1. Introduction

Food waste is a significant problem around the globe. Food waste reduction is a crucial issue that requires attention due to its negative impact on the environment, economy, and society. Around one-third of the food produced worldwide is never consumed, leading to significant greenhouse gas emissions, wasted resources, and increased hunger and poverty [

1,

2]. Food waste generates toxic gases and, therefore, presents a serious risk to human health and the environment [

3]. In addition, food waste results in a loss of limited resources including land, water, and energy [

4]. A study of food waste in the sector of tourism and food service found that wasted food primarily in restaurants and hotels can be attributed to various factors, such as overproduction, poor forecasting, and customer behavior [

5]. Aschemann-Witzel et al. [

6] found that factors such as income, price, and the appearance of food can influence consumer behavior and contribute to food waste. Dos Santos et al. [

7] concluded that consumer behavior is a significant factor in the generation of food waste. A recent study by Principato et al. [

8] summarized the various consumer-level aspects of the food waste phenomena and proposed frameworks to explain food waste behavior. Massive amounts of waste negatively affect the environment, which does not only impact Thailand but can also lead to global problems [

9]. Food waste can also produce large amounts of methane. Methane has a greater global warming potential than carbon dioxide [

10]. According to Munesue et al. [

11], food waste generates a significant amount of greenhouse gas emissions and contributes to environmental degradation. In addition to the inadequate management of the already-existing food waste, the primary issue with food waste is the unnecessarily high agricultural production.

The food waste hierarchy best describes the priorities when managing food waste. The most favorable option is prevention, followed by re-use, recycle, recovery, and disposal as the least favorable option [

12]. It is the responsibility of households and individual consumers to contribute to the reduction of food waste by using the 3R principle which consists of Reduce, Reuse, and Recycle [

13]. Using this 3R principle can reduce the use of resources as well. Reduce means to decrease the amount of food and to manage the amount of food, i.e., not hoarding too much food. Reuse is the use of leftover ingredients to cook a new menu and to keep leftover food that can still be eaten for the next meal, which will assist in minimizing the quantity of wasted food. Recycle is the use of food waste to make compost or animal feed. Following the 3R principles, consumers can help to reduce economic losses, reduce the use of natural resources, reduce global warming, and protect the environment. Consumer perceptions and behaviors are the key drivers in food waste reduction [

14]. There are various factors of food waste reduction, including environmental awareness, economic incentives, and cultural norms [

15]. To reduce the amount of food waste, it is crucial to address the root causes of the problem at all steps of the food supply chain, from farming to eating [

16]. Food waste can be significantly decreased by taking simple steps like meal planning, creating shopping lists, utilizing leftovers, and properly storing food [

17]. Governments and businesses can also take steps to reduce the quantity of food waste by implementing policies, e.g., food waste reduction targets and suppressing and recycling food loss [

18]. According to our estimates, a third of the globally produced food for people’s use is wasted [

19,

20]. The amount of wasted food is a problem in developed countries where it contributes significantly to household waste [

21].

Food waste in Thailand is a growing issue, as the country’s economic development has led to a rise in food production and consumption. According to a study, the amount of food waste produced in Thailand is estimated to be 9.3 million tons annually [

22]. A study indicated that food waste generates the largest part of all waste in Bangkok between 42% and 45% [

23]. This paper focuses on both edible and inedible food waste. Edible food waste refers to food that is still safe and suitable for human consumption but is wasted. Inedible food waste, on the other hand, refers to the parts of food that are not intended and are no longer safe for human consumption. In developing countries, the key sources of food waste are households, supermarkets, and the hospitality industry [

24]. The lack of proper waste management infrastructure and education about the impacts of food waste pose significant challenges to minimize food waste in Thailand [

25]. Reducing food waste in households, where it originates, is one strategy to reduce the quantity of waste. Thailand has taken various actions to achieve its goal of halving food waste within the next 10 years under the Sustainable Development Goals (SCGs). In order to meet the goals, the Pollution Control Department in Thailand is responsible for studying, analyzing, and formulating strategies, guidelines, and measures to minimize food waste, including tracking the amount of food waste and managing it effectively. The key factor of food waste reduction remains to be consumer behavior, which is studied in this paper.

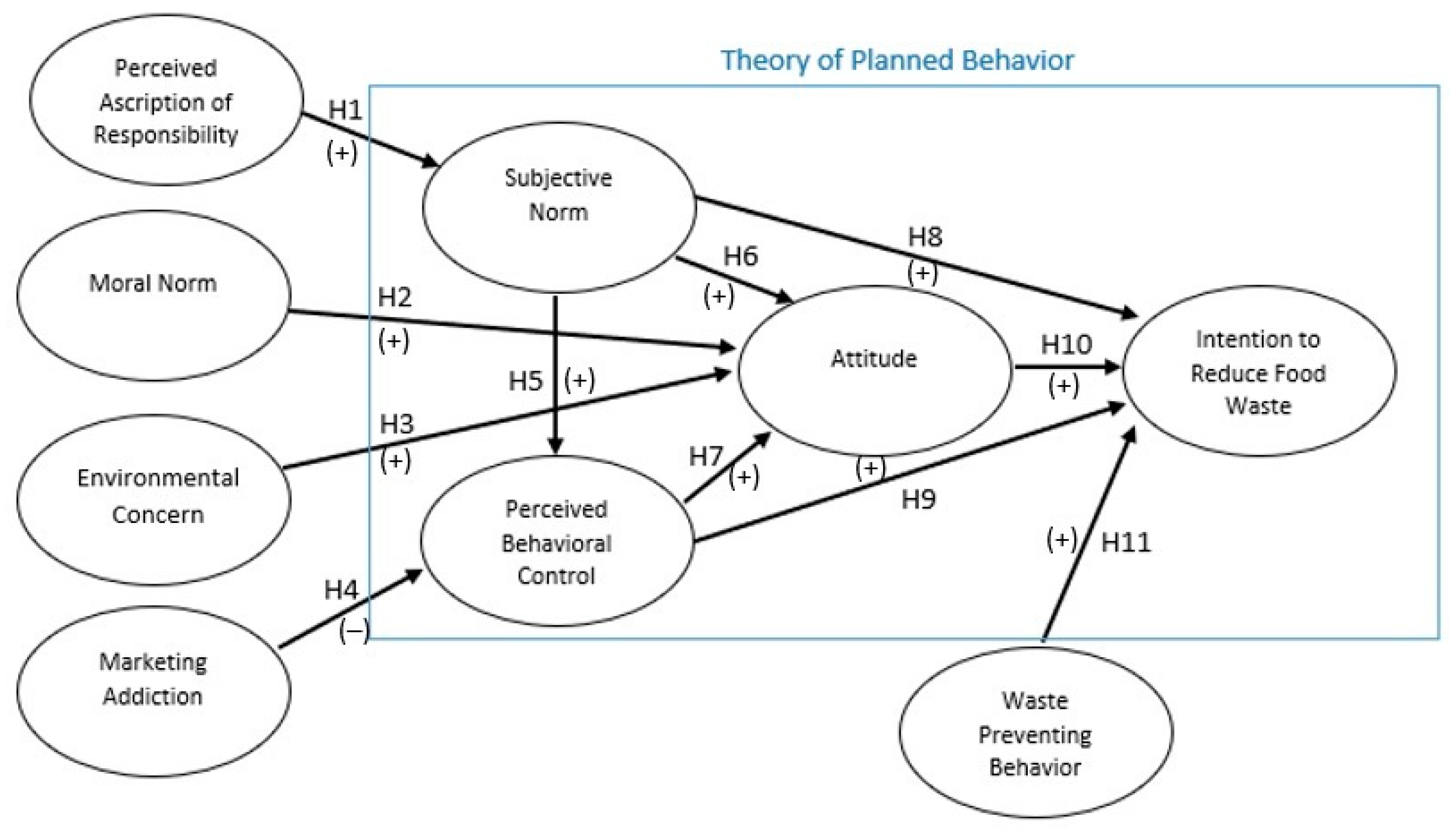

This article aims to illustrate the awareness of food waste behavior and aspects for the reduction of food waste, as well as analyze the waste-preventing behavior of individuals and investigate the factors which can explain the intention to reduce food waste. This study focuses on the behavioral characteristics of consumers. In addition to examining how the difficulties of food waste reduction may be handled within the framework of a self-manageable basis, it seeks to identify the elements that contribute to food waste formation. This paper analyzes the factors which affects the intention to minimize food waste based on the theory of planned behavior (TPB), with the variables’ subjective norm, attitude, perceived behavioral control, and the intention to reduce food waste. Furthermore, it extends the TPB by adding other important factors (waste preventing behavior, perceived ascription of responsibility, moral norm, environmental concern, and marketing addiction) which impact the intention to reduce wasted food. The moral norm is an important factor which influences attitudes, which in turn may impact the intention. Thus, the moral norm might be a key effect on the reduction of wasted food and must be included in the research framework. A conceptual framework was created in earlier studies to analyze consumer behavior with reference to food waste. However, to further explore the intention and behavior towards the waste of food, additional studies which cover more factors are required. This paper fills that gap. The TPB is able to explain the individual’s behavior. This study examines whether its main variables and the addition of the new variables have a substantial impact on the goal of reducing the waste of food. Moreover, it tries to find reasons and determinants for the especially high amounts of food waste in Thailand. It analyzes why Thai people generate significant amounts of food waste and how to decrease it. The existing literature studied factors which impact the intention to minimize wasted food by using the TPB, but important variables were omitted. This article fills the gap by expanding the TPB with relevant factors related to food waste, such as waste-preventing behavior. Hence, the paper shows a more complete picture of consumer behavior towards food waste.

This study is structured as follows: A literature review and the formulation of hypotheses begins in

Section 2. Then,

Section 3 outlines the research methodology, sample and data gathering, and development of measures.

Section 4 shows the analyses and results. The study’s theoretical and practical implications are discussed in

Section 5.

Section 6 of this research paper serves as a summary and discusses the major findings from this study.

6. Conclusions

Nowadays, consumers have clearly given importance to food waste as it has a damaging effect on the world and the environment. We modeled the intention to minimize wasted food in Thailand. Hence, the theory of planned behavior’s main variables and new concepts were combined in a structural equation model. This article focuses on the significant relationships between several factors which relate to consumer behavior regarding the reduction of the quantity of food waste. We executed quantitative research using questionnaires with 369 valid respondents who were aware of and focused on the issue of wasted food in Thailand. The results suggest that Perceived Ascription of Responsibility, Environmental Concern, Marketing Addiction, Subjective Norm, Attitude, Perceived Behavioral Control, and Waste Preventing Behavior all play a role in shaping individuals’ intentions to minimize wasted food. The attitude, perceived behavioral control, and waste preventing behavior are the main predictors of the intention to decrease the amount of wasted food. This finding guides the development of behavior change strategies, educational programs, policies, and future research efforts to encourage waste prevention and ultimately reduce food waste. Consumers who engage in behaviors to prevent food waste are more likely to have the intention to minimize wasted food. Further initiation and support of attitude, waste preventing behavior, perceived behavioral control, and environmental concern may help to increase consumers’ intention to minimize wasted food, such as developing educational campaigns highlighting the impacts of food waste and providing practical tips for waste reduction, using signage and labels to encourage portion control, providing recipe ideas for using leftovers, improving access to food storage guidelines, composting facilities, and meal-planning apps. The results provide useful insights into the relations between several constructs and food waste behaviors, and they may help to form interventions aimed at decreasing food waste.