Research on the Forming, Microstructures, and Mechanical Properties of High-Speed Laser Cladding 1Cr17Ni2 Stainless Steel on 1Cr17Ni5 Thin-Walled Tube

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussions

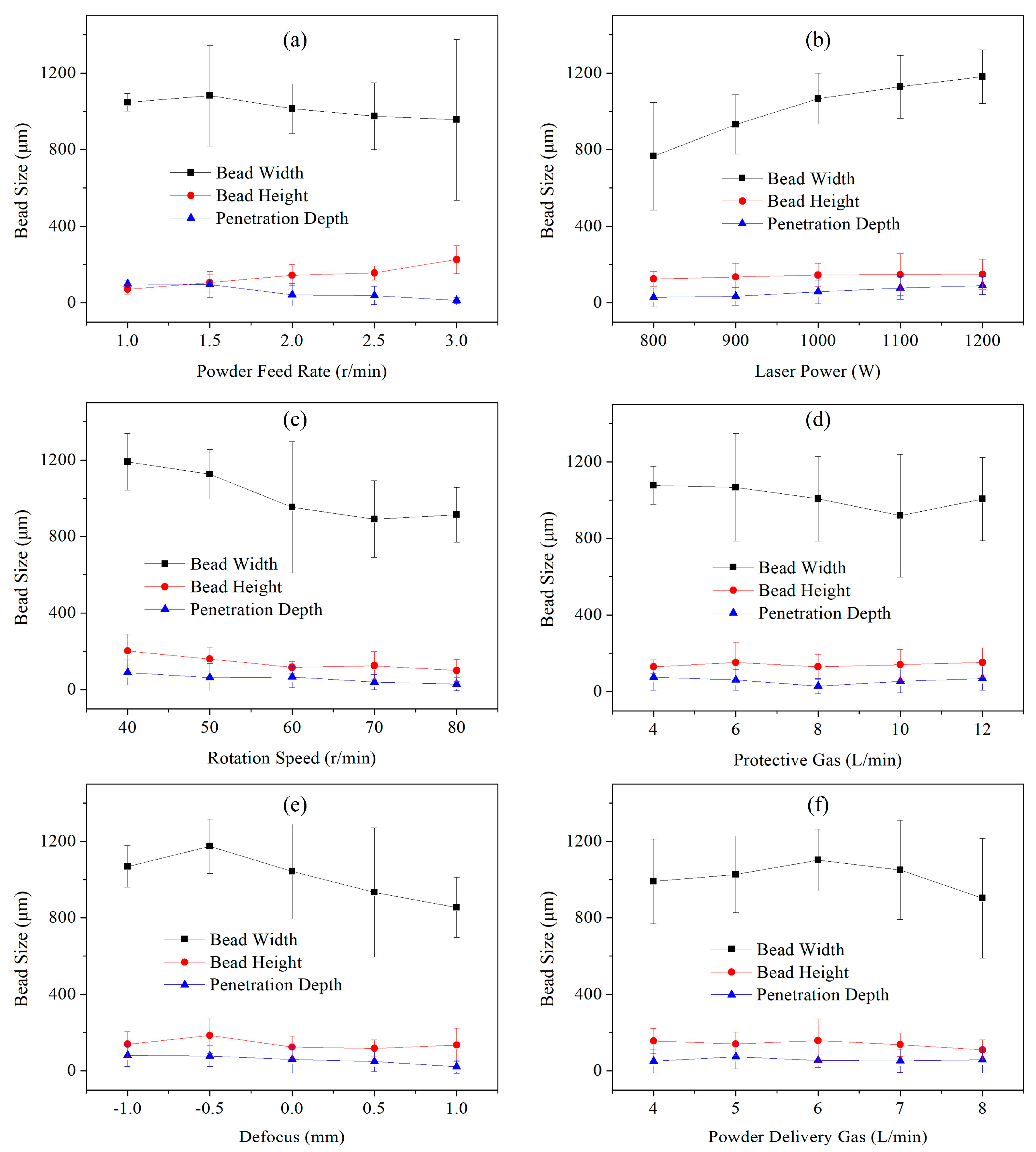

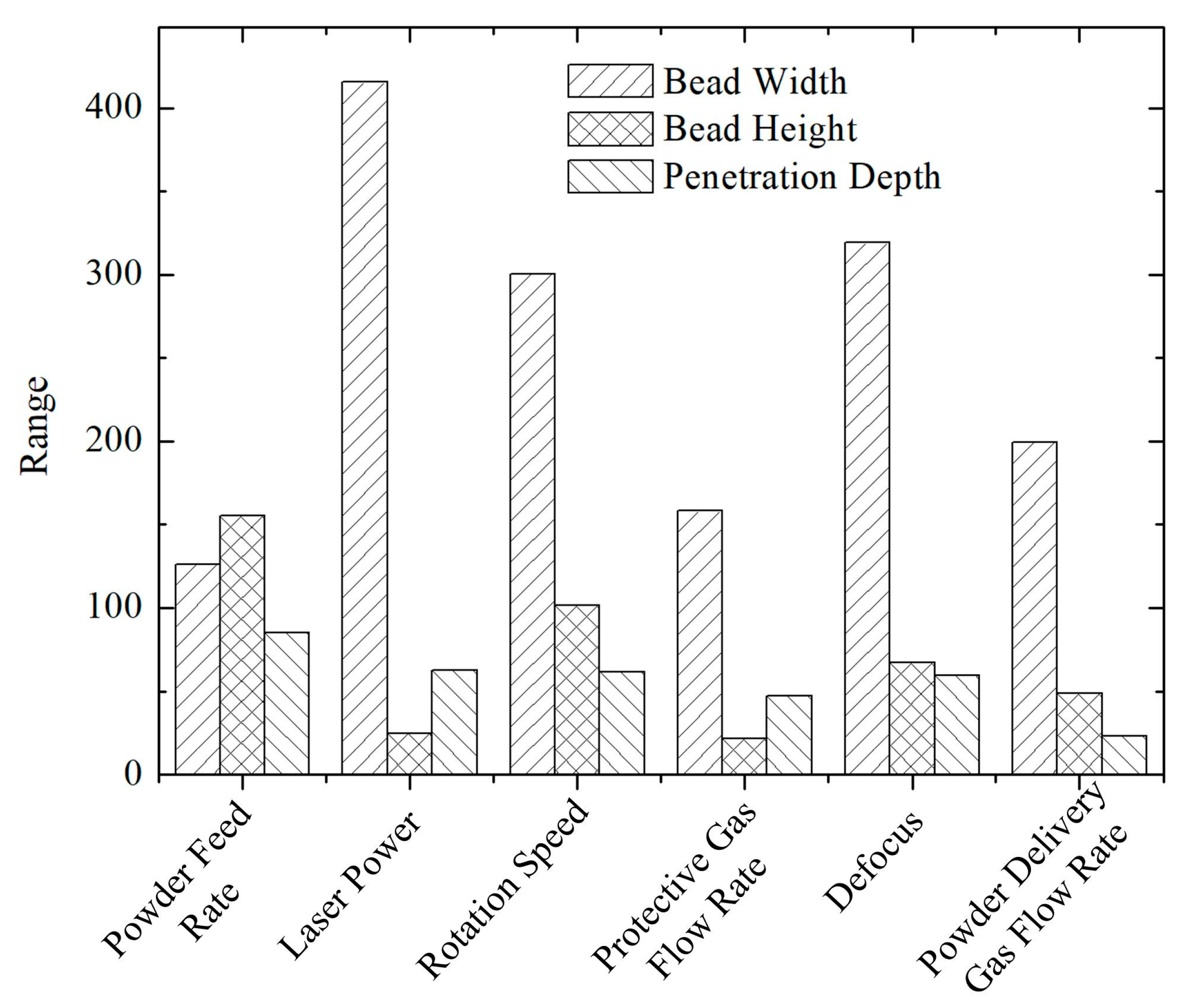

3.1. Forming of Single-Pass Beads

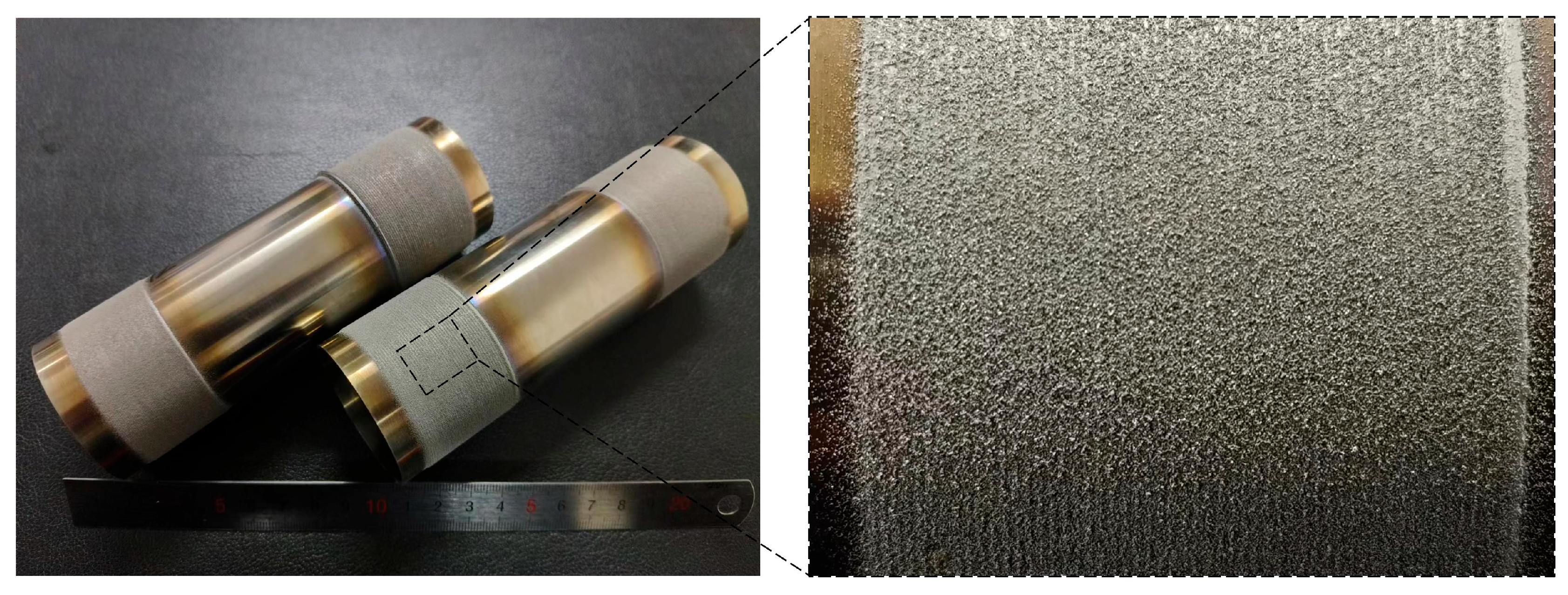

3.2. Multi-Pass Cladding Morphology and Deformation

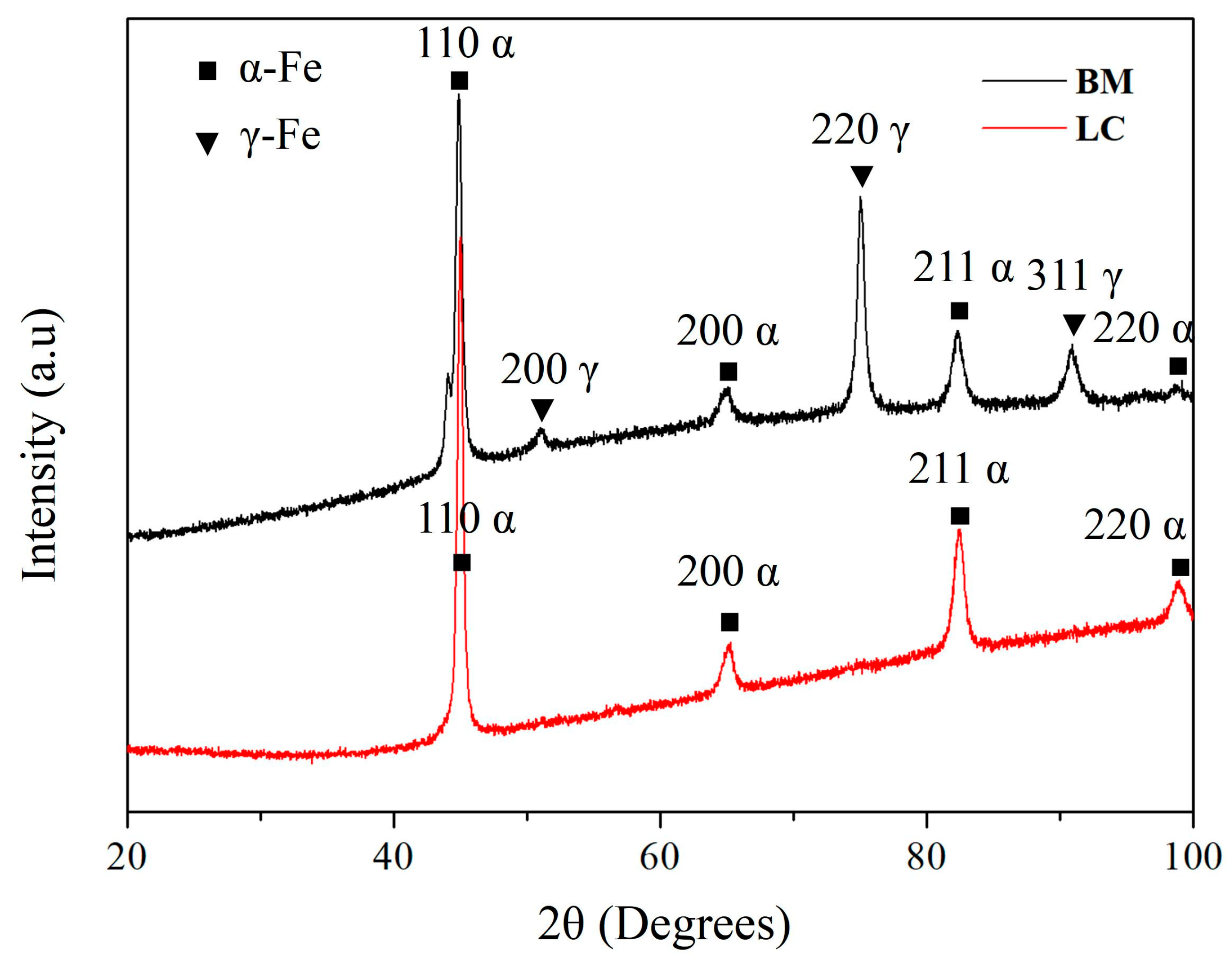

3.3. Microstructure and Phase Analysis

3.4. Microhardness Characteristics

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- Using high-speed laser cladding technology, excellent formation can be achieved on 1Cr17Ni5 tube with 1Cr17Ni2 powder. Orthogonal test results indicate that laser power has the most significant influence on the bead width, with an increase in laser power leading to a wider bead. The powder feed rate has the most significant effect on the bead height, resulting in a gradual increase in bead height with an increase in powder feed rate. Similarly, the powder feed rate has the most significant effect on the penetration depth, with an increase in powder feed rate leading to a gradual decrease in penetration depth.

- (2)

- In the multiple overlapping cladding layers, the microstructure exhibits a distinct periodic distribution, with a uniform distribution of elements both within and between layers. The cladding microstructure comprises α-Fe, numerous fine martensitic structures distributed within the columns grain. As the distance from the fusion line increases in the cladding layer, the size of the columnar crystals gradually decreases due to a reduction in cooling rate.

- (3)

- The substrate microstructure of the tube exhibits a distinct rolled state with flattened grains. After being thermally affected, the microstructure in the heat-affected zone transforms into equiaxed grains. The heat-affected zone undergoes only changes in grain morphology without phase transformation, primarily consisting of austenite.

- (4)

- The microhardness of the 1Cr17Ni2 cladding layer gradually decreases as the distance from the fusion line increases. The microhardness at the bottom is 562 HV, while the microhardness at the top is 532 HV. The substrate microhardness is 366 HV. However, due to the thermal influence of cladding, the microhardness in the heat-affected zone decreases to 239 HV. As the distance from the fusion line increases, the microhardness in the heat-affected zone gradually increases.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, X.; Wang, G.; Wang, W.; Liu, X.; Liu, Y.; Jin, Y.; Zhang, Y. Enhancing corrosion resistance of nickel-based alloys: A review of alloying, surface treatments, and environmental effects. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1032, 181014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, J.; Stöbener, D.; Stemmer, S.; Langenhorst, L.; Sölter, J.; Karpuschewski, B.; Fischer, A. Robot-assisted optical measurement method for the wear analysis of cutting tools. Wear 2026, 584–585, 206369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Hou, Z.; Babu, R.P.; Xu, X.; Liu, K.; Huang, X. Effect of surface nanocrystallization on microstructure, mechanical property and corrosion resistance of Mg and its alloys: A perspective review. J. Magnes. Alloys 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munteanu, C.; Melnic, I.; Istrate, B.; Hardiman, M.; Gaiginschi, L.; Lupu, F.C.; Arsenoaia, V.N.; Chicet, D.L.; Zirnescu, C.; Badiul, V.A. Comprehensive Review of Improving the Durability Properties of Agricultural Harrow Discs by Atmospheric Plasma Spraying (APS). Coatings 2025, 15, 632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Long, W.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, H. A review on ceramic coatings prepared by laser cladding technology. Opt. Laser Technol. 2024, 176, 110993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Xue, P.; Lan, Q.; Meng, G.; Ren, Y.; Yang, Z.; Xu, P.; Liu, Z. Recent research and development status of laser cladding: A review. Opt. Laser Technol. 2021, 138, 106915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Q.; Liu, K.; Li, J.; Geng, S.; Sun, L.; Skuratov, V. A review on cracking mechanism and suppression strategy of nickel-based superalloys during laser cladding. J. Alloys Compd. 2024, 1001, 175164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, K.; Zhong, C.; Zhang, L.; Wang, X.; Nie, B.; Xue, Y.; Gui, W.; Luan, B. Effect of multiple thermal cycling on the microstructure and microhardness of Inconel 625 by high-speed laser cladding. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 24, 1093–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, Y.; Liu, Y.; Qi, H.; He, P.; Huang, G.; Huang, Z. Effects of scanning speed on the microstructure, hardness and corrosion properties of high-speed laser cladding Fe-based stainless coatings. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 29, 3380–3392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schopphoven, T.; Gasser, A.; Wissenbach, K.; Poprawe, R. Investigations on ultra-high-speed laser material deposition as alternative for hard chrome plating and thermal spraying. J. Laser Appl. 2016, 28, 022501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schopphoven, T.; Gasser, A.; Backes, G. EHLA: Extreme High-Speed Laser Material Deposition: Economical and effective protection against corrosion and wear. Laser Tech. J. 2017, 14, 26–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Q.; Zhang, J.; Li, Q.; Wang, R.; Zhao, C. Microstructure and corrosion resistance of Fe-based coatings prepared using high-speed laser cladding and powerful spinning treatment. Mater. Lett. 2022, 310, 131429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Sun, Y.; Dong, P.; Yang, Q.; Ren, C.; Zhou, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Yang, X.; Li, C.; Wang, X.; et al. Rapid preparation of nanocrystalline high-entropy alloy coating with extremely low dilution rate and excellent corrosion resistance via ultra-high-speed laser cladding. Intermetallics 2024, 170, 108346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Liu, Y.; Hu, D.; Lv, H.; Yang, Q. Experimental and numerical simulation studies of the flow characteristics and temperature field of Fe-based powders in extreme high-speed laser cladding. Opt. Laser Technol. 2024, 170, 110317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Shen, F.; Zhou, Y.; Tao, W. Comparative study of stainless steel AISI 431 coatings prepared by extreme-high-speed and conventional laser cladding. J. Laser Appl. 2019, 31, 042009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Chang, S.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Shen, F.; Li, L. Effect of inhomogeneous composition on the passive film of AISI 431 coating fabricated by extreme-high-speed laser cladding. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2022, 440, 128496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Liu, Z.; Huang, F.; Dong, J.; Wang, C.; Yuan, J.; Fu, Q. Experimental study of corrosion resistance of 431M2 stainless steel coatings in a CO2-saturated NaCl solution deposited by extreme high-speed laser cladding. Mater. Today Commun. 2024, 38, 108202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, X.; Xu, X.; Lu, H.; Liang, Y.; Bian, H.; Luo, K.; Lu, J. Effect of overlap rate on the microstructure and properties of Cr-rich stainless steel coatings prepared by extreme high-speed laser cladding. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2024, 487, 131025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Du, J.L.; Luo, K.Y.; Peng, M.X.; Xing, F.; Wu, L.J.; Lu, J.Z. Microstructural features and corrosion behavior of Fe-based coatings prepared by an integrated process of extreme high-speed laser additive manufacturing. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2021, 422, 127500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Ren, X.; Xue, Y.; Luan, B. Investigation on microstructure and high-temperature wear properties of high-speed laser cladding Inconel 625 alloy. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 30, 626–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, F.; Wang, Z.; Xu, X.; Luo, K.; Lu, J. The effect of Y2O3 nanoparticle addition on the microstructure and high-temperature corrosion resistance of IN718 deposited by extreme high-speed laser cladding. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2024, 476, 130235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, A.; Cheng, X.; Zhang, S.Q.; Wang, H.M. Effects of heat treatment on microstructure and tensile properties of laser melting deposited AISI 431 martensitic stainless steel. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2016, 666, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Lan, X.; Yang, S.; Lu, J.; Yan, S.; Wei, K.; Wang, Z. Effect of quenching and tempering treatments on microstructure and mechanical properties of 300M ultra-high strength steel fabricated by laser powder bed fusion. Mater. Charact. 2024, 212, 113935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.Y.; Jian, Y.X.; Chen, Z.H.; Qi, H.J.; Huang, Z.F.; Huang, G.S.; Xing, J.D. Microstructure, hardness and slurry erosion-wear behaviors of high-speed laser cladding Stellite 6 coatings prepared by the inside-beam powder feeding method. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2022, 19, 2596–2610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, J.Y.; Yu, G.; He, X.L.; Li, S.X.; Chen, R.; Zhao, Y. Grain size evolution under different cooling rate in laser additive manufacturing of superalloy. Opt. Laser Technol. 2019, 119, 105662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.; Felicelli, S.D. Dendrite growth simulation during solidification in the LENS process. Acta Mater. 2010, 58, 1455–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.L.; Xu, X.; Zhang, H.M.; Lu, M.W.; Sun, J.F.; Luo, K.Y.; Lu, J.Z. Microstructure and wear resistance of CoCrFeNiMn coatings prepared byextreme-high-speed laser cladding. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2023, 470, 129821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Sheng, P.; Zeng, X. Comparative studies on the Ni60 coatings deposited by conventional and induction heating assisted extreme-high-speed laser cladding technology: Formability, microstructure and hardness. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2022, 16, 1732–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, C.; Hu, L.; Ren, X.; Li, Y.; Zhang, F.; Liu, P.; Li, Y. Cracking mechanism of brittle FeCoNiCrAl HEA coating using extreme high-speed laser cladding. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2021, 424, 127617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, P.; Wang, B.; Wang, L.; Hue, Y.; Zhou, L. Effect of welding heat input on grain boundary evolution and toughness properties in CGHAZ of X90 tubeline steel. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2018, 722, 112–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, L.; Qiu, C.; Zhao, D.; Gao, X.; Du, L. Microstructural characteristics and toughness of the simulated coarse grained heat affected zone of high strength low carbon bainitic steel. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2011, 529, 192–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Z.; Kim, M.-K.; Fang, Y.; Yuan, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Suhr, J. Investigation of laser-powder bed fusion driven controllable heterogeneous microstructure and its mechanical properties of martensitic stainless steel. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2024, 891, 145917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemmati, I.; Ocelík, V.; De Hosson, J.T.M. The effect of cladding speed on phase constitution and properties of AISI 431 stainless steel laser deposited coatings. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2011, 205, 5235–5239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Case No. | Powder Feed Rate/r·min−1 | Laser Power/W | Rotation Speed/r·min−1 | Linear Energy Density/J·mm−1 | Protective Gas/L·min−1 | Powder Defocus/mm | Powder Delivery Gas/L·min−1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 800 | 40 | 7.64 | 4 | −1 | 4 |

| 2 | 1 | 900 | 50 | 6.88 | 6 | −0.5 | 5 |

| 3 | 1 | 1000 | 60 | 6.37 | 8 | 0 | 6 |

| 4 | 1 | 1100 | 70 | 6.00 | 10 | 0.5 | 7 |

| 5 | 1 | 1200 | 80 | 5.73 | 12 | 1 | 8 |

| 6 | 1.5 | 800 | 70 | 4.37 | 8 | 1 | 5 |

| 7 | 1.5 | 900 | 80 | 4.3 | 10 | −1 | 6 |

| 8 | 1.5 | 1000 | 40 | 9.55 | 12 | −0.5 | 7 |

| 9 | 1.5 | 1100 | 50 | 8.40 | 4 | 0 | 8 |

| 10 | 1.5 | 1200 | 60 | 7.64 | 6 | 0.5 | 4 |

| 11 | 2 | 800 | 50 | 6.11 | 12 | −0.5 | 6 |

| 12 | 2 | 900 | 60 | 5.73 | 4 | 0 | 7 |

| 13 | 2 | 1000 | 70 | 5.46 | 6 | 0.5 | 8 |

| 14 | 2 | 1100 | 80 | 5.25 | 8 | 1 | 4 |

| 15 | 2 | 1200 | 40 | 11.46 | 10 | −1 | 5 |

| 16 | 2.5 | 800 | 80 | 3.82 | 6 | 0 | 7 |

| 17 | 2.5 | 900 | 40 | 8.59 | 8 | 0.5 | 8 |

| 18 | 2.5 | 1000 | 50 | 7.64 | 10 | 1 | 4 |

| 19 | 2.5 | 1100 | 60 | 7.00 | 12 | −1 | 5 |

| 20 | 2.5 | 1200 | 70 | 6.55 | 4 | −0.5 | 6 |

| 21 | 3 | 800 | 60 | 5.09 | 10 | 0.5 | 8 |

| 22 | 3 | 900 | 70 | 4.91 | 12 | 1 | 4 |

| 23 | 3 | 1000 | 80 | 4.77 | 4 | −1 | 5 |

| 24 | 3 | 1100 | 40 | 10.50 | 6 | −0.5 | 6 |

| 25 | 3 | 1200 | 50 | 9.17 | 8 | 0 | 7 |

| Case No. | Bead Width/μm | Bead Height/μm | Penetration Depth/μm |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1053.1 | 102.7 | 117.1 |

| 2 | 1084.5 | 88.2 | 113.7 |

| 3 | 1076 | 68.7 | 98.4 |

| 4 | 1051.4 | 59.4 | 80.6 |

| 5 | 969.1 | 35.6 | 83.1 |

| 6 | 691.6 | 79.8 | 8.5 |

| 7 | 929.2 | 57.7 | 39.9 |

| 8 | 1280.4 | 173.1 | 145.900 |

| 9 | 1217.7 | 100.1 | 164.6 |

| 10 | 1290.6 | 117.9 | 122.2 |

| 11 | 1030.2 | 176.5 | 13.6 |

| 12 | 946.2 | 117.1 | 11.9 |

| 13 | 922.5 | 94.2 | 29.7 |

| 14 | 939.4 | 110.3 | 11.0 |

| 15 | 1233.8 | 224.8 | 145.1 |

| 16 | 672.1 | 117.9 | 1.7 |

| 17 | 1022.5 | 170.5 | 6.8 |

| 18 | 996.2 | 210.4 | 6.8 |

| 19 | 1070.0 | 130.7 | 98.4 |

| 20 | 1109.9 | 150.2 | 81.4 |

| 21 | 380.3 | 148.5 | 1.1 |

| 22 | 676.4 | 241.8 | 0 |

| 23 | 1055.6 | 181.2 | 6.8 |

| 24 | 1364.5 | 338.5 | 36.5 |

| 25 | 1301.7 | 220.6 | 22.1 |

| Minimum Tube Diameter/mm | Maximum Tube Diameter/mm | Difference in Tube Diameter/mm | Ovality (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before laser cladding | 50.02 | 50.08 | 0.07 | 0.14 |

| After laser cladding | 49.99 | 50.11 | 0.12 | 0.24 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Li, S.; Zhang, L.-L.; Ci, S.-W.; Cai, X.-Y. Research on the Forming, Microstructures, and Mechanical Properties of High-Speed Laser Cladding 1Cr17Ni2 Stainless Steel on 1Cr17Ni5 Thin-Walled Tube. Coatings 2026, 16, 179. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16020179

Li S, Zhang L-L, Ci S-W, Cai X-Y. Research on the Forming, Microstructures, and Mechanical Properties of High-Speed Laser Cladding 1Cr17Ni2 Stainless Steel on 1Cr17Ni5 Thin-Walled Tube. Coatings. 2026; 16(2):179. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16020179

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Sen, Liang-Liang Zhang, Shi-Wei Ci, and Xiao-Ye Cai. 2026. "Research on the Forming, Microstructures, and Mechanical Properties of High-Speed Laser Cladding 1Cr17Ni2 Stainless Steel on 1Cr17Ni5 Thin-Walled Tube" Coatings 16, no. 2: 179. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16020179

APA StyleLi, S., Zhang, L.-L., Ci, S.-W., & Cai, X.-Y. (2026). Research on the Forming, Microstructures, and Mechanical Properties of High-Speed Laser Cladding 1Cr17Ni2 Stainless Steel on 1Cr17Ni5 Thin-Walled Tube. Coatings, 16(2), 179. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16020179