Simple Summary

Pollinators are crucial for diverse biological processes, but it is recognized that there has been a decline in their populations in recent years. Hence, the study of the population dynamics of pollinators is a relevant topic for research. In this study, to contribute to the state of the art of mathematical modeling of population dynamics, we searched the relevant literature in two databases. This review explores the different contributions, develops a summary and classification, and states some future work to understand the behavior of pollinator interactions.

Abstract

In this paper, we develop a systematic review of the existing literature on the mathematical modeling of several aspects of pollinators. We selected the MathSciNet and Wos databases and performed a search for the words “pollinator” and “mathematical model”. This search yielded a total of 236 records. After a detailed screening process, we retained 107 publications deemed most relevant to the topic of mathematical modeling in pollinator systems. We conducted a bibliometric analysis and categorized the studies based on the mathematical approaches used as the central tool in the mathematical modeling and analysis. The mathematical theories used to obtain the mathematical models were ordinary differential equations, partial differential equations, graph theory, difference equations, delay differential equations, stochastic equations, numerical methods, and other types of theories, like fractional order differential equations. Meanwhile, the topics were positive bounded solutions, equilibrium and stability analysis, bifurcation analysis, optimal control, and numerical analysis. We summarized the research findings and identified some challenges that could inform the direction of future research, highlighting areas that will aid in the development of future research.

1. Introduction

In the last few decades, the study of pollinators has attracted the attention of several researchers, as it is known that pollinators play a crucial role as ecosystem regulators in nature [1,2,3,4,5]. It is known that there are several types of pollinators, including birds, bats, butterflies, moths, flies, beetles, wasps, small mammals, and, most importantly, insects like bees. These animals are responsible for the bulk of pollination, which significantly affects our daily lives. Some important facts about pollinators are that three out of four crops depend on pollinators; in the extreme case of total disappearance of pollinators, this would lead to a decrease in world food production; and the causes of pollinator decline include disease, climate change, and pesticides. The problem associated with pollinators is complex and should be analyzed from multiple scientific perspectives, particularly biology, chemistry, and mathematics.

Pollination is a crucial event in the reproductive cycle of flowering plants. In this context, several characteristics associated with the evolutionary process of species help maintain and optimize the functioning of various ecosystems [6]. Two widely studied phenomena are flowers that produce nectar and those that do not. First, we consider flowers that produce nectar to be a food source. Some plants provide nectar to pollinators as a reward for their assistance in pollination. In this context, a notable aspect is the fact that plants conceal their nectar, which prevents pollinators from detecting its presence without first entering the flower. Second, we know that there are plants that do not produce nectar. Nectar production requires a considerable amount of energy; some flowers can employ deceptive strategies by not producing nectar. Despite lacking nectar, these flowers can still be pollinated by pollinators. An example of this type of plant is found in certain orchid species, which are pollinated through a phenomenon known as Batesian mimicry. Nectarless flowers are likely the result of evolutionary optimization. Additionally, other pollination-related phenomena include the fact that flowers can also attract pollinators by producing large floral displays, even if they provide no reward. There are pollinators skilled at extracting nectar without pollinating the flower, known as nectar robbers. There are also indirect pollinators, such as ants, which seek other plant nutrients or prey on insects living on the plant, rather than directly seeking nectar or pollen.

In this paper, we aim to elucidate the existing studies on pollinators from a mathematical perspective. Several phenomena related to pollinators can be analyzed using mathematical modeling, such as the dynamics of pollinator populations, plant–pollinator interactions, the effects of climate change on pollinator decline, the impact of pesticides on pollinator populations, and the spread of infectious diseases among pollinators. A recent review developed by Chen et al. introduced the framework of different mathematical models related to the dynamics of honeybee populations [7]. However, to the extent of our knowledge, there is no comprehensive review of the state of the art in mathematical modeling of pollinators and related topics. Therefore, we conducted a systematic literature review using bibliometric methods and following the methodology detailed in [8] (see also [9]).

We surveyed the MathSciNet and WoS databases and examined the topics of each work. We obtained a set of 107 works, comprising 105 journal articles, 1 PhD thesis, and 1 book chapter related to the mathematical modeling of pollinators. The retained list of articles ranged from 1978 to 2025. We analyzed the papers and established a classification based on the mathematical theory involved in the mathematical modeling formulation. The classification introduced considers four groups: ordinary, differential equation models, partial differential equation models, network-based models, and other methodologies. In the case of other methodologies, we found discrete mathematical-based models, stochastic models, and others. We outlined some key contributions of the papers and compiled a list of topics that highlight potential challenges and perspectives for further research on the topic.

This paper is outlined as follows. In Section 2, we describe the methodology, including the list of selected relevant works that were identified and analyzed, as well as the bibliometric analysis. In Section 3, we report the results of the main findings arising from analysis of the existing literature on the mathematical modeling of pollinators. In Section 4, we discuss some biological issues of the retained list. In Section 5, we collect some aspects which are not included in the previous sections but are relevant for the completeness of the work. Finally, in Section 6, we present the conclusions of the paper and also outline some possible future research directions.

2. Methodological Framework

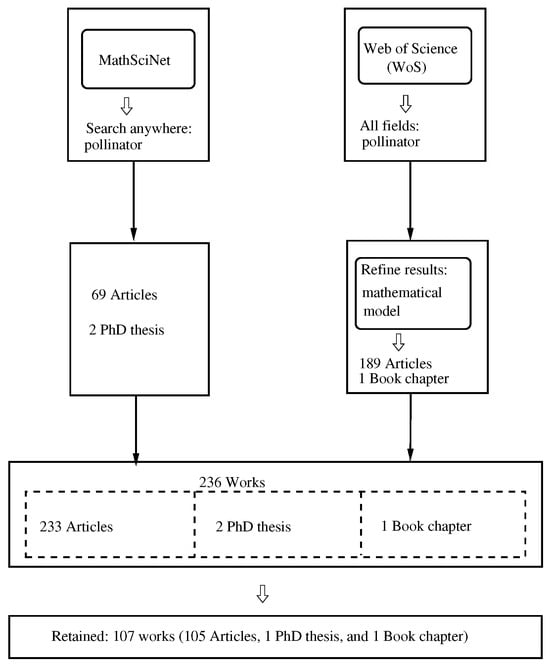

The methodology supporting the present work combines two approaches to developing a literature review: a systematic review and a bibliometric analysis. To be more precise, we adopted the methodology presented in [8], which consists of the five steps given in [9]: (1) framing questions for a review, (2) identifying relevant work, (3) assessing the quality of studies, (4) summarizing the evidence, and (5) interpreting the findings. The results for steps (1) and (2), step (3), and steps (4) and (5) are presented below in Section 2.1, Section 2.2, and Section 3, respectively. A synthesized visualization is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Schematic summary of the process used for identifying the relevant work (see Section 2).

2.1. Framing Questions for a Review and Identifying Relevant Work

We considered the following two questions:

- Question 1: What are the studies developed for mathematical modeling of the pollinator population’s dynamics?

- Question 2: What types of modeling approaches were used in those studies?

- Meanwhile, related to the step of identification of the relevant work, we selected two databases, MathSciNet and the Web of Science (WoS), with the following details:

- -

- MathSciNet (https://mathscinet.ams.org/mathscinet/, accessed on 14 April 2025): We searched for the word “pollinator” using the option “search term: anywhere” and found that the response reported a total of 71 items: 69 journal articles and 2 PhD theses.

- -

- WoS (https://www.webofscience.com/, accessed on 14 April 2025). We used the option “all fields” for the platform’s search engine to search for the word “pollinator”, obtaining 26,938 items. Then, by using the keyword “mathematical model” in the option “refine results”, we found 199 items: 198 journal articles and 1 book chapter.

When combining the two lists, we found that there were 34 duplicated items. Then, we obtained a list of 236 works: 233 journal articles, 2 PhD theses, and 1 book chapter. Here, we note that the search in both databases was not limited to the keyword “pollinator” being specified in the works.

We performed an examination of the 236 works and retained those which were related, namely with mathematical modeling as the topic of the paper, obtaining a list of 107 works [10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116]. In [19], there is a book chapter in conference proceedings, while [31] is a PhD thesis, and the other works are journal articles. We note two additional facts: the present review is registered in OSF (https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/3DWSR, accessed on 5 September 2025)), and for the inclusion criteria, we considered a work to be about mathematical modeling of pollinators when there was a proposal to research the population dynamics of pollinators.

2.2. Assessing the Quality of the Studies

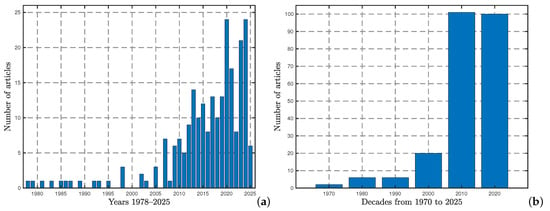

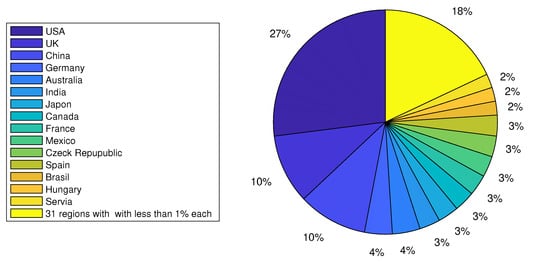

A graphical distribution of the list, by year and by decade from 1978 to 2025, is shown in Figure 2. Here, we observe that the oldest reference was from 1978, and the most recent one was from 2025. Also, we noticed a clear increase in articles over the decades, even though there were slight decreases in some years. Additionally, we also noted the geographic location declared by each of the authors in the corresponding affiliation for each article; the results are graphically presented in Figure 3. The affiliations of the authors were counted in the 236 works. The details for the retained list are given in Appendix A and more specifically in Table A1. The regions with the highest number of records were the United States of America (USA), the United Kingdom (UK), and China, with 205, 102, and 100 records, corresponding to 27%, 10%, and 10% of the works, respectively. These rankings were followed by regions with less than 4% representation as detailed below:

Figure 2.

Number of works in MathSciNet and the WoS related to the keywords “pollinators” and “mathematical models”. (a) Number of articles by year from 1978 to 2025. (b) Number of articles by decade.

Figure 3.

Percentages of the number of authors according to the geographic locations declared by the authors. We rounded off all percentages to their integers.

- -

- Brazil (45) and Australia (35) with 4% each;

- -

- India (29), Japan (29), Canada (28), France (28), Mexico (28), the Czech Republic (26), and Spain (25) with 3% each;

- -

- Brazil (22), Hungary (21), and Serbia (16) with 2% each;

- -

- Italy (14), South Africa (13), Denmark (11), Israel (10), Sweden (10), Taiwan (10), the Netherlands (9), New Zealand (9), Chile (8), Russia (8), Norway (7), Argentina (6), and Belgium (5) with 1% each;

- -

- Bulgaria (4), Finland (4), Poland (4), the Republic of Korea (4), Switzerland (4), the Philippines (3), Slovakia (3), Greece (2), Kenya (2), Estonia (2), Ecuador (1), Indonesia (1), Ireland (1), Pakistan (1), Portugal (1), Saudi Arabia (1), Slovenia (1), and Thailand (1) with 0% each.

Here, the number in parentheses is the number of records for the region. A graphical interpretation is given in Figure 3, with The oldest article being [5].

The indicators for journals and authors in the list are presented below. The retained articles in the list were published in 59 journals. Table 1 shows the nine journals which were in the first four positions according the published articles. We found that there were 13 journals with 2 publications and 37 journals with 1 publication. In Table 2, we show the top 10 journals according to the H index of the SCImago Journal & Country Rank (https://www.scimagojr.com/ accessed on 4 May 2025), and the SJR 2023 indicators, quartiles, and subject areas of those journals were obtained from SJR (https://jcr.clarivate.com/ accessed on 4 May 2025). Refer to Appendix B for more details. Moreover, in Table 3, we present the top four prolific authors. Meanwhile, Table 4 and Table 5 provide an extensive and structured synthesis of the retained literature. In Table 4, we detail the main findings of [10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116], and in Table 5, we organized the results by the seven major modeling domains identified (see Section 3.5). Each domain is characterized by its underlying biological assumptions, mathematical formulation, parametrization strategies, validation or calibration procedures, and key ecological insights. The table also highlights the potential policy implications derived from each modeling approach, thereby bridging theoretical contributions with applied relevance. This typological classification facilitates comparative analysis across studies and supports interdisciplinary integration of mathematical ecology, conservation planning, and empirical calibration. Representative references are included to exemplify each category and guide further exploration of methodological trends and thematic priorities.

Table 1.

The nine journals in the first four positions, considering the number of articles published.

Table 2.

The top 10 journals based on the H index, SJR index, and quartile. The information was obtained from Scimago https://www.scimagojr.com/ (accessed on 20 April 2025). Refer to Table A2 for the complete list of journals.

Table 3.

The top four authors with the highest number of articles in the selected list.

Table 4.

Summary of mathematical model topics and phenomena studied in the retained list of papers. Here, RR stands for retained reference.

Table 5.

Summary of retained studies according to biological topics and other characteristics.

3. Summarizing the Evidence and Interpreting the Findings

In Section 2.1, we introduced two questions. “Question 1” is clearly answered by the retained list [10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116]. Meanwhile, to answer “Question 1”, we introduce two classifications pertaining to the mathematical approaches used and the topics researched. We revised the retained list and defined the following four groups according to the mathematical theories applied for mathematical modeling:

- (1)

- Ordinary differential equations group (see Section 3.1): Here, we distinguish between three types of models based on the methodology used for modeling. First, we considered the Lotka–Volterra models for two populations (see Section 3.1.3). The works of this type are [10,11,15,22,28,30,33,47,55,68,73,76,86,88,91,96,104,106]. The second type was the Lotka–Volterra models for more than two populations (see Section 3.1.2), with the articles being [15,16,19,24,28,30,33,34,37,42,44,45,46,48,51,62,63,64,67,70,71,74,75,78,79,81,87,100,107,114,115]. The third class of ordinary differential equations systems was obtained via application of the compartmental methodology (see Section 3.1.3), and the works of this type are [14,36,38,39,41,61,83,85,89,90,93,98,105,110].

- (2)

- Partial differential equations group (see Section 3.1): The generalization of the ordinary differential equations to include the spatial displacement of pollinators was studied in [19,26,27,31,32,50,111].

- (3)

- Patch network (see Section 3.3): Consideration of groups of pollinators in different patches and the interaction of network concepts was conducted in [13,21,25,35,40,43,49,52,54,65,69,80,82,95,97,99,101,103,108,113]

- (4)

- Other methodologies (see Section 3.4): Other kinds of works like letters, reviews, and emergent methodologies like fractional-order or delay models were introduced in [12,17,18,20,23,26,29,53,56,57,58,59,60,66,84,94,102,104,109].

Extensive details are presented below in Section 3.1, Section 3.2, Section 3.3 and Section 3.4. We include a summarization of the topics covered by the studies in Section 3.5. We note that some works were considered to be in more than one group, as they examined mathematical modeling from multiple perspectives. For instance, the more typical case is that partial differential equation models are obtained as a generalization of ordinary differential equation models, and the same work can be considered to be in groups (1) and (2) (see, for example, [19]). Another example is [110], which involves multiple species and a class-structured (compartmental) framework, and it also incorporates nonlinear interaction terms that are characteristic of Lotka–Volterra systems. Therefore, it could alternatively be included in Section 3.1.2. However, it was placed in this subsection because the study’s primary focus lies in disease propagation and infestation dynamics rather than population-level coexistence or competitive interactions. This aligns it more closely with classical compartmental models such as SIR, SEIR, and related formulations. Furthermore, we obtained a Cohen’s kappa coefficient of 0.78.

3.1. Mathematical Models Based on Ordinary Differential Equations

3.1.1. Two Population Mathematical Models Using Lotka–Volterra-Like Methodologies

In the retained list, there are several works where the mathematical models were obtained through the interaction of two populations, such as plants and pollinators. The two basic assumptions required to obtain these mathematical models were as follows: there is an interaction between the pollinator and the plant, and the impact of various ecological and environmental variables is neglected. Then, the modeling approach focused on how the birth and death rates of both populations drove their changes or, equivalently, how the birth, death, and interactions of the populations affected population growth. Then, we deduced that

Let us denote the total population of plants and pollinators as p and a, respectively. Then, we have

To model the birth and death rates, we must consider several assumptions. To specify the algebraic forms modeling birth and death rates, we considered the discussion provided in [10]. We note that they modeled the plant–pollinator interaction via analogy with the Lotka–Volterra or prey-predator systems, assuming that the plants are predators and the pollinators are the prey.

The deduction of plant and pollinator birth rates in [10] was obtained by considering the following two assumptions: the plants are self-incompatible, and the plant birth rate is related to flower visits by the pollinators. They considered that the birth rate is proportional to the pollinator visits, neglected some factor like the finite supply of ovules, and assumed that the number of pollinator visits was modeled by a Holling’s functional such that the model was of the following form:

where , and model the number of ovules fertilized per visit, the searching rate constant multiplied by the encounter probability, and the handling time per visit, respectively. The encounter probability and the handling time depend on the energetic reward. More precisely, we have

where is the probability of an encounter, is the reciprocal speed of nectar extraction, and is the energetic reward. By combining Equation (5) with Equation (4), we deduce that

It is assumed that the pollinator birth depends on the density and some variables such as the competition for nest sites or protein resources such that

where is the maximum per capita pollinator birth rate and is the density-dependent regulation constant.

The deduction of plant and pollinator dead rates introduced in [10] is as follows. In the case of plant mortality, assume that it is proportional to the plant density, i.e., we have

where is the mortality rate. Meanwhile, for pollinators, it is assumed that the mortality pollinator rate is inversely related to the rate of energy intake, which in turn is jointly proportional to the visit rate and the energetic reward:

where is a constant of energetic transformation and is the maximum death rate of pollinators in the absence of plants.

By combining Equations (3), (6)–(9) with Equations (1) and (2), we obtain a system of the form

where

Here, we observe that is the carrying capacity of the pollinator population. Other mathematical models of the general form in Equation (10) were introduced in [11,15,22,28,30,33,47,55,68,73,76,86,88,91,96,104,106]. We remark that there are eight types of models, depending on the interaction populations: plant–pollinator [10,11,15,22,28,30,55,68,73,91,96], plant–robber [28], pollinator–secretor [33], pollinator–cheater [33], plant–novice pollinator [47], novice pollinator–expert pollinator [47], plant–plant [76,86], juvenile pollinator–adult pollinator [88,104], and honeybee–mite [106].

3.1.2. More Than Two Population Mathematical Models Using Lotka–Volterra-Like Methodologies

Analogous to the analysis developed in Section 3.1.1, we can consider that more than two species are interacting. To illustrate the concept, we consider the model introduced in [15], where the authors examined the interaction among three species—herbivores, plants, and pollinators—with populations denoted by x, y, and z, respectively. Then, by realizing a balance of birth rates, death rates, and interaction of the three populations, they deduced that the mathematical model is given by

where b is a density-dependent regulation constant, K measures the diversity of pollinators of plants, is a constant of energetic transformation, is the energetic reward, is the probability of an encounter, is the reciprocal speed of nectar extraction, is an efficiency constant representing the number of ovules fertilized per visit, is the plant mortality rate, is the pollinator mortality rate, a is the half-saturation constant, is the maximal ingestion rate, is the herbivore maximal growth rate, and is a function depending on the herbivore population density. We observe that Equations (12)–(14) can be rewritten in the following general form:

where is the density of the ith species, d is the number of interacting species, and models the birth rates, death rates, and interactions.

The mathematical models of the general form in Equation (10) with were introduced in the following 31 works from the retained list: [15,16,19,24,28,30,33,34,37,42,44,45,46,48,51,62,63,64,67,70,71,74,75,78,79,81,87,100,107,114,115]. In these works, the interacting populations were described as follows: plant–pollinator–hervibore [15,19,24,42,67,74,107], plant–pollinator–ant [24,44,45,46,51], plant–pollinator–robber [28,30,34,37,48,64], pollinator–secretor–cheater [33], plant–pollinator–flower [70,71,78,87], plant–novice pollinator-expert pollinator [47], two plants and one pollinator [63], two plants and two pollinators [62], plant–pollinator–pesticide [75], plant–pollinator–predator [100], plant–pollinator– parasite [114,115], plant–pollinator–green house gases–temperature [79], plant–seed–pollinator–seed disperser [81], and three general species [16].

3.1.3. Mathematical Models Based on Compartmental Methodology

The pollination system is formed by plants and pollinators. The plant population is divided into three sub-populations: susceptible (), pollinated (), and infected by a fungus (). Similarly, the pollinator population is divided into three states: can carry neither pollen nor fungal spores (), can carry pollen (), and can carry spores (). Moreover, we consider that the pollinated plants have a rate of return to the susceptible class. Then, by considering other assumptions regarding the interaction, Ingvarsson and Lundberg [14] introduced the following mathematical model:

where and and are positive parameters.

The mathematical models governed by ordinary differential equations which are based on the compartmental methodology were introduced in the following 14 works from the retained list: [14,36,38,39,41,61,83,85,89,90,93,98,105,110]. The populations modeled in the different articles are diverse. More precisely, they are a plant population with susceptible, pollinated, and infected classes and a pollinator population divided into three classes, where they can carry neither pollen nor fungal spores, can carry pollen, or can carry spores [14]; healthy bees and impaired bees [36]; an uncapped brood, capped brood, hive bees, foragers, and food [38]; plants biomass with adult insects and adult insects with larvae [39]; a pollinator with pollen, pollinator without pollen, unpollinated flowering plants, and pollinated flowering plants [41]; the interactions of adult and non-adult pollinators [61]; four types of pollinators [83]; infected bumblebees, infected honeybees, and infected flowers [85]; the dynamics of viral genotypes [89]; contamined flowers, infected bees, and virus carrying [90]; a honeybee-–parasite interaction model with seasonality [93]; hive bees, unimpaired forager bees, and impaired forager bees [98]; the transmission dynamics of deformed wing virus in a honeybee colony infested with Varroa mites [105]; and three plants and two pollinators with juvenile, male, and female plant classes and insects [110].

3.2. Mathematical Models Based on Partial Differential Equations

The mathematical models based on partial differential equations were obtained by assuming the spatial movement of the pollinators. It is considered that the displacement of pollinators satisfies a diffusion law. Then, the partial differential equations are extensions of ordinary differential equation models. For instance, in the case of the interaction of two populations, the authors of [19] considered the ordinary differential equation for a pollinator–plant interaction system:

where K is the carrying capacity for the pollinator population and a and p are the population densities of the pollinators and plants, respectively. Assuming that the pollinator population moves toward negative values of the gradient of the population density direction, the plants do not disperse, but their spatial distribution changes because of the interaction with the pollinator population. Then, the authors of [19] defined the new system extending the model in Equations (16) and (17) as follows:

where the parameter is the diffusivity of the pollinator population and is the Laplacian operator. Similarly, the authors of [19] assumed an ordinary differential model for pollinator–plant–herbivore interactions of the following type:

where K is the carry capacity for the pollinator population; p, and h are the population densities of pollinators, plants, and hervivores, respectively; g is a real function such that

in which and for all , modeling the reduction rate of visits of pollinators to plants due to herbivore interaction; is the number of fertilized ova in each pollinator visit; is the probability of visits; is a measure of the speed of nectar extraction; and is the energetic recompense. The generalization of Equations (20)–(22) to a partial differential system is given by

where the parameters and are the diffusivity of the pollinator and herbivore populations, respectively. Similar extensions of ordinary differential equations models were deduced via application of the compartmental methodology.

The mathematical models based on partial differential equations were considered in the following seven works: [19,26,27,31,32,50,111]. The modeled populations considered in the different articles are the following: the interaction of plant, pollinator, and herbivore populations [19,26]; harvester and scout populations Tyson [27]; multiple species of pollinators [31,32]; and plant and pollinator populations [50,111].

3.3. Network and Patch Mathematical Models

In the retained list, several works applied networks and patch concepts to model the dynamics of pollinator populations. In order to be precise, we consider [21], where the authors considered the interaction of a plant and animal , obtaining the following system:

where models the per capita colonization rate of a population of plants i when pollinated or dispersed by a pollinator j; is the per capita colonization rate of a pollinator j; and denote the per capita extinction rates for a plant i and animal j, respectively; d models the fraction of patches permanently lost through habitat destruction; and is the union of the patches occupied by n plant species interacting with the same j pollinator species.

In the retained list, we found that there were 20 works focused on the modeling of pollinator population dynamics using networks and patches [13,21,25,35,40,43,49,52,54,65,69,80,82,95,97,99,101,103,108,113]. In [13], the authors applied patch concepts to study the age-structured pollinator population model considering adult and non-adult pollinators [13]. Meanwhile, in the other works, the authors used networks and patch concepts [25,35,40,43,49,52,54,65,69,80,82,84,95,97,99,101,103,108,113].

3.4. Other Methodologies

Other articles that were difficult to include in the previous classification are the following 19 articles: [12,17,18,20,23,26,29,53,56,57,58,59,60,66,84,94,102,104,109]. These included a letter to the editor with an opinion on the mathematical model for mutualism on a patch [12], two review articles [26,102], a study on discrete models [20], a work focused on the study of virulence [23], a study on microscopic populations by considering five types of cells [17], a study on the fractional order mathematical mould for plant–pollinator–nectar interactions [84], a study on the modelization of pollen transport [58], studies on the concept of delaying ordinary differential equations to model a plant-pollinator system [59,94], a study on adult and juvenile pollinators [104], a study on the idealization of bumble bees [56], studies on the application of stochastic differential equations [18,109], a study on the analysis of flowering [29], studies on the modellization by hybrid ordinary differential equations and partial differential equations [53,60], a study on a particular form of ordinary differential system for modeling genotypes [57], and an empirical study which developed data fitting for ordinary differential models [66].

3.5. A Summary of the Topics Studied in the Retained List

The analysis and main results of the articles of the retained list focused on the following seven topics:

- (1)

- Positive bounded solutions: The variables of the mathematical models are the population or the density of the population. Then, the first question of the consistence of the mathematical model with the biological system is for analyzing if the mathematical model’s solutions are positive and bounded. In this sense, the following works [15,19,20,26,28,30,41,50,54,59,65,66,71,75,78,93,102] have explicit results proving that the dynamics of the mathematical systems have positive bounded solutions.

- (2)

- Equilibrium and stability analysis: In the mathematical analysis of dynamical systems, the study of linearization and asymptotic behavior is strongly related to the analysis of stability analysis. In particular, mathematical models are an important tool for characterizing the large time behavior of the system and answering other important questions, like the prevalence or extinction a species of pollinator. The works focused on the development of equilibrium and stability analysis are the following [10,11,12,14,15,19,20,22,26,33,34,36,39,43,44,45,46,47,48,54,55,57,60,61,63,67,68,70,71,73,74,75,76,78,79,81,84,86,90,91,92,93,95,96,98,100,102,103,104,107,111,113,114].

- (3)

- Bifurcation: One topic related to equilibrium and stability analysis is bifurcation analysis. Indeed, the analysis of bifurcation was introduced in [16,30,53,67,74,94,103,106,107,114].

- (4)

- Mutualistic interactions: In the case of mathematical models based on networks and patch concepts, there are several topics which have been researched, including coexistence [13,16,18,21,24,25,28,30,33,35,37,39,40,43,44,45,46,51,52,53,54,62,64,65,68,69,70,71,72,80,81,82,92,96,97,99,100,101,103,108], dissipation [28,33,34,48,74,78,94], and eco-evolution [59,67,68,94].

- (5)

- Periodicity of the solution: An interesting question for pollinators strongly related with seasonality is what the periodicity behavior of the populations of the different variables involved in pollination models is. Indeed, the following topics have been researched: periodic orbits [30,47,65,93], non-periodic orbits [28,45,48,65,74], and oscillation [30,53,63].

- (6)

- Numerical solutions and comparison with empirical data: The mathematical models are strongly nonlinear, and the analytical solution cannot be construed. Consequently, numerical solutions of the mathematical models are introduced in order to simulate and calibrate the mathematical models. In the retained list, the authors of [19,25,26,31,32,35,36,37,42,53,56,57,58,60,61,66,67,68,69,75,78,84,85,87,88,89,90,92,94,96,98,99,100,101,103,104,105,106,108,110,111,113,115,116] developed numerical simulations.

- (7)

- Mathematical control: Optimal control of the pollination systems via introducing appropriate control variables was conducted in [88,97].

4. Biological and Applied Problem Typologies in the Retained Literature

The retained articles address a spectrum of biological and applied problems through mathematical modeling. These can be categorized into seven thematic domains, each reflecting distinct modeling priorities, parametrization strategies, and implications for ecological policy and management:

- (1)

- Biological consistency and population viability: In this group, we consider the works addressing biological realism in population dynamics and focus on the research of positive bounded solutions. Models in this category ensure that population variables remain biologically meaningful, i.e., non-negative and bounded over time. This foundational consistency is critical for validating ecological interpretations and avoiding spurious predictions. Parametrization typically involves biologically constrained initial conditions and growth functions (e.g., logistic or saturating terms). These models support policy decisions related to conservation thresholds and population viability. Representative works include [15,19,20,26,28,30,41,50,54,59,65,66,71,75,78,93,102].

- (2)

- Long-term dynamics and species persistence: In this group, the problems to study are prevalence, extinction, and asymptotic behavior. These studies examine the conditions under which pollinator populations persist or collapse, often through linearization techniques and Lyapunov-based stability criteria. Parametrization emphasizes sensitivity to reproductive rates, mortality, and interaction coefficients. The results inform long-term sustainability planning and resilience forecasting. Representative works include [10,11,12,14,15,19,20,22,26,33,34,36,39,43,44,45,46,47,48,54,55,57,60,61,63,67,68,70,71,73,74,75,76,78,79,81,84,86,90,91,92,93,95,96,98,100,102,103,104,107,111,113,114].

- (3)

- Regime shifts and critical transitions: In this group of works, the authors focus on the bifurcation analysis and address the study of threshold phenomena and qualitative change. Bifurcation studies identify parameter regimes where small changes induce qualitative shifts in system behavior, such as transitions from coexistence to extinction. These models often employ continuation methods and bifurcation diagrams to explore critical thresholds, with implications for adaptive management and early warning indicators. Representative works include [16,30,53,67,74,94,103,106,107,114].

- (4)

- Mutualism and network structure: In this group, the focus is mutualistic interactions and the study of phenomena like coexistence, dissipation, and eco-evolutionary dynamics. These models incorporate spatial structure, network topology, and evolutionary feedback to explore how mutualistic systems maintain biodiversity. Parametrization includes patch-based connectivity, trait evolution, and interaction matrices. The findings support the design of pollinator corridors, agroecological zoning, and biodiversity incentives. Representative works include [13,16,18,21,24,25,28,30,33,35,37,39,40,43,44,45,46,51,52,53,54,62,64,65,68,69,70,71,72,80,81,82,92,96,97,99,100,101,103,108], as well as dissipation-focused studies [28,33,34,48,74,78,94], and eco-evolutionary dynamics studies [59,67,68,94].

- (5)

- Seasonal and oscillatory behavior: The addressed problem is the temporal variability and seasonality, along with the study of periodicity and oscillations in model solutions. Models in this group address how seasonal forcing and intrinsic dynamics lead to periodic or chaotic population fluctuations. Parametrization incorporates time-dependent coefficients and delay terms. These insights guide seasonal pollination services, crop planning, and phenological synchronization. Representative works include [28,30,45,47,48,53,63,65,74,93].

- (6)

- Simulation and empirical calibration: In this group, we consider works focused on numerical solutions and data comparison and developed for model validation and empirical integration. Due to nonlinear complexity, many models rely on numerical simulations to explore parameter spaces and fit empirical data. Parametrization strategies include optimization techniques, sensitivity analysis, and empirical calibration. These models enhance the credibility of model-based recommendations and support data-driven decision making. Representative works include [19,25,26,31,32,35,36,37,42,53,56,57,58,60,61,66,67,68,69,75,78,84,85,87,88,89,90,92,94,96,98,99,100,101,103,104,105,106,108,110,111,113,115,116].

- (7)

- Intervention and optimization: There are some works on solving the problem of applied control and resource allocation, which are focused on mathematical control. These studies introduce control variables—such as habitat enhancement or pesticide reduction—to optimize ecological outcomes. Parametrization uses Pontryagin’s maximum principle or dynamic programming to derive optimal strategies. The results directly inform cost-effective conservation and adaptive management protocols (see [88,97]).

5. Other Aspects of the Literature Review

5.1. Research Gaps and Future Directions for Control, Stochastic Modeling, and Network-Based PDEs

Despite the breadth of topics addressed in the retained literature, three modeling domains remain notably underdeveloped: (1) optimal control under uncertainty, (2) stochastic ecological modeling, and (3) network- or patch-based partial differential equations (PDEs) for spatially structured systems. These gaps are particularly relevant given the increasing complexity of ecological systems and the need for robust, data-informed decision making:

- (1)

- Optimal Control under Uncertainty: While mathematical control was explored in [88,97], current models rely on deterministic frameworks and assume full observability of system states and parameters. These assumptions limit applicability in real-world settings, where ecological responses to interventions (e.g., pesticide reduction or habitat restoration) are uncertain and data are sparse. Neither study incorporated stochastic perturbations or feedback mechanisms, nor did they address parameter uncertainty or adaptive control strategies. This restricts the robustness and generalizability of the proposed solutions.

- (2)

- Stochastic Modeling: Across the retained list, stochastic formulations are conspicuously absent. Although several studies addressed oscillatory behavior and bifurcation phenomena (e.g., [30,53,63]), they did so within deterministic systems. The lack of stochastic differential equations or probabilistic transitions limits the capacity to model demographic noise, environmental variability, and uncertainty propagation, especially in fragmented landscapes or under climate stress. This gap is critical given the increasing emphasis on resilience and risk-aware ecological planning.

- (3)

- Network-Based PDEs and Patch Dynamics: Numerous studies incorporated network or patch structures in mutualistic systems (e.g., [13,21,28,33,40,65,71,72,96,100]), yet most relied on discrete or compartmental models. Continuous-space PDEs on networks or graph-based domains are rare, and when present, they often lack empirical calibration or realistic topologies. For example, the authors of [28,48,74] explored dissipation and spatial dynamics but did not integrate high-resolution landscape data or adaptive dispersal mechanisms. This limits the ecological realism and policy relevance of spatial predictions.

5.2. Limitations of Current Findings

Across these domains, a recurring limitation is the scarcity of longitudinal, high-resolution data for model calibration and validation. Many studies rely on synthetic simulations (e.g., [67,68,69,75,78]) or static parameter estimates, which constrain ecological realism and hinder generalization across systems. Furthermore, sensitivity analysis and uncertainty quantification are rarely formalized, reducing the interpretability and robustness of model outcomes. Additionally, we report at least three limitations of this research: a checklist for data extraction was not constructed, only two databases were considered, and the analysis of data was developed without using advanced methodologies.

5.3. Methodological Pathways

To address these gaps, future research should pursue hybrid frameworks that integrate stochasticity into control models (e.g., stochastic optimal control or robust model predictive control), and embed network-aware partial differential equations within empirically grounded landscapes. Promising techniques include the following:

- (1)

- Graph Laplacians and metapopulation partial differential equations for dispersal modeling;

- (2)

- Bayesian inference and ensemble simulations for uncertainty quantification;

- (3)

- Data assimilation methods for real-time calibration.

5.4. Potential Data Sources

Empirical grounding can be strengthened using the following:

- (1)

- Remote sensing data for habitat fragmentation and land use change;

- (2)

- Citizen science platforms (e.g., iNaturalist or eBird) for species occurrence;

- (3)

- Long-term ecological monitoring networks (e.g., Global Biodiversity Information Facility—GBIF, or Long Term Ecological Research—LTER) for population dynamics.

5.5. Roadmap for Future Work

A strategic agenda should include the following:

- (1)

- Development of modular, interoperable modeling platforms that integrate control, stochasticity, and spatial structure;

- (2)

- Co-design of models with stakeholders to ensure contextual relevance and usability;

- (3)

- Formal incorporation of sensitivity analysis and uncertainty quantification;

- (4)

- Establishment of typological benchmarks to compare model performance across ecological and socio-political scenarios.

Such efforts will enhance both theoretical rigor and translational impact, positioning mathematical ecology as a key contributor to adaptive management and evidence-based policy design.

5.6. Implications of the Retained Modeling Topics for Agricultural Planning, Habitat Management, and Pesticide Regulation

The seven modeling themes identified in Section 3.5 provide a rigorous mathematical foundation for informing real-world decision making in agroecological systems. Their relevance extends to agricultural planning, habitat conservation, and the formulation of pesticide policies. Below, we detail the practical implications of each topic:

- (1)

- Positive Bounded Solutions: Ensuring that model solutions remain positive and bounded is essential for biological realism, particularly when variables represent population densities. This property supports the development of ecologically valid simulations that can guide agricultural interventions and pesticide thresholds, preventing unintended population collapses.

- (2)

- Equilibrium and Stability Analysis: Stability analysis enables the characterization of long-term system behavior, including species persistence or extinction. In agricultural contexts, it informs crop-pollinator compatibility and resilience, while in habitat management, it supports the design of restoration strategies and ecological corridors.

- (3)

- Bifurcation Analysis: Bifurcation theory reveals how small parameter changes can induce qualitative shifts in system dynamics. This is critical for anticipating nonlinear responses to environmental stressors, such as pesticide application or habitat fragmentation, and for designing adaptive management strategies that avoid tipping points.

- (4)

- Mutualistic Interactions: Modeling mutualistic networks elucidates mechanisms of coexistence, dissipation, and eco-evolutionary dynamics. These insights inform the diversification of cropping systems, the conservation of keystone mutualists, and the regulation of agrochemicals that may disrupt ecological interactions.

- (5)

- Periodicity of Solutions: Seasonal and periodic behaviors in pollinator populations are central to synchronizing agricultural calendars with ecological cycles. Understanding periodicity aids in optimizing planting schedules, flowering periods, and pesticide applications to align with pollinator activity.

- (6)

- Numerical Simulations and Empirical Validation: Given the nonlinear nature of most models, numerical simulations are indispensable for calibration and scenario testing. These simulations support evidence-based agricultural planning and policy evaluation, enabling cost-benefit analyses of proposed interventions.

- (7)

- Mathematical Control: Optimal control frameworks allow for the strategic modulation of system variables to achieve desired ecological or economic outcomes. In agriculture, this translates to resource-efficient practices that sustain pollinator populations, while in regulatory contexts, it supports dynamic policy design responsive to ecological feedback.

Collectively, these modeling approaches bridge theoretical ecology with applied decision making, offering quantitative tools for sustainable land use, biodiversity conservation, and environmental governance.

5.7. A Particular Comparative Analysis

In this subsection we develop a comparative analysis between [74] and the Thematic Synthesis in Section 3.5.

The authors of [74] offered a focused and technically rigorous contribution to the mathematical modeling of ecological systems, particularly in the context of bifurcation analysis, dissipative dynamics, and non-periodic oscillatory behavior. Chen’s work employed nonlinear differential equations to explore critical transitions and qualitative shifts in population dynamics, with emphasis on parameter sensitivity and system resilience. The model demonstrates how small perturbations can lead to significant changes in ecological outcomes, contributing to the literature on regime shifts and early warning indicators.

However, when compared with the broader synthesis presented in Section 3.5, the scope of [74] appears more specialized and thematically constrained. The retained literature encompassed seven interrelated modeling domains, ranging from positive boundedness and stability analysis to mutualistic networks, seasonality, empirical calibration, and optimal control. This thematic architecture enables a more comprehensive understanding of pollinator dynamics and ecological decision making.

Notably, the synthesis in Section 3.5 integrates multiple methodological layers:

- It links biological realism (e.g., positive bounded solutions [15,19]) with long-term system behavior (e.g., stability analysis [10,44]).

- It incorporates spatial and network structure in mutualistic interactions [21,33], extending beyond the local dynamics emphasized in [74].

- It addresses empirical calibration and numerical simulation [68,75], which are not central in Chen’s formulation.

- It introduces optimal control frameworks [88,97], offering policy-relevant strategies absent in [74].

In this light, the novelty of Section 3.5 lies in its integrative typology, which not only categorizes the retained studies but also reveals methodological synergies and thematic gaps. While [74] contributes valuable insights into bifurcation and dissipation phenomena, the broader synthesis provides a multidimensional roadmap for future research—bridging theoretical modeling with empirical validation and policy design.

This comparative perspective underscores the importance of typological frameworks in advancing ecological modeling, enabling researchers to situate individual studies within a structured landscape of methodological and applied relevance.

6. Conclusions

In this paper, we applied a systematic bibliographic review. Our research methodology adeptly allowed us to identify and analyze a substantial body of research on the mathematical modeling of pollinators. We retrieved and reviewed 107 works published between 1981 and 2025, leveraging databases such as the Web of Science and Mathscinet. We examined the mathematical theory and the topics analyzed. Our findings reveal a significant increase in research dedicated to the introduction or improvement of mathematical modeling to study the dynamics of pollinators. The landscape of mathematical modeling of pollinators has covered the standard topics of dynamical systems, like equilibrium and stability analysis. However, in recent years, the field has shifted dramatically, moving away to include some new topics like the fractional-order or diffusion models. In particular, modeling by using networks has promise in the future development of research. Moreover, given that the mathematical models arise from different mathematical approaches, it is essential to use an interdisciplinary approach for constructing complex models that more closely resemble pollination phenomena.

Research on the mathematical modeling of pollinators is an active area. However, there is still much to be developed in the context of addressing the challenges of pollination dynamics. We identified four issues that require further detailed exploration. First, there is the study of mathematical control theory about biological control. We identified only two works related to control theory (see [88,97]). Therefore, constructing mathematical models that incorporate the principles of optimal control is necessary. Second, the development of stochastic models is an area that needs strong attention from researchers. Third, the inclusion of network and patch concepts with mathematical models based on partial differential equations is a topic that requires attention and future development. Fourth, we reduced the present analysis to the word pollinators and two databases. Clearly, some representative works researching mathematical models for pollinators were excluded. We plan to expand our search to other specific pollinators and to other bibliographic databases, including Scopus, PubMed, BIOSIS Previews, and AGRICOLA.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.H. and A.C.; methodology, F.H. and A.C.; software, E.L. and J.T.; validation, E.L. and J.T.; formal analysis, F.H., A.C. and E.L.; investigation, F.H. and A.C.; resources, F.H. and A.C.; data curation, E.L.; writing—original draft preparation, F.H. and A.C.; writing—review and editing, F.H., A.C. and E.L.; visualization, F.H. and A.C.; supervision, F.H. and A.C.; project administration, F.H. and A.C.; funding acquisition, F.H. and A.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Agency for Research and Development, ANID-Chile, through FONDECYT project 1230560, and the Project supported by the Competition for Research Regular Projects, year 2023, code LPR23-03, Universidad Tecnológica Metropolitana. A. C. was funded by the Universidad del Bío–Bío through projects FAPEI FP2510413 and RE2547710.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Details on Counting the Regions

In order to count the regions, we considered the affiliations declared by the authors. For instance, in [10], the authors, Soberon and Rio, declared Mexico as their affiliation, and in [11], the author, Wells, declared USA for the affiliation. Extensive details for the retained list are presented on Table A1. We note that in the case of the same author declaring multiple affiliations, we considered only the first declared region.

Table A1.

Affiliations of the authors declared on the retained list. Here, RR stands for retained reference.

Table A1.

Affiliations of the authors declared on the retained list. Here, RR stands for retained reference.

| RR | Affiliations | RR | Affiliations | RR | Affiliations | RR | Affiliations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [10] | Mexico (2) | [37] | USA (2), China (2) | [64] | China (1) | [91] | USA (4) |

| [11] | USA (1) | [38] | Australia (3) | [65] | USA (4), China (2), UK (1) | [92] | China (3) |

| [12] | USA (1) | [39] | Netherlands (2), France (1) | [66] | Spain (4) | [93] | USA (6) |

| [13] | USA (2) | [40] | Ecuador (1), Spain (2) | [67] | Mexico (2) | [94] | China (4) |

| [14] | Sweden (2) | [41] | USA (5), Brazil (1) | [68] | Australia (1), UK (1) | [95] | China (1), Brazil (1), Netherlands (1), France (1), Spain (4) |

| [15] | USA (1) | [42] | Mexico (3) | [69] | R. of Korea (3) | [96] | Germany (4) |

| [16] | Italy (1) | [43] | Mexico (1) | [70] | China (1) | [97] | India (3) |

| [17] | UK (3) | [44] | China (2) | [71] | China (1) | [98] | USA (2) |

| [18] | USA (2) | [45] | China (2) | [72] | USA (1) | [99] | China (2) |

| [19] | Mexico (2) | [46] | China (1), USA (2) | [73] | Czech Republic (2) | [100] | Japan (2) |

| [20] | Argentina (2) | [47] | Mexico (2) | [74] | China (3) | [101] | India (3) |

| [21] | Chile (5) | [48] | China (3) | [75] | India (2) | [102] | USA (4) |

| [22] | Israel (2) | [49] | USA (4) | [76] | China (2), USA (1) | [103] | Czech Republic (3) |

| [23] | UK (3), Canada (1), USA (1) | [50] | China (3) | [77] | China (3) | [104] | Bulgaria (3) |

| [24] | Germany (2) | [51] | France (2) | [78] | China (4) | [105] | South African (2), Netherlands (1) |

| [25] | Argentina (2), Germany (1) | [52] | South African (2) | [79] | India (2) | [106] | India (2) |

| [26] | Mexico (2) | [53] | China (1), France (1), USA (1) | [80] | China (3), USA (2) | [107] | Mexico (3) |

| [27] | Canada (3) | [54] | Ecuador (1), Spain (2) | [81] | USA (2), France (1), Switzerland (1) | [108] | South Africa (4) |

| [28] | China (1), USA (3) | [55] | Mexico (2) | [82] | USA (6), UK (1) | [109] | Netherlands (2), Canada (1) |

| [29] | USA (4) | [56] | USA (5), Sweden (2) | [83] | USA (6), New Zeland (6) | [110] | Japan (3) |

| [30] | China (3) | [57] | Canada (2), Australia (2) | [84] | Saudi Arabia (2), Mexico (1), Pakistan (1) | [111] | China (4) |

| [31] | USA (1) | [58] | Belgium (2), Canada (2), Netherlands (1) | [85] | USA (6) | [112] | China (2) |

| [32] | USA (3) | [59] | China (2), USA (1) | [86] | Czech Republic (3) | [113] | Czech Republic (1) |

| [33] | China (2) | [60] | Japan (1) | [87] | USA (3) | [115] | China (1), Canada (1) |

| [34] | China (1) | [61] | South Africa (1), France (2) | [88] | Spain (2), Hungary (6) | [114] | India (3) |

| [35] | Chile (3), USA (1) | [62] | Czech Republic (2) | [89] | Italy (4), Germany (7) | [116] | Czech Republic (1) |

| [36] | UK (5) | [63] | Mexico (2) | [90] | USA (4) |

Appendix B. Details on Journals for Retained List

We identified the journals and searched for the impact factor, H index and quartiles, which are presented in Table A2.

Table A2.

List of the journals appearing in the retained reference list.

Table A2.

List of the journals appearing in the retained reference list.

| Journal | H Index | SJR | Quartile |

|---|---|---|---|

| Agronomy-Basel | 114 | 3.7 | Q1 |

| Alexandria Engineering Journal | 112 | 5.6 | Q1 |

| American Naturalist | 236 | 3 | Q2 |

| Annals of Botany | 215 | 4.1 | Q1 |

| Applied Ecology and Environmental Research | 48 | 0.9 | Q4 |

| Applied Mathematical Modelling. Simulation and Computation for Engineering and Environmental Systems | 150 | 4.2 | Q1 |

| Applied Mathematics and Computation | 182 | 3.1 | Q1 |

| Applied Sciences-Basel | 162 | 2.7 | Q2 |

| Biosystems | 85 | 0.392 | Q2 |

| Boletín de la Sociedad Matemática Mexicana. Third Series | 20 | 0.414 | Q2 |

| Bulletin of Mathematical Biology | 101 | 0.702 | Q1 |

| Chaos, Solitons & Fractals | 175 | 1.184 | Q1 |

| Chaos. An Interdisciplinary Journal of Nonlinear Science | – | – | – |

| Communications in Nonlinear Science and Numerical Simulation | 143 | 0.956 | Q1 |

| Discrete and Continuous Dynamical Systems. Series A | 80 | 1.065 | Q1 |

| Discrete and Continuous Dynamical Systems. Series B. A Journal Bridging Mathematics and Sciences | 65 | 0.735 | Q1 |

| Discrete and Continuous Dynamical Systems. Series S | 43 | 0.514 | Q2 |

| Ecological Modelling | 189 | 0.896 | Q1 |

| Ecological Research | 87 | 0.616 | Q2 |

| Ecology | 345 | 5.5 | Q1 |

| Ecology and Evolution | 109 | 0.858 | Q1 |

| Ecology Letters | 330 | 9.8 | Q1 |

| European Journal of Applied Mathematics | 53 | 0.750 | Q2 |

| Evolution | 227 | 3.4 | Q2 |

| Evolutionary Applications | 95 | 1.362 | q1 |

| Evolutionary Ecology | 96 | 0.645 | Q2 |

| Evolutionary Ecology Research | 82 | – | – |

| International Journal for Parasitology-Parasites and Wildlife | 44 | 0.618 | Q1 |

| International Journal of Bifurcation and Chaos in Applied Sciences and Engineering | 120 | 0.596 | Q1 |

| International Journal of Biomathematics | 38 | 0.527 | Q2 |

| Journal of Applied Ecology | 216 | 6.2 | Q1 |

| Journal of Biological Dynamics | 46 | 0.597 | Q2 |

| Journal of Biological Systems | 39 | 0.487 | Q2 |

| Journal of Ecology | 219 | 6.1 | Q1 |

| Journal of Evolutionary Biology | 148 | 0.921 | Q1 |

| Journal of Mathematical Biology | 111 | 0.921 | Q1 |

| Journal of Mathematics | 30 | 0.322 | Q3 |

| Journal of Statistical Mechanics: Theory and Experiment | 95 | 0.373 | Q3 |

| Journal of the European Mathematical Society | 68 | 3.043 | Q1 |

| Journal of the Royal Society Interface | 177 | 1.025 | Q1 |

| Journal of Theoretical Biology | 178 | 0.532 | Q2 |

| Lobachevskii Journal of Mathematics | 31 | 0.435 | Q2 |

| Mathematical Biosciences | 114 | 0.555 | Q2 |

| Mathematical Methods in the Applied Sciences | 87 | 1.991 | Q1 |

| Modeling Earth Systems and Environment | 66 | 0.654 | Q1 |

| Natural Resource Modeling | 38 | 0.521 | Q2 |

| Nonlinear Analysis. Real World Applications. An International Multidisciplinary Journal | 106 | 1.168 | Q1 |

| Nonlinear Studies. The International Journal | 22 | 0.229 | Q4 |

| Oikos | 210 | 1.438 | Q1 |

| Physica A. Statistical Mechanics and its Applications | 195 | 0.669 | Q2 |

| Physica D: Nonlinear Phenomena | 154 | 0.940 | Q1 |

| PLoS ONE | 467 | 3.3 | Q1 |

| PLoS Pathogens | 260 | 5.5 | Q1 |

| Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America | 896 | 10.8 | Q1 |

| Royal Society Open Science | 92 | 0.795 | Q1 |

| Scientific Reports | 347 | 4.3 | Q1 |

| Theoretical Ecology | 45 | 0.524 | Q2 |

| Theoretical Population Biology | 99 | 0.563 | Q2 |

References

- Potts, S.G.; Imperatriz-Fonseca, V.L.; Ngo, H.T. IPBES the Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services on Pollinators, Pollination and Food Production; Secretariat of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services: Bonn, Germany, 2017; p. 552. [Google Scholar]

- Deeksha, M.G.; Khan, M.S.; Kumaranag, K.M. Cuphea hyssopifolia Kunth: A Potential Plant for Conserving Insect Pollinators in Shivalik Foot Hills of Himalaya. Nat. Acad. Sci. Lett. 2023, 46, 137–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devillers, J. In Silico Bees; Taylor & Francis, CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Winston, M.L. The Biology of the Honey Bee; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Karlin, S.; Farkash, S. Some Multiallele Partial Assortative Mating Systems for a Polygamous Species. Theoret. Popul. Biol. 1978, 14, 446–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belsare, P.V.; Sriram, B.; Watve, M.G. The Co-optimization of Floral Display and Nectar Reward. J. Biosci. 2009, 34, 963–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; DeGrandi-Hoffman, G.; Ratti, V.; Kang, Y. Review on mathematical modeling of honeybee population dynamics. Math. Biosci. Eng. 2021, 18, 9606–9650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozada, E.; Guerrero-Ortiz, C.; Coronel, A.; Medina, R. Classroom Methodologies for Teaching and Learning Ordinary Differential Equations: A Systemic Literature Review and Bibliometric Analysis. Mathematics 2021, 9, 745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, K.S.; Kunz, R.; Kleijnen, J.; Antes, G. Five Steps to Conducting a Systematic Review. J. R. Soc. Med. 2003, 96, 118–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soberon, J.; Rio, C. The Dynamics of a Plant-Pollinator Interaction. J. Theoret. Biol. 1981, 91, 363–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, H. Population Equilibria and Stability in Plant-Animal Pollination Systems. J. Theoret. Biol. 1983, 100, 685–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, R. A Patch Model of Mutualism. J. Theoret. Biol. 1987, 125, 243–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastings, A.; Wolin, C.L. Within-Patch Dynamics in a Metapopulation. Ecology 1989, 70, 1261–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingvarsson, P.K.; Lundberg, S. The Effect of a Vector-Borne Disease on the Dynamics of Natural Plant-Populations—A Model for Ustilago-Violacea Infection of Lychnis-Viscaria. J. Ecol. 1993, 81, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, S. Dynamics of Herbivore-Plant-Pollinator Models. J. Math. Biol. 2002, 44, 129–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dercole, F. Border Collision Bifurcations in the Evolution of Mutualistic Interactions. Int. J. Bifurc. Chaos 2005, 15, 2179–2190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart-Cox, J.; Britton, N.; Mogie, M. Pollen Limitation or Mate Search Need not Induce an Allee Effect. Bull. Math. Biol. 2005, 67, 1049–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.A.; Wilson, W.G. Evolutionarily Stable Dispersal with Pattern Formation in a Mutualist-Antagonist System. Evol. Ecol. Res. 2007, 9, 987–1004. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Garduño, F.; Breña-Medina, V.E. Spatio-Temporal Dynamics of a Three Interacting Species Mathematical Model Inspired in Physics. In Proceedings of the AIP Conference Proceedings, Ponta Delgada, Portugal, 18–23 May 2008; Dagdug, L., Scherer, L.G.C., Eds.; Universidad Autonoma Metropolitana: Mexico City, Mexico, 2008; Volume 978, pp. 115–134. [Google Scholar]

- Momo, F.R.; Ure, J.E. Stability and Fluctuations in a Three Species System: A Plant with Two Very Different Pollinators. Appl. Ecol. Environ. Res. 2009, 7, 287–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdovinos, F.S.; Ramos-Jiliberto, R.; Flores, J.D.; Espinoza, C.; Lópen, G. Structure and Dynamics of Pollination Networks: The Role of Alien Plants. Oikos 2009, 118, 1190–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishman, M.A.; Hadany, L. Plant-Pollinator Population Dynamics. Theor. Popul. Biol. 2010, 78, 270–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, T.J.; Shuker, D.M.; Colegrave, N.; Day, T.; Graham, A.L. The Coevolution of Virulence: Tolerance in Perspective. PLoS Pathog. 2010, 6, e1001006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oña, L.; Lachmann, M. Ant Aggression and Evolutionary Stability in Plant-Ant and Plant-Pollinator Mutualistic Interactions. J. Evol. Biol. 2011, 24, 617–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramson, G.; Soto, C.A.T.; Oña, L. The Role of Asymmetric Interactions on the Effect of Habitat Destruction in Mutualistic Networks. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e0021028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Garduño, F.; Breña-Medina, V. Searching for Spatial Patterns in a Pollinator-Plant-Herbivore Mathematical Model. Bull. Math. Biol. 2011, 73, 1118–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tyson, R.C.; Wilson, J.B.; Lane, W.D. Beyond Diffusion: Modelling Local and Long-Distance Dispersal for Organisms Exhibiting Intensive and Extensive Search Modes. Theor. Popul. Biol. 2012, 79, 70–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; DeAngelis, D.; Holland, J. Uni-Directional Interaction and Plant-Pollinator-Robber Coexistence. Bull. Math. Biol. 2012, 74, 2142–2164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilman, R.T.; Fabina, N.S.; Abbott, K.C.; Rafferty, N.E. Evolution of Plant-Pollinator Mutualisms in Response to Climate Change. Evol. Appl. 2012, 5, 2–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.S.; Wu, H.; Sun, S. Persistence of Pollination Mutualisms in Plant-Pollinator-Robber Systems. Theor. Popul. Biol. 2012, 81, 243–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, K.E. A Mathematical Model of the Interactions Between Pollinators and Their Effects on Pollination of Almonds. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Yong, K.E.; Li, Y.; Hendrix, S. Habitat Choice of Multiple Pollinators in Almond Trees and its Potential Effect on Pollen Movement and Productivity: A Theoretical Approach Using the Shigesada-Kawasaki-Teramoto Model. J. Theoret. Biol. 2012, 305, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wu, H. Invasibility of nectarless flowers in plant-pollinator systems. Bull. Math. Biol. 2013, 75, 1138–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y. Dynamics of plant-pollinator-robber systems. J. Math. Biol. 2013, 66, 1155–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdovinos, F.S.; de Espanes, P.M.; Flores, J.D.; Ramos-Jiliberto, R. Adaptive foraging allows the maintenance of biodiversity of pollination networks. Oikos 2013, 122, 907–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryden, J.; Gill, R.J.; Mitton, R.A.A.; Raine, N.E.; Jansen, V.A.A. Chronic Sublethal Stress Causes Bee Colony Failure. Ecol. Lett. 2013, 16, 1463–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holland, J.N.; Wang, Y.S.; Sun, S.; DeAngelis, D.L. Consumer-Resource Dynamics of Indirect Interactions in a Mutualism-Parasitism Food Web Module. Theor. Ecol. 2013, 6, 475–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoury, D.S.; Barron, A.B.; Myerscough, M.R. Modelling Food and Population Dynamics in Honey Bee Colonies. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e59084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Encinas-Viso, F.; Revilla, T.; Etienne, R. Shifts in Pollinator Population Structure may JeopardizePollination Service. J. Theoret. Biol. 2014, 352, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero, G.; Langa, J.; Suárez, A. Biodiversity and Vulnerability in a 3D Mutualistic System. Discret. Contin. Dyn. Syst. 2014, 34, 4107–4126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagan, W.F.; Bewick, S.; Cantrell, S.; Cosner, C.; Varassin, I.G.; Inouye, D.W. Phenologically Explicit Models for Studying Plant-Pollinator Interactions under Climate Change. Theor. Ecol. 2014, 7, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Garduño, F.; Castellanos, V.; Quilantán, I. Dynamics of a Nonlinear Mathematical Model for Three Interacting Populations. Bol. Soc. Mat. Mex. 2014, 20, 147–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas-De-León, C. Global Stability for Multi-Species Lotka-Volterra Cooperative Systems: One Hyper-Connected Mutualistic-Species. Int. J. Biomath. 2015, 8, 1550039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wu, H. Stability of Plant-Pollinator-Ant Co-Mutualism. Appl. Math. Comput. 2015, 261, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, S. Persistence of Pollination Mutualisms in the Presence of Ants. Bull. Math. Biol. 2015, 77, 202–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; DeAngelis, D.; Holland, J. Dynamics of an Ant-Plant-Pollinator Model. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 2015, 20, 950–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barradas, I.; Vázquez, V. Improving Pollination Through Learning. J. Biol. Syst. 2015, 23, S77–S90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.S.; Wu, H.; Wang, S.K. Invasibility of Nectar Robbers in Pollination-Mutualisms. Appl. Math. Comput. 2015, 250, 908–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jover, L.F.; Flores, C.O.; Cortez, M.H.; Weitz, J.S. Multiple Regimes of Robust Patterns between Network Structure and Biodiversity. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 17856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Jiang, H.; Li, Y. Positive Steady State Solutions of a Pant-Pollinator Model with Diffusion. Discret. Contin. Dyn. Syst. Ser. B 2015, 20, 1805–1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgelin, E.; Loeuille, N. Evolutionary Response of Plant Interaction Traits to Nutrient Enrichment Modifies the Assembly and Structure of Antagonistic-Mutualistic Communities. J. Ecol. 2016, 104, 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minoarivelo, H.O.; Hui, C. Invading a Mutualistic Network: To be or not to be Similar. Ecol. Evol. 2016, 6, 4981–4996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Magal, P.; Ruan, S. Oscillations in Age-Structured Models of Consumer-Resource Mutualisms. Discret. Contin. Dyn. Syst. Ser. B 2016, 21, 537–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero, G.; Langa, J.; Suárez, A. Architecture of attractor determines dynamics on mutualistic complex networks. Nonlinear Anal. Real World Appl. 2017, 34, 17–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez, V.; Barradas, I. Deceptive Pollination and Insects’ Learning: A Delicate Balance. J. Biol. Dyn. 2017, 11, 299–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, H.T.; Banks, J.E.; Bommarco, R.; Laubmeier, A.N.; Myers, N.J.; Rundlöf, M.; Tillman, K. Modeling Bumble Bee Population Dynamics with Delay Differential Equations. Ecol. Model. 2017, 351, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouhours, J.; Mesgaran, M.B.; Cousens, R.D.; Lewis, M.A. Neutral Hybridization Can Overcome a Strong Allee Effect by Improving Pollination Quality. Theor. Ecol. 2017, 10, 319–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallaeys, V.; Tyson, R.C.; Lane, W.D.; Deleersnijder, E.; Hanert, E. A Levy-Flight Diffusion Model to Predict Transgenic Pollen Dispersal. J. R. Soc. Interface 2017, 15, 20160889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Liu, Z.; Ruan, S. Bifurcation and Temporal Periodic Patterns in a Plant-Pollinator Model with Diffusion and Time Delay Effects. J. Biol. Dyn. 2017, 11, 138–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamauchi, A. Joint evolution of interspecific mutualism and regulation of variation of interaction under directional selection in trait space. Theor. Ecol. 2017, 10, 477–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumont, Y.; Soulie, J.; Michel, F. Modeling oil Palm Pollinator Dynamics using Deterministic and Agent-Based Approaches. Applications on Fruit Set Estimates. Some Preliminary Results. Math. Methods Appl. Sci. 2018, 41, 8545–8564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revilla, T.; Křivan, V. Competition, Trait-Mediated Facilitation, and the Structure of Plant-Pollinator Communities. J. Theoret. Biol. 2018, 440, 42–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez, V.; Barradas, I. A Plant-Pollinator System: How Learning Versus Cost-Benefit can Induce Periodic Oscillations. Int. J. Biomath. 2018, 11, 1850024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. Global Dynamics of a Competition-Parasitism-Mutualism Model Characterizing Plant-Pollinator-Robber Interactions. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2018, 510, 26–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.J.; Huang, Z.G.; Seager, T.P.; Lin, W.; Grebogi, C.; Hastings, A.; Lai, Y.C. Predicting Tipping Points in Mutualistic Networks through Dimension Reduction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, E639–E647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usó-Doménech, J.L.; Nescolarde-Selva, J.A.; Lloret-Climent, M.; González-Franco, L. Behavior of Pyrophite Shrubs in Mediterranean Terrestrial Ecosystems (i): Population and Reproductive Model. Math. Biosci. 2018, 297, 58–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellanos, V.; Sánchez-Garduño, F. The Existence of a Limit Cycle in a Pollinator-Plant-Herbivore Mathematical Model. Nonlinear Anal. Real World Appl. 2019, 48, 212–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cropp, R.; Norbury, J. Simulating Eco-Evolutionary Processes in an Obligate Pollination Model with a Genetic Algorithm. Bull. Math. Biol. 2019, 81, 4803–4820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeng, S.; Lee, J.; Lee, D. Competition-Induced Increase of Species Abundance in Mutualistic Networks. J. Stat. Mech. Theory Exp. 2019, 19, 033502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. Pollination-Mutualisms in a Two-Patch System with Dispersal. J. Theoret. Biol. 2019, 476, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. Dynamics of a Plant-Nectar-Pollinator Model and its Approximate Equations. Math. Biosci. 2019, 307, 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdovinos, F.S. Mutualistic Networks: Moving Closer to a Predictive Theory. Ecology Lett. 2019, 22, 1517–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krivan, V.; Revilla, T.A. Plant Coexistence Mediated by Adaptive Foraging Preferences of Exploiters or Mutualists. J. Theor. Biol. 2019, 480, 112–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, M.; Wu, H.; Wang, Y. Persistence and Oscillations of Plant-Pollinator-Herbivore Systems. Bull. Math. Biol. 2020, 82, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devi, S.; Mishra, R. A plant-pollinator-pesticide model. Nonlinear Stud. 2020, 27, 1003–1019. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Wu, H.; Wang, S. Persistence of Pollination Mutualisms under Pesticides. Appl. Math. Model. 2020, 77, 861–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Sun, S.; Wang, Y. Bifurcations in a Pollination-Mutualism System with Nectarless Flowers. Discret. Contin. Dyn. Syst.-S 2020, 13, 3213–3229. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, H.; Wang, Y.; Wu, H.; Wu, S. Persistence of Pollination-Mutualisms under the Effect of Intermediary Resource. Nat. Resour. Model. 2020, 33, e12259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devi, S.; Mishra, R.P. A Mathematical Model to See the Effects of Increasing Environmental Temperature on Plant-Pollinator Interactions. Model. Earth Syst. Environ. 2020, 6, 1315–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.X.; Liu, X.M.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, W.D.; Gao, J.X. Co-Adaptation Enhances the Resilience of Mutualistic Networks. J. R. Soc. Interface 2020, 17, 20200236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yule, K.M.; Johnson, C.A.; Bronstein, J.L.; Ferrière, R. Interactions among Interactions: The Dynamical Consequences of Antagonism between Mutualists. J. Theor. Biol. 2020, 501, 110334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueroa, L.L.; Grab, H.; Ng, W.H.; Myers, C.R.; Graystock, P.; McFrederick, Q.S.; McArt, S.H. Landscape Simplification Shapes Pathogen Prevalence in Plant-Pollinator Networks. Ecol. Lett. 2020, 23, 1212–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peace, A.; Pattemore, D.; Broussard, M.; Fonseka, D.; Tomer, N.; Bosque-Pérez, N.A.; Crowder, D.; Shaw, A.K.; Jesson, L.; Howlett, B.G.; et al. Orchard Layout and Plant Traits Influence Fruit Yield More Strongly than Pollinator Behaviour and Density in a Dioecious Crop. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0231120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Gómez-Aguilar, J.F.; Abdeljawad, T.; Khan, H. Stability and Numerical Simulation of a Fractional Order Plant-Nectar-Pollinator Model. Alex. Eng. J. 2020, 59, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnham, P.A.; Alger, S.A.; Case, B.; Boncristiani, H.; Hébert-Dufresne, L.; Brody, A.K. Flowers as Dirty Doorknobs: Deformed Wing Virus Transmitted between Apis Mellifera and Bombus Impatiens through Shared Flowers. J. Appl. Ecol. 2021, 58, 2065–2074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revilla, T.A.; Marcou, T.; Krivan, V. Plant Competition under Simultaneous Adaptation by Herbivores and Pollinators. Ecol. Model. 2021, 455, 109634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPeek, S.J.; Bronstein, J.L.; McPeek, M.A. The Evolution of Resource Provisioning in Pollination Mutualisms. Am. Nat. 2020, 198, 441–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández, F.J.; Garay, J.; Móri, T.F.; Csiszár, V.; Varga, Z.; López, I.; Gámez, M.; Cabello, T. Theoretical Foundation of the Control of Pollination by Hoverflies in a Greenhouse. Agronomy 2021, 11, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]