Abstract

As organizations become increasingly projectified, safeguarding the resilience of project professionals and teams emerges as a critical organizational challenge. Adopting a systems lens, we investigate how agile mindsets and agile practices function as systemic antecedents of resilience at the individual and team levels. Eleven semi-structured interviews with experienced project managers, product owners, and team members from diverse industries were analyzed through inductive thematic coding and system mapping. The findings show that mindset supplies psychological resources—self-efficacy, openness and a learning orientation—while practices such as team autonomy, iterative delivery and transparent communication provide structural routines; together they trigger five interlocking mechanisms: empowerment, fast responsiveness, holistic team dynamics, stakeholder-ecosystem engagement and continuous learning. These mechanisms reinforce one another in feedback loops that boost a project system’s adaptive capacity under volatility. The synergy of mindset and practices is especially valuable in hybrid or traditionally governed projects, where cognitive agility offsets structural rigidity. This study offers the first multi-level, systems-based explanation of agile antecedents of resilience and delivers actionable levers for executives, transformation leaders, project professionals, and HR specialists aiming to sustain talent performance in turbulent contexts.

1. Introduction

Adversities are a constant reality for project professionals, stemming from uncertainty, excessive workloads, time pressures, and the risk of burnout [1,2]. The growing dependence on projects has resulted in the neglect of project professionals’ well-being [3], while the projectification of the workplace often entails severe negative consequences for those affected [1]. Simultaneously, global demand for project talent is rising [4]. Hence, resilience—the capability to adapt positively to substantial adversity [5]—is imperative in project management practice.

Projectified workplaces constitute socio-technical systems [6] in which individuals, teams and governance mechanisms represent interconnected elements bounded by organizational structures and continuously influenced by an external environment. In line with General Systems Theory [7] and the literature on complex adaptive systems [8,9], we view resilience not as a property of a single actor but as an emergent characteristic of the system as a whole, produced through feedback loops across hierarchical levels. Understanding how such feedback can be intentionally shaped is therefore critical.

An exploration of the agile approach, which is gaining traction far beyond software, naturally raises the question of its potential to act as a systemic antecedent of resilience. The agile approach comprises iterative cycles and incremental development in which self-organizing, cross-functional teams collaborate closely with customers [10,11]. Reported people-related benefits include higher job satisfaction [12] and motivation [13], as well as lower emotional exhaustion and reduced work-related stress levels [14]. That said, it is important to distinguish between agile practices—team autonomy, team diversity, iterative–incremental development, and agile communication [15]—and an agile mindset, i.e., values and beliefs that embrace change, collaboration and continuous learning [16]. Without an agile mindset, the practices themselves rarely yield sustained benefits [17,18]. Both constructs may thus function as systemic resources or mechanisms that enable resilience [5].

This study addresses four gaps. First, empirical research exploring the connection between agile practices or mindsets and individual or team resilience is extremely limited. At the same time, scholars have called for examining the effects of agile project management on stakeholder welfare [19], with particular attention to project employees [14]. It is clear that resilience in the project management profession is of great importance [20,21]. Second, the agile mindset remains under-researched, with only a few scholars addressing it directly. However, it has been gaining increased attention recently, as evidenced by emerging studies [16,22,23,24]. Third, resilience research, especially in project management is predominantly single-level and, in general, multi-level dynamics of resilience are still underexplored, only recently gaining research attention, offering various promising avenues for further study [25,26]. Fourth, most project management studies tend to treat resilience primarily as a process or tool for managing risk and handling crises [27,28]. For example, when examining resilience at the project level [29], it is often not given enough attention as a complex systems phenomenon deeply rooted in lived human experience. By adopting an explicit systems-theory perspective, we seek to illuminate how agile resources flow across levels and generate emergent resilience in projectified organizations.

Practically, such insight is timely: as projectification intensifies and demand for project talent grows, organizations must cultivate sustainable, people-centred ways of working. Our inquiry is grounded in a pragmatic, practice-oriented epistemology [30]: project management is not merely descriptive but prescriptive, aimed at actionable solutions.

Finally, projectified organizations now operate under escalating climate volatility and ESG-driven scrutiny. Ensuring the human sustainability of project workforces—that is, the long-term ability of people to thrive cognitively, emotionally, and physically while delivering project outcomes—becomes a board-level priority equal to financial performance. We therefore explore agility-enabled resilience not only as a performance booster, but as a systemic capability that preserves talent sustainability in turbulent socio-ecological contexts.

Accordingly, we pose three research questions (RQs):

RQ1: How does an agile mindset foster resilience at both the individual and team levels in projectified environments?

RQ2: How do agile practices contribute to resilience for individuals and teams in projectified environments?

RQ3: What key factors enable the agile mindset and agile practices to serve as systemic antecedents of resilience in project settings?

In summary, the aim of this study is to develop a multi-level, systems-based explanation of how an agile mindset and agile practices function as antecedents of individual and team resilience in projectified organizations, thereby providing actionable guidance for executives, transformation leaders, project professionals, and HR specialists who seek to build sustainable, people-centred project organizations.

Section 2 reviews the relevant literature, beginning with systems-theory foundations and progressing to resilience and agility. Section 3 outlines the multi-level qualitative methodology. Section 4 presents the results, mapped to system levels. Section 5 discusses findings through a systems lens and highlights theoretical and practical implications. Section 6 concludes with limitations and avenues for future research.

2. Theoretical Background and Literature Review

2.1. Projectification and the Need for Resilience

Our interest in resilience in a project-based work environment is driven by the intriguing dynamics of the projectification phenomenon, which, as highlighted by existing research, entails notably negative consequences for individuals affected by it [31]. Projectification can be defined, based on Midler [32], as an organizational transformation process [33], involving a shift from strong functional units, where projects play a subordinate role, to a structure where projects take centre stage and functional units act as labour pools [34] (p. 9). The phenomenon of projectification is reshaping organizational landscapes into project-centric structures. Currently, approximately 30% of all work is project-based [35]. The increasing reliance on projects appears to have led to a neglect of project workers’ well-being and problematic outcomes stemming from project overload [3].

Many studies have highlighted potentially unsustainable elements in project-based work, often emphasizing the impact on workers’ health and well-being [1]. This is due to many reasons. A project-based work environment is characterized by a heavy workload [36] and project managers often struggle in delivering outcomes that not only meet customer expectations but also stay within predetermined timelines and budgets [37]. In addition to coping with time pressure and strict deadlines [38,39], project professionals often find themselves managing situations where projects spiral out of control, requiring improvisational solutions [1]. It is common for project plans to be devised primarily for obtaining political approvals, leading to plans that are not well-thought-out, overly optimistic, or have unclear or inaccurate objectives, and that do not always incorporate the valuable inputs of the project managers or the executing teams [1]. Furthermore, project employees need to navigate potential conflicts between their professional identities [1] and deal with the uncertainty and insecurity that come with the contractual nature of their positions [40]. These situations may result in overwork, stress, and a possible risk of burnout [1,2].

Beyond individual well-being, scholars increasingly frame workforce resilience as a prerequisite for sustainable project governance (cf. ISO 21502:2020 Project, Programme and Portfolio Management—Guidance on Project Management, 2020) [41]. Climate-related disruptions, supply chain shocks, and stakeholder pressure for greener outcomes expose project professionals to continuous uncertainty. Embedding resilience mechanisms thus directly supports the sustainability of the human subsystem inside the broader socio-technical project system.

2.2. Systems-Theory Foundations of Resilience

Resilience can be fruitfully viewed through the lens of General Systems Theory [7] and subsequent work on complex adaptive systems [8,9]. A project-based organization constitutes a socio-technical system in which elements (project professionals, artefacts, governance routines) interact via feedback loops that cross porous boundaries and are continuously perturbed by the external environment (market shifts, regulatory changes, stakeholder demands). In this view, resilience denotes the capacity of the system to absorb disturbances, reorganize and retain core identity and functions [42,43]. Importantly, emergent resilience depends not on isolated parts but on the quality of connections among subsystems (teams ↔ individuals/governance/external stakeholders) and on the speed/quality of feedback. Projectification heightens system coupling and volatility, amplifying both risk and adaptive potential.

Building with this systemic framing, the following subsections review (i) how resilience is conceptualized across levels, and (ii) how agile mindset and agile practices can be interpreted as designed feedback loops and latent capabilities that bolster system-level resilience.

2.3. Resilience Process and Its Multi-Level Nature

Given these circumstances—and grounded in the systems lens outlined above—it becomes imperative to understand how resilience manifests and propagates within the projectified socio-technical system. We draw from Fisher et al.’s [5] definition of resilience, which characterizes resilience as a process where subjects are able to positively adapt to substantial difficulties, adversity, or hardship [5], applicable at both individual and team levels in organizations [44]. Under this framework, the following variables are defined [5]: (i) adversity: factors that represent challenges or hardships, including both sudden events and ongoing difficulties, that can cause disruption; (ii) resilience resources: traits or environmental elements that offer protection or support during times of adversity, regardless of whether adversity occurs; (iii) resilience mechanisms: factors that involve the ways individuals react, respond, and strategize when facing adversity; (iv) resilience outcomes: indicators of successful resilience, reflecting healthy or effective functioning in the face of adversity.

It is important to also consider the multi-level nature of the resilience phenomenon. Resilience has been studied on various levels, including organizational [45,46,47], team [48,49,50], individual [5,51], or project levels [29]. The latter is especially popular in project management discipline, which often leans towards a process-oriented view of resilience, primarily focusing on its utility in navigating risks, crises, and unexpected changes [27,28,29], with an emphasis typically placed on project performance or success [52], rather than the outcomes related to people.

In our study, we focus on the resilience of project teams and their members—i.e., individual- and team-level resilience. With significant conceptual differences between the two [48,53,54], there is a clear need to study them as separate constructs [50]. Although we acknowledge various connections between the two levels, as suggested by several authors [44,51,55,56,57], our study merely touches on the interconnections and does not go into detail on their nature.

2.4. Agile as Resilience Antecedent of Project Teams and Their Individual Members

Several advantages of agile practices have been documented in the literature, not only concerning enhanced project success outcomes [58,59] but also with regard to positive effects on individuals. For instance, agile practices have been linked to enhanced job satisfaction [12], increased motivation [13], and lower employee turnover [60]. Studies, including those conducted outside the realm of software development—where agile practices are most commonly applied—have also identified benefits such as improved team collaboration, enhanced customer engagement, greater productivity and speed, as well as increased flexibility and adaptability to change [61].

The increasing acknowledgment of advantages offered by agile practices is driving organizations, of various sizes, across different sectors and beyond software contexts, towards the widespread adaptation of agile practices [16,61,62]. However, challenges often arise from a lack of an agile mindset [10,16], which is important because it shapes individuals’ and teams’ behaviours, attitudes, and beliefs towards change, uncertainty, collaboration, and continuous improvement [16]. Even when agile practices are not uniformly implemented across an organization, it remains essential to promote the understanding and application of agile principles and mindsets throughout the organization [17]. Rooted in the Agile Manifesto’s values and principles, an agile mindset embodies trust, responsibility, ownership, a continuous drive for improvement, and a willingness to learn, adapt, and grow [16]. We suggest that the agile mindset is equally, if not more, critical to fostering resilience compared to agile practices.

In this article we treat the agile mindset as a micro-level cognitive resource located in the individual project professional, and agile practices as meso-level structural routines embedded in the project team. Consistent with a complex-systems view, these resources are not confined to their native level: an individual’s agile mindset can propagate upward and become a catalyst for team-level resilience, while team-level agile practices can feed back and nurture individual resilience. We therefore posit that both constructs serve as systemic antecedents of resilience by ding the following:

- Providing an immediate stock of adaptive resources;

- Generating or amplifying additional resilience resources elsewhere in the system;

- Operating as rapid response mechanisms during adversity;

- Enabling the emergence of new mechanisms through positive feedback and learning across levels.

This cross-level perspective positions agility as a designed feedback architecture that strengthens the entire socio-technical system’s capacity to absorb disturbance, reorganize, and continue functioning.

In the following sections, we define the agile mindset and agile practices in greater detail, supported by the relevant literature, and present compelling arguments suggesting their potential connections to resilience.

2.4.1. Agile Mindset as a Systemic Resilience Antecedent

Our study follows the agile mindset definition outlined by Eilers et al. [22], which, to the best of our knowledge, offers the most detailed and robust definition. Authors argue that the agile mindset, while not directly observable and measurable, is a latent construct that can be described through four observable and measurable dimensions [22].

- (1)

- Attitude towards learning spirit: Individuals with this attitude are driven by curiosity, embrace uncertainty, and view knowledge gaps as opportunities for growth [22], which could potentially be a resilience antecedent. For example, it has been suggested that the resilient processes in a team arise from the combined knowledge, skills, and abilities of team members [49]. Furthermore, experiences of overcoming adverse events may strengthen team resources and a team’s capacity to deal with future disruptions [63], implicating that individuals with an attitude towards a learning spirit could potentially support future resilience. Finally, the literature also connected learning culture, inquiry and dialogue, and knowledge-sharing structures to resilience [64].

- (2)

- Attitude towards empowered self-guidance: These individuals prefer the autonomy to organize their work, take responsibility for outcomes, and adapt to changes while continuously self-reflecting [22]. Prior research has identified self-efficacy and confidence as personal resources that help individuals feel more capable of addressing work challenges, which in turn boosts their persistence, motivation, and ability to overcome adversity [65,66]. The literature also links psychological empowerment to outcomes like task performance [67,68] and job satisfaction [69]. For instance, Tian et al. [70] connects psychological empowerment with resilience, particularly in the context of workplace burnout. Moreover, studies have examined how self-reflection contributes to resilience [71]. These factors could help mitigate or quickly address adversities that stem from projectification.

- (3)

- Attitude towards collaborative exchange: Individuals with this attitude actively engage in transparent, diverse, and constructive teamwork, valuing knowledge sharing and collective problem-solving [22]. Some authors suggest that team members must be motivated to collaborate, as a lack of cooperation hinders a team’s ability to effectively overcome adversity [72,73]. Furthermore, sharing responsibilities and tasks with colleagues might reduce individual burdens and alleviates stress in challenging situations [74]. These findings suggest that a positive attitude toward collaborative exchange can be a key antecedent to not only individual but also team resilience, as teamwork and social support also foster a stronger collective capacity to handle setbacks. For example, research links collaboration with greater team effectiveness in facing challenges [75]. It has also been suggested that team resilience depends on collaboration, mutual support, and inter-team alignment [56].

- (4)

- Attitude towards customer co-creation: These individuals prioritize customer needs, ensuring customer centricity to continuously enhance added value [22]. Among the connections between attitudes and resilience discussed, this one has the least robust backing in the current literature. Beyond preventing certain adversities by improving project success due to customer involvement [76,77], there is another potential link worth considering. Individuals who exhibit a strong inclination towards co-creation with the client may derive a deeper sense of purpose and mission from their work, when working in a customer-centric environment. As suggested by previous studies, a sense of meaning and purpose [78,79] and a professional mission [80] are key factors that support resilience; therefore, in this context, this attitude could serve as an antecedent to resilience.

2.4.2. Agile Practices as Systemic Resilience Antecedents

Our study conceptualizes agile project management by incorporating four distinct practices, following the approach of Malik et al. [15]. We chose this framework because we aimed for a broad and general conceptualization of agile practices rather than focusing on a single agile method (e.g., Scrum). While other frameworks do exist, many studies on agility and agile practices in project management remain largely conceptual [19,81]. More empirical approaches [59,82] measure the level of agility more directly; however, we needed a framework clearly separating agile practices from the agile mindset, which our study addresses separately. Malik et al.’s model is comprehensive, built on existing validated conceptualizations, and has been previously applied for measurement, making it the most suitable choice for our study.

- (1)

- Team autonomy: Members of agile teams are collectively responsible for managing their own work. An autonomous project team would have the freedom to select its tools and technologies, control over the project scope, autonomy in managing changes, and the ability to assign personnel as needed [83]. Autonomy enables teams to respond to changes and make decisions fast [15,84,85]. Furthermore, an empowered team that has trust is also motivated and feels a high degree of responsibility for achieving a goal [86], which could potentially help them push through some adverse situations. In the existing literature, we also find that jobs that are designed based on autonomy and empowerment have been linked to individual’s resilience [87].

- (2)

- Team diversity: Team diversity in agile practices includes differences in functional backgrounds, skills, expertise, and work experience among members [83]. The literature suggests that a resilient team process can emerge from the combined knowledge, skills, and abilities of its members [49]. Team diversity has been linked not only to improved performance [88] but also to innovation [89,90]. Some authors argue that interactions between members with diverse technical backgrounds foster creativity and generate new solutions for complex problems [91,92]. Thus, team diversity may be a valuable resource for resilience, benefiting both the team and its individual members.

- (3)

- Iterative–incremental development: Agile practices are based on iterative cycles and incremental development, enabling a flexible project scope through a number of time-boxed iterations or sprints [93]. This could serve as a resilience mechanism, because it enables teams to quickly turn around and act resiliently when faced with adversity. Furthermore, the practice supports outcomes that may enhance resilience, including the identification and integration of customer needs [94] and improvements in project quality [95]. For example, Hendriksen & Pedersen [86] found that among the most important benefits of using iterative development and sprint reviews were receiving early feedback from customers, handling changing priorities, and solution uncertainty. By leveraging customer feedback for continuous improvements, iterative delivery navigates and mitigates uncertainty throughout the project [96], which could be a resilience antecedent for both teams and individuals.

- (4)

- Agile communication. The agile approach prioritizes collaboration and communication between team members and stakeholders [59]. Agile communication promotes face-to-face interactions and activities like daily team meetings, review sessions, and retrospectives, while also fostering an informative workspace. This ensures that stakeholders have easy access to key information, such as project status, at any time [97]. Teams can effectively adapt to the dynamic and evolving project environment through agile communication [81]. Working closely with the customer ensures value delivery, even in the face of project unpredictability [98]. Agile communication enhances collaboration in the team, improves the understanding of goals, tasks, and requirements, and gives team members a clear sense of progress [99]. On the other hand, failure in effective cooperation and communication among team members compromises resilience [56]. All this considered, agile communication could be a key resilience antecedent for teams and their individual members.

The next section details the qualitative methodology employed to examine these proposed systemic relationships.

3. Research Methodology

Our conceptual framework is underpinned by two foundational theoretical perspectives, employing a multi-level approach as outlined by Kozlowski and Klein [100], and incorporating insights from the Conservation of Resources (COR) theory [101,102]. Both lenses are situated within a complex–adaptive-systems epistemology, allowing us to treat the organization ↔ team ↔ individual triad as nested subsystems with dynamic feedback. While each perspective offers valuable insights on its own, this integrated approach allows us to formulate nuanced propositions about the specific ways in which resilience manifests and interacts across individual and team levels with an agile mindset and practices as potential resources. We employ a qualitative research approach, selected for its suitability in exploring the complex relationships between chosen constructs. This requires access to personal viewpoints, thereby guiding our methodological decisions, including the development of research instruments, the selection of the data collection method and sampling techniques, and finally the execution of thematic analysis. In each step we incorporated recommendations from various authors on conducting qualitative research and method application [103,104,105,106]. Diving into individuals’ personal experiences, we employ a semi-structured interview technique with a predetermined list of questions, a method that is considered valid for such purposes [107].

Interview Guide Development. The guide was crafted considering the recommendation of Lune & Berg [103], comprising open-ended questions engineered to elicit rich, reflective narratives. The guide underwent pilot testing with 3 selected participants to refine the questions for clarity and fluidity. Essential questions, which exclusively concern the central focus of the study [103], addressed each aspect of the agile mindset attitude and each agile practice as a resilience antecedent in various adverse situations. Illustrating this through an example of attitude towards collaborative exchange, examples of essential questions included the following: “If you recall an adversity you faced at work—how did your attitude towards collaborative exchange help you in overcoming it?”, “If you recall an adversity your team faced at work—how did attitude towards collaborative exchange of you and/or other team members help you in overcoming it?”.

We used alternative essential questions, which were used in cases where interviewees did not recognize themselves as having specific attitudes of an agile mindset. Questions were slightly rephrased, but still served the same purpose. We defined additional questions to ensure that what interviewees described was in fact a resilient process, with resilient mechanisms and resilient outcomes, as defined by Fisher et al. [5]. These questions included “How exactly did you overcome the adversity due to this [collaborative exchange] attitude?”, and “What were the positive outcomes?”.

Sampling Technique. We employ a combination of two sampling strategies to adequately addresses our objectives [104]. First, we employed criterion sampling, which includes involving participants based on specific predetermined criteria [108]—in our case, individuals with experience in project-based environments, with at least three years of experience in roles such as project managers, project team members, and product owners. Second, we employed maximum variation (heterogeneity) sampling, which includes constructing the sample by firstly identifying key dimensions of variations and secondly including participants that vary in these dimensions as much as possible [104]—in our case, a large spectrum of backgrounds, including experiences in different project types, industries, and organizations, and different levels of formal education in project management. Maximum variation sampling can be used to develop a comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon [104], as this strategy enables two important aspects. It not only provides high-quality, detailed descriptions of each case and their uniqueness, but it also facilitates the recognition of patterns that are common across cases, deriving significance from their diversity [108]. Recruitment of participants was facilitated through professional networks. We employed a snowball sampling approach, beginning with personal and professional contacts who met predefined selection criteria and inviting them to suggest additional eligible individuals; of the 14 candidates invited through this process, 11 participated in the study. Our final sample included project managers (PMs), project team members (PTMs), and product owners (POs). This heterogeneity increases the variance of system states sampled, which is essential when studying emergent resilience. Table 1 summarizes the profiles of the 11 interview participants, detailing their primary roles, gender distribution, industries of employment, and main countries of employment.

Table 1.

Participant Demographics by Role, Gender, Industry, and Employment Location.

Data Collection. We conducted eleven semi-structured interviews that varied in length from 45 to 75 min, allowing for comprehensive discourse. The interviews were held in April and May 2024. They were carried out both in person and remotely, depending on participant availability. All sessions were audio-recorded and later transcribed verbatim. Participants were assured of anonymity and confidentiality, and—although no formal IRB approval was required under national regulations—written informed consent was obtained after they had received full information on the study’s aims, procedures, and data-handling practices.

Data Analysis. We applied an inductive thematic analysis [105], chosen for its capacity to let patterns emerge without forcing the data into a pre-existing coding frame, thereby yielding a richer, context-sensitive description of the entire corpus. Although thematic saturation was reached after nine interviews, all 11 transcripts were analyzed to ensure that no additional themes surfaced [109].

Guided by Braun and Clarke’s [106] six-phase procedure—and with an explicit focus on cross-level feedback loops that were consistent with our system’s framing—the analysis proceeded as follows:

- Familiarization: verbatim transcription and repeated reading of each interview to immerse the researchers in the data;

- Initial coding: systematic, line-by-line coding in NVivo; codes captured both manifest content and latent notions of resilience feedback;

- Theme search: aggregation of related codes into provisional themes, noting links between micro- (mindset) and meso-level (practice) phenomena;

- Theme review: iterative comparison of themes against the raw data and against one another; discordant cases were discussed until a consensus was reached;

- Theme definition: refinement and clear naming of 17 final themes—clustered under five higher-order “systemic resilience themes” (empowerment, responsiveness, holistic team dynamics, stakeholder ecosystem engagement, learning and continuous improvement);

- Reporting: selection of the most illustrative quotations and construction of a system map that depicts how themes couple across levels.

This procedure ensured analytic rigour while foregrounding the systemic nature of agile-enabled resilience.

4. Results

Participants were asked to think of situations where the four dimensions of an agile mindset and agile practices enabled resilience either for them individually, their teams, or both levels at the same time. We have identified various resilience resources and mechanisms that are enabled through an agile mindset and practices and contribute to resilient mechanisms and outcomes. Table 2 outlines the systemic resilience themes and sub-themes that emerged from the data.

Table 2.

Systemic resilience themes and sub-themes.

4.1. Empowerment

Project teams that are empowered and autonomous can ideally make independent decisions regarding deadlines and scope, which can be very beneficial from the point of view of resilience, as it gives teams the control over the situation.

PO2: “We have the autonomy to determine the scope and exact deadlines, and in these cases we are more likely to stick to those deadlines and avoid major delays. […] It helps us to be able to adjust the timeline, not to over-promise and not to create too many expectations from the stakeholders.”

One important factor that interviewees often pointed out is control over complexity. Specifically, incremental-iterative development is one common practice that provides individuals and teams with control over complex and often overwhelming project situations.

PTM1: “When we faced a big challenge, my boss always said: ‘How do we eat an elephant? Bite after bite!’.”

PM4: “This [iterative-incremental development agile practice] is especially important when the problem is too big to solve just like that. You start with a smaller, manageable part and then build part by part towards a solution that may have seemed impossible at the beginning.”

PTM3: “This way you’re not in a panic, ‘Oh, what chaos, what now, the end of the world!?’”

Empowerment was also connected to motivation, which could support resilience when faced with various challenges.

PTM3: “Of course, if the team has autonomy, then it will be more driven and more motivated when executing the project tasks.”

PTM4: “I’m more passionate about these activities [where the team has more autonomy] and I have more energy when I have that sense of autonomy.”

Connected to responsibility and autonomy, self-confidence is also commonly mentioned. This is also particularly important when project professionals are hired externally or work in extremely volatile sectors and they highly depend on delivering the right results.

PM4: “You are expected to solve problems independently. You have to trust yourself and make decisions, even when you have some doubts.”

PM2: “At the end of the day, you have the responsibility to complete the tasks and you have to somehow organize yourself to actually get it all done.”

Finally, many situations in a project-based environment require a great deal of tenacity and strength from individuals and teams, combined with patience and persistence. Sometimes there is no way to prevent adversity—the only way out is through.

PTM2: “With close cooperation and a strong will-power, we were able to realize the requests for changes that came at the last minute.”

PM4: “In situations where regular work and projects are overlapping, you sometimes just have to find a way to make it work push through heavy workloads. […] For a while we all had an increased workload, we were all more stressed. […] There’s no good way to get around it, you just have to go through this difficult period.”

4.2. Responsiveness

Individuals and teams that have autonomy and are responsible for their work are able to respond fast, which is important when dealing with some challenges. In some cases, adversities are also prevented, for example, due to avoiding delays and conflicts.

PM4: “You don’t have to go to the manager for every decision, which in many cases speeds up progress on the project.”

PM3: “[When faced with adversity], it meant a lot that I knew how to turn around quickly.”

According to interviewees, openness is very important in order to respond resiliently in situations with lots of ambiguity and uncertainty, which is quite common in project-based environments. An open mind can also strengthen future resilience.

PTM1: “In this way [by being open], we were able to show resilience [in that particular situation], although at that moment we did not even know what exactly this would mean for us.”

PO2: “They were faced with a different reality and they kind of took a step back and said, ‘OK, what can we learn from this? How can we work differently to somehow achieve a better outcome for our team?”

With agile practices, project teams can respond fast and by doing so, prevent various major adversities. All four agile practices are mentioned within this aspect, as they support the ability to respond fast.

PM4: “For example, we had a problem that required different types of skills […]. And then we had to come together very quickly, which was really no problem, because all these diverse skills were already in our place—in one team.”

Thanks to iterative–incremental development, for example, a team is able to quickly make changes in scope, and prevent major mistakes and the delivery of something that is not expected. Agile communication also supports this.

PTM2: “Daily meetings with all relevant stakeholders are really good because it is often easier to find a quick solution or at least the right contact person who can resolve the situation.”

PM3: “It was very important [in adverse situation] that I we were able to turn around quickly. ‘OK, this is not what we expected, but this is our reality now’, let’s continue from here…”

Transparent documentation also plays an important role in this. According to respondents, transparency often facilitated resilient mechanisms in response to various adversities, enabling teams and individuals to quickly and easily access essential information that was necessary to address the situation.

PM3: “Anyone can always check that everything is going according to plan and if not, you can react very quickly.”

PTM2: “When things are properly documented, everyone can access everything, which speeds up the resolution of many challenges.”

4.3. Holistic Team Dynamics

Individual team members in agile teams complement each other in their diversity. We found that this is very important for resilience, according to some interviewees, it is even the most fundamental dimension of agile practices.

PM1: “It [the situation] was difficult, but just knowing that we have all these diverse skills and knowledge of my colleagues in the team helped me not to fall into a state of panic.”

PTM1: “This diversity meant that not everyone contributed in the same way, which was our strength [in the moment of need]. Basically, our combined diverse skills worked like a well-oiled machine.”

Furthermore, collaborative and supportive inter-team relationships are very important for the resilience of project teams and their members in connection with various agile practices.

PM2: “The team helped me resolve the problem because they supported me in this communication [with stakeholders] with their technical knowledge. I wouldn’t have been able to do it myself, because it was about technical things that I don’t even understand myself, and then I can’t communicate them myself either.”

Another important agile practice in this aspect is also agile communication, which enables close collaboration in fast problem-solving, setting correct priorities, and building solid relationships. This can prevent various ambiguities or the possible overworking of individual team members.

PTM4: “We have a kind of an overview of the day for each person, and even if there are new tasks or sudden changes in the project, we can decide who will take them based on the current workload.”

PO2: “Since it is very difficult to prioritize tasks in a sea of obligations and distractions, continuous communication can make the entire team more resilient in overcoming these challenges.”

Finally, trust and empathy among team members are also highlighted as important factors for enabling resilience. Interviewees described some individual hardships, such as work overload or personal private life problems, which affected individual team members. Empathy and trust were of key importance here, with team members or managers showing that they have each other’s backs.

PTM3: “When you are experiencing some personal issues, it is good to know that you have a team that stands by you. It is important that you are transparent with them so that they may be able to help you at that moment. Maybe next time the situation will be reversed and you will be able to help them.”

PM4: “I explained to him [the manager] that I was really overwhelmed. […] ‘I know I’m not stupid. But I just can’t do it anymore.’ His response was something along the lines of ‘I understand you and thank you for coming to me’. Then together we prepared a plan to resolve my situation.”

Related to this, transparency and trust are also often pointed out. For example, the interviewees believe that it is very important for team members to transparently discuss potential adversities.

PO2: “In our company and in our teams, we always discuss that it is necessary to ask for help and that it is necessary to express when you do not feel good about a certain task.”

Another important aspect of the resilience of project teams and their members is the protectiveness of individual team members (e.g., project managers or product owners) towards the team when dealing with various stakeholders. In this way, individuals prevent certain adversities and spare the resources of their project teams and their members.

PM3: “I am the face of the project to the outside world, which means that screaming managers, short deadlines and other problems do not reach the team. I am their shield.”

PO3: “I protect my team in many meetings. I have to be their ‘safety net’.

4.4. Engaging the Stakeholder-and-Customer Ecosystem

Throughout interviews, collaboration is one phrase that was very often repeated, associated with both internal team members and external stakeholders. Interviewees emphasized the significance of working together with customers, different functional units within the organization, other project or product teams, leadership, external contractors, etc. Collaborative relationships with customers and other stakeholders can play a vital role in effectively addressing and preventing adversities.

PTM3: “You have to have a good relationship with them [one specific functional unit within the organization], because you are in contact with them very often and they often have answers that can help you in one way or another.”

PM2: “You know, at the end of the day, the end users are the ones using what we deliver, and we can’t know if everything suits their use or not. [without collaborating with them]”

PM4: “We have different teams and different projects, different managers and, of course, many different opinions about how and what we should do. […] In the end, the decision must be made by management. […] You have to be collaborative in this and clearly communicate your opinions.”

Transparency, enabled by agile communication, is often linked to this aspect. The active engagement of stakeholders, including customers and others, is vital to both the prevention of and effectively addressing adversities.

PO2: “Because we get better feedback, we are more confident with what we create. Already in the process of creating a feature, we know that what we are doing is good […]. In such situations, you definitely have more confidence in your work.”

PM4: “We overcame the problem with the team by establishing daily calls, which were also attended by representatives of the external contractor and other stakeholders. That’s how we really started to talk on a daily basis and that’s how we as a team could kind of push the project forward—more communication, more activities, more progress.”

Another important sub-theme that emerged is customer centricity. A focus on customers can foster a professional mission and sense of purpose that helps individuals through adverse situations.

PTM1: “I have the feeling that I can really contribute something useful for them [customers] […] It gives the work a purpose, and with that in mind, it is easier to get through big piles of work and short deadlines from time to time.”

Additionally, having a good understanding of customer needs can help prevent various adversities. Customer centricity is important for resilience, not only at individual and team levels but also at higher levels, such as in organizational or strategic resilience.

PTM2: [about new customer-centric project manager] “When she came along, she somehow managed to improve transparency and management of expectations and led the team based on that. Then everything was a little clearer and the team members experienced less frustration because they were finally delivering something that was well received.”

PM2: “We have to keep our customers in mind all the time […] We have a limited pool of potential customers, so we have to compete for them.”

4.5. Learning and Continuous Improvements

Interviewees frequently highlighted various situations where they continuously learned and improved, either as a team or as an individual, through the adoption of agile practices and/or an agile mindset. This has proven valuable not only in addressing immediate challenges but also in fostering future resilience.

PO1: “Together with my colleagues who were extremely supportive and had a different level of technical knowledge, we found a way to fill my knowledge gap. We were able to present the topics in a way that was understandable to me, so that I could process the information.”

PM2: “It [iterative-incremental development practice] helps me figure out what works and what doesn’t. Through this learning, I can then take the project forward.”

PTM3: “Each time you have a new experience and next time [in the next iteration] you will know better what to do and how to do it.”

Such adaptability is particularly relevant in highly uncertain contexts, such as projects involving significant novelty and unfamiliar components, or during transitions between projects, especially when moving into new and unfamiliar domains.

PM1: “Once I gained new knowledge and really understood the situation, I finally saw where the bottlenecks were occurring and it was easier for me to solve problems and move things forward.”

Teams and individuals that engage in continuous improvement also strengthen their resilience for future adversities.

PO1: “This [adversity] also helped us to identify a more resilient process. […] So that was a good learning for us.”

PTM2: “If someone is very passionate about learning, they might also be passionate about sharing their knowledge with others, or at least properly documenting it, so that others may not need to search for information in the chaos and face the same challenges.”

5. Discussion

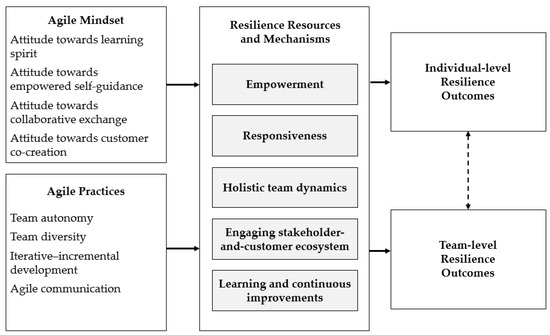

Figure 1 presents a simplified graphical model of our findings, illustrating (1) the existence of relationships between the constructs and (2) the main themes that link an agile mindset and agile practices with resilience.

Figure 1.

Overview of key themes connecting an agile mindset and practices with resilience. Note: The dotted line represents the relationship between individual- and team-level resilience, which was frequently mentioned and implied by participants but was not the primary focus of this research and therefore was not examined in detail.

5.1. RQ1 and RQ2: Confirming the Connection

To begin, we address RQ1 and RQ2 by examining how both the agile mindset and agile practices contribute to resilience at individual and team levels within projectified environments.

RQ1: How does an agile mindset foster resilience at both the individual and team levels in projectified environments?

RQ2: How do agile practices contribute to resilience for individuals and teams in projectified environments?

In response to RQ1, our findings, supported by the existing literature, demonstrate that an agile mindset acts as an important multi-level resilience antecedent for project teams and their individual members. An agile mindset enables the activation of various resilience mechanisms and leads to diverse positive outcomes across both levels. Furthermore, our results suggest that an agile mindset is not merely beneficial, it is essential, as the absence of this mindset could severely worsen the adversities of a projectified work environment.

The main themes that emerged, answering the question of how exactly an agile mindset fosters multi-level resilience, include a variety of resilience resources and mechanisms, including self-confidence, tenacity and strength, responsibility and autonomy, fast responsiveness, openness, collaborative and supportive relationships within the team, trust and empathy, collaborative relationships with stakeholders, customer centricity, learning, and continuous improvements.

In response to RQ2, our findings, supported by the existing literature, indicate that agile practices also act as an important multi-level resilience antecedent for project teams and their individual members. Agile practices can be directly utilized as resilience mechanisms and serve as a potential resilience resource on both levels.

Answering the question of how exactly agile practices foster multi-level resilience includes a variety of resilience resources and mechanisms, with main emerging themes being empowerment, control over complexity, fast responsiveness, transparent documentation, team diversity and complementarity, protectiveness, collaborative and supportive relationships within the team, collaborative and supportive relationships within stakeholders, customer involvement, learning, and continuous improvements.

An important finding is the close connection between the agile mindset and agile practices, as interviewees often described how elements of the agile mindset were enabled through specific agile practices. However, the agile mindset proved to be adaptable to a broader range of environments, underscoring the value of hybrid approaches, which combine the flexibility of agile practices with the stability of traditional methods [110]. Our results indicate that the agile mindset is equally important in contexts where agile practices are not strictly followed.

Another important finding was the frequent connection between team and individual resilience. For instance, an individual’s mindset could drive the entire team to become more resilient, or a team’s practice could foster resilience in an individual. This supports previous research, which suggests that resilience at the individual level can be a resource for team-level resilience, and vice versa [44]. While we did not explore the details of this interaction, we acknowledge its existence. It is also common in our findings that the agile mindset and agile practices function as multi-level antecedents of resilience, enabling both individuals and teams at the same time.

5.2. RQ3: Exploring the Main Factors of the Connection

Addressing RQ3, five main factors have emerged that we describe in the following chapters.

- RQ3: What are the key factors that enable the agile mindset and agile practices to serve as resilience antecedents in project settings?

5.2.1. Empowerment as a Resilience Resource and Mechanism for Individuals and Teams

Formal empowerment of teams allowed them to maintain control and avoid overpromising to stakeholders, enabling the effective navigation of complex situations. Interviewees reported that this autonomy facilitated quick responses to changes and timely decision-making, a finding that aligns with the existing literature [15,84,85]. As a result, team autonomy emerged as an agile practice that not only enhanced resilience when facing adversity but also contributed to the prevention of challenges, ultimately preserving valuable resources.

Our study confirms existing findings that suggest that empowerment and autonomy foster motivation which helps teams and individuals push through adversities. For example, an empowered team that has trust is also motivated and feels a high degree of responsibility for achieving a goal [69,86], which could potentially help them push through some adverse situations. In the existing literature, we also find that jobs that are designed based on autonomy and empowerment have been linked to an individual’s resilience [87].

That said, empowerment extends beyond team autonomy; it also encompasses specific mindsets that enhance it. Our findings indicate that tenacity, strength, and self-confidence serve as important connections between an agile mindset and resilience. Interviewees recounted various challenging situations where they needed to be proactive, persevere, and take responsibility. In particular, the attitude towards empowered self-guidance and the attitude towards a learning spirit greatly supported resilience. We can find some reasoning for our observations in the psychological empowerment literature, which has established positive connections between psychological empowerment and various outcomes, such as task performance [67,68,111], job satisfaction [69], organizational commitment and citizenship [68], and others. Tian et al. [70], for example, also connect psychological empowerment to resilience in situations such as job burnout.

An essential aspect of such autonomy is the responsibility that accompanies it. A key insight, supported by both the literature and our study, is that agile team members often develop a strong sense of personal ownership [94]. While this can be beneficial on the one hand to push through some difficult times, our findings highlight its potential downsides. Several interviewees described situations where this sense of responsibility became an adversity, as individuals felt accountable for project outcomes that were beyond their control.

5.2.2. Responsiveness as a Resilience Resource and Mechanism for Individuals and Teams

In times of adversity, swift and adaptive emergency processes are required [52]. Our study results confirm this—it is important to be able to respond fast. There are a few factors that play into that.

First, our results confirm that responsiveness is closely connected to team autonomy, as it enables teams to respond to changes and make decisions fast [14,84,85]. Second, we found that team diversity also contributes to this, as teams and individuals have instant access a variety of knowledge and skillsets they might require for resolving challenges they might be facing. These findings compliment previous studies that investigated benefits of team diversity [88,89]. Third, transparent documentation enables teams and individuals to quickly access necessary information when required, providing information they might require to react in certain adverse situations. Finally, having a mindset that allows openness, flexibility, and thereby fast responsiveness in adverse situations was important. While agile practices can enhance responsiveness, our findings indicate that, without the appropriate mindset, these practices are unlikely to be fully leveraged.

We found that the above resources and mechanisms that enable fast responsiveness and therefore resilient outcomes are important both for teams and individuals.

5.2.3. Holistic Team Dynamics as Resilience Resources and Mechanisms for Individuals and Teams

Our findings suggest that diversity, along with the complementarity of that diversity, i.e., the way team members’ differences fit well together, is highly significant for resilience. Some interviewees even identified this as the most fundamental aspect of agile practices. This observation aligns with the existing literature, which associates team diversity with numerous benefits, such as enhanced performance [88] and increased creativity in addressing complex challenges [91,92].

According to our findings, teams managed to overcome various adversities due to a high level of collaboration among team members. This comes as no surprise as existing research highlights numerous advantages of internal team collaboration, such as enhanced project efficiency and outcomes [112,113]. Furthermore, various sources linked collaboration to team resilience. For example, studies found that cooperation can enhance the effectiveness of managing challenges and setbacks [75] and that team resilience is constituted by cooperation, supportiveness, and striving for inter-team alignment [56]. On the other hand, failure in effective cooperation and communication among team members compromises resilience [56]. According to our interviewees, an attitude toward collaborative exchange and the use of collaborative agile practices, such as agile communication, were particularly important. With this we address an important gap, as most resilience studies focus on teams with no time constraints for collaboration. While resilience is often tied to long-term collaboration [114], and prior research suggests that it depends on relationship quality [115,116], project timelines often limit this. Our results indicate that a strong attitude toward building collaborative relationships is particularly relevant in project settings, where quickly establishing these connections is essential to preventing challenges and maintaining performance.

We found that an attitude of collaborative exchange fosters supportive, trusting relationships within teams, enabling members to feel more secure when facing adversity. Interviewees noted that this attitude helps individuals overcome challenges through empathic team support. This aligns with research suggesting that collaboration improves individual resilience by sharing responsibilities, which relieves burdens in adverse situations [74]. Trust, emphasized by interviewees alongside collaboration, encourages team members to help each other during difficult times [117], significantly strengthening individual resilience. Additionally, we found that protective actions by team members, especially project managers and product owners, such as shielding the team from external pressures, further supports resilience by preserving team resources and preventing potential challenges.

5.2.4. Engaging the Stakeholder-and-Customer Ecosystem as a Resilience Resource and Mechanism for Individuals and Teams

We found that collaborative relationships with customers and other project stakeholders can play a vital role for individual and team resilience.

One important aspect of this is customer centricity. A common theme described by interviews was a sense of purpose and professional mission. Interviewees with a high attitude towards customer co-creation said that this helped them to push through adverse times, because their personal values aligned with the purpose of their work, delivering benefits or helping the customer. This is in line with the existing literature which suggests that a sense of purpose and meaning [78,79], as well as the maintenance of a sense of professional mission [80], help individuals to be resilient when faced with adversity.

We found that customer-centric individuals and teams fostered collaborative relationships with customers, preventing several adversities through ways of working which regularly involve customers and intensively view situations through the customer’s point of view. This not only improves their performance, but also preserves the individual’s and team’s resilience resources by preventing adversities. This is aligned with the existing literature, which suggests that working closely with the customer ensures value delivery, even in the face of project unpredictability [98]. We found that in cases of acute and severe adversity, teams with this attitude and respective agile communication practices in place managed to overcome these situations resiliently. While benefits of customer involvement are reported in the existing literature [118], the connection between this attitude and resilience is, to the best of our knowledge, novel.

Furthermore, we discovered that collaborative and supportive relationships are important not only with customers but also with other stakeholders. In line with the project management literature, we define stakeholders as “individuals and organizations that are actively involved in the project, or whose interests may be positively or negatively affected by the execution or completion of the project” [119]. In our study, interviewees most frequently referred to other internal teams and leaders, functional departments, upper management, or external service providers as key stakeholders. Throughout interviews, we found that this aspect is often associated with transparency, which is facilitated by agile communication. According to our interviewees, actively engaging stakeholders is essential for both preventing and effectively addressing challenges.

5.2.5. Learning and Continuous Improvements as Resilience Mechanisms and Future Resilience Resource Development for Individuals and Teams

A recurring theme is the critical need for continuous learning to sustain resilience in fast-changing environments. We found that an attitude towards a learning spirit emerged as a key multi-level resilience resource within project-based work environments, which is in line with several authors that have indicated that resilience is associated with personal resources such as possessing job-relevant expertise [78] and the ability to manage work-related demands effectively [120]. Our findings confirm this and illustrate the importance of seeking information, actively learning, and collaborating when faced with situations where relevant skills or knowledge are lacking. This supports the idea in the existing literature that views resilience as a learnable capability that can be developed [64,121]. Our research validates this concept by demonstrating that individuals and teams who actively acquire information, skills, and knowledge can improve their resilient capabilities and outcomes.

Closely connected with this, we found that individuals who were willing to collaborate not only improved their own resilience but also contributed to the resilience of the entire team by upskilling their colleagues. This interconnectedness underscores the significance of cultivating a learning culture and knowledge-sharing practices. This aligns with the existing literature. For instance, Malik and Garg [64] discovered that a culture of learning, along with inquiry, dialogue, and structured knowledge sharing, is positively associated with individual resilience. Furthermore, the literature suggests that resilient teams consist of individuals with the appropriate skills and expertise to respond appropriately to negative and unexpected events, which the team can rely on to solve the challenges it faces [122]. Hartwig et al. [49] argues that resilient team processes emerge from team members’ combined knowledge, skills, and abilities. Fey & Kock [52] suggest that openness and willingness to acquire new skills are necessary preconditions for team resilience. We additionally found that this is especially important when working with projects with a high level of novelty.

Our findings also confirm that teams and individuals improve their future resilience by experiencing various adversities and learning from them. This is in line with the existing literature, for example, Flint-Taylor & Cooper [63] suggest that experiences of overcoming adverse events may strengthen team resources and a team’s capacity to deal with future disruptions.

5.3. Theoretical Implications

There are several theoretical implications of this study. First, we have created a novel connection between agility and resilience. Our study confirms a connection between agile practices, an agile mindset, and the resilience of teams and individuals, while also identifying the main factors driving this relationship, namely empowerment, responsiveness, holistic team dynamics, engaging the stakeholder-and-customer ecosystem, and learning and continuous improvements. To the best of our knowledge, the connection we made is novel, connecting these two previously separated bodies of knowledge. Additionally, by shedding light on the agile mindset’s impact on resilience, this study adds valuable insights into agile mindset research—an area where knowledge is still in its early stages.

Second, our findings confirm that resilience antecedents can operate at multiple levels, contributing to the understanding of multi-level aspects in resilience. We found that an individual’s mindset could drive the entire team to be more resilient and that a team’s practice could foster resilience in an individual. This supports previous research, which suggests that resilience resources at the individual level can also be a resource for team-level resilience, and vice versa [44].

Finally, there have been several authors pointing out the fact that the project management research is narrow, often focusing on increasing performance and technical aspects and project success [123] and neglecting the people aspect, which is particularly worrying due to the negative effects of the projectification of the workplace [1]. By shifting the focus from a project-oriented view of resilience to the lived experiences of project professionals in projectified workplaces, our study provided a broader understanding of resilience challenges within the project management discipline.

5.4. Practical Implications

Understanding resilience is crucial in the contemporary projectified workplace, especially given the challenges associated with projectification [1] and the increasing demand for project professionals [4]. Our findings highlight the connection between an agile mindset, agile practices, and resilience, which has significant implications for organizations—not only for operational leaders but also for the board-room, where the “human sustainability of the project workforce” is now an ESG-salient concern.

For boards and C-suite governance bodies, the study offers an additional message: by institutionalizing transparent, sprint-like feedback loops (e.g., brief quarterly retrospectives on workload, learning velocity and stakeholder co-creation) and by modelling an agile mindset at the top, directors gain earlier signals of environmental turbulence and can pivot strategic resources faster while preserving employee capacity. The five resilience factors we identified—empowerment, responsiveness, holistic team dynamics, stakeholder-ecosystem engagement and continuous learning—thus translate into concrete governance levers that help balance exploitation and exploration, integrate sustainability metrics, and reduce decision latency in volatile contexts.

It is important for organizations to recognize that both agile practices and an agile mindset foster workforce resilience. However, we found that the mindset is widely applicable, demonstrating adaptability to a broader range of environments; it remains critical even where agile practices are only partially adopted.

Our study therefore suggests tailored actions for each stakeholder group:

- Boards/sustainability committees should treat the five resilience factors as leading “vital signs” and request a concise dashboard to monitor them alongside financial KPIs.

- Executives play a key role in fostering organizational agility by making strategic decisions that establish operating models that are conducive to agile practices; they should also champion an agile mindset through visible behaviour.

- Agile transformation leaders must devote equal energy to cultivating mindset change and to redesigning structures and processes.

- Project professionals can embed select agile practices into traditional settings and actively cultivate their own agile mindset through ownership, collaboration, and deeper customer involvement.

- HR departments should design and deliver programmes that develop an agile mindset and track its impact on engagement, retention and well-being—key indicators of talent sustainability.

By acting on these recommendations, organisations can bolster systemic resilience, safeguard the long-term sustainability of their project talent, and respond more deftly to climate-induced or market-driven shocks.

5.5. Limitations

5.5.1. Methodological Limitations

While we anchored our constructs in the existing literature, we recognize that a more systematic literature review could enhance conceptual clarity and theoretical robustness. Additionally, our evidence derives from in-depth accounts of 11 European project professionals; qualitative insights therefore cannot be generalized to all sectors, regions, or cultures. Snowball recruitment may privilege well-connected practitioners and limit transferability. Although maximum-variation sampling mitigated this risk, the dataset still reflects self-reported perceptions that can be coloured by recall or social-desirability bias. Additionally, resource constraints prevented the inclusion of a larger sample. Finally, we acknowledge that the study design did not include data triangulation across sources, which limits the robustness of interpretations.

5.5.2. Theoretical and Scope Limitations

The study focuses on an agile mindset and agile practices as resilience antecedents at the individual and team levels; organizational-level dynamics and contextual moderators (e.g., culture, governance structures) were not modelled. We worked within the COR and multi-level frameworks; alternative lenses—such as socio-materiality or network theory—could reveal additional mechanisms. We also assumed that participants already possessed an agile mindset, without examining how that mindset is developed.

5.6. Future Research Agenda

The exploratory nature of this research is reflected in its reliance on a single data type; future studies should incorporate mixed- or multi-method designs to strengthen credibility and validity. Future studies would benefit from mixed-methods designs that triangulate our qualitative insights with quantitative approaches. Surveys and multivariate analyses could test the strength of the links between an agile mindset, agile practices, and multi-level resilience, while examining potential moderators such as national culture, industry context, or governance model. Additionally, future study would benefit from a structured literature review process to develop more fine-grained constructs and improve alignment between theory and operationalisation.

In the spirit of systems scholarship, researchers could also deploy system dynamics- or agent-based simulations to experiment in silico with the feedback loops identified here. Such models would reveal how adjustments in agile practices propagate across individual- and team-level resilience and, importantly, how those loops buffer human-talent stocks under varying climate-volatility scenarios—thereby quantifying trade-offs between schedule performance and long-term talent sustainability.

Beyond the agile mindset and practices, future work might explore related constructs—e.g., strategic agility—and investigate how leadership style, organizational culture, and HR policies moderate the agility-to-resilience pathway. An open question is how an individual agile mindset evolves into a shared team or organizational mindset, and what interventions accelerate that diffusion.

Finally, longitudinal or pre-/post-intervention studies could test which concrete initiatives—whether they are board-level governance changes, HR programmes, or agile-coaching efforts—most effectively strengthen resilience and promote the human sustainability of project workforces in increasingly project-centric organizations.

6. Conclusions

This paper set out to examine how an agile mindset and agile practices operate as systemic antecedents of resilience for individuals and teams in projectified work settings. Responding to the human challenges that arise when organizations rely heavily on projects, we adopted a multi-level systems perspective and an inductive qualitative design.

Our findings (i) confirm a robust link between agility and resilience, (ii) isolate five cross-level factors—empowerment, responsiveness, holistic team dynamics, stakeholder-customer engagement, and continuous learning—that transmit this link, and (iii) show that mindset and practices form an integrated feedback architecture: the mindset provides the cognitive energy, while practices supply the structural routines through which that energy propagates.

These insights extend theory by bridging previously separate studies on agility and resilience and by illustrating how antecedents flow across hierarchical levels within a socio-technical system. Practically, they suggest clear levers for executives, transformation leaders, project professionals, and HR specialists who seek to build sustainable, people-centred project organizations.

This study’s limitations include that it utilized a small European sample, qualitative scope, and a focus on team/individual levels. We invite future work that uses surveys, system dynamics- or agent-based models to test and simulate the feedback loops uncovered here. As projectification accelerates globally, understanding and cultivating systemic resilience will remain a pressing agenda for both researchers and practitioners.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.Š. and I.V.; methodology, N.Š.; validation, N.Š. and I.V.; formal analysis, N.Š.; investigation, N.Š.; resources, N.Š. and I.V.; writing—original draft preparation, N.Š.; writing—review and editing, I.V.; supervision, I.V.; project administration, N.Š. and I.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to limited resources.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Cicmil, S.; Lindgren, M.; Packendorff, J. The project (management) discourse and its consequences: On vulnerability and unsustainability in project-based work. New Technol. Work Employ. 2016, 31, 58–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, M.; Mariani, A. Managing the work-family interface: Experience of construction project managers. Int. J. Manag. Proj. Bus. 2016, 9, 243–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karrbom Gustavsson, T. Organizing to avoid project overload: The use and risks of narrowing strategies in multi-project practice. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2016, 34, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Project Management Institute. Project Management Job Growth and Talent Gap Report. 2017–2027; Project Management Institute: Newtown Square, PA, USA, 2017; Available online: https://www.pmi.org/-/media/pmi/documents/public/pdf/learning/job-growth-report.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2024).

- Fisher, D.M.; Ragsdale, J.M.; Fisher, E.C.S. The Importance of Definitional and Temporal Issues in the Study of Resilience. Appl. Psychol. 2019, 68, 583–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Checkland, P. Systems Thinking, Systems Practice; John Wiley: Chichester, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- von Bertalanffy, L. General System Theory: Foundations, Development, Applications; Braziller: New York, NY, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Holland, J.H. Genetic algorithms. Sci. Am. 1992, 267, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meadows, D.H. Thinking in Systems: A Primer; Chelsea Green Publishing: White River Junction, VT, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Denning, S. How to make the whole organization “Agile”. Strategy Leadersh. 2016, 44, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boehm, B.; Turner, R. Management challenges to implementing agile processes in traditional development organizations. IEEE Softw. 2005, 22, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripp, J.; Rienemschneider, C.; Thatcher, J. Job Satisfaction in Agile Development Teams: Agile Development as Work Redesign. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2016, 17, 267–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommer, A.F. Agile Transformation at LEGO Group. Res. Technol. Manag. 2019, 62, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augner, T.; Schermuly, C.C. Agile Project Management and Emotional Exhaustion: A Moderated Mediation Process. Proj. Manag. J. 2023, 54, 491–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, M.; Sarwar, S.; Orr, S. Agile practices and performance: Examining the role of psychological empowerment. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2021, 39, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mordi, A.; Schoop, M. Making it Tangible—Creating a Definition of Agile Mindset. In Proceedings of the Twenty-Eigth European Conference on Information Systems (ECIS2020), Marrakech, Morocco, 15–17 June 2020; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Dikert, K.; Paasivaara, M.; Lassenius, C. Challenges and success factors for large-scale agile transformations: A systematic literature review. J. Syst. Softw. 2016, 119, 87–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, C.; Hess, T. Becoming Agile in the Digital Transformation: The Process of a Large-Scale Agile. In Proceedings of the 39th International Conference on Information Systems, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–16 December 2018; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, H.; Dacre, N.; Baxter, D.; Ceylan, S. What is Agile Project Management? Developing a New Definition Following a Systematic Literature Review. Proj. Manag. J. 2024, 55, 668–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, S.A.; Bustami, R. Redefining resilience: Insights into project management’s capabilities of organisations through the pandemic and beyond. Manag. Matters 2024, 21, 78–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Xu, S.; Yu, J.; Lin, F. The Impact of Project Managers’ Psychological Resilience on Adaptive Performance: A Multilevel Model. Proj. Manag. J. 2025, 56, 198–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eilers, K.; Peters, C.; Leimeister, J.M. Why the agile mindset matters. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2022, 179, 121650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]