Abstract

In order to prevent or at least reduce the deformation of road surface, it is necessary to ensure adequate water permeability of the structural layers and control of groundwater level. In geotechnical engineering, the water permeability of the mineral aggregates or soils is determined using a constant head water permeability apparatus. In order to assess the suitability of the results, it is necessary to take into account particle size distribution of the test object and perform the test at different hydraulic ramps. The aim of this research is to define and clarify unbound mineral aggregate mixtures hydraulic gradient and compaction level of road layer impact on water permeability. The following properties have been determined during the tests: particle size distribution, particle density, Proctor density, optimum water quantity, water permeability under different compaction and hydraulic slopes. Based on the results of the research, low-dustiness non-bonded mineral materials are recommended for frost resistant layers. For the water-permeability coefficient test, it is recommended that the test layer should be compacted to a design compaction ratio and the hydraulic gradient should not be higher than 1.0. Other conclusions and recommendations for further research and for improvement of water permeability functionality in the road pavement are presented.

1. Introduction

When designing a road pavement structure, it is important to evaluate the maximum permissible vertical tension on the surfaces of the unbound base and subgrade layers by reducing the permissible deformations. It has been recognized that the performance of flexible and rigid pavements is also closely related to the characteristics of unbound layers and subgrade. For example, total rutting in flexible pavements is marginally sensitive to resilient modulus and soil water characteristic curve of unbound layers and subgrade, but non-sensitive to thickness of unbound layers and load-related cracking in flexible pavements marginally sensitive to soil water characteristic curve of subgrade [1].

The main functional parameters (tension and deformation) of the non-rigid pavement constructions are highly dependent on the properties of cold-resistant layers and subgrade soil. A large part of the pavement surface deformations are conditioned by inadequate subgrade layer and its bearing capacity due to excessive water content. Raised groundwater level increases both the resilient and the permanent strains in all unbound layers above groundwater level in the pavement structure [2]. Therefore, it is very important that the subgrade would be protected from irrigation from the pavement structure and from the groundwater. For this purpose, the groundwater level should be lowered by assuring required elevation of road structure, the transverse profile of the subgrade surface should be sufficient, the permeability of the unbound base layers, which is determined by many circumstances [3], by using frost non-susceptible soils should be ensured and drainage or insulating layers should be installed [4].

When designing road constructions, the deformation modules of subgrade and unbound layers are one of the main input data. However, most structural design programs that use mechanical-empirical calculations do not evaluate the potential change in layer properties in the horizontal direction. For this reason, the addition of subgrade soils in the calculations should take account into the changes of properties. High stress amplitudes cause the layer sedimentation and reduction of bearing capacity. Soils, having bad cohesion parameters, have nonlinear and non-elastic properties.

The subbase course is generally located on the bottom of base course and laid on the top of subgrade, which plays a role of spreading the load over the subgrade. However, the subbase course is usually not used unless heavy traffic is involved, or the subgrade is weak. In fact, the subbase courses usually are typically studied together with the base course, therefore, the influence of subbase course on pavement performance is correspondingly slight compared to the base course, especially for the inherent mechanism [5]. The functionality of unbound layers, exclusively for the protective frost-resistant layer, depends on the following components: material type and type (particle size distribution) for the application of the deposited layer, material origin, contamination (fines less than 0.63 mm), compaction grade, layer thickness, hydraulic slope in this layer.

2. An Overview of the Scientific Work Related to the Water Permeability Functionality in Road Construction

An extremely important indicator is the degree of saturation of the material, which characterizes the overall effect of compaction and water content on the layer. The bearing capacity of the layer is strongly correlated with this indicator: with increasing degree of saturation, the bearing capacity decreases. Thus, in the case of a large amount of water in the layer, or as the compaction rate decreases (with an increase in air voids), the bearing capacity index and the modulus of elasticity of layer are reduced.

There are many ways for water to get into the road structure: rising groundwater levels, surface water movement through ditches, cracks in road pavement layers. In many roads, ditches are very inclined, or drainage systems are not designed to drain large amounts of water, so the water level in ditches can rise and penetrate into the road structure during heavy rainfall [6].

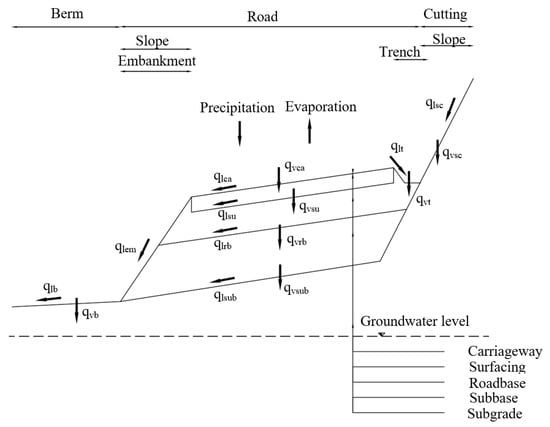

The balance of water (or other liquids) in the road structure depends on its geometrical parameters and longitudinal slope. The amount of running water on roads with a pavement structure above the existing ground level is different from that, where the road surface is below of the existing ground level or in tunnels. A detailed water balance model for each component of the road construction with water streams is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model of water balance on pavement–embankment system: v—vertical, l—lateral, ca—carriageway, su—surfacing, rb—roadbase, sub—sub-base, sc—slope/cutting, t—trench, em—embankment, b—berm [7].

According to research conducted by Marshall R. Thompson, Erol Tutumluer and Manuel Bejaran [3], the impact of water on different soils has different effects on the reduction of elastic modulus, e.g., 1.0% water increase in clays, the soil elastic modulus is reduced to 0.7%, while the 1.0% increase in clay sand reduces the soil elastic modulus to 2.1%. From this it can be stated that the low water permeability of the layer (in this case the subgrade) causes the modulus of elasticity and the bearing capacity to decrease by maintaining the amount of water in the layer.

Water is a polar material; water molecules have positive and negative polar particles. This allows water particles to connect to the surface of the mineral materials. Also, the water migrates to the air voids of the layers due to capillary traction if the voids are small enough. It depends on the particle size distribution of the mineral material, and the amount of small fractions. For hydraulically unbound layers, a small amount of water can strengthen the layer: The water film on the granules of individual mineral material affects the shear resistance [8]. After reaching the degree of saturation of the mineral material mixture, repetitive loads can cause a positive effect of water pressure in the voids. However, too much water in the voids of mineral mixtures causes too much pressure on the pellets of the mixture: This reduces the overall resistance of the material to long-term deformation. the resilient modulus of unbound granular base increases with an increased water content below the optimum water content, but has opposite effect if water content was above the optimum water content [5]. Thus, it can be said that the low water permeability of the hydraulically non-bonded substrates (in this case mineral blends) increases the overall resistance of the material to long-term deformation while maintaining the water content in the air voids of the material.

The high content of the fine fraction in the mineral material fills the air voids, preventing them from being filled with water, and reduces water permeability, which can cause excessive loads of water in the air voids to pellets. However, the impact of small fractions on the bearing resistance, when layer water content is increasing, has no significant impact.

The highest water impact on elastic properties is occurred in fine-grained mineral materials with a high content of small fractions. According to Araya [7], the effect of water on multi-grain and coarse-grained minerals has little effect on the elastic properties: Mineral materials elastic properties are mainly influenced by the skeleton of the mineral material.

It has been found that water pressure tends to separate mineral particles from one another, causing slipping [9]. This least to a deformation between material particles that can cause additional tension between material components. If the material is not completely saturated, the water tends to accumulate at the point of contact of the particles, and the tensile strength of the water surface increases the adhesive properties of the particles. Not even under external loads, the particles are subjected to water-induced capillary pressure, which causes shear stress. This interaction, often referred to as adhesion, disappears when the material is saturated and the pressure in the pores becomes positive—pressure begins to interact with the components of the material from the inside, pushing the walls of the pores and giving additional tension. This principle applies not only to coarse-grained soils or mineral materials with a high relative air void content, but also to many materials, having high amount of fines, but only in limited water content in air voids. Saturated fine-grained soils or mineral materials tend to act as viscous liquids. This limit, when the material loses the properties of the solid aggregate, is called the fluidity limit, when the negative effect of water reduces the interaction of the particles of the material.

The top layers of road structure are also exposed to moisture. In the case of repetitive humid weather conditions, cracks caused by water pressure in the air voids may occur when it is affected by the traffic impulses, loads, and vibrations. The water in these cracks can reduce the adhesive properties of the bituminous binder and the mineral material: This reduces adhesion between the separated layers, increases wear, and friction inside the layer. In addition, the water can reduce adhesion between the different bonded layers of the structure, which would reduce the load bearing capacity of the structure in the case of interlayer cracks.

Another cause of deformation in road construction is seasonal water freezing. Ice particles can occur between the frozen road pavement layers and the frozen subgrade soil. For this reason, subgrade soils can move tens of centimeters in the winter season, despite that there are no problems of the load-bearing capacity since pavement structure freezes in and its load-bearing capacity exceeds 100% [4]. In addition, subgrade resilient modulus decreases exponentially with increasing number of freeze-thaw cycles [10]. In spring, the ice melts from the upper layers of the structure, where the coating is exposed to direct warming factors. However, the ice in the lower layers does not pass water that has dissolved at the top, so non-degenerating water can severely damage road construction and affect its strength: Load-bearing capacity decreases even to 30% depending on the type of soil. In autumn when moisture increases the load-bearing capacity decreases to almost 70%. With the decreased amount of precipitation in summer the soils dry out, become waterless and their load-bearing capacity is again 100% [4]. Wetting and drying has a significant effect on both the resilient modulus and on the development of permanent strain. It is therefore important within an analytical pavement design procedure to ensure that material parameters and models of material performance have been characterized under conditions which adequately replicate those found in the field, including under conditions of wetting and trying [11].

3. Generally Accepted Principles for Testing Water Permeability of Road Pavement Structures

Water, having both kinetic and potential energy, flows through porous layers of material from one point to another, where this energy will already be lower [12]. The kinetic energy depends on the speed of the fluid, but the potential energy depends on the properties of the material or layer, their position and the pressure of the liquid. When water moves between two points, a certain amount of energy is lost, pressure is reduced.

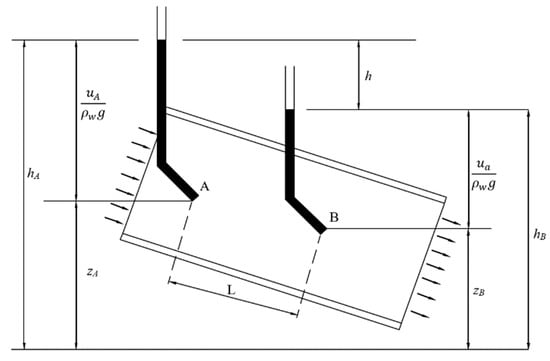

From the experiment shown in Figure 2, the Bernoulli energy equilibrium equation between points A and B is expressed:

where u and v are the liquid pressure and velocity respectively, z is the distance from the zero line and ∆h is the pressure change between points A and B, which creates the flow.

Figure 2.

Head loss as water flows through a porous media [7].

Since the velocity of water in the porous material is low, they can be rejected. The pressure difference can then be expressed as:

Darcy’s law states that water permeability (also known as hydraulic permeability) is a change in pressure across a body of a certain length:

or taking into account the very small size of the elements:

where dh is the change in pressure of infinitely small elements at an extremely low distance dL, and i is the hydraulic pressure of the flow in the flow direction. This equality is known as the Darcy’s law and defines the water permeability of soils and mineral materials.

Taking into account the formula 2, it can be seen that better water permeability properties exist when:

- the cross-sectional area through which water flows is increased: this increases the number of air voids;

- hydraulic pressure is increased: it can be performed by installing deeper drains or better drainage systems;

- water permeability is increased, when coarser mineral material selected that creates more air voids in the layer for a water-permeable layer.

However, Darcy’s law only applies to laminar, irrational water flow in porous bodies. In the saturated layers, the water permeability coefficient can be considered constant throughout the layer skeleton, by rejecting the formation of water vortex which is minimal. Above groundwater levels in unsaturated layers, the Darcy law also applies, only water permeability becoming a function of water content.

- Unbound mineral material layers’ water permeability is dependent on the following factors:

- particle size distribution;

- number of air voids;

- structures and textures of soil or mineral material;

- density of soil or mineral material;

- water temperature [12].

For this reason, several empirical equations for water permeability have been proposed in the past. These equations include parameters that are directly related to the material’s particle size distribution or its air void content.

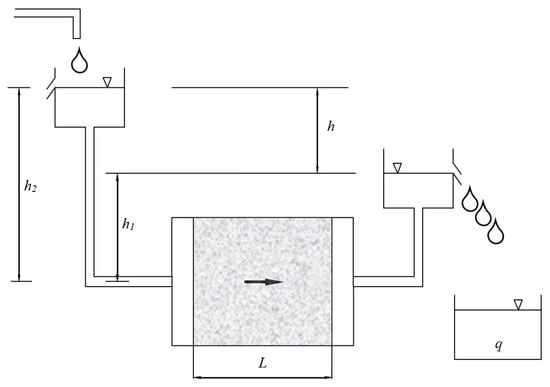

4. Water Permeability Test

Traditionally, in geotechnical engineering, the water permeability of the saturated material for coarse-grained and multi-grained soils and mineral materials is determined using a constant-pressure water permeability coefficient equipment and for fine-grained soils—a variable pressure equipment. For the constant-pressure water permeability test, sample is placed in a container that has water permeable filters, but does not change skeleton of the mineral material or soil (see Figure 3). A constant pressure water flow is then allowed into this vessel, which passes through the entire volume of the sample. During the test, the amount of water passed is determined over a period of time.

Figure 3.

Scheme of constant head permeability test.

After reconfiguring and replacing certain indexes in formula 5, the water permeability coefficient is equal to:

where A is the area of the cross-section of the vessel through which the liquid passes through a period of time with hydraulic slope ∆h/∆L, where the hydraulic slope is the difference in hydraulic pressure ∆h at a distance ∆L, and k is a constant indicating the hydraulic permeability and depends on the type of the substance to be examined, its porosity, and the characteristics of the filtered liquid, especially its viscosity.

Usually, the Darsi flow estimates the water permeability regime in the soil or mineral material layers when the water reaches the boundary speeds and does not create vortex when water flows from small to larger air voids. This means that energy losses are only due to friction between the water and the surrounding particles, so the water permeability ratio can be determined. When the water permeability of coarse-grained materials with high air voids is determined by the equipment shown in Figure 3, it must be ensured that the Darcy law conditions are met.

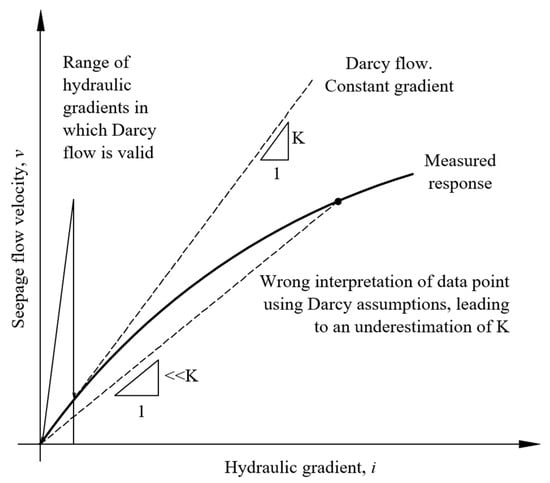

During the tests, standard conditions are accepted, one of which is hydraulic gradient. This condition is accepted at a much higher value than the options available in nature, for assurance of critical conditions on roads. If hydraulic slopes of this size are given to materials with high air voids, the vortexes may form in air voids, resulting in more energy being lost than provided by the Darcy flow. If the designer or researcher is unfamiliar with these conditions, the value of the water permeability coefficient will not be assessed adequately or correctly.

For this reason, tests should be carried out on different hydraulic slopes for coarse-grained and multi-grained soils and mineral materials. The required hydraulic gradient may be less than 0.1 to implement the Darcy law [13] as shown in Figure 4 [14].

Figure 4.

Limits of applicability of Darcy assumptions when testing at variable hydraulic gradients [14].

5. Test Object and Methods

According to the practice, unbound mineral material fraction 0/4 is most often used to install a frost-resistant protective layer. This is usually a mixture of screened non-washed sand from quarries. In order to evaluate the quality of this mixture, tests also performed on washed sand fraction 0/4. These test objects (screened non-washed and washed sands) were taken from 3 different quarries with 7 different specimens for each test object.

Experimental laboratory testing consists of the following steps:

- Investigation of the properties of mineral mixtures;

- determination of properties of mineral materials as a frost-resistant layer;

- research and analysis of water permeability.

The following properties have been determined for unbound mineral mixtures:

- Particle size distribution according to European Standard EN 933-1 [15];

- particle density according to European Standard EN 1097-6 [16].

With every specimen, 3 mentioned tests were made.

The following properties have been determined for unbound mineral materials as a frost resistant layer:

- Proctor compaction and reference density according to European Standard EN 13286-2 [17];

- reference water content according to European Standard EN 13286-2 [17];

- air voids according to European Standard EN 13286-2 [17].

With every specimen, 3 mentioned tests were made.

The water permeability values for the test objects during the water permeability test according to Technical Specification ISO/TS 17892-11 were:

- Standard conditions [6];

- with different compaction values (100.0%; 103.0%);

- different water hydraulic pressures.

With every mentioned condition, 5 tests were made with every specimen.

6. Results

Water permeability test results shows that the values of the washed sand are 3 times the value of the non-washed sand when the compaction rate is optimal; when the compaction rate is 103%, the value of the washed sand water permeability coefficient are 7 times the value of the non-washed sand. The results show that a 2% increase in mineral dust in the mixture has a significant impact on water permeability. Small particles affected by water fill the free air voids. This way the water flow is blocked, and the water permeability coefficient decreases.

Depending on the compaction, the value of the permeability water coefficient decreases with more compaction. It was found that the more compacted washed sand layers’ water permeability value drops to 33%. Meanwhile, the water permeability coefficient of the screened non-washed sand layer falls by 60%. From this it can be stated that smaller fraction sands are more sensitive to compaction if attention is paid to the functionality of water permeability. Compacting smaller fraction sands have better properties for greater compaction due to the ability of fine mineral particles to move into the voids of the empty air.

During the test according to CEN ISO / TS 17892-11: 2004 clause 4.3, it was found that, under identical test conditions and sand compacting, but with different hydraulic gradients, different results are obtained: the difference between the results of the same sample under the same conditions may vary up to 14.0% depending on the hydraulic gradient.

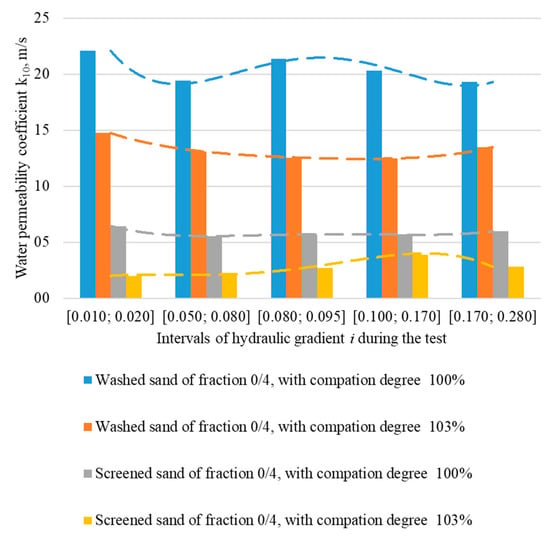

From Figure 5, it can be seen that the water permeability values do not correlate with the hydraulic gradient. Depending on the different materials and their different compaction, different dependencies are obtained: Dependence of the washed sand on the hydraulic gradient, when the degree of compaction is optimal, with the increasing hydraulic slope, the value of the water permeability decreases; with the average hydraulic gradient value of the water permeability increases and with the high hydraulic gradient the value decreases again. With a compaction of 103%, the increase in the hydraulic gradient results in a decrease of the value of water permeability, but it increases when hydraulic gradient is ≥0.10. The dependence of the screened non-washed sand water permeability coefficient on the hydraulic gradient when the degree of compaction is optimal is similar to washed sand, but the differences in values are much smaller: the values are rounded to the required accuracy, the results are almost identical. With 103% compaction, the value of water permeability of the screened non-washed sand increases as the hydraulic gradient increases; only with extremely high hydraulic gradient ≥0.17, these values decrease again.

Figure 5.

Water permeability coefficient value correlation with different the hydraulic gradient during test.

Considering variations in water permeability results, the highest variation in different hydraulic gradients was observed with more compacted mineral mixtures: screened non-washed sand compacted at 103% water permeability coefficient values doubled when the value of washed sand compacted at 100% decreased to 15%. Although the differences in results are not significant, the values of the different hydraulic gradients cannot be evaluated as a suitable factor for water permeability.

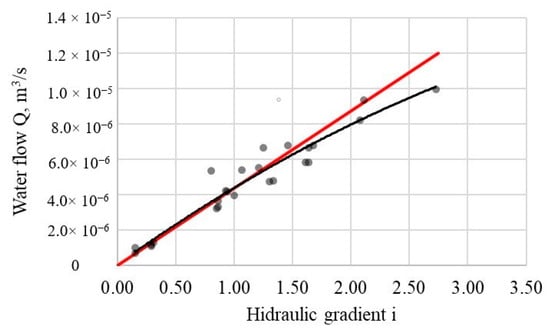

Based on the obtained results, it has been found to be particularly important to select suitable hydraulic gradient value for the water permeability test. It is important that the Darcy law is implemented: The flow rate of the spilled water must be linearly dependent on the value of the hydraulic gradient. This condition has been verified and an example of the results obtained is shown in Figure 6. With a large hydraulic slope, dependence becomes not linear, but the logarithmic—Darcy’s law is no longer valid. According to the results of the washed sand, it can be stated that the Darcy law is valid up to value of 1.0 of the hydraulic slope. The same dependency applies to different degrees of compaction.

Figure 6.

Dependency of flow rate of the spilled water through washed sand with optimal compaction on the different hydraulic gradients.

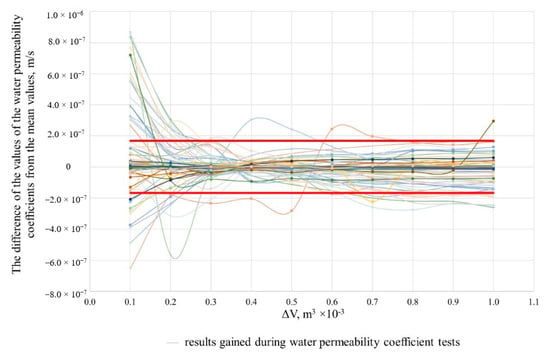

During the tests, it was found that different values of water permeability coefficient were calculated taking into account the amount of water passed through the sample at different stages of the test by measuring in accordance to CEN ISO / TS 17892-11: 2004 clause 4.3. The distribution of the values of the water permeability coefficients from the mean values, taking into account the stage when the data for the calculation of this coefficient were recorded, is graphically represented in Figure 7. The results show that at the beginning of the test, the first time recording has the highest deviation from the mean values. Calculating the standard deviation σ of the mean of all water permeability coefficient deviations from the mean coefficient values, with a confidence interval of 95%, is 1.67 × 10−7 m/s. Almost all values not within the 2σ range of 2 standard deviations are measured during the first test phase: when the first 100 mL of passing water is measured. This may be due to operator error or test equipment sensitivity.

Figure 7.

The distribution of the values of the water permeability coefficients from the mean values, taking into account the stage when the data for the calculation of this coefficient were recorded.

7. Conclusions

The basic functional parameters of road structure are highly dependent on the characteristics of the base and soil layers. For this purpose, the groundwater abasement must be ensured, a sufficient slope of the subgrade and the water permeability of the non-bonded structure layers, which is determined by many factors.

Low-fine content sand, which has 1.0% particles smaller than 0.063 mm has a 3 times bigger water-permeability coefficient than the sand containing 3.0% particles smaller than 0.063 mm at 100% compaction; at 103% compaction; the low-contamination mineral material has a water-permeability coefficient of 7 times bigger than the one having higher contamination.

It is recommended to evaluate the possibility of reducing water permeability control at the construction site when the design compaction ratio is reached and when there is a small amount of fines in mineral material of frost resistant layer—percentage of passage through a 0.063 mm sieve ≤ 3%.

In the standard CEN ISO/TS 17892-11: 2004 for defining water permeability coefficient test, several key parameters (sample density during test and hydraulic gradient) are not defined.

During the test the influence of the hydraulic gradient on the water permeability coefficient is negligible when hydraulic gradient is up to 1.0; such conditions correspond to the law of Darcy based on Bernoulli’s equation.

It is recommended to use as low as possible low-dustiness non-bonded mineral materials for frost resistant layers, and for the water-permeability coefficient test, it is recommended that the test layer should be compacted to a design compaction ratio, hydraulic gradient should not be higher than 1.0 and the time value for the first collected water volume measurement should be rejected, thus increasing the accuracy of the results.

In order to confirm research finding suitability for wide particle size distribution aggregates mixtures or soils we recommend to test samples of 0/16, 0/22 fractions. It is also recommended that studies be carried out to assess the effect of fines (less than 0.063 mm) on water permeability in mineral blends of fr. 0/16 fr. 0/22, fr. 0/32.

Author Contributions

Supervision, A.V.; Writing–Original Draft, V.F.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Luo, X.; Gu, F.; Zhang, Y.; Lytton, R.L.; Zollinger, D. Mechanistic-empirical models for better consideration of subgrade and unbound layers’ influence on pavement performance. Transp. Geotech. 2017, 13, 52–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erlingsson, S. Impact of water on the response and performance of a pavement structure in an accelerated test. Road Mater. Pavement Des. 2010, 11, 863–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, M.R.; Tutumluer, E.; Bejarano, M. Granular Material and Soil Moduli: Review of the Literature; ARRB: Port Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Vaitkus, A.; Vorobjovas, V.; Žiliutė, L.; Kleizienė, R.; Ratkevičius, T. Optimal selection of soils and aggregates mixtures for a frost blanket course of road pavement structure. Balt. J. Road Bridge Eng. 2012, 7, 154–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, N.; Xiao, F.; Wang, J.; Amirkhanian, S. Characterizations of base and subbase layers for Mechanistic-Empirical Pavement Design. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 152, 731–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO/TS 17892-11:2004 Geotechnical Investigation and Testting-Laboratory Testing of Soil-Part 11: Determination of Permeability by Constant and Falling Head; ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2004.

- Araya, A.A. Characterization of Unbound Granular Materials for Pavements. Ph.D. Thesis, IHE/TUDelft: Delft, The Netherlands, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Werkmeister, S. Permanent Deformation Behaviour of Unbound Granular Materials in Pavement Constructions; Plastisches Verformungsverhalten von Tragschichten ohne Bindemittel in Straßenbefestigungen. Ph.D. Thesis, TU Dresden, Dresden, Germany, 7 April 2003; 189p. [Google Scholar]

- Saevarsdottir, T.; Erlingsson, S. Effect of moisture content on pavement behaviour in a heavy vehicle simulator test. Road Mater. Pavement Des. 2013, 14, 274–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Chen, Z.; Ling, J. Performance-dependent Humidity State Division of Subgrade in Seasonal Frozen Region. Transp. Res. Procedia 2017, 25, 2182–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasul, M.; Ghataora, G.; Burrow, M. The effect of wetting and drying on the performance of stabilized subgrade soils. Transp. Geotech. 2018, 14, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cedergren, H.R. Drainage of Highway and Airfield Pavements; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1974; p. 285. [Google Scholar]

- Folkeson, L.; Swedish, N.R. Water in Road Structures; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2009; ISSN: 9781402085628. [Google Scholar]

- Filotenkovas, V.; Vaitkus, A. Assessment of Factors Determining Water Permeability of Base Layers in Pavement Structure on Traffic Zones. Sci. Future Lith. 2018, 10, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN 933-1:2012 Tests for Geometrical Properties of Aggregates-Part 1: Determination of Particle Size Distribution-Sieving Method; BSI: Brussels, Belgium, 2012.

- EN 1097-6:2013 Tests for Mechanical and Physical Properties of Aggregates-Part 6: Determination of Particle Density and Water Absorption; BSI: Brussels, Belgium, 2013.

- EN 13286-2:2010/AC:2013 Unbound and Hydraulically Bound Mixtures-Part 2: Test Methods for Laboratory Reference Density and Water Content-Proctor Compaction; BSI: Brussels, Belgium, 2013.

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).