Abstract

Deep learning solutions can be used to classify pathological changes of the human retina visualized in OCT images. Available datasets that can be used to train neural network models include OCT images (B-scans) of classes with selected pathological changes and images of the healthy retina. These images often require correction due to improper acquisition or intensity variations related to the type of OCT device. This article provides a detailed assessment of the impact of preprocessing on classification efficiency. The histograms of OCT images were examined and, depending on the histogram distribution, incorrect image fragments were removed. At the same time, the impact of histogram equalization using the standard method and the Contrast-Limited Adaptive Histogram Equalization (CLAHE) method was analyzed. The most extensive dataset of Labeled Optical Coherence Tomography (LOCT) images was used for the experimental studies. The impact of changes was assessed for different neural network architectures and various learning parameters, assuming classes of equal size. Comprehensive studies have shown that removing unnecessary white parts from the input image combined with CLAHE improves classification accuracy up to as much as 4.75% depending on the used network architecture and optimizer type.

1. Introduction

OCT (Optical Coherence Tomography) devices have made revolutionary changes in ophthalmological diagnostics of the anterior and posterior segments of the human eye [1]. Visualization of the retinal structure allows for a precise assessment of changes, especially those related to AMD (Age-related Macular Degeneration) [2].

OCT devices are equipped with computer software that allows not only showing single or multiple sections of retinal structures around the macula or optic nerve, but also to segment layers, which can be performed using graph theory or machine learning techniques. Based on the segmented layers, it is possible to parameterize selected areas and, thus, assess the progression of degenerative changes associated with individual diseases [3].

Attempts are currently being made to apply artificial intelligence techniques using deep neural networks (NN) for computer classification of retinal diseases [4]. Experimental studies use various datasets, which often require critical verification and improvements for incorrect image acquisition, as well as the unification of the histogram distributions. Such discrepancies result from the specificity of the operation of OCT devices made by different manufacturers. The aspects of such preprocessing and its impact on classification efficiency are presented in this article.

The main contributions of the authors presented in the article are as follows:

- Evaluation of the luminance distribution of OCT B-scans and appropriate cropping to eliminate abnormal areas;

- Analysis of the impact of histogram equalization using the standard method and Contrast-Limited Adaptive Histogram Equalization (CLAHE);

- Comprehensive evaluation of classification performance for a set of different neural networks with balanced class sizes.

Assessments and conclusions are based on the LOCT dataset.

2. Related Works

2.1. Imaging Techniques

Artificial intelligence methods in the diagnosis of degenerative changes in the human retina are currently used for two types of imaging: images taken with a fundus camera or B-scans taken with OCT devices.

Fundus images are of very high resolution and are acquired very quickly. One of the most popular datasets with such images is the open-source multi-labeled Retinal Fundus Multi-Disease Image Dataset (RFMiD) [5], where 60% of the dataset—i.e., 1920 images (covering 40 classes)—are publicly available. The multi-layer neural network EyeDeepNet proposed [6] for eight classes achieves an accuracy of 76.04% using SGD (Stochastic Gradient Descent) and the fixed learning rate of 0.001. It should be noted that the fundus camera captures 2D images of the retinal surface, which lack the depth detail necessary to assess deeper retinal structures. However, commercial fundus camera solutions often already have built-in screening software based on AI solutions. For example, the iCare ILLUME solution helps detect the early signs of Diabetic Retinopathy (DR), Age-related Macular Degeneration (AMD), and glaucoma (GLC).

OCT devices (typically, Spectral-Domain Optical Coherence Tomography—SD-OCT), unlike fundus cameras, allow for 3D imaging. Thus, a set of OCT B-scans provides cross-sectional images of the retina, allowing detailed visualization of its layers (e.g., nerve fiber layer, photoreceptor layer, and retinal pigment epithelium). This depth of information enables clinicians to see beneath the surface of the retina and identify subtle pathologies.

2.2. Related Datasets

Although SD-OCT has become a gold standard in eye imaging today, the number of datasets and their sizes (number of classes and number of images in a given class) is not very large. A list of datasets can be found in the papers [4,7] (c.f. Table 1 in both papers).

From the point of view of the classification process that uses deep neural networks, the most valuable seem to be three datasets: OCTID [8], OCTDL [7], and LOCT [9].

The OCT Image Database (OCTID) consists of 572 B-scans of five classes, including 206 NORMAL (Healthy Controls), 107 DR (Diabetic Retinopathy), 102 MH (Macular Hole), 102 CSR (Central Serous Retinopathy), and 55 AMD (Age-related Macular Degeneration) retinal images. The images were acquired using a raster scan protocol with a 2 mm scan length, captured using a Cirrus HD-OCT (Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany) device. B-scans have 750 × 500 pixels (resized from the original 1024 × 512 pixels) and are saved in JPEG format [8].

The OCTDL (Optical Coherence Tomography dataset for Deep Learning methods) consists of 2064 B-scans in the following seven categories: AMD—1231 images, NORMAL—332 images, EM (Epiretinal Membrane)—155 images, DME (Diabetic Macular Edema)—147 images, RVO (Retinal Vein Occlusion)—101 images, VID (Vitreomacular Interface Disease)—76 images, and RAO (Retinal Artery Occlusion)—22 images. The B-scan OCT images were acquired with an Avanti RTVue XR (Optovue, Fremont, CA, USA) using a raster scanning protocol with dynamic scan length and image resolution. B-scans have different resolutions; images are 444 to 1270 pixels wide (average 917.2 px), 127 to 710 pixels high (average 335.6 px), and are saved in JPEG format [7].

The LOCT (Labeled Optical Coherence Tomography, sometimes also called “Kermany”) dataset is the largest and, therefore, the most popular collection of B-scans and includes (depending on dataset version 1, 2, or 3) from 84,484 up to 108,309 images. The current dataset version contains scans of four classes, namely: NORMAL—51,140 images, CNV—37,205 images, DME—11,348 images, and DRUSEN—8616 images. The B-scan acquisition was performed using the Spectralis OCT (Heidelberg Engineering, Heidelberg, Germany) imaging system and saved in JPEG format [10]. The LOCT dataset split into training and test sets is also proposed by the authors.

2.3. OCT-Based Retinal Disease Classification Using Neural Networks

The classification of retinal pathologies from OCT images was of interest when ophthalmic OCT devices, especially SD-OCT solutions, became widespread. Early classification solutions were based on investigating discriminative characteristics that describe the texture or shape of a given pathology (for example, fluid-filled regions). Automatic classification of OCT images was based on local binary pattern features [11] or multiscale histograms of oriented gradient descriptors with a support vector machine (SVM)-based classifier [12]. A review of OCT-based screening methods and diagnosis of human retinal diseases can be found in [13].

Currently, most solutions are based on deep learning solutions because of their effectiveness. Different architectures of Convolutional Neural Networks (presented in Section 3.3) can be used for classification of OCT B-scans. In the case of the LOCT dataset, initially, the following accuracies were achieved for transfer learning using InceptionV3 architecture [9]: 82.2% for Drusen, 86.9% for CNV, 91.6% for DME, and 93.3% for NORMAL. Using a Lesion-Aware Convolutional Neural Network (LACNN) improved these to average accuracy levels of 93.6% for Drusen, 92.7% for CNV, 96.6% for DME, and 97.4% for NORMAL [14].

The authors of some publications indicate that the improvement of the classification process efficiency can be achieved by additional augmentation of input data. In article [15], the authors recommend using only basic image manipulations such as mirror image, rotation, aspect ratio change, histogram equalization, Gaussian blur, and sharpen filter. According to the authors, increasing the number of training files 48 times allows for achieving an accuracy of up to 99.90%. Similar results were obtained in article [16], which concluded that the dataset had been preprocessed and enhanced for brightness and the suppression of noise. Unfortunately, in the above two articles, the detailed augmentation parameters or preprocessing specifications were not provided.

In article [17], where the CLAHE-Capsnet network is proposed, the authors use Contrast-Limited Adaptive Histogram Equalization for classification purposes, and the experiments for two datasets (LOCT and OCTID) give better results. Here, neither the histogram equalization parameters nor the software repository were provided. In the case of medical images, it is reasonable to ask whether it is worth performing normalization and intensity level reduction operations [18]. Can such operations improve the effectiveness of classification?

Considering related works, our study aims to check exactly what the histograms look like, how they can be improved, and whether the proposed improvement methods affect classification efficiency. In the experimental studies, a number of neural network architectures and their parameters were tested. The studies used an even number of B-scans in each class to better observe the subtle impact of image modification. For all experiments, publicly available software was prepared and placed on the GitHub repository: https://github.com/krzyk87/OCTclassification (accessed on 16 December 2024).

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Dataset

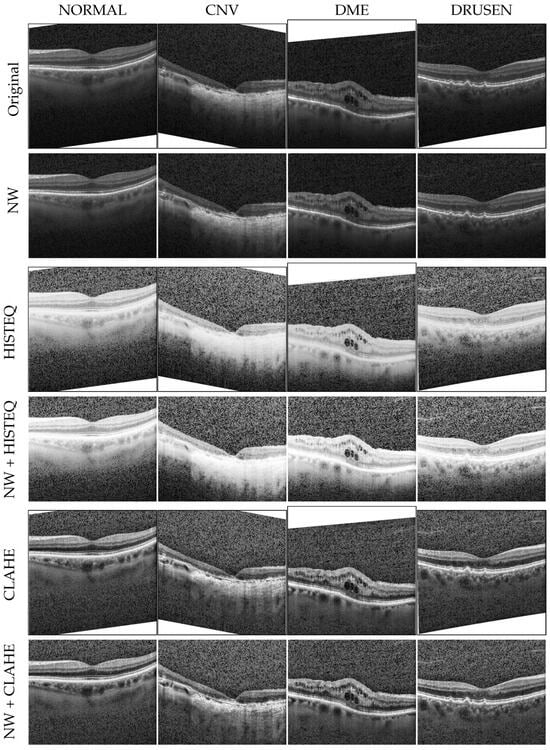

The experiments described in this article utilized a publicly available LOCT dataset (version 2) [10], obtained with a Spectralis OCT device (Heidelberg Engineering, Heidelberg, Germany). We selected 32,000 training samples from 84,484 OCT B-scan images (8000 for each of CNV, DME, DRUSEN, and NORMAL (i.e., healthy controls) classes). The testing subset contains 1000 images in total (250 images per class). From those, 32 images (8 per class) were used for the validation step at the end of each training epoch, as a dataset division suggested in [19]. This setup of experiments was previously described in [20]. Examples of original OCT B-scans selected in this research are presented in the first row of Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Examples of OCT B-scans with the investigated disorders from the balanced LOCT dataset. NW: no white space, HISTEQ: standard histogram equalization, CLAHE: Contrast-Limited Adaptive Histogram Equalization.

A second dataset on which the experiments were conducted is the OCTDL. All images from the dataset were used with the training, validation, and test split proposed by the authors and published in their repository: https://github.com/MikhailKulyabin/OCTDL (accessed on 16 December 2024). The subsets contain 1272, 302, and 490 images from 7 unbalanced classes for the training, validation, and testing, respectively. Examples of images for each class are visualized in Figure S1 of the Supplementary Materials.

3.2. Preprocessing

When analyzing the images from the LOCT dataset, it can be noticed that they contain oblique white spaces at the edges (frequently top or bottom) encompassing the corners. Table 1 lists the number of images within the dataset that contain such OCT image anomalies. As can be noticed, the white spaces are prevalent in 62% of images in total. Their numbers vary from 57% in the CNV class to 67% in the DRUSEN class and from 61% in the training subset to 78% in the test subset. Furthermore, such a feature is present in all 8 validation samples from the NORMAL class.

Table 1.

Number of images in each class of LOCT dataset with white space at the edge.

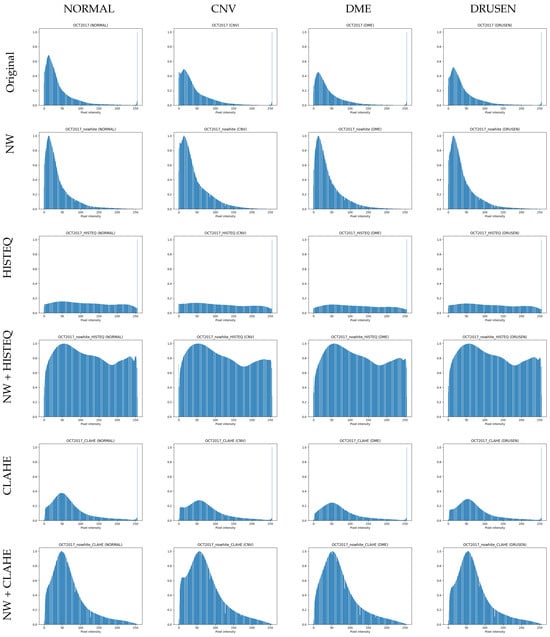

We hypothesize that these areas, added during the acquisition with the Heidelberg Spectralis device, influence image processing and, therefore, model training. They change the histogram of the image, introducing a large number of pixels with the 255 value (see a peak on the right side of histograms in the first row in Figure 2), and may hinder the histogram equalization process, as well as the model’s ability to discern between image classes properly.

Figure 2.

Histograms of OCT B-scans with the investigated disorders from the balanced LOCT dataset. NW: no white space, HISTEQ: standard histogram equalization, CLAHE: Contrast-Limited Adaptive Histogram Equalization.

Here, we investigate the influence of preprocessing, by (1) removing the white spaces from the OCT images and (2) performing the histogram equalization technique, on image classification performance.

3.2.1. Removing White Spaces

To test the influence of the first preprocessing technique, a copy of the dataset was prepared with images cropped to the areas not containing the described above white spaces (see row II in Figure 1). For further reference, this change is designated with NW, for no white spaces. Similarly, the histograms of the modified images (calculated and normalized across all images within each class) are visualized in row II of Figure 2. As can be noticed, these images no longer contain a high number of white pixels with 255 value (the peak on the right side of the histograms from the first row is removed). The size of images after this procedure ranged from 355 to 1536 px in width and from 161 to 512 px in height. For reproducibility purposes, a list of files selected from the LOCT dataset is published together with the programming code used during the described experiments. As the images from the OCTDL dataset do not contain white edges, they were not subjected to this procedure.

3.2.2. Contrast Enhancement

Furthermore, two methods of image contrast enhancement were tested: standard histogram equalization (referred to in this work as HISTEQ) [21] and the Contrast-Limited Adaptive Histogram Equalization (otherwise known as CLAHE) [22]. In this version of adaptive histogram equalization, contrast enhancement is restricted to minimize noise amplification and is applied to a partitioned image (on each block separately). This adjustment could be advantageous for highly noisy OCT data.

The algorithms were implemented using the OpenCV python functions called equalizeHist and createCLAHE [23]. The standard method does not require any parameters and was used as is. The CLAHE algorithm requires two parameters: tileGrid, which defines the number of blocks for image partitioning (set to 8 in our experiment), and the clipLimit parameter representing the maximum contrast value (set to ). This preprocessing added ms and ms to the image processing time for the HISTEQ and CLAHE methods, respectively. The effect of applying these algorithms to the OCT images is illustrated in Figure 1 in rows III for HISTEQ and V for CLAHE. Their respective histograms are visualized in rows III and V in Figure 2.

In the standard histogram equalization technique, the image gets significantly brighter, making noise more visible in the upper and lower parts. If there are cysts in the retina, they appear more defined, but the contrast of retina layers decreases (especially in areas of drusen and neovascularization). The respective histograms (in row III of Figure 2) are almost uniform, with the peak of pixels still present.

Conversely, the CLAHE algorithm enhances the contrast of retina layers and abnormalities like cysts. The noise outside the retina structures is less highlighted compared to the standard method. The calculated histograms show a flatter distribution of pixels (with the bulk of samples in the value lower than 100) and also a peak for value 255.

The histograms for analysis of the OCTDL dataset are presented in Figure S2 of the Supplementary Materials.

3.2.3. White Space Removal and Histogram Equalization

The histogram equalization was also performed for the second version of the LOCT dataset with no white spaces. As was hypothesized, the removal of white spaces influenced histogram equalization. It is especially visible for examples in row IV in Figure 1. The tissue contrast is slightly increased, and biological structure edges are more defined compared to the images in the third row. Furthermore, the brightness dynamic of the cropped images appears to be greater (the retina layers are brighter in the fourth row). The histograms for this preprocessing method are also shown in row IV of Figure 2. The distribution of pixels is more uniform, with a slightly larger number of pixels of intensity around 50 and a lower number of pixels of intensity around 0 and 180.

Application of CLAHE on the NW images gave similar results as for the Original images. Visual inspection in row VI in Figure 1 illustrates comparable tissue contrast. Additionally, the presence of noise does not seem to be affected in the cropped images for either of the histogram equalization methods. The corresponding histograms are presented in row VI of Figure 2.

3.3. Classification Model Architectures

In this study, our goal was to conduct multi-class classification on a single OCT B-scan image assigned to one of the classes: CNV, DME, DRUSEN, or NORMAL (for LOCT). Five network architectures were tested with weights pre-trained on the ImageNet dataset, and their last layer was replaced with a fully connected layer of 4 output classes (instead of the original 1000). The selected methods are VGG16 [24], InceptionV3 [25], Xception [26], ResNet50 [27], and DenseNet121 [28]. The initial weights for all models were frozen, and the training was performed only on the last fully connected layer.

Each of the selected neural network architectures has its own unique characteristics that can affect their performance in processing OCT images, with factors such as depth, computational efficiency, and feature reuse influencing their performance:

- VGG16: Known for its simplicity with a uniform architecture consisting of multiple convolutional layers followed by fully connected layers. It may struggle with computational efficiency due to its depth but can still provide good performance in image recognition tasks.

- InceptionV3: Utilizes a module called “Inception” that allows for multiple filters to be applied at the same time. This architecture is designed to balance performance and computational efficiency.

- Xception: Based on the idea of depth-wise separable convolutions, which can lead to better performance with fewer parameters compared to traditional convolutions. It may offer improved efficiency in processing OCT images.

- ResNet50: Famous for introducing the concept of residual connections, which help address the problem of vanishing gradients in very deep neural networks. This architecture can be beneficial for processing complex features in OCT images.

- DenseNet121: Connects each layer to every other layer in a feed-forward fashion, which promotes feature reuse and gradient flow. This can lead to better performance and efficiency in processing OCT images by enhancing information flow.

3.4. Experiment Setup

The experiments were carried out on a PC with a Windows operating system with an Intel Core i5-6300HQ 2.3 GHz CPU, 8 GB of RAM, and an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3070 GPU with 8 GB of memory. The training was performed for 50 epochs for the LOCT dataset and 100 epochs for the OCTDL with a CrossEntropy loss function. Three optimizers were taken into consideration: Adaptive Moment Estimation (Adam), Root Mean Squared Propagation (RMS), and Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD). As an additional preprocessing step, the images were resized to px. This was necessary to ensure the images match the size of the pre-trained model’s input layer.

Table 2 lists the training parameters for all experiments. These were selected empirically as best-performing on the validation dataset from the set of {8, 16, 32} for batch size and {} for the learning rate. The Keras library implementation was utilized for all methods and models [29]. The classification performance was assessed using the following parameters: accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score. The same training parameters from Table 2 were used to evaluate both datasets. The experiments on the OCTDL dataset utilized only the Adam optimizer. Due to the class imbalance of the OCTDL dataset, a weighting scheme, with values inversely proportional to the number of samples in each class, was employed for weighting the loss function. No data augmentation techniques were used for either of the datasets to limit the influence of additional preprocessing procedures on model training.

Table 2.

Experiment setup parameters for training models on LOCT dataset.

4. Results

4.1. Classification Metrics for LOCT Dataset

In this section, results averaged across classes are presented for each of the tested models. Values in Table 3, Table 4, Table 5, Table 6 and Table 7 contain performance metrics obtained on the test set after applying described preprocessing techniques. The best-observed results for each optimizer are reported in bold.

Table 3.

Averaged classification metrics for LOCT dataset obtained with the VGG16 model.

Table 4.

Averaged classification metrics for LOCT dataset obtained with InceptionV3 model.

Table 5.

Averaged classification metrics for LOCT dataset obtained with the Xception model.

Table 6.

Averaged classification metrics for LOCT dataset obtained with ResNet50 model.

Table 7.

Averaged classification metrics for LOCT dataset obtained with DenseNet121 model.

With the VGG16 model (Table 3), performing the CLAHE operation has a clear beneficial impact, whereas applying standard histogram equalization frequently leads to lower accuracy values than expected. The best results of 96.38% for both accuracy and F1-score were achieved with the RMS optimizer after removing white spaces and performing CLAHE operation, although the Adam optimizer gave very similar values.

The InceptionV3 model (Table 4) gave similarly good results when using the Adam optimizer on NW data after standard histogram equalization (96.38% accuracy and 96.39% F1-score). Other optimizers performed slightly worse, with best values of 95.97% accuracy for RMS and the NW dataset and 95.97% accuracy for SGD with HISTEQ. It should be noted that the CLAHE technique was not beneficial when using this model.

The least-observable influence was found in the case of the Xception model (Table 5). With Adam optimizer, no increase in the accuracy or recall was observed with respect to unprocessed data. The standard histogram equalization gave here a small increase in precision (by 0.07%) and F1-score (by 0.02%). Nevertheless, the best results were obtained when using SGD optimizer with CLAHE on NW data: 96.49% for both accuracy and recall, and 96.50% and 96.48% for precision and F1-score, respectively. Similarly, a combination of NW data and CLAHE resulted in improving classification performance for the RMS optimizer.

The greatest influence of preprocessing was observed for the ResNet50 model (Table 6). Here, with the Adam optimizer, white space removal increased the accuracy of disease classification by 4.13%, resulting in 89.05% as the best value. With RMS and SGD optimizers, an application of CLAHE on NW allowed for obtaining the best F1-score values of 87.42% and 84.56%, respectively. Notably, all of the best results obtained with the ResNet50 model are lower than for other NN models, from 7.44% (with Adam optimizer) to 11.99% (with SGD).

For the three analyzed optimizers with the DenseNet121 model (Table 7), the results obtained on the NW data gave the best F1-scores of 96.17%, 96.59%, and 96.39% for Adam, RMS, and SGD, respectively. However, no clear pattern of impact for the histogram equalization approach can be discerned, as the best accuracy was achieved after CLAHE for Adam optimizer (96.17%), with no equalization for RMS (96.59%), and after applying a standard method for SGD (96.38%).

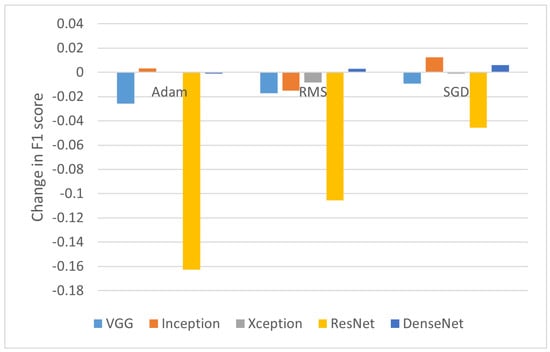

4.2. Analysis of Influence of Histogram Equalization

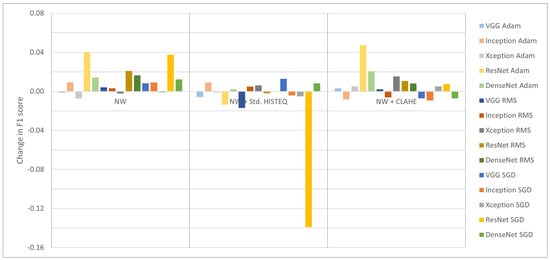

To understand the influence of histogram equalization on OCT images, differences between F1-scores (as a balanced metric) obtained on the original data and images modified with HISTEQ were computed. Figure 3 presents a bar plot with the calculated values.

Figure 3.

Change in F1-score after applying standard histogram equalization.

What can be observed here is a clear negative impact on classification performance for the ResNet50 model. For all optimizers, the F1-score decreased, with the difference ranging from −4.55% for SGD to −16.26% for Adam. A reduction in F1-score is also noticed in all cases of VGG16, where the metric values dropped by 0.92%, 1.72%, and 2.57% for SGD, RMS, and Adam, respectively. The positive values were obtained for the InceptionV3 model with Adam (0.33%) and SGD (1.24%) and for the DenseNet121 model with RMS (0.3%) and SGD (0.6%).

From an average difference of −2.44% and −0.44% with and without taking into account the ResNet50 results, respectively, it can be summarized that applying simply standard histogram equalization on OCT images decreases the accuracy of disease classification.

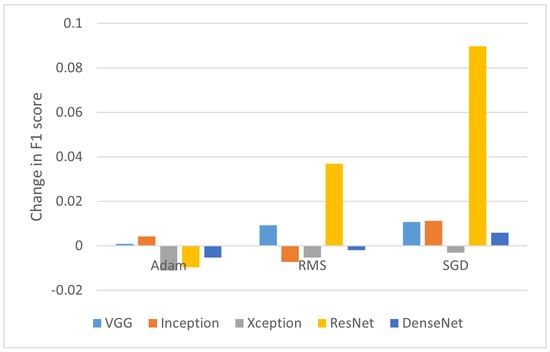

A similar analysis conducted for the utilization of CLAHE on original images is presented in Figure 4. Although the adaptive method enhanced the contrast locally instead of globally (as with the standard histogram equalization), emphasizing characteristics of retina tissue changes, it allowed improving classification only in some cases.

Figure 4.

Change in F1-score after applying CLAHE.

The most dominant change in F1-score was again observed for the ReNet50 model. The CLAHE algorithm seems to positively influence the disease classification process here, as the obtained differences were 3.69% and 8.97% for RMS and SGD, respectively. Overall, with Adam optimizer, the CLAHE does not provide significant gain in the F1-score with an average difference of −0.42% across all models.

Interestingly, a positive difference value was observed in all cases using the VGG16 model (0.09%, 0.93%, and 1.07% for Adam, RMS, and SGD, respectively). Whereas, the Xception model with this method showed a negative change in F1-score across all optimizers (with the difference of −1.11%, −0.52%, and −0.31%, respectively). In conclusion, a beneficial effect can be achieved by applying CLAHE when using the SGD optimizer (with the exception of the Xception model).

4.3. Analysis of Influence of Removing White Spaces

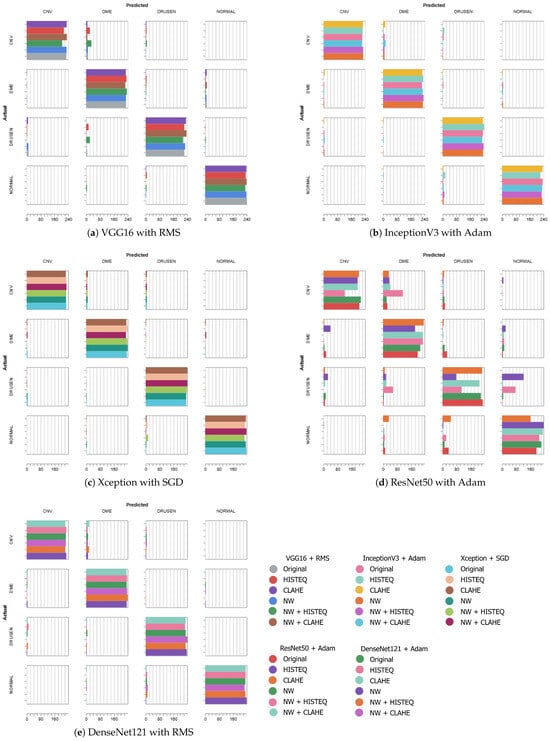

The second analysis was conducted for the impact of removing white spaces from the images. Figure 5 shows differences in F1-score that illustrate the influence of applying only white space removal (left part of Figure 5) and combination with standard (central) and adaptive (right) histogram equalization.

Figure 5.

Change in F1-score after removing white space (with or without additionally using HISTEQ or CLAHE).

For most of the models (regardless of the optimizer used), simple removal of undefined white space at the edge of an OCT image helps in retinal disease classification (left group of the bars in Figure 5). Negative values here are for VGG16 with Adam (−0.11%) and all Xception models (−0.73%, −0.21%, and −0.1% for Adam, RMS, and SGD, respectively). The positive values range from 0.31% for InceptionV3 with RMS up to 4.04% for ResNet50 with Adam. This preprocessing procedure resulted in a gain of 1.1% on average.

A combination of white space removal and HISTEQ did not lead to significant improvements, as visualized in the central part of Figure 5. The single most detrimental effect was observed in the case of the ResNet50 model with the SGD optimizer, where the F1-score decreased by 13.92%. The average change for all other models was −0.04%, which is much less than without performing the histogram equalization procedure (as described above). A positive difference value was achieved with InceptionV3 + Adam (0.91%), DenseNet121 + Adam (0.21%), InceptionV3 + RMS (0.5%), Xception + RMS (0.62%), VGG16 + SGD (1.28%), and DenseNet121 + SGD (0.83%). Notably, the gain obtained by removing white spaces was significantly reduced by HISTEQ.

Application of CLAHE on the NW data gave similar results compared to the adjusted dataset with no contrast enhancement. Conversely, negative change values were obtained for the InceptionV3 model (and not Xception as before), with −0.83%, −0.61%, and −0.92% for Adam, RMS, and SGD optimizers, respectively, as well as for VGG16 + SGD (−0.72%) and DenseNet121 + SGD (−0.71%). The overall average change was 0.58%, indicating an improvement in performance, with positive values ranging from 0.21% for VGG16 + RMS to 4.75% for ResNet50 + Adam.

In summary, with Adam and RMS optimizers, it is better to perform white space removal alone or with an application of CLAHE than to apply only HISTEQ or only CLAHE. With SGD optimizer, better results were obtained either on NW data or after performing CLAHE operation, but not when using both. The variations in the F1-score of <1% indicate that the utilized model architectures are robust to small differences in the input data. Another explanation might be that the model has reached a saturation point in performance for the tested dataset, and further procedures might not have a large impact. Overall, the pattern visible in the results suggests that the discussed preprocessing methods depend on the context in which the data are used and the data quality.

Figure 6 presents the confusion matrices of the best-performing models from each architecture, which are VGG16 + RMS (F1-score of 96.38%), InceptionV3 + Adam (96.39% in F1-score), Xception + SGD (F1: 96.48%), ResNet50 + Adam (F1: 89.06%), and DenseNet121 + RMS (F1: 96.59%). The experiments using the original and NW datasets with described modifications are stacked in the form of horizontal bars to allow for easier comparison between the preprocessing schemes. The diagonal represents the correct predictions, i.e., where the actual label is equal to the predicted label. For each category, in each square, a horizontal bar shows the number of images of the actual label that the model assigned a predicted label. The color indicates the preprocessing method.

Figure 6.

Confusion matrices for models trained on datasets with various preprocessing.

Except for the ResNet50 architecture, the best-obtained F1-scores are similar in value. As can be seen in Figure 6, a majority of the predicted classes can be found on the diagonal (less so for the ResNet50 model—Figure 6d), which indicates a generally good agreement.

With the VGG16 (Figure 6a), there occurred more instances of misclassification of CNV (predicted as DME) and DRUSEN (assigned to DME) when utilizing HISTEQ (red) and NW with HISTEQ (green).

When analyzing plots of the InceptionV3 (Figure 6b) and Xception (Figure 6c) models, a similar distribution of the predictions across the preprocessing methods can be observed. Only a few examples of CNV (assigned to either DME or DRUSEN) and NORMAL samples (improperly classified as DRUSEN) are visible, mostly for HISTEQ or NW + HISTEQ results.

Figure 6d confirms the numerical results obtained for the ResNet model and presented earlier in Table 6. Here, the majority of misclassification occurred for NW + HISTEQ (pink) and HISTEQ (purple) data, incorrectly assigning CNV (to DME), DME (to CNV), and DRUSEN (to DME and NORMAL). Nevertheless, poor performance was also observed for the CLAHE algorithm (orange) with NORMAL samples (predicted as DME or DRUSEN). Interestingly, all models showed lowered accuracy in distinguishing between CNV and DME samples.

The DenseNet121 model (Figure 6e) presents a good classification performance, with a low number of inaccuracies (mostly for CNV predicted as DME and NORMAL predicted as DRUSEN). A handful of misclassification instances can be seen for DRUSEN (assigned to CNV) and CNV (assigned to DRUSEN). No significant difference between the preprocessing methods is noticeable in this confusion matrix.

4.4. Disease Classification with OCTDL Dataset

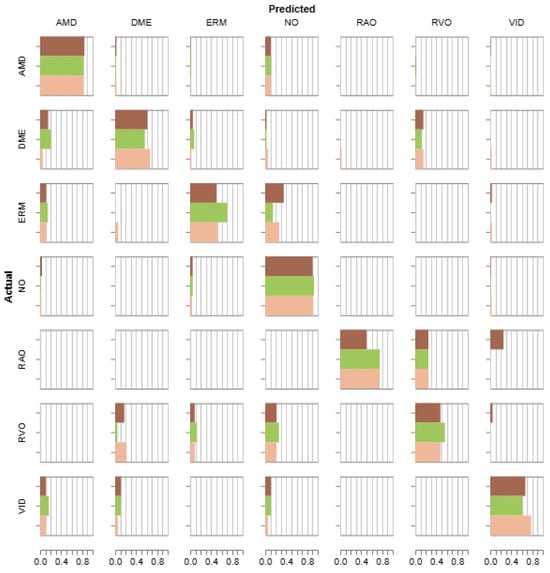

The results of the classification task performed on the OCTDL dataset with VGG16 and Adam optimizer are listed in Table 8. The best results are marked in bold. All metrics indicate a positive influence of performing the HISTEQ operation, with an accuracy of 79.8% and F1-score of 72.38%. However, the CLAHE procedure for Avanti OCT data seems to worsen the model’s ability to distinguish between pathology classes correctly. Here, the lower number of examples for each class is presumably the reason for worse classification performance compared to the LOCT dataset.

Table 8.

Averaged classification metrics for OCTDL dataset obtained with the VGG16 model.

Figure 7 presents the calculated confusion matrix. The values representing the number of predictions for each class illustrated in horizontal bar plots are normalized due to severe class imbalance. A tendency to assign the NORMAL property to images from AMD, ERM, RVO, and VID classes is noticeable. Also, a difficulty in distinguishing the DME, ERM, and RVO samples from other groups was observed. The HISTEQ procedure had a positive influence on detecting the ERM and RVO classes but negatively impacted the classification of DME and VID.

Figure 7.

Confusion matrix for the VGG16 model trained on the OCTDL dataset with various preprocessing (light brown—no preprocessing, green—HISTEQ, dark brown—CLAHE).

The numerical results and confusion matrices for the remaining classification architectures can be found in the Supplementary Materials in Table S1 and Figure S3, respectively.

5. Conclusions

Analysis of histograms of individual classes of the LOCT database showed that due to the specificity of image acquisition, significant fragments of the OCT B-scans are white. The removal of these fragments was proposed by selectively reducing the size of the B-scan. At the same time, after this operation, the histogram equalization process was performed in a standard and adaptive manner using the CLAHE method. The usefulness of these operations was assessed using efficiency metrics for various neural network architectures used in image classification.

The performed experiments show that, in general, the standard histogram equalizing procedure does not improve classification accuracy, leading to a reduction in the F1-score of −2.44% on average. Although uniform contrast distribution could be beneficial for other images, the large number of dark pixels as a background causes this method to give similar intensities to the retina tissue pixels (in effect, lowering its contrast). A resulting blurring of the diseased areas may be the reason for misclassification.

At the same time, the application of CLAHE improves classification performance by 0.84% on average across all models. This gain may be attributed to enhanced tissue features showing changes associated with the specific diseases (e.g., fluid-filled regions and drusen).

The results of the experimental studies indicate that the ResNet50 model is the most sensitive to image brightness distribution. Application of HISTEQ reduced the disease recognition by 16.26% when using the Adam optimizer. After the proposed preprocessing of images with CLAHE, the classification performance improved by up to 8.97%. Notably, for the Xception architecture, only the application of CLAHE on the NW data allowed for an improvement in performance, while other preprocessing techniques had a detrimental effect.

The analysis of classification quality results indicates that the choice of preprocessing improvement method using white space removal and/or CLAHE depends on both the neural network architecture used and the training parameters, including the optimizer. As discussed in the Section 4, the removal of white areas in the input images (the NW version of the dataset) significantly improves the model’s ability to distinguish between healthy and diseased retinas. The average gain here was 1.6% (excluding negative F1-score difference values), with 4.04% for the ResNet50 model. The best results were obtained on a balanced dataset (of 8250 samples in each class) with the DenseNet121 and RMS optimizer (F1-score of 96.59%) utilizing the NW version of the images.

Future studies could focus on combining images obtained with OCT devices from different manufacturers in both the training and testing datasets. This would allow for obtaining a universally useful model for retinal disease diagnosis.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/electronics13244996/s1, Figure S1: Examples of OCT B-scans with the investigated disorders from the balanced OCTDL dataset; Figure S2: Histograms of OCT B-scans with the investigated disorders from the balanced OCTDL dataset; Figure S3: Confusion matrices for models trained on OCTDL dataset with various preprocessing; Table S1: Averaged classification metrics for OCTDL dataset.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.M.; methodology, T.M.; software, A.S.; validation, T.M. and A.S.; formal analysis, T.M. and A.S.; investigation, T.M. and A.S.; resources, A.S.; data curation, A.S.; writing—original draft preparation, T.M. and A.S.; writing—review and editing, T.M. and A.S.; visualization, A.S.; supervision, T.M.; funding acquisition, T.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was prepared within Poznan University of Technology project number 0211/SBAD/0224.

Data Availability Statement

The Python code supporting reported results can be found in the GitHub repository under the link https://github.com/krzyk87/OCTclassification.git (accessed on 16 December 2024) in the electronics2024 branch. The list of files selected from the publicly available LOCT dataset and analyzed during the study is also published with the code.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AMD | Age-related Macular Degeneration |

| CLAHE | Contrast-Limited Adaptive Histogram Equalization |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| CNV | Choroidal NeoVascularization |

| CSR | Central Serous Retinopathy |

| DME | Diabetic Macular Edema |

| DR | Diabetic Retinopathy |

| EM | Epiretinal Membrane |

| HISTEQ | Standard Histogram Equalization |

| JPEG | Joint Photographic Experts Group image format |

| LOCT | Labeled Optical Coherence Tomography |

| MH | Macular Hole |

| NN | Neural Network |

| NW | No white space (images) |

| OCT | Optical Coherence Tomography |

| OCTDL | Optical Coherence Tomography dataset for Deep Learning methods |

| OCTID | OCT Image Database |

| RAO | Retinal Artery Occlusion |

| RVO | Retinal Vein Occlusion |

| VID | Vitreomacular Interface Disease |

References

- Duker, J.S.; Waheed, N.K.; Goldman, D.R. Handbook of Retinal OCT: Optical Coherence Tomography, 2nd ed.; Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, C.J.; Mirza, R.G.; Gill, M.K. Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Med. Clin. N. Am. 2021, 105, 473–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goździewska, E.; Wichrowska, M.; Kocięcki, J. Early Optical Coherence Tomography Biomarkers for Selected Retinal Diseases—A Review. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 2444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akpinar, M.H.; Sengur, A.; Faust, O.; Tong, L.; Molinari, F.; Acharya, U.R. Artificial intelligence in retinal screening using OCT images: A review of the last decade (2013–2023). Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2024, 254, 108253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pachade, S.; Porwal, P.; Thulkar, D.; Kokare, M.; Deshmukh, G.; Sahasrabuddhe, V.; Giancardo, L.; Quellec, G.; Mériaudeau, F. Retinal Fundus Multi-Disease Image Dataset (RFMiD): A Dataset for Multi-Disease Detection Research. Data 2021, 6, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sengar, N.; Joshi, R.C.; Dutta, M.K.; Burget, R. EyeDeep-Net: A multi-class diagnosis of retinal diseases using deep neural network. Neural Comput. Appl. 2023, 35, 10551–10571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulyabin, M.; Zhdanov, A.; Nikiforova, A.; Stepichev, A.; Kuznetsova, A.; Ronkin, M.; Borisov, V.; Bogachev, A.; Korotkich, S.; Constable, P.A.; et al. OCTDL: Optical Coherence Tomography Dataset for Image-Based Deep Learning Methods. Sci. Data 2024, 11, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gholami, P.; Roy, P.; Parthasarathy, M.K.; Lakshminarayanan, V. OCTID: Optical coherence tomography image database. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2020, 81, 106532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kermany, D.S.; Goldbaum, M.; Cai, W.; Valentim, C.C.; Liang, H.; Baxter, S.L.; McKeown, A.; Yang, G.; Wu, X.; Yan, F.; et al. Identifying medical diagnoses and treatable diseases by image-based deep learning. Cell 2018, 172, 1122–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kermany, D.; Zhang, K.; Goldbaum, M. Labeled Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) and Chest X-Ray Images for Classification; Mendeley Data, V2; National Institute of Informatics: Tokyo, Japan, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Chen, M.; Ishikawa, H.; Wollstein, G.; Schuman, J.S.; Rehg, J.M. Automated macular pathology diagnosis in retinal OCT images using multi-scale spatial pyramid and local binary patterns in texture and shape encoding. Med. Image Anal. 2011, 15, 748–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srinivasan, P.; Kim, L.A.; Mettu, P.S.; Cousins, S.W.; Comer, G.M.; Izatt, J.A.; Farsiu, S. Fully automated detection of diabetic macular edema and dry age-related macular degeneration from optical coherence tomography images. Biomed. Opt. Express 2014, 5, 3568–3577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Z.; Wang, J.; Wang, X.; Dong, X.; Li, Y. A Review of Segmentation and Classification for Retinal Optical Coherence Tomography Images. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 2nd International Conference on Pattern Recognition and Machine Learning (PRML), Chengdu, China, 16–18 July 2021; pp. 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, L.; Wang, C.; Li, S.; Rabbani, H.; Chen, X.; Liu, Z. Attention to Lesion: Lesion-Aware Convolutional Neural Network for Retinal Optical Coherence Tomography Image Classification. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2019, 38, 1959–1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ara, R.K.; Matiolański, A.; Dziech, A.; Baran, R.; Domin, P.; Wieczorkiewicz, A. Fast and Efficient Method for Optical Coherence Tomography Images Classification Using Deep Learning Approach. Sensors 2022, 22, 4675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alwakid, G.N.; Humayun, M.; Gouda, W. A Comparative Investigation of Transfer Learning Frameworks Using OCT Pictures for Retinal Disorder Identification. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 138510–138518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opoku, M.; Weyori, B.A.; Adekoya, A.F.; Adu, K. CLAHE-CapsNet: Efficient retina optical coherence tomography classification using capsule networks with contrast limited adaptive histogram equalization. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0288663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kociołek, M.; Strzelecki, M.; Obuchowicz, R. Does image normalization and intensity resolution impact texture classification? Comput. Med. Imaging Graph. 2020, 81, 101716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Retinal OCT Images (Optical Coherence Tomography). Available online: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/paultimothymooney/kermany2018?resource=download (accessed on 16 December 2024).

- Marciniak, T.; Stankiewicz, A. Automatic diagnosis of selected retinal diseases based on OCT B-scan. Klin. Ocz./Acta Ophthalmol. Pol. 2024, 126, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McReynolds, T.; Blythe, D. CHAPTER 12—Image Processing Techniques. In Advanced Graphics Programming Using OpenGL; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2005; pp. 211–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizer, S.M.; Amburn, E.P.; Austin, J.D.; Cromartie, R.; Geselowitz, A.; Greer, T.; ter Haar Romeny, B.; Zimmerman, J.B.; Zuiderveld, K. Adaptive histogram equalization and its variations. Comput. Vis. Graph. Image Process. 1987, 39, 355–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Open Source Computer Vision Library. Histogram Equalization Tutorial. Available online: https://docs.opencv.org/4.x/d5/daf/tutorial_py_histogram_equalization.html (accessed on 18 July 2024).

- Simonyan, K.; Zisserman, A. Very Deep Convolutional Networks for Large-Scale Image Recognition. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1409.1556. [Google Scholar]

- Szegedy, C.; Vanhoucke, V.; Ioffe, S.; Shlens, J.; Wojna, Z. Rethinking the Inception Architecture for Computer Vision. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 2818–2826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chollet, F. Xception: Deep Learning with Depthwise Separable Convolutions. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. In Proceedings of the Compputer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Boston, MA, USA, 7–12 June 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, G.; Liu, Z.; van der Maaten, L.; Weinberger, K.Q. Densely Connected Convolutional Networks. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Keras. Available online: https://keras.io (accessed on 16 December 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).