Abstract

Business Economics lacks coherent theoretical foundations despite its prominence in business education. This paper critiques conventional equilibrium-based curricula that begin with ceteris paribus assumptions, proposing instead a systems-based evolutionary framework integrating macro–meso–micro perspectives. Through conceptual analysis, we demonstrate how traditional approaches fail to capture dynamic business realities. Our evolutionary framework incorporates seven pillars: variation–selection–retention dynamics, multi-level integration, dynamic capabilities, institutional networks, complexity theory, organizational form evolution, and behavioral insights. The paper provides curriculum guidelines (12-week structure) that maintain economic literacy while teaching students to reason through feedback loops, uncertainty, and systemic change. This repositioning represents the need for a paradigm shift from static optimization toward understanding businesses as adaptive systems, better preparing students for navigating continuous change in complex environments.

1. Introduction

The field of Business Economics occupies an ambiguous position within contemporary business education. Faculty members find themselves teaching courses with this title, yet the discipline lacks the clear theoretical foundations and methodological consensus found in traditional economics or established business disciplines such as finance or marketing. This conceptual paper emerged from ongoing discussions among business educators who increasingly question what precisely we are teaching when we deliver Business Economics courses, particularly in MBA programs where students may receive no other “formal” training in economics fundamentals. Based on informal research on course syllabi and curricula, Business Economics programs in business schools across different countries uniformly follow a similar blend of basic microeconomic and macroeconomic concepts, supplemented by elements of business strategy.

This conceptual ambiguity partly stems from treating business phenomena through mechanistic, reductionist lenses rather than recognizing that markets are better understood as interconnected systems. A systems perspective involves thinking in terms of wholes, relationships, processes, and patterns rather than static, mechanistic assumptions. This systems orientation is essential for understanding how economic phenomena emerge from complex interactions between firms, institutions, and market structures, setting the stage for viewing Business Economics as the study of evolving systems rather than isolated transactional mechanisms [1,2,3]. Traditional approaches typically begin with ceteris paribus assumptions that, while useful for initial understanding, inadequately prepare students for the uncertainty and systemic complexity they will face in practice. (The teaching of economics and economic metatheory, though related, constitute separate fields of inquiry. The frequent oversight of metatheoretical considerations, however, tends to produce a relatively superficial and inadequate treatment of both the core subject and Business Economics as a modern scientific field [4,5]).

It should be clarified that this paper is a conceptual critique and literature-based review of Business Economics pedagogy, rather than an empirical analysis of curricula; the motivation for this work stems from the author’s multi-year exposure to teaching this course in various business schools and a gradually matured understanding that a change in approach is needed. This study seeks primarily to develop a more thorough and systematic foundation for this viewpoint. First, there is growing recognition that traditional economic models, with their emphasis on equilibrium and rational actors, inadequately capture the dynamic and often turbulent reality of contemporary business environments [6,7]. Second, business schools face pressure to provide students with analytical frameworks that bridge theoretical understanding and practical application, yet Business Economics often falls between these objectives [8,9]. Third, the emerging theoretical framework of evolutionary economics offers promising avenues for reconceptualizing how we understand firm behavior, market dynamics, and economic change in ways that may be more relevant to business practitioners [10,11].

This paper proceeds through several interconnected arguments. We begin by tracing the historical development of Business Economics as an academic field, examining how it emerged from the intersection of economic theory and business practice. We then analyze the current state of the discipline, identifying key tensions and limitations in existing approaches. Subsequently, we explore how evolutionary economics might provide a more coherent theoretical foundation for the field, particularly through its integration of macro–meso–micro perspectives. Finally, we propose specific guidelines for curriculum development that maintain essential economic literacy while incorporating evolutionary principles and complexity thinking.

2. Historical Development of Business Economics

2.1. Early Theoretical Origins and Industrial Theory Foundations

Business Economics emerged during the early 20th century as industrial managers and academic economists recognized the need for systematic economic analysis within business organizations. The field’s origins can be traced to several concurrent developments: the rise of large-scale industrial enterprises, the professionalization of management, and the application of economic theory to practical business problems. The foundational work of economists such as Alfred Marshall provided important theoretical groundwork, particularly through his analysis of firm behavior and market structures [12]. However, it was the practical needs of growing industrial enterprises that drove the initial development of Business Economics as a distinct area of study. Companies required frameworks for understanding pricing decisions, market competition, and resource allocation in ways that pure economic theory did not adequately address [13].

The emergence of Business Economics as a formal discipline occurred through progressive institutional evolution rather than a singular founding moment. Throughout the 1910s–1930s, leading American business schools gradually integrated economic analysis into their management curricula, recognizing that future business leaders needed systematic frameworks for economic decision-making. Harvard Business School exemplified this transformation when Dean Wallace B. Donham restructured the program in the 1920s, institutionalizing the case method while forging stronger connections between economic theory and business practice. The Wharton School and other pioneering institutions implemented similar reforms, each developing distinctive approaches to embed economic reasoning within management education. This convergent institutional movement across multiple schools created the intellectual infrastructure that would, after World War II, coalesce into Business Economics as a formally recognized academic discipline with its own methodologies, textbooks, and scholarly identity [14,15].

Subsequently, early practitioners like Joel Dean played crucial roles in establishing Business Economics as a legitimate field of inquiry. Dean’s work on “Managerial Economics” during the 1940s and 1950s demonstrated how economic principles could be systematically applied to business decision-making [16]. His approach emphasized the practical application of microeconomic theory to problems such as demand estimation, cost analysis, and pricing strategy, establishing patterns that continue to influence the field today. Meanwhile, in Europe, the Italian school of “economia aziendale” was taking shape, led by scholars such as Gino Zappa and Fabio Besta, who emphasized a holistic integration of accounting, management, and economics in the analysis of firms. This Italian tradition of business economics sought to unify the study of a firm’s financial and organizational aspects into a coherent framework [17,18], offering an early example of a systems-oriented approach that paralleled developments in Anglo-American Managerial Economics.

2.2. Post-War Theoretical Expansion and Academic Institutionalization

The post-World War II period witnessed significant expansion of Business Economics within academic institutions. Business schools, experiencing rapid growth during this era, sought to establish their intellectual credibility by incorporating rigorous analytical disciplines [19]. Economics, with its mathematical sophistication and theoretical coherence, provided an attractive foundation for business education seeking academic legitimacy.

During this period, Business Economics began to crystallize around several core areas: demand analysis and forecasting, production and cost theory, market structure analysis, and pricing decisions [20]. The field drew heavily from developments in microeconomic theory while attempting to make these concepts relevant for business practitioners. This dual orientation created ongoing tensions that persist in contemporary Business Economics education.

The influence of the Chicago School during the 1960s and 1970s further shaped the field’s development. Scholars such as Milton Friedman and Gary Becker emphasized the power of economic reasoning in explaining business behavior and market outcomes [21,22]. Their work reinforced the view that rigorous economic analysis could provide insights for business decision-making, though critics argued that this approach often oversimplified complex organizational and market realities [23].

2.3. Integration and Diversification of Strategic Management Theory

Beginning in the 1980s, Business Economics increasingly intersected with the emerging field of strategic management. Michael Porter’s influential work on competitive strategy drew extensively from industrial organization economics while focusing on practical strategic questions [24,25]. This integration demonstrated how economic analysis could inform strategic thinking, leading to new areas of inquiry such as competitive dynamics, industry analysis, and value chain optimization.

The resource-based view of the firm, developed by scholars such as Birger Wernerfelt and Jay Barney, further expanded the scope of Business Economics by incorporating insights from organizational theory and strategic management [26,27]. This perspective shifted attention from market-level analysis toward firm-specific resources and capabilities, creating new connections between economic theory and strategic practice.

Simultaneously, the field began to incorporate insights from behavioral economics and organizational psychology. Herbert Simon’s work on bounded rationality and satisficing behavior challenged traditional assumptions about rational decision-making, while prospect theory developed by Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky provided new frameworks for understanding managerial decision-making under uncertainty [28,29].

3. Current State and Scope of Business Economics

3.1. Pedagogical Content and Structure

Contemporary Business Economics courses in business schools typically cover a standardized set of topics derived from microeconomic and macroeconomic theory. A critical limitation of this conventional approach is that it typically begins with the simplistic ceteris paribus hypothesis to explain the law of demand and supply [30,31]. (All scientific analysis necessarily involves abstraction; none can fully dispense with ceteris paribus assumptions. While we can and must debate the quality of our abstractions, their presence remains both inevitable and methodologically justified. The crucial test for any alternative framework is whether it can explain the same phenomena more effectively [32,33].) While these concepts are undeniably critical for establishing fundamental economic understanding, they represent an oversimplification of real business dynamics [5,34]. The ceteris paribus assumption, though pedagogically convenient, fails to capture the uncertain, interconnected, and evolving nature of actual markets. This starting point inadvertently conditions students to think in terms of static, isolated relationships rather than dynamic systems characterized by uncertainty and feedback effects [35,36]. (While scarcity remains the backbone of all economic paradigms and must be retained in any repositioned course structure, the evolutionary perspective proposed in this paper addresses both scarcity and uncertainty as fundamental features of economic reality.) In particular, the microeconomic component usually includes demand and supply analysis, elasticity concepts, consumer behavior theory, production and cost functions, market structures, and pricing strategies [37]. The macroeconomic portion typically addresses national income accounting, monetary and fiscal policy, international trade, and exchange rate determination [38].

This content structure reflects the field’s historical development and institutional constraints rather than a coherent theoretical framework designed specifically for Business Economics education. Many instructors struggle with the challenge of making traditional economic concepts relevant to students who seek practical business skills rather than theoretical understanding [39]. The result is often a course that feels disconnected from students’ professional aspirations and contemporary business challenges.

The emphasis on mathematical formalization, inherited from mainstream economics, creates additional pedagogical challenges. While mathematical rigor can provide analytical precision, it may obscure the underlying economic intuition that business students need to develop. Many students complete Business Economics courses with knowledge of specific formulas and graphical analyses but limited ability to apply economic reasoning to novel business situations [40].

3.2. Central Theoretical Foundations and Methodological Approaches of Contemporary Business Economics

The theoretical foundation of Business Economics remains heavily influenced by neoclassical economic paradigms that emphasize equilibrium analysis, rational actors, and efficient markets. These assumptions, rooted in the ceteris paribus tradition of isolating variables, while mathematically convenient, often conflict with the dynamic, uncertain, and behaviorally complex environments that characterize actual business practice [6,41].

Methodologically, the field has traditionally relied on comparative static analysis, optimization techniques, and equilibrium modeling. While these approaches can provide critical understanding, they are poorly suited to analyzing processes of innovation, organizational learning, and systemic adaptation that are central to contemporary business strategy and competitiveness [10,42].

Recent decades have witnessed growing incorporation of empirical methods from applied economics, including econometric analysis, experimental approaches, and natural experiments [43]. However, these methodological advances have not been accompanied by corresponding theoretical syntheses that would make the field more relevant to business practice [44].

3.3. Integration Challenges with Business Disciplines

One of the most significant challenges facing Business Economics is its relationship with other business disciplines. Unlike economics departments, where Business Economics might represent a specialized field, business schools require integration across functional areas such as finance, marketing, operations, and strategy [45].

Finance theory—with its heavy mathematical foundation and focus on market efficiency, optimal portfolio construction, and corporate finance optimization—often conflicts with Business Economics approaches that emphasize market imperfections and strategic behavior [46,47]. Marketing, with its emphasis on consumer psychology and brand management, operates from fundamentally different assumptions about human behavior than traditional economic theory [48,49]. Operations management, increasingly focused on lean manufacturing and supply chain optimization, requires analytical frameworks that differ substantially from static economic models [50].

Strategic management represents perhaps the most natural area for integration, yet significant tensions remain. While strategic management emphasizes competitive advantage, innovation, and organizational capabilities, traditional Business Economics focuses on market-level analysis and assumes away many factors that strategic management considers central to firm performance [51]. Furthermore, the broader contemporary strategic analysis literature frequently demonstrates notable gaps in comprehending the evolutionary dynamics of organizational structural adaptation amid constantly shifting environmental conditions [52,53].

These integration challenges reflect deeper limitations of reductionist approaches that fail to capture systemic complexity. As scholars observe, many traditional strategic models are partial approaches that neglect the complex, embedded and dynamic nature of modern organizations [54,55]. This critique highlights how conventional Business Economics, by treating firms as isolated black boxes optimizing within static constraints, misses the complex interdependencies and feedback relationships that characterize actual business environments [2]. A systems perspective recognizes that organizational performance emerges from dynamic interactions between internal capabilities, external relationships, and institutional contexts [56,57].

3.4. Student Learning Outcomes and Professional Relevance

Assessment of student learning outcomes in Business Economics reveals significant gaps between course objectives and actual achievement. While students typically demonstrate competency in solving textbook problems involving demand and supply analysis or cost optimization, they often struggle to apply economic reasoning to complex business situations involving uncertainty, strategic interaction, and dynamic competition [58].

Critics of MBA education have highlighted the disconnect between traditional academic coursework and practical management needs [59,60,61,62], a critique that applies particularly to Business Economics given its heavy reliance on abstract theoretical models rather than practical business applications. This finding is particularly troubling given the substantial time allocation to economics-related content in most MBA curricula and the potential value that economic reasoning could provide for business decision-making.

The disconnect between course content and professional relevance appears to stem from several factors: overemphasis on theoretical abstraction at the expense of practical application, reliance on static models that poorly capture dynamic business environments, and insufficient attention to the institutional and organizational contexts within which business decisions occur [19,45]. Fundamentally, these discontinuities stem from the challenge of reconciling the deductive, equilibrium-based framework of conventional economic theory with the inductive, process-oriented methodologies prevalent in contemporary management science [63,64].

4. Evolutionary Economics as a Framework for Business Economics

4.1. Foundational Principles of Evolutionary Economics

Evolutionary economics offers a fundamentally different approach to understanding economic phenomena that may be more suitable for business education than traditional neoclassical frameworks. Rather than assuming equilibrium and rational optimization, evolutionary economics focuses on processes of variation, selection, and retention that drive economic change over time [10,65]. (This approach contrasts sharply with conventional Business Economics pedagogy that begins with ceteris paribus assumptions, artificially holding variables constant to derive simplified relationships. Evolutionary economics does not abandon the fundamental concept of scarcity but reframes it within a dynamic context where resources, capabilities, and even preferences evolve across chronological periods. Despite the development of sophisticated dynamic microeconomic models, the pedagogical landscape of Business Economics remains overwhelmingly dominated by reductive neoclassical frameworks in curricula globally [66,67]).

The core insight of evolutionary economics is that economic systems are complex adaptive systems characterized by ongoing innovation, learning, and structural change [68]. Evolutionary economics inherently represents a systems-oriented approach to understanding economic phenomena [69]. Rather than treating the economy as simply the sum of individual decisions, evolutionary economics recognizes economic systems as complex adaptive systems where emergent behavior arises from multi-level interactions [6,70,71]. In this context, firms are understood not as profit-maximizing black boxes but as repositories of organizational routines, capabilities, and knowledge that evolve through experience and competitive selection [10,42,72].

This perspective emphasizes several key principles that distinguish evolutionary economics from mainstream approaches. First, firms and markets are viewed as dynamic systems that continuously adapt and evolve rather than static entities seeking equilibrium. Second, innovation and learning are treated as central, endogenous processes rather than exogenous factors. Third, heterogeneity among firms is seen as a source of competitive advantage rather than a deviation from optimal behavior [73,74].

The evolutionary approach to economics explicitly draws from biological evolutionary theory, though it is crucial to understand both the parallels and distinctions between biological and economic evolution. The core biological concepts of variation, selection, and retention translate directly into economic phenomena, where firms exhibit diverse strategies (variation), markets select for successful approaches (selection), and organizational routines preserve effective practices (retention) [75].

However, unlike biological evolution, economic evolution operates through Lamarckian as well as Darwinian mechanisms—firms can intentionally acquire and transmit beneficial traits within their lifetime [76]. This allows for directed learning and purposeful adaptation, making economic evolution potentially faster and more responsive than its biological counterpart. Additionally, the units of selection in economics—routines, capabilities, and business models—are more fluid and transferable than genes, enabling horizontal transfer of innovations across firms and industries [77]. This biological lens reveals markets not as mechanical systems tending toward equilibrium, but as living systems characterized by continuous adaptation and emergent ecosystemic order. (Understanding these biological underpinnings could help students grasp why markets exhibit patterns similar to ecosystems: niche specialization, co-evolution between firms and their environment, punctuated equilibria in industry structures, and “Red Queen” dynamics where firms must continually innovate merely to maintain their relative position [78]).

4.2. Macro–Meso–Micro Integration in Evolutionary Economics

One of the most promising aspects of evolutionary economics for business education is its integration of macro-, meso-, and micro-level analysis. This framework—developed by scholars such as Kurt Dopfer and expanded by others—offers a coherent way to understand how individual firm strategies, industry dynamics, and macroeconomic trends interconnect [11,79,80,81,82].

At the micro level, evolutionary economics focuses on organizational routines, capabilities, and learning processes within individual firms. This perspective emphasizes how firms develop distinctive competencies through experience and how these capabilities influence competitive performance. Unlike traditional microeconomic theory, which treats firms as quasi-stable production functions, evolutionary economics recognizes firms as dynamic, adaptive organizations with distinct developmental trajectories [83,84].

The meso level addresses industry and market dynamics, including processes of technological change, competitive selection, and institutional evolution. This analysis examines how innovations emerge and diffuse through markets, how competitive advantage shifts among firms over time, and how industries evolve through cycles of stability and transformation. The meso level provides crucial bilateral links between individual firm behavior and broader economic trends [85,86,87].

At the macro level, evolutionary economics examines how technological change, institutional development, and systemic innovation drive long-term economic growth and structural transformation. This perspective emphasizes the role of knowledge creation, network effects, and systemic competitiveness in determining national and regional economic performance [88,89,90].

4.3. Applications for Business Strategy and Decision-Making

Evolutionary economics provides several analytical frameworks that are directly relevant to business strategy and decision-making processes. The concept of dynamic capabilities, developed by David Teece and others, offers a way of understanding how firms build and deploy resources to achieve competitive advantage in changing environments [42,91].

This framework emphasizes the importance of organizational learning, knowledge management, and adaptive capacity rather than static resource optimization. Firms succeed by developing capabilities to sense opportunities, seize new market positions, and reconfigure their operations in response to changing circumstances. This perspective provides practical guidance for managers dealing with technological change, market uncertainty, and competitive dynamics [84,92]. Through this evolutionary lens of innovation, we can better discern the ongoing dialectical interplay among strategic vision, technological proficiency, and managerial competence that underlies all effective organizational innovation [72].

Innovation management represents another area where evolutionary economics offers useful insights into business education. Rather than treating innovation as an exogenous factor, evolutionary economics examines the organizational and institutional conditions that support innovative activity. This includes analysis of research and development strategies, technology transfer processes, and the management of innovation ecosystems [93,94].

The evolutionary perspective also provides frameworks for understanding competitive dynamics and strategic interaction. Rather than assuming perfect competition or monopolistic competition, evolutionary economics examines how firms compete through differentiation, innovation, and capability development. This includes analysis of competitive response patterns, strategic groups, and industry evolution [95,96].

4.4. Institutional and Network Perspectives

Evolutionary economics places strong emphasis on institutional factors and network relationships that shape business behavior and economic outcomes. This perspective recognizes that firms operate within complex institutional environments, including legal systems, cultural norms, and regulatory frameworks that influence strategic choices and competitive dynamics [97,98].

The analysis of business networks and ecosystems has become increasingly important for understanding contemporary business strategy. Evolutionary economics provides frameworks for analyzing how firms position themselves within value networks, how they manage relationships with suppliers and customers, and how they participate in innovation ecosystems, all occurring within an ongoing process of reconfiguration and adjustment [99,100,101,102].

This institutional and network perspective is particularly relevant for business students who need to understand how to operate effectively within complex organizational and market environments. Traditional economic theory, with its emphasis on market transactions and price mechanisms, provides limited guidance for managing relationships, building trust, and navigating institutional complexity in an increasingly fluid and evolving environment [103,104].

4.5. Complexity Theory and Social Systems Integration

Business Economics can greatly benefit by incorporating insights from complexity science and Niklas Luhmann’s social systems theory into its evolutionary framework. Evolutionary economics already views the economy as a complex adaptive system; here we extend that view with concepts such as emergence (novel properties arising from interactions across firms and levels), nonlinearity (disproportionate effects of small changes), and self-organization (spontaneous order arising without central control). In social systems theory, business organizations and markets are seen as open systems that interact with their environment yet maintain an operational closure that helps them reduce complexity. Luhmann’s perspective introduces ideas of complexity reduction (how organizations simplify the overwhelming complexity of the environment through structures and processes), system recursivity (systems self-reproduce their components and structure over time), and distinctions between structure and function in understanding organizational behavior [105].

Embracing these concepts implies recognizing that business systems actively filter and interpret information to survive and develop, suggesting a carrying capacity for complexity that any business model or organization can handle. For example, Valentinov argues that organizations face a complexity–sustainability trade-off, balancing the complexity they absorb with the need for sustainable operation [106].

Similarly, the notion of autopoiesis (self-production) from Luhmann’s theory, applied to evolutionary economics, highlights that firms and economic institutions continuously regenerate themselves in response to environmental feedback rather than simply moving toward equilibrium [107,108]. Integrating these ideas enriches the evolutionary framework by emphasizing that business ecosystems are not only evolutionary and adaptive but also self-referential and governed by emergent rules.

While these complexity and systems-theoretic concepts are still relatively new to economics in general and to Business Economics in particular, incorporating them can initiate a long-term research program. It will require substantial theoretical elaboration to fully merge complexity theory with a new stem of evolutionary business economics, but doing so promises a deeper understanding of phenomena like emergent market behaviors, nonlinear industry dynamics, and the self-organizing characteristics of business ecosystems [109,110].

4.6. Evolution of Organizational Forms, Ownership, and Business Models

A comprehensive evolutionary approach to Business Economics must account for the historical emergence and development of new organizational forms, including variations in ownership and governance, as well as evolving business models. Traditional Business Economics often treats the firm as a given unit (typically an investor-owned corporation), but an evolutionary perspective asks how different organizational forms arise, compete, and sometimes dominate over time. For instance, capitalist economies have seen a variety of ownership forms—investor-owned firms, state-owned enterprises, family businesses, cooperatives, nonprofit organizations, etc.—each of which can be understood as adaptations to particular environmental niches and selection pressures in the market [111]. The evolutionary dynamics of organizational form are illuminated by Coase’s analysis of transaction costs, which reveals how firms emerge and persist as adaptive responses to market frictions: hierarchical coordination evolves as a competitive advantage when it reduces the costs of repeated market exchanges, helping explain why certain organizational forms flourish in specific economic environments while others decline [112].

The modern investor-owned corporation became the dominant form in many economies, but its prevalence is itself an outcome of an evolutionary process favoring certain efficiency and capital-raising advantages. At the same time, alternatives like cooperatives or platform-based network organizations gain ground when conditions favor trust, local knowledge, or network externalities that traditional firms cannot capture [113,114].

From a governance perspective, evolutionary Business Economics examines how governance structures (for example, centralized vs. decentralized decision-making, shareholder-centric vs. stakeholder-oriented boards) confer advantages or disadvantages in different contexts, leading to a selection of certain governance models over others. Similarly, business models—that is, the ways firms create and capture value—evolve in response to strategic, managerial, and technological changes and shifting consumer preferences. An evolutionary curriculum would include how business models themselves undergo variation and selection: firms experiment with new models (such as platform-based services, subscription models, or freemium pricing), and the market environment selects for models that best fit the current landscape [115]. As Velu demonstrates, a systems perspective can elucidate how business models co-evolve with their broader ecosystem [116].

Understanding these evolutionary dynamics of organizational form and business models is crucial for appreciating the long-run development of capitalist business systems. Business Economics education should therefore introduce students to why, for example, the investor-owned corporation became predominant (e.g., the ability to raise capital and scale rapidly), and under what conditions alternative forms like cooperatives or social enterprises emerge and thrive [117].

This also involves recognizing that the institutional environment (legal frameworks, cultural norms, capital markets) exerts selection pressure favoring certain forms at different times. By analyzing historical shifts—such as the rise of the multidivisional corporation in the mid-20th century or the recent proliferation of platform-based firms—students can see evolutionary principles at work in shaping which types of businesses succeed. In a repositioned framework, topics like ownership forms and business model innovation would be explicitly discussed as evolutionary outcomes, encouraging students to think about how firms and industries may look very different in the future as new forms emerge.

4.7. Behavioral Economics and Evolutionary Business Economics

An evolutionary approach to Business Economics is incomplete without accounting for behavioral economics and the “behavioral theory of the firm.” Classic works in this area significantly inform how real firms make decisions and adapt over time. For example, Cyert and March’s “Behavioral Theory of the Firm” challenged the traditional assumption of profit-maximizing firms by documenting how companies actually behave—through satisficing (seeking satisfactory rather than optimal outcomes) and using organizational routines to make decisions under uncertainty [118].

Herbert Simon’s research introduced the notion of bounded rationality, recognizing that managers have cognitive limitations and cannot survey all possible options; instead, they make decisions with limited information and computational ability [119,120]. Simon also described heuristics and simple decision rules that organizations employ (“administrative man” instead of the hyper-rational “economic man” [120]), which dovetails with evolutionary ideas of firms developing rules of thumb that work well enough in their environment.

Behavioral insights complement evolutionary economics by explaining the micro-level decision processes that generate variation in firm behavior. While evolutionary theory often emphasizes population-level dynamics (variation, selection, retention), behavioral economics provides a lens on how individual and organizational decisions generate those variations. For instance, biases and heuristics can lead some firms to innovate or strategize differently, creating the diversity on which market selection acts. Key behavioral concepts such as reference dependence (outcomes judged relative to a reference point), framing effects (choices depend on how problems are framed), cognitive biases (systematic deviations from rational calculation, like overconfidence), and time inconsistency (present bias) are highly relevant to business decision-making and strategy [28,121]. An evolutionary Business Economics curriculum would highlight, for example, that managers often weigh losses more heavily than gains (loss aversion) when making investment decisions, which can influence a firm’s strategic evolution in competitive markets.

It would also examine how organizations learn and adapt: Levitt and March’s work on organizational learning demonstrated that firms evolve routines based on historical experiences and that this learning is “routine-based, history-dependent, and target-oriented,” leading to both competencies and inertia in organizational change [122]. By incorporating such behavioral findings, Business Economics students can better understand why firms may not always choose the “optimal” strategy predicted by neoclassical models and how boundedly rational behavior can cumulatively affect industry evolution (e.g., widespread over-optimism during a tech bubble followed by a corrective selection event) [123,124].

Looking forward, the integration of behavioral and evolutionary perspectives could pave the way for a richer “behavioral evolutionary theory of the firm.” In such a synthesis, one might envision firms as evolving entities whose routines and strategies are shaped not only by external selection pressures but also by internal cognitive and social processes. For example, firms adapt to their environments through both deliberate strategy changes and incremental learning from failures (as evolutionary theory suggests), and the manner in which they adapt is influenced by how managers perceive and react to feedback, which is a behavioral issue. Substantial conceptual work remains to be performed in this area, but current evidence suggests that blending behavioral economics with evolutionary theory can yield models of business behavior that are both more realistic and more predictive of phenomena like innovation, strategic change, and organizational resilience. The curriculum implications are that beyond teaching profit maximization and equilibrium, business students should also study how real decisions are made within firms (with all their human limitations) and how those decisions aggregate into evolutionary outcomes over time.

5. Wrapping Up: Toward an Evolutionary Business Economics Curriculum

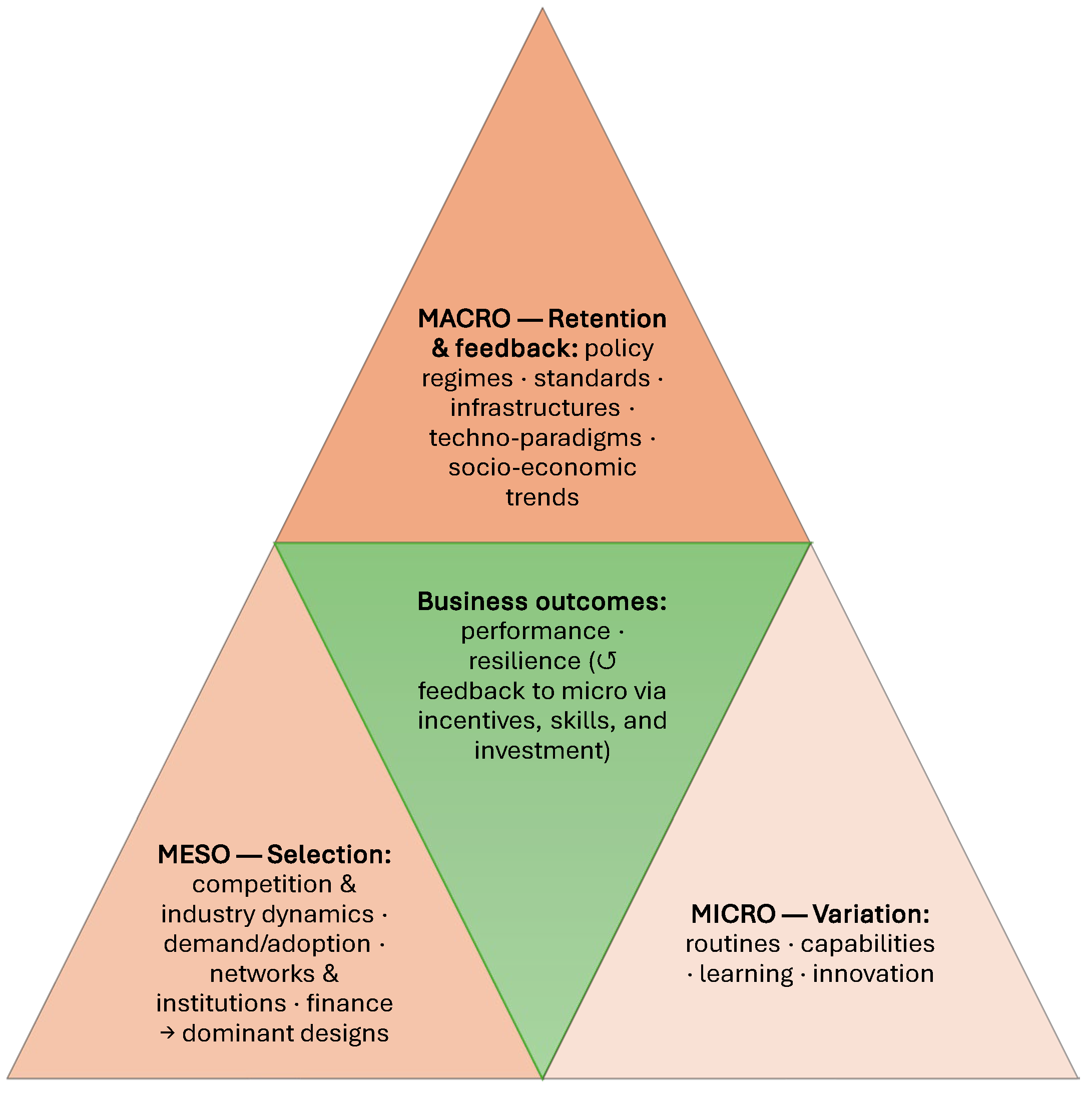

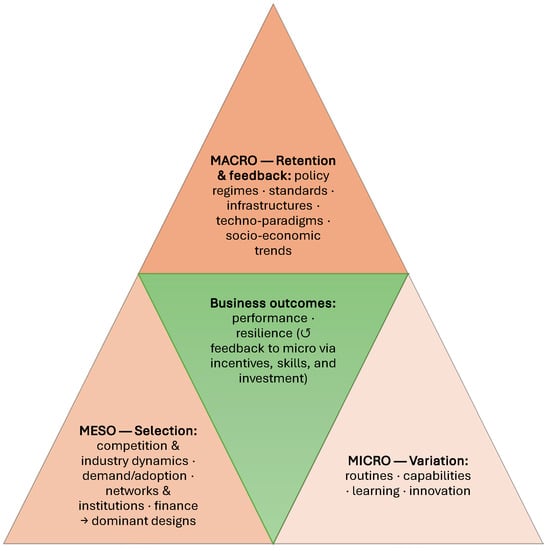

The evolutionary framework developed above can now be translated into practical curriculum guidelines. Before delving into these, it is helpful to summarize the proposed systems-based evolutionary approach to Business Economics. Figure 1 distills the paper’s core proposal into a single systems evolutionary schematic: micro-level routines generate variation; meso-level structures select among competing strategies, technologies, managerial style, and different business models; macro-level dynamics shape—and are reshaped by—industry evolution and aggregate outcomes. In other words, the figure is a visual condensation of the curricular moves detailed in Table 1. The table operationalizes the seven pillars developed in Section 4.1, Section 4.2, Section 4.3, Section 4.4, Section 4.5, Section 4.6 and Section 4.7 as counterarguments to the status quo syllabus and translates each into concrete design choices (topics, methods, and assessments) for Business Economics. Readers can thus scan Table 1 for actionable change and use Figure 1 to keep the systemic logic in view as they redesign courses. (For a week-by-week implementation aligned to common 12-week semesters, see Appendix A, Table A1).

Figure 1.

Evolutionary, Systems-Based Business Economics (Proposed Framework). (Note: Variation at micro generates heterogeneity; meso mechanisms select and amplify; macro institutions/technologies retain and feedback, yielding circular causality, path dependence, and persistent disequilibrium.).

Table 1.

Evolutionary Counterarguments to the Conventional Business Economics Curriculum.

Business outcomes emerge from multi-level interactions: micro-level routines and innovations (variation) feed into meso-level competitive, network, and institutional selection mechanisms; macro-level techno-paradigmatic and socio economic trends both condition and absorb these outcomes (retention and feedback). The framework emphasizes circular causality, path dependence, and continuous disequilibrium consistent with evolutionary economics and complexity science [6,10,69,71,83].

The framework advanced here could re-center Business Economics on change, heterogeneity, and multi-level embedding. It consolidates streams that are often taught separately—evolutionary theory of the firm [10], macro–meso–micro integration [81,82], dynamic capabilities [42,92], sectoral systems and national innovation systems [85,88], institutional economics and networks [98,103,104], and complexity-based modeling [6,71,72]—into a single curricular architecture. Relative to conventional syllabi, which remain anchored in equilibrium and isolated agents, the proposed architecture aligns how we teach with how business actually unfolds: through routines, feedback, institutional rules, and ecosystem interdependence [8,58].

Conceptually, the paper’s “new finding” is an integrative curriculum design principle: Business Economics becomes the system’s evolutionary core of management education rather than a thin micro- and macro-survey. This complements and extends prior efforts that imported pieces of economics into strategy (e.g., Input-Output-based industry analysis [8,25]) or strategy into economics (e.g., capabilities [42]) by providing the linkage logic—the meso level and evolutionary dynamics—that make the pieces cohere [99,102]. It also operationalizes complexity and learning through pedagogical technologies (system dynamics, agent-based demonstrations, longitudinal cases) that help students think in feedback rather than snapshots [65].

Finally, this repositioned approach offers a practical, modular toolkit that instructors can adopt incrementally (see Figure 1, Table 1, and Appendix A, Table A1). Begin by embedding macro–meso–micro “maps” within existing topics (Table 1, Row 2); then scaffold toward analyses of dynamic capabilities and institutional/network contexts (Rows 3–4); and culminate with simulation-based learning and business-model experimentation (Rows 5–6). Case selection should prioritize examples where strict ceteris paribus assumptions break down—such as market disruptions involving simultaneous changes in technology, regulation, and consumer behavior—to demonstrate the limitations of static analysis and the value of evolutionary thinking. Throughout, behavioral scaffolds (Row 7) ensure that decision processes—the generators of variation—are addressed explicitly.

6. Conclusions

This paper traced the emergence of Business Economics, diagnosed the limitations of its conventional equilibrium-centric syllabus, and argued for an evolutionary, systems-based reconceptualization that integrates micro routines, meso industry/institutional structures, and macro technological–economic trends. Building on established literature in evolutionary theory, dynamic capabilities, sectoral and national innovation systems, institutional/network perspectives, and complexity science, we proposed a schema that makes the multi-level causal architecture explicit and a companion table that translates seven evolutionary pillars (Section 4.1, Section 4.2, Section 4.3, Section 4.4, Section 4.5, Section 4.6 and Section 4.7) into concrete design choices for teaching. In short, Business Economics should be redesigned as a systems-evolutionary core—organized around variation–selection–retention and macro–meso–micro embedding—so that students learn to reason about process, feedback, and adaptation rather than quasi-static equilibrium.

For instructors and curriculum committees, adopting this framework means shifting learning outcomes from “solve stylized optimization problems under ceteris paribus conditions” to “explain and navigate dynamic competitive processes with multiple simultaneous changes and uncertainty,” adding cross-level mapping, capability diagnostics, institutional/network analysis, and simulation based reasoning to the course toolbox. It aligns Business Economics with contemporary strategic thinking and innovation management while preserving foundational economic literacy. It also provides accreditation-relevant evidence of integrative thinking and experiential pedagogy (e.g., AACSB’s emphasis on cross-disciplinary learning and applied competence [125]).

Naturally, this is a conceptual contribution. We have not presented empirical evaluations of learning gains or cross-institutional comparisons, and the framework deliberately privileges evolutionary, systems, and complexity perspectives that instructors may rebalance to fit local contexts and student preparation. Feasibility will also vary with program resources and faculty capability, especially for simulations and network analyses.

Future work can test and refine the proposal through (1) design-based research comparing course sections that adopt the seven-row curriculum against controls on problem transfer, causal reasoning, and strategic adaptability; (2) development and sharing of open simulation artifacts (system-dynamics stock–flow models and simple agent-based labs) aligned with each pillar; and (3) multi-institution case repositories tracing capability evolution, institutional shifts, and ecosystem dynamics over time. Longer-term research can examine whether exposure to a systems-evolutionary Business Economics predicts higher-quality decision-making in dynamic, uncertain environments.

The implications of this evolutionary repositioning extend beyond pedagogical innovation. What we are witnessing—and what this paper seeks to advance—represents more than incremental curriculum reform. The transformation from equilibrium-based, mechanistic Business Economics to an evolutionary, systems-based approach embodies elements of what Kuhn described as a paradigm shift in scientific thinking [126]. Just as physics transitioned from Newtonian to quantum mechanics and biology from fixed species to evolutionary theory, Business Economics pedagogy now confronts a similar inflection point. This practical case illustrates how paradigm shifts manifest in applied fields: through gradual recognition that existing frameworks—here, the ceteris paribus tradition—fail to capture essential features of their subject matter.

The urgency of this shift becomes apparent when we consider how equilibrium-based models have struggled to explain financial crises, technological disruptions, and sustainability transitions [127]. By embracing evolutionary principles, Business Economics joins a broader movement toward complexity-aware economic thinking. This repositioning may mark the beginning of a larger transformation in economics education, where static optimization gives way to adaptive learning, where isolated analysis yields to systemic thinking, and where the comfortable fiction of equilibrium surrenders to the challenging reality of perpetual change.

If the old course taught students to take snapshots of a moving world, the redesigned course teaches them to draw the motion—to see firms as evolving bundles of routines, industries as shifting ecologies, and economies as complex systems that learn. That, ultimately, is the practical promise of an evolutionary Business Economics: graduates who can reason in feedback, design for adaptation, and act with humility in the face of change.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Because most university courses are organized in twelve teaching weeks, the proposed sequencing below is presented in a 12-week format. This alignment allows instructors to adopt the design directly within a standard semester while keeping week-by-week learning aims clear and assessable. Programs with different calendars can compress or extend the sequence without breaking its logic.

Table A1.

Conventional versus Evolutionary Business Economics (12-Week Structure).

Table A1.

Conventional versus Evolutionary Business Economics (12-Week Structure).

| Week | Conventional Business Economics Curriculum | Evolutionary Business Economics Curriculum (Proposed) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Introduction to Microeconomics: Supply and Demand, Elasticity | Introduction to Evolutionary Economics: Systems Thinking and Dynamic Change |

| 2 | Consumer Behavior: Utility Maximization | Firm Behavior: Routines and Capabilities as Evolutionary Traits |

| 3 | Production and Cost Functions | Micro-Level Analysis: Organizational Learning and Innovation |

| 4 | Perfect Competition and Market Structures | Evolution of Market Structures: Schumpeterian Competition and Innovation |

| 5 | Monopoly and Oligopoly | Dynamic Capabilities and Competitive Advantage over Time |

| 6 | Pricing Strategy and Market Power | Firms in Context: Institutional Networks and Ecosystem Dynamics |

| 7 | National Income, GDP, and Macroeconomics | Macro–Meso–Micro Integration: Connecting Firm Strategies with Industry Evolution |

| 8 | Fiscal and Monetary Policy | Technological and Institutional Evolution: Feedback Loops and Systemic Change |

| 9 | International Trade and Exchange Rates | Global Business Ecosystems: Co-evolution of Business Models and Institutional Change |

| 10 | Welfare Economics and Public Policy | Complexity Theory and System Dynamics in Business Strategy |

| 11 | Market Failures and Government Intervention | Business Models as Evolutionary Outcomes: Comparative Study of Organizational Forms |

| 12 | Review and Application: Case Studies | Simulation and Strategy: Business Decisions in Evolving Systems |

References

- Checkland, P. Systems Thinking, Systems Practice; John Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1999; ISBN 978-0-471-98606-5. [Google Scholar]

- Senge, P.M. The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization; Doubleday/Currency: New York, NY, USA, 1990; ISBN 978-0-385-26094-7. [Google Scholar]

- Meadows, D. Thinking in Systems: International Bestseller; Chelsea Green Publishing: White River Junction, VT, USA, 2008; ISBN 978-1-60358-148-6. [Google Scholar]

- Weintraub, E.R. Methodology Doesn’t Matter, but the History of Thought Might. Scand. J. Econ. 1989, 91, 477–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colander, D. The Death of Neoclassical Economics. J. Hist. Econ. Thought 2000, 22, 127–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arthur, W.B. Complexity and the Economy; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2015; ISBN 978-0-19-933429-2. [Google Scholar]

- Beinhocker, E.D. The Origin of Wealth: Evolution, Complexity, and the Radical Remaking of Economics; Harvard Business Press: Brighton, MA, USA, 2006; ISBN 978-1-57851-777-0. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M.E. Towards a Dynamic Theory of Strategy. Strateg. Manag. J. 1991, 12, 95–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. Business Models, Business Strategy and Innovation. Long Range Plan. 2010, 43, 172–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, R.R.; Winter, S. An Evolutionary Theory of Economic Change; The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA; London, UK, 1982; ISBN 978-0-674-27228-6. [Google Scholar]

- Dopfer, K.; Potts, J. The General Theory of Economic Evolution; Routledge: London, UK, 2008; ISBN 978-0-415-27942-0. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, A. Principles of Economics, 8th ed.; Macmillan: London, UK, 2013; ISBN 978-1-137-37526-1. [Google Scholar]

- Penrose, E.T. The Theory of the Growth of the Firm; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Cruikshank, J.L. A Delicate Experiment: The Harvard Business School 1908–1945; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1987; ISBN 978-0-87584-135-9. [Google Scholar]

- Sass, S.A. The Pragmatic Imagination: A History of the Wharton School, 1881–1981; University of Pennsylvania Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2016; ISBN 978-1-5128-0660-1. [Google Scholar]

- Dean, J. Managerial Economics; Prentice-Hal: Kent, OH, USA, 1951. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, D.; Servalli, S. Economia Aziendale and Financial Valuations in Italy: Some Contradictions and Insights. Account. Hist. 2011, 16, 291–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zappa, G. Tendenze Nuove Negli Studi di Ragioneria; Istituto Editoriale Scientifico: Milano, Italy, 1927. [Google Scholar]

- Khurana, R. From Higher Aims to Hired Hands: The Social Transformation of American Business Schools and the Unfulfilled Promise of Management as a Profession; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2010; ISBN 978-1-4008-3086-2. [Google Scholar]

- Baumol, W.J. Economic Theory and Operations Analysis; Prentice-Hall: Kent, OH, USA, 1971; ISBN 978-0-13-227157-8. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, M. Capitalism and Freedom; Chicago University Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, G.S. The Economic Approach to Human Behavior; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1976; ISBN 978-0-226-04111-7. [Google Scholar]

- Galbraith, J.K. Economics in Perspective: A Critical History; Houghton Mifflin: Boston, MA, USA, 1987; ISBN 978-0-395-35572-5. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M.E. Competitive Strategy: Techniques for Analyzing Industries and Competitors; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M.E. Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Wernerfelt, B. A Resource-Based View of the Firm. Strateg. Manag. J. 1984, 5, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D.; Tversky, A. Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision under Risk. Econometrica 1979, 47, 263–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, H.A. Models of Man: Social and Rational; Mathematical Essays on Rational Human Behavior in Society Setting; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Lawson, T. Economics and Reality; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 1997; ISBN 0-429-22946-1. [Google Scholar]

- Hodgson, G.M. How Economics Forgot History: The Problem of Historical Specificity in Social Science; Economics as social theory; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2002; ISBN 978-0-415-25716-9. [Google Scholar]

- Mäki, U. Missing the World. Models as Isolations and Credible Surrogate Systems. Erkenntnis 2009, 70, 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrik, D. Economics Rules: The Rights and Wrongs of the Dismal Science; W. W. Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA, 2015; ISBN 978-0-393-24642-1. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, R.; Myatt, T. The Economics Anti-Textbook: A Critical Thinker’s Guide to Microeconomics; Bloomsbury Publishing: London, UK, 2010; ISBN 978-1-84813-548-2. [Google Scholar]

- Romer, P.M. Mathiness in the Theory of Economic Growth. Am. Econ. Rev. 2015, 105, 89–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keen, P.S. Debunking Economics: The Naked Emperor Dethroned? Zed Books Ltd.: London, UK, 2011; ISBN 978-1-84813-995-4. [Google Scholar]

- Samuelson, W.F.; Marks, S.G.; Zagorsky, J.L. Managerial Economics; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2021; ISBN 978-1-119-55491-2. [Google Scholar]

- Mankiw, N.G. Principles of Economics, 2nd ed.; Harcourt College: Fort Worth: Fort Worth, TX, USA, 2000; ISBN 978-0-03-025951-7. [Google Scholar]

- Colander, D. The Making of an Economist Redux. J. Econ. Perspect. 2005, 19, 175–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegfried, J.J.; Bartlett, R.L.; Hansen, W.L.; Kelley, A.C.; McCloskey, D.N.; Tietenberg, T.H. The Status and Prospects of the Economics Major. J. Econ. Educ. 1991, 22, 197–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaler, R.H. Misbehaving: The Making of Behavioural Economics; Penguin UK: London, UK, 2015; ISBN 978-0-14-196615-1. [Google Scholar]

- Teece, D.J.; Pisano, G.; Shuen, A. Dynamic Capabilities and Strategic Management. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 509–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angrist, J.D.; Pischke, J.-S. Mostly Harmless Econometrics: An Empiricist’s Companion; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2009; ISBN 978-0-691-12035-5. [Google Scholar]

- Thaler, R.; Sunstein, C.R. Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 2008; ISBN 978-0-300-12223-7. [Google Scholar]

- Ghoshal, S. Bad Management Theories Are Destroying Good Management Practices. Acad. Manag. Learn. Educ. 2005, 4, 75–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shleifer, A.; Vishny, R.W. A Survey of Corporate Governance. J. Financ. 1997, 52, 737–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fama, E.F.; French, K.R. The Cross-Section of Expected Stock Returns. J. Financ. 1992, 47, 427–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotler, P.; Keller, K.L. Marketing Management; Pearson Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2006; ISBN 978-0-13-145757-7. [Google Scholar]

- Aaker, D.A. Managing Brand Equity: Capitalizing on the Value of a Brand Name; Free Press: New York, NY, USA; Maxwell Macmillan Canada: Toronto, ON, Canada; Maxwell Macmillan International: New York, NY, USA, 1991; ISBN 978-0-02-900101-1. [Google Scholar]

- Chopra, S.; Meindl, P. Supply Chain Management: Strategy, Planning, and Operation; Pearson: London, UK, 2016; ISBN 978-0-13-380020-3. [Google Scholar]

- Rumelt, R.P.; Schendel, D.; Teece, D.J. Fundamental Issues in Strategy: A Research Agenda; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1994; ISBN 978-0-87584-343-8. [Google Scholar]

- Durand, R.; Grant, R.M.; Madsen, T.L. The Expanding Domain of Strategic Management Research and the Quest for Integration. Strateg. Manag. J. 2017, 38, 4–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helfat, C.E.; Peteraf, M.A. Managerial Cognitive Capabilities and the Microfoundations of Dynamic Capabilities. Strateg. Manag. J. 2015, 36, 831–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.; Siggelkow, N. Contextuality Within Activity Systems and Sustainability of Competitive Advantage. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2008, 22, 34–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mintzberg, H.; Ahlstrand, B.; Lampel, J.B. Strategy Safari: The Complete Guide Through the Wilds of Strategic Management, 2nd ed.; Pearson Education Canada: Harlow, UK, 2008; ISBN 978-0-273-71958-8. [Google Scholar]

- Ackoff, R.L. Re-Creating the Corporation: A Design of Organizations for the 21st Century; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1999; ISBN 978-0-19-512387-6. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, M.C. Systems Thinking: Creative Holism for Managers; CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform: North Charleston, SC, USA, 2017; ISBN 978-1-5485-8792-5. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, W.L.; Salemi, M.K.; Siegfried, J.J. Use It or Lose It: Teaching Literacy in the Economics Principles Course. Am. Econ. Rev. 2002, 92, 463–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeffer, J.; Fong, C.T. The End of Business Schools? Less Success Than Meets the Eye. Acad. Manag. Learn. Educ. 2002, 1, 78–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mintzberg, H. Managers, Not MBAs: A Hard Look at the Soft Practice of Managing and Management Development; Berrett-Koehler Publishers: Oakland, CA, USA, 2004; ISBN 978-1-57675-275-3. [Google Scholar]

- Bennis, W.G.; O’toole, J. How Business Schools Lost Their Way. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2005, 83, 96–104. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, L.W.; McKibbin, L.E. Management Education and Development: Drift or Thrust into the 21st Century? McGraw-Hill Book Company: Columbus, OH, USA, 1988; ISBN 978-0-07-050521-6. [Google Scholar]

- Hoskisson, R.E.; Hitt, M.A.; Wan, W.P.; Yiu, D. Theory and Research in Strategic Management: Swings of a Pendulum. J. Manag. 1999, 25, 417–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ven, A.H.V. de Engaged Scholarship: A Guide for Organizational and Social Research; OUP Oxford: Oxford, UK, 2007; ISBN 978-0-19-922629-0. [Google Scholar]

- Hodgson, G.M. Economics and Evolution: Bringing Life Back into Economics; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 1993; ISBN 978-0-472-08423-4. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, R.R.; Winter, S. Evolutionary Theorizing in Economics. J. Econ. Perspect. 2002, 16, 23–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witt, U. What Is Specific about Evolutionary Economics? J. Evol. Econ. 2008, 18, 547–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzinikolaou, D.; Vlados, C. Evolutionary Economics and the Stra.Tech.Man Approach of the Firm into Globalization Dynamics. Bus. Manag. Econ. Res. 2019, 5, 146–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlados, C.; Deniozos, N.; Chatzinikolaou, D.; Demertzis, M. Towards an Evolutionary Understanding of the Current Global Socio-Economic Crisis and Restructuring: From a Conjunctural to a Structural and Evolutionary Perspective. Res. World Econ. 2018, 9, 15–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Holland, J.H. Hidden Order: How Adaptation Builds Complexity; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1995; ISBN 978-0-201-40793-8. [Google Scholar]

- Sterman, J. Business Dynamics: Systems Thinking and Modeling for a Complex World; Irwin/McGraw-Hill: Columbus, OH, USA, 2000; ISBN 978-0-07-231135-8. [Google Scholar]

- Vlados, C.; Chatzinikolaou, D. From Business Ecosystems to Firm Physiology: The Strategy—Technology—Management Evolutionary Synthesis. J. Entrep. 2025, 34, 268–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metcalfe, J.S. Evolutionary Economics and Creative Destruction; The Graz Schumpeter lectures; digital print; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2006; ISBN 978-0-415-40648-2. [Google Scholar]

- Foster, J. From Simplistic to Complex Systems in Economics. Camb. J. Econ. 2005, 29, 873–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgson, G.M.; Knudsen, T. Darwin’s Conjecture: The Search for General Principles of Social and Economic Evolution; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA; London, UK, 2010; ISBN 978-0-226-34690-8. [Google Scholar]

- Hodgson, G.M. Darwinism in Economics: From Analogy to Ontology. J. Evol. Econ. 2002, 12, 259–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldrich, H.E.; Hodgson, G.M.; Hull, D.L.; Knudsen, T.; Mokyr, J.; Vanberg, V.J. In Defence of Generalized Darwinism. J. Evol. Econ. 2008, 18, 577–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kauffman, S.A. The Origins of Order: Self-Organization and Selection in Evolution; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1993; ISBN 978-0-19-505811-6. [Google Scholar]

- Chatzinikolaou, D.; Vlados, C. International Political Economy, Business Ecosystems, Entrepreneurship, and Sustainability: A Synthesis on the Case of the Energy Sector. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzinikolaou, D.; Kubus, R. Macro–Meso–Micro: An Integrative Framework for Evolutionary Economics and Sustainable Transitions. Sustainability 2025, 17, 9480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dopfer, K.; Foster, J.; Potts, J. Micro-Meso-Macro. J. Evol. Econ. 2004, 14, 263–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzinikolaou, D.; Vlados, C. Towards an Enriched Research Approach to Evolutionary Economics: The Orientation of Macro-Meso-Micro Dynamics and Critical Realism. Econ. Altern. 2025, 31, 613–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, S.G. Understanding Dynamic Capabilities. Strateg. Manag. J. 2003, 24, 991–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. Explicating Dynamic Capabilities: The Nature and Microfoundations of (Sustainable) Enterprise Performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2007, 28, 1319–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malerba, F. Sectoral Systems of Innovation and Production. Res. Policy 2002, 31, 247–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saviotti, P.; Metcalfe, S. Evolutionary Theories of Economic and Technological Change: Present Status and Future Prospects; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; ISBN 978-1-351-12769-1. [Google Scholar]

- Peneder, M. Competitiveness and Industrial Policy: From Rationalities of Failure towards the Ability to Evolve. Camb. J. Econ. 2017, 41, 829–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundvall, B.-Å. National Innovation Systems: Towards a Theory of Innovation and Interactive Learning; Pinter Publishers: London, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, C. The “national System of Innovation” in Historical Perspective. Camb. J. Econ. 1995, 19, 5–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esser, K.; Hillebrand, W.; Messner, D.; Meyer-Stamer, J. Systemic Competitiveness: New Governance Patterns for Industrial Development; GDI book series; Frank Cass: London, UK, 1996; ISBN 978-0-7146-4251-2. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhardt, K.M.; Martin, J.A. Dynamic Capabilities: What Are They? Strateg. Manag. J. 2000, 21, 1105–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. The Foundations of Enterprise Performance: Dynamic and Ordinary Capabilities in an (Economic) Theory of Firms. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2014, 28, 328–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagerberg, J.; Mowery, D.C.; Nelson, R.R. The Oxford Handbook of Innovation; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2005; ISBN 978-0-19-926455-1. [Google Scholar]

- Chesbrough, H.W. Open Innovation: The New Imperative for Creating and Profiting from Technology; Harvard Business Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2003; ISBN 1-57851-837-7. [Google Scholar]

- Baum, J.A.C.; Singh, J.V. Evolutionary Dynamics of Organizations; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1994; ISBN 978-0-19-535891-9. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, G.R.; Hannan, M.T. The Demography of Corporations and Industries; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2004; ISBN 978-0-691-12015-7. [Google Scholar]

- North, D.C. Institutions, Institutional Change, and Economic Performance; The Political economy of institutions and decisions; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1990; ISBN 978-0-521-39416-1. [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, O.E. The New Institutional Economics: Taking Stock, Looking Ahead. J. Econ. Lit. 2000, 38, 595–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iansiti, M.; Levien, R. The Keystone Advantage: What the New Dynamics of Business Ecosystems Mean for Strategy, Innovation, and Sustainability; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2004; ISBN 978-1-59139-307-8. [Google Scholar]

- Powell, W.W.; Koput, K.W.; Smith-Doerr, L. Interorganizational Collaboration and the Locus of Innovation: Networks of Learning in Biotechnology. Adm. Sci. Q. 1996, 41, 116–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothschild, M.L. Bionomics: Economy as Ecosystem; Holt: New York, NY, USA, 1992; ISBN 978-0-8050-1979-7. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, J. Predators and Prey: A New Ecology of Competition. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1993, 71, 75–86. [Google Scholar]

- Uzzi, B. Social Structure and Competition in Interfirm Networks: The Paradox of Embeddedness. Adm. Sci. Q. 1997, 42, 35–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granovetter, M. Economic Action and Social Structure: The Problem of Embeddedness. Am. J. Sociol. 1985, 91, 481–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luhmann, N. Social Systems; Stanford University Press: Redwood City, CA, USA, 1995; ISBN 978-0-8047-2625-2. [Google Scholar]

- Valentinov, V. The Complexity–Sustainability Trade-Off in Niklas Luhmann’s Social Systems Theory. Syst. Res. Behav. Sci. 2014, 31, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeleny, M. Autopoiesis: A Theory of Living Organizations; Elsevier Science Ltd.: New York, NY, USA, 1980; ISBN 978-0-444-00385-0. [Google Scholar]

- Valentinov, V. From Equilibrium to Autopoiesis: A Luhmannian Reading of Veblenian Evolutionary Economics. Econ. Syst. 2015, 39, 143–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, S.E. Diversity and Complexity; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2010; ISBN 978-1-4008-3514-0. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, J.H.; Page, S.E. Complex Adaptive Systems: An Introduction to Computational Models of Social Life; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2009; ISBN 978-1-4008-3552-2. [Google Scholar]

- Hansmann, H. The Ownership of Enterprise; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2009; ISBN 978-0-674-03830-1. [Google Scholar]

- Coase, R.H. The Nature of the Firm. Economica 1937, 4, 386–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990; ISBN 978-0-521-40599-7. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, G.; Van Alstyne, M.; Choudary, S.P. Platform Revolution: How Networked Markets Are Transforming the Economy and How to Make Them Work for You, Business Book Summary, 1st ed.; W.W. NORTON & Company: New York, NY, USA, 2016; ISBN 978-0-393-24913-2. [Google Scholar]

- Zott, C.; Amit, R.; Massa, L. The Business Model: Recent Developments and Future Research. J. Manag. 2011, 37, 1019–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velu, C. A Systems Perspective on Business Model Evolution: The Case of an Agricultural Information Service Provider in India. Long Range Plan. 2017, 50, 603–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Defourny, J.; Nyssens, M. Fundamentals for an International Typology of Social Enterprise Models. Volunt. Int. J. Volunt. Nonprofit Organ. 2017, 28, 2469–2497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cyert, R.M.; March, J.G. A Behavioral Theory of the Firm; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Simon, H.A. A Behavioral Model of Rational Choice. Q. J. Econ. 1955, 69, 99–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, H.A. Administrative Behavior; Macmillan Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 1947. [Google Scholar]

- Powell, T.C.; Lovallo, D.; Fox, C.R. Behavioral Strategy. Strateg. Manag. J. 2011, 32, 1369–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levitt, B.; March, J.G. Organizational Learning. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 1988, 14, 319–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D. Thinking, Fast and Slow, 1st ed.; Farrar, Straus and Giroux: New York, NY, USA, 2011; ISBN 978-0-374-27563-1. [Google Scholar]

- Shefrin, H. Beyond Greed and Fear: Understanding Behavioral Finance and the Psychology of Investing; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2002; ISBN 978-0-19-516121-2. [Google Scholar]

- AACSB. 2020 Guiding Principles and Standards for Business Accreditation; Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business: Tampa, FL, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn, T.S. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, 2nd ed.; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1970; ISBN 0-266-45803-2. [Google Scholar]

- Kirman, A. The Economic Crisis Is a Crisis for Economic Theory. CESifo Econ. Stud. 2010, 56, 498–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).