Abstract

The power of the Internet as a communicative and promotional tool in the contemporary world of tourism is unquestionable. Nevertheless, the context of online information availability referring to geotourism and georesources is very rarely addressed in the academic literature. This article undertakes research into the online information availability on georesources presented on the official websites of the National Tourism Organizations (NTOs) of three selected Central European countries with similar geotourism conditions, namely the Czech Republic, Poland, and Slovakia. Their NTOs underwent a descriptive content analysis in order to highlight the dominating trends in the online presentation of georesources. As concluded in the article, information on geotourism resources available online is rather dispersed, as it is usually presented under divergent umbrella terms. Therefore, measures need to be taken to present a holistic online picture of geoheritage on an international level of availability, where certain pieces of geotourism-related information correspond with each other, accurately applying the system of hyperlinks. The research outcomes and suggestions for the future may find applicable use for various stakeholders of the tourism industry, especially the authorities responsible for different levels of its promotion.

1. Introduction

1.1. The Power of the Internet in the 21st Century World of Tourism

One of the predominant tasks of National Tourism Organizations (NTOs) is the promotion of tourism in certain regions. This promotional activity applies diverse tools and techniques with participation in tourism fairs, media advertising, PR, promotional materials in the form of printed leaflets and catalogues, study tours for journalists, and bloggers’ involvement, to name just a few. Their prevailing purpose is evoking the interest of both international and national tourist groups, influencing the tourists’ decision-making process regarding the final choice of a particular tourism destination and the undertaken forms of tourism activities, through providing a vast array of choices in accommodation and amenities [1]. Nowadays, printed advertising materials are becoming obsolete [2]. It is the Internet that has gradually become the number one player in the tourism advertising industry since the last decade of the previous century.

Not only has the Internet revolutionized the transfer of tourist information, but it has also triggered a change in tourists’ behavior in recent years. A sharp hike in the frequency of using the Internet while planning a journey and making the final decision shows us how much human beings—and thus travelers—have become dependent on modern technology [3,4]. The current situation is the product of many variables, most importantly the Internet’s global availability, combined with real-time information updates, as well as the possibility of direct contact with the clients: a reality that has never been known before [5,6,7].

Nowadays, on the tourism market, as competitive as it is, launching a website cannot be perceived merely as a possibility, but rather as an absolute necessity that needs to be acknowledged by DMOs (Destination Management Organizations) [8,9]. Making use of this distribution channel of information is usually the first step in the modern reality of tourism to promote and commercialize a certain fragment of the tourist space [10]. What is more, due to the Internet, the tourism industry has become a global phenomenon that is available at a reasonable price. The regions promoting their tourist potential online enhance their global market position [11]. On the other hand, it needs to be stated that merely the online presence does not guarantee success [12]. A constant increase in the overall number of tourism-oriented websites causes an increased difficulty in attracting potential tourists, and finally, visiting consumers [13].

1.2. Online Information and Regional Promotion—How to Do It Right?

1.2.1. The Past and the Present—the Spectrum of Change

In the past, a choice of a particular tourism region by a potential tourist was either based on the offer of travel agencies or word of mouth. In the digital era of the 21st century, the Internet is, by far, the most popular source of information. This cyberspace guarantees tourists the ability to make their own individualized choices depending on the tourist information that was made available for them. Information communication technologies have revolutionized the tourism industry since the 1980s [4,14,15]. The websites containing the necessary information for tourists are becoming an indispensable distribution channel of tourist information in general [16,17], and they are the channel that essentially is of the greatest significance these days [18,19]. It has not changed for years now that a destination’s website is practically the first information source that tourists consult to find more specific tourist information on the place they wish to visit. In many cases, it is a real game-changer. Based on the exact information found, its availability, and how it is presented online, tourists make their final decisions on the choice of the regions in which they want to spend their vacation time. In the era of such a dynamic development of the information transfer, such as the one enabled by the Internet and social media, communication between a certain region and the institutions responsible for its promotion (NTOs and DMOs) seems to be the key issue. Therefore, it is worth focusing on how the promotion of a region and its resources is carried out online.

The success of a region in terms of its tourism popularity is usually a derivative of an adequately created and user-friendly website. It was as early as at the beginning of the 21st century when Baggio proposed a set of conditions that induce this success. He referred to it as the “Decalogue” [20] (p. 3). The researcher pointed out three basic issues, namely: the necessity of outlining a clear strategy, the aims, and the recipient groups that the offer is aimed at. The elements that enable interaction between the user and the above-mentioned organization should be well-functioning and designed in a user-friendly manner. The website’s content should be presented in a way that ensures high levels of acquisition and accuracy, starting from the colors applied, through the font size, to finish off with the correct grammar and text style. The content information provided ought to be credible and essential to encourage repeat online visits. It is best if the website’s layout is easy to navigate for all the possible recipient groups. To ensure a high level of content credibility, it should be regularly updated and corrected if needed. It is also necessary to advertise the website widely through both traditional media channels and the Internet.

1.2.2. Advantages and Disadvantages of the Website Information for the Tourism Market

The website’s quality is of pivotal importance in brand creation, as indicated by many researchers [21,22,23]. It is crucial to emphasize that merely the website’s existence raises the region’s attractiveness and influences its competitiveness on the tourism market [20] (p. 12). Quite often, potential tourists have only a vague idea of the destination they are planning to visit. Hence, online information that is provided easily and interestingly is of unquestionable importance, since it usually has an impact on the final travel destination choice [15,16,24,25].

Undeniably, a website is a key promotional tool [8,26]. In the contemporary world, tourists go online searching for all kinds of information, from practical information, such as the prices, through to the accommodation offer, transport possibilities, entertainment offerings, and regional attractions [27], and the Internet usually is the only source of information acquired [28]. Both DMO-managed and private websites are amongst most frequently visited ones by tourists prior to undertaking their journey [8,29], and their positive impact on the decision-making process is a fact [30,31,32]. It is also unquestionable how much the Internet has changed the tourism world [33,34,35]. Tourism belongs to the industry branches that refer to the Internet tools most willingly, with the websites being the most popular information sources, and therefore the most popular promotional tools of tourism regions in general [36,37]. The website’s content is as essential as its level of interactivity. Both of these elements increase the attractiveness of the tourism destination for the potential client [38,39]. Thus, a well thought out and adequate website proposal ought to become one of the basic elements of the promotional development strategy in the region [40,41]. From the recipient’s perspective, the functionality of the website is not only limited to its content value [42,43], but it is also created by other facilitating tools, such as the navigation system that constitutes the core of its usability [44,45,46].

The advantages of the online presentation of tourism-related information far outbalance its drawbacks. However, it is noteworthy that there is a risk for the web users that stems from the fact that easily accessible and visually appealing online information more and more frequently replaces the real-life experience. This trend also refers to geotourism resources. On the other hand, regardless of how attractive a certain tourism resource is in reality, if it does not exist in the virtual world, the chance of its occurrence in the tourists’ awareness decreases to almost none. This shows how far the dependence on the online information amongst tourists has grown these days.

1.3. Georesources and the Role of Online Presentation

Finally, a question arises: what is the place of geotourism and its resources in the context of online presentation and regional promotion? This form of tourism, even though it is based on the natural values of the landscape that were considered to be important elements of the tourism space for years, received closer attention as a separate form of tourism only in the last decade of the previous century. As highlighted by Hose—one of the pioneer researchers who defined the phenomenon in question—the geological aspect in the concept of geotourism deserves the utmost attention [47,48]. Another issue of great importance is the proper interpretation of the elements of the inanimate nature aided by the tourist facilities, owing to which the tourist gains an insight into the knowledge in geology and geomorphology of the visited place [49,50]. What is more, this knowledge considerably exceeds the basic level of information needed to admire the aesthetics of the observed fragment of the natural space [51]. Newsome and Dowling [52] indicate the importance of taking a sustainable approach to the visited resources. On the one hand, geotourism facilitates need to appreciate their role in the landscape and the evolutional history of the Earth. On the other hand, a sustainable approach protects the geotourism resources by raising the awareness of the tourists, who are interested in getting to know the geology of the place in more detail, when it comes to the necessity of their preservation, to ensure the continuity of the geoheritage for the future generations. The obligation of preserving the heritage of an inanimate nature was also articulated by Hose and Vasiljević [53]. It originated in the idea that is commonly referred to in the academic literature as geoconservation. Its predominant task is the need to protect the geodiversity that, according to Grey [54], can be understood as a set of geological elements amongst which the greatest focus is placed on rocks, minerals, and fossils, as well as on the geomorphological elements such as landforms and physical processes, to finish off with the elements of soil. All of the above is referred to as geoheritage [48,55]. Most of the recent studies in this subject area emphasize the dualistic character of the phenomenon of geotourism [56]. Namely, the in situ geosites are the predominant points of tourist interest; nevertheless, what is growing in popularity are the ex situ elements of geoheritage presented to the wide audience in the form of museum exhibitions. The latter form of presentation of an inanimate nature is characteristic of the urban areas in particular.

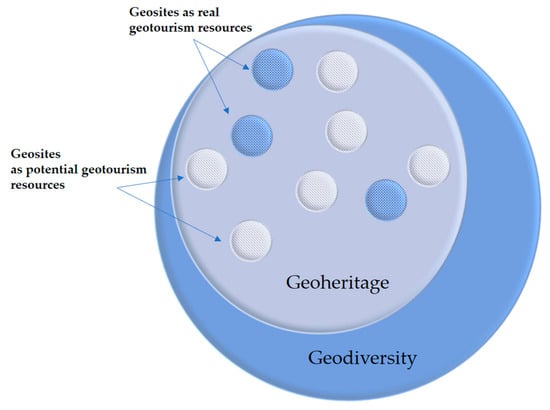

So as to avoid any ambiguity in understanding of the basic concepts used in this research paper, its authors have presented them in a visual form (Figure 1) and proposed the following definitions. The notion of geodiversity entails all the possible elements related to the inanimate nature, regardless of their scale. Hence, geodiversity comprises both single sites, such as individual rocks and minerals, as well as surface elements, i.e., mountain ranges, uplands, etc. Within the concept of geodiversity, one can differentiate the elements that are valuable witnesses of the natural processes, which are unique in character, or for other reasons that are cognitively important. These elements of an inanimate nature can be defined as geoheritage. Geosites, on the other hand, are the integral components of geoheritage that due to their smaller scale can be perceived holistically by the public. Most geosites can be classified as potential resources for geotourism, whereas only the ones of the greatest scientific value that, at the same time, are adequately prepared to the needs of the tourist traffic (in the form of the existing infrastructure) can be referred to as the real or actual geotourism resources that constitute the basis for creating the geotourism products.

Figure 1.

Interrelations between the basic ‘geo-concepts’. Source: Authors’ own elaboration.

This specific set of tourism resources requires adequate presentation and promotion to ensure the development of geotourism in regions that abound in the resources of an inanimate nature. These processes are happening on different levels—local, regional, national, and international—and require divergent tools. The most popular and the most effective at the same time is the Internet. Therefore, it is worth analyzing how the plethora of the Central European geoheritage resources is perceived by the National Tourism Organizations of chosen countries and how they promote it, so as to ensure becoming an essential factor in generating the geotourism movement in this part of Europe, which only three decades ago came back on the map of the Old Continent’s tourism landscape.

2. Materials and Methods

The predominant research aim in this paper was determining the level of accessibility of online information on geoheritage and geotourism on the websites of the NTOs of selected Central European Countries. The choice of the countries applied in the research was made in accordance with the regional division by the International Geographical Union. Additionally, only the countries whose National Tourism Organizations are operating under the auspices of the European Travel Commission, a nonprofit organization responsible for promoting Europe as a tourism destination, were taken into consideration. Altogether, three neighboring countries with similar geoconditions, and hence comparative geotourism resources potential, were chosen to be analyzed: namely Poland, the Czech Republic, and Slovakia (It is worth accentuating the fact that all three countries in question entered the system and market changes at a relatively similar time, and therefore faced comparative challenges. It is the Internet that offers them a chance to fully enter the global market, and to create a truly competitive tourist offer). Their NTOs underwent descriptive content analysis as the qualitative method used to conduct the research. The categories under assessment comprised the following:

- Placement consistency of georesources under the main bookmarks;

- Scope of information available in English, as opposed to the original language of the NTO;

- Embedded search engines’ results for the selected search terms, i.e., geotourism, geosite, geopark, geoheritage, geology, landscape, nature.

- Presence and validity of hyperlinks directing the reader to further information on geoheritage;

- Mobile website version and mobile applications’ availability;

- Information accuracy and cohesion;

- Language accuracy.

Furthermore, the international perspective included in the article’s title was achieved through focusing on the English versions of the NTO’s websites, which was based on the assumption that “English is an international language in a global sense” [57]. The online research was carried out between 15 October and 17 November 2019, applying the Google Chrome web search engine.

3. Results

As previously stated, the websites of three NTOs, namely the Polish Tourism Organization, the Czech Tourism Authority, later in the text referred to as Czech Tourism, and the Slovak Tourist Board, underwent the content analysis focused on the geotourism theme. Table 1, Table 2 and Table 3 show the online research outcomes divided into five main categories under comparison, i.e.,:

Table 1.

Geotourism content analysis of the Polish NTO’s website.

Table 2.

Geotourism content analysis of the Czech NTO’s website.

Table 3.

Geotourism content analysis of the Slovak NTO’s website.

- Homepage bookmarks (English version), where the general content is set aside the geotourism-related content;

- Homepage bookmarks and geotourist information in the NTOs’ original language version (mutual relations);

- Embedded search engine responses to the selected geotourism keywords;

- Availability of the mobile version of the website and mobile applications in English;

- Language accuracy.

4. Discussion

All three NTOs analyzed provide the readers with information under seven main bookmarks maximum. What is fully understandable is that the organization of content on each website is a part of its overall design and an idea behind it. It is common knowledge that regardless of personal interests and the exact information that visitors want to obtain, the websites should be as easy to navigate as possible. It is also crucial for them to be intuitive and enable the readers to find whatever they are looking for as quickly as possible. Hence, the smaller the number of clicks and the clearer the names of the categories used on the website, the more universally understandable they are in the tourism industry, which is preferable.

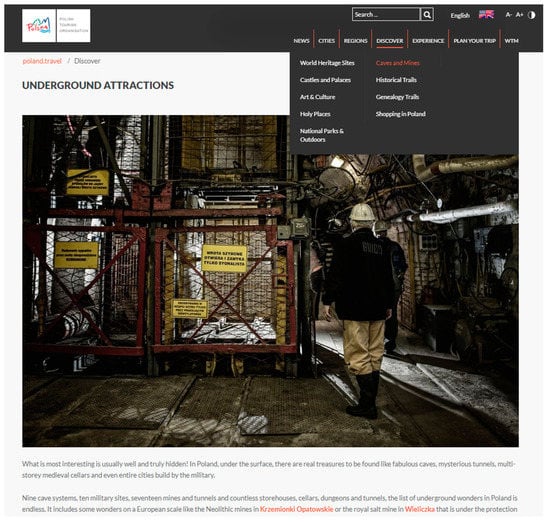

Only two steps need to be taken in order to find the geotourist information in the case of the Polish Tourism Organization, where one of the main bookmarks—Discover—leads the reader to the article named Caves and Mines: Underground Attractions (Figure 2). However, it has to be stated that the above-mentioned are only two examples of attractions within the interest of geotourists.

Figure 2.

Underground attractions of Poland (a two-step access path: Discover–Caves and Mines). Source: [108].

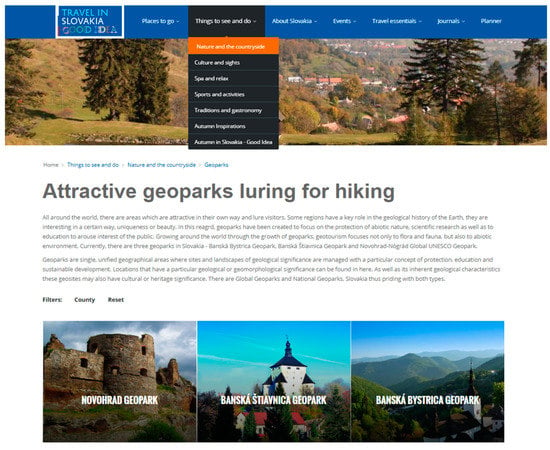

The access path of three steps was required by the Slovak Tourist Board to find a separate article on Geoparks, which was most appropriate from the perspective of geoheritage protection and the geotourist offer (Figure 3). At the same time, it was not singled out as an individual subcategory on the websites of the Polish and Czech NTOs, which is not understandable, as all three countries can pride themselves on having geoparks belonging to the Global Geoparks Network, not to mention the ones of the national and local rank.

Figure 3.

Geoparks (a three-step access path: Things to See and Do–Nature and the Countryside–Geoparks). Source: [94].

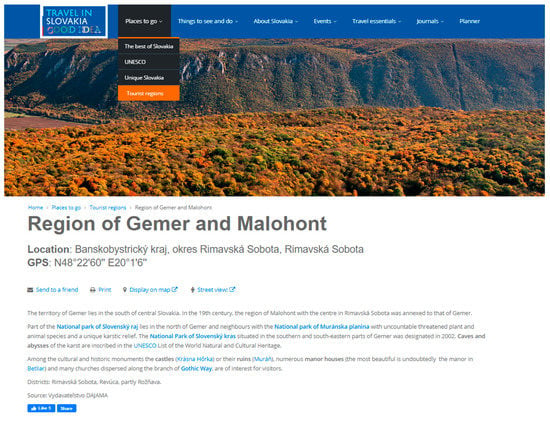

Most frequently, as many as three to four steps and more were to be taken in order to find more specific geotourist information, as indicated in Table 1, Table 2 and Table 3. For instance, in all three cases, information on geoheritage is provided in relation to the regional division of the country. Regions and their tourist offer are either distinguished as the main bookmarks, as on the website of the Polish Tourism Organization, or Czech Tourism, where they are referred to as Regions and Destinations respectively, or as on the website of the Slovak Tourist Board, which they are found within the subcategory of the bookmark titled Places to Go. Geotourist information available via this access path requires initial knowledge on the topic. Therefore, considering the overall number of clicks and introductory articles to go through, it is much more likely to be used by a person who is already familiar with the areas in question (Figure 4), making it much less likely for potential inanimate nature-interested travelers to do so. Moreover, taking into consideration the natural values of the landscape, the biotic aspects of it seem to overtake the general scope of attention.

Figure 4.

National Park of Slovenský raj (a four-step access path: Places to Go–Tourist Regions–Region of Gemer and Malohont–National Park of Slovenský Raj). Source: [109].

Another example of similar categories under which more information in question can be found for all three countries are the national parks. Similarly to the regional division of the countries, it requires the reader either to possess initial knowledge on the topic to find the necessary information relatively quickly or to spend some quality time reading through the introductory articles to learn about the georesources that they hold (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

A four-step access path: Things to See and Do–Nature and the Countryside–National Parks–National Park of High Tatras). Source: [110].

Additionally, and quite surprisingly, even though all three countries advertise their cultural and natural resources under the auspices of UNESCO, none of them even mentions in the main article that certain geoparks within their area belong to the Global Geoparks Network, and hence can be referred to as UNESCO Global Geoparks. According to the Global Geoparks Network [111], “UNESCO Global Geoparks are single, unified geographical areas where sites and landscapes of international geological significance are managed with a holistic concept of protection, education and sustainable development”. As it is a relatively new initiative that originated in 2015, the website’s content and the way in which information appears on the page should be updated and follow the newest trends and guidelines for the tourism industry and nature protection. Czech Tourism uses the name “Bohemian Paradise–UNESCO Geopark”, but as stated before, not in the main article devoted to the UNESCO sites of the country, and this piece of information is available after knowing the following access path Activities–Active Holiday–Natural Heritage–Protected Areas–Bohemian Paradise UNESCO Geopark (Figure 6). In addition, in the case of Poland, even though the Muskauer Park (Park Mużakowski) in Łęknica, as one of the greatest examples of the 19th century gardening architecture in Europe, is advertised under the access path of Discover–World Heritage Sites–Muskauer Park, no information whatsoever, even in the form of a hyperlink, is given on the fact that it lies within the Muskauer Arch Geopark area, which is the only Polish geopark that is on the list of the Global Geoparks Network under the UNESCO auspices. The Slovak Tourist Board seems to have made the information on the Novograd-Nógrád UNESCO Global Geopark most easily accessible via Things to See and Do–Nature and Countryside–Geoparks—Novohrad Geopark. It is understandable that the main article on the UNESCO-listed heritage of each country predominantly focuses on the most recognizable lists. Notwithstanding, since selected geoparks function under the same patronage, it is worth at least mentioning this fact or providing a proper hyperlink.

Figure 6.

Bohemian Paradise–UNESCO Geopark (a five-step access path: Activities–Active Holiday–Natural Heritage–Protected Areas–Bohemian Paradise). Source: [112].

The hyperlinks system of each NTO leading the reader to more detailed geotourism-related information also needs improvement. For instance, in the case of the Polish Tourism Organization’s website, when the reader is willing to enter the tourism portal of the West Pomeranian Voivodeship, s/he is directed to the website of the West Pomeranian Marshall’s Office with no English language version. Additionally, even though the hyperlinks to the official websites of the Polish national parks are provided, generally speaking, the information that can be found there is usually far from ideal, mainly due to the English language version’s unavailability and/or issues in translation. A similar problem appears when reaching the official national parks’ websites of the Czech Republic. In contrast, the Slovak Tourist Board does not provide the reader with the hyperlinks to the country’s national parks at all. However, it does so for its geoparks. Nevertheless, even though the Network of Geoparks of the Slovak Republic, providing comprehensive information on the subject matter, is mentioned under the main article devoted to the Novohrad Geopark, no hyperlink is included.

While comparing the geotourism-related content of the websites and the responses of the embedded search engines to the selected search terms (i.e., geotourism, geosite, geopark, geoheritage, geology, landscape, nature), it seems that most of them do not serve their function successfully. ‘Geotourism’, ‘geosite’, and ‘geoheritage’ were not used within the website’s content at all; even though there is every reason behind linking them with the phenomenon in question, no results were shown. The most serious problem though seems to be giving preference to information of lesser importance from the point of view of the tourist attractions’ rank. For instance, after having typed the word ‘geopark’, the Polish Tourism Organization’s embedded search engine provides information on the Geopark Kielce only, but completely ignores the Muskauer Arch Geopark, which is one of the UNESCO Global Geoparks. Information on the remaining geoparks of the national rank in Poland is also excluded from the website’s content. Yet another example from the Polish NTO is that some search words such as ‘geology’ are not thematically linked with the right articles. To exemplify, using the embedded search engine in order to find information on the above-mentioned Geopark Kielce that abounds in geosites, one will not succeed in doing so. Therefore, the reader does not stand a chance of finding comprehensive information on the Polish attractions within their scope of interest so as to make an informed traveling decision. Meanwhile, examples from Czech Tourism show that the aforementioned phenomenon can also be reversed, and the searching process might result in finding information on the places that are only remotely related to the search terms under discussion. Moreover, the overall number of embedded search engine responses to the words ‘nature’ and ‘landscape’ makes it hard for the reader to find geotourism-specific information. A clear preference in most articles is given to the biotic aspects of both nature and landscape, whereas the abiotic ones are either eliminated or diminished. Conducting a similar comparison for the Slovak NTO’s website was mostly impossible due to the fact that the website’s embedded search engine is linked with the general Google search engine.

Providing limited information in the English version of the NTOs’ websites in comparison to their versions written in the mother tongue is understandable, as long as such a limitation is connected with the rank of attractions to being covered. Neglecting information on tourist attractions that are already internationally recognizable, or that stand a chance of becoming ones in the near future, is unjustified and should not take place.

Even though it has become standard to make the mobile versions of the NTOs’ websites available for their users, making theme or interest-oriented mobile applications, especially with the geo-prefix in their name, is still a niche to be covered. ‘Nature’ and ‘landscape’ seem to be too vast in their character and understanding to serve this function properly from the perspective of geotourists.

With reference to the language accuracy, all the geotourism-related content on the websites of the NTOs under analysis represents native or a native-like level of language proficiency in translation. The most common mistakes are typos or inconsistencies in the translation of the proper names, as indicated in detail in Table 1, Table 2 and Table 3. Nonetheless, they do not influence the overall level of understanding of the text for the English-speaking recipients.

5. Conclusions

The descriptive content analysis of the selected NTOs’ websites enabled the authors to draw the following inferences and improvement suggestions:

- Information on georesources provided by the NTOs of selected European countries is dispersed and usually of fragmentary character; as long as the generalization of facts is fully understandable and inevitable on national portals, excluding information on the existence of geotourism attractions of an international rank in particular should not take place, especially when they constitute good examples of attractions that stand a chance in raising the tourists’ level of awareness on the concepts of geoprotection and sustainability;

- Geotourism-related information falls under divergent umbrella terms, and therefore, it usually requires much effort from the readers to come across the content of their interest; it could be improved at least by implementing the key word ‘geotourism’ or one of its derivatives (e.g., ‘geosite’) to the NTOs’ online travel planners;

- Both animate and inanimate landscape values co-create the inextricably linked tourism space; therefore, it seems unjustified to prioritize one for the sake of the other and focus promotional actions mainly on the animate landscape tourism resources;

- As it is impossible to draw a clear-cut line between various types of tourism activities relying upon the same resources, online information availability should be ensured by an appropriately working system of search terms that are prepared in cooperation with tourism experts who are aware of their mutual relations, which could in the end result in a more effective use of the websites’ content;

- Even though there is every reason for distinguishing ‘geoparks’ as a separate bookmark on the websites of NTOs, or at least a subcategory of nature-related attractions, it is not a common practice;

- Access to further geoheritage information provided via hyperlinks on the websites of the NTOs analyzed is possible only in some cases; usually, it is just a theory due to the issues in translation and/or the information provided is incomplete, out of date, or the reader is led to a different website than the hyperlinks’ names suggest. It is most common in reference to the official websites of the national parks; therefore, there seems to be too much lost opportunity and the current situation calls for a change;

- Making the brochures available as downloadable PDF files focused on the concept of geotourism could be one of the possible solutions for presenting each country’s geoheritage potential in a holistic way;

- Presenting the geotourist offer including the spatial distribution of georesources could also be made available via mobile applications as they are ever gaining in popularity, especially among the younger generations of visitors; moreover, information provided this way does not have a direct physical interference whatsoever with the landscape, and therefore helps to maintain it as untouched by the tourism traffic and its needs as possible;

- Including information on the availability of geoparks under the UNESCO auspices, at least in a form of a hyperlink, or an active picture directing the reader to further information on UNESCO Global Geoparks is a good promotional opportunity;

- NTOs present the country’s tourist offer in a holistic way, which is in agreement with the general idea for presenting certain content and the overall website design. Nevertheless, there is a need for a think tank enabling expert consultations, especially between the marketing and promotion sector representatives and experts in the tourism industry that would lead to such online presentation of information that, on one hand, would maximize the use of the countries’ tourist offer potential in accordance with the rules of sustainable development, and on the other hand, would not neglect or diminish the role of the abiotic aspects of the environment;

- Promoting geotourism on a national level via NTO’s websites with its scientifically and cognitively valuable resources alongside other, well-consolidated forms of tourist activities can be conducive to gaining knowledge on and appreciating the geological component in both natural and urban recipient areas.

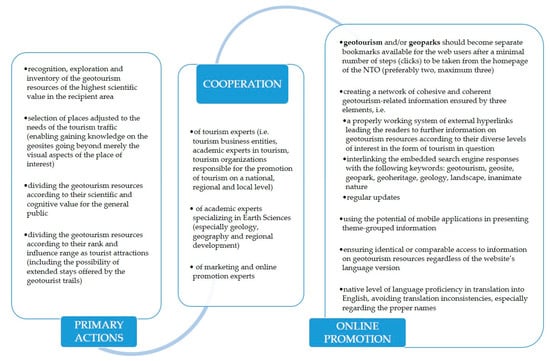

To summarize, the actions conducive to the accurate presentation of geotourism resources on the NTOs’ websites, as presented in Figure 7, are threefold. All three levels, namely the primary actions focused on the geotourism resources per se, followed by undertaking the cooperation of the experts in three realms of knowledge, and finally, the actions concentrated on the e-aspect of their promotion are of equal importance. It is worth emphasizing that as far as the very first step of actions to be taken is concerned, the scientific value of geosites is of utmost importance. The procedure of their recognition, exploration, and taking an inventory of the sites can vary in different countries. Nevertheless, the elements that the above-mentioned procedure usually have in common are being drawn by teams of academics, most frequently specializing in geology, and financed among others from the ministerial funds. To exemplify, in Poland, the binding documents drawn in this respect in 2006 and 2012 respectively were:

Figure 7.

Flowchart of actions conducive to the accurate presentation of geotourism resources on the NTOs’ websites. Source: Authors’ own elaboration.

- The Catalogue of Geotourist Sites in Poland (written under the scientific supervision of Słomka, Doktor, Joniec, and Kicińska-Świderska, and published by the AGH University of Science and Technology in Cracow) [113];

- The Catalogue of Geotourist Sites in Nature Reserves and Monuments (written under the scientific supervision of professor Słomka from the AGH University of Science and Technology, Department of General Geology, and Geotourism in Cracow) [114].

All three countries whose NTOs’ websites underwent analysis possess considerable geotourism potential. Therefore, the main research aim was to check how the potential of georesources is presented online amongst the other tourism resources of each country. The Internet is a tool enabling an instant reaction; hence, this instant reaction can be expected in presenting the newest tourism trends. In other words, the Internet, as quick of a tool as it is, should be equally quick in the hands of the decision makers responsible for the final shape of the regional promotion in tourism. Even more so, taking into consideration that geotourism as a separate category has been growing in popularity since the 1990s, it goes hand in hand with the concept of geoconservation and sustainable development.

The main limitation behind the study, and at the same time a further research perspective refers to the overall number of NTOs’ websites that underwent the descriptive content analysis. This paper is the first step in the trial to create a model of a proper online presentation of geotourism resources. At this point in this research, it is unfeasible to clearly state the level of representativeness for other European countries, as no comparative data is available in the academic literature. Notwithstanding, the similarities and differences in the online presentation of georesources shown in the sections of results and conclusions can surely be referred to other Central European countries that underwent the same system changes, and therefore had comparable development and economic growth obstacles to overcome. Similarly, even though well-defined examples of the online presentation of single georesources can be found on the websites of all the analyzed countries (of the Czech Republic in particular), the current picture of the online presentation focusing on the georesources of the remaining European countries, according to their regional division, is yet to be drawn to perceive a holistic ‘geotourism online map’ of Europe as a tourism destination. Secondly, as the research outcomes have shown, the hyperlinks system within the described websites is far from ideal, and the seemingly more in-depth information provided by them should also become the subject of further analyses. Thirdly, even though the importance of the NTOs from the perspective of tourism marketing cannot be denied, the broadly understood Internet offers much more than the website information; therefore, especially the aspect of using social media as a promotional tool for geotourism is the research area that should attract more attention in the academic literature.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.R.; methodology, A.R., K.W. and Z.J.; formal analysis, A.R., K.W. and Z.J.; resources, K.W. and A.R., writing—original draft preparation, A.R., K.W.; writing—review and editing, A.R., K.W. and Z.J.; visualization, A.R., K.W.; supervision, K.W.; Z.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express gratitude to the NTOs’ authorities for providing consent to use the visual material available on the official websites for the purpose of drawing this article, as well as for being open to cooperation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Noti, E. The websites of National Tourism Organisations: A challenge of E-marketing. Angl. J. 2013, 2, 241–249. [Google Scholar]

- Vyas, C. Evaluating state tourism websites using Search Engine Optimization tools. Tour. Manag. 2019, 73, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKay, K.; Vogt, C. Information technology in everyday and vacation contexts. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 1380–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, R.; Buhalis, D.; Cobanoglu, C. Progress on information and communication technologies in hospitality and tourism. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 26, 727–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, R.; Morrison, A.M.; Ismail, J.A. East versus West: A comparison of online destination marketing in China and the USA. J. Vacat. Mark. 2004, 10, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baloglu, S.; Pekcan, Y.A. The website design and Internet site marketing practices of upscale and luxury hotels in Turkey. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.-L.; Gretzel, U.; Fesenmaier, D.R. The role of information technology use in American convention and visitors bureaus. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 326–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.; Lehto, X.Y.; Oleary, J.T. What does the consumer want from a DMO website? A study of US and Canadian tourists’ perspectives. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2007, 9, 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pai, C.-K.; Xia, M.L.; Wang, T.-W. A comparison of the official tourism website of five east tourism destinations. Inf. Technol. Tour. 2014, 14, 97–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malenkina, N.; Ivanov, S. A linguistic analysis of the official tourism websites of the seventeen Spanish Autonomous Communities. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2018, 9, 204–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariani, M.M.; Baggio, R.; Buhalis, D.; Longhi, C. Tourism Management, Marketing, and Development; Palgrave Macmillan US: New York, NY, USA, 2014; ISBN 978-1-349-47471-4. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, K.; Law, R. A modified functionality performance evaluation model for evaluating the performance of China based hotel websites. J. Acad. Bus. Econ. 2003, 2, 193–208. [Google Scholar]

- Auger, P. The Impact of Interactivity and Design Sophistication on the Performance of Commercial Websites for Small Businesses. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2005, 43, 119–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhalis, D. ETourism. Information Technology for Strategic Tourism Management; Financial Times Prentice Hall: New York, NY, USA, 2003; ISBN 0582357403. [Google Scholar]

- Buhalis, D.; Law, R. Progress in information technology and tourism management: 20 years on and 10 years after the Internet—The state of eTourism research. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 609–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastida, U.; Huan, T.C. Performance evaluation of tourism websites’ information quality of four global destination brands: Beijing, Hong Kong, Shanghai, and Taipei. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 167–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Vasto-Terrientes, L.; Fernández-Cavia, J.; Huertas, A.; Moreno, A.; Valls, A. Official tourist destination websites: Hierarchical analysis and assessment with ELECTRE-III-H. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2015, 15, 16–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Cavia, J.; Huertas-Roig, A. City Brands and their Communication through Web Sites: Identification of Problems and Proposals for Improvement. In Information Communication Technologies and City Marketing: Digital Opportunities for Cities around the World; Gascó-Hernandez, M., Torres-Coronas, T., Eds.; Information Science Reference, IGI Global: Hershey PA, USA, 2009; pp. 26–49. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, W.; Gretzel, U. Designing persuasive destination websites: A mental imagery processing perspective. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 1270–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baggio, R. A Websites Analysis of European Tourism Organizations. Anatolia 2003, 14, 93–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, J.; Baker, S.M. Customer participation in creating site brand loyalty. J. Interact. Mark. 2001, 15, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barwise, P.; Elberse, A.; Hammond, K. Marketing and the Internet: A research review. In Handbook of Marketing; Weitz, B.A., Wensley, R., Eds.; SAGE: London, UK, 2002; pp. 527–558. ISBN 978-0761956822. [Google Scholar]

- Ilfeld, J.S.; Winer, R.S. Generating Website Traffic. JAR 2002, 42, 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, J. The role of tour operators’ promotional material in the formation of destination image and consumer expectations: The case of the People’s Republic of China. J. Vacat. Mark. 1998, 4, 282–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, J.; Gu, C.; Zhen, F. Examining antecedents and consequences of tourist satisfaction: A structural modeling approach. Tinshhua Sci. Technol. 2009, 14, 397–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Jang, S. Investigating the Routes of Communication on Destination Websites. J. Travel Res. 2012, 51, 94–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyun, M.Y.; O’Keefe, R.M. Virtual destination image: Testing a telepresence model. J. Bus. Res. 2012, 65, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehto, X.Y.; Kim, D.-Y.; Morrison, A.M. The effect of prior destination experience on online information search behaviour. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2006, 6, 160–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, R.; Leung, R. A Study of Airlines’ Online Reservation Services on the Internet. J. Travel Res. 2000, 39, 202–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govers, R.; Go, F. Projected destination image online: Website content analysis of pictures and text. Inf. Technol. Tour. 2004, 7, 73–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, M. Online destination image of India: A consumer based perspective. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2009, 21, 226–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, N.; Lee, H.; Lee, S.J.; Koo, C. The influence of tourism website on tourists’ behavior to determine destination selection: A case study of creative economy in Korea. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2015, 96, 130–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, C.-I.; Lee, Y.-L. The development of an e-travel service quality scale. Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 1434–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zins, A.H. Exploring Travel Information Search Behavior beyond Common Frontiers. Inf. Technol. Tour. 2007, 9, 149–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yovcheva, Z.; Buhalis, D.; Gatzidis, C.; van Elzakker, C.P.J.M. Empirical Evaluation of Smartphone Augmented Reality Browsers in an Urban Tourism Destination Context. Int. J. Mob. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2014, 6, 10–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horng, J.-S.; Tsai, C.-T. Government websites for promoting East Asian culinary tourism: A cross-national analysis. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 74–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepchenkova, S.; Tang, L.; Jang, S.; Kirilenko, A.P.; Morrison, A.M. Benchmarking CVB website performance: Spatial and structural patterns. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 611–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano, V.; Prentice, R. Opportunities for endearment to place through electronic ‘visiting’: WWW homepages and the tourism promotion of Scotland. Tour. Manag. 1998, 19, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gretzel, U.; Yuan, Y.-L.; Fesenmaier, D.R. Preparing for the New Economy: Advertising Strategies and Change in Destination Marketing Organizations. J. Travel Res. 2000, 39, 146–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hvass, K.A.; Munar, A.M. The takeoff of social media in tourism. J. Vacat. Mark. 2012, 18, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Z.; Gretzel, U. Role of social media in online travel information search. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, T.; Law, R. Developing a performance indicator for hotel websites. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2003, 22, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, A.M.; Taylor, J.S.; Douglas, A. Website Evaluation in Tourism and Hospitality. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2004, 17, 233–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ting, P.-H.; Kuo, C.-F.; Li, C.-M. What Does Hotel Website Content Say About a Property—An Evaluation of Upscale Hotels in Taiwan and China. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2012, 29, 369–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, R.; Qi, S.; Leung, B. Perceptions of Functionality and Usability on Travel Websites: The Case of Chinese Travelers. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2008, 13, 435–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, R. Evaluation of hotel websites: Progress and future developments (invited paper for ‘luminaries’ special issue of International Journal of Hospitality Management). Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 76, 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hose, T.A. Telling the story of stone—Assessing the client base. In Geological and Landscape Conservation; O’Halloran, D., Green, C., Harley, M., Stanley, M., Knill, J., Eds.; Geological Society: London, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Hose, T.A. Geotourism—Selling the Earth to Europe. In Engineering Geology and the Environment; Marinos, P.G., Koukis, G.C., Tsiambaos, G.C., Stournaras, G.C., Eds.; AA Balkema: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 1997; pp. 2955–2960. [Google Scholar]

- Hose, T.A. European geotourism—Geological interpretation and geoconservation promotion for tourists. In Geological Heritage: Its Conservation and Management; Barretino, D., Wimbledon, W.P., Gallego, E., Eds.; Instituto Tecnologico Geominero de Espana: Madrid, Spain, 2000; pp. 127–146. [Google Scholar]

- Hose, T.A. Geotourism: Appreciating the deep time of landscapes. In Niche Tourism: Contemporary Issues, Trends and Cases; Novelli, M., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2005; pp. 27–37. [Google Scholar]

- Hose, T.A. The English Origins of Geotourism (as a Vehicle for Geoconservation) and Their Relevance to Current Studies. AGS 2011, 51, 343–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newsome, D.; Dowling, R.K. Geotourism. The Tourism of Geology and Landscape; Goodfellow: Oxford, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hose, T.A.; Vasiljević, D.A. Defining the Nature and Purpose of Modern Geotourism with Particular Reference to the United Kingdom and South-East Europe. Geoheritage 2012, 4, 25–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, M. Geodiversity and geoconservation: What, why, and how? In Papers Presented at the George Wright Forum. Santucci, V.L., Ed.; 2005, pp. 4–12. Available online: http://www.georgewright.org/223gray.pdf (accessed on 21 October 2019).

- Gray, M. Geodiversity. Valuing and Conserving Abiotic Nature; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Melelli, L. “Perugia Upside-Down”: A Multimedia Exhibition in Umbria (Central Italy) for Improving Geoheritage and Geotourism in Urban Areas. Resources 2019, 8, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuković-Vojnović, D.; Nićin, M. English as a Global Language in the Tourism Industry: A Case Study. In The English of Tourism; Rață, G., Petroman, I., Petroman, C., Eds.; Cambridge Scholars Publishing: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2012; pp. 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Polish Tourism Organization. Poland’s Highlights 2019/2020 #VisitPoland #Polandtravel. Available online: https://www.poland.travel/attachments/article/26117/Poland%20Handout%202020%20new.pdf (accessed on 21 October 2019).

- Polish Tourism Organization. New UNESCO Site in Poland. Available online: https://www.poland.travel/en/travel-inspirations/new-unesco-site-in-poland (accessed on 21 October 2019).

- Lubelskie Marshall’s Office. Available online: http://www.turystyka.lubelskie.pl/index.php/lrt/page/135/ (accessed on 16 October 2019).

- West Pomeranian Marshall’s Office. Available online: http://wzp.pl/ (accessed on 18 October 2019).

- Świętokrzyskie Voivodeship Office. Available online: https://www.kielce.uw.gov.pl/en/swietokrzyskie-province/3,Swietokrzyskie-Province.html (accessed on 18 October 2019).

- Visit Silesia. Available online: http://www.visitsilesia.eu/ (accessed on 15 October 2019).

- Polish Tourism Organization. Śląskie—Industrial Adventure. Available online: https://www.poland.travel/en/regions/slaskie-voivodship-industrial-adventure (accessed on 22 October 2019).

- Polish Tourism Organization. Hiking in Poland—Sudety. Available online: https://www.poland.travel/en/experience/hiking/hiking-in-poland-guide-%E2%80%93-sudety (accessed on 22 October 2019).

- Erfurt-Cooper, P. The Importance of Natural Geothermal Resources in Tourism. In Proceedings of the World Geothermal Congress 2010, Bali, Indonesia, 25–29 April 2010; Available online: https://www.geothermal-energy.org/pdf/IGAstandard/WGC/2010/3318.pdf (accessed on 15 October 2019).

- Polish Tourism Organization. Termy w Polsce Sposobem na Jesienną Chandrę. Available online: https://www.polska.travel/pl/zobacz-koniecznie/pomysl-na/termy-w-polsce-sposobem-na-jesienna-chandre (accessed on 22 October 2019).

- Polish Tourism Organization. Poland: Major Tourist Attractions. Available online: https://pdf.polska.travel/docs/en/hit/Hity_en.pdf?_ga=2.177685733.176097391.1573110931-1079215847.1557493001 (accessed on 23 October 2019).

- Polish Tourism Organization. Muskauer Park: Fulfilled Vission of Paradise. Available online: https://www.poland.travel/attachments/article/6505/UNESCO_EN.pdf (accessed on 23 October 2019).

- Polish Tourism Organization. Geoparki. Available online: https://www.polska.travel/pl/poznaj-atrakcje-i-zabytki/zabytki-i-inne-atrakcje/geoparki-2 (accessed on 21 October 2019).

- Global Geoparks Network. Muskau Arch Geopark—GERMANY/POLAND. Available online: http://www.europeangeoparks.org/?page_id=656 (accessed on 20 October 2019).

- Ministry of the Environment. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/web/srodowisko (accessed on 21 October 2019).

- Polish Geological Institute. Geotourism. Available online: https://www.pgi.gov.pl/geoturystyka-606.html (accessed on 21 October 2019).

- Polish Geological Institute. Geoturystyka. Available online: https://www.pgi.gov.pl/oferta-inst/geoturystyka.html (accessed on 21 October 2019).

- Polish Tourism Organization. Geopark in Kielce. Available online: https://www.poland.travel/en/heritage/archeological-sites/geopark-in-kielce (accessed on 24 October 2019).

- Geopark Kielce. Historia Geoparku Kielce. Available online: http://geopark-kielce.pl/o-nas/historia-geoparku-kielce/ (accessed on 20 October 2019).

- Polish Tourism Organization. Embedded Search Engine Results for the Word ‘Geology’. Available online: https://www.poland.travel/en/finder?ordering=newest&searchword=geology (accessed on 24 October 2019).

- Polish Tourism Organization. Plan Your Trip. Available online: https://travelplanner.poland.travel/planner/selectAttractions?poisPerPage=19 (accessed on 24 October 2019).

- Czech Tourism. Bohemian Switzerland. Available online: https://www.czechtourism.com/c/bohemian-switzerland-national-park/ (accessed on 25 October 2019).

- Czech Tourism. Bohemian Paradise. Available online: https://www.czechtourism.com/s/bohemian-paradise-walk/ (accessed on 27 October 2019).

- Czech Tourism. Bohemian Paradise along the Greenway Jizera. Available online: https://www.czechtourism.com/s/bohemian-paradise-greenway-jizera-cycling/ (accessed on 27 October 2019).

- Czech Tourism. Bohemian Switzerland. Available online: https://www.czechtourism.com/s/hrensko-soutesky-walk/ (accessed on 28 October 2019).

- Czech Tourism. Natural Heritage. Available online: https://www.czechtourism.com/a/natural-heritage/ (accessed on 24 October 2019).

- Czech Tourism. Rock towns. Available online: https://www.czechtourism.com/a/rock-towns/ (accessed on 25 October 2019).

- Czech Tourism. UNESCO Global Geopark. Available online: http://pdf.czechtourism.com/unesco_en/ (accessed on 24 October 2019).

- Czech Tourism. The Adventurous Heart of Bohemia. Available online: https://www.czechtourism.com/tourists/stories/cesky-raj/ (accessed on 25 October 2019).

- Czech Tourism. Návrh geoturistického produktu Geoparku Vysočina. Available online: https://www.czechtourism.cz/getattachment/Pro-media/Tiskove-zpravy/TOP-prace-studentu-Service-design-i-geoturismus/Navrh-geoturistickeho-produktu-Geoparku-Vysocina.pdf.aspx?ext=.pdf (accessed on 30 October 2019).

- Czech Tourism. Search Results: Geopark. Available online: https://www.czechtourism.com/tourists/search/?searchtext=geopark&searchmode=anyword (accessed on 25 October 2019).

- Czech Tourism. Search Results for the Search Term “Geology”. Available online: https://www.czechtourism.com/tourists/search/?searchtext=geology&searchmode=anyword (accessed on 30 October 2019).

- Czech Tourism. Brdy Mountains. Available online: https://www.czechtourism.com/c/brdy-mountains/ (accessed on 25 October 2019).

- Czech Tourism. Pravčická brána: Get to know a European Great: The Pravčická Brána. Available online: https://www.czechtourism.com/c/pravcicka-brana/ (accessed on 31 October 2019).

- Slovakia Travel. Tatras and Northern Spiš. Available online: http://slovakia.travel/en/places-to-go/the-best-of-slovakia/tatras (accessed on 26 October 2019).

- Slovakia Travel. You Will Find (Only) in Slovakia. Available online: http://slovakia.travel/en/places-to-go/unique-slovakia#prettyPhoto (accessed on 25 October 2019).

- Slovakia Travel. Geoparks: Attractive Geoparks Luring for Hiking. Available online: http://slovakia.travel/en/things-to-see-and-do/nature-and-the-countryside/geoparks (accessed on 25 October 2019).

- Slovakia Travel. Novohrad Geopark. Available online: http://slovakia.travel/en/novohrad-geopark (accessed on 25 October 2019).

- Bansko Bystricky Geopark. SLOVAKIA—LAG Banská Bystrica Geopark. Available online: http://www.geoparkbb.sk/en (accessed on 26 October 2019).

- Slovakia Travel. Subterranean Treasures. Available online: http://slovakia.travel/en/things-to-see-and-do/nature-and-the-countryside/caves (accessed on 25 October 2019).

- Slovakia Travel. Show Caves in Slovakia. List of Accessible Caves in Slovaki. Available online: https://sacr3-files.s3-eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/PDF%20zoznamy/Jaskyne/Cave_EN.pdf (accessed on 27 October 2019).

- Slovakia Travel. National Park of Slovenský Raj. Available online: http://slovakia.travel/en/national-park-of-slovensky-raj (accessed on 25 October 2019).

- Slovakia Travel. Map. Available online: http://slovakia.travel/en/travel-essentials/map (accessed on 25 October 2019).

- Slovakia Travel. Vedúca Skamenelina. Available online: https://trip.slovakia.travel/event/8916bd61-1d6c-4c94-8fb6-a3461e56ff15?lang=en (accessed on 25 October 2019).

- Slovakia Travel. Planner. Available online: https://trip.slovakia.travel/explore?categories=bb05c2c7-6eeb-4e46-92d4-9ed3972e06d6,33796e39-e303-4848-a975-ea0d2369b9e9&lang=en¢er=19.7011,48.6402&accommodationPersons=2 (accessed on 25 October 2019).

- Slovakia Travel. Banská Bystrica Geopark. Available online: http://slovakia.travel/en/banska-bystrica-geopark (accessed on 25 October 2019).

- Slovakia Travel. Results to the Search Term ‘Geosite’. Available online: http://slovakia.travel/en/search?q=geosite (accessed on 25 October 2019).

- Slovakia Travel. Košice Region Tourism (app). Available online: http://slovakia.travel/en/kosice-region-tourism-app (accessed on 31 October 2019).

- Slovakia Travel. Mobile Applications. Available online: http://slovakia.travel/en/travel-essentials/mobile-applications?tx_viator_list%5Bdata_3012%5D%5Bfilters%5D%5B1%5D%5B%5D=748 (accessed on 1 November 2019).

- Slovakia Travel. Planner. Available online: https://trip.slovakia.travel/explore?lang=en¢er=19.7011,48.6402&categories=75994246-67ba-49a0-b868-bc33ac58d6c9 (accessed on 25 October 2019).

- Polish Tourism Organization. Underground Attractions. Available online: https://www.poland.travel/en/discover/underground-attractions (accessed on 15 October 2019).

- Slovakia Travel. Region of Gemer and Malohont. Available online: http://slovakia.travel/en/region-of-gemer-and-malohont (accessed on 22 October 2019).

- Slovakia Travel. Small Area but with Nine National Parks. Available online: http://slovakia.travel/en/things-to-see-and-do/nature-and-the-countryside/national-parks (accessed on 22 October 2019).

- Global Geoparks Network. What is a UNESCO Global Geopark? Available online: http://www.globalgeopark.org/aboutGGN/6398.htm (accessed on 25 October 2019).

- Czech Tourism. Bohemian Paradise—UNESCO Geopark: The Fairytale Bohemian Paradise Area. Available online: https://www.czechtourism.com/c/bohemian-paradise-unesco-geopark/ (accessed on 23 October 2019).

- Słomka, T.; Kicińska-Świderska, A.; Doktor, M.; Joniec, A. Katalog obiektów geoturystycznych w Polsce (obejmuje wybrane geologiczne stanowiska dokumentacyjne). Available online: https://archiwum.mos.gov.pl/g2/big/2009_07/8f91b006e724bc23a00b8bb5779d22bb.pdf (accessed on 18 December 2019).

- Bartuś, T.; Bębenek, S.; Doktor, M.; Golonka, J.; Ilcewicz-Stefaniuk, D. The Catalogue of Geotourist Sites in Nature Reserves and Monuments. Available online: http://www.kgos.agh.edu.pl/download/Katalog_Obiekow_Geoturystycznych_2012.pdf (accessed on 18 December 2019).

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).