Abstract

In recent years, computer vision tasks have gained a lot of popularity, accompanied by the development of numerous powerful architectures consistently delivering outstanding results when applied to well-annotated datasets. However, acquiring a high-quality dataset remains a challenge, particularly in sensitive domains like medical imaging, where expense and ethical concerns represent a challenge. Generative adversarial networks (GANs) offer a possible solution to artificially expand datasets, providing a basic resource for applications requiring large and diverse data. This work presents a thorough review and comparative analysis of the most promising GAN architectures. This review is intended to serve as a valuable reference for selecting the most suitable architecture for diverse projects, diminishing the challenges posed by limited and constrained datasets. Furthermore, we developed practical experimentation, focusing on the augmentation of a medical dataset derived from a colonoscopy video. We also applied one of the GAN architectures outlined in our work to a dataset consisting of histopathology images. The goal was to illustrate how GANs can enhance and augment datasets, showcasing their potential to improve overall data quality. Through this research, we aim to contribute to the broader understanding and application of GANs in scenarios where dataset scarcity poses a significant obstacle, particularly in medical imaging applications.

1. Introduction

It is largely acknowledged that generative adversarial networks (GANs) [1] were a major breakthrough in the field of artificial intelligence. The idea behind GAN was first introduced in 2014 by Ian J. Goodfellow and his team and years later it remains one of the most relevant and promising methods used to tackle generative problems in computer vision and many other fields. GANs are great for generating all sorts of data, not only images. It is also used for generating text, tabular data, music and audio, 3D models, etc. It is also the first architecture developed in the field of Deep Learning that was able to produce such high quality results on most datasets they were trained on, no matter the domain. In this work, we will provide a comprehensive overview of the most widely recognized and commonly used advancements and approaches that have emerged since the inception of the GAN framework.

The GAN is composed of two parts: the generator and the discriminator. The generator generates new instances of data. The discriminator evaluates the authenticity of the generated data. At the beginning of the training the generator will not produce good images, but the discriminator will give feedback to the generator and it will improve. In order to be able to evaluate the authenticity of the generated data, the discriminator is trained on real data. Then, the discriminator receives the image from the generator, and it assigns a probability of the generated image being real. Basically, the discriminator is a standard CNN used for classification, it checks if the generated data falls into the real or fake category. The way the generator works is opposite to the discriminator. The discriminator downsamples the image in order to obtain that probability, meanwhile, the generator takes its input and upsamples it as much as possible to become a good enough piece of data. Both networks try to optimize their specific loss function. During the training process, both networks change and influence one another. Hence the name “Adversarial”, the networks compete in fooling each other. The final goal is to make a generator good enough to approximate its generated distribution to the distribution of the real images. The original paper shows results for the MNIST dataset [2] and CIFAR-10 [3], both of which consist of simple images. MNIST is a dataset that contains 60,000 small images with handwritten digits. The size of each image is 28 × 28 pixels, the digit itself is white and the background is black. Since the image is so small and contains only two colors, the authors of the paper [1] used noise as input for the generator Network. Using random noise as input for the generator of a GAN is a common way to generate data. However, depending on the complexity and specificity of more advanced tasks, a more sophisticated approach may be necessary [1].

For some scenarios, using random noise can be sufficient. The GAN Generator will take this noise and generate corresponding synthetic data. However, there are situations where it is necessary to provide more meaningful or structured inputs to the generator. For example, when generating realistic images, adding random noise can lead to inconsistent or blurry results. Instead, it may be beneficial to provide the generator with a latent vector. We will explore the various inputs used for the generator in the specialized literature.

The pioneers of generative models were hidden Markov models (HMMs) and Gaussian mixture models (GMMs). In the 1950s, they were developed to produce sequential pieces of data. In the field of natural language processing (NLP), recurrent neural networks (RNNs) alongside long short-term memory (LSTM) were a breakthrough and were able to model longer dependencies, allowing for longer sentence generation. In 2013, the variational autoencoder (VAE) was introduced, but its disadvantage compared to the GAN is that it produces blurred and unclear images. The focus of this paper, the GAN, was introduced in 2014 and was a breakthrough because it could generate high-quality images. In 2015, diffusion models were introduced [4]. The basic principle of diffusion models is incorporating noise into the existing training data and then reversing the process to restore the data. In 2017, transformers were proposed, first with applications in NLP and later with applications in computer vision as well. In 2021, stable diffusion was introduced, and it is an important model for text-to-image translation [5]. In this work, we will keep our focus on GANs and their evolution with the purpose of providing a strong technical and practical guide for future research in this field.

The focus of this paper is on how GANs can be used to solve medical data related problems; however, it’s important to mention that GANs have proven to be versatile and powerful tools in various domains like image/video editing [6], generating original data for entertainment industry, image-to-image translation, text-to-image translation, image/video quality enhancer, face aging [7], and human pose generation [8] for security applications. In the software industry for editing photos and videos, GANs can be used to improve the resolution of older images or those taken from a very far distance, such as images from space. Style transfer methods can be employed to create new scenarios. There are GANs specifically developed for video editing effects, like changing the background or adding/removing objects from a frame. In the entertainment industry, GANs can be utilized for the automatic generation of characters or backgrounds [9]. Additionally, we can transform simple sketches into more detailed objects and use them in design related productions (cartoons, games, etc.). For this industry, GANs that generate images based on text can be helpful, rapidly creating characters or objects suitable for the intended scene. Generating the appearances of specific individuals based on age and body pose can be useful in security-related issues. As we’ll see in the next section, we can use the discriminator for one-class classification problems. For instance, in cases of banking fraud, where most transactions in existing datasets are valid, the discriminator can be very useful in identifying transactions that stand out and fit into the category of fraudulent transactions [10].

2. Related Work

2.1. DCGAN—Deep Convolutional GAN

The idea of a deep convolutional GAN was introduced one year after the publication of the original GAN idea. It is similar to the original GAN, but it introduces the use of a deep convolutional network instead of a fully connected network. As mentioned before, CNNs are great when working with images because they look better for spatial correlations. This is making the DCGAN a better option to use when generating images compared to the original GAN [11].

2.2. WGAN—Wasserstein GAN

WGAN was introduced in 2017 and received its name from the Wasserstein loss that it is using. They propose the use of the Wasserstein distance (the effort that it takes to transform one distribution into another) instead of the Jensen–Shannon divergence to compare the distributions of the generated data and the training data. The authors call the discriminator a “critic”. WGAN uses weight clipping in order to enforce the 1-Lipschitz constraint. To ensure the validity of the Wasserstein distance calculation, WGAN enforces the 1-Lipschitz constraint on the critic (also known as the discriminator in a GAN). The Lipschitz constraint ensures that the critic’s output does not change dramatically with small changes in the input. This constraint helps stabilize the training process and improves the quality of the generated samples. The critic must satisfy the Lipschitz constraint. To enforce the 1-Lipschitz constraint, WGAN uses weight clipping. Weight clipping involves limiting the values of the weights in the critic to a predefined range, typically by setting a threshold. This prevents the weights from growing too large and helps ensure that the critic’s output remains within a reasonable range. However, it’s worth noting that weight clipping has some limitations and can lead to issues. Overall, the 1-Lipschitz constraint, enforced through weight clipping in WGAN, is a technique used to stabilize the training process and improve the convergence of the Wasserstein GAN model. The authors of the work in [12] emphasize that by using this loss, they obtained better stability in training and that it solves common problems like vanishing gradients and mode collapse.

Mode collapse in generative adversarial networks (GANs) refers to a situation where the generator of the GAN fails to capture the full diversity of the true data distribution and instead produces limited variations or replicates a few specific modes of the data. In other words, mode collapse occurs when the generator generates similar or identical samples, regardless of the diversity present in the training data. For example, for the MNIST dataset, which contains digits from 0 to 9, the generator tends to produce digits from only two classes: 1 and 8. Mode collapse can be problematic because it leads to a lack of diversity in the generated samples. Instead of capturing the full complexity and variation of the real data distribution, the generator may focus on a subset of modes or produce repetitive outputs. This can result in low-quality or unrealistic generated samples that do not represent the full range of the desired data distribution. Because the generator is overfitting, the discriminator does not improve, so the generated data remains limited to a small number of classes.

Vanishing gradients can hinder the training process and lead to slow convergence or poor performance in GANs. When the discriminator is too good, the generator does not have any chance to improve. When the gradients are too small, they do not provide sufficient information to guide the generator in improving its generated samples. As a result, the generator may struggle to learn and adapt effectively to produce better-quality samples. The vanishing gradient problem is particularly challenging in GANs, because of the adversarial nature of the training. The generator and discriminator constantly try to outperform each other, and if the discriminator’s gradients diminish, the generator’s updates become less informative and effective.

Wasserstein loss tackles both problems. If the critic is not getting stuck in local minimum, it is forcing the generator to try something new when it is stabilizing and returning outputs from only a few classes. Also, Wasserstein loss is a good indicator for the quality of the image. As the number of epochs increases, the value of the loss function decreases, proving a better alignment of the generated distribution to the original one used for training.

The Critic maximizes this difference, while the target of the generator is to minimize it. The lower the difference, the better the quality of the generated data.

The downside of the WGAN and Lipschitz Constraint is that the quality of the output is very dependent on the hyperparameter c used in weight clipping. In the context of weight clipping in Wasserstein GAN, the hyperparameter “c” represents the threshold or maximum value to which the weights of the critic (discriminator) network are clipped. Setting “c” too small can lead to gradient vanishing or hinder the learning process, while setting it too large may result in weak enforcement of the Lipschitz constraint, allowing the critic to produce unstable or inaccurate gradients. Finding the optimal value for “c” often requires experimentation and empirical observation to strike a balance between stability and effective training in WGAN [12].

To overcome this problem, [13] proposed the use of a gradient penalty. In WGAN, the gradient penalty is applied by adding a regularization term to the loss function. The regularization term encourages the gradients of the critic’s output with respect to the input samples to have a consistent and controlled magnitude. Specifically, during training, random interpolations are generated between pairs of real and generated samples. These interpolations are used to calculate the gradients of the critic’s output, with respect to the interpolated points. The gradient penalty term is then computed as the norm (e.g., L2 norm) of these gradients. The objective is to encourage the gradients to have a magnitude of 1, indicating Lipschitz continuity [13].

2.3. cGAN—Conditional GAN

cGAN was introduced in order to control the type of image that we want to generate. For example, for the MNIST dataset we cannot control the generation of a specific digit with the methods presented so far. cGAN emerged as a solution to address the challenge of understanding the connection between the random input provided to the generator and the actual characteristics present in the training images. Without this, we would not be able to influence specific features that would generate a specific result.

In conditional GAN architecture, we will provide both the generator and the discriminator with some additional information to generate images of specific classes. Compared to the original GAN, we provide some additional information for the generator and also provide the same information to the discriminator. That information is a set of fake class labels. We also provide the discriminator with the real labels for the training data. The advantage of cGAN is that we have more control over what we generate, and convergence is faster. cGAN architecture is the foundation for some very important image to image translation architectures like Pix2Pix and CycleGAN [14].

2.4. Pix2Pix—Image to Image Translation

Pix2Pix architecture was developed in order to generate the translation of an image to a new image with a different style applied to it. For example, we can leverage the model to generate an image with identical features to a daytime photograph, transforming it into a nighttime scene. Or we can take a real picture obtained from a certain height and transform it into a map style image. This type of model requires a paired dataset. The generator takes a real image and some noise as input in order to produce an outcome with a desired style applied. Let us take, for example, the process of making an edge diagram for a real image scenario. The generator would take the edge map as input and try to generate the real image. The discriminator is going to take both the generated image and the edge map as input. The generator loss is a pixel-wise loss. This loss measures the similarity between the generated image and the target image at the pixel level. It encourages the generator to reproduce the fine details and structural information accurately. Reference [15] mentions the L1 loss, which is a mean absolute error (MAE), which computes the pixel-wise differences between the generated and target images. The discriminator loss looks at the real loss and generated loss. The real loss is a sigmoid cross-entropy loss of the real image and an array containing only 1′s. The generated loss is a sigmoid cross-entropy loss of the generated image and an array containing only 0′s. The total loss is the sum of the real loss and the generated loss [16].

2.5. CycleGAN

Unlike Pix2Pix we do not need to use paired datasets. In Pix2Pix we need data from both categories in order for the model to understand how to correlate and translate them. CycleGAN applies the learned style from one dataset to the other dataset. For example, if we want to perform translation from edges to images, we need a dataset that contains images with edges and a corresponding dataset that includes the real image of that item. What makes CycleGAN unique is its ability to utilize unpaired data, meaning we can have a dataset of castle images and another dataset featuring a specific painting style. By the end of the process, we can successfully apply the painting style to the castle images, despite the fact that the images were never paired together at any point.

The generating process begins with an input image from either domain A or domain B. For instance, if we have a photograph of a horse, it belongs to domain A. To transform the input image into the target domain, we pass it through generator A (GA). GA takes the input image and generates an image in the target domain, which is domain B in this case. The output image produced by GA possesses the style and characteristics of domain B. If we desire to revert the image back to its original domain, we can use generator B (GB). By passing the image generated by GA through GB, GB takes the generated image from domain B and transforms it back to domain A. The resulting image should ideally resemble the original input image of the horse photograph. Therefore, by utilizing generators GA and GB, we can seamlessly translate an image from one domain to the other. For example, starting with a horse photograph in domain A, GA can generate an image in domain B that resembles a zebra painting. Then, by passing this generated image through GB, we can obtain an image back in domain A that closely resembles the original horse photograph. This is also called cycle consistency loss.

The discriminator process is also made up of two parts. The first discriminator receives as input the generated image and outputs a classification matrix. The second discriminator receives real data from domain B as input and outputs a classification matrix. In the end we apply least squares loss between the two classification matrices. The first discriminator encourages the first generator to translate the input into fake images as indistinguishable as possible from images in domain B and vice versa for the second discriminator and the second generator. This creates a consistent cycle, hence the name of the architecture.

CycleGAN is a great option when dealing with unpaired data, but if paired data is available, Pix2Pix architecture is preferred because it is faster in training. The results are realistic only when the style translation is made between objects with a similar shape or features. Also, the results are very good in tasks that include texture, style, or color changes [15].

2.6. ProGAN—Progressively Growing GAN

T. Kerras and his team from NVIDIA introduced the ProGAN architecture in 2017 and its purpose was to generate faces of people that do not exist in the real world. The name of the architecture comes from the fact that they progressively increase both the generator and the discriminator. The layers of the network are organized in the form of a pyramid. The latent vector starts from a low resolution and increases with every layer. For the experiments they used a dataset of images with celebrities of size 1024 × 1024 pixels and the generated results were very good. Naturally, the generated faces bear a resemblance to the individuals present in the training dataset. The generated results can be controlled if different features are specified, for example we can control the direction the person is looking at [17].

2.7. StyleGAN

StyleGAN is the state-of-the-art method for generating new images. It is also the work of T. Kerras and the other team members from NVIDIA. StyleGAN is based on ProGAN. It employs a distinct generator architecture inspired by style transfer, specifically adaptive instance normalization. This architecture enables the model to learn high level features, such as facial positions, hairstyles, beards, and various other characteristics. In StyleGAN the latent vector is mapped to an intermediate latent space that controls the generator through adaptive instance normalization. Multiple improvements and versions are available for StyleGAN. The most recent one is called StyleGAN3 [18].

2.8. SRGAN—Super Resolution GAN

Super resolution GAN tackles the challenge of estimating a higher resolution image from a low resolution version. It uses a perceptual loss function consisting of an adversarial loss and a content loss. The discriminator is trained to distinguish between original low resolution images and super-resolution generated images. Moreover, the authors proposed the use of a content loss based on perceptual similarity, rather than pixel space similarity. The generator uses residual blocks and skip connections. This is meant to keep the information from previous layers, so that the network could choose more features adaptively. The input used for the generator is the low-resolution image. The used loss function is the perceptual loss function. The perceptual loss function is made up of two parts: content loss and adversarial loss. The content loss measures how much of the original content is going to get lost during training. When we perform super resolution, new pixels need to be added to the image. The neural network needs to produce new pixels from the image. When this happens, we can lose some context from the original image. New pixels need to be added to the image and they should be related to the original image, that is what the content loss indicates [19].

2.9. ESRGAN—Enhanced SRGAN

It is an improvement compared to the original SRGAN. There are some changes in the architecture and loss function. A new deep neural network model instead of the residual blocks was adopted. A relativistic average GAN [20] is used instead of the vanilla GAN. The perceptual loss is also improved before applying the activation functions. The ESRGAN produces less blurry and better quality images than SRGAN [21].

2.10. MedGAN

MedGAN appeared as a solution to the problem that not enough medical data is available for experiments. The authors of [22] indicate that accessing medical databases can be difficult, particularly due to the sensitive nature of the data. Furthermore, the authors highlight that large medical organizations, which have access to such databases, often demand significant financial resources for their use. medGAN is to accomplish two important objectives. The first one is to preserve the privacy of the patients, so that it would be practically impossible to gain knowledge about real people from the synthetic data. The second one is to produce data of a good enough quality, so that the models trained on synthetic data could perform as well as the ones trained on real data.

The particularity of the medGAN architecture is that an encoder–decoder model was added. The discrete real data input is encoded into a continuous embedding vector. Then, the decoder is used to convert back to a discrete representation of the input in the data space. Both the encoded input data as well as some random noise are put through that decoder. Then, the discriminator takes the data provided by the decoder as well as the real data and decides the probability of the data being true or false. For the autoencoder, cross-entropy loss is used.

Different GAN architectures were experimented with to see which one would provide the best dimension-wise probability distribution. MedGAN showed the best performance [22].

2.11. Synthesizing Electronic Health Records Using Improved Generative Adversarial Networks

The proposed method in [23] is supposed to obtain better results than medGAN. The goal of this research is to provide a privacy-preserving solution that enables data sharing, analysis, and research involving electronic health records (EHRs) without violating patient privacy regulations or exposing sensitive information. By generating synthetic EHR data that closely resembles real patient records, the authors aim to facilitate various applications, such as medical research, predictive modeling, and healthcare analytics. They propose two variations of the medGAN: Wasserstein GAN with gradient penalty (WGAN-GP), and boundary-seeking GAN (BGAN).

In the proposed medWGAN, an improved generative network called WGAN-GP is employed, instead of the general GAN. The remaining structure is the same as that of medGAN. The authors of the WGAN-GP model made a claim that the previous version of Wasserstein GAN (WGAN) allowed for stable training, but produced low-quality samples or failed to converge in certain scenarios due to the use of the weight-clipping technique. To address these problems, they introduced an alternative weight-clipping method called gradient penalty, which involves penalizing the gradient norm of the discriminator (critic), with respect to its input. The WGAN-GP model shows improved performance compared to various GAN architectures, including the standard WGAN. Therefore, in this study, the hypothesis was that applying medWGAN to generate synthetic EHRs would result in superior performance compared to employing the original medGAN [13].

medBGAN is proposed as an alternative model to medGAN, achieved by replacing the traditional GAN with a new algorithm called BGAN. A generator is trained to match a target distribution that progressively converges to the true data distribution as the discriminator is optimized. The objective can be understood as training the generator to generate samples that reside on the decision boundary of the current discriminator during each update. Consequently, the GAN trained using this algorithm is referred to as BGAN. This algorithm enhances effective performance for both discrete and continuous variables and exhibits qualitatively superior performance compared to conventional GANs. Similar to medWGAN, it is expected that medBGAN will deliver high performance in generating synthetic EHRs. Their results show that medBGAN performed the best [23].

2.12. AMD-GAN

The authors of [24] present the difficulty in detecting fundus diseases, particularly in the context of retinal imaging, using scanning laser ophthalmoscopy (SLO) images with an ultra-wide field.

A primary obstacle encountered in the approach of an artificial intelligence-based solution is the persistent issue of limited available data. Usually, a method based on GANs could be used to augment the dataset, but in this case, a constraint specific to this medical concern and its associated image data type lies in the inefficacy of GANs. The small size of salient objects within SLO images causes the GAN difficulties in extracting high-level features.

To overcome these problems, the authors of [24] proposed a method called AMD-GAN. The method uses a generator and a discriminator. The generator has two parts: an attention encoder (AE) and a multi-branch (MB) structure. The encoder network uses real data and random Gaussian noise as input. The AE and generation modules help extract details from low-level information and generate features at different scales. The AE is made of the following layers: convolution, batch normalization, ReLU, and maxpooling. An attention mechanism is used to combine these extracted features from real data with features generated at the same scale. The fake images are generated from a random Gaussian noise input. The random noise is passing through three pairs of upsampled residual blocks followed by the AE module, and after this, passing through another three upsampled residual blocks (RU block). This output (the fake generated data) along with the real data is then passed to the discriminator. The RU block is made of the following layers: batchnorm, ReLU up-sampling, 3 × 3 conv, batchnorm, ReLU, 3 × 3 conv. The loss used by the generator is described in Equation (1).

The discriminator (used as a classifier in this problem scenario) uses a multi-branch structure based on a ResNet-34 backbone model to capture rich high-level features. The authors added a deep-wise asymmetric dilated convolution (DADC) [25] block to refine high-level features and speed up training with fewer parameters. The loss used by the discriminator is described in Equation (2).

To generate good fake images, the authors use adversarial loss which tries to maximize the probability of real images being recognized as real and generated images being considered fake. To ensure that the generated images not only look real but are also correctly classified, the authors use a classification loss. The classification loss is different for real and fake data. To ensure that the generated images capture the overall content information of the input images, they also use the mean square error (MSE, or L2 norm) between the generated images and the real images. This is called the content loss. The final loss is made of the previously mentioned losses, and they propose the use of two coefficients α and β (which are set between 1 and 10 in their experiments) to control the classification and content losses.

2.13. One-Class Classification Using Generative Adversarial Networks

The work in [26] presents a way to improve one-class classification using GANs. One-class classification has very important applications like: fraud detection since fraudulent transactions are relatively rare compared to legitimate ones, detecting anomalies in network traffic, which can help identify potential cyber threats or attacks and early disease detection. According to [27], there are three types of OCC classifiers: trained with positive examples only, trained with positive and unlabeled data, trained with positive samples and some artificially generated outliers. The authors of [26] focus on the third type of OCC classifier. They introduce an OCC architecture named OCC-GAN. The GAN’s discriminator is very useful in a scenario like this because it can distinguish real from fake, meaning it can be used for identifying outliers. During training, the generator steps up, autonomously creating artificial outliers, eliminating the need for manual outlier set construction.

To optimize their GAN model, they modified the discriminator’s final layers, transforming its output into categorical judgments. Utilizing a softmax function, they mapped the output to possibilities of being a target or an outlier. The discriminator then computes losses based on these probabilities. The adversarial training strategy encourages the generator to create more lifelike data, boosting the discriminator’s performance. The authors also introduced a novel OCC index, the classification recall index (CRI), to overcome deficiencies in existing criteria. They replaced the CNN architecture with a dense block structure, preventing gradient vanishing, strengthening feature connections, and ultimately improving the model’s performance.

The OCC-GAN architecture is similar to the original principle of GAN. The primary modification involves adapting the traditional GAN structure to prioritize an effective Discriminator for distinguishing targets and outliers accurately.

Both the generator and discriminator are divided into dense blocks and transition layers. The feature flow within a dense block is maintained through a concatenation layer, for feature extraction. Dense blocks include a bottleneck structure with a fixed output channel of 32 (to reduce the parameters), keeping the feature map resolution constant. The OCC-GAN employs three dense blocks and three transition layers in both the generator and discriminator. At the end, the feature map is converted into a binary vector and the largest value for a category is used as the classification result. Mean square error loss (MSE) is used instead of binary cross-entropy loss (BCE), facilitating the translation of output possibilities into explicit categories.

In Table 1 we can observe a summarization of the previously discussed GANs and their main scenario of use.

Table 1.

Summarizing GANs architectures and their main purpose of use.

3. Dataset and Methods

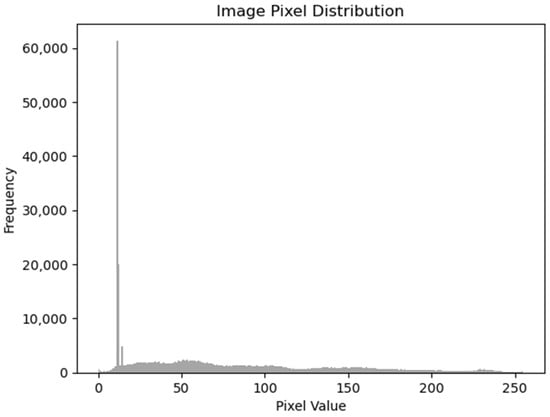

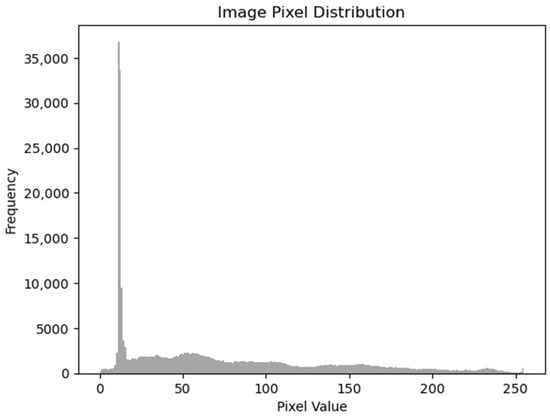

As an experiment, we focused on testing one type of the previously presented GAN methods on a dataset containing medical images. The name of the dataset is CVC-ClinicDB [28] and it is a dataset with 612 images with a resolution of 384 × 288, extracted from the video of a colonoscopy. The dataset was created by the Computer Vision Center, Barcelona, Spain, based on data from The Clinic Hospital of Barcelona. We chose to generate new enhanced resolution images, using different variations of the ESRGAN, with the purpose of finding out how the distribution of the image would differ. First, we generated an image with increased resolution, using the GAN, then, we resized the image to the original size, and finally, we plotted the distribution of the image in comparison to the original one. To do this, we plotted a histogram containing the frequency of the pixel values from 0 to 256.

If we increase the size of an image using an ESRGAN and then resize it back to the original size, the resulting image is not considered a completely new image. It is still derived from the original image, but with enhanced resolution.

The purpose of using ESRGAN is to generate a high-resolution version of the input image by extrapolating details and enhancing fine textures. However, when we resize the image back to the original size, some of the details and textures that were added by the ESRGAN may be lost or altered.

In the context of a segmentation task, using the ESRGAN-enhanced and resized image can have both advantages and limitations. The advantages include the potential for improved segmentation accuracy, due to the increased resolution and enhanced details. The enhanced textures and sharper edges produced by the ESRGAN have the potential to improve the accuracy of object boundary detection.

However, it’s important to note the potential limitations, as well. The resized image may not perfectly retain all the original details and may introduce artifacts or distortions during the resizing process. Additionally, if the ESRGAN introduces any unrealistic or inaccurate features, these could impact the computer vision task results.

We chose to employ a pretrained ESRGAN, due to several compelling reasons. Firstly, pretrained models have already undergone extensive training on large-scale datasets, which helps them capture rich and diverse features from the data. This pretraining phase enables the model to learn complex patterns and representations that are beneficial for enhancing the quality of our output.

Secondly, pretrained ESRGAN models have proved remarkable performance in single image super-resolution tasks. By leveraging the knowledge and insights gained during their training, we can leverage their ability to generate high-resolution and visually appealing images from low-resolution inputs.

Moreover, employing a pretrained ESRGAN allows us to save significant computational resources and time. Rather than training a model from scratch, we can build upon the existing knowledge encoded in the pretrained model, accelerating our development process, and reducing the need for extensive data and computational requirements.

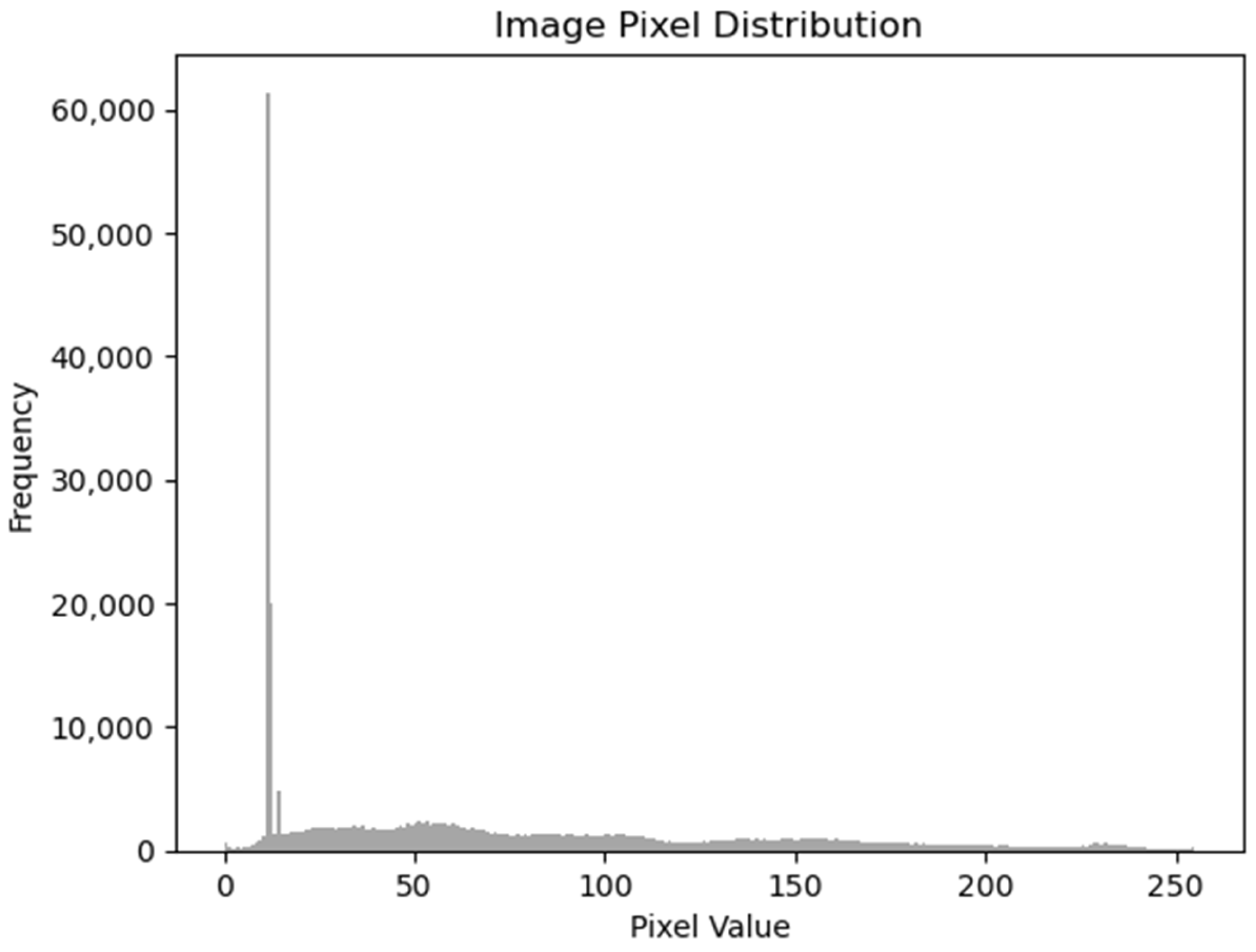

For our experiments, we first used an ESRGAN. Compared to the original SRGAN, it contains a deep neural network that uses residual-in-residual dense blocks, instead of the batch normalization layers. The idea is to generate some new images with their resolution increased (1152 × 1536) and then resize them to the original dimension of the image (288 × 384). The objective is to obtain similar looking images, so that the discriminator is performing its role well, but we do not need the images to have exactly the same distributions, hence the goal is to obtain some new data. It can be seen in Figure 1 and Figure 2 that the distributions of the original image and the generated image are similar, but not identical.

Figure 1.

Original image histogram.

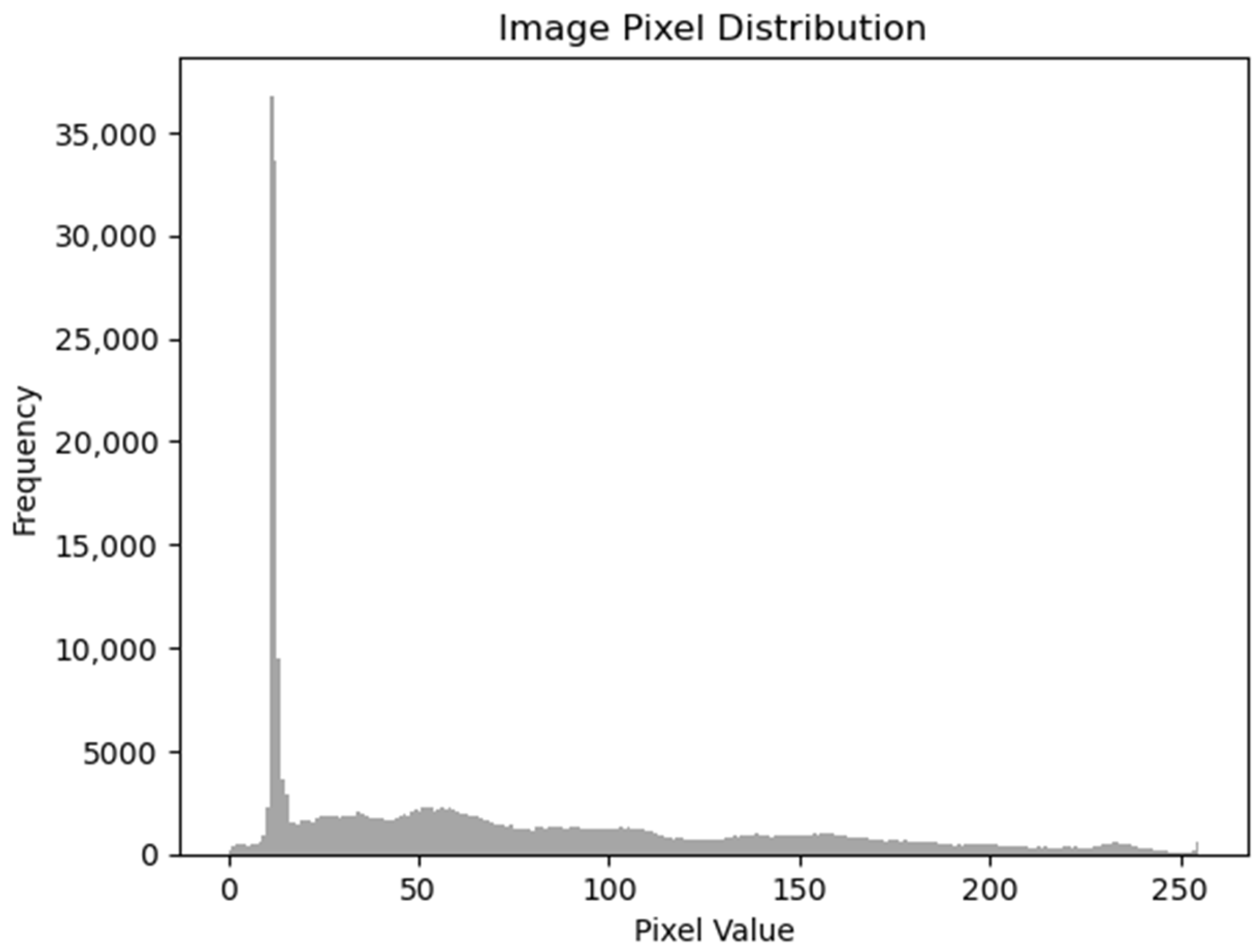

Figure 2.

Generated image histogram using ESRGAN.

We also used the pretrained model Real-ESRGAN to generate the figures from the next chapter. Usually, a resolution model made for enhancing the resolution of images is trained on datasets containing good resolution images/ground truth images and corresponding images with diverse types of degradation. One challenge is to simulate the degradation that happens in the real world, which can be caused by a lot of variables: camera blur, sensor noise, JPEG compression, sharpening artifacts, image editing, file transfer over the Internet, etc. To overcome this, the authors of [29] introduced a high-order degradation modeling process, with the purpose of simulating complex real-world degradations.

The model was trained using DIV2K [30], Flickr2K [31], and OutdoorSceneTraining [32] datasets. The authors used the Adam optimizer and the loss was a combination of L1 loss, perceptual loss, and GAN loss, with the following weights {1, 1, 0.1}. Some limitations are twisted lines and unpleasant artifacts, caused by GAN training, and unknown and out-of-distribution degradations [29]. Such a limitation of not being able to preserve the natural edges of nuclei. This could affect the model’s generalization capabilities. However, if we deal with a task in which we need to make the data better to visualize by an expert, these artifacts may not be such a very big disadvantage. Improving the resolution of medical images could also be very important in scenarios where the medical image quality is constrained by the quality of the equipment and the time it needs to produce a high-quality image. For example, magnetic resonance imaging (MRIs) and computed tomography (CT scans) are two very common types of medical datatypes, and their quality depends on the equipment and the time allocated for performing the scan. The quality of these images is crucial in making an accurate decision model. In [33], the authors give, as an example, tissues that are small and hard to identify within the eye’s fundus. Elements like soft exudates, microaneurysms, or hemorrhages could potentially be identified better from an enhanced resolution image. The most significant drawback remains that artifacts could appear during the resolution increasing procedure and this may affect model performance. To take advantage of all types of data and combine them to obtain higher quality datasets, the authors of [34] have proposed a multimodal image fusion method, with the purpose of creating a clear image, without artifacts caused by the scanning process, based on a multi discriminator hierarchical wavelet GAN. Methods like [34] could be used to overcome imperfections in medical data and combine the strong points from different types of data like CTs, MRIs, positron emission tomography (PET), etc.

4. Results

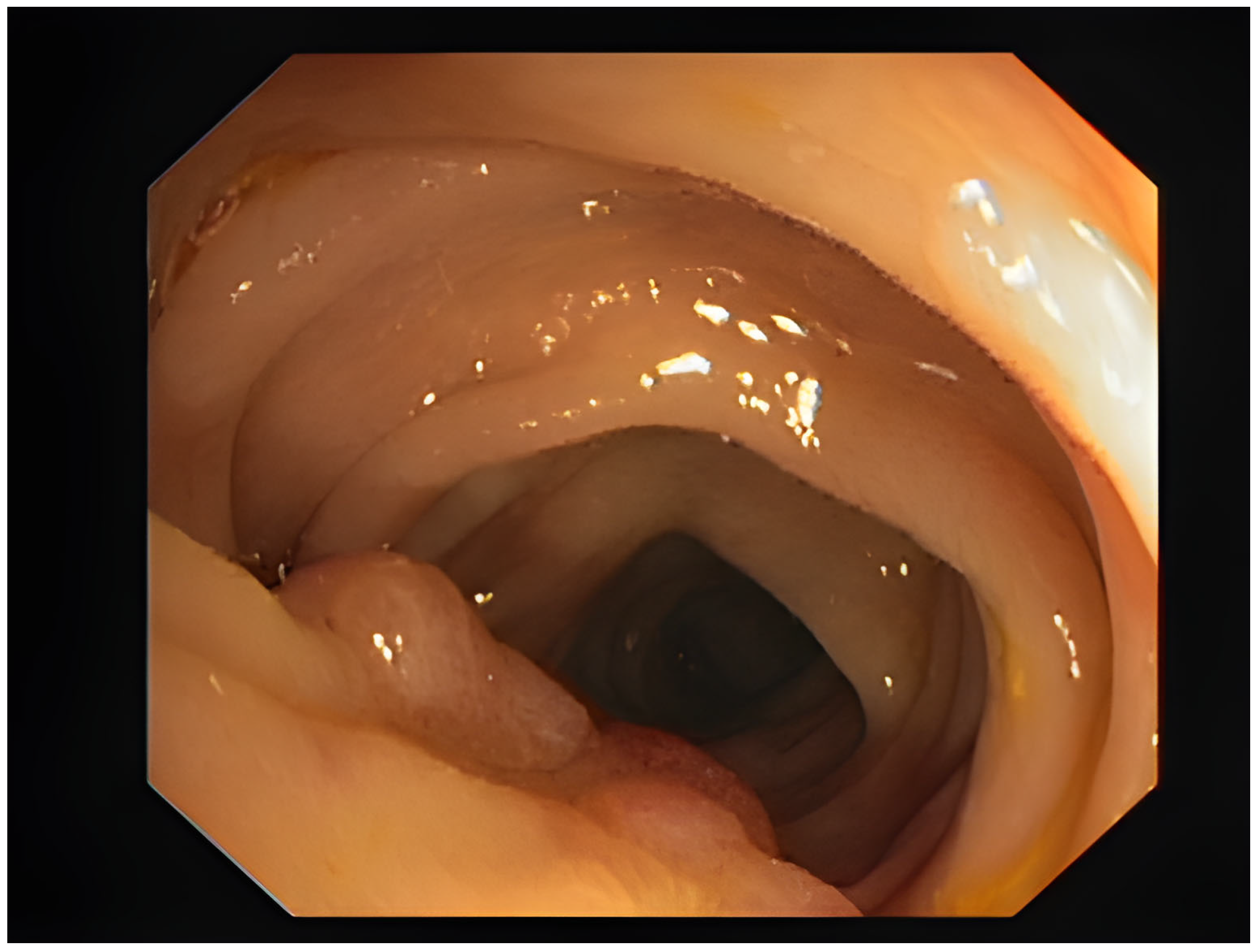

Another way to show that the images are not the same is to compute the structural similarity index (SSIM) and the mean squared error (MSE). SSIM values range from −1 to 1, where 1 indicates perfect similarity, and MSE measures the average squared difference between corresponding pixel values in the two images. A lower MSE indicates less difference between the images. The SSIM and MSE scores for Figure 3 and Figure 4 are: SSIM: 0.9185 and MSE: 0.0006. The provided SSIM and MSE values show that, while the two images are highly similar, which was expected and can be evaluated by a visual inspection, they are not exactly the same.

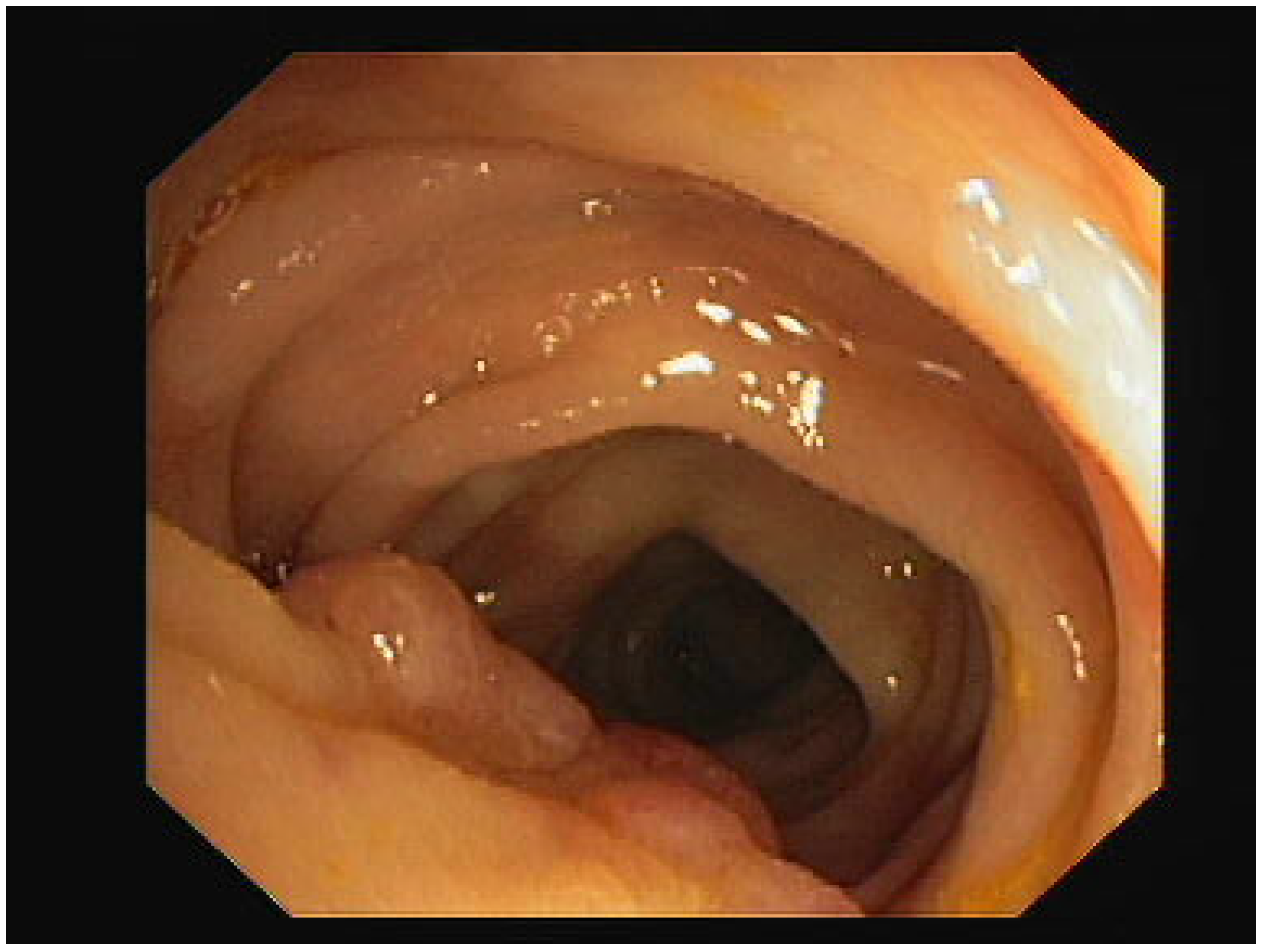

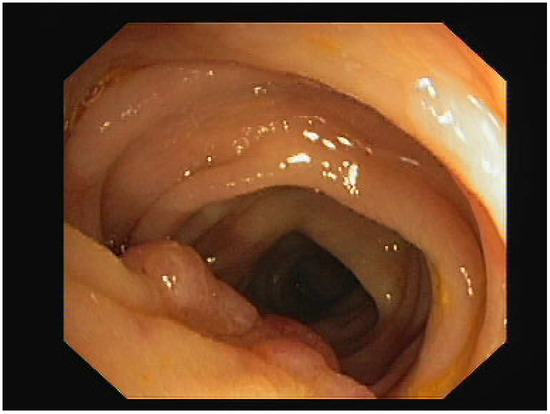

Figure 3.

Generated image using PSNR model.

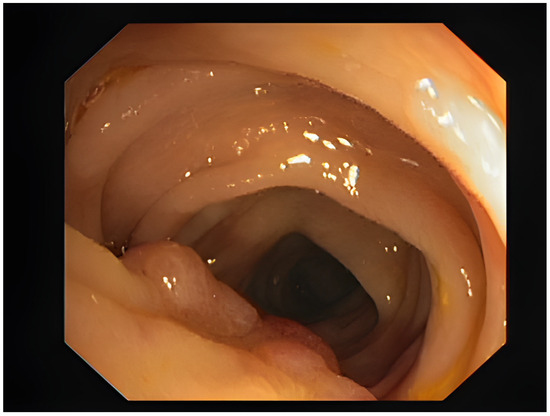

Figure 4.

Generated image using Real-ESRGAN.

In Figure 1 and Figure 2, the image pixel distribution for the original image and the ESRGAN generated image can be observed.

One downside of generating higher resolution images is the appearance of artifacts around edges. One method to lower the appearance of artifacts is PSNR, or peak signal-to-noise ratio. It is used in ESRGAN as a metric to evaluate the quality of super-resolved images. PSNR measures the difference between two images by evaluating the peak signal power (the maximum possible value) and the amount of noise or distortion introduced during the process of upscaling or image enhancement. A higher PSNR value indicates a smaller difference between the generated image and the original image, implying better image quality. We also generated a set of images from the same input dataset, with a model using PSNR. The differences might not be immediately apparent, yet the distributions vary notably. In Figure 3, an example of an image generated with the PSNR model is displayed.

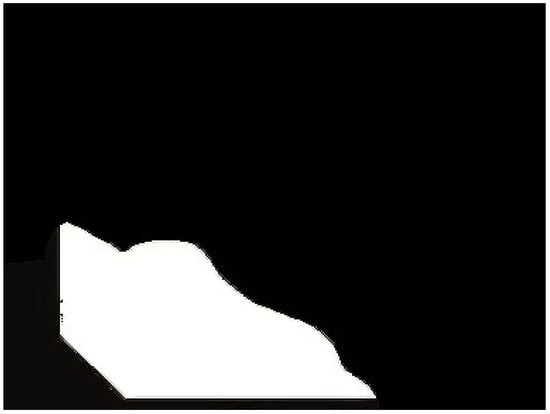

Lastly, we used Real-ESRGAN to generate new images, as can be seen in Figure 4, along with the corresponding segmentation mask from Figure 5. The segmentation mask is part of what is provided by the dataset. We ensure the application of the same augmentation technique to the original image and to the corresponding mask. In the case of a segmentation mask, we make sure that features like edges of the area of interest align correctly between the original image and the mask. Real-ESRGAN is a state-of-the-art solution for increasing resolution. Compared to the original ESRGAN, it proposes a U-net discriminator with spectral normalization, to increase discriminator performance and stabilize the training dynamics [29].

Figure 5.

Generated segmentation mask using Real-ESRGAN.

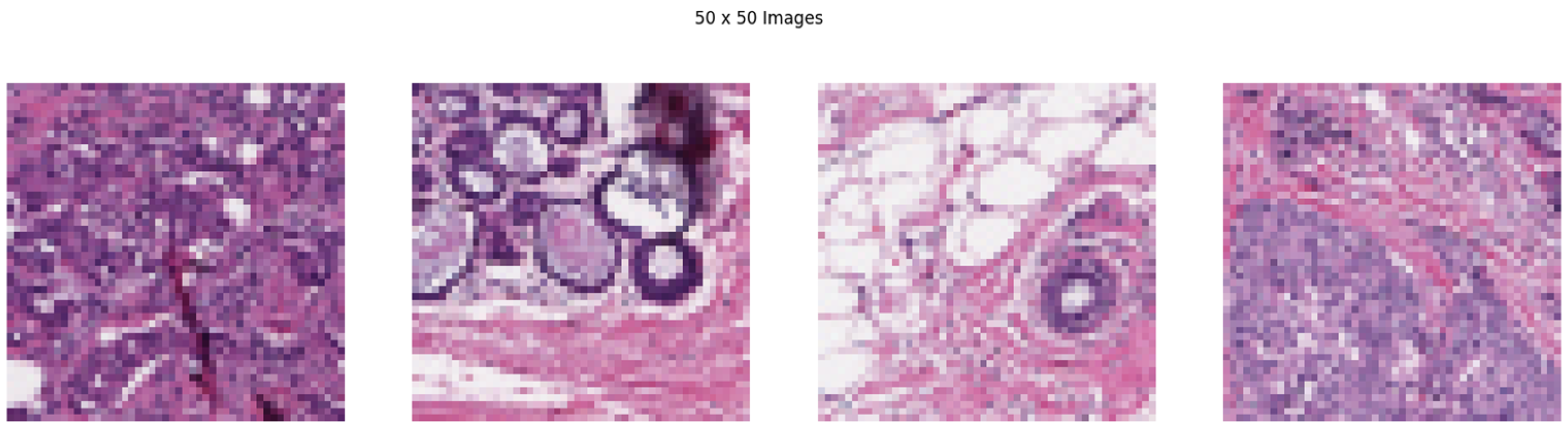

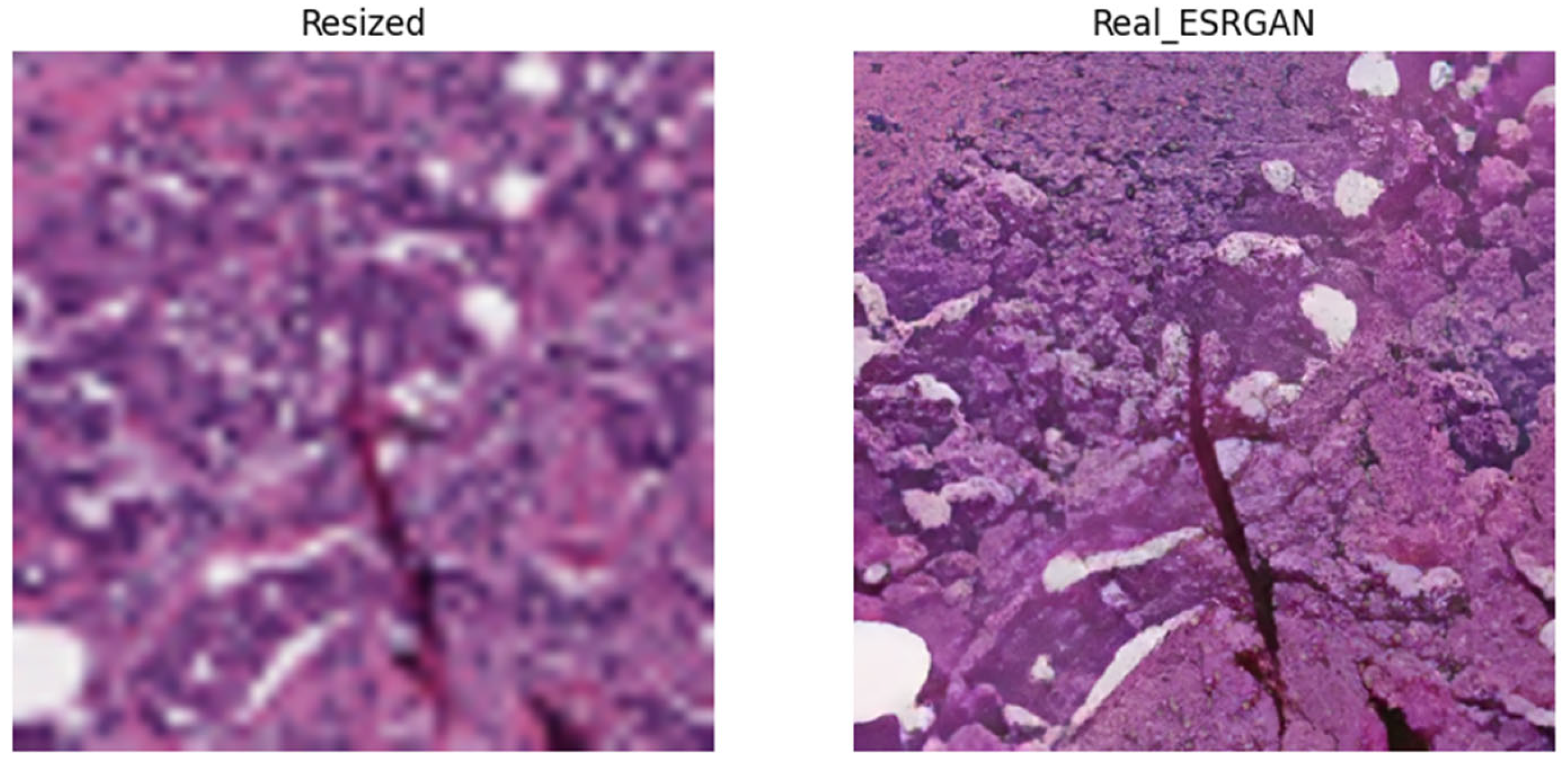

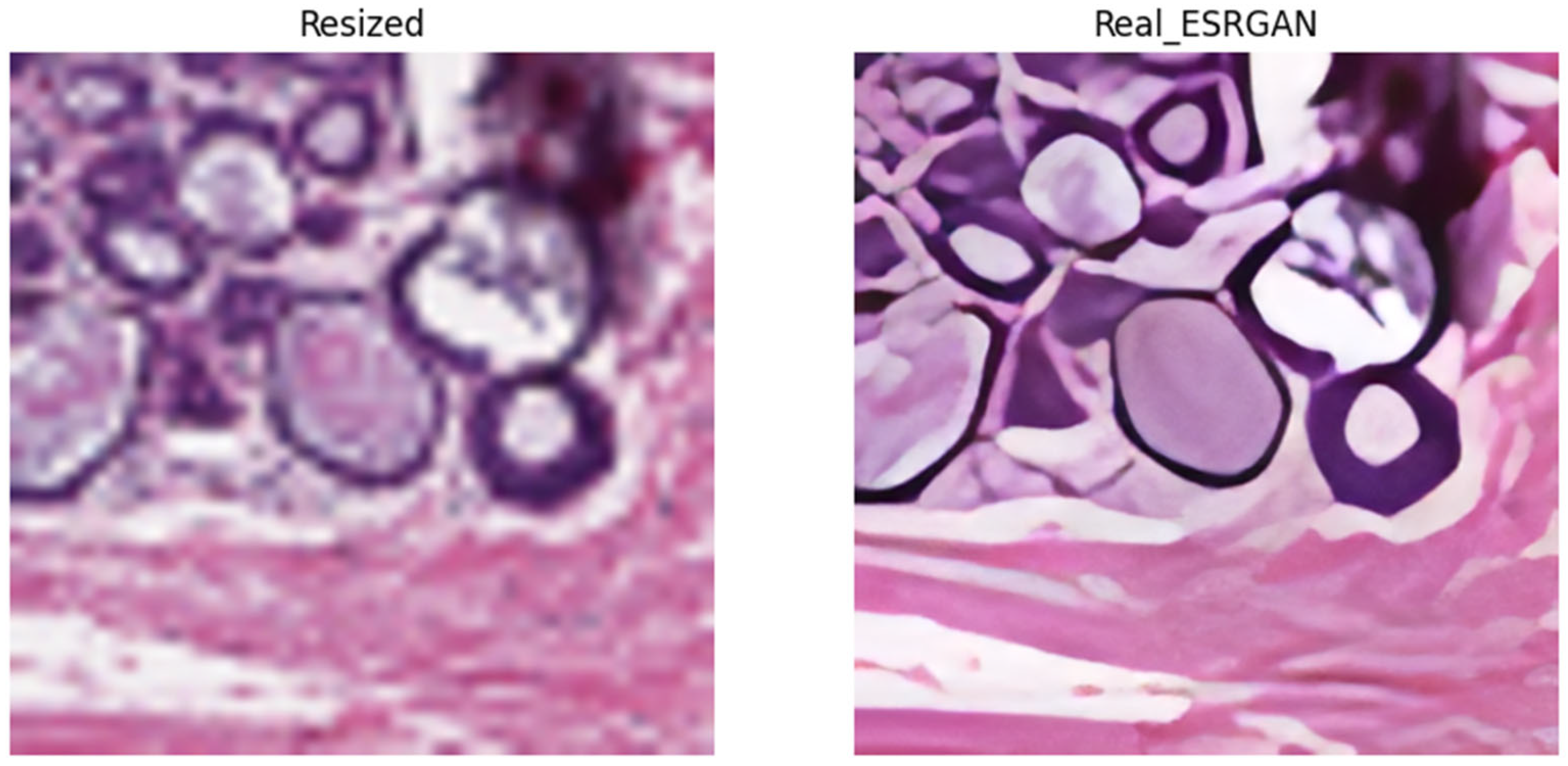

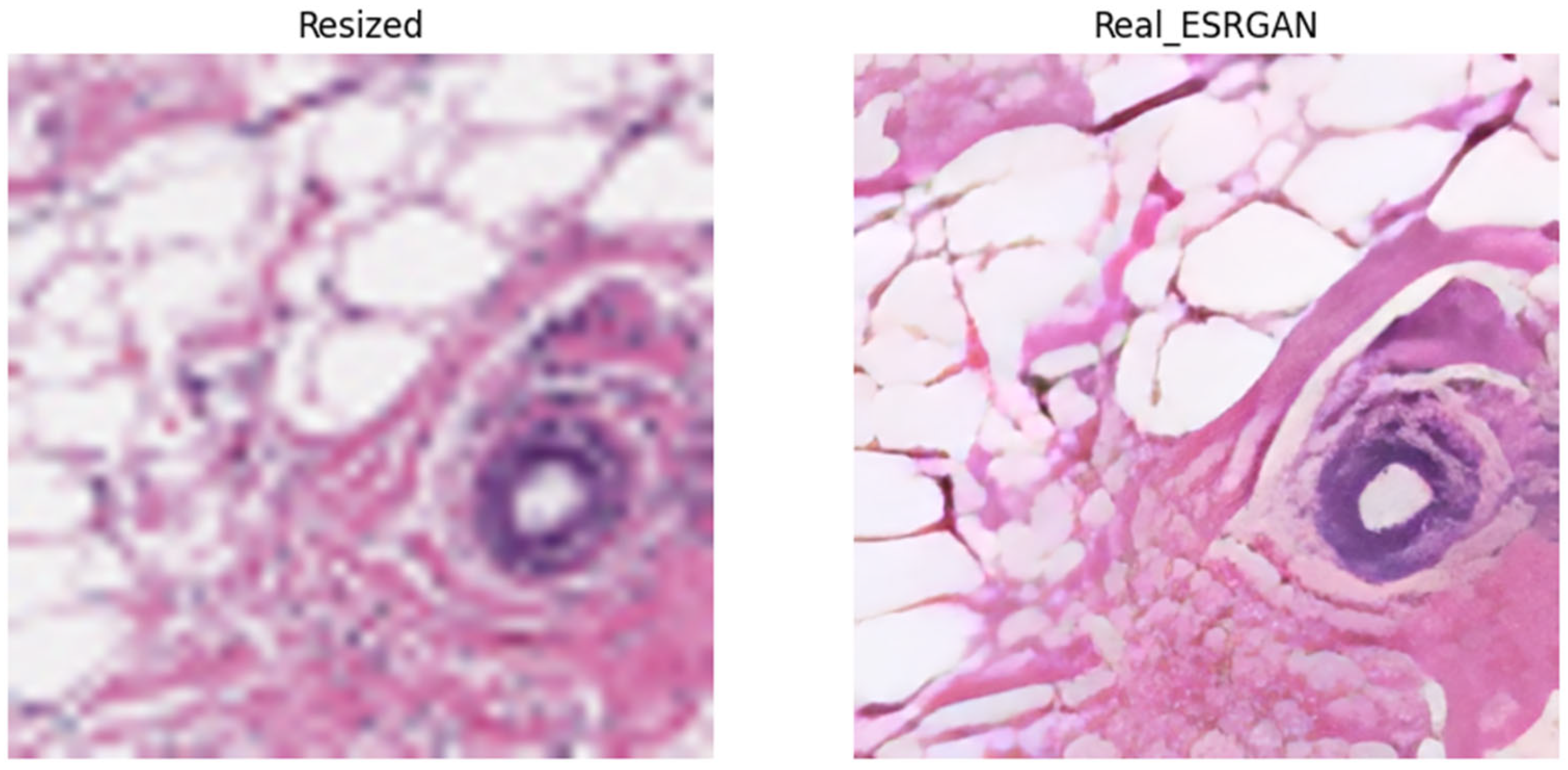

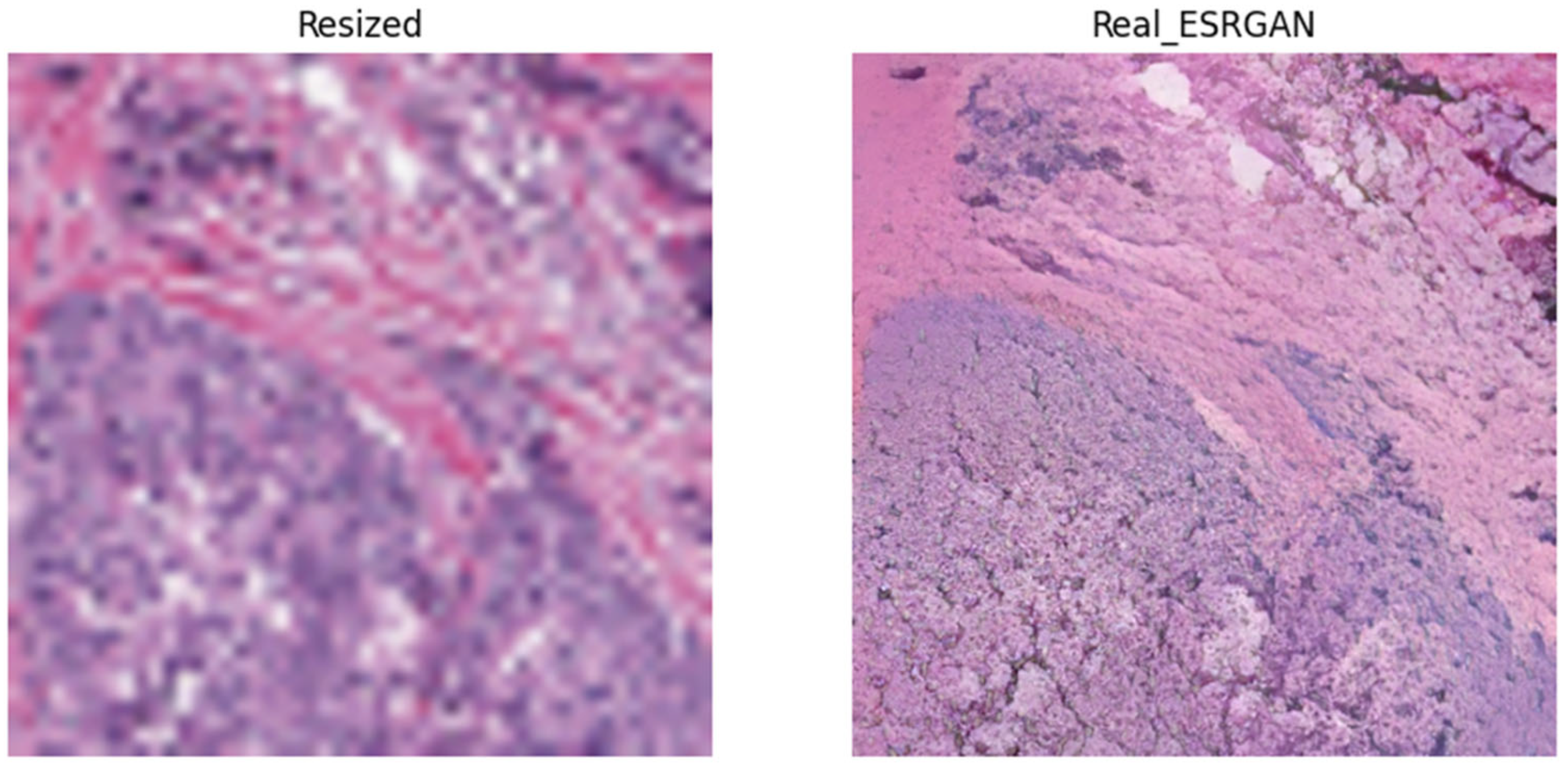

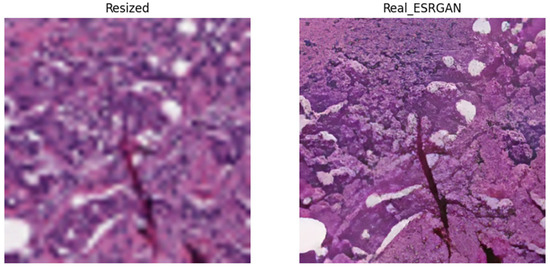

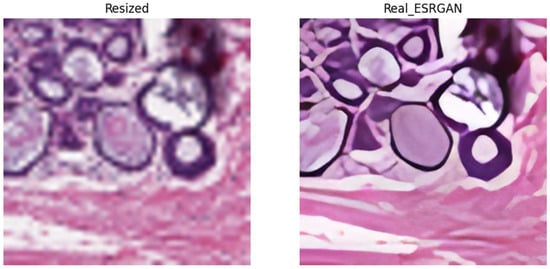

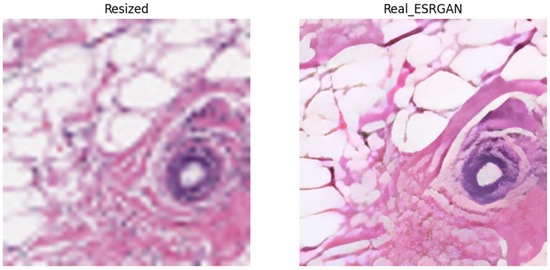

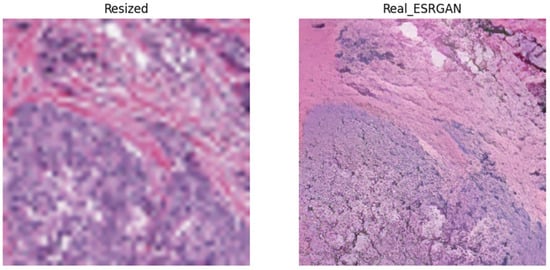

To provide a more suggestive visual qualitative analysis, we also applied the Real-ESRGAN to a breast histopathology dataset [35]. The original images are 50 × 50 pixels in size and show invasive ductal carcinoma pathology. If we would like to use this dataset for a task like semantic segmentation, it would be a very unpleasant and maybe impossible task to annotate the images at this size. A simple change of image size produces blurry results. In a scenario like this, it is observed that resolution enhanced images present a better quality. In Figure 6, four of the original images from the dataset are presented. In Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9 and Figure 10 we can see on the left the simple resized image and on the right the Real-ESRGAN enhanced image.

Figure 6.

Breast Histopathology Images 1, 2, 3, 4.

Figure 7.

Breast histopathology image 1 resized (left) and Real_ESRGAN generated (right).

Figure 8.

Breast histopathology image 2 resized (left) and Real_ESRGAN generated (right).

Figure 9.

Breast histopathology image 3 resized (left) and Real_ESRGAN generated (right).

Figure 10.

Breast histopathology image 4 resized (left) and Real_ESRGAN generated (right).

We can observe that there is a similarity of the characteristics between Figure 7 and Figure 10, and, respectively, Figure 8 and Figure 9; this similarity can also be seen in the results from Table 2. The SSIM and MSE values are closer together for images that share similar characteristics. Also, this shows that the chosen model is capable of consistency and generalization.

Table 2.

SSIM and MSE values computed between resized and Real_ESRGAN images.

5. Conclusions

The current review has provided a comprehensive overview of the current state-of-the-art architectures of generative adversarial networks within the domain of computer vision. The experiment with enhanced super-resolution generative adversarial networks revealed their capability in generating additional data for diverse datasets, without just duplicating existing information. Looking ahead, GANs hold significant potential in semi-supervised tasks across various domains. Their ability to generate realistic data expands the possibilities for training models with limited labeled data, making them invaluable in scenarios where obtaining large labeled datasets is challenging.

For future work, we want to extend the applicability of ESRGANs. We want to experiment and find out how semantic segmentation tasks would perform on datasets enriched with extra generated images, compared to the original dataset. Furthermore, we want to apply ESRGAN to augment patches from histopathology images. In histopathology imaging, the scanned image of the tissue is of very high resolution, but only a small part of the image actually contains areas of interest. This is why, for histopathology image segmentation, the image is divided into patches, maintaining only the relevant ones for our classes [36]. Consequently, there is a need to increase the resolution of these small patches, where ESRGAN could prove beneficial. Additionally, in the case of these images, a GAN could be employed to alter the colors, as this represents the most common augmentation technique for this type of medical image.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.-M.S., Ș.R. and A.M.F.; formal analysis, A.-M.S., Ș.R. and A.M.F.; investigation, A.-M.S. and Ș.R.; methodology, A.M.F.; project administration, A.M.F.; software, A.-M.S.; supervision, Ș.R. and A.M.F.; validation, Ș.R. and A.M.F.; visualization, A.-M.S. and Ș.R.; writing—original draft, A.-M.S., Ș.R. and A.M.F.; writing—review & editing, A.-M.S., Ș.R. and A.M.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This paper is supported by the Romania’s Recovery and Resilience Plan under grant agreement 760009, project “Creation, Operationalization and Development of the National Center of Competence in the field of Cancer”, PNRR-III-C9-2022—I5.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available in this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Goodfellow, I.J.; Pouget-Abadie, J.; Mirza, M.; Xu, B.; Warde-Farley, D.; Ozair, S.; Courville, A.; Bengio, Y. Generative Adversarial Nets. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1406.2661v1. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, L. The mnist database of handwritten digit images for machine learning research. IEEE Signal Process. Mag. 2012, 29, 141–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The CIFAR-10 Dataset. Available online: https://www.cs.toronto.edu/~kriz/cifar.html (accessed on 22 August 2023).

- Toloka. History of Generative AI. Toloka Team. Available online: https://toloka.ai/blog/history-of-generative-ai/ (accessed on 22 August 2023).

- Rombach, R.; Blattmann, A.; Lorenz, D.; Esser, P.; Ommer, B. High-Resolution Image Synthesis with Latent Diffusion Models. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2112.10752. [Google Scholar]

- Ling, H.; Kreis, K.; Li, D.; Kim, S.W.; Torralba, A.; Fidler, S. EditGAN: High-Precision Semantic Image Editing. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2111.03186. [Google Scholar]

- Antipov, G.; Baccouche, M.; Dugelay, J.-L. Face Aging with Conditional Generative Adversarial Networks. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1702.01983. [Google Scholar]

- Siarohin, A.; Lathuiliere, S.; Sangineto, E.; Sebe, N. Appearance and Pose-Conditioned Human mage Generation using Deformable GANs. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1905.00007v2. [Google Scholar]

- Ruan, S. Anime Characters Generation with Generative Adversarial Networks. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Conference on Advances in Electrical Engineering and Computer Applications (AEECA), Dalian, China, 20–21 August 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Developer, N.; Mamaghani, M.; Ghorbani, N.; Dowling, J.; Bzhalava, D.; Ramamoorthy, P.; Bennett, M.J. Detecting Financial Fraud Using GANs at Swedbank with Hopsworks and NVIDIA GPUs. Available online: https://developer.nvidia.com/blog/detecting-financial-fraud-using-gans-at-swedbank-with-hopsworks-and-gpus/ (accessed on 26 March 2021).

- Radford, A.; Metz, L.; Chintala, S. Unsupervised representation learning with deep convolutional generative adversarial networks. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1511.06434v2. [Google Scholar]

- Arjovsky, M.; Chintala, S.; Bottou, L. Wasserstein GAN. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1701.07875v3. [Google Scholar]

- Gulrajani, I.; Ahmed, F.; Arjovsky, M.; Dumoulin, V.; Courville, A. Improved Training of Wasserstein GANs. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1704.00028v3. [Google Scholar]

- Mirza, M.; Osindero, S. Conditional Generative Adversarial Nets. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1411.1784v1. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, J.-Y.; Park, T.; Alexei, P.I.; Efros, A. Unpaired Image-to-Image Translation using Cycle-Consistent Adversarial Networks. arXiv 2020, arXiv:1703.10593v7. [Google Scholar]

- Isola, P.; Zhu, J.-Y.; Zhou, T.; Efros, A.A. Image-to-Image Translation with Conditional Adversarial Networks. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1611.07004v3. [Google Scholar]

- Karras, T.; Aila, T.; Laine, S.; Lehtinen, J. Progressive growing of GANs for improved quality, stability, and variation. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1710.10196v3. [Google Scholar]

- Karras, T.; Aila, T.; Laine, S. A Style-Based Generator Architecture for Generative Adversarial Networks. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1812.04948v3. [Google Scholar]

- Ledig, C.; Theis, L.; Huszár, F.; Caballero, J.; Cunningham, A.; Acosta, A.; Aitken, A.; Tejani, A.; Totz, J.; Wang, Z.; et al. Photo-Realistic Single Image Super-Resolution Using a Generative Adversarial Network. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papers with Code. Available online: https://paperswithcode.com/method/relativistic-gan (accessed on 1 June 2023).

- Wang, X.; Yu, K.; Wu, S.; Gu, J.; Liu, Y.; Dong, C.; Loy, C.C.; Qiao, Y.; Tang, X. ESRGAN: Enhanced Super-Resolution Generative Adversarial Networks. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1809.00219v2. [Google Scholar]

- Armanious, K.; Jiang, C.; Fischer, M.; Küstner, T.; Hepp, T.; Nikolaou, K.; Gatidis, S.; Yang, B. MedGAN: Medical Image Translation using GANs. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1806.06397v2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baowaly, M.K.; Lin, C.-C.; Liu, C.-L.; Chen, K.-T. Synthesizing electronic health records using improved generative adversarial networks. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2018, 26, 228–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, H.; Lei, H.; Zeng, X.; He, Y.; Chen, G.; Elazab, A.; Wang, J.; Zhang, G.; Lei, B. AMD-GAN: Attention encoder and multi-branch structure based generative adversarial networks for fundus disease detection from scanning laser ophthalmoscopy images. Neural Netw. 2020, 132, 477–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, G.; Yun, I.; Kim, J.; Kim, J. DABNet: Depth-wise asymmetric bottleneck for real-time semantic segmentation. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1907.11357. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Hou, C.; Lang, Y.; Yue, G.; He, Y. One-Class Classification Using Generative Adversarial Networks. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 37970–37979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.S.; Madden, M.G. One-class classification: Taxonomy of study and review of techniques. Knowl. Eng. Rev. 2014, 29, 345–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaggle. Available online: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/balraj98/cvcclinicdb (accessed on 14 December 2023).

- Wang, X.; Xie, L.; Dong, C.; Shan, Y. Real-ESRGAN: Training Real-World Blind Super-Resolution with Pure Synthetic Data. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2107.10833. [Google Scholar]

- Agustsson, E.; Timofte, R. Ntire 2017 challenge on single image super-resolution: Dataset and study. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Timofte, R.; Agustsson, E.; Van Gool, L.; Yang, M.; Zhang, L.; Lim, B.; Son, S.; Kim, H.; Nah, S.; Lee, K.M.; et al. Ntire 2017 challenge on single image super-resolution: Methods and results. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Yu, K.; Dong, C.; Loy, C.C. Recovering realistic texture in image super-resolution by deep spatial feature transform. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Umirzakova, S.; Mardieva, S.; Muksimova, S.; Ahmad, S.; Whangbo, T. Enhancing the Super-Resolution of Medical Images: Introducing the Deep Residual Feature Distillation Channel Attention Network for Optimized Performance and Efficiency. Bioengineering 2023, 10, 1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, C.; Yang, P.; Zhou, F.; Yue, G.; Wang, S.; Wu, H.; Chen, G.; Wang, T.; Lei, B. MHW-GAN: MultiDiscriminator Hierarchical Wavelet Generative Adversarial Network for Multimodal Image Fusion. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2023, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janowczyk, A.; Madabhushi, A. Deep learning for digital pathology image analysis: A comprehensive tutorial with selected use cases. J. Pathol. Inform. 2016, 7, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; He, Q.; Duan, H.; Shi, H.; Han, A.; He, Y. Using Sparse Patch Annotation for Tumor Segmentation in Histopathological Images. Sensors 2022, 22, 6053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).