Abstract

Reversible computation is very important to minimize energy dissipation and prevent information loss not only in quantum computing but also in digital computing. Therefore, interest in designing efficient universal logic gates has recently increased. In this study, we efficiently design the Fredkin gate (FRG), a well-known conservative reversible operation gate, using quantum-dot cellular automata (QCA), and propose a D-latch using it. The proposed FRG structure can be designed efficiently using the structure of a QCA multiplexer using cell interaction, and a symmetric structure was designed. The proposed structure was simulated using QCADesigner 2.0.3 and QCADesigner-E for accurate comparison of various performance metrics, and the proposed structure clearly shows superiority in most performances and two representative design costs. Therefore, the lightweight design of an efficient reversible gate prevents data loss and increases information reliability.

1. Introduction

Reversible computation was proposed in the 1970s by Bennett, who was inspired by Landauer’s discovery that information deletion requires entropy [1,2]. Landauer demonstrated that the loss of 1 bit of information results in a loss of energy of kBTln2 joules where kB = 1.38 × 10−23 JK−1 is the Boltzmann constant and T is the temperature in Kelvin, and Bennett demonstrated the feasibility of this energy loss in an irreversible circuit being recoverable in a reversible circuit [3]. This showed a direct connection between information loss, energy dissipation, and reversible circuits. The most famous example of reversible computing is the billiard ball computer developed by Fredkin and Toffoli, which calculates the collision function of a billiard ball using reversible logic [4]. Afterwards, Bruce et al. designed a reversible carry-ripple adder and carry-skip adder using Fredkin gates [5].

Quantum-dot cellular automata (QCA) proposed by Lent and Tougaw is attracting attention as an alternative that can overcome the problems of high-power loss and information loss in existing irreversible CMOS-VLSI circuits [6,7]. The dissipated energy is measured based on the Hamiltonian matrix using the HartreeFock approximation in relation to the Coulomb repulsion between QCA cells as shown in Equation (1) [8].

where is the energy cost of two neighboring cells with opposite polarization, called kink energy, and denotes the polarization of the i-th neighboring cell and, denotes the geometrical factor identifying the electrostatic interaction between cells i and j due to the geometrical distance. The kink energy is a value related to the cost of energy in two cells with different polarizations. γ refers to the electron tunneling energy that changes depending on the clock. The nonadiabatic power estimation model was used to estimate the power loss or energy dissipation of the cell [9,10]. ) means the sum of the kink energy of polarized neighbors.

The power dissipation using the Hamiltonian matrix shown in Equation (1) can be summarized in terms of energy per clock cycle as shown in Equation (2) [10].

where is the clock period and and are the Hamiltonian values before and after the transaction.

Recently, with the rapid development of the quantum computing environment, interest in reversible computing is increasing, and much interest continues in the implementation of reversible gates using QCA in the digital computing environment. QCA-based Feynman gate [11,12,13,14], QCA-based Toffoli gate [15,16,17], and QCA-based Peres gate [18,19,20] have XOR as the main operation, so the design of an efficient QCA-based XOR gate can have a significant impact on the performance of the circuit. After the Fredkin gate appeared, interest in the development of conservative gates increased [21]. However, since the QCA-based Fredkin gate [22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30] includes the operation of a multiplexer (MUX), the design of a QCA-based MUX can be an important issue. One of the most common applications using Mux is D-latch. This is because a D-latch can be easily designed by reusing the output of the Mux as an input. Therefore, various studies are in progress on the design of D-latches using reversible gates [30,31,32,33]. In the proposed study, the Fredkin gate (FRG), which can be used as a universal reversible gate, is efficiently designed using QCA, and an efficient D-latch is designed using the FRG. The key contributions of this study are summarized as follows.

- FRGs, which are universal reversible gates, are designed using QCA.

- Conservative reversible D-latches using the proposed FRGs are designed.

- The proposed study analyzes the performance of cell count, area, delay, and energy dissipation required for implementation, calculates two representative standard design costs, and compares them with existing studies.

- The proposed QCA-based circuits showed significant improvement in most performances and design costs compared to existing excellent circuits.

The paper is structured as follows. Section 2 describes the basic knowledge of FRG, QCA, and QCA circuits. Section 3 shows the proposed QCA-based FRGs and D-latches. In Section 4, the proposed structures are compared with existing circuits in terms of performances and design costs. Finally, Section 5 summarizes the study and presents conclusions.

2. Related Works

This section briefly reviews the basic knowledge about FRG, QCA, QCA-based MUX, and D-latches.

2.1. Fredkin Gate

Reversible computation makes it possible to completely restore the initial state in a system with a single final state value. For example, a NOT gate can be returned to its initial state without any information loss by performing two NOT gate operations. However, it is impossible to return the result of an AND or OR gate to the initial state. This is because one result value was created with two inputs, but it is logically impossible to create two input values with one result value. Therefore, a reversible gate must have the same number of inputs and outputs.

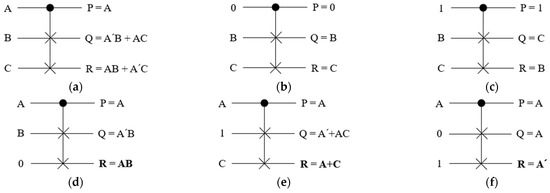

Controlled SWAP (CSWAP) gate is a 3 × 3 reversible gate introduced by Fredkin. It has one control bit A and two target bits B and C, and is called Fredkin gate (FRG) as shown in Figure 1a with its truth table in Table 1. This is a conservative logic gate that operates by exchanging two target bits only when A is 1, as shown in Figure 1c, and does not operate otherwise, as shown in Figure 1b [4]. FRG is a universal gate that can express all Boolean functions. Figure 1d–f show the logical expressions of AND, OR, and NOT using FRG, respectively.

Figure 1.

Quantum circuit diagram of FRG: (a) CSWAP: F(A, B, C); (b) No operation: F(0, B, C); (c) Swap: F(1, B, C); (d) AND operation: F(A, B, 0); (e) OR operation: F(A, 1, C); (f) NOT operation: F(A, 0, 1).

Table 1.

Truth table of Fredkin gate (P is a garbage output, and Q and R output the multiplexer operation results of inputs B and C for the selected input A or A′).

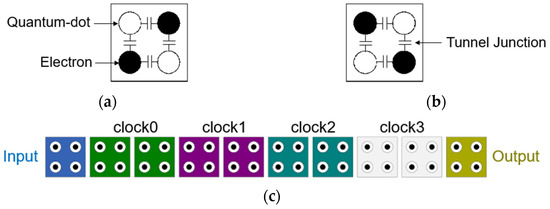

2.2. Basics of QCA

A QCA cell consists of four quantum dots and is located at each corner of a square cell. Two electrons are located on two diagonals due to Coulomb repulsion, and this is expressed as P = +1 or P = −1 as shown in Figure 2a,b. These become 1 or 0 in binary operations. Figure 2c shows the QCA wiring with one input cell and one output cell. Wiring can be easily obtained by arranging the QCA cells in succession, and the QCA clock cycle consists of four clock phases displayed in different colors from clock0 to clock3 [8,34].

Figure 2.

QCA cell: (a) P = +1; (b) P = −1; (c) QCA wire with four clock phases.

In QCA, values are transmitted as the barrier height between quantum dots changes over time, as shown in Figure 3. A QCA cell has four states: switch, hold, release, and relax. Switch is a state in which the barrier between quantum dots is increasing, and hold is a state in which the barrier between quantum dots has become sufficiently high that electrons cannot move between quantum dots. At this time, the potential energy of the electrons is at its strongest and has a clear polarization. Release refers to a state in which the barrier between quantum dots is gradually lowering, and relax refers to a state in which the barrier between quantum dots is sufficiently lowered so that the potential energy of electrons is lowered and tunneling is possible freely [8].

Figure 3.

Four different states of the QCA clock depending on the barrier height between quantum dots and changes in time. (switch: a state in which the barrier between quantum dots gradually increases; hold: a state in which the barrier becomes sufficiently high that electrons cannot move; release: a state in which the barrier gradually decreases; relax: a state in which the barrier becomes sufficiently low that electrons are free to move).

2.3. QCA-Based Multiplexer and D-Latch

A 2-to-1 MUX is a combination circuit that receives two inputs and uses a selector to select one of the input values and output it. When the two inputs are B and C and the selector is A, the output F is as follows.

As shown in Equation (3), the logic expression of the 2-to-1 MUX can be expressed with three majority gates, and is the same as the output Q of the Fredkin gate shown in Table 1. Also, if the order of the two inputs and B and C is changed, the result of Equation (3) is the same with the output R of the Fredkin gate. Therefore, a well-made 2-to-1 MUX can determine the performance of the Fredkin gate.

Existing QCA-based MUX is divided into a majority gate-based circuit [35,36,37,38] and cell interaction-based circuit [39,40,41,42,43]. Circuits based on majority gates are easy to design and read, are structurally simple, and have low-energy consumption. However, there are limits to minimizing the number and area of cells. On the other hand, circuits based on cell interaction are difficult to design and read, and the number and area of cells, as well as delay, can be minimized. Additionally, the noise of the output signal can be relatively reduced.

Meanwhile, the D-latch is a very important design element applied to various sequential circuits. It can be expanded to D-flip-flops and shift registers and is used as a basic element in various memory structures. Various studies have shown that the design of a D-latch is possible by returning the output of a 2-to-1 MUX circuit back to the input value [44,45,46]. Additionally, research was conducted on D-latch design using reversible gates. Chabi et al. designed an FRG using an XOR gate and a 2-to-1 MUX, Bhoi et al. proposed a new parity-preserving reversible gate, and in two cases, Mohammadi et al. and Naz et al. designed an FRG based on majority voting gates. They all designed D-latches using the proposed reversible gates [30,31,32,33].

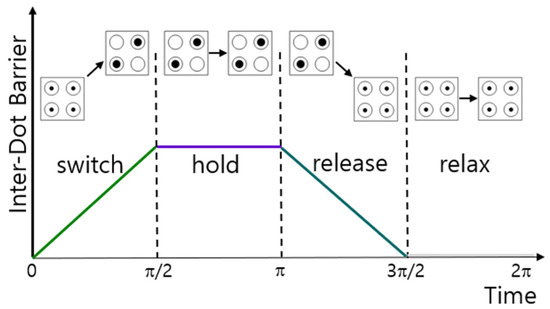

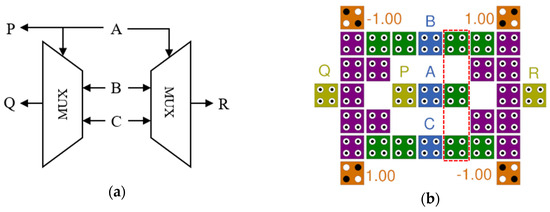

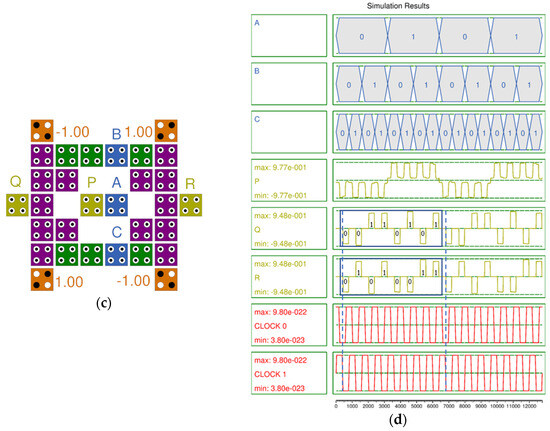

3. Proposed QCA-Based Fredkin Gate

As shown in Figure 1a, the output of FRG, Q = A′B + AC, is the same as the output of a 2-to-1 multiplexer (MUX) with a selection input A and two inputs B and C. By the same principle, R = AB + A′C is the same as the output of a 2-to-1 MUX with only the order of the two inputs changed. Therefore, the FRG in Figure 1a can be expressed as two facing 2-to-1 MUXs as in Figure 4a. The MUX that best matches the structure is the symmetrical MUX proposed by Jeon in [39], and it is possible to obtain a square-shaped FRG with a completely symmetrical structure as shown in Figure 4b. A, the selector, is input to two MUXes on both sides of the circuit, and B and C are also input to both the left and right from the center of the circuit. At this time, the garbage output P is obtained immediately on the first clock phase. The other two effective outputs Q and R are obtained very stably outside the circuit on the second clock phase, and 33 cells and an area of 24,564 nm2 were used for the QCA-based FRG (QFRG). Figure 4c shows an improved QFRG (IQFRG) with the three cells indicated by the red dotted line in Figure 4b deleted, while still maintaining vertical symmetry, and 30 cells and an area of 21,804 nm2 were used. Both proposed structures have the same simulation results as shown in Figure 4d. The results of Q and R are output to CLOCK1, the second clock phase, and the result value is also confirmed to be the same as the truth table in Table 1.

Figure 4.

Proposed FRG structures: (a) A logic diagram of FRG using two 2-to-1MUX; (b) QCA implementation of FRG (QFRG); (c) Improved QFRG (IQFRG); (d) Simulation result of QFRG and IQFRG.

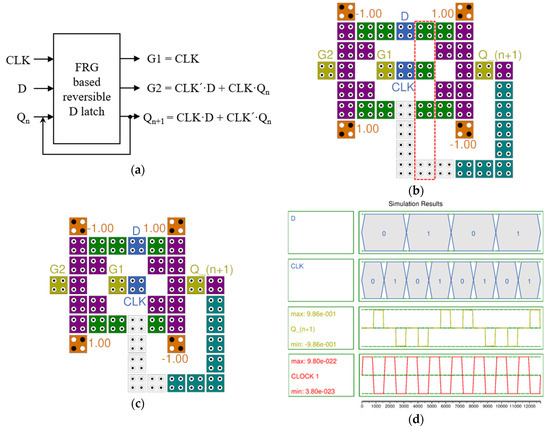

FRG can be used as a reversible D-latch by adjusting the input and output and adding wires, as shown in Figure 5a. The three inputs are as follows. The first is the clock of the latch, the second is the value to be stored in the D-latch, and the third is the output value of the nth D-latch. As a result, garbage output values of G1 = CLK and G2 = CLK′·D + CLK·Qn are generated, and Qn+1 = CLK·D + CLK′·Qn, the current storage value of the D-latch, is output. Figure 5b completes the D-latch based on QFRG (DQFRG) by returning the output value, Qn+1, back to the position of the input value to make a loop, and requires 46 cells and an area of 35,244 nm2. Since two clock phases are used for the internal operation of the FRG gate, the loop also used two clock phases. Therefore, the value of the D-latch is updated every two clock phases. Figure 5c shows the D-latch with IQFRG (DIQFRG) applied, which can greatly reduce cells and area, and requires 42 cells and an area of 31,684 nm2. Figure 5d shows the simulation results of the proposed two FRG-based reversible D-latches. The simulation result shows that the value of the D-latch is updated every two clock phases according to Table 2, and shows very high output polarization and a stable, noise-free output signal.

Figure 5.

Proposed D-latch structures: (a) A block diagram of reversible D-latch based on FRG; (b) QCA implementation of D-latch based on QFRG (DQFRG); (c) D-latch with improved DQFRG (DIQFRG); (d) Simulation result of DQFRG and DIQFRG.

Table 2.

Truth table of Fredkin gate-based reversible D-latch.

Table 2 shows the truth table of the proposed Fredkin gate-based reversible D-latch. When CLK is 0, the existing value of Qn is output as Qn+1 regardless of the value of the D-input to the latch, and when CLK is 1, it shows that Qn+1 is output according to the value of the D-input to the latch.

4. Performance Analysis and Comparison

In this section, in order to measure the performance of the circuits, area and delay were obtained using QCADesigner 2.0.3, and energy dissipation was measured using QCADesinger-E 2.2 [47,48]. The simulation engine and parameters used are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Simulation engines and parameters on QCADesinger2.0.3 and QCADesigner-E.

The metrics to be used as indicators for performance analysis are as follows. Cell count is the number of QCA cells used for design, area means cutting the plane space required for design into a rectangle, and delay indicates the clock phase at which the first output for all inputs occurs. Energy dissipation indicates the total energy loss required to operate the entire circuit. is a standard design cost indicator expressed as the product of the square of area and delay, as shown in Equation (4). This is because the importance of delay is evaluated more highly due to the recent rapid development of hardware. is a standard design cost indicator defined as Equation (5) by calculating energy dissipation and delay [49].

where A, D, and E refer to the area, delay, and energy dissipation required in circuit design.

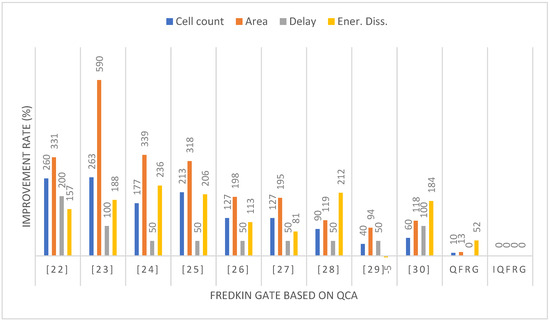

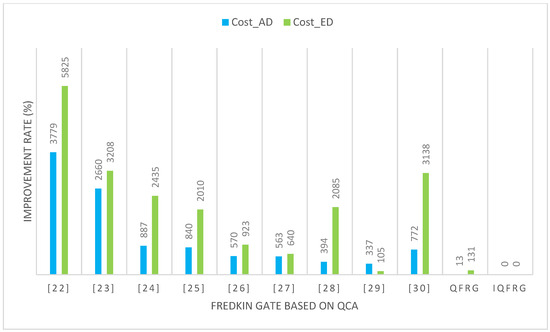

Table 4 shows a comparison of the performances and design costs of QCA-based Fredkin gates. The proposed IQFRG showed excellent results in most performance metrics but energy dissipation. The proposed circuit is slightly larger in energy dissipation than the circuit in [29], however, since this indicator has a trade-off relationship with delay, it was confirmed that the proposed circuit was reduced by at least two times compared to the existing circuit in , which is the design cost of the circuit calculated by considering delay as well. The improvement rate for each metric is shown in Figure 6 and Figure 7.

Table 4.

Performance and design cost comparison of Fredkin gates.

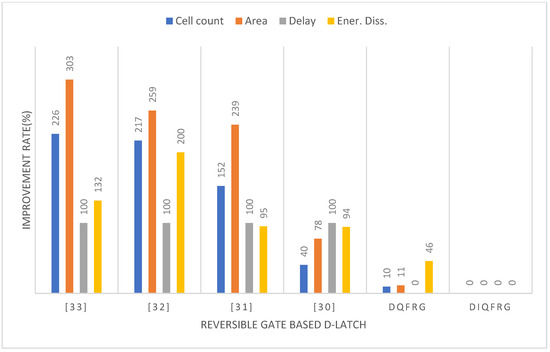

Figure 6.

Performance improvement of proposed QFRG and IQFRG compared with typical FRG based on QCA.

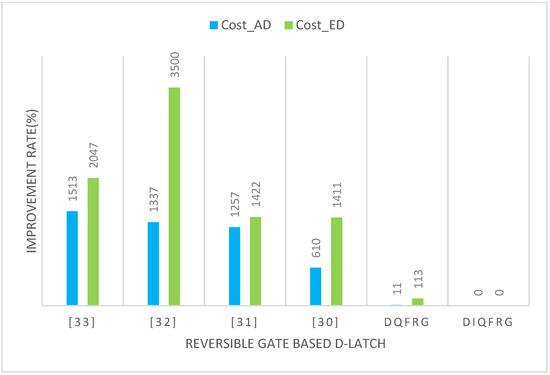

Figure 7.

Improvement of design costs of proposed QFRG and IQFRG compared with typical FRG based on QCA.

Figure 6 shows a comparison of various performances, and the proposed IQFRG showed improvement rates of at least 40%, 94%, and 50% in cell count, area, and delay, respectively. Energy dissipation was also found to be the best except for one circuit. However, considering the trade-off between energy dissipation and delay, the results seem to be good enough. This becomes clear when checking the design cost, , in Figure 7.

The IQFRG proposed in and , the two representative design costs in Figure 7, was confirmed to require the lowest design costs while showing remarkable improvement rates of 337% and 105%, respectively, compared to the best existing research.

Table 5 compares the performances and design costs of reversible gate-based D-latches. The proposed DQFRG and DIQFRG were found to be the best in all metrics and brought about great progress in design costs by significantly improving delay. The improvement rate for each metric is shown in Figure 8 and Figure 9.

Table 5.

Performance and design cost comparison of reversible gate-based D-latches.

Figure 8.

Performance improvement of proposed DQFRG and DIQFRG compared with typical reversible gate-based D-latches.

Figure 9.

Improvement of design costs of proposed DQFRG and DIQFRG compared with typical reversible gate-based D-latches.

As shown in Figure 8, the proposed DIQFRG showed significant improvement rates of at least 40%, 78%, 100%, and 94% in cell count, area, delay, and energy dissipation. In addition, the proposed DIQFRG clearly demonstrated the superiority of the proposed structures by showing incredible improvement rates of 610% and 1411% in and compared to the best existing circuits.

5. Conclusions

The proposed research sought to efficiently design a Fredkin gate, a well-known reversible and universal logic gate. QCA was used to minimize design costs through fast switching speed and minimal use of area. For the first time, a perfectly symmetrical QFRG based on QCA MUX was proposed and then a modified vertically symmetrical IQFRG was proposed. All circuits were tested by well-known simulators, and the proposed IQFRG showed significant improvement rates of 337% and 105% in two design cost indices. Additionally, a D-latch was proposed using the structural characteristics of the proposed structures. The proposed DIQFRG demonstrated the superiority of the proposed structures by showing incredible improvement rates of 610% and 1411% in two design cost indices. In the modern digital computing era, the problem of power or energy dissipation is directly related to information loss and requires continuous research, and much attention is needed on the efficient design of QCA-based reversible gates and their applications to solve these problems.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bennett, C.H. Logical reversibility of computation. IBM J. Res. Dev. 1973, 17, 525–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landauer, R. Irreversibility and heat generation in the computing process. IBM J. Res. Dev. 1961, 5, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feynman, R. Quantum Mechanical Computers. Opt. News 1985, 11, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredkin, E.; Toffoli, T. Conservative Logic. Int. J. Theor. Phys. 1982, 21, 219–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruce, J.W.; Thornton, M.A.; Shivakumaraiah, L.; Kokate, P.S.; Li, X. Efficient adder circuits based on a conservative reversible logic gate. In Proceedings of the IEEE Computer Society Annual Symposium on VLSI, IEEE Computer Society, Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 25–26 April 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Lent, C.S.; Tougaw, P.D.; Porod, W. Quantum cellular automata: The physics of computing with arrays of quantum dot molecules. Proc. Workshop Phys. Comput. 1994, 17, 5–13. [Google Scholar]

- Tougaw, P.D.; Lent, C.S. Logical devices implemented using quantum cellular automata. J. Appl. Phys. 1993, 75, 1818–1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tougaw, P.D.; Lent, C.S. Dynamic behavior of quantum cellular automata. J. Appl. Phys. 1996, 80, 4722–4736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, S.; Sarkar, S.; Bhanja, S. Power dissipation bounds and models for quantum-dot cellular automata circuits. In Proceedings of the 2006 Sixth IEEE Conference on Nanotechnology, Cincinnati, OH, USA, 17–20 July 2006; Volume 1, pp. 375–378. [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava, S.; Sarkar, S.; Bhanja, S. Estimation of upper bound of power dissipation in QCA circuits. IEEE Trans. Nanotechnol. 2009, 8, 116–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patidar, M.; Gupta, N. An ultra-efficient design and optimized energy dissipation of reversible computing circuits in QCA technology using zone partitioning method. Int. J. Inf. Technol. 2021, 14, 1483–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, C.; Panda, S.; Mukhopadhyay, A.K.; Maji, B. Utilization of LTEx Feynman Gate in Designing the QCA Based Reversible Binary to Gray and Gray to Binary Code Converters. Micro Nanosyst. 2020, 12, 187–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahar, A.N.; Ahmad, F.; Nahid, N.M.; Hassan, K.; Al Shafi, A.; Ahmed, K. An optimal design of conservative effi-cient reversible parity logic circuits using QCA. Int. J. Inf. Technol. 2018, 11, 785–794. [Google Scholar]

- Debnath, B.; Das, J.C.; De, D.; Ghaemi, F.; Ahmadian, A.; Senu, N. Reversible Palm Vein Authenti-cator Design with Quantum Dot Cellular Automata for Information Security in Nanocommunication Network. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 174821–174832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahabi, M.; Rahimi, E.; Lyakhov, P.; Bahar, A.N.; Wahid, K.A.; Otsuki, A. Novel Quantum-Dot Cellular Automata-Based Gate Designs for Efficient Reversible Computing. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safoev, N.; Abdukhalil, G.; Abdisalomovich, K.A. QCA based Priority Encoder using Toffoli gate. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 14th International Conference on Application of Information and Communication Technologies (AICT), Tashkent, Uzbekistan, 7–9 October 2020; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal, J.; Banday, M.T. Applications of Toffoli Gate for designing the classical gates using quantum-dot cellular automata. Int. J. Recent. Sci. Res. 2015, 6, 7764–7769. [Google Scholar]

- Patidar, M.; Arul Kumar, D.; William, P.; Loganathan, G.B.; Mohathasim Billah, A.; Manikandan, G. Optimized design and investigation of novel reversible toffoli and peres gates using QCA techniques. Meas. Sens. 2024, 32, 101036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, J.C.; De, D. Novel low power reversible binary incrementer design using quantum-dot cellular automata. Microprocess. Microsyst. 2016, 42, 10–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reshi, J.I.; Banday, M.T. Realization of Peres gate as universal structure using quantum Dot cellular automata. J. Nanosci. Technol. 2016, 2, 115–118. [Google Scholar]

- Thapliyal, H.; Ranganathan, N. Conservative QCA Gate (CQCA) for Designing Concurrently Testable Molecular QCA Circuits. In Proceedings of the 2009 22nd International Conference on VLSI Design, New Delhi, India, 5–9 January 2009; pp. 511–516. [Google Scholar]

- Bhoi, B.K.; Misra, N.K.; Pradhan, M. Analysis on Fault Mapping of Reversible Gates with Ex-tended Hardware Description Language for Quantum Dot Cellular Automata Approach. Sens. Lett. 2019, 17, 371–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, J.C.; De, D. Computational fidelity in reversible quantum-dot cellular automata channel routing under thermal randomness. Nano Commun. Netw. 2018, 18, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundu, A.; Das, J.C.; De, D. RSCV: Reversible Select, cross and variation architecture in quantum-dot cellular automata. IET Quantum Commun. 2022, 3, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kianpour, M.; Sabbaghi-Nadooshan, R. Novel 8-bit reversible full adder/subtractor using a QCA reversible gate. J. Comput. Electron. 2017, 16, 459–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasamal, T.N.; Singh, A.K.; Ghanekar, U. Toward Efficient Design of Reversible Logic Gates in Quantum-Dot Cellular Automata with Power Dissipation Analysis. Int. J. Theor. Phys. 2017, 57, 1167–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, N.; Misra, N.K.; Bhoi, B.K.; Kumar, S. Reversible Gate Mapping into QCA Explicit Cells Packed with Single Layer. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2021, 1119, 012004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, A.; Singh, A.D.; Saha, A.; Saha, S.; Gupta, V.; Qingyi, Z.; Bhattacharya, S.; Bhattacharjee, S. A Novel Design of Reversible Gate using Quantum-Dot Cellular Automata (QCA). In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 1st International Conference for Convergence in Engineering (ICCE), Kolkata, India, 5–6 September 2020; pp. 110–115. [Google Scholar]

- Abutaleb, M.M. Robust and efficient QCA cell-based nanostructures of elementary reversible logic gates. J. Supercomput. 2018, 74, 6258–6274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naz, S.F.; Ahmed, S.; Sharma, S.; Ahmad, F.; Ajitha, D. Fredkin gate based energy efficient reversible D flip flop design in quantum dot cellular automata. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 46, 5248–5255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chabi, A.M.; Roohi, A.; Khademolhosseini, H.; Sheikhfaal, S.; Angizi, S.; Navi, K.; DeMara, R.F. Towards ultra-efficient QCA reversible circuits. Microprocess. Microsyst. 2017, 49, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhoi, B.; Misra, N.K.; Pradhan, M.; Chong Tan, S. Design and evaluation of an efficient parity-preserving reversible QCA gate with online testability. Cogent Eng. 2017, 4, 1416888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, Z.; Navi, K.; Sabbaghi-Nadooshan, R. Design of testable reversible latches by using a novel efficient implementation of Fredkin gate. Int. J. Electron. 2020, 107, 859–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safoev, N.; Jeon, J.C. A novel controllable inverter and adder/subtractor in quantum-dot cellular automata using cell interaction based XOR gate. Microelectron. Eng. 2020, 222, 111197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azimi, S.; Angizi, S.; Moaiyeri, M.H. Efficient and Robust SRAM Cell Design Based on Quantum-Dot Cellular Automata. ECS Solid State Sci. Technol. 2018, 7, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasamal, T.N.; Singh, A.K.; Ghanekar, U. Design and Implementation of QCA D-Flip-Flops and RAM Cell Using Majority Gates. J. Circuits Syst. Comput. 2019, 8, 1950079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, J.C. Designing nanotechnology QCA–multiplexer using majority function-based NAND for quantum computing. J. Supercomput. 2021, 77, 1562–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezai, A.; Aliakbari, D.; Karimi, A. Novel multiplexer circuit design in quantum-dot cellular automata technology. Nano Commun. Netw. 2023, 35, 100435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, J.C. Low-complexity QCA universal shift register design using multiplexer and D flip-flop based on electronic correlations. J. Supercomput. 2019, 76, 6438–6452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almatrood, A.; George, A.K.; Singh, H. Low-Power Multiplexer Structures Targeting Efficient QCA Nanotechnology Circuit Designs. Electronics 2021, 10, 1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadpour, S.S.; Mohammad, M.; Heikalabad, S.R. Efficient designs of quantum-dot cellular automata multiplexer and RAM with physical proof along with power analysis. J. Supercomput. 2022, 78, 1672–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahabi, M.; Rahimi, E.; Lyakhov, P.; Otsuki, A. A novel QCA circuit-switched network with power dissipation analysis for nano communication applications. Nano Commun. Netw. 2023, 35, 100438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, J.C. Multi-Layer QCA Shift Registers and Wiring Structure for LFSR in Stream Cipher with Low Energy Dissipation in Quantum Nanotechnology. Electronics 2023, 12, 4093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghosi, A.; Gholami, M.; Ghoreishi, S.S.; Adarang, H. Novel multiplexer, latch, and shift register in QCA nanotechnology for high-speed computing systems. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 2024, 139, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senthilnathan, S.; Kumaravel, S. Power-efficient implementation of pseudo-random number generator using quantum dot cellular automata-based D Flip Flop. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2020, 85, 106658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, D.-K.; Jeon, J.-C. QCA-Based Secure RAM Cell Structure Using Logic Transformation and Cell Interaction with Signal Reliability and Energy Dissipation in Quantum Computing. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 9998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walus, K.; Dysart, T.J.; Jullien, G.A.; Budiman, R.A. QCADesigner: A rapid design and simulation tool for quantum-dot cellular automata. IEEE Trans. Nanotechnol. 2004, 3, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qcadesigner-e. Available online: https://github.com/FSillT/QCADesigner-E (accessed on 21 May 2024).

- Liu, W.; Lu, L.; O’Neill, M.; Swartzlander, E.E. A First Step toward Cost Functions for Quantum-Dot Cellular Automata Designs. IEEE Trans. Nanotechnol. 2014, 12, 476–487. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).