Abstract

Semantic scene reconstruction from sparse and incomplete point clouds is a vital task in understanding point scenes. This task involves assigning semantic labels to objects and reconstructing their complete shapes as meshes. In recent years, researchers have adopted a “reconstruction from recognition” approach, which first segments foreground objects from the point cloud and then completes and reconstructs them as mesh representations. This method has successfully facilitated both the semantic and geometric understanding of point scenes. However, existing approaches based on deep learning often depend on supervised training, requiring extensive annotations and incurring high training costs. To address this limitation, we introduce unsupervised algorithms for completing and reconstructing partial observations. While Transformer-based autoregressive shape completion shows great potential, there has been limited research on applying it to complete instances segmented from real-world scenes. To bridge this gap, we propose VRC (unsupervised semantic scene reconstruction via Transformer-based quantized Vector Reconstruction and autoregressive Completion), a novel framework that integrates unsupervised algorithms with Transformer-based autoregressive completion. Our approach enables the unsupervised reconstruction of real-world scenes. Comparisons with state-of-the-art methods on authoritative public datasets demonstrate that VRC achieves superior reconstruction performance with significantly reduced data costs.

1. Introduction

Semantic scene reconstruction takes scanned point clouds as input, segments foreground objects from the scene, predicts their semantic categories and complete shapes, and generates a three-dimensional scene that is semantically accurate, geometrically complete, and features smooth surfaces [1]. It achieves the semantic and geometric perception of the 3D scene, approaching or even surpassing human perceptual abilities. Semantic scene reconstruction holds significant research value in the fields of robotics, VR/AR, and interior design [2,3,4].

As the most common representation of 3D data, scanned point clouds lack semantic information and often have incomplete shapes. Several previous algorithms for point scenes focused on segmenting foreground objects with semantics from point scenes, lacking a comprehensive understanding of the point scenes [5,6,7,8,9,10]. In recent years, semantic scene completion has begun to address both the semantic and geometric aspects of scenes by predicting the semantic information of all voxels in space. However, these works are typically limited by the low-resolution dense voxel grids and are unable to reconstruct high-fidelity objects in the scene [11,12,13].

To address these issues, semantic scene reconstruction adopts a reconstruction-from-recognition pipeline. It extracts foreground objects from point scenes using instance segmentation and reconstructs them as mesh representations with semantic information.

1.1. 3D Instance Segmentation Object Completion

Object-level shape completion [14] aims to reconstruct complete shapes from partially observed objects. The supervised shape completion methods have shown good performance, but they face challenges in generalizing the real world due to difficulties in collecting paired data and potential mismatches in data distribution between real and synthetic 3D shapes [15,16,17]. To address these issues, Pcl2pcl [11] proposes an unsupervised framework for shape completion tasks. It trains two independent autoencoders and utilizes Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) [18] to learn mapping functions from the latent space of incomplete shapes to the latent space of complete shapes.

Shape completion is a conditional generation task, and a single partial observation may correspond to multiple possible complete shapes. Therefore, some works have introduced probabilistic generative models into object shape completion. These studies [19,20,21] utilize Transformer-based token inference to complete shapes, converting 3D shapes into discrete feature vectors, enabling their representation as tokens analogous to those used in natural language processing, which forms the basis for multimodal large models. AutoSDF [20] successfully achieves the natural language-based conditional generation of 3D models. However, existing autoregressive conditional generation models based on Transformer token inference only focus on completing simple, incomplete point clouds with ideal completion conditions and uniform point cloud distribution without noise. It exhibits limitations in completing real scene point clouds involving irregular distributions and many noisy points [22].

1.2. Scene Completion

Scene completion aims to reconstruct all objects in a partially scanned 3D scene. Semantic scene completion voxelizes the point cloud into dense voxel grids and predicts semantic labels of all voxels in both visible and occluded regions. Representative studies in semantic scene reconstruction of point cloud scenes include the following: (i) Scan2CAD [23], which relies on pose matching to align CAD models from ShapeNet with foreground objects in point scenes, achieving semantic reconstruction through retrieval. However, its generalizability is limited due to reliance on synthetic model datasets. (ii) RfD-Net [24], which employs object detection followed by instance completion to achieve complete semantic scenes utilizing generative networks, needless of a synthetic model database. But relying on object detection leads to many false positive results and multiple pre-annotated information is required for training. (iii) DIMR [25], which replaces the object detection framework in RfD-Net with an instance segmentation framework to reduce false positive segmentation results. It also enhances semantic reconstruction by completing in the latent code domain, improving the instance completion accuracy. However, the reconstruction accuracy of the resulting model is moderate, and its training also relies on various pre-annotated information. Existing deep learning-based semantic reconstruction works for point scenes and can reconstruct semantic polygon mesh models from point cloud scenes but requires multiple pre-annotated datasets for training, leading to high training costs [26,27].

The semantic scene reconstruction typically relies on supervised learning, requiring large amounts of annotated training data for semantic categories, instance encoding, and ground truth pairing between incomplete point clouds and complete mesh models, resulting in high training costs and potential inaccuracies. By contrast, leveraging GANs (Generative Adversarial Networks) enables shape completion tasks without explicit pairing information, reducing data costs.

Shape completion, inferring complete shapes based on incomplete shape inputs, falls under conditional generation tasks. VQ-VAE (Vector Quantized Variational AutoEncoder) [28] enables 3D models to be tokenized like natural language, thus allowing for the use of Transformers for autoregressive conditional generation tasks between 3D shapes, two-dimensional images, and natural language. This conditional generation task is the foundation for multimodal universal large models and holds high research value. However, existing research on using these models for shape completion tasks typically involves simplifications [29,30,31], which limit their applicability to real scene point cloud completion tasks.

The main contributions of our work are as follows:

We employ an unsupervised approach to accomplish semantic scene reconstruction. GANs are leveraged to map the features of proposal point clouds to the manifold distribution of complete point cloud features. Subsequently, a Transformer is employed to infer complete tokens from the mapped features and decode them, achieving unsupervised shape completion without requiring paired information between partial observations and complete shapes.

We propose our VRC (unsupervised semantic scene reconstruction via Transformer-based quantized Vector Reconstruction and autoregressive Completion) framework, fully utilizing the structural information of relatively complete parts of proposal point clouds and enabling autoregressive completion and reconstruction of real scene point clouds. When inferring tokens for blank areas, we mask the mapping features to enhance the realism of completion results.

The experiments conducted on international open datasets demonstrate that our proposed framework achieves semantic scene reconstruction without relying on paired data between partial observations and complete shape. Through quantitative and qualitative comparisons with the state-of-the-art (SOTA) methods in the field, our method maintains favorable reconstruction performance with lower training data costs. Furthermore, the ablation experiments demonstrate that our new token generation scheme improves the effectiveness of Transformer-based autoregressive completion for point cloud completion from real scenes.

2. Materials and Methods

Semantic scene reconstruction involves multiple tasks, such as foreground object extraction, semantic prediction, bounding box prediction, and shape reconstruction [32,33]. Among these tasks, shape reconstruction is the most critical, as it directly impacts the overall accuracy of semantic scene reconstruction, and existing algorithms perform poorly in this aspect. Additionally, unsupervised shape reconstruction requires frequent iterative updates to the network; coupling this process with other task branches would lower experimental efficiency. Therefore, we first extract foreground objects from the point scene and apply our unsupervised framework VRC on their completion and reconstruction.

2.1. Point Scene Semantic and Instance Segmentation

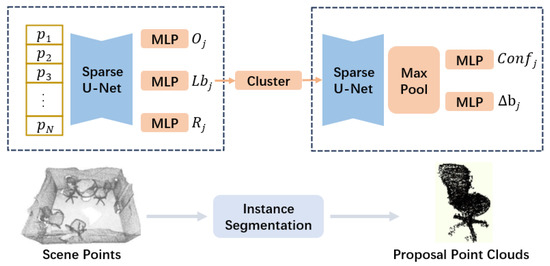

The tasks of extracting foreground objects and predicting their bounding boxes and semantic information from point scenes are in two stages. In the first stage, the model learns features from the point scene and predicts the point clouds’ semantics, rotation direction, and centroid offset. In the second stage, cluster similar points to obtain proposal point clouds and then learn proposal features to predict their confidence and bounding box residuals. Figure 1 shows the architecture of our foreground object segmentation backbone.

Figure 1.

Point scene semantic and instance segmentation network.

We represent the input point scene as = {p1, p2, …, pN}, where pi = (xi, yi, zi) and i ∈ (1, N), denotes the 3D coordinates of points in the scene. Initially, we convert into regular voxel data and extract voxel features Fvoxel. Subsequently, Fvoxel is mapped to each point to obtain point-level features Fpoint ∈ N×Dpoint, where Dpoint represents the feature dimension. A 3D sparse convolutional U-Net [34] was adopted as the backbone network to address the challenges of the large scale of point scene data and sparsity of features, which not only effectively extracts meaningful features from the scene but also controls the number of voxels during the feature extraction process, enhancing model computational efficiency.

We establish three MLP (Multilayer Perceptron) [35] branches based on to predict point center offsets , semantic labels , and point orientations . Based on and the translated coordinate set , each point is shifted towards the center of mass of the corresponding object, improving clustering performance. Then, a clustering algorithm is employed to group points with the same semantic label and close proximity into proposal point clouds , where each is a subset of . The orientation branch predicts the direction of instance points for regressing directed bounding boxes. To better aggregate proposal-level features, proposal point clouds are normalized to a unified normalized coordinate system before voxelization. The approximation of the proposal point cloud center and average angle is achieved as follows:

where represents the 3D coordinates of points in the proposal point cloud, and denote the offset and angle of the point, and is the set of all points in the proposal point cloud. Using to de-center the proposal, the rotational coordinate differences between the maximum and minimum values are calculated to obtain , which is then used to scale the coordinate values of the proposal to the [0, 1] interval.

In the second stage, proposal point clouds are voxelized with the feature . These voxelized representations are processed by a 3D sparse U-Net and max-pooling layers to output proposal-level features , where describes the dimension of proposal features, and is the number of proposal point clouds. A smaller 3D sparse U-Net network learns to predict the confidence and residual bounding box for each proposal point cloud, effectively mitigates the computational explosion while maintaining high accuracy.

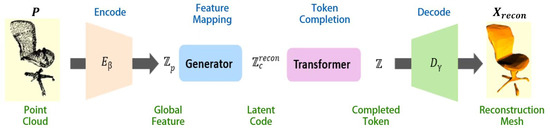

2.2. VRC Framework

Our proposed unsupervised completion and reconstruction process of VRC is illustrated in Figure 2. The proposal point cloud undergoes four transformations to obtain a complete polygon mesh model. The global features of are extracted using the encoder , and then mapped without supervision to by the generator . The Transformer is employed to probabilistically deduce the tokens of and then complement to obtain the token sequence , and the decoder decodes into the complete polygon mesh model . Through the innovative construction of the above framework, we achieve unsupervised probabilistic reconstruction of real partial observations.

Figure 2.

VRC pipeline.

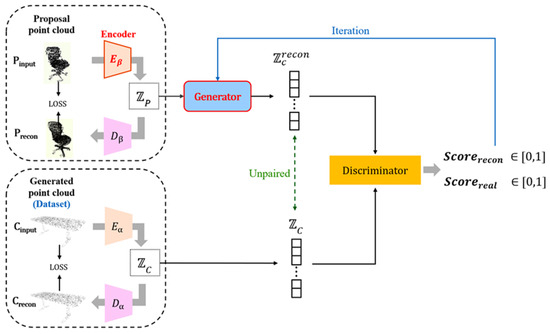

2.3. Latent Code Mapping via GAN

Firstly, we construct a point cloud autoencoder based on the PointNet [11] network to extract global features of proposals and generate point clouds. This autoencoder consists of encoder E and decoder D. It extracts the features and of the proposal and synthetic point clouds, respectively, where and correspond to the generated point cloud set , and and correspond to the proposal point cloud set . The self-reconstruction framework for synthetic point clouds is illustrated in Figure 3. To supervise the learning of the latent vector spaces for both point cloud sets, the Chamfer Distance (CD) loss function [36] is employed, as it has no requirement for consistency in the number of points between compared point clouds.

Figure 3.

Generative Adversarial Network.

An unsupervised Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) is used to map to the feature manifold of after extracting features and , and it also reduces the cost of shape completion training. Figure 4 shows the network structure and training process of our unsupervised feature map. A stable training method called the Least Square GAN (LSGAN) [37] is used to accomplish the unsupervised feature mapping task.

Figure 4.

Three-dimensional shape tokenization.

The CD loss function is used to determine the similarity of two point clouds by sequentially calculating the minimum value of the distance between each point of the object’s point cloud and all points of the other point cloud, and then averaging them. It is used to supervise two autoencoders to learn the latent vector space of the proposal point cloud set and the synthetic point cloud set . The loss functions are defined as follows:

where and represent synthetic and proposal point clouds, and and represent real and synthetic point cloud datasets. and denote the training loss functions for synthetic and proposal point clouds, respectively.

The generator is trained to produce a mapping result of to successfully deceive the discriminator which distinguishes between and . The discriminator is designed as a structure capable of perceiving categories and is used to categorize the point cloud among the eight common indoor items to which belongs. The latent vectors are fed into the discriminator, and F outputs nine probability values, representing the probabilities of the input being one of the eight semantic categories or a reconstructed point cloud. The Softmax [38] activation function is applied to these nine probability values to ensure they sum to 1. Through iterative training between the generator and discriminator through the iterations between the generator and discriminator, allowing mapping to . During training, the training process does not require paired information between the proposal point cloud and the complete shape.

For training LSGAN, the discriminator takes the features and of the synthetic point cloud as input and outputs the probability value that the feature belongs to the synthetic point cloud. Considering the semantic category of the latent vectors, the discriminator’s output is subtracted from the one-hot encoding of the semantic labels to obtain the loss value , and similarly subtracted from the one-hot encoding with the ninth channel set to 1 to obtain the loss value . The loss functions are defined as follows:

where represents the proposal point cloud dataset, represents the synthetic point cloud dataset, and are point clouds sampled randomly from datasets without shape pairing, is the generator, is the discriminator, and is obtained by adding and . The generator’s loss function also includes two terms, which are used for supervising the mapping capability and reconstruction consistency of the generator. The equations are as follows:

where is the pre-trained decoder for synthetic point clouds used to decode or into complete point clouds, and is the one-directional CD loss function controlling the similarity between and .

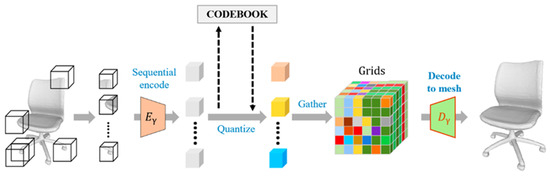

2.4. Three-Dimensional Shape Tokenization

The deep learning-based point cloud completion task learns a mapping function through backpropagation and gradient updates, aiming to predict the complete shape from partial observation . Given the same incomplete point cloud, it may correspond to multiple complete shapes, indicating that the function is not injective. As shown in Formula (1), this non-injective nature causes the network to learn intermediate representations corresponding to in order to minimize the loss function. Consequently, the completion result of the network becomes an interpolation of multiple real object shapes, which is inherently unrealistic and has a blurred distribution. This non-probabilistic completion method greatly reduces the quality of the completion results.

To address this issue, we divide the whole shape into blocks, independently extract features from local regions of 3D shapes as tokens, and complete the shape based on the probability derivation of to improve the fidelity of the reconstruction results.

As shown in Figure 4, for a 3D shape , the encoder of VQ-VAE is first utilized to extract low-dimensional features in a block-wise manner, and then the decoder decodes the features into a 3D shape. The entire process can be described using the following formula:

where denotes vector quantization, which means finding the closest feature vector to the input feature from the codebook and outputting it. represents the 3D quantized feature grid data. Initially, the input three-dimensional model is partitioned into mutually independent 6 × 6 × 6-sized cubic regions, and each region contains 8 × 8 × 8 voxels. Then, the encoder is used to independently extract features from each cubic region. Once the discrete features are obtained, vector quantization is applied to using the discrete features stored in the codebook to convert the discrete features into a finite set of deterministic distributions. Subsequently, the decoder decodes the three-dimensional quantized feature grid into a complete voxel model . The transformation of the shape into a 3D token grid enables the task of learning the probability distribution of possible complete shapes of the input incomplete point cloud to be transformed into the task of learning the probability distribution of .

The Transformer completes the supervision by minimizing the expectation of the negative log-likelihood function, expressed as follows:

where represents the cross-entropy loss function, represents the ground truth tokens, and represents the predicted tokens used to retrieve token vectors in the codebook.

The loss function of VQ-VAE includes two parts, namely reconstruction loss and codebook construction loss, which are used to supervise the construction of the codebook. The formula is as follows:

represents TSDF (truncated signed distance function) [39] voxel data, which encode the distance from each voxel to the nearest surface in a 3D space, corresponding to the input polygon mesh model. represents TSDF voxel data corresponding to the reconstructed polygon mesh model, represents gradient truncation, is the quantization feature directly output by , and is the quantization feature from the codebook after vector quantization.

2.5. Token Autoregressive Generation

The task of completing involves predicting the unknown parts based on the known parts, but the distribution of known shapes is not fixed. To address the completion problem caused by the disorderliness of the distribution of three-dimensional shapes, AutoSDF generates token grids in an unordered manner. It predicts the probability distribution of the next position token based on the known but disorderly token set combined with the information of the next position to be predicted. However, the random prediction approach of AutoSDF lacks stability and cannot ensure effective planning of the generation sequence using known information. ShapeFormer [19] introduces a position prediction module to address the completion order issue by first predicting the next position to be completed and then predicting the token at that position. However, the addition of a separate Transformer for position prediction significantly increases the complexity of the network.

We propose a solution to the aforementioned token prediction sequence problem as follows:

Firstly, the input proposal point cloud is divided into blocks, and the number of points in each block is counted. When the number of points in a token block is more than 50, we represent this part of the token as , indicating that the corresponding shape is relatively complete. is reconstructed using the global feature . When the number of points is less than 50, we represent this part of the token as , indicating severe shape incompleteness and multiple possibilities. Probability inference based on known structural information from previous text is required in this case. Therefore, can be expressed as the following formula, where represent the three-dimensional coordinates of the token’s location.

Secondly, we convert the blocks to voxel format. Then, reconstruct the tokens in order from blocks with more points to blocks with fewer points. The more points within a token, the stronger the determinacy of its shape. We fully leverage the structural information of the relatively complete portion of the proposal point cloud and ensure high-quality reconstruction. This prediction sequence utilizes the distribution of the input points to plan the token generation sequence, providing a simple and efficient token generation scheme. The sequence of token derivation is as indicated by the following formula, where denotes the number of point clouds of the proposal point cloud in the th block of token areas.

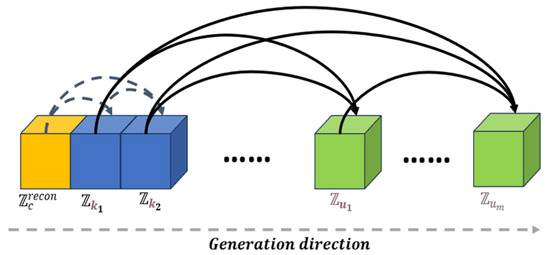

We use the Transformer as the token generation model. The token is probabilistically derived from , which is generated by an unsupervised generator, thereby completing the unsupervised shape completion task and reducing the training data cost. The distribution of blank tokens depends entirely on the distribution of tokens in the complete parts and does not utilize the global feature . This avoids potential ambiguity in the global feature and reduces its adverse effects on the completion of blank areas. The token generation process is illustrated in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Token generation based on Transformer.

When deriving the probability distribution for each and , the 3D coordinates of the position to be derived should also be considered. The conditional probability formulas for and are as follows:

where is the number of unknown tokens, is the number of known tokens, the total number of tokens is , represents the three-dimensional coordinates of blank area tokens, represents the three-dimensional coordinates of tokens for complete areas.

Two different masks are applied to the same Transformer to achieve training for two distinct inference modes. During the training for inferring based on global features, the mask is set to 0 at subsequent positions to prevent the model from utilizing subsequent context for inference. Conversely, during the training for predicting based on , the mask is set to 0 at the global features and after the predicted positions to prevent the model from using global features and subsequent context for inference.

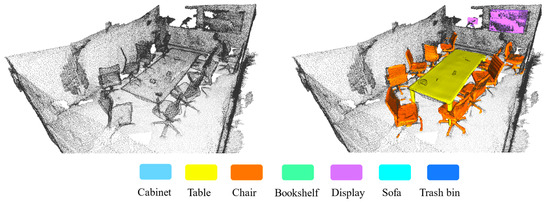

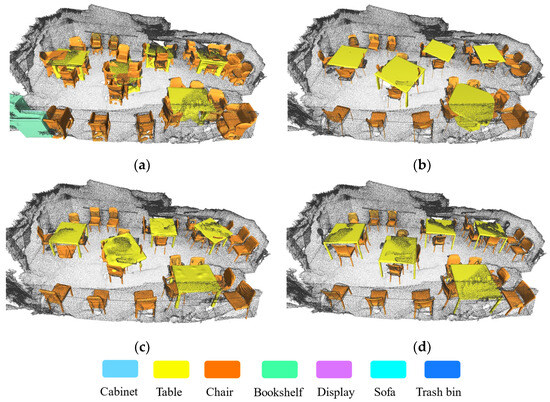

Finally, , the complete polygon mesh model, is obtained by decoding composed of and using . Meanwhile, combined with the semantic information and bounding box information of the proposal point cloud , the semantic reconstruction results of the point cloud scene can be obtained, as shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Point scene semantic reconstruction result of VRC.

3. Results

3.1. Experiment Setup

3.1.1. Experimental Purpose

In order to comprehensively verify and analyze the reconstruction effect of the VRC algorithm proposed in this paper, this section takes the representative methods in the reconstruction field as the comparison object and carries out qualitative and quantitative experiments.

3.1.2. Dataset

The experiments of point cloud semantic reconstruction algorithms utilize three datasets: ScanNet (v2) [40], ShapeNet [41], and Scan2CAD [23]. ScanNet comprises 1513 real scanned scene point clouds, accompanied by point labels describing their semantic categories and instance numbers. The Scan2CAD dataset provides a correspondence between ScanNet instances and ShapeNet synthetic object models. Due to conflicting labeling systems between ScanNet and ShapeNet affecting the reconstruction performance, this paper adopts the compatible labeling system from DIMR. However, the VRC algorithm does not require pairing information between instance point clouds and complete CAD models provided by Scan2CAD.

3.1.3. Training Details

Due to the complexity and time-consuming nature of GAN training, a staged training and deployment approach is adopted. Firstly, an instance segmentation network is utilized to obtain the incomplete point cloud objects to be reconstructed from the point scene, along with the bounding boxes, semantic categories, and confidence information of the point cloud objects.

The autoencoders for extracting latent vectors from real and synthetic point clouds adopt the PointNet structure, which acquires global features in two layers. An unsupervised method is used to map the latent vectors, transforming into , with an MLP serving as the foundational architecture for the generator and discriminator. Due to the difficulty in training adversarial generative networks, which may lead to gradient vanishing or exploding phenomena, the model structures employed are relatively simple.

The TSDF voxel grid data with a resolution of 48 × 48 × 48 are segmented into block sizes of 6 × 6 × 6, with each block containing data of voxel sizes 8 × 8 × 8. VQ-VAE encodes the voxel data within each block to obtain discrete vector features with a dimensionality of 512. In the vector quantization part, both the codebook size and the feature dimensionality in the codebook are set to 512. During decoding, the quantized features are decoded back into TSDF voxel grid data of size 8 × 8 × 8. The encoder and decoder mainly consist of 3D convolution and attention modules [42]. The input feature dimensionality for the Transformer is 728, with a feature dimensionality of 216 for the feedforward neural network, 12 attention heads, a dropout rate of 0.1, ReLU activation functions, and 12 layers. The feature dimension of the feedforward network is the same as the quantization vector of the VQ step, which is used to update the derivation of the Token sequence. The vector dimension of the input Transformer network includes the 512-dimension feature vector of shape encoding.

3.2. Comparison with the State-of-the-Art

3.2.1. Qualitative Analysis

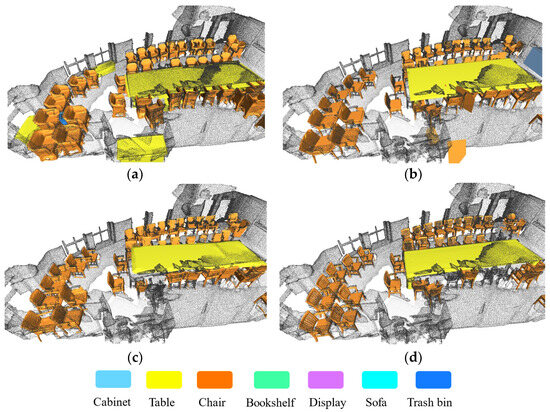

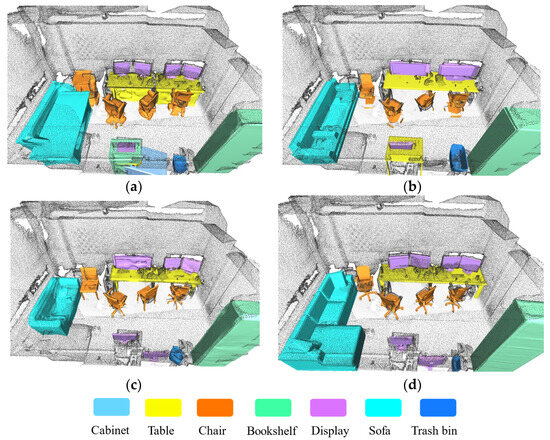

The reconstruction dataset we use targets indoor scenes, and the reconstructable object categories include eight categories: cabinets, bathtubs, tables, chairs, bookshelves, cabinets, sofas, and trash cans. Among them, tables and chairs appear most frequently and have various shapes, orientations, and distribution locations, which make reconstruction more difficult. Therefore, we selected three scenarios containing many tables and chairs, namely classroom, office, and conference room, from a total of 311 test data samples to compare the semantic reconstruction performance of different algorithms.

Figure 7, Figure 8 and Figure 9 present comparative reconstruction results of representative state-of-the-art methods, including RfD-Net, DIMR, and the proposed VRC, against the ground truth Scan2CAD.

Figure 7.

Reconstruction results of a large conference room scene: (a) RfD-Net; (b) DIMR; (c) VRC; (d) GT.

Figure 8.

Reconstruction results of an office scene: (a) RfD-Net; (b) DIMR; (c) VRC; (d) GT.

Figure 9.

Reconstruction results of a classroom scene: (a) RfD-Net; (b) DIMR; (c) VRC; (d) GT.

We conduct a qualitative comparison and analysis of semantic reconstruction results from four aspects: shape integrity, structural accuracy, consistency with the input, and point cloud conformity, with a focus on VCR’s performance.

In terms of shape integrity, all three algorithms perform well, reconstructing item structures comprehensively. However, structural accuracy highlights VRC’s superiority. For instance, in Figure 7, VRC reconstructs the chair back and leg structures with greater precision, while RfD-Net produces coarser results, and DIMR performs slightly better than RfD-Net. In Figure 8, VRC accurately captures the leg structure of swivel chairs, which RfD-Net and DIMR fail to reconstruct correctly. RfD-Net and DIMR occasionally generate extraneous components or miss critical details, whereas VRC demonstrates higher reliability in preserving the input’s details. For point cloud conformity, VRC and DIMR perform well, ensuring their reconstructed surfaces align closely with the scene point cloud. In contrast, RfD-Net struggles, often producing structures that deviate from the point cloud, resulting in poor alignment between the polygon mesh and the scene point cloud.

Overall, VRC consistently outperforms RfD-Net and DIMR across these metrics, showcasing its effectiveness in detailed and accurate semantic reconstruction.

3.2.2. Quantitative Analysis

In the quantitative comparative experiments section, the performance of the proposed algorithm and representative algorithms in the field are compared in the reconstruction of 311 indoor scene point clouds used for testing. The indoor scenes used for testing include classrooms, bedrooms, bathrooms, meeting rooms, offices, and living rooms, covering various common indoor scenarios.

For the evaluation of reconstruction completeness, the similarity between the polygon mesh models reconstructed by VRC, RfD-Net, and DIMR, and the data in Scan2CAD serving as ground truth are calculated. Reconstruction fidelity is evaluated by measuring the distance between reconstructed results and instance point cloud surfaces from ScanNet.

We used the following metrics to evaluate the reconstruction effect: IoU@, CD@, LFD@, and PCR@, where IoU@ represents the proportion of Intersection over Union greater than a certain value; CD@, LFD@, and PCR@ represent the proportion of chamfer distances, Light Filed Distance, and Point Coverage Ratio less than a certain value.

Among them, LFD is an index to evaluate the reconstruction effect by capturing the geometric and texture information of 3D shapes. It extracts the feature vectors of multi-view images, calculates the feature differences from view to view, and combines weighted average and normalization to finally obtain the global similarity measure of two groups of light fields.

PCR is used to evaluate the consistency between the input point cloud and the reconstructed point cloud. It evaluates the coverage by calculating the distance from each point in the input point cloud to the nearest point in the reconstructed point cloud and counting the proportion of points whose distance is less than the threshold, which reflects the coverage of the reconstructed point cloud to the input point cloud.

The AP (Average precision) value is commonly used to measure the comprehensive performance of recall and precision of instance reconstruction results. It represents the area of the region formed by the PR (Precision–Recall) curve and the horizontal axis.

As shown in Table 1, The performance of VRC falls between that of RfD-Net and DIMR. Particularly, its performance on CD@0.047 even exceeds that of RfD-Net and DIMR. Notably, the evaluation of reconstruction quality compares the reconstructed results with the annotated results in Scan2CAD. However, VRC was not trained using data provided by Scan2CAD.

Table 1.

Comparison of reconstruction quality.

Table 2 presents a comparison of the percentages of AP values for various methods (under standard PCR@0.5). It reveals that in terms of reconstruction fidelity quality, VRC’s average performance significantly outperforms Scan2CAD and RfD-Net while being comparable to DIMR. The mapping quality on the Table, Chair, Trash bin, and Bathtub categories is particularly outstanding.

Table 2.

Comparison of mapping quality.

3.2.3. Ablation Study

To validate the effectiveness of the proposed token derivation scheme, we conducted ablation experiments on different token derivation approaches. Table 3 illustrates three different token generation schemes: , which randomly reconstructs all tokens based on global features, a method also employed in AutoSDF; , which reconstructs all tokens in descending order of incompleteness measured by the number of points in the token region from the input point cloud P; and which prioritizes the reconstruction of relatively complete regions based on incompleteness, with token regions having completeness below a threshold completed solely based on preceding tokens without relying on global features.

Table 3.

Ablation experiment of VRC.

- The effect of reconstruction in order of incompleteness: Table 3 indicates that compared to random reconstruction, reconstructing tokens in order of decreasing incompleteness of token regions effectively enhances the quality and fidelity of reconstruction. Specifically, there is an improvement of 2.31% in IoU@0.25, 0.33% in IoU@0.5, 1.06% in CD@0.1, 0.19% in CD@0.047, and 1.22% in PCR@0.5. The reason lies in the sequential reconstruction based on the degree of incompleteness, which effectively utilizes existing structural information, thereby yielding higher quality completion results, whereas random ordering may first generate blank parts before generating already complete regions.

- The effect of reconstruction followed by completion: Table 1, Table 2 and Table 3 show that by reconstructing first and then completing, VRC performs best in most indicators, particularly showing significant improvements in reconstruction quality indicator CD@0.1 and reconstruction mapping quality indicator PCR@0.5. This is because directly generating all tokens from would inherit the fuzziness of global features in the final reconstruction results. Conversely, using a probabilistic generative model that relies only on already generated local structures rather than global features to complete incomplete regions can eliminate this fuzziness and produce higher-quality results.

4. Discussion

Qualitative experiments have shown that the reconstruction performance of VRC is generally superior to RfD-Net and comparable to DIMR. It is worth noting that, unlike DIMR, VRC does not require pairing information between instance point clouds and polygon mesh models during training. By completing the reconstruction in an unsupervised manner, VRC significantly reduces the need for data annotation, which is of great engineering significance.

For the quantitative comparative experiments, our VRC framework obtains results reaching the same level as RfD-Net and DIMR in reconstruction quality. As an unsupervised reconstruction method, VRC alleviates the annotation accuracy issues introduced by Scan2CAD, achieving high reconstruction fidelity and providing a solution to the data annotation challenges in reconstruction tasks.

Considering the ablation experiment, the sequential reconstruction in the VRC framework effectively utilizes existing structural information before generating the blank parks and reaching higher quality. The use of probability generation models avoids the ambiguity of global features in incomplete models, making the reconstruction results more accurate.

5. Conclusions

In this paper, we address challenges in point cloud scene semantic reconstruction, particularly the reliance on extensive paired training data and the limitations of Transformer-based autoregressive models in handling real scene point clouds. These challenges underline the need for improved frameworks capable of efficient and accurate completion reconstruction.

To tackle these issues, we propose the VRC unsupervised reconstruction framework, which leverages a Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) to map the features of proposal point clouds to the manifold distribution of complete point cloud features. This approach eliminates the need for paired data, significantly reducing the training data requirements.

Moreover, to enhance the completion process for real-world partial observations, we optimize the Transformer autoregressive inference model. By prioritizing the reconstruction of tokens with higher point densities, our method ensures efficient utilization of known structural information while mitigating completion ambiguity. Specifically, the reconstruction process begins with tokens in regions of high point density, completing missing parts in sequence based on the reconstructed known tokens.

The training loss function, model parameters, and experimental settings of VRC are then introduced. From the reconstruction results, it can be observed that the VRC algorithm successfully completes the semantic reconstruction task of point cloud scenes without paired information. The result of the ablation experiments also validates the effectiveness of the proposed method based on the order of point cloud quantities within tokens for derivation and masking global feature completion of unknown tokens.

This paper focuses on the semantic reconstruction of eight object categories in indoor point cloud scenes. To further advance this research, future efforts will explore datasets with richer annotation details to expand the semantic categories involved in scene reconstruction.

Additionally, while the proposed VRC framework theoretically possesses multimodal complementation capabilities, this study exclusively applies it to point cloud scene reconstruction. Future research will delve deeper into harnessing VRC’s potential for multimodal integration, enabling broader applications across diverse data modalities.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.M.; Methodology, Y.M. and S.X.; Software, Y.M. and T.Q.; Investigation, Y.M., S.X., T.Q. and J.W.; Resources, M.H.; Data curation, Y.M.; Writing—original draft, Y.M.; Writing—review and editing, Y.M., S.X. and T.Q.; Supervision, Y.M.; Project administration, Y.M.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32472005).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Roldão, L.; de Charette, R.; Verroust-Blondet, A. 3D Semantic Scene Completion: A Survey. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2022, 130, 1978–2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Chen, X.; Wang, J.; Zeng, G. Not All Voxels Are Equal: Semantic Scene Completion from the Point-Voxel Perspective. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 2022, 36, 2352–2360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Chen, X.; Zhang, C.; Lin, K.-Y.; Wang, X.; Li, H. Semantic Scene Completion via Integrating Instances and Scene In-the-Loop. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Nashville, TN, USA, 19–25 June 2021; pp. 324–333. [Google Scholar]

- Song, S.; Yu, F.; Zeng, A.; Chang, A.X.; Savva, M.; Funkhouser, T. Semantic Scene Completion From a Single Depth Image. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 1746–1754. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, L.; Zhao, H.; Shi, S.; Liu, S.; Fu, C.-W.; Jia, J. PointGroup: Dual-Set Point Grouping for 3D Instance Segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 4867–4876. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.; Fang, J.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, W.; Wang, X. Hierarchical Aggregation for 3D Instance Segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Montreal, QC, Canada, 10–17 October 2021; pp. 15467–15476. [Google Scholar]

- Vu, T.; Kim, K.; Luu, T.M.; Nguyen, T.; Yoo, C.D. SoftGroup for 3D Instance Segmentation on Point Clouds. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 2708–2717. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Chen, B.; Mitra, N.J. Unpaired Point Cloud Completion on Real Scans Using Adversarial Training. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Learning Representations, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 26–30 April 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Choe, J.; Joung, B.; Rameau, F.; Park, J.; Kweon, I.S. Deep Point Cloud Reconstruction. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2111.11704. [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, P.; Wen, X.; Liu, Y.-S.; Cao, Y.-P.; Wan, P.; Zheng, W.; Han, Z. SnowflakeNet: Point Cloud Completion by Snowflake Point Deconvolution With Skip-Transformer. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Montreal, BC, Canada, 11–17 October 2021; pp. 5499–5509. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, C.R.; Su, H.; Mo, K.; Guibas, L.J. PointNet: Deep Learning on Point Sets for 3D Classification and Segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 652–660. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, C.R.; Yi, L.; Su, H.; Guibas, L.J. PointNet++: Deep Hierarchical Feature Learning on Point Sets in a Metric Space. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017; Curran Associates, Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2017; Volume 30. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, W.; Khot, T.; Held, D.; Mertz, C.; Hebert, M. PCN: Point Completion Network. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference on 3D Vision (3DV), Verona, Italy, 5–8 September 2018; pp. 728–737. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, S.; Jiang, C.; Liao, Y.; Niemeyer, M.; Pollefeys, M.; Geiger, A. Shape As Points: A Differentiable Poisson Solver. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Curran Associates, Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2021; Volume 34, pp. 13032–13044. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, R.; Chen, X.; Zhuang, Y.; Chen, B. Multimodal Shape Completion via Conditional Generative Adversarial Networks. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2020; Vedaldi, A., Bischof, H., Brox, T., Frahm, J.-M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 281–296. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Chen, X.; Cai, Z.; Pan, L.; Zhao, H.; Yi, S.; Yeo, C.K.; Dai, B.; Loy, C.C. Unsupervised 3D Shape Completion Through GAN Inversion. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 1768–1777. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; Kim, V.G.; Fisher, M.; Aigerman, N.; Zhang, H.; Chaudhuri, S. DECOR-GAN: 3D Shape Detailization by Conditional Refinement. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 15740–15749. [Google Scholar]

- Goodfellow, I.; Pouget-Abadie, J.; Mirza, M.; Xu, B.; Warde-Farley, D.; Ozair, S.; Courville, A.; Bengio, Y. Generative Adversarial Networks. Commun. ACM 2020, 63, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Lin, L.; Mitra, N.J.; Lischinski, D.; Cohen-Or, D.; Huang, H. ShapeFormer: Transformer-Based Shape Completion via Sparse Representation. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 6239–6249. [Google Scholar]

- Mittal, P.; Cheng, Y.-C.; Singh, M.; Tulsiani, S. AutoSDF: Shape Priors for 3D Completion, Reconstruction and Generation. In Proceedings of the AutoSDF: Shape Priors for 3D Completion, Reconstruction and Generation, New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 306–315. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, X.; Rao, Y.; Wang, Z.; Lu, J.; Zhou, J. AdaPoinTr: Diverse Point Cloud Completion with Adaptive Geometry-Aware Transformers. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2301.04545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, S.; Niemeyer, M.; Mescheder, L.; Pollefeys, M.; Geiger, A. Convolutional Occupancy Networks. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2020; Vedaldi, A., Bischof, H., Brox, T., Frahm, J.-M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 523–540. [Google Scholar]

- Avetisyan, A.; Dahnert, M.; Dai, A.; Savva, M.; Chang, A.X.; Niessner, M. Scan2CAD: Learning CAD Model Alignment in RGB-D Scans. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 2614–2623. [Google Scholar]

- Nie, Y.; Hou, J.; Han, X.; Niessner, M. RfD-Net: Point Scene Understanding by Semantic Instance Reconstruction. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 4608–4618. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, J.; Chen, X.; Wang, J.; Zeng, G. Point Scene Understanding via Disentangled Instance Mesh Reconstruction. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2022; Avidan, S., Brostow, G., Cissé, M., Farinella, G.M., Hassner, T., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 684–701. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; Zhang, H. Neural Marching Cubes. ACM Trans. Graph. 2021, 40, 251:1–251:15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Tagliasacchi, A.; Funkhouser, T.; Zhang, H. Neural Dual Contouring. ACM Trans. Graph. 2022, 41, 104:1–104:13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Oord, A.; Vinyals, O.; Kavukcuoglu, K. Neural Discrete Representation Learning. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Curran Associates, Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2017; Volume 30. [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar, K.; Varanasi, K.; Stricker, D. Learning Quadrangulated Patches for 3D Shape Parameterization and Completion. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Conference on 3D Vision (3DV), Qingdao, China, 10–12 October 2017; pp. 383–392. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, D.T.; Hua, B.-S.; Tran, K.; Pham, Q.-H.; Yeung, S.-K. A Field Model for Repairing 3D Shapes. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 5676–5684. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, M.; Tagliasacchi, A.; Seversky, L.M.; Alliez, P.; Levine, J.A.; Sharf, A.; Silva, C.T. State of the Art in Surface Reconstruction from Point Clouds. In Proceedings of the 35th Annual Conference of the European Association for Computer Graphics, Eurographics 2014-State of the Art Reports, Strasbourg, France, 7–11 April 2014; The Eurographics Association: Eindhoven, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, Q.; Lai, Y.-K.; Wu, J.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, K.; Wang, J. MLCVNet: Multi-Level Context VoteNet for 3D Object Detection. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 10447–10456. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, C.R.; Litany, O.; He, K.; Guibas, L.J. Deep Hough Voting for 3D Object Detection in Point Clouds. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 9277–9286. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, B.; Engelcke, M.; van der Maaten, L. 3D Semantic Segmentation with Submanifold Sparse Convolutional Networks. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 9224–9232. [Google Scholar]

- Taud, H.; Mas, J.F. Multilayer Perceptron (MLP). In Geomatic Approaches for Modeling Land Change Scenarios; Camacho Olmedo, M.T., Paegelow, M., Mas, J.-F., Escobar, F., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 451–455. ISBN 978-3-319-60801-3. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, H.; Su, H.; Guibas, L. A Point Set Generation Network for 3D Object Reconstruction from a Single Image. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, X.; Li, Q.; Xie, H.; Lau, R.Y.K.; Wang, Z.; Paul Smolley, S. Least Squares Generative Adversarial Networks. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 2794–2802. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, M. Softmax GAN. arXiv 2020, arXiv:1704.06191v2. [Google Scholar]

- Park, J.J.; Florence, P.; Straub, J.; Newcombe, R.; Lovegrove, S. DeepSDF: Learning Continuous Signed Distance Functions for Shape Representation. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 165–174. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, A.; Chang, A.X.; Savva, M.; Halber, M.; Funkhouser, T.; Niessner, M. ScanNet: Richly-Annotated 3D Reconstructions of Indoor Scenes. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 5828–5839. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, A.X.; Funkhouser, T.; Guibas, L.; Hanrahan, P.; Huang, Q.; Li, Z.; Savarese, S.; Savva, M.; Song, S.; Su, H.; et al. ShapeNet: An Information-Rich 3D Model Repository. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1512.03012. [Google Scholar]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention Is All You Need. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Curran Associates, Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2017; Volume 30. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).