Investigating the Dynamic Variation of Skin Microbiota and Metabolites in Bats During Hibernation

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection

2.2. Pseudogymnoascus Destructans Detection

2.3. Bacterial DNA Extraction and Sequencing

2.4. Untargeted Metabolomics Sequencing

2.5. Microbial Data Analysis

2.6. Metabolomic Data Analysis

2.7. Integrated Analysis of Microbiota and Metabolites

2.8. Metabolite Validation Experiments

3. Results

3.1. Pseudogymnoascus Destructans Infection

3.2. Study on the Bacterial Community Structure of Bat Skin in Different Hibernation Stages

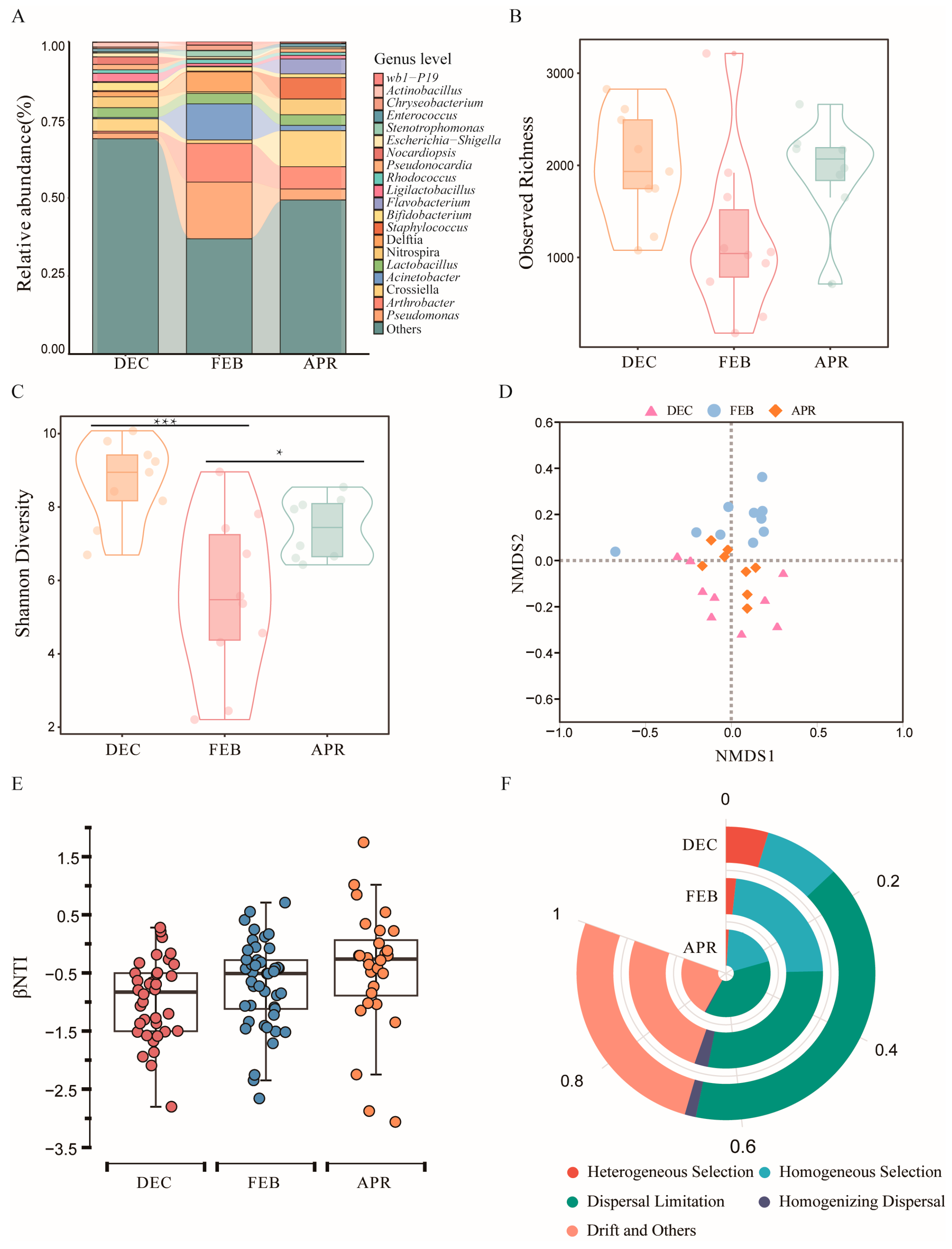

3.2.1. Changes in the Bacterial Community Composition of Bat Skin Across Hibernation Stages

3.2.2. Changes in the Bacterial Community Structure of Bat Skin Across Different Hibernation Stages

3.2.3. Drivers of Bacterial Community Assembly on Bat Skin During Hibernation

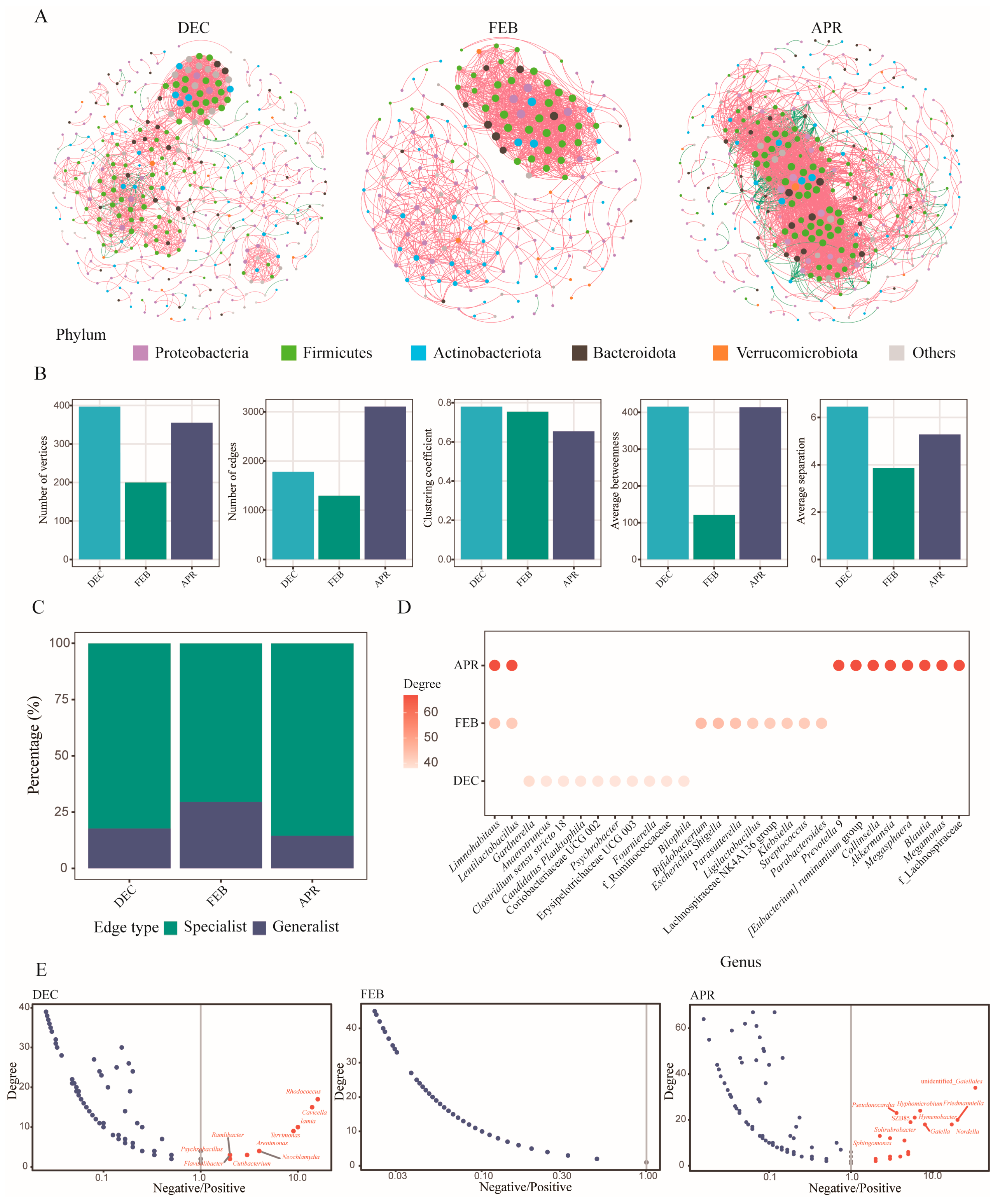

3.2.4. Co-Occurrence Network Analysis Revealed the Relationships Among Skin Bacterial Communities of Bats at Different Hibernation Stages

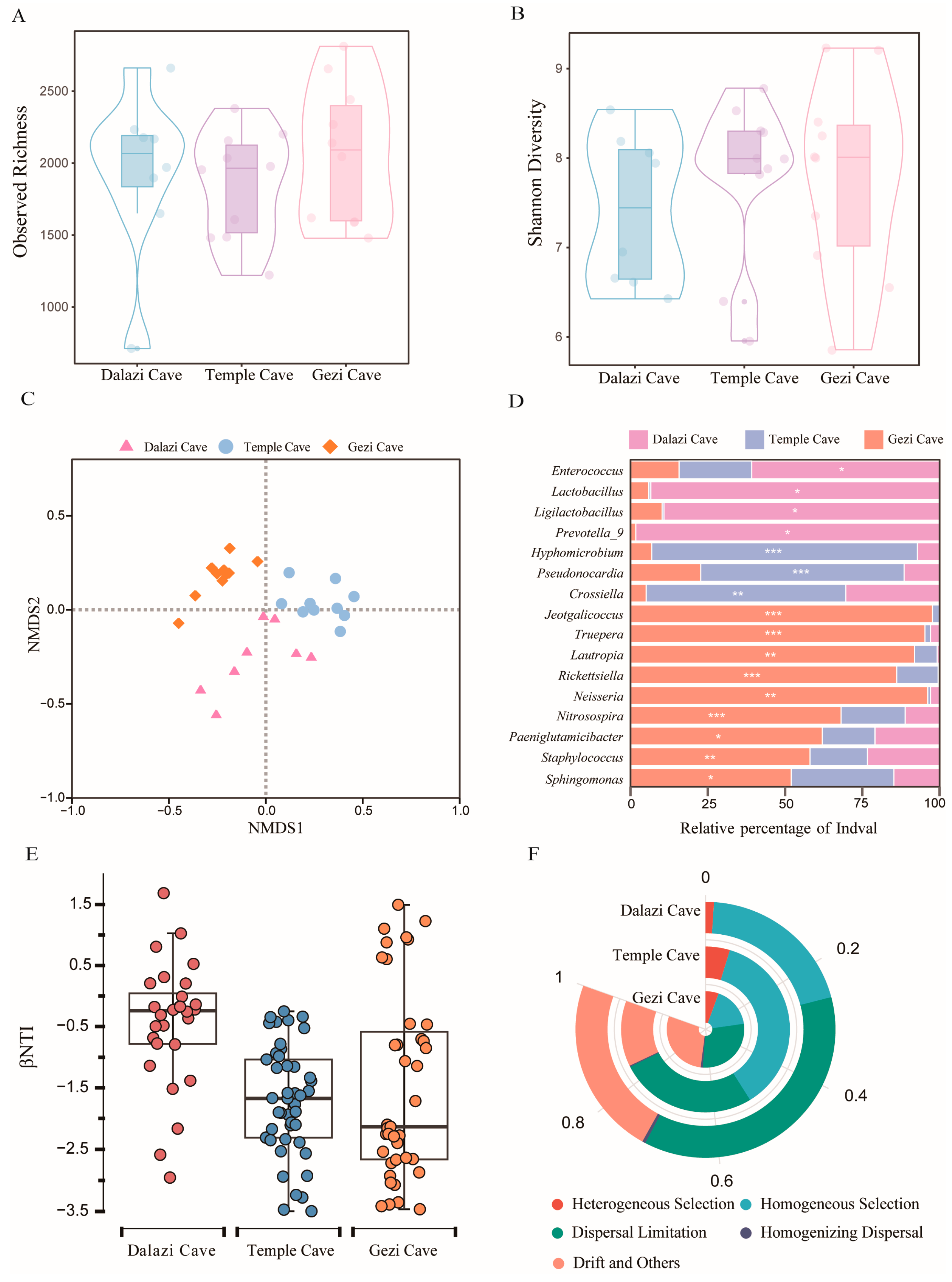

3.3. Changes in the Bacterial Community Structure of Bat Skin Across Different Locations

3.3.1. Variations in the Bacterial Community Composition of Bat Skin Among Locations

3.3.2. Variations in the Bacterial Community Structure of Bat Skin Among Locations

3.3.3. Driving Forces of Bacterial Community Assembly in Bat Skin Across Different Locations

3.3.4. Functional Differences in Bacterial Communities of Bat Skin Among Locations

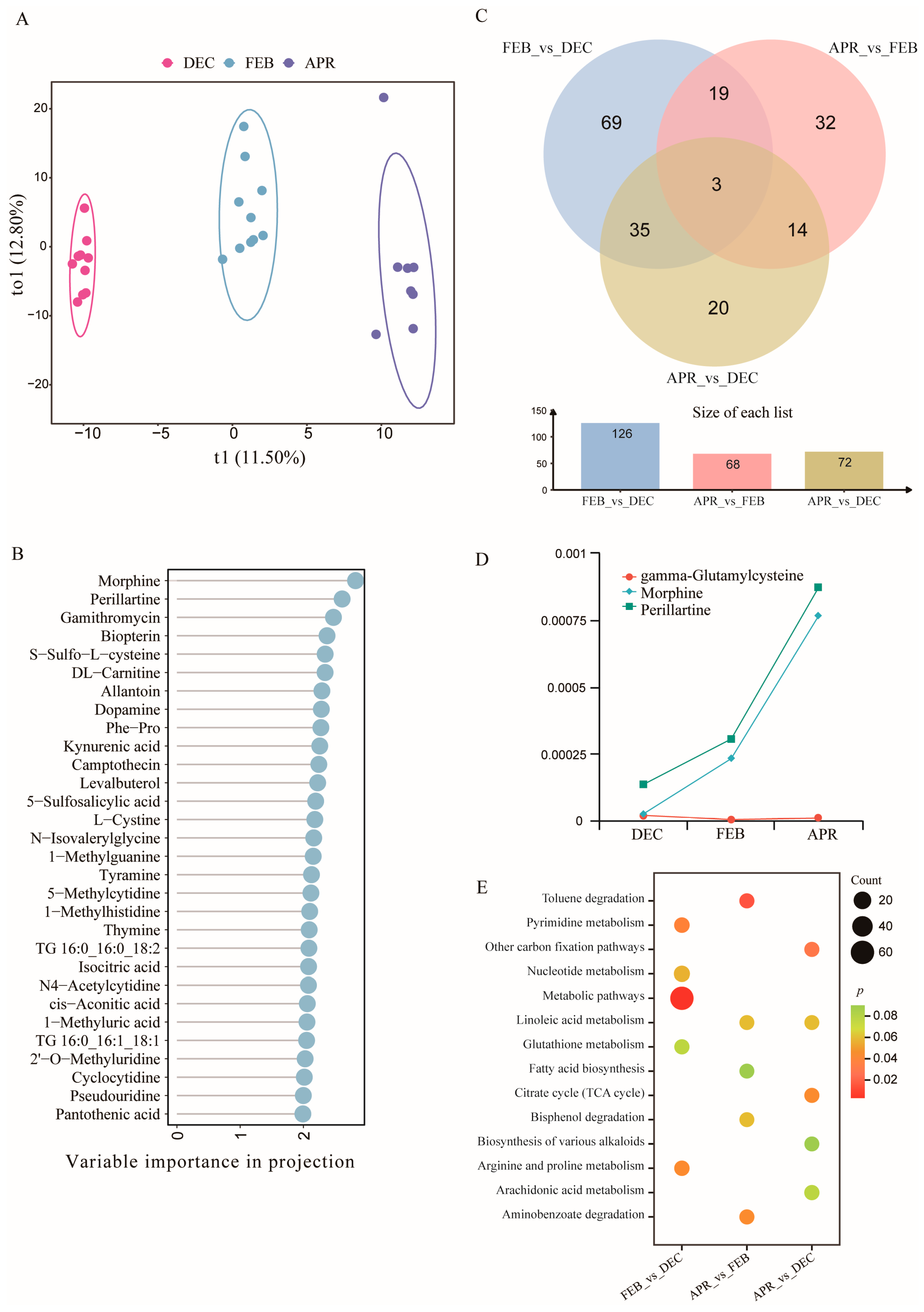

3.4. Study on Skin Metabolites of Bats During Different Hibernation Stages

3.4.1. Changes in Skin Metabolites of Bats Across Different Hibernation Stages

3.4.2. Detection of Differential Metabolites in Bat Skin at Different Hibernation Stages

3.5. Study on Skin Metabolites of Bats from Different Locations

3.5.1. Variations in Skin Metabolites Among Bats from Different Locations

3.5.2. Metabolite Clusters of Bat Skin in Different Locations

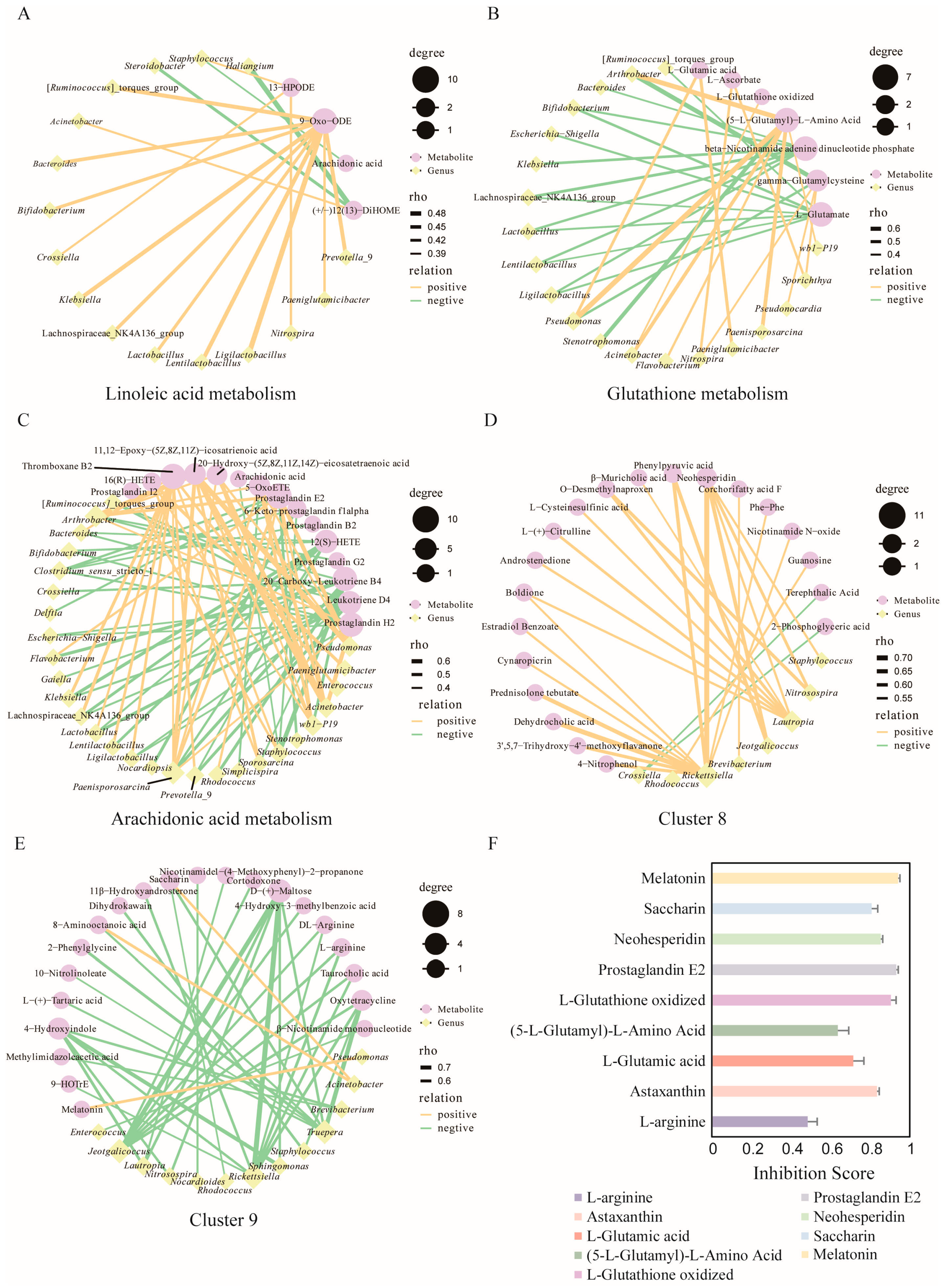

3.6. Joint Analysis of Bat Skin Microbes and Metabolites

3.6.1. Combined Analysis of Bat Skin Microbes and Metabolites During Hibernation

3.6.2. Combined Analysis of Bat Skin Microbiome and Metabolites Across Different Locations

3.7. Metabolite Inhibition Experiment

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kunz, T.H.; Braun de Torrez, E.; Bauer, D.; Lobova, T.; Fleming, T.H. Ecosystem services provided by bats. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2011, 1223, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minnis, A.M.; Lindner, D.L. Phylogenetic evaluation of Geomyces and allies reveals no close relatives of Pseudogymnoascus destructans, comb. nov., in bat hibernacula of eastern North America. Fungal Biol. 2013, 117, 638–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoyt, J.R.; Langwig, K.E.; Sun, K.; Lu, G.; Parise, K.L.; Jiang, T.; Frick, W.F.; Foster, J.T.; Feng, J.; Kilpatrick, A.M. Host persistence or extinction from emerging infectious disease: Insights from white-nose syndrome in endemic and invading regions. Proc. Biol. Sci. 2016, 283, 20152861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grice, E.A.; Segre, J.A. The skin microbiome. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2011, 9, 244–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenberg, E.; Zilber-Rosenberg, I. The hologenome concept of evolution after 10 years. Microbiome 2018, 6, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A.; Li, Z.; Dai, W.; Parise, K.L.; Leng, H.; Jin, L.; Liu, S.; Sun, K.; Hoyt, J.R.; Feng, J. Bacterial community dynamics on bats and the implications for pathogen resistance. Environ. Microbiol. 2022, 24, 1484–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemieux-Labonté, V.; Dorville, N.A.S.; Willis, C.K.R.; Lapointe, F.J. Antifungal Potential of the Skin Microbiota of Hibernating Big Brown Bats (Eptesicus fuscus) Infected with the Causal Agent of White-Nose Syndrome. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyt, J.R.; Cheng, T.L.; Langwig, K.E.; Hee, M.M.; Frick, W.F.; Kilpatrick, A.M. Bacteria isolated from bats inhibit the growth of Pseudogymnoascus destructans, the causative agent of white-nose syndrome. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0121329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A.; Li, Z.; Leng, H.; Jin, L.; Xiao, Y.; Sun, K.; Feng, J. Seasonal assembly of skin microbiota driven by neutral and selective processes in the greater horseshoe bat. Mol. Ecol. 2023, 32, 4695–4707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrd, A.L.; Belkaid, Y.; Segre, J.A. The human skin microbiome. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2018, 16, 143–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouslimani, A.; da Silva, R.; Kosciolek, T.; Janssen, S.; Callewaert, C.; Amir, A.; Dorrestein, K.; Melnik, A.V.; Zaramela, L.S.; Kim, J.N.; et al. The impact of skin care products on skin chemistry and microbiome dynamics. BMC Biol. 2019, 17, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afghani, J.; Traidl-Hoffmann, C.; Schmitt-Kopplin, P.; Reiger, M.; Mueller, C. An Overview of the Latest Metabolomics Studies on Atopic Eczema with New Directions for Study. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 8791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuehne, A.; Hildebrand, J.; Soehle, J.; Wenck, H.; Terstegen, L.; Gallinat, S.; Knott, A.; Winnefeld, M.; Zamboni, N. An integrative metabolomics and transcriptomics study to identify metabolic alterations in aged skin of humans in vivo. BMC Genom. 2017, 18, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, R.; Li, T.; Wang, Y.; Wang, R.; Li, R.; Bianchi, P.; Duplan, H.; Zhang, Y.; Li, H.; Wang, R. The facial microbiome and metabolome across different geographic regions. Microbiol. Spectr. 2024, 12, e0324823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Liu, X.; Jia, Q.; Xu, J.; Shi, J.; Li, X.; Xie, G.; Zhao, X.; He, K. Longitudinal multi-omics analysis uncovers the altered landscape of gut microbiota and plasma metabolome in response to high altitude. Microbiome 2024, 12, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Li, A.; Hoyt, J.R.; Dai, W.; Leng, H.; Li, Y.; Li, W.; Liu, S.; Jin, L.; Sun, K.; et al. Activity of bacteria isolated from bats against Pseudogymnoascus destructans in China. Microb. Biotechnol. 2022, 15, 469–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brucker, R.M.; Harris, R.N.; Schwantes, C.R.; Gallaher, T.N.; Flaherty, D.C.; Lam, B.A.; Minbiole, K.P. Amphibian chemical defense: Antifungal metabolites of the microsymbiont Janthinobacterium lividum on the salamander Plethodon cinereus. J. Chem. Ecol. 2008, 34, 1422–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clements, A.E.; Lee, A.G.; Otoo, B.N.; Regalado, R.R.; Dainko, D.C.; Keller, N.P.; Salazar-Hamm, P.S.; Caesar, L.K. Biochemometric Analysis of Bat Skin Microbiome-Associated Streptomyces buecherae Identifies Polyether Antibiotics Active Against the Bat Pathogen Pseudogymnoascus destructans. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2025, 20, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langwig, K.E.; Frick, W.F.; Reynolds, R.; Parise, K.L.; Drees, K.P.; Hoyt, J.R.; Cheng, T.L.; Kunz, T.H.; Foster, J.T.; Kilpatrick, A.M. Host and pathogen ecology drive the seasonal dynamics of a fungal disease, white-nose syndrome. Proc. Biol. Sci. 2015, 282, 20142335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyt, J.R.; Sun, K.; Parise, K.L.; Lu, G.; Langwig, K.E.; Jiang, T.; Yang, S.; Frick, W.F.; Kilpatrick, A.M.; Foster, J.T.; et al. Widespread Bat White-Nose Syndrome Fungus, Northeastern China. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2016, 22, 140–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keurentjes, A.J.; Jakasa, I.; Kezic, S. Research Techniques Made Simple: Stratum Corneum Tape Stripping. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2021, 141, 1129–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller, L.K.; Lorch, J.M.; Lindner, D.L.; O’Connor, M.; Gargas, A.; Blehert, D.S. Bat white-nose syndrome: A real-time TaqMan polymerase chain reaction test targeting the intergenic spacer region of Geomyces destructans. Mycologia 2013, 105, 253–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eiler, A.; Heinrich, F.; Bertilsson, S. Coherent dynamics and association networks among lake bacterioplankton taxa. ISME J. 2012, 6, 330–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estaki, M.; Jiang, L.; Bokulich, N.A.; McDonald, D.; González, A.; Kosciolek, T.; Martino, C.; Zhu, Q.; Birmingham, A.; Vázquez-Baeza, Y.; et al. QIIME 2 Enables Comprehensive End-to-End Analysis of Diverse Microbiome Data and Comparative Studies with Publicly Available Data. Curr. Protoc. Bioinform. 2020, 70, e100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Callahan, B.J.; McMurdie, P.J.; Rosen, M.J.; Han, A.W.; Johnson, A.J.; Holmes, S.P. DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat. Methods 2016, 13, 581–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bokulich, N.A.; Kaehler, B.D.; Rideout, J.R.; Dillon, M.; Bolyen, E.; Knight, R.; Huttley, G.A.; Gregory Caporaso, J. Optimizing taxonomic classification of marker-gene amplicon sequences with QIIME 2’s q2-feature-classifier plugin. Microbiome 2018, 6, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolyen, E.; Rideout, J.R.; Dillon, M.R.; Bokulich, N.A.; Abnet, C.C.; Al-Ghalith, G.A.; Alexander, H.; Alm, E.J.; Arumugam, M.; Asnicar, F.; et al. Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible microbiome data science using QIIME 2. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 852–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, Y.; Zhang, M.; Liu, Y.; Yang, X.; Wei, F.; Jin, X.; Liu, D.; Guo, Y.; Hu, Y. Quantitative microbiome profiling reveals the developmental trajectory of the chicken gut microbiota and its connection to host metabolism. iMeta 2023, 2, e105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMurdie, P.J.; Holmes, S. phyloseq: An R package for reproducible interactive analysis and graphics of microbiome census data. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e61217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Shen, F.; Yang, Y.; Niu, M.; Chen, D.; Chen, L.; Wang, S.; Zheng, Y.; Sun, Y.; Zhou, F.; et al. Insights into the Profile of the Human Expiratory Microbiota and Its Associations with Indoor Microbiotas. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 6282–6293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouquier, J.; Rideout, J.R.; Bolyen, E.; Chase, J.; Shiffer, A.; McDonald, D.; Knight, R.; Caporaso, J.G.; Kelley, S.T. Ghost-tree: Creating hybrid-gene phylogenetic trees for diversity analyses. Microbiome 2016, 4, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, W.; Fan, T.; Wang, S.; Yu, X.; Lu, A.; Wang, X.; Zhou, W.; Yuan, H.; Zhang, L. Seasonal changes driving shifts in microbial community assembly and species coexistence in an urban river. Sci. Total. Environ. 2023, 905, 167027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langfelder, P.; Horvath, S. WGCNA: An R package for weighted correlation network analysis. BMC Bioinform. 2008, 9, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antonov, M.; Csárdi, G.; Horvát, S.; Müller, K.; Nepusz, T.; Noom, D.; Salmon, M.; Traag, V.; Welles, B.F.; Zanini, F. igraph enables fast and robust network analysis across programming languages. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2311.10260v1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Cáceres, M.; Legendre, P. Associations between species and groups of sites: Indices and statistical inference. Ecology 2009, 90, 3566–3574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemieux-Labonté, V.; Simard, A.; Willis, C.K.R.; Lapointe, F.J. Enrichment of beneficial bacteria in the skin microbiota of bats persisting with white-nose syndrome. Microbiome 2017, 5, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segata, N.; Izard, J.; Waldron, L.; Gevers, D.; Miropolsky, L.; Garrett, W.S.; Huttenhower, C. Metagenomic biomarker discovery and explanation. Genome Biol. 2011, 12, R60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heischmann, S.; Quinn, K.; Cruickshank-Quinn, C.; Liang, L.P.; Reisdorph, R.; Reisdorph, N.; Patel, M. Exploratory Metabolomics Profiling in the Kainic Acid Rat Model Reveals Depletion of 25-Hydroxyvitamin D3 during Epileptogenesis. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 31424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.; Xu, C.; Wang, X.; Ju, F.; Fu, J.; Ni, Y. MetOrigin 2.0: Advancing the discovery of microbial metabolites and their origins. iMeta 2024, 3, e246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaffer, M.; Armstrong, A.J.S.; Phelan, V.V.; Reisdorph, N.; Lozupone, C.A. Microbiome and metabolome data integration provides insight into health and disease. Transl. Res. 2017, 189, 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, S.C.; Alford, R.A.; Garland, S.; Padilla, G.; Thomas, A.D. Screening bacterial metabolites for inhibitory effects against Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis using a spectrophotometric assay. Dis. Aquat. Organ. 2013, 103, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonoyama, K.; Fujiwara, R.; Takemura, N.; Ogasawara, T.; Watanabe, J.; Ito, H.; Morita, T. Response of gut microbiota to fasting and hibernation in Syrian hamsters. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009, 75, 6451–6456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Q.; Hu, Z.F.; Du, X.P.; Bie, J.; Wang, H.B. Effects of Seasonal Hibernation on the Similarities Between the Skin Microbiota and Gut Microbiota of an Amphibian (Rana dybowskii). Microb. Ecol. 2020, 79, 898–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Ning, D. Stochastic Community Assembly: Does It Matter in Microbial Ecology? Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2017, 81, 10–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leng, H.; Li, A.; Li, Z.; Hoyt, J.R.; Dai, W.; Xiao, Y.; Feng, J.; Sun, K. Variation and assembly mechanisms of Rhinolophus ferrumequinum skin and cave environmental fungal communities during hibernation periods. Microbiol. Spectr. 2025, 13, e0223324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemieux-Labonté, V.; Tromas, N.; Shapiro, B.J.; Lapointe, F.J. Environment and host species shape the skin microbiome of captive neotropical bats. PeerJ 2016, 4, e2430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudoir, M.J.; DeAngelis, K.M. A framework for integrating microbial dispersal modes into soil ecosystem ecology. iScience 2022, 25, 103887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, B.; Wang, Y.; Ye, S.; Liu, S.; Stirling, E.; Gilbert, J.A.; Faust, K.; Knight, R.; Jansson, J.K.; Cardona, C.; et al. Earth microbial co-occurrence network reveals interconnection pattern across microbiomes. Microbiome 2020, 8, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coux, C.; Rader, R.; Bartomeus, I.; Tylianakis, J.M. Linking species functional roles to their network roles. Ecol. Lett. 2016, 19, 762–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forsythe, A.; Fontaine, N.; Bissonnette, J.; Hayashi, B.; Insuk, C.; Ghosh, S.; Kam, G.; Wong, A.; Lausen, C.; Xu, J.; et al. Microbial isolates with Anti-Pseudogymnoascus destructans activities from Western Canadian bat wings. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 9895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontaine, C.; Guimarães, P.R., Jr.; Kéfi, S.; Loeuille, N.; Memmott, J.; van der Putten, W.H.; van Veen, F.J.; Thébault, E. The ecological and evolutionary implications of merging different types of networks. Ecol. Lett. 2011, 14, 1170–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, T.; Boutin, S.; Humphries, M.M.; Dantzer, B.; Gorrell, J.C.; Coltman, D.W.; McAdam, A.G.; Wu, M. Seasonal, spatial, and maternal effects on gut microbiome in wild red squirrels. Microbiome 2017, 5, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da, Y.; Liu, M.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, W.; Lu, Y.; Sun, K. Isolation of Antagonistic Bacterial Strains and Their Antimicrobial Volatile Organic Compounds Against Pseudogymnoascus destructans in Rhinolophus ferrumequinum Wing Membranes. Ecol. Evol. 2025, 15, e71628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aguilar, P.; Sommaruga, R. The balance between deterministic and stochastic processes in structuring lake bacterioplankton community over time. Mol. Ecol. 2020, 29, 3117–3130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, C.M.; Hong, T.; van Pijkeren, J.P.; Hemarajata, P.; Trinh, D.V.; Hu, W.; Britton, R.A.; Kalkum, M.; Versalovic, J. Histamine derived from probiotic Lactobacillus reuteri suppresses TNF via modulation of PKA and ERK signaling. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e31951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuhrer, A.; Sprenger, N.; Kurakevich, E.; Borsig, L.; Chassard, C.; Hennet, T. Milk sialyllactose influences colitis in mice through selective intestinal bacterial colonization. J. Exp. Med. 2010, 207, 2843–2854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eisenstein, T.K. The Role of Opioid Receptors in Immune System Function. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 2904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, S.; Bahramnejad, B.; Abdollahzadeh, J.; Bashiri, S.; Vincent, A.T.; Majdi, M.; Soltani, J.; Levesque, R.C. Novel endophytic fungal species Pithoascus kurdistanensis producing morphine compounds. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 22747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, Y.; Xiao, L.; Li, M.; Liu, S.; Wang, Y.; Huang, L.; Liu, S.; Jiang, T.; Zhou, L.; Li, Y. Perillartine protects against metabolic associated fatty liver in high-fat diet-induced obese mice. Food Funct. 2023, 14, 961–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paganelli, A.; Righi, V.; Tarentini, E.; Magnoni, C. Current Knowledge in Skin Metabolomics: Updates from Literature Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 8776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowack, J.; Stawski, C.; Geiser, F. More functions of torpor and their roles in a changing world. J. Comp. Physiol. B 2017, 187, 889–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carey, H.V.; Andrews, M.T.; Martin, S.L. Mammalian hibernation: Cellular and molecular responses to depressed metabolism and low temperature. Physiol. Rev. 2003, 83, 1153–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guimarães, A.; Venâncio, A. The Potential of Fatty Acids and Their Derivatives as Antifungal Agents: A Review. Toxins 2022, 14, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masip, L.; Veeravalli, K.; Georgiou, G. The many faces of glutathione in bacteria. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2006, 8, 753–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, U.N. Arachidonic acid and other unsaturated fatty acids and some of their metabolites function as endogenous antimicrobial molecules: A review. J. Adv. Res. 2018, 11, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, J.L.; Sol Cuenca, M.; Molina-Santiago, C.; Segura, A.; Duque, E.; Gómez-García, M.R.; Udaondo, Z.; Roca, A. Mechanisms of solvent resistance mediated by interplay of cellular factors in Pseudomonas putida. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2015, 39, 555–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshimoto, S.; Hattori, M.; Inoue, S.; Mori, S.; Ohara, Y.; Hori, K. Identification of toluene degradation genes in Acinetobacter sp. Tol 5. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2025, 140, 284–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.L.; Ferrieres, L.; Jass, J.; Hyötyläinen, T. Metabolic Changes in Pseudomonas oleovorans Isolated from Contaminated Construction Material Exposed to Varied Biocide Treatments. Metabolites 2024, 14, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, W.; Wei, X.; Tang, H.; Li, L.; Huang, R. Complete Genome Sequence and Biodegradation Characteristics of Benzoic Acid-Degrading Bacterium Pseudomonas sp. SCB32. BioMed Res. Int. 2020, 2020, 6146104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cassier-Chauvat, C.; Marceau, F.; Farci, S.; Ouchane, S.; Chauvat, F. The Glutathione System: A Journey from Cyanobacteria to Higher Eukaryotes. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beccaccioli, M.; Pucci, N.; Salustri, M.; Scortichini, M.; Zaccaria, M.; Momeni, B.; Loreti, S.; Reverberi, M.; Scala, V. Fungal and bacterial oxylipins are signals for intra- and inter-cellular communication within plant disease. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 823233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indahl, U.G. The O-PLS methodology for orthogonal signal correction-is it correcting or confusing? J. Chemom. 2020, 34, e2884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhao, F.; Xu, C.; Zhang, Q.; Ren, H.; Huang, X.; He, C.; Ma, J.; Wang, Z. Metabolic reprogramming in skin wound healing. Burns. Trauma 2024, 12, tkad047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, R.D.; Hajiarbabi, K.; Den Ng, B.; Sood, A.; Ferreira, R.B.R. Skin-associated commensal microorganisms and their metabolites. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2025, 136, lxaf111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chevrette, M.G.; Carlson, C.M.; Ortega, H.E.; Thomas, C.; Ananiev, G.E.; Barns, K.J.; Book, A.J.; Cagnazzo, J.; Carlos, C.; Flanigan, W.; et al. The antimicrobial potential of Streptomyces from insect microbiomes. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le, V.H.; King, T.; Wuerzberger, B.; Bauer, O.R.; Carver, M.N.; Chan, T.S.; Henson, A.L.; Hubbard, G.K.; Kopadze, T.; Patterson, C.F.; et al. Metabolites derived from bacterial isolates of the human skin microbiome inhibit Staphylococcus aureus biofilm formation. Microbiol. Spectr. 2025, 13, e0130625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, H.K.; Bang, Y.J. Aromatic Amino Acid Metabolites: Molecular Messengers Bridging Immune-Microbiota Communication. Immune Netw. 2025, 25, e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.; Cho, M.; Jung, E.S.; Sim, I.; Woo, Y.R. Investigating Distinct Skin Microbial Communities and Skin Metabolome Profiles in Atopic Dermatitis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 5211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.Y.; Peng, X.X.; Wu, Y.; Peng, M.J.; Liu, T.H.; Tan, Z.J. Intestinal mucosal microbiota mediate amino acid metabolism involved in the gastrointestinal adaptability to cold and humid environmental stress in mice. Microb. Cell Fact. 2024, 23, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siqueira, R.; Hradkova, I.; Leite-Silva, V.R.; Andréo-Filho, N.; Lopes, P.S. Skin Lipids and Their Influence on Skin Microbiome and Skin Care. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 28534–28546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinis, F.I.; Alvarez, S.; Andrews, M.T. Mass spectrometry of the white adipose metabolome in a hibernating mammal reveals seasonal changes in alternate fuels and carnitine derivatives. Front. Physiol. 2023, 14, 1214087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davinelli, S.; Nielsen, M.E.; Scapagnini, G. Astaxanthin in Skin Health, Repair, and Disease: A Comprehensive Review. Nutrients 2018, 10, 522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, R.S.; Moorthy, I.M.; Baskar, R. Modeling and optimization of glutamic acid production using mixed culture of Corynebacterium glutamicum NCIM2168 and Pseudomonas reptilivora NCIM2598. Prep. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2013, 43, 668–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, D.H.; Hekmaty, S.; Seecoomar, G. Homeostasis of glutathione is associated with polyamine-mediated β-lactam susceptibility in Acinetobacter baumannii ATCC 19606. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2013, 57, 5457–5461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carević, T.; Kolarević, S.; Kolarević, M.K.; Nestorović, N.; Novović, K.; Nikolić, B.; Ivanov, M. Citrus flavonoids diosmin, myricetin and neohesperidin as inhibitors of Pseudomonas aeruginosa: Evidence from antibiofilm, gene expression and in vivo analysis. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2024, 181, 117642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, J.; Ma, Y.; Chen, S.; Liu, C.; Song, Y.; Qin, Y.; Yuan, C.; Liu, Y. Melatonin-Producing Endophytic Bacteria from Grapevine Roots Promote the Abiotic Stress-Induced Production of Endogenous Melatonin in Their Hosts. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilinçel, Ö.; Çaliskan, E.; Sahin, I.; Öztürk, C.E.; Kiliç, N.; Öksüz, S. The effect of melatonin on antifungal susceptibility in planktonic and biofilm forms of Candida strains isolated from clinical samples. Med. Mycol. 2019, 57, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Bi, R.; Cai, H.; Zhao, J.; Sun, P.; Xu, W.; Zhou, Y.; Yang, W.; Zheng, L.; Chen, X.L.; et al. Melatonin functions as a broad-spectrum antifungal by targeting a conserved pathogen protein kinase. J. Pineal Res. 2023, 74, e12839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, F.; Song, W.; Wang, D.; Huang, Z.; Shan, M.; Sun, S.; Jin, Z.; Lu, J.; Ji, Y.; Sun, K.; et al. Investigating the Dynamic Variation of Skin Microbiota and Metabolites in Bats During Hibernation. Biology 2025, 14, 1648. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121648

Wang F, Song W, Wang D, Huang Z, Shan M, Sun S, Jin Z, Lu J, Ji Y, Sun K, et al. Investigating the Dynamic Variation of Skin Microbiota and Metabolites in Bats During Hibernation. Biology. 2025; 14(12):1648. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121648

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Fan, Wendi Song, Denghui Wang, Zihao Huang, Mingqi Shan, Shaopeng Sun, Zhouyu Jin, Jiaqi Lu, Yantong Ji, Keping Sun, and et al. 2025. "Investigating the Dynamic Variation of Skin Microbiota and Metabolites in Bats During Hibernation" Biology 14, no. 12: 1648. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121648

APA StyleWang, F., Song, W., Wang, D., Huang, Z., Shan, M., Sun, S., Jin, Z., Lu, J., Ji, Y., Sun, K., & Li, Z. (2025). Investigating the Dynamic Variation of Skin Microbiota and Metabolites in Bats During Hibernation. Biology, 14(12), 1648. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121648