Abstract

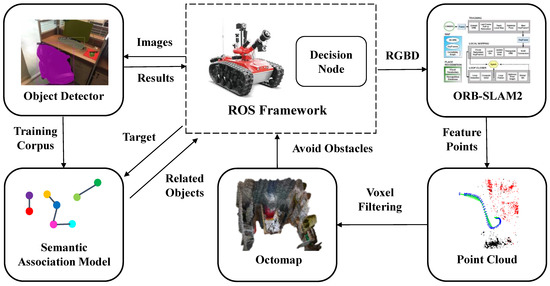

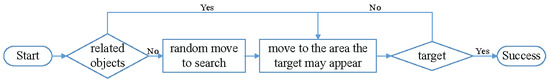

In recent years, the rapid development of computer vision makes it possible for mobile robots to be more intelligent. Among the related technologies, the visual SLAM system allows the mobile robot to locate itself, build the map, and provide a navigation strategy to execute follow-up tasks, such as searching for objects in unknown environment according to the observed information. However, most of the existing studies are meant to provide a predefined trajectory for the robot or allow the robot to explore blindly and randomly, which undoubtedly affects the efficiency of the object navigation process and goes against with the idea of “intelligent”. To solve the above problems, an efficient object navigation strategy is proposed in this paper. Firstly, a semantic association model is obtained by using the Mask R-CNN and skip-gram to conduct correlation analysis of common indoor objects. Then, with the help of the above model and ROS framework, an effective object navigation strategy is designed to enable the robot to find the given target efficiently. Finally, the classical ORB-SLAM2 system method is integrated to help the robot build a high usability environment map and find passable paths when moving. Simulation results validated that the proposed strategy can efficiently help the robot to navigate to the object without human intervention.

1. Introduction

With the rapid development of artificial intelligence, sensors, and other hardware and software technologies, the research of intelligent robots has gradually become a hot spot both in the industrial and academic fields in recent years. More and more robot products appear in our field of vision, which bring great convenience to the life of contemporary people. In order to achieve intelligent functions, robots often need to use their on-board sensors to explore their surroundings, locate their position, carry out path planning schemes, and build the environment map, so as to arrive to the destination and accomplish the specified tasks [1]. The simultaneous localization and mapping technology, SLAM, is one of the most famous technologies, which can help intelligent robots to complete the above steps in an unfamiliar environment without prior knowledge, and is considered to be a great progress in robotics, with both great theoretical significance and application value. In recent years, with the continuous development of computer vision technology, the visual SLAM system has gradually become a notable research focus, because of its advantages of strong perception ability. At present, visual SLAM is becoming more and more mature in pose estimation and map building, and has achieved good results in accuracy and real-time performance. Using the environment map built by the visual SLAM system, the robot can navigate to the target with the help of a path planning algorithm. However, the environment is in dynamic change, so the map-based navigation method may fail, and the robot would need to explore blindly and randomly, which undoubtedly affects the rapidity and efficiency, and increases the energy consumption of the robot to a certain extent.

In daily life, people often arrange objects according to their purpose use. For example, the mouse will be placed next to the computer and the bowls will be placed in the cupboard. People will look for objects using the semantic relationships between them in the corresponding area. This paper will explore how to teach robots to learn these kinds of relationships and how to make the robot sense, understand, and explore its surroundings autonomously. In order to achieve the aforementioned goals, the following challenges need to be tackled.

(1) Traditional research on robot autonomous navigation strategies cannot work in dynamic environments, and end-to-end methods have poor generalization. Therefore, the ways in which to make the robot navigate itself in a timely and efficiently manner, based on the environmental information it perceives, remains to be studied.

(2) To realize efficient object navigation, robots must have a higher understanding of the environment to decide where to go next. Human beings can obtain the correlation between objects through continuous learning and practice in daily life; however, the consideration of how to quantify such relations and teach robots to use them needs to be investigated.

(3) In order to accomplish the exploration task in the environment, robots need to make corresponding actions based on the understanding of the environment, which depends on the combination of location, obstacle avoidance, environment mapping, and target detection. Therefore, a detailed and fully functional navigation strategy should be designed.

The main contributions of this paper can be summarized as follows:

(1) A novel and efficient object navigation strategy based on high-level semantic information is proposed in this paper, which can make use of environmental semantic information to provide decision guidance for the robot, so as to give it the ability to recognize the environment and efficiently find the given target.

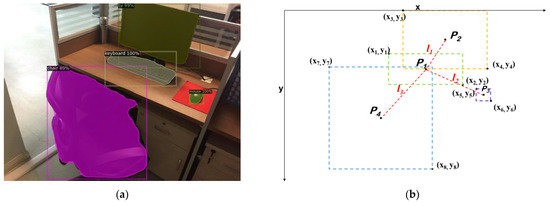

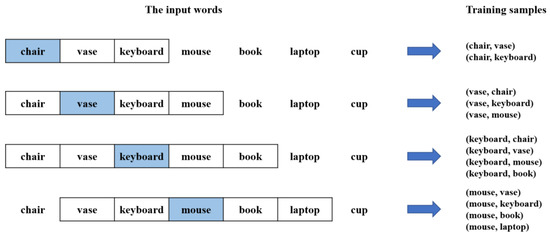

(2) To help the robot obtain semantic relationships, it is necessary to quantify the correlation between different objects. First, this paper uses the object detection framework Mask R-CNN [2] to calculate the Euclidean distance between common objects detected in the images and to gather extensive object–distance relationships for objects. Then, the word-to-vector framework, skip-gram, is used to learn these distance relationships and obtain the universal semantic similarity ranking; that is, the final semantic association model.

(3) Several functions, such as object detection, self-localization, obstacle avoidance, and map building, based on ROS and the classical ORB-SLAM2 [3] method, are integrated to the object navigation strategy. The robot will perceive the surrounding environment through the RGB-D camera and the control system of the robot will decide the next destination according to the current observation, the robot’s position, the environment map, and the semantic association model.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, a brief survey of related literature is given. Section 3 introduces the research on the semantic relevance of common objects and provides an autonomous object navigation strategy of the mobile robot based on ROS. The experimental results are shown in Section 4. In Section 5, this paper makes a summary and presents future works.

2. Related Works

2.1. Robot Visual SLAM Systems

Based on the environment map built by the SLAM systems, the intelligent robot can use the global path planning algorithm to navigate itself to the target position. Visual SLAM refers to the complex process of the robot calculating its position and direction by only using the visual input of the camera. The robot needs to extract features of the surrounding environment and determine its position by matching features from different perspectives. The first pioneering work on visual SLAM is the research on spatial uncertainty estimation by Sims and others at the International Conference on Robotics and Automation in 1986 [4]. With the rapid development of related technology, a variety of visual SLAM technologies have emerged and achieved good results, such as the first real-time monocular visual SLAM system MonoSLAM [5], the earliest SLAM algorithm that takes tracking and mapping as two threads, respectively, of PATM (parallel tracking and mapping) [6], and the first real-time 3D reconstruction system based on depth camera KinectFusion [7]. In recent years, ORB-SLAM series [3,8,9], typical visual SLAM systems based on feature points, represent a peak of the development of visual SLAM technology, which can achieve good results in real-time, stability, and robustness.

Most of the current visual SLAM systems rely only on low-level geometric features and cannot provide the semantic information of objects in the surroundings, such as a desk, a computer, and so on. On this condition, the robot cannot understand the environment, which undoubtedly limits the ability of robots to complete complex tasks. Therefore, researchers began to try to integrate advanced semantic features into the environment map, and the concept of “semantic SLAM” came into being [10]. With the combination of image detection and deep learning technology, the semantic SLAM system can recognize objects in the environment and obtain their semantic information, such as functional attributes and scene properties, so that it can help robots to complete more intelligent service tasks. Most of the semantic SLAM-related research focuses on the accuracy and the richness of the built map; only a few studies have focused on using semantic information to help robots have a better understanding of the environment and finish more intelligent tasks.

2.2. Robot Navigation Strategy

In the long-term running state, the environment is in a state of dynamic change, so the map-based navigation method may fail. At the same time, due to the position change of the target object, a traditional global planning algorithm is also no longer applicable. Therefore, the consideration of how to make the robot understand the surrounding environment and realize efficient dynamic autonomous path planning has become a hot research field.

With the continuous development of deep reinforcement learning, many scholars have designed network models for navigation tasks in recent years. Zhu et al. [11] use pictures as targets to enable robots to obtain scene information through observation and navigate to the location of the target object autonomously, which is a pioneering work in the field of object driven navigation. Narasimhan et al. [12] let the robot learn to predict the room layout in unobserved areas and try to use architectural rules to complete room navigation tasks. Wu et al. [13] construct the room probability relationship diagram through the prior information obtained during training, take the specific room type as the navigation target, and carry out path planning according to the learned relationship model between rooms. Mousavian et al. [14] use semantic segmentation and target detection algorithms as the input of observation, and use the deep neural network to learn end-to-end navigation methods. The above neural network models have made some achievements in the field of object driven navigation, but end-to-end learning methods need to use a large number of labeled images and videos for training, and are ineffective in environment exploration and long-term path planning. On the whole, the research on robot autonomous navigation strategy is still in an exploratory stage, and the performance of introducing semantic information into the robot object navigation needs to be further improved.

4. Experiments and Discussions

4.1. Verification of the Semantic Association Model

The Mask R-CNN model used in this paper is trained using the MS COCO dataset, which can detect 81 kinds of objects. This paper mainly uses 24 indoor objects to simply show the feasibility of the proposed strategy. In this section, this paper will take two places as examples to introduce the extraction and verification of the above semantic association model, both from the qualitative and quantitative aspects, so as to verify the validity and reliability of the proposed model. Notably, although this paper shows two semantic association models separately, the robot will combine all the models together in practice to produce the final moving decision according to the current observations and the target object.

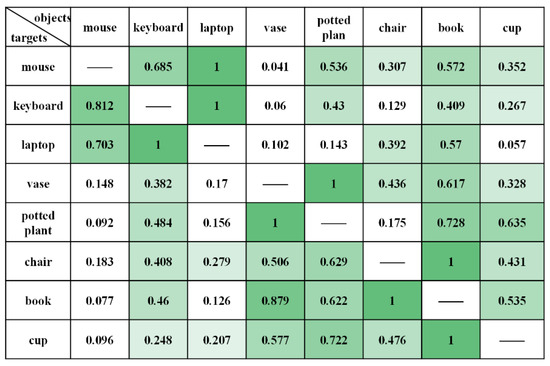

4.1.1. Office Places

To produce a reasonable semantic association model, particularly for the office places, this paper selectively collected 500 pictures (400 of them are from the SUN Database [24] or the internet and the other 100 pictures are collected using the camera), which consist of several typical objects in the office. When processing these pictures, this paper manually corrected some error identification problems caused by the Mask R-CNN model, such as the problem that some laptops are incorrectly identified as “tv” or “oven”, and only retained objects that were detected more than 300 times in all pictures, to filter out the objects that are not often placed in office places, so as to increase the accuracy of the model. Then, the detection results are processed according to the steps described in Section 3.2 to obtain the final semantic association model, which eventually consists of eight objects, as shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

The semantic association model for the office places.

The higher the score of the two objects in the figure, the more related the two objects are. It can be easily found that the semantic association model this paper proposed is in line with people’s cognition in daily life. Taking the “keyboard” as an example, its related objects are “laptop”, “mouse”, “potted plant”, “book”, “cup”, “chair”, and “vase”, sorted by semantic relevance. That is, the probability of “a laptop is near a keyboard” is greater than the probability of “a vase is near a keyboard”, which is highly conformed to our daily observation. It is worth noting that the matrices in Figure 4 and Figure 6 are not symmetrical, which is because the scores are also highly impacted by other objects. Taking Figure 3 as an example, the most related object of the “mouse” is the “keyboard”; however, the most related object of the “keyboard” is the “tv”. Numerous training samples like this will ultimately generate the semantic association model.

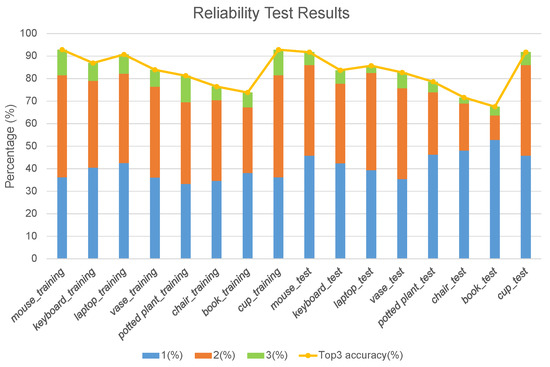

This paper evaluated the reliability of the above model using real scene images, as shown in Figure 7. “0(%)” represents the percentage of likelihood that the first three objects closest to the target in the real image are not in the corresponding top three objects in the semantic association model. “Top 3 accuracy (%)” shows the percentage of likelihood that there are the same objects in the top three objects, which may be one, two, or three. It can be seen that most of the “Top 3 accuracy (%)” is more than 80%, indicating that the semantic association model obtained in this paper is feasible in an actual scenario.

Figure 7.

Reliability test results of the semantic association model for the office places.

4.1.2. Kitchen Places

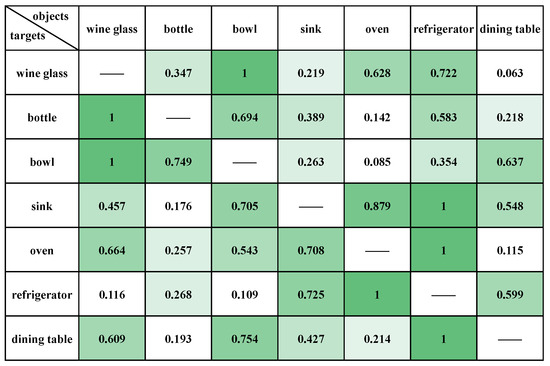

A total of 500 pictures consisting of several typical objects in kitchen places are also collected to obtain a corresponding semantic association model; 450 of which are from the SUN Database or the internet, and the other 50 pictures are collected by the authors using a camera. This paper also only retained objects that were detected more than 300 times to filter out the objects that are not often placed in kitchen places. Then, the final semantic association model for the kitchen places is obtained, which eventually consists of seven objects, as shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

The semantic association model for the kitchen places.

Taking the “bottle” as an example, its semantic correlation value with “wine glass” is 1 and the value with “bowl” is 0.694. By comparing these values, it can be concluded that the probability of “a wine glass is near a bottle” is greater than that of “an oven is near around a bottle”. In addition, according to the experimental results, the semantic relevance between “wine glass”, “bottle”, and “bowl” is obviously higher, which is apparent in our daily lives.

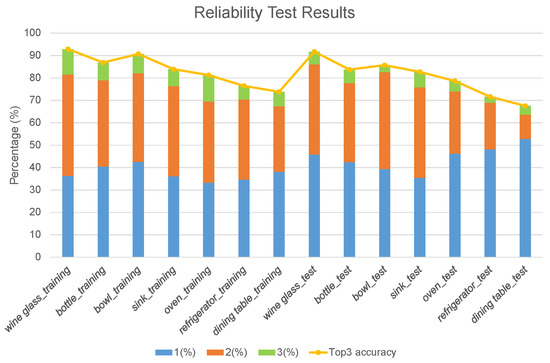

The reliability test results of the above model are shown in Figure 9. Similarly, the “Top 3 accuracy (%)” of most of the objects is over 80%, indicating that the semantic association model is highly reliable.

Figure 9.

Reliability test results of the semantic association model for the kitchen places.

4.2. Verification of the Object Navigation System

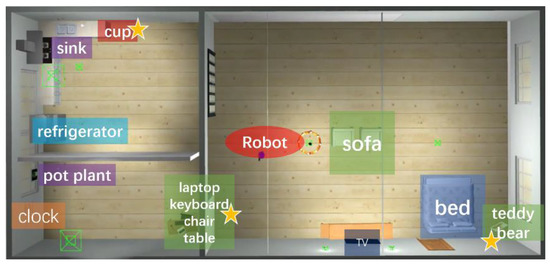

This paper built a 7 m ∗ 15 m virtual apartment in Gazebo [25], which contains some common indoor objects, as shown in Figure 10. The virtual apartment is divided into three different function regions, including the kitchen, bedroom, and office, in which the objects have been marked. The star indicates the target that the robot is looking for. The robot is a three-wheeled car equipped with a Kinect camera, whose observation angle range is set to π/3 and the observation distance range is set to 0.05 m–10 m. The robot will start at a random position, search the target autonomously, and build the environment map along the search path at the same time. In the simulation tests, each search task is executed 10 times. The searching time is limited to five minutes and the final distance between the robot and the target is limited to 1 m. If not, it will be considered a failure.

Figure 10.

The virtual apartment this paper built.

In order to measure the ability of robots in different places and prove the universality of the proposed semantic association model, three different kinds of targets are separately set for the robot. The performance of three searching methods is compared as follows:

Random Search: The robot will randomly move to search targets without using any prior knowledge, which is apparently an unintelligent method.

Traversal Search: The robot will explore every corner along the wall until it finds the target, which is approximate to an exhaustive search.

Autonomous Search: The robot will autonomously search the target according to observation and the semantic association model; that is, the strategy proposed in this paper.

The average searching time, average moving distance, and the success rate are shown in Table 2. It can easily be found that the Random Search method is very easy to fail, and the resources consumed by the robot, such as power and time, will be really high. The Traversal Search method can find the target; however, the time consumption and moving distance is higher. The Autonomous Search with prior knowledge achieved the fastest results among all three methods, which is consistent with our research goal. See Supplementary Materials for videos recorded when the robot is searching “keyboard” in Gazebo using different strategies (Videos S1–S3).

Table 2.

The performance of different searching strategies.

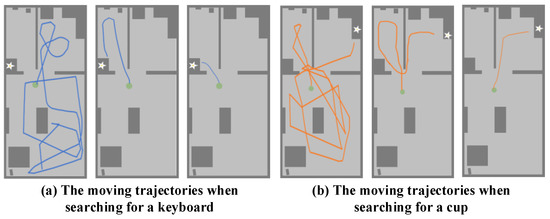

Figure 11 shows the moving trajectories of the robot when searching for the keyboard and cup, respectively, and the results coincide with Table 2. The experimental results show that the Random Search method is very time-consuming, and the robot may walk quite a long distance, but still cannot find the target. When using the Traversal method, the robot can successfully find the target after a period of searching, but the moving distance varies with different tasks, as Figure 9 shows. However, by using the autonomous object navigation strategy proposed in this paper, the robot can find the target in a relatively short time.

Figure 11.

The moving trajectories of the robot. From left to right: Random Search, Traversal Search, and Autonomous Search.

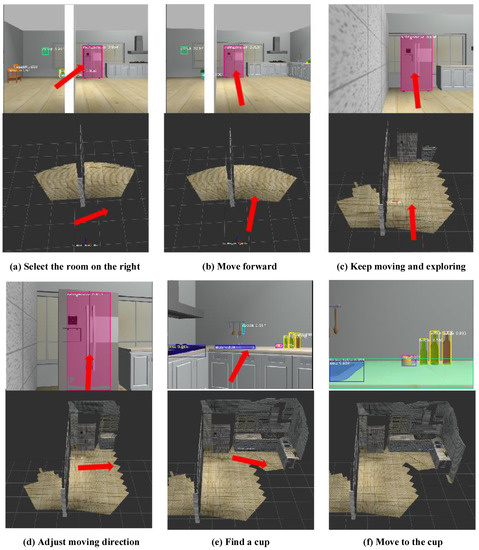

Figure 12 records the moving process of the robot when looking for the cup. The top half of each sub-graph are the scenes observed and the moving decision made by the robot. The bottom half of each sub-graph is the environment map built by the robot. At the beginning, the robot can see the refrigerator on the right, thus speculating that the cup is more likely to appear in the room on the right. Before moving to the refrigerator, the robot will first turn around to check whether there are other more related objects in the room. However, due to the limitations on its camera resolution, no more effective objects are found, so the robot chooses to move to the refrigerator and tries to find some other relevant objects. With the help of the Octomap built by itself, the robot finds that only the right side can pass when it arrives near the refrigerator, so the robot decides to make a turn, as Figure 12d shows. After turning here, the robot finds a cup and other related objects, so it finally moves to the front of the target object.

Figure 12.

The process of the robot navigating to the cup.

4.3. Verification on the Real Robot

This paper preliminarily deployed and tested the above-mentioned strategy on the Turtlebot3 with a Kinect RGB-D camera, as Figure 13 shows. To produce more reliable detection results, a camera is attached to take photos as the input of the object detector. As the main control chip of the Turtlebot3 is Raspberry Pi, which cannot process the mass calculation generated by the Mask R-CNN model and ORB-SLAM2 system in real-time, this paper adopts the computation offloading strategy proposed in [26] to achieve the aforementioned functions under the support of a local server with 2 Intel Xeon E5-2620 CPUs and 4 NVidia 2080ti GPU. The data are transferred through Wi-Fi. In order to distinctly observe the experimental results and further reduce the amount of calculation and data transferred, only the bounding box of the object which is most related to the target object in the current view is marked.

Figure 13.

Turtlebot3 robot with Kinect camera.

The average searching time, average moving distance, and success rate using different strategies for searching “mouse” in a real scenario are shown in Table 3, which are the average results of five of the same tasks. As it is difficult to precisely measure the moving distance of the real robot, the moving distance is estimated by the authors. The success rates of the Traversal strategy and the Autonomous strategy are both acceptable compared to the Random strategy. However, the robot can save a lot of time and power when using the proposed Autonomous Search, which is very advantageous in a real scenario. See Supplementary Materials for videos recorded when the robot is searching “keyboard” in a real scenario using different strategies (Videos S4–S6).

Table 3.

The performance of different strategies in real scenario.

Figure 14 shows an example of the robot searching for the “mouse” in the office. At the beginning, the robot found the “green plant” with the highest degree of association with the “mouse” in the current view, so it moved towards the “green plan” to Figure 14c. Through the observation of the surrounding environment, the robot found the “book”, which is related to the “mouse”, so it continued to move towards the “book” until it found the “computer”. The “computer” is more related with the “mouse” according to the semantic association model, so the robot decided to move towards the “computer”. Finally, the robot found the target object “mouse” next to the “computer”. The strategy proposed in this paper can make the forward direction of the robot more purposeful.

Figure 14.

Experiment in real scenario.

5. Conclusions and Future Work

Most of the existing studies about robot object navigation and environment exploration strategies are based on the environment map, which may easily fail when environment changes. In this situation, the robot needs to explore blindly and randomly, which undoubtedly affects the rapidity and efficiency, and increases the energy consumption of the robot to a certain extent. This paper proposed an efficient object navigation system for mobile robots based on semantic information, which enables the robot to find the given target efficiently and can be widely applied to the fields of intelligent old-age care, intelligent visually impaired assistance, smart homes, and so on.

Further consideration and exploration can be made in the following aspects: (a) improve the applicability of the semantic association model by using richer datasets such as ImageNet [27], so that the robot can adapt to more places; (b) adopt the online learning [28] method during robot navigation, so as to dynamically update the semantic association model; and (c) optimize and apply it to more robots and unmanned aerial vehicles, especially for those with limited computation capability and on-board energy, by making full use of the computation offloading strategy under different scene and network restrictions.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/electronics11071136/s1, Video S1: “Keyboard searching task in Gazebo using Autonomous Search”, Video S2: “Keyboard searching task in Gazebo using Random Search”, Video S3: “Keyboard searching task in Gazebo using Traversal Search”, Video S4: “Keyboard searching task in real scenario using Autonomous Search”, Video S5: “Keyboard searching task in real scenario using Random Search”, and Video S6: “Keyboard searching task in real scenario using Traversal Search”. All videos are sped up to 8×.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.G., Y.X., Y.C. and X.B.; formal analysis, Y.G., Y.X., Y.C. and M.S.O.; methodology, Y.G.; project administration, Y.G. and Y.X.; software, Y.G. and Y.C.; supervision, X.B. and M.S.O.; writing—original draft, Y.G.; writing—review and editing, X.B., B.S. and M.S.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was partially funded by the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation under grant 2020M680352, partially funded by the Scientific and Technological Innovation Foundation of Shunde Graduate School, USTB under grant 2020BH011, and partially funded by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities under grant FRF-TP-20-063A1Z. This work was also supported in part by the Distinguished Possessor Grant of the Ministry of Education of P.R. China given to Prof. Obaidat under number MS2017BJKJ003.

Data Availability Statement

“COCO dataset” at https://cocodataset.org (accessed on 12 September 2021). “SUN Database” at https://vision.cs.princeton.edu/projects/2010/SUN/ (accessed on 8 October 2021).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Lera, F.J.R.; Rico, F.M.; Higueras, A.M.G.; Olivera, V.M. A context-awareness model for activity recognition in robot-assisted scenarios. Exp. Syst. 2020, 37, e12481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Gkioxari, G.; Dollar, P.; Girshick, R. Mask R-CNN. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 2980–2988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mur-Artal, R.; Tardos, J.D. ORB-SLAM2: An Open-Source SLAM System for Monocular, Stereo, and RGB-D Cameras. IEEE Trans. Rob. 2017, 33, 1255–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Smith, R.C.; Cheeseman, P. On the Representation and Estimation of Spatial Uncertainty. Int. J. Rob. Res. 1986, 5, 56–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davison, A.J.; Reid, I.D.; Molton, N.D.; Stasse, O. Monoslam: Real-time single camera slam. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2007, 29, 1052–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Klein, G.; Murray, D. Parallel tracking and mapping for small AR workspaces. In Proceedings of the 2007 6th IEEE and ACM International Symposium on Mixed and Augmented Reality (ISMAR), Nara, Japan, 13–16 November 2007; pp. 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whelan, T.; Mcdonald, J.; Kaess, M.; Fallon, M.; Johannsson, H.; Leonard, J. Robust real-time visual odometry for dense RGB-D mapping. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Sydney, Australia, 6–10 May 2012; pp. 5724–5731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mur-Artal, R.; Montiel, J.M.M.; Tardos, J.D. ORB-SLAM: A Versatile and Accurate Monocular SLAM System. IEEE Trans. Rob. 2015, 31, 1147–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Campos, C.; Elvira, R.; Rodriguez, J.J.G.; Montiel, J.M.M.; Tardos, J.D. ORB-SLAM3: An Accurate Open-Source Library for Visual, Visual-Inertial, and Multimap SLAM. IEEE Trans. Rob. 2021, 37, 1874–1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelnasser, H.; Mohamed, R.; Elgohary, A.; Alzantot, M.F.; Wang, H.; Sen, S.; Choudhury, R.R.; Youssef, M. SemanticSLAM: Using Environment Landmarks for Unsupervised Indoor Localization. IEEE Trans. Mob. Comput. 2015, 15, 1770–1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Mottaghi, R.; Kolve, E.; Lim, J.J.; Fei-Fei, L.; Farhadi, A. Target-driven visual navigation in indoor scenes using deep reinforcement learning. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Singapore, 29 May–3 June 2017; pp. 3357–3364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Narasimhan, M.; Wijmans, E.; Chen, X.; Darrell, T.; Batra, D.; Parikh, D.; Singh, A. Seeing the Un-Scene: Learning Amodal Semantic Maps for Room Navigation. In Proceedings of the 16th European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Glasgow, UK, 23–28 August 2020; pp. 513–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Wu, Y.; Tamar, A.; Russell, S.; Gkioxari, G.; Tian, Y. Bayesian Relational Memory for Semantic Visual Navigation. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Seoul, Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 2769–2779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mousavian, A.; Toshev, A.; Fišer, M.; Košecká, J.; Wahid, A.; Davidson, J. Visual Representations for Semantic Target Driven Navigation. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Montreal, QC, Canada, 20–24 May 2019; pp. 8846–8852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- ROS. Available online: http://wiki.ros.org/ (accessed on 14 September 2021).

- Hornung, A.; Wurm, K.M.; Bennewitz, M.; Stachniss, C.; Burgard, W. Octomap: An efficient probabilistic 3D mapping framework based on octrees. Auton. Rob. 2013, 34, 189–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mask R-CNN for Object Detection and Instance Segmentation on Keras and TensorFlow. Available online: https://github.com/matterport/Mask_RCNN (accessed on 23 June 2021).

- Lin, T.-Y.; Maire, M.; Belongie, S.; Hays, J.; Perona, P.; Ramanan, D.; Dollar, P.; Zitnick, C.L. Microsoft COCO: Common Objects in Context. In Proceedings of the 13th European Conference on Computer Vision, ECCV 2014, Zurich, Switzerland, 6–12 September 2014; pp. 740–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cosenza, C.; Nicolella, A.; Esposito, D.; Niola, V.; Savino, S. Mechanical System Control by RGB-D Device. Machines 2021, 9, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- YOLOv5 in Pytorch. Available online: https://github.com/ultralytics/yolov5 (accessed on 25 March 2022).

- SSD: Single Shot MultiBox Detector. Available online: https://github.com/weiliu89/caffe/tree/ssd (accessed on 25 March 2022).

- Word2vec Tutorial-The Skip-Gram Model. Available online: http://mccormickml.com/2016/04/19/word2vec-tutorial-the-skip-gram-model (accessed on 28 November 2021).

- Yan, X.; Wang, S.; Ma, F.; Liu, Y.; Wang, J. A novel path planning approach for smart cargo ships based on anisotropic fast marching. Exp. Syst. Appl. 2020, 159, 113558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SUN Database: Scene Categorization Benchmark. Available online: https://vision.cs.princeton.edu/projects/2010/SUN/ (accessed on 8 October 2021).

- Koenig, N.; Howard, A. Design and use paradigms for Gazebo, an open-source multi-robot simulator. In Proceedings of the 2004 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Sendai, Japan, 28 September–2 October 2004; pp. 2149–2154. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Y.; Mi, Z.; Yang, Y.; Obaidat, M.S. An Energy Sensitive Computation Offloading Strategy in Cloud Robotic Network Based on GA. IEEE Syst. J. 2019, 13, 3513–3523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Hinton, G.E. ImageNet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the 26th Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS), Lake Tahoe, NV, USA, 3–6 December 2012; pp. 1097–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Li, X.; Liu, H.; Fu, Z. Online Learned Siamese Network with Auto-Encoding Constraints for Robust Multi-Object Tracking. Electronics 2019, 8, 595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).