Abstract

The field of Natural Language Processing (NLP) has experienced significant growth in recent years, largely due to advancements in Deep Learning technology and especially Large Language Models. These improvements have allowed for the development of new models and architectures that have been successfully applied in various real-world applications. Despite this progress, the field of Legal Informatics has been slow to adopt these techniques. In this study, we conducted an extensive literature review of NLP research focused on legislative documents. We present the current state-of-the-art NLP tasks related to Law Consolidation, highlighting the challenges that arise in low-resource languages. Our goal is to outline the difficulties faced by this field and the methods that have been developed to overcome them. Finally, we provide examples of NLP implementations in the legal domain and discuss potential future directions.

1. Introduction

Natural Language Processing is a scientific field combining linguistics and Artificial Intelligence. It has various applications across multiple domains, such as voice assistants, search engines, and language translation services, and as a result, it has been heavily studied throughout the past decade [1]. The number of high-profile implementations of Natural Language Processing highlights its significance. What has enabled the practical use of NLP is the introduction of machine learning in the field. Deep Learning specifically allows complex problems to start being examined or greatly improves previous solutions.

Most Natural Language Processing works are developed and tested on general-domain and English data. This creates two considerable problems. First, NLP techniques may not be applied from one language to another as is, due to the fact that some languages have different grammar or characters (e.g., Japanese). Second, the structure and terms used in specific domains may create significant obstacles, like in medical or legal documents (with terms that do not appear in any other kind of document) or Twitter comments (where the use of slang or irony is dominant). As a result, the efficiency of NLP models takes a serious hit when applied to low-resource languages or other domains and, of course, even more so when combined [2].

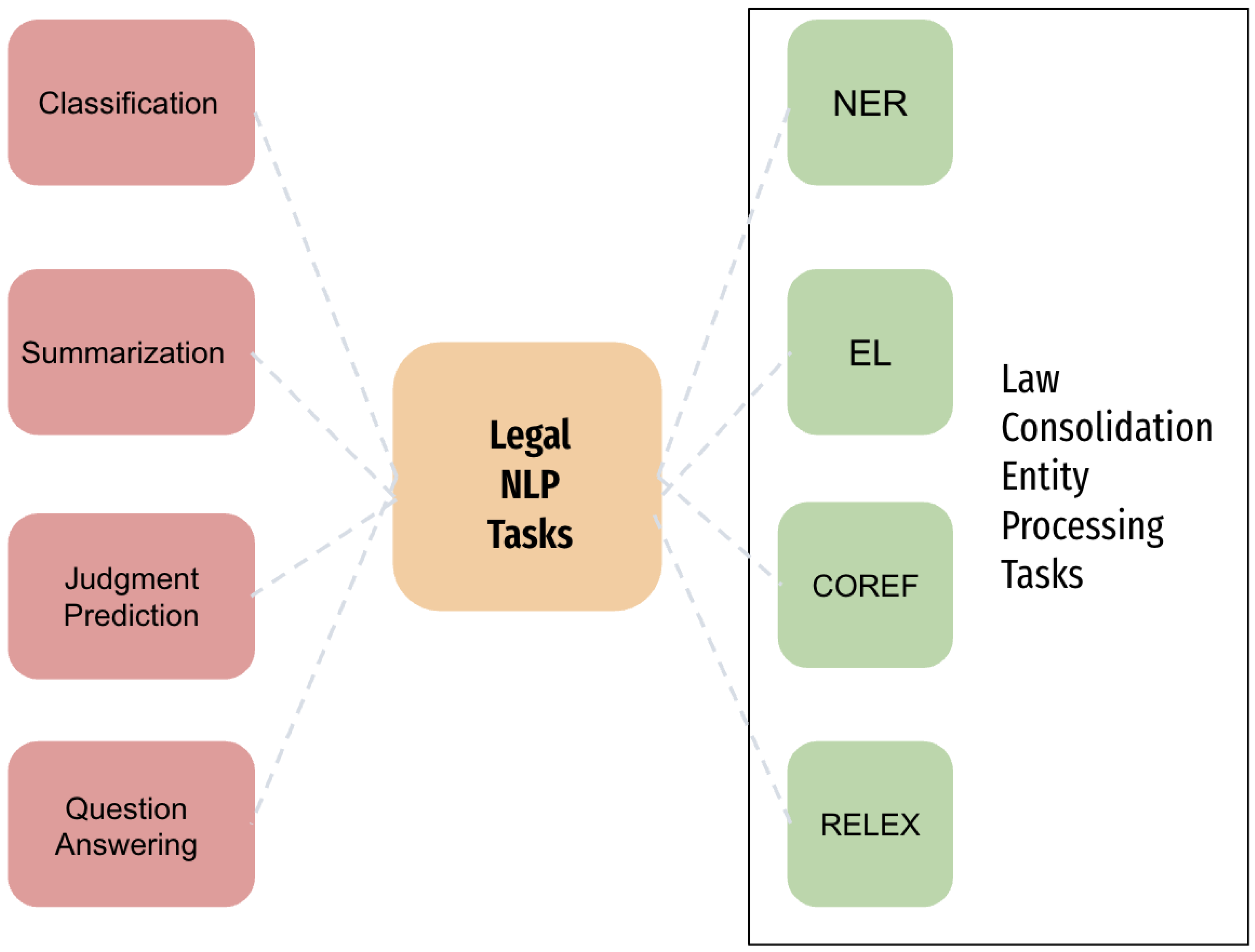

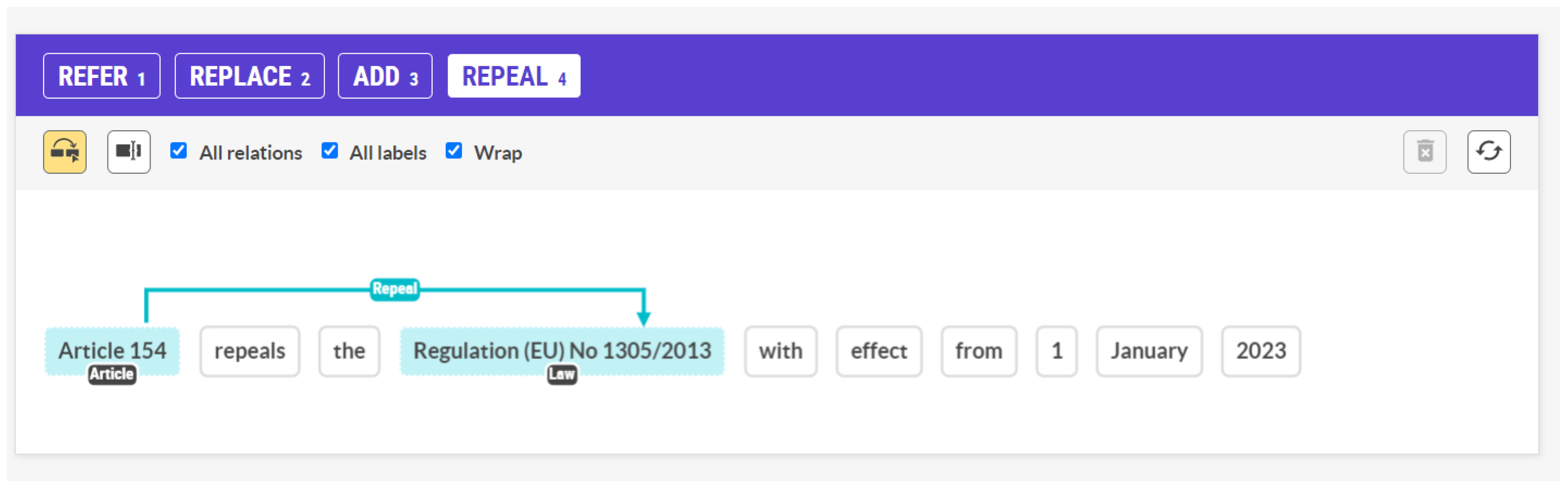

The application of Natural Language Processing in the legal domain has started to gain traction and be investigated further, as it would greatly benefit that domain [3], but is still lacking in comparison to other domains. The main tasks that researchers try to solve in the sub-field are the Entity processing tasks, namely, Named Entity Recognition (NER), Entity Linking (EL), Relation Extraction (RelEx), and Coreference Resolution( Coref). Other important tasks include classification, summarization, translation, judgment prediction, and question answering (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Natural Language Processing tasks for legal documents.

In an endeavor to make this survey paper comprehensive, it would be unrealistic to encompass all related works for every Natural Language Processing (NLP) task that is applicable within the realm of the legal domain. Hence, in this work, our emphasis is primarily on the entity processing tasks that comprise NER, EL, RelEx, and Coref. We have selected these four crucial tasks as they are instrumental in achieving our ultimate quest, which is the development of a version control system accustomed for legal documentation and law consolidation.

Law consolidation involves merging multiple legislative acts that deal with the same or related subjects into a single, coherent legal text. The purpose is to organize the law more systematically and make it easier to understand for both legal professionals and the general public. It helps users to comprehend the relationships and dependencies between laws, streamlining the application and interpretation of legal concepts. It is essentially a process used to simplify the legal system, helping to identify which legal articles interact with a particular law. To better understand our desired goal and its implications, we will elaborate further with an example.

Consider a law practitioner who wants to read a specific law. They need a couple of things that might be taken for granted but are not always provided. First, they want to find the most recent version of the law, since laws can change as new legislation is introduced. They also want to easily track how that law has evolved over time (version control system). Next, they would like to identify the links and references to and from that law. This is important for seeing which legal articles the law interacts with (law consolidation). Even though these data seem crucial, they are not readily available in most countries, either from governmental records or even paid services. As an example, Eunomos [4] is a similar system conceptually that uses ontologies to achieve its objectives.

So, after the example, let us clarify why the aforementioned tasks are necessary for our goal. We need a system that can automatically extract the mentioned legal entities (NER) in a legislative document. These may be entire laws or really specific parts of them, like articles or even sentences in paragraphs of articles. Unfortunately, there are times when an abbreviation of a law can be translated to more than one law or different versions of the same law, having undergone major revisions over the years, so we have to disambiguate them properly (EL). It is also common that there are references to the “above law” or a law that is mentioned only in context, so Coreference Resolution is also necessary. Finally, we need to find the type of connection between them (mentioned in Section 2.1), as it will affect the legislation differently (RelEx). On the other hand, the tasks of summarization or classification may lose the nuances and precise use of language in legal documents required for a law consolidation system, so they were not investigated in this work.

As a result, we believe that laying the foundations in this field is critical to showing the progress so far and push the research forward. We present the related works for each of the above four tasks, with an added focus on non-English language approaches and multilingual methods that can be applied to other low-resource languages as well.

For the purposes of this survey, we have employed a hybrid approach combining both State-of-the-Art Review and Scoping Review methodologies in the field of Natural Language Processing (NLP). This approach provides both an in-depth examination of the most recent research developments in the ever-evolving field of NLP and a broad exploration of the breadth of the literature in this area. With a specific focus on low-resource languages and the legal domain, the aim of this survey is to comprehensively appraise how the featured advanced NLP techniques are currently being applied, as well as their potential future applications, in these specific contexts. The ultimate goal is to provide a valuable resource that may stimulate and guide future research at the intersection of NLP, law, and low-resource languages.

In Section 2, we state the essential information on the problem. In Section 3, we provide an extensive presentation of the related work in the area of Natural Language Processing for the tasks of Named Entity Recognition, Entity Linking, Coreference Resolution, and Relation Extraction. Section 4 focuses on multilingual and low-resource language NLP research. Then, we continue in Section 5 by describing the advancements in the field of legal NLP. Finally, Section 6 suggests future steps in our research and in this field in general and concludes this paper.

2. Background Information

In this section, we provide some essential background information on the subjects addressed in this paper. We briefly describe the peculiarities of legal data and provide an overview of Deep Learning Neural Networks leading to the current state of the art.

2.1. Legal Data

Legal documents have distinctive characteristics that set them apart from other types of documents. They are primarily categorized into laws, case laws, legislative articles, and administrative documents. These documents are often interconnected and can be complicated due to their continuous expansion. Legal documents are connected in three ways: insertion, where a passage of text is added verbatim in the original; repeal, where the new document revokes a specific fragment of the original; and substitution, where the new legislation replaces a part of the original. It is often difficult to identify the type of connection between legal documents, and the fact that they only affect a portion of the original document makes it increasingly challenging to validate the current state of a legal document [5].

NLP practices have yet to achieve their full potential in the legal domain due to a lack of annotated legal datasets. Despite the clear benefits of NLP for the legal domain, there is a significant shortage of quality data. The implementation of Deep Learning techniques is heavily dependent on data quality, and the legal domain often lacks openly accessible data. The constant release of new laws also makes it necessary to have a version control system of legislation, which is currently not provided. With these issues in mind, our research began in this area [6].

The legal domain presents many challenges for NLP. Some major challenges include disambiguating titles (e.g., Prime Minister), resolving nested entities, and resolving coreferences. Titles may require disambiguation to a specific person based on the time, year, and country. Abbreviations in titles or laws may require deep contextual knowledge to identify. Nested entities, such as titles of legislative articles referring to laws, add another layer of complexity. Coreference resolution, which is frequently encountered, may be complicated by intersecting laws. Legislation is often uploaded in PDF format, which is not machine-readable and poses its own challenges. Lengthy paragraphs spanning numerous pages are common in legal documents, making it challenging to apply NLP techniques, such as Relation Extraction and Coreference Resolution.

While there are many important tasks in legal document processing, our research focuses on those related to our goal. Some other tasks worth mentioning are classification, summarization, and judgment prediction. With classification, by labeling laws according to the subdomain that they touch upon (e.g., Admiralty law), we can facilitate the search for and connection between legal documents. Likewise, summarization (which is a task close to classification) aids legal professionals in quickly acquiring the relevant information of a document. Judgment prediction is a highly demanding task that requires our two-fold attention. It is the extremely interesting and challenging task of automatically obtaining a prediction on the ruling of a case. However, with great power comes great responsibility. The predicted decisions are based on data from previous cases, which unfortunately, more often than not, contain biased information. As a result, this creates a feedback loop that enhances potential discrimination, so their results should not be taken as impartial rulings, and it is necessary to address this issue at its core [7].

2.2. Natural Language Processing Outline

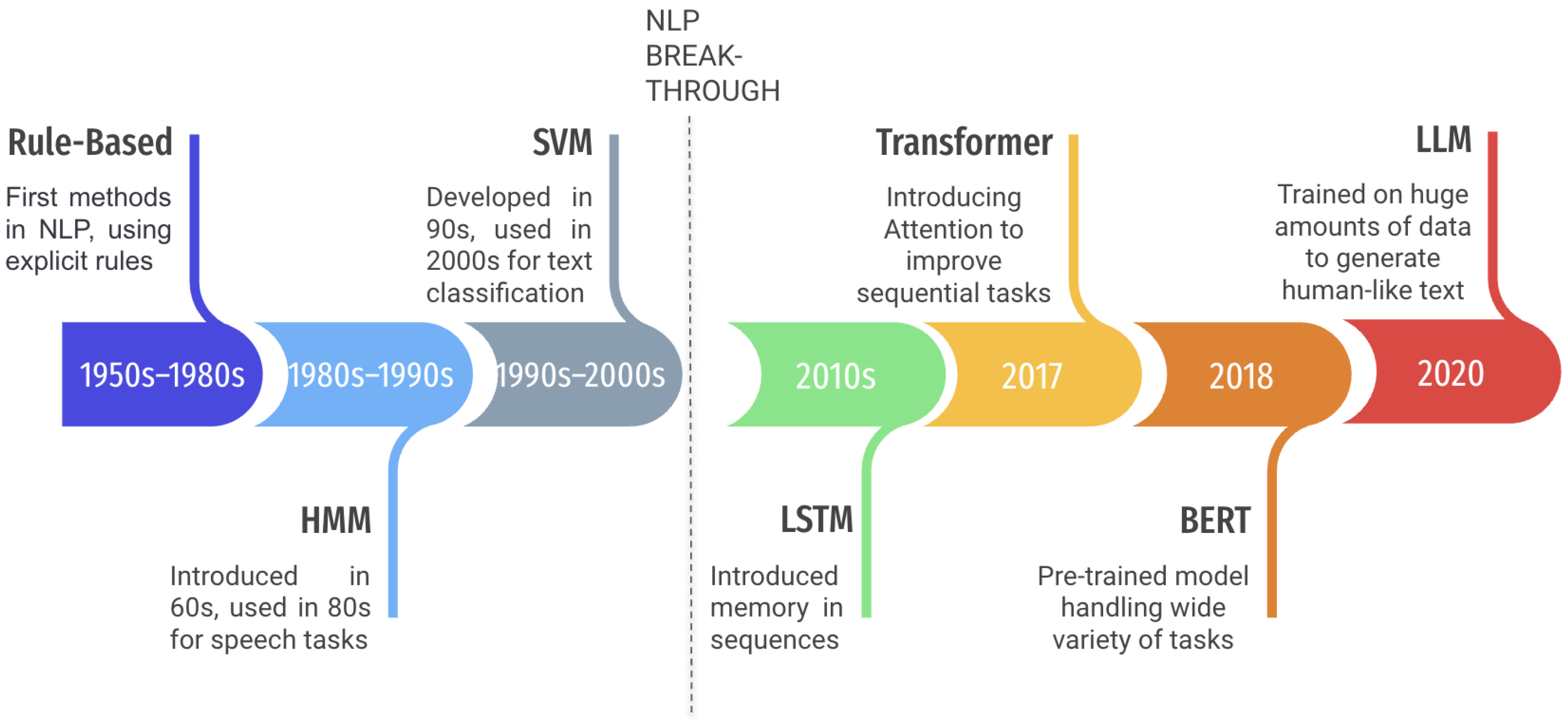

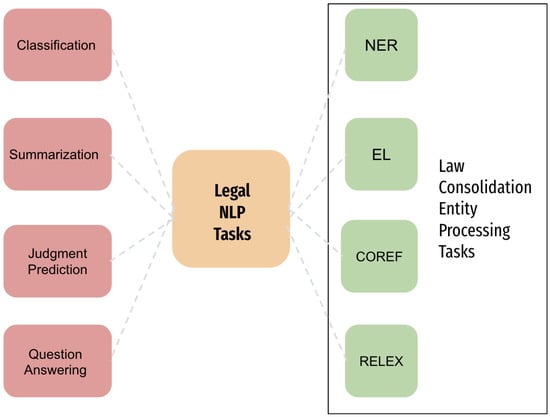

We now present a brief outline of the technologies used for Natural Language Processing, leading to the latest advancements (Figure 2). In the following sections of related works, we do not further analyze the properties of the main architectures described here to focus on the variations for each specific subtask. In this section, we mention the fundamental architectures that have been successfully applied in the field and have contributed to its advancement in the recent past.

Figure 2.

Timeline of essential Text NLP techniques.

Over the years, various techniques have been proposed for Natural Language Processing (NLP). Initially, rule-based approaches were built based on expert knowledge and linguistic rules to extract the desired information. Later, supervised and unsupervised learning techniques were introduced in the field. Supervised methods require a manually annotated corpus to solve the problem as a classification problem, while unsupervised learning requires less initial labeled data and allows the system to self-evolve to find new rules. NLP researchers have tested many methods, such as Hidden Markov Models (HMMs), Support Vector Machines (SVMs), and Conditional Random Fields (CRFs). With the emergence of Deep Learning in most fields, NLP research has shifted its focus in this direction in recent years [8].

Deep Learning and Deep Neural Networks (DNNs) are not new inventions, but the limitations in terms of hardware kept them from being examined as feasible models for many years. As we all know, Graphics Processing Units (GPUs) have been constantly improving over the years and, a couple of years ago, reached the point where they were capable of handling Deep Learning Neural Networks at an affordable price. This reignited the interest of many researchers, followed by the suggestion of improved models and techniques. In principle, there is no real difference between regular Neural Networks and DNNs, except that the latter have many hidden layers (hence, they are deep). This increase in depth increases the computational requirements but also enables solutions to complex problems that were impossible before. The other technique that cleared the way for many ground-breaking implementations is transfer learning, which is a machine learning technique that was devised for problems that are lacking in data but are similar to ones with a lot of resources available. These algorithms train on a broader problem and try to apply the trained model with some fine-tuning to the related problem [9].

The introduction of two Deep Learning models in the field of NLP changed the landscape forever. First, Long Short-Term Memory models (LSTMs) [10] started in the mid-1990s as a theoretical extension of Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) to address their issue with memory and the vanishing gradient problem. It was not until two decades later that these models started being implemented in practice and revitalized the interest in Deep Learning Neural Networks in NLP. Many of the state-of-the-art solutions nowadays are variations of or contain LSTM models and perform well in many scenarios. In terms of our score, LSTMs alleviate the issue of long-distance relationships (between entities). When text is processed in a Recurrent Neural Network, it does not maintain any information from previous iterations or past sentences, so no connection between distant entities can be established. LSTMs, however, preserve the most important information throughout the next steps, acquiring, as a result, a form of memory. The two most common LSTM configurations that we encounter are bidirectional models (biLSTMs) and sequence-to-sequence architectures (seq2seq). The former consists of two LSTMs, passing the important information both forward and backward, with this process enhancing their prediction abilities. The latter also stacks two LSTMs, but this time as an encoder–decoder model.

Despite all of these improvements, there was still a big issue with LSTMs. They only process sequential data and are not fit for parallel processing, making their training (even more so in larger models) really slow. So, the second vital model was developed, and that is Transformers [11]. Taking advantage of the aforementioned potent modern GPUs, Transformers were designed with parallelization as a major part of them. They also have two other defining features. The first is their structure, a sequential enc-dec model composed of multiple stacks. The encoder passes the input through various filters and is fed to the decoder to follow a similar process until the desired output. The second is attention, a novel concept proposed for Neural Networks that helps the Network decide, at each iteration, which are the most significant variables of each sequence to focus on in order to give them bigger weights and improve the final output.

Transformers were designed for neural machine translation applications, and they indeed achieved great results in that area. Nonetheless, their real impact came in the form of BERT (Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers) [12]. BERT is a pretrained model built on the foundations of Transformers and trained on large amounts of data. The creators of BERT, in order to create a robust model, trained it to solve two challenging and unique tasks: Masked Language Modeling (MLM) and Next Sentence Prediction (NSP). MLM takes a sentence as an input, and then random words are concealed (masked), so the model outputs its predictions of the most appropriate words to fill the masks. NSP takes two sentences as input, and the model has to predict whether they are in succession. After having been heavily trained in these tasks, the model is later fine-tuned to solve other similar NLP tasks.

From the multitude of BERT extensions and variations, the most important ones that we want to discuss are RoBERTa [13], XLNet [14], and GPT-3 [15]. Each one of the above has been carefully developed by one of the industry giants with abundant resources in order to outperform its competition. We mention them in chronological order. RoBERTa (robustly optimized BERT approach) from Facebook AI (Meta AI now) is an optimized BERT variant trained on more data with fine-tuned hyper-parameters that outperforms all other variations up to that point. XLNet is an autoregressive pretrained model by the Google AI Brain Team and combines the pros of the original BERT and Transformer-XL to leverage the disadvantages of both. GPT-3 (a continuation of their previous work, GPT-2) by OpenAI boasts the daunting number of 175 billion parameters trained on an immense amount of data, being the biggest model to date. The team notes the impact of such an endeavor (both technologically and otherwise).

The current landscape of NLP is being driven by Large Language Models (LLMs). LLMs like GPT-3.5/4, PaLM, Bard, and LLaMa not only understand the context but even generate human-like text, translate languages, and, in general, allow us to perform a wide variety of NLP tasks using a single model. OpenAI recently introduced GPT-3.5 and GPT-4, language models that boast powerful and versatile APIs that revolutionized the field [16]. Concurrently, Google’s research team developed the PaLM or “PAttern-producing Language Model”. The PaLM is built to emulate human-like abilities in language understanding, closely resembling the way human brains decipher and generate language [17]. Meta developed its LLaMa model, the Language Learning and Multimodal Association model, designed to understand and interpret natural languages through textual–visual interactions [18].

These advancements are leading us toward a future where language models will become indispensable tools in the field of NLP, but there are still some issues and risks before establishing them as the only solution, including ethics, bias, safety, and environmental impact, not to mention the potential of fabricated results from these models. In addition to that, these models can expose private data, and regulators have not managed to keep up with the incredible speed at which these models have appeared [19].

3. Related NLP Tasks

Natural Language Processing (NLP) has been gaining increasing attention in the past decade. The need for research on how to improve these techniques is undeniable. We are mainly concerned with the tasks used in the field of Legal Informatics and particularly in creating a Version Control System for Legislation. The tasks that we deemed necessary to research in that regard are Named Entity Recognition and Linking (NER/EL), Relation Extraction, and Coreference Resolution, especially their recent developments with Deep Learning. We continue by reviewing the related work on the essential NLP tasks in the legal domain.

3.1. Named Entity Recognition

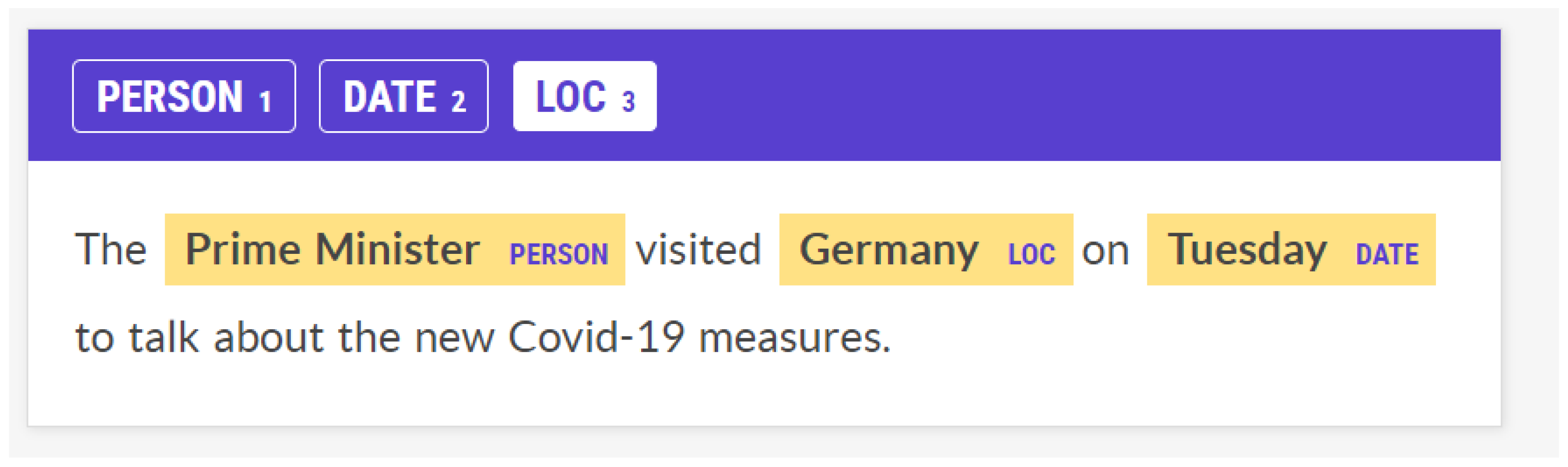

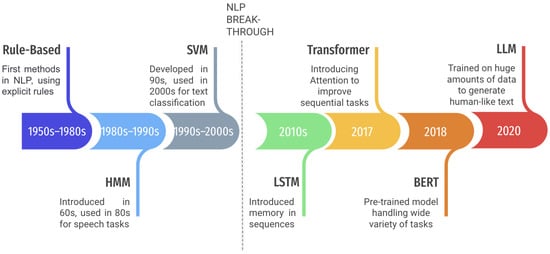

Named Entity Recognition (NER) is at the center of Natural Language Processing. This task strives to identify Named Entities in a text. These Named Entities usually fall into the categories of Person, Location (Loc), Organization, and Time/Date, but not exclusively. NER is almost a prerequisite for many other NLP tasks, such as the ones mentioned later in this work, and, as a result, is the most researched one. For a Named Entity Recognition example, consider the sentence “The Prime Minister visited Germany on Tuesday to talk about the new Covid-19 measures”. We have the following Named Entities: “Prime Minster” is a Person, “Germany” is a Location, and “Tuesday” is a Date (Figure 3). All of the NLP-task-related figures were captured in Prodigy (https://prodi.gy/, accessed on 3 February 2024).

Figure 3.

Named Entity Recognition example.

Named Entity Recognition may seem like a simple task, but it has many challenges. Language differences can hinder the application of established NLP approaches to other languages with different syntax or alphabets. Nested Named Entities make it extremely difficult to break them down and differentiate them, especially if they depend on context. Entities that are described with multiple words or spans (e.g., “Prime Minister”) also affect the process of Entity Recognition. Abbreviations (e.g., “PM” instead of Prime Minister) have a similar effect. Last but not least, a really important aspect that is not mentioned enough is the value of well-thought labeling schemes and appropriate datasets. This value is increased in subdomains (e.g., legal), where the quality of Entity Recognition can vary greatly depending on the selected labels of Named Entities that need to be identified. At the same time, the data must support these Entities sufficiently in order to train the machine learning models. The above two issues apply to the other tasks as well, but since NER precedes them, a wrong NER scheme will greatly affect all of them, while the opposite is not necessarily true.

As a highly researched problem, many methods have been suggested over the years as approaches to NER. Initially, pattern extraction techniques were used to gather the desired entities from semantic or syntactic information. These formulations could not address many of the challenges mentioned above, so research pivoted to machine learning. The main strategies that were proposed revolved around Support Vector Machines (SVMs), Conditional Random Fields (CRFs), and Markov Models (MMs). These did not provide satisfactory results but laid the foundations for later implementations.

Then, Deep Learning algorithms and word embeddings (or Vectorization) came and capitalized on the earlier ML advancements and started producing really promising results. Embeddings map real words to vectors of numbers (suitable for machine learning), capturing the contextual or semantic similarity of the words. The first great efforts used RNN and LSTM architectures. These reached the current state of the art, when they were combined with CRFs and Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) [20].

The state-of-the-art methods for Named Entity Recognition revolve around new pretrained Transformer-based models like BERT and RoBERTa that we described previously. Some of the most interesting advancements in the field of word representation or embeddings include LUKE [21], ACE [22], and CL-KL [23]. Language Understanding with Knowledge-based Embeddings (LUKE) is a Transformer-based model with an entity-aware attention mechanism and treats entities as tokens (individual words or terms) for better relationship representation between entities. This architecture has great results in Named Entity Recognition, Relation Extraction, and question answering. The authors of Automated Concatenation of Embeddings (ACE), focus on finding better word representations instead of a better model architecture, deeming it an equally important part of NLP tasks. They designed a controller for embedding concatenation and noted how their model can be implemented in other existing models to boost their performance. Finally, the authors of [23] suggest that injecting knowledge from a search engine improves the contextual representation of the input. Then, they introduce two Cooperative Learning models for NER with substantial results, raising interest in the further exploration of Cooperative Learning in the field.

For cross-domain NER, multiple methods have been suggested over the years. Recent approaches make use of the Deep Learning advancements in the general field, most notably language models, multitasking, and transfer learning [24]. The usual tactic is to train on the general NER dataset CoNLL and try to transfer the model to other domains, like medicine or news. The developers of L2AWE (Learning To Adapt with Word Embeddings) [25] claim their method can function on new domains without the need to retrain the NER model thanks to robust word embeddings like Word2Vec, which outperforms, in these cases, the contextual BERT embeddings. A different point of view is given in BERT-Assisted Open-Domain Named Entity Recognition with Distant Supervision (BOND) [26], where the authors decided to make use of the popular pretrained BERT models with a two-step training framework. First, they fine-tuned the RoBERTa model with distant supervision labels to imbue the model with semantic knowledge, and for the second step, they replaced these labels with a teacher-student framework to improve model fitting with training cycles on pseudo-labels.

Of course, LLMs and GPT have been tested for NER as well. The main contributions with meaningful and comparable results are presented in PromptNER [27] and GPT-NER [28]. The former is an innovative NER approach based on prompting. PromptNER demonstrates leading performance in few-shot learning and cross-domain NER. The methodology comprises four crucial elements: a backbone LLM, a modular definition outlining the entity types, a small set of examples from the target domain, and a well-defined format for presenting the extracted entities. GPT-NER adheres to the overarching concept of in-context learning and can be broken down into three sequential steps: (1) Prompt Construction, (2) Input to LLM, and (3) Text Sequence Transformation.

In most cases, the evaluation of the presented techniques is based on the precision, recall, and F1 score, and for our work, we will use the same metrics [29]. In IE, precision, p = RR/All, represents the ratio of relevant retrieved (RR) documents to the total of retrieved documents (All); e.g., in a text search query, it would be the number of relevant results divided by the number of all results. Recall, r = RR/Relevant, is the fraction of relevant documents that were retrieved to the total of relevant documents that should have been retrieved. F1 is the harmonic mean of precision and recall, F1 = 2 × (p × r)/(p + r).

In Table 1, we present the current state-of-the-art contributions. We want to note that many of these papers perform multiple NLP tasks, but for simplicity purposes, we only state the relevant task per table. In a similar vein, if a paper has results on multiple datasets, we present the comparable ones when they are available (meaning the datasets used by most papers). We also have to note at this point that in the last row of each of the following tables, the best legal approach to that task is presented. However, we do not mention them in the corresponding paragraphs just yet, but we present them all together in Section 5.

Table 1.

Major contributions to Named Entity Recognition.

3.2. Entity Linking

Now that we have finished with the presentation of Named Entity Recognition, we move on to a closely tied problem: Entity Linking (EL). They are often approached as a single problem and are either managed as pipelines or joint models, with Deep Learning still being the core of the state-of-the-art approaches [32]. The task of Entity Linking requires the disambiguation of entities based on a Knowledge Base. The most common Knowledge Bases used for this task are Wikipedia, YAGO (which combines Wikipedia and WordNet data), and DBPedia (multilingual structured content from Wikipedia). As an example, consider the sentence “The Prime Minister visited Athens”. We need to uniquely identify the “Prime Minister” mentioned in the sentence and also link them to the correct place they visited. As a matter of fact, there are more than 20 cities called “Athens” across the world, and someone may assume that, by default, it refers to Athens, the capital of Greece, which may not be always correct.

The main tasks that define Entity Linking are Mention Detection, Candidate Entity Generation and Ranking, and Entity Disambiguation [33]. First, the system needs to generate the candidate entities that may be linked to the examined entity and then generate a ranking of the list of potential candidates based on the probability of correct linking, and finally, a way to deal with the unlinkable entities is required. Throughout the years, various approaches have been proposed for each task separately, from heuristic to supervised and unsupervised methods, but recently, the research has shifted to end-to-end models, usually implemented with Deep Neural Networks.

The first end-to-end Neural Entity Linking model was established by the team of Kolitsas et al. [34]. They noted that the main challenge they wanted to address is finding the correct span of Named Entities to link. As a result, they proposed a joint NER and EL neural approach and used Wikipedia as their Knowledge Base. A different process is followed in Entity Linking using Densified Knowledge Graphs (ELDEN) [35]. In ELDEN, they try to solve Entity Linking as a graph problem and state how the density (number of edges in Knowledge Graph) of a candidate directly affects EL performance, so they suggest a Densified Knowledge Graph with pseudo-entities as input.

For the most recently released techniques in the field, we have the following. Broscheit, in [36], pondered the implementation of an end-to-end BERT model for the three tasks of Entity Linking. They simplified these tasks to train BERT based on English Wikipedia and fine-tuned it for EL, making it the first EL model without any pipeline or heuristics. The authors of [37] observed that the Transformer models under-perform in comparison to the biLSTM model of Kolitsas [34], even though, generally, BERT models are state of the art. This initiated their research in new ways to implement them in EL, and they came up with CHOLAN. It is a modular transformer architecture that reverts to breaking down the problem into its subtasks, instead of providing a joint solution. They trained two models independently, one for Mention Detection and one for Entity Disambiguation, which makes them flexible and interoperable for different Knowledge Bases.

Then, we reference the remarkable contributions of De Cao et al. [38,39], who proposed two autoregressive approaches (the latter is the equivalent for multilingual purposes). GENRE (Generative ENtity REtrieval) is based on a seq2seq BART architecture to autoregressively generate entity names. This system allows them to capture the relations between NEs and their contexts while reducing the required memory. Finally, there is SPEL—Structured Prediction for Entity Linking [40]. SPEL is a state-of-the-art Entity Linking system that implements innovative concepts to enhance the structured prediction in EL. This includes two detailed fine-tuning stages and a context-aware prediction aggregation approach, minimizing the model’s output vocabulary size and tackling a prevalent issue in Entity Linking systems, where there’s a discrepancy between training and inference tokenization. They presented the best results in the field and also compared the method with GPT-3.5 and GPT-4, which showed how LLMs are still fairly behind in this NLP task, with a significantly increased cost.

The same metrics are used in Entity Linking, namely, precision, recall, and F1, but we have observed that, in contrast to the available results in NER (where almost all papers use F1), in EL, some papers use precision (P). Most Entity Linking approaches use the common Knowledge Database of Wikipedia and the AIDA-CoNLL and TAC or ACE datasets for evaluation. There is a problem in comparing Entity Linking models deriving from the fact that the task is broken down into the subtasks mentioned above, and some papers deal with Entity Linking as a whole, while others with each subtask separately. Table 2 summarizes the main contributions to this sub-field.

Table 2.

Major contributions to Entity Linking.

3.3. Coreference Resolution

Coreference Resolution is a challenging task. Given a text, it tries to identify all indirect references to a certain entity (which is usually a Named Entity). For example, this can be either through the use of pronouns (she, their, etc.) or nominals (e.g., the Prime Minister), and we need to link those with the Named Entity that they refer to. The challenge lies in the fact that it often requires an understanding of the context, either in terms of linguist or “common-sense” knowledge. There are many types of anaphora (around 10, depending on subcategories) that can be found in the written or spoken word, which further increases the challenge.

The extended study of this field started fairly recently and is reflected by the introduction of specified conferences/workshops around it. There was some initial research in the field prior to 2016, but since the introduction of Deep Learning in Natural Language Processing, the field has changed significantly; we focus on these last years of research. It is a crucial task related to many NLP applications, including sentiment analysis (characterizing the sentiment of a text), summarization, translation, question answering, and Named Entity Recognition. Unfortunately, despite its importance, the progress in Coreference Resolution has been the slowest compared to those other fields [43].

Earlier methods revolved around ontologies and the OntoNotes corpus for Entity Linking and Coreference Resolution. The main three categories of coreference solutions are rule-based, Statistical/ML, and Deep Neural Network ones. The first category (with algorithms dating back to 1978) depends on syntactic or semantic rules devised by experts, with the introduction of world knowledge into those rules being an open debate among researchers. The second category of solutions started appearing in the late 1990s, with decision trees, genetic algorithms, and Integer Linear programming being the most prominent methods that overall outperformed the rule-based ones. Finally, Deep Learning approaches began being implemented, further reducing hand-crafted features with the aid of word vectors, being a potent model for representing semantic dependencies between words, and LSTMs and Transformers, producing great results [44].

The four main approaches in the field are Mention-Pair, Mention-Ranking, Entity-Based, and Latent-Tree models. In order, Mention-Pair models are binary classification models that work on pairs of words and were usually solved with clustering algorithms [45]. Mention-Ranking extends the previous model by implementing a rank in a chain of mentions and linking with the items of the highest rank. The first neural end-to-end approach was implemented based on that idea in [46] and takes advantage of bidirectional LSTMs (biLSTMs). Then, Entity-Based models provide additional information on when to merge pair clusters, again with LSTMs being the key components in Deep Learning implementations [47]. Lastly, Latent-Tree models use tree structures for the coreferences, with the most noteworthy contribution being Higher-Order Inference in Coref [48]. They proposed an attention mechanism to improve the span representations and a pruning method to handle long documents.

Joshi et al. made two major contributions to Coref by adapting BERT for this task [49]. As with many others, they built on the foundations set by the team of Kenton [46,48]. First, they fine-tuned the BERT-large pretrained model for Coreference Resolution on the OntoNotes and GAP datasets and replaced the LSTM and ELMo embeddings of c2f-coref with the BERT Transformer, showcasing great results. Then, they advanced their work with SpanBERT [50]. They noticed how, in many cases, for Coreference Resolution, Named Entity Recognition, and other NLP tasks, critical information is contained within spans of words instead of singular work token entities, and it greatly improved the results if they pretrained BERT with spans. They achieved that by differentiating the pretraining tasks of BERT. Instead of masking random tokens, they tried to predict masked spans, and they introduced a new span-boundary objective, so the model predicts the entire span in a set boundary.

The current state of the art in the field is presented in [51]. This paper presents a simplified text-to-text (seq2seq) method for Coreference Resolution that synergizes with modern encoder–decoder or decoder-only models. The method processes a sentence along with the previous context encoded as a string, predicting coreference links. It offers simplicity—by eliminating the need for a separate mention detection and a higher-order decoder. It boasts improved accuracy over prior approaches and harnesses modern generation models that generate text strings. They focused on how to present Coreference Resolution as a seq2seq issue, introducing three transition systems wherein the seq2seq model inputs a sentence and generates an action reflecting a set of coreference links related to the sentence. As of the moment of writing this paper, we have not found any LLM-powered approaches that present significant results in Coreference Resolution.

Domain-specific research in Coreference Resolution is far from being explored. The two domains with active research are the medical field and reference resolution for scientific papers. In general, the work in [52] is a step forward in the right direction. It takes advantage of SpanBERT, mentioned earlier, and introduces the grouping of similar spans into concepts to better adapt BERT to new domains. They also introduced retrofitting loss and scaffolding loss functions, which, thanks to knowledge distance functions, ensure better span representation in the new domain.

There are multiple publicly available datasets for Coref in different medical subdomains, and over the years, there have been rule-based, machine learning, and now Deep Learning models to try and solve this particular challenging task. Some recent remarkable mentions include the works of the first BERT implementation in the BioMedical field [53] pretrained on PubMed data or the work in [54], in which the authors induced knowledge in an LSTM model for improved results with domain-specific features and word embeddings.

Another major problem in the field that we wanted to mention is how biased datasets affect Coreference Resolution. This was directly addressed in the NLP Workshop about Gendered Ambiguous Pronouns (GAP). The works of Rudinger, Webster, and others [55] note that most existing corpora are gender-biased, more frequently resolving male entities (for example, “President” is more likely to be linked with “he” than “she”). They also lack Gendered Ambiguous Pronouns or GAP resolutions that may require real-world knowledge. They released a dataset of ambiguous pronouns derived from Wikipedia for gender fairness, and based on their experiments, Transformer models have the best results.

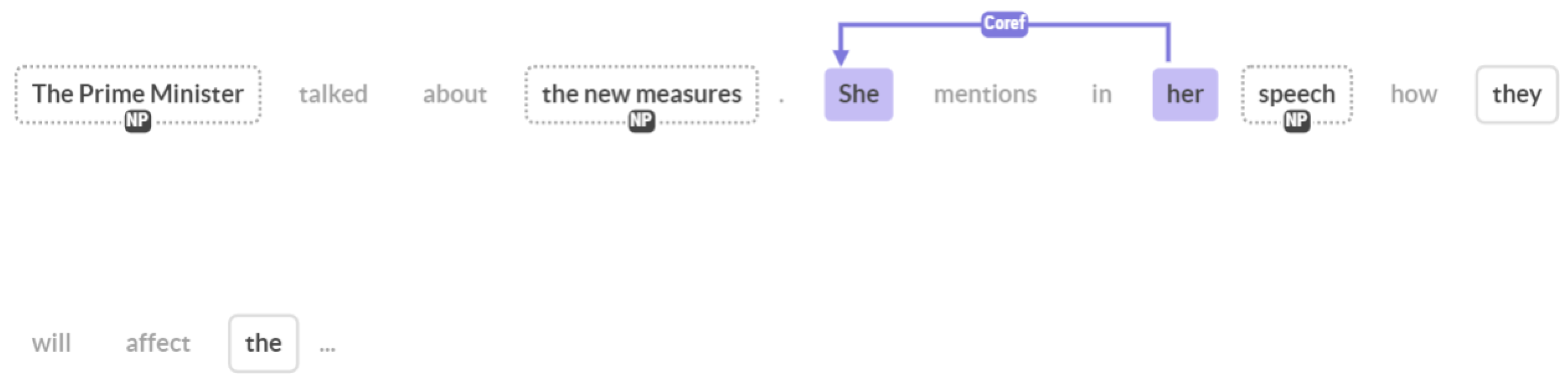

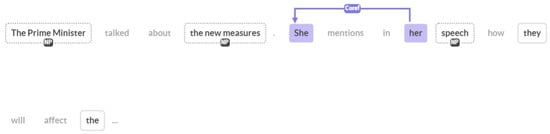

Agarwal et al., in [56], comment on the evaluation for Coreference Resolution. The main metrics used traditionally are MUC, , and CEAF. All of these metrics fail to capture the real efficiency and accuracy of Coref in various ways. First of all, they do not take into consideration the gender-bias perspective. Then, they also do not calculate whether the references are finally resolved to a Named Entity. This problem occurs in chains of references, for example, in Figure 4, if “her” is just linked to “she”, but they are not related to “The Prime Minister”, this will not be reflected in the above metrics, but in reality, the information will not be useful. So, they proposed Named Entity Coreference (NEC) and various metrics to address the above issues. Similar work was presented in [57], where the authors introduce a new Link-Based Entity-Aware (LEA) metric, which considers the importance of each entity that we want to resolve. Regardless of the above observations, and as can be seen in Table 3, most related articles on Coreference Resolution make use of MUC, , and CEAF.

Figure 4.

Coreference Resolution example.

Table 3.

Major contributions to Coreference Resolution.

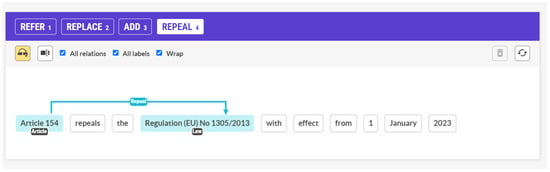

3.4. Relation Extraction

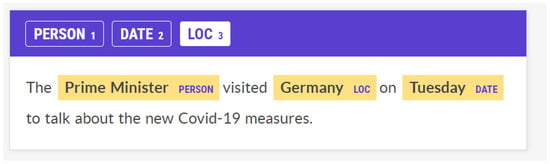

Relation Extraction is the task of finding and semantically categorizing a relationship between two Named Entities in a text. This could either define an event (commonly referred to as Event Extraction) that derives from that relationship or a link between those Named Entities. Furthermore, the task is examined both in terms of a single sentence and for document-level extraction [58]. For example, in Figure 5, between the two legal entities “Article 154” and “Regulation (EU) No 1305/2013”, we want to find the type of relationship between them, whether the Article inserts (ADD), substitutes (REPLACE), revokes (REPEAL), or simply refers (REFER) to the Regulation, and the difference between them is critical. In this specific example, the additional information of the Date (1 January 2023) would also be required to be extracted in a real-life scenario, since it is important to know when a law starts being applied.

Figure 5.

Relation Extraction example.

As with the previous tasks, over the years, a variety of rule-based, supervised, and unsupervised machine learning techniques have been suggested, but in recent years, Deep Learning techniques have taken over [59]. The main methods that are currently examined are variations of CNNs/RNNs, distant-supervised models, knowledge-based methods, and Transformer implementations.

A common approach in the field uses attention-based Deep Neural Networks. In [60], a Convolutional Neural Network is proposed with two levels of attention, one for the entities and one for their relationships. One of the more modern approaches is the combination of the above type of Neural Networks with biLSTM (RNN) in addition to regular DNNs, as presented in [61]. The idea comes from taking advantage of the strengths of each type of Neural Network and stacking them all together, with a CNN being used for its rich feature extraction, a DNN for long distance between words, and a DNN to improve the overall performance.

Distant supervision has been closely examined for Relation Extraction [62]. Distant supervision systems use Knowledge Bases as training data (such as DBPedia or Wikidata) in semi-structured key–value pairs. A recent and robust baseline method is introduced in [63], which consists of three steps, namely, Passage Construction, Passage Encoding, and Passage Summarization, and extends the BERT-based pretrained model. Many researchers have modified BERT models for the task of Relation Extraction. The first BERT implementation for this task, R-BERT, is introduced in the work of Wu and He [64], which takes advantage of entity-level information and achieves state-of-the-art results. Another configuration consists of a stack of a BERT model and biGRU (bidirectional Gated Recurrent Unit), as presented in [65]. They use the biGRU to extract the important features from the results of BERT and to obtain the position information in a sentence (useful in long sentences).

According to our research, the current state-of-the-art approaches progress based on the previous ideas. First, the REBEL architecture [66] is an end-to-end autoregressive seq2seq model for Relation Extraction. The authors also released the corresponding distantly supervised dataset, and they aim to provide a flexible and easy-to-adjust approach in terms of both domains and document- or sentence-level RelEx. The team behind [67] tested how the Transformer architecture can be applied to Relation Extraction and devised a novel way to do so. They established the Matching The Blanks method, which is similar to the Masked Language Modeling of BERT, where they replace entities with “Blank” statements and try to find relationships in that environment. KGPool is another novel method [68] for RelEx using Knowledge Graphs. First, it examines the way knowledge is inserted in Graph Convolution Networks (CGNs), and then it uses a self-attention mechanism to properly select sub-graphs of information from the Knowledge Graph (the first attempt in Relation Extraction).

Xu et al. [69] presented a robust approach for document-level RelEx. They noted how structure is important in document-level dependencies and that graph models are lacking in that regard. Instead, they suggested a Structured Self-Attention Network (SSAN) with a modified attention mechanism for the effective representation of structure dependencies. The currently best approach in L RelEx is DREEAM [70]. DREEAM (Document-level Relation Extraction with Evidence-guided Attention Mechanism) is a method that is efficient in memory use and utilizes evidence data as supervision input. This assists the attention mechanisms of the DocRE framework to assign high weights to the evidence. Secondly, they put forth a self-training approach for DREEAM to acquire Entity Resolution (ER) from automatically created evidence based on extensive data, eliminating the need for annotations.

Out of the four examined NLP tasks, LLMs have had the biggest impact so far in Relation Extraction, especially in zero- or few-shot learning. Two of the most recent contributions that we want to cite are QA4RE [71] and GoLLIE [72]. In the former, the authors mention that the subpar RelEx performance of instruction-tuned LLMs may stem from the low occurrence of RelEx tasks in instruction-tuning datasets. To combat this, they suggest the QA4RE framework, which integrates RelEx with the frequently appearing multiple-choice question answering (QA). They frame the input sentence as a question and potential relation types as multiple-choice answers, enabling LLMs to conduct RelEx by selecting the correct relation type.

GoLLIE (Guideline-following Large Language Model for IE) enhances model performance on unseen schemas by focusing on guidelines’ details. They used a Python-code-based representation for both the model’s input and output, providing a human-readable structure and addressing common issues with natural language instructions. It allows any information extraction task to be represented in a unified format. The key contribution here is the incorporation of the guidelines in the inference process for improved zero-shot generalization. They standardized the input format, with label definitions as class docstrings and candidates as principal argument comments. To ensure that the model follows the guidelines, they introduced a variety of noise during training, preventing the model from associating particular datasets or labels.

In specific fields, once again, the medical domain receives attention, where we have already seen results for Relation Extraction. The work in [73] is a thorough survey presenting the current modern Neural Network approaches in the field. Another interesting approach is given in [74]. ReTrans, as they call it, is a transfer learning framework that takes advantage of existing Knowledge Bases to deal with relation extraction in new domains.

As we stated, it is not uncommon for NLP researchers to try and tackle tasks in relative groups. So, the problems of Entity Linking, Coreference Resolution, and Relation Extraction have been examined for joint solutions. A great and up-to-date survey on the field can be found in [75] and is noted as the only survey addressing Deep Learning techniques in information extraction (IE). They start by presenting the main datasets used in NER and the various methods used to solve the problem, and similarly for Relation Extraction. Some other noteworthy works in joint approaches are the encoder–decoder model for Entity and Relation Extraction in [76], where the authors describe two methods, one with a representation scheme for tuples and one for pointer-network-based decoding. Then, there is the work of Zaporojets et al. [77] for Entity Linking and Coreference Resolution for documents, where the proposed method translates the problem to a Maximum Spanning Tree (MST) problem, making use of Span-BERT.

Relation Extraction has been examined quite a lot over the years, but the developed methods focus on heavily specific and curated datasets with strict and clear definitions of Named Entities and relationships [78]. This is good for examining the approaches in theory, but in reality, the problems are much more complex, so it is hard to apply these methods efficiently. This also makes it harder to compare these methods, and this is confirmed by our observations presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Major contributions to Relation Extraction.

4. Multilingual and Low-Resource-Language NLP

Unfortunately, most languages other than English, Spanish, and Chinese have very few related resources for Natural Language Processing. We refer to these as low-resource languages. In examining various research results in the field, we have observed that the efficiency of general NLP techniques, when applied in other domains and languages, is significantly lower. Moreover, papers that touch on cross-lingual approaches, more often than not, test their models on Spanish or Chinese (both high-resource languages), highlighting the importance of research in the field [81].

As a result, in the past few years, we have observed increased interest in research for other languages to address this directly. Many papers have been written in the past years alongside the advent of Deep Learning in NLP, which is a direct indication that it is becoming more and more relevant. We noticed that most papers released before this last period (2016–2022) have been severely outdated in terms of both the tools and methods used.

In the past couple of years, we have observed a growth in papers for cross-lingual Named Entity Recognition. The research for these subjects is really important for low-resource languages [82]. First of all, the team of BERT has released a multilingual version, mBERT, and according to the experiments in [83], it generalizes fairly well, but its shortcomings derive from multilingual word representations, highlighting the significance of language-specific embeddings. A remarkable approach to cross-lingual NER is presented in [84] by a Microsoft team. They had industry needs in mind when they proposed a Reinforcement Learning and Knowledge distillation framework to transfer knowledge from an initial weak English model to the new non-English model. They mark the weakness of existing cross-lingual models in real-life applications (especially search engine-related tasks) and present state-of-the-art results.

Because Entity Linking functions with the help of Knowledge Bases, cross-domain and language implementations are not considered. That would require a KB with data from multiple domains, alongside an advanced system that can identify and link entities to each of these domains, and based on our research, we have not seen any records of such a work. We have only found a select few papers about cross-lingual EL [85]. They mention how challenging this task is for low-resource languages. The minimum requirements for such a system to work are an English KB (like Wikipedia), a source language KB, multilingual embeddings and bilingual entity maps, and the last two are especially rare for many languages. DeepType is the most interesting related architecture [41]. The authors integrated symbolic information into the reasoning process of the Neural Network with a type system. They translated the problem to a mixed-integer one, and they showed that their model performed well in multilingual experiments.

Similarly, for most languages other than English, there are very few resources and research papers for Coreference Resolution. There are some for widely spoken languages such as Chinese, Japanese, and Arabic, but for most low-resource languages, there is no progress whatsoever. A common approach to counter these issues is multilingual or cross-lingual systems [86]. A recent example in the research of these methods for Coreference Resolution is presented here [87]. These methods perform based on the basics of transfer learning, where they are usually pretrained in English (which has a plethora of word embeddings, corpora, and pretrained models), and try to transfer that knowledge to other languages. A transfer learning method for cross-lingual Relation Extraction is proposed in [79], which capitalizes on Universal Dependencies and CNNs to achieve great Relation Extraction in low-resource languages.

The main issue for any low-resource language in the current state of Deep Learning is that the latest advancements in the field, namely, the large pretrained Transformer-based models (like BERT), cannot be transferred reliably or efficiently. Both the word embeddings (a major preprocessing part) and the vast amount of data used to pretrain the models are in English. This makes most of the BERT variants (not specifically trained in another language) unusable in other domains, and their performance diverges greatly from that reported in state-of-the-art works [88]. Consequently, LSTM implementations in these subdomains often present better results in subdomains/other languages than BERT. We believe that it is important to consider this and research new ways to either adapt large pretrained models more profitably or focus more on cross-lingual and cross-domain models or even evaluate the usefulness of these models as a whole in these cases [89].

In regard to the LLM implementations in a cross-lingual environment, the most promising work can be found in [90]. In that work, the authors mention how recent studies suggest that visual supervision enhances LLMs’ performance in various NLP tasks. In particular, the Vokenization approach [91] has charted a new path for integrating visual information into LLM training in a monolingual context. Building on this, they crafted a cross-lingual Vokenization model and trained a cross-lingual LLM on English, Urdu, and Swahili. Their experiments show that visually supervised cross-lingual transfer learning significantly boosts performance in numerous cross-lingual NLP tasks, like cross-lingual Natural Language Inference and NER, for low-resource languages.

In Table 5, we present the gathered papers for our NLP subtasks. Most cross-lingual methods used for low-resource languages approach the issue similarly. They use the English part of Wikipedia (or WikiData) as their main language for training, along with the desired language to transfer the knowledge to. They often combine that with bilingual entity maps (especially when we have Knowledge Bases) to map entities between source and destination languages. Multilingual embeddings may also contribute significantly to the process by mapping the vectors of the same word in different languages and clustering them together. The results presented in Table 5 follow the same principles, so the trained language is commonly English, and we only state the destination language for the task. Below the table, we provide the interpretation of the language codes used for the tests in each paper.

Table 5.

Major contributions in multilingual NLP.

5. Legal NLP

As we mentioned in Section 2, Legal Data and Informatics have several challenges that are exclusive to or more prominent in the domain. In this section, we present the recent literature published to address these issues.

For the legal domain, NER is the most researched NLP task, as it is the primary one [92]. Most common Named Entities in the field include Person/Title (e.g., Judge), Date, Organization, and then the different types of law documents, which differ depending on the use case or country. From the various approaches that have been proposed, we chose the following as the most promising recent ones.

A noteworthy contribution in the field is LEGAL-BERT [31]. It is the first BERT implementation in the legal domain. Chalkidis and his colleagues state the numerous challenges they faced. They are greatly concerned with the proper configuration of the many variables and hyper-parameters used in BERT implementations. They suggest that, in many cases, small models can prove to be more efficient while providing competitive results, counter to the current trend of extremely big models. They developed three different models for BERT based on the pretraining steps that they follow. They trained their models on 12GB of English legal text, and after testing and comparing their models, they concluded that adapting BERT to new domains requires either extensive further training or even pretraining from scratch.

The team of [93] developed a NER architecture for legal documents in German. They prepared a manually annotated dataset with German court decisions with 19 NEs (that fall under the four that we just mentioned). They then suggested a biLSTM-CRF model to achieve state-of-the-art NER results. A similar work is submitted in [94]. The authors fine-tuned a widely used German BERT language model on a Legal Entity Recognition (LER) dataset that was also used by the previous authors. To prevent overfitting, they undertook a stratified 10-fold cross-validation. Their results showed that the fine-tuned German BERT outperformed the BiLSTM-CRF+ model on the same LER dataset.

We have also developed an efficient Named Entity Recognition model for Greek Legislation [95]. As cited in the paper, there are very few NER models in Greek, and of course, they do not find the very specialized entities that we are looking for. Our approach was to manually annotate a fairly small corpus of Greek legal documents (around 4000 paragraphs out of 150 documents) and fine-tune a generic non-BERT Greek NER model with the help of these data. Throughout the process, we confronted the many challenges described throughout this paper, with really promising results in the end. Based on our research and implementation, we have drawn several key conclusions. Firstly, having a well-defined annotation schema that avoids overlapping entities and class imbalance is crucial. Secondly, active learning significantly reduces the manual annotation effort over time. Thirdly, to avoid overfitting, it is necessary to retrain the model from scratch. Finally, despite having a much smaller annotated dataset than the BERT models, we achieved satisfactory results that outperformed the larger models, mainly because of the quality of our annotations.

The authors of [96] worked on extracting entities for Mergers and Acquisitions. The issue they wanted to solve is more specific than NER, because in contracts, there may be many Named Entities, but the relevant ones needed for their work are a specific subset. The architecture presented was used in production, and the dataset they tested on was curated by law professionals and not by machine learning techniques. They chose to develop a binary classifier instead of a multi-label one because of the limitations imposed by the users and the large data imbalance. They propose two strategies. A baseline single layer based on CRFs with three variations (according to the sentences trained) and a two-layer strategy that expands on the previous one by training a sentence-level CRF, again with three similar variations.

Entity Linking works in the legal domain are scarce. A common Knowledge Base developed in the domain is Legal Knowledge Interchange Format (LKIF) [97]. In [98], the authors present a general review on the uses of ontologies in Legal Informatics. They analyzed the term ontology and its significance in specific domains and proposed an open automated system for providing EU countries with legal information based on ontologies. In [99], they jointly tackled Named Entity Recognition and Linking with the use of ontologies. They semantically represented legal entities and tried to map YAGO to LKIF ontologies by capitalizing on Wikipedia data. Since the legal domain does not have an extensive training corpus, Named Entity Linking with transfer learning is considered as a solution. In [42] specifically, the authors transferred knowledge from the AIDA-CoNLL dataset (a widely used EL dataset) to the EURLEX corpus (which has EU legislation), but in our opinion, they did not produce any exciting results.

For Coreference Resolution in the legal domain, the only related works that we found in our extensive research over the past 5 years are the works of Gupta et al. [100] and Ji et al. [101]. First, they suggested a supervised machine learning process to identify references to participants in court judgments. Due to the lack of legal-specific datasets, they decided to map their entities to the ACE dataset, and their results show that more similar approaches should be examined. The second work explored the problem of Speakers Coreference Resolution (SCR) in court records. They noted how existing models cannot be implemented in the field as is, due to the highly knowledge-rich nature of legal documentation. They proposed an ELMo pretrained biLSTM model with attention, in parallel with a graph containing entities with “mentioned” relationships. Both of these papers focus on very specific problems of legal Coreference Resolution, and as such, there is much room for research in this field that we deem necessary for the future of Legal Informatics.

In the legal domain, Relation Extraction is an important task that can be used to either find connections between legislative articles or events mentioned in legal documents. The team of Dragoni et al. [102] suggested a combination of NLP approaches for rule extraction, which is a task closely related to Relation Extraction. They combined ontologies to identify the structure and linguistic elements of legal documents with the Stanford Parser for the grammatical features and a Combinatory Categorial Grammar tool to extract logical dependencies between words. Relation Extraction was also considered for regulatory compliance in [103], alongside fact orientation to create a domain model and a dictionary.

Event Extraction in legal data is also of relevance. It is usually needed in court decisions, as stated in [104], where the task of finding and connecting all the relevant events in a case was extremely time-consuming. They tested different pretrained models and concluded that it is better to fine-tune a large existing model with domain-specific knowledge rather than training from scratch on a smaller domain corpus. Event Extraction in a Chinese legal text environment is presented in [105], where the authors propose a combination of BERT and biLSTM-CRF for character vectors and rule extraction, respectively. Finally, a joint entity and Relation Extraction system for Chinese legal documents is described in [80]. Based on a sequence-to-sequence (seq2seq) framework, they developed the Legal Triplet Extraction System (LTES) to extract entities and their relationships in drug-related criminal cases.

The use of cross-domain knowledge in legal data is not a considered tactic. The peculiarities and specifications of legal data make it hard for general-purpose knowledge to be transferable. Nevertheless, we have to mention the work of [106], where the authors further trained a RoBERTa model on three different (small) legal datasets and suggested, based on their experiments, that these language models gain robustness when trained on multiple datasets.

Nowadays, multilingual law processing is becoming more necessary than ever, especially in the European Union, where all country members have their respective laws and languages but also have to adhere to the EU legislation (referred to as National Implementing Measures or National Transposition) [107]. The research, however, has only started to bear fruits. We want to mention here the recent seminal works of Chalkidis et al. [108,109,110].

Throughout the combined efforts of these papers, the authors aimed to improve multilingual legal NLP capabilities through a Transformer architecture and LLMs. To measure progress in the legal NLP field, they created a challenging multilingual benchmark known as LEXTREME based on 24 languages across 11 legal datasets. This new benchmark tool identified significant room for improvement in current models [108]. To facilitate training LLMs, the authors released a large, high-quality multilingual corpus called MULTILEGALPILE. This corpus contains diverse legal data sources in 24 languages from 17 jurisdictions. They also pretrained RoBERTa models, setting a new state of the art on LEXTREME [109].

They also introduced legal-oriented Pretrained Language Models (PLMs) trained on a newly released multinational English legal corpus, LeXFiles. The effectiveness of these models was evaluated on a newly released legal knowledge probing benchmark, LegalLAMA. Analysis revealed a strong correlation between probing and upstream performance for related legal topics and identified model size and prior legal knowledge as key drivers of downstream performance [110]. The authors anticipate that their collective effort, encompassing new tools, datasets, and benchmarks, will accelerate the development of domain-specific PLMs and advance legal NLP capabilities. The data, trained models, and code developed during this work are openly available, fostering transparency and encouraging future research in this domain.

The last thing that we want to mention is the current place of LLMs and GPT in the domain. From the results provided throughout this survey, and as also supported in [111], they still fall short compared to the state of the art in tackling the demanding Natural Language Processing tasks in specialized domains like law and in non-English languages. First, these models are largely trained on general-domain data and may not fully understand the specific terminology, structures, and nuances present in legal texts. This limits their ability to accurately predict, generate, or interpret legal language. Second, most available training data are in English, which means that these models are likely to perform poorer on non-English texts due to the lack of sufficient training data. Nevertheless, they still perform reasonably well, even through zero- or few-shot learning, and will probably reach their competition soon.

Table 6 collects the main works on Legal Informatics that, in our opinion, are essential to our work and set the current state of the art that we aim to improve in the future. Contrary to all the previous tables, we can see that, in this case, each paper uses its own custom datasets and experiments, making it hard to replicate and compare them properly. We hope that, in the future, with the generation of the recent domain-specific benchmarks and datasets, the testing and comparison of legal NLP approaches will be improved. Beneath the table, we give brief details for each of the datasets used in the mentioned works.

Table 6.

Major contributions to legal NLP.

6. Conclusions

This paper has conducted a thorough exploration of Natural Language Processing (NLP), with a particular focus on Named Entity Recognition (NER), Entity Linking, Relation Extraction, and Coreference Resolution. These aspects are vital for constructing a legal citation network and law consolidation system. We initially delved into modern research on each of these tasks individually, followed by an exploration of their application in the legal domain.

Legal documents, with their interconnectedness, constant evolution, and complex structure, present a multifaceted problem. The three key variables are the insertion, repeal, and substitution of laws. Insufficient datasets and the need for version control only add to the complexity.

Despite significant recent research in NER within this domain, critical gaps remain, particularly regarding disambiguating titles, resolving nested entities, and addressing coreferences, lengthy texts, and machine-inaccessible PDFs. Both Coreference Resolution and Relation Extraction are areas that should be further explored, as their results are noticeably lower than those in NER. The meaningful integration of ontologies and transfer learning for relation and rule extraction offers interesting directions for future research.

Our work indicates that model efficiency and high-quality annotations and datasets could lead to substantial advancements in these areas. While there are legal limitations to what can be achieved in providing openly accessible data, our findings underscore the urgent need for such datasets. These insights should guide future attempts in the legal domain and in broader managerial practices.

This need has created a new field necessary for research: the intersection of Privacy, Legal, and Natural Language Processing fields [19,112]. This is another field that interests us, and we see that many researchers share our interest, especially since the application of the General Data Protection Regulation. Despite its importance, it is still in its early stages of research, as the junction of these fields highlights new issues and requires new techniques to be developed, presumably combining Deep Learning, LLMs, and Hiding techniques [113].

Furthermore, the NLP techniques encountered do not perform well when applied to languages that are less widely spoken than English, Spanish, and Chinese due to a shortage of related resources. Cross-lingual models, such as mBERT, offer potential pathways for addressing these challenges, yet the roles of language-specific embeddings require further research.

Future advancements in NLP applied to legal and especially to low-resource-language texts depend on three main objectives: creating proper and large datasets, refining the accuracy of current models, and unearthing and leveraging new techniques, with Large Language Models gaining increasing prominence. While these new models are yet to reach current standards, their swift progress, along with the creation of expansive legal datasets such as LEXTREME, suggest a promising route toward optimal outcomes in this field.

Our future goals include researching the best way to develop an end-to-end model for low-resource languages in the legal domain to create a law version system. We think the best way to approach this is by finding the best-suited solution for each of the four main tasks and building a joint pipeline model. We have already started with the NER pipeline and look to extend it to include Coreference Resolution and Relation Extraction. Additionally, we are keenly aware of the privacy concerns surrounding Deep Learning and especially LLMs and the law domain, and we intend to explore innovative ways to merge these fields.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.K. and E.S.; software, P.K.; validation, E.S. and V.S.V.; writing—original draft, P.K.; writing—review and editing, E.S. and V.S.V.; visualization, P.K. and E.S.; supervision E.S. and V.S.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work has been partly supported by the University of Piraeus Research Center.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| NLP | Natural Language Processing |

| IE | Information extraction |

| NER | Named Entity Recognition |

| EL | Entity Linking |

| RelEx | Relation Extraction |

| Coref | Coreference Resolution |

| HMM | Hidden Markov Models |

| SVM | Support Vector Machines |

| CRF | Conditional Random Field |

| DNN | Deep Neural Networks |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| RNN | Recurrent Neural Network |

| LSTM | Long Short-Term Memory |

| BERT | Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers |

| LLM | Large Language Model |

References

- Collobert, R.; Weston, J.; Bottou, L.; Karlen, M.; Kavukcuoglu, K.; Kuksa, P. Natural Language Processing (Almost) from Scratch. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2011, 12, 2493–2537. [Google Scholar]

- Hedderich, M.A.; Lange, L.; Adel, H.; Strötgen, J.; Klakow, D. A survey on recent approaches for natural language processing in low-resource scenarios. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2010.12309. [Google Scholar]

- Conrad, J.G.; Branting, L.K. Introduction to the special issue on legal text analytics. Artif. Intell. Law 2018, 26, 99–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boella, G.; Caro, L.D.; Humphreys, L.; Robaldo, L.; Rossi, P.; Torre, L. Eunomos, a Legal Document and Knowledge Management System for the Web to Provide Relevant, Reliable and up-to-Date Information on the Law. Artif. Intell. Law 2016, 24, 245–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalkidis, I.; Nikolaou, C.; Soursos, P.; Koubarakis, M. Modeling and Querying Greek Legislation Using Semantic Web Technologies. In Proceedings of the The Semantic Web, Portorož, Slovenia, 28 May 28–1 June 2017; pp. 591–606. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, H.; Xiao, C.; Tu, C.; Zhang, T.; Liu, Z.; Sun, M. How Does NLP Benefit Legal System: A Summary of Legal Artificial Intelligence. In Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Online, 5–10 July 2020; pp. 5218–5230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsarapatsanis, D.; Aletras, N. On the Ethical Limits of Natural Language Processing on Legal Text. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL-IJCNLP 2021, Online, 1–6 August 2021; pp. 3590–3599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodfellow, I.; Bengio, Y.; Courville, A. Deep Learning; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016; Available online: http://www.deeplearningbook.org (accessed on 3 March 2023).

- Raffel, C.; Shazeer, N.; Roberts, A.; Lee, K.; Narang, S.; Matena, M.; Zhou, Y.; Li, W.; Liu, P.J. Exploring the Limits of Transfer Learning with a Unified Text-to-Text Transformer. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2020, 21, 5485–5551. [Google Scholar]

- Hochreiter, S.; Schmidhuber, J. Long Short-term Memory. Neural Comput. 1997, 9, 1735–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, L.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is All You Need. In Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Red Hook, NY, USA, 4–9 December 2017; pp. 6000–6010. [Google Scholar]

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 4 June 2019; Volume 1 (Long and Short Papers), pp. 4171–4186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Ott, M.; Goyal, N.; Du, J.; Joshi, M.; Chen, D.; Levy, O.; Lewis, M.; Zettlemoyer, L.; Stoyanov, V. RoBERTa: A Robustly Optimized BERT Pretraining Approach. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1907.11692. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z.; Dai, Z.; Yang, Y.; Carbonell, J.G.; Salakhutdinov, R.; Le, Q.V. XLNet: Generalized Autoregressive Pretraining for Language Understanding. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1906.08237. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, T.B.; Mann, B.; Ryder, N.; Subbiah, M.; Kaplan, J.; Dhariwal, P.; Neelakantan, A.; Shyam, P.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A.; et al. Language Models are Few-Shot Learners. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2005.14165. [Google Scholar]

- OpenAI. GPT-4 Technical Report. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.08774. [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhery, A.; Narang, S.; Devlin, J.; Bosma, M.; Mishra, G.; Roberts, A.; Barham, P.; Chung, H.W.; Sutton, C.; Gehrmann, S.; et al. PaLM: Scaling Language Modeling with Pathways. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2204.02311. [Google Scholar]

- Touvron, H.; Lavril, T.; Izacard, G.; Martinet, X.; Lachaux, M.A.; Lacroix, T.; Rozière, B.; Goyal, N.; Hambro, E.; Azhar, F.; et al. LLaMA: Open and Efficient Foundation Language Models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2302.13971. [Google Scholar]

- Goanta, C.; Aletras, N.; Chalkidis, I.; Ranchordas, S.; Spanakis, G. Regulation and NLP (RegNLP): Taming Large Language Models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2310.05553. [Google Scholar]

- Lample, G.; Ballesteros, M.; Subramanian, S.; Kawakami, K.; Dyer, C. Neural Architectures for Named Entity Recognition. In Proceedings of the 2016 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, San Diego, CA, USA, 12–17 June 2016; pp. 260–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, I.; Asai, A.; Shindo, H.; Takeda, H.; Matsumoto, Y. LUKE: Deep Contextualized Entity Representations with Entity-aware Self-attention. In Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP), Online, 16–20 November 2020; pp. 6442–6454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Jiang, Y.; Bach, N.; Wang, T.; Huang, Z.; Huang, F.; Tu, K. Automated Concatenation of Embeddings for Structured Prediction. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2010.05006. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Jiang, Y.; Bach, N.; Wang, T.; Huang, Z.; Huang, F.; Tu, K. Improving Named Entity Recognition by External Context Retrieving and Cooperative Learning. In Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (Volume 1: Long Papers), Online, 1–6 August 2021; pp. 1800–1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Xu, Y.; Yu, T.; Dai, W.; Ji, Z.; Cahyawijaya, S.; Madotto, A.; Fung, P. CrossNER: Evaluating Cross-Domain Named Entity Recognition. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2012.04373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nozza, D.; Manchanda, P.; Fersini, E.; Palmonari, M.; Messina, E. LearningToAdapt with word embeddings: Domain adaptation of Named Entity Recognition systems. Inf. Process. Manag. 2021, 58, 102537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, C.; Yu, Y.; Jiang, H.; Er, S.; Wang, R.; Zhao, T.; Zhang, C. BOND: BERT-Assisted Open-Domain Named Entity Recognition with Distant Supervision. In Proceedings of the 26th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, Virtual Event, 6–10 July 2020; pp. 1054–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]