Abstract

The increasing challenges posed by climate change demand holistic approaches to mitigate ecosystem degradation. In Mediterranean-type regions—biodiversity hotspots facing intensified droughts, fires, and biological invasions—such strategies are particularly relevant. Among invasive species, Acacia longifolia produces substantial woody and leafy biomass when removed, offering an opportunity for reuse as soil-improving material after adequate processing. This study aimed to evaluate the potential of invasive A. longifolia Green-waste compost (Gwc) as a soil amendment to promote soil recovery and native plant establishment after fire. A field experiment was carried out in a Mediterranean ecosystem using Arbutus unedo, Pinus pinea, and Quercus suber planted in control and soils treated with Gwc. Rhizospheric soils were sampled one year after plantation, in Spring and Autumn, to assess physicochemical parameters and microbial community composition (using composite samples) through Next-Generation Sequencing. Our study showed that Gwc-treated soils exhibited higher moisture content and nutrient availability, which translated into improved plant growth and increased microbial richness and diversity when compared with control soils. Together, these results demonstrate that A. longifolia Gwc enhances soil quality, supports increased plant fitness, and promotes a more diverse microbiome, ultimately contributing to faster ecosystem recovery. Transforming invasive biomass into a valuable resource could offer a sustainable, win–win solution for ecological rehabilitation in fire-affected Mediterranean environments, enhancing soil and ecosystem functioning.

1. Introduction

Invasive plant species (IPS) are a major threat to biodiversity, particularly in Mediterranean-type ecosystems, being responsible for disrupting soil composition, nutrient cycling, and water availability, ultimately outcompeting native vegetation [1]. These impacts are further intensified under climate change, which imposes rapid shifts at both species and ecosystem levels [2]. Soil has a vital role in supporting life and maintaining ecological balance being a reservoir and cycling hub for essential nutrients [nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), and potassium (K)], as well as hosting a huge microbial diversity and supporting diverse microbial communities that sustain nutrient recycling and structure. This is particularly determinant in the rhizospheric environment as the most important soil-plant interface [3,4]. Mediterranean-type ecosystems, being recognized as biodiversity hotspots [5], are facing increasingly adverse conditions. Climate predictions point to greater aridity and more unpredictable forest fires [6], and these pressures, combined with the continued spread of IPS, are creating significant challenges for ecosystem stability and conservation [1]. In this regard, IPS out-compete native vegetation, due to profound alterations in soil composition, nutrient cycling, and water availability [7]. Australian Acacia genus is a notable example with worldwide distribution, which is posing a major threat in Mediterranean areas [8,9]. Although prized for its ornamental value and ability to fix N in soil as part of the Fabaceae family, Acacia spp. also become invasive, particularly in coastal areas and disturbed ecosystems, raising concerns on extensive occupied area [10,11,12]. Its rapid growth and dense foliage lead to the formation of monospecific areas, disrupting natural habitats and changing fire regimes [8,10].

Green-waste compost (Gwc) is currently being used to recover degraded soils and could provide a solution for the biomass produced by invasive plant species that otherwise would remain useless. Composting involves the decomposition of organic materials as plant waste into nutrient-rich humus, useful to improve soil quality and support the growth of native vegetation [13], having a beneficial effect on soil microbial communities [14,15]. Previous studies showed an increased carbon and N content in a Gwc made with a mixture of A. longifolia with A. melanoxylon [16,17], and a biomass model for A. longifolia was later developed to support its management and potential valorization as a biomass resource [18].

However, this beneficial effect in soil improvement and plant growth has not been explored so far and must be evaluated, especially integrating both above- and belowground components. With that in mind, our aim was to understand how the incorporation of A. longifolia Gwc changes soil properties and affects early native plant growth after fire. Specifically, we assessed physicochemical parameters along with microbial communities of the rhizosphere and evaluated the effects of the Gwc on the growth of Arbutus unedo, Pinus pinea, and Quercus suber. Our hypothesis is that Gwc incorporation in burnt soils would allow a faster soil recovery along with enhanced plant growth. This pilot study explores the potential of invasive plant compost as a beneficial amendment for both above- and belowground perspectives, while also aiding the management of this invasive species, thereby creating a win–win scenario.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Site Description

Data was collected in an experimental area burnt in June 2020 in Barão de São João, Lagos in the South of Portugal (37.151415, −8.812831), located within Mediterranean climate (Csa, Köppen climate classification), characterized by hot and dry summers and warm and humid winters [19] (Supplementary Figure S1a). In November 2020, 10 × 10 m plots were delimited with machine-made swales (20 cm deep) to create contour bunds, where two treatments were implemented: a control (C), without compost addition, and a Green-waste compost (Gwc) treatment, in which the swales were filled with Acacia longifolia compost. All plots, Gwc and control, contained swales of identical spacing and dimensions to ensure consistent hydrological conditions across treatments. The Gwc was made from chipped biomass, using plant material (including trunks, branches, and leaves) sourced from ca. 1 ha of monospecific A. longifolia area. The biomass was piled up, left in place, and kept moist for one year to facilitate the composting process. Further details are included in [18]. Soil baseline parameters were assessed before experiment implementation, including pH that varied from 4.8 to 5.2 and an organic matter content (OM) of 8.6%. Gwc baseline characteristics showed a pH varying from 7.2 to 7.5 and OM of 11.7%. In each treatment, in February 2021, different native woody species were planted (reaching 0.6 saplings/m2 in each plot) and Arbutus unedo L., Pinus pinea L., and Quercus suber L., were selected to be followed throughout this study.

2.2. Field Sampling and Sample Processing

After one year, in April 2022 (corresponding to Spring assessment), five individuals of each plant species (i.e., A. unedo, P. pinea and Q. suber) were randomly selected for each treatment (Gwc and C), 15 in total per treatment. The same 15 individuals were measured in November after the first raining period (corresponding to the assessment of the Autumn) (Supplementary Figure S1b). For each individual, height was measured and a composite sample of rhizospheric soil was collected (three subsamples surrounding each plant), nearby roots, 10 cm deep. In addition, surrounding each individual, three soil moisture measurements were performed using Theta Probe sensor (Delta-T devices Ltd., Cambridge, United Kingdom). Climatic conditions, during the studied year, are presented in Supplementary Figure S1c. After sieving, the soil samples were divided into subsamples: deep frozen (stored at −80 °C) for high-throughput sequencing technique, and air-dried for physicochemical analysis, including pH (water method), OM, potassium oxide (K), and soluble phosphorus (P) extracted using the Egner–Riehm method, total nitrogen (N), and mineral N (ammonium—NH4+ and nitrates—NO3−), performed in the Laboratório de Plantas e Solos, Universidade de Trás-os-Montes e Alto Douro, Portugal.

Next-generation sequencing was performed in BioISI Genomics through Oxford Nanopore Technology. Rhizospheric soil samples were combined into composite samples by Plant species, Treatment, and Season, a total of 12 samples. After sequencing, data were carefully processed and analyzed through a series of critical steps to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the results. After the removal of low-quality reads (lower than 1200 bps and higher than 1700 bps), the remaining reads were further filtered using Prinseq-lite version 0.20.4 [20]. Additionally, reads with a minimum Phred score of seven were considered acceptable. This rigorous filtering ensured that only high-quality and informative reads were used in the subsequent analyses. The taxonomic classification of the preprocessed reads was performed using Kraken 2 (version 2.1.2), a powerful bioinformatic tool known for its fast and accurate taxonomic classification of DNA sequences, according to [21]. This classification method helps to identify the taxonomic origin of the reads, providing valuable information on the microbial composition of the samples. In this classification, a comprehensive reference database was used, which included NCBI RefSeq reference genomes and NCBI GenBank reference sequences of Bacteria and Fungi.

2.3. Data Analysis

Generalized Linear Models (GLMs) were used to assess the effect of Treatment, Season and their interaction on rhizospheric soil physicochemical parameters (moisture, pH, OM, K, P, N, NH4 and NO3) analyzed with a Gamma distribution. Plant height was assessed using increment (from Spring to Autumn) for each Plant species (A. unedo, P. pinea and Q. suber) and differences between Treatments were calculated through Wilcoxon Mann–Whitney. Non-Metric MultiDimensional Scaling (NMDS) based on bacterial and fungal Operational Taxonomical Units (OTUs) was performed to explore the effect of Treatment (C and Gwc), Season (Spring and Autumn), the combination of the previous two (i.e., Treatment x Season), and Plant species (A. unedo, P. pinea and Q. suber). For both communities, the top 10 taxa at genus level were identified based on the mean value, accounting for the significant effect of Treatment, Season, and the combination of both, regardless of Plant species. The strength of these relationships was evaluated using the squared correlation coefficient (R2). Additionally, an Analysis of Similarity (ANOSIM) was conducted using the Bray–Curtis coefficient to assess the influence of the three variables studied. The abundance of OTUs was not significantly influenced by Plant species. Furthermore, the OTUs sequenced for both bacteriome and mycobiome were used to calculate Shannon–Wiener diversity, Pielou evenness, and Chao indexes (according to [22]). Generalized Linear Models were used to test for effect of Treatment, Season, and their interaction, regardless of Plant species, given the non-significance of this factor. Data analysis was performed using packages rstatix [23], stats, and vegan [22] in R studio v 2023.09.0 [24].

3. Results

3.1. Effect of Gwc Addition on Soil Parameters and Plant Growth

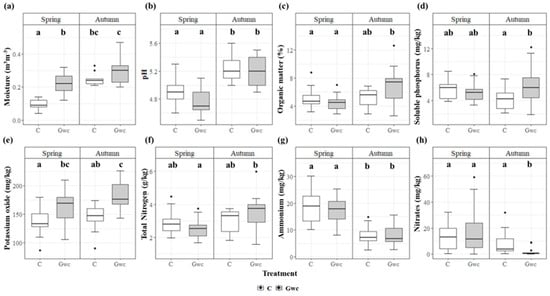

Regarding soil parameters, moisture, K, and NO3 showed significant differences when comparing Treatments and Seasons (Figure 1). While K only showed a significant effect for Treatment (p < 0.01), moisture and NO3 presented an effect for the interaction Treatment × Season (p < 0.001 and p < 0.01, respectively) (Supplementary Table S1). For moisture, significant differences were observed between Gwc and C, showing higher values in Autumn (0.30 ± 0.02 and 0.25 ± 0.01, for Gwc and C, respectively; p < 0.001) (Figure 1a). K content was significantly higher in the Gwc-treated soil in both Seasons (in Spring, 163 ± 7.3 compared to 138 ± 5.9 in C and in Autumn, 182 ± 6.5 and 144 ± 5.5 in C; p < 0.001) (Figure 1e). NO3 showed significant differences for Autumn, with lower values in Gwc-treated soils comparing with C (1.79 ± 0.8 comparing to 8.68 ± 2.3; p < 0.01) (Figure 1h). Also, OM, P, and N showed higher values for Gwc-treated soils in Autumn compared with the other conditions (6.85 ± 0.6, 6.34 ± 0.8 and 3.50 ± 0.3, comparing with 4.47 ± 0.3, 5.25 ± 0.4 and 2.54 ± 0.1 for Gwc in Spring; p < 0.05) (Figure 1a,c,d).

Figure 1.

Rhizospheric soil parameters (mean ± SE, n = 15), namely, moisture (m3m−3) (a), pH (b), organic matter (OM, %) (c), soluble phosphorus (P, mg/kg) (d), potassium oxide (K, mg/kg) (e), total nitrogen (N, g/kg) (f), ammonium (NH4, mg/kg) (g), and nitrates (NO3, mg/kg) (h), assessed for two seasons (Spring and Autumn) and for the two studied treatments, Control (C, in white) and Green-waste compost incorporation (Gwc, in gray). Note that y axis is adjusted to each soil parameter. Significant differences are represented by different letters considering Generalized Linear Models (GLMs) results tested for Treatment, Season, and their interaction for each soil parameter.

When considering each plant species, higher increment was observed for Arbutus unedo and Pinus pinea with Gwc-treated soils (21.8 ± 4.1 cm and 15.0 ± 1.7 cm comparing with 7.8 ± 1.6 cm and 6.2 ± 1.6 cm for Control, respectively). No differences were found for Quercus suber.

3.2. Effect of Gwc Addition on Microbial Communities

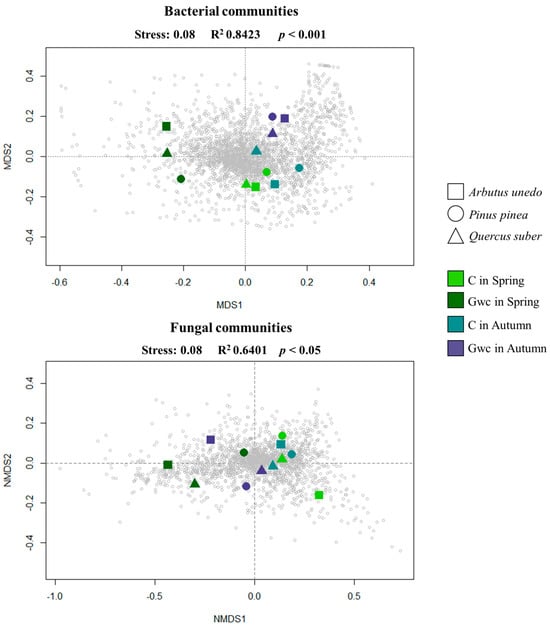

Non-Metric MultiDimensional Scalling (NMDS) showed that the bacterial and fungal communities were clearly segregated considering the combination of Treatment and Season (p < 0.05 and p < 0.01, respectively) (Figure 2). Bacterial community was also influenced by both factors separately, i.e., Treatment (p < 0.05) and Season (p < 0.01) (Supplementary Figure S2a,c); however, for fungal communities, there was only a significant influence of Treatment (Supplementary Figure S2b,d). No significant effect was found for Plant species in both microbial communities.

Figure 2.

Two-dimensional Non-Metric MultiDimensional Scaling (NMDS) ordination based on classified Operation Taxonomic Units (OTUs) for both microbial groups, Bacteria and Fungi (stress value of 0.08) assessed for Plant Species (Arbutus unedo, Pinus pinea and Quercus suber), Season (Spring and Autumn), and Treatment (Control, C and Green-waste compost incorporation, Gwc). Colors represent the combination of Treatment × Season as mentioned in the label; shapes represent the three plant species studies.

Higher diversity, evenness, and richness were found for bacterial group for Gwc-treated soils in Autumn (Supplementary Table S2). In addition, while the number of OTUs between the two Seasons in C increased in ca. 6%, in Gwc this increment was ca. 30%. However, despite no statistical significance, the greatest diversity (4.50 ± 0.14) was present for fungal communities in Gwc-treated soils in Autumn.

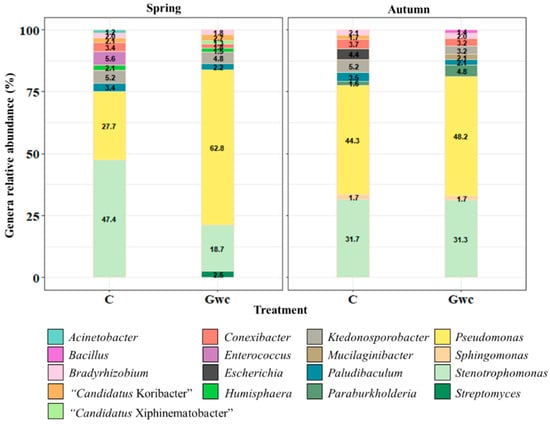

Considering the top 10 at the genus level, the bacteriome was dominated by Pseudomonas and Stenotrophomonas (ca. 75%), followed by Paludibaculum, Ktedonosporobacter, Conexibacter, and Bradyrhizobium, which are common but with differences in abundance, depending on Treatment and/or Season (Figure 3). When considering both Treatment and Season, bacterial communities revealed differences: in Spring, “Candidatus Xiphinematobacter” and Streptomyces appear in the top 10 on Gwc-treated soils, while in Autumn, Mucilaginibacter and Bacillus were present. Changes also occur considering Season, with Humisphaera being characteristic of Spring and Sphingomonas and Paraburkholderia of Autumn.

Figure 3.

Top 10 genera of the Bacteria identified (cumulative relative abundance, %) in rhizospheric soil considering the treatments, Control (C), and Green-waste compost incorporation (Gwc) in the two seasons, Spring and Autumn. Colors are assigned according to bacterial genera.

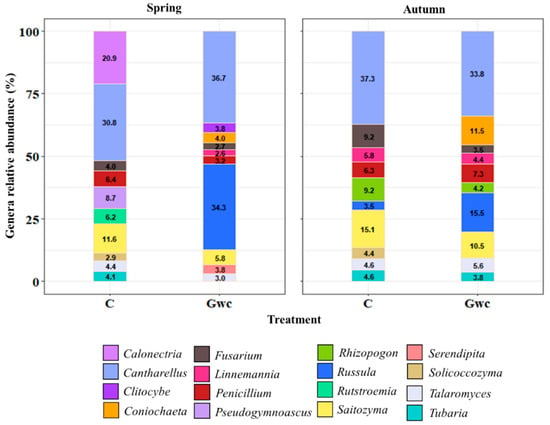

Regarding fungal communities, the mycobiome was dominated in ca. 31–38% by the genus Cantharellus in both treatments and seasons (Figure 4). Other genera were present regardless of Treatment and Season, despite differences in abundance, such as Fusarium, Penicillium, Saitozyma, and Talaromyces. In Gwc-treated soils, Russula and Coniochaeta increased in abundance with 34.3 and 15.5% as well as 4.0 and 11.5%, considering Spring and Autumn, respectively; simultaneously, Serendipita reached the top 10 in Spring following Gwc-treated soils.

Figure 4.

Top 10 genera of the Fungi identified (cumulative relative abundance, %) in rhizospheric soil considering the treatments, Control (C) and Green-waste compost incorporation (Gwc), in the two seasons, Spring and Autumn. Colors are assigned according to fungal genera.

4. Discussion

Green waste compost (sensu lato) is a rich substrate that increases (i) soil organic matter (OM); (ii) water-holding capacity and soil structure; (iii) nutrient availability for plants [14,15,25]. Accordingly, our findings indicate a beneficial effect of incorporating Acacia longifolia Gwc into the soil after a disturbance, promoting the establishment of native plants and suggesting its potential use as a valuable resource. We observed an improvement in soil parameters along with a significant increase in plant growth, particularly for Arbutus unedo and Pinus pinea. Interestingly, these beneficial effects contrast with previous studies reporting that A. longifolia invasions lead to negative changes in soil properties that can suppress the regeneration of native species [10].

After incorporating Gwc into the soil, both the bacteriome and mycobiome changed, potentially explaining the improved establishment of the young native plants. Naturally, there is a core group of microbes that maintain higher abundance in both treatments, preserving the soil’s microbial fingerprint and contributing positively to the recovery/adaptation of the local vegetation. These include the bacteria Stenotrophomonas and Pseudomonas, and the fungi Cantharellus and Saitozyma which have Plant-Growth Promoting properties (PGP) and are currently used in biobased, sustainable soil regeneration strategies [26,27]. For example, species of the genus Cantharellus (phylum Basidiomycota) form mycorrhizal associations that support plant growth [28], while Saitozyma, another Basidiomycota, has recently been reported to enhance tolerance to environmental stress.

However, following Gwc incorporation, different bacterial and fungal genera emerge among the top 10. The improved soil moisture, structure, and nutrient availability likely create more favorable conditions for plant growth, driving alterations in microbiome composition. The bacterial genus “Candidatus Xiphinematobacter” was more abundant in Gwc-treated soils. As a strict nematode endosymbiont [29], its increased presence suggests that Gwc may also enhance the nematode community, which also has a crucial role on soil quality [30]. Additionally, fungal genera Clitocybe, Russula, Serendipita, and Coniochaeta were also more abundant, potentially promoting plant development. Clitocybe (Basidiomycota) is an ectomycorrhizal fungus that supports plant growth through organic matter decomposition [31], while Russula forms mutualistic mycorrhizal associations with a broad range of plants [32], opening the possibility of extending the application of A. longifolia Gwc applications to other ecosystems. Coniochaeta (Ascomycota), previously proposed as part of the root-nodule and/or endophytic community of A. longifolia [33], was also more abundant in Gwc-treated soil, suggesting that this invasive plant specific microbiome may enhance soil functionality by facilitating other symbiotic relationships [34].

Also, microbiome seasonal changes were observed. Streptomyces and “Candidatus Xiphinematobacter” were detected only in Spring. Streptomyces (Actinomycetota phylum) is known to alleviate soil-borne diseases through the production of antibiotics and bioactive compounds [35] and, together with the phytostimulatory effects of Bacillus [36], possibly provide a competitive advantage for plants, potentiating growth. On the other hand, Mucilaginibacter and Bacillus are prevalent in Autumn. Mucilaginibacter, a good ecological indicator, responds to soil chemical properties and seasonal variation [37]; thus, its higher abundance in Gwc-treated soils might reflect the improved soil quality.

The increasing abundance of PGP Bacteria and mycorrhizal fungi are key factors to the success of reforestation actions as suggested by [38]. In this context, the incorporation of Gwc in an early stage of plant development could not only improve soil quality, but also foster a richer and more diverse microbiome, with more impact on bacteriome. This becomes particularly significant since, from Spring to Autumn, an enrichment in bacterial abundance may contribute to enhanced plant growth rates. These microbial communities are good ecological indicators of short-term soil changes, as they show rapid fluctuations in abundance and richness in response to environmental conditions [39]. Therefore, soil regenerative actions involving the incorporation of Gwc could be valuable, under projected Mediterranean climate conditions, characterized by increasing temperature and aridity, which are expected to compromise native communities [40].

This pilot study suggests that A. longifolia Gwc holds considerable potential for improving soil conditions and promoting plant growth, opening a possible broader applicability of this type of compost amendment in post-disturbance ecosystems. Long-term monitoring is essential to better understand the dynamics of plant–microbe interactions and to determine the persistence of these effects over time. For instance, monitoring vegetation over time is particularly relevant for species with slow growth rates, such as Quercus suber, which, despite improved soil conditions, has not yet exhibited noticeable differences in development [41]. However, the consistent initial improvements observed highlight the capacity of A. longifolia Gwc to enhance soil quality and strengthen plant resilience under (a)biotic stress. Together, these findings indicate that A. longifolia Gwc is not only a valuable tool for ecological rehabilitation but also a promising amendment for ecological restoration, particularly in degraded systems where restoring soil function is essential for ecosystem recovery under changing environmental conditions.

Limitations and Future Perspectives

We acknowledge that this study is preliminary, with a limited number of plots (C vs. Gwc) and a relatively short study period (from Spring to Autumn), which restricts the robustness to allow generalizations. However, several factors contribute to the importance and consistency of the results: (1) the study was conducted under field conditions, providing ecologically relevant insights; (2) plant species were in an early developmental stage, having limited canopy and root system development, making its potential interactions to a minimum; (3) the species were all under the same controlled spacing and within the same microsite, allowing us to minimize environmental variability. Considering the pilot nature of the study, our experimental design is important to validate our hypothesis, show the relevance of converting invasive plant material into a Gwc as an ecological solution, and support the need to further explore these patterns to strengthen and broader our findings.

5. Conclusions

This study provides initial evidence that the incorporation of Acacia longifolia Gwc into post-fire soils can improve physicochemical properties, support richer and more diverse soil microbial communities, and help the early establishment of native plants. Here, we demonstrate that converting Acacia longifolia biomass into a Gwc transforms an environmental challenge into an opportunity for soil rehabilitation and restoration. The use of this Gwc enhances soil quality and promotes ecosystem recovery, offering a sustainable pathway to mitigate the negative legacy of invasion.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/resources15010002/s1. Figure S1: Field site location. Sampling design and climatic characterization. Table S1: Summary of Generalized Linear Models (GLMs) assessing the influence of Treatment and Season and their interaction on rhizospheric soil parameters. Table S2: Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) data (means ± SE) and diversity metrics for bacteria and fungi. Figure S2: Two-dimensional Non-metric MultiDimensional Scaling (NMDS) ordination based on classified Operation Taxonomic Units (OTUs) for both microbial groups assessed for Plant Species, Season, and Treatment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.J., C.M. and H.T.; methodology, J.J., C.M. and H.T.; validation, C.M. and H.T.; formal analysis, J.J.; data curation, J.J.; writing—original draft preparation, J.J.; writing—review and editing, J.J., C.M. and H.T.; funding acquisition, J.J., C.M. and H.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia (FCT) through the PhD research fellowship 2021.08482.BD (DOI: 10.54499/2021.08482.BD) and by Asociación Española de Ecología Terrestre (AEET) through the program “Tomando la iniciativa”, attributed to Joana G. Jesus. Also, support was also given by FCT Portuguese National Funds attributed to CE3C within the strategic project UID/BIA/00329/2020 (DOI: 10.54499/UIDB/00329/2020) and UID/BIA/00329/2025, as well as the Project R3forest “Using exotic biomass to post-fire recovery: reuse, regenerate and reforest” (PCIF/GVB/0202/2017).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We thank the BioISI Genomics team for all the support in sample preparation and bioinformatic analysis. A major acknowledgment to Florian Ulm for the idea of using this biomass and for leading the R3forest project (PCIF/GVB/0202/2017). Furthermore, we are also grateful to Andreia Anjos and Madeleine Laurent for their help and pleasant company during fieldwork. This work was supported by the INVASIVES project, funded by CIÊNCIAS and FCiências.ID.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| C | Control |

| Gwc | Green-waste compost |

| IPS | Invasive Plant Species |

| K | Potassium |

| N | Nitrogen |

| NMDS | Non-Metric MultiDimensional Scaling |

| OM | Organic matter |

| OTUs | Operational Taxonomic Units |

| P | Phosphorus |

| PGP | Plant Growth Promoting |

References

- IPBES. Thematic Assessment Report on Invasive Alien Species and Their Control of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services; Roy, H.E., Pauchard, A., Stoett, P., Truong, T.R., Eds.; IPBES Secretariat: Bonn, Germany, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johns, C. Living Soils: The Role of Microorganisms in Soil Health. In Independent Strategic Analysis of Australia’s Global Interests; Future Directions International: Dalkeith, Australia, 2017; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Mukhtar, H.; Wunderlich, R.F.; Muzaffar, A.; Ansari, A.; Shipin, O.V.; Cao, T.N.; Lin, Y.P. Soil microbiome feedback to climate change and options for mitigation. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 882, 163412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vezzani, F.; Anderson, C.; Meenken, E.; Gillespie, R.; Peterson, M.; Beare, M.H. The importance of plants to development and maintenance of soil structure, microbial communities and ecosystem functions. Soil Tillage Res. 2018, 175, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauquelin, T.; Michon, G.; Joffre, R.; Duponnois, R.; Génin, D.; Fady, B.; Bou Dagher-Kharrat, M.; Derridj, A.; Slimani, S.; Badri, W.; et al. Mediterranean forests, land use and climate change: A social-ecological perspective. Reg. Environ. Change 2018, 18, 623–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pörtner, H.O.; Roberts, D.C.; Tignor, M.; Poloczanska, E.S.; Mintenbeck, K.; Alegría, A.; Craig, M.; Langsdorf, S.; Löschke, S.; Möller, V.; et al. (Eds.) Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. In Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC); Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Michelan, T.S.; Thomaz, S.M.; Bando, F.M.; Bini, L.M. Competitive effects hinder the recolonization of native species in environments densely occupied by one invasive exotic species. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorenzo, P.; González, L.L.; Reigosa, M. The genus Acacia as invader: The characteristic case of Acacia dealbata Link in Europe. Ann. For. Sci. 2010, 67, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza-Alonzo, P.; Rodríguez, J.; González, L.; Lorenzo, P. Here to stay. Recent advances and perspectives about Acacia invasion in Mediterranean areas. Ann. For. Sci. 2017, 74, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchante, E.; Kjøller, A.; Struwe, S.; Freitas, H. Short- and long-term impacts of Acacia longifolia invasion on the belowground processes of a Mediterranean coastal dune ecosystem. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2008, 40, 210–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colaço, M.C.; Sequeira, A.C.; Skulska, I. Genus Acacia in Mainland Portugal: Knowledge and Experience of Stakeholders in Their Management. Land 2023, 12, 2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchante, E.; Gouveia, A.C.; Brundu, G.; Marchante, H. Australian Acacia species in Europe. In Wattles. Australian Acacia Species Around the World; Richardson, D.M., Le Roux, J.J., Marchante, E., Eds.; CABI: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maheshwari, D.K. Composting for Sustainable Agriculture; Springer: Cham, Switzerland; Heidelberg, Germany; New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Khaleel, R.; Reddy, K.R.; Overcash, M.R. Changes in Soil Physical Properties Due to Organic Waste Applications: A Review. J. Environ. Qual. 1981, 10, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perucci, P.; Dumontet, S.; Bufo, S.A.; Mazzatura, A.; Casucci, C. Effects of organic amendment and herbicide treatment on soil microbial biomass. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2000, 32, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brito, L.M.; Saldanha, J.; Mourão, I.; Nestler, H. Composting of Acacia longifolia and Acacia melanoxylon invasive species. Acta Hortic. 2013, 1013, 211–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brito, L.M.; Reis, M.; Mourão, I.; Coutinho, J. Use of Acacia Waste Compost as an Alternative Component for Horticultural Substrates. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2015, 46, 1814–1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulm, F.; Estorninho, M.; Jesus, J.G.; de Sousa Prado, M.G.; Cruz, C.; Máguas, C. From a Lose–Lose to a Win–Win Situation: User-Friendly Biomass Models for Acacia longifolia to Aid Research, Management and Valorisation. Plants 2022, 11, 2865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. FAO/UNESCO Soil Map of the World|FAO SOILS PORTAL|Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2015. Available online: https://www.fao.org/soils-portal/data-hub/soil-maps-and-databases/faounesco-soil-map-of-the-world/en/ (accessed on 8 September 2025).

- Schmieder, R.; Edwards, R. Quality control and preprocessing of metagenomic datasets. Bioinformatics 2011, 27, 863–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, D.E.; Lu, J.; Langmead, B. Improved metagenomic analysis with Kraken 2. Genome Biol. 2019, 20, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oksanen, J.; Simpson, G.; Blanchet, F.; Kindt, R.; Legendre, P.; Minchin, P.; O’Hara, R.; Solymos, P.; Stevens, M.; Szoecs, E.; et al. Vegan: Community Ecology Package_. R Package Version 2.6-4, 2022. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=vegan (accessed on 8 September 2025).

- Kassambara, A. _Rstatix: Pipe-Friendly Framework for Basic Statistical Tests_. R Package Version 0.7.2, 2023. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=rstatix (accessed on 8 September 2025).

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2023; Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/doc/manuals/r-release/fullrefman.pdf (accessed on 8 September 2025).

- Donn, S.; Wheatley, R.E.; McKenzie, B.M.; Loades, K.W.; Hallett, P.D. Improved soil fertility from compost amendment increases root growth and reinforcement of surface soil on slopes. Ecol. Eng. 2014, 71, 458–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoyo, G.; Orozco-Mosqueda, M.C.; Govindappa, M. Mechanisms of biocontrol and plant growth-promoting activity in soil bacterial species of Bacillus and Pseudomonas: A review. Biocontrol Sci. Technol. 2012, 22, 855–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Rithesh, L.; Kumar, V.; Raghuvanshi, N.; Chaudhary, K.; Abhineet, N.; Pandey, A.K. Stenotrophomonas in diversified cropping systems: Friend or foe? Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1214680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonfante, P.; Genre, A. Mechanisms underlying beneficial plant—fungus interactions in mycorrhizal symbiosis. Nat. Commun. 2010, 1, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludwig, W.; Euzéby, J.; Whitman, W.B. Taxonomic outlines of the phyla Bacteroidetes, Spirochaetes, Tenericutes (Mollicutes), Acidobacteria, Fibrobacteres, Fusobacteria, Dictyoglomi, Gemmatimonadetes, Lentisphaerae, Verrucomicrobia, Chlamydiae, and Planctomycetes. In Bergey’s Manual® of Systematic Bacteriology; Krieg, N.R., Ludwig, W., Whitman, W.B., Hedlund, B.P., Paster, B.J., Staley, J.T., Ward, N., Brown, D., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Liu, C.; Zhao, H.; Gao, G.; Ji, G.; Hu, F.; Li, H. Similar positive effects of beneficial bacteria, nematodes and earthworms on soil quality and productivity. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2018, 130, 202–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dąbrowska, G.B.; Garstecka, Z.; Trejgell, A.; Dąbrowski, H.P.; Konieczna, W.; Szyp-Borowska, I. The impact of forest fungi on promoting growth and development of Brassica napus L. Agronomy 2021, 11, 2475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Looney, B.P.; Meidl, P.; Piatek, M.J.; Miettinen, O.; Martin, F.M.; Matheny, P.B.; Labbé, J.L. Russulaceae: A new genomic dataset to study ecosystem function and evolutionary diversification of ectomycorrhizal fungi with their tree associates. New Phytol. 2018, 218, 54–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jesus, J.G.; Máguas, C.; Dias, R.; Nunes, M.; Pascoal, P.; Pereira, M.; Trindade, H. What If Root Nodules Are a Guesthouse for a Microbiome? The Case Study of Acacia longifolia. Biology 2023, 12, 1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Challacombe, J.F.; Hesse, C.N.; Bramer, L.M.; McCue, L.A.; Lipton, M.; Purvine, S.; Nicora, C.; Gallegos-Graves, L.V.; Porras-Alfaro, A.; Kuske, C.R. Genomes and secretomes of Ascomycota fungi reveal diverse functions in plant biomass decomposition and pathogenesis. BMC Genom. 2019, 20, 976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olanrewaju, O.S.; Babalola, O.O. Streptomyces: Implications and interactions in plant growth promotion. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019, 103, 1179–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, N. Chapter 2: An insight through Root-Endophytic-Mutualistic Association in improving crop productivity and sustainability. In Symbiotic Soil Microorganisms—Biology and Applications; Shrivastava, N., Mahajan, S., Varma, A., Eds.; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; Volume 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruczyńska, A.; Kuźniar, A.; Podlewski, J.; Słomczewski, A.; Grządziel, J.; Marzec-Grządziel, A.; Gałązka, A.; Wolińska, A. Bacteroidota structure in the face of varying agricultural practices as an important indicator of soil quality—A culture independent approach. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2023, 342, 108252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burdman, S.; Jurkevith, E.; Okon, Y. Recent advances in the use of plant growth promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) in agriculture. In Microbial Interactions in Agriculture and Forestry; Subba Rao, N.S., Dommergues, Y.R., Eds.; Science Publishers, Inc.: Enfield, NH, USA, 2020; Volume 2, pp. 229–250. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, F.; Wang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, J.; Xie, R.; Sun, Z. Development of Microbial Indicators in Ecological Systems. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Błońska, E.; Piaszczyk, W.; Staszel, K.; Lasota, J. Enzymatic activity of soils and soil organic matter stabilization as an effect of components released from the decomposition of litter. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2021, 157, 103723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, G.; Correia, O.; Martins-Loução, M.A.; Catarino, F. Phenological and growth patterns of the Mediterranean oak Quercus suber L. Trees 1994, 9, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.