Simple Summary

The link between ocean chemistry and Early Triassic biotic recovery in the Chaohu Area remains unclear. Geochemical analyses (pyrite content, δ13Corg, pyrite S isotopes, and V/(V + Ni) ratios) of the northern Pingdingshan section reveal recurrent long-term ocean anoxia in this period, interrupted by two oxic intervals in the early Spathian. A positive δ13Corg shift (~4‰) at the Smithian/Spathian boundary was associated with significant biotic recovery due to oxic conditions, coincident with a positive δ34S excursion (~25‰) and low V/(V + Ni) ratios. Although the second episode of oxic conditions occurred in the late early Spathian, frequent environmental perturbations may have aborted the biotic recovery. Recurrent and long-term ocean anoxia made sustained recovery impossible in the Early Triassic.

Abstract

The influence of ocean chemistry on Early Triassic biotic recovery is poorly understood in the Chaohu Area. Here, we evaluate the influence of ocean chemistry following the Permian–Triassic crisis using pyrite content, δ13Corg, and S isotopic composition of pyrite. The pyrite content, V/(V + Ni) ratio, and S isotopic composition of pyrite in the Early Triassic from the northern Pingdingshan section of the Chaohu area in eastern China reveal recurrent and long-term ocean anoxia and two episodes of oxic conditions that occurred in the earliest Spathian and the late early Spathian. A positive δ13Corg shift of ~4‰ around the Smithian/Spathian boundary (SSB) in the lowermost Spathian was associated with significant biotic recovery, coincident with a positive δ34S excursion of ~25‰ and a low V/(V + Ni) ratio. The results suggest that the oxic conditions contributed to this recovery. Enhanced global ocean circulation during the SSB climate cooling may also have promoted this recovery. Frequent environmental perturbations may have aborted the biotic recovery, although the second episode of oxic conditions occurred in the late early Spathian. Sustained recovery did not appear in the Early Triassic because of the recurrent and long-term ocean anoxia.

1. Introduction

Oceanic anoxia is considered to be the main contributor to the end-Permian mass extinction [1,2,3,4,5,6,7]. However, whether oceanic anoxia controlled the biotic recovery in the Early Triassic remains uncertain. Previous research has shown that the initial biological recovery began just after the end-Permian crisis [8,9,10,11]; however, the full marine ecosystem recovery occurred during the Middle Triassic [12,13]. Sustained euxinia or anoxia may explain the protracted recovery in the Early Triassic [6,14,15,16,17,18], although other factors like global warming caused by elevated atmospheric CO2 may have affected some marine invertebrates in the Early Triassic [19]. The size distribution of framboidal pyrites and S-isotope of the pyrites data from the East Greenland Basin suggest that the oceanic anoxia that developed after the end-Permian extinction event may have delayed the biotic recovery during the Early Triassic [20]. Zhou et al. [21] proposed that the incursion of euxinic waters into the surface waters delayed marine ecosystem recovery during the Early Triassic. We show that the northern Pingdingshan section of the Chaohu Area in eastern China provides strong evidence for intervals of ocean oxidation and recurrent, long-term anoxia in the Early Triassic based on the data of pyrite content, V/(V + Ni) ratio, and δ13Corg and S isotopic composition of pyrite. The recurrent and long-term oceanic anoxia played a significant role in delaying the Early Triassic recovery.

2. Samples and Methods

2.1. Sample Information

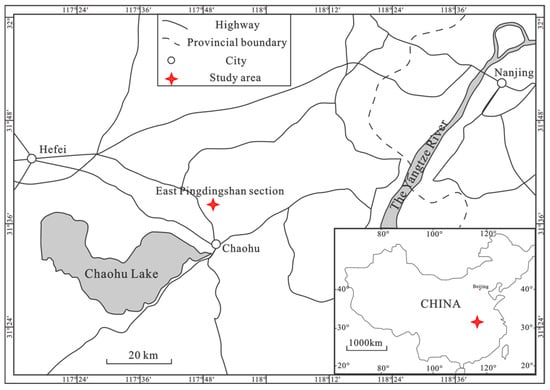

Forty-two samples numbered N1 to N42 from the Middle Permian Gufeng Formation to the Lower Triassic Nanlinghu Formation were collected from the northern Pingdingshan section of the Chaohu area in Anhui Province, eastern China (Figure 1, Table 1). Unabridged Upper Permian to Lower Triassic was developed in this area, which makes it a typical area for Permain–Triassic research. Mudstones and siliceous mudstones, silty mudstones, and siliceous shales (or mudstones) developed in the Middle Permian Gufeng Formation, Upper Permian Longtan, and Dalong Formation, respectively (Figure 2). Calcareous mudstones and limestones (containing laminated calcareous mudstones) primarily developed in the Lower Triassic Yinkeng and Helongshan Formations, respectively, while limestones with laminated shales developed in the Lower Triassic Nanlinghu Formation (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Location of northern Pingdingshan section of the Chaohu area, Anhui Province, eastern China.

Table 1.

The distribution of Pyrite content, V/(V + Ni), and δ34S and δ13Corg values for the northern Pingdingshan section of the Chaohu area in Anhui Province, eastern China.

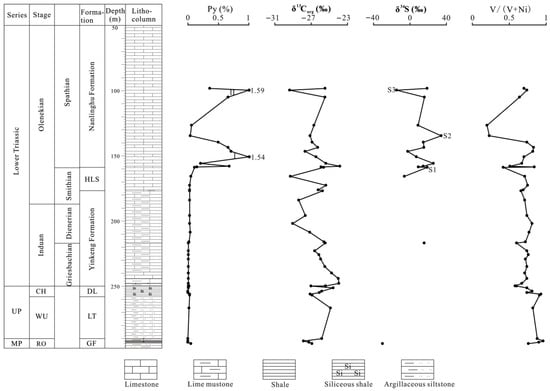

Figure 2.

Pyrite content, V/(V + Ni), and δ34S and δ13Corg values for the northern Pingdingshan section of the Chaohu area, eastern China. MP = Middle Permian, UP = Upper Permian, RO = Roadian-Wordian, WU = Wuchiapingian, CH = Changhsingian, GF = Gufeng Formation, LT = Longtan Formation, DL = Dalong Formaion, and HLS = Helongshan Formation.

2.2. Methods

Samples were ground to a 200-mesh particle size using an agate mortar and pestle. Detailed experimental conditions and operational protocols for trace element analysis were previously documented in the work of Li et al. [22]. Pyrite content was quantified based on the concentration of pyrite-bound sulfur (FeS2), which was extracted using a CrCl2 reduction method and precipitated as Ag2S in silver nitrate trapping solutions [23]. For the determination of pyrite sulfur isotopic compositions (δ34S), the Ag2S precipitates derived from the aforementioned CrCl2 reduction procedure were analyzed using a Thermo Fisher Scientific Delta V Plus isotope ratio mass spectrometer (IRMS) coupled to a Flash elemental analyzer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The δ34S values are reported relative to the VCDT standard. Analytical precision was evaluated through replicate measurements of three international reference materials as follows: IAEA S1 (−0.3‰), IAEA S2 (+22.65‰), and IAEA S3 (−32.5‰), with the resultant precision better than ±0.2‰ (1σ).

Organic carbon isotopic compositions were assayed using a Finnigan DeltaPlus XL IRMS instrument connected to a CE flash1112 EA via a ConfloIII interface (Finnigan MAT, Bremen, Germany). Samples were subjected to high-temperature combustion under a helium carrier gas atmosphere, converting organic carbon into carbon dioxide (CO2). The generated CO2 was isolated via chromatographic separation before being introduced into the mass spectrometer for isotopic analysis. δ13C values are reported relative to VPDB standard. Each sample was analyzed a minimum of two times, and the variation between replicate measurements did not exceed 0.3‰. The final δ13C result for each sample was defined as the average value of the duplicate analyses.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Redox Conditions During the Permian–Triassic Crisis

Pyrite is commonly distributed in the Late Permian to Early Triassic strata of the Chaohu area [24,25]. Samples from the Gufeng, Longtan, Dalong, Yinkeng, and Helongshan Formations exhibit extremely low pyrite contents, with nearly all the samples containing <0.1% pyrite (Table 1, Figure 2), which may indicate non-euxinic conditions during the Roadian–Wordian to the Smithian. Pyrite contents for the samples in the Lower Triassic Nanlinghu Formation vary between 0.04 and 1.59%, with an average of 0.60% (Table 1, Figure 2). The pyrite contents exhibit two clear shifts, which may suggest two episodes of euxinic conditions (episodes I and II) during the Spathian (Figure 2).

V/(V + Ni) ratios are commonly used to discuss redox conditions because V becomes more enriched than Ni in anoxic environments [26]. A V/(V + Ni) ratio >0.60 may suggest anoxic bottom-water conditions [27,28]. Samples from the Gufeng, Dalong, Longtan, and Yinkeng Formations are characterized by high V/(V + Ni) ratios of >0.60 (only one <0.60%, 0.58), indicating predominantly anoxic bottom-water conditions during the Roadian–Wordian to the early Smithian. The V/(V + Ni) ratios in the Helongshan and Nanlinghu Formations range from 0.42 to 0.75 and 0.20 to 0.84, respectively, with mean values of 0.64 and 0.64 (Table 1, Figure 2), respectively, suggesting brief oxic depositional conditions during the Spathian, although most time periods exhibit anoxic bottom-water conditions. Similar findings were also presented by Du et al. [29].

Pyrite sulfur isotopes were introduced to reconstruct the ocean chemistry of the Phanerozoic biodiversity and extinction [15,20,30,31,32]. We used δ34S of pyrite to evaluate the influence of ocean chemistry during the Permian–Triassic crisis. Only two δ34Ss for pyrite values were detected from the Gufeng to the Yinkeng Formation due to the extremely low pyrite content (Figure 2). Figure 2 demonstrates that the δ34S values exhibit a wide range from the late Smithian to the middle Spathian. A positive δ34S excursion occurs from –6.0‰ to +18.9‰ (S1 in Figure 2) in the lowermost Spathian. This positive δ34S excursion may be associated with the short-lived oxic bottom-water conditions suggested by a lower V/(V + Ni) ratio (0.42) (Figure 2). Tian et al. also reported this oxic event during this interval [33]. The δ34S values first exhibit a stepwise negative excursion and then a stepwise positive excursion in the early Spathian, which reaches +34.2‰ in the late early Spathian (S2 in Figure 2). This positive excursion suggests oxic bottom-water conditions, which are also evidenced by the V/(V + Ni) ratio and pyrite content. The δ34S values exhibit a stepwise negative trend from the late early Spathian to the middle Spathian. A negative δ34S shift of ~30‰ is exhibited in the middle Spathian (S3 in Figure 2) which is associated with euxinia during episode II.

3.2. Biotic Recovery During the Early Triassic

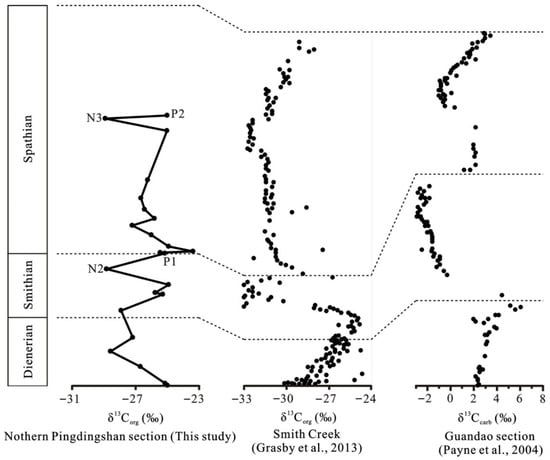

In the northern Pingdingshan section of the Chaohu area, the δ13Corg values display stable characteristics in the Roadian–Wordian, followed by a positive excursion of ~2‰ in the Roadian–Wordian to Wuchiapingian boundary. The δ13Corg values exhibit a stepwise positive shift in the Changhsingian, followed by a 2–3‰ decline in the Permian–Triassic boundary. There was a brief stepwise positive excursion in the Early Griesbachian, followed by a continued decline in δ13Corg through the Early Griesbachian to Middle Dienerian, suggesting that the initial biotic recovery after the Permian–Triassic crisis was winding or aborted. The sustained anoxia evidenced by V/(V + Ni) ratios during Early Triassic may have been responsible for the aborted initial recovery. There is a 4‰ negative δ13Corg excursion in the late Smithian. The similarly negative excursions of δ13Corg in the late Smithian are also reported in the Smith Creek section of the Sverdrup Basin in Canada [10], Guandao section in Guizhou, China [34], and Zal section in Iran [35]. The δ13Corg excursion ranges reach up to 9‰ in the Smith Creek section (Figure 3). This negative shift is associated with anoxic conditions that resulted in the Smithian ammonoid and conodont extinction [9,36]. A high temperature was also a critical contributor to the end-Smithian crisis [37]. Climatic warming dating from the earliest Smithian and sea surface temperatures in the late Smithian may have reached a peak of ~40 °C based on the conodont oxygen isotopes [37,38].

Figure 3.

Correlations between the δ13C profiles of representative sections in the world during the Permian–Triassic biotic crisis [10,34].

An important recovery occurred in the early Spathian due to oxic conditions, as evidenced by the positive δ13Corg shift that occurred around the Smithian/Spathian boundary (SSB) in the lowermost Spathian, which coincided with a positive δ34S excursion of ~25‰ and low V/(V + Ni) ratio (0.42) (Figure 2). This positive δ13Corg shift, which we observed in the lowermost Spathian from the northern Pingdingshan section, is consistent with organic carbon isotopes from the Smith Greek section [10] and inorganic carbon isotopes from the Guandao section [34] (Figure 3). The organic carbon isotope data in the Salt Range and Surghar Range sections also recorded this positive shift [39]. Therefore, the positive excursion of δ13Corg and δ13Ccarb in the lowermost Spathian was global. We believe that the biotic recovery in the earliest Spathian can be attributed to the oxic conditions observed in this study. The climatic cooling event from the latest Smithian to early Spathian that enhanced the global ocean circulation [40] and promoted marine productivity [41] also contributed to this recovery. Two episodes of euxinic conditions occurred in the early and middle Spathian in this study area. Although the second oxic event occurred in the late early Spathian, as evidenced by the positive δ34S excursion and low V/(V + Ni) ratio, biotic recovery did not occur because of the environmental perturbations. A ~4‰ decrease in the δ13Corg excursion occurred in the middle Spathian and coincided with a negative δ34S excursion of ~30‰ during episode II (Figure 2). This result suggests that ocean anoxia or euxinia contributed to the aborted biotic recovery. The Yiwagou section from the Qinling Sea records the anoxic environment in the Early Spathian [42]. A similar negative δ13Corg shift in the middle Spathian also exists in the Smith Greek and Guandao sections (Figure 3).

4. Conclusions

The northern Pingdingshan section of the Chaohu area, eastern China, provides strong evidence for intervals of ocean oxidation and recurrent, long-term anoxia that controlled biotic recovery in the Early Triassic. The initial biotic recovery after the Permian–Triassic crisis was winding or aborted because of the sustained ocean anoxia observed in this study area. A global biotic recovery in the earliest Spathian is attributed to oxic conditions and enhanced global ocean circulation during the SSB climate cooling. Although the oxic environment interval occurred in the late early Spathian in the northern Pingdingshan section, the negative δ13Corg excursion event indicative of anoxic conditions reveals that the environmental perturbations restrained the biotic recovery. This similar negative δ13Corg excursion event also exists in the Smith Greek (Arctic Canada) and Guandao (Guizhou Area of China) sections in the late early Spathian. Recurrent and long-term ocean anoxia made sustained recovery impossible in the Early Triassic.

Author Contributions

W.L. contributed to designing the study, writing the manuscript, and was the principal author of the manuscript. B.Y. contributed to the discussion of the results and manuscript refinement. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42472193) and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (25CX02009A).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the reviewers and the editor for their valuable comments for this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Wignall, P.B.; Twitchett, R.J. Oceanic anoxia and the End Permian mass extinction. Science 1996, 272, 1155–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isozaki, Y. Permo-Triassic boundary superanoxia and stratified superocean: Records from lost deep sea. Science 1997, 276, 235–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kump, L.R.; Pavlov, A.; Arthur, M.A. Massive release of hydrogen sulfide to the surface ocean and atmosphere during intervals of oceanic anoxia. Geology 2005, 33, 397–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, K.M.; Kump, L.R.; Ridgwell, A. Biogeochemical controls on photic-zone euxinia during the end-Permian mass extinction. Geology 2008, 36, 747–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennecka, G.A.; Herrmann, A.D.; Algeo, T.J.; Anbar, A.D. Rapid expansion of oceanic anoxia immediately before the end-Permian mass extinction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 17631–17634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, J.L.; Clapham, M.E. End-Permian mass extinction in the oceans: An ancient analog for the twenty-first century? Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 2012, 40, 89–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarkson, M.O.; Wood, R.A.; Poulton, S.W.; Richoz, S.; Newton, R.J.; Kasemann, S.A.; Bowyer, F.; Krystyn, L. Dynamic anoxic ferruginous conditions during the end-Permian mass extinction and recovery. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 12236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brayard, A.; Escarguel, G.; Bucher, H.; Monnet, C.; Brühwiler, T.; Goudemand, N.; Galfetti, T.; Guex, J. Good genes and good luck: Ammonoid diversity and the end-Permian mass extinction. Science 2009, 325, 1118–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, S.M. Evidence from ammonoids and conodonts for multiple Early Triassic mass extinction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 15264–15267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grasby, S.E.; Beauchamp, B.; Embry, A.; Sanei, H. Recurrent Early Triassic ocean anoxia. Geology 2013, 41, 175–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, H.Y.; Shen, J.; Schoepfer, S.D.; Krystyn, L.; Richoz, S.; Algeo, T.J. Environmental controls on marine ecosystem recovery following mass extinctions, with an example from the Early Triassic. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2015, 149, 108–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.Q.; Tong, J.; Fraiser, M.L. Trace fossils evidence for restoration of marine ecosystems following the end-Permian mass extinction in the Lower Yangtze region, South China. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2011, 299, 449–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.Q.; Benton, M.J. The timing and pattern of biotic recovery following the end-Permian mass extinction. Nat. Geosci. 2012, 5, 375–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grice, K.; Cao, C.Q.; Love, G.D.; Bottcher, M.E.; Twichett, R.J. Photic zone euxinia during the Permian-Triassic superanoxic event. Science 2005, 307, 706–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fenton, S.; Grice, K.; Twitchett, R.J.; Böttcher, M.E.; Looy, C.V.; Nabbefeld, B. Changes in biomarker abundances and sulfur isotopes of pyrite across the Permian-Triassic (P/Tr) Schuchert Dal section (East Greenland). Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2007, 262, 230–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.J.; Wignall, P.B.; Tong, J.N.; Bond, D.P.G.; Song, H.Y.; Lai, X.L.; Zhang, K.X.; Wang, H.M.; Chen, Y.L. Geochemical evidence from bio-apatite for multiple oceanic anoxic events during Permian–Triassic transition and the link with end-Permian extinction and recovery. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2012, 353–354, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metcalfe, I.; Nicoll, R.S.; Willink, R.; Ladjavadi, M.; Grice, K. Early Triassic (Induan–Olenekian) conodont biostratigraphy, global anoxia, carbon isotope excursions and environmental perturbations: New data from Western Australian Gondwana. Gondwana Res. 2013, 23, 1136–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, R.; Oba, M.; Kaiho, K.; Schaeffer, P.; Adam, P.; Takahashi, S.; Nara, F.W.; Chen, Z.Q.; Tong, J.N.; Tsuchiya, N. Extreme euxinia just prior to the Middle Triassic biotic recovery from the latest Permian mass extinction. Org. Geochem. 2014, 73, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraiser, M.L.; Bottjer, D.J. Elevated atmospheric CO2 and the delayed biotic recovery from the end-Permian mass extinction. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2007, 252, 164–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, J.K.; Shen, Y.A.; Piasecki, S.; Stemmerik, L. No abrupt change in redox condition caused the end-Permian marine ecosystem collapse in the East Greenland Basin. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2010, 291, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.F.; Algeo, T.J.; Ruan, X.Y.; Luo, G.M.; Chen, Z.Q.; Xie, S.C. Expansion of photic-zone euxinia during the Permian-Triassic biotic crisis and its causes: Microbial biomarker records. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2017, 474, 140–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.H.; Zhang, Z.H.; Li, Y.C.; Fu, N. The effect of river-delta system on the formation of the source rocks in the Baiyun Sag, Pearl River Mouth Basin. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2016, 76, 279–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canfield, D.E.; Raiswell, R.; Westrich, J.T.; Reaves, C.M.; Berner, R.A. The use of chromium reduction in the analysis of reduced inorganic sulfur in sediments and shales. Chem. Geol. 1986, 54, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Chen, Z.Q.; Wignall, P.B.; Zhao, L. Latest Permian to Middle Triassic redox condition variations in ramp settings, South China: Pyrite framboid evidence. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 2017, 129, 229–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.Y.; Du, Y.; Algeo, T.J.; Tong, J.N.; Owens, J.D.; Song, H.J.; Tian, L.; Qiu, H.O.; Zhu, Y.Y.; Lyons, T.W. Cooling-driven oceanic anoxia across the Smithian/Spathian boundary (mid-Early Triassic). Earth-Sci. Rev. 2019, 195, 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algeo, T.J.; Maynard, J.B. Trace-element behavior and redox facies in core shales of Upper Pennsylvanian Kansas-type cyclothems. Chem. Geol. 2004, 206, 289–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joachimski, M.M.; Ostertag-Henning, C.; Pancost, R.D.; Strauss, H.; Freeman, K.H.; Littke, R.; Sinninghe Damsté, J.S.; Racki, G. Water column anoxia, enhanced productivity and concomitant changes in δ13C and δ34S across the Frasnian-Famennian boundary (Kowala—Holy Cross Mountains/Poland). Chem. Geol. 2001, 175, 109–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.G.; Trela, W.; Jiang, S.Y.; Nielsen, J.K.; Shen, Y.A. Major oceanic redox condition change correlated with the rebound of marine animal diversity during the Late Ordovician. Geology 2011, 39, 675–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Song, H.Y.; Corso, J.D.; Wang, Y.H.; Zhu, Y.Y.; Song, H.J.; Tian, L.; Chu, D.L.; Huang, J.D.; Tong, J.N. Paleoenvironments of the Lower Triassic Chaohu Fauna, South China. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2023, 617, 111497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.G.; Shen, Y.A.; Zhan, R.B.; Shen, S.Z.; Chen, X. Large perturbations of the carbon and sulfur cycle associated with the Late Ordovician mass extinction in South China. Geology 2009, 37, 299–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabbefeld, B.; Grice, K.; Twitchett, R.J.; Summons, R.E.; Hays, L.; Böttcher, M.E.; Asif, M. An integrated biomarker, isotopic and palaeoenvironmental study through the Late Permian event at Lusitaniadalen, Spitsbergen. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2010, 291, 84–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Feng, Q.L.; Algeo, T.J.; Li, C.; Planavsky, N.J.; Zhou, L.; Zhang, M.L. Two pulses of oceanic environmental disturbance during the Permian-Triassic boundary crisis. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2016, 443, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, L.; Tong, J.N.; Algeo, T.J.; Song, H.J.; Song, H.Y.; Chu, D.L.; Shi, L.; Bottjer, D.J. Reconstruction of Early Triassic ocean redox conditions based on framboidal pyrite from the Nanpanjiang Basin, South China. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2014, 412, 68–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, J.L.; Lehrmann, D.J.; Wei, J.; Orchard, M.J.; Schrag, D.P.; Knoll, A.H. Large perturbations of the carbon cycle during recovery from the end-Permian extinction. Science 2004, 305, 506–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horacek, M.; Richoz, S.; Brandner, R.; Krystyn, L.; Spötl, C. Evidence for recurrent changes in Lower Triassic oceanic circulation of the Tethys: The δ13C record from marine sections in Iran. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2007, 252, 355–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orchard, M.J. Conodont diversity and evolution through the latest Permian and Early Triassic upheavals. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2007, 252, 93–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.D.; Joachimski, M.M.; Wignall, P.B.; Yan, C.B.; Chen, Y.L.; Jiang, H.S.; Wang, L.N.; Lai, X.L. Lethally Hot Temperatures During the Early Triassic Greenhouse. Science 2012, 338, 366–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Orchard, M.J.; Brayard, A.; Algeo, T.J.; Zhao, L.S.; Chen, Z.Q.; Lyu, Z.Y. The Smithian/Spathian boundary (late Early Triassic): A review of ammonoid, conodont, and carbon-isotopic criteria. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2019, 195, 7–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermann, E.; Hochuli, P.A.; Méhay, S.; Bucher, H.; Bruhwiler, T.; Ware, D.; Hautmann, M.; Roohi, G.; Yaseen, A. Organic matter and palaeoenvironmental signals during the Early Triassic biotic recovery: The Salt Range and Surghar Range records. Sediment. Geol. 2011, 234, 19–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.Y.; Tong, J.N.; Algeo, T.J.; Horacek, M.; Qiu, H.O.; Song, H.J.; Tian, L.; Chen, Z.Q. Large vertical δ13CDIC gradients in early Triassic seas of the South China craton: Implications for oceanographic changes related to Siberian Traps volcanism. Glob. Planet. Change 2013, 105, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, J.L.; Kump, L.R. Evidence for recurrent early Triassic massive volcanism from quantitative interpretation of carbon isotope fluctuations. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2007, 256, 264–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.X.; Wignall, P.B.; Jiang, H.S.; Zhang, M.H.; Wu, X.L.; Lai, X.L. A review of carbon isotope excursions, redox changes and marine red beds of the Early Triassic with insights from the Qinling Sea, northwest China. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2023, 247, 104623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.