Abstract

Task allocation is an important problem in multi-robot systems, particularly in dynamic and unpredictable environments such as offshore oil platforms, large-scale factories, or disaster response scenarios, where high change rates, uncertain state transitions, and varying task demands challenge the predictability and stability of robot operations. Traditional static task allocation strategies often struggle to meet the efficiency and responsiveness demands of these complex settings, while optimization heuristics, though improving planning time, exhibit limited scalability. To address these limitations, this paper proposes a task allocation method based on the Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS) algorithm, which leverages the anytime property of MCTS to achieve a balance between fast response and continuous optimization. Firstly, the centralized adaptive MCTS algorithm generates preliminary solutions and monitors the state of the robots in minimal time. It utilizes dynamic Upper Confidence Bounds for Trees (UCT) values to accommodate varying task dimensions, outperforming the heuristic Multi-Robot Goal Assignment (MRGA) method in both planning time and overall task completion time. Furthermore, the parallelized distributed MCTS algorithm reduces algorithmic complexity and enhances computational efficiency through importance sampling and parallel processing. Experimental results demonstrate that the proposed method significantly reduces computation time while maintaining task allocation performance, decreasing the variance of planning results and improving algorithmic stability. Our approach enables more flexible and efficient task allocation in dynamically evolving and complex environments, providing robust support for the deployment of multi-robot systems.

1. Introduction

Offshore oil and gas facilities are typically located in remote and isolated areas, and the unique nature of these locations presents significant challenges for human operators. Introducing fully autonomous robot systems is an effective way to address these issues [1]. Robots are able to perform tasks in these harsh environments, reducing reliance on human workers, lowering operating costs, and improving safety. In recent years, the potential of autonomous robots for offshore operations has been preliminarily explored and applied [2,3].

The preliminary research work [4,5] has set some benchmarks to demonstrate the effectiveness of autonomous vehicles participating in intervention tasks in marine environments. These studies typically focus on simple, single-task autonomous execution, such as inspection and monitoring. However, the operation and maintenance of offshore oil facilities require a higher level of autonomy, involving a series of complex tasks such as long-term facility inspections, systematic maintenance work, and responding to emergencies.

The traditional solution is to equip a single robot with all the hardware and software components required to perform complex tasks [6], and a major issue with this approach is its high cost. In order to adapt to various possible tasks, the design of these robots often needs to make trade-offs, resulting in insufficient performance on certain specific tasks. In addition, some specific tasks may only be applicable to certain types of robots. For example, vertical inspection of pipelines may only be performed by specially designed aircraft. Therefore, using multiple platforms optimized for specific tasks, which collaborate to achieve common goals [6,7], has become a more ideal solution. This heterogeneous multi-agent approach not only provides stronger robustness for the entire system but also expands the scope and flexibility of tasks. For example, ground robots can be responsible for inspecting and maintaining ground structures, while aerial robots can perform high-altitude operations or remote monitoring. This multi-robot collaboration method is theoretically feasible but still faces some challenges in practical applications.

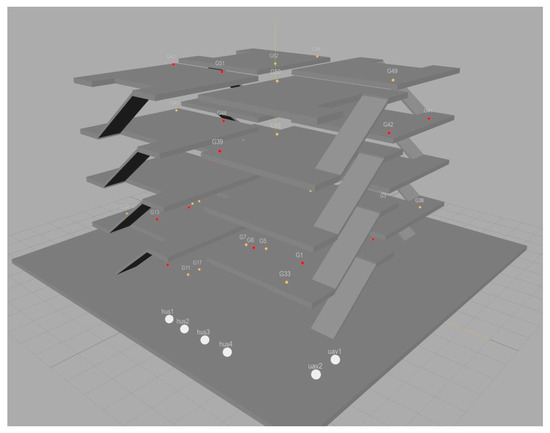

Current multi-agent planning schemes often struggle to generate optimal task allocation plans [8], and low planning quality and computational efficiency are common issues in current multi-agent planning schemes. To address these issues, this study designed a robot group consisting of several ground and aerial robots equipped with different sensory systems that must perform regular supervision and control tasks in the oil drilling environment, which requires vehicles to move between different buildings and floors. Figure 1 shows an oil drilling scene supervised by a robot team. In this situation, task execution must consider the availability of robots to achieve goals in different areas of the oil drilling platform, the capabilities of individual robots, and the distance of task target points.

Figure 1.

Simulation of oil drilling rig scene with robot operation.

Generally speaking, these methods address limited task complexity and diversity, making it impossible to evaluate the performance of planners in highly restricted domains. Recently, the newer heuristic task allocation strategy MRGA [9] has proposed a more effective computational task time allocation plan. This method assigns tasks based on robot functionality, redundant sensor systems, spatial distribution of targets, and task execution time, avoiding the need to calculate a large number of possible tasks. However, the excessive neglect of real-time task dynamics to improve computational speed has, to some extent, affected the scalability of tasks.

As a powerful decision algorithm, MCTS has demonstrated outstanding performance in multiple fields, especially in gaming and optimization problems. MCTS can efficiently find approximate optimal solutions by simulating and evaluating a large number of possible paths. However, despite the significant progress brought by MCTS, its complexity and computational cost remain major challenges, especially in high-dimensional and dynamic environments. To this end, researchers are constantly exploring ways to improve and optimize MCTS in order to enhance its adaptability and computational efficiency, which thus play a greater role in a wider range of application scenarios.

This paper conducts research on the control technology of offshore oil drilling robots based on multi-agent coordination using MCTS. Through abstract modeling of actual working processes, distributed optimization technology will be used to improve algorithm efficiency. The characteristics of the MCTS algorithm will be utilized to achieve fast start-up and continuous optimization, which, to some extent, compensate for the poor timeliness and weak scalability of previous methods. This has important theoretical significance and application value for solving the task allocation technology of offshore oil extraction platform robots.

The contributions of this paper are three-fold:

- We utilize the anytime feature of MCTS and introduce a fast response adaptation mechanism in the centralized MCTS algorithm, which can generate preliminary solutions in a very short time and monitor the robot’s status in real time. Before the robot needs further action instructions, transmit the current optimal solution to continuously optimize the task allocation results. Meanwhile, to address the issue of fixed UCT coefficients failing in different task dimensions, this paper introduces dynamic UCT values to enhance the algorithm’s adaptability to any task dimension;

- In large-scale task environments, due to the exponential growth of action options in the initial state, the variance of the planning results of the MCTS method significantly increases. To address this issue, we propose a strategy based on Distributed Monte Carlo Tree Search (Dec-MCTS). By effectively reducing algorithm complexity through importance sampling and combining parallel processing to optimize the iterative process, the computational efficiency in large-scale task scenarios has been greatly improved, and the optimal preliminary results have been generated in the shortest possible time.

In the rest of this paper, we review related work in Section 2, introduce the multi-robot task allocation model, and formulate the problem in Section 3. We propose an MCTS-based multi-robot task allocation method in Section 4. Finally, we evaluate our solution in Section 5 and conclude in Section 6.

2. Related Work

This work is related to several lines of research in planning, with a focus on the task allocation problem in multi-robot systems. The approaches can be broadly categorized into heuristic MRGA methods and Monte Carlo Tree Search techniques, both of which are introduced in detail in the following sections.

2.1. Task Allocation Problem in Multi-Robot Systems

In complex robot task planning environments, task allocation for multi-robot systems has always been a research hotspot. According to the strategies and application scenarios of task allocation, research in this field can be divided into several levels, including single-task allocation, multi-task collaborative allocation, and heterogeneous system collaboration.

The research on single-task allocation mainly focuses on effectively assigning a specific task to the most suitable robot. Early research [10,11] mainly focused on optimizing task allocation based on task urgency and robot availability, which often proved effective in handling simple or predefined tasks. However, these methods perform poorly in dealing with dynamically changing environments or complex task requirements.

With the increasing complexity of task requirements, how to achieve effective collaborative work between robots in a multitasking environment has become a research focus. Some studies [12,13] have attempted rule-based algorithms to balance the workload of robots and execution efficiency in multitasking environments. These methods typically require detailed prior knowledge and complex rule settings, making it difficult for them to adapt to rapid environmental changes and unforeseen task requirements.

In more complex application scenarios, such as offshore oil platforms, different types of robots (such as ground and air) need to collaborate to complete tasks. Research [14] suggests that effective heterogeneous robot collaboration can significantly improve the efficiency and quality of task execution. However, achieving efficient task allocation and collaboration in heterogeneous systems, especially in dynamic and unknown environments, remains a major challenge.

2.2. Heuristic Multi-Robot Goal Assignment Method

Heuristic methods play an important role in solving complex optimization problems, especially in scenarios where effective solutions need to be obtained quickly [15]. This type of method simplifies the decision-making process by applying empirical rules or “heuristics” to find an approximate solution to the problem within an acceptable time. Compared to complete algorithms, heuristic methods may not guarantee finding the optimal solution, but they can provide satisfactory solutions at lower computational costs when dealing with large-scale or particularly complex problems. Therefore, in practical applications, especially in situations where resources are limited or computing time is restricted, heuristic methods are widely adopted.

MRGA is an efficient heuristic multi-robot task assignment strategy that optimizes task allocation based on two core cost functions. These two cost functions are as follows: (1) the functional cost of the robot, used to determine which tasks the robot can perform; and (2) the linear combination of task completion time, distance between task points (POIs), and redundancy of the perception system. This method divides the task allocation process into two main parts: capability analysis and region partitioning.

In the capability analysis stage, the algorithm first determines the target set of tasks that each robot can perform. Assuming there is a set of robots R = {, , …, }, and a set of objectives G = {, , …, }. The achievement of each goal requires a certain set of abilities GC = {, , …, }, and the set of abilities possessed by each robot is represented as RC = {, , …, }. The goal of this stage is to identify robots with the necessary capabilities to achieve each task objective. The algorithm will add the task to the solvable target list Rrn-cap of the robot when it finds a robot with the required capabilities.

In the region partitioning stage, the MRGA algorithm uses the k-means clustering algorithm [16] to partition the task objectives into regions with a number equal to the number of robots. This step aims to calculate the number of targets that each robot can execute in its respective area. By analyzing the ability of robots in each region to complete tasks, this method can determine the optimal robot options for working in each region. Finally, by selecting the robot configuration that can complete the maximum number of tasks for preliminary task scheduling and then quickly allocating tasks based on each robot’s previous tasks using a short-term greedy algorithm, efficient task allocation was achieved in a very short period of time.

2.3. Monte Carlo Tree Search

MCTS has caused widespread influence in the field of artificial intelligence by performing random sampling in the decision space and constructing a search tree based on the sampling results to identify the optimal strategy. Especially in problems that can be expressed using sequential decision trees, such as games and planning fields, this algorithm has demonstrated wide applicability. MCTS was initially mainly applied to computer Go [17]. Although early attempts, such as Bouzy’s use of Monte Carlo methods to calculate evaluation functions and apply them to Go search, did not make significant progress, subsequent developments such as Crazy Stone [18] and MoGo based on UCT [19] marked a breakthrough for MCTS in this field, providing new tools for solving complex search problems in Go. Recent research in MCTS highlights the importance of reward systems, moving beyond final outcomes (e.g., win/loss) to include intermediary rewards, such as state-dependent features like board control or task progress [20]. These advancements improve adaptability in complex environments and have been applied in robotics, multi-agent systems, and resource allocation tasks to enhance decision-making.

The development of the MCTS algorithm has rapidly expanded to multiple fields, such as gaming and planning [21,22], especially in the applications of Markov Decision Process (MDP) and reinforcement learning, which are receiving increasing attention. For example, the flat UCB method proposed by Coquelin and Munos demonstrates improved adaptability [22]; Van den Broeck et al. improved node selection through expected return distribution [23,24]. In environments with high real-time requirements, such as Pac-Man games, MCTS also performs well [25]. In addition, MCTS has also been widely applied in the field of planning, such as Walsh et al. applying the UCT method to large-scale state space planning problems [26], Pellier et al. proposing the MHSP planning algorithm combining UCT and heuristic search [27], and introducing Bayesian frameworks to improve the accuracy of results in finite simulations [28,29]. As an efficient algorithm, it integrates the strategy of random simulation in the search process of decision trees, which is particularly suitable for making decisions in problems with incomplete information or huge search space [30].

3. Model and Problem Formulation

The task allocation problem of heterogeneous multi-agent systems at sea focuses on researching how to effectively assign multiple tasks to heterogeneous robot clusters deployed on offshore oil platforms based on specific capability requirements, including perception and motion. The core of this issue is to ensure that the task allocation scheme can fully utilize the unique abilities of each robot, thereby achieving efficient completion of the overall task. To achieve this goal, the task allocation mechanism not only needs to consider the time required for robots to complete different types of tasks but also the distance between task locations and corresponding time costs in order to optimize the operational efficiency of the entire system. This task allocation method places special emphasis on minimizing the cost function, which is mainly based on the time cost of different robots completing different tasks and the distance time cost between task locations.

In the real environment of offshore platforms, machine maintenance requires a large number of sensors and actuators. This article considers six tasks that require different abilities: temperature inspection, pressure inspection, observation, photography, valve inspection, and valve manipulation. Observation tasks involve exploring specific task points and can be performed by unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) or Husky ground robots. The valve inspection task requires the ground robot to recognize the status of the valve (open/closed), which requires the robot to be in a specific operating position. The image acquisition task involves using drones to capture structural images from different perspectives. The tasks of pressure and temperature checks are associated with collecting sensor data through ground robots. The task of manipulating valves involves the ground robot changing the opening/closing status of the valves. The basic actions in the process include data communication, navigation, and charging, which support the robot’s mobility and long-term autonomy. The task objectives are closely related to the tasks that the robot system can implement. The task planner is responsible for generating a series of actions to achieve a given set of tasks.

Table 1 shows the list of domain functions possessed by each robot and the estimated time required to perform operations related to that function. The duration of basic function actions depends on the distance d between targets, energy e, and charging rate chr. This article assumes that all actions are deterministic and have complete platform information. The planner generates a plan for assigning targets to the robot queue based on domain constraints, and robots acting on the platform can perform actions simultaneously.

Table 1.

Robot capabilities and expected task duration.

The offshore oil platform consists of the platform body and four relatively independent floors. On this platform, maintenance tasks are performed by four Husky ground robots and two UAV drones. The operations proposed in this article include various actions performed by drones and robots, which involve autonomous navigation, data communication, charging, observation, image capture, and valve detection. All operations are collision-free and planned using semantic roadmaps to ensure their kinematic performance. We analyze in detail the requirements of different tasks for robot capabilities and establish a set of robot capabilities tailored to different task needs before task allocation to optimize resource allocation and utilization.

In this study, we use MDP to model and analyze complex task allocation problems. Specifically, we define a state that includes the following elements: the robot set , the time consumed by each robot’s assigned task set , and the task set that has not yet been assigned to the robot. In addition, represents all the ability groups contained in each robot in the robot set, while is the target ability group, representing the robot’s ability required to complete the corresponding task. The three-dimensional position of the task is represented by the coordinate set . Under this framework, each robot may possess multiple abilities, while each task typically only requires one specific ability. Considering that we know the distance between any two task points on the map, by referring to Table 1, we can calculate the time it takes for the robot to complete any task. This time includes the cost of the robot’s journey from its last task location to a new task location, as well as the operational time required to complete the new task.

In each round of MDP decision-making, action in state refers to the collective action of all robots in that round. When state takes action , all robots will update on the basis of their original execution time, increasing the sum of the travel cost and operation time from the last task execution location to the newly arranged task location. After the status update, mark the selected tasks as completed from the task set to export the new state . It should be pointed out that the possible number of actions in different states varies depending on the size of the task set and the robot. As the scale of tasks and robots increases, the number of possible actions increases exponentially. This growth reflects the complexity and difficulty of solving problems, especially in situations involving multi-agent systems and highly dynamic environments, where the design and optimization of task allocation strategies are particularly critical.

4. Task Allocation Algorithm Based on Monte Carlo Tree Search

In this section, we propose a task allocation algorithm based on Monte Carlo Tree Search. Specifically, we propose a centralized adaptive Monte Carlo Tree Search for small-scale tasks and a decentralized adaptive Monte Carlo Tree Search for large-scale tasks.

4.1. Task Allocation Based on Centralized Adaptive Monte Carlo Tree Search

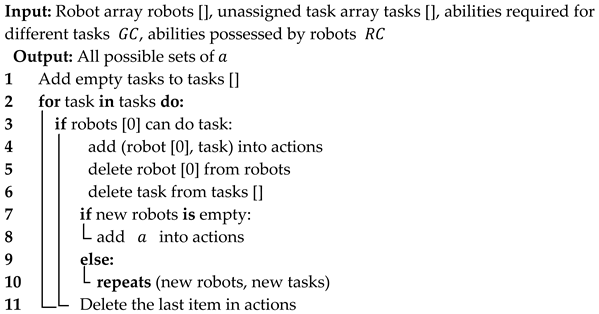

Based on the different abilities possessed by different robots and the different abilities required for different task objectives, we need to design a capability analysis algorithm on the basis of MDP to traverse the set of all under different state .

In the multi-robot capability analysis algorithm of Algorithm 1, the first line of the algorithm inserts a special empty task item into the queue of unallocated tasks. The design intention of this step is to address certain situations, such as when a robot is unable to perform any other tasks in the current context, or when there is a more optimized solution, it can choose the option of wheel clearance. Next, in the second to third lines of the algorithm, this article traverses the robot queue, starting from the first robot, to find a task within its capability range. This process will continue until a suitable task is found or the aforementioned empty task is assigned. Once the appropriate task is identified, as shown in line 4, it is temporarily stored in an array named ‘actions’.

| Algorithm 1: Multi-robot Capability Analysis |

|

Subsequently, the algorithm will create a new robot and task queue while removing the robots and tasks that have already been assigned from it in preparation for the next round of task allocation. As shown in line 7, when all robots have been assigned at least one task, the task allocation result of the current round will be added to set a. Subsequently, following the instructions on line 11, this article retrieves the actions that were recently added to the actions array and proceeds to the next iteration. If there are still robots that have not been assigned tasks, this article will use the updated robots and task queue to restart the entire allocation process.

Algorithm 1 provides an efficient method to ensure that each agent is assigned tasks reasonably according to its capabilities and the requirements of the current situation. By introducing empty task items, the algorithm enhances its flexibility and robustness, allowing agents to effectively take turns when there are no suitable tasks to allocate or better solutions available, avoiding performing tasks that are not suitable or inefficient. Furthermore, the algorithm ensures the continuity of the allocation process and the dynamic response capability of the system by continuously updating the robot and task queues. This method allows the algorithm to re-evaluate the task and robot status during each iteration, adapting to possible environmental changes or new task requirements, thereby optimizing the overall task allocation strategy.

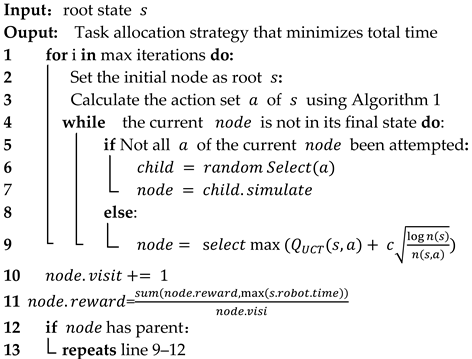

After successfully initializing the state (line 2), Algorithm 2 then uses Algorithm 1 to determine the possible actions a that can be taken in that state (line 3). In the generated tree structure, if there are unassigned tasks in the current state and there are still actions in the action set a that have not been explored, the algorithm will randomly select an untested action from among them and execute it to transition to a new state . At this point, the algorithm will simulate the allocation of remaining tasks through a random task allocation process (simulation) and calculate the corresponding reward based on the final scheduled time (lines 5–7). If all possible actions in action set a have been explored, the algorithm will select those nodes with the highest historical reward values (line 9). This process will continue until all tasks have been assigned, at which point the system reaches a final state . Once the final state is reached, the algorithm starts the backpropagation process. In lines 10 to 13 of the algorithm, the number of visits to the final state is incremented, and the reward value is updated. The reward value is calculated by dividing the sum of all rewards on the path to the final state by the number of visits to obtain the average reward. The same update process will also be applied to all ancestor nodes of the final state, ensuring that the information in the search tree is fully updated. This completes a complete iteration process, setting initial conditions for the next iteration and continuously optimizing the task allocation strategy.

| Algorithm 2: Use MCTS for multi-robot task allocation |

|

In the MCTS algorithm, the traditional selection strategy often relies on the weighted mean of rewards for all possible actions in state . This approach performs well in scenarios like board games, where the outcome is relatively fixed—typically a binary result of winning or losing. In such cases, rewards are often represented as a final game result (e.g., 0 or 1), directly reflecting the winning probability. This concise reward mechanism effectively evaluates the potential value of actions and guides strategy selection. However, even in board games, intermediary rewards—such as features of the game state, like the number of opponent pieces on the board—can also play a crucial role in MCTS node evaluation, enhancing decision-making beyond the final outcome.

In multi-agent task allocation scenarios involving complex decisions and diverse factors, relying solely on traditional reward evaluation methods becomes insufficient. These methods may fail to capture key differences in task completion times, which often depend heavily on each robot’s initial state, target location, and the specific abilities required. To address this limitation, this study proposes a new reward calculation method that moves beyond simple weighted averages of all solutions, instead prioritizing specific choices likely to lead to optimal outcomes, enabling more accurate and adaptive task allocation in complex environments. Although determining an optimal solution is an NP-hard problem that involves extensive computational resources and time, we should not ignore the potential optimal potential just because some specific states may lead to suboptimal results. Instead, we should identify and prioritize those paths that have the potential to guide the system state to or near the optimal solution through a more refined reward system, as shown in Formula (1).

Using this strategy, we can more intensively use resources to pursue and achieve optimal solutions rather than considering all possible solutions equally, thereby more effectively guiding the development of algorithms toward the most advantageous state and improving the efficiency of solving problems.

In addition, using a reward system based on the best possible solution can also bring other benefits, including improving the transparency and predictability of the decision-making process and reducing the possibility of overlooking extreme but valuable strategies due to the pursuit of average. In practical operations, this means that the algorithm can converge to high-quality solutions faster while reducing ineffective exploration on the path to the optimal solution.

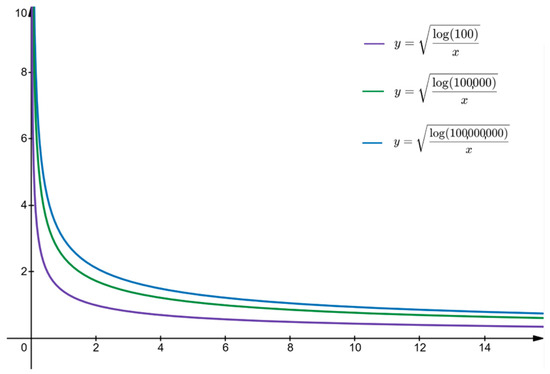

The exploration term in the UCT formula is designed to balance the relationship between exploration and exploitation, where c is the exploration coefficient, represents the total number of visits in state , and represents the number of visits in state when action is taken. This formula adjusts the exploration desire to make a trade-off between new or less explored actions and actions with higher known rewards.

Based on the analysis of Figure 2, it can be found that when the proportion of the number of visits for a specific action to the total number of visits is too high, the value of the exploration item will significantly decrease, which reduces the algorithm’s willingness to explore actions that have not been fully explored. When the minimum number of visits to action is 1, the exploration coefficient value will be a positive number greater than 0.5 and will increase logarithmically as the total number of visits increases. This leads to a potential problem: for actions with high reward values, even if their reward values are only slightly higher than other actions, the algorithm may not explore other possible actions for a long time, thus falling into local optima. For example, in the case of coefficient c = 1, for action with a reward value of 100 if the reward value of another action is 102, it will take at least 1000 visits to re-explore , which is clearly not the optimal choice in terms of decision-making.

Figure 2.

The value of for action under different total access times.

Given the unique challenges of multi-agent task allocation, including the diversity in the total number of tasks and robots, as well as the dynamic nature of task reward values, this paper introduces a new dynamic UCT formula (3) to better accommodate this complexity. In this study, we develop an adaptive D-UBMCTS algorithm by introducing the dynamic UCT formula into traditional MCTS. The key to this algorithm is to dynamically adjust the balance between exploration and exploitation. The specific method is to adjust the exploration parameter c, which measures the proportion of the optimal reward value (max (Reward)) in each state to the total reward. The significant advantage of this strategy is that the algorithm can automatically adjust its behavior to maximize long-term gains regardless of the magnitude of the reward.

By calculating the percentage impact of reward values in real time, the D-UBMCTS algorithm can effectively adapt to task combinations of different sizes and complexities. This flexibility allows the algorithm to automatically find the optimal exploration and exploitation ratio without manually adjusting parameters when facing different task requirements, thus maintaining efficient decision-making capabilities in a changing environment. This not only optimizes the performance of the algorithm but also greatly enhances its adaptability, enabling it to achieve more accurate and efficient task allocation in a wide range of application scenarios. Therefore, the adaptive D-UBMCTS algorithm is not only theoretically innovative but also has great potential for practical application, especially in fields that require the handling of large-scale, highly complex decision-making problems.

4.2. Task Allocation Based on Decentralized Adaptive Monte Carlo Tree Search

When faced with larger task allocation problems, centralized algorithms may produce unstable results in a short period of time due to their inherent randomness. As the task size continues to increase, the variance of the results will become larger, and the allocation of preliminary solutions will have a huge impact on the total time result of the final solution.

4.2.1. Distributed Algorithm Implementation

Firstly, this article defines the action sequence of agent as , where represents the action of agent at time . For agent , all possible action sequences form a set , i.e., . Furthermore, this article defines as a set of action sequences jointly selected by multiple agents, i.e., , where is the total number of agents. Therefore, the set of action sequences for all agents except agent can be represented as .

We define the probability of agent taking a certain action sequence as . Furthermore, this article represents the probability distribution of agent for all possible action sequences as a binary This definition includes two important levels:

Domain of intent: This represents all feasible sequences of actions that the agent may take. This domain defines the scope of the agent’s behavior, that is, which action sequences it can choose to achieve its goals.

Distribution of intent: This represents the agent’s preference for different action sequences. That is to say, this distribution indicates which action sequences the agent tends to take and reflects this preference in the form of probability.

The same logic applies to other agents as well. Therefore, for agent , the set of intentions of all other agents except for itself . This collection provides agent with important information about the possible actions of other participants.

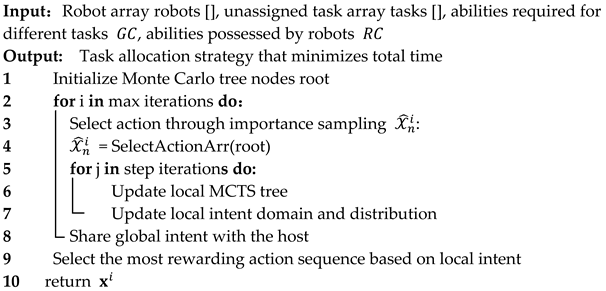

As shown in Algorithm 3, the optimization objectives of the Dec-MCTS algorithm are twofold. One is to optimize the action sequence set selected through importance sampling in this paper, which is the domain of the action. The other is to iteratively optimize and update the selection probability of the sequence set, which is the distribution of the action. It can be divided into three steps: (1) expand the local Monte Carlo search tree; (2) update the action sequence set and probability distribution through importance sampling; and (3) share and update global intent, as explained in detail below.

| Algorithm 3: Multi-robot task allocation based on Distributed Monte Carlo Tree Search (Dec-MCTS) |

|

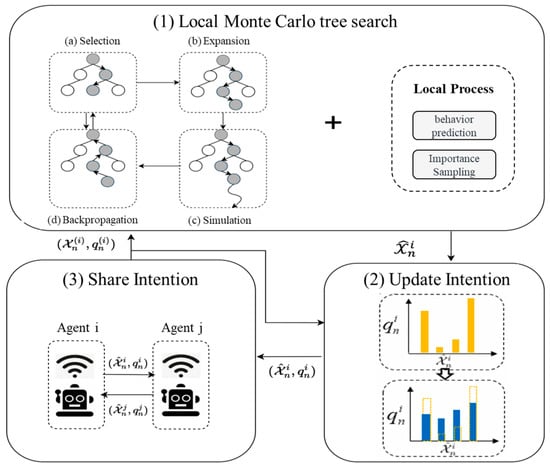

As shown in Figure 3 first, each agent initializes the root node of the Monte Carlo search tree based on the initial global task information, the specific capabilities required for the task, the set of capabilities it possesses, and the scarcity of each capability. This node grows rapidly through an iterative process, providing all the information required for initialization to a single agent (see line 1 of the algorithm). Then, each intelligent agent begins to execute the main process of the decentralized algorithm, which includes continuously looping steps.

Figure 3.

The process of each round of a single agent in the Dec-MCTS algorithm.

Due to the increase in the number of tasks, the size of the set that can be composed of different action sequences grows exponentially. Therefore, this article will not sample and update the probability distribution of all updated action sequences. For a certain intelligent agent, this article only needs to select a part of the more feasible action sequence . This means that although this article abandons considering the distribution of all feasible scenarios, it reduces the originally exponential time complexity to a set constant level (for example, this article only considers the first four most feasible strategies). This process is referred to as importance sampling in the algorithm presented in this article (see line 3 of the algorithm), where the most likely sequence of actions will change as the shared information is updated. Once a new important action sequence is discovered in a certain iteration, this paper uses uniform distribution to initialize the new intent binary .

After each new intent distribution appears, this article will update based on a new round of agent negotiation (see lines 5 to 8 of the algorithm), where the agent first updates the existing Monte Carlo tree according to a specified number of iterations and returns an updated Monte Carlo tree (see line 6 of the algorithm). During the update process, two points should be noted: firstly, the intention set of all other agents except for the agent itself should be considered ; secondly, in the process of sharing, it is necessary to distribute the predicted additional budget among various agents; that is, each agent independently predicts its own path and synchronously shares it. Then, the intelligent agent shares its own intentions while receiving the latest teammate intentions .

Finally, after all rounds of negotiation, each individual agent will receive an action sequence and distribution probability that has been negotiated with all other agents. The action sequence with the highest probability is the final action decision result (line 10).

4.2.2. Importance Sampling

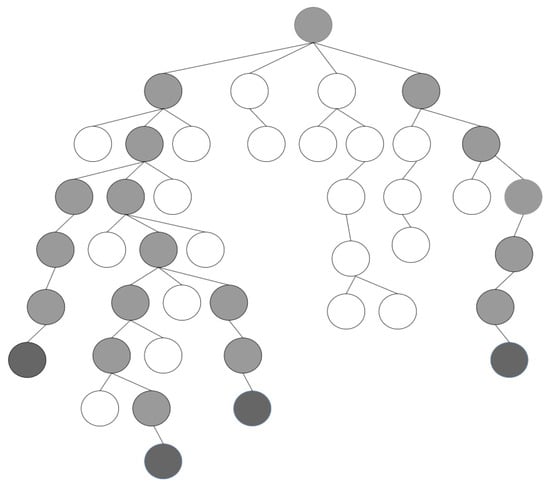

As mentioned earlier, it is impractical to consider all feasible action sequences of agent in each round of decentralized multi-agent negotiation, as the size of the intent domain increases exponentially with time steps. So, this article adopts the method of importance sampling, only considering a part of in each round, that is, , which is essentially a compromise sparse representation of the current search tree. Further explanation of importance sampling will be provided in conjunction with Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Process of root parallelization Monte Carlo tree.

After running the Dec-MCTS algorithm for several rounds, an unbalanced and structurally complex search tree will be generated, as shown in Figure 5. In this study, only four potential action sequences were considered in each round of negotiation, so the size of the intent domain was set to y. This study first traverses the tree using a depth-first search method and then identifies all leaf nodes. Each leaf node contains the cumulative average reward evaluation value of its corresponding branch (action sequence). By comparing the average reward values of these leaf nodes, select the top y leaf nodes with the highest evaluation values (as shown in the dark gray nodes in the figure). Next, trace back from these selected nodes toward the root of the tree to identify the action sequence containing these leaf nodes (as shown by the light gray nodes in the figure).

Figure 5.

Schematic diagram of sparse representation of Monte Carlo search tree obtained through importance sampling.

In order to maintain the continuity of the negotiation process, it is necessary to extend these y action sequences to the Terminal State. Although the conventional approach is to expand the action sequence through random sampling, this method is less efficient. Therefore, this study adopted a method based on greedy heuristic factors to extend the action sequence, and the specific implementation details will be elaborated in the subsequent intention prediction section.

In the process of algorithm implementation, in order to save computation time, this study adopted the strategy of space for time. In the simulation phase of MCTS, combined with greedy heuristic intention prediction, the predicted action sequence is stored in the tree nodes so that it can be directly obtained when needed without recalculating.

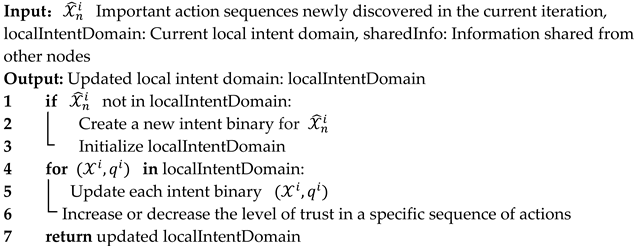

Algorithm 4 provides a detailed description of the process of each importance sampling. In this process, for each newly discovered action sequence located in the top y, first check whether the action sequence already exists in the current local intent domain. If is not recorded in the local intent field, the algorithm will create a new intent binary for it. This newly created intent binary will be initialized to a uniform distribution to ensure that all possible action sequences have an equal probability of being explored in the initial stage (lines 1–3). Subsequently, during the sampling process, the algorithm will utilize the latest information shared from other nodes to recalculate all data within the local intent domain. This step ensures that the local intent domain can reflect the latest global information and changes, thereby adjusting and optimizing the probability distribution and priority of each action sequence (lines 4–6). After recalculating and updating the data, the algorithm will output the updated local intent domain. This output not only includes the newly added action sequence and its related data but also the information of the existing action sequence updated based on global information (line 7). In this way, the importance sampling algorithm ensures that the local intent domain remains up-to-date and accurately reflects the impact of data updates from other nodes, providing more accurate and effective data support for subsequent decisions. It should be pointed out that although there may be insufficient selection of action plans in the initial stage of local intent and even more conflicts between different agents, as the Dec-MCTS algorithm continues to run, the accumulated statistical information in the MCTS gradually improves and optimizes. The intention negotiation process between multiple agents is also constantly deepening, resulting in a more optimized action plan for and a significant reduction in action plan conflicts between agents.

| Algorithm 4: Importance Sampling Intent Update |

|

4.2.3. Heuristic Prediction Algorithm Based on the Rarity of Abilities

In the scenario of multi-robot collaborative work, accurately predicting the future actions of other robots is extremely difficult. This article proposes a heuristic prediction algorithm based on the rarity of abilities. This algorithm aims to predict and optimize the performance of different robots in tasks based on the rarity of the special equipment they are equipped with.

This article defines the concept of capability scarcity to evaluate the rarity of the abilities required by robots to complete specific tasks. For a specific ability cap1, the ability scarcity of robot i possessing that ability can be defined as Formula (2).

This value reflects the proportion of robots with this ability in the entire robot population relative to the importance of this ability in completing tasks. Among them, is the number of robots with this capability, is the total number of robots, and is the coefficient. By considering the degree of capability deficiency, this paper can allocate tasks more effectively, ensuring that robots equipped with rare but important equipment are prioritized for key tasks, thereby improving the efficiency and robustness of the entire multi-robot system.

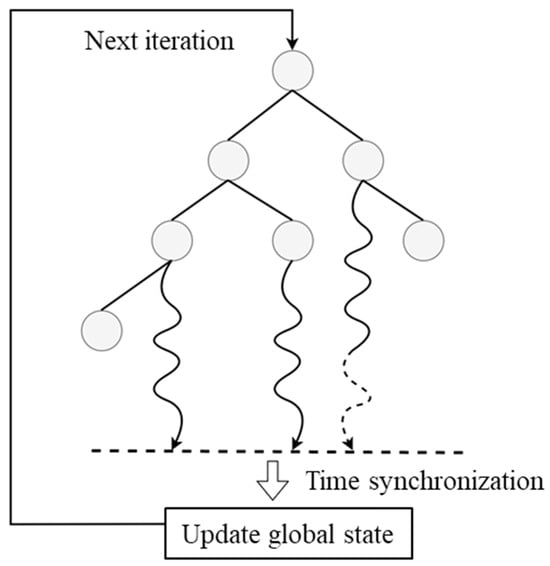

4.2.4. Parallel Enhanced Dec-MCTS (PED-MCTS) Algorithm

The root parallelization strategy refers to independently simulating leaf nodes for processes to achieve maximum depth, and each process independently simulates its assigned leaf nodes until the maximum depth is reached. Although this method cannot completely solve the problem of process synchronization, it can, to some extent, reduce the dependence on local optimal solutions, as it allows the system to explore multiple different search paths simultaneously. Root parallelization further promotes the diversity of the search process, and by exploring different decision paths in parallel, it can, to some extent, avoid overly focused searches on local regions.

As shown in Figure 4, the root parallelization method creates independent search trees, each of which is managed by a separate process. All processes run in independent environments to avoid the complexity of information sharing or mutual interference. The task of each process is to conduct an in-depth state simulation within a specified time , and return the simulated state and results to the main process after the time is up. The responsibility of the main process is to aggregate the data returned by all child processes and form a comprehensive decision result through statistical analysis and synthesis. The significant advantage of this method is that it can significantly reduce the communication requirements between processes, as each process operates independently throughout the entire computation process, except for the initial task allocation and final result aggregation.

In addition, the effectiveness of this method largely depends on the settings of (number of processes) and (available time). Generally speaking, having more processes means being able to explore more state spaces simultaneously, and longer time allows each process to conduct more in-depth simulations, thereby increasing the likelihood of finding the optimal solution. However, this also means that more computing resources and time are required, so in practical applications, the selection of and needs to be carefully balanced based on available hardware resources, task size, and solution accuracy requirements.

5. Experimental Evaluation

5.1. Experimental Setup

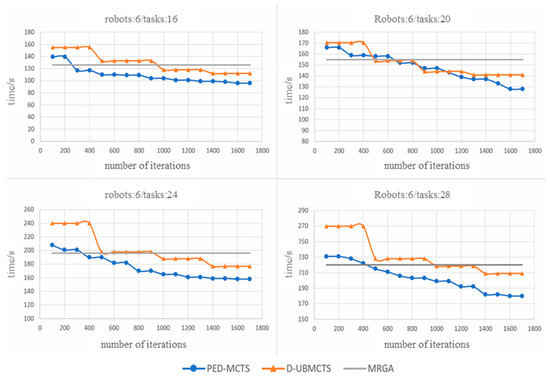

In order to simulate the real environment, this article uses four Husky ground robots and two UAV drones that are the same as the real scene to simulate the real environment. They are tested in large-scale environments with task scales of 16, 20, 24, and 28, respectively [14]. Each robot can synchronize with the agent by sending its own status messages during importance sampling updates or receiving messages from the agent at any time. The experiment adopts a random task arrangement method, conducting 20 experiments and taking the average value.

In order to validate the PED-MCTS algorithm proposed in this paper, it was compared with the following benchmark testing algorithms, including the heuristic method MRGA, which is represented by MRGA in the annotation of the experimental result graph. The central adaptive MCTS algorithm in Section 3 is represented by D-UBMCTS in the figure. The parallelized and decentralized MCTS algorithm is represented by PED-MCTS in the annotation of the experimental result graph.

5.2. Experiment Results

5.2.1. Experimental Results of Central Adaptive MCTS Algorithm

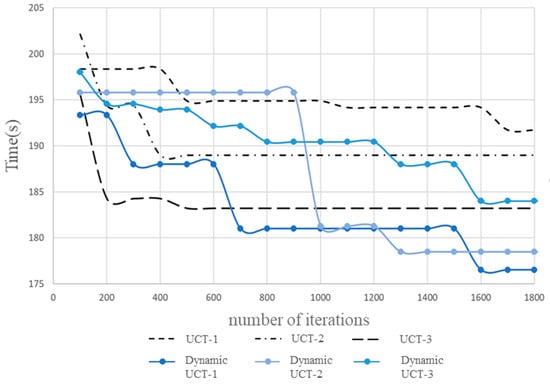

Figure 6 show the results obtained through three random runs of experiments with four robots and eighteen tasks. These results clearly reveal that in multi-agent task allocation problems, the performance of the algorithm has significant characteristics when using dynamic UCT values. With the increase in iteration times, the D-UBMCTS algorithm shows a strong willingness to explore, which is particularly prominent in the application of dynamic UCT values. Compared to traditional static UCT values, the D-UBMCTS algorithm allowed for the adjustment of exploration strategies based on the current exploration situation and obtained information during the iteration process, thereby enabling further optimization of known and well-performing solutions while maintaining exploration of unexplored areas.

Figure 6.

Comparison of results between traditional MCTS algorithm and dynamic D-UBMCTS algorithm.

In addition, the results in Figure 6 also indicate that the introduction of dynamic UCT values significantly improves the performance of the algorithm in long-term operation in the context of multi-agent task allocation. This not only means that the algorithm can make further improvements based on the initial good solution but also indicates that the algorithm has the ability to jump out of local optima and explore potential better solutions. This characteristic is particularly important for dealing with complex task allocation problems, as such problems often have multiple feasible solutions rather than a single optimal solution. By adjusting the exploration coefficient and considering the fluctuation of task reward values, the new formula can encourage the algorithm to focus on high-reward actions while also actively exploring those actions that have not been fully explored. This method not only helps to prevent the algorithm from getting stuck in local optima too early but also increases the possibility of finding the global optimum.

5.2.2. Experimental Results of Parallelized Distributed MCTS Algorithm

- (1)

- The Influence of Capability Scarcity Coefficient k on Task Execution Time

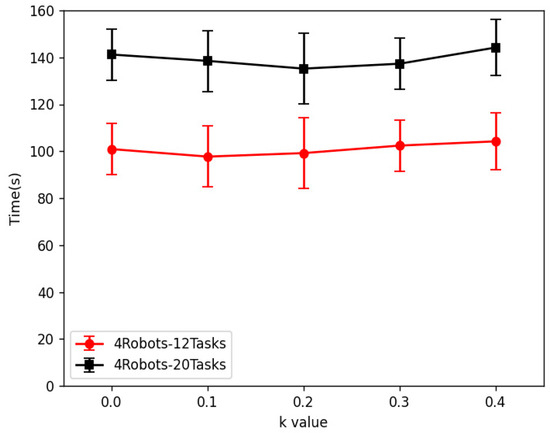

Figure 7 clearly illustrates the impact of the decentralized MCTS strategy on task completion time at different coefficient k values. In this figure, the increasing coefficient k reflects the exploration of strategy adjustment. This article examines the performance of the strategy in two different scenarios, 12 tasks and 20 tasks completed by four robots. Analyzing these results reveals some conclusions.

Figure 7.

Final results with different k values added to the cap Bonus function.

Specifically, in a more complex scenario involving four robots and 20 tasks, as the coefficient k increases, indicating that the agent places greater emphasis on individual task completion, this study observed a decrease in overall task completion time. This result indicates that in situations with a large number of tasks, increasing the coefficient k can motivate the agent to complete individual preference tasks more efficiently, thereby accelerating the overall task completion. However, once the coefficient k increases above 0.2, this trend begins to reverse, as overemphasizing the completion of individual tasks may lead the robot to overlook the opportunity to find the global optimal solution. In other words, machines may fall into short-sightedness, focusing only on quickly completing immediate tasks without prioritizing global task completion efficiency, resulting in a decline in overall performance.

This phenomenon is more pronounced in the simplified scenario of four robots and 12 tasks. When the coefficient k is set to 0.1, the strategy achieves optimal performance, revealing that small biases in individual agent behavior may have a significant impact on the global optimal solution when the task size is small. Because in situations where the number of tasks is small, each individual task has a relatively large impact on the overall outcome, any bias that overly focuses on individual tasks may lead to a decrease in global efficiency. Therefore, for smaller-scale tasks, this article recommends setting the coefficient k slightly lower than the value for larger task scales to avoid over-optimizing local solutions at the expense of overall optimality.

- (2)

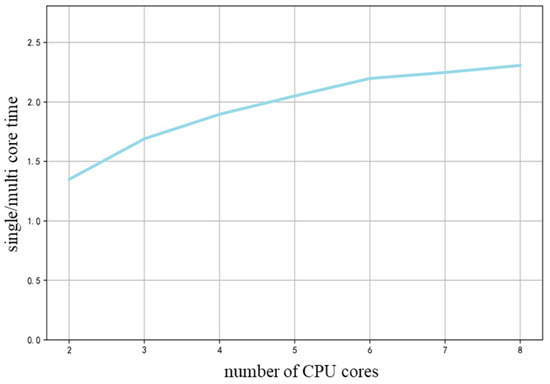

- The impact of the number of CPU cores on experimental results

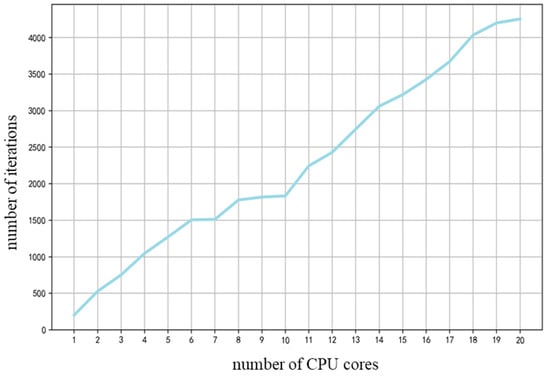

This experiment adopts a gradual expansion method, which gradually increases the number of CPU cores used in the PED-MCTS system, starting from a single core and gradually increasing to 20 cores, in order to simulate different configurations of parallel computing environments. During the experiment, the iteration times of the system running for 5 s were recorded for each number of cores and compared with the running time of a single core to evaluate the performance changes when expanding the parallel processing capability of the system. Through this method, this article can intuitively observe the extent of system performance improvement as the number of processor cores increases.

The experimental results are summarized in Figure 8. The experimental results indicate that as the number of CPU cores gradually increases, the computational efficiency of the system shows an approximately linear growth trend. It is worth noting that the experiment used a high-performance Core i5-13600 K processor, which is equipped with 24 MB of level 3 cache and runs at the default frequency of 3.5 GHz. Thanks to Intel’s hyperprocess technology, the original 14 physical cores have been strengthened to handle up to 20 computing processes simultaneously, significantly increasing the potential for parallel computing.

Figure 8.

Number of iterations increases approximately linearly with the increase in CPU cores.

Figure 9 shows that the ratio of extra time for multiple processes to extra time for a single process increases with the number of processes. Specifically, the ratio did not increase linearly as the number of processing steps increased. This phenomenon is explained in parallel computing environments, as in pure root parallelization settings, each process performs independent search tasks, and there is no obvious contention phenomenon in resource scheduling. Therefore, theoretically, the number of simulations should show a linear relationship with the increase in the number of processes. However, due to the lack of effective communication mechanisms between processes, they were unable to share their simulation results in a timely manner, resulting in overlapping search spaces, which is particularly evident in the later stages of the simulation. Therefore, as the number of processes increases to a certain extent, the contribution of each additional process to improving the total reward gradually decreases, reflecting the marginal effect of parallel processing capability.

Figure 9.

The time difference ratio of multiple processes relative to a single process.

- (3)

- Experimental results under different task scales

Figure 10 presents a clear visual comparison between D-UBMCTS and central MCTS in terms of operational continuity. In this comparison, the distributed method exhibits a clear trend of continuous optimization, indicating its ability to continuously optimize solutions. On the contrary, the centralized approach shows more phased progress, which is significant but discontinuous after each update cycle.

Figure 10.

Comparison of PED-MCTS, D-UBMCTS, and heuristic MRGA algorithms under different task sizes.

This significant difference stems from the core communication mechanism of distributed systems: in this system, the communication of each robot may bring critical new information, which is obtained in real time from any single agent, without relying on centralized and unified information updates from all agents. This mechanism allows distributed systems to quickly respond and integrate new data without waiting for the entire network to synchronize, thereby achieving more stable and continuous global optimization. Every communication between intelligent agents is not just a simple transmission of information but an active part of the continuous optimization process of global solutions. Therefore, the search results for each update stage are not only more accurate but also reflect the latest data and scenario changes, ensuring the timeliness and relevance of solutions.

Through this approach, PED-MCTS is able to continuously adjust and improve its strategies to cope with complex and changing environmental conditions and task requirements, significantly outperforming the lag and adaptability issues that may arise with centralized approaches in large-scale and dynamic environments. This makes distributed MCTS an efficient and flexible strategy, particularly suitable for application scenarios that require rapid response and frequent decision updates.

In large-scale task scenarios, when all six robots participate in task execution simultaneously, as the task size gradually increases, we can clearly observe that the efficiency and effectiveness of the centralized Monte Carlo search method gradually decrease in the initial allocation scheme. This phenomenon is mainly due to the exponential increase in the number of potential action options for each initial state as the task scale expands. This has led to the allocation of initial actions taking decisive importance in the entire solution. If the initial action allocation is poor, it will become extremely difficult to optimize through adjustments later on. Therefore, when dealing with large-scale tasks, the PED-MCTS algorithm performs significantly better in terms of stability and result quality than centralized methods.

By increasing the communication frequency and information exchange volume in distributed systems, each agent can access more global information in a timely manner, which not only effectively improves the search process but also optimizes the search results. This mechanism ensures that as each communication stage is completed, the overall search results will gradually converge toward a better solution. This gradual optimization process is a major advantage of the PED-MCTS algorithm, especially in dynamic and complex task environments that require rapid adaptation and response.

Obviously, through this high-frequency communication and information sharing, PED-MCTS can more effectively synchronize and integrate data and strategies from various agents, thereby demonstrating significant advantages in global optimization problems. This optimization not only improves the efficiency of task execution but also greatly enhances the system’s adaptability and response speed to environmental changes, ensuring the accuracy and efficiency of decision-making in complex environments.

6. Conclusions and Future Work

This study explores the task allocation problem of multi-robot systems in complex dynamic environments, with a particular focus on highly unpredictable offshore oil platform scenarios. Given that traditional static task allocation strategies cannot meet the efficiency and response speed requirements on site, this paper proposes a dynamic task allocation method that combines the MCTS algorithm. This method utilizes the dynamic UCT value and reward optimization of the D-UBMCTS algorithm to achieve fast response and continuous task allocation optimization, effectively improving the initial efficiency and continuous optimization ability of task allocation. Compared with the traditional heuristic method MRGA, the D-UBMCTS algorithm improves the efficiency and adaptability of task processing by optimizing the task execution process in real time within the existing planning time.

In addition, the PED-MCTS method was introduced to enhance the robustness and stability of the system by replacing the centralized allocation process with a distributed independent computing communication process. Distributed processing not only reduces task complexity but also further optimizes time complexity and improves algorithm execution efficiency through importance sampling and parallel optimization schemes. The PED-MCTS method significantly reduces the computation time while ensuring the quality of the solution, improving the processing speed and efficiency of large-scale applications.

In terms of future work, although distributed computing has significantly reduced algorithm complexity and improved efficiency, the system still faces challenges, such as uncontrollable variance in algorithm results, which may affect the stability and predictability of the algorithm. The current model is not yet applicable to all situations, and further adjustments and optimizations are needed for specific environments and conditions. Future research will focus on improving the stability of algorithms, exploring new strategies to better control the variance of algorithm outputs, and enhancing the applicability and predictability of models in various environments.

Author Contributions

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: H.Z.; data collection: Y.S.; analysis and interpretation of results: H.Z. and F.Z.; draft manuscript preparation: H.Z. and Y.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by (1) 2023 Jiangsu University Philosophy and Social Science Research Project (2023SJYB0687); (2) Pujiang College of Nanjing University of Technology, Top Priority Education Reform Project in 2022 (2022JG001Z); (3) Natural Science Key Cultivation Project of Pujiang College of Nanjing University of Technology (njpj2022-1-06). Key project of natural science, Nanjing Tech University Pujiang Institute (NJPJ2024-1-01).

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors upon request.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to the reviewers of this paper for their valuable feedback and constructive suggestions, which greatly contributed to the refinement of this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

- Patrick, B.; Charles, L.; Magali, B. Hybrid planning and distributed iterative repair for multi-robot missions with communication losses. Auton. Robot. 2020, 44, 505–531. [Google Scholar]

- Èric, P.; Paola, A.; Katrin, S. A Digital Twin for Human-Robot Interaction. In Proceedings of the ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction, Daegu, Republic of Korea, 11–14 March 2019; IEEE: New York, NY, USA; p. 372. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, L.; Peng, P.; Lu, Z.; Tian, Y. MetaVIM: Meta Variationally Intrinsic Motivate Reinforcement Learning for Decentralized Traffic Signal Control. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2023, 35, 11570–11584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Jia, H.; Lu, Z. Hierarchically and Cooperatively Learning Traffic Signal Control. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2–9 February 2021; pp. 669–677. [Google Scholar]

- Fioretto, F.; Pontelli, E.; Yeoh, W. Distributed constraint optimization problems and applications: A survey. J. Artif. Intell. Res. 2018, 61, 623–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Ye, Y.; Ding, J.; Wang, T.; Wei, T.; Chen, M. Ipdalight: Intensity-and phase duration-aware traffic signal control based on reinforcement learning. J. Syst. Archit. 2022, 123, 102374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Q.; Qin, M.; Shi, S.; Sun, W.; Zheng, B. Multi-agent reinforcement learning for traffic signal control through universal communication method. arXiv, 2022; arXiv:220412190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, N.; Li, D.; Xi, Y. Distributed Weighted Balanced Control of Traffic Signals for Urban Traffic Congestion. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2018, 20, 3710–3720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, R.; Smith, S. Expressive real-time intersection scheduling. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Orleans, LA, USA, 2–7 February 2018; pp. 6177–6185. [Google Scholar]

- Cashmore, M.; Fox, M.; Larkworthy, T.; Long, D.; Magazzeni, D. AUV mission control via temporal planning. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Hong Kong, China, 31 May–5 June 2014; pp. 6535–6541. [Google Scholar]

- Cashmore, M.; Fox, M.; Long, D.; Long, D.; Magazzeni, D. ROSPlan: Planning in the robot operating system. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Automated Planning and Scheduling, Jerusalem, Israel, 7–11 June 2015; pp. 333–341. [Google Scholar]

- Anthony, T.; Tian, Z.; Barber, D. Thinking fast and slow with deep learning and tree search. In Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS), Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017; pp. 5366–5376. [Google Scholar]

- Hertle, A.; Bernhard, N. Efficient auction based coordination for distributed multi-agent planning in temporal domains using resource abstraction. In Proceedings of the Joint German/Austrian Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Berlin, Germany, 24–28 September 2018; pp. 86–98. [Google Scholar]

- Carreno, Y.; Pairet, È.; Petillot, Y.; Petrick, R.P. Task allocation strategy for heterogeneous robot teams in offshore missions. In Proceedings of the 19th International Conference on Autonomous Agents and MultiAgent Systems, Visual, 9–13 May 2020; pp. 225–230. [Google Scholar]

- Bogue, R. Robots in the offshore oil and gas industries: A review of recent developments. Industrial Robot. Int. J. Robot. Res. Appl. 2020, 47, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.; Andrejczuk, E.; Irissappane, A.A.; Zhang, J. ATSIS: Achieving the ad hoc teamwork by subtask inference and selection. In Proceedings of the International Joint Conferences on Artificial Intelligence (IJCAI), Macao, China, 10–16 August 2019; pp. 172–179. [Google Scholar]

- Kurzer, K.; Zhou, C.; Zöllner, J.M. Decentralized cooperative planning for automated vehicles with hierarchical Monte Carlo tree search. In Proceedings of the Intelligent Vehicles Symposium (IV), Suzhou, China, 26–30 June 2018; pp. 529–536. [Google Scholar]

- Kurzer, K.; Engelhorn, F.; Zöllner, J.M. Decentralized cooperative planning for automated vehicles with continuous monte carlo tree search. In Proceedings of the 21st International Conference on Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITSC), Maui, HI, USA, 4–7 November 2018; pp. 452–459. [Google Scholar]

- Silver, D.; Huang, A.; Maddison, C.J.; Guez, A.; Sifre, L.; Van Den Driessche, G.; Schrittwieser, J.; Antonoglou, I.; Panneershelvam, V.; Lanctot, M.; et al. Mastering the game of Go with deep neural networks and tree search. Nature 2016, 529, 484–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silver, D.; Schrittwieser, J.; Simonyan, K.; Antonoglou, I.; Huang, A.; Guez, A.; Hubert, T.; Baker, L.; Lai, M.; Bolton, A.; et al. Mastering the game of Go without human knowledge. Nature 2017, 550, 354–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coulom, R. Efficient selectivity and backup operators in Monte-Carlo tree search. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Computers and Games, Turin, Italy, 29–31 May 2006; pp. 72–83. [Google Scholar]

- Gelly, S.; Silver, D. Combining online and offline knowledge in UCT. In Proceedings of the 24th International Conference on Machine Learning, Corvallis, OR, USA, 20–24 June 2007; pp. 273–280. [Google Scholar]

- Van den Broeck, G.; Driessens, K.; Ramon, J. Monte-Carlo tree search in poker using expected reward distributions. In Proceedings of the Advances in Machine Learning: First Asian Conference on Machine Learning, Nanjing, China, 2–4 November 2009; pp. 367–381. [Google Scholar]

- Gabor, T.; Peter, J.; Phan, T.; Meyer, C.; Linnhoff-Popien, C. Subgoal-based temporal abstraction in Monte Carlo tree search. In Proceedings of the International Joint Conferences on Artificial Intelligence (IJCAI), Macao, China, 10–16 August 2019; pp. 5562–5568. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, K.Q.; Thawonmas, R. Monte carlo tree search for collaboration control of ghosts in ms. pac-man. IEEE Trans. Comput. Intell. AI Games 2012, 5, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepels, T.; Winands, M.H.M.; Lanctot, M. Real-time monte carlo tree search in ms pac-man. IEEE Trans. Comput. Intell. AI Games 2014, 6, 245–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesauro, G.; Rajan, V.; Segal, R. Bayesian inference in monte-carlo tree search. arXiv 2012, arXiv:12033519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eysenbach, B.; Salakhutdinov, R.; Levine, S. Search on the Replay Buffer: Bridging Planning And Reinforcement Learning. In Proceedings of the Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 8–14 December 2019; pp. 15246–15257. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, B.S.; Bernardino, H.S. Game state evaluation heuristics in general video game playing. In Proceedings of the 17th Brazilian Symposium on Computer Games and Digital Entertainment (SBGames), Foz do Iguaçu, Brazil, 29 October–1 November 2018; pp. 14701–14709. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.; Dong, P.; Wei, Z.; Yang, Y. Automated knowledge distillation via monte carlo tree search. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Paris, France, 2–3 October 2023; pp. 17413–17424. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).