Abstract

Code search uses natural language queries to retrieve code snippets from a vast database, identifying those that are semantically similar to the query. This enables developers to reuse code and enhance software development efficiency. Most existing code search algorithms focus on capturing semantic and structural features by learning from both text and code graph structures. However, these algorithms often struggle to capture deeper semantic and structural features within these sources, leading to lower accuracy in code search results. To address this issue, this paper proposes a novel semantics-enhanced neural code search algorithm called SENCS, which employs graph serialization and a two-stage attention mechanism. First, the code program dependency graph is transformed into a unique serialized encoding, and a bidirectional long short-term memory (LSTM) model is used to learn the structural information of the code in the graph sequence to generate code vectors rich in structural features. Second, a two-stage attention mechanism enhances the embedded vectors by assigning different weight information to various code features during the code feature fusion phase, capturing significant feature information from different code feature sequences, resulting in code vectors rich in semantic and structural information. To validate the performance of the proposed code search algorithm, extensive experiments were conducted on two widely used code search datasets, CodeSearchNet and JavaNet. The experimental results show that the proposed SENCS algorithm improves the average code search accuracy metrics by 8.30 % (MRR) and 17.85% (DCG) and compared to the best baseline code search model in the literature, with an average improvement of 14.86% in the SR@1 metric. Experiments with two open-source datasets demonstrate SENCS achieves a better search effect than state of-the-art models.

1. Introduction

With the continuous advancement of internet technology, the demand for software and its functionalities has increased, pushing developers to invest significant time and effort in software development and project design [1,2,3]. To satisfy complex programming requirements, developers often use natural language to describe the functionality they need and to search for similar code online. The growth of open-source communities and online Q&A platforms has led to a massive increase in available project code, providing rich data for developers to find high-quality code snippets aligned with their queries [4,5].

Code search refers to the process where a code search algorithm retrieves code snippets that are semantically similar to a user’s natural language query from a vast codebase [2,3]. Traditional code search methods treat source code as plain text, comparing it directly with the natural language query. However, this approach often yields low accuracy due to the complexity of natural language. In response, researchers have introduced information retrieval and heuristic-based methods, but these approaches fail to capture the deep semantic connections between natural language and code, leading to a significant semantic gap.

With the rise of deep learning (DL) in natural language processing (NLP), researchers have developed DL-based code search techniques to better understand code semantics and improve search performance. For example, DeepCS [6], NCS [7], GraphCS [8], GSMM [9], QueCos [10], etc. With the further development and application of pre-trained models in the field of NLP, researchers are also considering using pre-trained methods to enhance the performance of code search tasks, such as CodeBERT [11], GraphCodeBERT [12], and the CDCS [13] algorithm. Currently, most DL algorithms utilize Graph Neural Network (GNN) models to learn structural feature information from code, but they often fail to capture the deep structural information within code, resulting in lower search accuracy. As the demand for efficient and accurate code search grows, there is a need to develop algorithms that not only provide accurate results but also execute searches efficiently.

In this context, this paper proposes a code search algorithm that incorporates semantic enhancement. The proposed algorithm uses graph serialization and a two-stage attention mechanism to improve code search accuracy. The proposed algorithm considers three types of feature information: code method names, character tagging sequences, and program dependency graph serialization. To capture deep semantic and structural information, a two-stage attention mechanism is introduced to enhance feature representation and combine multiple feature vectors into enriched code vectors. The program dependency graph is transformed into a unique serialized sequence, ensuring that the structural information is fully embedded, which significantly improves search accuracy. The key contributions of this paper are as follows:

(1) In this paper, we propose SENCS, a deep semantic-enhanced neural code search algorithm based on graph serialization and a two-stage attention mechanism. We provide semantic features to code vectors by extracting code method name features and character markup features; generate serialized encodings by extracting program dependency graph structural features of the code; and further learn the graph sequence features to provide structural features to code vectors.

(2) In the enhancement phase of the two-stage mechanism, we use multi-head attention to enhance the features of the embedding vector and the features in the fusion phase. We use the multi-head attention mechanism to assign different weights to the different code features to generate enriched code feature vectors with enhanced semantic features and enhanced structural features.

(3) Extensive experiments were conducted using both the CodeSearchNet dataset and JavaNet dataset, comparing SENCS to several baseline models. The results show that SENCS improved search accuracy metrics by an average of 9.70% compared to the best baseline model. In particular, the SR@1 metric shows an improvement of 14.86%. For the number of most relevant code snippets that return top-ranked position code fragments, the SENCS algorithm in this paper has more than the number for comparable algorithms.

The structure of this paper is as follows: Section 1 provides an introduction, covering the research background and the significance of code search. Section 2 reviews related work in the field. Section 3 discusses the SENCS algorithm, including code semantic features enhancement and code graph sequence features enhancement. Section 4 presents the experiments and results, and Section 5 concludes the paper with a summary.

2. Related Works

In the early stages of code search research, most algorithms treated source code snippets and natural language descriptions as mere text, relying on text similarity comparisons for code retrieval. However, these approaches yielded relatively low accuracy in search results. To enhance this, researchers integrated information retrieval techniques like TF-IDF [14] and BM25 [15] to improve accuracy. For instance, Lv et al. [16] proposed a code search algorithm using extended Boolean logic to enhance the semantics of natural language queries by identifying relevant API information, thereby increasing code search accuracy. Li et al. [17] introduced RACS, a JavaScript code search method that transforms the search problem into a graph search issue, utilizing approximate graph matching. Zhang et al. [18] considered API-related information during semantic enhancement of queries, while Raghothaman et al. [19] developed SWIN, a tool that synthesizes code snippets by analyzing the correlation between natural language queries and API information. Additionally, heuristic-based methods have emerged, such as Kam1n0, introduced by Ding et al. [20], which searches assembly functions in large datasets by transforming code search into a query subgraph and assembly code subgraph matching problem. However, both information retrieval and heuristic-based approaches struggle to capture deeper semantic relationships between source code and natural language queries, leaving a significant semantic gap and resulting in low search accuracy.

As DL technology has evolved in NLP, researchers have begun to apply these methods to code search tasks to enhance performance. Gu et al. [6] proposed DeepCS, a DL-based model that employs neural networks to learn feature information from source code, calculating cosine similarity between code fragment vectors and natural language description vectors to determine semantic similarity. Sachdev et al. [21] introduced NCS, a neural source code retrieval algorithm that maps semantically similar source codes and queries to close vector points using a supervision layer, combined with a rule-based ranking method to address scattered search results. Liu et al. [7] improved NCS with the NQE model, which enriches query statements through automatic keyword expansion. Huang et al. [8] developed GraphCS, which uses Graph2Vec to extract structural features from code graphs, generating rich feature vectors for code. Liu et al. created a character-level information flow graph from code AST nodes and tokens to capture both structural and semantic features. Shi et al. [9]. introduced GSMM, a graph serialization-based model that transforms program dependency graphs into sequences and uses a bidirectional LSTM model to learn structural feature information. The MSR algorithm [22] offers a multi-level semantic analysis of code text to capture potential semantic features, resulting in vector representations for code snippets and natural language descriptions. Wang et al. [10]. proposed QueCos, a model leveraging reinforcement learning to generate semantically rich query statements for code search tasks.

With the rise of pre-trained models in NLP, researchers are exploring their applications in code search. Feng et al. [3] introduced CodeBERT, a pre-trained model designed for code representation tasks such as search and generation. Guo et al. [12] expanded this with GraphCodeBERT, which incorporates unique structural information by learning data flow graphs in code to capture contextual information about various variables. Furthermore, Salza et al. [23] presented a code search algorithm utilizing transfer learning, demonstrating effectiveness with substantial pre-trained data. The CDCS algorithm [13] applies cross-domain code search through small-sample meta-learning, modifying the MAML meta-learning algorithm to fine-tune parameters of pre-trained models in mainstream languages like Java, thereby enhancing code search performance for less common programming languages.

The DL-based code search model consists of two main stages: vector embedding and query processing. In the vector embedding stage, various features of code snippets are learned to ensure that the resulting code vectors represent both the semantic and structural richness of the source code. Geng et al. [24] proposed the COSER method, which converts source code into semantic graphs and leverages pre-trained language models to encode it as vector representations, enabling similarity calculations across different programming languages. Zhang et al. [25] introduced abstract code embedding (AbCE), a self-supervised learning method that incorporates abstract semantics reflecting code logic. AbCE treats entire nodes or sub-trees within an abstract syntax tree (AST) as fundamental code units during pre-training, rather than dispersed tokens, thereby preserving complete encoding units. Vallejo-Huanga et al. [26] proposed SimilaCode, an efficient system for detecting similarities in programming source codes, particularly in Python, utilizing NLP, vector space models, and similarity metrics, achieving 100% accuracy in identifying unaltered code and over 88% accuracy even after significant modifications. The CSRG [27] approach proposed a novel code representation structure to jointly represent AST nodes and code data flow, thereby focusing on semantic information. Saieva [28] presented an innovative code-to-code search technique that enhances the performance of large language models (LLMs) by incorporating both static and dynamic features and using both similar and diverse examples during training. However, current methods that extract semantic features, such as method names, character tags, API sequences, and graph structures like control flow and program dependency graphs, fail to capture the deeper layers of control flow and data flow structures. This limitation leads to lower accuracy in search results.

3. Deep Semantic-Enhanced Neural Code Search

To improve the accuracy of code search, this paper proposes a deep semantic-enhanced neural code search algorithm (SENCS) based on graph serialization and a two-stage attention mechanism. This algorithm fully considers three kinds of feature information when embedding code fragments into vector representations: code method name, character token sequence, and program-dependent graph serialization. Furthermore, to learn the deeper semantic features and structural information in code, this paper enhances the representation of feature vectors and fuses multiple feature vectors through a two-stage attention mechanism, obtaining code vectors rich in features and a unique sequence encoding representation containing graph structure information, to capture code structure features at a deeper level and improve the accuracy of code search. The proposed framework is elaborated in the following sections.

3.1. Semantic-Enhanced Neural Code Search (SENCS) Framework

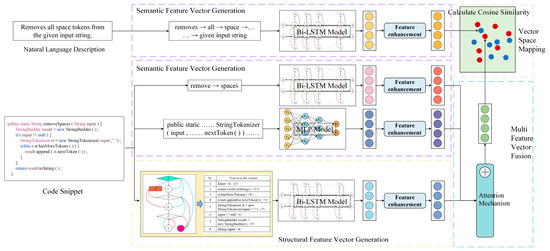

Programming languages contain rich semantic and structural feature information. To comprehensively learn the feature information of code fragments and natural language descriptions, effectively capture the semantic and structural features within the code, and generate robust code vector representations, this paper proposes the SENCS algorithm, which is based on deep semantic-enhanced neural code search. The SENCS algorithm is structured into four key stages: semantic feature vector generation, structural feature vector generation, multi-feature vector fusion, and vector space mapping. The overall framework of the SENCS algorithm is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Overall framework of SENCS algorithm.

From Figure 1, we can see that in the semantic feature vector generation phase, the text structure information is processed and learned to obtain the embedded vector representation of the feature information, and the embedded vectors are feature enhanced using the attention mechanism. In the structural feature vector generation phase, serialized encoding is generated by extracting the code program dependency graph structure, and structural feature enhancement is performed on the embedding vectors using the attention mechanism. Feature enhancement of feature vectors is performed in the semantic and structural feature vector generation phases using the multi-head attention mechanism to consider the weight information between different parts within the feature, as well as in the multi-feature vector fusion phase using the multi-head attention mechanism to learn the weight information of different code features and to fuse multiple code features. Finally, in the vector space mapping stage, code vectors and natural language description vectors are mapped to the same dimension vector space, and their cosine similarity is calculated. If the cosine similarity between code vectors and natural language description vectors is high, it means that the source code fragment and the natural language description are semantically similar, while if the cosine similarity is low, it means that the source code fragment and the natural language description are semantically different.

3.2. Semantic Feature Vector Generation and Enhanced Representation

Code snippets contain rich code semantic feature information, such as code feature information in code snippet method names, code feature information in character token information, and feature information in natural language descriptions. The effective extraction of this information can generate code feature vectors and description feature vectors with rich semantic information. The following sections explain the semantic code feature extraction and enhanced representation processes.

3.2.1. Code Semantic Features Extraction

The program code consists of one or more variables and operations performed on those variables, with the data source and subsequent output of the variables closely linked to their contextual information. In this paper, we obtain the semantic features of code by learning from code snippet method name and character tagging information, as well as code comment information.

(1) Code Method Name Sequence Feature Extraction

Code method names are typically composed of descriptive and meaningful words. Given that method name sequences are usually short and consist of only a few words, the order of these words is critical. Recurrent neural networks (RNN) and long short-term memory (LSTM) architectures can learn complex temporal information from text sequences and extract rich semantic relationships. The bidirectional LSTM (Bi-LSTM) model is a specialized RNN structure that simultaneously learns information in sequences from both forward and backward directions, addressing the limitation of standard RNNs and LSTMs in capturing contextual information of words in sequences.

When processing the sequence of method names in code snippets, a Bi-LSTM model is employed to capture the semantic feature information and generate a corresponding feature vector representation. Let the length of the method name sequence be Nm, represented as . The Bi-LSTM model learns the semantic features from the method name information and generates the feature vector methnaVec, as shown in Formulas (1)–(3).

In Formulas (1) and (2), represents the embedding vector of the t-th word in the method name sequence. and represent the hidden state vector at time step in the forward and backward LSTM extractors, respectively, for the method name sequence. and refer to the bidirectional LSTM architecture and its associated parameters. A max-pooling technique is applied to extract the most relevant feature information from the method name sequence, generating the final feature vector for the method name.

(2) Character Token Sequence Feature Extraction

A character token provides a sequence representation of method-level code that encapsulates rich feature information. To learn the character tagging vector representation using a Bi-LSTM model, calculations must be performed at each time step. Given the typically long character tagging sequences, this calculation process can become relatively complex. A multi-layer perceptron (MLP) model, however, is well-suited for capturing nonlinear relationships in structured data, and code languages often exhibit strong local characteristics in their structures. Therefore, our approach utilizes a multi-layer perceptron model to learn the vector representation of code character tags, effectively capturing the complex relationships and patterns between character tags, and further extracting deep semantic feature information.

For the processing of code character tagging sequences, an MLP model is employed to learn the information embedded in the character tags. The length of the character tag sequence for the code fragment is denoted as , and the sequence is represented as . The feature vector of the character tag sequence is denoted as . The process of learning feature information from the code character tags using the MLP model to obtain the character tag feature vector is described in Formulas (4) and (5).

In this context, represents the vector representation of the t-th character tag in the character tag sequence, and is the hidden layer vector representation for the t-th word in the sequence. denotes the training parameters related to full connectivity in the multi-layer perceptron. The method is employed to select the relevant character tag feature information, generating the feature vector for the character tag sequence.

(3) Natural Language Annotation Features

Code annotation is a conceptual language based on natural language that describes the functionality of code. When a code annotation is embedded as a vector, the contextual relationship of its text sequence is very important and essential. To effectively process natural language descriptions of code, a Bi-LSTM model can be employed to learn contextual information from both forward and backward directions. This approach enhances the ability to capture the feature information embedded in each word’s hidden layer within the natural language description sequence. Assuming a natural language description denoted as with a length of , the Bi-LSTM model captures and learns the feature information in the natural language description to generate the feature vector , as illustrated in Formulas (6)–(8).

where represents the vector corresponding to the t-th word in the natural language description. The vectors and denote the hidden layer state representations at time t in the forward and backward LSTM components, respectively. The models and refer to the Bi-LSTM architecture and its associated parameters. The method is employed to extract feature information from the natural language description, ultimately generating the final feature vector .

3.2.2. Code Semantic Features Enhancement

To create more comprehensive and richer feature vectors for both code method names and character tags, our proposed method utilizes a multi-head attention mechanism. In this paper, we use a multi-head attention mechanism to learn the complex semantic relationships within method name sequences and between different parts of character tag sequences and natural language annotations to realize semantic enhancement of method name feature vectors, character tag feature vectors, and natural language description feature vectors.

(1) Method Name Feature Representation Enhancement

By employing a multi-head attention mechanism, the algorithm captures the semantic feature information of code method names more effectively. It learns the weight information among various elements within the method name sequence, resulting in a vector representation that possesses rich semantic features. The implementation process for enhancing the method name vector features is outlined in Formulas (9)–(13).

The vectors , and are input vectors for the multi-head attention mechanism, derived from the linearly transformed method name feature embedding vector . In this mechanism, these vectors are segmented into multiple-head vectors, allowing the attention mechanism to process the information from each segment and produce the method name head vector. Specifically, the head vector is calculated by evaluating the attention score using and , in the i-th head, followed by weighting . The processed head vectors from all segments are then merged and linearly transformed to create the enhanced semantic representation of the method name feature vector . In this context, , , , and represent the parameter weight matrices for the attention processing, while, , and are the corresponding bias terms. The variable indicates the number of heads. The overall process for generating and enhancing the feature vectors of the code method name sequence is illustrated in Figure 2.

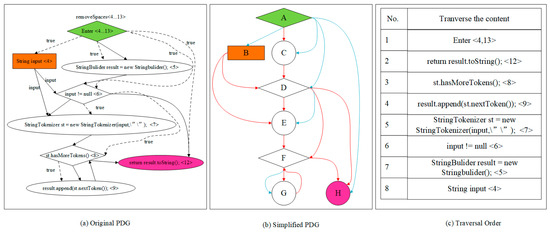

Figure 2.

Example of dependency graph serialization for remove Spaces function program.

(2) Enhancement of Character Tag Feature Representation

The implementation process for enhancing the character tag feature representation is also outlined in Formulas (14)–(18). But here, the vectors , and serve as input vectors for the multi-head attention mechanism, obtained by linearly transforming the character tag feature embedding vector . Similar to the method name vectors, these are segmented into multiple-head vectors, and the attention mechanism processes the information of each segment to generate the character tag head vector. The head vector is derived by calculating the attention score using and in the i-th head, weighted by . Finally, the head vectors from all segments are merged and linearly transformed to produce the enhanced semantic representation of the character tag feature vector .

(3) Natural Language Annotation Feature Representation Enhancement.

The process of enhancing the feature representation of natural language descriptions is outlined in Formulas (19)–(23). Here, the vectors , and serve as input vectors for the multi-head attention mechanism, derived from the feature embedding vector through linear transformation. Within the multi-head attention mechanism, these vectors are segmented into multiple-head vectors, allowing the attention mechanism to process the information of each segment and produce a descriptive head vector. The head vector is obtained by calculating the attention scores using and in the i-th head and applying weights to . The head vectors from all attention heads are then merged and linearly transformed to yield the enhanced semantic representation vector .

3.2.3. Graph Sequence Features Generation

The code language exhibits a high degree of structure and contains rich structural feature information. We aim to learn the feature information embedded in the dependency graph sequence of the code program, ensuring that the code vector representation captures comprehensive structural features.

The code program dependency graph contains rich data dependency information and control dependency information, and there has been related work on generating graph feature vectors based on deep learning techniques [29]. However, these techniques are not very effective. This is because the graph traversal order and the choice of the initial node as well as the multiple neighborhoods of the currently accessed node will lead to a traversal of the sequence of node paths that is not unique, which causes the loss of the original graph structure features.

To ensure the uniqueness of the graph sequence and to deeply capture the complex structural information within the graph, the proposed SENCS algorithm employs a graph traversal method with specified edge priorities. This approach prioritizes control-dependent and data-dependent edge information during traversal. Specifically, based on the depth-first traversal technique, the program dependency graph is traversed to generate a graph sequence encoding that maintains the structural information and semantic meaning of the source code.

To illustrate the effectiveness of the graph-to-sequence algorithm, consider the removeSpaces function as an example. Figure 2 demonstrates the process of traversing the graph structure. Figure 2a presents the program dependency graph of the removeSpaces function. To simplify the visualization of data and control dependencies, node and edge information is condensed, with blue solid lines indicating control-dependent edges, red solid lines representing data-dependent edges and A–H represents statement nodes, as shown in Figure 2b. By applying the described graph serialization method to traverse the simplified program dependency graph and incorporating label information from the source code, we obtain the graph structure serialization representation for the removeSpaces function. Figure 2c illustrates the order of node traversal based on the specified edge-first traversal rules. After outputting this order, the corresponding serialization encoding for the program dependency graph is produced. This method allows for the deep capture of complex structural features in program dependencies, enhancing the comprehensiveness of graph sequence feature representations and the robustness of graph serialization models.

To enhance both the semantic and structural representation of graph sequence feature vectors, the proposed SENCS algorithm employs a multi-head attention mechanism. This mechanism processes the generated graph sequence feature embedding vectors, learns the weight information across different parts of the vectors, and produces program-dependent graph sequence feature vectors with enriched semantic representations.

Upon serialization of the code program dependency graph structure, a sequence representation is obtained that encapsulates the rich structural features of the code. This graph structure sequence includes control and data dependency information between nodes, along with contextual information. To effectively learn the structural information in this sequence and generate a robust graph structure sequence feature vector representation, the proposed SENCS algorithm utilizes a Bi-LSTM model. This model learns from both the forward and backward directions of the sequence, capturing hidden state information at each moment and generating a program dependency graph vector rich in semantic and structural features. The length of the program dependency graph sequence for the code snippet is denoted as , represented as . The resultant graph structure vector is denoted as. The process of utilizing a Bi-LSTM model to learn the feature information from the code program dependency graph structure sequence to obtain the feature vector is illustrated in Formulas (24)–(26).

where represents the embedding vector corresponding to the t-th element in the program dependency graph sequence of the code fragment. The vectors and denote the hidden layer state vector representations at time t in the forward and backward LSTM extractors of the code method name sequence, respectively. and refer to the Bi-LSTM architecture and its related parameters. The method is employed to select the relevant feature information from the code program dependency graph sequence, generating the final feature vector for the code fragment.

3.2.4. Graph Sequence Features Enhancement

To create a more comprehensive program dependency graph feature vector that effectively expresses the structural information of the source code, our proposed method employs a multi-head attention mechanism. This mechanism focuses on different positions within the graph feature vector, allowing for finer capture of feature correlation information from various parts of the vector. By doing so, it better elucidates the complex dependency relationships inherent in the program dependency graph vector, thereby enhancing its representation. The implementation process for this enhancement of the program dependency graph feature representation is detailed in Formulas (27)–(31).

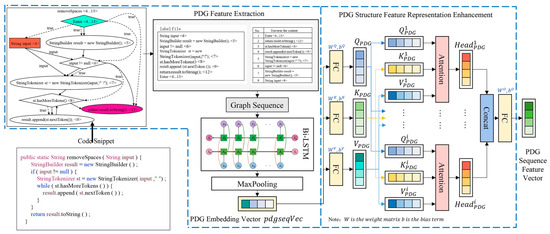

where the , , and vectors are input vectors for the multi-head attention mechanism, derived from linearly transforming the feature embedding vector in the program dependency graph serialization. In the multi-head attention mechanism, these vectors are segmented into multiple-head vectors. The attention mechanism processes the information from each head, resulting in the graph sequence head vector. The program dependency graph sequence head vector is obtained by calculating the attention score using and in the i-th head, with the corresponding weighted accordingly. The head vectors, processed by the attention mechanism across all heads, are then merged and linearly transformed to produce the enhanced graph sequence feature vector with the enriched semantic representation vector . The code program relies on the sequence structure of the diagram to generate feature vectors and facilitate feature enhancement, as illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Process of program dependence graph structure feature vector generation.

3.3. Feature Vector Fusion and Spatial Mapping

The proposed SENCS algorithm employs a two-stage attention mechanism to process code feature vectors, aiming to achieve more comprehensive semantic representations. In the first stage, the attention mechanism focuses on extracting semantic and structural feature vectors, enhancing various code feature vectors and natural language description vectors. The second stage utilizes another attention mechanism for multi-feature vector fusion, capturing deeper insights into code features and generating richly detailed code vector representations.

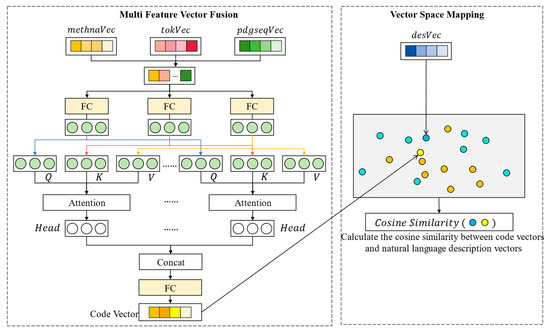

The proposed SENCS algorithm fuses various source code feature vectors to generate code fragment vectors, and maps the fused code fragment vectors and natural language description feature vectors to the vector space, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Multi-feature vector fusion and feature space mapping process.

In the multi-feature fusion stage, the code method name semantic feature vector, character tag semantic feature vector, and program dependency graph sequence structure feature vector are processed into a unified code synthesis vector representation. For instance, in our proposed algorithm, the code feature vector has a dimension of [64, 512], while the synthesis vector dimension is [64, 3, 512], where 3 represents the number of features. To effectively capture the rich semantic and structural information across the generated code vectors, the algorithm employs a multi-head attention mechanism. This mechanism learns the weight information between the three distinct code feature vectors from multiple perspectives and uses this information to weight the code feature vectors, yielding the final code vector representation.

In the spatial mapping stage, to calculate the similarity between the code vector and the natural language description vector, both are mapped into the same high-dimensional vector space with identical dimensions. The cosine similarity is computed as a measure of similarity; a larger cosine similarity indicates that the vectors are closer in the vector space. The calculation process is detailed in Formula (32).

During the training phase of the code search algorithm model, for more accurate results, it is essential to continually compute the similarity between code fragment vectors and their corresponding natural language description vectors in the training dataset and calculate the loss function. This loss function is utilized to optimize the code search model, ensuring that code fragments with similar semantic expressions are closer to their corresponding natural language descriptions in the vector space, while those with significant semantic differences are positioned further apart.

Throughout the training process, it is necessary to extract both the correct and incorrect natural language descriptions for each code fragment. The incorrect descriptions are randomly selected from a dataset distinct from the correct descriptions. Let represent the vector set of the code fragment, represent the correct natural language description vector, and represent the collection of incorrect natural language descriptions. Pairs formed by and create positive sample data for training, while and form negative sample data pairs. The optimization objective of this model is to maximize the cosine similarity between the code and the correct natural language description while minimizing the cosine similarity between the code and the incorrect descriptions. This approach enables the model to better learn the vector representations of the code and its associated natural language description data pairs. The process for calculating the loss function is outlined in Formula (33).

represents the training set consisting of code and natural language pairs. The variable denotes the code fragment vector, indicates the correct natural language description vector corresponding to the code fragment, and refers to the incorrect natural language description vector. The function is used to compute the cosine similarity between two vectors.

4. Experimental Evaluation

To assess the code search performance of the proposed SENCS algorithm, this section presents a comparative experiment focused on analyzing accuracy and effectiveness. A two-stage attention mechanism impact experiment was designed to evaluate the effect of this mechanism on algorithm performance. Additionally, an ablation study was conducted to assess the influence of various code features on the algorithm’s performance. This section also includes parameter sensitivity analysis experiments to investigate the impact of different code feature lengths and feature vector dimensions on algorithm performance.

4.1. Introduction to Experimental Dataset and Experimental Environment

The experiments were conducted using two cutting-edge datasets, namely CodeSearchNet and JavaNet, to evaluate the proposed algorithm’s code search performance. The CodeSearchNet dataset is a well-known resource for code search research [30], jointly released by Microsoft and GitHub in 2019. The JavaNet dataset consists of Java code snippets and their corresponding natural language descriptions, gathered from open-source networks using web crawling algorithms [9]. The partitioning details for both the CodeSearchNet and JavaNet datasets are presented in Table 1. Table 2 provides detailed information about the experimental environment.

Table 1.

Information of datasets after preprocessing.

Table 2.

Description of the experimental environment.

4.2. Evaluation Indicators and Baseline Models

To better evaluate the performance of code search tasks and verify the effectiveness of proposed SENCS algorithm, three accuracy metrics, mean reciprocal rank (MRR) and SuccessRate@K, and discounted cumulative gain (DCG) were used in the experiments.

In Formula (34), refers to the position where the best code snippet that meets the query semantics first appears in the list of returned results after executing the code search. The smaller the value of , the higher the position of the results that meet the query requirements in the returned result list. Conversely, the lower the value, the lower the position of the results that meet the query requirements. SuccessRate@K (abbreviated as SR@K) is an important evaluation metric for assessing the performance of code search. SR@K is the probability that the first code search results returned have code snippets that are semantically similar to the natural language query. The smaller the value, the lower the accuracy of the code search, and the higher the value, the higher the accuracy of the code search. The calculation process is shown in Formula (34).

In the above Formula (34), represents the number of queries in the set Q of natural language query statements, represents a query statement in the set Q of query statements, represents the Frank value corresponding to the statement, and is the discriminant function in the formula. When the discriminant statement in the function is true, the return result is 1, and when the discriminant statement in the function is false, the return result is 0.

Mean reciprocal rank (MRR) is an internationally recognized metric for evaluating code search tasks. MRR is calculated by averaging the sum of the reciprocals of Frank values for natural language queries, representing the position of code fragments related to query semantics in the return result list. For a natural language query, when conducting a code search, the algorithm usually prioritizes displaying code fragments with high rankings to the user. That is, the higher the MRR value, the higher the ranking of code related to the query semantics, and the higher the search accuracy of the code search algorithm. The smaller the MRR value, the lower the ranking of code related to the query semantics, and the lower the search accuracy of the code search algorithm. The MRR calculation process is shown in Formula (35).

In Formula (35), represents the number of queries in the set Q of natural language query statements, represents a query statement in the set Q of query statements, and represents the value corresponding to the query statement.

Discounted cumulative gain (DCG) is a widely recognized metric for evaluating the quality of ranked lists in information retrieval and recommendation systems. Unlike mean reciprocal rank (MRR), which primarily focuses on the highest rank of the first relevant item, DCG considers the relevance of all items in the ranked list, with higher ranks receiving more weight. This makes DCG a comprehensive measure that evaluates the overall quality of the entire result list. For the case of the only correct answer, the calculation formula for DCG can be simplified as Formula (36).

In Formula (36), is the correlation score for the i-th result (1 for correct answer, 0 for incorrect answer), and is the first k results considered.

To better evaluate the code search performance of the SENCS algorithm, we selected the DeepCS model, MMAN model, and GSMM model as baseline comparison code search models. All three models are code search models based on multimodal feature extraction.

During the experiment, the code search dataset was randomly shuffled to obtain pairs of code fragments and natural language descriptions, with a batch size set to 64. The corresponding feature vector lengths for extracting various code feature information, natural language description feature information, and natural language query information were specified, as detailed in Table 3. To prevent parameter overfitting during the experimental process, a Dropout mechanism was introduced, with the Dropout value set to 0.25. A more detailed description of the experimental parameters for the SENCS algorithm is provided in Table 3.

Table 3.

Experimental parameter description.

The SENCS algorithm was applied to perform code search tasks on both the CodeSearchNet and JavaNet datasets, measuring SR@K (SR@1, SR@5, SR@10) to validate the accuracy of the code search results. Additionally, MRR evaluation metrics were used to validate the effectiveness of the code search results returned by the SENCS algorithm, utilizing the Frank evaluation metrics for further assessment.

4.3. Experimental Results

4.3.1. Comparison of Accuracy of Code Search Results

In Table 4, the code search performance of the proposed SENCS algorithm and the three baseline models on the CodeSearchNet dataset is presented. The experimental results indicate that the SENCS algorithm achieved an MRR value of 0.510, with SR@1, SR@5, and SR@10 values of 0.393, 0.646, and 0.736, respectively, with a DCG value of 0.559. Compared to the DeepCS algorithm, the SENCS algorithm improved MRR by 44.06%, with increases of 43.43%, 40.13%, and 37.57% in SR@1, SR@5, and SR@10, respectively, with DCG increases of 40.8%. When compared to the MMAN algorithm, the SENCS algorithm showed an MRR improvement of 18.60%, with SR@1, SR@5, and SR@10 increases of 28.85%, 14.94%, and 2.125%, respectively, with DCG increases of 23.1%. In comparison with the GSMM algorithm, the SENCS algorithm improved MRR by 7.36%, with SR@1, SR@5, and SR@10 increases of 14.91%, 10.05%, and 18.13%, respectively, with DCG increases of 11.1%.

Table 4.

Code search accuracy of SENCS algorithm on CodeSearchNet dataset.

Table 5 demonstrates the code search performance of the SENCS algorithm and the baseline models on the JavaNet dataset. The results indicate that the SENCS algorithm achieved an MRR value of 0.686, with SR@1, SR@5, and SR@10 values of 0.581, 0.814, and 0.877, respectively with a DCG value of 0.729. This represents a 65.30% improvement in MRR compared to the DeepCS algorithm, with SR@1, SR@5, and SR@10 increases of 71.38%, 63.45%, and 40.77%, respectively, with DCG increases of 53.8%. Compared to the MMAN algorithm, the SENCS algorithm showed a 35.84% improvement in MRR, with SR@1, SR@5, and SR@10 increases of 38.33%, 37.50%, and 11.71%, respectively, with DCG increases of 24.6%. When compared to the GSMM algorithm, there was a 9.23% improvement in MRR, with SR@1, SR@5, and SR@10 increases of 14.82%, 1.36%, and 1.74%, respectively, with DCG increases of 24.6%.

Table 5.

Code search accuracy of SENCS algorithm on JavaNet dataset.

From these results, it is evident that the SENCS algorithm improves the accuracy of code search by an average of 9.70% compared to the optimal baseline model, GSMM, across both datasets, with an average improvement of 14.86% in SR@1. The experiment with two open-source datasets shows SENCS achieves a superior search effect compared to SOTA models. The SENCS algorithm leverages graph serialization and a two-stage attention mechanism, capturing not only the semantic information of the code but also rich structural information. By combining these elements, the algorithm enhances code feature vectors and natural language description features, capturing deep source code information and learning weight information among different features during the fusion process. This results in code vectors containing rich semantic and structural information, allowing semantically similar code fragment vectors and natural language description vectors to be closer in the vector space, thereby improving code search accuracy.

4.3.2. Proposed SENCS Model Analysis

(1) The influence of the two-stage attention mechanism

The proposed SENCS algorithm incorporates a two-stage attention mechanism to enhance the accuracy of code search results. The first stage employs a multi-head attention mechanism in the feature extraction phase, improving the method name feature vector, character marker feature vector, program dependency sequence feature vector, and natural language description feature vector. The second stage utilizes a multi-head attention mechanism in the multi-feature fusion phase to learn the weight values of different vectors for effective fusion. To evaluate the impact of the two-stage attention mechanism on the code search performance of the SENCS algorithm, comparative experiments were conducted by removing the first stage, the second stage, and both attention mechanisms. The algorithm names are summarized in Table 6.

Table 6.

Algorithm name introduction.

Experiments were carried out on the CodeSearchNet and JavaNet datasets, with the results shown in Table 7 and Table 8. The data reveal that compared to a model without an attention mechanism, applying the attention mechanism in the feature semantic enhancement stage improved MRR by 3.00% and 2.31%, and DCG by 5.08% and 1.29%, on the two datasets, respectively. SR@1, SR@5, and SR@10 increased by 4.02%, 2.66%, and 2.43%, respectively for the first dataset, and by 2.78%, 2.04%, and 1.52%, respectively for the second dataset. When the attention mechanism was used in the feature fusion stage, MRR improved by 6.65% and 3.85%, DCG by 6.46% and 2.44% on the two datasets, respectively. SR@1, SR@5, and SR@10 increased by 8.62%, 6.48%, and 4.01%, respectively, for the first dataset, and 4.82%, 2.93%, and 2.10%, respectively, for the second dataset. When both attention mechanisms were applied, MRR increased by 9.44% and 5.70%, and DCG by 9.39% and 4.74%, with SR@1, SR@5, and SR@10 rising by 12.93%, 7.48%, and 5.59% for the first dataset, and 7.79%, 3.82%, and 2.69% for the second dataset, respectively. These findings demonstrate that employing a two-stage attention mechanism significantly enhances model accuracy. Notably, the attention mechanism in the semantic feature extraction phase provides substantial improvements in code search accuracy, as it captures weight information from different aspects of method names, character labels, and program dependency sequences, enriching the vector representations for feature fusion. Thus, the proposed SENCS algorithm shows significant improvements in search accuracy compared to algorithms without attention mechanisms.

Table 7.

Effect of two-stage attention mechanism on search accuracy with CodeSearchNet dataset.

Table 8.

Effect of two-stage attention mechanism on search accuracy with JavaNet dataset.

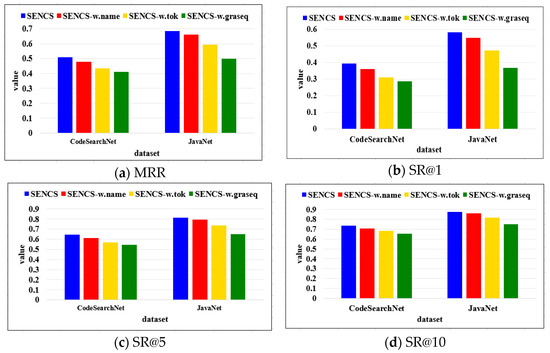

(2) Ablation experiment

To further investigate the impact of different code features on the code search performance of the SENCS algorithm, ablation experiments were designed. The three components—method name feature learning, character label feature learning, and program dependency graph sequence feature learning—were removed, and the resulting code search performance was evaluated on the CodeSearchNet and JavaNet datasets. The algorithm names are detailed in Table 9.

Table 9.

Algorithm name introduction.

Figure 5 visualizes the effect of the SENCS algorithm on code search accuracy after removing different code features from the CodeSearchNet and JavaNet datasets, highlighting the significance of each feature on overall performance.

Figure 5.

Influence of different code features with different datasets on search accuracy.

From Figure 5, it is evident that removing the program dependency graph sequence representation significantly impacts the proposed SENCS model. This is because the program dependency graph encapsulates control flow and data flow information related to code variables. Its serialized representation also contains semantic information from all character tags in the program. Consequently, removing this feature leads to a notable decline in search performance, particularly in the SR@1 metric. Character tagging information functions similarly to the textual sequence of code fragments, effectively matching keywords with those in the query statement. Removing this information hampers the model’s ability to capture comprehensive semantic and syntactic features of the code, thereby diminishing the performance of the proposed SENCS algorithm. While method name information quickly conveys the function and purpose of the code, its similarity to query statements is generally lower due to naming conventions. As a result, removing method name features has a comparatively smaller impact on the proposed SENCS algorithm’s performance. This analysis highlights that the proposed SENCS algorithm excels in code search by simultaneously leveraging method name, character tagging, and graph serialization features.

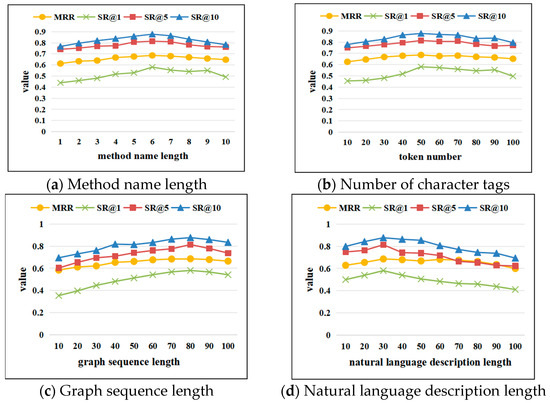

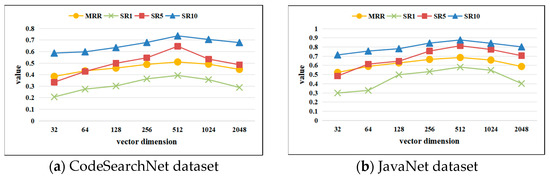

(3) Parameter sensitivity analysis

In deep learning-based code search algorithms, parameter sensitivity is crucial, as different parameters can significantly affect performance. To investigate this, comparative experiments were designed to analyze the effects of four feature parameters—method name length, number of character tags, graph sequence length, and natural language description length—on model performance using the CodeSearchNet and JavaNet datasets. The influence of different vector dimensions on model performance was evaluated using MRR, SR@1, SR@5, and SR@10. The experimental results are illustrated in Figure 6 and Figure 7.

Figure 6.

Influence of different parameters on code search performance.

Figure 7.

Influence of different vector dimensions on code search performance.

Figure 6a depicts the impact of method name sequence length on the proposed SENCS algorithm’s search accuracy. It is evident from the graph that a method name sequence length of 6 yielded the best performance across various evaluation metrics. Conversely, a length of 1 resulted in lower accuracy, as most function names exceed one word, with the first word often lacking significant semantic content. Figure 6b illustrates the effect of the number of character tags in the function character tagging sequence. The SENCS algorithm performed optimally when the number of tokens in the character tagging sequence was 50. Figure 6c examines the effect of encoding length in the function graph sequence on search accuracy. The best performance occurred with an encoding length of 80. As the graph sequence length decreases, accuracy drops significantly due to shorter sequences failing to comprehensively represent the information within the program dependency graph, resulting in lost semantic and structural information. Figure 6d presents the effect of the natural language description sequence length on search accuracy. The SENCS algorithm performed best with a sequence length of 30. When the length increases to 100, accuracy metrics decline because the model needs to process more semantic information, which can lead to complex and redundant descriptions that diminish the semantic similarity between the vector representation and the original statement.

Figure 7a,b show the impact of changes in code vector dimension and query vector dimension on the proposed SENCS algorithm’s search accuracy across the CodeSearchNet and JavaNet datasets. The optimal performance is observed with a vector representation dimension of 512. Deviations from this dimension, whether increasing or decreasing, resulted in lower MRR, SR@1, SR@5, and SR@10 metrics, establishing 512 as the ideal setting for vector dimensions in the proposed SENCS algorithm.

4.4. Discussion

The SENCS algorithm demonstrates significant improvements in code search by effectively integrating both semantic and structural information. By leveraging graph serialization and a two-stage attention mechanism, SENCS captures not only the surface-level syntax of the code but also its deeper functional and structural characteristics. This dual focus enhances the feature vectors of code snippets, making them richer in both semantic and structural details. Additionally, the algorithm’s ability to learn weight information during the feature fusion process ensures that the final vector representations are highly representative of the code’s true nature. As a result, semantically similar code fragments and natural language descriptions are brought closer together in the vector space, leading to more accurate and relevant search results. Furthermore, the enhanced understanding of natural language queries allows users to describe their needs more intuitively, improving the overall user experience and efficiency in finding the desired code snippets.

In contrast, models like DeepCS utilize the textual information and API information of the code, but DeepCS does not use the graph structure, nor the attention mechanism. Although GraphCodeBERT uses graph structure, it does not convert the graph structure into code features, but only utilizes the link relationship between nodes in the graph as a pre-training task. GSMM and other baseline models primarily focus on the semantic information of the code and natural language descriptions, often neglecting the structural information inherent in the code. This limitation means that these models may miss important contextual and structural details that are crucial for accurately understanding and matching code fragments.

In this paper, SENCS considers logical relationships such as control relationships between code statements, dependencies between data, etc., which are important features that can reflect the nature of the code, and such features can all be modeled by graphs (e.g., PDG used in this paper.) Related models such as DeepCS, GraphCodeBERT, etc., do not take the structure of code graphs as an important feature of code representation. The feature vectors generated by GSMM and similar models may not fully capture the nuanced relationships between code elements, leading to less accurate and less effective code search results. Additionally, they all lack the advanced attention mechanisms that allow the SENCS algorithm to dynamically weigh different features based on their importance in the context of the query. SENCS captures the structural information with deep semantics implicit in the code graph and fuses it with textual and API information as a representation of the code through an attention mechanism, thus providing better performance. This is the main innovation of SENCS. The SENCS algorithm provides a more comprehensive and robust approach to code search, significantly enhancing its performance compared to existing methods.

In future research, we will consider comparing with these latest transformer models to further evaluate the performance of SENCS compared with state-of-the-art technology. This can help us understand the relative advantages and disadvantages of SENCS in the latest algorithm environment and provide a reference for further optimization of the model.

5. Conclusions

In this paper, we propose SENCS, an advanced code search model that can be used in various real-world scenarios such as code recommendation systems or code completion tasks. Code search is a critical research task in the field of software engineering, aiming to utilize natural language queries to locate semantically similar code fragments within extensive code databases. This process enhances the development efficiency of software developers by returning relevant code snippets based on user queries. Currently, most code search algorithms extract semantic and structural feature information from code snippets to generate vector representations. While GNN models are commonly employed to capture code structure features, these models often fail to delve deeply into the complex structural information of code graphs, leading to partial information loss and diminished search accuracy.

This article explores natural language-based code search algorithms and proposes a novel deep semantic-enhanced neural code search algorithm called SENCS that combines graph serialization with a two-stage attention mechanism to improve search accuracy. The algorithm employs a Bi-LSTM model and an MLP model to learn the semantic feature information from method names and character tags of source code fragments, generating corresponding feature vectors. Additionally, the source code’s program dependency graph is extracted, utilizing a specified edge-first traversal method to create a unique serialized representation of the graph as structural feature information. A Bi-LSTM model further captures the deep structural features within this graph sequence, generating program dependency graph feature vectors.

To enrich the semantic and structural information embedded in the source code fragment vectors, the proposed algorithm introduces a two-stage attention mechanism. This mechanism employs multi-head attention to enhance features across multiple code feature vectors and natural language description vectors. During the fusion of these vectors, it captures diverse aspects of code feature information, facilitating a better integration of semantic and structural features. Consequently, this approach generates a robust code vector representation, effectively realizing the code search algorithm. Extensive experiments on two open-source datasets and comparisons with three advanced models demonstrate that our approach can achieve the best code search effect

The practical significance of the SENCS algorithm lies in its ability to significantly enhance the efficiency and effectiveness of code search for software developers. By providing more accurate and contextually relevant search results, SENCS can reduce the time and effort required to find suitable code snippets, thereby accelerating the development process. This is particularly valuable in large-scale software projects where developers often need to navigate vast codebases to find specific functionalities. Moreover, the algorithm’s capability to understand and leverage both semantic and structural information ensures that the returned code snippets are not only syntactically correct but also functionally appropriate, reducing the likelihood of introducing bugs or inefficiencies.

For future work, we plan to leverage transformers and pre-trained models to further enhance the effectiveness of our algorithm. Specifically, we will explore the integration of advanced models such as CodeBERT and Codex, which have shown promising results in natural language and code understanding tasks. These models can provide deeper semantic insights and improve the accuracy of code search by better capturing the nuances of both code and natural language queries. Additionally, we aim to address the scalability of our algorithm by optimizing it to handle larger code repositories efficiently. This will involve developing methods to reduce computational complexity and improve processing speed, ensuring that the algorithm remains performant even with vast datasets. We will also investigate the performance of our algorithm across different programming languages, adapting the feature extraction and vector generation processes to accommodate the unique characteristics of each language. By pursuing these directions, we aim to make our code search algorithm more robust, efficient, and widely applicable.

Author Contributions

Software, Y.S., L.M. and Y.G.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.Y. and Y.G.; writing—review and editing, Y.Y., L.M., Y.G., F.W. and Y.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Kim, K.; Ghatpande, S.; Kim, D.; Zhou, X.; Liu, K.; Bissyandé, T.F.; Klein, J.; Le Traon, Y. Big Code Search: A Bibliography. ACM Comput. Surv. 2024, 56, 1–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Lin, J.; Dong, H.; Zhang, L.; Wu, Z. Survey of Code Search Based on Deep Learning. ACM Trans. Softw. Eng. Methodol. 2024, 33, 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, A.J.; Myers, B.A.; Coblenz, M.J.; Aung, H.H. An exploratory study of how developers seek, relate, and collect relevant information during software maintenance tasks. IEEE Trans. Softw. Eng. 2006, 32, 971–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Hu, X.; Li, Z.; Gao, C.; Xia, X.; Lo, D. Code Search is All You Need? Improving Code Suggestions with Code Search. In Proceedings of the ICSE 2024: IEEE/ACM 46th International Conference on Software Engineering, Lisbon, Portugal, 14–20 April 2024; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Brandt, J.; Guo, P.J.; Lewenstein, J.; Dontcheva, M.; Klemmer, S.R. Two studies of opportunistic programming: Interleaving web foraging, learning, and writing code. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Boston, MA, USA, 4–9 April 2009; pp. 1589–1598. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, X.; Zhang, H.; Kim, S. Deep code search. In Proceedings of the 40th International Conference on Software Engineering, Gothenburg, Sweden, 27 May–3 June 2018; pp. 933–944. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Kim, S.; Murali, V.; Chaudhuri, S.; Chandra, S. Neural query expansion for code search. In Proceedings of the 3rd ACM SIGPLAN International Workshop on Machine Learning and Programming Languages, Phoenix, AZ, USA, 22 June 2019; pp. 29–37. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, S.; Zhao, Y.; Liang, Y. Code Search Combining Graph Embedding and Attention Mechanism. J. Front. Comput. Sci. Technol. 2022, 16, 844. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Y.; Yin, Y.; Wang, Z.; Lo, D.; Zhang, T.; Xia, X.; Zhao, Y.; Xu, B. How to better utilize code graphs in semantic code search? In Proceedings of the 30th ACM Joint European Software Engineering Conference and Symposium on the Foundations of Software Engineering, Singapore, 14–18 November 2022; pp. 722–733. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Nong, Z.; Gao, C.; Li, Z.; Zeng, J.; Xing, Z.; Liu, Y. Enriching query semantics for code search with reinforcement learning. Neural Netw. 2022, 145, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, Z.; Guo, D.; Tang, D.; Duan, N.; Feng, X.; Gong, M.; Shou, L.; Qin, B.; Liu, T.; Jiang, D.; et al. CodeBERT: A pre-trained model for programming and natural languages. In Proceedings of the EMNLP 2020: Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Online, 16–20 November 2020; pp. 1536–1547. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, D.; Ren, S.; Lu, S.; Feng, Z.; Tang, D.; Liu, S.; Zhou, L.; Duan, N.; Svyatkovskiy, A.; Fu, S.; et al. GraphCodeBERT: Pre-training code representations with data flow. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations, Vienna, Austria, 4 May 2021; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Chai, Y.; Zhang, H.; Shen, B.; Gu, X. Cross-domain deep code search with meta learning. In Proceedings of the 44th International Conference on Software Engineering, Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 22–27 May 2022; pp. 487–498. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, H.C.; Luk, R.W.; Wong, K.F.; Kwok, K.L. Interpreting TF-IDF term weights as making relevance decisions. ACM Trans. Inf. Syst. (TOIS) 2008, 26, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, S.; Zaragoza, H. The probabilistic relevance framework: BM25 and beyond. Found. Trends Inf. Retr. 2009, 3, 333–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, F.; Zhang, H.; Lou, J.G.; Wang, S.; Zhang, D.; Zhao, J. Codehow: Effective code search based on api understanding and extended boolean model(e). In Proceedings of the 30th IEEE/ACM International Conference on Automated Software Engineering (ASE), Lincoln, NE, USA, 9–13 November 2015; pp. 260–270. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Q.; Yan, S.; Xie, T.; Mei, H. Relationship-aware code search for JavaScript frameworks. In Proceedings of the 2016 24th ACM SIGSOFT International Symposium on Foundations of Software Engineering, Seattle, WA, USA, 13–18 November 2016; pp. 690–701. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, F.; Niu, H.; Keivanloo, I.; Zou, Y. Expanding queries for code search using semantically related api class-names. IEEE Trans. Softw. Eng. 2017, 44, 1070–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghothaman, M.; Wei, Y.; Hamadi, Y. SWIM: Synthesizing what I mean. In Proceedings of the 38th International Conference on Software Engineering, Austin, TX, USA, 14–22 May 2016; pp. 357–367. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, S.H.; Fung, B.C.; Charland, P. Kam1n0: Mapreduce-based assembly clone search for reverse engineering. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 August 2016; pp. 461–470. [Google Scholar]

- Sachdev, S.; Li, H.; Luan, S.; Kim, S.; Sen, K.; Chandra, S. Retrieval on source code: A neural code search. In Proceedings of the 2nd ACM SIGPLAN International Workshop on Machine Learning and Programming Languages, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 18 June 2018; pp. 31–41. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, D.; Yang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Lin, Y.; Xu, K.; Lin, H. Multi-level semantic representation model for code search. In Proceedings of the Joint Conference of the Information Retrieval Communities in Europe (CIRCLE), Toulouse, France, 6–9 July 2020; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Salza, P.; Schwizer, C.; Gu, J.; Gall, H.C. On the effectiveness of transfer learning for code search. IEEE Trans. Softw. Eng. 2023, 49, 1804–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, M.; Dong, D.; Lu, P. Input Transformation for Pre-Trained-Model-Based Cross-Language Code Search. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 23rd International Conference on Software Quality, Reliability, and Security Companion (QRS-C), Chiang Mai, Thailand, 22–26 October 2023; pp. 403–412. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Ding, Y.; Hu, E.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, Y. Enhancing Code Representation Learning for Code Search with Abstract Code Semantics. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN), Yokohama, Japan, 30 June–5 July 2024; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallejo-Huanga, D.; Morocho, J.; Salgado, J. SimilaCode: Programming Source Code Similarity Detection System Based on NLP. In Proceedings of the 2023 15th International Congress on Advanced Applied Informatics Winter (IIAI-AAI-Winter), Bali, Indonesia, 11–13 December 2023; pp. 171–178. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, B.; Yu, Y.; Hu, Y. CSSAM: Code Search via Attention Matching of Code Semantics and Structures. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Software Analysis, Evolution and Reengineering (SANER), Taipa, Macao, 21–24 March 2023; pp. 402–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saieva, A.; Chakraborty, S.; Kaiser, G. REINFOREST: Reinforcing Semantic Code Similarity for Cross-Lingual Code Search Models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2305.03843. [Google Scholar]

- Wan, Y.; Shu, J.; Sui, Y.; Xu, G.; Zhao, Z.; Wu, J.; Yu, P. Multi-modal attention network learning for semantic source code retrieval. In Proceedings of the 34th IEEE/ACM International Conference on Automated Software Engineering (ASE), San Diego, CA, USA, 11–15 November 2019; pp. 13–25. [Google Scholar]

- Husain, H.; Wu, H.H.; Gazit, T.; Allamanis, M.; Brockschmidt, M. Codesearchnet challenge: Evaluating the state of semantic code search. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1909.09436. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).