Abstract

Climate change and river flow alterations in the Mekong River have significantly exacerbated drought conditions in the Vietnamese Mekong Delta (VMD). Understanding the temporal dynamics and propagation mechanisms of drought, coupled with the compounded impacts of human activities, is crucial. This study analyzed meteorological (1992–2021) and hydrological (2000–2021) drought trends in the Lower Mekong River Basin (LMB) using the Standardized Precipitation Index (SPI) and the Streamflow Drought Index (SDI), respectively, complemented by Mann–Kendall (MK) trend analysis. The results show an increasing trend of meteorological drought in Cambodia and Lao PDR, with mid-Mekong stations exhibiting a strong positive correlation with downstream discharge, particularly Tan Chau (Pearson r ranging from 0.60 to 0.70). A key finding highlights the complexity of flow regulation by the Tonle Sap system, evidenced by a very strong correlation (r = 0.71) between Phnom Penh and the 12-month SDI lagged by one year. Crucially, the comparison revealed a shift in drought severity since 2010: hydrological drought has exhibited greater severity (reaching severe levels in 2020–2021) compared to meteorological drought, which remained moderate. This escalation is substantiated by a statistically significant discharge reduction (95% confidence level) at the Chau Doc station during the wet season, indicating a decline in peak flow due to upstream dam operations. These findings provide a robust database on the altered hydrological regime, underlining the increasing vulnerability of the VMD and motivating the urgent need for comprehensive, adaptive water resource management strategies.

1. Introduction

Water is one of the most critical resources globally, underpinning socio-economic development, public health, food systems, and energy security, while also shaping patterns of access, inequality, and vulnerability across places and social groups [1,2]. In Southeast Asia, water operates simultaneously as an engine of socio-economic development and as a socio-spatial locus of vulnerability, shaped by uneven adaptive capacities, differentiated access to resources, and longstanding structural inequalities [3,4,5]. Although freshwater resources are abundant at the global scale, their markedly uneven spatial and seasonal distribution has intensified scholarly interest in water scarcity, shortage, and stress, conditions in which agricultural and socio-economic demands exceed available supply [3,6,7]. The UN World Water Development Report (2020) underscores that climate change, together with rapidly rising freshwater demands, is placing mounting pressure on the world’s already stressed water resources [8]. For Southeast Asian societies, where freshwater is fundamental to drinking water provision, agriculture, industry, and wider social–ecological development, these pressures are particularly concerning [3,4,5]. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) similarly notes that climate change will amplify the frequency and severity of hydro-meteorological hazards, including floods and droughts [9]. Recent shifts in temperature, rainfall, and evapotranspiration regimes demonstrate this reality, with rainfall—arguably the most critical driver within the hydrological cycle—showing increasing variability and stronger links to both flood and drought occurrence [10,11,12,13,14]. In addition, alterations in rainfall patterns, shifts in land use, water storage, and extraction methods together modify the spatiotemporal dynamics of hydrology and water resources throughout the region [13,15,16]. Accordingly, assessing long-term river discharge trends provides critical insight into the trajectory of water resource change and enables a clearer diagnosis of climate-driven shifts in hydrological variables, including their direction and amplitude, which is vital for informed water management [17,18,19].

Hydrological drought is typically understood as the manifestation of rainfall deficits in reduced water supply, expressed through declining streamflow, reservoir and lake levels, and groundwater tables. This contrasts with meteorological drought, which refers primarily to atmospheric dryness, rainfall deficits, and the duration of dry periods [20,21]. However, raw historical records often conceal key climatic features—such as serial dependence, underlying probability distributions, seasonality, and long-term trends—making systematic trend detection essential for assessing whether hydro-meteorological variables exhibit increasing, decreasing, or stable tendencies.

Accordingly, numerous studies have examined spatiotemporal trends in hydrological variables (for example, streamflow) and meteorological parameters (including rainfall, evaporation, temperature, and humidity) using both parametric and non-parametric techniques. Chakraborty et al. [22] for instance, investigated the spatial variability of rainfall in the Seonath Basin, India, using the Mann–Kendall (MK) test. Traditional trend-identification methods—such as the MK test [23,24], Spearman’s rho test [25], and trend-slope estimators—remain widely applied. The Standardized Precipitation Index (SPI) and various streamflow indices have been central to regional analyses of meteorological and hydrological droughts, such as those conducted in the Awash River Basin, Ethiopia [26].

Drought indices play a crucial role in characterizing drought magnitude, duration, severity, and spatial extent. Widely used meteorological drought indices include the SPI, the Standardized Precipitation Evapotranspiration Index (SPEI), the Reconnaissance Drought Index (RDI), and the Palmer Drought Severity Index (PDSI). Hydrological drought assessment commonly employs the Standardized Streamflow Index (SSI) and the Streamflow Drought Index (SDI) [27,28,29,30]. Single-input indices such as SPI—which rely solely on rainfall—capture atmospheric drought conditions, whereas multi-variable indices such as SPEI incorporate both rainfall and air temperature, thereby offering a more complete representation of meteorological and hydrological drought processes [23,24,25]

Building on these developments, a wide suite of drought indices now exists, incorporating rainfall, temperature, streamflow, evapotranspiration, and soil moisture [31,32,33,34]. Alongside these indices, traditional non-parametric trend-detection methods remain central. Sen’s slope estimator (also known as the Theil–Sen estimator) the Theil–Sen Median (TSM) [35], and the MK test [36,37] are widely used for detecting monotonic trends in hydro-meteorological time series. The MK test is particularly effective for determining the presence and direction of a trend, while Sen’s slope quantifies its magnitude. These methods are robust to non-normal data distributions and outliers but assume linear and monotonic trends. More recently, the Innovative Trend Analysis (ITA) method has been applied to detect trends and transitional behavior in hydro-meteorological data [35,38,39,40,41]. TA offers the advantage of distinguishing low, medium, and high data-value trends graphically, complementing traditional MK-based approaches [42,43,44]. Both MK and ITA, however, are sensitive to serial correlation, which may lead to the detection of spurious trends if not properly addressed [45].

In the Vietnamese Mekong Delta (VMD), drought occurrence is shaped not only by climatic variability but also by complex upstream hydrological alterations. The Lower Mekong Basin (LMB) faces intensifying challenges driven by rapid regional development, climate change, and extensive upstream hydropower construction. More than 150 hydropower dams have been built across the Mekong Basin, including 13 on the main channel—eleven in China and two in the Lao PDR, with additional projects across Lancang tributaries [46,47,48,49]. Mega-dams such as Xiaowan and Nuozhadu, commissioned in the early 2010s, have significantly modified Mekong hydrology [50]. Lu et al. (2021) [51] documented substantial shifts in streamflow patterns post-2010, with dry-season flows declining and wet-season flows becoming more volatile. These flow alterations exacerbate both flood and drought risk downstream, affecting ecosystems and livelihoods [51]. Upstream hydropower operations have been shown to intensify drought conditions in the VMD and the LMB more broadly [51,52].

Climate change further compounds these pressures, exposing the region to more frequent and intense flood and drought events [53]. The VMD is particularly vulnerable to sea-level rise, which accelerates salinity intrusion, coastal erosion, and the loss of productive agricultural land [54,55]. Such environmental changes carry deep socio-economic consequences for communities whose livelihoods rely heavily on farming and fisheries.

Despite extensive research, meteorological and hydrological droughts in the LMB are often studied separately, limiting understanding of their interactions and propagation pathways. Furthermore, limited attention has been given to cross-border drought dynamics, including water security [56,57]. Local adaptation strategies and water-management responses also remain under-examined despite the increasing frequency of extreme drought events.

The present study aims to address these gaps by comprehensively assessing the characteristics, trends, and spatio-temporal patterns of meteorological (1992–2021) and hydrological (2000–2021) droughts in the Lower Mekong River Basin. Specifically, it evaluates drought-propagation pathways and investigates how rainfall variability and upstream hydropower development influence river-discharge dynamics across the VMD. To achieve this, the study employs both the SPI and SDI indices to examine upstream rainfall variability and relate these patterns to downstream streamflow conditions. Trend detection is conducted using the MK test, Sen’s slope estimator, and ITA, as well as the Sequential Mann–Kendall (SMK) test. The findings are expected to provide critical evidence to support policy development and enable decision-makers to better evaluate current and future meteorological and hydrological drought risks in the region.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area Description and Data Collection

The VMD constitutes the southernmost part of Vietnam and forms a major portion of the Lower Mekong River Basin (Figure 1). The region covers approximately 39,734 km2, representing 12.2% of Vietnam’s total land area. The VMD provides a wide range of ecosystem services, including provisioning services such as food production and freshwater supply, as well as critical regulating functions, notably flood mitigation through its extensive floodplains and carbon sequestration within peatland ecosystems. It also plays an important supporting role in sediment trapping, which sustains soil fertility and coastal stability [58]. Despite these ecological strengths, the VMD is highly sensitive to environmental change and faces substantial challenges arising from climate change and sea-level rise [54,55,59].

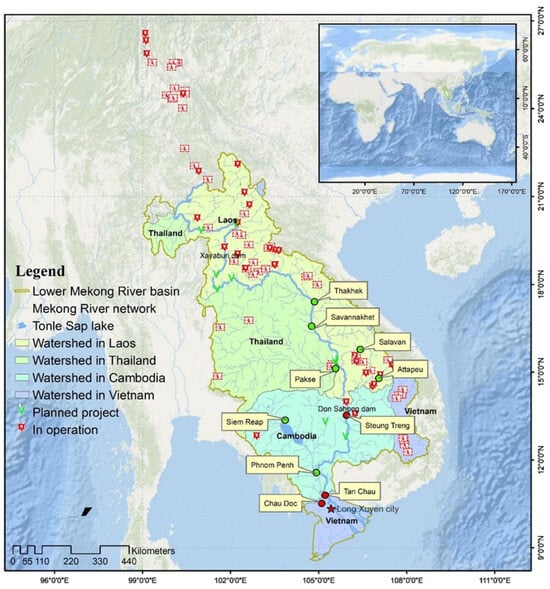

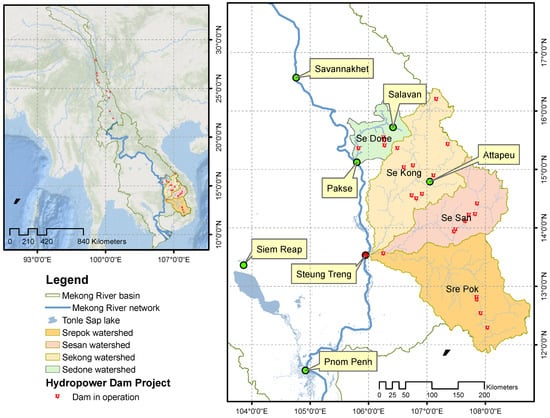

Figure 1.

The Lower Mekong River Basin spans Cambodia, Lao PDR, and Vietnam. This study draws on data from six meteorological stations located in Cambodia and Lao PDR (Thakhek, Savannakhet, Salavan, Pakse, Attapeu, Siem Reap, and Phnom Penh) and three hydrological stations in Vietnam (Stung Treng, Tan Chau, and Chau Doc). Operational hydropower dams are indicated. Red symbols denote river-gauging stations, while green symbols denote meteorological stations. Source: Author’s own work.

Situated within an intertropical monsoon climate zone and characterized by low, flat terrain, the VMD is widely recognized as one of the world’s most climate-vulnerable delta regions [59]. Much of the landscape has been extensively engineered for agricultural production, featuring a dense mosaic of rivers, canals, rice polders, aquaculture ponds, wetland habitats, and irrigation systems. The extensive water-control infrastructure—comprising primarily artificial waterways—is used for transportation, crop irrigation, domestic supply, and water [60,61,62,63,64] storage.

Freshwater and saline-water management in the VMD is supported by a complex system of weirs and sluice gates that regulate flow and salinity intrusion. These structures manage a variety of hydrological functions, including freshwater intake, freshwater–saltwater separation, controlled saline-water entry, and saline-water discharge. Their operation directly shapes land use patterns across the delta, supporting rice and fruit cultivation in freshwater zones while enabling brackish-water and saltwater shrimp aquaculture in coastal and estuarine areas [65,66,67].

Tides and seasonal fluctuations in river discharge during both the wet and dry seasons are the primary drivers shaping the operation of water-management structures, such as weirs and sluice gates, in the VMD. The region is characterized by continuous exchanges between freshwater and saline water, driven by tidal dynamics and seasonal variations in river levels. The Hau River supplies freshwater to extensive agricultural zones, supporting rice cultivation and fruit production, while brackish and saline conditions closer to the coast sustain shrimp farming and other forms of saline aquaculture.

The Mekong River system conveys an estimated annual flow volume of approximately 500 billion cubic meters, with the Tien River (the main branch of the Mekong) contributing around 79% and the Hau River (Bassac River) contributing about 21%. The hydrological regime of the delta is strongly seasonal. During the dry season, reduced river discharge commonly intensifies saltwater intrusion into coastal provinces, increasing pressure on local water supplies. As a result, many areas of the VMD have become increasingly dependent on surface-water storage and groundwater extraction.

Recent land use and land cover trends indicate significant shifts in production systems: aquaculture and residential areas have expanded, while rice-growing areas have declined markedly. These transitions reflect both economic restructuring and the growing influence of salinity intrusion, water scarcity, and environmental change on livelihood strategies across the delta [68].

2.2. SPI and SDI Calculation

2.2.1. Standardized Precipitation Index (SPI)

The meteorological and hydrological drought indices were calculated as follows: SPI, which is only based on rainfall, and SDI have grown in popularity over the last decade because of their low data requirements. Mckee et al. (1993) created the SPI by measuring precipitation [28]. The World Meteorological Organization (WMO) recommends SPI as a drought indicator for drought-prone and arid regions. Refer to Appendix A for details SPI calculation. Positive SPI values imply more than median precipitation, and negative values imply less than median precipitation.

2.2.2. Streamflow Drought Index (SDI)

The Streamflow Drought Index (SDI) was developed by Nalbantis et al. (2009) [69], which was calculated to depict the VMD hydrological drought. Similar to SPI, the SDI was calculated using monthly measured streamflow volumes at various time scales. This index offers a valuable resource for understanding short-, medium-, and long-term hydrological drought conditions and water supply issues in the region. Refer to Appendix B.1 for details SDI calculation. Table 1 provides the criteria for determining the drought index using the SPI and SSI indices. The categorization ranges from Extremely wet (≥2.00) to Extremely dry (≤−2.00).

Table 1.

Classification of the SPI [26] and SDI values [70].

2.3. Mann-Kendal Test and Sen’s Slope

The MK test is an effective trend analysis tool that has been used in several studies to identify trends in hydroclimatic time series [71,72]. The sequential MK test was used to identify significant changes in the data series. The trend will be significant if the Prograde curve does not return to the range after leaving the significant range. A positive trend toward positive values will prevail, while a negative trend toward negative values will prevail. There is no significant trend in the time series if the two mentioned curves collide within the critical range and do not leave the critical range, or there is no intersection, or the curves overlap several times towards the end of the time series [71,73]. Refer to Appendix B.2 and Appendix B.3 for details Mk test and Sen’s slope calculation.

2.4. Innovative Trend Analysis

Innovative Trend Analysis is a method that, unlike most approaches, eliminates several assumptions, including the autonomous structure of the time series, normality of the distribution, and data length, which was conducted to detect trends in various parts of the world [74,75]. ITA was first suggested by Şen in 2012 [42]. The analysis is highly applicable and can be used to confirm the MK test results. Charting was performed between the initial half of the time series on the X-axis and the latter half of the series on the Y-axis. The two portions are plotted on a scatter plot, and the 1:1 line of the plot is calculated. The drought severity can be classified into three levels: low level (), medium level (, and high level , where denotes mean value, and denotes standard deviation [75,76].

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. The Correlation Assessment Between SPIs and SDIs over 12-Month Timescales

Table 2 presents the correlations between the 12-month Standardized Precipitation Index (SPI-12) and the 12-month Streamflow Drought Index (SDI-12) at Tan Chau. Stations located in the middle Mekong region, Thakhek, Savannakhet, and Pakse—exhibited the strongest positive correlations (r = 0.60–0.70), indicating that rainfall variability in this zone exerts a dominant influence on downstream hydrological conditions at Tan Chau. In contrast, tributary stations in southern Lao PDR (Salavan and Attapeu) displayed only weak associations with Tan Chau flow, suggesting a more localized hydrological response and limited downstream propagation of drought signals from these tributaries. Downstream stations in Cambodia (Phnom Penh and Siem Reap) showed moderate to very strong correlations with the 1-year-lagged SDI-12 values at Tan Chau, with Phnom Penh in particular exhibiting a notable correlation of r = 0.71. This relationship points to a more complex hydrological response mechanism because the Mekong Basin possesses natural structures that act as giant hydrological buffers, which consequently slow the response of river flows. For instance, the Tonle Sap Lake plays a crucial role: during the flood season, the Mekong River flows into the lake for storage, and during the dry season, the stored water flows back into the river, sustaining the baseflow further downstream. Similarly, the extensive floodplains throughout the basin contribute by retaining water and slowing the drought’s propagation. Furthermore, the Mekong River is a massive, highly elongated system, spanning approximately 4900 km. Consequently, the travel time required for water to flow from the upstream rainfed areas to the gauging stations in the Mekong Delta is exceptionally long. This means that short-term rainfall deficits are not immediately recorded in the downstream discharge. Instead, a significant time lag occurs because the hydrological system requires a prolonged and cumulative rainfall deficit over a large scale to deplete the vast natural water storage capacity sufficiently to cause a notable reduction in downstream flow.

Table 2.

Correlation between 12-month SPIs (seven meteorological stations) and the 12-month SDIs at Tan Chau hydrological station, 2000–2021.

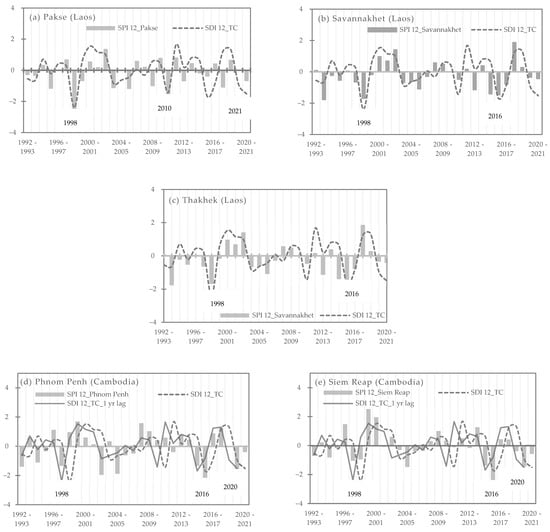

The meteorological drought analysis further identifies Siem Reap and Savannakhet as the stations with the highest frequency of SPI-12 drought events (16 and 17 events, respectively), predominantly falling within the mild drought category (Figure 2). However, in terms of drought intensity, Siem Reap, Phnom Penh, and Thakhek recorded the greatest number of severe-to-extreme drought episodes (five, four, and three events, respectively). Moderate droughts were most common at Pakse and Savannakhet, whereas notable wet spells occurred frequently at Phnom Penh (15 events) and Thakhek (14 events).

Figure 2.

Change of 12-month SDIs at Tan Chau and 12-month SPIs during 1992 and 2021 in the three stations in Lao PDR and the two stations in Cambodia. These are listed as: (a) Pakse station (Lao PDR); (b) Savannakhet station (Lao PDR); (c) Thakhek (Lao PDR); (d) Phnom Penh (Cambodia); (e) Siem Reap (Cambodia).

An important observation concerns the Thakhek station: although it generally shows lower overall drought sensitivity compared with other locations, it experienced distinct extreme meteorological droughts during 1998–1999, 2015–2016 and 2020–2021. These anomalies closely align with major downstream hydrological impacts, corresponding to the extreme hydrological droughts of 1998–1999, 2015–2016 and the severe drought of 2020–2021 observed in the VMD. Similarly, severe meteorological drought periods identified at Phnom Penh (e.g., 2002–2005 and 2019–2020) coincide with episodes of broader regional hydrological stress (Figure 2).

Figure 2 illustrates the 1992–2021 time series comparing 12-month Standardized Precipitation Index (SPI-12) values at five upstream meteorological stations with the 12-month Streamflow Drought Index (SDI-12) at Tan Chau. At the middle Mekong stations in Lao PDR—Pakse (a), Savannakhet (b), and Thakhek (c)—the curves exhibit a strong positive co-movement: SPI-12 and SDI-12 fluctuate largely in phase, reaching comparable wet peaks and declining sharply during the same drought years (e.g., 1998–1999, 2003–2004, 2005–2006, 2011–2012, 2015–2016, and 2020–2021). This synchronicity indicates strong drought-propagation linkages between upstream rainfall variability and downstream hydrological response at Tan Chau.

The analysis further shows that the extreme hydrological drought of 1998–1999 corresponded to a basin-wide meteorological drought of moderate intensity across the five stations, underscoring how upstream rainfall anomalies influence the severity of drought impacts in the VMD. Likewise, the mild hydrological droughts of 2003–2004 and 2005–2006 aligned with mild meteorological drought conditions across the region.

Since 2010, however, a noticeable divergence between meteorological and hydrological drought intensities has emerged. While meteorological droughts generally remained within the moderate category during this period, hydrological droughts intensified markedly—ranging from moderate (2010–2011) to severe (2015–2016 and 2020–2021). This post-2010 decoupling suggests additional drivers of hydrological stress, such as upstream hydropower regulation, altered flow regimes, and increased dry-season water withdrawals, beyond meteorological deficits alone.

This pattern suggests a widening disconnect between meteorological and hydrological drought conditions, pointing to a heightened regional vulnerability to hydrological impacts. Since the early 2000s, hydroelectric dam development has expanded rapidly across the Mekong River Basin, particularly in the upper reaches of China and Lao PDR. Previous studies have documented significant alterations to the river’s sediment and flow regimes associated with these developments. For example, sediment loads at the Gaiju gauging station in the Chinese Mekong were found to decline markedly between 1963 and 2003 following the commissioning of the Manwan Dam in 1993, indicating the influence of upstream impoundment on downstream sediment and discharge dynamics [77,78]. Table 3 shows that the number of dams in the Mekong Basin has increased substantially since 2003. According to the [79] of the Mekong Futures Institute, there are currently more than 150 hydropower dams in the entire Mekong River basin. On the mainstream alone, 12 large dams were completed in the period 2000–2023, of which 11 dams are located in China and 2 dams in Lao PDR. This extensive development is consequently accompanied by a considerable expansion in the total water-storage capacity across the basin, significantly altering the natural flow regime [80,81]. For example, the Jinghong Hydropower Dam commenced operation in 2009, followed by the Xayaburi Dam in 2019 and the Don Sahong Dam in 2020. Research results found that the average annual flow at Chau Doc station (2000–2021) decreased by 18%, 31% and 38% in 2010, 2015 and 2020, respectively. Similarity, the average annual flow at Tan Chau station (2000–2021) decreased by 18%, 21% and 19% in 2010, 2015 and 2020, respectively. The continued expansion of hydropower infrastructure is likely to intensify drought conditions in the Lower Mekong Basin by further regulating dry-season flows, reducing downstream discharge, and amplifying the basin’s sensitivity to rainfall deficits [51,82]. A study by [83] observed that discharge and water levels at some gauging stations in Lao PDR, including Chiang Saen, Luang Prabang, Mukdahan, Pakse, and Stung Treng, exhibited inverse seasonal trends, rising during the dry season and falling during the wet season. This study has not yet definitively quantified the extent of flow and water level fluctuations within the VMD.

Table 3.

Summary of dams on the Mekong mainstream in operation from 2000 to 2021.

In contrast, at the downstream Cambodian stations such as Phnom Penh (d) and Siem Reap (e), the synchrony between rainfall variability and contemporaneous streamflow at Tan Chau is relatively weak. However, when a one-year lag in streamflow is considered, the correlations become substantially stronger. In these cases, major rainfall peaks in Cambodia frequently align with the lagged SDI-12 peaks at Tan Chau, indicating that rainfall contributions from this region influence downstream hydrology with a delayed response. This delay is consistent with the buffering and release dynamics of the Tonle Sap system.

The time series also reveals a marked divergence between meteorological and hydrological behavior in the more recent period (post-2010). While SPI-12 generally indicates only moderate meteorological drought conditions, SDI-12 values show a pronounced intensification of hydrological drought. This decoupling suggests that streamflow is increasingly governed by non-meteorological drivers, most notably upstream hydropower regulation, altered flow timing, and enhanced water withdrawals, rather than rainfall variability alone.

3.2. Meteorological and Hydrological Analysis

3.2.1. Temporal Analysis of 12-Month SPIs

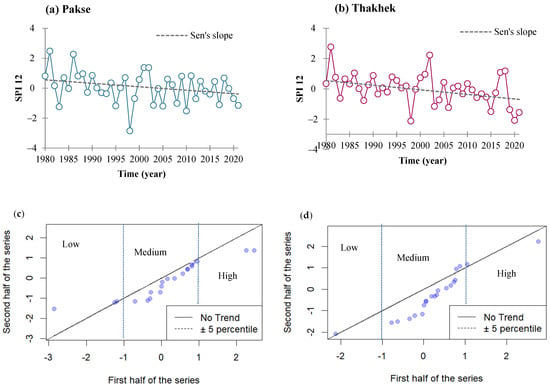

Using the MK test, the 12-month SPI values reveal declining rainfall trends at six stations: Pakse, Thakhek, Attapeu, Savannakhet, Phnom Penh, and Siem Reap. Among these, Pakse and Thakhek exhibit statistically significant decreasing trends at the 95% confidence level (Figure 3). In contrast, the Salavan station shows a slight increasing trend in rainfall, although this trend is not statistically significant. The rate of decline is steeper at Thakhek than at Pakse, with Sen’s slope estimates of −0.58 decade−1 and −0.23 decade−1, respectively.

Figure 3.

Trend Analysis of SPI-12 (1992–2021) using the MK Test and ITA Method at Thakhek and Pakse Stations. Subplots (a,b) present the results of the MK Test, and subplots (c,d) present the results of the ITA method. Results for Thakhek are shown in (a,c), and results for Pakse are shown in (b,d).

To further examine temporal trend characteristics, the Innovative Trend Analysis (ITA) method was applied at both Pakse and Thakhek. As shown in Figure 3c,d, most data points lie below the 1:1 line, indicating an overall downward tendency across the record. The dominant negative trend appears within the “Medium” to “High” value ranges, suggesting that decreases in rainfall are most pronounced during periods that historically exhibited moderate to high precipitation.

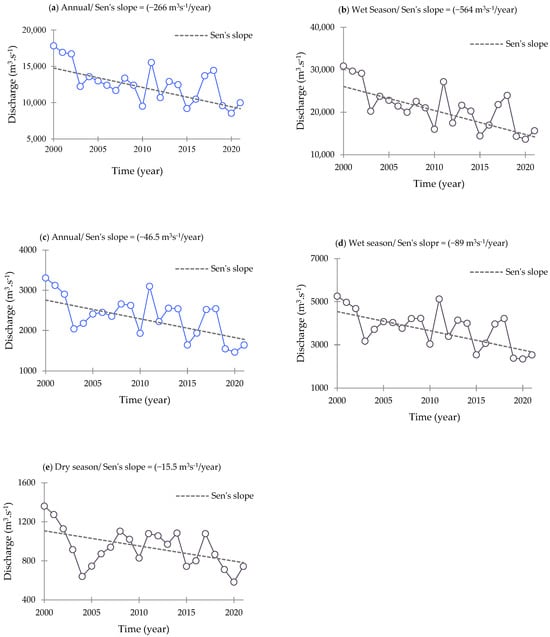

3.2.2. Temporal Analysis of River Discharge

Using the MK test combined with Sen’s slope estimation, a statistically significant decreasing trend in both annual and wet-season discharges was detected at the Stung Treng and Chau Doc stations at the 95% confidence level (Figure 3). Although Tan Chau displayed a similar downward tendency, the trend was not statistically significant. Sen’s slope analysis revealed much steeper declines at Stung Treng, where annual and wet-season discharges decreased by −266 m3 s−1 year−1 and −564 m3 s−1 year−1, respectively, compared with Chau Doc (−46.5 m3 s−1 year−1 and −89 m3 s−1 year−1). Correspondingly, percentage decreases at Stung Treng (−2.1% year−1 for annual discharge and −2.7% year−1 for wet-season discharge) exceeded those observed at Chau Doc (−2% year−1 and −2.4% year−1). A statistically significant declining trend in dry-season discharge was also found at Chau Doc (−1.7 m3 s−1 year−1), whereas Stung Treng exhibited a non-significant increasing trend during the same period.

To further assess spatial changes in downstream flow distribution, we computed two ratios: R1, defined as discharge at Chau Doc divided by discharge at Tan Chau, and R2, defined as discharge at Chau Doc divided by the combined discharge at Chau Doc and Tan Chau (Table 4). Both R1 and R2 exhibited statistically significant declines across all time scales except in February. Reductions in R1 were more pronounced during the dry season (−1.7% year−1) than during the rainy season (−1.5% year−1). The steepest declines occurred in December, November, and October (−2.1%, −1.8%, and −1.7% year−1, respectively), indicating substantial reductions in flow through Chau Doc at the end of the flood season and the onset of the dry season. Overall, R1 declined at a rate of −1.6% year−1, equivalent to an approximately 16% reduction in annual flow at Chau Doc relative to Tan Chau over a decade, with the dry season showing the greatest losses.

Table 4.

Descriptive statistics and trend analysis for R1 and R2 using the MK test.

A similar pattern emerged for R2, which also showed statistically significant declines across all time scales except February. Dry-season reductions (−1.47% year−1) exceeded rainy-season reductions (−1.15% year−1), resulting in an annual R2 decline of −1.26% year−1. The most pronounced decreases occurred in December, November, and January (−1.7%, −1.44%, and −1.41% year−1, respectively). These findings indicate declining flows not only at Chau Doc but also at Tan Chau, with the largest losses occurring at Tan Chau in the early dry-season months.

The consistent reduction in water levels throughout the year—particularly during the critical dry season—poses substantial risks for maintaining essential environmental flows in the lower Mekong River. The disproportionately sharp decline in discharge at Chau Doc relative to Tan Chau especially concerns in the broader context of declining flows into the Mekong Delta and underscores the basin’s increasing hydrological vulnerability.

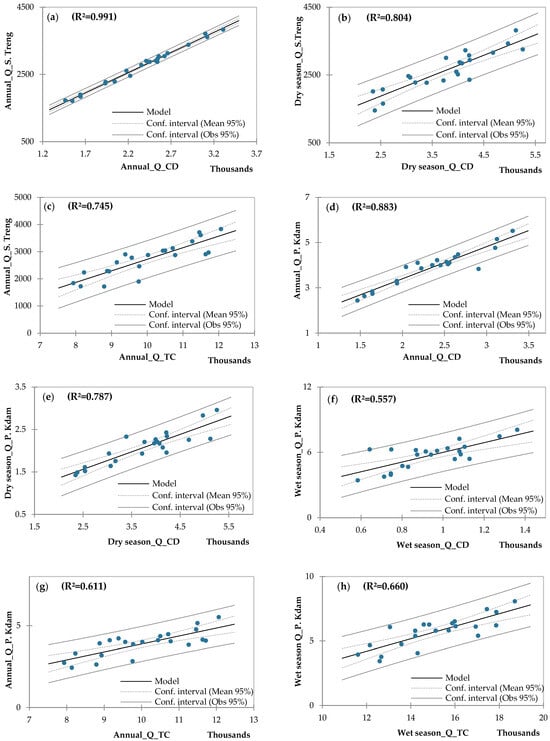

3.2.3. Discharge Correlation Analysis Between Stung Treng and Prek Kdam (Cambodia) with Chau Doc and Tan Chau (Vietnam)

We conducted a monthly discharge correlation analysis between Stung Treng and the downstream stations at Chau Doc and Tan Chau (Figure 4). The results reveal a very strong relationship between discharges at Stung Treng and Chau Doc, with coefficients of determination of R2 = 0.99 for annual discharge and R2 = 0.80 for dry-season discharge. Similarly, strong correlations were observed between Stung Treng and Tan Chau, with R2 = 0.75 for dry-season discharge and r = 0.56 for annual (or wet-season) discharge.

Figure 4.

MK test results for annual, wet, and dry season discharge trends at Stung Treng and Chau Doc. Subplots (a) and (b) present the annual and wet season trends for Stung Treng, respectively. Subplots (c), (d), and (e) present the annual, wet season, and dry season trends for Chau Doc, respectively.

While dry-season discharge correlations between Stung Treng and Chau Doc were stronger than those between Stung Treng and Tan Chau, wet-season discharge at Chau Doc exhibited only a weak association with Stung Treng (R2 = 0.17) (Figure 5a–c). This weak linkage emphasizes the impact of other factors—including floodplain storage, Tonle Sap dynamics, and local water-management interventions—on downstream hydrology during the wet season. Overall, the observed correlation patterns underscore the complex temporal and spatial variability of Mekong River flows and the multiple processes shaping downstream discharge behavior.

Figure 5.

Discharge correlation between Chau Doc and Stung Treng (a,b) Tan Chau and Stung Treng (c). Discharge correlation between Chau Doc and Prek Kdam (d–f), Tan Chau and Prek Kdam (g,h). Discharge in cubic meters.

A recent study revealed a significant decrease in the magnitude of annual peak floods at all discharge gauging stations within the Lower Mekong Basin [84]. The magnitude of annual peak discharges exhibited significant declines across the Mekong Basin between the 1900s and 2000s, ranging from a 12% reduction at Pakse to a 47% decrease at Chiang Saen. Previous research has demonstrated that altered rainfall patterns and the proliferation of dams within the Mekong Basin have significantly impacted the variability of river discharge in the lower reaches [84,85,86,87,88,89]. Discharge trends were also analyzed at Prek Kdam, the confluence of the Mekong River and Tonle Sap Lake, where a remarkable seasonal flow reversal occurs. In the wet season, rising Mekong River waters reverse the flow of the Tonle Sap River. Conversely, during the dry season, the Tonle Sap River flows southward, connecting the lake to the Mekong. Our analysis of flow data at Prek Kdam revealed a significant decline in average flow during both the wet and dry seasons between 2000 and 2021. The annual percentage change was −2.17% for the wet season and −2.11% for the dry season, indicating a similar rate of decline in both periods. A strong correlation was observed between Chau Doc and Prek Kdam during the annual (R2 = 0.88) while a moderate correlation (R2 = 0.78) was found during the dry season (R2 = 0.79) and wet season (R2 = 0.56). Tan Chau exhibited a moderate correlation with Prek Kdam during the annual season (R2 = 0.61) and during the wet season (R2 = 0.66) (Figure 5d–h).

The analysis at Stung Treng and Prek Kdam (the crucial confluence point of the Mekong and Tonle Sap), highlights a concerning trend of declining flow during both the wet and dry seasons between 2000 and 2021. This consistent decline across both hydrological regimes suggests a significant and potentially impactful alteration to the natural flow dynamics of this vital ecosystem. The strong correlation between Stung Treng and Prek Kdam with Chau Doc during the wet season emphasizes the interconnectedness of these river systems and the potential for upstream influences to impact downstream flow.

It should be noted that dry season flows at Chau Doc are primarily influenced by the variations in flow at Prek Kdam, whereas dry season flows at Tan Chau depend primarily on flow fluctuations at Stung Treng. The analysis at Stung Treng and Prek Kdam (the crucial confluence point of the Mekong and Tonle Sap), highlights a concerning trend of declining flow during both the wet and dry seasons between 2000 and 2021. This consistent decline across both hydrological regimes suggests a significant and potentially impactful alteration to the natural flow dynamics of this vital ecosystem. The strong correlation between Stung Treng and Prek Kdam with Chau Doc during the wet season emphasizes the interconnectedness of these river systems and the potential for upstream influences to impact downstream flow.

3.2.4. Factors Influencing Water Flow Fluctuations in the VMD

The analysis of discharge ratios (R1 and R2) at the Chau Doc gauging station reveals a concerning long-term decline in relative flow compared with Tan Chau. This reduction is most pronounced during the dry season, signaling heightened water stress during the period of greatest agricultural and domestic demand. The estimated 16% decrease in average annual flow over a single decade underscores the severity of these hydrological shifts and their potential long-term implications for the Chau Doc sub-basin. Such reductions have significant ramifications for water-resource management, including water allocation, irrigation scheduling, and growing risks of future water scarcity.

At Chau Doc, river discharge has decreased across both the wet season and the annual series, while Tan Chau also exhibits declining discharge, though not at a statistically significant level. These patterns suggest evolving upstream controls on flow distribution between the two distributaries of the Mekong. Notably, geomorphological changes near Phnom Penh, where the Bassac River branches off from the Mekong at the confluence with the Tonle Sap River, show that the Bassac’s entrance channel is narrowing and shifting southeastward. Such changes may be altering flow partitioning between the two branches, contributing to reduced volumes entering the Bassac system and subsequently the Chau Doc reach [90,91]. According to [92], the flow of the VMD is impacted by upstream flow. Kratie gauging station on the Mekong River and the Prek Kdam gauging station on the Tonle Sap Lake system are the two key gateway stations that regulate and monitor the amount of water entering the VMD. The Phnom Penh hydrological gauging on the Mekong River combines the flow between Kratie and the water regulation mechanism of Tonle Sap Lake. The minimum annual river discharge is lowered by an average of 20% per year at Tan Chau and Chau Doc gauging stations, while the average monthly maximum water level has reduced by 30% at the Tan Chau and Chau Doc gauging stations.

Fluctuations in rainfall at gauging stations along the mainstream of the Mekong River in Lao PDR show a strong correlation with changes in river discharge in the lower Mekong region of Vietnam. This pattern indicates a robust linkage between upstream precipitation dynamics and downstream hydrological behavior. Rainfall is the dominant driver of flow in the Mekong River system, with the strong southwest monsoon delivering intense precipitation during the wet season. During this period (March–September), contributions from Lao PDR, Thailand, and Cambodia make up approximately 75% of the total Mekong discharge. In contrast, China’s contribution to the mainstream flow is relatively modest—typically between 10% and 15% during the wet season—but increases to around 25% during the winter months, when runoff from upstream reservoirs and snow-fed tributaries becomes more influential [93].

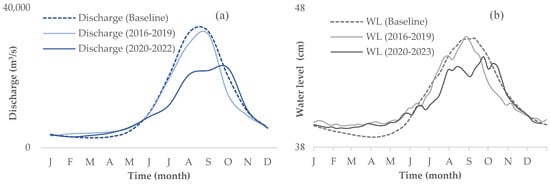

Several hydropower dams were also identified within the Sedon and the 3S sub-basins, comprising the Sekong, Sesan, and Srepok river systems (Figure 6). Figure 7 illustrates changes in river discharge and water level at the Stung Treng station relative to long-term baseline conditions. This comparison provides important insights into deviations from typical hydrological patterns in the region. Between 2016 and 2019, peak discharges were consistently lower than the baseline, and the timing of the peak shifted later in the season. The decline intensified between 2020 and 2022, when peak discharge dropped by approximately 30% relative to the baseline, with peak timing delayed by about one month. A similar delay in peak water level is observed from 2020 to 2023, during which peak water levels occurred roughly one month later than normal. Overall, peak water levels at Stung Treng decreased by around 3% during 2020–2023 compared with baseline conditions.

Figure 6.

Existing dams in the Sedon, Sekong, Sesan, and Srepok watersheds, as well as along the upper Mekong River (Lancang). Source: Author’s own work.

Figure 7.

Changes in discharge (a) and water level (b) relative to baseline discharge and water level at Stung Treng station.

Our results suggest further studies are needed to evaluate the impact of hydropower dams in tributaries of the Mekong River on the changing river discharge volumes in the downstream VMD. Furthermore, the monthly, seasonal, and annual discharge values recorded at Chau Doc declined dramatically in the wet season with a 95% statistical significance. In contrast, dry season flow showed a slight increase that was not statistically significant. Our results also agree with those of the study by [94], who revealed that the effects of hydropower development in the upper Mekong River on the flow of the Mekong River system has altered dramatically since 2010 [62,84]. However, some studies also discovered that there has been a trend of decreasing flood peaks and shortening flood season duration since 2000 [90,91]. Similarly, many results have suggested that increasing the full dike system in the upper VMD influences the discharge fluctuations at Chau Doc and Tan Chau stations [36,95]. Another study found that the mean annual water level at Tan Chau gauging declined by 3.5% per year, while the Hmax at Chau Doc decreased by 3–5% per year [96]. Numerous studies also show that ENSO influences flow changes in the VMD [97].

Despite the above findings, detailed insights remain limited due to the scarcity of data from key tributaries and the incomplete documentation of seasonal discharge fluctuations. Consequently, this study highlights the need for future research that can more comprehensively assess the influence of hydropower development in Mekong tributaries on downstream discharge dynamics in the VMD. In addition, conducting uncertainty analyzes and applying appropriate bias-correction techniques will require longer-term, high-quality datasets across multiple hydro-meteorological variables to ensure robust evaluation and greater confidence in future assessments.

4. Conclusions and Recommendations

This study is subject to several important limitations that should be acknowledged. A primary constraint is the availability of long-term, high-resolution hydro-meteorological data, particularly from remote regions of the Lower Mekong Basin, where datasets are often inconsistent, incomplete, or discontinuous. Cross-border data sharing remains challenging due to differing national standards for monitoring, data collection, and water-management practices. As a result, the analysis may not fully capture tributary influences or local-scale hydrological variability.

The spatial resolution of the available datasets may also obscure localized drought events and small-scale fluctuations, potentially oversimplifying drought dynamics. Temporal limitations are another concern; shorter time series may not adequately reflect long-term hydro-climatic cycles, including El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO) and other decadal climate oscillations. Furthermore, the complexity of transboundary impacts, combined with differing national water priorities, constrains the extent to which comprehensive basin-wide conclusions can be drawn.

The study focuses primarily on physical drought indicators, leaving socio-economic dimensions, such as agricultural vulnerability, livelihood impacts, and institutional responses, less explored. Finally, uncertainties in climate projections and limited assessment of existing adaptation and water-management strategies restrict the ability to fully anticipate future drought risks. Addressing these limitations in future research will considerably strengthen basin-wide drought assessment and management.

Despite these limitations, the study provides several important insights into the evolving hydrology of the Mekong River Basin. Analysis of hydro-meteorological dynamics in the Lower Mekong River Basin reveals several critical trends from 2000 to 2021. Firstly, there is an observed increase in the frequency and intensity of meteorological droughts (SPI) across the upper and middle reaches, particularly in Cambodia and Lao PDR, with stations like Siem Reap and Savannakhet exhibiting the highest drought frequency. Secondly, trend analysis confirms a statistically significant decrease in annual and wet season river discharges at the upstream stations of the VMD, such as Stung Treng and Chau Doc, marked notably by a decline in flood peaks. This study also confirmed a strong positive correlation (r = 0.60–0.70) between rainfall variability at middle stations (Thakhek, Savannakhet) and subsequent streamflow at Tan Chau station (VMD), underscoring the vital role of upstream rainfall in controlling downstream flows. Most significantly, the results indicate a trend toward increasingly severe hydrological droughts (SDI) compared to meteorological droughts. This critical disconnection strongly suggests that the significant impacts of non-climatic factors, specifically the operations of upstream hydropower facilities, have altered the natural hydrological regime and exacerbated water scarcity conditions in the VMD.

These findings furnish the critical scientific evidence necessary for a comprehensive reassessment of drought risk in the region. Policymakers must now view drought risk in the VMD not merely as a meteorological phenomenon but fundamentally as a hydrological challenge largely governed by large-scale basin water management strategies. The established flow correlations and drought trends can be immediately incorporated into regional forecasting and early warning systems. This integration is crucial for optimizing, particularly during the critical dry season, water resource management and regulation protocols for the VMD, thereby enhancing the region’s ability to proactively manage and mitigate the impacts of water scarcity.

The findings provide important scientific evidence, thus necessitating a comprehensive reassessment of drought risk in the region. Policymakers must view drought risk in the VMD not as a purely meteorological phenomenon, but as a fundamentally hydrological challenge driven by large-scale water management strategies in the basin, particularly upstream hydropower regulation. This requires the immediate integration of established flow correlations and drought trends into regional forecasting and early warning systems. Such integration is crucial for the VMD to optimize water resource management and regulatory processes, especially during the dry season, thereby enhancing the ability to proactively manage and mitigate the impacts of water scarcity, ensuring food security and livelihoods for millions of people in the context of hydrological changes that threaten agriculture, fisheries and ecological stability. To address this hydrological challenge, policy must prioritize transboundary cooperation through the establishment of a common drought early warning mechanism. This system should integrate meteorological (SPI-12) and hydrological (SDI-12) indicators simultaneously, proactively using data from key midstream stations as leading indicators of downstream drought propagation. Furthermore, diplomatic efforts must promote regional dialogue to achieve unified, binding dam operating rules among riparian countries. These rules are essential for regulating upstream flows and must prioritize the clear maintenance of environmental flows necessary for the VMD during the dry season to directly mitigate the impacts of non-meteorological factors.

On the domestic front, water management and land use planning for the VMD must adjust strategically to account for the one-year hydrological lag associated with the Tonle Sap Lake’s regulatory role. This requires that agricultural production planning and water resource allocation for the next dry season be based on the rainfall signal observed in the upstream basin. In addition, future water management planning needs to be supported by long-term scientific datasets and improved cross-border data sharing. Hydrological drought research, which remains underdeveloped compared to flood research in the basin, needs to be enhanced, along with regular monitoring of key variables such as sediment flows and land use change at both spatial and temporal scales.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.T.H.N., N.K.D., H.V.T.M. and P.K.; methodology, D.T.H.N., N.P.C., N.K.D. and P.K.; software, B.T.B.L., N.V.T. and N.T.T.; writing—original draft preparation, D.T.H.N., N.P.C., N.K.D. and P.K.; writing—review and editing, D.T.H.N., N.K.D. and H.V.T.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The authors will provide the data upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of Kien Giang University and Can Tho University. We also thank the reviewers for their helpful suggestions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Standardized Precipitation Index (SPI) Estimation

Equation (A1) shows how to calculate the density probability of the Gamma distribution function [28]. The gamma distribution accommodates only positive and zero values, and the long-term precipitation data series was adapted with a gamma distribution, which was then changed into a normal distribution using an equal probability transformation [98].

The transformation of probability into a normal distribution is shown in Equation (A1).

where α > 0 denotes the shape parameter, β > 0 denotes the scale parameter, denotes s the amount of precipitation, and the gamma function Γ(α) can be expressed in Equation (A2).

by using the Thom approximation Equation (A3)

where for n observations,

G(x) was calculated by integrating the density of the probability function g(x) regarding x. The amount of rain accumulated for a month or specific timescale is thus known Equation (A4)

Given the gamma function’s limitation of not being defined by x = 0 and the potential of zero precipitation, the cumulative probability is stated in Equation (A5).

where q represents the probability of no rain. The SPI was then calculated by converting the cumulative probability into a normal standardized distribution with a null average and unit variance Equations (A6) and (A7).

where c0 = 2.515517, c1 = 0.802853, c2 = 0.010328; d0 = 1.432788, d1 = 0.189269, d2 = 0.001308.

Appendix B

Appendix B.1. Streamflow Drought Index (SDI) Estimation

Considering Streamflow volume , for the i hydrological year and j month within the hydrological year (j = 1 for October and j = 12 for September), then the cumulative Streamflow volume, , and the related SDI are expressed as Equation (A8).

where ; ; Considering cumulative Streamflow volumes, the SDI is calculated for each reference period k of the i-th hydrological year, as shown in Equation (A9).

where is the volume of cumulative streamflow for the i-th hydrological year ( and the k-th reference period, k = 1 for October–December, k = 2 for October–March, k = 3 for October–June, and k = 4 for October–September. is the mean of cumulative streamflow volumes; is the standard deviation of cumulative streamflow volumes. Time scales of 12-month was considered. After that, SDI was categorized under the criteria in Table 1.

Stream flow in limited basins may have an uneven probability distribution, which the Gamma distribution function family can accurately model. The distribution is then normalized. We employed the two-parameter log-normal distribution in this work. Taking the natural logarithms of Streamflow, the SDI is defined as Equation (A10).

where ; ; ; .

The natural logarithms of cumulative streamflow with mean and standard deviation as these statistics are estimated over a long period.

Appendix B.2. Mann–Kendall Test

The MK test [23,24] was employed to analyze trends in monthly discharge and salinity. Being a non-parametric test, it does not require the data follow to a normal distribution, rendering it advantageous for datasets where normality is not expected to. The MK test is commonly employed to assess the significance of trends in hydrometeorological time series [23,86]. The MK test statistic (S) is computed as demonstrated in Equation (A11).

Here, represent sequential data values in a time series, where j > i. The variable n denotes the total length of the time series, and is the sign function, defined in Equation (A12).

Mann (1945) and Kendall (1975) [23,24,99] stated that when n ≥ 10, is almost normally distributed with the following mean and variance as shown in Equations (A13) and (A14)

The value of near zero, positive and negative implies no significant, upward, and downward trends, respectively. The magnitude of measures the strength of the trend. Note that if the absolute value of is greater than the critical value of indicates that trends are statistically significant.

where is the number of ties of the extent i denotes the number of observations in the set and m denotes number of tied groups. The standard statistic is calculated as shown in Equation (A15).

Positive values of indicates increasing trends while negative values of indicates decreasing trends. . The null hypothesis is rejected, and a significant trend exists in the time series. is obtained from the standard normal distribution table. The null hypothesis of no trend is rejected 1% significance level and if || > 1.96 and rejected if || > 2.576 at the 1% significance level.

Statistical significance for trend detection was evaluated at the 95% confidence level (p < 0.05), which is standard in hydrological and environmental time series analysis [23,24,100]. In instances where trends approached this threshold, we also reported findings at 90% and 99% confidence intervals to support comparative assessment. All corresponding p-values and Sen’s slopes are reported in the results tables, allowing transparent interpretation of trend strength and direction.

Appendix B.3. Sen’s Slope Estimation

Sen (1968) [25] developed the non-parametric procedure for estimating the slope of trend in the sample of N pairs of data could be calculated in Equation (A16).

where and are values at time j and k (1 < k < j < n), n is the number of data. The median of these n values of is represented as Sen’s estimator of slope. The positive and negative values of indicate the upward and downward trends in the time series, respectively.

If there is only one datum in each time period, then ; where n is the number of time periods. If there are multiple observations in one or more time periods, then .

The N values of are ranked from smallest to largest and the median of slope or Sen’s slope estimator is computed as shown in Equation (A17).

The sign reflects data trend reflection, while its value indicates the steepness of the trend. To determine whether the median slope is statistically different than zero, one should obtain the confidence interval of at specific probability.

The confidence interval about the time slope [100,101] can be computed as shown in Equation (A18).

where is obtained from the standard normal distribution table. In this study, the confidence interval was computed at two significance levels . If are calculated then the lower and upper limits of the confidence interval, are the largest and the largest of the N ordered slope estimates [100,101]. It should be notes that the slope is statistically different than zero if the two limits () have similar sign.

References

- Hellegers, P.; Zilberman, D.; Steduto, P.; McCornick, P. Interactions between Water, Energy, Food and Environment: Evolving Perspectives and Policy Issues. Water Policy 2008, 10, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasul, G. Food, Water, and Energy Security in South Asia: A Nexus Perspective from the Hindu Kush Himalayan Region. Environ. Sci. Policy 2014, 39, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gleick, P.H.; Cooley, H. Freshwater Scarcity. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2021, 46, 319–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandari, S.; Pasupuleti, R.S.; Samaddar, S. Cultural Systems in Water Management for Disaster Risk Reduction: The Case of the Ladakh Region. IDRiM J. 2022, 11, 28–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Dasgupta, R.; Avtar, R. Socio-Hydrology: A Holistic Approach to Water-Human Nexus in Large Riverine Islands of India, Bangladesh and Vietnam. In Riverine Systems: Understanding the Hydrological, Hydrosocial and Hydro-Heritage Dynamics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 253–265. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Rome 2018, 403. Available online: http://faostat.fao.org (accessed on 22 June 2022).

- Minh, H.V.T.; Van Ty, T.; Avtar, R.; Kumar, P.; Le, K.N.; Ngan, N.V.C.; Khanh, L.H.; Nguyen, N.C.; Downes, N.K. Implications of Climate Change and Drought on Water Requirements in a Semi-Mountainous Region of the Vietnamese Mekong Delta. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2022, 194, 766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO UN. World Water Development Report 2020—Water and Climate Change; UNESCO UN: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Seneviratne, S.I.; Zhang, X.; Adnan, M.; Badi, W.; Dereczynski, C.; Di Luca, A.; Ghosh, S.; Iskander, I.; Kossin, J.; Lewis, S. Weather and Climate Extreme Events in a Changing Climate; University of Reading: Reading, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Tabari, H.; Wang, J.; Wang, Q.; Song, S.; Hu, Z. Innovative Trend Analysis of Annual and Seasonal Rainfall in the Yangtze River Delta, Eastern China. Atmos. Res. 2020, 231, 104673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charak, A.; Ravi, K.; Verma, A. Review of Various Climate Change Exacerbated Natural Hazards in India and Consequential Socioeconomic Vulnerabilities. IDRiM J. 2024, 13, 142–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eltahir, E.A.; Bras, R.L. Precipitation Recycling. Rev. Geophys. 1996, 34, 367–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markonis, Y.; Papalexiou, S.; Martinkova, M.; Hanel, M. Assessment of Water Cycle Intensification over Land Using a Multisource Global Gridded Precipitation Dataset. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2019, 124, 11175–11187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Chen, J.; Chen, X.; Wang, Y. Variability of Precipitation Extremes and Dryness/Wetness over the Southeast Coastal Region of China, 1960–2014. Int. J. Climatol. 2017, 37, 4656–4669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, V.; Nikam, B.R.; Thakur, P.K.; Aggarwal, S.P.; Gupta, P.K.; Srivastav, S.K. Human-Induced Land Use Land Cover Change and Its Impact on Hydrology. HydroResearch 2019, 1, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Liu, H.; Chen, X.; Qiao, Y. Analysis on Impacts of Hydro-Climatic Changes and Human Activities on Available Water Changes in Central Asia. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 737, 139779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathian, F.; Morid, S.; Kahya, E. Identification of Trends in Hydrological and Climatic Variables in Urmia Lake Basin, Iran. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2015, 119, 443–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahid, M.; Rahman, K.U. Identifying the Annual and Seasonal Trends of Hydrological and Climatic Variables in the Indus Basin Pakistan. Asia-Pac. J. Atmos. Sci. 2021, 57, 191–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minh, H.V.T.; Kumar, P.; Van Toan, N.; Nguyen, P.C.; Van Ty, T.; Lavane, K.; Tam, N.T.; Downes, N.K. Deciphering the Relationship between Meteorological and Hydrological Drought in Ben Tre Province, Vietnam. Nat. Hazards 2024, 120, 5869–5894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, A. Drought under Global Warming: A Review. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Change 2011, 2, 45–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tallaksen, L.M.; Van Lanen, H.A. Hydrological Drought. Process. Estim. Methods Streamflow Groundw. 2004, 579. [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty, S.; Pandey, R.; Chaube, U.; Mishra, S. Trend and Variability Analysis of Rainfall Series at Seonath River Basin, Chhattisgarh (India). Int. J. Appl. Sci. Eng. Res. 2013, 2, 425–434. [Google Scholar]

- Kendall, M. Rank Correlation Methods, 4th ed.; Charles Griffin: London, UK, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Mann, H.B. Nonparametric Tests against Trend. Econom. J. Econom. Soc. 1945, 13, 245–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, P.K. Estimates of the Regression Coefficient Based on Kendall′s Tau. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1968, 63, 1379–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edossa, D.C.; Babel, M.S.; Das Gupta, A. Drought Analysis in the Awash River Basin, Ethiopia. Water Resour. Manag. 2010, 24, 1441–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsakiris, G.; Pangalou, D.; Vangelis, H. Regional Drought Assessment Based on the Reconnaissance Drought Index (RDI). Water Resour. Manag. 2007, 21, 821–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKee, T.B.; Doesken, N.J.; Kleist, J. The Relationship of Drought Frequency and Duration to Time Scales; American Meteorological Society (AMS): Boston, MA, USA, 1993; Volume 17, pp. 179–183. [Google Scholar]

- Salimi, H.; Asadi, E.; Darbandi, S. Meteorological and Hydrological Drought Monitoring Using Several Drought Indices. Appl. Water Sci. 2021, 11, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viola, M.R.; Amorim, J.d.S.; de Mello, C.R. Hydrological Response to Drought Occurrences in a Brazilian Savanna Basin. Resources 2020, 9, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pai, D.; Sridhar, L.; Guhathakurta, P.; Hatwar, H. District-Wide Drought Climatology of the Southwest Monsoon Season over India Based on Standardized Precipitation Index (SPI). Nat. Hazards 2011, 59, 1797–1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolova, N.; Radeva, K. Data Processing for Assessment of Meteorological and Hydrological Drought; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 145–160. [Google Scholar]

- Minh, H.V.T.; Kumar, P.; Van Ty, T.; Duy, D.V.; Han, T.G.; Lavane, K.; Avtar, R. Understanding Dry and Wet Conditions in the Vietnamese Mekong Delta Using Multiple Drought Indices: A Case Study in Ca Mau Province. Hydrology 2022, 9, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Zhu, Y.; Xu, R.; Liu, J. Drought Severity Change in China during 1961–2012 Indicated by SPI and SPEI. Nat. Hazards 2015, 75, 2437–2451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alifujiang, Y.; Abuduwaili, J.; Ge, Y. Trend Analysis of Annual and Seasonal River Runoff by Using Innovative Trend Analysis with Significant Test. Water 2021, 13, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Ty, T.; Minh, H.V.T.; Avtar, R.; Kumar, P.; Van Hiep, H.; Kurasaki, M. Spatiotemporal Variations in Groundwater Levels and the Impact on Land Subsidence in CanTho, Vietnam. Groundw. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 15, 100680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuan, N.V.; Giang, N.N.L.; Ty, T.V.; Kumar, P.; Downes, N.K.; Nam, N.D.G.; Ngan, N.V.C.; Thinh, L.V.; Duy, D.V.; Avtar, R. Impacts of Dike Systems on Hydrological Regime in Vietnamese Mekong Delta. Water Supply 2022, 22, 7945–7959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kisi, O.; Ay, M. Comparison of Mann–Kendall and Innovative Trend Method for Water Quality Parameters of the Kizilirmak River, Turkey. J. Hydrol. 2014, 513, 362–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, A.; Kumar, A.; Guhathakurta, P.; Kisi, O. Spatial-Temporal Trend Analysis of Seasonal and Annual Rainfall (1966–2015) Using Innovative Trend Analysis Method with Significance Test. Arab. J. Geosci. 2019, 12, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şen, Z. Innovative Trend Analysis Methodology. J. Hydrol. Eng. 2012, 17, 1042–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, Y.; Mishra, A.; Sarangi, A.; Singh, D.; Sahoo, R.; Sarkar, S. Trend Analysis of Rainfall and Runoff in the Jhelum Basin of Kashmir Valley. Indian J. Agric. Sci. 2018, 88, 320–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caloiero, T.; Coscarelli, R.; Ferrari, E. Application of the Innovative Trend Analysis Method for the Trend Analysis of Rainfall Anomalies in Southern Italy. Water Resour. Manag. 2018, 32, 4971–4983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, R.O.; Abubaker, S.R. Trend Analysis Using Mann-Kendall, Sen′s Slope Estimator Test and Innovative Trend Analysis Method in Yangtze River Basin, China. Int. J. Eng. Technol. 2019, 8, 110–119. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, R.; Kuriqi, A.; Abubaker, S.; Kisi, O. Long-Term Trends and Seasonality Detection of the Observed Flow in Yangtze River Using Mann-Kendall and Sen′s Innovative Trend Method. Water 2019, 11, 1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şen, Z. Innovative Trend Significance Test and Applications. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2017, 127, 939–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baird, I.G.; Hogan, Z.S. Hydropower Dam Development and Fish Biodiversity in the Mekong River Basin: A Review. Water 2023, 15, 1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, Y.; Lee, H.S.; Trung, B.H.; Tran, H.-D.; Lall, M.K.; Kakar, K.; Xuan, T.D. Impacts of Mainstream Hydropower Dams on Fisheries and Agriculture in Lower Mekong Basin. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, B.; Huang, X. Mekong Fishes: Biogeography, Migration, Resources, Threats, and Conservation. Rev. Fish. Sci. Aquac. 2022, 30, 170–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, D.; Arias, M.; Van, P.; Vries, T.; Cochrane, T. Analysis of Water Level Changes in the Mekong Floodplain Impacted by Flood Prevention Systems and Upstream Dams; University of Canterbury, Civil and Natural Resources Engineering: Christchurch, New Zealand, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zheng, Y.; Xu, B.; Wang, L.; Han, F.; Zhang, C. Balancing Competing Interests in the Mekong River Basin via the Operation of Cascade Hydropower Reservoirs in China: Insights from System Modeling. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 254, 119967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.X.; Chua, S.D.X. River Discharge and Water Level Changes in the Mekong River: Droughts in an Era of Mega-dams. Hydrol. Process. 2021, 35, e14265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosslett, T.L.; Cosslett, P.D.; Cosslett, T.L.; Cosslett, P.D. The Lower Mekong Basin: Rice Production, Climate Change, ENSO, and Mekong Dams. In Sustainable Development of Rice and Water Resources in Mainland Southeast Asia and Mekong River Basin; Springer: Singapore, 2018; pp. 85–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thilakarathne, M.; Sridhar, V. Characterization of Future Drought Conditions in the Lower Mekong River Basin. Weather. Clim. Extrem. 2017, 17, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ty, T.V.; Lavane, K.; Nguyen, P.C.; Downes, N.K.; Nam, N.D.G.; Minh, H.V.T.; Kumar, P. Assessment of Relationship Between Climate Change, Drought, and Land Use and Land Cover Changes in a Semi-Mountainous Area of the Vietnamese Mekong Delta. Land 2022, 11, 2175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, P.C.; Vu, P.T.; Khuong, N.Q.; Minh, H.V.; Vo, H.A. Saltwater Intrusion and Agricultural Land Use Change in Nga Nam, Soc Trang, Vietnam. Resources 2024, 13, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amnuaylojaroen, T.; Chanvichit, P. Historical Analysis of the Effects of Drought on Rice and Maize Yields in Southeast Asia. Resources 2024, 13, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavane, K.; Kumar, P.; Meraj, G.; Han, T.G.; Ngan, L.H.B.; Lien, B.T.B.; Van Ty, T.; Thanh, N.T.; Downes, N.K.; Nam, N.D.G.; et al. Assessing the Effects of Drought on Rice Yields in the Mekong Delta. Climate 2023, 11, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, N.A.; Benavidez, R.; Tomscha, S.A.; Nguyen, H.; Tran, D.D.; Nguyen, D.T.; Loc, H.H.; Jackson, B.M. Ecosystem Service Modelling to Support Nature-Based Flood Water Management in the Vietnamese Mekong River Delta. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ericson, J.P.; Vörösmarty, C.J.; Dingman, S.L.; Ward, L.G.; Meybeck, M. Effective Sea-Level Rise and Deltas: Causes of Change and Human Dimension Implications. Glob. Planet. Change 2006, 50, 63–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, T.P.; Garschagen, M.; Yang, L.E. A Systematic Investigation of Flood Resilience Measures in the Mekong River Basin. Environ. Sci. Policy 2025, 172, 104228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thu Minh, H.V.; Kumar, P.; Nhat, G.M.; Diep, N.T.H.; Van Ty, T.; Van Duy, D.; Avtar, R.; Downes, N.K. Losing Ground: Flow Fragmentation and Sediment Decline in the Vietnamese Mekong Delta (2000–2023). Earth Syst. Environ. 2025, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minh, H.V.T.; Nam, N.D.G.; Nam, T.S.; Van Cong, N.; Kumar, P.; Downes, N.K. Transition of Flooding Patterns and Environmental Flow in the Mekong Delta, Vietnam over the Last 2 Decades. Nat. Hazards 2025, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duy, D.V.; An, N.T.; Ty, T.V.; Phat, L.T.; Toan, N.T.; Minh, H.V.T.; Downes, N.K.; Tanaka, H. Evaluating Water Level Variability Under Different Sluice Gate Operation Strategies: A Case Study of the Long Xuyen Quadrangle, Vietnam. Hydrology 2025, 12, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, F.E.; Haasnoot, M.; Du, H.; Karabil, S.; Minderhoud, P.S.; Schippers, V.; Scown, M.; Triyanti, A.; Vu, T.; Middelkoop, H. Mapping the Solution Space for Local Adaptation under Global Change: An Test of Concept for the Vietnamese Mekong Delta. Glob. Environ. Change 2025, 95, 103071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tri, V.P.D.; Yarina, L.; Nguyen, H.Q.; Downes, N.K. Progress toward Resilient and Sustainable Water Management in the Vietnamese Mekong Delta. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Water 2023, 10, e1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, J.; Dörr, F.; Vu, H.T.D.; Schenk, A.; Tran, H.V.; Pham, V.C.; Börsig, N.; van der Linden, R.; Nguyen, N.H.; Eiche, E. Seawater Intrusion in River Delta Systems. Inter-Annual Dynamics and Drivers of Salinity Variations in the Southern Mekong Delta, Vietnam. J. Hydrol. 2025, 133745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Binh, D.; Tran, D.D.; Dương, V.H.T.; Bauer, J.; Park, E.; Loc, H.H. Land Use Change in the Vietnamese Mekong Delta: Long-Term Impacts of Drought and Salinity Intrusion Using Satellite and Monitoring Data. iscience 2025, 28, 112723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanh, B.N.; Le Van Thuy, T.; Anh, M.N.; Nguyen, M.N.; Hieu, T.N. Drivers of Agricultural Transformation in the Coastal Areas of the Vietnamese Mekong Delta. Environ. Sci. Policy 2021, 122, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nalbantis, I.; Tsakiris, G. Assessment of Hydrological Drought Revisited. Water Resour. Manag. 2009, 23, 881–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, X.; Guo, S.; Zhou, Y.; Xiong, L. Uncertainties in Assessing Hydrological Drought Using Streamflow Drought Index for the Upper Yangtze River Basin. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 2015, 29, 1235–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khani Temeliyeh, Z.; Khani Temeliyeh, S.; Khani Temeliyeh, H.; Mirabbasi, R. Investigating the Trend of Temperature Changes in Isfahan Station, Iran Using the Sequential Mann-Kendall Method. Water Harvest. Res. 2022, 5, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, C.; Zhu, H.; Ruan, Y.; Xie, Y.; Lei, X.; Lai, S.; Sun, G.; Xing, Z. Spatial and Temporal Variation Characteristics and Frequency Analysis of Extreme Precipitation from 1959 to 2017: A Case Study of the Longtan Watershed, Southwest China. J. Water Clim. Change 2022, 13, 2610–2626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alijani, B.; Mahmoudi, P.; Salighe, M.; Rigi Chahi, A. Study of Annual Maximum and Minimum Temperatures Changes in Iran. Geogr. Res. 2011, 26, 101–122. [Google Scholar]

- Esit, M. Investigation of Innovative Trend Approaches (ITA with Significance Test and IPTA) Comparing to the Classical Trend Method of Monthly and Annual Hydrometeorological Variables: A Case Study of Ankara Region, Turkey. J. Water Clim. Change 2023, 14, 305–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaddikeri, V.; Sarangi, A.; Singh, D.; Jatav, M.S.; Rajput, J.; Kushwaha, N. Trend and Change-Point Analyses of Meteorological Variables Using Mann–Kendall Family Tests and Innovative Trend Assessment Techniques in New Bhupania Command (India). J. Water Clim. Change 2024, 15, 2033–2058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallick, J.; Talukdar, S.; Alsubih, M.; Salam, R.; Ahmed, M.; Kahla, N.B.; Shamimuzzaman, M. Analysing the Trend of Rainfall in Asir Region of Saudi Arabia Using the Family of Mann-Kendall Tests, Innovative Trend Analysis, and Detrended Fluctuation Analysis. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2021, 143, 823–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; He, Y.; Des Walling, E.; Wang, J. Changes in the Sediment Load of the Lancang-Mekong River over the Period 1965–2003. Sci. China Technol. Sci. 2013, 56, 843–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Saito, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Bi, N.; Sun, X.; Yang, Z. Recent Changes of Sediment Flux to the Western Pacific Ocean from Major Rivers in East and Southeast Asia. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2011, 108, 80–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekong Region Dams Database. Available online: https://www.merfi.org/mekongregiondamsdatabase (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Johnston, R.; Kummu, M. Water Resource Models in the Mekong Basin: A Review. Water Resour. Manag. 2012, 26, 429–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kummu, M.; Lu, X.; Wang, J.-J.; Varis, O. Basin-Wide Sediment Trapping Efficiency of Emerging Reservoirs Along the Mekong. Geomorphology 2010, 119, 181–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, B.; Wang, F.; Ni, G. Heating Impact of a Tropical Reservoir on Downstream Water Temperature: A Case Study of the Jinghong Dam on the Lancang River. Water 2018, 10, 951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minh, H.V.T.; Nam, N.D.G.; Ngan, N.V.C.; Van Thinh, L.; Nam, T.S.; Van Cong, N.; Nhat, G.M.; Lien, B.T.B.; Kumar, P.; Downes, N.K. Is Vietnam’s Mekong Delta Facing Wet Season Droughts? Earth Syst. Environ. 2024, 8, 963–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawar, U.; Try, S.; Muttil, N.; Rathnayake, U.; Suppawimut, W. Frequency and Trend Analyses of Annual Peak Discharges in the Lower Mekong Basin. Heliyon 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Su, H.; Chen, F.; Li, S.; Tian, J.; Qin, Y.; Zhang, R.; Chen, S.; Yang, Y.; Rong, Y. The Changing Pattern of Droughts in the Lancang River Basin during 1960–2005. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2013, 111, 401–415. [Google Scholar]

- Li, D.; Long, D.; Zhao, J.; Lu, H.; Hong, Y. Observed Changes in Flow Regimes in the Mekong River Basin. J. Hydrol. 2017, 551, 217–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.X.; Siew, R. Water Discharge and Sediment Flux Changes over the Past Decades in the Lower Mekong River: Possible Impacts of the Chinese Dams. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2006, 10, 181–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Lu, H.; Ruby Leung, L.; Li, H.; Zhao, J.; Tian, F.; Yang, K.; Sothea, K. Dam Construction in Lancang-Mekong River Basin Could Mitigate Future Flood Risk from Warming-induced Intensified Rainfall. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2017, 44, 10–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Wang, X.; Cai, Y.; Li, C. Spatiotemporal Analysis of Precipitation Trends Under Climate Change in the Upper Reach of Mekong River Basin. Quat. Int. 2016, 392, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Qi, J. Hydro-Dam–A Nature-Based Solution or an Ecological Problem: The Fate of the Tonlé Sap Lake. Environ. Res. 2017, 158, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dove, A.; Chapra, S.C. Long-term Trends of Nutrients and Trophic Response Variables for the Great Lakes. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2015, 60, 696–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thai, T.H.; Tuyen, H.M.; Dung, L.H.; Tien, N.X.; Anh, T.D. Flow Developments in The Mekong Delta. VNJHM 2014, 7, 19–23. Available online: https://vjol.info.vn/index.php/TCKHTV/article/view/62799 (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Ruiz-Barradas, A.; Nigam, S. Hydroclimate Variability and Change over the Mekong River Basin: Modeling and Predictability and Policy Implications. J. Hydrometeorol. 2018, 19, 849–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanh, P.T.; Quan, N.H.; Toan, T.Q. Assessment of flow changes on the mainstream of the Mekong River and solutions to ensure water security in the Mekong Delta. VNJHM 2022, 738, 34–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phong, T.H.; Minh, H.V.T.; Ty, T.V. Assessment of the impacts of the An Giang province dike system on the flow regime of the Mekong River in the Mekong Delta. JOMC 2021, 71. Available online: https://ojs.jomc.vn/index.php/vn/article/view/77 (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Van, C.T.; Tuyet, N.T.; An, N.V.; Phung, L.V.; Huy, N.P.; Hong, N.M.; Ngoc, N.Q. Evaluation of Flow Changes in Specific Points in Dong Thap Muoi Area. Vietnam J. Hydrometeorol. 2018, 8, 19–25. Available online: http://tapchikttv.vn/article/136 (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Viet, L.V. ENSO and the Mekong River discharges into the Mekong Delta. JSESS 2016, 32, 57–64. Available online: https://js.vnu.edu.vn/EES/article/view/4064 (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Martinez-Villalobos, C.; Neelin, J.D. Why Do Precipitation Intensities Tend to Follow Gamma Distributions? J. Atmos. Sci. 2019, 76, 3611–3631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, R.M.; Santos, C.A.; Moreira, M.; Corte-Real, J.; Silva, V.C.; Medeiros, I.C. Rainfall and River Flow Trends Using Mann–Kendall and Sen′s Slope Estimator Statistical Tests in the Cobres River Basin. Nat. Hazards 2015, 77, 1205–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, R.O. Statistical Methods for Environmental Pollution Monitoring; Van Nostrand Reinhold Co.: New York, NY, USA, 1987; ISBN 0-442-23050-8. [Google Scholar]

- Hollander, M.; Wolfe, D.A.; Chicken, E. Nonparametric Statistical Methods; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013; ISBN 1-118-55329-2. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.