Abstract

This study investigates the strategic decision-making abilities of large language models (LLMs) via the game of Tic-Tac-Toe, renowned for its straightforward rules and definitive outcomes. We developed a mobile application coupled with web services, facilitating gameplay among leading LLMs, including Jurassic-2 Ultra by AI21, Claude 2.1 by Anthropic, Gemini-Pro by Google, GPT-3.5-Turbo and GPT-4 by OpenAI, Llama2-70B by Meta, and Mistral Large by Mistral, to assess their rule comprehension and strategic thinking. Using a consistent prompt structure in 10 sessions for each LLM pair, we systematically collected data on wins, draws, and invalid moves across 980 games, employing two distinct prompt types to vary the presentation of the game’s status. Our findings reveal significant performance variations among the LLMs. Notably, GPT-4, GPT-3.5-Turbo, and Llama2 secured the most wins with the list prompt, while GPT-4, Gemini-Pro, and Mistral Large excelled using the illustration prompt. GPT-4 emerged as the top performer, achieving victory with the minimum number of moves and the fewest errors for both prompt types. This research introduces a novel methodology for assessing LLM capabilities using a game that can illuminate their strategic thinking abilities. Beyond enhancing our comprehension of LLM performance, this study lays the groundwork for future exploration into their utility in complex decision-making scenarios, offering directions for further inquiry and the exploration of LLM limits within game-based frameworks.

Keywords:

large language model; LLM; benchmark; evaluate; performance; test; Tic-Tac-Toe; AI; game; strategic; decision-making; prompt engineering; analysis; leaderboard; AGI; competition; championship; text-based game; challenge; AI21; Jurassic Ultra; Anthropic; Claude; Gemini; Gemini-Pro; GPT-3.5; GPT-4; Meta; Llama2; Mistral 1. Introduction

In the 1983 movie “WarGames”, a fictional AI concludes that nuclear war has no winner by simulating Tic-Tac-Toe games, leading it to refrain from launching missiles [1,2]. Although this scenario is far removed from current AI capabilities, recent advancements in large language models (LLMs) have marked significant progress in the field. Large language models (LLMs) are capable of generating text by replicating language patterns, grammar, and facts after learning from a vast database of existing text. The term ‘large’ refers to the extensive number of parameters these models possess, which enables them to understand and produce complex and nuanced text [3]. These developments prompt questions about the potential for achieving Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) [4] and the timeline for such advancements. Predictions on the timeline for AGI vary [5,6], with some experts suggesting its inevitability [7]. A critical challenge in the journey towards AGI is developing benchmarks to assess AI’s evolving intelligence.

In this study, we assess the capabilities of several leading large language models (LLMs) by evaluating their performance in playing Tic-Tac-Toe. This evaluation aims to gauge their understanding of the game’s rules and their strategic decision-making abilities. To facilitate this, we developed a mobile application that enables LLMs to autonomously engage in Tic-Tac-Toe games, either solo or against each other. The evaluation utilizes two types of prompts to determine the LLMs’ ability to comprehend and effectively participate in this fundamental game.

2. Background and Related Research

2.1. History of Large Language Models

Beginning in the 2010s, the deep learning revolution significantly transformed the landscape of natural language processing (NLP). This era witnessed the emergence of advanced neural network architectures, notably Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks [8], which marked a pivotal shift in enhancing models’ abilities to process sequential data, such as text. Additionally, this period introduced innovative word embeddings techniques, including Word2Vec [9] and GloVe [10], which represented words in vector spaces to capture their semantic meanings more effectively.

The mid-2010s saw the groundbreaking introduction of Transformer architecture in 2017 [11], which strongly influenced the evolution of language models. Transformer architecture enabled the parallel processing of words, significantly improving efficiency and enhancing the handling of long-range dependencies in text. This advancement paved the way for the development of models such as BERT (Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers) [12] and OpenAI’s GPT (Generative Pre-trained Transformer) series [13]. BERT represented a leap forward in understanding context by analyzing the relationships of words within sentences, while the GPT series became known for its generative capabilities, demonstrating exceptional language generation and understanding [3].

As we entered the 2020s, the scale of large language models grew exponentially, leading to the development of models characterized by their billions of parameters and remarkable performance across a wide range of NLP tasks. Recently, models such as ChatGPT [14], GPT-4 (Generative Pre-trained Transformer 4) by OpenAI [15], Gemini by Google [16], Claude by Anthropic [17], and Jurassic by AI21 [18], including open-source options like Llama2 by Meta [19,20] and Mistral by Mistral [21], have emerged. These models have showcased significant advancements in the field, further pushing the boundaries of what is possible with large language models.

Large language models (LLMs) are utilized in diverse tasks such as text summarization, language translation, content generation, and question-answering [22]. LLMs also contribute to interdisciplinary areas, including drug discovery [23], financial modeling [24], and educational technology [25,26], improving automation and efficiency in various fields and enhancing human–computer interactions. Emerging software tools like LangChain (open source software: https://github.com/langchain-ai/langchain, accessed on 8 March 2024) enhance the use of large language models by offering tools and frameworks that simplify their integration into applications, thereby increasing their accessibility and effectiveness across different fields [27].

2.2. Large Language Model’s Benchmarks

Large language models (LLMs) yield stochastic outputs, which means their responses may differ even when presented with identical input [28]. Consequently, evaluating LLMs requires a sophisticated strategy that goes beyond traditional metrics used in machine learning and deep learning, such as accuracy, precision, F1 score, and mean squared error (MSE). To thoroughly understand an LLM’s ability to produce contextually appropriate and coherent text, it is crucial to employ well-established datasets and benchmarks specifically crafted for LLM research [29]. Selecting the appropriate evaluation datasets and tools is essential for accurately assessing an LLM’s performance and grasping its full potential. The chosen datasets should challenge specific capabilities, such as reasoning or common sense knowledge, and should also evaluate potential risks, such as the spread of disinformation or copyright violations.

Benchmarks such as GLUE [30], SuperGLUE [31], HELM [32], MMLU [33], BIG-bench [34], and ARC [35] provide a diverse set of tasks aimed at assessing various facets of large language models’ (LLMs) capabilities. Introduced in 2018, GLUE (General Language Understanding Evaluation) is a suite of natural language understanding challenges that includes tasks like sentiment analysis and question-answering, designed to foster the development of models adept at a wide range of linguistic tasks. Following GLUE, SuperGLUE was launched in 2019 to build upon and expand its scope by adding new, more demanding tasks and enhancing existing ones, such as multi-sentence reasoning and complex reading comprehension. These benchmarks feature leaderboards that allow for the comparison of models and the tracking of advancements in LLMs, thereby serving as critical resources for evaluating model performance in a competitive and clear manner [36].

As large language models (LLMs) have increased in size, their performance on benchmarks such as SuperGLUE has started to meet and even exceed human capabilities in certain domains. This significant milestone highlights the necessity for more rigorous benchmarks that can further extend the capabilities of LLMs. In response, the Massive Multitask Language Understanding (MMLU) benchmark was developed [33]. This benchmark tests LLMs in a broad and varied context, demanding that they exhibit extensive world knowledge and problem-solving abilities across a diverse array of subjects, such as elementary mathematics, US history, computer science, and law.

Another significant benchmark is BIG-bench [34], which comprises 204 varied tasks encompassing linguistics, mathematics, common sense reasoning, biology, and software development. BIG-bench is notable not only for its breadth but also for its scalability, being available in three sizes to accommodate the practical constraints of running such extensive benchmarks. This scalability is particularly important as the operational costs of testing large models can be prohibitively expensive, making BIG-bench a crucial resource for researchers seeking to comprehensively evaluate LLMs in a cost-effective manner.

Additionally, the Holistic Evaluation of Language Models (HELM) [32] focuses on transparency and the performance of models in specific tasks. The HELM adopts a multimetric approach, applying seven distinct metrics across 16 key scenarios to demonstrate the trade-offs among various models and metrics. Beyond measuring accuracy, the HELM expands its assessment to encompass fairness, bias, and toxicity. These elements are increasingly vital as LLMs enhance their ability to produce human-like text and, thus, their potential to exhibit harmful behaviors. As a dynamic benchmark, the HELM is structured to adapt continually, adding new scenarios, metrics, and models to stay current. The HELM results page provides a crucial tool for examining evaluated LLMs and their scores, helping in the selection of models that align best with specific project needs.

Furthermore, the AI2 Reasoning Challenge (ARC) established by the Allen Institute for Artificial Intelligence represents a significant benchmark aimed at assessing AI systems’ capacity for complex reasoning [35]. This benchmark consists of multiple-choice questions that, while straightforward for human children, present a considerable challenge for AI. The questions necessitate a blend of reasoning, knowledge, and language understanding. The ARC is divided into two sets of questions: an Easy Set, which can be addressed through basic retrieval methods, and a Challenge Set, requiring advanced reasoning skills beyond mere information retrieval. This division pushes AI capabilities towards a deeper knowledge-based understanding.

In addition to these benchmarks, researchers have created several datasets specifically designed to challenge LLMs, such as HellaSwag [37] and TruthfulQA [38]. HellaSwag aims to test AI’s common sense reasoning capabilities within the realm of natural language processing. As an evolution of the SWAG dataset, HellaSwag introduces more complex scenarios with multiple-choice questions, compelling AI to select the most plausible continuation from four options based on the given context. Its emphasis on adversarial examples seeks to push language models beyond statistical pattern recognition, towards a better grasp of common sense and causality [37]. Conversely, TruthfulQA is a dataset that focuses on evaluating the factual accuracy and truthfulness of responses generated by AI language models. It comprises questions that are designed to have clear, correct answers, challenging the models to prioritize truth and accuracy in their outputs. This focus is instrumental in enhancing the reliability of AI systems in delivering factually correct information [38].

In the broader AI community, companies such as HuggingFace, StreamLit, and Tokala have begun to provide leaderboards that facilitate the public comparison of LLMs using the aforementioned evaluation metrics and datasets. These leaderboards serve as essential tools for benchmarking and comparing the capabilities of various LLMs, providing insight into their performance and areas of improvement [39,40,41].

2.3. Games as a Tool for Benchmarking Large Language Models

The benchmarks previously mentioned for evaluating large language models (LLMs), such as GLUE, SuperGLUE [31], HELM [32], MMLU [34], and BIG-bench [35], primarily focus on a diverse array of language understanding tasks. These tasks range from sentiment analysis, question-answering, and reasoning to comprehension and assessments of subject-specific knowledge. Notably, these benchmarks do not typically incorporate traditional “games” into their evaluation frameworks, which contrasts with other methods of AI assessment. However, we need to recognize that within benchmarks like BIG-bench, certain tasks may incorporate elements reminiscent of games or necessitate problem-solving skills akin to those utilized in gaming contexts. Such tasks could involve logical reasoning, an understanding of rules, or puzzle-solving attributes that are inherently game-like. Despite this, these benchmarks do not engage LLMs in conventional games, such as chess or go, which might be beneficial in evaluating AI models’ strategic thinking and decision-making ability. Rather, the focus of these benchmarks lies in gauging the linguistic and cognitive capacity of LLMs across varied scenarios.

Employing games as a benchmarking tool for large language models offers a unique lens through which to assess and understand their capabilities. In gaming scenarios, an LLM’s proficiency in comprehending rules, formulating strategies, and executing decisions is brought to the forefront. This is particularly evident in strategic games like chess or go, where predicting an opponent’s moves is essential. Moreover, games requiring linguistic interaction or dialogue further challenge an LLM’s mastery over language and tests its ability to understand context. The dynamic and often unpredictable nature of many games provides an excellent platform for observing LLMs’ adaptability and learning ability. This environment allows for the examination of how these models adjust their strategies in response to changing game states, showcasing their potential for real-time learning and adaptation.

Furthermore, the utilization of LLMs within gaming contexts acts as a practical test for their capacity to generalize knowledge and skills across domains, a principle known as transfer learning [42]. Assessing an LLM’s ability to apply its learnings from general datasets to specialized tasks, such as game playing, is essential for understanding the breadth and depth of its applicability and intelligence.

Furthermore, engaging in game playing offers a standardized framework for benchmarking, facilitating the direct comparison of various LLMs’ performances under the same conditions. This approach not only provides a platform to evaluate the models’ strategic and creative problem-solving abilities but also in scenarios that demand innovative solutions.

One pivotal advantage of using games as a benchmarking tool is the controlled environment they provide. This controlled setting is instrumental for safely testing LLMs, allowing researchers to observe their behaviors in a contained manner. Such observations are valuable for predicting and mitigating potential risks or ethical concerns that might arise in real-world applications. Furthermore, games that incorporate human–AI interaction are particularly insightful, as they unveil how LLMs collaborate with or compete against humans. This sheds light on the dynamics of human–AI relationships, offering a glimpse into the potential for future applications where such interactions are central.

Therefore, the significance of testing LLMs within the gaming domain extends beyond merely evaluating their ability to play games. It encompasses a broad examination of their capabilities, including strategic thinking, language processing, creativity, and adaptability. Gaining a comprehensive understanding of these aspects is vital for propelling AI research forward and ensuring the responsible development and deployment of these technologies.

2.4. Related Work on Utilizing Games for Evaluating LLMs

In the realm of benchmarking large language models (LLMs), text-based games emerge as a distinctive and challenging domain. These games, which embody a unique blend of interactive fiction, demand that models exhibit a nuanced understanding of natural language, accurately interpret the evolving state of the game, and generate suitable commands to navigate through narrative-driven environments. Such interactions require LLMs to act as agents within complex settings where the narrative and state of the game are both described and influenced through natural language inputs. This necessitates not only a profound grasp of language and context but also the strategic application of this understanding to progress within the game. This approach underscores the potential of text-based games as a rigorous benchmark for evaluating the depth of LLMs’ language comprehension, contextual awareness, and strategic thinking capabilities [15].

Recent studies that utilized games to evaluate large language models (LLMs) have highlighted both the progress and limitations of current AI systems in complex interactive environments. A pivotal study on the performance of models such as FLAN-T5, Turing, and OPT in a text-based game titled “Detective” revealed that, despite their advanced capabilities, these LLMs still do not achieve state-of-the-art or human performance levels in text-based games [43]. This performance gap is attributed to several factors, including the inherent challenges of adapting TBGs for LLMs, the models’ difficulties in learning from past interactions, a lack of memory, and a tendency to rely on statistical prediction rather than goal-oriented processing. These findings underscore the need for enhancing LLMs’ interactive and cognitive abilities, particularly in effectively integrating and applying knowledge from past interactions toward achieving specific objectives [43].

The “GameEval-Evaluating LLMs on Conversational Games” paper introduces a novel framework for evaluating LLMs using goal-driven conversational games. This method assesses LLMs’ abilities in complex discussions, decision-making, and problem-solving within various game contexts, demonstrating the effectiveness of GameEval in distinguishing the capabilities of different LLMs. This approach represents a significant advancement in evaluating LLMs, offering a nuanced understanding of their performance and setting the stage for further development [44]. The SmartPlay benchmark, introduced by Wu, Tang, Mitchell, and Li (2023), offers a comprehensive method for assessing LLMs beyond traditional language tasks by incorporating a diverse array of games. This benchmark challenges LLMs to act as intelligent agents in varied and complex environments, emphasizing the need for LLMs to evolve into more adept agents capable of real-world interaction [45]. Gong, Huang, Ma, Vo, Durante, Noda, and Gao’s (2023) work on the MindAgent infrastructure marks a significant advancement in evaluating LLMs for multi-agent collaboration within gaming contexts. By leveraging existing gaming frameworks, MindAgent assesses LLMs’ planning and coordination capabilities, demonstrating its effectiveness in enhancing human–AI collaboration [46]. Research on LLMs’ behavior in social interaction games, such as the iterated Prisoner’s Dilemma and the Battle of the Sexes, highlights the challenges LLMs face in adapting to strategies requiring mutual understanding and flexibility [47]. Lorè and Heydari (2023) in their study on the “Strategic Behavior of Large Language Models” reveal how LLMs’ decisions are influenced by contextual framing and game structure. This research highlights the significant role of context in strategic decision-making and suggests the variability in LLMs’ effectiveness across different strategic environments [48]. Tsai, Zhou, Liu, Li, Yu, and Mei (2023) examine the ability of LLMs like ChatGPT and GPT-4 to play text-based games, identifying significant limitations in constructing world models and leveraging pre-existing knowledge. Their study suggests using text games as a benchmark for assessing LLMs, highlighting the potential for future improvements in AI through the development of targeted benchmarks [49].

Moreover, “Can Large Language Models Serve as Rational Players in Game Theory?” critically evaluates the potential of LLMs in mimicking human rationality in game theory contexts, identifying significant gaps in LLMs’ capabilities and underscoring the nascent stage of integrating LLMs into game theory [50].

Finally, a recent study explores how models like Claude 2, GPT-3.5, and GPT-4 process game strategy and spatial information via the Tic-Tac-Toe game. Key findings include Claude 2’s superior ability to identify winning moves, though this skill did not directly correlate with overall game success. This suggests that recognizing strategic moves is important but not the sole factor in winning. The study also highlights the significant impact of prompt design on LLMs’ game performance, pointing to the intricate ways AI models interact with spatial and strategic challenges [51].

These studies together enhance our grasp of LLMs’ abilities and shortcomings in gaming and interactive contexts, laying the groundwork for further investigations aimed at improving their performance and cognitive skills in intricate settings. They underline the value of using games as benchmarks to reveal the capabilities and limits of present AI systems, setting the stage for the development of advanced models proficient in sophisticated reasoning and strategic thinking.

2.5. Tic-Tac-Toe Game and Its Use for Benchmarking AI and Large Language Models

Tic-Tac-Toe, also familiar to many as Noughts and Crosses, is a classic two-player game played on a simple 3 × 3 grid. In this game, players alternate turns to mark a space in the grid with their assigned symbols: the first player with ‘X’ and the second with ‘O’. A player wins by being the first to obtain three of their symbols aligned horizontally, vertically, or diagonally. Should all nine squares be filled without any player achieving this alignment, the game results in a draw [52]. The game can be adapted to larger grids of any size n, with the winning condition adjusted to require a player to align n consecutive symbols for victory.

Tic-Tac-Toe, classified as a “solved” game, demonstrates that optimal play from both participants guarantees a predictable draw, due to its well-documented best moves for any given situation. This predictability reflects the game’s limited complexity and finite outcomes, making it a prime example for teaching strategic thinking and decision-making in a clear, manageable framework.

There are algorithms, such as the minimax algorithm, specifically designed to execute flawless Tic-Tac-Toe strategies, guaranteeing optimal play. The minimax algorithm is a strategic tool employed in game theory, applicable in two-player zero-sum games including chess and Tic-Tac-Toe [53]. This algorithm operates by evaluating potential moves in a game tree to a certain depth, alternating between maximizing and minimizing the potential outcomes. It assesses terminal nodes in the game tree using a heuristic function to score the states of the game. These scores are then backpropagated to ascertain the best possible move for the player, presuming that the opponent also plays optimally. While highly effective, the minimax algorithm can be computationally demanding, and it is often enhanced with techniques such as alpha–beta pruning to optimize performance.

Tic-Tac-Toe stands as an ideal model for introducing and investigating core AI concepts, thanks to its simple rule set and the limited array of possible outcomes. There are several implementations of Tic-Tac-Toe where a deep learning model was trained to play against a human opponent [54,55,56].

Using the Tic-Tac-Toe game for testing large language models (LLMs) provides a straightforward benchmark due to its simple rules and finite outcomes, which helps in understanding how LLMs process rules and make decisions. Its simplicity aids in analyzing and explaining AI’s decision-making process, thus contributing to the development of more transparent and understandable AI systems. Despite its simplicity, Tic-Tac-Toe allows for the evaluation of the basic strategic thinking and planning capabilities of LLMs, including how they anticipate and react to an opponent’s moves. For example, analyzing the moves made by an LLM can reveal whether it has strategically maneuvered to prevent the opponent’s victory.

Benchmarking using the Tic-Tac-Toe game can also offer insights into the LLMs’ ability to recognize patterns and sequences, which is crucial for more complex problem-solving and learning tasks. The turn-based nature of the game can test the LLMs’ responsiveness to dynamic changes, simulating interaction with users or other AI agents. Testing with Tic-Tac-Toe can reveal how effectively LLMs understand and follow specific directives, highlighting an essential aspect of AI functionality.

Additionally, the controlled environment allows for observing how LLMs can detect and correct errors, providing insights into their self-evaluation mechanisms. Overall, Tic-Tac-Toe serves as a useful tool for assessing fundamental aspects of LLM capabilities, such as rule adherence, decision-making, and basic strategic planning, within a simple and controlled setting.

3. Methodology

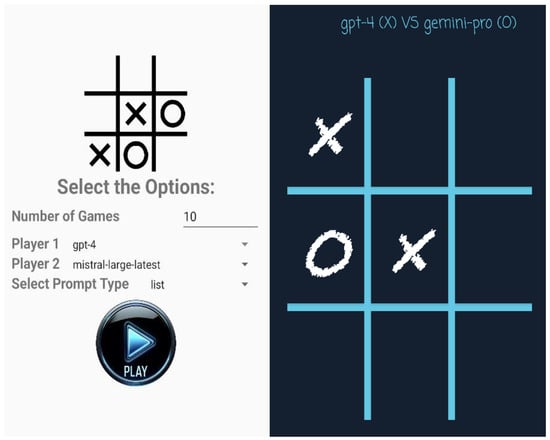

In this study, we developed a mobile Android app in the Android Studio (version Giraffe 2022.3.1) environment to facilitate Tic-Tac-Toe gameplay and data recording for large language models (LLMs). This app allows LLMs to compete against each other or play solo by simulating both players, and it records the details of each LLM’s moves for further analysis. As illustrated in Figure 1, the app’s user interface lets the user select LLMs for both Player 1 (X) and Player 2 (O) from a curated list. Users can also choose the type of predefined prompts (i.e., list or draw) and specify the desired number of consecutive games.

Figure 1.

(Left) the screen to select the number of games, players, and the prompt type. (Right) the screen displays how the game progresses.

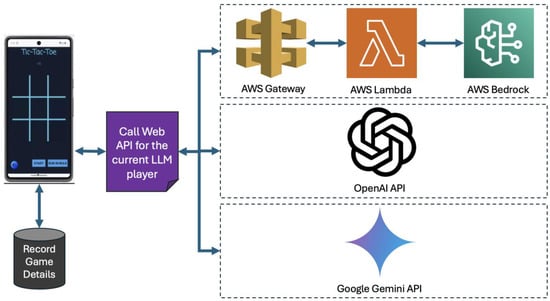

The gameplay begins with the app sending the selected prompt to the web API of the chosen LLM for Player 1, awaiting its move. Upon receiving a response, the app updates the Tic-Tac-Toe grid displayed on the screen as shown in Figure 1 and proceeds to query the next LLM for Player 2’s move. The query for the next move is sent via prompts that include the current state of the game. The queries and responses are recorded for each move. This loop continues until a player aligns three symbols and wins or the grid fills up, indicating a draw. The methodology ensures a seamless interaction between the app and LLMs via web API calls, facilitating an in-depth analysis of the LLMs’ strategic gaming capabilities. The illustration of these interactions is depicted in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The illustration of app and web service interactions to play Tic-Tac-Toe.

There are numerous large language models (LLMs) available for evaluation through games like Tic-Tac-Toe. To ensure a meaningful and comprehensive assessment, we have carefully selected the LLMs for testing based on several criteria. Firstly, we prioritized well-known, high-performing LLMs developed by industry leaders such as OpenAI, Google, and Meta, given their significant contributions to advancements in AI. Additionally, we included LLMs from emerging startup companies that have garnered attention in the AI community, especially those founded by researchers with a history at OpenAI, Google, and Meta such as Anthropic and Mistral AI. To further enrich our evaluation, we aimed to test a good mixture of open-source and closed-source LLMs, recognizing the unique strengths and contributions of each model to the AI field. This selection allows us to cover a broad spectrum of innovative approaches, technological capabilities, and accessibility options.

We incorporated a diverse array of large language models (LLMs), including AI21’s ‘Jurassic2-Ultra’, Anthropic’s ‘Claude-V2.1’, Google’s ‘Gemini-Pro’, Mistral’s ‘Mistral-Large’, Meta’s ‘Llama-2-70B-Chat’, and OpenAI’s ‘GPT-4’ and ‘GPT-3.5-Turbo’. To access these models, we primarily utilized the web APIs provided by their creators. This includes OpenAI’s API for ‘GPT-4’ and ‘GPT-3.5-Turbo’ [57], Google’s Gemini API for ‘Gemini-Pro’ [58], and Mistral’s API for ‘Mistral-Large’ [59]. For accessing models such as Llama2, Jurassic-2 Ultra, and Claude 2.1, Amazon Bedrock [60] services were employed, leveraging serverless AWS Lambda functions and API Gateways as depicted in Figure 2. We also attempted to include Amazon’s Titan model which is available at Amazon Bedrock in our evaluation; however, we could not receive a response in JSON format while the response seemed meaningful in its free text form. An example response received from Amazon Titan would be “Based on the provided content, the next move for player X (first player) in the Tic-tac-toe game would be to place their symbol in the cell at row 1, column 3”.

We utilized two types of prompts. Each prompt is divided into three main parts: an introduction to the Tic-Tac-Toe game, a list of previous moves in a format explained in the prompt, and asking the player for the next move along with the description of the expected response format. The two types of prompts are the same except for the part where the current state of the game (previous moves) is given. The first prompt lists the previous moves for each player in “row, column” format. The second prompt illustrates the current state of the grid using X and O for the previous move and ‘.’ for empty cells. This standardized format ensures the consistency of the prompt during the game while allowing for dynamic updates of the game state. The two types of prompts are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

The ‘List’ and ‘Illustration’ types of prompts that are sent to the large language models to request the next move.

The same prompts were used for every LLM. However, specific formatting instructions had to be provided via the ‘system prompt’ parameter for the Llama2 model to ensure adherence to the desired output format. The system prompt was incorporated into the end of the prompts listed in Table 1 by using the [INST] tag as follows: “[INST] Suggest your next move in a concise JSON format, such as {‘row’: 1, ‘column’: 3}, without any additional commentary [/INST]”.

Beyond the prompt, LLMs utilize parameters like max tokens, temperature, top p, and frequency penalty to tailor outputs. Max tokens set the output’s length, managing its size and relevance. Temperature adjusts response variability, with higher values increasing creativity and lower values ensuring predictability. Top p (or top-k sampling) limits choices to the most probable words, ensuring a balance of creativity and coherence. Frequency penalty reduces repetition, enhancing content diversity. These parameters collectively enable the customization of LLM responses for various applications, from customer support to content creation. Except for the prompt parameter, we do not adjust the default configuration of the LLMs trusting that they have been fine-tuned by the creators of the LLMs for best performance.

Each large language model (LLM) was configured to play games not only against other LLMs but also solo. To gather statistical information about the outcomes, each game between opponents was repeated 10 times. During the Tic-Tac-Toe game sessions played through the Android app, we collected data on the gameplay and stored it in JSON, CSV, and TXT formats. Sample JSON, CSV, and TXT files are given in Appendix A.

The JSON file contains detailed information, including the date/time, players, game result, duration, and all moves—encompassing both valid and invalid attempts. An invalid move is defined as one that targets an already occupied cell in the 3 × 3 grid or when the response text is uninterpretable in determining the next move. The JSON file also includes the current status of the game sent to the LLM and the responses received from the LLM for each move. Additionally, a more streamlined summary of the game is available in a CSV file, which excludes the detailed move information. The TXT file provides a visual representation of the game moves as demonstrated. The JSON, CSV, and TXT files that were produced during this study are publicly available on GitHub [61].

4. Results

In this section, we discuss the outcomes of Tic-Tac-Toe games played among large language models (LLMs), with Table 2 showing the results for games using the ‘list’ type of prompt between each pair of LLMs. The first row names the LLM as Player 1 (X) and the first column as Player 2 (O). ‘X’ signifies the wins by Player 1, ‘O’ by Player 2, ‘D’ for draws, and ‘C’ for canceled games due to invalid moves, such as selecting an occupied cell, choosing a cell outside the grid, or responding in a non-JSON format as specified in the prompt. Each LLM pair played 10 games, with the sum of ‘X’, ‘O’, ‘D’, and ‘C’ totaling 10 for each pair.

Table 2.

A game matrix indicating the results of 10 games between each LLM pair when the ‘list’ type of prompt is used. The LLMs are Jurassic-2 (ai21.j2-ultra-v1), Claude 2.1 (anthropic.claude-v2:1), Gemini-Pro, GPT-3.5-Turbo, GPT-4, Llama2-70 (meta.llama2-70b-chat-v1), and Mistral-L (mistral-large-latest). The first row lists Player 1, and the first column lists Player 2. X indicates Player 1 wins, O indicates Player 2 wins, D indicates draws, and C indicates the number of canceled games due to invalid moves.

Table 3 details the outcomes when the ‘illustration’ type of prompt is employed. Notably, Player 1 generally secures more victories, with GPT-4 leading in wins. However, Table 3 reveals a decline in LLM performance, evidenced by an increase in canceled games, suggesting difficulties in interpreting the game’s current state through illustrated prompts. This is particularly evident for Claude 2.1 and Llama2-70, which exhibit a high number of canceled games, indicating potential challenges in understanding previous moves, leading to responses that disregard the current game status.

Table 3.

A game matrix indicating the results of 10 games between each LLM pair when the ‘illustration’ type of prompt is used. The LLMs are Jurassic-2 (ai21.j2-ultra-v1), Claude 2.1 (anthropic.claude-v2:1), Gemini-Pro, GPT-3.5-Turbo, GPT-4, Llama2-70 (meta.llama2-70b-chat-v1), and Mistral-L (mistral-large-latest). The first row lists Player 1, and the first column lists Player 2. X indicates Player 1 wins, O indicates Player 2 wins, D indicates draws, and C indicates the number of canceled games.

The first prompt provided a list of previous moves, a format most LLMs handled effectively, as shown in Table 2. The second prompt, however, presented the previous moves visually. We observed that while most LLMs performed well with the list-based prompt, only a few were able to effectively interpret and respond to the visual prompt, as shown in Table 3. This suggests that while LLMs are generally adept at processing textual information, their ability to interpret and act on visual data is less consistent and remains a significant challenge.

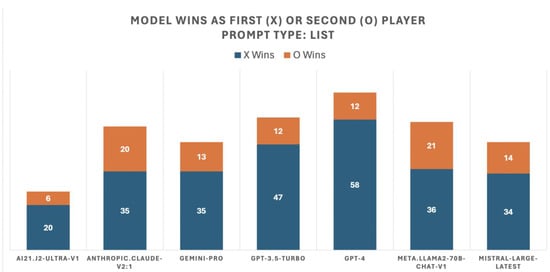

Figure 3 displays the outcomes of Tic-Tac-Toe games using the ‘list’ type of prompt, where each LLM competed against six others and itself, engaging in 10 matches per opponent for a total of 70 games. The chart uses blue bars to represent the results of games where the LLM was the first player (X) and orange bars for games where the LLM was the second player (O). Among the 490 games played, 26 ended in a draw and 101 were canceled; these are not depicted in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

This chart, based on the ‘list’ prompt, shows Tic-Tac-Toe game outcomes where each LLM faced six others and itself, playing each opponent 10 times (70 games total). Blue bars indicate the LLM playing as the first player (X) and orange bars for the second player (O).

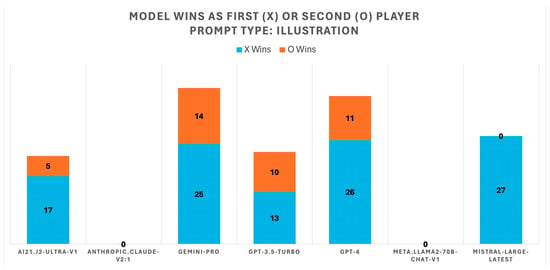

Figure 4 displays the outcomes of Tic-Tac-Toe games using the ‘illustration’ type of prompt, where each LLM competed against six others and itself, engaging in 10 matches per opponent for a total of 70 games. The chart uses blue bars to represent the results of games where the LLM was the first player (X) and orange bars for games where the LLM was the second player (O). Among the 490 games played, 4 ended in a draw and 332 were canceled; these are not depicted in Figure 4. Comparing Figure 3 and Figure 4, there is a noticeable decrease in total wins, with Claude 2.1 and Llama2-70 failing to secure any victories when the prompt depicted the game’s current state through illustrations.

Figure 4.

This chart, based on the ‘illustration’ prompt, shows Tic-Tac-Toe game outcomes where each LLM faced six others and itself, playing each opponent 10 times (70 games total). Blue bars indicate the LLM playing as the first player (X) and orange bars for the second player (O).

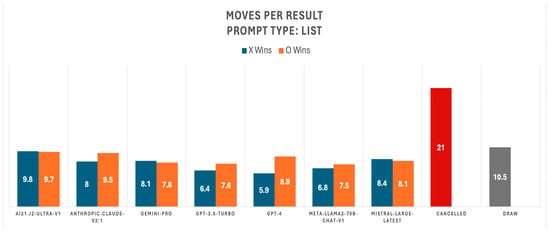

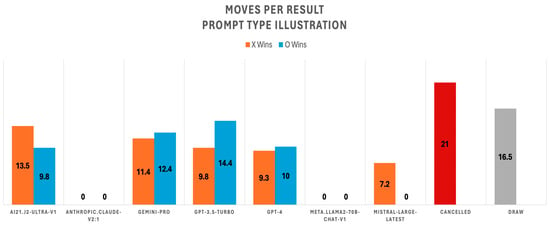

A Tic-Tac-Toe game can end in a draw after nine moves or with a win in a minimum of five moves by the first player (X) and six moves by the second player (O). Figure 5 shows the number of moves each LLM took to win as Player 1 (X) (blue bar) and as Player 2 (O) (orange bar), using a ‘list’ prompt. Winning in fewer moves indicates better decision-making by the LLM. On average, GPT-4 required 5.9 moves to win as Player 1, the best performance observed, while Jurassic-2 needed 9.8 moves, the worst performance. As Player 2, Llama2-70 averaged 7.5 moves for the best performance, and Jurassic-2 again averaged 9.7 moves, marking the worst performance. Draws averaged 10.5 moves, indicating some moves were canceled. A game is canceled after 21 moves due to excessive move cancellations. Figure 6 compares the number of moves to win under the ‘illustration’ prompt, showing longer times to win. This might indicate that LLMs had difficulty understanding the previous moves when they were presented as illustrations. Claude 2.1 and Llama2-70, with no wins, are represented with 0 moves. Mistral Large averaged the fewest moves to win as Player 1 (7.2 moves) but won no games as Player 2, as shown in Figure 6. Draws averaged 16.5 moves for the ’illustration’ type prompt, suggesting that some moves were canceled during the games.

Figure 5.

Moves per result when list type of prompt is used.

Figure 6.

Moves per result when illustration type of prompt is used.

Table 4 and Table 5 outline the invalid responses leading to canceled moves when using ‘list’- and ‘illustration’-type prompts, respectively. Table 4 reveals that the Jurassic-2 model recorded the highest number of invalid moves, predominantly due to suggesting moves to already occupied spaces. Claude 2.1’s invalid moves were primarily attributed to suggesting moves outside the permissible game area (beyond the range of 1 to 3). Gemini-Pro registered the fewest invalid moves, with only 14 instances of selecting occupied spaces. Table 5 indicates an increase in invalid moves with the ‘illustration’ prompt. Here, Claude 2.1 and Llama2-70 had the highest number of invalid responses, with GPT-4 recording the least. Similar to the ‘list’ prompt results, Claude 2.1’s main issue was suggesting moves outside the valid range, while Llama2-70 often selected spaces that were already taken. Across both prompt types, Jurassic-2 was unique in making invalid moves due to responses not being in the JSON format.

Table 4.

Number of invalid responses by LLMs using ‘List’ type prompt. This includes moves to already occupied spaces, responses in invalid formats, and moves outside permissible game area. LLMs are Jurassic-2 (ai21.j2-ultra-v1), Claude 2.1 (anthropic.claude-v2:1), Gemini-Pro, GPT-3.5-Turbo, GPT-4, Llama2-70 (meta.llama2-70b-chat-v1), and Mistral-L (mistral-large-latest).

Table 5.

Number of invalid responses by LLMs using ‘Illustration’ type prompt. This includes moves to already occupied spaces, responses in invalid formats, and moves outside permissible game area. LLMs are Jurassic-2 (ai21.j2-ultra-v1), Claude 2.1 (anthropic.claude-v2:1), Gemini-Pro, GPT-3.5-Turbo, GPT-4, Llama2-70 (meta.llama2-70b-chat-v1), and Mistral-L (mistral-large-latest).

5. Discussion

5.1. An Overview of the Results

The results from Tic-Tac-Toe games involving various large language models (LLMs) using different types of prompts reveal intriguing aspects of AI strategic gameplay and error patterns. Using the ‘list’ prompt, a clear trend was observed with GPT-4 outperforming other models, particularly when playing as the first player. However, when the ‘illustration’ prompt was introduced, there was a notable decline in LLM performance, with a significant increase in canceled games due to invalid responses, highlighting potential issues with interpreting illustrated game states.

Claude 2.1 and Llama2-70, in particular, demonstrated a high frequency of invalid moves, such as selecting occupied spaces or suggesting moves outside the game’s grid, resulting in no wins under the ‘illustration’ prompt, as shown in Figure 1 and Figure 2. This contrast in performance between prompt types suggests that the manner in which game status is conveyed plays a critical role in LLMs’ decision-making processes. Furthermore, the average number of moves taken to achieve a win varied across models, with GPT-4 showing efficiency and Jurassic-2 showing less optimal move choices.

The data from Table 4 and Table 5 support these findings, with invalid moves being more prevalent with the ‘illustration’ prompt. This indicates a broader challenge that LLMs face when processing and responding to visually complex inputs compared to more structured ‘list’ inputs. Overall, these outcomes not only benchmark current LLM capabilities in strategic gameplay but also point to specific areas for improvement, particularly in understanding and interpreting illustrated or less-structured data.

5.2. Limitations and Future Directions

Utilizing a 3 × 3 grid Tic-Tac-Toe game to test large language models (LLMs) has highlighted several limitations that could impact the findings of our study and their wider applicability. The dependence on predefined prompts for guiding the LLMs’ moves may not adequately capture their potential for independent strategic thinking or their ability to respond to changing game states. For instance, rather than repeating the same prompt following an invalid move, a custom prompt could be generated to specifically highlight the error, thereby aiding the LLM in correcting its response.

Furthermore, the two types of prompts we tested indicate that varying instructions might influence the outcomes significantly. The emerging field of ‘Prompt Engineering’ focuses on optimizing textual inputs to elicit specific responses from LLMs [62,63]. Effective prompt engineering, which combines art with science through experimentation and adaptation to the LLMs’ unique strengths and weaknesses, offers various techniques for generating diverse prompts. The effectiveness of these prompts can be further explored in future research. Future studies are suggested to delve deeper into how the structured prompts influence the LLMs’ performance and explain how variations in prompt structure might affect the LLMs’ understanding of the game state and their subsequent moves.

The simplicity of Tic-Tac-Toe, while facilitating the evaluation of LLMs on a basic level, may not challenge their strategic capabilities as more complex games like chess or go might. Despite this, the fact that current LLMs have not mastered even this simple game offers valuable insights into their current capabilities and limitations. Expanding the evaluation to larger grids, such as 4 × 4 or 5 × 5, could present additional challenges and provide a clearer indicator of LLM performance for comparison.

Moreover, our methodology’s dependence on web APIs for LLM interaction introduces challenges related to accessibility, rate limits, and latency, potentially impacting real-time performance assessment. However, our aim was not to evaluate the performance metrics of LLMs from this perspective.

The evaluation metrics utilized in this study primarily focused on win/loss/draw outcomes and included an examination of the number and types of invalid moves, as well as the count of moves required for each LLM to win. Although these metrics provide a fundamental indication of the LLMs’ performance, they may not fully capture the entire scope of the LLMs’ strategic complexity. To gain a more nuanced understanding of their strategic depth, an analysis of each move—drawn from the JSON files—could enable a more detailed assessment of their subtle strategic variations and developmental progress over time.

Additionally, concentrating on a select group of LLMs might not capture the full diversity of strategic approaches and abilities found across the wider range of available models. This highlights the importance of including a broader array of LLMs in future research. The landscape of LLMs is expanding swiftly, with new models and improved versions emerging in rapid succession. For instance, during the course of this study, newer iterations like Claude 3 and Gemini Ultra were released. Yet, our study was limited by the lack of access to these models through web APIs, preventing us from evaluating their capabilities.

Building upon the methodology and findings of this study on testing large language models (LLMs) using the Tic-Tac-Toe game, future work could explore several promising directions to extend the research and deepen our understanding of LLMs’ capabilities in strategic games and beyond. For example, multi-agent collaboration scenarios could be tested where multiple LLMs work together against a common opponent or compete against each other in teams, assessing their abilities in coordination, cooperation, and competitive strategy. Future work could compare newer versions of LLMs against the ones tested in this study to track progress and improvements in AI strategic gaming capabilities over time.

A critical area for future investigation would be to focus on the explainability of LLM decisions in games, aiming to derive insights into their strategic thinking processes. Developing methodologies to interpret and explain LLM strategies could enhance our understanding of AI decision-making. Moreover, we would gain more insights with a study that examines the ethical and social implications of deploying LLMs in strategic games and interactive environments, considering aspects like fairness, bias, and the impact of AI behaviors on human players and observers.

To benchmark LLMs, new custom, purpose-built games can be designed to test specific aspects of LLM capabilities, such as memory, learning from past moves, or adapting to unusual rules. This could allow for more targeted assessments of AI strengths and weaknesses.

6. Conclusions

This study aimed to assess the capabilities of large language models (LLMs) through the classic game of Tic-Tac-Toe. Our findings provide a nuanced understanding of the current state of LLMs, highlighting both their potential and limitations within the realm of strategic gameplay. Through the development and utilization of a mobile application and web services from the creators of the LLMs and web services we created utilizing the LLMs hosted at Amazon Bedrock, we enabled LLMs to engage in games of Tic-Tac-Toe, revealing their abilities to comprehend game rules and execute strategic moves. We have evaluated a diverse set of LLMs, including Jurassic-2 Ultra by AI21, Claude V2.1 by Anthropic, Gemini-Pro by Google, Mistral Large by Mistral, Llama2-70B by Meta, and OpenAI’s GPT-4 and GPT-3.5-Turbo.

The results from this study show that while LLMs can grasp the basic structure and rules of Tic-Tac-Toe, their performance varies significantly based on the prompts provided. The comparative analysis of results using prompts that provided the previous moves as a ‘list’ and ‘illustration’ uncovered the challenges faced by LLMs when interpreting game states from illustrated inputs. This has been exemplified by the increase in canceled games due to invalid responses under the ‘illustration’ prompt, indicating a need for the improved processing of visually complex or less-structured data.

GPT-4, GPT-3.5-Turbo, and Llama2 achieved the most wins using the list type of prompt, while GPT-4, Gemini-Pro, and Mistral Large secured the most wins with the illustration type of prompt. GPT-4 consistently won with the fewest moves, demonstrating superior performance in defeating its opponents. Upon analyzing invalid moves, it was observed that Gemini-Pro and GPT-4 committed the fewest errors with the list prompt, and GPT-4 along with GPT-3.5-Turbo made the fewest mistakes when the illustration prompt was utilized.

Our work contributes valuable insights into the field by assessing the capabilities of LLMs using a novel approach and serves as a stepping stone for future research. Future directions for this research on benchmarking large language models (LLMs) in strategic games could focus on the effects of a variety of prompts, exploring larger grid sizes of Tic-Tac-Toe and more complex games to better challenge and assess LLM strategic capabilities. Further investigation could delve into the nuanced interpretation of LLM decisions, seeking to enhance the explainability of their strategic thought processes. Broadening the range of LLMs studied would help to capture a more diverse spectrum of strategic approaches. Collaborative and competitive multi-agent scenarios could also be examined to evaluate LLM coordination and adaptation skills. Moreover, custom games tailored to probe specific AI abilities could be planned, enabling a more precise evaluation of LLMs’ strengths and potential areas for development.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, O.T.; methodology, O.T.; software, J.B.H. and O.T.; validation, O.T.; formal analysis, O.T.; investigation, O.T.; resources, O.T.; data curation, O.T.; writing—original draft preparation, O.T.; writing—review and editing, J.B.H.; visualization, O.T.; supervision, O.T.; project administration, O.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Result data and the code can be downloaded from the GitHub page: https://github.com/research-outcome/LLM-TicTacToe-Benchmark/, (accessed on 8 March 2024), Game Outputs in TXT, CSV, and JSON format as described in Appendix A.

Acknowledgments

We thank the students at Florida Polytechnic University who contributed to the initial version of the mobile app including Ashton Erkl, Brian Tran, Kaleb Walden, and Quy Pham.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Sample JSON, CSV, and TXT file containing information about the same gameplay between GPT-4 and Gemini-Pro.

Table A1.

Sample JSON, CSV, and TXT file containing information about the same gameplay between GPT-4 and Gemini-Pro.

| Sample JSON File Content: |

| { “datetime”: “240308-175045”, “player1”: “gpt-4”, “player2”: “gemini-pro”, “totalMoves”: 5, “player1MovesAlreadyTaken”: 0, “player2MovesAlreadyTaken”: 0, “player1MovesOutOfBounds”: 0, “player2MovesOutOfBounds”: 0, “player1MovesInvalidFormat”: 0, “player2MovesInvalidFormat”: 0, “result”: “gpt-4 X wins!”, “gameDuration”: “00:05”, “promptType”: “list”, “moves”: [ { “no”: 1, “player”: 1, “row”: 2, “col”: 2, “valid”: “Y”, “promptType”: “list”, “currentStatus”: “The moves by the first player (marked by X): None \nThe moves by the second player (marked by O): None \n”, “response”: “{‘row’: 2, ‘column’: 2}” }, { “no”: 2, “player”: 2, “row”: 1, “col”: 1, “valid”: “Y”, “promptType”: “list”, “currentStatus”: “The moves by the first player (marked by X): 2,2 \nThe moves by the second player (marked by O): None \n”, “response”: “{‘row’: 1, ‘column’: 1}” }, { “no”: 3, “player”: 1, “row”: 1, “col”: 2, “valid”: “Y”, “promptType”: “list”, “currentStatus”: “The moves by the first player (marked by X): 2,2 \nThe moves by the second player (marked by O): 1,1 \n”, “response”: “{‘row’: 1, ‘column’: 2}” }, { “no”: 4, “player”: 2, “row”: 3, “col”: 1, “valid”: “Y”, “promptType”: “list”, “currentStatus”: “The moves by the first player (marked by X): 1,2; 2,2 \nThe moves by the second player (marked by O): 1,1 \n”, “response”: “{‘row’: 3, ‘column’: 1}” }, { “no”: 5, “player”: 1, “row”: 3, “col”: 2, “valid”: “Y”, “promptType”: “list”, “currentStatus”: “The moves by the first player (marked by X): 1,2; 2,2 \nThe moves by the second player (marked by O): 1,1; 3,1 \n”, “response”: “{‘row’: 3, ‘column’: 2}” } ] } |

| Sample CSV file content: |

| GameTime,PromptType,Player1,Player2,Result,TotalTime,TotalMoves,Player1InvalidAlreadyTaken,Player2InvalidAlreadyTaken,Player1InvalidFormat, Player2InvalidFormat, Player1OutOfBounds, Player2OutOfBounds 240308-163604,list,gemini-pro,meta.llama2-70b-chat-v1,gemini-pro X wins!,00:12,10,0,1,0,0,0,0\ |

| Sample TXT file content: |

| Game #559 Prompt Type: list Player 1: anthropic.claude-v2:1 Player 2: gpt-4 Date Time: 240307-202522 Game Duration: 00:16 Total Moves: 9 Player 1 Already Taken Moves: 0 Player 2 Already Taken Moves: 0 Player 1 Invalid Format Moves: 0 Player 2 Invalid Format Moves: 0 Player 1 Out of Bounds Moves: 0 Player 2 Out of Bounds Moves: 0 Result: Draw Game Progress: X|.|. .|.|. .|.|. X|O|. .|.|. .|.|. X|O|. .|X|. .|.|. X|O|. .|X|. .|.|O X|O|X .|X|. .|.|O X|O|X .|X|. O|.|O X|O|X .|X|. O|X|O X|O|X .|X|O O|X|O X|O|X X|X|O O|X|O |

References

- War Games Movie. Available online: https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0086567/ (accessed on 7 March 2024).

- War of Games Movie Ending. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=s93KC4AGKnY (accessed on 7 March 2024).

- Naveed, H.; Khan, A.U.; Qiu, S.; Saqib, M.; Anwar, S.; Usman, M.; Akhtar, N.; Barnes, N.; Mian, A. A Comprehensive Overview of Large Language Models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2307.06435. [Google Scholar]

- Goertzel, B.; Pennachin, C. (Eds.) Artificial General Intelligence; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2007; Volume 2, p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J. NVIDIA CEO Predicts AGI in 5 Years. Available online: https://www.barrons.com/articles/nvidia-ceo-jensen-huang-agi-breakthrough-a7029004 (accessed on 7 March 2024).

- LeCun, Y. Meta AI Chief Skeptical about AGI, Quantum Computing. Available online: https://www.cnbc.com/2023/12/03/meta-ai-chief-yann-lecun-skeptical-about-agi-quantum-computing.html (accessed on 7 March 2024).

- Sutskever, I. The Exciting, Perilous Journey toward AGI. Available online: https://www.ted.com/talks/ilya_sutskever_the_exciting_perilous_journey_toward_agi (accessed on 7 March 2024).

- Van Houdt, G.; Mosquera, C.; Nápoles, G. A Review on the Long Short-Term Memory Model. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2020, 53, 5929–5955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivakumar, S.; Videla, L.S.; Kumar, T.R.; Nagaraj, J.; Itnal, S.; Haritha, D. Review on Word2Vec Word Embedding Neural Net. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Smart Electronics and Communication (ICOSEC), Trichy, India, 10–12 September 2020; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 282–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toshevska, M.; Stojanovska, F.; Kalajdjieski, J. Comparative Analysis of Word Embeddings for Capturing Word Similarities. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2005.03812. [Google Scholar]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention Is All You Need. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017, 30, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1810.04805. [Google Scholar]

- Radford, A.; Narasimhan, K.; Salimans, T.; Sutskever, I. Improving Language Understanding by Generative Pre-training. Available online: https://paperswithcode.com/paper/improving-language-understanding-by (accessed on 8 March 2024).

- Wu, T.; He, S.; Liu, J.; Sun, S.; Liu, K.; Han, Q.L.; Tang, Y. A Brief Overview of ChatGPT: The History, Status Quo, and Potential Future Development. IEEE/CAA J. Autom. Sinica 2023, 10, 1122–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bubeck, S.; Chandrasekaran, V.; Eldan, R.; Gehrke, J.; Horvitz, E.; Kamar, E.; Lee, P.; Lee, Y.T.; Li, Y.; Lundberg, S.; et al. Sparks of Artificial General Intelligence: Early Experiments with GPT-4. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.12712. [Google Scholar]

- Team, G.; Anil, R.; Borgeaud, S.; Wu, Y.; Alayrac, J.B.; Yu, J.; Soricut, R.; Schalkwyk, J.; Dai, A.M.; Hauth, A.; et al. Gemini: A Family of Highly Capable Multimodal Models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2312.11805. [Google Scholar]

- Anthropic. Model Card and Evaluations for Claude Models. Available online: https://www-files.anthropic.com/production/images/Model-Card-Claude-2.pdf (accessed on 7 February 2024).

- AI21. Jurassic 2 Models. Available online: https://docs.ai21.com/docs/jurassic-2-models (accessed on 7 February 2023).

- Touvron, H.; Lavril, T.; Izacard, G.; Martinet, X.; Lachaux, M.-A.; Lacroix, T.; Rozière, B.; Goyal, N.; Hambro, E.; Azhar, F.; et al. LLaMA: Open and Efficient Foundation Language Models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2302.13971. [Google Scholar]

- Touvron, H.; Martin, L.; Stone, K.; Albert, P.; Almahairi, A.; Babaei, Y.; Bashlykov, N.; Batra, S.; Bhargava, P.; Bhosale, S.; et al. Llama 2: Open Foundation and Fine-Tuned Chat Models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2307.09288. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, A.Q.; Sablayrolles, A.; Mensch, A.; Bamford, C.; Chaplot, D.S.; de las Casas, D.; Bressand, F.; Lengyel, G.; Lample, G.; Saulnier, L.; et al. Mistral 7B. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2310.06825. [Google Scholar]

- Kaddour, J.; Harris, J.; Mozes, M.; Bradley, H.; Raileanu, R.; McHardy, R. Challenges and Applications of Large Language Models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2307.10169. [Google Scholar]

- Thirunavukarasu, A.J.; Ting, D.S.J.; Elangovan, K.; Gutierrez, L.; Tan, T.F.; Ting, D.S.W. Large Language Models in Medicine. Nat. Med. 2023, 29, 1930–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Stevens, N.; Han, S.C.; Song, M. A Survey of Large Language Models in Finance (FinLLMs). arXiv 2024, arXiv:2402.02315. [Google Scholar]

- Kasneci, E.; Seßler, K.; Küchemann, S.; Bannert, M.; Dementieva, D.; Fischer, F.; Kasneci, G. ChatGPT for Good? On Opportunities and Challenges of Large Language Models for Education. Learning Individ. Differ. 2023, 103, 102274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topsakal, O.; Topsakal, E. Framework for A Foreign Language Teaching Software for Children Utilizing AR, Voicebots and ChatGPT (Large Language Models). J. Cogn. Syst. 2022, 7, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topsakal, O.; Akinci, T.C. Creating Large Language Model Applications Utilizing LangChain: A Primer on Developing LLM Apps Fast. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Applied Engineering and Natural Sciences, Konya, Turkey, 10–12 July 2023; Volume 1, pp. 1050–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minaee, S.; Mikolov, T.; Nikzad, N.; Chenaghlu, M.; Socher, R.; Amatriain, X.; Gao, J. Large Language Models: A Survey. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2402.06196. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, J.; Wu, Y.; Yang, L.; Zhu, K.; Chen, H.; Yi, X.; Wang, C.; Wang, Y.; et al. A Survey on Evaluation of Large Language Models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2307.03109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.; Singh, A.; Michael, J.; Hill, F.; Levy, O.; Bowman, S.R. GLUE: A Multi-Task Benchmark and Analysis Platform for Natural Language Understanding. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1804.07461. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, A.; Pruksachatkun, Y.; Nangia, N.; Singh, A.; Michael, J.; Hill, F.; Levy, O.; Bowman, S.R. SuperGLUE: A Stickier Benchmark for General-Purpose Language Understanding Systems. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1905.00537. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, P.; Bommasani, R.; Lee, T.; Tsipras, D.; Soylu, D.; Yasunaga, M.; Zhang, Y.; Narayanan, D.; Wu, Y.; Kumar, A.; et al. Holistic Evaluation of Language Models. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2211.09110. [Google Scholar]

- Hendrycks, D.; Burns, C.; Basart, S.; Zou, A.; Mazeika, M.; Song, D.; Steinhardt, J. Measuring Massive Multitask Language Understanding. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2009.03300. [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava, A.; Rastogi, A.; Rao, A.; Shoeb, A.A.M.; Abid, A.; Fisch, A.; Brown, A.R.; Santoro, A.; Gupta, A.; Garriga-Alonso, A.; et al. Beyond the Imitation Game: Quantifying and Extrapolating the Capabilities of Language Models. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2206.04615. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, P.; Cowhey, I.; Etzioni, O.; Khot, T.; Sabharwal, A.; Schoenick, C.; Tafjord, O. Think You Have Solved Question Answering? Try ARC, the AI2 Reasoning Challenge. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1803.05457. [Google Scholar]

- SuperGLUE Leaderboard. Available online: https://super.gluebenchmark.com/leaderboard/ (accessed on 8 March 2024).

- Zellers, R.; Holtzman, A.; Bisk, Y.; Farhadi, A.; Choi, Y. HellaSwag: Can a Machine Really Finish Your Sentence? In Proceedings of the 57th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Florence, Italy, 28 July–2 August 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, S.; Hilton, J.; Evans, O. TruthfulQA: Measuring How Models Mimic Human Falsehoods. In Proceedings of the 60th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Dublin, Ireland, 22–27 May 2022; Volume 1: Long Papers, pp. 3214–3252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HuggingFace LLM Leaderboard. Available online: https://huggingface.co/spaces/HuggingFaceH4/open_llm_leaderboard (accessed on 15 January 2024).

- StreamLit LLM Leaderboard. Available online: https://llm-leaderboard.streamlit.app (accessed on 15 January 2024).

- Tokala LLM Leaderboard. Available online: https://toloka.ai/llm-leaderboard/ (accessed on 15 January 2024).

- Topsakal, O.; Akinci, T.C. A Review of Transfer Learning: Advantages, Strategies, and Types. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Modern and Advanced Research, Konya, Turkey, 29–31 July 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, Q.; Kazemi, A.; Mihalcea, R. Text-Based Games as a Challenging Benchmark for Large Language Models. Available online: https://openreview.net/forum?id=2g4m5S_knF (accessed on 8 March 2024).

- Qiao, D.; Wu, C.; Liang, Y.; Li, J.; Duan, N. GameEval: Evaluating LLMs on Conversational Games. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2308.10032. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.; Tang, X.; Mitchell, T.M.; Li, Y. SmartPlay: A Benchmark for LLMs as Intelligent Agents. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2310.01557. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, R.; Huang, Q.; Ma, X.; Vo, H.; Durante, Z.; Noda, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Zhu, S.-C.; Terzopoulos, D.; Fei-Fei, L.; et al. Mindagent: Emergent Gaming Interaction. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2309.09971. [Google Scholar]

- Akata, E.; Schulz, L.; Coda-Forno, J.; Oh, S.J.; Bethge, M.; Schulz, E. Playing Repeated Games with Large Language Models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2305.16867. [Google Scholar]

- Lorè, N.; Heydari, B. Strategic Behavior of Large Language Models: Game Structure vs. Contextual Framing. SSRN Electron. J. September 2023. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4569717 (accessed on 8 March 2024).

- Tsai, C.F.; Zhou, X.; Liu, S.S.; Li, J.; Yu, M.; Mei, H. Can Large Language Models Play Text Games Well? Current State-of-the-Art and Open Questions. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2304.02868. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, C.; Chen, J.; Jin, Y.; He, H. Can Large Language Models Serve as Rational Players in Game Theory? A Systematic Analysis. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2312.05488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liga, D.; Pasetto, L. Testing Spatial Reasoning of Large Language Models: The Case of Tic-Tac-Toe. In Proceedings of the 1st Workshop on Artificial Intelligence for Perception and Artificial Consciousness (AIxPAC 2023) Co-Located with the 22nd International Conference of the Italian Association for Artificial Intelligence (AIxIA 2023), Roma, Italy, 8 November 2023; pp. 64–79. [Google Scholar]

- Tic Tac Toe Game. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tic-tac-toe (accessed on 11 January 2024).

- Savelli, R.M.; de Beauclair Seixas, R. Tic-Tac-Toe and the Minimax Decision Algorithm. In Lua Programming Gems; Luiz, H.d.F., Waldemar, C., ve Roberto, L., Eds.; 2008; pp. 239–245. Available online: https://www.lua.org/gems/ (accessed on 11 January 2024).

- GantMan. Tic Tac Toe Tensorflow Web Game. Available online: https://github.com/GantMan/tictactoe-ai-tfjs (accessed on 11 January 2024).

- Tic-Tac-Toe against an, AI. Available online: https://data.bangtech.com/algorithm/tic-tac-toe.htm (accessed on 11 January 2024).

- AaronCCWong. Tic-Tac-Toe vs AI. Available online: https://github.com/AaronCCWong/portfolio (accessed on 11 January 2024).

- OpenAI API. Available online: https://platform.openai.com/ (accessed on 18 January 2024).

- Google AI Gemini API. Available online: https://ai.google.dev/tutorials/android_quickstart (accessed on 18 January 2024).

- Mistral AI API. Available online: https://docs.mistral.ai/ (accessed on 18 January 2024).

- Amazon Bedrock Generative, AI. Available online: https://aws.amazon.com/bedrock/ (accessed on 7 March 2024).

- LLM TicTactToe Benchmark Outputs. Available online: https://github.com/research-outcome/LLM-TicTacToe-Benchmark/ (accessed on 12 March 2024).

- Amazon Web Services. Prompt Engineering. Available online: https://docs.aws.amazon.com/bedrock/latest/userguide/prompt-engineering-guidelines.html (accessed on 11 February 2024).

- Prompt Engineering Guide. Available online: https://www.promptingguide.ai/ (accessed on 11 February 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).