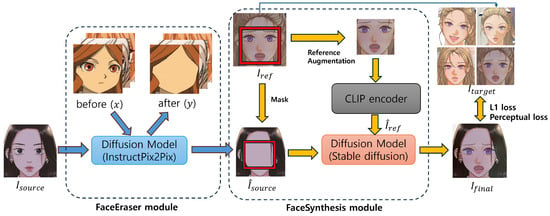

We propose a novel method for automating character synthesis from various 2D images using two Diffusion models. The overview of this method is illustrated in Figure 2. The proposed approach consists of two modules: (1) FaceEraser module that generates a blank face, which lacks eyes, nose, and mouth, from a 2D image and (2) the FaceSynthesis module that synthesizes a new face by combining new eyes, nose, and mouth onto the blank face. The purpose of FaceEraser module is to generate blank faces and supply them to FaceSynthezer module. However, the FaceSynthesizer module does not influence the FaceEraser module. A comprehensive comparison of these modules is presented in Figure 1, where the results without blank faces are compared with those with blank faces. In producing blank faces and synthesizing characters’ faces, we employ a diffusion model, which is proven to be very effective in faces. In many studies, diffusion models are proven to show better performance in synthesizing scenes than other techniques including autoencoder and GAN. The facial features employed in producing blank faces and in synthesizing characters’ faces are extracted using the CLIP encoder, which is currently very widely employed for various image editing studies.

Figure 2.

The overview of our method. The FaceEraser module employs InstructPix2Pix to build a blank face from a character’s face. The blank face, which is produced by the FaceEraser module is supplied to FaceSynthesizer module, which applies the facial features of a source face to a reference face. The facial features in both modules are extracted using CLIP encoder. The generation of blank face and final result is executed using a diffusion model.

3.1. FaceEraser Module

The FaceEraser module is trained to automatically generate a blank face from various 2D face images. This module is designed using diffusion-based visual prompting that employs before-and-after image pairs. This module learns the editing direction through CLIP embedding loss estimated from the before and after image pairs. This process follows the following procedure.

- Step 1. Learning the CLIP Embedding Direction

Given an image pair x, y, the editing direction between the “before” image x and the “after” image y, which represents the blank face, is calculated using CLIP embedding loss. This allows the module to learn the transformation direction for generating a blank face. The formula is defined as follows:

where and are the CLIP embedding loss of y and x, respectively. The module is trained to minimize the cosine distance in the CLIP embedding space to align with this editing direction.

where is the embedding vector of a blank face.

- Step 2. Noise Injection and Reconstruction Loss

The diffusion model generates a blank face by reconstructing a noisy input image. During this process, this module is trained by minimizing the mean squared error (MSE) loss, which is defined as follows:

where y denotes blank face, , the embedding vector, , the noisy version of the blank face at time step t, , the original image, , and the noise predicted by the diffusion model.

This training process is crucial for this module in order to learn how to remove specific facial features (e.g., eyes, nose, mouth) from the original image in an effective way. After the training, the FaceEraser module automatically generates blank faces from a variety of 2D face images.

3.2. FaceSynthesis Module

The FaceSynthesis module is trained to synthesize new facial features, such as eyes, nose, and mouth, onto the blank face generated by the FaceEraser module. This module is designed based on the basic structure of a diffusion model, where a reference image is blended into the masked regions to produce the final output. The training process of this module proceeds in the following steps.

- Step 1. Definition of Masked Area

A specific masked region M is defined on the blank face. This masked region corresponds to the areas where the facial features (eyes, eyebrows, nose, and mouth, etc.) will be synthesized.

- Step 2. Reference Augmentation

To address the issue of limited data, a reference augmentation technique was applied. The reference images were transformed under different angles, lighting conditions, and styles to improve the model’s generalization performance.

- Step 3. Extracting facial features using CLIP encoder

In FaceSynthesizer, facial features from the reference image are extracted and applied to the source image. During this process, reference augmentation is performed on the reference image to extract the facial feature regions, which are then applied to appropriate feature vectors. This encoding process utilizes a pretrained CLIP encoder [5]. To effectively apply the features of the reference image to the source image, compressed mask regions are incorporated during generation. Using the CLIP encoder, the system not only comprehends the content of the reference image but also avoids a simple copy-and-paste of features. Instead, it maintains semantic information over high-frequency details, providing a more meaningful feature transfer. In this study, feature representation is achieved by encoding images of size into a 1024-dimensional CLIP-encoded vector.

- Step 4. Synthesizing result image using masking and diffusion model

This module receives the blank face of an original image and the CLIP-encoded reference image , and synthesizes CLIP-encoded features into the masked region M to generate the final output, , which is defined as follows:

where M denotes binary mask indicating the regions to be synthesized, ⊙, element-wise multiplication. In this step, we employ the stable diffusion model [22] for an effective synthesis of the source image and the reference image.

- Step 5. Loss Functions

The training process utilizes two types of loss functions: L1 loss and perceptual loss, which are defined. The L1 loss, which minimizes the difference between the generated image and the reference image , is defined as follows:

The perceptual loss, which minimizes the difference in feature space, is defined as follows:

where represents the feature map of the i-th layer in a pre-trained network.

3.3. The Whole Process

We present a framework for generating complete facial synthesis results using two diffusion model-based modules. First, the FaceEraser module generates a blank face from the original 2D image. Then, the FaceSynthesis module combines new facial features, such as eyes, eyebrows, nose, and mouth, onto the blank face to complete a new face. This approach enables precise and diverse facial expressions across various 2D images, offering greater flexibility and expressiveness compared to traditional face synthesis techniques.

4. Implementation and Results

4.1. Implementation and Training

We implemented our model in a cloud platform with Intel Xeon Pentium 8480 and nVidia A100 80GB. Our backbone network is InstructPix2Pix [27], with a CLIP encoder, since the embedding loss function is employed to guide image transformations. The training process is divided into two steps. The first step is blank character training, where we used the Visii model [16] and trained on 350 blank character images. The training takes approximately one hour. The hyperparameters are as follows: 0.001 for the embedding learning rate, 1000 for optimization steps, 0.1 for a CLIP loss weight (), 4.0 for MSE loss weight (), and 100 for an evaluation step interval. The second step is the face synthesis training, where we employed the Paint-by-Example model [13] and trained on 50,000 character face images, which includes augmented images. This training takes approximately 48 h. The key hyperparameters are as follows: 1 × 10−5 for a learning rate, 1000 for optimization steps, and 40 for epochs. Through this training process, our model performs a variety of face synthesis effectively. The specific configurations and computational resources of FaceEraser and FaceSynthesizer modules of our framework are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

The specifications, hyperparameters and computational resources of our framework.

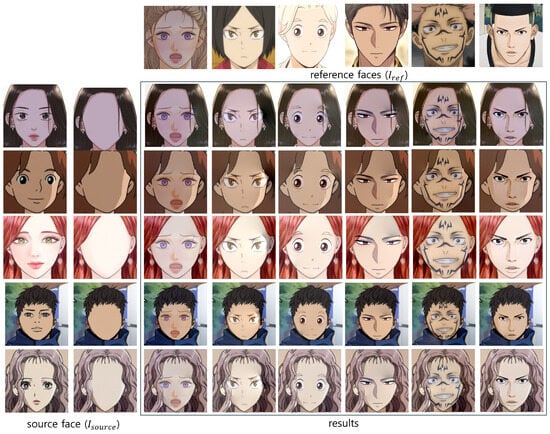

4.2. Results

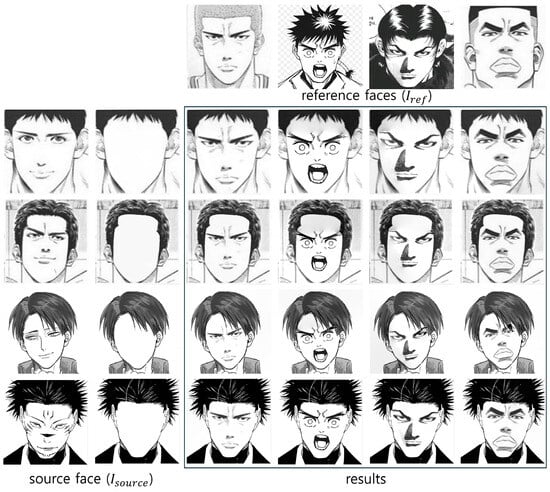

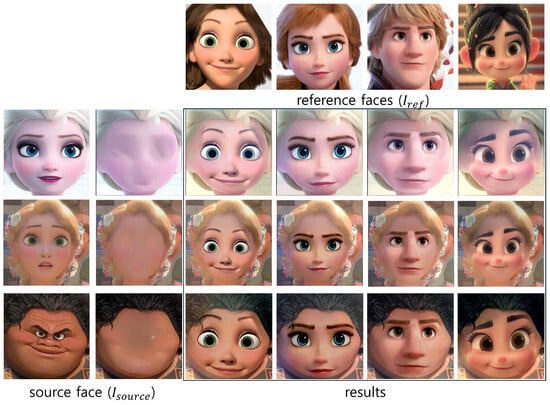

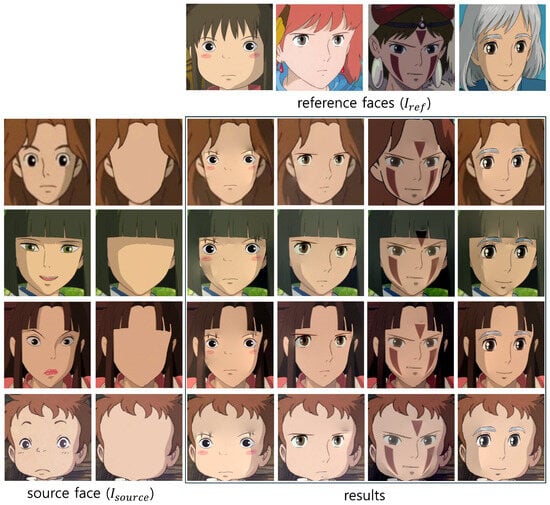

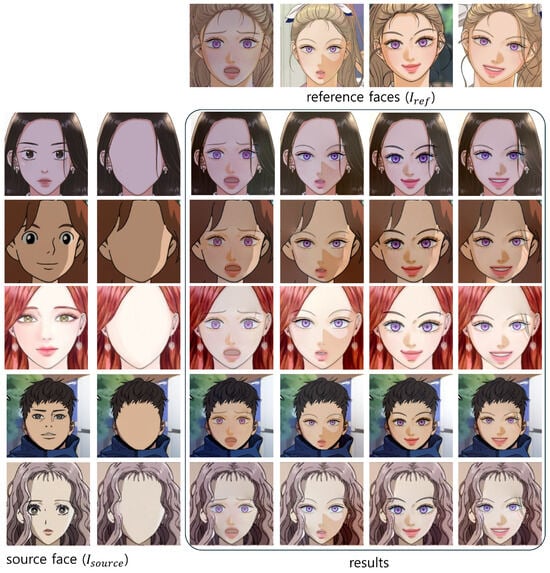

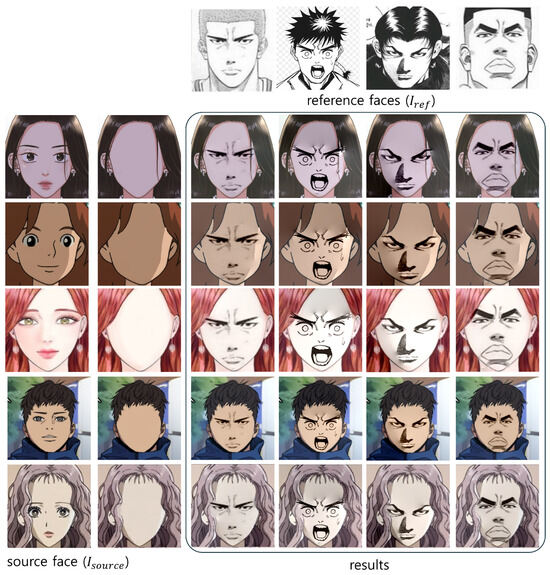

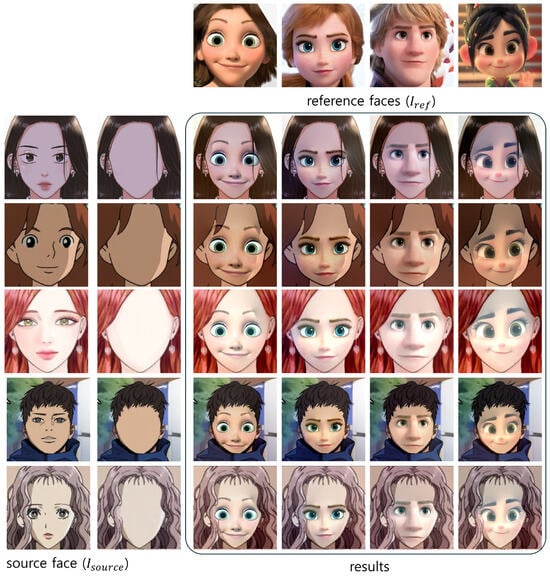

We execute our model and produce several results. We apply our scheme to the characters from various sources. Figure 3 shows our results whose reference images () are from webtoons and 2D animations. Figure 4 illustrates the results on the source images from black-and-white sketch-styled images, and Figure 5 shows the results are from 3D animation characters. Finally, Figure 6 illustrates the results from 2D animation characters. In these results, we employ various source images, which are transformed into blank faces.

Figure 3.

The result of our method. The reference faces and source faces are sampled from webtoon contents.

Figure 4.

The result of our method. The reference faces and source faces are sampled from black-and-white sketch-styled contents.

Figure 5.

The result of our method. The reference faces and source faces are sampled from 3D animation contents.

Figure 6.

The result of our method. The reference faces and source faces are sampled from cell animation contents.

We further generate a series of experiments using our models. Figure 7 illustrates the generation of various expressions from an identical character. The first row of Figure 7 presents four different expressions of a character. These expressions are applied to the faces in the leftmost column. In Figure 7, various expressions of the character in the top row are applied while the identity of the character is preserved.

Figure 7.

Application of various expressions.

In Figure 8 and Figure 9, we experimentally generated characters with mixed styles, respectively. We applied the faces in black-and-white sketch-styled characters to 2D animation characters in Figure 8, and the faces in 3D animation characters to 2D animation characters in Figure 9. In these figures, we find out that the characters from one domain can be applied to the characters in different domains.

Figure 8.

A mixed generation: the characters in black-and-white sketch-style are applied to the characters in 2D animation.

Figure 9.

A mixed generation: the characters in 3D animation are applied to the characters in 2D animation.

5. Evaluation

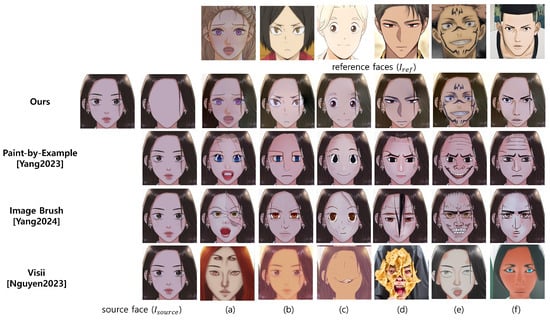

We evaluate our results by comparing them with those from several existing studies [13,16,28] in Figure 10. Our result shows distinguished quality compared to those from the existing studies. For a quantitative comparison, we estimate three metrics: visual CLIP score, image CLIP score and FID score. We apply these estimation schemes to the images in Figure 3.

Figure 10.

Comparison of our results with those from existing studies. The six reference images are distinguished by the caption (a–f), which are used in Tables 2, 3 and 5 [13,16,28].

5.1. Quantitative Evaluation

Table 2 presents visual CLIP scores of our results and the compared schemes. According to Table 2, our method achieved the highest performance, recording an average score of 0.8553 compared to other methods.

Table 2.

Visual CLIP score compared with important existing studies (Red figures denote the best-scored model).

We also applied ANOVA analysis using these scores and yielded an F-statistic of 25.83 and a p-value of . Since the p-value is smaller than 0.05, this result demonstrates a statistically significant difference among the mean scores of the four methods.

Similarly, Table 3 presents image CLIP scores of our results and the compared schemes. According to Table 3, our method also achieved the highest performance with an average score of 0.9180.

Table 3.

Image CLIP score compared with important existing studies (Red figures denote the best-scored model).

However, ANOVA analysis in this case produced an F-statistic of 2.97, with a p-value of 0.052. Even though this p-value is close to 0.05, it exceeds the significance threshold, indicating that the observed mean differences are not statistically significant.

Finally, Table 4 presents the FID of our and the compared schemes. In comparing two pairs of images including source and result images and reference and result images, our scheme shows a lower FID than the compared schemes.

Table 4.

FID score compared with important existing studies (Red figures denote the best-scored model).

In summary of the quantitative comparison, our method shows the highest performance in both visual CLIP and image CLIP scores, with a statistically significant superiority demonstrated specifically in the visual CLIP scores.

5.2. Qualitative Evaluation

For a qualitative evaluation, We conduct a user study. For this purpose, we hired 30 voluntary participants; 21 of them are in their 20s and 9 in their 30s; 16 are females and 14 are males. To compare the results generated by existing methods and our proposed method, we prepared our survey based on Figure 10. The evaluation focused on three key aspects:

- Question 1: Does the resulting image preserve the facial shape, hairstyle, and tone of the source image?

- Question 2: Are the facial features and expressions of the reference image well-reflected in the result?

- Question 3: Is the resulting image naturally and seamlessly synthesized without noticeable artifacts or noise?

Participants were presented with six pairs of source-reference images from Figure 10a–f and asked to select the best result from among four methods, including our results. The responses are summarized in Table 5. Our method overwhelmingly received the highest evaluation as the best result, demonstrating that the outputs generated by our approach are visually convincing.

Table 5.

The results of the user study (Red figures denote the best-scored model).

Furthermore, ANOVA analysis was executed on the user study data. This analysis reveals statistically significant differences in the mean scores among the four methods for all questions. For Question 1, the ANOVA results yielded an F-statistic of 96.19 and a p-value of , indicating that our method outperformed the other methods. For Question 2, the F-statistic was 15,961.33 with a p-value of , demonstrating the superior performance of our method. Similarly, for Question 3, the F-statistic was 200.02 with a p-value of , confirming statistically significant performance differences among the methods.

Notably, our method achieved the highest total score across all questions, showing statistically significant superiority compared to Paint-by-Example [13], Image Brush [28], and Visii [16].

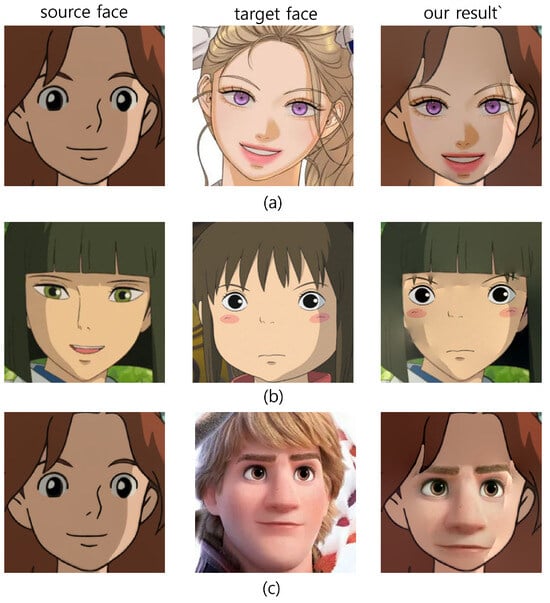

5.3. Limitations

Our results show several artifacts since our model synthesizes characters that are created under diverse conditions, such as varying lighting effects and the presence of hair. In Figure 11a, an artifact arises when a reference face occluded by hair is applied to a source face. The hair of a reference face that still remains in the final result becomes an artifact. Figure 11b illustrates an error where shading discrepancies between the source face and the reference face result in reversed shadows, producing shading artifacts on both sides of the synthesized face. Figure 11c demonstrates a problem associated with merging faces under differing shading effects: the source face is created by a two-tone shading style, which is typical of 2D animation, while the reference face is created by a smooth shading typical of 3D animation. When these styles are combined, overlapping artifacts appear in the highlight regions due to the conflicting shading effects.

Figure 11.

The limitations of our method: (a) shows the artifacts from the occluding hair, (b) shows the shading discrepancies from different direction of lightings, and (c) shows the problem from different shading policies.

These limitations are attributed to our approach, which seeks to generate new characters not only from similar styles but also from characters with different styles. Addressing these artifacts remains challenging. To resolve these limitations, we plan to enhance the model by designing a method that separates shading information from characters for independent processing. This improvement will be incorporated into future research efforts.

6. Conclusions and Future Work

We present a novel approach that synthesizes the faces of characters from various contents using a diffusion model-based approach. For an efficient synthesis, we build a blank face from a source face and apply the facial features of reference faces. We effectively apply our scheme to characters from various types of content including webtoon, black-and-white sketch, 3D animation and cell animation. A series of comparisons with the existing studies prove the excellence of our approach.

As a future work, we plan to extend the capability of our approach into cross-content synthesis. Furthermore, we plan to apply our approach to the full body of a character instead of only on the face. In many applications, the clothes and poses of a character can be synthesized from various characters. Our approach, which is extended to the full body of a character, will increase the power of expressing various contents with the users’ intent.

Author Contributions

Methodology, Methodology, Software, W.C.; Conceptualization, Writing—original draft preparation, H.Y.; Supervision, Writing—review and editing, K.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported from Sangmyung University at 2022.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Abdal, R.; Zhu, P.; Femiani, J.; Mitra, N.; Wonka, P. Clip2StyleGAN: Unsupervised extraction of StyleGAN edit directions. In Proceedings of the ACM SIGGRAPH 2022 Conference Proceedings, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 7–11 August 2022; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Patashnik, O.; Wu, Z.; Shechtman, E.; Cohen-Or, D.; Lischinski, D. StyleCLIP: Text-driven manipulation of StyleGAN imagery. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Montreal, QC, Canada, 10–17 October 2021; pp. 2085–2094. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, W.; Yang, Y.; Xue, J.H.; Wu, B. TEDIGAN: Text-guided diverse face image generation and manipulation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 2256–2265. [Google Scholar]

- Andonian, A.; Osmany, S.; Cui, A.; Park, Y.; Jahanian, A.; Torralba, A.; Bau, D. Paint by word. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2103.10951. [Google Scholar]

- Radford, A.; Kim, J.W.; Hallacy, C.; Ramesh, A.; Goh, G.; Agarwal, S.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A.; Msihkin, P.; Clark, J.; et al. Learning transferable visual models from natural language supervision. In Proceedings of the 38th International Conference on Machine Learning, Virtual, 8–24 July 2021; pp. 8748–8763. [Google Scholar]

- Gal, R.; Patashnik, O.; Maron, H.; Bermano, A.H.; Chechik, G.; Cohen-Or, D. StyleGAN-NADA: CLIP-guided domain adaptation of image generators. ACM Trans. Graph. 2022, 41, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avrahami, O.; Lischinski, D.; Fried, O. Blended diffusion for text-driven editing of natural images. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 18208–18218. [Google Scholar]

- Hertz, A.; Mokady, R.; Tenenbaum, J.; Aberman, K.; Pritch, Y.; Cohen-Or, D. Prompt-to-prompt image editing with cross attention control. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2208.01626. [Google Scholar]

- Kawar, B.; Zada, S.; Lang, O.; Tov, O.; Chang, H.; Dekel, T.; Mosseri, I.; Irani, M. Imagic: Text-based real image editing with diffusion models. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 18–22 June 2023; pp. 6007–6017. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, G.; Kwon, T.; Ye, J.C. DiffusionCLIP: Text-guided diffusion models for robust image manipulation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 2426–2435. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz, N.; Li, Y.; Jampani, V.; Pritch, Y.; Rubinstein, M.; Aberman, K. Dreambooth: Fine tuning text-to-image diffusion models for subject-driven generation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 18–22 June 2023; pp. 22500–22510. [Google Scholar]

- Bar, A.; Gandelsman, Y.; Darrell, T.; Globerson, A.; Efros, A. Visual prompting via image inpainting. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2022, 35, 25005–25017. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, B.; Gu, S.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, T.; Chen, X.; Sun, X.; Chen, D.; Wen, F. Paint by example: Exemplar-based image editing with diffusion models. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 18–22 June 2023; pp. 18381–18391. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Wang, W.; Cao, Y.; Shen, C.; Huang, T. Images speak in images: A generalist painter for in-context visual learning. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 18–22 June 2023; pp. 6830–6839. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Jiang, Y.; Lu, Y.; He, P.; Chen, W.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, M. In-context learning unlocked for diffusion models. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2023, 36, 8542–8562. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, T.; Li, Y.; Ojha, U.; Lee, Y.J. Visual instruction inversion: Image editing via visual prompting. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2023, 36, 9598–9613. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, J.; Sun, J.; Tang, C.K.; Shum, H.Y. Drag-and-drop pasting. Acm Trans. Graph. 2006, 25, 631–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.C.; Kae, A. Toward realistic image compositing with adversarial learning. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Long Beach, CA, USA, 16–17 June 2019; pp. 8415–8424. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Z.; Zheng, H.; Jiang, Y.; Gu, Z.; Zheng, B. Intrinsic image harmonization. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 16367–16376. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, B.; Ran, S.; Chen, Q.; Jia, R.; Zhao, B.; Tang, X. DCCF: Deep comprehensible color filter learning framework for high-resolution image harmonization. In Proceedings of the ECCV 2022, 17th European Conference, Tel Aviv, Israel, 23–27 October 2022; pp. 300–316. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, J.; Jain, A.; Abbeel, P. Denoising diffusion probabilistic models. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2020, 33, 6840–6851. [Google Scholar]

- Rombach, R.; Blattmann, A.; Lorenz, D.; Esser, P.; Ommer, B. High-resolution image synthesis with latent diffusion models. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 10684–10695. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, T.; Mann, B.; Ryder, N.; Subbiah, M.; Kaplan, J.D.; Dhariwal, P.; Neelakantan, A.; Shyam, P.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A.; et al. Language models are few-shot learners. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2020, 33, 1877–1901. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, M.; Tang, L.; Chen, B.C.; Cardie, C.; Belongie, S.; Hariharan, B.; Lim, S.N. Visual prompt tuning. In Proceedings of the ECCV 2022, 17th European Conference, Tel Aviv, Israel, 23–27 October 2022; pp. 709–727. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, T.; Yang, J.; Tang, Q. A multi-source domain information fusion network for rotating machinery fault diagnosis under variable operating conditions. Inf. Fusion 2024, 106, 1022278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, T.; Yang, J.; Wang, W.; Fan, X. A domain feature decoupling network for rotating machinery fault diagnosis under unseen operating conditions. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2024, 252, 110449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, T.; Holynski, A.; Efros, A.A. Instructpix2pix: Learning to follow image editing instructions. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; pp. 18392–18402. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Peng, H.; Shen, Y.; Yang, Y.; Hu, H.; Qiu, L.; Koike, H. ImageBrush: Learning Visual In-Context Instructions for Exemplar-Based Image Manipulation. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2024, 36, 48723–48743. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).