Abstract

To advance breakthroughs in core technologies and foster the growth of technology-based enterprises, China has introduced the Sci-Tech Finance Pilot Policy with the aim of promoting sci-tech enterprise development through optimized financial resource allocation. Based on a sample of technology-based firms listed on China’s SME Board and ChiNext Board from 2009 to 2023, this study empirically examines the relationships between the Sci-Tech Finance Pilot Policy, scale expansion, and technological innovation using a multi-period Difference-in-Differences (DID) model. The key findings reveal that, first, the Sci-Tech Finance Pilot Policy simultaneously promotes corporate scale expansion and technological innovation, generating both scale and innovation effects; second, it generates scale and innovation effects by optimizing financial resource allocation, while scale expansion further induces additional innovation effects. Third, heterogeneity analysis reveals that the innovation effect of the Sci-Tech Finance Pilot Policy is stronger, and the scale effect is weaker when the technology-based enterprise is privately owned, possesses a solid R&D foundation, or operates in a favorable external innovation environment. The findings of this study demonstrate that technology finance policy promotes high-quality development through the synergy between scale and innovation, providing policy implications for developing countries in implementing the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals.

1. Introduction

Currently, developing countries worldwide face sustainable development bottlenecks such as diminishing marginal returns from traditional resource- and labor-intensive industries and insufficient technological innovation. The United Nations identifies scientific and technological innovation as a key lever for achieving the Sustainable Development Goals. Evidence shows that the uncertainties inherent in technological innovation increase operational costs for firms [1], making access to financing crucial for the success of technology-based enterprises [2]. However, a fundamental mismatch exists between the return requirements of financial capital and the frequent absence of immediate commercial value outputs from scientific research, which renders traditional financial models inadequate for supporting innovation-driven development. Prevalent challenges among developing economies include an unbalanced structure of financial supply and relatively weak support for critical sectors such as small- and medium-sized private enterprises and high-tech industries [3]. In contrast, developed countries such as the United States and South Korea have implemented financial support policies that have injected sustained momentum into the scaling and technological upgrading of their science and technology industries. Initiatives such as the U.S. Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) program and South Korea’s National Strategic Technology Development Program exemplify targeted financial measures for fostering technology-oriented firms. China, which is currently in a critical period of transition from “factor-driven” to “innovation-driven” growth, represents a typical case among developing countries for examining the interaction between policy intervention and market mechanisms. To guide diverse financial resources—including venture capital, bank credit, multi-level capital markets, and technology insurance—towards supporting corporate innovation, broadening of funding channels for science and technology enterprises, and promoting the effective integration of sci-tech and finance, China proposed the concept of Sci-tech finance [4] and launched its Sci-Tech Finance Pilot Policy in 2011 and 2016, covering 50 regions, including Beijing and Shanghai. By expanding the pathways through which finance supports technological development, this pilot policy aims to optimize the structure of financial resource allocation, thereby accelerating the commercialization of scientific and technological achievements [5]. Their establishment has facilitated the transition from initial construction to gradual refinement of China’s sci-tech finance system, offering valuable policy insights for resolving the mismatch between “traditional finance and technological innovation” common in developing countries.

The existing research on sci-tech finance and innovation primarily focuses on its impact on firm-level technological innovation [6,7] and regional green technology innovation [8,9]. The research demonstrates that sci-tech finance promotes enterprise technological innovation by increasing R&D investment and reducing the uncertainties associated with R&D activities. Moreover, the research shows that sci-tech finance facilitates technological advancement by providing differentiated financial services tailored to various stages of a firm’s life cycle [10]. In addition, sci-tech finance encourages green technology innovation by enhancing the quality of corporate environmental information disclosure [11], thereby improving firms’ ESG performance [12] and preliminarily validating the sustainable development effect of sci-tech finance. However, due to the externalities inherent in innovation activities, firms that secure financing may tend to prioritize expansion behaviors—such as scaling up production lines, hiring additional employees, and pursuing mergers and acquisitions—over technological innovation activities to achieve rapid financial returns and realize scale expansion [13]. Furthermore, by facilitating the integration of digital platforms into business development, financial policies lay the groundwork for enhancing both innovation capabilities and firm scale [14,15]. Consequently, beyond influencing corporate innovation, the Sci-Tech Finance Pilot Policy may also promote enterprise scale expansion.

Accelerating the scale expansion of technology enterprises and achieving breakthroughs in key core technologies are particularly critical for facilitating industrial structure transformation and sustainable development [16,17], where scale expansion lays the foundational premise for sustainable development, and technological innovation provides the continuous driving force [18]. Sci-Tech Finance Pilot Policy support can offer comprehensive assistance based on the enterprise life cycle, helping firms to evolve from small-scale entities to large-scale enterprises, thereby realizing scale expansion [19]. The economies of scale effect can further reduce enterprise innovation costs and accelerate the output of technological innovations, thereby promoting sustainable enterprise development. However, the funding requirements for enterprises to undertake scale expansion may incentivize them to seek financial support through low-end technologies, leading to sham innovations or crowding out originally planned technological innovation initiatives, which results in resource waste [20,21], further distorts markets, and undermines fair competition among firms [22]. Consequently, in response to the demands of sustainable development, the development of the technology industry requires a systematic approach that simultaneously balances scale expansion and technological innovation. However, existing relevant studies have not taken into account the potential innovation crowding-out effect of scale expansion. If the scale expansion effect induced by the Sci-Tech Finance Pilot Policy leads to the crowding-out of technological innovation, it would not only contradict the policy’s original intent but also potentially cause overcapacity. How to promote the scale expansion of technology enterprises while simultaneously driving their technological innovation and guiding resources from low-efficiency to high-efficiency firms is an urgent issue requiring attention in the development of China’s sci-tech finance policies, and it constitutes the starting point of this research.

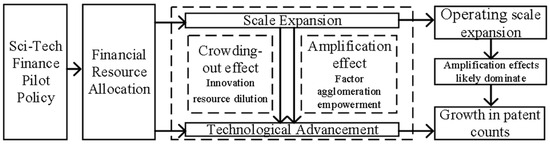

Based on the above analysis, this study integrates the Sci-Tech Finance Pilot Policy, firm scale expansion, and technological innovation into a unified “sustainable development” research framework. Utilizing a sample of technology firms listed on China’s SME Board and ChiNext Board from 2009 to 2023, this study employs a multi-period Difference-in-Differences (DID) model. The DID model is employed to reveal how the Sci-Tech Finance Pilot Policy influences scale expansion and technological innovation in corporate development, as well as their synergistic effects, and further investigates the response differences arising from firm heterogeneity to policy heterogeneity. Compared with existing research, this study seeks to extend the literature in the following aspects: First, in terms of research design, this study theoretically deduces the differential mechanisms of the Sci-Tech Finance Pilot Policy for the first time. While prior studies often examine the isolated effects of the Sci-Tech Finance Pilot Policy, neglecting the dynamic interconnections among intrinsic systemic elements under policy influence, this study decomposes the impact of sci-tech finance on corporate innovation effects. It not only theoretically derives the scale and innovation effects of sci-tech finance but also demonstrates that the scale effect can further catalyze the innovation effect, thereby revealing the interactive relationship between scale expansion and technological innovation in technology-based firms. Second, grounded in the characteristics of structural imbalances in financial resource allocation, this study refines the logical chain of “policy–financial resource allocation–scale effect and innovation effect”. By incorporating policy effect heterogeneity and firm heterogeneity, this study explores how to balance scale expansion and technological innovation, providing a micro-level explanation from a systemic perspective for organizational behavioral decisions with the aim of achieving internal and external dynamic balance and sustainable development within the context of the Sci-Tech Finance Pilot Policy. Third, in terms of research significance, this study analyzes the effects of the Sci-Tech Finance Pilot Policy from both qualitative and quantitative perspectives and verifies the interaction between scale expansion and technological progress under financial resource allocation. This provides a theoretical reference for re-examining the adaptive boundaries of sci-tech finance, optimizing sci-tech finance policies, and promoting the transition of technology firms from low-quality expansion to high-quality development.

The remainder of this study is structured as follows: Section 2 develops the theoretical analysis and research hypotheses; Section 3 outlines the research design; Section 4 and Section 5 present and analyze the empirical results; Section 6 summarizes the research conclusions; and Section 7 concludes by presenting policy implications and summarizing this study’s limitations and future research directions.

2. Theoretical Analysis and Research Hypothesis

2.1. Direct Effect

2.1.1. The Innovation Effect of the Sci-Tech Finance Pilot Policy

The essential mechanism through which the Sci-Tech Finance Pilot Policy exerts its innovation effect is to break information asymmetry and alleviate financing constraints, thereby promoting enterprise technological innovation through the financial support effect, incentive and restraint mechanism, and risk management mechanism.

The Sci-Tech Finance Pilot Policy alleviates enterprise credit constraints through its financial support effect, which further promotes technical innovation in enterprises. First, the Sci-Tech Finance Pilot cities reform the investment model of fiscal science and technology funds to incentivize financial institutions, venture capital, and other capital forces to provide diversified financing channels and financial support for technology-based enterprises throughout their full life cycle. This reform process reduces enterprise financing costs and thus promotes the sustained development of technological innovation activities [23]. Second, according to signaling theory, the Sci-tech finance policy guides financial institutions to improve the quality of enterprises’ information disclosure [24], alleviates the degree of information asymmetry between enterprises’ internal and external stakeholders, increases enterprises’ trade credit, reduces enterprises’ external financing costs, enhances enterprises’ financing capacity in the capital market [25], and provides financial support for enterprises to carry out technological innovation.

Sci-tech finance guides resources to focus on technological innovation through incentive-compatible mechanisms. From the capital supply perspective, introducing external financial entities and instruments, such as equity incentives, enables more investors to participate in corporate decision-making, thereby imposing constraints and supervision on business operations. Through look-through regulation of fund allocation, sci-tech finance steers enterprises toward conducting original and disruptive innovation. During the dynamic assessment process, banks adjust credit lines based on the firm’s R&D activities, prioritizing financing for technology enterprises that have achieved breakthroughs in key core technologies, which enhances capital utilization efficiency and promotes the re-optimization of resource allocation for production factors [26]. From the perspective of corporate demand, the need to fulfill commitments to investors pressures firms to concentrate on improving R&D efficiency and accelerating the translation of basic research into technological outcomes.

Sci-tech finance enhances the stability of the innovation system through risk management mechanisms, ensuring coordinated operation among innovation entities and promoting enterprise technological innovation. On the one hand, the long-cycle and high-risk characteristics of innovation require investors to possess strong capabilities in risk assessment and management. Compared with traditional finance, the Sci-Tech Finance Pilot Policy mitigates investment risks for single capital sources through multi-entity financing involving both government and market participants and smooths out liquidity risks across various stages of enterprise innovation. On the other hand, the pilot cities encourage financial institutions to enhance their capabilities in corporate risk assessment and intangible asset pricing, providing support for intellectual property strategies and asset valuation of technology-based firms [27], which facilitates optimized management and utilization of intellectual property [28,29] and thereby drives technological innovation. Thus, Hypothesis 1 is proposed as follows:

H1.

The Sci-Tech Finance Pilot Policy can significantly improve the technological innovation level of technology enterprises and exert its innovation effect.

2.1.2. The Scale Effect of the Sci-Tech Finance Pilot Policy

Beyond synergizing with the integration of digital platforms into enterprise development to support enterprises in achieving business expansion [14,15], the Sci-Tech Finance Pilot Policy enables technology-based firms to obtain low-cost funding by alleviating information asymmetry between them and financial institutions. Considering their inherent resource endowments and development needs, enterprises may allocate the acquired funds not only to R&D innovation but also to scale expansion, specifically manifested in the expansion of asset scale, production scale, market scale, and organizational scale. First, when R&D subsidies cover part of the production costs, firms may allocate funds to expanding production lines and fixed asset investments, thereby achieving the expansion of assets and production scale [13]. Second, after obtaining financial support, enterprises gain the capacity to engage in mergers and acquisitions, such as issuing additional shares to acquire upstream and downstream firms or establishing overseas branches to increase market share, thereby facilitating market scale expansion. Third, the funding support provided by the Sci-Tech Finance Pilot Policy offsets labor hiring costs, alleviates financing constraints, and allows firms to have more capacity to hire and cultivate highly skilled employees. Furthermore, the pilot regions implement talent programs and provide support in education and healthcare to attract innovative talent, enhancing the agglomeration of human capital. Firms located within these pilot regions can thus absorb more suitable innovative personnel at lower costs, reduce employee search costs, achieve effective firm–employee matching, and ultimately realize organizational scale expansion. Hence, Hypothesis 2 is proposed as follows:

H2.

The Sci-Tech Finance Pilot Policy can significantly increase the operating income of technology enterprises, promote enterprise scale expansion, and exert its scale effect.

2.2. Mechanism Analysis

2.2.1. The Effect of Financial Resource Allocation

The core logic of financial resource allocation theory is to direct capital toward high-productivity entities [30], which also constitutes the central mechanism of the Sci-Tech Finance Pilot Policy. Due to the presence of financial frictions, technology-based firms face tighter financing constraints compared with non-technology-based firms [31], and the accessibility of financial capital directly impacts their innovation activities. On the one hand, the stringent risk management mechanisms and return requirements of financial institutions make it easier for firms with substantial fixed asset collateral to obtain financial resources. However, such firms often exhibit lower levels of innovation and face relatively weaker financing constraints, leading to misallocation of financial resources [32]. Furthermore, scale discrimination and ownership discrimination in financial markets result in greater financing limitations for small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and private firms [33]. On the other hand, information asymmetry can be mitigated by government guarantees for technology-based firms, which help reduce credit market barriers and correct resource allocation biases [34,35,36]. China’s Sci-Tech Finance Pilot Policy aims to utilize a suite of financial instruments to redistribute financial resources among firms, addressing market failures through government guidance and market-based allocation [37], thereby effectively alleviating financing constraints for high-productivity enterprises and achieving optimal allocation of financial resources [38,39]. Thus, Hypothesis 3 is proposed as follows:

H3.

The Sci-Tech Finance Pilot Policy can optimize the allocation of financial resources of technology enterprises, alleviate the financing constraints of technology enterprises, and thereby exert its scale and innovation effects.

2.2.2. The Output Effect of Scale Expansion on Technological Innovation

Scale is not only a factor directly influencing the performance of technology-based enterprises but also a critical determinant of innovation [40], which is particularly crucial for corporate R&D investment and technology adoption. However, scale expansion may have differential impacts on corporate innovation. First, large-scale enterprises are better positioned to meet the input requirements of innovation projects with high capital intensity, reducing the conversion costs from frontier innovation to commercial application, enabling rapid commercialization of existing technological achievements, and thereby further fueling corporate innovation. Second, by engaging in expansion activities such as mergers and acquisitions, enterprises can help promote technological innovation through technological expansion [41] and mitigate the adverse effects of intellectual property pledge on corporate innovation [42]. Furthermore, increasing employment and improving labor structure provide a human capital foundation for enhancing innovation efficiency [43]. However, due to the “resource competition” inherent in the simultaneous pursuit of scale expansion and technological innovation, when a firm’s technology is not yet mature, investments in channel establishment, fixed asset expansion, and personnel hiring may crowd out R&D resources, leading to ineffective scale expansion that undermines sustainable corporate development. Therefore, while the scale effect induced by the Sci-Tech Finance Pilot Policy may further promote technological innovation, it could also potentially crowd out the innovation effect. Synthesizing the above discussions, Hypothesis 4 is proposed as follows:

H4.

The scale expansion effect of the Sci-Tech Finance Pilot Policy on technology enterprises can further significantly improve the technological innovation level of technology enterprises and amplify the innovation effect.

2.3. Heterogeneity Analysis

Given the heterogeneity in both internal and external innovation environments across firms, there exist differences in how enterprises structure their financial resource allocation [44]. Consequently, the impact of the Sci-Tech Finance Pilot Policy on the scale and innovation effects may vary among different technology-based enterprises. This section elaborates on the differential transmission mechanisms of sci-tech finance between technological innovation and scale expansion, based on the core mechanism of financial resource allocation underpinning the policy, from three perspectives: the nature of enterprise ownership, the foundation of enterprise R&D, and the external innovation environment.

2.3.1. The Ownership Structure of the Enterprise

“Ownership discrimination” in the allocation of financial resources causes greater productivity losses than “size discrimination [45]”. Compared with private enterprises, state-owned enterprises (SOEs) are more likely to obtain low-cost funds due to implicit government guarantees. In addition, SOEs mainly undertake the function of policy transmission, and their allocation of financial resources needs to align with the demands of regional economic growth and employment stability; therefore, they tend to maintain competitiveness through capacity expansion. However, private enterprises face tighter financing constraints in technological innovation compared with SOEs and are at a disadvantage in terms of funding acquisition capacity. As a result, they are more inclined to respond to competition by improving their level of technological innovation, and they are more likely to optimize the allocation of financial resources and increase R&D intensity through the Sci-Tech Finance Pilot Policy. Therefore, compared with SOEs, the Sci-Tech Finance Pilot Policy results in less motivation for capacity expansion and greater motivation for technological innovation among private enterprises. Therefore, Hypothesis 5a is derived as follows:

H5a.

Compared with state-owned enterprises, the Sci-Tech Finance Pilot Policy has a stronger innovation effect and a weaker scale effect on private enterprises.

2.3.2. Enterprise R&D Foundation

The R&D capability of technology-based enterprises serves as the foundation for their further technological innovation, where executives with an R&D background (TechTMT = 1) are more inclined to adopt innovation-driven growth paths, readily identify technological innovation opportunities, and more efficiently channel sci-tech finance funds into R&D expenditures, whereas executives without such a background may prioritize short-term returns and tend to allocate resources toward scale expansion. Consequently, compared with technology firms with a weaker R&D foundation, those possessing a stronger R&D foundation exhibit reduced motivation for scale expansion and greater motivation for technological innovation. Thus, Hypothesis 5b is proposed as follows:

H5b.

Compared with enterprises with a poor R&D foundation, the Sci-Tech Finance Pilot Policy has a stronger innovation effect and a weaker scale effect on enterprises with a sound R&D foundation.

2.3.3. The External Innovation Environment of Enterprises

Besides the influence of an enterprise’s R&D foundation, the strategic choice between technological innovation and capacity expansion also depends on an enterprise’s external innovation environment. A sound innovation ecosystem and intellectual property protection system can work in conjunction with the Sci-Tech Finance Pilot Policy to reduce enterprises’ R&D costs, accelerate technology commercialization [46], and lead enterprises to be more inclined to engage in technological innovation. In regions with a poor external innovation environment, intellectual property protection is weak and innovation resources are scarce; enterprises will thus shift to lower-risk investment strategies and further carry out capacity expansion activities. Therefore, compared with technology enterprises in regions with a poor external innovation environment, those in regions with a favorable external innovation environment have less motivation for capacity expansion and greater motivation for technological innovation. Thus, Hypothesis 5c is derived as follows:

H5c.

Compared with enterprises in a poor external innovation environment, the Sci-Tech Finance Pilot Policy has a stronger innovation effect and a weaker scale effect on enterprises in a favorable external innovation environment.

The theoretical model of this study is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Theoretical model diagram.

3. Study Design

3.1. Model Specification

Since the Sci-Tech Finance Pilot Policy was launched in phases in 2011 and 2016, to examine the impact of the Sci-Tech Finance Pilot Policy on enterprises’ scale expansion and technological innovation, this study employs a multi-period DID mode [47]. This model extends the requirement of the traditional DID model that policy shocks occur at the exact same time, addresses the scenario where individuals in the treatment group receive the treatment at different times, and accounts for time-varying dynamics.

In Equation (1), y denotes the dependent variable, proxying for enterprise operating scale (Rev) and technological innovation (Tech-Inno); i indexes firms; and t denotes years. The variable did represents the core explanatory variable, with its coefficient capturing the net effect of the Sci-Tech Finance Pilot Policy, which is the primary focus of this study. Control signifies control variables; and denote firm and year fixed effects; and denotes the stochastic error term.

3.2. Variable Selection

3.2.1. Dependent Variables: Operating Scale (Rev), Technological Innovation (Tech-Inno)

Enterprise operating scale is measured by operating revenue (Rev) [48], while technological innovation is proxied by the number of invention patent applications (tech) for technology-based firms [49,50].

3.2.2. Explanatory Variable: The Sci-Tech Finance Pilot Policy (did)

The Sci-Tech Finance Pilot Policy [51] is captured by . Here, treat is a binary variable indicating whether a firm is located in a pilot city (1 if yes, 0 otherwise). time is a post-policy dummy (0 pre-implementation, 1 post-implementation, including the implementation year). did equals 1 if a firm is in a pilot city after (or during) the policy implementation year, and 0 otherwise.

3.2.3. Mediating Variables: Financing Scale (FS) and Financing Constraints (WW)

The financing scale and financing constraints are selected to measure the efficiency of financial resource allocation. Specifically, a firm’s financing scale [52] is measured using the ratio of its current liabilities to total assets in the current year, and financing constraints [53] are measured using the WW index.

3.2.4. Control Variable

Based on the existing relevant literature [32,54], this study selects a series of firm-level control variables that may affect firms’ scale expansion and technological innovation, which are specified as follows:

(1) Firm age (Age): Mature firms have stable operations and extensive customer resources, making it easier for them to achieve scale growth through capacity expansion; however, mature firms tend to form “path dependence,” have low enthusiasm for high-risk and long-cycle R&D investments, and exhibit “innovation inertia”.

(2) Ownership concentration (Top): High ownership concentration can reduce disagreements among shareholders, enable rapid decision-making, and improve the efficiency of scale expansion; however, if major shareholders tend to avoid investment risks, it may also inhibit expansion. Additionally, when ownership is excessively concentrated, major shareholders mostly focus on short-term returns and have low acceptance of high-risk R&D investments, which easily reduces R&D inputs and hinders technological innovation.

(3) CEO duality (Dual): The integration of the chairman and general manager positions can simplify the decision-making process and quickly advance scale expansion plans, such as capacity expansion and market development; however, it may easily lead to “arbitrary decision-making,” tend to choose low-risk and short-cycle businesses, and hinder technological innovation.

(4) Leverage ratio (Lev): Moderate debt can supplement firms’ operating funds, helping firms quickly implement scale expansion plans such as capacity expansion and support technological innovation; however, high debt leads to heavy interest burdens, which instead restrict investment and squeeze R&D inputs.

(5) Board size (BSize): A large board size means strong multi-resource integration capabilities, which can provide channel, financing, and policy information support required for capacity expansion to facilitate scale growth. A large board is also more likely to include “members with technical backgrounds,” which can provide professional guidance for R&D strategies, reduce innovation misjudgments caused by single decision-making, and promote technological innovation.

(6) Return on equity (Roe): Firms with high ROE have abundant internal funds, which they can directly use to support scale expansion and conduct R&D activities.

(7) State ownership (Soe): State-owned enterprises usually have policy support and risk resistance capabilities—making it easier for them to achieve scale growth through large-scale investments—while having weak innovation motivation, while non-state-owned enterprises show the opposite trend.

The specific variable definitions are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Definition of main variables.

3.3. Data Sources

Since the key target of the Sci-Tech Finance Pilot Policy is technology-based small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), the SME Board and ChiNext Board possess both the characteristics of “strong technological attributes” and “urgent financing needs”. They are not only the main targets of the pilot policy but also important carriers for exploring scale expansion and technological innovation, forming a sharp contrast with large-scale enterprises on the Main Board. In addition, to exclude the interference of financial crises and considering that the ChiNext Board was launched in 2009, this study takes technology-based listed enterprises on the SME Board and ChiNext Board among Chinese listed enterprises from 2009 to 2023 as the research sample. With reference to the definition standards for technology-based enterprises, this study excludes non-technological enterprises with insufficient R&D investment ratios, including those in industries such as agriculture, forestry, animal husbandry, fishery, wholesale, retail, warehousing, news publishing, film and television production, cultural arts, and finance, along with enterprises under special treatment or with consecutive data gaps. To address the policy’s geographic heterogeneity—covering cities, economic zones, and specific districts–firms within Beijing’s Zhongguancun, Changsha High-Tech Zone, and Chengdu High-Tech Zone were precisely identified using corporate registration data (rather than city-level aggregation) [55], minimizing selection bias. The final dataset contains 8663 firm–year observations. From the perspective of industry distribution, the electronic information industry accounts for 30.89%, the high-end equipment manufacturing industry accounts for 39.38%, the biopharmaceutical industry accounts for 10.59%, and other technology-related industries account for 19.14%. This industry distribution is fully aligned with the objective of the Sci-tech finance pilot to support breakthroughs in key core technologies. The data are sourced from the China Stock Market & Accounting Research Database (CSMAR) and annual reports of enterprises. CSMAR is a scholarly database specializing in China’s financial and economic markets and is widely recognized as the standard data source for empirical research on Chinese markets.

4. Empirical Results and Analysis

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

The descriptive statistics in Table 2 indicate that the mean value of the natural logarithm of operating revenue (Rev) is 20.989 with a standard deviation of 1.144. The average number of invention patent applications (Tech-Inno) is 2.426 with a standard deviation of 1.416, suggesting substantial heterogeneity in both operating scale and innovation levels across sample firms. The mean of did is 0.4931, indicating that the Sci-Tech Finance Pilot Policy affects 49% of the sample enterprises.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics.

4.2. Correlation Analysis

Table 3 presents the results of the correlation analysis of the main variables. From the perspective of the correlation between core variables, the Sci-Tech Finance Pilot Policy (did) exhibits a positive correlation with enterprise output scale (Rev) and technological innovation level (Tech-Inn) at the 1% significance level, respectively. This preliminarily confirms the logic in the theoretical analysis that “the Sci-tech finance pilot policy may simultaneously promote enterprise scale expansion and technological innovation”. Furthermore, the correlations of mediating variables and control variables are also consistent with the theoretical analysis, providing a fundamental basis for subsequent regression analyses.

Table 3.

Correlation analysis of variables.

4.3. Scale and Innovation Effects of the Sci-Tech Finance Pilot Policy

Based on Model (1), Columns (1)–(2) in Table 4 present regression results examining the Sci-Tech Finance Pilot Policy’s impact on enterprise scale expansion. The coefficient of the policy interaction term did remains statistically significant at the 1% level both with and without control variables. The results indicate that the operating revenue of enterprises in the treatment group increased significantly by 9.7% following the implementation of the Sci-Tech Finance Pilot Policy compared with the control enterprises. Thus, the Sci-Tech Finance Pilot Policy significantly promotes scale expansion in technology-based enterprises, activating scale effects. The regression results of the control variables are also consistent with the previous analysis, and H2 is verified.

Table 4.

Baseline regression results.

Theoretical analysis suggests that while the Sci-Tech Finance Pilot Policy may activate innovation effects, scale effects could potentially crowd them out. Based on Model (1), Columns (3)–(4) of Table 4 present regression results for technological innovation. The coefficient of the policy interaction term did on invention patent applications is significantly positive at the 1% level, both with and without control variables. This indicates that treatment firms experienced a 15.7% increase in invention patent applications relative to control firm’s post-implementation. Thus, the policy promotes technological progress and activates innovation effects, demonstrating that scale effects do not crowd out innovation effects. Collectively, the Sci-Tech Finance Pilot Policy concurrently facilitates both enterprise-scale expansion and technological innovation, which breaks through the cognitive framework of existing studies that only focus on the single policy effect of the sci-tech finance’s innovation effect [6] and refutes the logical inference that the scale effect of the Sci-Tech Finance Pilot Policy crowds out the innovation effect. The regression results of the control variables are also consistent with the previous analysis, and H1 is verified.

4.4. Parallel Trends Test

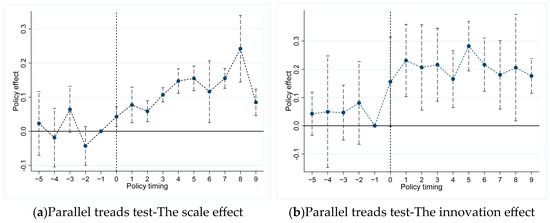

The application of the DID method requires that the treatment and control groups satisfy the parallel trends assumption prior to policy implementation. Specifically, there should be no significant differences in operating scale or technological innovation capability between listed firms in pilot and non-pilot regions before the introduction of the Sci-Tech Finance Pilot Policy. To validate this assumption, we conducted parallel trends tests as illustrated in Figure 2. The results demonstrate no statistically significant pre-existing differences in either operating scale (a) or technological innovation capability (b) between listed firms in pilot versus non-pilot regions during the pre-treatment period. Following policy implementation, firms in pilot regions exhibited significantly higher levels of both operating scale and technological innovation compared with their non-pilot counterparts, thereby confirming the satisfaction of the parallel trends assumption.

Figure 2.

Parallel trends test.

4.5. Robustness Tests

Endogeneity concerns arising from reverse causality are unlikely in this setting, as changes in firm-level characteristics do not trigger the implementation of the Sci-Tech Finance Pilot Policy. To further mitigate potential endogeneity from omitted variables and measurement errors, robustness tests were conducted.

4.5.1. Heterogeneous Multi-Period DID Estimation

The key to multi-period DID estimation lies in the weighted average of multiple distinct treatment effects. Due to the constant changes in the treatment and control groups at different time points, a negative weighting issue may arise. This issue causes the average treatment effect obtained by weighting and averaging different treatment effects to be opposite in direction to the true average treatment effect, leading to biased estimation. Therefore, this study conducts a robustness check using the multi-period doubly robust estimator proposed by Callaway and Sant’Anna (2021) [56], known as the Callaway and Sant’Anna Difference-in-Differences (CSDID) method. The core of this method is to divide the sample into different subgroups, estimate the treatment effect for each subgroup separately, and then aggregate the treatment effects of different subgroups through a specific strategy based on the principle of reducing the aggregated weights of subgroups that may have biases. This effectively avoids the estimation bias problem in multi-period DID. Callaway and Sant’Anna argue that by selecting different weights, four distinct types of Average Treatment Effects (ATTs) can be calculated: the Simple Weighted Average Treatment Effect (Simple ATT), which is the simple weighted sum with equal weights; the Dynamic Average Treatment Effect (Dynamic ATT), which is the weighted sum of effects grouped by the time elapsed since the first treatment; the Calendar Time Average Treatment Effect (Calendar Time ATT), which is the weighted sum of effects grouped by calendar years; and the Group Average Treatment Effect (Group ATT), which is the weighted sum of effects grouped by the time of the first treatment. Regression results are presented in Table 5. It can be observed that all four types of ATTs indicate that the Sci-Tech Finance Pilot Policy can significantly promote the scale expansion of technology enterprises and significantly improve their level of technological innovation, consistent with the baseline regression results, confirming the robustness of this study’s conclusions.

Table 5.

Heterogeneous multi-period DID estimation.

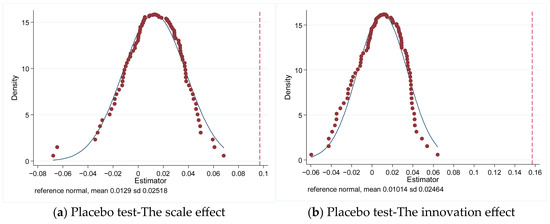

4.5.2. Placebo Test

In this study, dummy variables were constructed by randomly selecting samples of the treatment group and the time of policy implementation. The constructed policy dummy variables were substituted into Model (1) to replace did for regression. The above process was repeated 500 times, and the distribution diagram of the regression coefficients of did is shown in Figure 3. It can be observed that the falsely estimated coefficients are symmetrically distributed around zero, indicating that the artificial policy variables have no statistically significant effects on either scale expansion (a) or technological innovation (b). These results further rule out potential confounding from unobserved factors and confirm the robustness of our findings regarding the significant impacts of the Sci-Tech Finance Pilot Policy on both scale expansion and technological innovation.

Figure 3.

Placebo test.

To mitigate potential biases arising from temporal variations between treatment and control groups, this study conducted placebo tests by artificially advancing the implementation timing of the pilot policy by 2, 3, and 4 years to construct counterfactual policy periods. As shown in Table 6, the estimated coefficients for did_2, did_3, and did_4 are all statistically insignificant, effectively ruling out pre-existing differences in operating scale and technological innovation capability between the groups that might be attributable to time trends.

Table 6.

Placebo test.

4.5.3. Exclude Other Policy Interference

By reviewing policy documents of relevant city pilots, it is observed that the implementation of the National Innovative City Pilot policy, the construction of National Independent Innovation Demonstration Zones, the “Made in China 2025” plan, and the Green Finance Pilot policy may affect firms’ output scale and technological innovation level within the sample period of this study. To rule out these potential confounding factors, this study incorporates dummy variables for these four policies into the baseline Model (1) to control for their possible impacts on firms’ output scale and technological innovation level. ICP is a dummy variable indicating whether the city where the firm is located was included in the Innovative City Pilot program in the current year, taking a value of 1 if included and 0 otherwise. Similarly, MIC2025 indicates whether the firm’s industry belonged to one of the ten key sectors in the current year and the time period is 2015 and onwards, taking a value of 1 if it did and 0 otherwise. GFP indicates whether the city where the firm is located was included in the Green Finance Pilot program in the current year, taking a value of 1 if included and 0 otherwise. NIDZ indicates whether the city where the firm is located has established a National Independent Innovation Demonstration Zone in the current year, taking a value of 1 if it has and 0 otherwise. Columns (1) and (2) in Table 7 present the corresponding regression results, which show that after accounting for the influence of these four potential interfering policies, the scale and innovation effects of the Sci-Tech Finance Pilot Policy remain statistically significant. This confirms the robustness of the conclusions.

Table 7.

Robustness tests.

4.5.4. The Explanatory Variable Lags One Period

To account for time-lagged effects of the Sci-Tech Finance Pilot Policy, the policy variable is lagged by one period in re-estimated regressions. As shown in Columns (3)–(4) of Table 7, the results remain consistent with baseline findings, confirming the robustness of our conclusions.

5. Further Research

5.1. Mechanism Tests

Theoretical analysis suggests that the exertion of the scale and innovation effects of the Sci-Tech Finance Pilot Policy is achieved by increasing the financing scale of technology-based enterprises to alleviate financing constraints and optimize the allocation of financial resources, this study further verifies this transmission.

5.1.1. Financial Resource Allocation

The Sci-Tech Finance Pilot Policy optimizes financial resource allocation by incentivizing financial institutions to increase support for technology-based enterprises while reducing capital access for firms with low technological attributes. As theoretically posited, the establishment of the Sci-Tech Finance Pilot Policy is conducive to reducing the financing costs of technology-based enterprises, alleviating their financing constraints, and promoting technological development. Therefore, whether the Sci-Tech Finance Pilot Policy improves the efficiency of financial resource allocation requires examination. Here, the financing scale (FS) and financing constraints (WW) indicators are used to replace the dependent variable in the baseline regression Model (1), respectively, for re-conducting the regression, so as to examine the impact of the Sci-Tech Finance Pilot Policy on the efficiency of financial resource allocation. The results are presented in Table 8. It can be observed that when regressing on the financing scale (FS), the regression coefficient of did is significantly positive at the 1% significance level. This result indicates that compared with non-pilot areas, the financing scale of technology-based enterprises in Sci-Tech Finance Pilot Policy areas increased significantly after the implementation of the pilot, meaning the implementation of the Sci-Tech Finance Pilot Policy reduces the financing difficulty of technology-based enterprises. Second, when regressing on corporate financing constraints (WW), the regression coefficient of did is significantly negative at the 1% significance level; this shows that compared with non-pilot areas, the financing constraints of technology-based enterprises in Sci-Tech Finance Pilot Policy areas were significantly alleviated after the implementation of the pilot policy, indicating that the Sci-Tech Finance Pilot Policy reduces enterprises’ financing difficulty and realizes the reallocation of financial resources. This finding is consistent with the core logic of existing financial policies and corporate innovation [32] and extends the conclusion that distortions in financial resource allocation affect enterprises’ large-scale production [21], emphasizing that improving the misallocation of financial resources is the root cause of the exertion of policy effects. Thus, H3 is verified.

Table 8.

Mechanism analysis: financial resource allocation.

5.1.2. The Effect of Scale Expansion on Technological Innovation

Previous analysis shows that the Sci-Tech Finance Pilot Policy effectively alleviates the financing constraint problem of technology-based enterprises, further promoting enterprises’ technological innovation and scale expansion, and scale expansion does not exert a crowding-out effect on technological innovation. Combined with theoretical analysis, it can be concluded that scale expansion may play a positive role in the process by which the Sci-tech Finance Pilot Policy affects the technological innovation of technology-based enterprises. To further verify whether the effect of the Sci-tech Finance Pilot Policy on enterprises’ technological innovation can be further released through the enterprise scale effect, this paper constructs the regression model shown in Equation (2) below and conducts centralization treatment to alleviate multicollinearity.

In Equation (2), y represents technological innovation, proxied by invention patent applications. All other variables remain consistent with Equation (1). Considering the correlation between the Sci-tech Finance Pilot Policy and enterprises’ scale expansion—while no correlation existed between the two before the pilot policy was implemented, and there was no significant difference in enterprise scale between the treatment group and the control group. With reference to previous studies [48], this paper further constructs a predetermined variable (FRev) based on enterprises’ output scale in the year before the policy implementation to replace Rev in Model (2) for regression, so as to better control potential endogeneity in the model. Columns (1)–(2) in Table 9 present the regression results of Equation (2). It can be observed that the estimated coefficients of the interaction term did × Rev and did × FRev are both significantly positive. This result confirms that the scale expansion effect exerted by the Sci-Tech Finance Pilot Policy on technology-based enterprises can reduce innovation costs through economies of scale, and further promote the increase in the number of invention patent applications by integrating innovation resources, thereby facilitating enterprises’ technological innovation and exerting the innovation effect. This study extends the policy logic of “policy–resource allocation–eliminating inefficient enterprises” in developed countries to “policy–resource allocation–supporting efficient enterprises” in developing countries [57], providing a complementary theoretical basis for the setting scenarios of innovation policies. Thus, H4 is verified.

Table 9.

The effect of scale expansion on technological innovation.

5.2. Heterogeneity Tests

5.2.1. The Ownership Structure of the Enterprise

To further corroborate the differential transmission effects of the Sci-Tech Finance Pilot Policy on enterprises’ scale expansion and technological innovation between state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and private enterprises, this study divides the sample into the SOE group and the private enterprise group, according to the nature of enterprise ownership, and conducts regressions based on Model (1). Table 10 presents the regression results for SOEs and private enterprises. The results indicate that the technological innovation effect of the Sci-Tech Finance Pilot Policy is more significant in private enterprises, while its scale expansion effect is more prominent in SOEs. Thus, H5a is verified. It is necessary to precisely match sci-tech finance services according to enterprise nature to alleviate the imbalance between enterprise scale expansion and technological innovation caused by sci-tech finance policies.

Table 10.

Heterogeneity analysis: the ownership structure of the enterprise.

5.2.2. Enterprise R&D Foundation

This study uses the enterprise R&D foundation as the grouping variable to explore the differential transmission effects of the Sci-Tech Finance Pilot Policy. Since the Sci-Tech Finance Pilot Policy affects enterprises’ patent output, using indicators such as patents as grouping variables tends to give rise to endogeneity. The solution to this problem is to use only pre-pilot patents for grouping. However, as the pilot in this study is divided into two phases, it is not feasible to group enterprises based on pre-pilot patent output. Accordingly, this study measures enterprises’ R&D foundation by whether executives have R&D backgrounds, sets a 0–1 variable to group sample enterprises, and conducts regressions based on Model (1). Specifically, TechTMT = 1 if executives have educational or professional experience related to R&D activities; otherwise, enterprises are classified into the group where TechTMT = 0. Based on the regression results in Table 11, it can be observed that enterprises with R&D backgrounds (where TechTMT = 1) exhibit a more pronounced innovation effect, while enterprises without R&D backgrounds (where TechTMT = 0) show a more prominent scale expansion effect. Thus, H5b is verified. This indicates that strengthening enterprises’ R&D foundation and developing executives’ R&D capabilities is conducive to balancing the scale and innovation effects of the Sci-Tech Finance Pilot Policy.

Table 11.

Heterogeneity analysis: enterprise R&D foundation.

5.2.3. The External Innovation Environment of Enterprises

This study uses the external innovation environments of enterprises as the grouping variable to explore the differential transmission effects of the Sci-Tech Finance Pilot Policy and sets a 0–1 variable to group sample enterprises. Since eastern provinces and municipalities such as Beijing, Tianjin, Shanghai, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, and Guangdong have a better comprehensive innovation environment, this study classifies enterprises located in these regions into the group where inn_env = 1, and the rest into the group where inn_env = 0, and then conducts grouped regressions based on Model (1). The results are presented in Table 12; it can be observed that enterprises in regions with a better external innovation environment exhibit a more pronounced innovation effect, while the scale effect is more prominent in regions with a poorer external innovation environment. Thus, H5c is verified. This indicates that optimizing the external innovation environment is conducive to alleviating the resource occupation of technological innovation by scale expansion under the Sci-Tech Finance Pilot Policy, which aligns with the findings of existing studies [58].

Table 12.

Heterogeneity analysis: the external innovation environment of enterprises.

6. Conclusions

Against the backdrop of the evolving global technological competition landscape, developed countries such as the United States and South Korea have injected sustained impetus into the scale expansion and technological upgrading of their technology industries by formulating financial support policies. However, there remains a gap in the exploration of the impact mechanism and boundary conditions of China’s Sci-Tech Finance Pilot Policy on enterprises’ technological innovation and scale expansion. Therefore, faced with the demand for sustainable development, how China’s Sci-Tech Finance Pilot Policy guides the flow of resources from low-efficiency enterprises to high-efficiency ones and promotes enterprises’ scale expansion and technological innovation by optimizing the allocation of financial resources is an issue that urgently requires attention in policy research and development of China’s Sci-Tech Finance Pilot Policy. Additionally, from the perspective of the heterogeneity of policy effects, how enterprise heterogeneity affects the exertion of the scale and innovation effects of the Sci-Tech Finance Pilot Policy still awaits further exploration. Based on the above analysis, this study places the Sci-Tech Finance Pilot Policy, enterprise scale expansion, and technological innovation within a unified research framework of “sustainable development”. Using a sample of technology-based enterprises listed on the SME Board and GEM Board among Chinese listed enterprises from 2009 to 2023, it employs a multi-period DID model to reveal how the Sci-Tech Finance Pilot Policy affects scale expansion and technological innovation, and their coordinated development in the process of enterprise development, and further explores the differential responses of enterprise heterogeneity to policy heterogeneity.

The main findings of this study are as follows: (1) China’s Sci-Tech Finance Pilot Policy can significantly promote the scale expansion of technology-based enterprises and improve their technological innovation level. This indicates that the scale expansion of enterprises after receiving support from the Sci-Tech Finance Pilot Policy does not cause crowding-out of technological innovation. (2) Mechanism research on the Sci-Tech Finance Pilot Policy reveals that the policy promotes enterprises’ scale expansion and technological innovation by guiding the flow of financial resources into technology-based enterprises, alleviating their financing constraints and optimizing the allocation of financial resources. Moreover, the scale effect can indirectly promote corporate technological innovation and generate an innovation effect. This shows that not only does the scale effect generated by the Sci-Tech Finance Pilot Policy not crowd out corporate technological innovation, but it also further feeds back into technological innovation through economies of scale, which confirms the sustainable development effect of the Sci-Tech Finance Pilot Policy on technology-based enterprises. (3) Heterogeneity analysis shows that there is heterogeneity in the scale and innovation effects of the Sci-Tech Finance Pilot Policy. Compared with state-owned enterprises, private enterprises exhibit a more significant innovation effect under the influence of the Sci-Tech Finance Pilot Policy, while SOEs show a more prominent scale expansion effect under the Sci-Tech Finance Pilot Policy. In addition, when enterprises have an R&D foundation and a favorable external innovation environment, the innovation effect of the Sci-Tech Finance Pilot Policy is more obvious. This fully verifies the nature of financial resource allocation of sci-tech finance from the perspective of financial supply side structural reform [3], and further reflects the applicable boundaries of the Sci-Tech Finance Pilot Policy, providing a theoretical basis for guiding enterprises to balance the resource allocation between technological innovation and scale expansion.

7. Implications, Limitations, and Future Research

7.1. Implications

The following recommendations are based on the results of this study: First, persistently promote the reform of the Sci-Tech Finance Pilot Policy; establish a diversified Sci-Tech Finance system, and improve its institutional mechanisms; expand the scope of Sci-Tech Finance Pilot Policy programs based on summarizing development experiences from existing pilot regions while integrating regional financial and technological resources; reinforce the principal role of enterprises in technological innovation; guide various financial institutions to fully engage in innovating sci-tech finance products and services; enhance support for enterprise innovation—particularly disruptive innovation; and improve the efficiency of financial resource allocation.

Second, it is recommended to continue to deepen the financial supply side reform; encourage financial institutions to expand the scope of pledgeable intellectual property rights; promote the in-depth integration of the capital chain and the innovation chain; innovate financial service methods; and broaden enterprises’ financing channels. Moreover, the intrinsic relationship between enterprises’ technological innovation and scale expansion should be coordinated. Financial institutions should supervise and restrict the direction of sci-tech finance funds by establishing relevant indicators to prevent enterprises from occupying financial resources through ineffective expansion. Moreover, large-scale enterprises should take the lead in establishing innovation consortia, leverage their scale advantages to conduct research and development (R&D) of generic technologies, and promote the coordinated development of enterprises’ scale expansion and technological innovation.

Third, it is recommended to implement targeted policies based on enterprises’ internal and external conditions to reduce the heterogeneous biases of sci-tech finance policies. In the process of promoting the Sci-Tech Finance Pilot Policy, the heterogeneity of enterprise endowments and environments should be fully considered, and policy plans should be formulated based on enterprise-specific conditions. State-owned enterprises (SOEs) should be encouraged to make concentrated investments in key areas while leveraging the scale effect to promote enterprises’ technological progress, guide SOEs to carry out key core technological innovation, and unleash the innovation vitality of SOEs. Moreover, enterprises should establish executive teams with R&D experience, enhance labor skills, and optimize the direction of fund allocation. Finally, for enterprises in regions with a poor external innovation environment, while providing more financial support, supplementary innovation measures should also be provided. Furthermore, enterprises should also actively jointly establish R&D centers with universities and research institutions, leverage external resources to improve their innovation capabilities, and further promote the technological innovation of technology-based enterprises.

7.2. Limitations and Future Research

While this study reveals the dual effects of the Sci-Tech Finance Pilot Policy, several limitations warrant further investigation: First, although the theoretical section deduces the mechanism through which policy-induced scale expansion further promotes technological innovation, the specific transmission channels require micro-level empirical verification. Second, although this paper verifies through theoretical deduction and empirical tests that the Sci-tech Finance Pilot Policy can further promote enterprises’ technological innovation through the scale effect, and adopts the pre-policy enterprise scale as a predetermined variable in the empirical tests to mitigate the endogeneity issue, the pre-policy scale, while reflecting the basis for enterprise scale expansion, may fail to accurately capture the dynamic change process of enterprise scale expansion after the policy implementation. Therefore, future research can further test this transmission path using the instrumental variable method. Third, having identified how internal and external environments influence firms’ scale–innovation trade-offs under the policy, subsequent studies may analyze the equilibrium point between these objectives from heterogeneous firm–environment perspectives to better guide corporate strategies. Fourth, spillover effects may arise between Sci-tech finance pilot regions and non-pilot regions, and future studies can further investigate the effects of Sci-tech finance using a spatial DID model.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, formal analysis, methodology, software, investigation, writing—review and editing, Z.L., H.H. and M.X.; validation, resources, H.H. and M.X.; data curation, writing—original draft preparation, visualization, Z.L.; supervision, project administration, funding acquisition, H.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grants 72072144, 71672144); the Soft Science Research Program of Shaanxi Innovation Capability Support Plan (Grants 2024ZC-YBXM-031, 2025WZ-YBXM-18, 2021KRM183); the Key Soft Science Research Projects of Xi’an Science and Technology Bureau (Grants 23RKYJ0001, 21RKYJ0009); and the Sanqin Talent Special Support Program for Leading Talents in Philosophy, Social Sciences, and Culture (Grant 105-253062401).

Data Availability Statement

Data used in this paper can be found in Section 3.3.

Acknowledgments

The authors are deeply grateful to the Editor and anonymous referees for their constructive comments and suggestions, which have significantly enhanced the quality of this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zacca, R.; Alhoqail, S. Entrepreneurial and market orientation interactive effects on SME performance within transitional economies. J. Res. Mark. Entrep. 2021, 23, 268–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heller, D. Financial market integration and the effects of financing constraints on innovation. Res. Policy 2024, 53, 104988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, T. Investigating science and technology finance and its implications on real economy development: A performance evaluation in Chinese provinces. J. Knowl. Econ. 2024, 15, 10442–10469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Chen, C.; Tang, Y. Technology and Finance; Science Press: Beijing, China, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, C. Does Technology and Finance Enhance the Innovation Capacity of High-tech Industries. J. Innov. Dev. 2023, 3, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y. Sci-Tech finance pilot policies, property rights protection and enterprise innovation. Financ. Res. Lett. 2025, 83, 107756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, B.; Chen, L.; Li, H. Impact of SciTech–Finance integration policy implementation on SME innovation performance: Mediating effect of tax burden. Financ. Res. Lett. 2025, 77, 107031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wan, L.; Guo, Q.; Nie, S. The Effects of the Sci-Tech Finance Policy on Urban Green Technology Innovation: Evidence from 283 Cities in China. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, L.; Zhang, X. Spatial Effect of the impact of sci-tech financial ecology on green technology innovation: Empirical analysis based on panel data of five major urban agglomerations along the eastern coast. Econ. Geogr. 2023, 43, 147–154. [Google Scholar]

- Howell, S.T. Financing innovation: Evidence from R&D grants. Am. Econ. Rev. 2017, 107, 1136–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Xin, Z.; Wang, Y. Effect of the sci-tech finance pilot policy on corporate environmental information disclosure—Moderating role of green credit. Financ. Res. Lett. 2024, 62, 105177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, W.; Yu, J.; Zhao, L. Can Sci-Tech Finance Policy Boost Corporate ESG Performance? Evidence from the Pilot Experiment of Promoting the Integration of Technology and Finance in China. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamiu, T.A.; Adeoye, M.A. Impact of Financial Support in Fueling Business Expansion for Small Enterprises. J. Penelit. Pengemb. Sains Hum. 2023, 7, 370–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Mohammad, M. The Role of Digital Platforms in Scaling Social Enterprises: A Study of Business Model Innovation in China. Uniglobal J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2024, 3, 387–392. [Google Scholar]

- Attah, R.U.; Garba, B.M.P.; Gil-Ozoudeh, I.; Iwuanyanwu, O. Corporate banking strategies and financial services innovation: Conceptual analysis for driving corporate growth and market expansion. Int. J. Eng. Res. Dev. 2024, 20, 1339–1349. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, M.; Wang, J.; Yang, S.; Li, Q. The driving effect of technological innovation on green development: From the perspective of efficiency. Energy Policy 2024, 188, 114089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, T. Technological innovation promotes industrial upgrading: An analytical framework. Struct. Change Econ. Dyn. 2024, 70, 150–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N.; Liu, Y.; Žiković, S.; Belyaeva, Z. The effects of technological innovation on sustainable development and environmental degradation: Evidence from China. Technol. Soc. 2023, 72, 102184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, P.; Kumar, S.; Chavan, M.; Lim, W.M. A systematic literature review on SME financing: Trends and future directions. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2023, 61, 1247–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.; Guo, Y.; Le-Nguyen, K.; Barnes, S.J.; Zhang, W. The impact of government subsidies and enterprises’ R&D investment: A panel data study from renewable energy in China. Energy Policy 2016, 89, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Mathur, V.; Shin, J.K.; Subramanian, C. Misallocation of debt and aggregate productivity. J. Corp. Financ. 2023, 83, 102493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P. Subsidized or not, the impact of firm internationalization on green innovation—Based on a dynamic panel threshold model. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 806999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saidi, F.; Žaldokas, A. How does firms’ innovation disclosure affect their banking relationships? Manag. Sci. 2021, 67, 742–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, I. Information in financial markets and its real effects. Rev. Financ. 2023, 27, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wei, H. Digital transformation and enterprise financial asset allocation. Appl. Econ. 2025, 57, 2106–2123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, W. The impact of integrating technology and finance on firm entry: Evidence from China’s FinTech pilot policy. Financ. Res. Lett. 2024, 70, 106300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayerbe, C.; Azzam, J.; Boussetta, S.; Pénin, J. Revisiting the consequences of loans secured by patents on technological firms’ intellectual property and innovation strategies. Res. Policy 2023, 52, 104824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdin, J.; Sharma, A.; Trivedi, R.; Wang, C. Financing constraints, intellectual property rights protection and incremental innovation: Evidence from transition economy firms. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2024, 198, 122982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Wang, X. The impact of patent protection on technological innovation: A global value chain division of labor perspective. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2024, 203, 123370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldsmith, R.W. Financial and Structure and Development; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, A.; Cincera, M. Determinants of financing constraints. Small Bus. Econ. 2022, 58, 1427–1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Deng, X.; Wang, D.; Pan, X. Financial regulation, financing constraints, and enterprise innovation performance. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2024, 95, 103387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Blick, T.; Paeleman, I.; Laveren, E. Financing constraints and SME growth: The suppression effect of cost-saving management innovations. Small Bus. Econ. 2024, 62, 961–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Li, X.; Li, Z.; Ye, Y. The effects of government support on enterprises’ digital transformation: Evidence from China. Manag. Decis. Econ. 2023, 44, 2520–2539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, K.; Wang, X. Do government subsidies promote enterprise innovation?—Evidence from Chinese listed companies. J. Innov. Knowl. 2023, 8, 100436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, J.; Cui, Z.Y.A.; Kewley, D. Government finance, loans, and guarantees for small and medium enterprises (SMEs) (2000–2021): A systematic review. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2024, 62, 2607–2637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhao, Q. Banking competition, credit financing and the efficiency of corporate technology innovation. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2024, 94, 103248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Zheng, M. Does sci-tech finance promote Chinese firms to engage in green innovation? Sci. Res. 2025, 43, 1237–1249. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, Y.; Jin, X. How does technology finance promote the high-quality development of firms? Evidence from China. Financ. Res. Lett. 2024, 69, 106186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sogorb-Mira, F. How SME uniqueness affects capital structure: Evidence from a 1994–1998 Spanish data panel. Small Bus. Econ. 2005, 25, 447–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, G.Z.; Leccese, M.; Wagman, L. M&A and technological expansion. J. Econ. Manag. Strat. 2024, 33, 338–359. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, J.; Wang, Z. Insight into the nexus between intellectual property pledge financing and enterprise innovation: A systematic analysis with multidimensional perspectives. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2024, 93, 700–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Z.; Cao, A.; Guo, J. Research on the employment effect of artificial intelligence based on patent data: Micro evidence from Zhongguancun enterprises. China Ind. Econ. 2021, 11, 137–154. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, J.; Lin, G.; Xiao, W. The heterogeneity of innovation, government R&D support and enterprise innovation performance. Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2022, 62, 101741. [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Chen, X. Financial Resource Allocation Efficiency and Total Factor Productivity in China’s Manufacturing Sector. J. Manag. World 2024, 40, 96–128. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, N.; Li, M. Research on collaborative innovation behavior of enterprise innovation ecosystem under evolutionary game. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2024, 206, 123508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Xu, W.; Kung, C.C. The impact of data elements on urban sustainable development: Evidence from the big data policy in China. Technol. Soc. 2025, 81, 102800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Zhan, Y.; Lin, B. Scale Effect and Innovation Effect of New Energy Enterprises’ Value-Added Tax Incentives. In Chinese Governance and Transformation Towards Carbon Neutrality; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2025; pp. 285–313. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.; Li, Z.; Qiu, Z.; Wang, J.; Liu, B. ESG performance and corporate technology innovation: Evidence from China. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2024, 206, 123520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moshirian, F.; Tian, X.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, W. Stock market liberalization and innovation. J. Financ. Econ. 2021, 139, 985–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.; Wang, M.; Chen, K. Can science and technology finance promote high-quality development of enterprises? Sci. Res. Manag. 2023, 44, 83. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, H.; Wang, B.; Xu, Y. Green Financial Innovation, Financial Resource Allocation and Enterprise Pollution Reduction. China Ind. Econ. 2023, 51, 118–136. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Whited, T.M.; Wu, G. Financial constraints risk. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2006, 19, 531–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Wang, J. Is innovation strategy a catalyst to solve social problems? The impact of R&D and non-R&D innovation strategies on the performance of social innovation-oriented firms. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2024, 199, 123020. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, S.; Wang, M. Can the technology and financial policy improve the R&D investment of science andtechnology enterprises?—Empirical evidence from the pilot policy. Stud. Sci. Sci. 2023, 42, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Callaway, B.; Sant’Anna, P.H.C. Difference-in-differences with multiple time periods. J. Financ. Econ. 2021, 225, 200–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acemoglu, D.; Akcigit, U.; Alp, H.; Bloom, N.; Kerr, W. Innovation, reallocation, and growth. Am. Econ. Rev. 2018, 108, 3450–3491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Gan, Y.; Bi, S.; Fu, H. Substantive or strategic? Unveiling the green innovation effects of pilot policy promoting the integration of technology and finance. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2025, 97, 103781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).