Simple Summary

This review examines the clinical and academic role of quantitative spinal cord imaging in neurodegenerative and acquired spinal cord disorders. Cervical spinal cord atrophy is readily detected in a range of motor neuron disease (MND) phenotypes (ALS, PLS, PMA, SBMA, PPS, and SMA), hereditary ataxias (SCA, FDRA), HSP, and other neurodegenerative disorders. Cord changes may be detected in the pre-symptomatic stages of the disease in association with certain genotypes. Longitudinal studies often capture progressive cord atrophy over time. Diffusion tensor imaging studies have detected cervical spinal cord diffusivity alterations in ALS, PLS, SBMA, FDRA, HSP, ALD, HAM/TSP, following spinal cord infarcts or sensory neuronopathies. The few MRS studies reveal altered metabolite ratios in the cervical cord in ALS and FDRA. These academic observations have important clinical implications, helping to define the potential diagnostic and monitoring role of these metrics and ultimately the development of clinically useful biomarkers for clinical trials, diagnostic applications, and tools to monitor disease progression.

Abstract

Introduction: Quantitative spinal cord imaging has facilitated the objective appraisal of spinal cord pathology in a range of neurological conditions both in the academic and clinical setting. Diverse methodological approaches have been implemented, encompassing a range of morphometric, diffusivity, susceptibility, magnetization transfer, and spectroscopy techniques. Advances have been fueled both by new MRI platforms and acquisition protocols as well as novel analysis pipelines. The quantitative evaluation of specific spinal tracts and grey matter indices has the potential to be used in diagnostic and monitoring applications. The comprehensive characterization of spinal disease burden in pre-symptomatic cohorts, in carriers of specific genetic mutations, and in conditions primarily associated with cerebral disease, has contributed important academic insights. Methods: A narrative review was conducted to examine the clinical and academic role of quantitative spinal cord imaging in a range of neurodegenerative and acquired spinal cord disorders, including hereditary spastic paraparesis, hereditary ataxias, motor neuron diseases, Huntington’s disease, and post-infectious or vascular disorders. Results: The clinical utility of specific methods, sample size considerations, academic role of spinal imaging, key radiological findings, and relevant clinical correlates are presented in each disease group. Conclusions: Quantitative spinal cord imaging studies have demonstrated the feasibility to reliably appraise structural, microstructural, diffusivity, and metabolic spinal cord alterations. Despite the notable academic advances, novel acquisition protocols and analysis pipelines are yet to be implemented in the clinical setting.

1. Introduction

Recent methodological advances in quantitative spinal cord imaging have facilitated the objective appraisal of spinal cord pathology across a spectrum of genetic and acquired neurological conditions. Given the vast array of imaging techniques, for discussion purposes, spinal imaging methods may be categorized into structural, microstructural, or metabolic. Structural imaging methods include spinal cord cross-sectional area (CSA) measurements, which is a surrogate marker for whole spinal cord atrophy. It is estimated over a representative number of T1- (T1w) or T2-weighted (T2w) axial images at specific vertebral levels. Recent spinal cord segmentation methods have permitted selective appraisal of cervical cord grey matter (GM) and white matter (WM). Other T1w- or T2w-derived structural metrics include spinal cord eccentricity measurements. Microstructural imaging methods encompass diffusion tensor imaging (DTI), magnetization transfer (MT), and inhomogeneous magnetization transfer (ihMT) imaging. DTI-derived metrics—fractional anisotropy (FA), radial diffusivity (RD), axial diffusivity (AxD), and mean diffusivity (MD)—have been associated with different aspects of white matter integrity [1,2]. Novel MT and ihMT-derived metrics reflect primarily on myelination. The spinal implementation of novel white matter techniques such as neurite orientation dispersion and density imaging (NODDI), high angular resolution diffusion imaging (HARDI), and q-ball imaging (QBI) is ongoing [3,4,5,6]. Metabolic imaging methods include magnetic resonance spectroscopy, which measures voxel-wise neurometabolite concentrations or their ratios. The most commonly evaluated metabolites include N-acetyl aspartate (NAA) which is regarded as a marker of neuronal integrity; creatine (Cr), a proxy of tissue energy metabolism; choline (Cho), a membrane integrity marker; and myo-inositol (m-Ins), which is primarily associated with glial function. With the exception of special indications, spinal PET is seldom utilized [7], and spinal FDG-PET is typically reserved for distinguishing inflammatory myelopathies from neoplastic myelopathies [8]. Spinal functional MRI (fMRI) is also in its infancy compared to cerebral fMRI, but spinal fMRI has already proven to be a reliable measure of spinal activation in both resting state and task-based protocols [9]. Structural, microstructural, and metabolic spinal imaging methods generate complimentary information that helps to characterize the topography, extent, and nature of spinal cord involvement. While these spinal imaging methods are increasingly used in the academic setting and have enhanced our understanding of neurodegenerative processes in a range of neurological conditions, they are seldom utilized in the clinical setting. Accordingly, the main objective of this paper is to review advances in quantitative spinal imaging, identify barriers to their clinical implementation, and evaluate their potential role in clinical decision making, diagnosis, and monitoring. Additional aims include the discussion of stereotyped study limitations, identification of gaps in the literature, and evaluation of the biomarker potential of specific imaging techniques in clinical and clinical trial settings. As this is a dynamically evolving and ever-changing field of research, new spinal studies are published every day. Ultimately, we wish to raise awareness of emerging methods while candidly discussing their advantages and drawbacks.

2. Methods

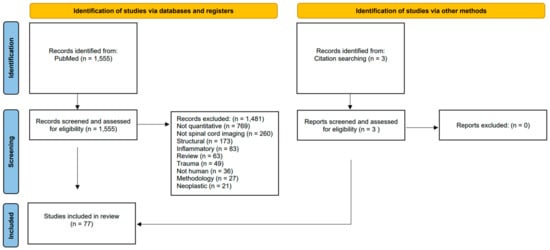

A scoping review was conducted using the PubMed repository (last accessed on 6 April 2023) in accordance with the “preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses” (PRISMA) guidelines (Supplementary File S1 and Figure 1). As this is not a systematic review, the review was not formally registered, and no dedicated protocol was generated. The following search strategy was used: (“Spinal Cord” OR “Cervical Cord”) AND (“Magnetic resonance imaging” OR “MRI” OR “DTI” OR “diffusion tensor imaging” OR “MRS” OR “magnetic resonance spectroscopy”) AND (“Neurodegenerative” OR “Neuromuscular” OR “Motor neuron disease” OR “primary lateral sclerosis” OR “PLS” OR “ALS” OR “amyotrophic lateral sclerosis” OR “MND” OR “SBMA” OR “spinobulbar muscular atrophy” OR “Kennedy’s disease” OR “spinal muscular atrophy” OR “SMA” OR “hereditary spastic paraparesis” OR “hereditary spastic paraplegia” OR “HSP” OR “Parkinson’s disease” OR “Parkinson disease” OR “Huntington’s disease” OR “Huntington disease” OR “Spinocerebellar ataxia” OR “SCA” OR “Friedreich’s Ataxia” OR “Friedreich ataxia” OR “Subacute combined degeneration” OR “Spinal cord ischemia” OR “Spinal cord infarct*” OR “tropical spastic paraparesis” OR “poliomyelitis” OR “HIV myelitis” OR “HIV myelopathy” OR “HIV vacuolar myelopathy” OR “ganglionopathy” OR “sensory neuronopathy”). The database search was limited to studies written in English and only involving human participants. A single reviewer (MCMcK) individually screened the 1555 abstracts for eligibility. All original research articles that investigated quantitative spinal cord imaging in neurodegenerative, neuromuscular, vascular, or infectious disorders were included. Opinion pieces, meta-analyses, and methodology papers were excluded. Previous review papers were also excluded, but the references of review papers of specific neurological conditions were screened for original research papers [10,11]. Structural, inflammatory, neoplastic, and traumatic spinal cord disorders were also excluded. Identified original research articles were systematically reviewed for the primary diagnosis, sample size, availability of genetic information, study design (cross-sectional/longitudinal), imaging methods, and the main quantitative spinal cord imaging results. A total of 77 studies were included (Figure 1). The results of these studies are next discussed stratified by clinical diagnosis.

Figure 1.

A PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses) flowchart outlining the study identification, screening, inclusion, and exclusion review process.

3. Results

3.1. Motor Neuron Disease

3.1.1. Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder primarily associated with motor cortex, brainstem, and anterior horn of the spinal cord degeneration [12,13,14,15,16,17], but frontotemporal, cerebellar, and subcortical involvement is increasingly recognized [18,19,20,21,22]. It is the most common type of motor neuron disease (MND). Clinical phenotypes of ALS can be defined by a multitude of criteria [23,24,25,26,27,28], but typically distinguished either (1) based on disease onset, such as limb onset, bulbar onset, or respiratory onset, (2) based on family history, such as sporadic or familial, (3) based on the degree of comorbid cognitive and behavioral impairment [23,29,30,31], or (4) by the predominance of upper versus lower motor neuron symptoms [32]. Sexual dimorphism in ALS is well recognized based on clinical, genetic, and imaging observations [33,34] and cerebral imaging studies routinely control for sex; the impact of sex on cord metrics is less well established. A multitude of spinal imaging cues have been associated with ALS, such as the “owl’s eyes” (snake eyes) phenomena at the anterior horns or high signal in the lateral columns along the corticospinal tracts, but these qualitative cues are not specific to ALS and may be observed in a range of neurological conditions [35]. The most common quantitative spinal imaging modalities in ALS include cervical cord area or volume estimation (66%; 21/32) [36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56], followed by diffusivity (47%; 15/32) [46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,57,58,59,60,61,62], magnetization transfer ratio (MTR) (19%; 6/32) [48,49,50,51,52,55], T2 hyperintensities (13%; 4/32) [53,54,63,64]; spectroscopy (9%; 3/32) [65,66,67], and a single study used inhomogeneous magnetization transfer ratio (ihMTR) assessments (3%; 1/32) [52]. Several of these studies are multimodal (31%; 10/32) [46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55]. Most studies were performed on three Tesla MRI platforms (75%; 24/32). All studies appraised the cervical spinal cord, and a single study evaluated the entire spinal cord [43]. The mean number of participants was 33 (1–158), and the mean disease duration was 27 (7–77) months. Some studies availed of complementary genetic data (38%; 12/32) that ranged from case-by-case testing to systematically testing all cases for common familial ALS genetic mutations. The majority of spinal studies in ALS are cross-sections, but insightful longitudinal studies have been published (25%; 8/32) [39,40,45,46,47,50,53,56] with a mean follow-up duration of 9 months (3–18). A few particularly elegant pre-symptomatic spinal studies have been published [36,47,66] describing cord involvement before symptom manifestation in certain genotypes. No studies had accompanying post-mortem data to validate and explore the histopathological correlates of their in vivo radiological findings. The characteristics of existing quantitative spinal studies in ALS are summarized in Table 1. The consensus finding of spinal studies in ALS is the presence of progressive [39,40,45,50,53,56] cervical cord atrophy [37,38,39,40,41,43,44,45,46,49,50,51,53,54,56] compared to controls. Cord atrophy is thought to be driven by corticospinal tract (CST) degeneration in the cervical cord [43,44]. This is thought to be supported by an ultra-high-field 7-Tesla MRI study of the cervical cord in ALS [64]. Spinal cord GM and WM segmentation has consistently identified concomitant grey- and white-matter degeneration in the cervical cord [37,38,41,52]. This has recently been facilitated by novel acquisition protocols such as the phase-sensitive inversion recovery (PSIR) MR sequence that minimizes motion sensitivity and susceptibility [37,41]. The clinical correlates of spinal degeneration have been explored by several studies. A cross-sectional study that stratified patients according to King’s staging system reported GM atrophy in King’s stage 1, followed by progressive GM and WM atrophy in all cervical cord segments, increasing in a caudal direction in subsequent King’s stages [41]. This study predicted that the earliest detectable changes occur in the GM at the C3-C4 level and may even be detected several months before symptom onset [41]. A study evaluating the entire spinal cord in ALS identified the most marked radiological changes at C4-C7, and no significant atrophy was detected at thoracolumbar levels, suggesting that future ALS studies should focus on the cervical cord [43]. Longitudinal studies suggest that cervical cord atrophy is progressive in ALS [45], and grey matter volume reductions readily differentiate ALS from controls [38]. Reports on anterior-posterior diameter [63] and mean cross-sectional area (CSA) [42] alterations are less consistent in ALS, probably due to sample size limitations [42] and the low spatial resolution of input imaging data [63]. No significant differences are typically reported between disease-onset phenotypes [41], but a trend for more marked cervical cord involvement was noted in those with upper-limb onset [40,46] or upper-limb involvement [41,43] compared to other phenotypes. Bulbar-onset ALS seemed to be the least affected [37,46]. With regards to ALS genotypes, cervical cord atrophy has been demonstrated in SOD1 [55], VAPB [36], and C9orf72 [39,47] hexanucleotide repeat expansion carriers. Cord changes have been detected in pre-symptomatic mutation carriers long before projected symptom onset [36,47]. Overall cervical cord atrophy was detected in pre-symptomatic VAPB carriers [36], and cervical cord WM was atrophy identified in pre-symptomatic C9orf72 hexanucleotide repeat expansion carriers [47]. The later cohort did not exhibit progressive GM or WM cord changes at 18-month follow-up [47], and similarly, no longitudinal changes were detected in another cohort of C9orf72 carriers at short interval follow-up [39]. Fractional anisotropy reductions are the most common diffusivity finding in cervical cord DTI studies in ALS [46,51,54,58,59,61], often with a caudal predominance [49,59,62]. Central cord [62], anterior [46,58,62], lateral [46,49,52,57,58,60,62] and posterior [46,49,62] column diffusivity changes have been captured. This may be accompanied by increased RD [46,49,59,60], increased MD [46,60], or reduced AD [52] in the lateral CSTs and the posterior columns. However, significant MD [59,61] or AxD [46,59] changes are not always detected. The findings of longitudinal spinal cord DTI studies in ALS differ considerably depending on their follow-up interval: no significant changes are detected at 6 months [46]; a decline in FA at 9 months [53]; increased MD at 9 months [53] and 1 year [46]; and increased RD at 1-year follow-up [46]. With regards to ALS phenotypes, there was a trend to more marked FA reductions in upper-limb onset ALS [46], with bulbar-onset ALS being the least affected [46,61]. Regarding ALS genotypes, reduced FA is captured in pre-symptomatic C9orf72 [47] and symptomatic SOD1 [49] carriers. The pre-symptomatic phase of C9orf72 has considerable clinical relevance [68,69,70] as it may represent an important window for early pharmacological intervention [71,72], and indeed, emerging pre-symptomatic spinal has shown progressive FA decline along the corticospinal tracts (CST) [47]. In a subset of pre-symptomatic C9orf72 mutation carriers aged over 40 with a family history of ALS, reduced FA in the CSTs was also detected at baseline [47], suggesting that CST FA alterations in C9orf72 carriers may help to identify those who are more likely to convert to ALS rather than frontotemporal dementia [47]. Spectroscopically, reduced NAA/Cr [65,66,67], NAA/m-Ins [65,66,67], NAA/Cho [66], and Cho/Cr [67] ratios and increased m-Ins/Cr [65] ratios are typically detected in the cervical cord in ALS. A simplistic but potentially helpful interpretation of MRS findings is that reduced NAA indicates neuronal loss, increased Cho levels suggest inflammation [65], and increased m-Ins represents gliosis [65]. A strikingly similar cervical cord metabolic pattern was also captured in pre-symptomatic SOD1 carriers, i.e., reduced NAA/Cr, NAA/m-Ins, and m-Ins/Cr ratios [66], suggesting that early radiological metabolic changes may precede clinical or neurophysiological changes [66]. Cervical cord MTR is much less frequently evaluated in ALS, but progressively [50] reduced MTR ratios [48,49,50,51,52] are consistently observed, particularly in the lateral corticospinal tracts [49,50,52]. In a study of SOD1 ALS, no significant MTR ratio alterations were detected [55]. A study investigating cervical cord ihMTR in ALS detected significantly reduced ihMTR in the WM, anterior GM, CSTs, and posterior columns [52]. The authors of this study suggested that ihMTR may be more sensitive at detecting microstructural changes than conventional MTR or DTI metrics, but this needs to be validated in multimodal studies [52]. Spinal imaging methods may be combined to differentiate patients with ALS from controls [46,48]. A multi-modal classification model using cervical cord CSA, DTI, and MTR variables accurately differentiated ALS from controls with a sensitivity of 88% and a specificity of 85% (AUC 0.96). The best-performing individual variables were RD, followed by FA, and then CSA at C5 spinal level [48]. Multi-modal cervical cord imaging data may also be used to develop prognostic models [38,51]. The risks of direct clinico-radiological associations are well described [73], but structural cervical cord measures have been correlated to muscle strength [49,50], respiratory function [56], disease duration [41,44,55], and motor disability [38,40,44,45,46,50,52,55]. The decline in motor function is thought to be associated with cervical cord atrophy in sporadic ALS but not in those with C9orf72 [39]. The level of predominant cervical cord atrophy anatomically corresponds with muscle weakness patterns [49]. WM and GM cervical cord measures both correlate independently with disease severity [41,46]. Cord diffusivity metrics in ALS also correlate with motor function [59], muscle strength [52], respiratory involvement [59], disease duration [52], and disease severity [46,49,50,54,59]. FA reductions in particular, either of the entire cervical cord [46,52,54,59] or lateral columns [49,50], correlate with muscle strength [52,59], disease severity [46,49,50,54], and rate of disease progression [61]. Reduced NAA/Cr and NAA/m-Ins ratios evaluated by MRS are associated with respiratory involvement and disease severity [65,67]. MTR and ihMTR metrics also correlate with muscle strength and disease duration [52]. Notwithstanding these associations, structural [36,37,39,53,54], diffusivity [53,57,58,60], or metabolic [66,67] metrics often show no correlations with clinical variables [73]. In summary, the main quantitative spinal cord imaging metrics used in ALS-related studies are cross-sectional area measurements and diffusivity metrics. Alterations in these metrics can be captured in pre-symptomatic mutation carriers and correlate well with clinical measures in the symptomatic phase of the disease. Longitudinal spinal studies in ALS readily capture dynamic pathological changes over time [45,50,56], including progressive MTR, structural, and diffusivity alterations [45,50,53]. While changes in these metrics align with our current understanding of ALS pathophysiology, they are not incorporated as auxiliary outcome measures in current clinical trial designs. The practical limitation of using these metrics in ALS studies lies in the difficulty of acquiring MRI data in patients with respiratory weakness and bulbar symptoms, i.e., scanning patients with ALS is increasingly challenging as the disease progresses.

Table 1.

Quantitative spinal cord imaging studies in MND phenotypes.

3.1.2. Primary Lateral Sclerosis

Primary lateral sclerosis (PLS) is a low-incidence MND subtype characterized by exclusive upper motor neuron degeneration [74,75,76]. It typically presents as a gradual onset of lower limb stiffness and spasticity [75,77]. Imaging studies of PLS typically focus on motor system degeneration [78,79,80,81], but subcortical, cerebellar, and frontotemporal changes have been described more recently [18,82,83,84,85]. Despite the marked lower limb spasticity associated with PLS, spinal cord studies are sparse, and with the exception of a few cross-sectional [86] and longitudinal studies [39,40], not many spinal PLS studies have been published. These studies evaluated spinal cord area [39,40], diffusivity [86], and implemented myelin water imaging (MWI) using gradient and spin echo sequence (GRASE) [86]. Published PLS spinal studies are typically rather small with 2–18 participants, and patients are sometimes merged with larger ALS cohorts [40] (Table 1). In an admixed MND cohort incorporating mostly ALS and a few PLS patients, there was cervical spinal cord atrophy with a trend towards longitudinal progression at 6-months follow-up [40]. The presence of cervical cord atrophy was confirmed in a small cohort of PLS patients, but no longitudinal changes were noted at follow-up 6 months later [39]. A DTI study identified increased RD in the cervical cord GM and FA reductions in the lateral columns [86], and GRASE MWI detected low myelin water fraction in the lateral columns along the CSTs [86]. Baseline cervical cord CSA correlated with disability as measured by ALSFRS-R in a cohort of PLS patients [39] and in a clinically admixed MND group consisting of both of ALS and PLS [40]. Disease progression measured by functional rating scale-score decline also correlates with cervical cord atrophy in PLS [39].

3.1.3. Progressive Muscular Atrophy

Progressive muscular atrophy (PMA) is an MND phenotype characterized by exclusive lower motor neuron degeneration. It presents clinically with progressive muscle wasting and weakness and is associated with a better prognosis than ALS. There are two quantitative spinal cord imaging studies that specifically evaluate this condition (Table 1). One study refers to this cohort as “sporadic adult onset lower MND” [63]. The initial 1.5 T MRI cross-sectional study did not detect any changes in cervical spinal cord morphology or signal alterations in PMA compared with controls [63]. In contrast, a recent 3.0 T MRI longitudinal study detected progressive upper cervical cord atrophy in PMA over a median follow-up of 5.5 (3–59) months [39]. Cervical cord atrophy in PMA correlated with functional decline (change in ALSFRS-R) but not with disease severity (ALSFRS-R score) [39].

3.1.4. Spinal and Bulbar Muscular Atrophy

Spinal and bulbar muscular atrophy (SBMA), also known as Kennedy’s disease, is an X-linked autosomal recessive MND caused by a trinucleotide repeat in the AR gene [87,88,89]. It typically presents with insidious-onset bulbar dysarthria and dysphagia with weakness and wasting of the proximal extremities [87,88]. It is often associated with features of androgen insensitivity, such as gynecomastia and a range of endocrine, metabolic, and cardiac manifestations [87]. The radiological involvement of the spinal cord in SBMA has been explored in two cross-sectional studies that primarily investigated ALS but also included patients with SBMA (Table 1). The mean number of genetically confirmed participants was 12.5 (6–19) with a mean symptom duration of 20.25 (16.5–24) years. In SBMA, there is cervical and thoracic spinal cord atrophy compared to both healthy controls and patients with ALS [63]. This may have been because of statistically longer disease duration in the SBMA cohort when compared to the ALS cohort [63]. Spinal cord atrophy in SBMA is postulated to be driven by marked dorsal column involvement [63]. Interestingly, cervical cord diffusivity metrics do not differ significantly between patients with SBMA and controls [61].

3.1.5. Post-Polio Syndrome

Post-polio syndrome (PPS) is a condition that may develop several decades after the initial polio infection [90,91]. It often presents as generalized fatigue, progressive muscle weakness, and atrophy, yet recent imaging studies captured no evidence of significant cerebral atrophy [92,93,94]. A cross-sectional case-control imaging study investigated spinal cord involvement in PPS [95] (Table 1) and detected reduced cervical and thoracic spinal cord area in PPS compared to controls. Cord atrophy was more marked in those with progressive disease, and cord metrics correlated with muscle strength in the corresponding myotomes. These findings were interpreted by the authors as evidence of a secondary post-infectious secondary neurodegenerative process [95].

3.1.6. Spinal Muscular Atrophy

Spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) is an autosomal recessive neuromuscular disorder that is caused by mutations in the SMN1 gene. It presents with gradually progressive muscle weakness involving the arms, legs, and respiratory muscles. The clinical phenotype is stratified according to disease severity (in decreasing order from type 0-type IV) and age of onset [96,97]. There have been both cross-sectional [96,98,99] and longitudinal [97] imaging studies investigating cervical cord involvement in SMA (Table 1). All of these studies were conducted on 3.0 T MRI scanners and investigated spinal cord cross-sectional area [96,97,98,99]; and two studies also investigated DTI metrics in addition [96,99]. All participants had a genetically confirmed diagnosis, but the majority of studies focus on type III or IV clinical phenotype [96,97,98,99]; only a single participant had the more severe type II clinical phenotype [99]. The mean number of participants in the studies was 17 (10–25) with a mean symptom duration of 28 years. Cervical cord atrophy [96,98] with selective GM degeneration [96] is readily detected in SMA. Atrophy is most prominent in levels that innervate proximal muscles; C3-C6 [98]. The pattern of anterior-predominant cord atrophy is thought to indicate anterior horn cell degeneration [98]. Increased cervical cord GM AxD was noted [99], without other DTI abnormalities [96,99]. The only longitudinal SMA study captured no significant change in cervical cord GM or WM cross-sectional area over 2 years [97]. This may be due to the particularly slow disease process in the later stages of the disease or due to early degenerative changes without subsequent progression [97]. This observation could preclude the use of structural cervical cord as an objective biomarker in SMA clinical trials [97]. Similar to ALS imaging studies [73], clinico-radiological correlations have led to variable results. While one study identified significant associations between cervical cord metrics and deltoid muscle strength [96], others detected no correlations between clinical measures and imaging metrics [98,99].

4. Hereditary Ataxias

4.1. Autosomal Dominant Hereditary Ataxias

Spinocerebellar Ataxia

Spinocerebellar ataxias (SCA) encompass a heterogeneous group of neurodegenerative disorders with cerebellar symptom predominance but may be associated with other clinical features such as parkinsonism, pyramidal signs, peripheral neuropathy, or urinary dysfunction. Spinal cord involvement has been evaluated by both cross-sectional case-control studies and longitudinal studies spanning over 1–5 years [100,101] (Table 2). Existing spinal studies in SCAs exclusively evaluate the cervical cord, focusing primarily on spinal cord cross-sectional area [100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107] and eccentricity [102,103,104,106]. The majority of studies rely on 3.0 T MRI data [100,102,103,104,106], but data acquired on 1.5 T [105] and 0.5T [101] platforms have also been evaluated. The mean number of participants is 42 (7–210) in these studies, most of whom had a genetically confirmed diagnosis. None of these studies had accompanying post-mortem data available. The mean symptom duration in these studies was 9 years, and interestingly, two studies included pre-symptomatic cohorts [103,107]. Cervical cord atrophy and flattening was captured in SCA1 [101,104], SCA3 [101,102,103] and SCA7 [106]. It is hypothesized that this is primarily driven by posterior column [102,103] and spinocerebellar tract [107] degeneration. Cervical cord atrophy may be detected in the pre-symptomatic [103,107], early-symptomatic [105], and symptomatic phases of SCA3 [107]. A cross-sectional study of SCA3 detected a relatively linear progression in cervical cord atrophy in a cohort stratified for symptom duration (<5 years, 5–10 years, 10–15 years, and >15 years) [103]. These findings, however, were not validated by longitudinal studies [100,101]. It is thought that lack of progression over time is due to long-standing disease, and patients have already reached maximal spinal cord atrophy [100]. In SCA6, which is often considered a pure cerebellar degeneration phenotype, no cervical cord atrophy was detected [105]. Nonetheless, mean cervical cord CSA correlated with disease severity [105]. Cord indices in SCAs may [102,104,106] or may not [105] correlate with clinical parameters. The degree of cervical cord atrophy correlates with disability and disease duration in SCA1 [104], SCA3 [102], and SCA7 [106]. In some instances, clinico-radiological associations may outperform other imaging biomarkers—such as cerebellar or brainstem imaging metrics [104].

Table 2.

Quantitative spinal cord imaging studies in hereditary ataxias.

4.2. Autosomal Recessive Hereditary Ataxias

4.2.1. Friedreich’s Ataxia

Friedreich’s ataxia (FDRA) is an autosomal recessive trinucleotide repeat expansion disorder that manifests clinically as progressive dysarthria, limb- and gait-ataxia, and loss of lower limb reflexes. It has extra-neurological manifestations, such as cardiac involvement. Radiologically, cerebral, cerebellar, and cervical cord atrophy are the hallmark findings. Spinal cord involvement in FDRA has been investigated by a number of cross-sectional [108,109,110,111,112] and longitudinal [113] imaging studies. These often primarily focus on cross-sectional area and eccentricity [108,109,110,111,112,113], but DTI studies [110,113] and an MRS study [113] have also been published (Table 2). All of these were conducted using 3.0 T platforms, and all participants had a genetically confirmed diagnosis of FRDA. Similar to spinal studies in other neurodegenerative conditions, no post-mortem data were reported to correlate radiological findings with post-mortem histology. The mean number of participants was 68 (21–256) with a mean disease duration of 12.5 years. Quantitative imaging studies have consistently demonstrated cervical and thoracic spinal cord atrophy and increased eccentricity in FDRA compared to healthy controls [108,109,110,111,112,113]. There is greater atrophy in the cervical cord; and greater anteroposterior flattening in the distal thoracic cord [109]. These findings may be captured in early disease [112]. It is suggested that this pattern indicates preferential degeneration of the dorsal columns, lateral CSTs, and spinocerebellar tracts [108,109,112]. DTI studies have captured FA reductions, increased RD, increased MD, and increased AxD [110,113] in the dorsal columns, fasciculus gracilis, fasciculus cuneatus, and corticospinal tracts [110]. An MRS study detected N-acetyl-aspartate (tNAA) reductions, increased m-Ins, and a decreased ratio tNAA/m-Ins in the cervical cord compared to healthy controls [113]. A longitudinal study demonstrated progressive spinal cord atrophy, tNAA/m-Ins ratio changes, and a decline in FA over time [113]. Longitudinal atrophy was confined to cord WM and not the GM [113]. There are promising initiatives to map these radiological changes systematically in FDRA in a multimodal setting, including spinal morphometric, diffusivity, and spectroscopy metrics [114]. Spinal indices show good correlation with clinical measures [108,109,110,112,113]. The cervical cord CSA correlates with disease duration [109,110] and disease severity as measured by Friedreich’s Ataxia Rating Scales (FARS) [108,110,112,113], Scale for Assessment and Rating of Ataxia (SARA) [109,113], Inventory of Non-Ataxia Signs [109], or Spinocerebellar Ataxia Functional Index (SCAFI) [109]. Tract-wise and total WM DTI [110,113] as well as MRS [113] correlate significantly with disease severity [110,113]. CST DTI metrics show correlations with disease duration [110]. Similar to ALS studies [115,116], the question of whether imaging findings represent developmental or neurodegenerative changes is often raised [108,109]. Recent studies suggest coexisting developmental alterations with active neurodegenerative processes [111,112,113]. Progressive cervical cord atrophy has been observed with stable preserved eccentricity [111,112] and the findings interpreted as degenerative CST and developmental dorsal column abnormalities [112]. A prospective longitudinal study has demonstrated progressive cervical spinal cord structural and metabolic changes [113]. While spinal cord CSA was proposed as a potential imaging biomarker to monitor disease progression, this needs to be confirmed on well-designed longitudinal studies [112].

4.2.2. Autosomal Recessive Cerebellar Ataxia Type 1

Autosomal recessive cerebellar ataxia type 1 (ARCA1) is a progressive cerebellar syndrome caused by a mutation in the SYNE1 gene. It may be associated with some degree of cognitive impairment and pyramidal signs. A cross-sectional case-control study did not detect cervical cord atrophy in a small cohort of ARCA1 compared with controls (Table 2). It was suggested that the presence or absence of cervical cord atrophy may be helpful to differentiate autosomal recessive ataxias, e.g., FDRA, but sample size limitations may preclude conclusive observations in that regard [117].

4.3. Hereditary Spastic Paraparesis

Hereditary spastic paraparesis (HSP) refers to a heterogenous group of neurodegenerative disorders. It may be classified according to the primary phenotype or the underlying genotype. “Pure-HSP” (pHSP) phenotype refers to a clinical presentation limited to progressive lower limb weakness and spasticity, and “complicated-HSP” (cHSP) phenotype involves other systems. There is a wealth of radiological evidence for spinal cord involvement in HSP (Table 3). The mean number of study participants in these studies is 18 (5–40), with a mean disease duration of 18 years. Most participants carried a genetically confirmed diagnosis [118,119,120,121,122,123,124,125,126,127,128]. For the purpose of comparative analyses, participants were either stratified by the clinical phenotype [118,127,129] or their genetic diagnosis [120,121,122,123,124,125,126]. Similar to other spinal studies in neurodegenerative conditions, no supporting post-mortem data are available. The majority of HSP studies evaluate spinal cord area and eccentricity [118,119,120,121,122,124,125,126,127,129], but diffusivity metrics have also been investigated [61,123,124,128]. All studies evaluated the cervical cord, with some also appraising the thoracic cord [119,121,122,123,124,127,129]. Most studies used a 3.0 T MRI scanner [120,121,122,123,125,126,128], some used a 1.5 T platform [118,119,124,127], and one study relied on data from a 1T scanner [129]. Cervical and thoracic cord atrophy is well recognized in both pHSP and cHSP [118,119,127]. In a cohort of pHSP, reduced anteroposterior thoracic cord diameter was noted in comparison to healthy controls [129]. Despite the distinctly different phenotypes, there were no detectable spinal differences between pHSP and cHSP [118,127]. No distinguishing DTI profiles were observed in a clinically heterogenous group of HSP patients as part of an ALS study [61]. In genetically defined cohorts, varying degrees of spinal cord atrophy are described in SPG4 [124,125,126], SPG5 [122,123], SPG6 [119], SPG8 [119], SPG11 [120,126]; sometimes in SPG3A [119,121,126]; but not in SPG7 [126]. Subtle spinal cord atrophy in SPG3A [119] may elude detection [126]. Cord atrophy is not typically associated with cord eccentricity changes [120,125] and is more pronounced in the thoracic cord [119,122]. DTI studies have captured tract-specific degeneration with reduced FA and increased RD in the pyramidal tracts and reduced FA in the dorsal columns in the cervical cord in a genetically heterogenous group of patients with HSP [128]. In SPG4, reduced FA was noted in the dorsal columns, lateral and ventral funiculi, and increased RD at the lower cervical and upper thoracic levels [124]. In SPG5, there was reduced FA, increased RD, and increased MD in the dorsal columns and lateral corticospinal tracts in the cervical and upper thoracic cord [123]. Spinal cord metrics in HSP may [120,124,126,128] or may not [118,119,123,126,127,128] correlate with clinical measures. Symptom duration and disability were linked to reduced cervical cord GM area in SPG4 [126] and reduced cervical cord CSA in SPG11 [120]. Disease severity was associated with FA in the lateral funiculi [124] and dorsal column RD [128] in SPG4. However, spinal cord atrophy does not always correlate with clinical metrics in clinically [118,127] or genetically defined HSP [119,126]. This may be due to the “ceiling effect” whereby participants are captured late in their disease process, with considerable disability and established spinal cord atrophy [118,126].

Table 3.

Quantitative spinal cord imaging studies in HSP.

5. Other Genetic Neurodegenerative Disorders

5.1. Huntington’s Disease

Huntington’s disease (HD) is an autosomal dominant trinucleotide repeat expansion disorder manifesting in motor disability, psychiatric symptoms, and cognitive impairment. Cervical spinal cord involvement in HD has been evaluated by dedicated quantitative imaging studies (Table 4). These studies demonstrate progressive upper cervical cord cross-sectional area reductions in both early [130] and established [131] disease. Cervical cord atrophy may [131] or may not [130] be detected in pre-symptomatic cases. There are inconsistent reports of clinico-radiological associations between cervical cord measures and motor deficits in HD [130,131]. Similar to other neurodegenerative conditions [115,116,132], it is often questioned whether radiological changes represent developmental or degenerative changes. However, the association between progressive cord atrophy and worsening motor deficits would seem to indicate a neurodegenerative rather than developmental process [130,131].

Table 4.

Quantitative spinal cord imaging studies in other genetic neurodegenerative disorders.

5.2. Adrenoleukodystrophy

X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy (ALD) is a rare inborn error of metabolism that is caused by mutations in the ABCD1 gene. It results in defective peroxisomal beta-oxidation, causing very long-chain fatty acid accumulation in plasma and tissues. It is sometimes referred to as “metabolic hereditary spastic paraplegia” or “adrenomyeloneuropathy” because it clinically presents as a spectrum of adult-onset adrenocortical insufficiency, progressive myelopathy, and peripheral neuropathy. Spinal cord imaging studies in ALD appraise both spinal cord area [133,134,135] and diffusivity metrics [133,134] (Table 4). The mean number of participants in these studies is 20 (6–42), with a mean symptom duration of 12.5 years. Longitudinal studies have a mean follow-up interval of 1.5 years [135]. One study also included pre-symptomatic participants [135]. Spinal cord studies in ALD have captured cervical and thoracic cord CSA reductions [133,134,135], which were more marked in the thoracic region [133,134]. Flattening of the cervical cord was interpreted as selective dorsal column degeneration [135]. Longitudinal studies capture a trend of progressive upper cervical [135] and upper thoracic [134] cord atrophy. There was no difference in cervical cord CSA in asymptomatic patients compared to controls [135]. DTI studies capture reduced FA [133,134], reduced AxD [133], and increased RD [133] in the upper cervical cord [133]. There is significantly reduced FA, increased MD, and increased RD in the upper cervical cord WM at 2-year follow-up [134]. Cervical cord atrophy may correlate with disease severity [135]; however, DTI metrics do not show associations with clinical measures [133].

6. Acquired Spinal Cord Disorders

6.1. Sensory Neuronopathy

Sensory neuronopathy is characterized by selective dorsal root ganglia degeneration manifesting in marked ataxia and sensory symptoms. It may be “idiopathic” or secondary to autoimmune, paraneoplastic, infectious, metabolic, toxic, or genetic causes. Standard clinical imaging may reveal non-enhancing T2 hyperintensities along the posterior columns on axial views. Only a few MRI studies have appraised these alterations quantitatively. A cross-sectional study evaluated DTI metrics [136]; and a longitudinal study assessed both cord morphology and signal intensity of the ganglia, posterior columns, and C7 nerve root [137] (Table 5). The mean number of participants was only 18 (9–28) [136,137], with a mean disease duration of 8 (4–11) years, encompassing diverse acquired etiologies. Decreased cross-sectional area and increased dorsal root ganglion and posterior column signal intensity and decreased C7 nerve root size were detected in sensory neuronopathy using multiple-echo data image combination (MEDIC) and coronal turbo inversion recovery magnitude (TIRM) sequences [137]. A single DTI study demonstrated cervical cord FA reductions at C3-C4 that differentiated patients with sensory neuronopathies from disease and healthy controls [136]. Interestingly, both the MEDIC posterior column hyperintensities [137] and reduced cervical cord FA [136] are observed in patients without the characteristic T2-weighted posterior column abnormalities on clinical imaging, even in those with short disease duration <1 year [136]. This demonstrates that novel MRI sequences may be more sensitive at detecting spinal cord involvement in sensory neuronopathy and confirming clinical diagnostic suspicions. Longitudinal observations in a single case suggest that radiological changes may begin in the nerve root and propagate towards the posterior columns [137]. The severity of radiological changes in sensory neuronopathies does not seem to correlate with disability [136,137]. Cervical cord FA reductions, however, correlated with pain scores (Leeds Assessment of Neuropathic Symptoms and Signs), indicating that sensory neuronopathy is indeed associated with neuropathic pain [136].

Table 5.

Quantitative spinal cord imaging studies in acquired spinal cord disorders.

6.2. HTLV-1 Associated Myelopathy and Tropical Spastic Paraparesis

HTLV-1 associated myelopathy/tropical spastic paraparesis (HAM/TSP) is a post-infectious myelopathy that presents as a gradually progressive spastic paraparesis that may be associated with sphincter involvement and sensory disturbance. Typical spinal imaging features include spinal cord atrophy and increased signal in the lateral columns. This has been further evaluated in cross-sectional case-control quantitative imaging studies [138,139,140,141] (Table 5). Most studies used 3.0 T MRI platforms [139,140,141], and only a single study used 1.5 T MRI [138]. Spinal cord area [139,140,141], volumes [138,141], T2 hyperintensities [141], and diffusivity metrics [141] were evaluated in HAM/TSP. Most studies focused on the cervical and thoracic spinal cord [138,139,140,141], and only a single study investigated lumbar cord involvement [139]. One HAM/TSP study also included post-mortem data [140]. The mean number of symptomatic, “definite”, or “possible” HAM/TSP participants was 12.5 (7–18) with a mean symptom duration of 8.75 years, and the mean number of asymptomatic HTLV-1 carriers was 6 (2–11). In “definite” HAM/TSP, cervical [138,139,140,141], thoracic [138,139,140,141], and lumbar [139] spinal cord atrophy was identified compared to controls. This was demonstrated by both cross-sectional cord area [138,139,140,141] and volumetric measures [138,141]. The degree of volume loss was greater in the thoracic cord [138,141]. These observations were more pronounced in those with longer disease duration [141]. Spinal cord atrophy was confirmed pathologically; it was particularly prominent in the lateral columns [140]. In those with “possible” HAM/TSP, reduced thoracic cord volumes were noted very similar to those with “definite” HAM/TSP [138]. In asymptomatic HTLV-1 carriers, the spectrum of spinal cord atrophy ranged from normal [138,139,141] to intermediate between normal and “definite” HAM/TSP [139]. In “definite” HAM/TSP, focal T2 hyperintensities were demonstrated in the bilateral anterolateral and dorsal columns extending over several spinal segments [141]. DTI captured FA reductions in the ventral and dorsal spinal tracts compared to controls. No focal lesions or DTI abnormalities were detected in asymptomatic HTLV-1 carriers [141]. Spinal findings in HAM/TSP show associations with clinical metrics [139,141]; reduced cervical cord area [139,141] and volume [141] correlated with disease duration; reduced cervical and thoracic cord area correlated with the Ambulation Index (an ordinal scale based on the 25-foot timed walk test) [139]; and reduced FA in the dorsal tracts correlated with the American spinal cord injury association (ASIA) score [141]. Conversely, the imaging metrics did not correlate with clinical measures of disease severity in other studies [138,140].

6.3. Vascular Aetiologies

Spinal cord infarction is a relatively rare ischemic insult that may involve the anterior or posterior spinal cord arteries, manifesting in distinct clinical syndromes. Anterior spinal cord infarction presents with acute-onset back pain, bilateral lower limb weakness and numbness, sphincter disturbance, and relative sparing of proprioception and vibration. Posterior spinal cord infarction presents with unilateral sensory loss, including impaired proprioception and vibration. It may be “idiopathic” or secondary to atherosclerosis, trauma, or rare etiologies such as fibrocartilaginous embolism. It is radiologically characterized by abnormal T2 signals in the affected vascular territory, but these are often not detected in the acute setting. A longitudinal case series quantified dynamic FA variations in spinal cord infarction [142] (Table 5), revealing FA reductions in the acute setting [142], followed by decreasing FA in a case with worsening symptoms and increasing FA in a case with improving symptoms [142]. It was hypothesized that the younger age and possibly smaller infarct volume may have accounted for the clinical and radiological improvement in the latter case [142].

7. Discussion

Our review highlights that quantitative spinal cord imaging techniques not only offer important academic insights in a range of neurodegenerative and acquired spinal conditions but may soon be developed into viable biomarker applications with real-life clinical utility. Overall, the available literature suggests satisfactory detection sensitivity of clinically relevant pathology at relevant spinal levels in pathognomonic, disease-associated cord structures. The most striking observation is that there is a considerable gap between academic observations and clinical applications, i.e., the majority of the above quantitative cord imaging techniques are seldom utilized in the clinical setting despite their potential in informing clinical decisions, confirming suspected diagnoses, and monitoring disease progression objectively. We have therefore structured our discussion to review the main achievements of the field of quantitative spinal imaging, identify the shortcomings of recent studies, define the most urgent priorities for future research, and review the main barriers to implementing these techniques in routine clinical practice.

8. Academic Insights

Spinal cord imaging studies have enhanced our understanding of disease pathogenesis and propagation by characterizing anatomical patterns of spinal cord involvement from the pre-symptomatic to the terminal stages of neurodegenerative conditions. In some conditions, there is ongoing debate whether radiological changes represent developmental or neurodegenerative changes, or as argued by some neurodegenerative superimposed on developmental changes in some instances [111,112]. Our review has highlighted that computational spinal cord studies are primarily conducted in conditions like ALS, followed by HSP and then SCA, despite ample evidence of cord involvement in a range of other neurological conditions [35,87,90,143]. Overall, all of the reviewed papers confirm the feasibility of meaningfully assessing and measuring spinal changes in neurodegenerative and acquired spinal cord conditions. The main conceptual and academic achievements of the reviewed studies include the characterization of disease-associated disease burden patterns [46,49,52,57,58,60,62], (2) longitudinal trajectories including anatomical propagation patterns and rate of progression [46,53], (3) genotype-associated spinal signatures, and (4) pathological change in asymptomatic mutation carriers [47,69,70]. Several of the above studies also highlight that neurological conditions primarily associated with cerebral involvement, such as PD and HD, also exhibit detectable spinal cord pathology [130,144,145]. The demonstration of considerable cord changes in asymptomatic mutation carriers with no overt neurological disability [47] suggests a certain resilience to pathological change. The notion of network redundancy to withstand some degree of degenerative change without manifesting in motor symptoms is sometimes referred to as “motor reserve”. Analogous to the concept of “cognitive reserve” [146], the notion of “motor reserve” was initially coined based on cerebral studies and is an emerging field of research across a range of neurodegenerative conditions [147,148,149]. Many of the published academic studies have direct clinical relevance. Spinal FA alterations in pre-symptomatic C9orf72 hexanucleotide repeat expansion carriers may help to predict phenoconversion to ALS rather than frontotemporal dementia [47]. Spinal spectroscopic changes may precede detectable structural alterations [66], highlighting its value as an early surrogate marker of neurodegenerative change. Cord ihMTR has been proposed to be more sensitive in detecting microstructural changes than conventional MTR or DTI metrics [52]. While this needs further validation, it highlights the value of multimodal academic studies where a panel of complementary biophysical metrics is evaluated so that their detection sensitivity and tracking potential of specific markers can be juxtaposed and the most relevant metrics are selected for clinical use.

9. Clinical Applications

Despite the considerable progress in demonstrating the potential of quantitative spinal imaging in neurodegeneration, there remains a considerable gap between academic and clinical imaging, and advances in spinal imaging have not been translated into routine clinical applications. Routine clinical spinal protocols continue to be optimized for quick acquisition times to meet the radiological demands of busy hospitals. Spinal imaging is often first acquired in the sagittal plane, and depending on local protocols, radiographers choose the relevant levels for axial views. While this may be satisfactory in structural etiologies such as disk protrusions or tumors, it is less ideal in neurodegenerative conditions. While the large slice gaps of clinical protocols reduce time of acquisition, important intensity changes or signal abnormalities may be missed. While in the academic setting cardiac and respiratory gating is routinely implemented, this is seldom utilized in standard clinical imaging. Notwithstanding these considerations, quantitative spinal imaging in the clinical setting has a huge potential, including (1) the confirmation of the suspected diagnosis, (2) distinguishing similar phenotypes such as ALS/PLS, (3) tracking accruing pathology over time, (4) assessing response to therapy, (5) serving as putative endpoints in clinical trials, (6) potentially acting as prognostic markers, and (7) conceivably, predicting phenoconversion in asymptomatic mutation carriers. There are promising academic studies heralding “real-life” clinical applications in the near future. The distinct radiological patterns of spinal cord involvement with tract-specific degeneration may be used as an adjunctive diagnostic tool. For example, structural imaging studies revealing spinal cord atrophy with increased eccentricity suggest preferential dorsal column degeneration, as seen in FDRA, SCA, and ALD, whereas spinal cord atrophy without increased eccentricity suggests preferential corticospinal tract degeneration, as seen in ALS and HSP. Cerebral MRI data from single individuals have been successfully interpreted in various classification models across a range of neurodegenerative conditions, including AD, MCI, PD, and ALS [150,151,152,153,154,155,156,157,158,159]. With a few exceptions [48], diagnostic classification models have not been widely used on spinal data sets. The lessons of brain-data-based individual-scan interpretation frameworks, which include various machine-learning (ML) and z-score-based approaches, should be carefully considered and applied to spinal data, or combined brain-spinal protocols should be developed to improve the categorization accuracy of existing models [160,161,162,163,164,165]. One of the key observations from cerebral studies is that high accuracy can be achieved in distinguishing a single disease group from healthy controls, but the distinction of two phenotypes based on MRI data alone is much more challenging. Similar to brain applications [166], quantitative spinal cord imaging data may also be ultimately used as an imaging biomarker in clinical trials. The currently used clinical scales are subject to inter-rater variability and may not capture changes in slowly progressive neurodegenerative disorders, whereas quantitative imaging metrics offer objective data that may precede these clinical changes. Ultimately, quantitative spinal data may be used to measure baseline disease burden, track disease progression, and evaluate response to therapy in clinical trials of disease-modifying therapies. This concept was demonstrated in a preliminary study of SPG5 that identified T9 spinal cord area as a potential clinical trial primary endpoint; however, the proposed study duration of 14 years was too long to be applicable to real-world clinical trials [122]. The follow-up intervals of academic longitudinal imaging studies are often criticized for being too short to capture significant changes; however, short follow-up intervals reflect the real-world designs of clinical trials that seldom go on for several years, especially in rapidly progressive conditions such as ALS. Therefore, radiological markers that sensitively detect subtle change over short follow-up periods are of particular pragmatic utility. Despite the achievements of the above studies, the development of research protocols into viable clinical applications is still awaited.

10. Gaps and Shortcomings

Relatively stereotyped shortcomings can be identified in the current literature of quantitative spinal imaging. Spinal studies often suffer from limited sample sizes, and the small cohorts of imaging studies limit the reliability and generalizability of radiological findings. In addition to the relatively small sample sizes of most published studies, the confounding effects of disease-modifying therapies [97] and disease heterogeneity have to be also considered. It is not uncommon that group heterogeneity is further increased by the inclusion of different disease stages [140], phenotypes, and genotypes in an effort to boost sample sizes. Often only a few parameters are evaluated, such as eccentricity or cross-sectional area only, and some studies only assess structural metrics without evaluating diffusivity indices. The spinal studies that do include diffusion sequences often only evaluate the corticospinal tracts (CST) and posterior columns, while other spinal tracts such as vestibulospinal, spinocerebellar, rubrospinal, reticlospinal, and tectospinal tracts are somewhat overlooked. Spinocerebellar projections in particular are also surprisingly understudied despite their likely involvement in a range of gait disorders. The cerebellum is not only involved in SCAs, FRDA, and other primary ataxia syndromes but also in HSP [167] and ALS [19,168,169]; therefore, spinocerebellar and efferent cerebellar projections should be evaluated in more detail. Similarly, several neurodegenerative disorders are classically conceptualized as “pure” brain disorders, even though spinal cord involvement has been demonstrated in Parkinson’s disease [144,145], multiple systems atrophy [170], Huntington’s disease [130], and Alzheimer’s disease [171,172], and spinal cord pathology in these conditions is likely to contribute to the heterogeneity of clinical presentations.

Extrapyramidal gait impairment is also increasingly recognized in motor neuron diseases [173,174,175,176,177], therefore the assessment of spinal white matter tracts should be extended beyond the corticospinal tracts to evaluate tracts like the rubrospinal or spinocerebellar tracts. From an image quality perspective, there is scope to improve MR imaging acquisition and resolution via higher MRI field strength [64,178,179], cardiac- and respiratory-gating [97], which is not always implemented. Alternative MR approaches such as neurite orientation dispersion and density imaging (NODDI), qMT (quantitative magnetization transfer (qMT), MRS, quantitative susceptibility mapping (QSM), functional MRI (fMRI), high angular resolution diffusion imaging (HARDI), and q-ball imaging (QBI) are seldom utilized despite the feasibility of applying these techniques to the spinal cord [3,4,5,6,9,180,181,182,183,184,185]. Spinal PET is also in its infancy in neurodegenerative conditions despite promising studies [186], method papers [7,187], established physiological patterns [188], and oncological applications [189]. While a high number of excellent spinal and outstanding brain imaging studies have been published in most neurodegenerative conditions, there is a striking paucity of integrative studies evaluating the functional interplay and structural connectivity between the brain and cord in the same study with simultaneous brain and cord acquisition [190,191,192,193]. Despite the feasibility, the decussation of the corticospinal tracts is seldom studied. While cerebral sexual dimorphism has a considerable literature both on healthy [194,195] and disease populations [33,34], there is limited literature on cord sexual dimorphism, despite anecdotal observations of notable sex differences in cord metrics. Unfortunately, the complementary clinical scales used in some of these studies are often suboptimal as they may not be validated for a specific condition and may not be necessarily representative of cord pathology [53,136,137]; for example, ALSFRS-R has a bulbar component and is not validated in MND subtypes PMA and PLS [37]. The acquisition of data from relevant spinal levels is a major issue, as some conditions preferentially involve the cervical or thoracic cord. Additionally, superior spinal segments are sometimes analyzed from brain acquisitions, but spinal data in these studies are typically limited to C1-C4 segments [39,40]. This is not an ideal approach, and clinically relevant segments innervating the upper limbs are left out of the field of view (FoV). Dedicated spinal acquisitions seem indispensable. Finally, there are limitations that are specific to longitudinal studies. There may be a selection bias towards less disabled patients, as patients with more severe disability may not be able to participate in follow-up assessments. Some MRI metrics may exhibit “flooring“ and “ceiling“ effects, i.e., patients with long-standing disease may already have maximal spinal cord atrophy or diffusivity change at initial assessment [100]. Follow-up intervals vary significantly in published studies but are often regarded as too short to capture significant radiological changes in slowly progressive neurodegenerative disorders [97]. Similar to early brain imaging studies, the vast majority of quantitative spinal studies compare a specific disease cohort to healthy controls [113] instead of contrasting that cohort to relevant disease controls or other patient groups. The main problem with this approach is that the specificity of the identified changes to that condition remains unclear. Studies contrasting several syndromes [63] and establishing distinguishing imaging features seem superior in this regard and foretell future clinical applications. For example, both PLS and ALS are associated with considerable spinal cord involvement [77,78,196]; therefore, contrasting them individually to healthy controls is of limited relevance. However, the identification of distinguishing spinal features between the two conditions would be hugely helpful, as the two conditions have very different survival prospects and can sometimes be difficult to distinguish clinically in the early phase of the disease [75,196]. In an ideal study, patients with HSP, SBMA, PLS, ALS, and SCA would undergo spinal imaging with a standardized protocol so that the distinguishing imaging signatures could be ascertained. This would translate into genuine clinical utility for the interpretation of an individual scan. Unlike in brain imaging, the absence of large multi-cohort spinal studies precludes the development and validation of machine-learning protocols. Reminiscent of the early days of quantitative brain imaging, most of the published spinal studies are single-center initiatives contributing to the small sample sizes. The lessons and achievements of brain imaging, such as data sharing, standardized protocols, and disease-specific consortia such as the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI), the Canadian ALS Neuroimaging Consortium (CALSNIC), the Neuroimaging Society in ALS (NisALS), and the Genetic Frontotemporal Initiative (GENFI) [197], should be urgently taken into account to establish spinal data repositories, encourage knowledge and method exchange, and foster cross-site cross-border collaborations. Despite pioneering spinal papers [47,67,96,103,107] and ample examples from brain imaging [70], pre-symptomatic spinal imaging has a strikingly limited literature despite the fact that many motor neuron and neurodegenerative diseases are genetic (HSP, SCA, SOD1-ALS, C9orf72-ALS, etc.) With very few exceptions [140], in the absence of complementary post-mortem data, the histopathological correlates of in vivo spinal signal alterations are not described. This is an important shortcoming, as other than insights from animal studies [1,2], the specific histological correlates of radiological changes are not established. In an ideal study design, the ante-mortem radiological spinal changes should be mapped to post-mortem changes to establish whether a certain radiological WM marker primarily reflects axonal or myelin-related change and also to evaluate the ante-mortem detection sensitivity of specific radiological markers. The candid discussion of stereotyped study limitations may help to improve the design of future spinal studies and enable the development of viable clinical tools.

11. Research Priorities for the Development of Viable Clinical Tools

Descriptive, single-cohort academic studies should be superseded by clinically oriented studies focusing on the development of viable diagnostic, prognostic, and monitoring protocols (Table 6). A key focus of forthcoming spinal studies should be the development of single-subject data interpretation frameworks where the quantitative data from a specific individual could be accurately classified into clinically relevant diagnostic, phenotypic, and prognostic categories. Spinal tracts beyond the descending CST and posterior columns should be evaluated. Olivospinal tracts have been assessed in MSA [170], but vestibulospinal, rubrospinal, reticlospinal, and tectospinal tracts should also be assessed, especially with the advent of novel white matter imaging techniques (HARDI, NODDI, QBI, etc.) and the increasing availability of ultra-high filed strength platforms. In light of pioneering studies [130,144,145,170,171,172], spinal involvement should be comprehensively characterized in neurodegenerative conditions classically considered as “brain diseases” such as PD, MSA, AD, and HD. Where possible, clinical spinal protocols should incorporate 3D sequences without slice gaps to permit post hoc quantitative analyses. In the absence of quantitative analyses, high-quality 3D data, or z-scoring to normative data, the usage of subjective terminology based on visual inspection such as “volume loss”, “thinning”, and “atrophic” should be avoided in standard clinical reporting if possible and quantitative protocols suggested instead. Cardiac and respiratory gating should be routinely considered to correct for physiological noise if relatively longer acquisition times are acceptable. Large openly accessible normative data repositories with corresponding height, age, sex, weight, and occupation data would be of considerable value to interpret single patient data at various centers. The lessons of large disease-specific brain data repositories such as ADNI, GENFI, NiSALS, and Track-HD should be considered for the collection, harmonization, and accessibility of multi-site spinal cord data [198,199,200]. The potential advantages and disadvantages of implementing HARDI, QBI, MRT, fMRI, and PET in cord protocols should be formally assessed to inform the design of future academic studies and establish their potential clinical role beyond their mere feasibility. In light of the success of large pre-symptomatic brain studies in a range of genetic neurodegenerative conditions, more effort should be put into pre-symptomatic spinal imaging to clarify propagation patterns and establish whether some of the detected alterations may indeed be developmental as opposed to neurodegenerative. While the performance of specific imaging modalities has been demonstrated in multiple conditions, real-life clinical translation is awaited. Robust validation frameworks are required for the development of real-world clinical applications. Improved performance of spinal imaging markers may curtail the diagnostic journey of patients with rare neurodegenerative conditions, help to distinguish specific phenotypes within disease continua, and act as objective quantitative monitoring markers in clinical trials, translating into better clinical outcomes. Once new spinal protocols are convincingly validated, utilization can be carried out by either a commercial entity, software, a cloud-based application, or a physician in a hospital.

Table 6.

Research priorities for viable clinical quantitative spinal applications.

12. Conclusions

The reviewed academic studies not only highlight the feasibility of quantitatively interpreting spinal imaging data but also viable clinical applications. While computational spinal imaging seems to lag behind cerebral imaging, there is a range of promising developments that will no doubt expedite the clinical applications of computational spinal imaging. These include the increasing availability of high-field and ultra-high-filed platforms, relentless advances in machine learning, effective multi-site and international collaborations, reducing the price of genetic testing, increasing accessibility of cloud computing, the establishment of the legal framework for patient data protocols, the availability of a multitude of open-source image analysis suites, the increase in disease-specific imaging consortia, and in general, an increasing awareness of the tangible benefits of quantitative imaging instead of visual image interpretation. These factors, coupled with relentless technological advances, routine genetic testing, and an ever-increasing number of clinical trials in neurodegeneration, suggest that quantitative spinal imaging does not only have a potential clinical role but may soon be integrated in clinical decision making.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/biology13110909/s1, Supplementary File S1: PRISMA Checklist.

Author Contributions

The manuscript was drafted by M.C.M., J.K., A.P., A.G.-G., E.L.T. and P.B.; study conceptualization, M.C.M., J.K., A.P., A.G.-G., E.L.T. and P.B.; the manuscript was reviewed for intellectual content by M.C.M., J.K., A.P., A.G.-G., E.L.T. and P.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This report was sponsored by the Health Research Board Ireland (JPND-Cofund-2-2019-1 & HRB EIA-2017-019). Professor Bede and the Computational Neuroimaging Group are also supported by the Spastic Paraplegia Foundation (SPF), the Agence Nationale de la Recherche (ANR) France (2022-CEREBRALS), Irish Institute of Clinical Neuroscience (IICN), the EU Joint Programme–Neurodegenerative Disease Research (JPND), Science Foundation Ireland (SFI SP20/SP/8953), the Andrew Lydon scholarship, the Research Motor Neurone (RMN) foundation, and the Iris O’Brien Foundation.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This is a review paper and no patient data been utilized for the generation of this report. Accordingly, no specific Ethics Approval was sought.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No patient data have been utilized for the drafting of this review paper.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge all of our patients with neurodegenerative and acquired spinal conditions. They inspire us to pursue academic research and remind us of the relevance and urgency of meaningful translational research day after day.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

ABCD1—ATP binding cassette subfamily D member 1; ACRA—autosomal recessive cerebellar ataxia; AD—autosomal dominant; ADNI—Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative; ALD—adrenoleukodystrophy; ALS—amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; ALSFRS—amyotrophic lateral sclerosis functional rating scale; ALSFRS-R—revised amyotrophic lateral sclerosis functional rating scale; ASIA—American Spinal Cord Injury Association; ATXN2—ataxin-2; AUC—area under the receiving operating characteristic curve; AxD—axial diffusivity; C9orf72—chromosome 9 open reading frame 72; CALSNIC—Canadian ALS Neuroimaging Consortium; Cho/Cr—choline to creatine ratio; cHSP—complicated HSP; CSA—cross-sectional area; CST—corticospinal tracts; DRG—dorsal root ganglion; DTI—diffusion tensor imaging; FA—fractional anisotropy; FARS—Friedreich’s ataxia rating scale; FDRA—Friedreich’s ataxia; fMRI—functional MRI (fMRI); FoV—field of view; FTD—frontotemporal dementia; FUS—fused-in sarcoma; FVC—forced vital capacity; GENFI—The Genetic Frontotemporal Initiative; GM—grey matter; GRASE—gradient and spin echo sequence; HARDI—high angular resolution diffusion imaging; HAM/TSP—HTLV1 associated myelitis/tropical spastic paraparesis; HD—Huntington’s disease; HSP—hereditary spastic paraparesis; HTLV1—human T-lymphotropic virus 1; ihMTR—inhomogeneous magnetization transfer ratio; IQR—interquartile range; LMND—lower motor neuron disease; ML—machine learning; MEDIC—multiple echo data image combination; MD—mean diffusivity; MGUS—monoclonal gammopathy of uncertain significance; mIns/Cr—myo-inositol to creatine ratio; MMT—manual muscle test; MRI—magnetic resonance imaging; MND—motor neuron disease; MRS—magnetic resonance spectroscopy; MS—multiple sclerosis; MTR—magnetization transfer ratio; MWI—myelin water imaging; NAA/Cho-N—acetyl aspartate to choline ratio; NAA/Cr-N—acetyl aspartate to creatine ratio; NAA/mIns-N—acetyl aspartate to myo-inositol ratio; NiSALS—Neuroimaging Society in ALS; NMO—neuromyelitis optica; NODDI—neurite orientation dispersion and density imaging; OPTN—optineurin; pHSP—pure HSP; PLS—primary lateral sclerosis; PMA—progressive muscular atrophy; PPMS—primary progressive multiple sclerosis; PPS—post-polio syndrome; PRISMA—preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses; PSIR—phase sensitive inversion recovery; QBI-q—ball imaging; qMT—quantitative magnetization transfer; QSM—quantitative susceptibility mapping; RD–radial diffusivity; ROI–region of interest; RRMS—relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis; SACD—subacute combined degeneration; SARA—scale for the assessment and rating of ataxia; SBMA–spinal bulbar muscular atrophy; SCA—spinocerebellar ataxia; SD—standard deviation; SMA—spinal muscular atrophy; SMN1—survival of motor neuron 1; SOD1–superoxide dismutase type 1; SPG—spastic paraplegia; SPRS—spastic paraplegia rating scale; SYNE1—synaptic nuclear envelope protein 1; T—Tesla; TARDBP—TAR DNA binding protein; TBK1—TANK binding kinase 1; tNAA/m-Ins—total N-acetyl aspartate-to-myo-inositol ratio; TRIM—turbo inversion recovery magnitude; VAPB—vesicle-associated membrane protein-associated protein B/C; VB12—vitamin B12; WM—white matter.

References

- Sun, S.W.; Liang, H.F.; Trinkaus, K.; Cross, A.H.; Armstrong, R.C.; Song, S.K. Noninvasive detection of cuprizone induced axonal damage and demyelination in the mouse corpus callosum. Magn. Reson. Med. Off. J. Soc. Magn. Reson. Med./Soc. Magn. Reson. Med. 2006, 55, 302–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, S.K.; Sun, S.W.; Ramsbottom, M.J.; Chang, C.; Russell, J.; Cross, A.H. Dysmyelination revealed through MRI as increased radial (but unchanged axial) diffusion of water. NeuroImage 2002, 17, 1429–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- By, S.; Xu, J.; Box, B.A.; Bagnato, F.R.; Smith, S.A. Application and evaluation of NODDI in the cervical spinal cord of multiple sclerosis patients. NeuroImage Clin. 2017, 15, 333–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grussu, F.; Schneider, T.; Zhang, H.; Alexander, D.C.; Wheeler-Kingshott, C.A. Neurite orientation dispersion and density imaging of the healthy cervical spinal cord in vivo. NeuroImage 2015, 111, 590–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen-Adad, J.; Descoteaux, M.; Rossignol, S.; Hoge, R.D.; Deriche, R.; Benali, H. Detection of multiple pathways in the spinal cord using q-ball imaging. NeuroImage 2008, 42, 739–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labounek, R.; Valošek, J.; Horák, T.; Svátková, A.; Bednařík, P.; Vojtíšek, L.; Horáková, M.; Nestrašil, I.; Lenglet, C.; Cohen-Adad, J.; et al. HARDI-ZOOMit protocol improves specificity to microstructural changes in presymptomatic myelopathy. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 17529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, V. Positron emission tomography in spinal cord disease. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2013, 88, 1188–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flanagan, E.P.; Hunt, C.H.; Lowe, V.; Mandrekar, J.; Pittock, S.J.; O’Neill, B.P.; Keegan, B.M. [18F]-fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography in patients with active myelopathy. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2013, 88, 1204–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powers, J.M.; Ioachim, G.; Stroman, P.W. Ten Key Insights into the Use of Spinal Cord fMRI. Brain Sci. 2018, 8, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bede, P.; Bokde, A.L.; Byrne, S.; Elamin, M.; Fagan, A.J.; Hardiman, O. Spinal cord markers in ALS: Diagnostic and biomarker considerations. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. Off. Publ. World Fed. Neurol. Res. Group Mot. Neuron Dis. 2012, 13, 407–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Mendili, M.M.; Querin, G.; Bede, P.; Pradat, P.F. Spinal Cord Imaging in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: Historical Concepts-Novel Techniques. Front. Neurol. 2019, 10, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tahedl, M.; Tan, E.L.; Chipika, R.H.; Hengeveld, J.C.; Vajda, A.; Doherty, M.A.; McLaughlin, R.L.; Siah, W.F.; Hardiman, O.; Bede, P. Brainstem-cortex disconnection in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: Bulbar impairment, genotype associations, asymptomatic changes and biomarker opportunities. J. Neurol. 2023, 270, 3511–3526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bede, P.; Chipika, R.H.; Finegan, E.; Li Hi Shing, S.; Chang, K.M.; Doherty, M.A.; Hengeveld, J.C.; Vajda, A.; Hutchinson, S.; Donaghy, C.; et al. Progressive brainstem pathology in motor neuron diseases: Imaging data from amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and primary lateral sclerosis. Data Brief 2020, 29, 105229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brettschneider, J.; Del Tredici, K.; Toledo, J.B.; Robinson, J.L.; Irwin, D.J.; Grossman, M.; Suh, E.; Van Deerlin, V.M.; Wood, E.M.; Baek, Y.; et al. Stages of pTDP-43 pathology in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Ann. Neurol. 2013, 74, 20–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, J.M.; van der Burgh, H.K.; Nitert, A.D.; Bede, P.; de Lange, S.C.; Hardiman, O.; van den Berg, L.H.; van den Heuvel, M.P. Connectome-Based Propagation Model in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Ann. Neurol. 2020, 87, 725–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agosta, F.; Chio, A.; Cosottini, M.; De Stefano, N.; Falini, A.; Mascalchi, M.; Rocca, M.A.; Silani, V.; Tedeschi, G.; Filippi, M. The present and the future of neuroimaging in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2010, 31, 1769–1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agosta, F.; Valsasina, P.; Riva, N.; Copetti, M.; Messina, M.J.; Prelle, A.; Comi, G.; Filippi, M. The cortical signature of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e42816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chipika, R.H.; Finegan, E.; Li Hi Shing, S.; McKenna, M.C.; Christidi, F.; Chang, K.M.; Doherty, M.A.; Hengeveld, J.C.; Vajda, A.; Pender, N.; et al. “Switchboard” malfunction in motor neuron diseases: Selective pathology of thalamic nuclei in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and primary lateral sclerosis. NeuroImage Clin. 2020, 27, 102300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]