Abstract

The carved lacquer horse-hoof-shaped box excavated from Yulin, Shaanxi Province, represents a typical example of lacquerware preservation in the arid environment of northern China, exhibiting multiple deterioration phenomena, including substrate deformation, lacquer film peeling, and pigment fading. To systematically analyze its structural composition and craftsmanship features, this study employed multiple analytical techniques, including ultra-depth microscopy, scanning electron microscopy with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (SEM-EDS), confocal laser micro-Raman spectroscopy (Raman), Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR), X-ray diffraction (XRD), and pyrolysis-gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (Py-GC/MS). Based on these analyses, a targeted conservation protocol was developed. Results revealed that the carved lacquer horse-hoof-shaped box has a wooden substrate structure, with the lacquer ash layer composed of mixed materials, including calcium carbonate (CaCO3), quartz (SiO2), and hydroxyapatite (Ca10(PO4)6(OH)2). The lacquer film layer contains Chinese lacquer and plant oils, with cinnabar applied as surface decoration. Based on these findings, a stratified reinforcement conservation strategy was proposed: under dynamic monitoring with optical fiber sensors and three-dimensional scanning, the wooden substrate was reinforced with moisture-curable polyurethane (MCPU), the lacquer ash layer was strengthened with acrylic emulsion (Primal AC33), aged areas were restored with nano calcium hydroxide (Ca(OH)2) aqueous dispersion, and polyethylene glycol (PEG 400) poultice application was implemented to restore the flexibility of the lacquer film. This research significantly enhanced the integrity and stability of the carved lacquer horse-hoof-shaped box, providing practical evidence and technical references for the scientific conservation of lacquerware excavated from arid regions of northern China.

1. Introduction

Lacquerware represents an important carrier of China’s excellent traditional culture, with a long history of utilization [1]. Current archeological evidence indicates that Chinese lacquerware dates back approximately 8000 years [2], witnessing the evolution of ancient Chinese craftsmanship and civilization. However, due to the influence of regional burial environments, most lacquerware unearthed from archeological sites in northern China exists only as lacquer film remnants, with complete objects being extremely rare. This poses serious challenges to the systematic understanding of ancient lacquerware craftsmanship and its conservation [3]. Yulin City is located in the central part of the Loess Plateau, characterized by a temperate continental monsoon climate with significant annual and diurnal temperature variations and dramatic fluctuations in environmental humidity [4]. These burial conditions easily lead to irreversible deterioration of organic substrates and lacquer films in lacquerware due to water loss and shrinkage [5]. Excavated lacquerware often exhibits an overall desiccated state, characterized by substrate decay and powdering, curling and detachment of lacquer films, and other deterioration phenomena [6], severely constraining the interpretation and inheritance of their historical, artistic, and scientific values. The carved lacquer horse-hoof-shaped box from Yulin, Shaanxi Province, examined in this study is a typical example of this issue. Its surface is primarily covered with brownish lacquer layers, with sporadic red patches remaining, preliminarily identified as remnants of cloud-and-mist patterns. The entire lacquer box exhibits multiple deterioration phenomena, including substrate deformation and fracture, lacquer layer detachment, lifting, discoloration, and curling (Figure 1). Using this lacquer box as the research subject, this study employs multiple analytical techniques, including ultra-depth microscopy, scanning electron microscopy with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (SEM-EDS), Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR), X-ray diffraction (XRD), confocal laser micro-Raman spectroscopy (Raman), and pyrolysis-gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (Py-GC/MS), to comprehensively analyze its microstructure, material composition, and manufacturing techniques. Based on these findings, we aim to develop a scientific and reliable conservation protocol suitable for desiccated lacquerware from northern China, providing practical evidence and technical references for the long-term preservation and subsequent research of such fragile cultural relics.

Figure 1.

Photos of the carved lacquer horse-hoof-shaped box: (a) Front view; (b) Top view.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Materials

Experimental samples were taken from the carved lacquer horse-hoof-shaped box excavated in Yulin, Shaanxi Province, comprising detached fragments containing complete structural elements.

2.2. Experimental Instruments and Methods

2.2.1. Ultra-Depth Microscopy

A Smartzoom 5 (Zeiss, Jena, Germany) ultra-depth microscope was used to observe the surface, back, and cross-section of the lacquer box samples. Testing conditions: magnification 20×–50×, with a carrier stage equipped with a high-brightness LED transmission light and ring light source; images were acquired through depth synthesis.

2.2.2. Scanning Electron Microscopy with Energy-Dispersive X-Ray Spectroscopy (SEM-EDS)

An Apreo S (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) scanning electron microscope coupled with a X-MAX 20 (Oxford Instruments, High Wycombe, UK) X-ray energy-dispersive spectrometer was used to analyze the microstructure and elemental composition of the lacquer ash layer. Testing conditions: compound lens, acceleration voltage 8 kV, low vacuum environment, working distance 15 mm, with sample surface carbon-coated; EDS analysis conditions: SuperATW window, 20 mm2 active area, resolution better than 127 eV, elemental analysis range Be4–U92.

2.2.3. Confocal Laser Micro-Raman Spectroscopy (Raman)

An inVia (Renishaw, Wotton-under-Edge, UK) confocal laser micro-Raman spectrometer was used to analyze the composition of red pigments. Testing conditions: semiconductor laser, wavelength 785 nm, grating 1200/mm, exposure time 10 s, power 3 mW, spatial resolution 1 μm, accumulation count 1.

2.2.4. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FT-IR)

A LUMOS (Bruker, Bremen, Germany) FT-IR spectrometer was used to analyze the organic composition of the lacquer film layer. Testing conditions: range 4000–500 cm−1, 16 scans, resolution 4 cm−1, with samples prepared using the KBr pellet method.

2.2.5. X-Ray Diffraction (XRD)

A D8 Advance (Bruker, Bremen, Germany) X-ray diffractometer was used to analyze the phase composition of the lacquer ash layer. Testing conditions: copper target, tube voltage 40 kV, tube current 40 mA, scanning speed 0.2°/s, scanning range 5–90°.

2.2.6. Pyrolysis-Gas Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry (Py-GC/MS)

An EGA-PY3030D (Frontier, Tokyo, Japan) multifunctional pyrolyzer coupled with a GCMS-QP2020NX gas chromatograph/mass spectrometer (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) was used to detect organics in the lacquer film layer. An HP-5MS capillary column (30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 μm) was employed with a quadrupole mass spectrometer and an electron impact ionization source (70 eV). Online derivatization was applied by placing less than 1 mg of sample with 5 μL methylation reagent (25% tetramethylammonium hydroxide in methanol) in a sample boat before inserting it into the pyrolyzer tube. The sample pyrolysis temperature was 600 °C with a duration of 0.2 min; the sample methylation reaction occurred simultaneously with pyrolysis. The GC inlet temperature was 300 °C with split injection (split ratio 40:1) using helium as carrier gas (flow rate 1.0 mL/min). The column temperature program began at 40 °C (held for 3 min), then increased at 10 °C/min to 140 °C, followed by 20 °C/min to 310 °C (held for 15 min). The pyrolyzer–GC interface temperature was 310 °C, the MS ion source temperature was 230 °C, and the acquisition time ranged from 2.3 to 36.5 min, with a scan range of 29–600 m/z. Component identification was performed using the NIST20s libraries.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Sample Analysis

3.1.1. Structural Analysis

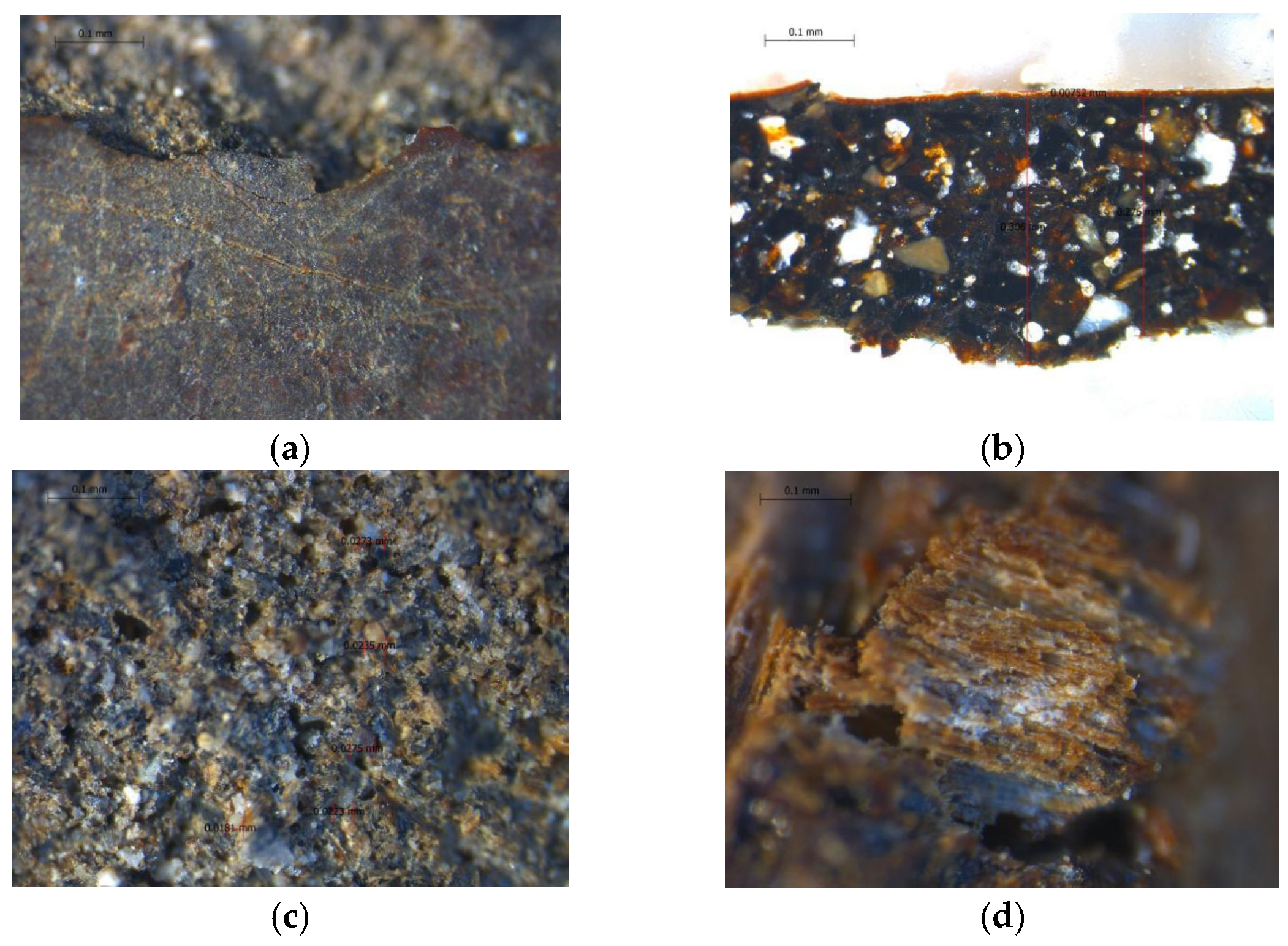

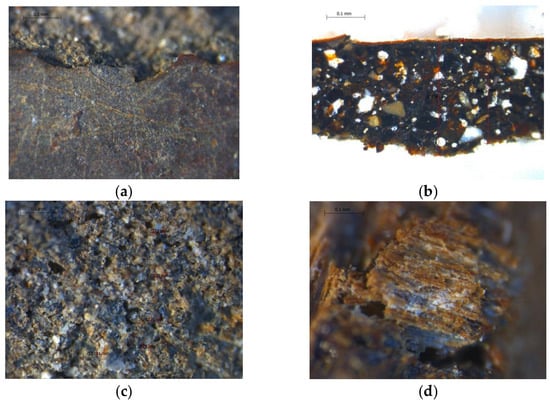

Fine crack patterns were observed on the base lacquer surface of the sample (Figure 2a), with irregular orientations and widths of approximately 1–2 μm, likely resulting from long-term drying and shrinkage. Local areas exhibited mechanical wear and linear scratches, indicating external force erosion during historical use or burial. Cross-sectional observation (Figure 2b) revealed the typical three-layer structure of lacquerware [7], with the remaining lacquer film having an overall thickness of approximately 0.3 mm, reflecting the exquisite craftsmanship and excellent physical durability of raw lacquer [8]. The structure of the lacquer box can be specifically divided into the following: the outermost layer consists of a pigment layer with sparse remaining red particles; beneath this is a blackish-brown lacquer film layer approximately 0.00752 mm thick; the middle layer is a grayish-white lacquer ash layer used to enhance substrate smoothness and improve lacquer film adhesion, with a thickness of approximately 0.2–0.25 mm; and the innermost layer is the wooden substrate, showing clear longitudinal wood fiber textures, primarily providing structural support. Further microscopic observation of the lacquer ash layer (Figure 2c) revealed mineral particles with diameters of 0.018–0.028 mm evenly distributed within the matrix. These particles have distinct angular edges and morphological features consistent with artificially ground additives, preliminarily identified as quartz or bone ash. The back of the sample clearly shows wood fiber traces (Figure 2d), with a small amount of mineral particles attached to the surface. The fibrous fractures at fiber breakage points further confirm the wooden nature of the inner layer.

Figure 2.

Microscopic observation of sample structure: (a) Surface; (b) Cross-section; (c) Cross-section of lacquer ash layer; (d) Back fiber.

3.1.2. Pigment Layer Analysis

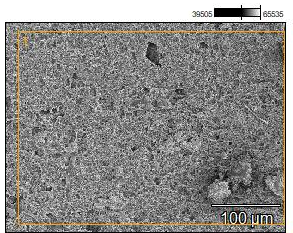

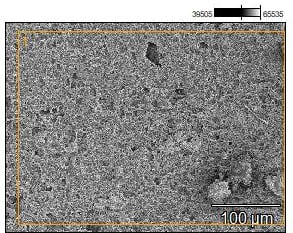

SEM observation results (Figure 3) show that the surface structure of the lacquer film is relatively loose, with irregular granular protrusions and accompanied by local lacquer film detachment and numerous micro-cracks, indicating poor overall preservation. Although red particles were identifiable on the lacquer film surface under microscopy, the overall coloration appears dark brown. To determine the elemental composition of these particles, X-ray energy-dispersive spectroscopy was performed on representative areas of the lacquer film surface, with the corresponding elemental contents shown in Table 1. In addition to the main elements C, O and N, the spectrum detected the presence of Hg and S elements. Combined with the chemical characteristics of cinnabar (HgS), this suggests that the surface of the lacquer film retains traces of cinnabar pigment.

Figure 3.

SEM image of lacquer film layer.

Table 1.

Elemental analysis results of lacquer film layer.

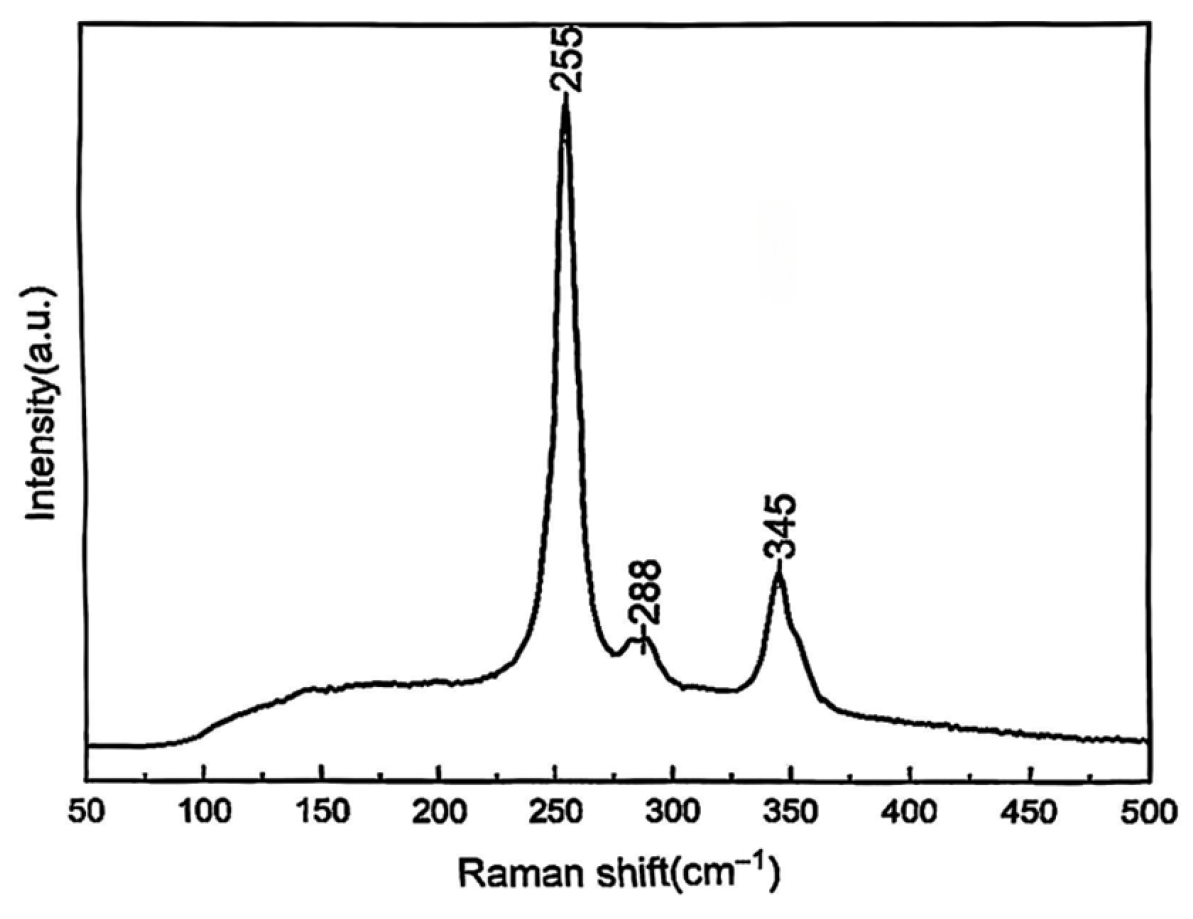

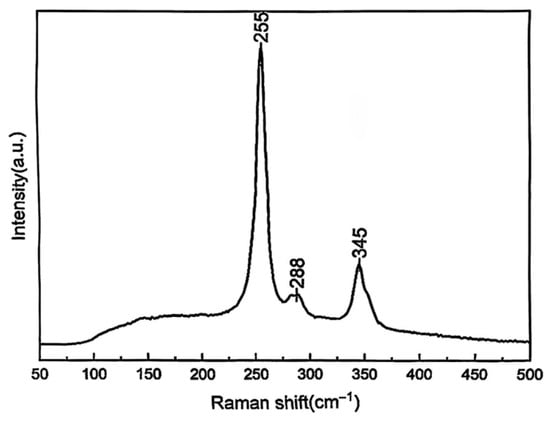

To determine the chemical composition of the residual red particles on the lacquer film surface, micro-area analysis was performed using Raman spectroscopy, with results shown in Figure 4. The characteristic peaks at 255 cm−1, 288 cm−1, and 345 cm−1 highly correspond with the standard spectrum of cinnabar (HgS), where 255 cm−1 corresponds to the stretching vibration of the Hg–S bond, while 288 cm−1 and 345 cm−1 are attributed to the symmetric bending vibrations of sulfur atoms in the HgS crystal lattice [9]. These analytical results corroborate the EDS detection of Hg and S elements, confirming that the red pigment is cinnabar (HgS). The strong Raman scattering signal of cinnabar, along with its characteristic absorption in the 550–650 nm visible light range that produces its distinctive red hue, further supports the reliability of this compositional identification. Historical records indicate that cinnabar was a commonly used red pigment in ancient polychromy [10], known for its good chemical stability and weatherability. However, the uneven distribution of cinnabar in the sample and the darkening of local colors suggest degradation resulting from long-term burial processes, including material decomposition, sulfide oxidation, and pollutant deposition [11], reflecting the complex aging phenomena of ancient organic–inorganic composite materials in burial environments.

Figure 4.

Raman spectrum of red pigment.

3.1.3. Lacquer Film Layer Analysis

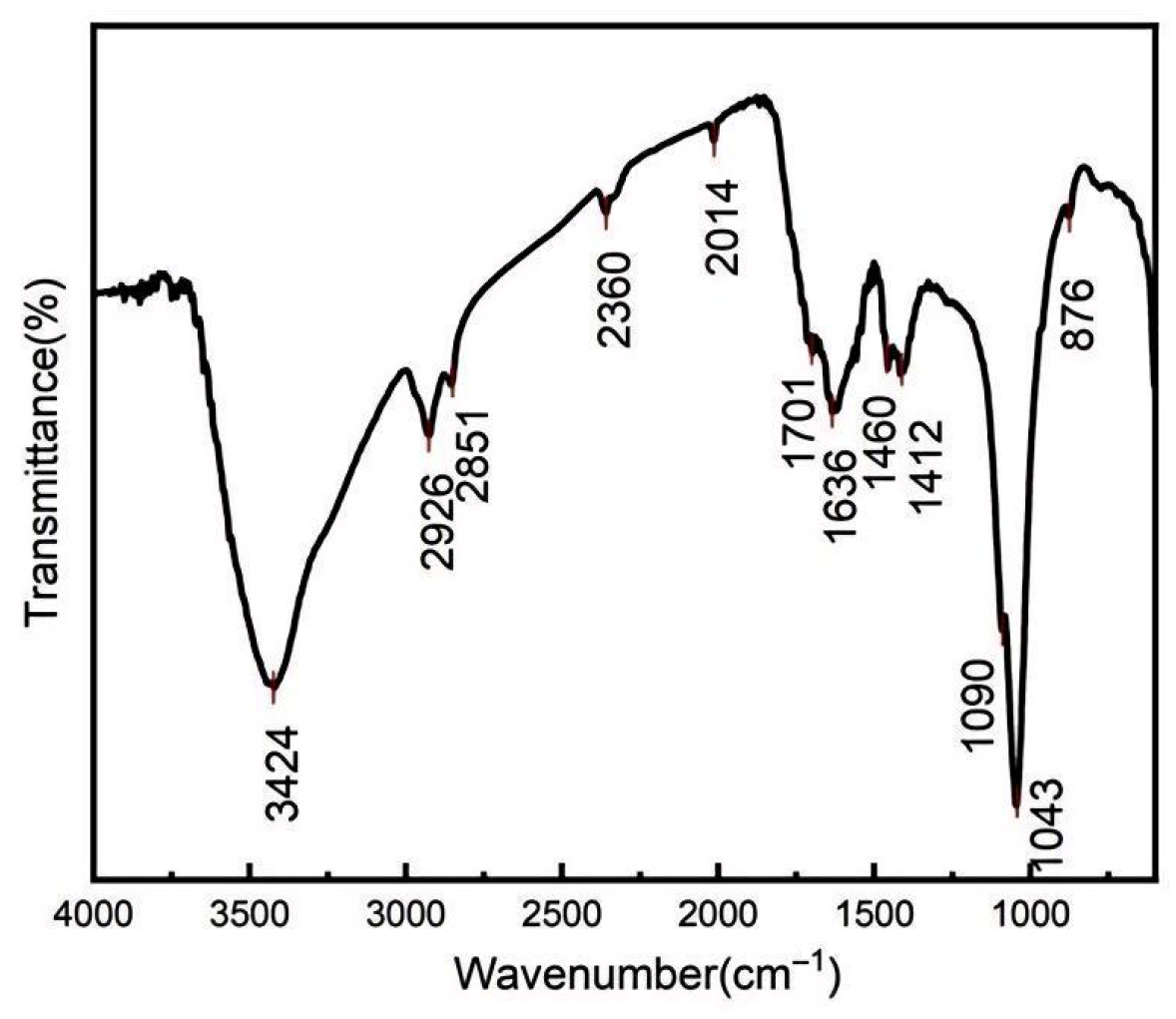

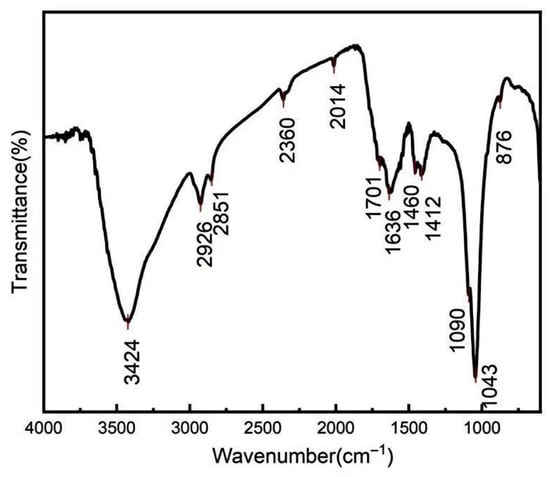

To verify whether natural lacquer was used as the film-forming substance in the lacquer film layer, Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy analysis was performed on the sample, with results shown in Figure 5. The absorption peak at 3424 cm−1 is attributed to the stretching vibration of hydroxyl groups (-OH) on the urushiol benzene ring, an important characteristic peak of raw lacquer [12]; the absorption peaks at 2926 cm−1 and 2851 cm−1 correspond to the asymmetric and symmetric stretching vibrations of methylene groups (-CH2-) [13], reflecting the presence of urushiol’s long-chain aliphatic structure; and a weak carbonyl (C = O) absorption peak appears near 1701 cm−1, while the absorption peak at 1636 cm−1 is significantly stronger. This peak is attributed to the C-C skeleton vibration of the urushiol benzene ring. The intensity contrast between these peaks indicates that tung oil was not added to the sample [14]; the absorption peaks at 1460 cm−1 and 1412 cm−1 correspond to the bending vibrations of methyl and methylene groups [15]; the absorption peaks at 1090 cm−1 and 1043 cm−1 are related to the stretching vibrations of ether bonds (C-O-C) [16]; the absorption at 876 cm−1 corresponds to the ortho-disubstituted pattern of the urushiol benzene ring [14]. Comprehensive analysis indicates that the main infrared absorption peaks of this lacquer film sample highly match those of urushiol (one of the main components of raw lacquer), confirming that it primarily uses natural raw lacquer as the film-forming substance, consistent with the typical chemical composition of traditional East Asian lacquer films. These results not only molecularly confirm the craft attribute of using natural raw lacquer in this lacquer box but also provide a basis for further investigation of its material aging mechanisms.

Figure 5.

FT-IR spectrum of lacquer film layer.

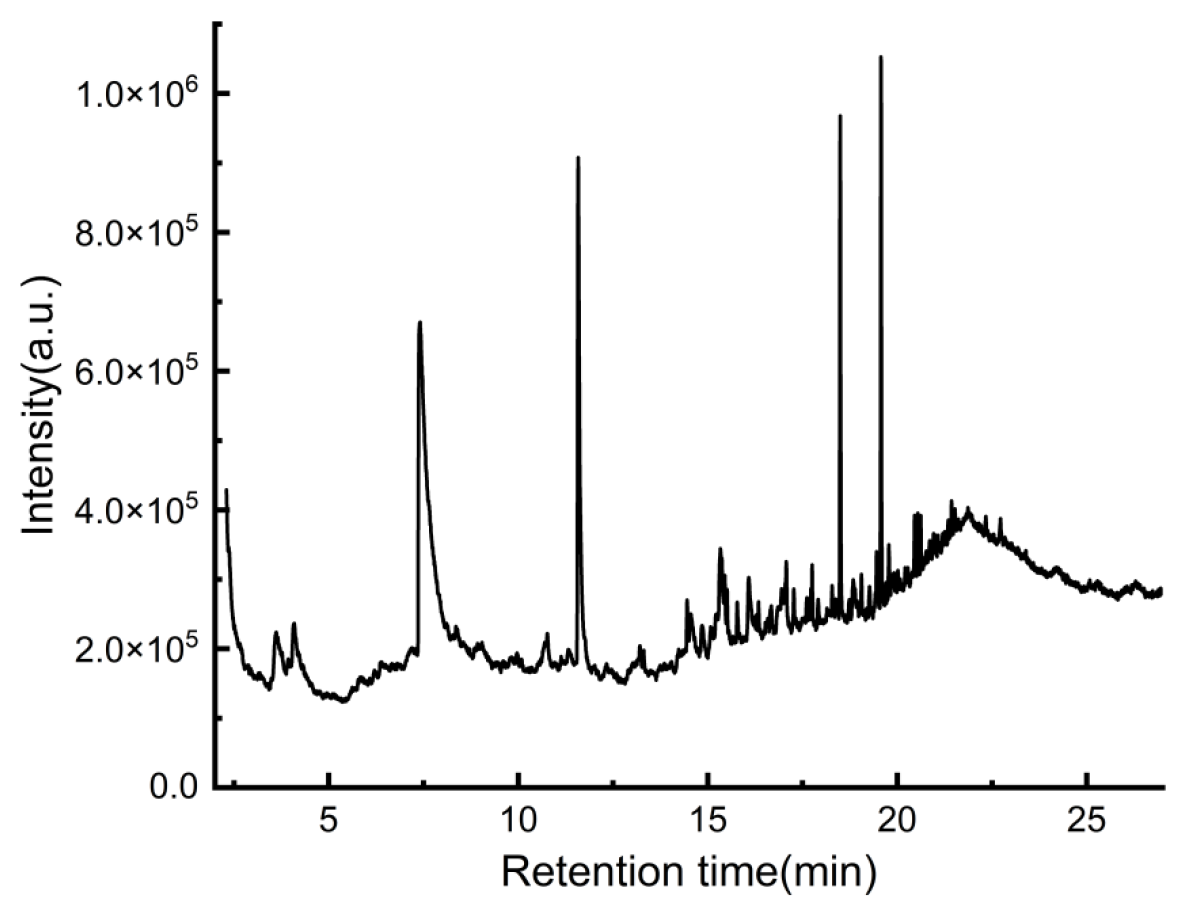

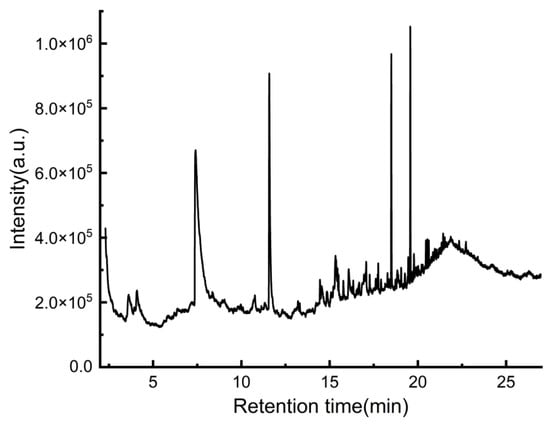

To further clarify the type of raw lacquer used and whether drying oils were added, pyrolysis–gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (Py-GC/MS) analysis was performed on the lacquer film layer, with the resulting spectrum shown in Figure 6 and relevant component identification results listed in Table 2. Due to online methylation treatment, the mass spectrometry primarily detected methylated derivatives of components containing carboxyl or hydroxyl groups. The Py-GC/MS analysis results show that the pyrolysis products of the lacquer film include a series of alkanes, alkenes, benzene and its phenolic derivatives. Notably, the analysis detected C17 (Heptadecanoic acid, methyl ester), a characteristic pyrolysis product of Chinese lacquer after methylation, confirming the presence of laccol in the lacquer film. The ratio of azelaic acid (A) to palmitic acid (P) (A/P) was 0.25, further supporting the presence of laccol. Meanwhile, the lacquer film pyrolysis products also contained monobasic carboxylic acids such as palmitic acid and stearic acid, as well as dibasic carboxylic acids such as suberic acid and azelaic acid, indicating the addition of drying oils to the lacquer film. These oils likely served to adjust the fluidity of raw lacquer and improve the gloss of the lacquer film. The ratio of palmitic acid (P) to stearic acid (S) (P/S) was 1.05, falling within the characteristic range for tung oil (1.0–1.2), suggesting that at least tung oil was added to the lacquer film. However, no distinct FTIR signals corresponding to tung oil were observed, likely due to either minimal initial incorporation or significant degradation during long-term burial, resulting in residual levels below instrumental detection limits. Furthermore, methyl alkylphenyl alkanoates (APAs)—typically formed during the thermal processing of tung oil—were undetected in the pyrolysis products. This absence suggests the use of raw tung oil rather than heat-bodied tung oil, as the former exhibits superior penetration properties while the latter prioritizes gloss enhancement. This technological choice aligns with the functional requirements of the lacquerware’s corresponding structural components. Pyrolysis analysis further identified long-chain saturated fatty acids with C20, C22 and C30 carbon skeletons, including docosenamide—a chemotaxonomic marker specific to Brassicaceae seeds (e.g., rapeseed). Among the primary pyrolysis products of rapeseed oil, linoleic acid was not detected in its intact form due to >95% degradation at 600 °C, though its pyrolysis derivative, azelaic acid, was confirmed. Methyl linoleate was also absent due to complete thermal decomposition. The detection of methyl oleate and docosenamide corresponds to the characteristic fatty acid composition of rapeseed oil (50%–65% oleic acid, 1%–2% erucic acid) [17], thereby suggesting the presence of rapeseed oil in the lacquer film. Collectively, the lacquer film contains at least two plant-derived oils: tung oil and rapeseed oil. The combination of fast-drying, high-gloss tung oil with slower-drying, flexible rapeseed oil creates a balanced system that mitigates cracking risks in arid northern climates. This oil formulation likely reflects both local resource availability and empirical material optimization by ancient artisans. Notably, while raw tung oil reduces surface gloss, it enhances penetration and adhesion between the substrate and lacquer layers, which is crucial for maintaining interfacial cohesion in dry environments. As historically accessible materials in northern China, the selection of these oils not only demonstrates regional material characteristics but also highlights traditional workshop-level technological inheritance. This study provides substantial evidence for understanding material selection strategies, technological adaptations, and environmental influences in regional lacquerware production.

Figure 6.

Total ion chromatogram of lacquer film layer.

Table 2.

Py-GC/MS analysis results of lacquer film layer.

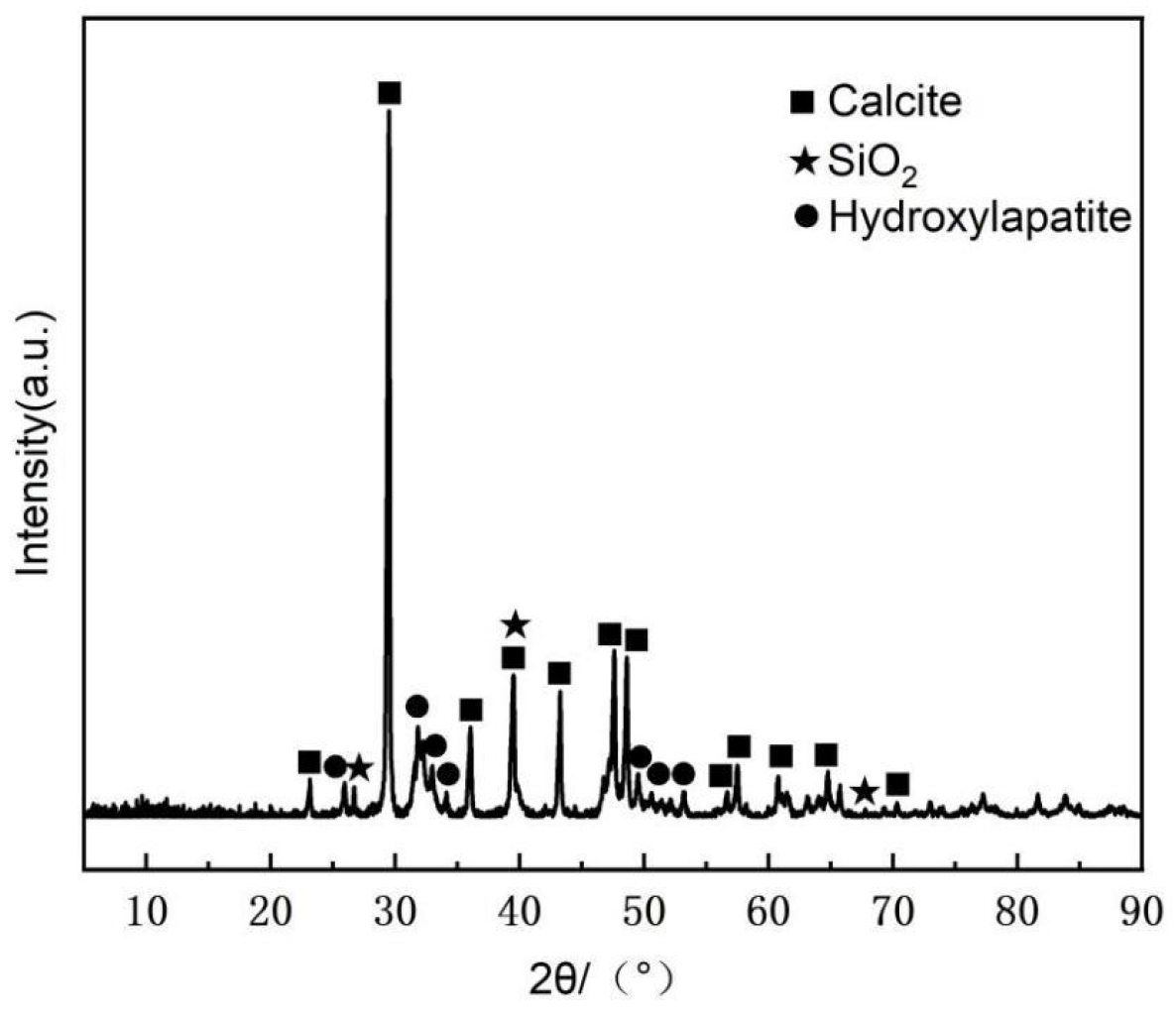

3.1.4. Lacquer Ash Layer Analysis

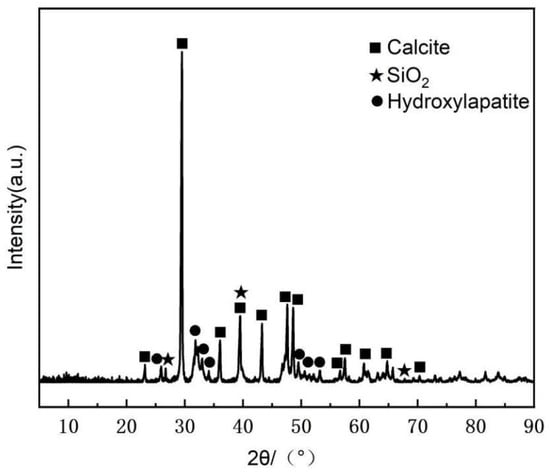

To analyze the material composition of the lacquer ash layer, X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis was performed on the sample, with results shown in Figure 7. The XRD pattern shows that the main phases in the lacquer ash layer are calcium carbonate (in the form of calcite), silicon dioxide (quartz), and hydroxyapatite, indicating that its filler composition includes calcite, quartz, and bone-antler ash. This finding aligns with historical descriptions of commonly used additives in ancient lacquerware production [7,18]. Among these, calcite and quartz function as mineral fillers, which not only reduce the flowability of the lacquer ash [19] but also enhance its density and abrasion resistance, thereby maintaining structural stability in arid environments. The incorporation of bone-antler ash further improves the flexibility and adhesion of the lacquer ash layer [20]. Its microporous structure may regulate the rate of moisture evaporation during the drying process, thereby mitigating cracking risks. This multi-component filler system reflects the profound understanding and skillful application of material properties by ancient artisans, balancing both processability and environmental adaptability for lacquerware. Additionally, the use of bone-antler ash may be associated with local pastoral resources, demonstrating an adaptive material selection strategy. These findings provide tangible evidence for interpreting the technological traditions and resource utilization background of lacquerware production in this region. It should be noted that XRD has inherent limitations in detecting amorphous-phase materials [21], and the potential presence of additional amorphous-phase additives in the lacquer ash layer cannot be excluded.

Figure 7.

XRD pattern of lacquer ash layer.

3.1.5. Craftsmanship Analysis

Based on the analysis results above, the structure of the Yulin carved lacquer horse-hoof-shaped box can be divided from inner to outer into four parts, wooden substrate, lacquer ash layer, lacquer film layer, and pigment layer, reflecting the integration of materials and craftsmanship in ancient Chinese lacquerware production. The substrate was made of dense hardwood to form the basic horseshoe-shaped framework, with a lacquer ash layer applied to the surface as a transition. The filler of this layer was mixed from calcite, quartz, and bone-antler ash, with a remaining thickness of approximately 0.25 mm, used to fill surface pores of the wood and improve overall smoothness. After the lacquer ash layer cured, a lacquer film layer was formed using a mixture of Chinese lacquer and plant oils, likely applied through multiple coating processes. The outermost pigment layer was decorated with cinnabar painting. Compared to other excavated lacquer boxes [22,23,24,25], this carved lacquer horse-hoof box exhibits distinct technological simplification features: significantly reduced lacquer film thickness and minimalist polychrome decoration. These characteristics should not be interpreted as technical limitations but rather as adaptive strategies developed in response to specific environmental conditions. The thin lacquer films not only mitigate cracking risks caused by uneven desiccation, but also reflect deliberate material optimization balancing protective functionality and stability in arid climates. While the exclusive use of cinnabar-based pigments may partially result from resource constraints and socio-hierarchical factors, it could equally represent localized esthetic preferences in visual expression. Crucially, the artifact retains fundamental technological integrity—the fillers in the lacquer ash layer still adhere to established principles for enhancing interfacial adhesion and crack resistance—demonstrating that artisans maintained structural integrity while streamlining surface treatments. This finding provides critical insights into technological transmission pathways, regional adaptation mechanisms, and socio-economic differentiation in lacquerware production under resource-constrained settings. It also underscores the necessity of adopting a multidisciplinary framework that systematically integrates environmental conditions, material availability, and socio-cultural influences when investigating lacquer technology evolution.

3.2. Conservation Measures

Based on a systematic analysis of the material characteristics and preservation status of the carved lacquer horse-hoof-shaped box, this study implemented a multi-level, multi-scale scientific conservation and restoration protocol. This protocol follows the principles of minimal intervention, reversibility, and re-treatability, adopting differentiated conservation measures for deterioration characteristics at different structural levels, aiming to restore the original form of the cultural relic and ensure its long-term preservation.

A structured-light 3D scanner (resolution: 0.05 mm, accuracy: ±0.02 mm) was employed for comprehensive scanning of the lacquer box through axial rotation at 15° angular intervals. The acquired data were processed using Shapr3D (Version 5.850, Shapr3D Zrt., Budapest, Hungary) to construct a digital deformation model, which was subsequently analyzed via finite element analysis (FEA) to determine optimal rectification force application points and correction magnitudes. In a constant-temperature and -humidity environment (25 °C, RH 60%), progressive physical correction technology was employed with custom silicone molds applying uniform pressure to deformed areas, gradually restoring the original curvature of the substrate while avoiding secondary cracking of the lacquer film due to stress concentration. For severely collapsed substrate structures, lightweight epoxy resin was used to fill internal voids, with carbon fiber mesh implanted to enhance overall toughness. After correction, reversible adhesives were used for temporary fixation, to be removed after the form stabilized.

Colorimetric analysis was conducted using a CM-700d (Konica Minolta, Chiyoda, Japan) spectrophotometer to quantify chromatic variations before and after consolidation. With the priority of selecting formulations that provided superior mechanical properties while maintaining colorimetric acceptability (ΔE < 2.0), a stratified consolidation strategy was implemented for the artifact: the underlying substrate was treated with 5%–10% moisture-curable polyurethane (MCPU) solution drip penetration [26] to enhance chemical bonding and mechanical strength between wood fibers; the lacquer ash layer was treated with layered spraying of 5% Primal AC33 aqueous solution [27] to fill micro-cracks and improve interlayer adhesion; the surface painted areas were locally bonded at the edges of detached cloud patterns using original raw lacquer materials [28], with microscopic restoration techniques employed to restore decorative details. For aged and embrittled areas of the lacquer film, nano calcium hydroxide dispersion was applied [29] to strengthen pore structures; subsequently, PEG 400 non-woven fabric was used for wet application treatment for 48 h under RH 85% [30] to restore the flexibility of the lacquer film and reduce the risk of stress damage during correction.

The entire conservation process was monitored in real-time using an FS-N18N (Keyence, Osaka, Japan) fiber optic strain sensor to track lacquer film deformation dynamics. Concurrently, Scaniverse (Version 4.0.6, Niantic Spatial, Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA) (Small Object mode) performed periodic 3D scanning to quantitatively evaluate rectification progress, ensuring full procedural control and adjustable precision. After treatment was completed, the lacquer box was stored in a constant-temperature and -humidity display cabinet (20 ± 1 °C, RH 50 ± 5%) [31], with a regular micro-environment monitoring and preservation status assessment mechanism established to build a systematic, sustainable preventive conservation system.

4. Conclusions

This study focused on the carved lacquer horse-hoof-shaped box excavated from Yulin, Shaanxi Province. By comprehensively employing multiple analytical techniques. including ultra-depth microscopy, scanning electron microscopy with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (SEM-EDS), confocal laser micro-Raman spectroscopy (Raman), Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR), X-ray diffraction (XRD) and pyrolysis-gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (Py-GC/MS), we systematically analyzed its structural composition and craftsmanship features and accordingly completed targeted conservation work. The main findings are as follows:

- (1)

- The carved lacquer horse-hoof-shaped box exhibits the typical three-layer composite structure of lacquerware, including a wooden substrate, a lacquer ash layer, and a lacquer film layer. The lacquer ash layer is primarily composed of calcium carbonate (CaCO3), quartz (SiO2), and hydroxyapatite (Ca10(PO4)6(OH)2). The lacquer film layer mainly consists of Chinese lacquer (laccol) and plant oils, with cinnabar (HgS) serving as the primary decorative pigment on the surface.

- (2)

- Under the influence of the arid burial environment in northern China, this artifact exhibited multiple deterioration phenomena, primarily including wooden substrate deformation and cracking, powdering and separation of the lacquer ash layer, cracking and embrittlement of the lacquer film layer, and fading and detachment of cinnabar pigments. These deterioration phenomena resulted from the combined effects of material aging and environmental factors.

- (3)

- A stratified reinforcement conservation strategy was implemented for this artifact: moisture-curable polyurethane (MCPU) was used to penetrate and reinforce the wooden substrate; acrylic emulsion (Primal AC33) enhanced the structural stability of the lacquer ash layer; nano calcium hydroxide filled deteriorated pores; and a polyethylene glycol (PEG 400) poultice application was implemented to restore the flexibility of the lacquer film. This approach achieved reliable protection for different materials, significantly improving the visual integrity and overall stability of the cultural relic.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Q.N. and Y.Q.; methodology, C.X. and Z.Z.; software, Y.C.; validation, H.Y. and J.C.; formal analysis, Y.C.; investigation, Q.N.; resources, J.C.; data curation, Y.Q.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.C. and Q.N.; writing—review and editing, Z.Z., C.X. and X.L.; visualization, Y.Q.; supervision, J.C.; project administration, Z.W. and X.L.; funding acquisition, Z.W. and X.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Social Science Fund of China (22BKG015), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (52203126), Archeological Talent Promotion Program of China (2025-207), Major Science and Technology Project of Gansu Province (25ZDFA014) and Xi’an Natural Science Foundation (2026JH-SZRJ-0272).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors sincerely thank Zhao Xing from the School of Cultural Heritage, Northwest University, for his valuable guidance and support of this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Fu, Y.; Chen, Z.; Zhou, S.; Wei, S. Comparative study of the materials and lacquering techniques of the lacquer objects from Warring States Period China. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2020, 114, 105060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, K.; Sun, G.; Zheng, Y.; Wu, M.; Zhang, B.; Zhu, L.; Hu, W. The earliest lacquerwares of China were discovered at Jingtoushan site in the Yangtze River Delta. Archaeometry 2021, 64, 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wu, H.; Song, J.; Shi, S.; Zhao, X.; Wang, N. Scientific research on a lacquer Lian from a Han tomb in Xianyang, Shaanxi. Sci. Conserv. Archaeol. 2024, 36, 58–65. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, X.; Huang, T. Spatiotemporal trends and variation of precipitation over China’s Loess Plateau across 1957-2018. Atmosphere 2023, 14, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Han, J.; Zhang, L.; Ma, Q. Reinforcement and restoring methods of rotten lacquer waresunearthed in the dry area of north China. Sci. Conserv. Archaeol. 2003, 5, 31–34. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Z.; Wang, L. Current Status of Conservation Research on Unearthed Lacquerware Artifacts in China. Cult. Relics South China 2009, 1, 114–118. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, J.; Schilling, R.M. Reconstructing lacquer technology through Chinese classical texts. Stud. Conserv. 2016, 61, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Liu, C.; Zhou, Y.; Hu, D. pH-dependent warping behaviors of ancient lacquer films excavated in Shanxi, China. Herit. Sci. 2022, 10, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scovil, J. A mineral excursion to China: 2004. Rocks Miner. 2005, 80, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sáez-Hernández, R.; Cruz, J.; Alcalà-Bernàrdez, M.; Morales-Rubio, Á.; Luisa Cervera, M. An artificial intelligence-based semiquantitative method based on visible spectroscopy and imaging to analyse inorganic red pigments in wall paintings. J. Cult. Herit 2025, 75, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormack, J.K. The darkening of cinnabar in sunlight. Miner. Depos. 2000, 35, 796–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Wang, L.; Zhao, X.; Yang, J.; Zhang, M.; Wang, Y. Characterization of the materials and techniques of a birthday inscribed lacquer plaque of the qing dynasty. Herit. Sci. 2020, 8, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chenchen, Y.; Bo, R.; Jing, H.; Xutong, C.; Desheng, L.; Fengyi, H.; Shaojun, Y.; Ling, H.; Lingjie, M.; Junyan, L.; et al. An insight into the origin of elemental chromium in the lacquer of Qin terracotta warriors. Herit. Sci. 2024, 12, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Shan, W.; Zhang, W.; Guo, S. Infrared spectra of ancient lacquer objects. J. Fudan Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 1992, 3, 345–349. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Z.; Wang, Q.; Li, Z.; Sun, Y.; Lv, H.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, X. A study on the manufacturing process of a coiled wood core lacquerware unearthed in Xuzhou. npj Herit. Sci. 2025, 13, 472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Wang, L.; Zhao, X.; Xi, Z.; Wu, X.; Fan, X. Characterization of the Materials and Techniques of Red Lacquer Painting of a Horizontal Plaque Inscribed by General Feng Yü-hsiang. Coatings 2023, 13, 583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schilling, R.M.; Heginbotham, A.; van Keulen, H.; Szelewski, M. Beyond the basics: A systematic approach for comprehensive analysis of organic materials in Asian lacquers. Stud. Conserv. 2016, 61, 3–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Li, X.; Yu, J.; Sun, Y.; Geng, J.; Zhao, X. The Lacquer Craft of the Corridor Coffin (徼道棺) from Tomb No. 2 of Tushan in Eastern Han Dynasty, Xuzhou. Coatings 2024, 14, 1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.Y.; Lv, M.Q.; Liu, M.; Wu, Z.H.; Lv, J.F. Characterization and identification of lacquer films from the Qin and Han Dynasties. BioResources 2019, 14, 9509–9517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, P.J.; Hu, Y.L.; Ke, Z.B. Characterization of lacquer films from the middle and late Chinese warring states period 476–221BC. Microsc. Res. Tech. 2017, 80, 1344–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snellings, R.; Salze, A.; Scrivener, K.L. Use of X-ray diffraction to quantify amorphous supplementary cementitious materials in anhydrous and hydrated blended cements. Cem. Concr. Res. 2014, 64, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Nie, F.; Chen, J.M.; Zhu, Y. Studies on lacquerwares from between the mid-Warring States period and the mid-Western han dynasty excavated in the Changsha region. Archaeometry 2017, 59, 547–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Shi, Y.; Khanjian, H.; Schilling, M.; Li, M.; Fang, H.; Cui, D.; Kakoulli, I. Characterization of early imperial lacquerware from the luozhuang Han tomb, China. Archaeometry 2017, 59, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.C.; Cheng, P.; Li, T.T.; Yang, Y.; Tie, F.D.; Jin, P.J. Multispectral analysis on Lacquer films of boxes excavated from Haiqu Cemetery during the Han dynasties. Spectrosc. Spectr. Anal. 2022, 42, 1150–1155. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, R.; Nie, F.; Chen, J.M.; Li, Y.F. Studies on the Ground Layer of Lacquerwares from Between the Mid-Warring States Period and the Mid-Western Han Dynasty Unearthed in the Changsha Region. Archaeometry 2017, 59, 105–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Wang, L.; Zhao, X.; Qian, Y.; Tang, Y.; Dong, X. Synthesis, testing and application of moisture-curable polyurethane as a consolidant for fragile organic cultural objects. J. Adhes. Sci. Technol. 2018, 32, 2421–2428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, X.; Han, X.; Chen, K. Anti-Aging Performance Evaluation of Acrylate Emulsion Used for Cultural Relics Conservation. Spectrosc. Spectr. Anal. 2023, 43, 2181–2187. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, L.; Zhang, J.; He, T. A fish glue-reinforced filler for enhancing waterproof and adhesive properties of Ming-Qing lacquer furniture. npj Herit. Sci. 2025, 13, 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Zhang, P.; Ding, J.; Dong, Y.; Cao, Y.; Dong, W.; Zhao, X.; Li, X.; Camaiti, M. Nano Ca(OH)2: A review on synthesis, properties and applications. J. Cult. Herit. 2021, 50, 25–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langhals, H.; Bathelt, D. The restoration of the largest archaelogical discovery-a chemical problem: Conservation of the polychromy of the Chinese Terracotta Army in Lintong. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2003, 42, 5676–5681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; Yang, P. Conservation strategies and challenges for archaeological non-waterlogged lacquered wooden artifacts. J. Beijing Univ. Chem. Technol. (Nat. Sci.) 2025, 52, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.