Abstract

Unmanned aerial vehicles are gaining popularity in an ever-increasing range of applications, mainly because they are able to navigate autonomously. In this work, we describe a simulation framework that can help engineering students who are starting out in the field of aerial robotics to acquire the necessary competences and skills for the development of autonomous drone navigation systems. In our framework, drone behavior is defined in a graphical way, by means of very intuitive state machines, whereas low-level control details have been abstracted. We show how the framework can be used to develop a navigation system proposal according to the rules of the “ESII Drone Challenge” student competition. We also show how the proposal can be evaluated in different test scenarios.

1. Introduction

Unmanned aerial vehicles (or simply drones) have become immensely popular over the last few years. In addition to the purely recreational use of these devices, there are a huge range of applications that can benefit from their use. In some of these applications the flight of the drone is controlled by a human pilot, but it is more and more common for them to navigate by themselves, in an autonomous way. Therefore, the design of autonomous navigation systems for drones is a critical technical challenge nowadays.

Autonomous navigation involves different tasks, including drone localization, scenario mapping, and path planning, without forgetting obstacle avoidance. A wide variety of techniques for autonomous drone navigation can be found in the literature, ranging from those based on computer vision systems [1] (supported by cameras) to those based on the use of laser or LiDAR (light detection and ranging) sensors [2], as well as the use of GPS (global positioning system) and IMUs (inertial measurement units), and different combinations of all these types of onboard equipment [3].

It becomes necessary to have development platforms that facilitate the acquisition of basic competences and skills for programming this kind of systems. For this purpose, popular drone manufacturers such as DJI and Parrot provide powerful SDKs (Software Development Kits) for controlling drones that are available for different programming languages [4,5]. However, the use of these SDKs usually requires a deep knowledge of the drone platform used as well as advanced programming skills in the corresponding programming language (Java, Phyton, C++, etc.).

As an alternative, MATLAB [6], Simulink, and Stateflow provide support for deploying flight control algorithms for commercial drones, from professional devices (such as “Pixhawk” autopilots [7]) to recreational toys (such as Parrot or DJI Ryze Tello minidrones). They integrate the well-known “model-based design” methodology [8], which has proven to be very appropriate for the design of cyber-physical systems. This methodology basically relies on graphical tools to develop a system model whose behavior is simulated before going into production.

In the context of STEAM (Science, Technology, Engineering, the Arts and Mathematics) education, some of the initiatives that have emerged for children to get started in programming allow them to easily program drones. In the same way as the quintessential STEAM language, namely Scratch [9], they are mainly block-based visual programming environments. This is the case of Tinker [10], DroneBlocks [11], and AirBlock [12]. Card-based programming has also been proposed for controlling drones [13]. All these initiatives (mainly aimed at children or teens) logically have many limitations when we wish to define a precise behavior for the drone.

There are also some high-level mission planning applications for autonomous drones, such as the popular open-source ArduPilot Mission Planner [14] and the commercial UgCS solution [15]. These applications allow the user to directly program the route or path to be followed by the drone, usually by indicating the set of waypoints to cover, but not to program a strategy for the drone to define its route itself.

In this context, we have deployed a simulation framework for the development and testing of autonomous drone navigation systems that can help future engineers to acquire competences and skills in the field of aerial robotics. Basically, the programmer makes use of Stateflow to define a particular drone behavior, which can then be tested in Gazebo [16], which is a realistic robotics simulation tool [17,18] included in the popular Robot Operating System (ROS) [19].

It should be pointed out that in this research field other authors have proposed similar development frameworks. This is the case of the open-source Aerostack software framework [20] and the research project introduced in [21]. However, these proposals, which provide great functionality, usually exhibit a level of complexity not suitable for students who are new to aerial robotics.

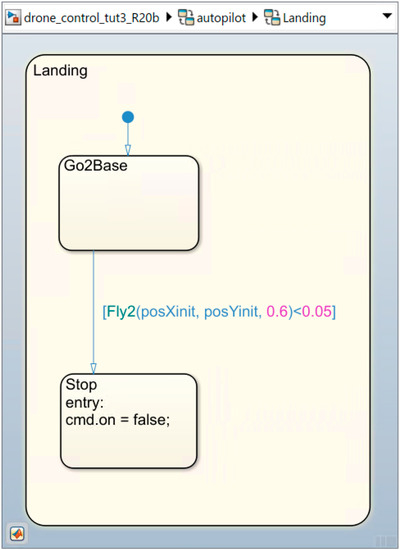

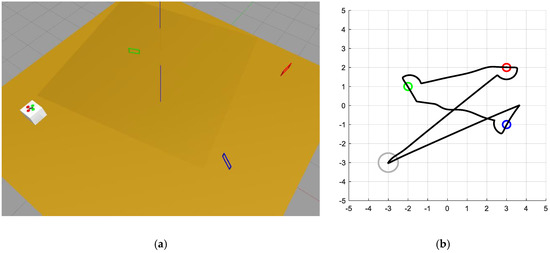

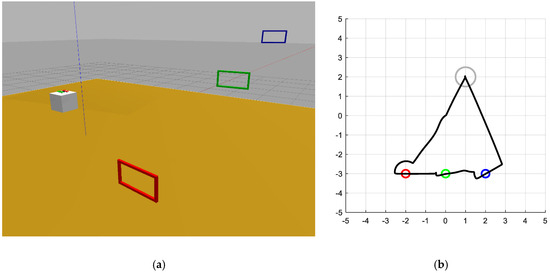

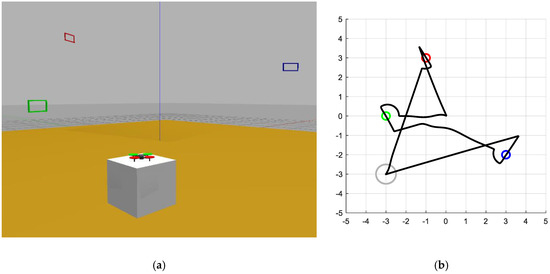

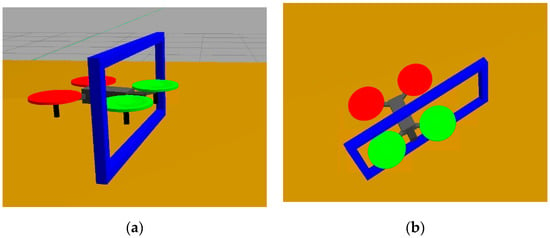

In the last few academic years the School of Computer Science and Engineering of the University of Castilla-La Mancha [22] has used the framework described in this work to organize several editions of the “ESII Drone Challenge” [23], which is a drone programming competition focused on promoting skills related to computer programming and mobile robotics among secondary school students in the Spanish region of Castilla-La Mancha. The specific challenge consists in programming a quadcopter (one of the most popular drone types) so that it can take off from a base, go through several colored floating frames (see Figure 1) in a specific order, and finally land at the starting point. The navigation system proposed by each student team is evaluated in different scenarios, in which the position and orientation of the frames and the drone itself are unknown a priori.

Figure 1.

Drone simulator developed in Gazebo. Two shots taken from different points of view at the moment the quadcopter goes through the blue frame: (a) lateral view; (b) top view.

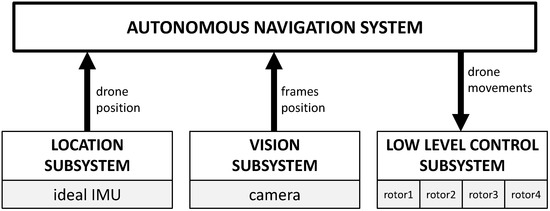

As is shown in Figure 2, the autonomous drone navigation system is built on top of three subsystems integrated into the framework. The location subsystem provides the position and orientation of the drone in the scenario, for which it uses an ideal IMU. The vision subsystem provides the relative position of the frames with respect to the drone itself. This information is extracted from the images obtained by a fixed built-in camera located on the front of the drone. Finally, the low-level control subsystem acts on the rotors to keep the drone stabilized in the air, or to execute basic maneuvers.

Figure 2.

Dependences between the subsystems composing the framework.

The rest of this paper is structured as follows. Section 2 presents a general description of the complete development and test framework, focusing on the interaction between the navigation system and the location, vision, and control subsystems. The internal implementation of these subsystems can be found in [24]. Then, and for illustrative purposes, Section 3 describes the development of a simple navigation system proposal according to the rules of the above-mentioned student competition, and Section 4 studies its behavior in various test scenarios. After that, and as a possible practical application of the proposed simulation framework, Section 5 briefly presents the “ESII Drone Challenge” contest. The interested reader can find more details about different editions of this competition in [24]. Finally, Section 6 contains our conclusions and lines for future work.

2. Simulation Framework Overview

The development and test framework is supported by two different platforms (see Supplementary Materials). Firstly, we have a drone model (Figure 1) based on Gazebo which incorporates a plugin that implements the low-level control subsystem. The simulator is completed with the scenario, which includes a game tatami, three colored floating frames and the takeoff and landing base.

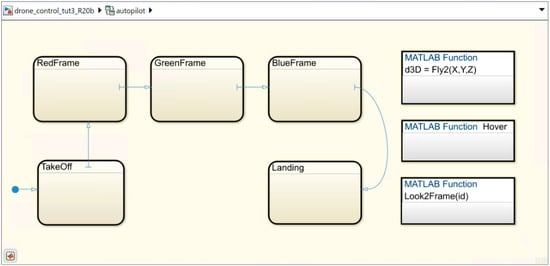

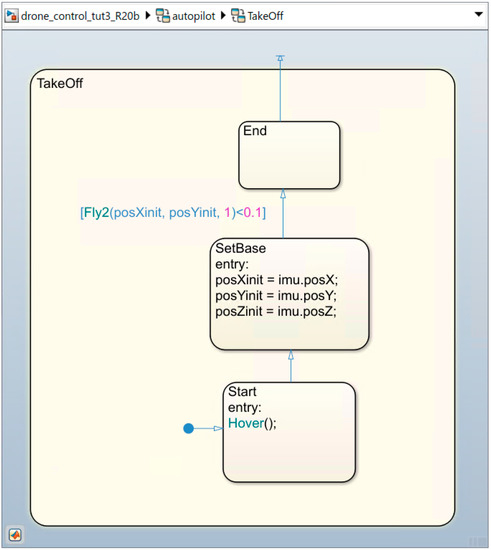

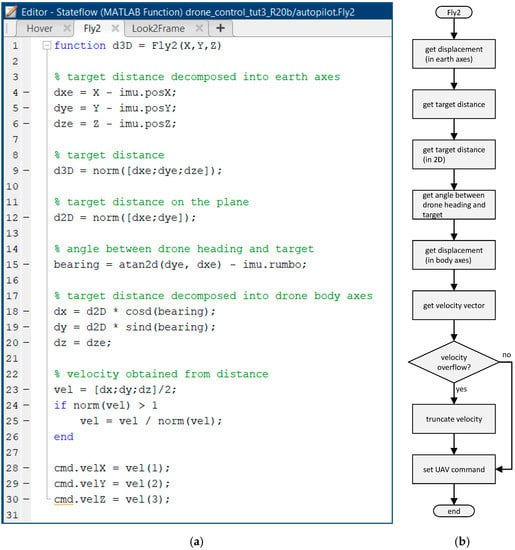

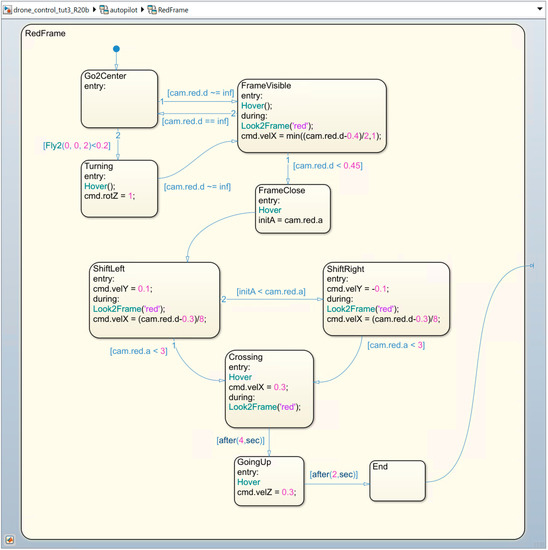

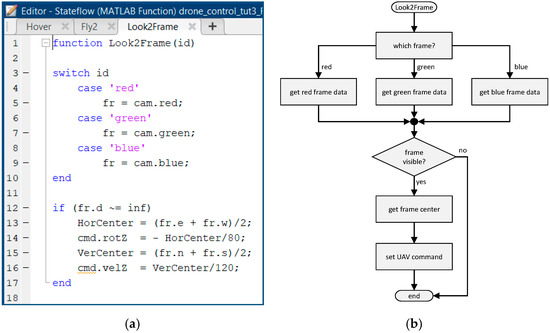

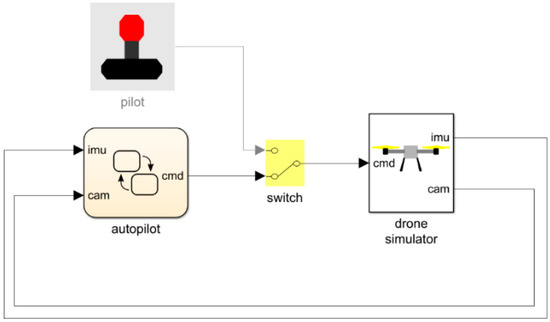

Secondly, we have a Simulink component (Figure 3) containing the navigation system (implemented by means of a Stateflow state machine) and the vision subsystem, which continuously processes the images coming from the camera and is implemented by means of MATLAB functions. The location subsystem does not require complex processing, since we work in a simulated scenario and it is only necessary to transmit data from Gazebo to Simulink.

Figure 3.

Autonomous navigation system developed in Simulink: the autopilot block is the Stateflow state machine implementing the navigation system; the pilot block manages a joystick in case of manual navigation; the switch block allows the change between autonomous and manual flight; and the drone simulator block incorporates the vision subsystem, as well as the interaction with Gazebo.

The two platforms (Gazebo and Simulink) exchange information by means of topics, which basically are information flows supported by ROS in/from which nodes (executable code) can publish/receive data by subscription. In the following subsections, we detail the three framework subsystems and their interfaces with the navigation system.

2.1. Location Subsystem

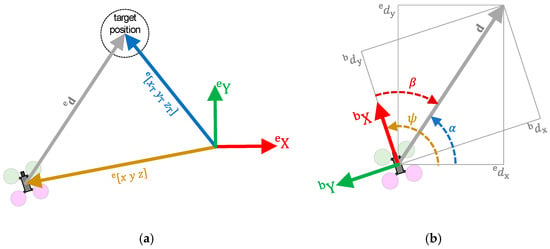

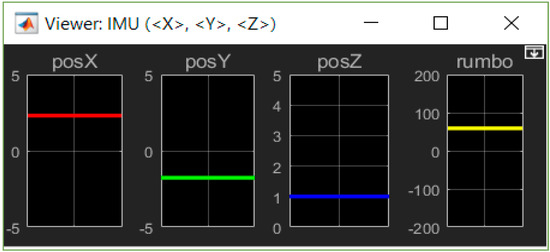

Let be the earth coordinate system, where the and axes are located on the floor (in the center of the simulated scenario), and the axis remains vertical, so that . In the same way, let be the internal quadcopter (body) coordinate system, equally satisfying . Let vector be the drone position according to the earth coordinate system, and let vector be the drone orientation with respect to the (roll), (pitch) and (yaw) axes of the earth. Let and be, respectively, the linear and angular velocities with respect to the body coordinate system. Thus, the complete state of the drone is defined by means of the vector Gazebo continuously publishes, on an ROS topic, a vector containing the quadcopter position and orientation. Simulink is subscribed to that topic, so that this information is available for the autopilot Stateflow block through the input bus (see Figure 3). In this way, programmers can use this information to develop their autonomous navigation systems. This information is also displayed by means of a Simulink viewer (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Simulink viewer showing IMU information .

2.2. Vision Subsystem

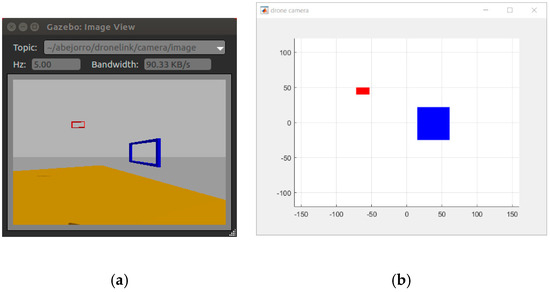

Our simulated drone is equipped with a built-in camera on its front, which provides images at a refresh rate of . The framework processes these images and provides the navigation system with information about the position of the red, green, and blue floating frames, through a 3-component () bus. More specifically, each frame is given by six components, that is, . The first components indicate the horizontal and vertical limits of the projection of the frame on the image. These limits satisfy and . If the frame is not projected on the image, these parameters take the value . If the frame is completely displayed on the image, then the vision subsystem can estimate its position (since its size is known), thus providing two additional components, namely the approximate distance from the camera () and the horizontal tilt (). The details of implementing this process can be found in [24]. From the autopilot Stateflow block point of view, this information is encoded and received through the cam input bus (see Figure 3).

Figure 5 shows an example of video processing. The raw image obtained by the drone camera is shown on the left, and the way in which the vision subsystem isolates the pixels from the colors of the frames and delimits their position by means of bounding rectangles is shown on the right. Since in this example the red and blue rectangles are shown completely, the subsystem calculates and provides their estimated position. The data resulting from this processing is displayed in Table 1.

Figure 5.

Example of video image processing: (a) original image captured by the drone camera; (b) rectangles delimiting the frames during the processing.

Table 1.

Data obtained by the vision subsystem for the example shown in Figure 5.

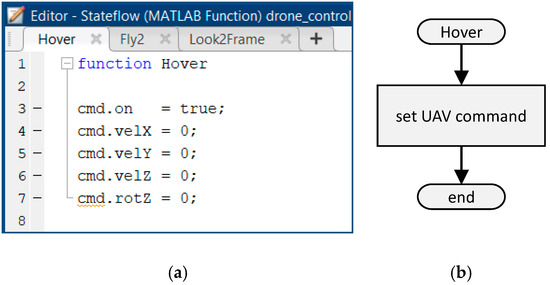

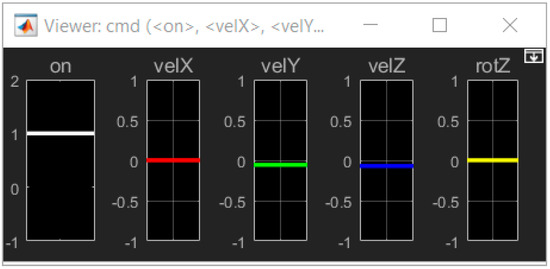

2.3. Low-Level Control Subsystem

The low-level drone control has been implemented by applying the state-space theory of linear time-invariant systems [25]. This control is responsible for turning on and off the four drone engines and managing their angular velocity to stabilize the drone in the air, as well as tracking a reference , which corresponds to the drone’s forward velocity (in all axes) and angular velocity (in the axis). In [24] the equations of motion, their linearization, and the feedback control implemented are described in detail. From the point of view of the autopilot Stateflow block, this information is encoded and sent through the cmd output bus (see Figure 3), as well as being displayed by means of a Simulink viewer (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Simulink viewer showing the commanded velocity reference vector .

5. Practical Application

“ESII Drone Challenge” is a contest for high school students. Each team must improve the simple navigation system described in Section 3. Participants are encouraged to choose their own strategy, stimulating their creativity. To evaluate the quality of the proposals, they are tested in different scenarios, similarly to what has been done in Section 4 for the baseline system.

The contest has an initial phase, which lasts several weeks, in which the enrolled teams must develop their proposals in their respective schools. Students can access to the contest “official” blog, which contains a set of video tutorials organized in several categories (Figure 18). Through these tutorials, the organization provides detailed instructions for installing and configuring the working environment and gives advice and suggestions for the development of the proposals. Video tutorials are complemented by a traditional “FAQ” section.

Figure 18.

Examples of video tutorials available on the competition website: (a) Horizontal drone movement; (b) How to cross a frame.

The final phase takes place in the facilities of the School of Computer Science and Engineering. During the first part of this phase, teams test their navigation systems in several different scenarios, and they can made last-time tunings to their implementations (Figure 19).

Figure 19.

Participants tuning their proposals before the evaluation of the judges: (a) laboratory; (b) team working.

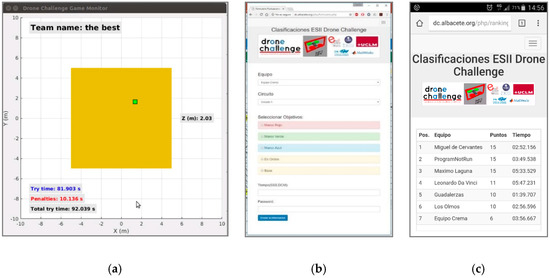

Later, all the proposals are frozen, and three of the previous scenarios are randomly chosen. Student proposals are then tested in the selected scenarios, under the supervision of the competition judges. A supporting application, the “Game Monitor” (Figure 20a), allows the judges to measure the time required to complete each try. It is a separated Simulink application that connects to the drone simulator (in Gazebo) to provide the time the drone engines are on. This tool is also in charge of checking whether the drone exits the flying scenario (a cube), since this situation must be penalized, and whether the try has reached the available time (set to ).

Figure 20.

Competition supporting applications: (a) scenario top view with statistics; (b) judge view; (c) ranking view.

Apart from the “Game Monitor”, a small client-server application (Figure 20b) was developed for the final phase so that, while the competition judges are assessing proposals (Figure 21a), participants can check their “virtual” place in an instantaneous ranking (Figure 20c). To have this ranking updated in real time, each judge uses a smartphone to fill in a web form with the results of each try and sends this information immediately to the server.

Figure 21.

Different moments of the competition: (a) judges evaluating student proposals; (b) award ceremony.

Finally, although student proposals are developed and tested by simulation, the prize is a commercial drone for each one of the components of the winner team (Figure 21b). It is worth mentioning that the results of the survey conducted after the second edition of the competition [24] indicate that participant students had a very positive opinion about the simulation framework.

6. Conclusions and Future Work

In this work, we have described a simulation framework for the development and testing of autonomous drone navigation systems. We consider that this tool can greatly facilitate the acquisition of competences and skills for engineering students who are starting out in the field of aerial robotics. This is because, unlike similar tools, the framework does not require an in-depth knowledge of robotics or programming, and drone behavior is mainly defined in a graphical way, by means of very intuitive state machines. Additionally, low-level control details have been abstracted, so that the programmer is only required to be familiar with a simple interface for receiving drone states and camera information and for sending navigation commands.

We have also shown, through a simple example, how we can use this framework to develop a navigation system proposal. In particular, the example presented is inspired by the “ESII Drone Challenge” student competition. A possible (and non-optimized) implementation for a navigation system meeting the objectives of this competition has been detailed. Additionally, we have outlined how this simple proposal could be evaluated in different test scenarios.

Future work can be undertaken along many different lines. One such line is related to enhancing the proposed navigation system. Firstly, it is necessary to improve the scenario exploration process, as inspecting the environment from its center is a very limited behavior that presents problematic situations. For example, the desired frame may be in the center, but at a different height. Instead, the drone could memorize the regions it has inspected and those that are still pending. Furthermore, the drone is currently only aware of the relative position of its target (either the center of the scenario or a colored frame). It would be useful to consider the possible need to avoid an obstacle (another frame) in the attempt to reach its destination. In general, it would be more appropriate to perform a collective analysis of the frames, and even to memorize the position of non-target frames, with the purpose of speeding up their localization when they have to be passed through later.

Secondly, improvements could be made to the quadcopter model. The image processing system could study the perspective of the captured frames, thus improving the accuracy of their estimated position and orientation to avoid unnecessary lateral displacements. A more thorough analysis of the image could also be carried out to identify and locate various types of targets to be reached or hazards to be avoided. In addition, apart from the basic IMU, the drone could incorporate a LiDAR sensor [26], which would help to estimate the position of the obstacles around it. This type of systems is supported natively in Gazebo, so its incorporation would be relatively simple. All this would allow us to consider more complex and realistic scenarios for the development of autonomous navigation systems with greater applicability.

Finally, it is desirable to complement the simulator with real drones moving through real scenarios, validating the developed navigation system. The model-based design methodology supported in MATLAB/Simulink simplifies this process, culminating in the development of the final product. In this way, the proposed framework would acquire a much more attractive dimension that would encourage the research spirit in the students and promote technical curricula in the development of autonomous navigation systems.

Supplementary Materials

Interested readers can access to MATLAB/Simulink and ROS/Gazebo implementations in GitHub: https://github.com/I3A-NavSys/drone-challenge.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.C. and A.B.; data curation, R.C. and A.B.; formal analysis, R.C. and A.B.; funding acquisition, R.C. and A.B.; investigation, R.C. and A.B.; methodology, R.C. and A.B.; project administration, R.C. and A.B.; resources, R.C. and A.B.; software, R.C. and A.B.; validation, R.C. and A.B.; visualization, R.C. and A.B.; writing—original draft, R.C. and A.B.; writing—review & editing, R.C. and A.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Spanish Ministerio de Ciencia, Innovación y Universidades (MCIU) and the European Union (EU) under grant RTI2018-098156-B-C52, and by the Junta de Comunidades de Castilla-La Mancha (JCCM) and the EU through the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF-FEDER) under grant SBPLY/19/180501/000159.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Aguilar, W.G.; Salcedo, V.S.; Sandoval, D.S.; Cobeña, B. Developing of a Video-Based Model for UAV Autonomous Navigation. Cyberspace Data Intell. Cyber Living, Syndr. Health 2017, 720, 94–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Wang, M.; Qian, C.; Huang, C.; Xia, Y.; Song, M. Lidar-based SLAM and autonomous navigation for forestry quadrotors. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE CSAA Guidance, Navigation and Control Conference (CGNCC), Xiamen, China, 10–12 August 2018; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Opromolla, R.; Fasano, G.; Rufino, G.; Grassi, M.; Savvaris, A. LIDAR-inertial integration for UAV localization and mapping in complex environments. In Proceedings of the 2016 International Conference on Unmanned Aircraft Systems (ICUAS), Arlington, VA, USA, 7–10 June 2016; pp. 649–656. [Google Scholar]

- DJI, DJI Developer. Available online: https://developer.dji.com/mobile-sdk/ (accessed on 19 October 2020).

- Parrot, “Parrot SDK”. Available online: https://developer.parrot.com/ (accessed on 19 October 2020).

- MathWorks, “MATLAB”. Available online: https://www.mathworks.com/products/matlab.html. (accessed on 19 October 2020).

- MathWorks. PX4 Autopilots Support from UAV Toolbox. Available online: https://www.mathworks.com/hardware-support/px4-autopilots.html (accessed on 29 November 2020).

- Jensen, J.C.; Chang, D.H.; Lee, E.A. A model-based design methodology for cyber-physical systems. In Proceedings of the 2011 7th International Wireless Communications and Mobile Computing Conference, Istanbul, Turkey, 4–8 July 2011; pp. 1666–1671. [Google Scholar]

- MIT Media Lab. Scratch Website. Available online: https://scratch.mit.edu/ (accessed on 19 October 2020).

- Tinker. Tinker Website. Available online: https://www.tynker.com/ (accessed on 19 October 2020).

- DroneBlocks. DroneBlocks Website. Available online: https://www.droneblocks.io (accessed on 19 October 2020).

- Makeblock. Makeblock Education. Available online: https://www.makeblock.com/ (accessed on 19 October 2020).

- Ismail, S.; Manweiler, J.G.; Weisz, J.D. CardKit: A Card-Based Programming Framework for Drones. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1804.08458. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/1804.08458 (accessed on 21 December 2020).

- ArduPilot Dev Team. ArduPilot Mission Planner. Available online: https://ardupilot.org/planner/ (accessed on 19 October 2020).

- SPH Engineering. UgCS. Available online: https://www.ugcs.com/ (accessed on 19 October 2020).

- Open Source Robotics Foundation. Gazebo. Available online: http://gazebosim.org (accessed on 19 October 2020).

- Meyer, J.; Sendobry, A.; Kohlbrecher, S.; Klingauf, U.; Von Stryk, O. Comprehensive Simulation of Quadrotor UAVs Using ROS and Gazebo. In Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer Science and Business Media LLC: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; Volume 7628 LNAI, pp. 400–411. [Google Scholar]

- Vanegas, F.; Gaston, K.J.; Roberts, J.; Gonzalez, F. A Framework for UAV Navigation and Exploration in GPS-Denied Environments. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Aerospace Conference, Big Sky, MT, USA, 2–9 March 2019; 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Open Source Robotics Foundation. Robot Operating System (ROS). Available online: https://www.ros.org/ (accessed on 19 October 2020).

- Sanchez-Lopez, J.L.; Fernandez, R.A.S.; Bavle, H.; Sampedro, C.; Molina, M.; Pestana, J.; Campoy, P. AEROSTACK: An architecture and open-source software framework for aerial robotics. In Proceedings of the 2016 International Conference on Unmanned Aircraft Systems (ICUAS), Arlington, VA, USA, 7–10 June 2016; pp. 332–341. [Google Scholar]

- Penserini, L.; Tonucci, E.; Ippoliti, G.; Di Labbio, J. Development framework for DRONEs as smart autonomous systems. In Proceedings of the 2017 8th International Conference on Information, Intelligence, Systems & Applications (IISA), Larnaca, Cyprus, 27–30 August 2017; Volume 2018-Janua, pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- School of Computer Science and Engineering (University of Castilla-La Mancha). Available online: https://esiiab.uclm.es. (accessed on 19 October 2020).

- Drone Challenge. Available online: http://blog.uclm.es/esiidronechallenge (accessed on 19 October 2020).

- Bermúdez, A.; Casado, R.; Fernández, G.; Guijarro, M.; Olivas, P. Drone challenge: A platform for promoting programming and robotics skills in K-12 education. Int. J. Adv. Robot. Syst. 2019, 16, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogata, K. Modern Control Engineering, 5th ed.; Pearson Education: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Moffatt, A.; Platt, E.; Mondragon, B.; Kwok, A.; Uryeu, D.; Bhandari, S. Obstacle Detection and Avoidance System for Small UAVs using a LiDAR. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Unmanned Aircraft Systems (ICUAS), Athens, Greece, 1–4 September 2020; pp. 633–640. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).