Abstract

Separation anxiety disorder (SAD) is a prevalent psychological disorder among preschoolers, characterized by excessive fear or anxiety related to separation from a primary attachment figure. The COVID-19 pandemic likely exacerbated the problem due to the transition to online schooling. While some attention has been given to treating SAD, most current solutions are non-technical and based on behavior analytic research which can be costly and time-consuming. Mediated social touch, which uses technology to simulate physical touch and deliver it remotely, has been extensively studied for its potential to promote wellbeing, enhance social connectedness, and improve affective experiences in various contexts. However, no research has focused on the use of such technology to manage SAD in preschoolers. To address this gap, this work presents the design, development, and evaluation of a novel mediated social touch system aimed at managing separation anxiety in preschoolers. Specifically, the study investigates the effectiveness of using IoT in huggable interfaces and game-based applications in improving children’s emotional state and adaptation to the kindergarten environment. Through experiments conducted on a sample of nearly 30 preschoolers, the results have shown that the system is effective in helping preschoolers adapt to kindergarten, with the best results achieved when using the huggable interface and the developed game together. The implications of this study may be beneficial to parents, educators, and mental health professionals who work with preschoolers who experience SAD.

1. Introduction

Preschoolers aged between three to five years spend a significant amount of time at kindergarten, often surpassing the time they spend with their families and relatives. Therefore, it is crucial to ensure that the kindergarten environment is attractive and comfortable for them. However, children may face challenges in adapting to kindergarten, especially during the first few days or after a long vacation. If this situation is not effectively addressed, it may lead to psychological problems such as separation anxiety disorder, depression, panic attacks, generalized anxiety, and other emotional or behavioral disorders [1].

Among these, separation anxiety disorder (SAD) is particularly common among preschoolers, with about 4–10% of children experiencing it [2]. This disorder can be defined as excessive distress at being separated from those to whom the child is attached [3]. SAD can have several adverse effects, with over 90% of children suffering from at least one sleep problem [4]. Moreover, it affects not only the children but also their parents [5]. If left unaddressed, separation anxiety may persist into adulthood, leading to mental disorders [1]. Furthermore, it carries significant economic costs, with families having to spend 21 times more money on a child with separation anxiety than families without such a case [6].

Several factors contribute to the probability of separation anxiety, with extreme parent–child attachment being one of the most significant challenges to the child’s adaptation to the kindergarten environment [7]. During the COVID-19 pandemic, separation anxiety became even more prevalent in children as they spent most of their time indoors with their families with limited social interaction with the outside world [8].

While some attention has been given to treating separation anxiety disorder, limited research has focused on investigating the causes and prevention of SAD [9]. Early prevention is crucial because children may develop separation anxiety disorder after experiencing anxiety for four weeks [5,10]. However, most current studies focus on non-technological solutions and very few have addressed the management of separation anxiety disorder in preschoolers.

Therefore, the purpose of this work is to design, develop, and evaluate a novel mediated social touch system aimed at managing separation anxiety in preschoolers. Specifically, the objective of the study is to investigate the effectiveness of using IoT in huggable interfaces and game-based applications in improving children’s emotional state and adaptation to the kindergarten environment. Our solution capitalizes on the significance of touch as an emotional interaction medium [11,12,13], especially in remote relationships.

To address this challenge, we developed a mediated touch that allows children to maintain interaction remotely. By combining a huggable interface and tablet game application, we provide a comprehensive solution that helps preschoolers cope with separation anxiety and enhances their adaptation to the kindergarten environment. The prototype, which we called “Latif”, is a multimodal huggable interface that is equipped with a heat distributor, speakers, and LED lights that simulate hugging and playing. In addition to the huggable interface, we developed a tablet game application that targets Arabic-speaking preschoolers and tells an interactive story about a young bear named “Latif” to help manage separation anxiety disorder. The game revolves around a young bear named ‘Latif’. The game focuses on enhancing the child’s social, cognitive, and emotional abilities. It comprises four stories, each presenting a challenge for the child to overcome and achieve a sense of winning. The stories also incorporate principles such as relaxation exercises, emotion recognition, decision making, and social interaction. Through this solution, we aim to combine the positive impact of various technologies and approaches to address the issue of separation anxiety in young children during their initial days in kindergarten.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows: Section 2 provides background and related works on SAD. Section 3 presents the methodology used in this study including the system design and development and experimental procedures. Section 4 presents the analysis and results of the study. Section 5 discusses the interpretation of the findings in light of previous research, the strengths and limitations of the study, and the implications for future research and practice. Finally, Section 6 provides a conclusion summarizing the study’s findings.

2. Background and Related Works

2.1. Non-Technical Interventions for SAD

Several non-technical interventions have been investigated for the treatment of separation anxiety disorder in children. Herren et al. [14] examined the relationship between children with separation anxiety disorder and their parents’ beliefs. The results showed that parents of children with separation anxiety disorder experienced lower parenting self-efficacy and satisfaction compared to parents of healthy children.

In another study, Dozva [15] analyzed the strategies used by preschool caregivers in Chitungwiza daycare centers to manage separation anxiety in young children. The study found that showing acceptance towards children with separation anxiety and providing them with toys were among the most effective strategies used by caregivers. It also highlighted the importance of parental involvement in helping children adapt to the school or kindergarten environment.

Moreover, to help children adjust to the school or kindergarten environment, researchers in [16] emphasized the importance of parental involvement. The study suggested that parents should take their children on a tour of the school, meet the teacher before school starts, and gradually decrease the time they spend with their child until the child becomes comfortable entering kindergarten alone.

A study by Shouldice [17] investigated the impact of separation anxiety disorder on children’s attachment models. The study involved an experiment conducted on children aged four and a half years old which analyzed their reactions to separation and the way they reunited with their parents. The results showed that children with separation anxiety disorder had a profound impact on their attachment models.

To help children with separation anxiety disorder overcome their condition, group play therapy was found to be effective in reducing children’s anxiety, as demonstrated by a study by Shoakazemi et al. [18]. The study evaluated the effectiveness of group play therapy on 20 children aged 7 to 9 years in Tehran and found that it had a significant impact on reducing their separation anxiety.

Parent–child interaction therapy (PCIT) has also been identified as an effective intervention for children with separation anxiety disorder. Researchers, such as in [19,20], have evaluated the effectiveness of tailored PCIT in treating young children with separation anxiety disorder. Both studies found that PCIT helped anxious parents change and improve their interactions with their children which ultimately reduced the children’s anxiety.

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) has also been identified as an effective treatment for children who refuse to go to school due to separation anxiety disorder. Studies, such as that by King et al. [21] evaluated the efficacy of CBT in treating children’s anxiety and found that it was an effective intervention.

Finally, a study by Barrett et al. [22] evaluated the benefits of merging parent training programs with CBT for children with separation anxiety disorder. The study found that the combination of family management and CBT was effective in treating separation anxiety disorder in children aged 7 to 14 years.

In summary, several studies were conducted to investigate and evaluate interventions for the treatment of separation anxiety disorder in children. These studies have highlighted the importance of parental involvement, effective communication between parents and children, and the use of evidence-based interventions such as play therapy, PCIT, and CBT to manage separation anxiety in children. Such research underscores the need for a comprehensive and multi-disciplinary approach to addressing separation anxiety disorder in young children. By building on the insights gained from these studies, innovative solutions such as the multimodal huggable interface and game-based application developed in our work can help children cope with separation anxiety and promote their adaptation to the kindergarten environment.

Table 1 provides a summary of the studies conducted on non-technical interventions for separation anxiety disorder in children.

Table 1.

Summary of studies on non-technical interventions for separation anxiety disorder in children.

2.2. Mediated Social Touch: Huggable and Non-Huggable Interfaces

Mediated social touch refers to the use of technology to simulate physical touch and deliver it remotely [23]. Mediated social touch can be delivered through various types of interfaces including huggable and non-huggable interfaces. Studies have investigated the effectiveness of these interfaces for various purposes such as promoting social connectedness, enhancing affective experiences, and improving wellbeing in various contexts. For example, Haans et al. [24] conducted a study to explore the effectiveness of a system consisting of an input device, an output device, and a software component to deliver mediated social touch. They found that touch has a positive effect on the recipient’s affective experience and that combining touch and vision can increase physiological excitement and a sense of telepresence. Similarly, HaptiHug [25], a non-huggable interface designed to simulate touch in electronic games, proved effective in increasing participants’ relaxation and sense of being hugged.

Authors in [26] developed a wearable pajama to enable hugging communication between children and their parents remotely. The pajama provides a virtual hug sensation to the child, enhancing the feeling of being hugged by their parents.

Nunez et al. [27] proposed a cushion as a huggable interface to deliver a sense of touch remotely. The cushion senses the user’s hug using a hug sensor, transfers it as a message to a paired interface, and delivers on–off signals using cues made of colored lights and vibration. In a study comparing cushion-type communication interfaces and touch screen type communication interfaces, the participants reported feeling a real touch of the other while sending the message by hugging the cushion which resulted in a stronger feeling of social connectedness between them.

Hugvie [28] is a device designed to facilitate close relationships between individuals during remote communication. The device features a pocket in the head to insert a mobile phone during the call. To test their hypothesis, researchers conducted an experiment with two participants using Hugvie and a Bluetooth headset in two different settings. The results indicated that using Hugvie enhanced the presence of the second person and increased the feeling of being loved by the other person.

Nakanishi et al. [29] tested two hypotheses related to using a huggable communication medium with special needs students: first, they investigated whether it could improve the memory of listeners and second they investigated if a longer trial period would yield better results. They conducted a three-month study on special needs students, dividing them into two groups where one group listened to their teachers in a normal way and the other used Hugvie. The group using Hugvie achieved better results as it improved memory test scores related to information provided by teachers to their students.

Takahashi et al. [30] demonstrated the effectiveness of Hugvie in enhancing trust between players during conversation games. In another study by researchers [31], Hugvie was used as a huggable interface to test the hypothesis that using such an interface during remote communication would improve impressions about hearsay information of a third person. The study compared the effects of using a Bluetooth speaker and Hugvie and the results confirmed the hypothesis as the huggable interface (Hugvie) reduced negative inferences about the third person during the call.

Pepita [32], a huggable robot designed to sense and convey affective expressions, was used in an experiment involving fourteen participants. While the robot’s simple appearance without arms was acceptable, it was suggested that improving Pepita’s appearance to resemble more familiar huggable objects, such as animals or cushions, would be beneficial.

Jeong et al. [33] conducted research to investigate the impact of embodiment on promoting socio-emotional interactions among young children and to determine which of the huggable interfaces is the most effective in improving children’s wellbeing in hospitals. The study compared the impact of a teddy bear plush, a virtual agent, and a social robot on children’s wellbeing. The results revealed that a teddy bear could help children participate in social interactions and could increase their feeling of comfort while hugging it.

In addition, Lali [34] is a tangible interface designed to allow kids to lengthen their playtime through remote–virtual coupling. An experiment conducted on children under five years showed that preschoolers above three years enjoyed playing with this doll.

Teddy bear huggable interfaces are often preferred by children and were developed as embodied mock-ups to enable remote hugging between young children (4–6 years) and their parents based on vibration, presence indication, and communication of gestures [35]. The study aimed to enhance children–parent communication in case of a parent traveling. The results showed that if the device used by children was too technical, the children could not comprehend its symbolic interaction [35].

Furthermore, the study in [36] explored the potential of haptic technology as a non-pharmacological intervention for anxiety. The authors described a novel huggable haptic interface that pneumatically simulates slow breathing and demonstrated its effectiveness at reducing pre-test anxiety compared to a control condition and the fact that it is indistinguishable from a guided meditation in a mixed-design experiment. The authors suggest that haptic technologies can be effective at easing anxiety and should be explored further to capture the nuances of different modalities in relation to specific situations and trait characteristics. Table 2 compares huggable and non-huggable technologies, including the author, motivation, audience, technology type, shape, and result of each study.

Table 2.

Comparison between existing non-huggable technologies.

2.3. Game-Based Training

Game-based training is a popular approach to engage children in learning and problem-solving activities [37]. Electronic games can be used as tools to improve children’s abilities or to solve some problems they suffer from in the context of game-based training. For instance, in [38], researchers found that interactive game-based learning improved cognitive development and body movement in preschoolers. Their system, “The Goalkeeper”, taught six colors and names in English through gestures. The experiment showed that the game-based group outperformed the traditional group in both performance and motor skills.

In addition to improving children’s cognitive abilities, game-based applications can also enhance language learning for preschoolers. Authors in [39] developed a mobile application game to improve preschoolers’ alphabetical sound articulation in Tanzania. The game-based learning system was designed to address the challenges faced by preschoolers in articulating sounds more efficiently.

The benefits of game-based applications are not limited to education but they can also be used as a tool to diagnose neurological disorders in young children [40]. Researchers developed the computer game DIESEL-X to detect high-risk dyslexia among preschoolers, which children preferred over traditional tests, making data collection more accessible.

Moreover, an innovative solution for managing children’s dental anxiety through the use of augmented reality (AR), virtual reality (VR) technologies, and game-based application was proposed in [41]. The proposed system targets Arabic-speaking children between 7 to 10 years old and familiarizes them with dental settings and procedures in a simple, attractive, and age-appropriate way. The system’s performance was evaluated using various testing methods and a feasibility study with 16 children showed a decrease in dental anxiety levels after using the system.

Preschoolers may experience anxiety related to the study process or media exposure. One study [42] focused on solving mathematics anxiety in preschoolers, comparing the game platforms Kodu, Unity 3D, and Construct 2 to find the most suitable platform for counting games. The study found that Kodu and Unity 3D were best suited for 3D environments. Meanwhile, Ref. [43] developed an interactive game called “Tony’s Nightmare” to reduce media-induced anxiety in children. The game features a character named Tony who overcomes his fears in his dreams. However, the game’s success was limited due to falsified data in the questionnaire filled out by the children’s parents.

In [44], the effectiveness of 3D educational computer games on reducing test anxiety and improving exam performance was evaluated and compared to traditional methods. The game-based application method resulted in significantly better exam performance. Meanwhile, Ref. [45] investigated the impact of anxiety levels on learners’ gaming and learning performance in the context of digital game-based learning. The researchers integrated English learning components with game tasks and found that digital game-based learning was beneficial for learners with high anxiety levels, improving both their gaming and learning performance.

Table 3 summarizes the game-based training applications discussed in this section. Overall, game-based training has the potential to engage children in learning activities and improve their cognitive, motor, and language skills as well as to diagnose neurological disorders and reduce anxiety levels.

Table 3.

Overview of game-based training applications.

Upon reviewing the literature, it was observed that there was limited research on developing solutions that address the adaptability of children during their first days in kindergarten, particularly in the context of separation anxiety. Most of the previous studies on separation anxiety focused on non-technological solutions. To our knowledge, there are no studies that specifically address the adaptability of young children during their first days in kindergarten and its impact on separation anxiety. Additionally, we did not identify any game-based applications in Arabic that were developed to manage separation anxiety in children during their initial days in kindergarten.

Given the gap in the literature, our study focused on developing a solution to help preschoolers adjust to their first days in kindergarten. We aimed to combine the positive impact of recorded maternal voices and tablet computer games with a huggable interface to improve children’s adaptability and reduce separation anxiety. Our approach includes the following key features that distinguish it from previous studies:

- -

- Developing a mediated social touch solution, the Latif Teddy Bear huggable interface, which produces heat, activates a speaker, and allows children to engage in color play. Parents can control this teddy bear remotely using a special application. The aim of this interface is to help children feel more comfortable and positively affect their adaptability and separation anxiety probability;

- -

- Developing a game-based application in Arabic that specifically targets the adaptability of children in kindergarten.

In conclusion, through this solution we aimed to combine the positive impact of different technologies and approaches to address the issue of separation anxiety in young children during their first days in kindergarten.

3. Materials and Methods

Our methodology consists of three phases which are focused on developing and evaluating a huggable interface for managing anxiety in children. The first phase involves building the huggable interface, which takes the form of a teddy bear named “Latif” لطيف. The name “Latif” is an Arabic word that means kind and friendly, reflecting our intention to create a non-threatening and comforting object for children. The second phase focuses on the design and development of a game that can be played with the huggable interface. The game is designed to be simple and intuitive, with the aim of engaging children through a relaxing and enjoyable activity. The game design is informed by principles of gamification, including the use of rewards and feedback, to encourage continued engagement. The third and last phase involves the design and conduct of an experiment to evaluate the effectiveness of the huggable interface and game in reducing anxiety in children. Throughout the methodology, implementation and evaluation are also considered.

3.1. Technological Support of the Study

The huggable interface and game were developed using a carefully selected set of software tools chosen for their flexibility, ease of use, and comprehensive feature sets. These tools were instrumental in bringing the project to life and enabled the team to create a robust and functional system.

- Android Studio: Android Studio is an Integrated Development Environment (IDE) used for Android app development. It is based on IntelliJ IDEA [46] and allows developers to create Android apps using the Java programming language [47]. Android Studio also supports Firebase which is crucial for real-time data processing and enables us to receive parent’s actions and remotely activate the speaker, lights, and heater on our huggable interface (Latif) simultaneously;

- Arduino: The Arduino Integrated Development Environment (IDE) is an open-source electronics platform that supports C and C++ programming languages [48]. It allows developers to upload programs to Arduino hardware [49]. Over time, the Arduino board has evolved to meet new requirements, from simple 8-bit boards to products that can be used with the Internet of Things, wearable sensors, and even 3D printing [48];

- Unity 3D: Unity 3D [50] is a popular game engine that allows developers to create both 2D and 3D games. It supports the C# programming language and provides powerful animation tools for developers to animate various game elements. Being a cross-platform tool means that games developed using Unity can be displayed on any platform.

3.2. Building the Latif Huggable Interface and Its Application

This section describes the process of building the Latif huggable interface and its accompanying Android application. The section is broken down into three subsections: prototype overview, apparatus, and development steps.

3.2.1. Overview

The aim of Latif is to provide a comforting and interactive object for children, with various features such as heat, sound, and a colors game. To build the Latif huggable interface and application, we followed a series of steps to ensure that the system was functional and met the project’s requirements. The huggable interface was designed with three main functions: light selection, heater slices, and a speaker and was built using a variety of electronic components. The Android application we developed enabled parents to control the Latif huggable interface remotely, making their children feel as if they were close to their parents. The development of the prototype involves the careful consideration of various factors, including safety, comfort, and functionality. To produce heat, the prototype uses heat slices as the heating element with the recommended temperature range for young children being between 32–33 °C based on previous studies [51,52] on swimming pool temperatures for young children.

3.2.2. Apparatus

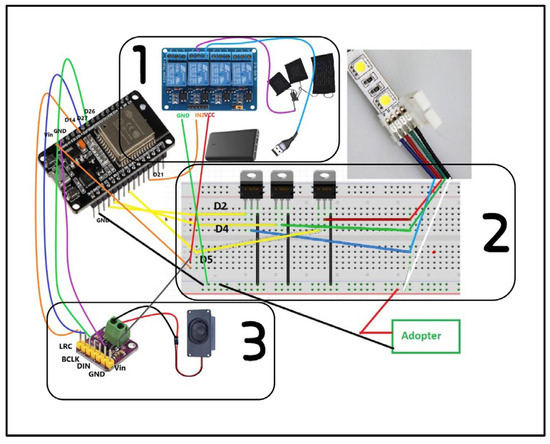

The huggable interface was built using a carefully selected set of electronic components chosen for their compatibility with the system and performance. To provide a visual representation of the components and their connections, Figure 1 shows the circuit diagram of the Latif huggable interface where each component is labeled with a number corresponding to its description. Additionally, Table 4 provides a summary of the main components used in the project, including the ESP32 controller, relay board, heater, power bank, breadboard, TIP120 transistor, amplifier, and speaker.

Figure 1.

Circuit diagram of the Latif huggable interface. The diagram shows the connections between the various electronic components used in the system, including the ESP32 controller, relay board, heater, power bank, breadboard, TIP120 transistor, amplifier, and speaker.

Table 4.

Apparatus used in the development of the huggable interface.

3.2.3. Development Steps

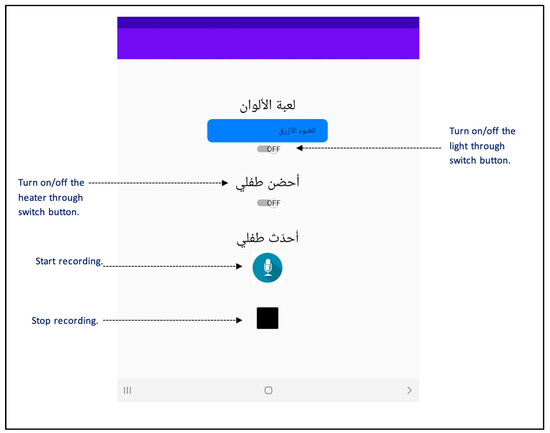

To develop the Latif huggable interface and application we followed several steps. The huggable interface is designed with three main functions, including light selection, heater slices, and a speaker, as shown in Figure 2. The light selection is located on Latif’s ID card (#1) and can be red, green, or blue depending on the parent’s selection of colors for the game app that parents will play with their children remotely. The heater slices are located inside the pockets in the front and back of Latif and produce heat when the heater button is pressed (#2–5). The speaker (#6) is located at the back of Latif’s head and lets the child hear their parent’s voice when they press the microphone button in the app. The huggable interface is designed to be soft and cuddly, making it comfortable for children to hug.

Figure 2.

The huggable interface with the light selection (1), heater slices (2–5), and speaker (6).

The Android application we developed enables parents to control the Latif huggable interface remotely, making their children feel as if they are close to their parents. The main user of the huggable interface application is the child’s parent who controls the hardware through the application buttons. The application provides three main actions that the parent can control: light selection, heater slices, and the speaker. The user interface was designed to be intuitive and easy to use with clear labels and buttons. Figure 3 shows the main page of the application which includes a drop-down list with three color options and a switch button. The parent can select any of these colors to turn it on or off using the switch button below the list. When the parent selects a color, the light in Latif’s ID card turns on with the selected color, as shown in Figure 4. This feature is used when the parent wants to play the colors game with their child and they can name the color using the microphone and turn it on so that the lights in the child’s place turn on, making the child feel as if the parent is close to them.

Figure 3.

Main page of the huggable interface application.

Figure 4.

The huggable interface ID card with light selection.

Another action available in the huggable interface application is the “I hug my child” feature. The parent can turn it on through the switch button and in response the heater slices produce heat. When the child hugs Latif and listens to their parent’s voice at the same time, they feel as if they are really hugging their parents.

Finally, the parent can press the microphone button located at the bottom of the interface to say something that may comfort their child, such as naming the light’s color in the colors game or even asking the child to hug Latif. The recording stops when the parent presses the black square below it and in response the speaker located at Latif’s head plays the recorded voice, allowing the child to hear their parent’s voice.

3.3. Game Design and Development

3.3.1. Design Considerations for Developing Applications for Children

Developing applications differs according to the audience. Design principles for young children are different from those for adults. When developing an application for young children, the designer should take into consideration that it would improve the children’s physical, socio-affective, and cognitive abilities [53]. Since children in our society use various types of electronic devices such as computers, mobile phones, or tablets at a very young age, it is important for developers to follow some guidelines regarding the age-specifications of children.

When developing children’s applications, one of the important ethical issues entails focusing on protecting the child’s privacy. This implies preventing access to children via videos or reaching any other types of data that threaten them [54]. It is essential to create a challenge in the game application developed for preschoolers that provides a sense of winning when they play, allows them to experience pleasure and excitement as they interact more with the game, and adds a sense of humor as the main part of the game [55]. To address motivational mechanisms the satisfaction theory can be applied [56]. Table 5 shows game design elements that address some psychological needs.

Table 5.

Psychological needs and matched game design elements [56].

When designing applications for young children, it is essential to observe their satisfaction with Arabic e-learning applications. These applications are preferred to be in Arial font with a 30-point size and a full or 2/3 screen line length to make the reading task easier and clearer. The whole page should be easy for them to understand. Correspondingly, most Arab children prefer to listen to a female adult tutoring voice within applications [57,58]. Regarding characters inside game applications, young children, regardless of their gender, prefer the bunny character. Similarly, in the story application children prefer animal characters [57]. Interestingly, children above three years old have the ability to understand and recognize audio instructions and pictorial information [59]. Table 6 shows some guidelines to be taken into account when designing children’s applications.

Table 6.

Guidelines for designing children’s applications.

3.3.2. Game Interfaces and Features

The game is a tablet game based on an interactive story about a young bear named Latif. The game focuses on improving the child’s social, cognitive, and emotional abilities. It comprises four stories, each presenting a challenge for the child to overcome and achieve a sense of winning. The stories also incorporate principles such as a relaxation exercise, emotion recognition, decision making, and social interaction. These techniques are based on principles that are similar to those used in [61] which are recommended to be used as cognitive behavioral therapy-informed intervention for children who have anxiety and stress problems to prevent stress in children. Each story is narrated by a female voice. The child’s successful completion of challenges results in Latif’s state changing from negative emotions to happiness. The game ends with a confirmation that kindergarten is a place to make new friends, learn new things, and play in the play yard for a long time.

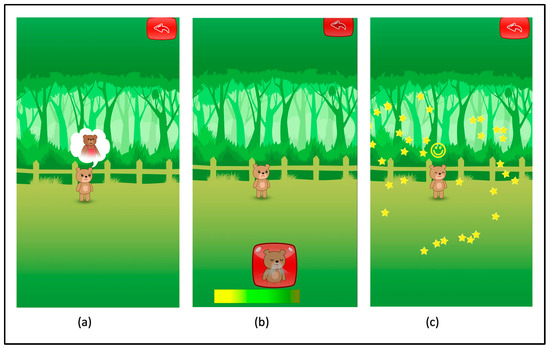

Story 1: Latif Fears

The first story of the game, “Latif fears”, is designed to help young children overcome their fear of separation from their parents. It presents Latif as it goes to kindergarten for the first time without his parent, a situation that many children can relate to. The visual progression of the ‘Latif fears’ story interface in the game, as shown in Figure 5, depicts the different stages of Latif’s emotional state as it goes to kindergarten for the first time without his parent. In Figure 5a, Latif is sad and misses his parent, highlighting the naturalness of the child’s emotions. To help Latif overcome his fear, the game presents a challenge to the child to do a relaxation exercise along with Latif. The child can press the breathing button and do the exercise with Latif to achieve a sense of winning (see Figure 5b). When completed successfully, Latif’s state changes from fear to happiness, fulfilling the principle of emotion recognition (see Figure 5c).

Figure 5.

Visual progression of the ‘Latif fears’ story interface in the game. (a) Latif, the main character, expresses sadness and longing for his parents, highlighting the child’s natural emotions. (b) The game presents a challenge where the child can join Latif in a relaxation exercise by pressing the breathing button, fostering a sense of achievement. (c) Successfully completing the exercise transforms Latif from fear to happiness, demonstrating the game’s ability to recognize and positively impact emotions.

This story achieves three principles, including the challenge principle, where the child is motivated to complete a challenge to achieve a sense of winning; the relaxation exercise principle, where the child is encouraged to do a relaxation exercise along with Latif; and the emotion recognition principle, where the child can see how Latif’s state changes from fear to happiness. These principles are designed to enhance the child’s social, cognitive, and emotional abilities in a fun and interactive way while making the child feel understood and supported.

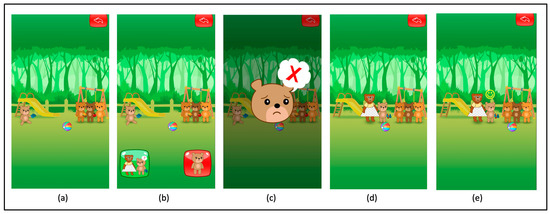

Story 2: Latif Meets New Friends

The second story of the game, “Latif meets new friends”, presents Latif facing troubles with other bears who steal his food, highlighting the fact that it is possible to face problems with others. However, the story emphasizes that we can overcome such problems. Figure 6 depicts the different stages of Latif’s emotional state as it meets new friends. As shown in Figure 6a, Latif is sad when his food is stolen. To help Latif overcome this situation, the game gives the child the chance to experience decision making by presenting two options. The first option is to leave Latif alone without doing anything while the second suggests that Latif asks for help from his teacher, as depicted in Figure 6b.

Figure 6.

Visual Progression of the ‘Latif meets new friends’ story interface in the game. (a) Latif is depicted as sad when his food is stolen, highlighting the challenge he faces with other bears. (b) The game offers the child two options to help Latif overcome the situation. One option is to leave Latif alone, while the second option suggests asking for help from his teacher. (c) If the child chooses the first option (not asking for help), a voice in the background emphasizes the importance of seeking help from adults in such situations. (d) If the child chooses the second option (asking for help), Latif’s teacher intervenes and speaks to the bears. (e) As a result of the teacher’s intervention, Latif’s emotional state changes from sad to happy, illustrating the principle of emotion recognition.

If the child selects the first option (do not ask for help), the female voice in the background confirms that seeking help from adults is necessary in such situations, as shown in Figure 6c.

On the other hand, if the child selects the second option (ask help from the teacher), Latif’s teacher comes and talks to the bears, telling them that stealing is wrong and asking them to apologize. The bears express their regret and return Latif’s food, as shown in Figure 6d. This element fulfills the principle of social interaction. As a result, Latif’s state changes from sad to happy, as shown in Figure 6e.

The “Latif meets new friends” story achieves three principles, including the decision making principle, where the child is given the opportunity to make a decision; the social interaction principle, where the importance of seeking help from adults is emphasized; and the emotion recognition principle, where the child can see how Latif’s state changes from sad to happy. These principles are designed to enhance the child’s social, cognitive, and emotional abilities in a fun and interactive way while teaching them important life skills.

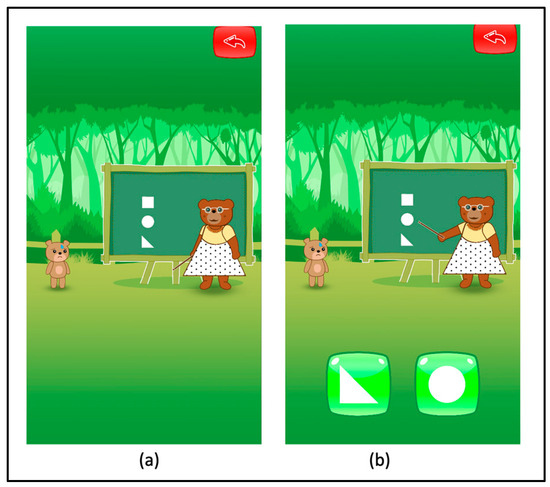

Story 3: Latif Meets His Teacher

The third story, “Latif meets his teacher”, presents Latif as a student who is learning something new for the first time and is feeling anxious. Latif is tense and unsure about his answer, as shown in Figure 7a.To help Latif, the game presents a challenge to the child to assist Latif in matching shapes correctly, as depicted in Figure 7b. When the child matches the shapes correctly, the female voice in the background encourages the child and informs them that they have passed. However, if the child matches the shapes incorrectly, the voice asks the child to try again. Upon completion of all the shapes, Latif’s state changes from anxiety to happiness, fulfilling the principle of emotion recognition.

Figure 7.

Visual progression of the ‘Latif meets his teacher’ story interface in the game. (a) Latif is depicted as tense and unsure when learning something new, highlighting his anxiety as a student. (b) The game presents a challenge to the child, where they are tasked with helping Latif match shapes correctly. When the child successfully matches the shapes, a supportive voice confirms their success. If the matches are incorrect, the voice encourages the child to try again.

The “Latif meets his teacher” story achieves two principles, including the challenge principle, where the child is motivated to complete a challenge to achieve a sense of winning, and the emotion recognition principle, where the child can see how Latif’s state changes from anxious to happy. These principles are designed to enhance the child’s social, cognitive, and emotional abilities in a fun and interactive way while teaching them problem-solving skills.

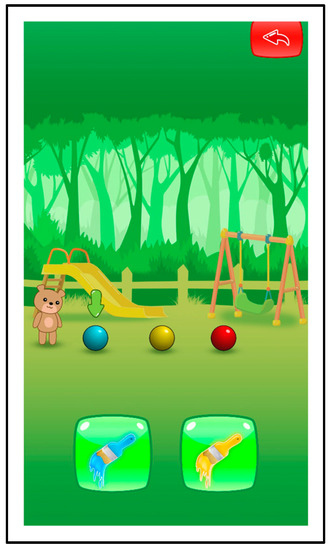

Story 4: Latif in the Play Yard

The fourth and final story of the game, “Latif in the play yard”, introduces the concept that kindergarten is a place to have fun and make new friends. This story showcases the play yard in the kindergarten where Latif plays every day. To make the story more engaging, the game asks the child to play the color matching game with Latif and help him win, as shown in Figure 8. This story is considered a challenge that the child must pass to achieve a sense of winning.

Figure 8.

Illustration of the color matching game in the “Latif in the play yard” story of the game where the child is challenged to help Latif win the game to achieve a sense of winning.

Upon successfully matching all the colors, Latif becomes happy as it wins, fulfilling the principle of emotion recognition.

The “Latif in the play yard” story achieves two principles, including the challenge principle, where the child is motivated to complete a challenge to achieve a sense of winning, and the emotion recognition principle, where the child can see how Latif’s state changes from neutral to happy.

Overall, the game interfaces are designed to engage young children in a fun and interactive way while enhancing their social, cognitive, and emotional abilities. The female voice narration and the use of Latif as the main character help create a relatable and enjoyable experience for the child. The game concludes with a positive message about the joys of kindergarten and the opportunities to learn and play with new friends.

3.4. Experimental Study

3.4.1. Purpose

The objective of the experiment was to compare the effects of three states: the Latif teddy bear huggable interface only, the game-based application only, and both the Latif teddy bear and the game. This comparison was aimed at verifying the validity of our idea and determining which state elicited the best reaction from the child.

3.4.2. Recruitment

The experiment was conducted in 2021 during the first week of the study at Meem hospitality center for children in the Riyadh region of Saudi Arabia on preschoolers. We recruited 24 children for this study and to control for any potential biases we randomized them into three focus groups with ages ranging from 3 to 5 years old. Each group consisted of eight children. The participants included both male and female students.

To ensure ethical considerations were met, we obtained informed consent from the parents or guardians of the participants before the study. The ethical approval was obtained from the Research Ethical Committee in the KSU (King Saud University). The approval reference numbers are KSU-HE-21-482 and KSU-HE-20-722.

In addition, we took necessary measures to ensure that the children felt comfortable and safe throughout the experiment. We explained the purpose and procedures of the study to the children in age-appropriate language and encouraged them to ask questions. We also informed them that their participation was voluntary and that they could withdraw from the study at any time.

3.4.3. Measures

To evaluate the effectiveness of the developed solutions in each of the three cases we used three measures: the child’s emotional appearance, their heartbeat rate as a measure of anxiety, and their overall condition before and after using the solutions.

We collected quantitative data for the first two measures, using numerical data obtained from measuring the child’s heartbeat rate using the wearable sensor and the Likert scale responses related to the child’s emotional state before and after the experiment. We used quantitative data analysis methods to analyze these measures and determine if there were any significant changes in the child’s emotional appearance and anxiety levels after using the developed solutions.

For the third measure, we collected qualitative data using the descriptive code method [62] to analyze the child’s condition before and after using the solutions. This involved organizing the data, specifying related words in each sentence, and summarizing them into one or two words which were coded. We used qualitative data analysis methods to analyze these measures and determine which state elicited the best reaction from the child.

By using these three measures and quantitative and qualitative data analysis methods, we were able to gather comprehensive data on the effectiveness of each state and make informed decisions on the potential of our solution.

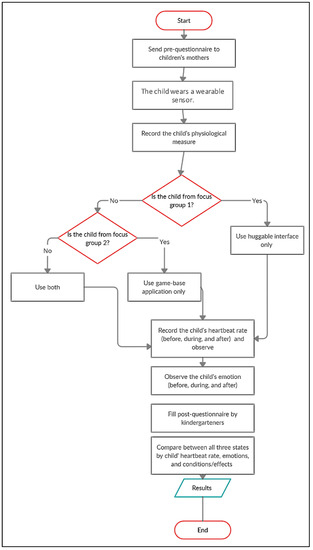

3.4.4. Experimental Procedure

The experimental procedure flow chart is shown in Figure 9 depicting the steps taken during experiment.

Figure 9.

Experimental procedure flow chart depicting the steps taken during experiment.

Prior to the experiment, we took necessary measures to ensure that all participants and their parents were well informed and gave their consent to participate. We documented the study purpose and device idea and sent them to the children’s parents along with an information sheet. After the parent had read and understood the purpose and procedures of the study, we asked them to sign a consent form to allow their children to participate.

In addition, we sent a pre-questionnaire to the parents to collect initial information about their children and to gauge their beliefs about the research problem. The pre-questionnaire contained general questions in short and simple sentences about their children’s adaptability to kindergarten. By analyzing the responses, we could determine whether the children were facing any difficulties during their first days in kindergarten.

During the experiment, each child wore a wearable sensor, namely an Apple watch, due to its FDA approval [63]. We recorded their measures to determine their anxiety levels while using the developed solutions. This same procedure had been used in a previous study by another researcher to measure children’s anxiety levels while playing a game that aimed to reduce media-induced anxiety [43].

Based on the experiment states, we divided the children into three focus groups. Children in focus group 1 used the Latif teddy bear only while children in focus group 2 used a game-based application. The children in focus group 3 used both the huggable interface and the game-based application. We identified the children’s states according to our observations of their emotional appearance, condition, and effects before and after the experiment. Table 7 provides a detailed description of the focus groups used in the experiment. Each child used each solution only once for a maximum of 10–15 min as children tend to lose attention when spending further time than this [43]. Finally, we recorded the child’s measures before and after the experiment.

Table 7.

Description of the focus groups used in the experiment including the ages of the children, the number of participants in each group, and the technology used.

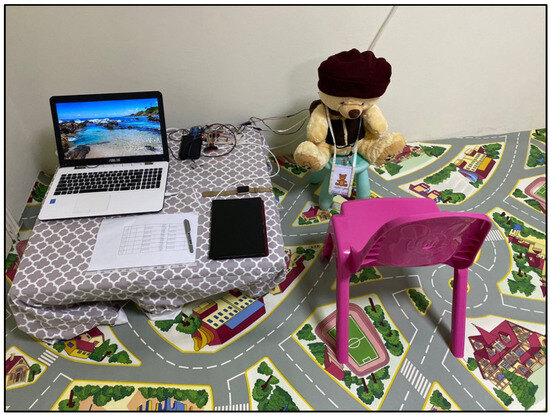

The experiment room (as shown in Figure 10) included the Latif huggable interface, the hardware connection needed to run it, an Apple watch that acts as a wearable sensor that the children wear during the experiment, a tablet to run the developed game for the children in focus group 2 and 3, a paper to record the observer’s notes about the children during the experiment, a laptop, and a chair placed in front of Latif where the child was to be seated.

Figure 10.

Experimental room setting, depicting the setup used during the experiment with preschoolers, including the huggable interface and game-based application.

In focus group 1, the children used the Latif huggable interface. The experiment started when the child listened to their parent’s voice through the speaker located at Latif’s head. The voice mentioned the child’s name along with some words that the child usually hears from their parent. Then, the parent used the microphone in the app to ask the child to hug Latif while, at the same time, they turned on the (احضن طفلي—hug my child) button through the switch button. Finally, the parent named a color (red, green, or blue) using the microphone in the app while they turned on the light with the specified color.

In focus group 2, the children used the game-based application. The experiment started when the child started playing using the tablet.

In focus group 3, the children used both solutions with the same steps that were used in focus groups 1 and 2.

In all focus groups, the children wore Apple watches to start recording their heartbeat rates. The observer recorded the child’s rates three times: before the experiment started, during it, and after it along with the child’s emotional appearance.

After the experiment, we conducted a post-questionnaire to evaluate the effectiveness of all the states. We asked kindergarten teachers to fill out the questionnaire which was based on some principles of the separation anxiety assessment scale–child and parent versions (SAAS–C/P). The SAAS–C/P is a tool used to assess separation anxiety symptoms in children, such as the fear of being alone and fear of abandonment [64].

The post-questionnaire was designed to gather information about the children’s behavior and emotional responses during the experiment. The questionnaire was administered to the kindergarten teachers because they had observed the children’s behavior over a more extended period and could provide more detailed feedback than the parents.

4. Analysis and Results

During the experiment, various data regarding the participants were recorded and documented including their age, number, emotional appearance, condition before and after the experiment, heartbeat rate, and the effects of technology on them.

4.1. Pre-Questionnaire Analysis

The pre-questionnaire was filled out by the parents and the responses were analyzed using Google Forms. The responses to questions about the children’s reactions to staying with relatives without their parents and their adaptation to kindergarten were varied. In particular, a large percentage of parents expressed anxiety about their children’s adaptation to kindergarten, with 50% responding “strongly yes” to this question.

The most important question in the pre-questionnaire was related to the parents’ perspective on leaving their children in a situation without proper preparation which could cause problems for the children and make them refuse to go to kindergarten. A significant majority of parents, 69.2%, responded “strongly yes” to this question, highlighting the importance of preparing children for such situations.

These pre-questionnaire results confirm the research problem and suggest that the situation in which a child leaves their parent for the first time should be taken into consideration due to the consequent problems for both the children and their parents.

4.2. Measure 1: Child Emotional Appearance

The child’s emotional appearance was documented by the researchers before and after the experiment for all focus groups. The emotions were classified as happy, normal, or sad and were denoted by the numbers 3, 2, and 1, respectively. It is important to note that these emotions were subjective and were based on the researcher’s observation and interpretation of the child’s behavior and facial expressions.

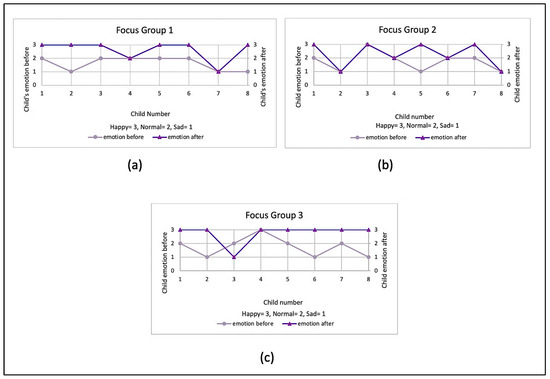

The child’s emotions before and after the experiment for all focus groups were recorded and visualized in a scatter diagram, as shown in Figure 11.

Figure 11.

Scatter diagram showing Measure 1: the child’s emotional appearance in focus groups 1, 2, and 3 before and after the experiment. (a) In focus group 1, six children improved emotionally with the Latif huggable interface, while child number 4 and child number 7 showed no change. (b) In focus group 2, three children (numbers 1, 5, and 7) improved emotionally with the developed game, while others showed no change. Child number 3 was already happy before the experiment. (c) In focus group 3, six children (numbers 1, 2, 5, 6, 7, and 8) improved emotionally with both the Latif huggable interface and the developed game. Child number 4 stayed happy, and child number 3 changed from normal to sad.

In focus group 1, the participants used the Latif huggable interface during the experiment. The scatter diagram (Figure 11a) showed that there was a positive effect on six children as their emotional state improved after using the huggable interface. However, there was no change in the emotional state of child number 4, who was classified as normal, and child number 7, who was classified as sad.

In focus group 2, the participants used the developed game during the experiment. The scatter diagram (Figure 11b) showed that there was a positive effect on three children with the numbers 1, 5, and 7 as their emotional state improved after using the game. However, there was no change in the emotional state of children with the numbers 2, 4, 6, and 8. Children with the numbers 2 and 8 were sad without any changes while children with the numbers 4 and 6 were normal without changes. The child with number 3 was already happy before the experiment.

In focus group 3, the participants used both the Latif huggable interface and the developed game during the experiment. The scatter diagram (Figure 11c) showed that there was a positive effect on six children with the numbers 1, 2, 5, 6, 7, and 8 as their emotional state improved after using the Latif huggable interface and the developed game. However, there was no change in the emotional state of the child with number 4 as they were already happy before the experiment. Additionally, the child with number 3 was normal before the experiment but became sad after the experiment.

4.3. Measure 2: Child Heartbeat Rate

As previously mentioned, the heartbeat rate was used to measure the children’s anxiety level during the experiment. The heartbeat rate was recorded before, during, and after the experiment for each child in all focus groups. It is important to note that the heartbeat rate is a physiological measure of anxiety and may not always correlate with the child’s emotional appearance.

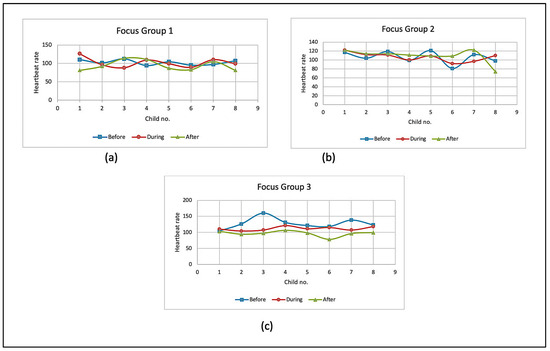

The child’s heartbeat rates before, during, and after the experiment for all focus groups were recorded and visualized in a scatter diagram, as shown in Figure 12.

Figure 12.

Scatter diagram showing Measure 2: the child heartbeat rate in focus groups 1, 2, and 3 before, during, and after the experiment. (a) In focus group 1, some children showed a gradual decrease in heartbeat rates (2, 5, 6, 8), while others showed no noticeable change (1, 3, 4, 7). (b) In focus group 2, some children had a decreased heartbeat rate (5, 8), while others showed an increase (4, 6, 7). No clear change was observed for children (1, 2, 3). (c) In focus group 3, most children experienced a gradual decrease in heartbeat rates, except for one child (1) where no clear change was observed.

In focus group 1, the participants used the Latif huggable interface during the experiment. The scatter diagram (Figure 12a) showed that the heartbeat rates of children with numbers 2, 5, 6, and 8 gradually decreased during the experiment. The heartbeat of child number 1 decreased at the end of the experiment but not gradually. However, there was no noticeable change in the heartbeat rates of children with numbers 3, 4, and 7.

In focus group 2, the participants used the developed game during the experiment. The scatter diagram (Figure 12b) showed that the heartbeat rate decreased in children with numbers 5 and 8 only. The heartbeats of children with numbers 4, 6, and 7 increased at the end of the experiment. However, there was no clear noticeable change in the heartbeat rates of children with numbers 1, 2, and 3.

In focus group 3, the participants used both the Latif huggable interface and the developed game during the experiment. The scatter diagram (Figure 12c) showed that the heartbeat rates gradually decreased for all children except for child number 1 where no clear change was noticed in the heartbeat rate.

4.4. Measure 3: Child Condition before the Experiment and the Effects on the Child after the Experiment:

The descriptive code method was used to analyze the child’s condition before the experiment and the solution’s effect on the child after the experiment as these were qualitative data. However, for the first measure, which is the child’s emotion before and after the experiment, and the second measure, which is the child’s heartbeat rate, no further analysis was needed as these were quantitative data.

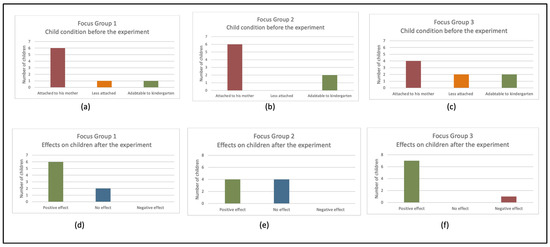

Based on our observations of the children’s conditions before the experiment and the keywords specified during the analysis, we denoted three main states for the child: attached to their parent, less attached, and adapted to the kindergarten. Additionally, based on the keywords specified during the analysis of the effects on children after the experiment, we denoted three types of effects: positive, no effect, and negative. It is important to note that these codes were mixed for 24 children and not related to only one child. The children in all focus groups were classified according to these two dimensions: condition and effect.

Figure 13 provides a visual representation of the number of children in each condition before the experiment (Figure 13a–c) and the number of children in each type of effect after the experiment (Figure 13d–f) for all focus groups. The conditions before the experiment were classified based on the child’s attachment to their parent, their level of attachment, and their adaptation to the kindergarten. The effects after the experiment were classified as positive, no effect, or negative based on the keywords specified during the analysis of the notes recorded about the children during the experiment.

Figure 13.

Bar chart showing the number of children in each condition before the experiment for all focus groups (a–c) and the number of children in each type of effect after the experiment (d–f).

These measures provided valuable qualitative data that complemented the quantitative measures of the child’s emotion and heartbeat rate. The combination of quantitative and qualitative data allowed for a more comprehensive understanding of the children’s emotional state and their response to the suggested solutions.

5. Discussion

5.1. Principal Findings

The results presented above indicate the significant effects of the solutions on the children in each group. Our research focused on making a comparison between three types of solutions. Therefore, we compared the three focus groups based on the results obtained, which included children’s emotional appearance before and after the experiment, children’s heartbeat rate before and after the experiment, and children’s condition before the experiment along with the effects on the child after the experiment to see which state had the most effects on children’s adaptation.

The results showed that focus group 1, who used the Latif huggable interface, and focus group 3, who used both the Latif huggable interface and the developed game, had the best emotional change across all groups. There was a positive effect of emotion in focus group 1 on six children and in focus group 3 on six children. The least positive effect was in focus group 2 who used the developed game only, where the positive change was observed in three children only. One child was already happy before the experiment.

Furthermore, there was a significant gradual decrease in children’s heartbeat rates in focus group 3 which was observed in all the participating children except for one child. The decrease in focus group 1 was observed in five children while the least decrease was in focus group 2 where it was observed in two children only. However, the heartbeat rate increased in the other three children in focus group 2.

Moreover, although four children in focus group 3 were considered attached to their parents and two were considered less attached with some anxiety, the positive effect after the experiment was observed in seven children except for one child who had a negative effect. This may be because the child was the youngest participant (three years and one month) and faced more difficulties than the other participants. In focus group 1, six children were considered attached to their parents and one child was less attached and experienced some anxiety. The positive effect was observed in six children. The least positive effect was observed in focus group 2 where it was observed in four children only.

Based on these observations, we can deduce that our solutions have a positive impact on children’s adaptation. The best results were achieved when we used the Latif huggable interface with the game followed by using the Latif huggable interface only and then using the game only. This boost in results in focus group 3 can be explained through the combination of the Latif huggable interface, which already had a positive impact, with the game, which needed support from another solution.

The results of our study are consistent with previous research that has shown the potential of using huggable interfaces and game-based applications in improving children’s emotional and social development. For example, the study in [36] found that haptic technologies can be effective at easing anxiety and should be explored further to capture the nuances of different modalities in relation to specific situations and trait characteristics. Similarly, some studies have shown the positive impact of certain technologies on children’s adaptation and anxiety levels. For instance, a study by [65] found that playing back the recorded maternal voice had a positive impact on comforting children undergoing bilateral ophthalmic surgery. The children who listened to their parent’s voice showed a significantly low incidence of emergence agitation compared to those who wore headphones without auditory stimuli. Another study by [66] examined the effects of playing prosocial touch-screen applications on preschool children’s subsequent prosocial behavior. The study suggests that touch-screen applications may contribute to fostering prosocial behavior in early childhood.

However, our study extends previous research by investigating the effectiveness of combining huggable interfaces and game-based applications in a kindergarten setting. The results suggest that this combination can lead to better outcomes in terms of children’s emotional state and adaptation to the kindergarten environment.

5.2. Limitations and Future Directions

Despite these promising findings, our study has several limitations. Firstly, the sample size was relatively small which limits the generalizability of the results. Second, the study was conducted in a specific setting and with a specific population which may limit the applicability of the findings to other contexts. A third limitation of our study was the use of the heartbeat rate to measure anxiety levels. Although there were consistent results in most cases, we noticed some conflicts in the experiment results. It is possible that there was another influencing factor on a child’s heartbeat rate, regardless of their anxiety. Additionally, it is important to note that the heartbeat rate is a physiological measure of anxiety and may not always correlate with the child’s emotional appearance. Furthermore, emotional recordings are subjective and are based on the researcher’s observation and interpretation of the child’s behavior and facial expressions, which may introduce potential bias into the study. Finally, our study only measured short-term effects and additional research is needed to investigate the long-term effects of these solutions.

However, our study provides valuable insights into the potential benefits of using huggable interfaces and game-based applications in improving children’s emotional state and adaptation to the kindergarten environment. Future research can address the limitations of our study and investigate the long-term effects of these solutions in different contexts and with larger and more diverse samples. It would also be interesting to explore the potential moderating effects of other factors, such as age, gender, and cultural background, on the effectiveness of these solutions.

In our future work, we plan to add more features to our developed solutions based on the feedback we received from the study. For example, we aim to add emotional indication features to the Latif huggable interface app that would enable the parent to check whether their child is happy at a given time. Moreover, we aim to add more stories about Latif and allow the child to give their feedback about each story in the developed game.

The practical implications of our study suggest that these solutions can provide an innovative and engaging way to support children’s emotional and social development as well as their adaptation to new environments. Furthermore, the potential benefits of these solutions extend beyond the kindergarten setting and can be applied to other settings, such as hospitals, where children can benefit from emotional and social support.

6. Conclusions

In this study, we investigated the effectiveness of using huggable interfaces and game-based applications to improve children’s emotional state and adaptation to the kindergarten environment. The results showed that using these solutions led to a greater decrease in anxiety levels and a greater increase in attachment to parents among children who used them compared to those who did not. In addition, the children who used the solution showed better adaptation to the kindergarten environment compared to those who did not use the solution.

Our study adds to the growing body of research demonstrating that huggable interfaces and game-based applications can provide innovative and engaging ways to support children’s emotional and social development. By combining these solutions, we were able to offer a more comprehensive approach addressing different dimensions of the child’s emotional state.

In conclusion, our study suggests that the combination of huggable interfaces and game-based applications can lead to better outcomes in terms of children’s emotional state and adaptation to the kindergarten environment. Although the study has limitations, the findings suggest the potential benefits of using these solutions in early childhood education. Our study also highlights the importance of considering child-centered design principles when developing solutions for young children.

We hope that our work will inspire the further development of innovative solutions to support children’s wellbeing and their adaptation to the kindergarten environment. By providing effective solutions to help children adapt to kindergarten and overcome separation anxiety, we can contribute to building a healthier and happier society.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.A. (Reham Alabduljabbar); Data curation, R.A. (Raseel Alsakran); Formal analysis, R.A. (Raseel Alsakran); Funding acquisition, R.A. (Reham Alabduljabbar); Investigation, R.A. (Reham Alabduljabbar) and R.A. (Raseel Alsakran); Methodology, R.A. (Reham Alabduljabbar) and R.A. (Raseel Alsakran); Project administration, R.A. (Reham Alabduljabbar); Resources, R.A. (Reham Alabduljabbar) and R.A. (Raseel Alsakran); Software, R.A. (Raseel Alsakran); Supervision, R.A. (Reham Alabduljabbar); Validation, R.A. (Reham Alabduljabbar) and R.A. (Raseel Alsakran); Visualization, R.A. (Reham Alabduljabbar) and R.A. (Raseel Alsakran); Writing—original draft, R.A. (Reham Alabduljabbar) and R.A. (Raseel Alsakran); Writing—review and editing, R.A. (Reham Alabduljabbar). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors extend their appreciation to the Deputyship for Research and Innovation, Ministry of Education in Saudi Arabia, for funding this research work through project no. (IFKSUOR3–041–3).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical approval was obtained from the Research Ethical Committee in KSU (King Saud University). The approval reference numbers are KSU-HE-21-482 on 29/09/2021 and KSU-HE-20-722 on 22/12/2020.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interest or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Cartwright-Hatton, S.; McNicol, K.; Doubleday, E. Anxiety in a neglected population: Prevalence of anxiety disorders in pre-adolescent children. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2006, 26, 817–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramachandran, V. Encyclopedia of Human Behavior; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Robbins, J. Separation Anxiety: A Study on Commencement at Preschool. Australas. J. Early Child. 1997, 22, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chase, R.; Pincus, D. Sleep-Related Problems in Children and Adolescents With Anxiety Disorders. Behav. Sleep Med. 2011, 9, 224–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erermiş, S.; Bellibaş, E.; Ozbaran, B.; Büküşoğlu, N.D.; Altintoprak, E.; Bildik, T.; Cetin, S.K. Temperamental Characteristics of Mothers of Preschool Children With Separation Anxiety Disorder. Turk. J. Psychiatry 2009, 20, 14–21. [Google Scholar]

- Bodden, D.H.; Dirksen, C.D.; Bögels, S.M. Societal Burden of Clinically Anxious Youth Referred for Treatment: A Cost-of-illness Study. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2008, 36, 487–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edwards, S.L.; Rapee, R.M.; Kennedy, S. Prediction of anxiety symptoms in preschool-aged children: Examination of maternal and paternal perspectives. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2010, 51, 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pelaez, M.; Novak, G. Returning to School: Separation Problems and Anxiety in the Age of Pandemics. Behav. Anal. Pract. 2020, 13, 521–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, J.L.; Dodd, H.F.; Bovopoulos, N. Temperament, Family Environment and Anxiety in Preschool Children. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2011, 39, 939–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.; Lim, T.; Ragen, E.; Tan, M.; Ishworiya, R. Managing Children’s Anxiety During COVID-19 Pandemic: Strategies for Providers and Caregivers. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 552823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallace, A.; Spence, C. The science of interpersonal touch: An overview. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2010, 34, 246–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascio, J.; Moore, D.; McGlone, F. Social touch and human development. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 2019, 35, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saarinen, A.; Harjunen, V.; Jasinskaja-Lahti, I.; Jaaskelainen, I.; Ravaja, N. Social touch experience in different contexts: A review. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2021, 131, 360–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herren, C.; In-Albon, T.; Schneider, S. Beliefs regarding child anxiety and parenting competence in parents of children with separation anxiety disorder. J. Behav. Ther. Exp. Psychiatry 2013, 44, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dozva, M. Strategies used by Chitungwiza day care centre caregivers to deal with separation anxiety in preschool children. Zimb. J. Educ. Res. 2009, 21, 358–374. [Google Scholar]

- Land, B.; Norton, T. Coping with separation anxiety. Day Care Early Educ. 1985, 12, 18–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shouldice, A.; Stevenson-Hinde, J. Coping with security distress: The Separation Anxiety Test and attachment classification at 4.5 years. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry Allied Discip. 1992, 33, 331–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SHoaakazemi, M.; Javid, M.; Tazekand, F.; Rad, Z.; Gholami, N. The Effect of Group Play Therapy on Reduction of Separation Anxiety Disorder in Primitive School Children. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 69, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pincus, B.; Eyberg, S.M.; Choate, M.L. Adapting parent-child interaction therapy for young children with separation anxiety disorder. Educ. Treat. Child. 2005, 28, 163–181. [Google Scholar]

- Pincus, D.B.; Santucci, L.C.; Ehrenreich, J.T.; Eyberg, S.M. The Implementation of modified parent-child interaction therapy for youth with Separation Anxiety Disorder. Cogn. Behav. Pract. 2008, 15, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, N.; Tonge, B.; Heyne, D.; Pritchard, M.; Rollings, S.; Young, D.; Myerson, N.; Ollendick, T. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of school-refusing children: A controlled evaluation. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 1998, 37, 395–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, P.; Duffy, A.; Dadds, M.; Rapee, R. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of anxiety disorders in children: Long-term (6-year) follow-up. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2001, 69, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haans, A.; IJsselsteijn, W. Mediated social touch: A review of current research and future directions. Virtual Real. 2006, 9, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haans, A.; IJsselsteijn, W. I’m always touched by your presence, dear: Combining mediated social touch with morphologically correct visual feedback. In Proceedings of the 12th Annual International Workshop on Presence, Los Angeles, CA, USA, 11–13 November 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Tsetserukou, D. HaptiHug: A Novel Haptic Display for Communication of Hug over a Distance. In Haptics: Generating and Perceiving Tangible Sensations; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Kappers, A.M.L., van Erp, J.B.F., Bergmann Tiest, W.M., van der Helm, F.C.T., Eds.; EuroHaptics: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; Volume 6191. [Google Scholar]

- Teh, J.K.; Cheok, A.D.; Choi, Y.; Fernando, C.L.; Peiris, R.L.; Fernando, O.N. Huggy pajama: A parent and child hugging communication system. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Interaction Design and Children, Como, Italy, 3–5 June 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Nunez, E.; Hirokawa, M.; Perusquia-Hernandez, M.; Suzuki, K. Effect on Social Connectedness and Stress Levels by Using a Huggable Interface in Remote Communication. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Affective Computing and Intelligent Interaction (ACII), Cambridge, UK, 3–6 September 2019; IEEE: New York, NY, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Kuwamura, K.; Sakai, K.; Minato, T.; Nishio, S.; Ishiguro, H. Hugvie: A medium that fosters love. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE RO-MAN, Gyeongju, Republic of Korea, 26–29 August 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Nakanishi, J.; Sumioka, H.; Ishiguro, H. A huggable communication medium can provide sustained listening support for special needs students in a classroom. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 93, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, H.; Ban, M.; Osawa, H.; Nakanishi, J.; Sumioka, H.; Ishiguro, H. Huggable Communication Medium Maintains Level of Trust during Conversation Game. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakanishi, J.; Sumioka, H.; Ishiguro, H. Mediated hugs modulate impressions of Hearsay information. Adv. Robot. 2020, 34, 781–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunez, E.; Hirokawa, M.; Suzuki, K. Design of a Huggable Social Robot with Affective Expressions Using Projected Images. Appl. Sci. 2018, 8, 2298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, S.; Breazeal, C.; Logan, D.; Weinstock, P. Huggable: The Impact of Embodiment on Promoting Socio-emotional Interactions for Young Pediatric Inpatients. In Proceedings of the 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI 18), New York, NY, USA, 21–26 April 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bruikman, H.; van Drunen, A.; Huang, H.; Vakili, V. Lali: Exploring a tangible interface for augmented play for preschoolers. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Interaction Design and Children (IDC 09), Como, Italy, 3–5 June 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Paternò, F.; Ruyter, B.; Markopoulos, P.; Santoro, C.; van Loenen, L.K. Ambient Intelligence. In Proceedings of the Third International Joint Conference, Pisa, Italy, 13–15 November 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Haynes, A.C.; Lywood, A.; Crowe, E.M.; Fielding, J.L.; Rossiter, J.M.; Kent, C. A calming hug: Design and validation of a tactile aid to ease anxiety. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0259838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapp, K.M. The Gamification of Learning and Instruction: Game-Based Methods and Strategies for Training and Education; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao, H.; Chen, J. Using a gesture interactive game-based learning approach to improve preschool children’s learning performance and motor skills. Comput. Educ. 2016, 95, 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ongoro, C.; Mwangoka, J. Using Game-Based approach to enhance language learning for preschoolers in Tanzania. In Proceedings of the 2nd Pan African International Conference on Science, Computing and Telecommunications (PACT 2014), Arusha, Tanzania, 6–10 August 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Geurts, L.; Vanden, V.; Celis, V.; Husson, J.; Audenaeren, L.; Loyez, L.; Goeleyen, A.; Wouter, J.; Ghesquiere, P. DIESEL-X: A Game-Based Tool for Early Risk Detection of Dyslexia in Preschoolers. In Describing and Studying Domain-Specific Serious Games. Advances in Game-Based Learning; Torbeyns, J., Lehtinen, E., Elen, J., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 93–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alabduljabbar, R.; Almutawa, M.; Alkathiri, R.; Alqahtani, A.; Alshamlan, H. An Interactive Augmented and Virtual Reality System for Managing Dental Anxiety among Young Patients: A Pilot Study. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 5603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudarmilah, E.; Ferdiana, R.; Nugroho, L.E.; Susanto, A.; Ramdhani, N. Tech review: Game platform for upgrading counting ability on preschool children. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Information Technology and Electrical Engineering (ICITEE), Yogyakarta, Indonesia, 7–8 October 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Heumos, T.; Kickmeier-Rust, D. Using game-based training to reduce media induced anxiety in young children. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Games Based Learning, Odense, Denmark, 3–4 October 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Mavridis, A.; Tsiatsos, T. Game-based assessment: Investigating the impact on test anxiety and exam performance. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 2017, 33, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Lin, D.; Chen, S. Effects of anxiety levels on learning performance and gaming performance in digital game-based learning. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 2018, 34, 324–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Android. Meet Android Studio. Android Developers. 2023. Available online: https://developer.android.com/studio/intro (accessed on 28 May 2023).

- Android. Build Your First Android App in Java. Android Developers. 2023. Available online: https://developer.android.com/codelabs/build-your-first-android-app?hl=ar (accessed on 28 May 2023).