Abstract

The emission of greenhouse gases associated with the combustion of hydrocarbons is a key factor in climate change, and in this context, increasing emphasis is being placed on the development of clean energy sources. The novel contribution of the article lies in identifying the energy potential of surface waters within energy systems transitioning away from fossil fuels. In the case of Poland, whose energy system has been based on coal for many decades, there are still many opportunities to expand energy production from renewable sources. One such source is the heat contained in surface waters. The research presented in this article focuses on the thermal structure of nine stratified lakes in Poland, examining changes over time and across different spatial profiles. Considering all temperature profiles, values ranged from 8.3 °C in May to 10.1 °C in September. In general, water warming occurs from May to the July–August transition, reaching a maximum of over 6 °C, while cooling takes place in the later phase of the analyzed season at a lower level, not exceeding 6 °C. It was found that the most thermally stable part of the water body was the layer between 15 m in depth and the bottom of the lakes, for which the heat resources were calculated. Using the basic physical properties of water, the amount of heat for this layer was determined. Assuming that technological processes do not reduce the water temperature below 4 °C (maximum water density), the hypothetical amount of available energy ranges from 630 to 101,000 MWh. The results indicate the high energy potential of lakes, which could be utilized in the future, provided further legal and economic analyses are conducted for specific cases. The study highlights the need to expand the long-term thermal monitoring of lakes, covering their entire vertical structure. Priority for such measurements should be given to lakes located near human settlements, as these have the highest potential for practical use.

1. Introduction

Humanity is experiencing the consequences of its actions in the context of the expansive exploitation of the natural environment and the centuries-long extraction and use of natural resources, which are becoming increasingly evident today. The emission of greenhouse gases associated with the combustion of hydrocarbons is a key driver of climate change, and in this context, increasing emphasis is being placed on the acquisition of “clean” energy sources. The search for renewable energy is gaining greater importance, and as Talaat et al. [1] note, many countries aim to rely exclusively on renewable energy by 2050. An analysis covering EU countries has shown that sustainable finance accelerates the transition to clean energy, reduces harmful emissions, and stimulates economic activity [2]. One of the main sources of renewable energy is hydropower [3], which plays an important role in achieving global carbon emission reduction goals [4]. In addition to the mechanical energy generated by water movement, in the context of the hydrosphere, its thermal energy can also be considered. Although its spatial reach is limited, solutions based on this type of technological potential are gaining increasing interest. This applies to buildings located near surface water bodies such as seas, rivers, ponds, lakes, etc. This system is based on surface water heat pumps, providing the ability to heat and cool buildings. Energy demand in buildings continues to rise [5], which is partly related to the expansion of air-conditioning systems in response to global warming. As European cities intensively pursue decarbonization, they are also grappling with unprecedented heatwaves driven by rising temperatures. The threat posed by extreme heatwaves is already a reality, making sustainable and clean cooling solutions an urgent priority [6]. The growing share of renewable energy means that building energy systems are increasingly relying on multi-source solutions such as photovoltaic panels, energy storage systems, and air-to-water heat pumps [7]. The annual operating costs of a system using solar energy and a heat pump powered by lake water amounted to only 50% of the heating costs of a biogas plant compared to a coal boiler (with a slightly higher initial investment) [8]. Using deep (cold) water from seas or lakes enables energy savings of over 85% compared to conventional air-conditioning systems [9]. The use of lake water as a heat source in a heat pump system for a residential building in Japan resulted in energy savings of approximately 60–70% for cooling and 30–45% for heating compared with an air–water heat pump and an air conditioner [10]. Due to their thermal inertia, large water bodies are suitable for both heat extraction and heat discharge in many parts of the world [11]. The high heat capacity of water makes lakes an attractive source of thermal energy for heat pumps used for building heating; see Fink et al., 2014 [12]. Lake-source cooling installations, where cold water is typically drawn and circulated through heat exchangers to remove heat from the system, result in significantly lower energy consumption [13]. As noted by Qiu et al. [14], lakes are storing increasing amounts of heat, and the enhanced release of this heat is a consequence of climate change and the shortening duration of ice cover. Moreover, attention should be paid to changes in the amount of heat stored in lakes, which depend primarily on their geographical location. In the case of Lake Ikeda (Japan), heat accumulation occurred from March to August, while heat release in the form of latent and sensible heat—under conditions of low net radiation—took place from September to February [15]. In contrast, observations of Lake Vegoritis (Greece) indicate that energy stored in the lake during spring and early summer is released to the environment later in the year as sensible heat [16]. For lakes in the temperate zone, this represents a two-season cycle of heat uptake and release.

The transformation of the energy market is a complex task in cases where it relies on a single type of resource; on the other hand, this provides broad opportunities for exploring and adapting new solutions. An example of such a situation is Poland, where coal was the key energy source for decades, but now the balance is increasingly shifting toward renewable energy sources. One component of clean energy is hydropower, which is primarily associated with the use of rivers [17]. However, attention should also be given to other elements of the hydrographic network, including more than 7000 lakes [18], which are particularly important in the area where they are most prevalent (northern Poland), covering about 30% of the country. Beyond the global-scale goal of reducing emissions, such initiatives are also significant at other spatial scales, where analysis of the energy system allows this objective to be achieved locally [19]. And although lakes are used as an energy source in various regions of the world, no broader initiatives in this area have yet been undertaken in Poland. Undoubtedly, the existence of several thousand lakes represents great potential in terms of utilizing the heat stored within them and harnessing it for human use, which could consequently reduce greenhouse gas emissions and lower energy production costs, and therefore deserves closer examination. Knowledge about the temporal distribution and availability of heat sources is crucial in order to incorporate them into full-scale energy systems [20]. Proper assessment of system performance and further design procedures require an understanding of the natural behavior of the heat source [21]. In this context, the key factors are lake morphometry and the thermal conditions prevailing within lakes. At present, long-term, cyclical, and contemporary data on this topic are lacking in Poland. It should be noted that the source material covers only the last dozen or so years, which corresponds to the period of particularly dynamic climate change.

The aim of the article encompasses two main issues. The first concerns the analysis of the thermal regime of lakes—its temporal and spatial variations within the lake basin. The second objective is to determine the heat resources of natural lakes in Poland. The material presented in the article and the results obtained may serve as a foundation for further research and actions in the context of utilizing lake energy. Such solutions would fit into the broader framework of the ongoing transformation of the energy mix, not only in Poland but also within the European Union and globally.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

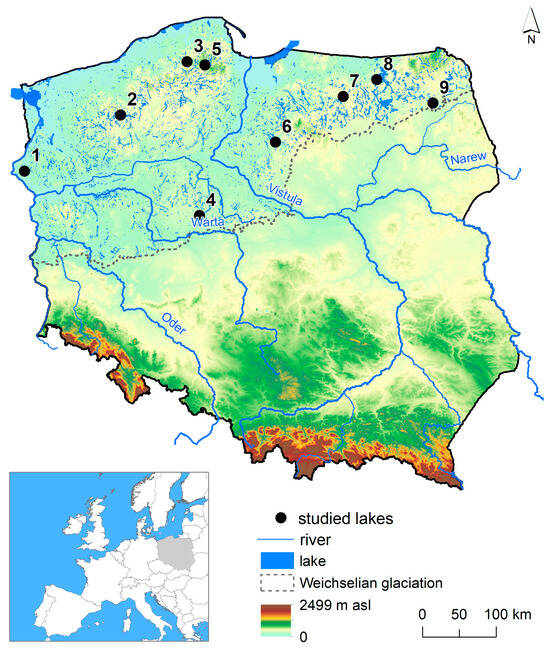

The study analyzes nine lakes located in northern Poland (Figure 1). The selection was based on the long-term (2007–2024) availability of data on thermal profiles. These lakes belong to the observation network of the Institute of Meteorology and Water Management. Their selection was also guided by their location within the main lake districts of Poland, for which the chosen water bodies are representative in terms of size and depth. An additional key selection criterion was lake depth, which ensured the presence of thermal stratification. The lakes are situated in northern Poland, a region shaped by the Scandinavian ice sheet responsible for their origin. The analyzed lakes vary in their morphometric characteristics, with surface areas ranging from 215 to 1499 hectares and maximum depths from 24.3 to 60.7 m (Table 1). A common feature of all the lakes is their dimictic nature and the formation of thermal stratification during the summer period.

Figure 1.

Location of the study area (numbering of lakes according to Table 1).

Table 1.

Morphometric parameters of the studied lakes [18].

2.2. Materials

The study utilized temperature measurements taken from thermal profiles conducted by the Institute of Meteorology and Water Management. These measurements were carried out between 2007 and 2024, during the period from May to October, at the deepest point of each lake. Temperature measurements were conducted at the deepest point of the lake, which is standard practice in limnological studies. This location allows the full vertical structure of water temperature to be captured. Before each measurement session, the probe was calibrated according to the device’s operating manual to eliminate potential measurement errors resulting from improper equipment preparation. The device was switched on 15 min prior to the start of measurements to allow it to acclimate to ambient conditions and perform self-calibration. After anchoring at the deepest point, the first measurement was taken at a depth of 40 cm below the water surface, ensuring complete immersion of the probe and maintaining consistency with water-temperature measurements taken at hydrological stations using standard water thermometers (INST/PL/02). Subsequent readings were taken at full-meter depth intervals (±1.0 m accuracy), with depth values determined from the calibrated cable on which the probe was suspended. To minimize potential deviations of the probe caused by wave action, an additional weight was attached to its end. The obtained results were recorded with an accuracy of 0.1 °C for water temperature.

The beginning of the metalimnion was defined as the shallowest depth at which a temperature drop of 1 °C was observed in the subsequent depth interval, while the end of the metalimnion was identified as the deepest point where this difference occurred. The depth of the thermocline was defined as the midpoint between these two extreme points of the metalimnion [22].

Determining the amount of heat stored in water requires consideration of its basic physical properties, including density, volume, specific heat capacity, and temperature change.

The calculation of heat resources was carried out according to the following formula:

where

Q = ρ × c × ΔT × V

- Q—amount of heat [J];

- ρ—density of water [1000 kg/m3];

- c—specific heat capacity of water ≈ 4186 J/(kg·°C);

- ΔT—change in temperature [°C];

- V—volume of the lake [m3].

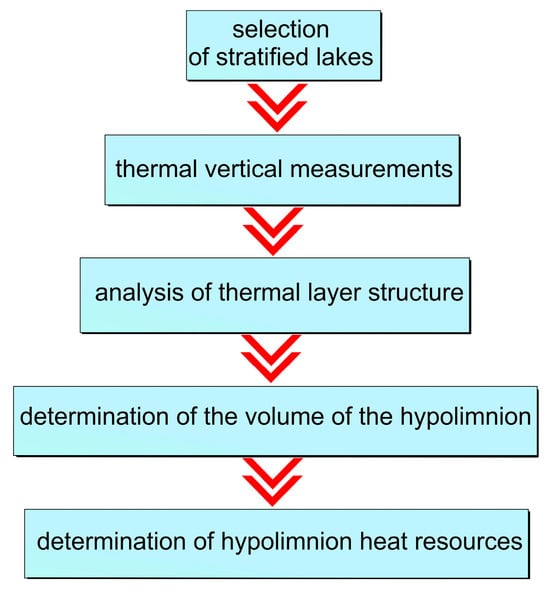

The methodological procedure is presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Stages of determining heat resources in the hypolimnion.

3. Results

3.1. Water Temperature

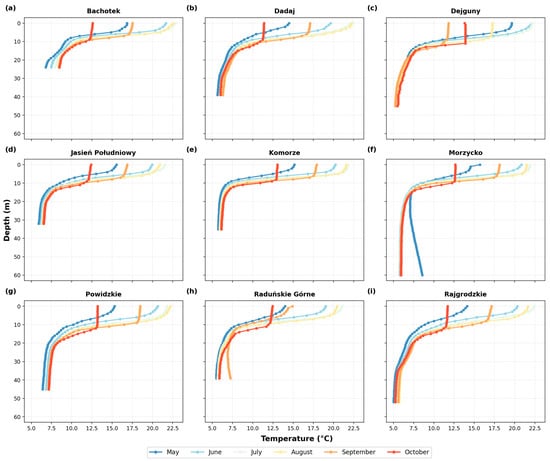

The thermal profiles over the six analyzed months (May–October) for the individual lakes varied relative to one another (Figure 3). These differences are most evident in the temperature distribution of the surface water layer, where maximum temperatures are reached in August and minimum temperatures in October in most cases. Considering the temperature of all profiles, it ranged from 8.3 °C (May) to 10.1 °C (September). For the analyzed months, the temperatures of individual lakes varied, respectively, from 7.2 °C (Raduńskie Górne) to 10.4 °C (Bachotek), and from 8.4 °C (Morzycko) to 13.1 °C (Bachotek).

Figure 3.

Average thermal profiles of the analyzed lakes in the years 2007–2024.

The most stable layer in terms of temperature variability is the hypolimnion, which is expected due to its limited interaction with climatic factors. As shown in the figure above, this layer exhibits variable thickness, which depends on the morphometry of the lakes. On average, for the analyzed lakes, the extent of this zone began at a depth of about 10 m, although cases of its occurrence starting from 14 m were also recorded (Rajgrodzkie Lake, Dejguny Lake).

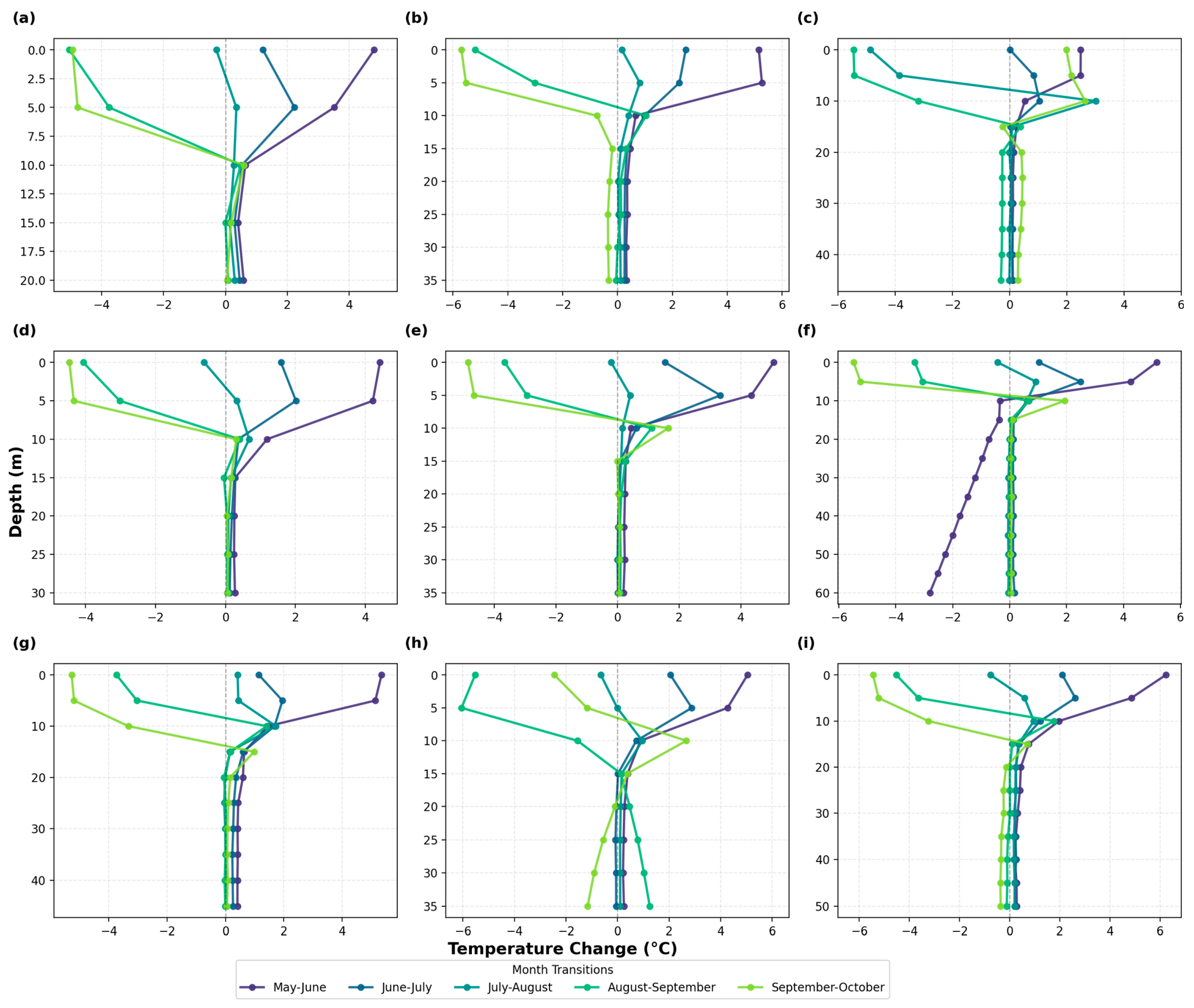

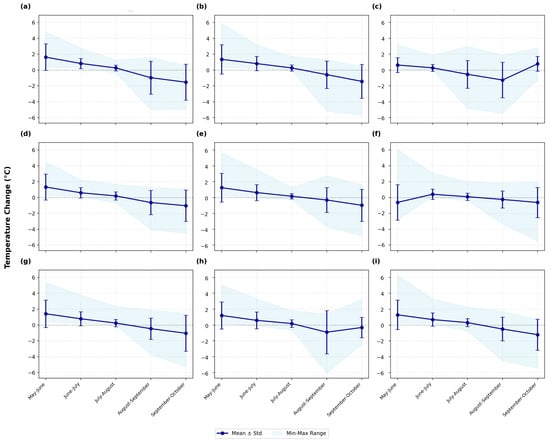

The analysis of month-to-month water-temperature variability in Figure 4 and Table 2 depicts a consistent seasonal thermal cycle across the nine lakes with clear lake-to-lake contrasts. It can be stated that the pattern of mean temperature changes is consistent. In general, water warming occurs up to the July–August transition, reaching a maximum of over 6 °C, while cooling takes place in the later phase of the analyzed season, at a lower level than previously and not exceeding 6 °C. From the transition from May to June most systems warm rapidly throughout the upper water column (mean changes ≈ +1.2 to +1.6 °C, with maxima up to +6.3 °C in Rajgrodzkie and +5–6 °C in several lakes), and relatively large standard deviations (≈1.6–1.9 °C) indicate strong vertical heterogeneity surface layers warming much faster than deep water as stratification sets in. The transition from June to July shows continued but more modest warming (means ≈ +0.6–0.8 °C) and reduced spread, while the changes in the transition from July to August are near zero in most lakes (means ≈ +0.1–0.3 °C and small medians), consistent with a midsummer plateau when stratification is strongest and temperatures stabilize. Cooling begins in the transition from August to September (means typically −0.3 to −1.3 °C) and intensifies in the transition from September to October (means often ≈−1.0 to −1.5 °C, with minima near −5 to −5.7 °C in several lakes), reflecting erosion of the thermocline and progression toward autumnal mixing. The behavior of Morzycko shows small positive or even negative mean changes in early summer (e.g., −0.6 °C in the transition from May to June) and generally muted variability suggests a deep, well-buffered hypolimnion that resists rapid surface forcing. In contrast, Bachotek, Powidzkie, Komorze, and Rajgrodzkie exhibit larger early-summer warming and sharper late-season cooling, indicative of less buffered basins that respond more quickly to atmospheric conditions. Dejguny shows a notable anomaly with the transition from September to October mean warming (+0.7 °C) despite the general cooling trend likely being an episodic event (e.g., transient heat input or mixing that brought warmer intermediate water upward).

Figure 4.

Month-to-month water-temperature variability (°C) for (a) Bachotek, (b) Dadaj, (c) Dejguny, (d) Jasień Południowy, (e) Komorze, (f) Morzycko, (g) Powidzkie, (h) Raduńskie Górne, and (i) Rajgrodzkie, respectively.

Table 2.

Summary statistics of month-to-month water-temperature change (°C) by lake.

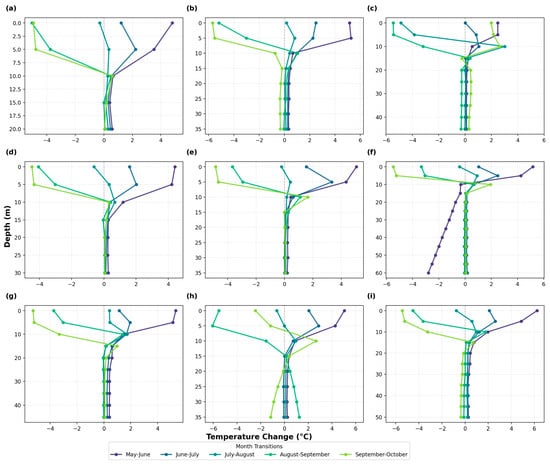

The water-temperature variability in Figure 5 for specific depths shows a depth-dependent seasonal cycle with clear timing. This figure illustrates the greatest dynamics of change, which pertain to the epi- and metalimnion. In the former case, temperature variations may exceed 10 °C over the entire analyzed season. In contrast, the range of thermal curve variations for the hypolimnion in most cases does not exceed 1 °C.

Figure 5.

Depth-specific month-to-month water-temperature change (°C) for (a) Bachotek, (b) Dadaj, (c) Dejguny, (d) Jasień Południowy, (e) Komorze, (f) Morzycko, (g) Powidzkie, (h) Raduńskie Górne, and (i) Rajgrodzkie, respectively.

Spring onset during transition from May to June is dominated by strong surface warming of about +4–6 °C at 0 m across most lakes (e.g., Rajgrodzkie +6.2 °C, Powidzkie +5.3 °C, Komorze +5.0 °C), while deep layers change little (≈+0.1–0.4 °C) or even cool in very deep basins (Morzycko −2 to −2.8 °C below 30–60 m), marking rapid thermocline formation. Early summer (transition from June to July) shows continued but weaker warming concentrated in the upper 0–10 m (typically +1–3 °C at 0–5 m) with near-zero changes at depth, indicating a stable stratification. Midsummer (transition from July to August) transitions to a plateau: surface changes hover around zero or slightly negative (e.g., Bachotek −0.2 °C; Rajgrodzkie −0.7 °C), while small positive increments just below the thermocline (5–15 m) appear in many lakes (e.g., Powidzkie +1.7 °C at 10 m), consistent with the downward redistribution of heat into the metalimnion. Late summer to early autumn (August → September) produces the largest surface cooling (−3 to −5.5 °C at 0–5 m in nearly all lakes), while mid–deep waters warm slightly (≈+0.3 to +1.4 °C; e.g., Komorze +1.1 °C at 10 m, Rajgrodzkie +1.7 °C at 10 m, Raduńskie Górne +1.4 °C at 39 m), signaling thermocline erosion and entrainment. Autumn (September → October) continues strong surface cooling (≈−4.5 to −5.7 °C at 0–5 m), with mixed responses below: several lakes show warming around ~10 m (e.g., Komorze +1.6 °C, Morzycko +1.9 °C), while others cool at that depth (Rajgrodzkie −3.2 °C), reflecting the depth of the mixing front as turnover proceeds. Two notable features are Morzycko’s deep, buffered hypolimnion, which changes little most of the season, and Dejguny’s at transition from September to October basin-wide warming (e.g., +2.6 °C at 10 m).

3.2. Heat Resources

Based on the above thermal characteristics of the analyzed lakes, the smallest water-temperature fluctuations occur at depths of 15 m and below. For this layer, the calculation of heat resources was subsequently performed. The average temperature of the lakes within this depth range was 6.7 °C and showed little variation, differing by only about 0.5 °C between individual lakes. On a monthly basis, the largest differences were recorded in October (2.0 °C), and the smallest in May (1.2 °C). The diagram is presented in Figure S1.

In determining the amount of heat, three scenarios were considered, assuming a water-temperature change of 1 °C and 1.5 °C (Table 3), as well as the theoretically maximum temperature decrease, defined as not exceeding the threshold of maximum water density, which corresponds to 4 °C. Maintaining this condition allows the natural course of water-mixing processes, resulting from convective movements (density differences caused by temperature changes), to be preserved. Based on the obtained results, these data were compiled on a monthly basis (Table 4).

Table 3.

A potential amount of energy [MWh] obtainable from the hypolimnion layer with a water-temperature change of 1.0 °C and 1.5 °C.

Table 4.

Potential amount of energy obtainable from the hypolimnion layer at the maximum water-temperature change (MWh/°C/).

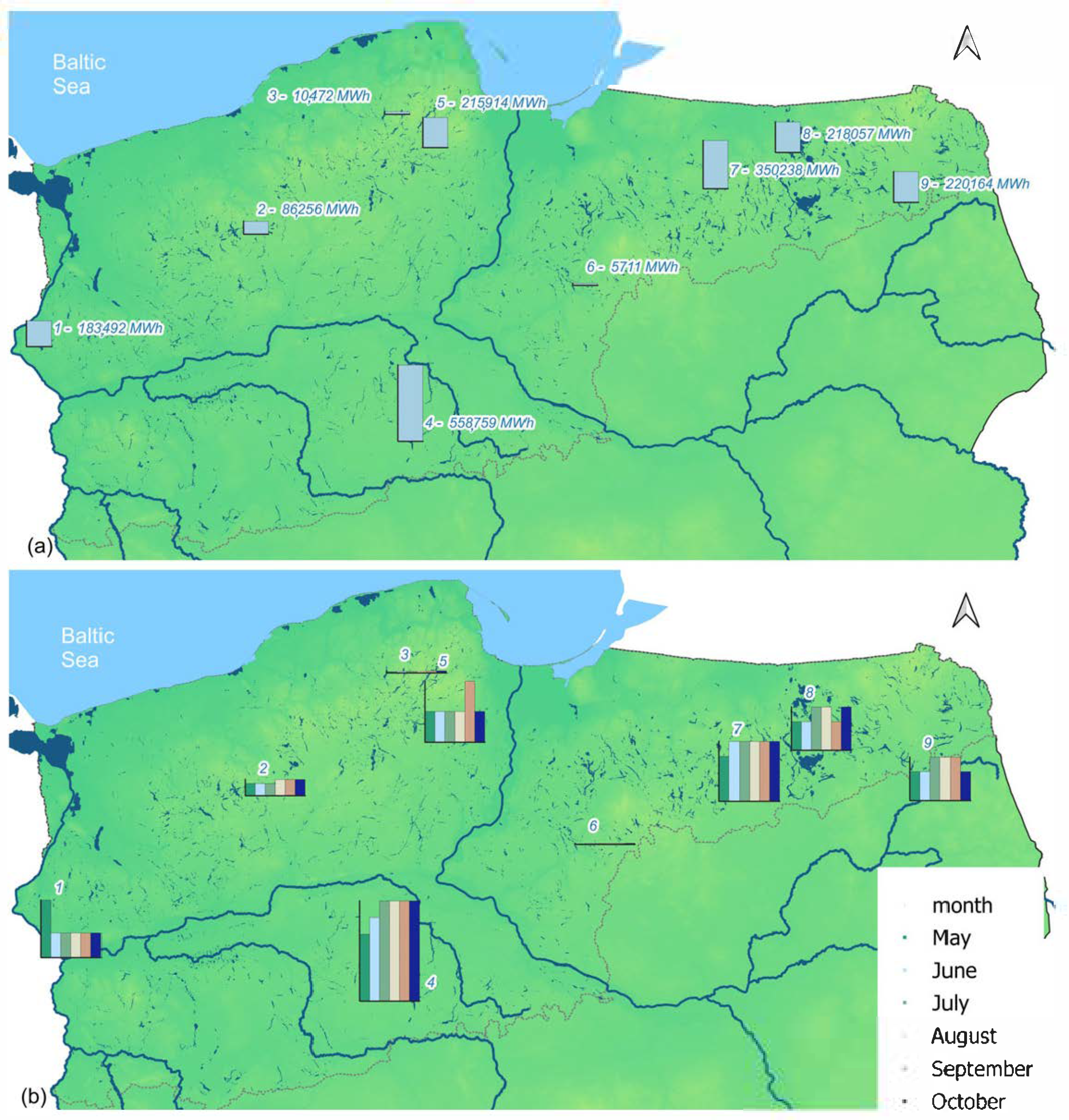

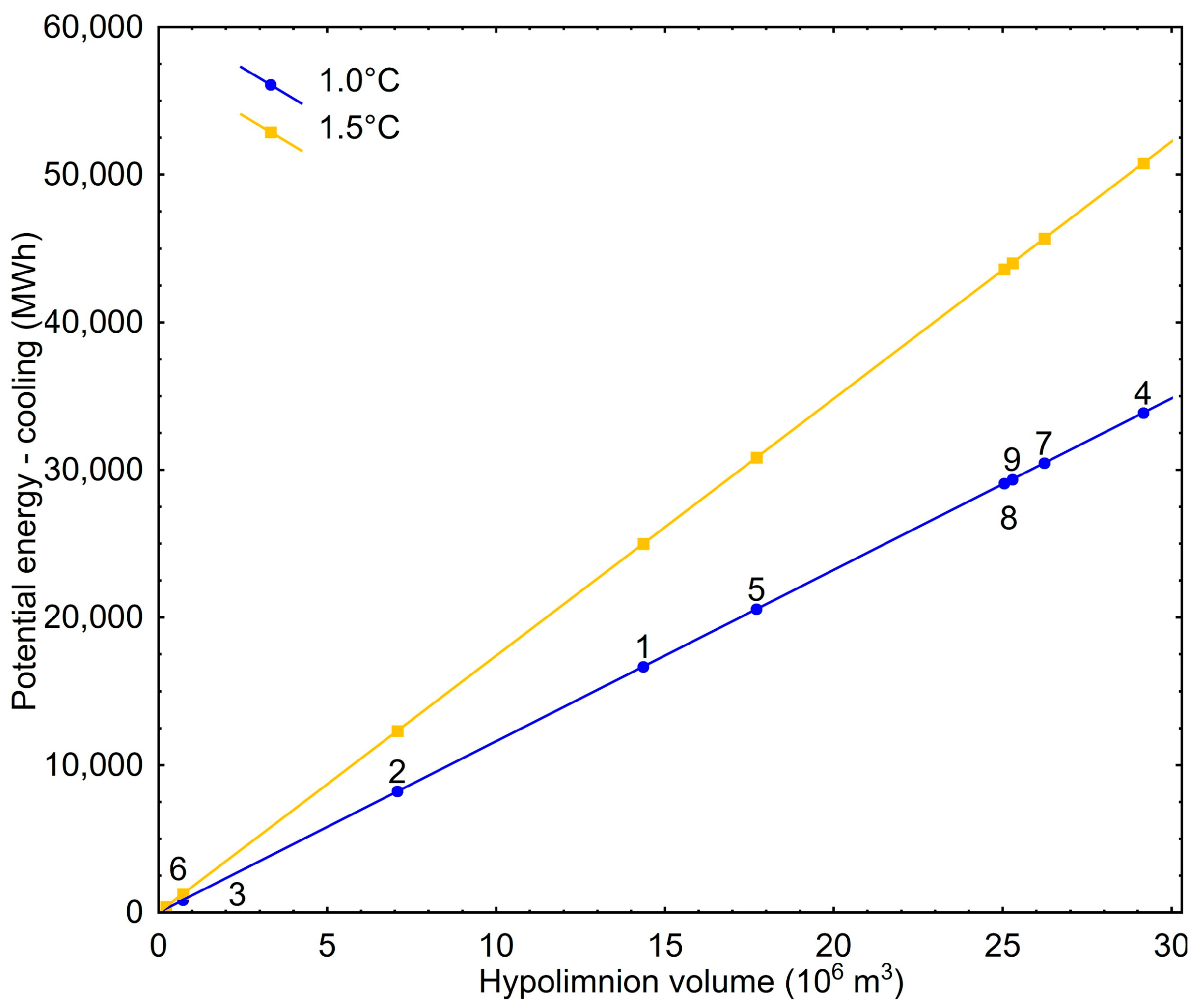

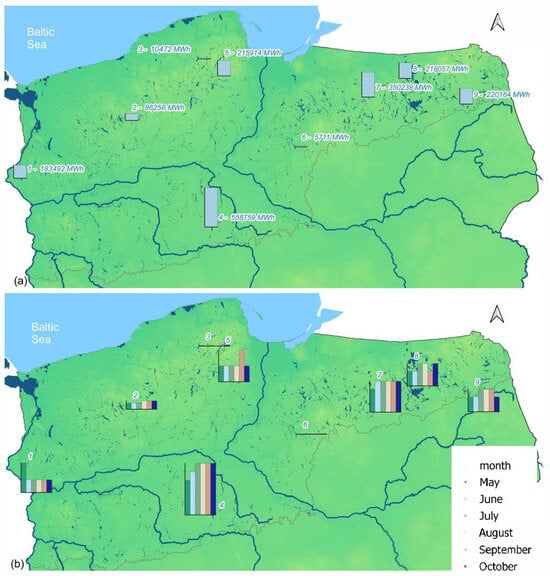

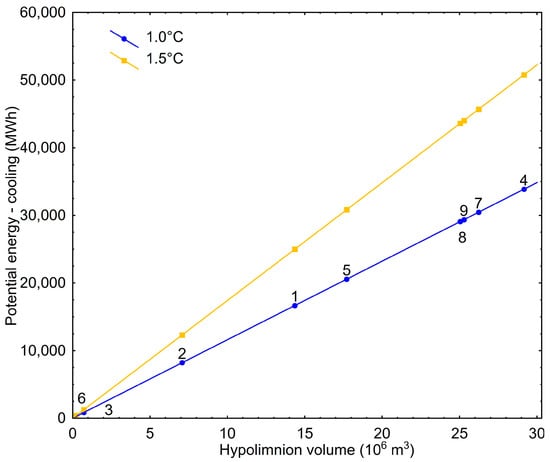

The amount of energy for a uniform temperature decrease (1.0 and 1.5 °C) ranges from 250 to over 33,000 MWh, and in the second scenario from over 380 to 50,700 MWh. Assuming a heat pump coefficient of performance (COP) of 4.5, the amount of energy consumed ranges from 56.4 to 11,288 MWh. This variation is related to the morphometric parameters of the lakes; specifically, the volume of the most thermally stable water layer. However, the theoretical energy potential in individual months can be higher. Considering the previous assumption (not exceeding the 4 °C threshold), the lowest average energy available across all lakes occurs in May (30,593 MWh), and the highest in August (37,983 MWh). For individual cases, the energy can range from over 630 MWh (Bachotek, May) to more than 101,000 (Powidzkie, July, August, September, October). It should be emphasized that only Lake Powidzkie exceeded the 100,000 MWh level. Figure 6 presents the values for the May–October period and for individual months. The spatial distribution of the lakes shows no discernible pattern, reducing their energy potential to individual morphometric characteristics. In general, considering the maximum possible water-temperature changes, Lake Powidzkie has the highest energy potential, while Lakes Bachotek and Jasień have the lowest. The potential for energy extraction in individual months is relatively proportional. In Lake Morzycko, the highest energy potential occurs in May, whereas in Lake Raduńskie it occurs in September.

Figure 6.

Energy/heat potentially obtainable from the analyzed lakes for cooling, with reference to the May–October period (a) and for individual months (b).

Figure 7 shows the relationship between the potential amount of energy [MWh] obtainable from the hypolimnion layer with water-temperature changes of 1.0 °C (blue line) and 1.5 °C (orange line). Given the similar temperatures of the deepest water layers in the individual lakes, the amount of heat depends primarily on the volume of this layer. This is a linear relationship determined by the amount of water stored in the hypolimnion. The primary factor determining the possibility of energy extraction from individual lakes is the volume of the hypolimnion. In the studied lakes, the ratio of the hypolimnion volume to the total volume of the lake basin ranged from approximately 2% in Lakes Bachotek and Jasień to about 29% in Lakes Raduńskie and Morzycko Lake.

Figure 7.

Relationship between the volume of the hypolimnion layer in the studied lakes and the potential amount of energy.

4. Discussion

Proper utilization of the thermal energy contained in lakes requires a better under-standing of the lake system itself [23]. Luo et al. [24] emphasize that before designing heat pump systems using lake water, analyses concerning the lakes themselves, local conditions, and relevant regulations must be carried out. A key element is the thermal conditions prevailing in lakes, which depend primarily on their location (climatic zone) and morphometric characteristics. In the latter case, depth is particularly important, as it determines the formation of thermal stratification. The formation of three layers—epilimnion, metalimnion, and hypolimnion—is crucial for the functioning of lake ecosystems, both from a natural and economic perspective. Based on long-term monitoring, it has been established that the thermal conditions of individual lakes are variable, taking into account both specific months and depths. In all cases, the deepest layer was the most stable, although some variation was still observed. Despite being one of the deepest among the analyzed lakes, Lake Powidzkie exhibits the highest hypolimnion temperatures. This situation may result from the lake’s hydraulic connection with groundwater, which influences the thermal conditions in the near-bottom layer. The lake basin, in its deepest parts, cuts through underlying clay layers and is in contact with multiple aquifer levels [25,26]. This effect is particularly pronounced during periods of low water levels in the lake, especially in summer and early autumn, as well as during dry years, when deep aquifer drainage occurs. The recent trend of decreasing water levels in Lake Powidzkie [27], leading to continuous drainage of surrounding aquifer layers, causes deviations in hypolimnion temperatures compared to those observed in other lakes.

In the context of widespread human activity, lakes are an important resource utilized across various sectors of the economy. This also applies to the expanding energy market, where lakes are becoming one of its components. Lakes represent a source of geothermal energy, helping to meet the growing demand for renewable energy [28]. Water and groundwater sources experience smaller temperature fluctuations compared to air, which ensures greater stability [29]. Considering the three-dimensional structure of lake basins, different zones have varying potential for adaptation to such purposes. Shallow layers of lakes are characterized by higher biological activity; therefore, as observed in Swiss lakes, for planning thermal infrastructure, it is recommended to use zones below 15 m [11]. Additionally, surface water layers exhibit high temperature variability throughout the year due to cyclical changes in climatic conditions [30]. These changes are also evident on an hourly scale [31]. Taking into account the spatial and temporal characteristics of water temperature and quality distribution, water intake should be installed in the middle and lower layers of the lake [32]. Therefore, this study focused on the most thermally stable water layer, highlighting the large heat resources stored therein. Depending on the assumed theoretical operational scenarios, the results showed significant potential for utilization. Assuming that the water temperature in the hypolimnion layer should never drop below 4 °C (the temperature of maximum density), an average of 34,242 MWh can be obtained from the analyzed lakes. For individual lakes, this value varied widely, from 635 to 101,592 MWh. As previously indicated, this is influenced not only by the morphometric characteristics of the lakes (their depth) but also by environmental conditions in the surrounding area. Geological conditions and significant groundwater inflow can substantially affect thermal characteristics (and consequently heat resources), even in lakes of the same depth.

Lake water can serve as an energy source, utilized in heat pump systems while simultaneously contributing to the reduction in greenhouse gas emissions. District cooling using lake water (similar to seawater) is a technology that is beginning to have a significant impact on energy savings, providing an alternative to conventional air-conditioning systems [9]. As the same authors note, such a system can be adopted where sufficient cold-water resources are available near a high air-conditioning load, ensuring stabilization of energy costs in the building’s budget. In Europe, approximately 17% of cooling demand near lakes can be met by systems using lake water [33]. For example, water intake from Lake Ontario at a depth of 83 m in Toronto allows for energy savings of 85 million kWh and a reduction in CO2 emissions by 79,000 tons per year [34]. The system operating at Cornell University (USA) draws water from Lake Cayuga (at a depth of 76 m), achieving an eightfold reduction in energy consumption compared to the previous cooling system [13]. These cases demonstrate the significant potential of extracting energy from lakes, which is also supported by the results obtained for selected lakes in Poland. This is particularly important in the context of current and future climate change, where global warming is one of humanity’s greatest challenges. The highest heat resources were recorded in August, one of the warmest months in Poland. This situation is consistent with the relationship between heat availability and energy demand for cooling systems. The increasing demand for building cooling is one of the most significant—and often overlooked—energy issues today. Without intervention, electricity demand associated with cooling is expected to more than triple by 2050 [35]. Thermal stratification maintains large quantities of cold water in the lower layers of deep lakes. This water is sufficiently cold to cool buildings effectively through simple circulation via heat exchangers. In this case, a heat pump is not required for cooling, and energy consumption is significantly reduced [36].

One of the main limitations in using surface waters as a heat source is their location relative to end users. Giordano et al. [37], based on studies conducted in NW Italy, concluded that areas near lakes can be utilized for the construction of infrastructure with various purposes, including space heating and cooling as well as domestic hot-water production. For the analyzed lakes, an important aspect is the presence of numerous buildings and recreational infrastructure located near the shoreline or its immediate vicinity. Lakes are among the main attractions of northern Poland [38], and their presence drives the economic development of the surrounding regions, attracting tourists and investors involved in recreational and leisure activities. For example, within a 100 m buffer zone around Lake Powidzkie, there are 19 facilities in this sector (hotels, restaurants, campsites, guesthouses), with additional temporary food service points appearing during the summer season. Moreover, the adaptation of lake energy to urban areas and buildings of various functions (residential, commercial, etc.) becomes an important consideration. Cities in northern Poland vary in the number of lakes they contain; for instance, Olsztyn (with a population of 160,000) has 16 lakes of different morphometric characteristics, highlighting the broad potential for research on utilizing their energy resources.

As noted in the introduction, Poland has over 7000 natural lakes, which, in light of the results presented in this study, could serve as a significant alternative energy source. Understanding the specific functioning of these ecosystems is crucial for further actions aimed at harnessing renewable energy. For example, as Chen and Zhang [39] indicate, in the case of two lakes with identical volumes, the deeper lake is more advantageous for improving cooling efficiency than the larger one. This highlights the complexity of processes occurring in lacustrine environments, which must be considered when planning potential investments based on lake water. It should be emphasized that the conducted research refers to theoretical (hypothetical) amounts of heat, the practical extraction of which would require an individual approach to each lake, taking into account its physicochemical and hydrobiological characteristics. In addition, uncertainties related to future climate change projections should be considered, as they will affect lake functioning (through a shortening of the ice-cover season, changes in the duration of lake stratification, and a decrease in dissolved oxygen levels resulting from rising water temperatures). These factors may impose limitations on the use of lakes as energy sources. A foundation for further legal and technical measures is knowledge of the thermal regime of lakes, including its seasonal and depth-related variations. The results obtained in this article indicate the need to expand long-term thermal monitoring of lakes, encompassing their entire vertical structure. Such measurements should initially focus on lakes in close proximity to various types of development (residential, recreational, and tourist areas, as well as cities). Additionally, consideration should be given to extending these observations throughout the entire year. These assumptions are necessary to counteract adverse climatic changes, whose scale and intensity are increasing and, according to forecasts, will continue to intensify with each passing decade.

5. Conclusions

Expanding the potential for new energy sources is particularly important today and in the future, given the unfavorable climate change forecasts. In the case of Poland, whose energy system was based on coal for many decades, there remain numerous opportunities to increase the use of renewable energy sources. One such element is the thermal energy of surface waters, and the analysis presented in this article sheds light on this issue, allowing for drawing the following conclusions:

- (1)

- Deep, stratified lakes in northern Poland store significant amounts of thermal energy, particularly within the hypolimnion, which remains thermally stable for much of the year.

- (2)

- The results indicate a potential research direction focusing on the hypolimnion in relation to lakes in different regions of the world.

- (3)

- The estimated heat resources show substantial variability among lakes, controlled primarily by maximum depth, lake volume, and the persistence of thermal stratification.

- (4)

- The calculated thermal energy resources indicate that the selected lakes may serve as a viable supplementary heat source for low-temperature energy systems.

- (5)

- Lakes located near cities and recreational centers offer the most favorable conditions for the practical use of stored thermal energy, due to local heat demand and the costs associated with technical installations.

- (6)

- It should be emphasized that the presented results refer to theoretical resources, and their actual availability depends on numerous factors (legal, ecological, and hydrobiological). Any potential implementation of lake-based solutions would therefore require a detailed, further interdisciplinary analysis of each individual case.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/resources15020027/s1, Figure S1: Scheme for using lake water as a heat source.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.P.; methodology, M.P. and T.A.; software, T.A.; validation, M.P. and T.A.; formal analysis, M.P. and T.A.; investigation, M.P. and T.A.; resources, M.P. and B.N.; data curation, M.P.; writing—original draft preparation, M.P., T.A., B.N., S.H. and M.S.; writing—review and editing, M.P., T.A., S.H. and M.S.; visualization, T.A. and M.S.; supervision, M.P.; project administration, M.P.; funding acquisition, M.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Dataset available on request from the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Talaat, F.M.; Kabeel, A.; Shaban, W.M. The role of utilizing artificial intelligence and renewable energy in reaching sustainable development goals. Renew. Energy 2024, 235, 121311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Tan, L.; Zhao, J. Sustainable finance and renewable energy investment as dual drivers of economic growth and environmental sustainability in the European Union. Res. Econ. 2025, 79, 101065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adu, D.; Jianguo, D.; Darko, R.O.; Asomani, S.N. Overcoming CO2 emission from energy generation by renewable hydropower—The role of pump as turbine. Energy Rep. 2023, 9, 114–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, G.; Lin, S.; Llewellyn, A.; Pillai, A.; Zarzyski, E.; Singh, S.; Quinn, J. Adapting Hydropower Operations to Support Renewable Energy Transitions and Freshwater Sustainability in the Columbia River Basin. In Proceedings of the Systems and Information Engineering Design Symposium (SIEDS), Charlottesville, VA, USA, 27–28 April 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Space Cooling. Available online: https://www.iea.org/energy-system/buildings/space-cooling (accessed on 14 December 2025).

- EU Covenant of Mayors. Available online: https://eu-mayors.ec.europa.eu/en/Decarbonised-district-cooling-how-cities-can-both-refresh-and-detox (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Jang, D.; Kim, I.; Kim, W. Optimization and operation of integrated air-water heat pump systems with energy storage and renewable energy based on deep learning. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 111, 113344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Xu, K.; Lv, T. Heat pump heating systems combined with solar energy and lake water source for the biogas digester. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2013, 6, 291–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Looney, C.M.; Oney, S.K. Seawater district cooling and lake source district cooling. Energy Eng. 2007, 104, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, L. Evaluation the performance of lake water used as heat source for heat pump system in a typical Japanese resident building. Geomate J. 2017, 12, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudard, A.; Wüest, A.; Schmid, M. Using lakes and rivers for extraction and disposal of heat: Estimate of regional potentials. Renew. Energy 2019, 134, 330–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fink, G.; Schmid, M.; Wüest, A. Large lakes as sources and sinks of anthropogenic heat: Capacities and limits. Water Resour. Res. 2014, 50, 7285–7301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zogg, R.; Roth, K.; Brodrick, J. Lake-source district cooling systems. ASHRAE J. 2008, 50, 55–57. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, Y.; Chen, J.; Chen, D.; Thiery, W.; Mercado-Bettín, D.; Xiong, L.; Xia, J.; Woolway, R.I. Enhanced heating effect of lakes under global warming. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 3954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Momii, K.; Ito, Y. Heat budget estimates for lake Ikeda, Japan. J. Hydrol. 2008, 361, 362–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gianniou, S.K.; Antonopoulos, V.Z. Evaporation and energy budget in Lake Vegoritis, Greece. J. Hydrol. 2007, 345, 212–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kałuża, T.; Hämmerling, M.; Zawadzki, P.; Czekała, W.; Kasperek, R.; Sojka, M.; Mokwa, M.; Ptak, M.; Szkudlarek, A.; Czechlowski, M.; et al. The hydropower sector in Poland, historical development and current status. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 158, 112150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choiński, A. Katalog Jezior Polski; Wydawnictwo Naukowe UAM: Poznań, Poland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ikäheimo, J.; Weiss, R.; Kiviluoma, J.; Pursiheimo, E.; Lindroos, T.J. Impact of power-to-gas on the cost and design of the future low-carbon urban energy system. Appl. Energy 2022, 305, 117713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, R.; Persson, U. Mapping of potential heat sources for heat pumps for district heating in Denmark. Energy 2016, 110, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kindaichi, S.; Nishina, D.; Wen, L.; Kannaka, T. Potential for using water reservoirs as heat sources in heat pump systems. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2015, 76, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantin, A.; Beisner, B.E.; Gunn, J.M.; Prairie, Y.T.; Winter, J.G. Effects of thermocline deepening on lake plankton communities. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2011, 68, 260–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faessler, J.; Hollmuller, P.; Lachal, B.; Viquerat, P.A. Valorisation thermique des eaux profondes lacustres: Le réseau genevois GLN et quelques considérations générales sur ces systèmes. Arch. Sci. 2012, 65, 215–228. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, J.; Xin, S.; Huang, Y.; Hu, Q.; Wang, J.; Zhang, C. Quantitative evaluation of environmental influence of heat emission from lake water heat pump. Int. J. Refrig. 2025, 175, 288–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, B. Reżim hydrologiczny Jeziora Powidzkiego oraz jego znaczenie w lokalnych i regionalnych systemach wodonośnych. In Jezioro Powidzkie Wczoraj i Dziś; Nowak, B., Ed.; IMGW-PIB: Warszawa, Poland, 2019; pp. 37–48. [Google Scholar]

- Nowak, B.; Przybyłek, J. Recharge and drainage of lakes in Powidzki Landscape Park in the conditions of increased anthropogenic and environmental pressure (Central-Western Poland). Geol. Q. 2020, 64, 205–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, B.; Ptak, M. Natural and anthropogenic conditions of water level fluctuations in lakes—Powidzkie Lake case study (Central-Western Poland). J. Water Land Dev. 2019, 40, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, D.K.; Lee, Y. Numerical Simulations on the Application of a Closed-Loop Lake Water Heat Pump System in the Lake Soyang, Korea. Energies 2020, 13, 762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardemil, J.M.; Schneider, W.; Behzad, M.; Starke, A.R. Thermal analysis of a water source heat pump for space heating using an outdoor pool as a heat source. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 33, 101581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ptak, M.; Sojka, M.; Choiński, A.; Nowak, B. Effect of environmental conditions and morphometric parameters on surface water temperature in Polish lakes. Water 2018, 10, 580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ptak, M.; Sojka, M.; Nowak, B. Daily water temperature distribution and fluctuations in Lake Kierskie. Quaest. Geogr. 2019, 38, 41–49. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, G.D.; Zhang, Z.; Luo, J.; Wan, X.; Liu, C. Analysis of the water intake technology of open-lakes Water Source Heat Pump system in Chongqing. Adv. Mater. Res. 2011, 250, 3168–3172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eggimann, S.; Vivian, J.; Chen, R.; Orehounig, K.; Patt, A.; Fiorentini, M. The potential of lake-source district heating and cooling for European buildings. Energy Convers. Manag. 2023, 283, 116914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, L.; Herbert, Y. The use of deep water cooling systems: Two Canadian examples. Renew. Energy 2009, 34, 727–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostadin, F. The Future of Cooling: Opportunities for Energy Efficient Air Conditioning; International Energy Agency: Paris, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Sarbu, I.; Sebarchievici, C. General review of ground-source heat pump systems for heating and cooling of buildings. Energy Build. 2014, 70, 441–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, N.; Canalis, L.; Ceppa, L.; Comina, C.; Degiorgis, L.; Giuliani, A.; Mandrone, G.; Marcon, G. How open-loop heat pumps on lakes can help environmental control: An example of geothermal circular economy. In Proceedings of the European Geothermal Congress, Strasbourg, France, 19–24 September 2016; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Ptak, M. Jeziora Pojezierza Wielkopolsko—Kujawskiego jako baza rekreacyjno—Wypoczynkowa. Badania Fizjogr. 2012, A63, 111–120. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Zhang, G. Study on the application of closed-loop lake water heat pump systems for lakefront buildings in south China climates. J. Renew. Sustain. Energy 2014, 6, 033125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.