Abstract

We will increasingly become dependent on automation to support our manufacturing and daily living, and robots are likely to take an important place in this. Unfortunately, currently not all the robots are accessible for all users. This is due to the different characteristics of users, as users with visual, hearing, motor or cognitive disabilities were not considered during the design, implementation or interaction phase, causing accessibility barriers to users who have limitations. This research presents a proposal for accessibility guidelines for human-robot interaction (HRI). The guidelines have been evaluated by seventeen HRI designers and/or developers. A questionnaire of nine five-point Likert Scale questions and 6 open-ended questions was developed to evaluate the proposed guidelines for developers and designers, in terms of four main factors: usability, social acceptance, user experience and social impact. The questions act as indicators for each factor. The majority (15 of 17 participants) agreed that the guidelines are helpful for them to design and implement accessible robot interfaces and applications. Some of them had considered some ad hoc guidelines in their design practice, but none of them showed awareness of or had applied all the proposed guidelines in their design practice, 72% of the proposed guidelines have been applied by less than or equal to 8 participants for each guideline. Moreover, 16 of 17 participants would use the proposed guidelines in their future robot designs or evaluation. The participants recommended the importance of aligning the proposed guidelines with safety requirements, environment of interaction (indoor or outdoor), cost and users’ expectations.

1. Introduction

Diversity in technology has become pervasive in everyday life. Robot designers and developers must also consider in their designs and products a wide range of potential users with a great diversity of abilities and needs. Implementing accessible robots requires a deep knowledge of interaction barriers that people could face when using each robot component, depending on their interaction characteristics, abilities and capabilities. However, most of the HRI designers and developers have limited awareness of accessibility issues, and a tool for helping them to apply this knowledge in their designs and implementations would be useful. That is why in this paper we propose a set of accessibility guidelines, to help human-robot interaction designers and developers to construct accessible robots for all.

2. Related Work

2.1. Socially Assistive Robotics

Accessibility guidelines that are evaluated in this research, mainly focus on socially assistive robotics. Socially assistive robotics (SAR) refer to robotics that present services to the users through social instead of physical interaction [1]. Assistive robots with social abilities are categorized into two types (services robots and companion robots), and it is difficult to classify most robots into one of these two categories, as the robot can be implemented to both provide services and companionship [2].

The applications of SARs have been extended to include many domains, such as health care, elderly care, education, household task, work environments and public spaces (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The Honda Asimo robot (left) and the Softbank Robotics Pepper robot (right), both are examples of humanoid robots aimed at close interaction with people [3].

The use of SARs is expected to expand highly in future due to the increment in numbers of elderly people [4].

In general, SARs in different application domains vary in their morphologies or representations to achieve the planned services. For example, robots used in mental health care applications diversify in their morphologies according to the required roles and functions of the robots, and includes zoomorphic, mechanistic, cartoon-like, humanoid representations [5]. Hence, SARs could have different interaction interfaces, where they rely on sensors and human interaction devices (HID) like a joystick, to get visual, auditory or touch/physical/movement inputs from the surrounding area and users. The robot can have a combination of sensing devices such as camera, microphone, laser sensor, touch sensors, tactile display, etc. The visual, auditory or touch/physical/movement outputs can be produced via same or different interaction interfaces, such as, speakers, LEDs, tactile display, actuators/motors.

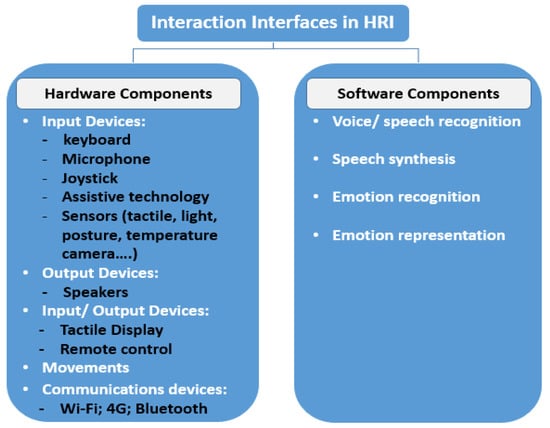

In addition to the hardware interaction interfaces, the robot may receive inputs and send outputs via software interaction interfaces such as, assistive software technologies, screen readers or receiving commands through a Wi-Fi connection. Figure 2 shows the hardware and software classification.

Figure 2.

Interaction interfaces in human-robot interaction (HRI).

2.2. Accessibility Barriers in HRI

People vary in their visual, auditory, motor and cognitive abilities and needs. These differences might be temporal, such as after surgery, or permanent, for example caused by a chronic condition, or environmental factors, such as a noisy environment. According to WebAIM [6], four types of disabilities can create accessibility barriers for users during their interaction with a computer. The same barriers can be found during the interaction with a robot in varying degrees:

2.2.1. Visual Disabilities: Three Main Visual Disabilities, Which Are

- Blindness: The World Health Organization (WHO) defined blindness as the “Profound inability to distinguish light from dark, or the total inability to see” [7], later, they modified this definition to include people who have light perception but are still less than 3/60 in the better eye [8].

- Low Vision: Is the degree of visual acuity which is defined as less than 6/18 and equal to or better than 3/60 in the better eye with best correction [9].

- Color-Blindness: “Is the inability to perceive differences in various shades of colors, particularly green and red, that others can distinguish. It is most often inherited (genetic)” [10].

People who have visual disabilities may face accessibility barriers when they try to distinguish and perceive the hardware components of the robot, the software components of robot’s display screen, and any visual signals used by the robot. Users might be using assistive technologies and its compatibility with the robot needs to be considered. Perhaps, alternatives to the assistive technologies have been built into the robot. In a study conducted to investigate the effectiveness of robotics in eliminating the barriers to collaboration between people with autism spectrum disorders (ASD) and their therapists, [11] used the Pleo robot platform [12]. Pleo has the appearance of a small dinosaur and has the size of an average cat. Pleo interacts with users through social expressive behaviors, such as showing excitement, fear and surprise, greeting the user, and imitating non-verbal sounds. Pleo’s interaction would not be accessible for individuals who have ASD and a visual disability.

2.2.2. Auditory Disabilities

People who cannot hear with thresholds of 25 decibels (dB) or better in both ears are considered to have ‘hearing loss’. Hearing loss is classified into degrees: people who have hearing loss that varies between mild to severe are considered to be ‘hard of hearing’, while profound hearing loss is considered as deafness [13].

For people who have auditory disabilities several support measures exist, from providing captions and transcripts for audio content and media players, to controlling the volume of audio content and high-quality foreground audio [14], all of which would help in making web content accessible. However, in HRI these measures might be difficult to implement. For example, not all robots have got a display screen to provide the needed textual information for HRI. An illustrative example of a robot which is difficult to interact with for people with auditory disabilities is NAO, a humanoid robot which is 56 cm tall and has 25 degrees of freedom (DOF) for its head, arms, pelvis, legs and hands [15]. NAO has pre-programed behaviors that are considered as high level functions such as, walk, dance, speech recognition and synthesis, turn, lie down and stand up, and low level functions like reading sensors and turning LEDs on and off [16]. People who have auditory disabilities will need an additional interface to receive the textual or visual information such as a display screen or to interact through sign language or a screen-based interface with NAO, bearing in mind that sign languages differ sometimes between regions and that not all users with auditory disabilities know the sign language.

2.2.3. Motor Disabilities

“Physical disabilities (sometimes called “motor disabilities”) include weakness and limitations of muscular control (such as involuntary movements including tremors, lack of coordination, or paralysis), limitations of sensation, joint disorders (such as arthritis), pain that impedes movement, and missing limbs” [14].

For people who have motor disabilities, hardware and software assistive technologies are very effective in human-computer interaction (HCI). Examples include the mouth stick and head wand for people who cannot use their hands to control the computer, a trackball mouse for web navigation, single-switch access and sip and puff switch technologies and their software to allow access to computer functionality, speech recognition and eye-tracking software and many other assistive technologies [17]. In addition, developers can support the accessibility of web content, for instance, by providing large clickable areas and control on the time limits of completing any action or process.

In HRI, robots could be designed to be operated with one hand or with minimum dexterity. If manual manipulation of controls is not possible, the robot should be controllable through vocal or speech input or even by their hardware or software assistive technologies that they used to use it in HCI. For example, a study [18] demonstrated the possibility of using a wireless intraoral control system by people with tetraplegia to control an assistive robotic arm. One of the participants had difficulties seeing the grippers’ position to grasp objects due to the distance between the assistive robotic arm and the participants’ eyes [18]. The distance between the user and the robotic arm created accessibility barrier to the user.

2.2.4. Cognitive Disabilities

According to the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) [19], cognitive, learning, and neurological disabilities encompass neurodiversity and neurological disorders, behavioral and mental health disorders that may not be neurological, and may impact any part of individual’s nervous system and control how well an individual perceives and understands information and may affect his motor skills. All of these disabilities do not necessarily mean that a person’s intelligence will be affected.

By adopting certain mechanisms, web developers could help people with cognitive disabilities during their interaction with web pages. For example, keeping a reminder of the overall web content could help people who have memory deficits, providing warning messages and instructions during and before starting a specific task would be helpful for people who have problem-solving deficits, and using icons, audio and video as a supplemental media, with structural elements like headings and list items, highlighting items and white spaces in the margins and between paragraphs and other uniting content, would decrease the accessibility barriers for people who have reading, linguistic, and verbal comprehension deficits [20]. In 2018, a robot called Silbot [21] was used to conduct a study on developing assistive robots for people who have mild cognitive disabilities and mild dementia. The robot was designed to help the users in their daily- activities like waking them up, reminding them to take medication and checking their mood. The robot has a touch screen integrated in the head, two arms to generate gestures, a camera and microphones, and a mobile base with sensors to handle the navigation process. The researchers pointed out that users can interact with the robot through voice interaction and the touch screen. The interviews with the participants revealed how robot’s arm movements, face expressions and flashing lights caused a distraction to them [21], this kind of distraction could also create accessibility barriers for people who have attention deficits.

2.3. Accessibility Laws and Guidelines for HCI

The necessity to ensure accessibility of information technology to users with different abilities and needs is well established and is often supported by regulations and legislation to guarantee accessibility. For example, Section 508 in USA [22], the European directive 2016/2102 in this regard [23] and the 2010/2012 Jodhan decision in Canada serves the purpose of making websites accessible to all [24]. Accessibility requirements in HCI have been extensively studied by researchers and industry and have led to guidelines and standards to help designers and developers create accessible software products. However, few of these guidelines can be transferred to robot design, due to the differences in physical components and application areas. Accessibility guidelines such as the Web Content Accessibility Guideline (WCAG 2.1) [25] for web content, Funka Nu guidelines [26] for mobile interfaces and BBC guidelines [27] for BBC’s digital products were designed to regulate accessibility from a software perspective. However, (WCAG 2.1) is the most comprehensive and detailed guideline and can be applied to many devices: desktops, tablets, laptops and mobiles among the three guidelines. IBM accessibility checklists [28] maintain the accessibility issue from both the software and hardware perspectives such as, web and non-web software, documentation and hardware such as, personal computers, servers and printers.

2.4. Accessibility Laws and Guidelines for HRI

Based on the systematic review of accessibility laws, regulations, standards or guidelines for HRI to guarantee designing and manufacturing of accessible robotic interfaces, and also based on the authors’ knowledge; there are no regulations or legislation, standards or guidelines specific to accessibility requirements for HRI. Some initiatives are focused on other requirements for HRI, such as safety, usability, or ethics, but not on accessibility. For instance, the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) guidelines for safety requirements for personal care robots [29] or the British Standard for BS8611 (Robots and robotic devices. Guide to the ethical design and application of robots and robotic systems) [30]. Hence, we believe that there is a need for guidelines and perhaps legislation to ensure that accessibility requirements for HRI are met for all users.

2.5. Proposed Accessibility Guidelines for HRI

Accessibility guidelines for tactile display components in HRI were presented [31], extending the authors’ research, this paper presents accessibility guidelines for HRI considering other robot devices found in the literature (including software and hardware), and the use of assistive technologies in HRI.

A scientific methodology was followed to arrive at these new guidelines:

- The main accessibility standards, guidelines and recommendations for web sites, web applications, software applications and hardware, in addition to personal user experience guidelines were studied.

- Based on these and based on the authors’ experience, the main characteristics of a different SARs interfaces were studied.

- Afterwards, six accessibility guidelines: WCAG 2.0 [25], BBC [27], Funka Nu [26], IBM [28], WAI-ARIA [32] and PUX [33] were selected to form the basis for the new guidelines. The accessibility requirements of the six guidelines were studied and analyzed, to check whether they apply to robotic interfaces or not based on the similarity with robot technology.

- Then redundant requirements were removed from the document.

- The classification applied on the final document/draft was following WCAG 2.0 and under four aspects: Perceivable, operable, understandable and general; to fit the new added accessibility requirements, where the first three aspect include accessibility requirements that users need to perceive, understand and operate robot’s hardware or software components during HRI. The rest of accessibility requirements that do not belong to the previous three aspect were grouped under general aspect. Table 1 shows the general classification of the proposed guidelines requirements. The proposed guidelines are available on (https://github.com/Malak-Qbilat/HRI-Accessibility-.git (accessed on 27 February 2021)).

Table 1. General classification of the proposed guidelines requirements.

Table 1. General classification of the proposed guidelines requirements.

3. Evaluation

The main aim of this evaluation is to assess the usability, user’s experience, user’s satisfaction and societal impact of the new proposed guidelines from developers’ and designers’ perspective as follows.

3.1. Evaluation Design

3.1.1. Objective

With the intention of conducting a heuristic evaluation of the new proposed guidelines to inspect usability, user’s experience, user’s satisfaction and societal impact issues, three experts performed the evaluation.

3.1.2. Participants

A convenience sample was selected to include participants with HRI designer or developer roles. Seventeen volunteers were enrolled in the accessibility guidelines evaluation. The participants were all HRI designers and/or developers: one expert in interaction design, one in rehabilitation robotics, two in robotics, one in social collaborative robotics, one in sociology (robotics and AI), one in user acceptance of robotics, one in deep learning, one in automated planning robotics, one in artificial intelligence applied to robotics, one in artificial intelligence applied to socially assistive robots, one in machine learning and planning, one in sociology (user-centered design and participatory design), one in electronic technology, one in multimodal human robot interaction and one in telematics engineering. Table 2 summarizes the demographic data of participants with descriptive statistics.

Table 2.

Characteristics of participants.

3.1.3. Materials

The evaluators deployed the following methods to obtain quantitative and qualitative results:

- Questionnaire interview: First a pre-test questionnaire was applied to gather participants’ demographic information. Then, participants were asked to answer the post-test questionnaire which consisted of nine 5-point Likert Scale questions with 1 being (strongly disagree) and 5 being (strongly agree). Also, three open-ended questions were structured to measure usability, user experience, user satisfaction and societal impact factors from experts’ point of view. Face to face interviews were carried out at Ghent University, Free University of Brussels and University Carlos III of Madrid. The rest of the interviews were audio-conference interviews. All interviews were audio recorded, so evaluators could refer later to participants’ feedback, especially answers to open-ended questions, where the users enriched the evaluation by exposing their experience in an informal way.

- Observations: Evaluators observed participants during the evaluation sessions, which enabled assessing the efficiency indicator (see details in Section 3.2).

- Expert evaluation: Based on the study and analysis of user recommendations by experts, the proposed guidelines were reviewed to investigate the possibility of adopting these recommendations.

3.1.4. Protocol

The evaluator conducted the following steps with each participant:

- Evaluation appointment: First, participants were contacted to appoint a date for the evaluation session and to determine whether it would be a face to face or an audio-conference interview.

- Pre-test introduction and questionnaire: At the interview, the objective of the evaluation was explained to the participant first, and then s/he was asked to provide some demographic information (see details of the questionnaire in Section 3).

- Choosing the expert role: The participant had to choose one of two tasks based on his/her experience, as follows:

- If the participant had the designer or developer role, s/he was asked to imagine designing a robot to perform a geriatric assessment through interaction with elderly people by asking them to answer questions or perform simple tasks such as walking for a few meters. The robot has a tactile display, microphone and RGB-D camera (s/he could add other necessary hardware components) in order to interact and collect data for later analysis by doctors. Additionally, s/he would design the robot following the accessibility guidelines to ensure that the robot can be used by people with different abilities.

- Otherwise, the participant was asked to watch three different videos of elderly people interacting with a socially assistive robot (CLARC) [34] to perform a geriatric assessment at a hospital where the elderlies interacted with the robot through speech and tactile channels to answer questions about their daily life routine and perform some activities as well. The participant’s task was to find all accessibility barriers during the HRI interaction in the videos based on the accessibility guidelines.

- Guidelines familiarity and performing the selected task: Then, a summarized version of the proposed guidelines was presented to the participant. They were asked to read it carefully in order to achieve the objective set in step (2). The minimum recorded time to complete the task was (5) min and the maximum time was (12.19) min, while the mean was (8.12) min.

- Post-test interview: Thereafter, the participant was asked to answer the five-point Likert Scale and 6 open-ended questions. All responses were recorded for more accuracy while studying and analyzing participants’ responses.

3.2. Evaluation Conclusions

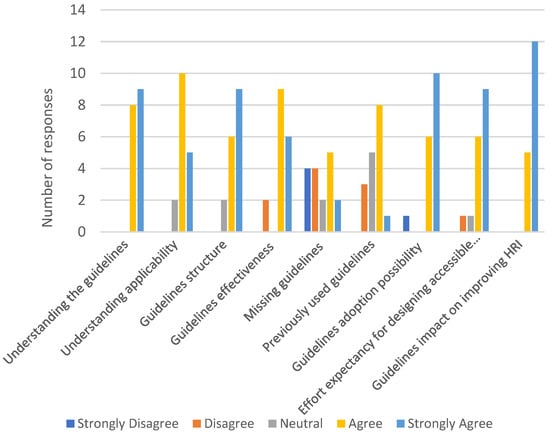

All questionnaires were checked to determine whether they were completely and properly filled with none of them being excluded from the study. The contents of interview records were transcribed as text on an excel sheet and responses to open-ended questions were analyzed according to thematic analysis of Braun and Clarke (2019). Figure 3 shows the summarized results of the nine 5-point Likert Scale questions answered by participants in the post-test questionnaire, including questions related to usability, user’s experience, user’s satisfaction and societal impact.

Figure 3.

Number of responses assigned to scale point for each question.

The responses of participants to each evaluation factor were studied repetitively, descriptive codes were extracted and linked to themes, and then themes were grouped based on their relativity to one of the indicators of the studied factors as follows:

- Usability factor: The study included four 5-point Likert Scale items (questions q1–q4 in Table 3), one open-ended question (question q2.1 in Table 3) and one objective question (question q5 at Table 3) to assess the usability factor. The following indicators were measured:

Table 3. Questions evaluating usability factor.

Table 3. Questions evaluating usability factor.- Understanding: Question 1 and question 2 were dedicated to evaluate understanding both the checkpoints (accessibility requirements) and the guidelines (techniques to achieve each accessibility requirement). All participants agreed that the checkpoints were fully understood with 15 of 17 participants understanding the guidelines completely. Two of 15 participants selected neutral. Careful analysis of their answers to the open-ended questions revealed that both participants think the guidelines should be accompanied with graphical examples. The participants also responded to an open-ended question (Question q2.1) to report some difficulties met in understanding the guidelines. They also gave recommendations to improve guidelines understanding. For instance, 7 participants recommended to enhance the guidelines with graphical practical examples.

- Guidelines structure: Question 3 revealed participants’ responses regarding the guidelines structure, where 15 of 17 participants agreed that guidelines are structured in an order easy for them to use or apply. None of the participants disagreed with this assumption. Two of 17 participants chose neutral. After analyzing their answers to open-ended questions, it was found that both participants did not oppose the current guidelines’ structure, but they preferred another structure or classification. These structures include targeted user’ characteristics where the guidelines are classified under three categories (visual, auditive and tactile) or to classify them to hardware and software guidelines.

- Effectiveness: To evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed guidelines in helping the designers and developers to design accessible robots or detect accessibility barriers, participants responded to question 4. Fifteen of 17 participants agreed that the guidelines will be helpful to design and develop accessible robots. Two of 17 disagreed with this assumption. Following the review of their answers to the open-ended questions, one participant thought applying all the guidelines is hard due to high cost; instead, the priority should be given to the guidelines that relate to characteristics of the targeted user. The other participant thought that implementing all guidelines will slow robots’ system and complicate interaction with users.

- Efficiency: In question 5, the evaluators measured the time each participant spent to accomplish the task with the mean being (8.12 min). The evaluators found the required time to accomplish the task reasonably to fall between (5–12.19) min.

- User’s experience factor: The study dedicated two 5-point Likert Scale items (questions q6 and q7 in Table 4) for the user experience factor. The following indicators were measured:

Table 4. Questions evaluating user experience factor.

Table 4. Questions evaluating user experience factor.- Missing guidelines: Eight of 17 participants thought there were some accessibility aspects missing in the proposed guidelines (question 6). They highlighted some missing aspects such as appropriate distance for interaction between user and robot. Most of the participants’ recommendations in the open-ended questions were not related to accessibility alone but to different factors such as usability and user acceptation; for instance, guidelines for robot gender preferences.

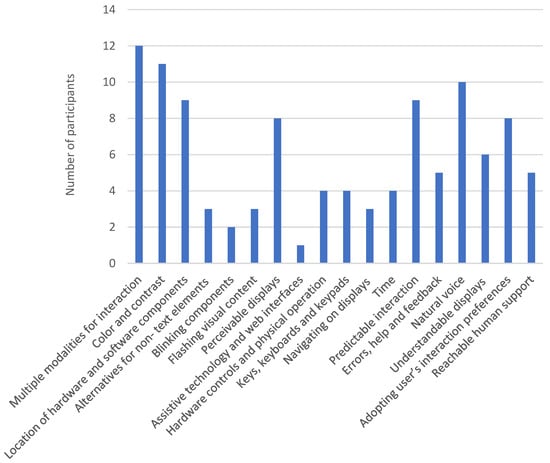

- Previously used guidelines: With the purpose of assessing participants’ familiarity with the guidelines, participants responded about whether they considered these aspects in their previous designs or evaluations, even when they had not considered accessibility issues (question 7). None of the 17 participants had completely applied all the proposed guidelines in her/his designs or evaluations. One of 17 participants said that he had never applied any of them. A total of 72% of the proposed guidelines have been applied by less than or equal to 8 participants for each guideline. All the guidelines have been applied at least once due to participants’ knowledge of HCI accessibility. Figure 4 shows the number of participants who previously applied each guideline.

Figure 4. Number of participants who previously used each guideline.

Figure 4. Number of participants who previously used each guideline.

- User’s satisfaction factor: The study dedicated two 5-point Likert Scale items (questions q8 and q9 at Table 5) for user satisfaction. The following indicators were measured:

Table 5. Questions evaluating user satisfaction factor.

Table 5. Questions evaluating user satisfaction factor.- Guidelines adoption possibility: Responses on question 8 show that the majority (16 of 17 participants) would use the proposed guidelines in their future robot designs or evaluations. Only 1 of 17 participants would not use the proposed guidelines. However, analysis of his answers to the open-ended questions showed that the participant thought applying all the proposed guidelines contradicts with cost, business and users’ expectations issues.

- Effort expectancy: The majority (15 of 17 participants) agreed that they think the design of accessible robots for all will require more effort. One of 17 participants selected neutral, while 1 of 17 participants disagreed with this assumption. After studying their answers extensively, it was concluded that they thought the design and implementation of an accessible robot can be achieved by considering business, user’s expectations and cost for each robotic product separately, rather than complying with general accessibility guidelines (question 9).

- Societal impact factor: The study dedicated one 5-point Likert Scale item (question q10 in Table 6) for the societal impact factor. The following indicator was measured: Quality of life/Importance: All participants agreed on the importance of considering accessibility guidelines in the inclusive design of robots (questions 10).

Table 6. Question evaluating societal impact factor.

Table 6. Question evaluating societal impact factor.

Participants’ recommendations: In question 11, participants were asked to recommend any ideas to develop the proposed guidelines. Most of the recommendations provided by the participants were not related to the accessibility factor rather to usability and user acceptation such as adding guidelines for psychological aspects. Related recommendations were extracted from users’ feedback to improve the proposed guidelines, where participants suggested different classifications of the proposed guidelines according to user characteristics, robot characteristics, designer or developer characteristics. These include hardware and software guidelines or functional and non-functional guidelines.

The recommendations related to applying new classifications will convert these guidelines into configured guidelines, which would help avoiding slowness, boresome and difficulty in the interaction process with the robot. The configured guidelines will comply with the cost, business and user’s expectations issues too.

Other recommendations addressed tagging each checkpoint with a level of priority and prioritizing safety requirements, adding graphical examples to enhance the clarification of checkpoints and guidelines, and defining all mentioned abbreviations. Additionally, the recommendations tackle enriching the proposed guidelines with guidelines related to hardware aspects, emotional aspects in case they can serve accessibility, appropriated distance for interaction, environment accessibility requirements and user adaptation or adapting the robot to the user issues.

Other recommendations suggest developing design methodology document besides the proposed guidelines to allow more focus on the flow of interaction. Finally, the recommendations propose an interactive online version of the proposed guidelines and to revise the proposed guidelines by an English language expert.

4. Conclusions and Further Research

In this work we proposed accessibility guidelines for HRI. Six main accessibility guidelines that manipulate accessibility requirements for software and hardware and user experience in HCI were considered as basis for the proposed accessibility guidelines for HRI. A scientific methodology was followed to study and analyze the requirements of the six guidelines and the robotic interfaces’ characteristics of SARs. Only the applicable requirements to robotic interfaces were selected. An evaluation was conducted that included designers, developers and researchers in many fields that have a direct relation to robotic technology and HCI with the purpose to bridge the existing gaps in the proposed guidelines based on collected feedback. The obtained quantitative reults showed that the majority (15 of 17 participants) agreed with the guidelines being useful for them to develop accessible robots. None of the participants had followed all the proposed guidelines in her/his previous designs, while 72% of the proposed guidelines have been applied by less than or equal to 8 participants for each guideline. Moreover, (16 of 17 participants) would use the proposed guidelines in their future robot designs or evaluation.

By considering participants’ recommendations, a usable configured guidelines for designing accessible robotic interfaces will be published online, which should guide. The user easily without preparation or training. Moreover, the configured guidelines will be implemented in robot’s interfaces and real users will be involved in the second evaluation of the configured guidelines.

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft, M.Q., A.I.; Writing—review & editing T.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work has been partially funded by the EU ECHORD++ project (FP7-ICT-601116), and the UMA18-FEDERJA-074, the AT17-5509-UMA and the CSO2017-86747-R Spanish projects.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Universidad Carlos III de Madrid (protocol code CEI21_03_IGLESIAS_Ana María/19 February 2021.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data from questionnaires is contained within the article and in the different tables. The proposed guidelines are available in a publicly accessible repository that does not issue DOIs (the data can be found here: (https://github.com/Malak-Qbilat/HRI-Accessibility-.git (accessed on 27 February 2020)).

Acknowledgments

The authors warmly thank the persons involved in the evaluation process for their participation in this research and their valuable feedback.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Feil-Seifer, D.; Matarić, M.J. Toward Socially Assistive Robotics for Augmenting Interventions for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders. Springer Tracts Adv. Robot. 2009, 54, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heerink, M.; Kröse, B.; Wielinga, B.; Evers, V. Measuring the Influence of Social Abilities on Acceptance of an Interface Robot and a Screen Agent by Elderly Users. People Comput. XXIII Celebr. People Technol. Proc. HCI 2009, 2009, 430–439. [Google Scholar]

- Asimo Meets Pepper: Honda and Softbank Partnering in Robots. Available online: https://phys.org/news/2016-07-asimo-pepper-honda-softbank-partnering.html (accessed on 26 November 2020).

- Kim, J.; Kumar Mishra, A.; Limosani, R.; Scafuro, M.; Cauli, N.; Santos-Victor, J.; Mazzolai, B.; Cavallo, F. Control Strategies for Cleaning Robots in Domestic Applications: A Comprehensive Review. Int. J. Adv. Robot. Syst. 2019, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riek, L.D. Robotics Technology in Mental Health Care. Artif. Intell. Behav. Ment. Health Care 2015, 185–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WebAIM: Visual Disabilities-Introduction. Available online: https://webaim.org/articles/visual/ (accessed on 6 June 2020).

- WHO. Blindness and Deafness; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Change the Definition of Blindness. Available online: https://www.who.int/blindness/Change%20the%20Definition%20of%20Blindness.pdf (accessed on 3 February 2021).

- WHO | Priority Eye Diseases. Available online: https://www.who.int/blindness/causes/priority/en/index4.html (accessed on 14 June 2020).

- Blindness: Causes, Type, Treatment & Symptoms. Available online: https://www.medicinenet.com/blindness/article.htm (accessed on 29 November 2020).

- Kim, E.; Paul, R.; Shic, F.; Scassellati, B. Bridging the Research Gap: Making HRI Useful to Individuals with Autism. J. Human-Robot Interact. 2012, 1, 26–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernaeus, Y.; Håkansson, M.; Jacobsson, M.; Ljungblad, S. How Do You Play with a Robotic Toy Animal? A Long-Term Study of Pleo. In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Interaction Design and Children, IDC 2010, Barcelona, Spain, 9–12 June 2010; pp. 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deafness and Hearing Loss. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/deafness-and-hearing-loss (accessed on 19 June 2020).

- Diverse Abilities and Barriers | Web Accessibility Initiative (WAI) | W3C. Available online: https://www.w3.org/WAI/people-use-web/abilities-barriers/#auditory (accessed on 20 June 2020).

- Gouaillier, D.; Hugel, V.; Blazevic, P.; Kilner, C.; Monceaux, J.; Lafourcade, P.; Marnier, B.; Serre, J.; Maisonnier, B. Mechatronic Design of NAO Humanoid. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Kobe, Japan, 12–17 May 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pot, E.; Monceaux, J.; Gelin, R.; Maisonnier, B.; Robotics, A. Choregraphe: A Graphical Tool for Humanoid Robot Programming. Proc.-IEEE Int. Work. Robot Hum. Interact. Commun. 2009, 46–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WebAIM: Motor Disabilities-Assistive Technologies. Available online: https://webaim.org/articles/motor/assistive (accessed on 23 June 2020).

- Andreasen Struijk, L.N.S.; Egsgaard, L.L.; Lontis, R.; Gaihede, M.; Bentsen, B. Wireless Intraoral Tongue Control of an Assistive Robotic Arm for Individuals with Tetraplegia. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2017, 14, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diverse Abilities and Barriers | Web Accessibility Initiative (WAI) | W3C. Available online: https://www.w3.org/WAI/people-use-web/abilities-barriers/#cognitive (accessed on 24 June 2020).

- WebAIM: Cognitive Disabilities-Design Considerations. Available online: https://webaim.org/articles/cognitive/design (accessed on 4 July 2020).

- Law, M.; Sutherland, C.; Ahn, H.S.; Macdonald, B.A.; Peri, K.; Johanson, D.L.; Vajsakovic, D.-S.; Kerse, N.; Broadbent, E. Developing Assistive Robots for People with Mild Cognitive Impairment and Mild Dementia: A Qualitative Study with Older Adults and Experts in Aged Care. BMJ 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IT Accessibility Laws and Policies | Section508.gov. Available online: https://www.section508.gov/manage/laws-and-policies (accessed on 30 July 2020).

- EUR-Lex-32016L2102-EN-EUR-Lex. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?qid=1596098310471&uri=CELEX:32016L2102 (accessed on 30 July 2020).

- Internet Accessibility | Samuelson-Glushko Canadian Internet Policy and Public Interest Clinic (CIPPIC). Available online: https://cippic.ca/fr/node/128422#canadian (accessed on 30 July 2020).

- Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) 2.1. Available online: https://www.w3.org/TR/WCAG21/#wcag-2-layers-of-guidance (accessed on 30 July 2020).

- Mobile Guidelines-Funka. Available online: https://www.funka.com/en/our-assignments/research-and-innovation/archive---research-projects/mobile-guidelines/ (accessed on 26 February 2020).

- BBC-Future Media Standards & Guidelines-Accessibility Guidelines v2.0. Available online: https://www.bbc.co.uk/guidelines/futuremedia/accessibility/ (accessed on 30 July 2020).

- IBM Human Ability and Accessibility Center | Developer Guidelines. Available online: https://www.ibm.com/able/guidelines/index.html (accessed on 30 July 2020).

- ISO-ISO 13482:2014-Robots and Robotic Devices—Safety Requirements for Personal Care Robots. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/53820.html (accessed on 1 December 2020).

- British Standard BS 8611: Robots and Robotic Devices. Guide to the Ethical Design and Application of Robots and Robotic Systems–Explore AI Ethics. Available online: https://www.exploreaiethics.com/guidelines/bs-86112016/ (accessed on 20 December 2020).

- Qbilat, M.; Iglesias, A. Accessibility Guidelines for Tactile Displays in Human-Robot Interaction. A Comparative Study and Proposal; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WAI-ARIA Authoring Practices 1.1. Available online: https://www.w3.org/TR/wai-aria-practices-1.1/ (accessed on 26 November 2020).

- Personal User Experience (PUX) Recommendations and Lessons Learned. Available online: https://gpii.eu/pux/guidelines/ (accessed on 3 February 2021).

- Bandera, P.; Bustos, L.V.; Calderita, A.; Dueñas, F.; Fernandez, R.; Fuentetaja, A.; Garcia Olaya, F.J.; Garcia-Polo, J.C.; Gonzalez, A.; Iglesias, L.J.; et al. CLARC: A Robotic Architecture for Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment. Proc. XVII Workshop of Physical Agents. Available online: http://waf2016.uma.es/web/proceedings.pdf (accessed on 29 August 2020).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).