Simple Summary

Police health and physical fitness are essential for improving quality of life and police skills. This review aims to identify and analyze international and Portuguese studies that have investigated the relationships between various aspects of physical fitness as specified by job descriptions and to understand the health-related requirements of police officers. This will help to select the most used fitness measures and health-related parameters for police officers and improve training curricula for these occupational groups.

Abstract

This review aims (i) to identify and analyze the most used physical fitness tests for police officers (from international and Portuguese studies) and (ii) to understand the health-related physical fitness requirements according to the job descriptions of police officers. A total of 29 studies were included. Eighteen were from around the world and eleven were related to Portuguese police officers. All studies showed acceptable methodological quality in the assessment of physical fitness, and the most used fitness components were muscular strength, endurance, power, aerobic and anaerobic capacity, flexibility, and agility. For the analysis of health parameters, they are insufficient at the international level, while at the Portuguese level we have an acceptable sample. We try to analyze the relationship between physical fitness and health, but the studies conducted so far are insufficient. This review provides summary information (i) to help select the most used fitness measures and health-related parameters for police officers, and (ii) that will serve as a starting point for evaluating the relationship between the health and physical fitness of police officers.

1. Introduction

Law enforcement can be a physically demanding, dangerous, and stressful profession that has health implications. The health and physical fitness of police officers is essential to their performing their duties well [1,2].

Police officers must undergo various physical tasks that include carrying external loads, such as running, restraining offenders, self-defense, and manual handling tasks [3]. They also have social and psychological obligations (e.g., the daily pace of work, job responsibilities, and stress/risk situations). It appears that the physically demanding jobs require high levels of cardiovascular fitness as well as muscular strength and endurance [3,4,5].

The field of public safety has high physical fitness and health requirements for entry into police academies. While recruits learn the physical challenges of the profession while being taught the necessary procedures, skills, and the values and behaviors expected of a police officer, these health-related attributes are only assessed for entry and rarely thereafter [6].

According to the literature, a police officer’s physical fitness tends to decline over time. Previous studies suggest that improving traditional health-related components of physical fitness (i.e., body composition, cardiorespiratory fitness, muscular strength, endurance, and flexibility) is essential for improving quality of life and policing skills [7,8]. However, the risk of developing health problems increases with overall decline in physical activity and associated decline in physical fitness. In fact, low levels of muscle fitness and physical endurance as well as overweight and obesity have been shown to be risk factors for police officer health and to lead to lower productivity levels and sick leave [9], resulting in additional costs to the employer. A high prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors has been found among police officers, including metabolic syndrome, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, smoking, and physical inactivity [2].

Studies on the physical activity, physical fitness, and health of Portuguese police officers are scarce. Therefore, this review aims (i) to identify and analyze the most used physical fitness tests for police officers (from international and Portuguese studies) and (ii) to understand the health-related physical fitness requirements according to the job descriptions of police officers.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Approach to the Problem

A systematic review was conducted to identify the physical fitness tests used on police officers and to describe the fitness levels of this population. This systematic review followed the guidelines of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) model [10]. This study is exempt from ethical approval because the authors collected and synthesized data from previous studies in which informed consent had already been obtained by the study investigators. Therefore, this study was not approved by an institutional review board.

2.2. Procedures

2.2.1. Search Strategy

To identify and obtain relevant original research for the literature review, key literature databases were systematically searched using specific keywords relevant to the topic. The databases searched included PubMed (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/?term=police+officer+AND+Physical+Fitness+AND+Health&sort=date, accessed on 28 September 2021), ScienceDirect (https://www.sciencedirect.com/search?qs=Police%20AND%20Fitness%20test%20AND%20health, accessed on 28 September 2021), and ISCPSI (Higher Institute of Police Sciences and Internal Security) common repositories (https://comum.rcaap.pt/handle/10400.26/6300, accessed on 28 September 2021). These databases were selected because they contain a large number of high-quality, peer-reviewed articles and represent journals relevant to the topic of the study. The final search terms and applied filters for the databases searched are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Databases and relevant search terms.

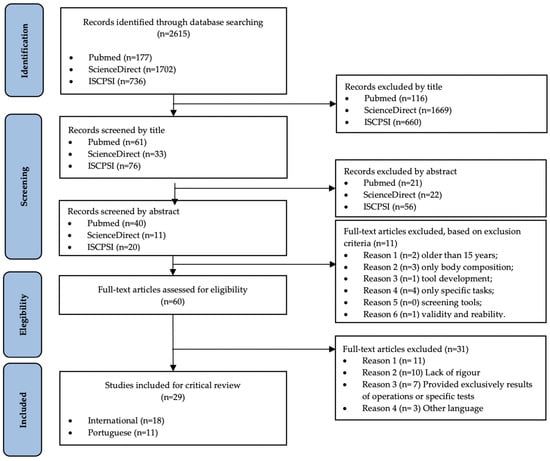

To improve the relevance of search results, filters that reflected study eligibility criteria were applied in each database when available. In the ISCPSI database, where these filters were not available or were only partially available, eligibility criteria for studies were applied manually by screening study titles and abstracts. The eligibility criteria were then applied to the full text of identified articles that were not excluded during the screening of titles and abstracts to make a final selection of eligible articles for this review. The results of the search, screening, and selection processes were documented in a PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1) [10]. The inclusion criteria were defined to include individuals from law enforcement, to measure physical fitness, and to measure health. The exclusion criteria were: studies older than 15 years, studies examining only body composition, studies addressing instrument development, studies addressing only weight bearing, studies addressing only screening instruments, validity studies, and reliability studies. Duplicates were removed after all studies were collected.

Figure 1.

PRISMA diagram detailing the search process.

2.2.2. Critical Appraisal

To assess the methodological quality of the study, the CASP consists of a checklist of ten questions. Each question can be answered “yes,” “can not say,” or “no.” Questions six and seven are short answers that we left blank due to their subjectivity (Critical Appraisal Skills & Programmes, 2018). Methodological quality was also assessed individually by two authors to avoid bias.

2.2.3. Data Extraction

After critically analyzing all articles, we extracted the following information: authors and year of publication; study population; measures (physical fitness tests); measures (health parameters or questionnaires); main results; general conclusions. All of the information is presented in Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4 [2,7,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37].

Table 2.

Data extraction table, including fitness and health measures, with key findings-International Research.

Table 3.

Data extraction table, including fitness and health measures, with key findings-Portuguese Research.

Table 4.

Data extraction table, including fitness and health measures, with key findings-Portuguese Research (Master’s Thesis).

3. Results

3.1. Search Results

A total of 2615 studies were found during the initial search of the three databases. After removing duplicates and screening by title and abstract, the full-text versions of 60 studies were compiled for review. These studies were then assessed against the inclusion and exclusion criteria, leaving 29 studies for critical review (Table 2 and Table 3). A summary of the screening and selection process, as well as the results of the literature search, can be found in the PRISMA flow diagram [10] (Figure 1). The studies reviewed were related to police candidates, recruits/cadets, or officers. Of the 29 studies, eleven referred to Portuguese police officers [11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21] and the other eighteen referred to police officers from around the world (Brazil, USA, Germany, Canada, Korea, Serbia, and Ireland) [2,7,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37]. Eighteen studies examined both male and female participants [7,11,13,15,16,19,21,23,25,26,27,28,30,31,33,34,35,37], while eight studies included only male participants [2,17,18,20,22,24,29,32]. Three studies did not report the gender of the participants [12,14,36].

3.2. Fitness Measures

The most commonly used fitness components were muscle strength, endurance and power, aerobic and anaerobic capacity, and some tests of agility and flexibility.

Muscular strength was assessed in nine international articles [7,22,23,24,26,28,29,33,35] and seven Portuguese studies [12,13,15,18,19,20,21], muscular endurance was measured in 16 international articles [7,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37] and seven Portuguese studies [11,12,15,17,19,20,21], and muscular power was measured in 12 international articles [7,22,23,24,26,28,30,31,32,34,35,37] and five Portuguese studies [12,13,19,20,21].

Other measurements of fitness included aerobic capacity, which was assessed in 16 international articles [2,7,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,34,35,36,37] and seven Portuguese studies [11,12,13,17,19,20,21], and anaerobic capacity was assessed in two international articles [23,33] and two Portuguese studies [19,21]. The least commonly reported fitness measures were agility, which was assessed in three international articles [22,23,32] and two Portuguese studies [20,21], and flexibility was assessed in six international articles [22,23,25,27,28,30] with only one test, and four Portuguese studies [12,15,20,21] with two tests.

Maximal muscular strength was measured in all studies in different forms, including one repetition maximum (1RM) bench press [12,19,22,23,24,28] and leg press [22], handgrip strength [7,12,13,15,18,19,20,21,22,23,26,33,35], back-leg–chest strength [21,26], finger-grip strength [18], and elbow flexion [29]. Muscular endurance was most commonly measured by push-ups [11,12,17,19,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,30,31,33,34,35,36,37], sit-ups [11,15,17,19,20,21,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,33,34,35,37], pull-ups [7,11,12,17,20,21,32,34,36], curl-ups [22], plank time [7], and flexed arm hang [26,29]. Muscular power was measured by vertical jump [7,12,13,19,20,22,23,24,26,28,30,31,32], standing long jump [19,20,21,32,35], medicine ball throw [12,20], and mountain climbers [34].

A wide range of aerobic capacity measures was performed, including treadmill-based aerobic testing [2,13,19,22] or estimated VO2max (201 m run [34], 300 m run [24,28], 1.5-mile run [24,28,31,34], 2.4 km run [27,30,37], 20 m shuttle run [20,21,25,26,29,31,36], 12 min Cooper [35,36], and arm ergometer assessment [23,37]). Anaerobic capacity was measured using either the Wingate anaerobic test [23], or sprint tests [19,21,23,33,37].

Agility was tested by a change of direction test [20,21,22,23,32], and flexibility was measured by the sit-and-reach test [12,15,20,21,22,23,25,27,29,30] and shoulder flexibility [20].

3.3. Health Parameters

Few studies included health parameter assessments or questionnaires in their study design. Anthropometric measurements (classical anthropometry) were the most common, used in 17 international studies [2,7,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,37] and in 9 Portuguese studies [11,12,13,14,16,18,19,20,21]. The second most commonly used assessment was the international physical activity questionnaire (IPAQ) [13,14,16,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30], i.e., the short form, which was assessed in one international [29] and five Portuguese [14,16,18,19,20] studies. Other assessments used in a few studies were the Framingham risk score [2,13], used in two studies; the Jackson’s questionnaire [15,18,19], used in three studies; and the physical activity readiness questionnaire [19,20], used in two studies. Blood pressure [2,13,25], heart rate [7,19,20,25], blood serum [2,13] and lactate [19,20], injuries [7], fatigue [19], stress [14], quality of life [13], or other factors [2,14,15,16,35] were measured as health parameters in some studies.

The results of this study have important implications for the selection of the most commonly used fitness measures for police officers and for the improvement of training plans for police officers, which we have summarized in a synoptic table (Table 5).

Table 5.

Synoptic table.

4. Discussion

All studies showed acceptable methodological quality in the assessment of physical fitness. The analysis of health parameters is insufficient at the international level, while at the Portuguese level we have an acceptable sample for police health. However, if we try to analyze the relationship between physical fitness and health, the studies conducted so far are insufficient, though we will return to this point later.

Differences in fitness tests and test selection procedures have been noted, highlighting the need for standardization of fitness test procedures to ensure consistency and precision when comparing results [31]. Internationally, the most applied assessments were: (i) push-ups [7,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,30,31,33,34,35,36,37], sit-ups [23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,33,34,35,37], vertical jump [7,22,23,24,26,28,30,31,32], and handgrip test [7,22,23,26,33,35] for muscle strength; (ii) 12 min Cooper [35,36], 1.5-mile run [24,28,31,34], 2.4-mile run [27,30,37], and 20 m shuttle run [25,26,29,31,36] for aerobic capacity; and (iii) sit-and-reach [22,23,25,27,29,30] for flexibility. In Portugal, the most commonly applied assessments were: (i) push-ups [11,12,17,19,20,21] and sit-ups [11,15,17,19,20,21] for muscle strength; (ii) standing long jump [19,20,21], vertical jump [12,13,19,20], and medicine ball throw [12,20] for muscle power; (iii) 12 min Cooper [11,12,17,21] for aerobic capacity; and (iv) sit-and-reach for flexibility [12,15,20,21]. Portuguese police officers showed higher levels of physical activity than the general population [12,14], and, in comparing their data with those of international police officers, they showed intermediate levels [15]. Male police officers performed significantly better than female officers on all measures [20,25,26,30,35].

We believe it is important to standardize the scores for the different physical abilities, using our synoptic table to achieve consistency in the assessment parameters for police function.

Regarding health status in terms of physical fitness, a general decline in certain physical attributes between genders has been observed with age [26]. Aerobic capacity emphasizes the need for physical training in order not to compromise performance and to mitigate the effects of increasing age [17,22]. Several studies have shown that the increase in body fat percentage is associated with a decrease in performance and physical fitness [24,27,28]. An increase in lean body mass and a decrease in body fat percentage can positively affect vertical jump performance [24]. Higher body fat percentage resulted in lower cardiorespiratory capacity, lower dynamic strength, and lower flexibility [27]. Moreover, it was proved that improving metabolic fitness and muscular endurance should be the goal of conditioning to improve sit-up performance and running times [23,24]. Agility, aerobic capacity, push-ups, and sit-ups were significantly correlated with police officer tasks [22].

The development of health-related fitness standards and associated health and fitness strategies will help improve officer health and fitness. A strong correlation was found between the morphological, cardiorespiratory, and neuromuscular components of health-related physical fitness [29]. Physical fitness (including anthropometric measures) and health measures should be used together to guide conditioning interventions to improve police performance [12,13,19,22,24,35].

Analysis of these studies with police officers confirms that physical fitness is extremely important for the performance of operational tasks and has a direct influence on health status. Body composition showed a direct influence on physical fitness and cardiovascular risk. In addition, decreased cardiorespiratory fitness was associated with an increase in age-related cardiovascular and metabolic risk [13,14,15,21,22,28,30,34,37]. However, there is a need to implement health-promotion interventions to address cardiovascular and metabolic risk factors [37]. Several studies have found a significant association between age and decline in physical fitness [12,13,15,16,17,21,22,26]. It is critical that police officers maintain appropriate levels of physical fitness as they age [22,26].

However, a limitation of this review was that it was not possible to screen studies that reported on physical fitness and its relationship with health parameters. Few clinical parameters were evaluated to critically analyze this risk relationship. Furthermore, the great variety of physical fitness assessments studied can also be considered a limitation, as the diversity of tests makes it difficult to standardize the protocol for fitness assessment. Another limitation was the inclusion of studies with cadets/recruits and cadets who are not yet police officers.

5. Conclusions

The police profession involves special challenges to the health, physical, and psychological statuses of police officers. The risks of performing police work have numerous, complex, and long-lasting consequences that affect not only the quality of everyday life of police officers, but also the efficiency of the measures and activities undertaken. Therefore, it is necessary to maintain physical condition at an optimal level over a long period of time, monitor changes in the health status of police officers, and point out in a timely manner the positive and negative implications of irresponsible attitudes towards these issues by police officers and police management.

In fact, our research shows that a variety of physical fitness tests exist to assess and predict police officer performance. More and more tests are being used to assess various physical abilities, such as muscular strength and aerobic capacity, but agility and flexibility are still poorly assessed. However, health-related tests are rarely used as a complementary method to diagnose physical and health conditions, even though it is known that there is a direct relationship between the two.

For such a research endeavor, the existing work is a good starting point; the literature referred to also indicates possible directions for research engagement (e.g., researching correlations between regular physical activity, efficiency of police work, and monitoring changes in police health status), and the contextual framework provides an opportunity to identify and use key determinants that shape the health quality of police officers. Accordingly, efforts should be made to evaluate the same protocol of physical fitness tests and include health parameters and to use the results obtained to improve training plans for this occupational group.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and resources, L.M.M. (PI); methodology, formal analysis, investigation, and writing (original draft preparation), L.M.M. and V.S.; writing (review and editing), L.M.M., V.S. and L.F.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Portuguese National Funding Agency for Science, Research and Technology—FCT, grant number UIDP/04915/2020 and UIDB/04915/2020 (ICPOL Research Center —Higher Institute of Police Sciences and Internal Security (ISCPSI)—R&D Unit).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Lockie, R.G.; Moreno, M.R.; Rodas, K.A.; Dulla, J.M.; Orr, R.M.; Dawes, J.J. With great power comes great ability: Extending research on fitness characteristics that influence work sample test battery performance in law enforcement recruits. Work 2021, 68, 1069–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strauss, M.; Foshag, P.; Jehn, U.; Vollenberg, R.; Brzęk, A.; Leischik, R. Exercise capacity, cardiovascular and metabolic risk of the sample of German police officers in a descriptive international comparison. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2021, 18, 2767–2775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomes, C.; Orr, R.M.; Pope, R. The impact of body armor on physical performance of law enforcement personnel: A systematic review. Ann. Occup. Environ. Med. 2017, 29, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orr, R.; Sakurai, T.; Scott, J.; Movshovich, J.; Dawes, J.; Lockie, R.; Schram, B. The Use of Fitness Testing to Predict Occupational Performance in Tactical Personnel: A Critical Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, D.; Pope, R.; Orr, R. Differences in physical characteristics and performance measures of part-time and full-time tactical personnel: A critical narrative review. J. Mil. Veteran’s Health 2016, 23, 24–25. [Google Scholar]

- Blumberg, D.M.; Schlosser, M.D.; Papazoglou, K.; Creighton, S.; Kaye, C.C. New Directions in Police Academy Training: A Call to Action. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lentz, L.; Randall, J.R.; Guptill, C.A.; Gross, D.P.; Senthilselvan, A.; Voaklander, D. The Association Between Fitness Test Scores and Musculoskeletal Injury in Police Officers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marins, E.F.; David, G.B.; Del Vecchio, F.B. Characterization of the Physical Fitness of Police Officers: A Systematic Review. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2019, 33, 2860–2874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyröläinen, H.; Häkkinen, K.; Kautiainen, H.; Santtila, M.; Pihlainen, K.; Häkkinen, A. Physical fitness, BMI and sickness absence in male military personnel. Occup. Med. 2008, 58, 251–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sá, M.; Santos, T.; Afonso, J.; Gouveia, R.; Marques, A. Physical fitness and anthropometrical profile for the recruits of the elite close protection unit of the Portuguese public security police. Police Pract. Res. 2021, 23, 308–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araujo, A.O.; Cancela, J.M.; Bezerra, P.; Chaves, C.; Rodrigues, L.P. Age-related influences on somatic and physical fitness of elite police agents. Retos 2021, 40, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pina, J. Impact of Physical Activity on Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Diseases in Police Officers. Master’s Dissertation, Higher Institute of Police Sciences and Internal Security, Lisbon, Portugal, 2012; p. 167. [Google Scholar]

- Batista, C. Physical Activity, Stress and Lifestyle in Public Safety Police. Master’s Dissertation, Higher Institute of Police Sciences and Internal Security, Lisbon, Portugal, 2014; p. 137. [Google Scholar]

- Prisciliano, J. Physical Fitness and Work Capacity Indices in the Public Security Police. Master’s Dissertation, Higher Institute of Police Sciences and Internal Security, Lisbon, Portugal, 2014; p. 115. [Google Scholar]

- Paulo, S. The Impact of Physical Activity and Food on the Sleep Quality of the Agents Who Perform. Master’s Dissertation, Higher Institute of Police Sciences and Internal Security, Lisbon, Portugal, 2015; p. 125. [Google Scholar]

- Belchior, F. Impact of Physical Fitness on Professional Fitness in an Elite Police Operational Group. Master’s Dissertation, Higher Institute of Police Sciences and Internal Security, Lisbon, Portugal, 2015; p. 117. [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho, C. The Impact of Age, Physical Activity and Fitness on Shooting Performance. Master’s Dissertation, Higher Institute of Police Sciences and Internal Security, Lisbon, Portugal, 2016; p. 102. [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira, J. Physical Fitness for Police Role: Validation of a Police Fitness Circuit. Master’s Dissertation, Higher Institute of Police Sciences and Internal Security, Lisbon, Portugal, 2017; p. 113. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, P. Physical Fitness in Police Role: The Acute Metabolic Impact of Wearing Uniforms and Personal Protective Equipment in Police Science. Master’s Dissertation, Higher Institute of Police Sciences and Internal Security, Lisbon, Portugal, 2021; p. 89. [Google Scholar]

- Coutinho, G. Effect of CFOP and Age on Cadets’ Physical Condition. Master’s Dissertation, Higher Institute of Police Sciences and Internal Security, Lisbon, Portugal, 2021; p. 83. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, A.Q.; Clasey, J.L.; Yates, J.W.; Koebke, N.C.; Palmer, T.G.; Abel, M.G. Relationship of Physical Fitness Measures vs. Occupational Physical Ability in Campus Law Enforcement Officers. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2015, 29, 2340–2350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawley, A.A.; Sherman, R.A.; Crawley, W.R.; Cosio-Lima, L.M. Physical Fitness of Police Academy Cadets: Baseline Characteristics and Changes During a 16-Week Academy. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2016, 30, 1416–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawes, J.J.; Orr, R.M.; Siekaniec, C.L.; Vanderwoude, A.A.; Pope, R. Associations between anthropometric characteristics and physical performance in male law enforcement officers: A retrospective cohort study. Ann. Occup. Environ. Med. 2016, 28, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Losty, C.; Williams, E.; Gossman, P. Police officer physical fitness to work: A case for health and fitness training. J. Hum. Sport Exerc. 2016, 11, 455–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Dawes, J.J.; Orr, R.M.; Flores, R.R.; Lockie, R.G.; Kornhauser, C.; Holmes, R. A physical fitness profile of state highway patrol officers by gender and age. Ann. Occup. Environ. Med. 2017, 29, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Violanti, J.M.; Ma, C.C.; Fekedulegn, D.; Andrew, M.E.; Gu, J.K.; Hartley, T.A.; Charles, L.E.; Burchfiel, C.M. Associations Between Body Fat Percentage and Fitness among Police Officers: A Statewide Study. Saf. Health Work 2017, 8, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orr, R.M.; Dawes, J.; Pope, R.; Terry, J. Assessing Differences in Anthropometric and Fitness Characteristics Between Police Academy Cadets and Incumbent Officers. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2018, 32, 2632–2641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima-Dos-Santos, A.L.; Domingos-Gomes, J.R.; Dantas Andrade, O.S.; Cirilo-Sousa, M.D.S.; Domingos da Silva Freitas, E.; Gomes Silva, J.C.; Galdino Izidorio, P.J.; Aniceto, R.R. Health-related physical fitness of military police officers in Paraiba, Brazil. Rev. Bras. Med. Trab. 2018, 16, 429–435. [Google Scholar]

- Lockie, R.G.; Dawes, J.J.; Kornhauser, C.L.; Holmes, R.J. Cross-Sectional and Retrospective Cohort Analysis of the Effects of Age on Flexibility, Strength Endurance, Lower-Body Power, and Aerobic Fitness in Law Enforcement Officers. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2019, 33, 451–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, C.J.; Orr, R.M.; Goad, K.S.; Schram, B.L.; Lockie, R.; Kornhauser, C.; Holmes, R.; Dawes, J.J. Comparing levels of fitness of police Officers between two United States law enforcement agencies. Work 2019, 63, 615–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frio Marins, E.; Cabistany, L.; Bartel, C.; Dawes, J.J.; Boscolo Del Vecchio, F. Aerobic fitness, upper-body strength and agility predict performance on an occupational physical ability test among police officers while wearing personal protective equipment. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fit. 2019, 59, 1835–1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Kim, J. A Comparative Analysis of Physical Fitness in Korean Police Officers: Focus on Results between 2014 to 2019. Exerc. Sci. 2019, 28, 396–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockie, R.G.; Dawes, J.J.; Orr, R.M.; Dulla, J.M. Recruit Fitness Standards from a Large Law Enforcement Agency: Between-Class Comparisons, Percentile Rankings, and Implications for Physical Training. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2020, 34, 934–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukić, F.; Lockie, R.G.; Vesković, A.; Petrović, N.; Subošić, D.; Spasić, D.; Paspalj, D.; Vulin, L.; Koropanovski, N. Perceived and Measured Physical Fitness of Police Students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caetano, H.B.S.; Israel-Caetano, C.; López-Gil, J.F.; Sentone, R.G.; Godoy, K.B.S.; Cavichiolli, F.R.; Paulo, A.C. Physical fitness tests as a requirement for physical performance improvement in officers in the military police of the state of Paraná, Brazil. Rev. Bras. Med. Trab. 2021, 18, 444–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lockie, R.G.; Dawes, J.J.; Orr, R.M.; Dulla, J.M. Physical fitness: Differences between initial hiring to academy in law enforcement recruits who graduate or separate from academy. Work 2021, 68, 1081–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).