Simple Summary

Aspergillus molds play dual roles in industry and as opportunistic pathogens. Understanding and optimizing their functions requires precise genome editing. The CRISPR–Cas9 system, adapted from bacterial immunity, has become a key tool for targeted genetic modification in Aspergillus. It enables research into disease mechanisms, reduction in mycotoxin production, and the engineering of strains for industrial applications such as enzyme and metabolite production. This review outlines the principles of CRISPR–Cas9, highlights its applications in Aspergillus species, and discusses future challenges in developing safer, more efficient fungal strains.

Abstract

The genus Aspergillus comprises over 600 species of filamentous fungi. This genus significantly impacts human health, food fermentation, and industrial biotechnology. With the in-depth research and applications of Aspergillus species in many fields, the establishment of efficient gene editing technologies is crucial for functional genomics studies and cell factory development. The clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats and associated protein (CRISPR-Cas9) system, as a newly developed and powerful genome editing tool, has demonstrated exceptional potential for precise genetic modifications in various Aspergillus species. The continuous advancement of CRISPR-Cas9 technology has enabled precise gene editing and modification in both pathogenic and industrial Aspergillus strains, thereby driving innovations in pathogenicity attenuation, metabolic engineering, and functional genomics. Therefore, this review provides a concise overview of the CRISPR-Cas9 system, detailing its composition, working mechanism, and key functional features such as the role of the Cas9 protein and the protospacer adjacent motifs (PAMs). Subsequently, we focus on the transformative applications of CRISPR-Cas9 in Aspergillus species, discussing its pivotal roles in elucidating pathogenic mechanisms, disrupting mycotoxin biosynthesis, and employing metabolic engineering to enhance the production of industrial enzymes, organic acids, and valuable natural products. Finally, we discuss future challenges and promising opportunities for applying CRISPR-Cas9 technology to advance the industrial biotechnology of Aspergillus species.

1. Introduction

Filamentous fungi are indispensable to medicine, agriculture, and industry. Among them, the genus Aspergillus represents one of the most studied and economically important fungal groups. Species within this genus are commonly found in environments such as soil, seeds, grains, and decaying vegetation. To date, more than 600 Aspergillus species have been identified based on morphological, physiological, and phylogenetic characteristics (https://www.catalogueoflife.org/, accessed on 15 June 2025) [1,2]. Although these fungi function primarily as terrestrial decomposers and can serve as pathogens of plants and humans, they are also of indispensable value in agricultural, food, and pharmaceutical applications.

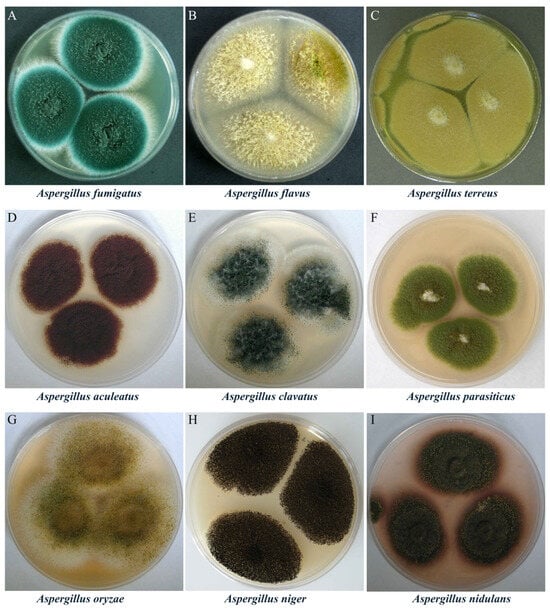

Notable Aspergillus species of industrial, environmental, and clinical relevance include Aspergillus fumigatus, Aspergillus flavus, Aspergillus terreus, Aspergillus nidulans, Aspergillus niger, Aspergillus aculeatus, and Aspergillus oryzae (Figure 1). This genus exhibits a dual nature in its relationship with humans. While many species are indispensable in food fermentation, enzyme production, and pharmaceutical manufacturing, others pose serious threats to human health due to their production of harmful mycotoxins, including aflatoxins [3,4,5]. These risks are primarily associated with pathogenic species such as A. flavus, A. fumigatus, and A. terreus (Figure 1A–C). For instance, A. fumigatus is a saprophytic, filamentous fungus that is crucial for carbon and nitrogen recycling in nature, yet it is also a causative agent of several pulmonary diseases in humans, birds, and other mammals [6]. A. flavus is the second most common cause of invasive aspergillosis (after A. fumigatus) and the leading cause of superficial Aspergillus infections. Moreover, it produces aflatoxin B1, one of the most potent hepatocarcinogenic natural compounds known, along with other toxic metabolites such as cyclopiazonic acid, ustiloxin B, and aflatrem [7]. These examples underscore the significant health risks posed by pathogenic Aspergillus species.

Figure 1.

Colony morphology of representative Aspergillus species. Images reproduced from https://fungi.myspecies.info/all-fungi/aspergillus, licensed under CC BY-NC; corresponding images are also available in Baniya, S. Aspergillus: Morphology, Clinical Features, and Lab Diagnosis. Mycology. Available online: https://microbeonline.com/aspergillus-morphology-clinical-features-and-lab-diagnosis/#Aspergillus_glaucus (accessed on 20 June 2025). The panels show the typical macroscopic appearance of each species: (A) Aspergillus fumigatus (blue-green, powdery); (B) Aspergillus flavus (yellow-green, velvety); (C) Aspergillus terreus (yellow-brown to cinnamon); (D) Aspergillus aculeatus (brown); (E) Aspergillus clavatus (center black with a white periphery and abundant mycelium); (F) Aspergillus parasiticus (largely green with a white central area); (G) Aspergillus oryzae (yellow-green with a white margin); (H) Aspergillus niger (black, powdery); (I) Aspergillus nidulans (earthy brown).

Conversely, many Aspergillus species (particularly A. oryzae, A. niger, and A. nidulans) (Figure 1G–I) serve as cornerstones of industrial biotechnology due to their exceptional metabolic versatility. Their efficient secretion systems and adaptability to low-cost substrates have enabled the engineering of these fungi for large-scale production of enzymes, organic acids, and secondary metabolites [8,9]. Owing to their robust metabolic and secretory capabilities, these species are also widely used to produce valuable natural products, as well as homologous and heterologous proteins [10,11]. For example, the Generally Regarded as Safe (GRAS) species A. oryzae produces diverse enzymes and beneficial secondary metabolites, enabling its extensive applications in food fermentation (e.g., soy sauce, miso) and industrial processes [12,13]. Its high secretory capacity for hydrolytic enzymes has also established A. oryzae as a key cell factory for the production of bioactive secondary metabolites and industrial enzyme preparations [14,15,16]. Similarly, A. niger is known for its ability to produce commercially important enzymes, organic acids, and secondary metabolites, particularly glucoamylase, a key enzyme for starch hydrolysis in the food and beverage industries [17]. A recent study reports that A. niger produces a β-galactosidase with high lactose hydrolysis efficiency (>90%) and shows potential for prebiotics synthesis, achieving a 7% conversion yield [18]. This species also produces other enzymes such as amylases, proteases, and cellulases, which have applications in the production of biofuels, animal feed, and other biotechnological processes. Notably, A. niger has been employed for over a century in the industrial production of organic acids and accounts for approximately 99% of the global citric acid supply (1.4 million tons annually) [19,20].

The need for efficient genetic tools is paramount to advance fundamental research and develop optimized Aspergillus cell factories for diverse applications [21]. Therefore, this review compares the strengths and limitations of conventional gene editing methods versus CRISPR-Cas9 technology in Aspergillus research. It first describes the working principles of CRISPR-Cas9 and its adaptation for use in Aspergillus. Subsequently, it provides a comprehensive overview of its applications, including the study of pathogenic mechanisms, the disruption of mycotoxin biosynthesis, and metabolic engineering for biomanufacturing. Finally, we discuss ongoing challenges and future directions for CRISPR-Cas9 technology in this field.

2. Genetic Editing Techniques in Aspergillus Research

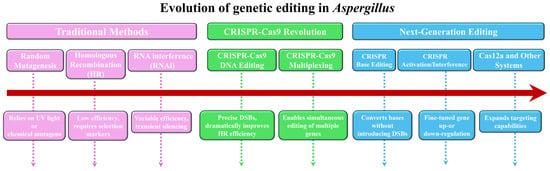

The genetic engineering of Aspergillus species has transitioned from classical random mutagenesis to highly precise and programmable genome editing. This paradigm shift has been instrumental in advancing fundamental research into fungal biology and pathogenicity, as well as facilitating applied biotechnological endeavors. The evolution of these techniques can be broadly categorized into three developmental stages, as outlined in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The three development stages of genetic editing techniques in Aspergillus.

2.1. Limitations of Traditional Genetic Tools in Aspergillus

Before the development of clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats/CRISPR-associated protein 9 (CRISPR-Cas9) technology, genetic manipulation in Aspergillus species largely depended on conventional techniques, such as random mutagenesis, RNA interference (RNAi), and homologous recombination (HR). However, these methods pose significant limitations that hinder efficient genetic engineering in fungi, including A. niger and A. oryzae. Random mutagenesis is the oldest gene editing technology, which employs ultraviolet light or chemical reagents (e.g., N-methyl-N’-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine (NTG)) to induce random mutations. As a non-targeted approach, it requires subsequent high-throughput screening to identify desired phenotypes, such as increased enzyme yield. While RNAi can silence gene expression at the transcriptional or post-transcriptional level in some Aspergilli, it is ineffective in other filamentous fungi due to incomplete or absent RNAi machinery [22]. For instance, species such as A. nidulans often exhibit inconsistent or weak RNAi responses due to the absence of core RNAi pathway elements or the presence of RNAi inhibition mechanisms. Even in filamentous fungi with functional RNAi machinery, technical hurdles such as inefficient delivery of double-stranded RNA (dsRNA), transient silencing effects, and off-target interactions often limit its utility in systematic genetic studies or industrial utilization. In contrast, HR-based gene targeting has long served as the standard method for disruption or deletion in Aspergillus species. However, this approach is hampered by inherently low efficiency due to poor HR rates and is technically demanding in this genus [22]. Consequently, deleting large gene clusters (e.g., aflatoxin biosynthetic genes in A. flavus) requires laborious screening and multiple selection markers [23], and even successful deletions risk leaving residual “cryptic” pathways active, potentially leading to the production of unexpected toxins.

Although HR efficiency can be improved by using strains deficient in non-homologous end joining (NHEJ), the multinucleate nature of Aspergillus conidia complicates HR-mediated targeting, as isolating homozygous transformants demands extensive screening [24,25]. In addition, Aspergillus genomes harbor a large number of biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) for secondary metabolites, yet traditional methods lack the capability to systematically activate, characterize, or manipulate such often-silent clusters. Thus, despite their foundational role, traditional genetic tools are hampered by substantial limitations in efficiency, precision, and applicability. These constraints pose a major bottleneck for the development of engineered strains for biocontrol or industrial biotechnology.

2.2. Efficient Editing of CRISPR-Cas9 Technology in Aspergillus

As a powerful and widely adopted genome editing tool, CRISPR-Cas9 technology has been adapted for filamentous fungi through modifications to the Cas protein and single-guide RNA (sgRNA), establishing a versatile system that has significantly promoted genetic manipulation in these organisms [26,27]. The CRISPR-Cas9 system was first established and used to disrupt the ura5 gene in the filamentous fungus Trichoderma reesei [28]. To date, CRISPR-Cas9 systems have been successfully applied to over 40 filamentous fungal species, including Trichoderma, Monascus [24,25], Penicillium [29], Neurospora [30,31], Fusarium [32] and Aspergillus [27,33]. By integrating CRISPR with viral vectors or NHEJ-deficient strains, marker-free edits and high-precision point mutations are achieved, which partially solves the HR challenge caused by low efficiency in filamentous fungi.

The CRISPR-Cas9 system has proven to be a highly effective gene editing tool across diverse Aspergillus species. Initial reports as early as 2015 demonstrated its efficacy in A. nidulans, A. niger, A. aculeatus, and Aspergillus brasiliensis, where editing efficiency for the yA gene (which encodes a key enzyme for green spore pigment biosynthesis) reached up to 90% [27,34]. Since then, further optimization has led to even higher efficiencies. For instance, an optimized CRISPR-Cas9 method utilizing in vitro-assembled Cas9-gRNA ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes was developed in A. niger, achieving 100% targeting efficiency in single-locus genome editing [35,36]. In addition, Chang developed a high-efficiency CRISPR-Cas9 system yielding targeting frequencies exceeding 95% in A. flavus, which also gave satisfactory gene-targeting efficiencies (>90%) in A. nidulans, A. fumigatus, A. terreus, and A. niger [37]. In A. oryzae, the CRISPR-Cas9 system enables highly efficient genome editing. When combined with selection markers (e.g., based on color or resistance), 100% of the resulting transformants can be obtained with the desired single- or double-gene edits [38]. Meanwhile, Yuan et al. employed two gRNAs for targeting in CRISPR-Cas9 systems and achieved up to 100% editing efficiency for single gene editing in A. niger [33]. By targeting a secondary metabolite gene cluster, they also demonstrated that large chromosomal fragments over 100 kb can be efficiently and specifically deleted by a multi-gRNA genome editing system utilizing Cas9 in A. niger [33]. Furthermore, in A. oryzae, the CRISPR-Cas9 system combined with microhomology-mediated end joining (MMEJ) and single-strand annealing (SSA) repair systems enabled streamlined generation of targeted knock-in transformants, significantly simplifying workflows compared to traditional homology-dependent methods [39]. Collectively, these studies underscore the remarkable efficacy and versatility of the CRISPR-Cas9 system as a genetic engineering tool across the Aspergillus genus.

3. Working Mechanism of CRISPR-Cas9 System

3.1. Type of CRISPR-Cas System

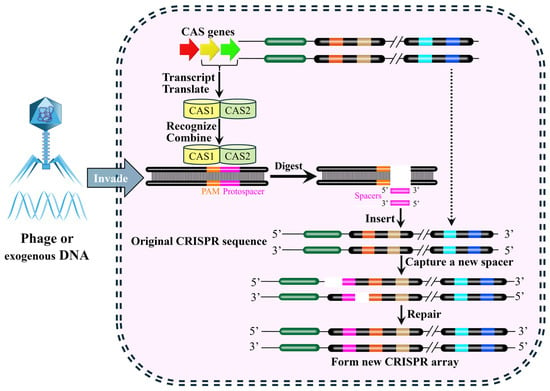

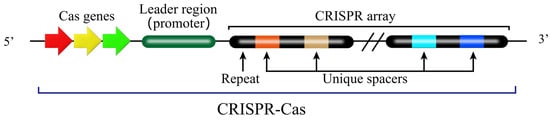

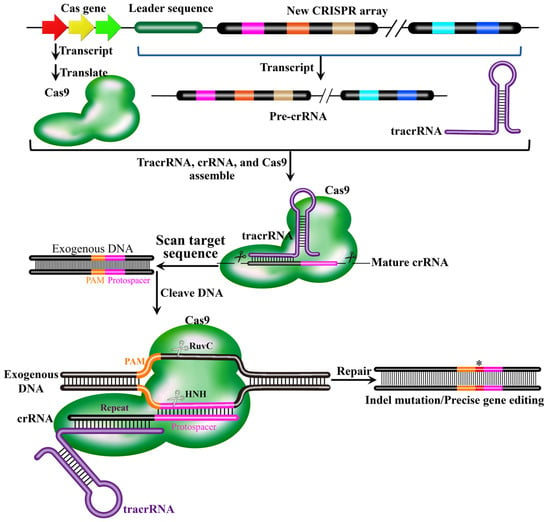

The CRISPR-Cas system functions as an adaptive immune system in numerous bacteria and archaea, providing defense against bacteriophage infection and plasmid transfer [40]. The CRISPR-Cas system comprises two key components (Figure 3) [40]. One is the Cas (CRISPR-associated) protein complex, which is responsible for the acquisition of new spacer sequences from invading DNA and for the cleavage of foreign genetic material. The other is the CRISPR array, which consists of short, conserved DNA repeats interspersed by variable spacer sequences that are derived from previous invaders. These components work together in a multi-stage immune response. The first stage is adaptation. During the adaptation phase, short fragments of exogenous DNA derived from invading genetic elements (e.g., phage or plasmids) are integrated into the CRISPR repeat-spacer array within the host chromosome as new spacers, which provides a genetic memory of previous infection that confers immunity against future invasions by the same invader (Figure 4) [41,42,43].

Figure 3.

Two key components in the general CRISPR-Cas system locus. The base composition and length of repeat sequences are highly conserved and basically unchanged within the same bacterial species, but they may show slight variations between different bacterial species. The spacer sequences function to anchor target exogenous genes, and thus display significant diversity in their base composition, as these sequences are derived from distinct exogenous gene fragments. Additionally, there is usually leader sequence rich in A-T bases in the upstream of the CRISPR array, which harbors a promoter and is responsible for initiating the transcription of both the repeat and spacer sequences. The schematic employs the following visual code, as indicated within the figure: the leader region (dark green), repeats (black), unique spacers (gold, light blue, dark blue, and orange), and Cas genes (red, yellow, and green arrows). The process is shown: foreign DNA invasion (blue arrow), with a dashed line outlining the overall sequence. Solid black arrows denote key steps, including the digestion of a protospacer, excising a new spacer fragment (pink) for insertion into the CRISPR array. This integration is detailed in the inset.

Figure 4.

Acquisition of new Spacer sequence in CRISPR-Cas system. When the phages or exogenous genes invade the bacterial, the protospacer in the genome will be recognized and cleaved by Cas-associated proteins in CRISPR-Cas system and inserted into middle of the leader sequence and an adjacent repeat to form a new spacer. This process establishes adaptive immunity, enabling the CRISPR-Cas system to recognize and cleave the same exogenous genome during subsequent invasions. The color scheme for molecular components (leader in dark green, repeats in black, spacers in gold/blue/orange, Cas proteins as colored arrows) follows the same convention as defined in Figure 3.

The molecular mechanism described above is encoded by a highly diverse set of genetic systems. The ongoing co-evolution of prokaryotes and the viruses underlies the remarkable diversity of CRISPR-Cas systems [44]. CRISPR-Cas systems are categorized into two main classes (Class 1 and Class 2) based on the structure of their effector complexes [45]. These systems are found in approximately 90% of archaea and 50% of bacteria, with Class 1 systems being the most common, representing nearly 90% of all identified CRISPR-Cas systems [46]. Structurally, Class 1 and Class 2 systems are defined by their effector modules: Class 1 systems (including Types I, III, and IV) utilize multi-protein effector complexes to target and cleave nucleic acids, whereas Class 2 systems (including Types II, V, and VI) employ a single large effector protein [44,45]. The adaptation step, which integrates viral sequences into the host genome, is mediated by the highly conserved Cas1 and Cas2 proteins across nearly all types (except Type IV), underscoring a core conserved function. In contrast, the effector modules responsible for target recognition and cleavage exhibit considerable diversity across the six major types (I-VI) of CRISPR-Cas systems, whose key features are summarized in Table 1 [45,47,48,49,50,51].

Table 1.

The key features of six CRISPR-Cas systems.

To date, most researchers have favored Class 2 CRISPR-Cas systems due to their reliance on a single effector protein. Among these, the type II CRISPR-Cas9 system is the most extensively studied and widely applied in genome editing. It utilizes a single DNA endonuclease (Cas9) to recognize double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) and cleave target DNA sequences [45]. This simplicity and programmability have made CRISPR-Cas9 a revolutionary tool, leading to its recognition as the predominant third-generation genome editing technology, succeeding earlier protein-engineering-based platforms such as zinc-finger nucleases (ZFNs) and transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALENs) [52]. Consequently, it has now largely superseded these more complex methods for a wide range of applications.

3.2. Composition and Working Mechanism of CRISPR-Cas9 System

The functional core of the CRISPR-Cas9 system comprises two elements: the Cas9 endonuclease and a sgRNA. The Cas9 protein, which consists of two endonuclease domains (HNH and RuvC-like) and two RNA-binding domains (REC and PI), is responsible for recognizing and cleaving the target DNA to generate a double-strand break (DSB) immediately upstream of a protospacer adjacent motif (PAM, typically NGG) [53]. The sgRNA is an engineered molecule that mimics the natural tracrRNA:crRNA duplex. In nature, the CRISPR array is transcribed to give rise to a long precursor CRISPR RNA (pre-crRNA), which is subsequently processed into short, mature crRNAs [47]. The 5’ end mature crRNA contains one spacer sequence derived from the invading exogenous DNA, while the 3’ end contains partial repeat sequences flanking the spacer which is critical for stability and Cas protein binding. Trans-activating crRNA (tracrRNA) is a critical non-coding RNA component of type II CRISPR-Cas9 system, transcribed from a region adjacent to the CRISPR array and Cas9 gene in bacterial genomes. The tracrRNA contains a complementary region that base-pairs with the repeat sequence in the pre-crRNA to form a sgRNA [54]. The sgRNA (or the natural tracrRNA: crRNA complex) guides the Cas9 protein to the target DNA via sequence complementarity. Cas9 then cleaves both DNA strands if the target is adjacent to a compatible PAM, thereby generating a DSB [53,55]. During the cellular process of repairing the DSBs, cellular repair mechanisms trigger small base deletions or insertions at the target site through either NHEJ or high-fidelity homology-directed repair (HDR) pathways, generating mutations of frame-shifted nonsense proteins and loss of gene function [56]. The working mechanism of the CRISPR-Cas9 system described is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

The promoter in the leader sequence initiates the transcription of the downstream CRISPR array. This transcription process is continuous, resulting in a long RNA chain that contains all repeats and spacers in the CRISPR array. This long-chain RNA is called the precursor transcript (Pre-crRNA). Trans-activating crRNA (tracrRNA) is transcribed from a region adjacent to the CRISPR array and Cas9 gene in bacterial genomes. crRNA is complementary to non-coding trans-activating CRISPR RNA (tracrRNA) and then forms a complex with Cas9 protein for target DNA cleavage to generate DSBs. Indel mutation or precise gene editing are achieved during the cellular process of repairing the DSBs. In the schematic, molecular components are color-coded: the Cas9 protein (green irregular shape), tracrRNA (purple ring), pre-crRNA (derive from the new CRISPR array), and invading DNA (black strand with orange PAM and pink protospacer sequences). The red asterisk (*) specifically marks the site of indel mutation generated during the repair of the Cas9-induced double-strand break, located between the PAM and the protospacer.

3.3. Functional Features of Cas9 and PAM in CRISPR-Cas9 System

The practical application of CRISPR-Cas9 hinges on two key design elements: the guide RNA and the protospacer adjacent motif (PAM). Regarding the guide RNA, scientists often use engineered sgRNA instead of separate crRNA and tracrRNA. The crRNA and tracrRNA are fused into sgRNA in vitro, simplifying delivery while retaining tracrRNA’s functional elements (e.g., Cas9 binding and structural stabilization). But in the natural system, crRNA and tracrRNA are separate. TracrRNA is required for Cas9 but not necessarily for other CRISPR-associated proteins (e.g., Cas12 or Cas13). Regarding the PAM, the recognition and acquisition of spacers by Cas9 proteins depend on the PAM sequence located downstream of the target DNA. The PAM is a short, conserved sequence (2-6 bp) located adjacent to the 3’ end of the crRNA-targeted DNA sequence (protospacer) on the invading DNA, which plays an essential role in target DNA selection and cleavage in the CRISPR-Cas9 systems [57]. Additionally, this PAM plays a critical role in the in vitro design of CRISPR-Cas9 system. Different Cas9 proteins recognize distinct PAM sequences, influencing their utility in fungal genome editing.

Despite being the most widely used effector protein due to its high efficiency in generating DSBs [58,59], the Cas9 from Streptococcus pyogenes (SpCas9) has three principal limitations that constrain its application: First, its PAM is NGG, which requires the target sequence to contain two consecutive guanines (GG) for DSB formation, thereby restricting its targeting scope in AT-rich genomic regions. Second, the relatively large size of SpCas9 (1368 amino acids) complicates its delivery via viral vectors with limited packaging capacity. Third, SpCas9 is prone to off-target effects, leading to DSBs at unintended genomic loci. To address these challenges, several engineered strategies have been developed. For instance, high-fidelity variants such as SpCas9-HF have been created through coding sequence modifications to reduce off-target effects [60]. In addition, to overcome the PAM constraint, SpCas9 has been engineered to recognize alternative PAMs. The resulting variants are often named by abbreviated codes (e.g., VQR, EQR, VRER) that reflect the key amino acid substitutions responsible for their altered PAM specificity [61]. Another engineered derivative of SpCas9 is the nickase Cas9 (nCas9), created by inactivating one of the two nuclease domains in SpCas9. This variant induces single-strand breaks and, when used in combination with two gRNAs, can generate targeted deletions or other genomic modifications while reducing off-target effects [62,63]. To address the large size of SpCas9, Cas9 orthologs from other organisms have been utilized. For instance, Staphylococcus aureus Cas9 (SaCas9) is notably smaller and recognizes a different PAM sequence [64,65]. A summary of commonly used Cas9 proteins and their respective PAM sequences is provided in Table 2 [58,59,64,65,66,67,68,69].

Table 2.

The structural characteristics of different PAM sequences in the CRISPR-Cas9 system.

4. Key Applications of CRISPR-Cas9 Technology in Aspergillus

4.1. Elucidating Pathogenicity and Drug Resistance

Certain Aspergillus species, though generally harmless to healthy individuals, can pose significant health risks to immunocompromised hosts. As the most prevalent airborne fungal pathogen, invasive aspergillosis caused by A. fumigatus primarily occurs in immunocompromised patients and has dramatically increased since the early 2000s [70]. However, research into its pathogenic mechanisms has long been hindered by its inherently low efficiency of HR, which favors the NHEJ pathway. Prior to the advent of CRISPR-Cas9, researchers relied on labor-intensive strategies to improve HR or work within its constraints, such as the use of recyclable selectable markers or the development of dominant bidirectional selection systems (e.g., Krappmann et al., 2005) [71]. The emergence of CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing has revolutionized this field. By providing a powerful and precise tool to directly overcome this barrier, it now enables detailed functional studies of virulence factors in A. fumigatus.

CRISPR-Cas9 has been used to identify genes involved in stress response, drug resistance, and host immune evasion, providing insights into developing new antifungal therapies [72]. Fuller et al. first demonstrated the feasibility and high efficiency (25–53%) of CRISPR-Cas9-mediated gene editing in A. fumigatus by targeting disruption of pksP, a polyketide synthase gene essential for melanin biosynthesis [73]. Zhang et al. subsequently developed a highly efficient CRISPR-Cas9 system that leverages the MMEJ pathway, using a 35 bp microhomology arm to achieve precise in-frame integrations with 95–100% accuracy [74]. Utilizing this MMEJ-mediated CRISPR-Cas9 system, they achieved precise integration of an exogenous GFP tag and performed editing at multiple genomic loci, including the endogenous pksP and cnaA genes. A major breakthrough in A. fumigatus involved the combination of CRISPR-Cas9 with endogenous counter-selectable markers (e.g., fcyB, cntA, azgA). This approach allows for efficient, marker-free allelic replacement and facilitates the simultaneous integration of multiple constructs (e.g., reporter and resistance genes) in a single transformation, vastly improving the throughput of complex genetic studies [75]. Collectively, these technological breakthroughs have not only overcome historical limitations in fungal genetic engineering but also established a solid framework for systematic study of virulence factors, antifungal resistance, and secondary metabolite pathways in A. fumigatus.

The CRISPR-Cas9 technology has been used to elucidate antifungal resistance mechanisms in Aspergillus [76]. For example, in A. fumigatus, CRISPR-Cas9 has been instrumental in linking specific mutations to altered drug-target interactions. Triazole antifungals, such as isavuconazole (FDA-approved in 2015 for invasive aspergillosis and mucormycosis), remain frontline therapies. Their target, the enzyme encoded by the Cyp51A gene, is a lanosterol 14α-demethylase essential for ergosterol biosynthesis, a key component of the fungal cell membrane [77,78]. Recent studies leveraging CRISPR-Cas9 have elucidated the mechanistic roles of Cyp51A, Cyp51B, and Hmg1 (hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA reductase) in resistance. For instance, RNP-based CRISPR-Cas9 systems enable precise introduction of resistance-conferring mutations in these genes, revealing their synergistic contributions to triazole tolerance in A. fumigatus [79,80]. Furthermore, an in vitro-assembled CRISPR-Cas9 system streamlined the integration of mutations in cyp51A, cyp51B and hmg1 in A. fumigatus, providing robust models to dissect resistance evolution [81].

Beyond elucidating established resistance mechanisms, CRISPR-Cas9 has also accelerated de novo antifungal drug discovery through functional genomics. A CRISPR-Cas9 RNP screen targeting protein kinase genes in A. fumigatus identified several kinases critical for fungal survival under echinocandin stress [82]. Importantly, these kinases are also required for both hyphal septation and the ability of A. fumigatus to invade lung tissue. The versatility of CRISPR-Cas9 extends beyond resistance studies. With the potential to seamlessly introduce genes conferring resistance to additional existing and novel antifungals, toxic metals, and environmental stressors, the CRISPR-Cas9 system has become an indispensable tool to explore the mechanisms of fungal adaptation. Such advances not only enhance our understanding of A. fumigatus biology, but also provide strategies for avoiding drug resistance and designing the next generation of antifungal drugs.

4.2. Disruption of Toxin Biosynthesis in Aspergillus

CRISPR-Cas9 technology has revolutionized genetic engineering in fungi, offering unprecedented precision for developing biocontrol solutions against toxigenic Aspergillus species. A. flavus produces hepatocarcinogenic aflatoxin B1, recognized as one of the most potent hepatocarcinogens among natural compounds. A. flavus can grow in various food crops, and preharvest aflatoxin contamination of crops is a complex problem. The most cost-effective approach to control preharvest aflatoxin contamination of crops is biological control, which employs non-aflatoxigenic A. flavus strains with defective aflatoxin gene clusters to outcompete field toxigenic A. flavus populations [83]. Beyond aflatoxin B1, A. flavus produces additional toxic secondary metabolites, including cyclopiazonic acid, ustiloxin B, and aflatrem. This multiplicity of toxins necessitates comprehensive genetic modifications to ensure biocontrol strain safety. Genome editing can be utilized to obtain non-aflatoxigenic A. flavus strains, typically by generating loss-of-function point mutations in key biosynthetic genes (e.g., pksA, dmtA) or by deleting segments of the aflatoxin biosynthetic gene cluster [84].A significant study by the United States Department of Agriculture utilized a dual CRISPR-Cas9 system to create large chromosomal segment deletions (201–301 kb) encompassing the gene clusters for aflatoxin, cyclopiazonic acid, and ustiloxin B in A. flavus [23]. This strategy achieved high deletion efficiency (66.6% to 85.6%) using short 60-nucleotide donor DNA and a pigment-based screening system, demonstrating an effective method for generating biocontrol strains devoid of multiple harmful metabolites.

This strategy of multi-toxin cluster deletion has also been applied to A. oryzae. Wild-type strains were engineered to remove gene clusters for aflatoxin, cyclopiazonic acid, 3-nitropropionic acid, and penicillin G. This was achieved through multiple rounds of gene editing, resulting in strains devoid of these mycotoxins even under stress conditions [85]. Furthermore, the versatility of CRISPR-Cas9 for pathway manipulation is underscored by its application in A. fumigatus. Although the direct disruption of the gliotoxin pathway has not been extensively reported, CRISPR-Cas9 has been successfully applied in A. fumigatus to reconstitute biosynthetic pathways for metabolites such as chetomin [77]. This successful reconstitution demonstrates the platform’s general capability for precise pathway manipulation, paving the way for its application in the targeted disruption of virulence-associated pathways such as gliotoxin biosynthesis.

4.3. Metabolic Engineering for Bioproduction

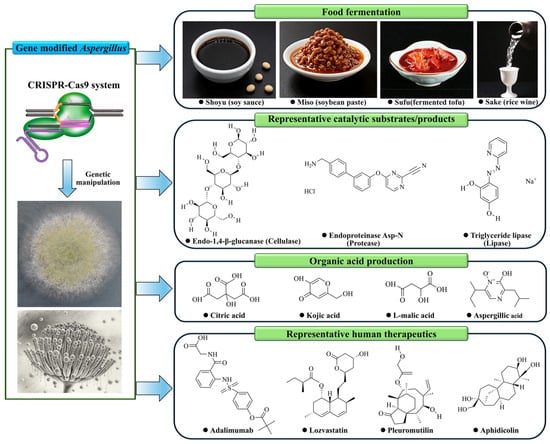

The fungal genus Aspergillus, particularly species like A. oryzae and A. niger, has long been used for food fermentation and valued in biotechnology as efficient cell factories for the production of enzymes, organic acids, and secondary metabolites [19,86,87]. However, the advent of the CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing system, as a multifunctional technology, has revolutionized metabolic engineering in these organisms by enabling precise, multiplexed genetic manipulations that were previously challenging or impossible. Thereby, this has dramatically accelerated the optimization of industrial Aspergillus strains for enhanced bioproduction [24]. The broad utility of this technology is visualized in Figure 6, where representative molecules exemplify key application areas enabled by CRISPR-Cas9 engineering in Aspergillus: traditional food fermentation, industrial enzyme production, organic acid biosynthesis, and the burgeoning field of pharmaceutical development.

Figure 6.

CRISPR-Cas9 engineering expands the application scope of Aspergillus species. This schematic uses representative molecular structures to visualize key product categories that are now accessible or being explored through advanced metabolic engineering of Aspergillus species. The molecules are grouped into four major application sectors: traditional fermentation and food, industrial enzymes (exemplified by endo-1,4-β-glucanase, endoproteinase Asp-N, and triacylglycerol lipase), organic acids (e.g., citric acid), and pharmaceuticals (including biologic drugs like the monoclonal antibody adalimumab, and small-molecule drugs such as the statin lovastatin, the antibiotic pleuromutilin, and the DNA synthesis inhibitor aphidicolin). This compilation conceptualizes how precision genome editing can reprogram these fungi into versatile platforms for diverse biomanufacturing goals.

4.3.1. Enhancing Industrial Enzyme and Protein Production

A major application of CRISPR-Cas9 in Aspergillus is the construction of tailored cell factories for efficient protein and enzyme production, extensively engineering these fungi into high-yielding platforms. A foundational strategy involves knocking out genes encoding native secreted proteases to prevent the degradation of target proteins and thereby increase yields. Beyond gene disruption, CRISPR-Cas9 technology is particularly powerful for precise genomic integration. For instance, in A. oryzae, CRISPR-Cas9 has been used to disrupt lipase genes of AoTgla and AoTglb to alter lipid metabolism and to integrate multiple heterologous lipase genes into different genetic loci in A. oryzae [38,88]. CRISPR-Cas9 was also used to reprogram the transcriptional regulation of the acv gene, which encodes ACV synthetase (ACVS), to develop a platform for producing bioactive oligopeptides (NRPs) in A. oryzae [89]. In A. niger, significant advancements were achieved by developing an improved CRISPR-Cas9 homology-directed repair (CRISPR-HDR) system, which enabled the precise integration of a glucose oxidase gene (GoxC) into the amyA and glaA loci, resulting in a fourfold increase in enzyme activity [90]. Based on this CRISPR-HDR system, CRISPR-based multiplex integration toolkit was constructed in A. niger, achieving 100% editing efficiency when simultaneously integrating the xylanase gene xynA into three target loci (the β-glucosidase gene bgl, the amylase gene amyA, and the acid amylase gene ammA) [91]. This multiple integration toolkit also successfully enhanced the expression of endogenous pectinase pelA and Candida antarctica lipase B (CALB) [91]. Furthermore, an engineered A. niger strain with high lipase activity was successfully isolated by employing the CRISPR-Cas9 system to integrate CALB into high-expression loci of glaA and amyA, while simultaneously knocking out the host’s highly expressed protein genes of pepA, aglU, and bglA [92]. This multi-faceted engineering approach yielded an A. niger strain producing 10.21 mg/mL of CALB protein with activity reaching 17.84 U/mL. The application extends to other species, such as A. fumigatus, where CRISPR-Cas9-mediated targeted knock-in of the cellulase gene eglA from A. niger led to a 40% increase in enhanced endoglucanase activity, highlighting its potential in enzyme production [93]. This is the first report of heterologous cellulase production in filamentous fungi using CRISPR-Cas9 technology.

Beyond protein expression, the CRISPR-Cas9 system was used to delete the Aooch1 gene, which encodes a key enzyme in the hyper-mannosylation process in A. oryzae, in order to investigate the binding ability of antibody for FcγRIIIa [12]. In addition, CRISPR-Cas9 technology was employed to examine the association between protein/organic acid fermentation and macromorphology in A. niger by placing the titratable Tet-on expression system upstream of ageB, secG, and geaB, which led to improved titres [94]. Together, this study showed that the integration of CRISPR-Cas9 with the Tet-on expression system provides a novel strategy to enhance protein yield. Using a CRISPR-Cas9-mediated multicopy integration strategy, the trehalases TreM and MthT, which catalyze the hydrolysis of the non-reducing disaccharide trehalose, were heterologously expressed in A. niger, reaching a yield of 1943.06 U/mL and 1698.83 U/mL, respectively [95,96]. Furthermore, CRISPR-Cas9 has been used to modify protein secretion pathways to address productivity barriers in A. nidulans, including post-translational modifications such as protein N-glycosylation [97]. In that study, a double knockout of the algC and algI genes via CRISPR-Cas9 altered the glycosylation pattern of a recombinant β-xylosidase (BxlB), resulting in a 1.5-fold improvement in secretion and an increase in specific activity. These collective successes underscore the transformative potential of CRISPR-Cas9 in optimizing Aspergillus as a cell factory.

4.3.2. Engineering for Organic Acid Production

The precision of CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing has been pivotal in engineering Aspergillus species for enhanced organic acid production. This section reviews key advances in this area, including the development of metabolic engineering strategies for citric acid and the application of CRISPR-Cas9 systems for genome editing in A. niger. In particular, A. niger dominates the $2.8 billion/year citric acid market via submerged fermentation [20]. A significant breakthrough was the development of a highly efficient CRISPR-Cas9 system for A. niger by researchers at the Tianjin Institute of Industrial Biotechnology [98]. They addressed the challenge of expressing sgRNA in fungi by using the 5S rRNA gene as a promoter to drive sgRNA expression. This system simplifies genetic manipulations, allowing for gene knock-ins with short 40 bp homology arms and even large DNA deletions up to 48 kb, thereby providing a robust tool for extensive metabolic engineering. As the key industrial workhorse for organic acids, A. niger has been a primary target for CRISPR-Cas9-enabled precise gene knockouts, promoter engineering, and multi-gene integrations to optimize metabolic pathways. For example, it allows for rational strain improvement by precisely eliminating genes responsible for major byproducts and gluconic acid, thereby channeling more carbon flux towards citrate. For instance, overexpressing key glycolytic enzymes like phosphofructokinase (PfkA) and pyruvate kinase (PkiA) can increase glycolytic flux, while strategies like knocking out the citrate synthase gene (gltA) can redirect carbon flow away from byproducts and towards citric acid products [99]. A 2025 study used CRISPR-Cas9-mediated Tet-on inducible promoter replacement to titrate the expression of flbE, a key developmental regulator gene, in two industrial A. niger strains. The researchers discovered that repressing flbE in a citric acid-producing strain (D353.8) resulted in a significantly increased citric acid production by 22.7% [100].

Beyond citric acid, the platform is being applied to other valuable organic acids. For example, CRISPR-Cas9 together with sgRNA synthesized in vitro was used to successfully delete multiple genes involved in galactaric acid catabolism for the efficient production of galactaric acid in A. niger [101]. This study demonstrated a successful early application of CRISPR-Cas9 for galactaric acid production in A. niger. Subsequently, Kuivanen et al. used CRISPR-Cas9 system to effectively delete the gluD gene of D-glucuronic acid catabolism in A. niger, resulting in the accumulation of 2-keto-L-gulonate in the liquid cultivation [102]. Furthermore, an optimized CRISPR-Cas9 method utilizing in vitro-assembled Cas9-gRNA RNP complexes was developed, achieving 100% targeting efficiency in single-locus genome editing in A. niger [35,36]. This optimized CRISPR-Cas9 method has also been proven to be suitable for multiplexed genome editing with two or three genomic targets in metabolic engineering application, resulting in improved production of galactarate in A. niger [35]. In another study, an RNP-based CRISPR-Cas9 system has been successfully used to disrupt two genes involved in the production of gluconic acid and oxalic acid in A. niger, which significantly improved the succinic acid production [103].

In addition, a convenient and efficient double-gene editing system based on CRISPR-Cas9 and Cre-loxP was developed in A. nidulans to investigate its potential as a host for L-malic acid synthesis [104]. Using this developed gene editing system, five genes (encoding Pyc, pyruvate carboxylase; OahA, oxaloacetate acetylhydrolase; MdhC, malate dehydrogenase; DctA, C4-dicarboxylic acid transporter; and CexA, citric acid transporter) were successfully deleted or overexpressed. These modifications increased the L-malic acid production by approximately 9.6-fold compared with the original unedited strain. Additionally, Zhang et al. employed CRISPR-Cas9 system to replace the fumA promoter with a doxycycline-induced promoter Tet (Tet-on/off system) in a high L-malic acid-producing strain RG0095, indicating that fumA is an essential gene and contributes to the accumulation of L-malic acid in A. niger [105].

Furthermore, CRISPR-Cas9 technology was also used to elucidate and enhance kojic acid biosynthesis in A. oryzae by targeting various genes involved in its regulatory and metabolic pathways. For instance, CRISPR-Cas9-mediated disruption of the glycerol dehydrogenase gene AoGld3 revealed that its deletion reduces kojic acid production, and downregulates the expression of the biosynthetic genes kojA and kojR [106]. In another study, Li et al. employed an AMA1-based CRISPR-Cas9 system to generate single mutants of kojA, kojR, and kojT, thereby establishing a platform for multiplex gene editing in A. oryzae [107]. Similarly, the CRISPR-Cas9 system was utilized to delete Aokap5 and AoKap7 in A. oryzae. AoKap7 is a C2H2-type zinc-finger protein involved in growth and kojic acid production. Their deletion resulted in reduced kojic acid production and downregulated expression of kojic acid biosynthesis genes kojA [38,108]. More recently, CRISPR-mediated knockout of the Aokap9 gene unveiled a novel regulatory pathway (AoZFA-LaeA-KojR) for kojic acid synthesis, leading to a significant increase in kojic acid production [109]. Collectively, these findings provide a deeper understanding of the regulatory network controlling kojic acid biosynthesis.

4.3.3. Reprogramming Natural Product Biosynthetic Pathways

The CRISPR-Cas9 system further demonstrates its versatility in reprogramming natural product biosynthetic pathways in diverse Aspergillus species, enabling both targeted pathway engineering and activation of silent gene clusters. Specifically, CRISPR-Cas9 has proven valuable for reviving silent biosynthetic pathways. Weber et al. successfully restored the biosynthesis of trypacidin in a nonproducing A. fumigatus strain by using the CRISPR-Cas9 system to functionally reconstitute tynC, a polyketide synthase-encoding gene in the trypacidin pathway [110]. In A. terreus, optimized CRISPR-Cas9 protocols have enabled precise editing (knockout and knock-in) of key genes (lovB, lovF, lovR) in the lovastatin biosynthesis pathway, showcasing its power for metabolic engineering in industrial settings [111]. Furthermore, to reduce the cumbersome hydrolysis of lovastatin to produce Monacolin J in A. terreus, key genes (lovB, lovC, lovG, and lovA) involved in the Monacolin J biosynthetic pathway were heterologously integrated into the A. niger genome with strong promoters and suitable integration sites using CRISPR-Cas9 homology-directed recombination, and the yield of Monacolin J reached 92.90 mg/L [112]. In recent studies, CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing was used to engineer A. oryzae for heterologous production of terpenoids. Through 13 targeted genetic modifications, researchers achieved enhanced production of pleuromutilin, aphidicolin, and ophiobolin C compared to the unmodified A. oryzae strain [113].

CRISPR-Cas9-mediated transcriptional activation has also been used to accelerate the discovery of genome-guided bioactive natural products in A. nidulans. For instance, using the established CRISPR strategy, increased production of the compound microperfuranone was achieved by targeting the native nonribosomal peptide synthetase-like (NRPS-like) gene micA in A. nidulans [114]. In a more recent advancement, a CRISPR-Cas9 cytidine base editor (CBE) combined with a multiplexed sgRNA library enabled the simultaneous inactivation of 46 natural product biosynthetic gene clusters in A. nidulans, which reduced competing byproduct synthesis and increased the yield of the antifungal compound echinocandin B by 2.3-fold [115].

The versatility of CRISPR-Cas9 extends to precise transcriptional activation using a catalytically dead Cas9 (dCas9). This was demonstrated in A. niger, where dCas9 fused to a histone acetyltransferase (p300) was targeted to the promoter of a specific secondary metabolite gene. This recruitment led to substantially increased gene expression and a dramatic 12-fold enhancement in fumonisin B2 production [116,117]. Additionally, CRISPR-Cas9 technology has also been applied to A. oryzae to elevate intracellular levels of nutraceuticals such as ergothioneine and flavor/color molecules like heme in the edible biomass. Using a modular toolkit that incorporated CRISPR-Cas9, researchers engineered the fungus to express an optimized heme biosynthesis pathway, resulting in a 4-fold increase in intracellular heme. This imparted a meat-like reddish hue to the fungal biomass, enhancing its potential as an animal meat analog [118].

5. Discussion and Future Perspectives

The advent of the CRISPR-Cas9 system, enabling precise, efficient, and multiplexed genome editing, has overcome the limitations of traditional methods and dramatically accelerated research and industrial breeding in Aspergillus. The CRISPR-Cas9 system has been used on a variety of pathogenic and industrially important Aspergillus species, including A. fumigatus, A. flavus, A. terreus, A. oryzae, A. niger, and A. nidulans. By targeting Aspergillus-specific genes involved in metabolic pathways, developmental regulation, or stress responses, researchers can elucidate gene function and regulatory mechanisms with improved precision. Specifically, it is used to optimize fungal cell factories for sustainable production, to elucidate the pathogenicity of plant pathogens, and to silence virulence factors in human pathogens. Its versatility, extending from gene knockout to precise knock-in and base editing, directly accelerates the discovery of novel bioactive compounds and enables the tailored improvement in strains for industrial adaptability. However, the application of CRISPR-Cas9 systems in filamentous fungal factories, while established in principle, is far from being industrially mature. Current research frontiers are actively addressing these gaps, as exemplified by the recent development of a visual, multiplex integration toolkit for A. niger, which achieved 100% editing efficiency at single loci and enabled one-step, marker-free integration of expression cassettes into three genomic loci, boosting enzyme yield by nearly 50% [91].

Looking beyond these foundational efforts, the ultimate translation of engineered strains into industrial-scale production presents a distinct set of challenges. The industrial application of CRISPR-Cas9-engineered Aspergillus strains faces significant hurdles, primarily in ensuring long-term genetic stability for cost-effective bioprocessing without antibiotic selection. This necessitates stable genomic integration of engineered pathways, a fundamental requirement for reliable industrial bioproduction [119]. Furthermore, advanced synthetic biology strategies, such as the balanced-lethal systems used to maintain plasmid stability in engineered microbial therapeutics, provide a valuable blueprint for enhancing the robustness of fungal cell factories [120]. As these enabling technologies mature alongside a deeper understanding of fungal physiology, the precision, efficiency, and ultimately the industrial robustness of engineered Aspergillus strains are poised for significant advancement. Notably, species such as A. oryzae and A. niger, which have a long history of safe use in the food industry as GRAS organisms [121], are particularly promising chassis. These species are poised to serve as superior cell factories, making remarkable strides in the production of beneficial secondary metabolites and secreted proteins.

To fully realize this potential, future advancements in CRISPR-Cas9 systems for filamentous fungi must focus on overcoming several key barriers, such as low transformation efficiency and CRISPR-associated cytotoxicity. These barriers, along with the broader challenges and methodological considerations for applying CRISPR-Cas9 in filamentous fungi, have been systematically reviewed [122]. The general strategies to overcome them—including optimizing expression systems, delivery methods, and Cas9 variants—are well outlined in CRISPR tool development for unicellular fungi like yeast, providing a crucial conceptual framework for adaptation in filamentous species [123]. For example, the efficacy of CRISPR-Cas9 is closely related to the recognition of compatible PAMs, which restrict editable genomic loci. While the classical NGG PAM is dominant in current applications, exploring novel Cas9 variants or orthologs (e.g., SaCas9, FnCas9, or engineered Cas9-NG) with a wider range of PAM recognition (e.g., NRN, NYN, or relaxed motifs) could unlock previously inaccessible regions in Aspergillus. The principle and high efficiency of this approach have been robustly demonstrated in model systems such as yeast, where the “GTR 2.0” system utilizing SpCas9-NG achieved near 100% editing efficiency across all NGN PAM sequences [124], providing a strong technical blueprint for adaptation in Aspergillus. Moving forward, the combination of the CRISPR-Cas9 system with high-throughput screening methods is a promising research direction to establish a general editing system that is not limited to specific fungal species. Furthermore, coupling CRISPR-Cas9 with synthetic biology and metabolic engineering can unlock the full potential of fungal systems for diverse applications, including the discovery of novel bioactive compounds and the optimized production of valuable metabolites and proteins. By refining these synergies, CRISPR-Cas9 is poised to bridge the translation gap between laboratory discoveries and real-world biotechnological solutions.

6. Conclusions

The introduction of CRISPR-Cas9 technology marks a fundamental transformation in the genetic manipulation of Aspergillus fungi. As this review has detailed, the system has overcome the limitations of conventional methods. It now acts as a pivotal link between fundamental fungal biology and applied biotechnology, enabling precise investigations into pathogenicity, the reprogramming of metabolic pathways, and the development of efficient cell factories.

To fully realize this potential, the field must now shift its focus from proving technical feasibility to achieving robust and scalable industrial applications. The critical steps forward involve overcoming persistent bottlenecks in editing efficiency and genetic stability, followed by seamless integration with synthetic biology platforms. Success in this endeavor will cement engineered Aspergillus strains, with a special emphasis on those possessing established safety profiles, as versatile and sustainable cell factories for future biomanufacturing.

Author Contributions

Formal analysis, D.H., R.Z. and Y.L.; writing—original draft preparation, D.H., R.Z. and Y.L.; investigation, D.H. and R.Z.; software, C.J.; methodology, C.J.; writing—review and editing, C.J.; supervision, C.J.; funding acquisition, C.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number 31900063; Jiangxi Provincial Department of Education Science and Technology Project, grant number GJJ211103; and the Doctoral Scientific Research Foundation of Jiangxi Science and Technology Normal University, grant number 2018BSQD027.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new datasets were generated or analyzed during this study. This review is based on previously published studies, all of which are cited in the reference list.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Baniya, S. Aspergillus: Morphology, Clinical Features, and Lab Diagnosis. Mycology. Available online: https://microbeonline.com/aspergillus-morphology-clinical-features-and-lab-diagnosis/#Aspergillus_glaucus (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Samson, R.A.; Visagie, C.M.; Houbraken, J.; Hong, S.B.; Hubka, V.; Klaassen, C.H.; Perrone, G.; Seifert, K.A.; Susca, A.; Tanney, J.B.; et al. Phylogeny, identification and nomenclature of the genus Aspergillus. Stud. Mycol. 2014, 78, 141–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaike, S.; Keller, N.P. Aspergillus flavus. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2011, 49, 107–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reijula, K.; Tuomi, T. Mycotoxins of aspergilli: Exposure and health effects. Front. Biosci. 2003, 8, s232–s235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lass-Florl, C.; Dietl, A.M.; Kontoyiannis, D.P.; Brock, M. Aspergillus terreus species complex. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2021, 34, e00311-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhodes, J.C. Aspergillus fumigatus: Growth and virulence. Med. Mycol. 2006, 44, S77–S81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hedayati, M.T.; Pasqualotto, A.C.; Warn, P.A.; Bowyer, P.; Denning, D.W. Aspergillus flavus: Human pathogen, allergen and mycotoxin producer. Microbiology 2007, 153, 1677–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allwood, J.G.; Wakeling, L.T.; Bean, D.C. Fermentation and the microbial community of Japanese koji and miso: A review. J. Food Sci. 2021, 86, 2194–2207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cairns, T.C.; Nai, C.; Meyer, V. How a fungus shapes biotechnology: 100 years of Aspergillus niger research. Fungal Biol. Biotechnol. 2018, 5, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oikawa, H. Heterologous production of fungal natural products: Reconstitution of biosynthetic gene clusters in model host Aspergillus oryzae. Proc. Jpn. Acad. Ser. B Phys. Biol. Sci. 2020, 96, 420–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frandsen, R.J.N.; Khorsand-Jamal, P.; Kongstad, K.T.; Nafisi, M.; Kannangara, R.M.; Staerk, D.; Okkels, F.T.; Binderup, K.; Madsen, B.; Møller, B.L.; et al. Heterologous production of the widely used natural food colorant carminic acid in Aspergillus nidulans. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 12853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh, H.H.; Morita, N.; Sakamoto, T.; Katayama, T.; Miyakawa, T.; Tanokura, M.; Chiba, Y.; Shinkura, R.; Maruyama, J.I. Functional production of human antibody by the filamentous fungus Aspergillus oryzae. Fungal Biol. Biotechnol. 2020, 7, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishimura, I.; Shinohara, Y.; Oguma, T.; Koyama, Y. Survival strategy of the salt-tolerant lactic acid bacterium Tetragenococcus halophilus to counteract koji mold, Aspergillus oryzae, in soy sauce brewing. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2018, 82, 1437–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dao, T.T.; de Mattos-Shipley, K.M.J.; Prosser, I.M.; Williams, K.; Zacharova, M.K.; Lazarus, C.M.; Willis, C.L.; Bailey, A.M. Cleaning the cellular factory—Deletion of McrA in Aspergillus oryzae NSAR1 and the generation of a novel kojic acid deficient strain for cleaner heterologous production of secondary metabolites. Front. Fungal Biol. 2021, 2, 632542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daba, G.M.; Mostafa, F.A.; Elkhateeb, W.A. The ancient koji mold (Aspergillus oryzae) as a modern biotechnological tool. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 2021, 8, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hama, S.; Tamalampudi, S.; Suzuki, Y.; Yoshida, A.; Fukuda, H.; Kondo, A. Preparation and comparative characterization of immobilized Aspergillus oryzae expressing Fusarium heterosporum lipase for enzymatic biodiesel production. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2008, 81, 637–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papagianni, M. Advances in citric acid fermentation by Aspergillus niger: Biochemical aspects, membrane transport and modeling. Biotechnol. Adv. 2007, 25, 244–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idris, A.D.; Abalaka, M.E.; Oyewole, O.A.; Egwim, E.C.; Maddela, N.R. Purification and characterization of β-galactosidase from Aspergillus niger PQ570689 for lactose hydrolysis and prebiotic synthesis. Folia Microbiol. 2025, 70, 01293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, H.S.; Jun, S.C.; Han, K.H.; Hong, S.B.; Yu, J.H. Diversity, application, and synthetic biology of industrially important Aspergillus fungi. In Advances in Applied Microbiology; Sariaslani, S., Gadd, G.M., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017; Volume 100, pp. 161–202. [Google Scholar]

- Książek, E. Citric acid: Properties, microbial production, and applications in industries. Molecules 2024, 29, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, T.; Liu, G.; Ji, R.; Shi, K.; Song, P.; Ren, L.; Huang, H.; Ji, X. CRISPR/Cas9-based genome editing of the filamentous fungi: The state of the art. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2017, 101, 7435–7443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Chen, H.; Tang, X.; Zhang, H.; Chen, W.; Chen, Y.Q. Molecular tools for gene manipulation in filamentous fungi. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2017, 101, 8063–8075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, P.K. Creating large chromosomal segment deletions in Aspergillus flavus by a dual CRISPR/Cas9 system: Deletion of gene clusters for production of aflatoxin, cyclopiazonic acid, and ustiloxin B. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2024, 170, 103863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maruyama, J. Genome editing technology and its application potentials in the industrial filamentous fungus Aspergillus oryzae. J. Fungi 2021, 7, 638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruyama, J.; Nakajima, H.; Kitamoto, K. Visualization of nuclei in Aspergillus oryzae with EGFP and analysis of the number of nuclei in each conidium by FACS. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2001, 65, 1504–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCarty, N.S.; Graham, A.E.; Studená, L.; Ledesma-Amaro, R. Multiplexed CRISPR technologies for gene editing and transcriptional regulation. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nodvig, C.S.; Nielsen, J.B.; Kogle, M.E.; Mortensen, U.H. A CRISPR-Cas9 system for genetic engineering of filamentous fungi. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0133085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, R.; Chen, L.; Jiang, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Zou, G. Efficient genome editing in filamentous fungus Trichoderma reesei using the CRISPR/Cas9 system. Cell Discov. 2015, 1, 15007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pohl, C.; Kiel, J.A.; Driessen, A.J.; Bovenberg, R.A.; Nygård, Y. CRISPR/Cas9 based genome editing of Penicillium chrysogenum. ACS Synth. Biol. 2016, 5, 754–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsu-Ura, T.; Baek, M.; Kwon, J.; Hong, C. Efficient gene editing in Neurospora crassa with CRISPR technology. Fungal Biol. Biotechnol. 2015, 2, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruttner, S.; Kempken, F. A user-friendly CRISPR/Cas9 system for mutagenesis of Neurospora crassa. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 20469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuster, M.; Kahmann, R. CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing approaches in filamentous fungi and oomycetes. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2019, 130, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, G.; Deng, S.; Czajka, J.J.; Dai, Z.; Hofstad, B.A.; Kim, J.; Pomraning, K.R. CRISPR-Cas9/Cas12a systems for efficient genome editing and large genomic fragment deletions in Aspergillus niger. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2024, 12, 1452496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayorga, M.E.; Timberlake, W.E. Isolation and molecular characterization of the Aspergillus nidulans wA gene. Genetics 1990, 126, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuivanen, J.; Korja, V.; Holmstrom, S.; Richard, P. Development of microtiter plate scale CRISPR/Cas9 transformation method for Aspergillus niger based on in vitro assembled ribonucleoprotein complexes. Fungal Biol. Biotechnol. 2019, 6, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nan, Y.; Ouyang, L.; Chu, J. In vitro CRISPR/Cas9 system for genome editing of Aspergillus niger based on removable bidirectional selection marker AmdS. Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem. 2021, 68, 964–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, P.K. A simple CRISPR/Cas9 system for efficiently targeting genes of Aspergillus section Flavi species, Aspergillus nidulans, Aspergillus fumigatus, Aspergillus terreus, and Aspergillus niger. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e0464822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Lu, J.; Zhang, G.; Zhou, J.; Li, J.; Du, G.; Chen, J. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated multiplexed genome editing in Aspergillus oryzae. J. Fungi 2023, 9, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Todokoro, T.; Hata, Y.; Ishida, H. CRISPR/Cas9 improves targeted knock-in efficiency in Aspergillus oryzae. Biotechnol. Notes 2024, 5, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mojica, F.J.M.; Rodriguez-Valera, F. The discovery of CRISPR in archaea and bacteria. FEBS J. 2016, 283, 3162–3169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amitai, G.; Sorek, R. CRISPR-Cas adaptation: Insights into the mechanism of action. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2016, 14, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrangou, R.; Fremaux, C.; Deveau, H.; Richards, M.; Boyaval, P.; Moineau, S.; Romero, D.A.; Horvath, P. CRISPR provides acquired resistance against viruses in prokaryotes. Science 2007, 315, 1709–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makarova, K.S.; Grishin, N.V.; Shabalina, S.A.; Wolf, Y.I.; Koonin, E.V. A putative RNA-interference based immune system in prokaryotes: Computational analysis of the predicted enzymatic machinery, functional analogies with eukaryotic RNAi, and hypothetical mechanisms of action. Biol. Direct 2006, 1, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makarova, K.S.; Wolf, Y.I.; Alkhnbashi, O.S.; Costa, F.; Shah, S.A.; Saunders, S.J.; Barrangou, R.; Brouns, S.J.J.; Charpentier, E.; Haft, D.H.; et al. An updated evolutionary classification of CRISPR-Cas systems. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2015, 13, 722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaudhary, E.; Sharma, S.; Tiwari, V.; Garg, M. Different Classes of CRISPR-Cas Systems. In Gene Editing in Plants; Kumar, A., Arora, S., Ogita, S., Yau, Y.Y., Mukherjee, K., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2024; pp. 73–94. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, S.A.; McKenzie, R.E.; Fagerlund, R.D.; Kieper, S.N.; Fineran, P.C.; Brouns, S.J.J. CRISPR-Cas: Adapting to change. Science 2017, 356, eaal5056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouns, S.J.; Jore, M.M.; Lundgren, M.; Westra, E.R.; Slijkhuis, R.J.; Snijders, A.P.; Dickman, M.J.; Makarova, K.S.; Koonin, E.V.; van der Oost, J. Small CRISPR RNAs guide antiviral defense in prokaryotes. Science 2008, 321, 960–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jinek, M.; Chylinski, K.; Fonfara, I.; Hauer, M.; Doudna, J.A.; Charpentier, E. A programmable dual-RNA-guided DNA endonuclease in adaptive bacterial immunity. Science 2012, 337, 816–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samai, P.; Pyenson, N.; Jiang, W.; Goldberg, G.W.; Hatoum-Aslan, A.; Marraffini, L.A. Co-transcriptional DNA and RNA Cleavage during Type III CRISPR-Cas Immunity. Cell 2015, 161, 1164–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zetsche, B.; Gootenberg, J.S.; Abudayyeh, O.O.; Slaymaker, I.M.; Makarova, K.S.; Essletzbichler, P.; Volz, S.E.; Joung, J.; van der Oost, J.; Regev, A.; et al. Cpf1 is a single RNA-guided endonuclease of a class 2 CRISPR-Cas system. Cell 2015, 163, 759–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abudayyeh, O.O.; Gootenberg, J.S.; Konermann, S.; Joung, J.; Slaymaker, I.M.; Cox, D.B.; Shmakov, S.; Makarova, K.S.; Semenova, E.; Minakhin, L.; et al. C2c2 is a single-component programmable RNA-guided RNA-targeting CRISPR effector. Science 2016, 353, aaf5573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaj, T.; Gersbach, C.A.; Barbas, C.F., 3rd. ZFN, TALEN, and CRISPR/Cas-based methods for genome engineering. Trends Biotechnol. 2013, 31, 397–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasiunas, G.; Barrangou, R.; Horvath, P.; Siksnys, V. Cas9–crRNA ribonucleoprotein complex mediates specific DNA cleavage for adaptive immunity in bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, E2579–E2586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deltcheva, E.; Chylinski, K.; Sharma, C.M.; Gonzales, K.; Chao, Y.; Pirzada, Z.A.; Eckert, M.R.; Vogel, J.; Charpentier, E. CRISPR RNA maturation by trans-encoded small RNA and host factor RNase III. Nature 2011, 471, 602–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hale, C.R.; Zhao, P.; Olson, S.; Duff, M.O.; Graveley, B.R.; Wells, L.; Terns, R.M.; Terns, M.P. RNA-guided RNA cleavage by a CRISPR RNA-Cas protein complex. Cell 2009, 139, 945–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sander, J.D.; Joung, J.K. CRISPR-Cas systems for editing, regulating and targeting genomes. Nat. Biotechnol. 2014, 32, 347–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, P.D.; Scott, D.A.; Weinstein, J.A.; Ran, F.A.; Konermann, S.; Agarwala, V.; Li, Y.; Fine, E.J.; Wu, X.; Shalem, O.; et al. DNA targeting specificity of RNA-guided Cas9 nucleases. Nat. Biotechnol. 2013, 31, 827–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.H.; Miller, S.M.; Geurts, M.H.; Tang, W.; Chen, L.; Sun, N.; Zeina, C.M.; Gao, X.; Rees, H.A.; Lin, Z.; et al. Evolved Cas9 variants with broad PAM compatibility and high DNA specificity. Nature 2018, 556, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, Y.; Wang, J.; Jiang, T.; Zou, Y.; Yan, Y. Engineering a Streptococcus Cas9 ortholog with an RxQ PAM-binding motif for PAM-free gene control in bacteria. ACS Synth. Biol. 2023, 12, 2764–2772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinstiver, B.P.; Pattanayak, V.; Prew, M.S.; Tsai, S.Q.; Nguyen, N.T.; Zheng, Z.; Joung, J.K. High-fidelity CRISPR-Cas9 nucleases with no detectable genomewide off-target effects. Nature 2016, 529, 490–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kleinstiver, B.P.; Prew, M.S.; Tsai, S.Q.; Topkar, V.V.; Nguyen, N.T.; Zheng, Z.; Gonzales, A.P.W.; Li, Z.; Peterson, R.T.; Yeh, J.R.J.; et al. Engineered CRISPR-Cas9 nucleases with altered PAM specificities. Nature 2015, 523, 481–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ran, F.A.; Hsu, P.D.; Lin, C.Y.; Gootenberg, J.S.; Konermann, S.; Trevino, A.E.; Scott, D.A.; Inoue, A.; Matoba, S.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Double nicking by RNA-guided CRISPR Cas9 for enhanced genome editing specificity. Cell 2013, 154, 1380–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walton, R.T.; Christie, K.A.; Whittaker, M.N.; Kleinstiver, B.P. Unconstrained genome targeting with near-PAMless engineered CRISPR-Cas9 variants. Science 2020, 368, 290–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Tao, C.; Mao, H.; Hou, L.; Wang, Y.; Qi, T.; Yang, Y.; Ong, S.G.; Hu, S.; Chai, R.; et al. Correction: Identification of SaCas9 orthologs containing a conserved serine residue that determines simple NNGG PAM recognition. PLoS Biol. 2025, 23, e3003036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Cai, Y.; Sun, S.; Han, T.; Chen, L.; Hou, W. Using Staphylococcus aureus Cas9 to expand the scope of potential gene targets for genome editing in soybean. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 12789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, E.; Koo, T.; Park, S.W.; Kim, D.; Kim, K.; Cho, H.Y.; Song, D.W.; Lee, K.J.; Jung, M.H.; Kim, S.; et al. In vivo genome editing with a small Cas9 orthologue derived from Campylobacter jejuni. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 14500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Wang, Y.; Qi, T.; Wei, J.; Hu, Z.; Liu, J.; Sun, S.; Liu, H.; Wang, Y. Genome editing with natural and engineered CjCas9 orthologs. Mol. Ther. 2023, 31, 1177–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, S.M.; Wang, T.; Randolph, P.B.; Arbab, M.; Shen, M.W.; Huang, T.P.; Matuszek, Z.; Newby, G.A.; Rees, H.A.; Liu, D.R. Continuous evolution of SpCas9 variants compatible with non-G PAMs. Nat. Biotechnol. 2020, 38, 471–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, P.; Jakimo, N.; Lee, J.; Amrani, N.; Rodríguez, T.; Koseki, S.R.T.; Tysinger, E.; Qing, R.; Hao, S.; Sontheimer, E.J.; et al. An engineered ScCas9 with broad PAM range and high specificity and activity. Nat. Biotechnol. 2020, 38, 1154–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Upton, A.; Kirby, K.A.; Carpenter, P.; Boeckh, M.; Marr, K.A. Invasive aspergillosis following hematopoietic cell transplantation: Outcomes and prognostic factors associated with mortality. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2007, 44, 531–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krappmann, S.; Bayram, O.; Braus, G.H. Deletion and allelic exchange of the Aspergillus fumigatus veA locus via a novel recyclable marker module. Eukaryot. Cell 2005, 4, 1298–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassane, A.M.A.; Obiedallah, M.; Karimi, J.; Khattab, S.M.R.; Hussein, H.R.; Abo-Dahab, Y.; Eltoukhy, A.; Abo-Dahab, N.F.; Abouelela, M.E. Unravelling fungal genome editing revolution: Pathological and biotechnological application aspects. Arch. Microbiol. 2025, 207, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, K.K.; Chen, S.; Loros, J.J.; Dunlap, J.C. Development of the CRISPR/Cas9 system for targeted gene disruption in Aspergillus fumigatus. Eukaryot. Cell 2015, 14, 1073–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Meng, X.; Wei, X.; Lu, L. Highly efficient CRISPR mutagenesis by microhomology-mediated end joining in Aspergillus fumigatus. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2016, 86, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sastre-Velasquez, L.E.; Mach, N.; Mertens, B.; Kuhbacher, A.; Merschak, P.; Dallemulle, A.; Lechner, L.; Baldin, C.; Diallinas, G.; Gsaller, F. Simultaneous multigene integration in Aspergillus fumigatus using CRISPR/Cas9 and endogenous counter-selectable markers. J. Biol. Eng. 2025, 19, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nair, A.; Rao, A.S.; Surabhi, M.A.; Gnanika, M.; More, S.S. Unravelling fungal pathogenesis: Advances in CRISPR-Cas9 for understanding virulence and adaptation. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2025, 179, 104006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudakova, A.; Spiess, B.; Tangwattanachuleeporn, M.; Sasse, C.; Buchheidt, D.; Weig, M.; Groß, U.; Bader, O. Molecular tools for the detection and deduction of azole antifungal drug resistance phenotypes in Aspergillus species. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2017, 30, 1065–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meis, J.F.; Chowdhary, A.; Rhodes, J.L.; Fisher, M.C.; Verweij, P.E. Clinical implications of globally emerging azole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 2016, 371, 20150460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rybak, J.M.; Ge, W.; Wiederhold, N.P.; Parker, J.E.; Kelly, S.L.; Rogers, P.D.; Fortwendel, J.R. Mutations in hmg1, challenging the paradigm of clinical triazole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus. mBio 2019, 10, e00437-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arai, T.; Umeyama, T.; Majima, H.; Inukai, T.; Watanabe, A.; Miyazaki, Y.; Kamei, K. hmg1 mutations in Aspergillus fumigatus and their contribution to triazole susceptibility. Med. Mycol. 2021, 59, 980–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handelman, M.; Osherov, N. Efficient generation of multiple seamless point mutations conferring triazole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus. J. Fungi 2023, 9, 644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, A.C.O.; Martin-Vicente, A.; Nywening, A.V.; Ge, W.; Lowes, D.J.; Peters, B.M.; Fortwendel, J.R. Loss of septation initiation network (SIN) kinases blocks tissue invasion and unlocks echinocandin cidal activity against Aspergillus fumigatus. PLoS Pathog. 2021, 17, e1009806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandyopadhyay, R.; Atehnkeng, J.; Ortega Beltran, A.; Akande, A.; Falade, T.D.O.; Cotty, P.J. ‘Ground-Truthing’ Efficacy of Biological Control for Aflatoxin Mitigation in Farmers’ Fields in Nigeria: From Field Trials to Commercial Usage, a 10-Year Study. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 2528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhi, Q.Q.; Li, J.Y.; Liu, Q.Y.; He, Z.M. A cytosine methyltransferase ortholog dmtA is involved in the sensitivity of Aspergillus flavus to environmental stresses. Fungal Biol. 2017, 121, 501–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmbeck, J.; Andersen, B.; Sáez-Sáez, J.; Frisvad, J.C.; Arnau, J. Mycotoxin-Free Aspergillus oryzae Strain Lineage for Alternative and Novel Protein Production at Industrial Scale. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2025, 109, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisvad, J.C.; Møller, L.L.; Larsen, T.O.; Kumar, R.; Arnau, J. Safety of the Fungal Workhorses of Industrial Biotechnology: Update on the Mycotoxin and Secondary Metabolite Potential of Aspergillus niger, Aspergillus oryzae, and Trichoderma reesei. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2018, 102, 9481–9515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, F.J.; Hu, S.; Wang, B.T.; Jin, L. Advances in Genetic Engineering Technology and Its Application in the Industrial Fungus Aspergillus oryzae. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 644404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anantayanon, J.; Jeennor, S.; Panchanawaporn, S.; Chutrakul, C.; Laoteng, K. Significance of Two Intracellular Triacylglycerol Lipases of Aspergillus oryzae in Lipid Mobilization: A Perspective in Industrial Implication for Microbial Lipid Production. Gene 2021, 793, 145745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chutrakul, C.; Panchanawaporn, S.; Jeennor, S.; Anantayanon, J.; Laoteng, K. Promoter Exchange of the Cryptic Nonribosomal Peptide Synthetase Gene for Oligopeptide Production in Aspergillus oryzae. J. Microbiol. 2022, 60, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, H.; Zheng, J.; Yu, D.; Wang, B.; Pan, L. Efficient Genome Editing in Aspergillus niger with an Improved Recyclable CRISPR-HDR Toolbox and Its Application in Introducing Multiple Copies of Heterologous Genes. J. Microbiol. Methods 2019, 163, 105655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Li, C.; Fu, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Ma, J.; Zhou, J.; Li, J.; Du, G.; Liu, S. A CRISPR/Cas9-Based Visual Toolkit Enabling Multiplex Integration at Specific Genomic Loci in Aspergillus niger. Synth. Syst. Biotechnol. 2024, 9, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nie, H.; Jin, M.; Wang, Z.; Zheng, J.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X. Heterologous Expression of Candida antarctica Lipase B in Aspergillus niger Using CRISPR/Cas9-Mediated Multi-Gene Editing. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2025, 122, 1770–1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benites-Pariente, J.S.; Samolski, I.; Ludeña, Y.; Villena, G.K. CRISPR/Cas9 Mediated Targeted Knock-In of eglA Gene to Improve Endoglucanase Activity of Aspergillus fumigatus LMB-35Aa. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 19661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cairns, T.C.; Feurstein, C.; Zheng, X.; Zhang, L.H.; Zheng, P.; Sun, J.; Meyer, V. Functional Exploration of Co-Expression Networks Identifies a Nexus for Modulating Protein and Citric Acid Titres in Aspergillus niger Submerged Culture. Fungal Biol. Biotechnol. 2019, 6, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, L.; Lin, X.; Yu, D.; Huang, L.; Wang, B.; Pan, L. High-Level Expression of Highly Active and Thermostable Trehalase from Myceliophthora thermophila in Aspergillus niger by Using the CRISPR/Cas9 Tool and Its Application in Ethanol Fermentation. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2020, 47, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, L.; Yu, D.; Lin, X.; Wang, B.; Pan, L. Improving Expression of Thermostable Trehalase from Myceliophthora sepedonium in Aspergillus niger Mediated by the CRISPR/Cas9 Tool and Its Purification, Characterization. Protein Expr. Purif. 2020, 165, 105482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerhardt, J.A.; Rubio, M.V.; Terrasan, C.R.F.; Wassano, N.S.; Rodrigues, A.; Figueiredo, F.L.; Antoniel, E.P.; Contesini, F.J.; Dias, A.H.S.; Mortensen, U.H.; et al. Improving recombinant protein secretion in Aspergillus nidulans by targeting the N-glycosylation machinery. Metab. Eng. Commun. 2025, 20, e00264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Zheng, P.; Zhang, K.; Cairns, T.C.; Meyer, V.; Sun, J.; Ma, Y. 5S rRNA Promoter for Guide RNA Expression Enabled Highly Efficient CRISPR/Cas9 Genome Editing in Aspergillus niger. ACS Synth. Biol. 2019, 8, 1568–1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Z.; Zheng, X.; Tong, Y.; Shi, Y.C.; Sun, J. Systems metabolic engineering for citric acid production by Aspergillus niger in the post-genomic era. Microb. Cell Fact. 2019, 18, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]