Abstract

The present study examines the roles of perceived quality (PQY) and technology attitudes (TAS) in affecting customers’ attitudes toward artificial intelligence (ATAI). The study also explores ATAI’s influence on customer experience (CEE), fashion involvement (FIT), marketing analytics capability (MAC), and customer purchase decisions (PDN) among Saudi fashion retail customers. The study is based on a rigorous review of the literature, and two theories, the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) and the Consumer Decision-Making Theory (CDMT), underpin the study framework. The study is quantitative, and the results are based on a sample size of 344. Using path analysis, the study indicates a positive effect of PQY and TAS on ATAI. ATAI is a positive predictor of FIT, CEE, and PDN, but a negative predictor of MAC. In addition, factors such as CEE and MAC positively affect PDN. Finally, FIT mediates the link between ATAI and PDN. The study’s findings assist retailers in developing AI-based solutions to improve marketing strategies and drive sales. This study contributes to AI acceptance in retail, encouraging researchers and policymakers to embrace the use of AI in consumer markets. Finally, this study’s outcomes enrich the existing literature with empirical evidence from Saudi Arabia.

1. Introduction

The rapid digitalization of the fashion industry is driving the use of artificial intelligence (AI) systems, which serve as the sustaining platforms that help develop decision-support systems and digital infrastructures that guide consumers from initial browsing to final purchase decisions. In these systems, AI positively shapes customer perceptions and attitudes during the consumer journey. The functions and features of AI help in developing a robust decision-support mechanism. This shapes behavior through modified recommendations, which are usually preferred by consumers [1]. This reduces their search effort and uncertainty via AI-driven filtering and matching tools [2]. It also enhances decision confidence through virtual try-ons and fit predictions, and increases the perceived value and recommendations regarding the products [3,4]. Similarly, e-commerce is very prominent in multi-brand stores [5,6]. Therefore, understanding customers’ attitudes toward artificial intelligence (ATAI) and how these attitudes influence purchase decisions (PDN) has become important, with artificial intelligence (AI) and related technologies playing a leading role in bringing different consumer experiences (CEE) in various contexts. AI positively assists technology that influences customers’ purchasing behaviors through dynamic pricing and automated services and also affects customer loyalty and brand perception [7,8,9]. ATAI focuses on innovative technologies as well as dimensions such as trust, perceived usefulness, and risk [9,10]. In this way, PDN underlines the consumer’s reasoning and behavioral commitment toward purchasing a product or service via online or digital platforms, which leads to willingness to buy from online stores [11,12,13,14,15].

Perceived quality (PQY) and technology attitudes (TAS) significantly assist the customers to develop their ATAI. Notably, PQY represents the consumer’s overall valuation of a product, encompassing the product’s quality and the trustworthiness and credibility of online sellers [16,17]. Likewise, PQY massively influences ATAI as these reinforces customers’ beliefs and feelings toward technology and causes them to be eager to develop their trends and to solve their problems using technology [18,19].

Simultaneously, ATAI positively impacts fashion involvement (FIT), customer experience (CEE), marketing analytics capability (MAC), and PDN. More specifically, FIT represents the extent to which customers are emotionally engaged with fashion, seeing it as part of their identity and lifestyle [20,21]. CEE represents the AI experience, which helps meet customers’ expectations and achieve their satisfaction with the purchase [22,23,24]. Furthermore, MAC indicates the customer’s ability to systematically collect, integrate, and analyze diverse data sources and information concerning broader market trends. Firms develop their ability to recognize products in response to market changes [25], thereby improving PDN [26].

The domain literature offers several insights into the factors—such as customer engagement, enjoyment, TAS, perceived efficiency, PQY, valuable services, and confidence in digital technologies—that positively influence ATAI [27,28,29,30,31]. Likewise, PDN is predicted by privacy, AI transparency, marketing competence, social experiences, consumer perceptions, technological innovation, consumer loyalty, confidence, the quality of big data analytics, customer psychology, business intelligence, ATAI, shopping convenience, optimizing purchase, trust and perceived control, and much more in several markets [8,24,32,33,34,35].

Nevertheless, the literature lacks a comprehensive and integrated approach that incorporates the analytical contributions of PQY and TAS to ATAI, as well as ATAI’s contributions to FIT, CEE, MAC, and PDN simultaneously. Furthermore, FIT, as an outcome of ATAI and a mediator between ATAI and PDN, still needs serious examination. More importantly, Saudi Arabian consumers who interact with AI in fashion retail stores have still not received enough attention, despite the massive utilization of AI in response to the dynamic fashion trends of Saudi Arabia’s customers [36,37,38]. Accordingly, the researcher raises the following questions:

RQ1. How do PQY and TAS affect ATAI among Saudi Arabian customers who interact with AI in fashion retail stores?

RQ2. How does ATAI enhance FIT, CEE, PDN, and MAC among Saudi Arabian customers who interact with AI in fashion retail stores?

RQ3. How does FIT mediate the connection between ATAI and PDN among Saudi Arabian customers who interact with AI in fashion retail stores?

The findings of this study provide valuable guidelines for policymakers and retailers on improving marketing strategies, with AI employment as a top priority. Furthermore, the study contributes to and encourages domain researchers to conduct their studies in markets where AI and its employment are of enormous significance. Lastly, this study’s findings contribute to the existing literature by adding empirical evidence from the fashion industry in a developing context (Saudi Arabia).

2. Literature Review and Theoretical Framework

Theoretically, the implementation of AI-driven systems represents a multi-layered technological environment. These systems positively shape cognition, perception, and behavior [39,40]. AI implementations are regarded as substantial digital systems that jointly influence user attitudes and decision pathways. In this way, these systems assimilate algorithms, interactive interfaces, data infrastructures, technology attitudes, perceived quality, and customer experience [15,23]. There are several factors, such as PQY, TAS, ATAI, FIT, CEE, and MAC, which are found to be the significant predictors of PDN [29,31,34,41,42]. The following sub-sections explain each factor.

2.1. Perceived Quality (PQY)

PQY shows the consumer’s overall assessment of a product’s quality. Shoppers place a high value on product quality, the credibility and trustworthiness of online sellers as indicators of high-quality merchandise, and constructive feedback from other consumers as a symbol of product superiority [16,17]. A study conducted by [15] in the shoe industry of Jakarta demonstrates that, when PQY is high, consumers are more motivated to purchase a product. This highlights the role of PQY as a major enabler of consumer PDN. Similarly, Ref. [43] investigated the potential for AI to replace human customer service; they suggest that communication quality is a key component of overall PQY, and concerns about privacy risks impact the likelihood that consumers will use AI-driven services. The influence of PQY extends into the domain of marketing analytics as well. Better big data marketing analytics improve a firm’s marketing capabilities, ultimately enhancing market performance [44]. In the assessment of [45], when firms perceive their analytics as high quality, they are more agile in their decision-making processes. Relatedly, Ref. [27]’s study found that factors such as reliability, usability, and overall performance (i.e., PQY) are important for user acceptance. Scholars like [46] add that high AI quality—when perceived positively by customers—correlates with enhanced CEE, mainly when moderated by individual preferences toward AI.

2.2. Technology Attitudes (TAS)

TAS represents individuals’ overall beliefs and feelings toward technology. Individuals strongly believe that their positive TAS suggests that they can solve their problems using technology and open new avenues for their survival [18,19]. Individuals often view technology as a catalyst for personal and societal progress, frequently feeling that it enables them to accomplish more each day [8]. According to [47]’s study, favorable consumer TAS significantly boosts the acceptance of tech-based hotel innovations. Therefore, it proves customer satisfaction. Consumers’ attitudes toward the presence of AI in product and service descriptions can mediate the connection between emotional trust and purchase intentions [48].

TAS is a positive predictor of fashion students’ intentions [49]. An empirical study conducted by [50] demonstrates a positive connection between technology, teaching practices and attitudes. There is a substantial and positive contribution of public attitudes in the development of behavioral intentions [51,52]. In the empirical assessment of [53], both implicit and explicit attitudinal responses to new food technologies affect the familiarity and adoption of TAS.

2.3. Attitudes Toward Artificial Intelligence (ATAI)

ATAI measures customers’ overall judgments about AI by collating a range of perceptions (from negative to positive) regarding AI’s desirability, utility, and consequences for individuals and society [9,54]. According to [9]’s study, student attitudes toward AI significantly influence the uptake of innovative technologies in the digital tourism sector. In workplace situations, AI attitudes encompass factors such as perceived usefulness, and risk [10]. The empirical study of [8] suggests that positive consumer attitudes toward embedded AI smart speech recognition are positively associated with higher purchase intentions. TAS mediates the relationship between various antecedents and the actual usage of AI among professionals [55]. In the healthcare context, Refs. [30,56] demonstrate that the feelings of the general public and nursing professionals toward AI are massively affected by their underlying attitudes. Relatedly, AI literacy, an innovation mindset, and a robust measure of attitudes are essential in shaping career self-efficacy and overall engagement with AI in educational and professional contexts [29,57].

2.4. Fashion Involvement (FIT)

FIT represents the degree to which an individual is cognitively and emotionally engaged with fashion. This captures how fashion affects one’s identity and lifestyle and reflects the importance placed on fashion products [20,21]. A high individual FIT suggests frequent involvement in fashion and a strong interest in fashion trends and styles [58,59]. Researchers like [60,61] state that consumers with a higher FIT derive greater pleasure from fashion-related activities and tend to exhibit more impulse buying behavior. Similarly, the emotional gratification derived from fashion improves impulsive purchase tendencies among highly involved consumers. There is a dynamic connection between FIT and personal fashion identity [62]. In a broader context, FIT affects consumer responses to technologically curated fashion services. Consumers are more receptive to AI-curated fashion services, positively affecting their purchase intentions and PDN [63,64]. Ref. [65]’s study identify FIT as a key driver of women’s impulsive buying behaviors in retail footwear shopping [66].

2.5. Customer Experience (CEE)

CEE is a substantial and powerful enabler of customer satisfaction [67,68], and helps them to fulfil their dreams, goals, and needs [22,23]. According to [24], the store atmosphere and the quality of CEE positively affect PDN and customer satisfaction, mediated by the physical retail environment and buyer behavior. Corporate environmental sustainability with CEE management promotes a positive, sustainable CEE [69]. Ref. [40]’s study demonstrates that customer behavior and CEE influence PDN in an urban setting. In the critical assessment of [70], superior CEE, along with economic factors such as personal income, positively affects service purchase behaviors in airline firms. Ref. [71]’s study highlights that new technologies can transform and elevate CEE, improving engagement and satisfaction. Intelligent chatbots, as part of digital transformation initiatives, positively and substantially develop sustainable market environment and CEE [35].

2.6. Marketing Analytics Capability (MAC)

MAC represents a customer’s ability to systematically collect, integrate, and analyze diverse data sources, including seller behaviors and information regarding broader market trends. This capability enables customers to comprehend market changes [25]. MAC facilitates the adoption of AI and enhances firms’ competitive position in the manufacturing industry. The absorptive capacity and application of external knowledge are essential for developing MAC, which ultimately enhances PDN [26]. According to the empirical investigation of [44], the quality of big data analytics directly affects the overall marketing capabilities and perceived market performance. Likewise, in start-up environments, project management strategies contribute to harnessing digital marketing analytics for growth [72]. Building upon these studies, Ref. [44]’s study also maps the diverse proficiencies required in the marketing and technical domains and suggest that balanced skills enhance the potential of MAC.

2.7. Purchase Decision (PDN)

PDN represents a consumer’s reasoning and behavioral commitment toward buying a product or service [14,15]. It incorporates the expressed intention to make purchases via online platforms, the evaluated likelihood of seeing such purchases, and the overall willingness to buy from online stores [11,13]. Ref. [12]’s study employs complexity theory through fuzzy-set Qualitative Comparative Analysis (fsQCA) to establish that inbound digital marketing, when effectively integrated with other marketing variables, has a massive role in shaping PDN. In urban retail contexts, customer behavior and the quality of customer experience are central to the PDN process [40]. According to [39]’s study, PDN can be enhanced through interactive communication. A positive customer experience and a robust brand image can improve PDN and buying motivations [15,23]. In the study of [14], ethical AI builds consumer trust and efficiently targets advertising efforts to influence buying behavior positively.

As a result, in the domain literature, several constructs—such as PQY, technophobia, TAS, and technological experiences—predict ATAI [29,31,41,73]. Furthermore, the FIT, CEE, MAC and PDN are also correlated with various factors—such as ATAI, optimizing purchase, AI adoption, efficiency, user satisfaction, social experiences, virtual communities, consumer perceptions, consumer loyalty, and business intelligence—in various contexts [8,12,24,33,34,42,68,74,75,76].

However, the domain literature still has gaps that must be covered. For instance, the literature is deficient in providing an integrated framework that may incorporate the effects of PQY and TAS on ATAI while simultaneously combining the effects of ATAI on FIT, CEE, MAC, and PDN. Furthermore, FIT’s mediating and direct relationship between ATAI and PDN has yet to be explored, specifically in the presence of other constructs, such as PQY, TAS, CEE, and MAC. In addition, among Saudi Arabia’s customers who interact with AI in fashion retail stores, AI plays a significant role in recommending and guiding fashion products in the country [36,37,38].

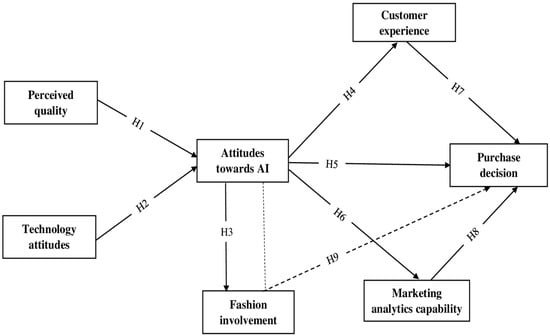

Hence, based on these gaps, i.e., practical knowledge and contextual gaps, the researcher developed a theoretical framework (see Figure 1) that integrates several constructs, such as PQY, TAS, ATAI, CEE, FIT, MAC, and PDN. More specifically, the framework demonstrates the predictive relevance of PQY and TAS toward ATAI, showing that consumers’ overall assessment of a product’s excellence and fashion trends, the prominence that shoppers place on product quality, and the credibility of online sellers are indicators of high-quality merchandise. These also demonstrate individuals’ overall beliefs and feelings toward technology and ATAI. Moreover, the proposed effects of ATAI on CEE, FIT, MAC, and PDN underline consumers’ impressions and satisfaction with a product or service, where AI reinforces these impressions. In the model, FIT represents the extent to which the individual is cognitively and emotionally engaged with fashion. At the same time, MAC represents the customer’s ability to systematically collect, integrate, and analyze diverse data sources regarding broader market trends. Finally, the PDN represents a consumer’s reasoning and behavioral commitment toward buying a product or service.

Figure 1.

Theoretical framework of the study. Source: Developed by the researcher. → = direct paths; ---> = indirect path.

TAM and Consumer Decision-Making Theory (CDMT) underpin the study framework. Specifically, TAM demonstrates individuals’ acceptance and use of technology, where PQY and TAS align with TAM and assist ATAI in fashion retail. According to [77]’s study, TAM shows the consumer’s perceptions of purchase intentions. Moreover, AI can be made more effective and profitable in e-commerce, where it focuses on consumer acceptance and usage of AI technologies in online shopping [78]. Similarly, TAM is used in several AI technologies in various industries, e.g., fashion, to predict behavioral intentions toward AI [79]. Relatedly, CDMT emphasizes that PDN and TAS contribute to the development of AI-driven MAC and CEE for PDN. A positive connection between consumer decision-making styles and fashion product involvement is revealed in consumer purchase decisions [80]. Specifically, in fashion companies, the consumer decision-making process expands the understanding of fashion buyer behavior [81,82]. Based on robust AI systems, this framework emphasizes that AI is a crucial tool and an integrated system of interrelated technologies that shape consumer cognition, emotion, and decision-making.

3. Hypotheses Development

3.1. Perceived Quality (PQY) and Attitudes Toward Artificial Intelligence (ATAI)

PQY is an important factor which positively enhances ATAI, specifically in retail dimension. Products with better quality, valuable services, and reliability encourage individuals to develop ATAI [27,46,83]. In the perception of [46,84], the development of ATAI is possible through PQY. Similarly, there is also a positive and significant role of factors such as risk, quality, and trust in developing the attitudes of customers towards buying the products [28]. In the study of [46], there is a positive association between the quality of AI performance and customer engagement and usage. Consumer readiness for AI adoption depends on constructs such as perceived usefulness, enjoyment, and technophobia, which can either reinforce or weaken the effect of quality perceptions on attitudes in the context of the fashion retail sector [31,54].

Consequently, the literature clearly shows the positive links between PQY and ATAI. However, to confirm these relationships in fashion retail stores in Saudi Arabia, the researcher proposed the following hypothesis:

H1.

Consumers with a positive PQY have a positive ATAI in fashion retail stores.

3.2. Technology Attitudes (TAS) and Attitudes Toward Artificial Intelligence (ATAI)

TAS is a positive enabler of ATAI; i.e., individuals with a positive TAS are more likely to develop favorable ATAI [85,86]. In different contexts, such as healthcare and education, greater AI endorsement is driven by efficiency and benefits [9,41,87]. Several domain researchers like [29,30,73] show the development of TAS through trust in AI or digital systems. According to numerous scholars, like [10,88,89], AI applications reinforce the idea that enhanced technological experiences shape ATAI.

The domain literature shows the positive contribution of TAS in the massive development of ATAI. However, its contribution requires further confirmation when integrated with other constructs, such as FIT, CEE, PDN, and MAC. Hence, we have the following hypothesis:

H2.

Consumers with a positive TAS have a positive ATAI in fashion retail stores.

3.3. Attitudes Toward Artificial Intelligence (ATAI), Fashion Involvement (FIT), Customer Experience (CEE), Purchase Decision (PDN), and Marketing Analytics Capability (MAC)

ATAI enhances consumers’ high FIT and shopping convenience [33,54]. Domain researchers like [17,64] recommend that AI and digital tools provide the consciousness and knowledge to the customers; thus, they make their decisions regarding PDN. Moreover, AI helps in finding the solutions for adopting sustainable and fashion practices. These also develop positive attitudes among customers towards shopping for fashionable products [58]. Trust and perceived control boost AI adoption in fashion and, ultimately, make human decision-making more rational [8,33]. Nevertheless, younger generations, i.e., Gen Z and Millennials, are more receptive to AI in fashion, though apprehensions over privacy and the over-reliance on AI remain factors that affect adoption [49,90]. The association between FIT and ATAI is theoretically defensible, as consumers with a high FIT actively seek better decision-support systems, trend-related information, and personalization. These are obviously provided by AI tools. Previous domain studies, such as [54], have claimed that highly involved fashion consumers are more motivated and inclined to use technological aids, which positively enhance product evaluation, trend discovery, and style matching. Likewise, consumers’ engagement in fashion shows their association with digital innovations, which ultimately improve their shopping experiences [91].

ATAI enhances CEE, predominantly with the support of AI-driven services, i.e., chatbots and virtual assistants. ATAI enhances CEE with the support of an increase in the acceptance of AI-powered interactions, which ultimately boost efficiency and confidence, create greater personalization, and also reduce waiting times [7,75,92]. Several scholars, like [42,93], suggest that AI chatbots positively affect user satisfaction where they offer in accuracy and timely responses in different contexts and industries, e.g., retail, tourism, and banking. Nevertheless, while AI-driven services improve convenience, CEE is affected by perceived communication, quality, privacy concerns, and trust, with a few consumers favoring human interaction over AI due to a lack of perceived empathy [35,43,94]. According to [7]’s study, fears of over-reliance and privacy risks affect CEE, even among those with a positive ATAI [43]. Similarly, when AI systems personalize suggestions and resolve queries, they substantially affect customer engagement and loyalty. These ultimately reinforce the connection between ATAI and CEE [71,95,96].

ATAI significantly affects consumer PDN. Consumers with a positive ATAI probably depend on AI-based recommendations, personalized advertisements, and autonomous decision-making systems [94,97,98]. According to [19,99], AI-powered advertisements affect CEE, specifically in online retail, where targeted marketing strategies based on AI analytics positively affect ATAI and purchasing behaviors. In the study of [14], ethical AI algorithms have an enormous reputation in developing satisfaction among customers; thus, they make their intentions and attitudes to engage in shopping. In the same manner, AI transparency reduces customers’ hesitations to purchase fashionable products [8,100]. According to [8]’s study, AI technologies, e.g., smart speech recognition, are crucial in developing consumer confidence in AI, specifically in generational cohorts.

ATAI has a significant effect on MAC, leading to improved PDN. A positive ATAI development significantly enhances the acceptance and implementation of marketing analytics tools and improves customer segmentation [101]. The rise of AI-enabled conversational tools, e.g., ChatGPT-4, has redefined MAC by enabling personalized customer interactions and automating content generation. These growing trends of AI positively affect digital marketing [102,103]. According to [104], marketers’ trust in AI systems potentially limits their willingness to depend on AI-powered analytics. AI can lead to a greater understanding of consumers, enabling greater customer involvement, engagement, and marketing competence [34,105]. MAC is a retailer-side construct; it can be affected by ATAI, which regulates the quality, relevance, and accuracy of AI-driven consequences that consumers experience. Scholars in the domain, such as [105,106], demonstrate that retailers who possess a robust attitude toward AI systems and a strong MAC generate more predictions and interpretations. In the same aspect, a seminal work of [107] demonstrates that consumers’ evaluations of AI are developed by technology itself and also through analytics performance, which assist in driving decisions. Thus, despite creating from different sides of the exchange, MAC is an essential factor that is positively predicted by ATAI.

This literature confirms the role of customers’ ATAI in influencing several constructs, such as FIT, CEE, PDN, and MAC. However, these associations, integrated in the presence of PQY and TAS, underpinning two theories—TAM and CDMT—have disappeared from the existing literature. Hence, based on this deficiency, the researcher proposed the following hypotheses:

H3.

Consumers’ ATAI positively affects FIT in fashion retail stores.

H4.

Consumers’ ATAI positively affects CEE in fashion retail stores.

H5.

Consumers’ ATAI positively affects PDN in fashion retail stores.

H6.

Consumers’ ATAI positively affects MAC in fashion retail stores.

3.4. Customer Experience (CEE) and Purchase Decision (PDN)

CEE positively shapes PDN. There are direct connections between consumer perceptions, emotions, and satisfaction levels. A positive CEE, whether in physical or digital environments, reinforces the development of purchase intentions [70,108]. In online retail, personalized interactions and post-purchase engagement promote higher conversion rates and repeat purchases [22,109]. Several factors, e.g., brand image, service quality, and product differentiation, positively affect CEE and PDN [15,23]. In the assessment of [69], environmental responsibility and sustainable business practices are the core components of CEE and PDN [69]. However, social experiences, e.g., brand ambassadors and virtual communities, nurture consumer perceptions and affect purchasing behavior [39,68]. CEE can be enhanced through service excellence, technological innovation, and emotional engagement to boost consumer loyalty and affect purchase outcomes [24,40].

Consequently, it is crystal clear that CEE convinces customers to make a PDN. To confirm these in fashion retail stores in Saudi Arabia, the researcher formulated the following hypothesis:

H7.

CEE positively affects PDN in fashion retail stores.

3.5. Marketing Analytics Capability (MAC) and Purchase Decision (PDN)

MAC is a massive and positive predictor of PDN. According to several researchers, including [44,45], the quality of big data analytics directly improves MAC, which consequently enhances decision-making agility and marketing performance. The connections between customer psychology and marketing strategies are bridged through advanced marketing analytics [32]. The transparency in AI-driven marketing strategies poses challenges where service descriptions and the presence of AI in products negatively impact purchase intentions [48]. The empirical assessments of [13] demonstrate that consumer behavior models and predictive analytics play a massive and vital role in refining PDN. Furthermore, in the context of commerce and agriculture, digital marketing, the integration of AI, and big data analytics have several significant implications and contributions to improving decision-making competence [110]. Likewise, performance management and business intelligence positively affect strategic marketing decisions and empower firms to optimize customer engagement and marketing investments [77], and, furthermore, inbound digital marketing strategies, as complexity theory accentuates the role of digital engagement in shaping consumer decisions [12].

As a result, the MAC is predicted by ATAI, but it also is a predictor of PDN. To confirm its dual roles, the researcher developed the following hypothesis:

H8.

MAC positively affects PDN in fashion retail stores.

3.6. Fashion Involvement (FIT) as Mediator

FIT is the extent of personal relevance and interest in fashion and acts as a bridge between consumer attitudes and actual purchase behavior [62]. FIT mediates the association between ATAI and PDN, enhancing consumers’ experiences with AI-driven fashion retail. ATAI in fashion retail is shaped by various factors, e.g., knowledge, self-concept, and brand engagement, which affect purchase intention [111]. Likewise, the effect of AI-enabled services in online fashion retail is increasing, demonstrating that consumer intentions to adopt these technologies are influenced by FIT [112]. Hedonic consumption tendencies enhance FIT by engaging consumers in AI and PDN [60,61]. The link between fashion consciousness and purchase involvement is meditated by materialism [113]. Similarly, in the study of [59], product involvement acts as a significant mediator between personal values and ethical fashion purchase intentions. Moreover, AI-enhanced personalization in luxury fashion boosts customer relationships, affecting PDN, mediated by brand loyalty [21]. Relatedly, consumers’ readiness for AI in fashion closely aligns with their involvement with fashion [54]. Furthermore, fashion influencers contribute significantly to shaping AI-driven PDN, as attitudes toward influencers mediate the effect of AI on fashion-buying behavior [114].

Consequently, the literature offers the indirect role of FIT between ATAI and PDN and the consistent role of FIT in association with ATAI and PDN. Hence, based on this, the researcher proposed the following hypothesis:

H9.

FIT mediates the relationship between ATAI and PDN in fashion retail stores.

4. Methods

4.1. Survey Strategy and Respondents of the Study

This study examines consumers’ interaction with AI systems in the online fashion journey. Thus, the role of system-level systems, such as virtual try-on systems, marketing analytics systems, and AI-driven systems, assists in shaping customers’ perceptions, attitudes, and decision processes. Taking this into consideration, this study employed quantitative methods because they provide measurable and unbiased data and massively assist in predicting trends and behaviors [115]. This method also has massive prominence because researchers support businesses and policymakers in making data-driven decisions [116]. Several scholars, like [24,33,35,40,42,96], have used this strategy to explore problems in the domain literature, specifically of PDN, ATAI, technology aspects, and customer perception in terms of online shopping behaviors.

With regard to respondents of the study, the researcher collected data from customers who use AI chatbots, virtual try-ons, and smart mirrors when shopping at fashion retail stores in Saudi Arabia. They have direct experience with AI-driven shopping technologies. The tools associated with AI boost personalization, improve decision-making, and enhance purchase behavior with the enormous FIT [117,118]. They understand the positivity of their ATAI, which is crucial in maintaining their PQY and technology acceptance of their shopping experiences [119].

4.2. Instrument and Data Collection

This study employed a survey questionnaire administered in English to gather the cross-sectional data. Before collecting the large-scale data, the researcher made a pre-test of the survey tool by conducting a pilot study (collected 27 cases), a tool used by researchers to confirm reliability and validity [120]. The researcher ensured reliability by observing the internal consistency of the survey items through Cronbach’s alpha and the relationship of the items through initial factor loadings. As a result, the researcher found overall alpha, individual factors’ alpha, and factor loadings values greater than 0.70, which are acceptable and adequate scores. In addition, the researcher confirmed the face validity of the survey by getting respondents’ feedback regarding format, language barriers, and difficulties in understanding and filling out the survey forms. Moreover, the researcher obtained expert opinions on the study from field researchers and feedback from two university professors. One was a professor of statistics who is well-known in SEM analysis, and the other was an expert in digital technology and marketing who deals with AI and digital marketing tools. Hence, after minor modifications, the researcher moved ahead with reliable and valid survey tools for gathering data.

This study employed an online approach to data collection from customers using AI and chatbots, which helps improve CEE, boost retention, and gain a competitive edge by making real-time data-driven decisions [121]. The researcher emailed the survey forms as online questionnaire links through LinkedIn pages of fashion stores, X platform, and WhatsApp. The data were collected from January 2025 to June 2025 by targeting consumers with experience in fashion retail online and AI-enabled services. The survey took almost six months. The researcher used convenience sampling, which is widely used due to its convenience and cost-effectiveness [122]. In the AI context of chatbot data collection, this technique is best and offers swift insights for optimization [123]. The researcher respected the ethical values of the respondents, ensuring the privacy of their data and properly communicating the aims and objectives of the study. After their agreement to contribute to the study on a voluntary basis was attained, the survey was sent. Initially, the researcher sent 580 surveys, of which 346 were received back, a response rate of 59%. After data cleaning, 344 valid samples were utilized for the final results.

The researcher examined sample size adequacy using G*Power 3 software [124,125]. In this study, the researcher used five main predictors with five regressions to observe the effect size. As a result, the software suggested 138 samples for the study’s SEM analysis. Hence, this study’s sample size (344) is sufficient.

4.3. Common Method Bias (CMB)

Common method bias (CMB) is a significant and frequent concern in empirical and quantitative studies that use survey questionnaires, since responses may be influenced by common rater effects, social desirability, and the effects of measurement context, leading to misleading findings [126]. To address these concerns, the researcher used two essential remedies, i.e., statistical and procedural CMB, as suggested by [126]. More clearly, from a statistical CMB perspective, the researcher used Harman’s Single Factor fit indices of the projected model, which is a better fit for the single factor, as the variance extracted for one factor is observed as 39.773% (<50%) [123]. Furthermore, procedural CMB is ensured by maintaining the respondents’ privacy in their responses. Thus, both aspects suggest that CMB is not an issue in this study.

4.4. Measures

The researcher adopted three items from [18]’s survey to measure the TAS factor. The researcher used five items taken from [54] to gauge ATAI. The PQY factor was measured using four items by [16,17]. Similarly, the PDN construct was assessed using four items adopted from the study of [11]. The researcher borrowed six items from [25] to determine the MAC factor. To measure the FIT, the researcher adopted twelve items from the study of [20]. Finally, CEE was assessed using five items borrowed from the study of [67] (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Measurement scales.

5. Results

5.1. Respondents’ Profiles

The respondents’ profile indicates a majority of females (n = 199, 57.85%) compared to males (n = 145 or 42.15%). The age factor suggests that a majority of respondents (n = 118 or 34.30%) are 25–34 years old, while only 6.98% (n = 24) are 55 years of age or older. The income level indicator suggests that a majority of respondents (n = 210 or 61.0%) have a medium income, while only 13.08% (n = 45) have a low income. A majority of respondents (n = 218 or 63.37%) possess a Bachelor’s degree and only 3.78% (n = 13) held a PhD degree. In the same way, regarding shopping behaviors, a majority of respondents (n = 153 or 44.48%) were occasional shoppers, while only 20.06% (n = 69) were customers who made rare purchases. Concerning the digital experience, a majority of respondents (n = 168 or 48.83%) had advanced expertise, while a minority (n = 66 or 19.19%) had beginning-level experience. Furthermore, a majority of customers prefer both online and offline shopping (n = 186 or 54.07%). Finally, the fashion interest level suggests that a majority of respondents (n = 163 or 47.39%) had a medium level of interest, while only 22.09% (n = 76) had a high level of interest (see details in Table 2).

Table 2.

Respondents’ profile (n = 344).

5.2. Measurement Model

In this study, the researcher applied an SEM analysis using AMOS version 26.0 software because it is the best and most robust technique, with great power and judgment validity [127]. Initially, the reliability and validity of the study were ensured when the majority of the items appeared to be within the acceptable scores (>0.70) and ranges, i.e., from 0.753 (FIT12) to 0.876 (TAS1). Conversely, MAC5, FIT4, FIT8, FIT11, and CEE4 items were deleted due to low loadings. Importantly, the deleted items do not compromise the validity (content or face) as the remaining or loaded items fully capture the original scales. In addition, the deleted items’ weak loadings indicate a minor conceptual misalignment or reduced relevance in this study, rather than a problem with the constructs themselves.

Moreover, to address multicollinearity, the researcher applied the variance inflation factor (VIF), as a single data collection method (i.e., survey questionnaire) was used in this study. Thus, VIF appeared with a value of less than 0.5 for all the items, which ensured no problem of multicollinearity [128] (see Table 3). Moreover, the composite reliability (CR) appeared to be above the acceptable values (>0.70) [129], ranging from 0.898 (TAS) to 0.937 (FIT), and the average variance extracted (AVE) showed acceptable scores (>0.50), ranging from 0.678 (FIT) to 0.747 (TAS) [129]. Concerning the internal consistency of the items, the values of Cronbach’s alpha are found to be above the required values (>0.70) [130], ranging from 0.798 (PDN) to 0.898 (FIT). Lastly, the discriminant validity matrix’s diagonal values demonstrate that all factors touched their required criteria with values that are greater than the non-diagonal scores [130] (Table 4).

Table 3.

Measurement model.

Table 4.

Reliability and validity analysis.

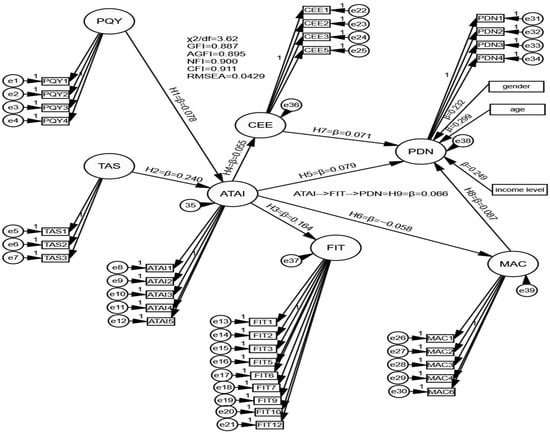

5.3. Structural Model

Model fitness—The researcher ensured the model’s fitness before assessing the hypotheses. In this way, the valuable fit indices—i.e., chi-square (χ2/df = 652), GFI (0.887), AGFI (0.895), NFI (0.900), CFI (0.911), and RMSEA (0.0429)—ensured the good fitness of the model with the data [131] (Table 5). Moreover, the researcher applied three main demographic factors, i.e., gender, age and income level, as control variables. The addition of control variables helps to clarify the results and show how the factors are associated [132]. For instance, if any researcher fails to include control variables, their results may increase the risk of p-value hacking and a discrepant relationship between bivariate and multivariate analyses [133]. Hence, the researcher included these factors (see Figure 2).

Table 5.

Model fit estimations.

Figure 2.

Path model. Source: Calculated by the researcher.

Hypotheses assessment—The researcher employed SEM analysis, conducting a path analysis in AMOS, a software widely used for assessing hypothesized paths [130]. The results of the study suggest positive effects of PQY and TAS on ATAI, supporting H1 (β = 0.078; CR = 3.332; p < 0.01) and H2 (β = 0.240; CR = 6.906; p < 0.01). The study confirmed the effects of ATAI on FIT, CEE, and PDN. Hence, H3 (β = 0.164; CR = 3.519; p < 0.01), H4 (β = 0.055; CR = 2.673; p < 0.01), and H5 (β = 0.079; CR = 3.022; p < 0.01) are supported. On the other hand, the effect of ATAI on MAC is negative, contradicting H6 (β = −0.058; CR = 1.062; p > 0.01). Furthermore, there, CEE and MAC have positive effects on PDN, supporting H7 (β = 0.071; CR = 3.065; p < 0.01) and H8 (β = 0.087; CR = 3.225; p < 0.01). Finally, FIT mediates the connection between ATAI and PDN, supporting H9 (β = 0.066; CR = 2.050; p < 0.01) (see Table 6 and Figure 2).

Table 6.

Path co-efficient analysis.

6. Discussion and Conclusions

The study aimed to examine AI in fashion retail, showing how ATAI and PDN are affected by several variables in Saudi Arabia. The study’s findings suggest that PQY and TAS positively affect ATAI. These results are supported by several domain studies, such as [9,27,28,29,31,46,84,85], which confirmed these results earlier. According to the existing results, the customers of Saudi Arabia prefer high-quality products. This quality they usually ensure through AI and digital technology apps. Since these customers consider multiple factors and aspects in mind when shopping, they develop AI’s ability to make comparisons that align with their decision-making process. Furthermore, customers with positive attitudes toward technology regard AI as a valuable tool that promotes competence, problem-solving, and productivity, making them more open to AI-driven shopping experiences.

The results suggest positive effects of ATAI on FIT, CEE, and PDN. These results are consistent with the literature, in which several scholars have confirmed the positive associations between ATAI and FIT, CEE, and PDN [7,8,17,19,33,35,42,49,58,64,75,92,97]. These positive connections suggest that Saudi customers or online purchasers believe AI to be valuable and useful because it enhances their experiences and makes shopping easier. The ease of use of AI communications provides the convenience that enhances customers’ shopping motivation, boosting their confidence in finding suitable products and making rational purchasing decisions. Their positive involvement in AI and its substantial usage for shopping purposes will further encourage them to engage with technology and AI tools in shopping and marketing.

On the other hand, the results show a negative effect of ATAI on MAC, which is in contradiction with the domain literature [34,101,102,103,104,105]. This negative result suggests that Saudi Arabia’s online stores might not be able to change the attitudes of consumers due to not taking care of their preferences and demands. Based on the present findings, consumers may experience lower analytical engagement, trusting heavily on automatic ideas instead of evaluating substitutes. In the same way, AI-generated information may create cognitive overload, where too many algorithm-based options or comprehensive perceptions diminish consumers’ ability to process marketing information in the effective way [134]. These mechanisms suggest why a positive ATAI may not always develop a stronger MAC. Furthermore, strong consumer confidence in AI may inadvertently weaken perceived human- or retailer-driven MAC. Hence, online stores in Saudi Arabia often fail to meet customer preferences and overlook purchasing trends.

The study’s results confirm a positive effect of CEE on PDN. These results are supported by several scholars, like [22,23,24,68]. The results of the study demonstrate that customers in Saudi Arabia have a positive experience with AI chatbots. They have a strong belief in the information and knowledge provided by AI for retail stores, which diminishes their hesitation and confusion. These enhance and boost customers’ confidence in online shopping based on new fashion trends. Therefore, the CEE plays a substantial role in PDN, providing positive insights.

Furthermore, the results show that MAC has a positive role for PDN. Like others, these results concur with domain studies [12,13,32,48,110]. In the context of Saudi Arabian online stores, these thoroughly understand the preferences and choices of customers and tailor their behavior accordingly. They meet expectations, nurture engagement, and reinforce brand loyalty. Therefore, customers use their analytical approach to decide what to purchase or not.

Finally, the mediating role of FIT in the relationship between ATAI and PDN is reinforced by previous studies [21,54,59,113]. These results suggest that ATAI positively affects FIT, which also enhances the trends of PDN among Saudi Arabia’s online customers.

To sum up, the study’s overall conclusion suggests positive effects of PQY and TAS on ATAI. ATAI is a positive predictor of FIT, CEE, and PDN, but a negative predictor of MAC. Moreover, factors such as CEE and MAC positively affect PDN. Finally, FIT mediates the link between ATAI and PDN among Saudi customers who use AI chatbots, virtual try-ons, and smart mirrors when shopping at fashion retail stores.

7. Implications, Limitations, and Future Research Avenues

With regard to practical implications, the study’s findings help policymakers and planners bring about further transformations from physical store purchasing to online purchasing and increased business engagement in the fashion industry through technological advancements, specifically in AI developments. The study’s findings help remove traditional purchasing channels and mitigate the crisis of conventional commercial formats. The study helps develop strong AI systems that make shopping easier and foster positive attitudes and intentions among customers. The study findings will be useful in developing an integrated vision between the online and offline customer journey stages, specifically in fashion retail. In the fashion retail field, the study’s outcomes further provide a major approach through AI. The modes of purchase and decisions about purchase will be rational and convenient. The study’s findings assist customers in driving PDN and interacting with retail stores with a powered experience, i.e., virtual try-ons and smart mirrors, which further enrich customer involvement with fashion. On the other hand, high AI trust may diminish the influence of data-driven marketing tactics; brands should ensure that AI applications feel instinctive rather than invasive. In FIT, AI tools enhance customers’ engagement with fashion trends. This encourages shopping or purchasing behavior. Retailers adopt AI interfaces to diminish cognitive overload and provide transparent explanations for AI. Moreover, the study encourages Gen Z consumers to embrace immersive, AI-driven experiences. Thus, AI helps customers to make rational decisions to predict marketing perceptions.

Concerning the theoretical implications, the study validates TAM and CDMT in the context of Saudi Arabian fashion. The study confirmed the contribution of AI and technological advancement. This would further boost and encourage the customers to use e-commerce and AI applications to make their purchase of fashion products. This step of the customers would also enhance the motivation and profit for the industry along with the ease for customers. Moreover, the study contributes to consumer behavior theories by establishing ATAI as a core predictor of FIT, CEE, and PDN. However, inverse results between ATAI and MAC open new avenues for researchers and scholars to consider this in their studies. In addition, the study’s outcomes contribute to the literature on AI-driven retail experiences and consumer technology behavior in Saudi Arabia. Finally, the study deepens the domain literature and adds empirical insights.

The study has a few limitations, as it only applied quantitative methods with cross-sectional data. The study collected the data through a single source, i.e., an online survey questionnaire. The study’s theoretical framework is underpinned by TAM and CDMT, specifically in fashion retail stores in Saudi Arabia. The study framework comprised a few constructs: PQY, TAS, ATAI, CEE, FIT, MAC, and PDN. The study’s respondents were restricted to Saudi customers interacting with AI while shopping from fashion retail stores. In the model, product price and discount promotion are not included as control variables, as these are also key determinants of consumers’ purchase decisions. Finally, the outcomes of the study are based on a sample of 344.

In future research, other methods, such as qualitative and mixed methods, should be applied to longitudinal data. The framework of the study may be underpinned by other suitable theories, such as the TPB theory, as well as other constructs, e.g., entrepreneurial intention, technology transformation, sustainability, digital culture, and platforms. Other developing economies should be considered in future studies. Factors such as product price and discount promotions may be considered as control variables in future studies. Finally, the sample size should be increased to increase the validity of the results.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to Legal Regulations: Saudi Arabia’s PDPL Implementing Regulation (Articles 9(2), 15(3), and 30) because the research did not cause harm, did not involve sensitive personal information, and exclusively used anonymized data falling outside regulatory scope. Informed consent was obtained during the data collection period, detailing the purpose, data use, and risks, emphasizing voluntary participation. This reflects my commitment to ethical standards, prioritizing participant rights and welfare.

Informed Consent Statement

The author confirms that this study was conducted in accordance with ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all the participants involved in the study. They were fully informed of the research’s non-commercial academic purpose and assured that all collected organizational data would be kept confidential and anonymized.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Mohsin, S. The influence of AI-Driven personalization on consumer decision-making in E-commerce platforms. Al-Rafidain J. Eng. Sci. 2024, 2, 249–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankar, V. Marketing of technology-intensive products: An AI-driven approach. Mark. Strateg. J. 2025, 2, 100008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boaler, A.M.; Pankajakshi, R.; Saxena, S.; Kumar, P. Consumer Adoption of AI in Online Apparel Retail Purchases Using UTAUT2 Model. In International Conference on Data Analytics & Management; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2024; pp. 645–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Qiu, X. AI technology and online purchase intention: Structural equation model based on perceived value. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idrees, S.; Vignali, G.; Gill, S. Technological advancement in fashion online retailing: A comparative study of Pakistan and UK fashion e-commerce. Int. J. Econ. Manag. Eng. 2020, 14, 313–328. [Google Scholar]

- Mir-Bernal, P.; Guercini, S.; Sádaba, T. The role of e-commerce in the internationalization of Spanish luxury fashion multi-brand retailers. J. Glob. Fash. Mark. 2018, 9, 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gümüş, N.; Çark, Ö. The effect of customers’ attitudes towards chatbots on their experience and behavioural intention in Turkey. Interdiscip. Descr. Complex Syst. 2021, 19, 420–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arachchi, H.D.M.; Samarasinghe, G.D. Impact of embedded AI mobile smart speech recognition on consumer attitudes towards AI and purchase intention across Generations X and Y. Eur. J. Manag. Stud. 2024, 29, 3–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biriescu, S.; Olteanu, L. Technologies promoting the digital tourism economy and student attitudes towards artificial intelligence in tourism. In Green Wealth: Navigating Towards a Sustainable Future; Emerald Publishing: Leeds, UK, 2025; pp. 239–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Woo, S.E.; Kim, J. Attitudes towards artificial intelligence at work: Scale development and validation. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2024, 97, 920–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, V.T.; Pham, T.L. An empirical investigation of consumer perceptions of online shopping in an emerging economy: Adoption theory perspective. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2018, 30, 952–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayed, A.E. In terms of complexity theory via fsQCA: The role of inbound digital marketing in purchase decision making. Int. J. Technol. Mark. 2025, 19, 60–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masih, J.; Mathur, M.; Bhagwat, A.; Mishra, S.; Rokade, K. An evaluation of core factors of predictive analytics in influencing purchase decision of the consumers in e-business. In Artificial Intelligence, Internet of Things, and Society 5.0; Studies in Computational Intelligence; Hannoon, A., Mahmood, A., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; Volume 1113, pp. 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodgers, W.; Nguyen, T. Advertising benefits from ethical artificial intelligence algorithmic purchase decision pathways. J. Bus. Ethics 2022, 178, 1043–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saputro, D.A.; Elwisam, E.; Digdowiseiso, K. The effect of product differentiation, customer experience and product quality on the purchase decision of compass shoes in Jakarta. J. Syntax Admiration 2023, 4, 330–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeo, V.C.S.; Goh, S.K.; Rezaei, S. Consumer experiences, attitude and behavioral intention toward online food delivery (OFD) services. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2017, 35, 150–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Viñals, C.; Pretel-Jiménez, M.; Del Olmo Arriaga, J.L.; Miró Pérez, A. The influence of artificial intelligence on generation Z’s online fashion purchase intention. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2024, 19, 2813–2827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, L.D.; Whaling, K.; Carrier, L.M.; Cheever, N.A.; Rokkum, J. The media and technology usage and attitudes scale: An empirical investigation. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2013, 29, 2501–2511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksu, S.; Şener, B.Ç. Factors affecting consumers’ online purchasing attitudes towards ads guided by artificial intelligence. İmgelem 2024, 14, 373–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Cass, A. Fashion clothing consumption: Antecedents and consequences of fashion clothing involvement. Eur. J. Mark. 2004, 38, 869–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khamoushi Sahne, S.S.; Kalantari Daronkola, H. Enhancing loyalty in luxury fashion with AI: The mediation role of customer relationships. Asia-Pac. J. Bus. Adm. 2025, ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Anjaly, B. How to measure post-purchase customer experience in online retailing? A scale development study. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2017, 45, 1277–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latif, L.L.; Hasbi, I. Pengaruh customer experience dan brand image terhadap purchase decision. eProceedings Manag. 2021, 8, 209–241. [Google Scholar]

- Agustin, D.K.; Badi’ah, R. The influence of store atmosphere and customer experience on purchasing decisions through customer satisfaction as an intervening variable. J. Manag. Small Medium Enterp. 2025, 18, 659–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.A.; Agnihotri, R.; Islam, M.R.; Rahman, M.S.; Sumi, S.F. Marketing analytics capability, artificial intelligence adoption, and firms’ competitive advantage: Evidence from the manufacturing industry. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2022, 106, 240–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proença, M.; Martins, T.S. The role of absorptive capacity in the use of digital marketing analytics for effective marketing decisions. J. Mark. Anal. 2024, 12, 687–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakim, M.H.R.; Kho, A.; Santoso, N.P.L.; Agustian, H. Quality factors of intention to use in artificial intelligence-based aiku applications. ADI J. Recent Innov. 2023, 5, 72–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez-Suárez, M.; Delbello, L.; de Vega de Unceta, A.; Ortega Larrea, A.L. Factors affecting consumers’ attitudes towards artificial intelligence. J. Promot. Manag. 2024, 30, 1141–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnambs, T.; Stein, J.P.; Zinn, S.; Griese, F.; Appel, M. Attitudes, experiences, and usage intentions of artificial intelligence: A population study in Germany. Telemat. Inform. 2025, 68, 346–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smoła, P.; Młoźniak, I.; Wojcieszko, M.; Zwierczyk, U.; Kobryn, M.; Rzepecka, E.; Duplaga, M. Attitudes toward artificial intelligence and robots in healthcare in the general population: A qualitative study. Front. Digit. Health 2025, 7, 1458685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Tian, X.; Yang, J.; Luo, S. The influence of subjective knowledge, technophobia and perceived enjoyment on design students’ intention to use artificial intelligence design tools. Int. J. Technol. Des. Educ. 2025, 35, 333–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, R.; Lim, W.M.; Kumar, A.; Kumar, S. Marketing analytics: The bridge between customer psychology and marketing decision-making. Psychol. Mark. 2023, 40, 2588–2611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vatantzi, K.; Vlachvei, A.; Antoniadis, I. Consumer attitudes toward artificial intelligence in fashion. In Applied Economic Research and Trends. ICOAE 2023. Springer Proceedings in Business and Economics; Tsounis, N., Vlachvei, A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 1127–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behera, R.K.; Bala, P.K.; Rana, N.P.; Algharabat, R.S.; Kumar, K. Transforming customer engagement with artificial intelligence e-marketing: An e-retailer perspective in the era of retail 4.0. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2024, 42, 1141–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, S.; Lopes, J.M.; Trancoso, T. Customer experience in digital transformation: The influence of intelligent chatbots toward a sustainable market. Int. J. Innov. Sci. 2025, 17, 803–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mushayt, O.S.; Gharibi, W.; Armi, N. An e-commerce control unit for addressing online transactions in developing countries: Saudi Arabia—Case study. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 64283–64291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharthey, B.K. The influence of artificial intelligence on customer behavior. Am. J. Manag. Econ. Innov. 2024, 6, 26–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezmigna, I.; Alghizzawi, M.; Alqsass, M.; Abu-AlSondos, I.A.; Abualfalayeh, G.; Aldulaimi, S.H. The impact of AI tools on last-mile delivery in the e-commerce sector in Saudi Arabia. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Decision Aid Sciences and Applications (DASA), Manama, Bahrain, 11–12 December 2024; IEEE: Manama, Bahrain, 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handarkho, Y.D. Impact of social experience on customer purchase decision in the social commerce context. J. Syst. Inf. Technol. 2020, 22, 47–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fikri, M.; Silvianita, A. Influence of customer behaviour and customer experience on purchase decision of urban distro. Bus. J. J. Bisnis Sos. 2021, 7, 61–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buck, C.; Doctor, E.; Hennrich, J.; Jöhnk, J.; Eymann, T. General practitioners’ attitudes toward artificial intelligence–enabled systems: Interview study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2022, 24, e28916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.H.; Le, X.C. Artificial intelligence-based chatbots—A motivation underlying sustainable development in banking: Standpoint of customer experience and behavioral outcomes. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2025, 12, 2443570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.; Xing, X.; Duan, Y.; Cohen, J.; Mou, J. Will artificial intelligence replace human customer service? The impact of communication quality and privacy risks on adoption intention. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 66, 102900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haverila, M.J.; Haverila, K.C. The influence of quality of big data marketing analytics on marketing capabilities: The impact of perceived market performance! Mark. Intell. Plan. 2024, 42, 346–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haverila, M.; Haverila, K.; Gani, M.O.; Mohiuddin, M. The relationship between the quality of big data marketing analytics and marketing agility of firms: The impact of the decision-making role. J. Mark. Anal. 2024, 13, 162–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prentice, C.; Weaven, S.; Wong, I.A. Linking AI quality performance and customer engagement: The moderating effect of AI preference. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 90, 102629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, V.T.P.; Guo, R. The impact of consumers’ attitudes towards technology on the acceptance of hotel technology-based innovation. J. Hosp. Tour. Technol. 2021, 12, 624–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicek, M.; Gursoy, D.; Lu, L. Adverse impacts of revealing the presence of “artificial intelligence (AI)” technology in product and service descriptions on purchase intentions: The mediating role of emotional trust and the moderating role of perceived risk. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2025, 34, 2368040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnakumar, M. Adoption of AI tools in academic work: Exploring the intention of fashion students through technology acceptance model. NIFT J. Fash. 2024, 3, 40–60. [Google Scholar]

- Njiku, J.; Mutarutinya, V.; Maniraho, J.F. Developing mathematics teachers’ attitude towards technology integration through school-based lesson design teams. Int. J. Inf. Learn. Technol. 2023, 40, 485–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiolfi, S. How shopping habits change with artificial intelligence: Smart speakers’ usage intention. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2023, 51, 1288–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muwanga, R.; Ssekakubo, J.; Nalweyiso, G.; Aarakit, S.; Kusasira, S. Do all forms of public attitudes matter for behavioural intentions to adopt solar energy technologies (SET) amongst households? Technol. Sustain. 2024, 3, 96–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenbült, P.; de Vries, N.K.; Dreezens, E.; Martijn, C. Intuitive and explicit reactions towards ‘new’ food technologies: Attitude strength and familiarity. Br. Food J. 2008, 110, 622–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Lee, S.H.; Workman, J.E. Implementation of artificial intelligence in fashion: Are consumers ready? Cloth. Text. Res. J. 2020, 38, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emon, M.M.H.; Khan, T. The mediating role of attitude towards the technology in shaping artificial intelligence usage among professionals. Telemat. Inform. Rep. 2025, 17, 213–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, S.M.; El-Gazar, H.E.; Zoromba, M.A.; El-Sayed, M.M.; Atta, M.H.R. Sentiment of nurses towards artificial intelligence and resistance to change in healthcare organisations: A mixed-method study. J. Adv. Nurs. 2025, 81, 2087–2098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sayed, B.K.M.; El-Sayed, A.A.I.; Alsenany, S.A.; Asal, M.G.R. The role of artificial intelligence literacy and innovation mindset in shaping nursing students’ career and talent self-efficacy. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2025, 82, 1240–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolesnikov, M.; Popović Stijačić, M.; Keswani, A.B.; Brkljač, N. Perception of innovative usage of AI in optimizing customer purchasing experience within the sustainable fashion industry. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashmi, M.S.; Abdullah, F.; Anees, M. Impact of personal values on ethical fashion purchase intention: Mediating effect of product involvement. Pak. J. Psychol. Res. 2016, 31, 403–417. [Google Scholar]

- Haq, M.A.; Khan, N.R.; Ghouri, A.M. Measuring the mediating impact of hedonic consumption on fashion involvement and impulse buying behavior. Indian J. Commer. Manag. Stud. 2014, 5, 50–57. Available online: https://ijcms.in/index.php/ijcms/article/view/379 (accessed on 16 July 2025).

- Sari, M.D.K.; Yasa, N.N.K. The role of hedonic consumption tendency mediate the effect of fashion involvement on impulsive buying. Int. Res. J. Manag. IT Soc. Sci. 2021, 8, 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, R.; Desai, K. Fashion self-concept and fashion involvement: A mediation model. Int. J. Bus. Forecast. Mark. Intell. 2019, 5, 285–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cengiz, H.; Barin, A. How does body appreciation affect maladaptive consumption through fashion clothing involvement? A multi-group analysis of gender. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2025, 29, 94–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, E.; Yang, H. Effect of Chinese consumer characteristics on the attitude of AI-curated fashion service and the purchase intention of fashion products. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2025, 29, 20–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, P.; Silva, S.C.; Magro, M.; Dias, J.C. Beyond the myth: Understanding women’s impulsive retail footwear shopping. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2025, 53, 16–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, J.; Malik, P.; Singh, S. Expressing your personality through apparels: Role of fashion involvement and innovativeness in purchase intention. FIIB Bus. Rev. 2024, 13, 318–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.H.; Zinkhan, G. Determinants of perceived web site interactivity. J. Mark. 2008, 72, 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mani, L.A.; Ganisasmara, N.S.; Larisu, Z.U.L.F.I.A.H. Virtual community, customer experience, and brand ambassador: Purchasing decision on YouTube. J. Theor. Appl. Inf. Technol. 2022, 100, 2735–2755. [Google Scholar]

- Calza, F.; Sorrentino, A.; Tutore, I. Combining corporate environmental sustainability and customer experience management to build an integrated model for decision-making. Manag. Decis. 2023, 61, 54–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Umashankar, N.; Kim, K.H.; Bhagwat, Y. Assessing the influence of economic and customer experience factors on service purchase behaviors. Mark. Sci. 2014, 33, 673–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyer, W.D.; Kroschke, M.; Schmitt, B.; Kraume, K.; Shankar, V. Transforming the customer experience through new technologies. J. Interact. Mark. 2020, 51, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaniz, R.E.; Lindon, A.R.; Rahman, M.A.; Hasan, M.A.; Hossain, A. The impact of project management strategies on the effectiveness of digital marketing analytics for start-up growth in the United States. Inverge J. Soc. Sci. 2025, 4, 8–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenthaler, U. Extremes of acceptance: Employee attitudes toward artificial intelligence. J. Bus. Strateg. 2020, 41, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.J. Customer attitude to artificial intelligence features: Exploratory study on customer reviews of AI speakers. Knowl. Manag. Res. 2019, 20, 25–42. [Google Scholar]

- Murillo, E.; Sádaba, T.; Mir-Bernal, P.; Terán-Bustamante, A.; López-Sánchez, O. Internal branding processes in a fashion organization: Turning employees into brand ambassadors. Mercados Negoc. 2024, 25, 3–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanvir, O.; Adeel, R.; Masood, K. Role of data analytics, business intelligence, and performance management in enhancing strategic marketing decision-making. Qlantic J. Soc. Sci. 2024, 5, 445–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.J.; Gam, H.J.; Banning, J. Perceived ease of use and usefulness of sustainability labels on apparel products: Application of the technology acceptance model. Fash. Text. 2017, 4, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.E.; Biswas, S. Technology acceptance model for understanding consumer’s behavioral intention to use artificial intelligence-based online shopping platforms in Bangladesh. SN Bus. Econ. 2024, 4, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, S.; Kaye, S.A.; Oviedo-Trespalacios, O. What factors contribute to the acceptance of artificial intelligence? A systematic review. Telemat. Inform. 2023, 77, 101925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, H.H.; Sauer, N.E.; Becker, C. Investigating the relationship between product involvement and consumer decision-making styles. J. Consum. Behav. 2006, 5, 342–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Hwang, J. Factors affecting the fashion purchase decision-making of single Koreans. Fash. Text. 2019, 6, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, N.; Gosnay, R.M. Developing a consumer decision-making process (DMP) model fit for overtly sustainable fashion companies. In The Palgrave Handbook of Consumerism Issues in the Apparel Industry; Kaufmann, H.R., Panni, M.F.A.K., Vrontis, D., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 105–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Bai, X.; Ma, Z. Consumer reactions to AI design: Exploring consumer willingness to pay for AI-designed products. Psychol. Mark. 2022, 39, 2171–2183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, F.; Zhang, X. Artificial intelligence or human: When and why consumers prefer AI recommendations. Inf. Technol. People 2025, 38, 279–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrat, D. Attitude towards artificial intelligence in a leadership role. In Proceedings of the 21st Congress of the International Ergonomics Association (IEA 2021), Online, 13–18 June 2021; Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems. Black, N.L., Neumann, W.P., Noy, I., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 223, pp. 811–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Woo, S.E. Who likes artificial intelligence? Personality predictors of attitudes toward artificial intelligence. J. Psychol. 2022, 156, 68–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selamat, E.M.; Sobri, H.N.M.; Hanan, M.F.M.; Abas, M.I.; Ishak, M.F.M.; Azit, N.A.; Abidin, N.D.I.Z.; Hassim, N.H.N.; Ahmad, N.; Rusli, S.A.S.S.; et al. Physicians’ attitude towards artificial intelligence in medicine, their expectations and concerns: An online mobile survey. Malays. J. Public Health Med. 2021, 21, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latikka, R.; Bergdahl, J.; Savela, N.; Oksanen, A. AI as an artist? A two-wave survey study on attitudes toward using artificial intelligence in art. Poetics 2023, 101, 101839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadrovskaia, M.; Porksheyan, M.; Petrova, A.; Dudukalova, D.; Bulygin, Y. About the attitude towards artificial intelligence technologies. In Proceedings of the E3S Web of Conferences, International Scientific and Practical Conference “Environmental Risks and Safety in Mechanical Engineering” (ERSME-2023), Rostov-on-Don, Russia, 1–3 March 2023; EDP Sciences: Rostov-on-Don, Russia, 2023; Volume 376, pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yashashwini, A. Unveiling the role of artificial intelligence and its impact on consumer buying behaviour in online fashion retail: A comprehensive study. RVIM J. Manag. Res. 2024, 16, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh, H.; Wojdyla, W.; Van Dyk, C.; Yang, Z.; Chi, T. Transparent Threads: Understanding How US Consumers Respond to Traceable Information in Fashion. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Pan, R.; Xin, H.; Deng, Z. Research on artificial intelligence customer service on consumer attitude and its impact during online shopping. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2020, 1575, 012192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, C.; Wang, Y.; Cheng, Y. Does artificial intelligence satisfy you? A meta-analysis of user gratification and user satisfaction with AI-powered chatbots. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2024, 40, 613–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nica, E.; Sabie, O.M.; Mascu, S.; Luţan, A.G. Artificial intelligence decision-making in shopping patterns: Consumer values, cognition, and attitudes. Econ. Manag. Financ. Mark. 2022, 17, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolescu, L.; Tudorache, M.T. Human–computer interaction in customer service: The experience with AI chatbots—A systematic literature review. Electronics 2022, 11, 1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebaietaka, T. The Use of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in Enhancing Customer Experience. Master’s Thesis, Vytautas Magnus University, Kaunas, Lithuania, 2024. Available online: https://portalcris.vdu.lt/server/api/core/bitstreams/4405254e-365a-4700-853d-38cc86be67b5/content (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Pticek, M.; Dobrinic, D. Impact of artificial intelligence on purchasing decisions. In Proceedings of the 47th International Scientific Conference on Economic and Social Development, Prague, Czech Republic, 14–15 November 2019; Konecki, M., Kedmenec, I., Kuruvilla, A., Eds.; Economic and Social Development (ESD), Varazdin Development and Entrepreneurship Agency (VADEA): Prague, Czech Republic, 2019; pp. 80–90. Available online: https://esd-conference.com/publications-archive (accessed on 2 June 2025).

- Sharma, S.; Islam, N.; Singh, G.; Dhir, A. Why do retail customers adopt artificial intelligence (AI) based autonomous decision-making systems? IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2022, 71, 1846–1861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jangra, G.; Jangra, M. Role of artificial intelligence in online shopping and its impact on consumer purchasing behaviour and decision. In Proceedings of the 2022 Second International Conference on Computer Science, Engineering and Applications (ICCSEA), Gunupur, India, 8 September 2022; IEEE: Gunupur, India, 2022; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyari, H.; Garamoun, H. The effect of artificial intelligence on end-user online purchasing decisions: Toward an integrated conceptual framework. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twum, K.K.; Yalley, A.A. Marketing analytics acceptance: Using the UTAUT, perceived trust, personal innovativeness in information technology and user attitude. J. Sci. Technol. Policy Manag. 2024, 16, 1271–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanmugam, G.; Rajendran, D.; Thanarajan, T.; Murugaraj, S.S.; Rajendran, S. Artificial intelligence as a catalyst in digital marketing: Enhancing profitability and market potential. Ingénierie Systèmes D’information 2023, 28, 1627–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, V.M. Does ChatGPT change artificial intelligence-enabled marketing capability? Social media investigation of public sentiment and usage. Glob. Media China 2024, 9, 101–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, Y.K.; Wang, Y. Guest editorial: Artificial intelligence for B2B marketing: Challenges and opportunities. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2022, 105, 109–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davenport, T.; Guha, A.; Grewal, D.; Bressgott, T. How artificial intelligence will change the future of marketing. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2020, 48, 24–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wedel, M.; Kannan, P.K. Marketing analytics for data-rich environments. J. Mark. 2016, 80, 97–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, A.M.; Moura, J.A.B.; Costa, E.D.B.; Vieira, T.; Landim, A.R.; Bazaki, E.; Wanick, V. Customer models for artificial intelligence-based decision support in fashion online retail supply chains. Decis. Support Syst. 2022, 158, 113795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasermoadeli, A.; Ling, K.C.; Maghnati, F. Evaluating the impacts of customer experience on purchase intention. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2013, 8, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, S.; Hair, N.; Clark, M. Online customer experience: A review of the business-to-consumer online purchase context. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2011, 13, 24–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannakopoulos, N.T.; Terzi, M.C.; Sakas, D.P.; Kanellos, N.; Toudas, K.S.; Migkos, S.P. Agroeconomic indexes and big data: Digital marketing analytics implications for enhanced decision making with artificial intelligence-based modeling. Information 2024, 15, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samala, N.; Singh, S. Millennial’s engagement with fashion brands: A moderated-mediation model of brand engagement with self-concept, involvement and knowledge. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2019, 23, 2–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaman, M.; Mohamed Jasim, K.; Hasan, R.; Akter, S.; Vrontis, D. Understanding customers’ intentions to use AI-enabled services in online fashion stores—A longitudinal study. Int. Mark. Rev. 2025, 42, 604–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talaat, R.M. Fashion consciousness, materialism and fashion clothing purchase involvement of young fashion consumers in Egypt: The mediation role of materialism. J. Humanit. Appl. Soc. Sci. 2022, 4, 132–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magano, J.; Au-Yong-Oliveira, M.; Walter, C.E.; Leite, Â. Attitudes toward fashion influencers as a mediator of purchase intention. Information 2022, 13, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehalwar, K.S.S.N.; Sharma, S.N. Exploring the distinctions between quantitative and qualitative research methods. Think India J. 2024, 27, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilcher, N.; Cortazzi, M. ‘Qualitative’ and ‘quantitative’ methods and approaches across subject fields: Implications for research values, assumptions, and practices. Qual. Quant. 2024, 58, 2357–2387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqahtani, M.; Alqahtani, K. Artificial intelligence techniques in e-commerce: The possibility of exploiting them in Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Eng. Manag. Res. 2022, 12, 152–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]