Simple Summary

Climate change remains a critical focus in ecological research, and forests play a key role in storing carbon and slowing this process. However, it is still unclear how different forest structures and combinations of tree species affect the amount of carbon stored in forests. To better understand this, we studied several forest areas in Lishui City. We measured forest diversity, species types, and species numbers and calculated the carbon stock. We found that the greater the proportion of broad-leaved trees in a forest, the higher its carbon storage capacity. Our study showed that both niche complementarity and selection effects influenced carbon sequestration, with these two effects exhibiting an interactive relationship. When species diversity was low, niche complementarity enhanced forest carbon sequestration; when species diversity was high, selection effects diminished forest carbon sequestration. This study recommends prioritizing the planting of broad-leaved tree species during afforestation and paying attention to the current status of forest diversity.

Abstract

Global CO2 concentrations are gradually increasing, and forests, as the main terrestrial carbon pool, are attracting growing attention in mitigating climate change. However, the impacts of forest types, species diversity, structural diversity, and environmental factors on the carbon sequestration mechanisms of subtropical forests remain unclear. This study established 45 forest plots (20 m × 20 m) in Lishui City, aiming to investigate the relationships between forest diversity, environmental factors, and carbon storage of subtropical forests among different forest types. Results showed that coniferous forests had the lowest species diversity (0.86), which exhibited extremely significant differences from broad-leaved forests (1.47, p < 0.01) and coniferous broad-leaved mixed forests (1.58, p < 0.01). The carbon storage of broad-leaved forests was 97.50 t·ha−1, which was higher than that of coniferous broad-leaved mixed forests (77.08 t·ha−1) and coniferous forests (75.57 t·ha−1). The carbon storage of coniferous forests was significantly positively affected by species diversity (p < 0.05). Tree height was the most significant structural diversity factor affecting forest carbon storage (p < 0.05). The results of the structural equation model (SEM) showed that the proportion of broad-leaved trees in forests and structural diversity had a significant positive effect on carbon storage (p < 0.01). Species diversity had a non-linear relationship with carbon storage. The ecological niche complementarity effect and selection effect interacted with changes in species diversity. When the species diversity was lower than 1.12 (Shannon–Wiener index), the ecological niche complementarity effect dominated and promoted carbon sequestration; when it was above this threshold, the selection effect dominated and weakened carbon sequestration. This study recommends prioritizing the planting of broad-leaved tree species during afforestation and paying attention to the current status of forest diversity.

1. Introduction

Human activities have led to elevated levels of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, which are contributing to climate change [1]. As the primary terrestrial reservoir for CO2, forests play an indispensable role in mitigating climate change [2,3,4]. As climate change intensifies, forest carbon storage has attracted widespread attention and become a research focus [1,5,6,7]. Currently, forests cover more than 30% of the Earth’s land surface [8,9]. Forest ecosystems serve not only as major terrestrial carbon sinks but also as the largest carbon reservoirs [6,7,9,10]. Studies have shown that increasing forest cover and biomass can effectively enhance carbon storage and reduce atmospheric carbon concentrations, making this one of the most significant strategies for alleviating global climate change [11,12]. Therefore, exploring strategies to increase forest carbon stocks has emerged as a central challenge in addressing the potential impacts of climate change [11].

Recent studies have demonstrated that forest types exhibit distinct patterns of carbon storage capacity across various geographical regions [13]. In temperate zones, coniferous forests typically store more tree biomass carbon than broad-leaved forests [14]. Conversely, in tropical regions, broad-leaved forests generally possess significantly higher carbon stocks than coniferous forests [15]. These differences may be attributed to species-specific adaptive traits, as coniferous species are primarily distributed in mid- to high-latitude regions, whereas broad-leaved species are more prevalent in low- to mid-latitude regions. While current research has predominantly focused on temperate and tropical forests, subtropical ecosystems have remained comparatively understudied. As a critical component of the global carbon cycle, subtropical forests play a vital role in mitigating global climate change [13]. Furthermore, there is considerable heterogeneity in the findings of subtropical forest studies. For instance, Wu et al. [13] found that broad-leaved trees in subtropical forests demonstrated higher carbon storage efficiency than coniferous trees, whereas Li et al. [16] suggested that coniferous species may outperform broad-leaved species in terms of carbon storage capacity. Existing studies have not clearly identified the non-linear relationship between species diversity and carbon storage in subtropical forests and the threshold effect, nor have they adequately explained the mechanism of the effect of stand structure diversity on the ecosystem. Therefore, there is a pressing need for further research on the carbon dynamics of subtropical forest ecosystems.

In addition to the type of forest, forest carbon storage is strongly influenced by the community structure and the species diversity [17,18,19], with structurally complex forests typically having greater carbon storage capacity [20]. The influence of biodiversity on forest carbon storage is primarily determined by two ecological mechanisms: niche complementarity and the selection effect [13]. The niche complementarity effect posits that differences in species’ ecological niches allow more complete occupation of available resource space, thereby enhancing resource use efficiency and forest productivity [21]. The selection effect, on the other hand, refers to the dominance of highly productive or functionally important species that positively influence ecosystem functioning [13,22]. While previous studies have confirmed that biodiversity plays a critical role in sustaining ecosystem functions in grassland systems, the mechanisms through which biodiversity affects forest ecosystems remain more complex [11,12,23]. These two mechanisms may act independently or interactively across different forest types or structural compositions to influence carbon storage [21]. Thus, further investigation is imperative to ascertain the relationship between forest biodiversity and carbon sequestration.

This study focuses on subtropical forests, aiming to enhance our understanding of the relationship between forest diversity and carbon storage in these ecosystems. Specifically, the study focuses on how the Shannon–Wiener index (H) affects the carbon stocks of coniferous forests, mixed forests, and broad-leaved forests and explores the actual impact of broad-leaved trees on forest carbon stocks and the underlying ecological mechanisms involved. In subtropical forests, we hypothesized that (1) broad-leaved tree species are more favorable for carbon accumulation than conifers; (2) forest diversity or structural diversity produce different influencing mechanisms on carbon stocks with different forest types; and (3) interactions exist between niche complementarity and selection effects in forests.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Field Investigation

The study site was located in Lishui City, situated in the southwestern part of Zhejiang Province, China (27°25′–28°95′ N, 118°41′–120°26′ E). The terrain is dominated by hills and low mountains, with a total area of approximately 1.73 × 104 km2. The region experiences a typical mid-subtropical monsoon climate, characterized by warm and humid conditions, abundant rainfall, and distinct mountain climate features [24]. The forest types at the study site included coniferous forest (CF), coniferous and broad-leaved mixed forest (MF), and broad-leaved forest (BF). A total of 45 plots were chosen, with 15 plots for each forest type (Table 1).

Table 1.

Detailed information of the study sites.

The forest plots measured were 20 × 20 m [13]. All woody plants with a diameter at breast height (DBH) ≥ 5 cm within each subplot were recorded for DBH, tree height (TH), and crown length (CW). Field surveys were conducted from August to October 2024. Species identification was carried out based on the Catalogue of Life China: 2023 Annual Checklist [25].

2.2. Diversity Indices and Environmental Variables

We utilized the H to represent plant species diversity based on the relative abundance of species [26]. Stand structural diversity was represented by the coefficients of variation (CVs) of DBH (CVDBH, %), tree height (CVTH, %), and crown width (CVCW, %) for each plot [13,27]. The Shannon–Wiener index was calculated by the following formula:

where Pi indicates the proportion of individuals of a given species relative to the total number of individuals in the community.

This study utilized five environmental factors, including altitude, slope, aspect, mean annual temperature (MAT), and mean annual precipitation (MAP). Altitude, slope, and aspect were measured using RTK and a compass in forest plots, and MAT and MAP were sourced from the WorldClim database (http://www.worldclim.org). We used ArcGIS Pro 3.2.0 (Environmental Systems Research Institute, Inc., Berkeley, CA, USA, Reference ID: 1156174312) to obtain the MAT and MAP data for each forest plot. We used principal component analysis (PCA) to analyze environmental factors [13].

2.3. Carbon Stock Estimation

Aboveground biomass was estimated using allometric growth equations (Table S1). For species lacking specific equations, a general genus- or family-level equation was applied, and no previously unrecorded species were identified during the survey. Carbon stocks were calculated from biomass, and species-specific carbon fractions are provided in Table S2 [24].

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Linear regression models were employed, and a least significant difference (LSD) test (p < 0.05) was used to assess statistical differences among forest types. A structural equation model (SEM) was employed to investigate the effects of environmental factors and forest diversity on carbon storage. We employed linear regression models to analyze the correlations among structural diversity factors and forest carbon stocks, and only those forest structural diversity factors that were significantly correlated with carbon stocks were included in the SEM modeling. We used the “piecewiseSEM” package to fit the SEM; the fitting criteria for the SEM were p > 0.05, a comparative fit index (CFI) > 0.95, a standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) < 0.08, and a root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) < 0.05 [13]. Before regression analyses, the normality of the data was assessed, and normality was improved using the “bestnormsize” package (Table S3). All variables were standardized using Z-scores to allow for comparisons across parameter estimates. All analyses were conducted using R-4.5.3.

3. Results

3.1. Environmental Factors, Forest Biological Diversity, and Carbon Storage

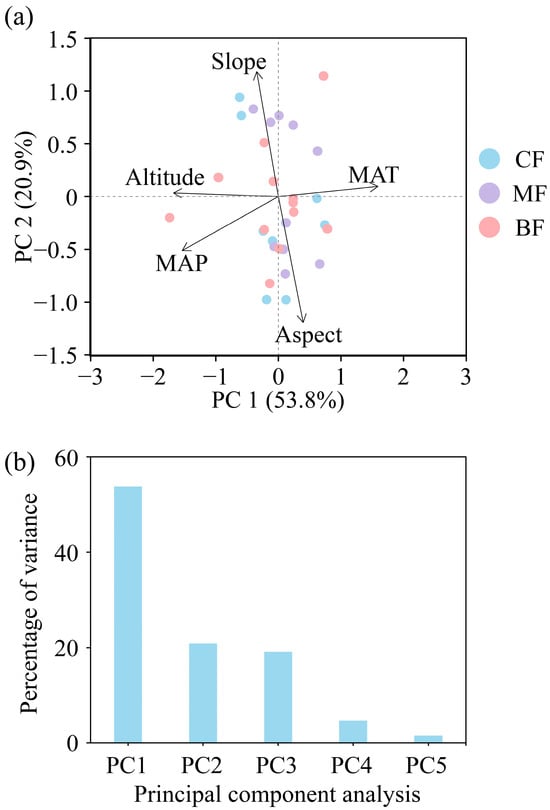

This study used PCA to analyze environmental factors (Figure 1a) and used the first axis (environmental PC1, Env PC1) and the second axis (environmental PC2, Env PC2) of PCA as predictors for subsequent analyses (Table 2). The results showed that the total explanatory power of the two axes reached 74.70% (Figure 1b), among which the PC1 axis represented slope gradient and aspect, while the PC2 axis represented altitude, MAT, and MAP.

Figure 1.

Principal component analysis (PCA) plot of environmental factors. (a) Environmental factors trait, (b) PCA percentage of variance. CF, coniferous forest; MF, coniferous and broad-leaved mixed forest; BF, broad-leaved forest; MAT, mean annual temperature; MAP, mean annual precipitation.

Table 2.

Component loadings and eigenvalues of principal components (PCs) chosen from PCA on environmental factors.

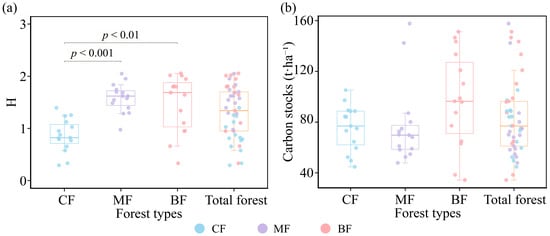

This investigation showed that the Shannon–Wiener index ranged from 0.29 to 2.06 in the study area. The Shannon–Wiener index differed significantly among the three forest types (Figure 2a). CF differed significantly from both BF and MF (p < 0.01), with the Shannon–Wiener indices of BF (1.47) and MF (1.58) both being higher than that of CF (0.86).

Figure 2.

Species diversity and carbon storage in different forest types. (a) Species diversity (calculated with the H index) in different forest types, (b) carbon storage in different forest types. CF, coniferous forest; MF, coniferous and broad-leaved mixed forest; BF, broad-leaved forest. Significant results were marked in the figure; non-significant results were not marked.

The results showed that mean carbon storage was 83.38 t·ha−1 in forest plots (Figure 2b). The average carbon storage for BF (97.50 t·ha−1) was higher than that of MF (77.08 t·ha−1) and CF (75.57 t·ha−1). The coefficient of variation in carbon storage for CF (0.24) was lower than that for MF (0.41) and BF (0.38), and the CF data showed minimal variation (Table 3).

Table 3.

Carbon stocks and Shannon–Wiener index (average and coefficient of variation) of different forest types.

3.2. Effects of Forest Diversity on Carbon Storage

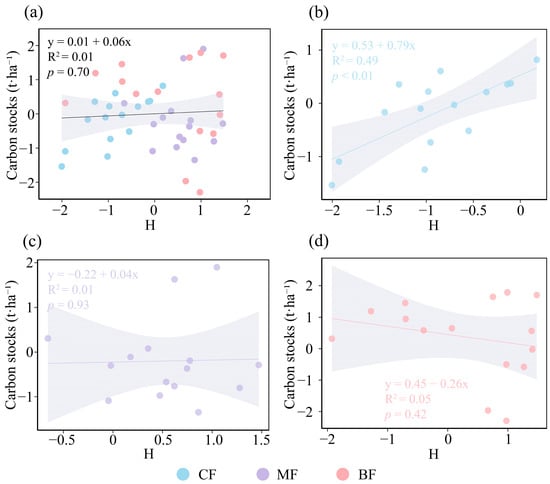

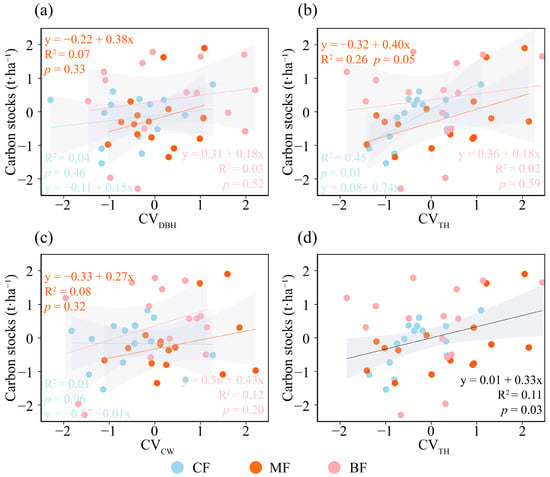

The results concerning the relationship between species diversity and forest carbon storage indicated that, in the overall forest analysis, species diversity did not exert a significant influence on forest carbon storage (Figure 3a). In CF, species diversity showed a significantly positive association with forest carbon storage (p <0.01, Figure 3b); in MF, species diversity did not have a significant effect on forest carbon storage (Figure 3c); and in BF, species diversity exhibited a negative association with forest carbon storage (Figure 3d). The relationship between structural diversity and carbon stocks varied among forest types. CVDBH demonstrated a modest positive influence on carbon storage across all three forest types (Figure 4a); CVTH exerted a significant positive effect on carbon storage in CF and MF, while showing a moderate positive influence in BF (p ≤ 0.05, Figure 4b); and CVCW had a modest positive impact on carbon storage in all forest types (Figure 4c). Overall, CVDBH and CVCW exhibited modest but non-significant positive effects on forest carbon storage, whereas CVTH showed a comparatively stronger and statistically significant positive effect (p ≤ 0.05, Figure 4d). Therefore, CVTH was selected as the structural diversity indicator for the SEM.

Figure 3.

Relationships between species diversity (calculated with the Shannon–Wiener index) of community and carbon stocks under different forest types. (a) Coniferous forest, (b) coniferous and broad-leaved mixed forest, (c) broad-leaved forest, (d) total forest. The solid lines represent the fitted regression line, accompanied by the coefficient of determination (R2) and p value. The gray shading indicates the 95% confidence band. CF, coniferous forest; MF, coniferous and broad-leaved mixed forest; BF, broad-leaved forest. All variables were Z-score transformed prior to analysis.

Figure 4.

Relationships between structural diversity (calculated with CVDBH, CVTH, and CVCW) of community and carbon stocks under different forest types. (a) Relationship between CVDBH and carbon storage in different forest types, (b) relationship between CVTH and carbon storage in different forest types, (c) relationship between CVCW and carbon storage in different forest types, (d) relationship between CVTH and carbon storage in total forest. The solid lines represent the fitted regression line, accompanied by the coefficient of determination (R2) and p value. The gray shading indicates the 95% confidence band. CF, coniferous forest; MF, coniferous and broad-leaved mixed forest; BF, broad-leaved forest. All variables were Z-score transformed prior to analysis.

3.3. Driving Factor Analysis of Forest Carbon Storage

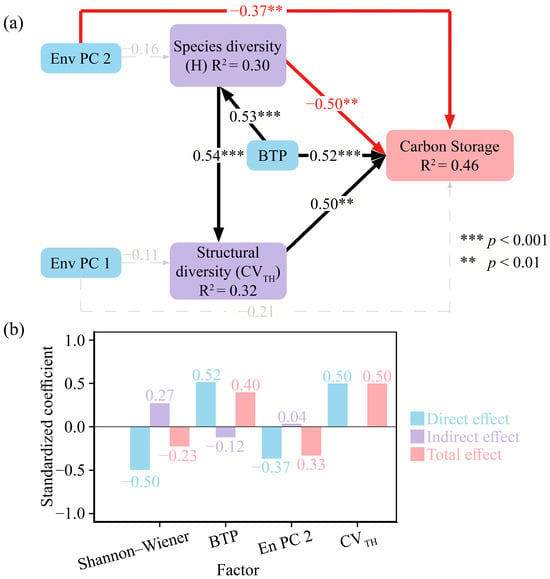

The SEM had a good fit (Table 4), explaining 46% of the variance in changes to carbon stocks (Figure 5a). The results of the structural equation model showed that both broad-leaf tree proportion, plant species diversity, and stand structural diversity influenced forest carbon stocks. The broad-leaf tree proportion and stand structural diversity (CVTH) had a significantly positive effect (p < 0.01) on carbon storage, with path coefficients of 0.52 and 0.50, respectively, while the species diversity had a significantly negative effect, with a path coefficient of −0.50. Furthermore, Env PC2 (slope and aspect) directly influenced (p < 0.01) the forest carbon stocks, with a path coefficient of −0.37.

Table 4.

Model fit statistic summary of the tested SEM for carbon stocks.

Figure 5.

Structural equation model presenting the effects of environmental variables, broad-leaved tree proportion, plant species diversity, and stand structural diversity on carbon stocks. (a) Path diagrams of factors influencing changes in carbon stocks, (b) total direct and indirect effects combined. Env PC1, environmental PC1; Env PC2, environmental PC2; H, Shannon–Wiener index; BTP, broad-leaved tree proportion; CVTH, coefficient of variation in tree height. All variables were Z-score transformed prior to analysis.

This study further analyzed the indirect effects and total impact effects of different variables on carbon stocks (Figure 5b). The results showed that plant species diversity had a positive indirect effect of 0.27 on carbon stocks. The indirect effect stems from the fact that species diversity, by influencing the proportion and structural diversity of broad-leaved trees, exerts an indirect effect on carbon storage. Combined with the direct effect and the indirect effect, it resulted in a total effect of −0.23 of plant species diversity on carbon stocks.

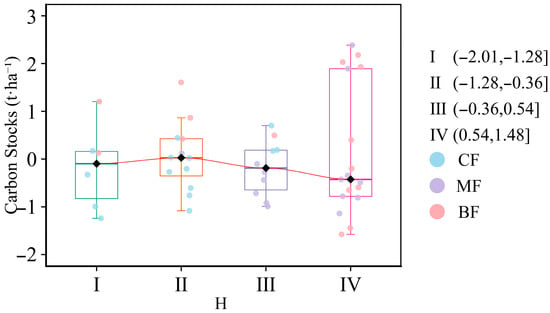

To analyze the negative correlation between species diversity and carbon stocks, the Shannon–Wiener index was segmented into four types (I, II, III, and IV) using the natural breaks method (Jenks), and the impacts of different Shannon–Wiener index values on carbon stocks were studied separately (Figure 6, Table S4). The results showed that when the Shannon–Wiener index was less than 1.12, carbon stocks exhibited an overall upward trend. After exceeding 1.12, carbon stocks showed an overall downward trend. Only 40% of forest plots exhibited an upward trend, while 60% exhibited a downward trend.

Figure 6.

Impact of the Shannon–Wiener index from the natural breaks method (Jenks) on carbon stocks. I, II, III, and IV were the natural breaks method (Jenks) classification for the Shannon–Wiener index. CF, coniferous forest; MF, coniferous and broad-leaved mixed forest; BF, broad-leaved forest. All variables were Z-score transformed prior to analysis.

4. Discussion

4.1. Broad-Leaved Trees and Forest Carbon Storage

We calculated the carbon stocks of three forest types, and the results supported our first hypothesis: broad-leaved forests exhibited higher carbon stocks than the other two forest types (Figure 2a). Other studies have reported similar findings in subtropical forests [13,28]. The results of the structural equation model (SEM) indicated that a higher proportion of broad-leaved trees was associated with greater forest carbon storage (Figure 5a). This outcome may be attributed to broad-leaved trees having a larger leaf area index, higher photosynthetic efficiency, and faster decomposition rate of litter, promoting nutrient cycling and biomass accumulation, thereby increasing carbon storage [29]. In addition, species with diverse functional traits may utilize ecosystem resources more efficiently [30]. It is therefore recommended that broad-leaved species be prioritized in forest management to effectively increase forest carbon stocks. Additionally, our research found that broad-leaved forests and coniferous and broad-leaved mixed forests exhibit relatively high CV values for carbon stocks, which may be related to their species composition [30,31], as broad-leaved trees include both hardwoods and softwoods. Although these trees are all classified as broad-leaved trees, their carbon sequestration capacity varies, which may influence forest carbon stocks [20]. This factor was not considered in the present study. The data might have had certain limitations, but this approach aligned better with natural conditions. Future research should place greater emphasis on distinguishing among different broad-leaved tree types.

4.2. Mechanism of Impact on Forest Carbon Storage

The findings of this study demonstrated that forest structure influences carbon storage, with higher forest structural diversity correlating with greater forest carbon stocks. Among the structural factors examined, CVTH emerged as the most significant variable, exerting a pronounced effect on forest carbon storage. A high coefficient of variation in tree height indicated a more complex vertical structure of the forest stand, which could better utilize resources such as light and water, indicated the total photosynthetic capacity of the community, and reflected the complementary effect of ecological niches [32]. We attributed this primarily to enhanced complementarity in trees’ utilization of vertical structural resources, which boosted forest photosynthesis [17]. Photosynthesis plays a significant role in the accumulation of biomass [33] and hence can significantly affect ecosystem carbon sinks; this represented the coordinated utilization of resources and embodied the principle of ecological niche complementarity [21,34]. Recent research has found that CVTH exhibited a significant effect on carbon storage, whereas CVDBH and CVCW had no significant impact [13]. The reason for this might be that the impacts of tree diameter at breast height and crown width on carbon storage are characterized by a delay [35]. Higher CVDBH and CVCW have relatively minor effects on forest coverage, as they require longer timeframes and larger scales to manifest their effects [36], while a larger CVTH may create gaps in the forest structure, facilitating sunlight penetration into the forest, and the increased light intensity within the forest further promotes carbon storage [37]. Due to scale limitations, only slope gradient and aspect showed significant effects on forest carbon stocks. This might indicate that at the scale of this study, ecosystems exhibited reduced sensitivity to variations in other environmental factors.

Current research suggests that actively modifying species diversity may yield immediate changes in forest carbon sinks [32]. There is ample support for positive biodiversity–ecosystem function relationships in forest studies performed [13,28,31]. The influence of biodiversity on forest carbon storage was primarily determined by two ecological mechanisms: niche complementarity and the selection effect [30,38]. However, our study showed that with the increase in biodiversity, there was a certain transition process between these two mechanisms. We argue that resources in each community are limited; before resources are fully utilized, the increase in diversity can enable more efficient resource utilization to enhance forest productivity, and niche complementarity dominates in this scenario [34]. And once this saturation point is exceeded, species with similar characteristics and functions would be redundant in the existing environment, reducing the positive impact of species diversity on community productivity, and the selection effect dominates in this case [39]; species competition might even reverse productivity [33]. Consistent with our third hypothesis, the results of the structural equation model (SEM) also supported this view, demonstrating that biodiversity exerted both negative and positive effects on carbon storage, and this negative correlation was the result of a threshold effect. At low diversity, species diversity still promoted carbon sinks; at high diversity, due to species functional redundancy and intensified competition, carbon sinks decreased. After the Shannon–Wiener index was classified using the Jenks method, the diversity saturation point for the communities in this study was found to be 1.12. However, our study showed that the proportion of broad-leaved trees, species diversity, structural diversity, and environmental factors have a relatively low overall impact on forest carbon storage (R2 = 0.46). We believe this may be attributed to the failure to consider complete root system data and soil data. Although the root-to-stem ratio (R:S) of subtropical forests is significantly lower than that of other forests (0.23 ± 0.02) [40], another reason is the lack of integration of soil data, and current studies have shown that soil nitrogen content affects carbon storage [13]. Due to its small scale and lack of integration with soil carbon data and complete root system data, this research still had limitations. Future studies should focus on expanding the research scale and considering factors such as tree species, root system, and soil conditions to enhance the accuracy of experimental results.

5. Conclusions

This study examined the mechanisms driving carbon storage in subtropical forests. The findings demonstrate that forest carbon stocks are jointly determined by tree species composition, stand structural diversity, and species diversity. Specifically, a higher proportion of broad-leaved trees increased carbon storage. Stand structural diversity, particularly the variation in tree height, exhibited a positive relationship with carbon accumulation. Moreover, the relationship between species diversity and carbon storage was non-linear, characterized by a threshold value (Shannon–Wiener index) of 1.12. Below this threshold, niche complementarity dominated, enhancing carbon sequestration; above it, the selection effect became dominant, weakening carbon sequestration.

These results highlight that attention should be paid to the current status of forest biodiversity, and broad-leaved trees should be prioritized for planting during afforestation to enable forests to achieve higher carbon sequestration efficiency. Future research should prioritize expanding the research scale and incorporating more environmental factors to enhance the accuracy of experimental results.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/biology15010079/s1, Table S1: Biomass model table. Table S2: Carbon contents of species. Table S3: Data normality test results. Table S4: The natural breaks method (Jenks) classification table.

Author Contributions

L.W.: Conceptualization, Validation, Funding acquisition, Resources, and Writing—review and editing; L.T.: Methodology, Data curation, Formal analysis, and Writing—original draft; Y.W.: Supervision, Funding acquisition, and Resources; Z.Z.: Investigation, Supervision, and Project administration; Z.C.: Validation; S.T.: Investigation and Project administration; X.Z.: Software and Data curation; K.C.: Investigation and Visualization. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Lishui University, HXZKA2024106 and HXZKA2024107, Graduate Research and Innovation Programs YKY25011.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available in the Supplemental Text. The climate data (mean annual temperature and mean annual precipitation) in this study were accessed through the WorldClim database (http://www.worldclim.org/) (accessed on 6 April 2023).

Acknowledgments

We express our sincere gratitude to Weijun Jiang of the Lishui Ecological Environment Monitoring Center, Zhejiang Province, for his guidance in field monitoring. Special thanks are extended to Jianxin Zhang and Wenwen Pan of Lishui Polytechnic College for their substantial support during the monitoring campaign. We also acknowledge the contributions of Kuntai Chai, Liang Zhang, Tairong Xu, Chengpu Lu, Daomin Chen, Fengying Cai, Jian Xu, and other students from the Environmental Engineering program at Lishui University in conducting field plot surveys.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Zhengxuan Zhu was employed by the company Zhejiang Environmental Monitoring Engineering Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| CF | Coniferous forest | CVCW | Coefficient of variation in crown width |

| MF | Coniferous and broad-leaved mixed forest | PCA | Principal component analysis |

| BF | Broad-leaved forest | PC | Principal component |

| H | Shannon–Wiener index | LSD | Least significant difference |

| MAT | Mean annual temperature | SEM | Structural equation model |

| MAP | Mean annual precipitation | CFI | Comparative fit index |

| DBH | Diameter at breast height | SRMR | Standardized root mean square residual |

| TH | Tree height | RMSEA | Root mean square error of approximation |

| CW | Crown length | Env PC1 | Environmental PC1 |

| CV | Coefficient of variation | Env PC2 | Environmental PC2 |

| CVDBH | Coefficient of variation in diameter at breast height | R2 | Coefficient of determination |

| CVTH | Coefficient of variation in tree height |

References

- Lee, H.; Calvin, K.; Dasgupta, D.; Krinner, G.; Mukherji, A.; Thorne, P.; Trisos, C.; Romero, J.; Aldunce, P.; Barret, K. IPCC, 2023: Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report, Summary for Policymakers. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Core Writing Team, Lee, H., Romero, J., Eds.; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, B.M.; Balasubramanian, D. Carbon stocks of forests and tree plantations along an elevational gradient in the Western Ghats: Does plant diversity impact forest carbon stocks? Anthr. Sci. 2024, 3, 63–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Aguila, L.C.R.; Wu, D.; Lie, Z.; Xu, W.; Tang, X.; Liu, J. Carbon sequestration and storage capacity of Chinese fir at different stand ages. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 904, 166962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ming, A.; Liu, S.; Mo, H.; Cai, D.; Nong, Y.; Zeng, J.; Li, H.; Tao, Y. Comparison of carbon storage in pure and mixed stands of Castanopsis hystrix and Cunninghamia lanceolata in subtropical China. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2016, 36, 244–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; Peng, S.; Chen, Y.; Cao, Y. The effects of forest thinning on understory diversity in China: A meta-analysis. Land Degrad. Dev. 2020, 31, 1225–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Birdsey, R.A.; Fang, J.; Houghton, R.; Kauppi, P.E.; Kurz, W.A.; Phillips, O.L.; Shvidenko, A.; Lewis, S.L.; Canadell, J.G. A large and persistent carbon sink in the world’s forests. Science 2011, 333, 988–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, F.; Zhou, Y.; Bai, Y. The effect of mixed forest identity on soil carbon stocks in Pinus massoniana mixed forests. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 907, 167889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vähänen, T. FRA 2020 Remote Sensing Survey. FAO For. Pap. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Liu, S.; Yu, J.; Li, J.; Shangguan, Z.; Deng, L. Thinning increases forest ecosystem carbon stocks. For. Ecol. Manag. 2024, 555, 121702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keenan, R.J.; Reams, G.A.; Achard, F.; de Freitas, J.V.; Grainger, A.; Lindquist, E. Dynamics of global forest area: Results from the FAO Global Forest Resources Assessment 2015. For. Ecol. Manag. 2015, 352, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Li, T.; Yang, M.; Zhou, X.; Peng, C. The effects of environmental factors and plant diversity on forest carbon sequestration vary between eastern and western regions of China. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 437, 140371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grassi, G.; House, J.; Dentener, F.; Federici, S.; den Elzen, M.; Penman, J. The key role of forests in meeting climate targets requires science for credible mitigation. Nat. Clim. Change 2017, 7, 220–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zheng, J.; Gao, J.; He, X.; Liu, X.; Chen, Y.; Liu, J.; Li, C. Functional diversity explains ecosystem carbon storage in subtropical forests. Glob. Change Biol. 2025, 31, e70120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dar, J.A.; Rather, M.Y.; Subashree, K.; Sundarapandian, S.; Khan, M.L.L. Distribution patterns of tree, understorey, and detritus biomass in coniferous and broad-leaved forests of Western Himalaya, India. J. Sustain. For. 2017, 36, 787–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, F.; Xu, S.; Sayer, E.J.; Chen, W.; Du, Y.; Lu, X. Distinct storage mechanisms of soil organic carbon in coniferous forest and evergreen broadleaf forest in tropical China. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 295, 113142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Liu, Y.; Wu, G.; Lie, Z.; Sheng, H.; Aguila, L.C.R.; Khan, M.S.; Liu, X.; Zhou, S.; Wu, T. Mixed plantations do not necessarily provide higher ecosystem multifunctionality than monoculture plantations. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 914, 170156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, A.C.; Troeger, D.; Garcia, R.; Aguayo, M.; Barra, R.; Vogt, J. Assessing the impact of plantation forestry on plant biodiversity: A comparison of sites in Central Chile and Chilean Patagonia. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2017, 10, 159–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatimata, N.; Philippe, M.; Bienvenu, S.; Nicole, F. Exploring the effects of forest management on tree diversity, community composition, population structure and carbon stocks in sudanian domain of Senegal, West Africa. For. Ecol. Manag. 2024, 559, 121821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartoyo, A.P.P.; Khairunnisa, S.; Pamoengkas, P.; Solikhin, A.; Supriyanto, S.; Siregar, I.Z.; Prasetyo, L.B.; Istomo, I. Estimating carbon stocks of three traditional agroforestry systems and their relationships with tree diversity and stand density. Biodiversitas J. Biol. Divers. 2022, 23, 6137–6146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thom, D.; Keeton, W.S. Stand structure drives disparities in carbon storage in northern hardwood-conifer forests. For. Ecol. Manag. 2019, 442, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mensah, S.; du Toit, B.; Seifert, T. Diversity–biomass relationship across forest layers: Implications for niche complementarity and selection effects. Oecologia 2018, 187, 783–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Hernández, D.I.; Deane, D.C.; Wang, W.; Chen, Y.; Li, B.; Luo, W.; Chu, C. Direct effects of selection on aboveground biomass contrast with indirect structure-mediated effects of complementarity in a subtropical forest. Oecologia 2021, 196, 249–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grace, J.B.; Anderson, T.M.; Seabloom, E.W.; Elizabeth, T.B.; Peter, B.A.; Stanley, W.H.; Yann, H.; Helmut, H.; Eric, M.L.; Meelis, P.; et al. Integrative modelling reveals mechanisms linking productivity and plant species richness. Nature 2016, 529, 390–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.W.; Ji, B.Y.; Wang, Z.Y.; Zhu, C.H. Impact of subtropical forest landscape pattern on forest carbon density in Lishui City of Zhejiang Province. J. Zhejiang AF Univ. 2024, 41, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, M.; Chen, X.; Zhu, Z.; Chen, D.; Dong, S.; Li, B.; Ding, B.; Liu, Y. Community composition and structure of a 25-ha forest dynamics plot of subtropical forest in Baishanzu, Zhejiang Province. Biodivers. Sci. 2024, 32, 23294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Hao, B.; Jiang, Z. Variation of undergrowth species diversity on Camellia oleifera plantations in Guangxi. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2020, 40, 3507–3518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Zhang, D.; Wang, L.; Dong, L.; Liu, C.; Hou, D.; Chen, G.; Qiao, X.; Wang, Y.; Guo, K. Comparison of plant diversity-carbon storage relationships along altitudinal gradients in temperate forests and shrublands. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1120050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gogoi, R.R.; Adhikari, D.; Upadhaya, K.; Barik, S. Tree diversity and carbon stock in a subtropical broadleaved forest are greater than a subtropical pine forest occurring in similar elevation of Meghalaya, north-eastern India. Trop. Ecol. 2020, 61, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.-Y.; Li, Z.-T.; Xu, T.; Lou, A.-r. Leaf litter decomposition characteristics and controlling factors across two contrasting forest types. J. Plant Ecol. 2022, 15, 1285–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vesterdal, L.; Clarke, N.; Sigurdsson, B.D.; Gundersen, P. Do tree species influence soil carbon stocks in temperate and boreal forests? For. Ecol. Manag. 2013, 309, 4–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, S.; Gou, M.; Lei, P.; Liu, Y.; Chen, L.; Deng, X.; Zhao, Z.; Zeng, Y.; Hu, Y.; Peng, C. Plant functional trait diversity and structural diversity co-underpin ecosystem multifunctionality in subtropical forests. For. Ecosyst. 2023, 10, 100093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, F.; Zhao, X.; Luo, Y.; Tian, J.; Sun, Y.; Wang, H.; Wang, Q.; Zhu, J.; Yang, C.; He, H. Effects of thinning on canopy structure, forest productivity, and productivity stability in mixed conifer-broadleaf forest: Insights from a LiDAR survey. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 385, 125707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Ma, R.; Zhai, J.; Du, J.; Bai, J.; Zhang, W. Stand spatial structure is more important than species diversity in enhancing the carbon sink of fragile natural secondary forest. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 158, 111449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loreau, M.; Hector, A. Partitioning selection and complementarity in biodiversity experiments. Nature 2001, 412, 72–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeVries, T. The ocean carbon cycle. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2022, 47, 317–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Yan, E.-R.; Chen, H.Y.; Chang, S.X.; Zhao, Y.-T.; Yang, X.-D.; Xu, M.-S. Stand structural diversity rather than species diversity enhances aboveground carbon storage in secondary subtropical forests in Eastern China. Biogeosciences 2016, 13, 4627–4635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Fang, S.; Fang, X.; Jin, Y.; Kuang, Y.; Lin, F.; Liu, J.; Ma, J.; Nie, Y.; Ouyang, S. Forest understory vegetation study: Current status and future trends. For. Res. 2023, 3, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricotta, C.; Bacaro, G.; Maccherini, S.; Pavoine, S. Functional imbalance not functional evenness is the third component of community structure. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 140, 109035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, P.; Fernández-Martínez, M.; Van Meerbeek, K.; Yu, G.; Migliavacca, M.; He, N. The essential role of biodiversity in the key axes of ecosystem function. Glob. Change Biol. 2023, 29, 4569–4585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.Z.; Yue, C.; Hu, Y.F.; Ma, H. Spatial patterns of global-scale forest root-shoot ratio and their controlling factors. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 800, 149251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.