Abstract

To achieve flexible sensing coverage with low deployment costs, mobile users need to contribute their equipment as sensors. Data integrity is one of the most fundamental security requirements and can be verified by digital signature techniques. In the mobile crowdsensing (MCS) environment, most sensors, such as smartphones, are resource-limited. Therefore, many traditional cryptographic algorithms that require complex computations cannot be efficiently implemented on these sensors. In this paper, we study the security of certificateless signatures, in particular, some constructions without pairing. We notice that there is no secure pairing-free certificateless signature scheme against the super adversary. We also find a potential attack that has not been fully addressed in previous studies. To handle these two issues, we propose a concrete secure construction that can withstand this attack. Our scheme does not rely on pairing operations and can be applied in scenarios where the devices’ resources are limited.

1. Introduction

Various mobile sensors are utilized in IoT devices to perform real-time data detection. These sensors capture sensitive information such as vehicle status, power system data, and personal health information, among others. Once collected, the data are transmitted to a central server for processing, making data security a critical consideration. To ensure data credibility and reliability, the use of digital signatures for integrity verification and message tracing is imperative for these sensing devices. Given the limited hardware resources of these devices, signature schemes with less complex pairing computations are preferred. Over the last few decades, the public key infrastructure/certificate authority (PKI/CA) system has been extensively employed. Within this system, upper layers issue certificates for lower layers, constructing a chain of trust from the trusted root to individual entities. However, many signature schemes reliant on the PKI/CA system introduce complex certificate management challenges, including distribution, update, and revocation, which are often financially burdensome for sensor devices.

Shamir [1] proposed identity-based cryptography (IBC) as a solution to eliminate the need for certificates. This approach allows users to directly generate their public keys from identity information, such as the IP. The private key generator (PKG) is responsible for holding the system master key and using it to generate all user’s private keys. By bypassing the need for certificates, IBC ensures the correctness of public key generation directly from identity information. Despite this advantage, the system’s security heavily relies on the PKG. Consequently, a key escrow problem arises, as every private key is generated by the PKG, who then has the capability to arbitrarily compromise the security of the scheme. Consequently, if the PKG is breached or lacks full trust, the safety of the entire system is compromised, leaving no user immune to potential security breaches.

Al-Riyami and Paterson [2] introduced certificateless public key cryptography (CLPKC) as a solution to the shortcomings of existing systems. In CLPKC, the key generation center (KGC) is responsible for controlling the master private key and differs from traditional PKI/CA systems in that it only generates a portion of the private key for users. Users must independently select and safeguard a secret value, using it to calculate both the complete private key and public key. As a result, the explicit binding of public keys and identity information through certificates is eliminated. Instead, the implicit binding of identity and public key occurs through the use of partial private keys, ensuring that only a valid user can generate a valid private key. Although KGC has ownership of the master private key, the secret values remain unknown. Consequently, CLPKC resolves the issue of key escrow in the IBC and eliminates the need for certificates in PKI/CA systems. Yet, the complexity and power of adversaries increase, posing new challenges. Consequently, there is ongoing research to comprehensively evaluate adversary capabilities and develop a fully secure CLPKC scheme.

1.1. Related Works

In 2003, Al-Riyami and Paterson [2] introduced the CLPKC system, which was based on the IBE scheme proposed by Boneh and Franklin [3] in 2001, and included an adversary model and security definition. However, their signature scheme was compromised by Huang et al. in 2005 [4]. Meanwhile, Yum and Lee developed general secure constructions for signature schemes (CLS) [5] and encryption schemes (CLE) [6] in 2004, which were constructed on a PKI/CA scheme and an IBC scheme. Despite this, subsequent work by Hu et al. [7] and Libert et al. [8] in 2006 demonstrated the insecurity of Yum and Lee’s general construction. In response to the threat posed by malicious KGC, Au et al. further fortified the security model of CLPKC in 2006 and determined that a class of schemes with the same key structure may be vulnerable under malicious KGC and unable to address key escrow issues [9]. Building on this, Huang et al. revisited the CLPKC security model in 2007, categorizing adversaries into three levels: Normal, Strong, and Super adversaries. In addition, they proposed a secure CLS scheme specifically designed to withstand super adversaries [10].

A number of CLPKC schemes have been proposed; they aim to address the limitations of pairing operations, which can be expensive and inefficient in lightweight equipment like mobile sensors. Baek et al. [11] introduced the first CLPKC scheme without pairing operations, using the Schnorr signature [12]. However, Sun et al. [13] identified some drawbacks in Baek’s approach and subsequently developed a new CLE scheme. Notably, Zhang and Mao [14] also devised a CLS scheme using the RSA signature. Despite this, Xu et al. [15] highlighted a flaw in the CLS scheme proposed by Gowri et al. [16], revealing that their signatures were susceptible to forgery. In response, Xu et al. [15] proposed a secure CLS scheme designed to withstand normal adversaries. Additionally, Karati et al. [17] developed a highly efficient CLS scheme by eliminating the map-to-point hash function, although Zhang et al. [18] later discovered that this scheme was vulnerable to breach through the replacement of the public key. Several other CLS schemes [19,20,21,22,23,24] were also proposed but were ultimately proven to be weak. More recently, Du et al. [25] and Xiang et al. [26] put forth two super-secure CLS schemes, but their security proofs were found to be incorrect, particularly with regard to the divisor always being calculated as zero when addressing underlying difficulties.

1.2. Motivations

In the CLS secure model, adversaries are categorized into two types. Type I adversaries have the capability to replace the public key with any string. In the security proof, the simulator must provide the correct signature in response to a signature inquiry, irrespective of whether the public key has been replaced. Not only that, the question arises of whether this signature should be valid before or after the replacement. Different levels of adversaries are defined by Huang based on this distinction, namely normal, strong, and super. The primary differentiator among these levels is the validity of the signatures they are able to obtain. A normal adversary may obtain a signature that is valid before the replacement, while a strong adversary may obtain a signature that is valid after the replacement, only if it supplies the corresponding secret values. On the other hand, a super adversary has the ability to replace the public key with a new key and receive a valid signature under the new key. In 2011, Huang introduced the first super security certificateless signature scheme using pairing. Subsequent works attempted to propose a secure CLS scheme without pairing, but the majority failed to achieve security against the super adversary.

Among the proposed pairing-free CLS schemes, the partial private key is typically calculated through Schnorr signature [12], which includes a random number R. It is important to note that this random number should be publicly available in the public key. Consequently, a adversary has the ability to query for a partial private key and replace the public key, and the order of these two operations is not limited. Furthermore, the presence of super adversaries introduces the potential for them to substitute the private key without providing the new secret value. This vulnerability becomes even more pronounced when the adversary first replaces the random number with a new one and then requests the new partial private key under the new number, rendering existing schemes unable to respond correctly without a new secret value. It is essential to recognize that this vulnerability has been previously overlooked in CLS schemes that do not involve pairing.

1.3. Contributions

- Under the ECDLP assumption, this paper proposes a secure CLS scheme without pairing. Our work includes completing the security proof against super adversaries in the ROM, as shown by [10].

- We fix the weakness that the simulator of the CLS scheme using Schnorr signatures could not answer partial private key queries after replacing the public key. Specifically, we adjusted the structure of the public key to partially restrict these queries

- Our signature scheme breaks away from pairing operations and the signature length is only two group elements, achieving a balance between computational efficiency and transmission costs.

1.4. Structure

2. Certificateless Signature Schemes

2.1. Construction

A CLS scheme usually involves three parties: the KGC, one user who signs a message, and another user who verifies the signature and consists of six algorithms:

- Setup(λ). KGC runs this algorithm with inputting security parameter . The final output is the system public parameters and the system master secret key . KGC publishes and keeps private.

- PartialPrivateKey(). KGC runs this algorithm with inputting , and a user identity . Then KGC must distribute the output as user partial private key securely.

- SecretValue(). A user runs this algorithm by inputting and . The final output serves as the secret value .

- PublicKey(). A user runs this algorithm with inputting , , and . The output serves as its public key and should be published.

- Sign(). A user runs this algorithm with inputting , a message m, ID, and . The output serves as the signature .

- Verify(). A user runs this algorithm with inputting , , , m and . Then it outputs “1” when validation is successful and otherwise outputs 0.

2.2. Security Models

We consider two types of super adversaries. The adversaries simulate external attackers who are allowed to replace public keys arbitrarily and get partial private keys and secret values by corrupting some users. The adversaries simulate the malicious KGC. They own the system master key but are not allowed to replace public keys. In this paper, we prove the security through two games, and the attack ability of adversaries is described by the access to the oracles. Specifically, the following five oracles will be considered.

- CreateUser(ID). This oracle will reply with a public key. When the ID is queried for the first time, the oracle generates a partial private key, a secret value, and a public key and records all information. It will reply according to records.

- PartialPrivateKeyExtract(ID). This oracle will reply with a partial private key. When the ID is queried for the first time, the oracle call Createuser(ID). It will reply according to the records.

- SecretValueExtract(ID). This oracle will reply with a secret value. When the ID is queried for the first time, the oracle calls Createuser(ID). It will reply according to the records.

- ReplacePublicKey(ID,PK’). This oracle will change the public key of in records. When the ID is queried for the first time, the oracle calls Createuser(ID). Then it changes the public key to in records.

- SuperSign(ID,m). The oracle will reply with a legal signature of a message m under the and in records. Note that the may have been replaced and there may be no secret value in records.

Game I: A challenger C interacts with a super adversary through Game I. C controls all the oracle and records the interactive information. The complete game processes are as follows:

Init. C runs and transmits to .

Query. can query for the above five oracles adaptively and C must respond correctly.

Forgery. finally outputs a signature , a message , and .

If the following equations hold, wins in Game I.

- has not asked for the partial private key of ,

- has not asked for a signature of the message under and ,

- The signature is valid, i.e.,

Game II: The challenger C interacts with a super adversary through game II. C controls all the oracle and records the interactive information. The complete game processes are as follows:

Init. C runs the algorithm and transmits both and to .

Query. can query for four oracles except for adaptively and C must respond correctly. does not need to ask as it knows .

Forgery. finally outputs a signature , a message , and .

If the following equations hold, wins in Game II.

- has not asked for the secret value of ,

- has not replaced the public key of ,

- has not asked for a signature of under and ,

- The signature is valid, i.e.,

3. Our CLS Scheme

3.1. Security Assumptions

Given an elliptic curve group G of a prime order q, a point P is a generator and another point Q is a random element. The Elliptic Curve Discrete Logarithm Problem (ECDLP) is to calculate which satisfies the equation . Our scheme is secure if the probability of solving the ECDLP is negligible for any probabilistic polynomial-time adversary.

3.2. Scheme Construction

There are six algorithms in our construction.

1. Setup(λ): Inputting a security parameters , KGC generates public parameters and master secret key . First, it randomly generates a prime number q of -bits and an elliptic curve group G of order q. It randomly picks a generator , a number and sets . It also selects the cryptography hash functions . Finally, KGC publishes and sets .

2. PartialPrivateKey(): When generating the partial private key for , KGC inputs , and . Then KGC randomly selects and calculates

The partial private key must be securely transmitted to the user, and its legality can be verified by calculating , and checking whether the equations , hold.

3. SecretValue(): With inputting and , the user randomly selects as the secret value.

4. PublicKey(): When generating the public key, the user inputs , , and . Then it calculates and sets public key .

5. Sign(): When signing a message m, the user inputs , m, , and . Then it selects random and calculates

The user sets as the signature.

6. Verify(): When verifying the legitimacy of a message-signature pair, the user inputs , m, , and . Then it calculates

and checks . Finally, it outputs “1” when validation is successful and otherwise outputs “0”.

4. Security Proof

Next, we demonstrate the security of our scheme against two super adversaries.

Theorem 1.

In the Random Oracle Model, assuming that ECDLP is difficult in the selected group G, our scheme is existentially unforgeable against super adversaries. This theorem can be obtained from the Lemmas 1 and 2.

Lemma 1.

Assuming that there exists a super Type-I adversary who can ()-win , then the ECDLP in G must be ()-solved.

Proof.

Given a ECDLP instance , we construct an algorithm to ()-calculate a solution by interacting with the adversary . □

are simulated as random oracle and maintains the tables to record the input and output corresponding to . The runs as follows.

Setup. randomly selects as the challenge identity, sets and publishes .

Query. can adaptively query to at any time and will response as follows.

- first checks whether exists in . If there is a record, returns . Otherwise randomly selects , returns and insert into .

- Suppose queries for at most times. It maintains a list and sets a in to record whether the in the public key has been replaced. returns the public key according to the record if is found in the list . Otherwise,

- –

- If , randomly selects , calculates , and sets , calculates and sets , . Then it returns and inserts into the table .

- –

- If , randomly selects , calculates and sets . Then return and insert into the table .

- . Suppose queries this oracle for at most times.

- –

- If , abort the game.

- –

- Otherwise, searches the table for . If is found and , return d according to the record directly. If is found while the , checks whether the public key is legal by , . If the public key is still valid, we use the forking lemma on to get a new that satisfies . Then we can get , and is the solution to the ECDLP instance. If the public key is invalid, we return nothing. In addition, if is not found, call and then return .

- –

- If , abort the game.

- –

- Otherwise, searches the table for . If is found , returns according to the record directly. If is found while the public key has been replaced without providing , returns nothing. If is not found, calls and returns .

- searches the table to find . If is found, it replaces with . Otherwise, calls and replaces with . sets .

- –

- If or , randomly selects and calculates Then set , , in . is valid signature forand note that does not need to know x,

- –

- If and , searches the table to find . If is found, get . Then randomly selects and sets , , in . Finally calculates . is a valid signature.

Forgery. In the end, outputs . If , aborts. Otherwise, searches the table to find and verifies the signature:

If , we use the forking lemma on to get a new output . These outputs satisfy so that can calculate . If R is not replaced, owns r and calculates . s is the solution to the ECDLP instance. If , we do the same as in to get s.

will solve the ECDLP if the following events occur:

- : never aborts in ,

- : generates a valid forgery ,

- : In the forgery,

So the probability of is .

will abort in the if extracts the partial private key for any user. So . If does not abort in the , generates a valid forgery with . So . As the is selected randomly, . So the probability is .

Lemma 2.

Assuming that there exists a super Type-II adversary who can ()-win , then the ECDLP must be ()-solved.

Proof.

Given a ECDLP instance , we construct an algorithm to ()-calculate a solution by interacting with the adversary . □

are simulated as random oracle and maintains the tables to record the input and output corresponding to . The runs as follows.

Setup. randomly selects as the challenge identity and as the . Then calculate and public .

Query. can adaptively query to at any time and will response as follows.

- . first checks whether exists in . If there is a record, returns . Otherwise randomly selects , returns and inserts into

- . Suppose it queries for at most times. maintains a list and sets a in to record whether the public key has been replaced. returns the public key if is in the list. Otherwise,

- –

- If , randomly selects , calculates and sets . Then it publishes the public key and inserts into the table .

- –

- If , randomly selects , calculates and sets . Then it publishes the public key and inserts into the table .

- . Owning the , can arbitrarily finish this query for any .

- . Suppose it queries for at most times.

- –

- If , abort the game.

- –

- Otherwise, searches the table for .If is found, it returns x directly. Otherwise, it calls and returns x.

- . Suppose it queries for at most times.

- –

- If , abort the game.

- –

- Otherwise, searches the table for . If is found, it replaces with . Otherwise, calls , replaces with and sets .

- .

- –

- If or , randomly selects and calculates . Then sets , , in . is a valid signature and note that does not need to know x.

- –

- If and , searches the table to find . If is found, knows . Otherwise, calls and gets for . Then randomly selects and sets , , in . Finally calculates . is valid signature.

- . In the end, outputs . If , aborts. Otherwise, searches the table to find and verifies the signature as follows:

Use forking lemma on to get a new so that . Then calculate is the solution to the ECDLP.

will solve the ECDLP if the following events occur:

- : never aborts in the ,

- : generates a valid forgery ,

- : In the forgery,

So the probability of is .

will abort in the if extracts the secret value or replaces the public key for the user . So . If does not abort in the , generates a valid forgery with . So . As the is selected randomly, . So the probability is .

5. Efficiency Analysis

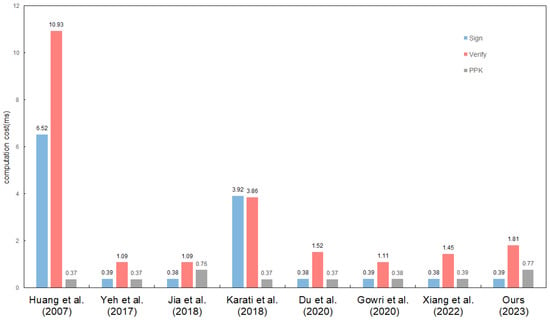

We analyze the efficiency and security of our CLS scheme and compare it with a series of schemes. Among these schemes, Huang et al. [10] designed a secure CLS scheme against super adversaries but relies on pairing. All other solutions do not require pairing and can not be proven to be safe against the super adversary. We conduct simulation experiments in the environment in Table 1 and choose a type-D pairing which is discovered by [27] and constructed on the curve over the field for a 160-bit prime q. So the length of a point x-coordinate in is roughly the same as 160-bit. The embedding degree is 6 so that the size of finite field in and is 960-bit. The notations and time of different operations are shown in Table 2. The theoretical analysis of all schemes is shown in Table 3. Here and denote the element size in and . To make Table 3 clearer, we ignore the insignificant time of and . The time of different schemes is shown in the Figure 1.

Table 1.

Experiment Environment.

Table 2.

Notation and time of the group operation.

Table 3.

Theoretical Analysis.

Figure 1.

The time of , and algorithms [10,16,17,24,25,26,28].

It has been observed that several secure certificateless signature schemes have been introduced without utilizing pairing, yet none of them were able to be proven secure against super adversaries. Some of the schemes, which are based on the Schnorr signature, are unable to respond to the super adversary’s query when requesting specific private keys after the replacement of the public key. Our proposed solution not only attains security against super adversaries but also rectifies this minor issue, all the while maintaining a reasonable level of efficiency in signing and verifying. While Huang’s scheme also achieves security against super adversaries, it relies on pairing operations, leading to increased computational time and signature size compared to our scheme. Consequently, our scheme effectively enhances both security and efficiency, while also addressing a slight deficiency in the security model.

6. Conclusions

We find that existing secure CLS schemes against super adversaries often require expensive pairing operations, making them unsuitable for lightweight equipment. Some pairing-free schemes are unable to resist super adversaries and suffer from the issue where the challenger cannot answer partial private key inquiries after replacing the public key. To address these limitations, we have developed a secure CLS scheme against super adversaries without relying on pairing operations, and we have provided comprehensive proof of its security. Experimental testing has demonstrated that our scheme exhibits superior computational efficiency and a smaller signature size compared to schemes offering similar security guarantees.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.W. (Ge Wu); Validation, L.C.; Formal analysis, J.H.; Resources, L.C.; Writing—original draft, G.W. (Guilin Wang); Writing—review & editing, H.S.; Supervision, G.W. (Ge Wu); Project administration, G.W. (Ge Wu). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 62002058), Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (No. BK20200391), and Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (No. 2242021R40011).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the anonymous reviewers of this paper for their valuable comments and suggestions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Shamir, A. Identity-Based Cryptosystems and Signature Schemes. In Proceedings of the Advances in Cryptology, Proceedings of CRYPTO ’84, Santa Barbara, CA, USA, 19–22 August 1984; Blakley, G.R., Chaum, D., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1984; Volume 196, pp. 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Riyami, S.S.; Paterson, K.G. Certificateless Public Key Cryptography. In Proceedings of the Advances in Cryptology—ASIACRYPT 2003, 9th International Conference on the Theory and Application of Cryptology and Information Security, Taipei, Taiwan, 30 November–4 December 2003; Laih, C., Ed.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2003; Volume 2894, pp. 452–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boneh, D.; Franklin, M.K. Identity-Based Encryption from the Weil Pairing. In Proceedings of the Advances in Cryptology—CRYPTO 2001, 21st Annual International Cryptology Conference, Santa Barbara, CA, USA, 19–23 August 2001; Kilian, J., Ed.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2001; Volume 2139, pp. 213–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Susilo, W.; Mu, Y.; Zhang, F. On the Security of Certificateless Signature Schemes from Asiacrypt 2003. In Proceedings of the Cryptology and Network Security, 4th International Conference, CANS 2005, Xiamen, China, 14–16 December 2005; Desmedt, Y., Wang, H., Mu, Y., Li, Y., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005; Volume 3810, pp. 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yum, D.H.; Lee, P.J. Generic Construction of Certificateless Signature. In Proceedings of the Information Security and Privacy: 9th Australasian Conference, ACISP 2004, Sydney, Australia, 13–15 July 2004; Wang, H., Pieprzyk, J., Varadharajan, V., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2004; Volume 3108, pp. 200–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yum, D.H.; Lee, P.J. Generic Construction of Certificateless Encryption. In Proceedings of the Computational Science and Its Applications—ICCSA 2004, International Conference, Assisi, Italy, 14–17 May 2004; Proceedings, Part I. Laganà, A., Gavrilova, M.L., Kumar, V., Mun, Y., Tan, C.J.K., Gervasi, O., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2004; Volume 3043, pp. 802–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.C.; Wong, D.S.; Zhang, Z.; Deng, X. Key Replacement Attack Against a Generic Construction of Certificateless Signature. In Proceedings of the Information Security and Privacy, 11th Australasian Conference, ACISP 2006, Melbourne, Australia, 3–5 July 2006; Batten, L.M., Safavi-Naini, R., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006; Volume 4058, pp. 235–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libert, B.; Quisquater, J. On Constructing Certificateless Cryptosystems from Identity Based Encryption. In Proceedings of the Public Key Cryptography—PKC 2006, 9th International Conference on Theory and Practice of Public-Key Cryptography, New York, NY, USA, 24–26 April 2006; Yung, M., Dodis, Y., Kiayias, A., Malkin, T., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006; Volume 3958, pp. 474–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Au, M.H.; Chen, J.; Liu, J.K.; Mu, Y.; Wong, D.S.; Yang, G. Malicious KGC Attacks in Certificateless Cryptography. IACR Cryptol. Eprint Arch. 2006, 255. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, X.; Mu, Y.; Susilo, W.; Wong, D.S.; Wu, W. Certificateless signature revisited. In Proceedings of the Information Security and Privacy: 12th Australasian Conference, ACISP 2007, Townsville, Australia, 2–4 July 2007; Proceedings 12. Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007; pp. 308–322. [Google Scholar]

- Baek, J.; Safavi-Naini, R.; Susilo, W. Certificateless Public Key Encryption Without Pairing. In Proceedings of the Information Security, 8th International Conference, ISC 2005, Singapore, 20–23 September 2005; Zhou, J., López, J., Deng, R.H., Bao, F., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005; Volume 3650, pp. 134–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnorr, C.P. Efficient identification and signatures for smart cards. In Proceedings of the Advances in Cryptology—CRYPTO’89 Proceedings 9, Santa Barbara, CA, USA, 11–15 August 1990; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1990; pp. 239–252. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y.; Zhang, F.; Baek, J. Strongly Secure Certificateless Public Key Encryption Without Pairing. In Proceedings of the Cryptology and Network Security, 6th International Conference, CANS 2007, Singapore, 8–10 December 2007; Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Bao, F., Ling, S., Okamoto, T., Wang, H., Xing, C., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007; Volume 4856, pp. 194–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Mao, J. An efficient RSA-based certificateless signature scheme. J. Syst. Softw. 2012, 85, 638–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Luo, M.; Khan, M.K.; Choo, K.R.; He, D. Analysis and Improvement of a Certificateless Signature Scheme for Resource-Constrained Scenarios. IEEE Commun. Lett. 2021, 25, 1074–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gowri, T.; Rao, G.S.; Reddy, P.V.; Gayathri, N.B.; Reddy, D.V.R.K. Efficient Pairing-Free Certificateless Signature Scheme for Secure Communication in Resource-Constrained Devices. IEEE Commun. Lett. 2020, 24, 1641–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karati, A.; Islam, S.H.; Biswas, G.P. A pairing-free and provably secure certificateless signature scheme. Inf. Sci. 2018, 450, 378–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Zhu, T.; Hu, C.; Zhao, C. Cryptanalysis of a Lightweight Certificateless Signature Scheme for IIOT Environments. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 73885–73894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Chen, K.; Long, Y.; Wang, H. An efficient pairing-free certificateless signature scheme for resource-limited systems. Sci. China Inf. Sci. 2017, 60, 119102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, P.; Li, P. Further improvement of a certificateless signature scheme without pairing. Int. J. Commun. Syst. 2014, 27, 2083–2091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Chen, K.; Long, Y.; Mao, X.; Wang, H. A Modified Efficient Certificateless Signature Scheme without Bilinear Pairings. In Proceedings of the 2015 International Conference on Intelligent Networking and Collaborative Systems, INCoS 2015, Taipei, Taiwan, 2–4 September 2015; Xhafa, F., Barolli, L., Eds.; IEEE: Piscataway Township, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 82–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, K.; Tsai, K.; Kuo, R.; Wu, T. Robust Certificateless Signature Scheme without Bilinear Pairings. In Proceedings of the 2013 International Conference on IT Convergence and Security, ICITCS 2013, Macau, China, 16–18 December 2013; IEEE Computer Society: Piscataway Township, NJ, USA, 2013; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, K.; Tsai, K.; Fan, C. An efficient certificateless signature scheme without bilinear pairings. Multim. Tools Appl. 2015, 74, 6519–6530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.; He, D.; Liu, Q.; Choo, K.R. An efficient provably-secure certificateless signature scheme for Internet-of-Things deployment. Hoc Netw. 2018, 71, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H.; Wen, Q.; Zhang, S.; Gao, M. A new provably secure certificateless signature scheme for Internet of Things. Hoc Netw. 2020, 100, 102074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, D.; Li, X.; Gao, J.; Zhang, X. A secure and efficient certificateless signature scheme for Internet of Things. Hoc Netw. 2022, 124, 102702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Member, A.M.; Nakabayashi, M.; Nonmembers, S.T. New Explicit Conditions of Elliptic Curve Traces for FR-Reduction. Tech. Rep. Ieice Isec 2001, 100, 1234–1243. [Google Scholar]

- Yeh, K.; Su, C.; Choo, K.R.; Chiu, W. A Novel Certificateless Signature Scheme for Smart Objects in the Internet-of-Things. Sensors 2017, 17, 1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).