Abstract

Silica-rich dust intrusion is a persistent challenge for lubrication systems in agricultural machinery, where abrasive third-body particles can accelerate wear and shorten component service life. Here, molecular dynamics simulations are employed to elucidate how SiO2 nanoparticle contamination degrades polyalphaolefin (PAO) boundary lubrication at the atomic scale. Two confined sliding models are compared: a pure PAO film and a contaminated PAO film containing 7 wt% SiO2 nanoparticles between crystalline Fe substrates under a constant normal load and sliding velocity. The contaminated system exhibits a higher steady-state friction force, faster lubricant film disruption and migration, and consistently higher interfacial temperatures, indicating intensified energy dissipation. Substrate analyses reveal deeper and stronger von Mises stress penetration, increased severe plastic shear strain, elevated Fe potential energy associated with defect accumulation, and reduced structural order. Meanwhile, PAO molecules store more intramolecular deformation energy (bond, angle, and dihedral terms), reflecting stress concentration and disturbed shear alignment induced by nanoparticles. These results clarify the multi-pathway mechanisms by which abrasive SiO2 contaminants transform PAO from a protective boundary film into an agent promoting abrasive wear, providing insights for designing wear-resistant lubricants and improved filtration strategies for particle-laden applications.

1. Introduction

The operational reliability and service life of agricultural machinery are fundamentally dependent on the performance of their lubrication systems [1,2,3]. In contrast to controlled industrial settings, agricultural equipment continuously operates in harsh environments where soil dust, which is rich in abrasive silica particles, consistently infiltrates critical components such as gearboxes and hydraulic systems [3,4]. Such contamination can turn the lubricant from a protective film into a carrier of abrasive third-body particles, thereby accelerating wear, increasing energy consumption, and ultimately causing component failure A fundamental understanding of how these particulate contaminants degrade lubrication at the atomic scale is therefore essential for developing more durable lubrication solutions and predictive maintenance frameworks for agricultural applications.

Polyalphaolefin (PAO)-based lubricants are widely used in mechanical systems due to their excellent thermal stability and lubricating properties [5,6]. Under ideal conditions, PAO forms a protective boundary film that separates sliding metal surfaces, minimizing direct contact and wear. However, the introduction of hard, non-deformable particles such as silica disrupts this protective function. To date, several experimental studies have investigated how nanoparticle additives or contaminants influence the performance of PAO lubricants. Zawawi et al. [7] conducted a friction experimental study on PAO lubricant dispersed with SiO2 nanoparticles. Their work, focusing on thermo-physical and tribological properties, found that low-volume concentrations of SiO2 nanoparticles could enhance thermal conductivity, improve stability, and reduce the coefficient of friction and wear in a controlled setting. Fátima Mariño et al. [8] conducted experimental research to evaluate the tribological performance of PAO lubricant enhanced with stearic-acid-modified SiO2 (SiO2-SA) nanoparticles as additives. Their study systematically tested different concentrations under both pure sliding and rolling-sliding conditions at 120 °C, finding that nanolubricants significantly reduced friction and wear, with optimal anti-wear results observed at 0.20 wt% SiO2-SA. Ismail et al. [9] conducted an experimental study on the tribological performance of PAO-based hybrid nanolubricants containing SiO2 and TiO2 nanoparticles. The results showed that the 0.01% SiO2-TiO2/PAO nanolubricant exhibited good stability and achieved a COF reduction of up to 2.53%, while the 0.05% concentration did not show significant friction improvement. While classical theories and experimental research describe abrasive wear in terms of micro cutting and plowing, these macroscopic studies lack the resolution to reveal the initiating atomic scale events. Key questions remain unanswered at this scale.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation has emerged as a vital tool to bridge this gap, providing the necessary spatial and temporal resolution to investigate tribological phenomen. Prior MD studies have explored the behavior of lubricants, the effects of nano additives, and the shear response of confined fluids. Mathasa et al. [10] used MD simulation to evaluate the viscosity of a PAO base oil component under high pressure and temperature. The work compared equilibrium and nonequilibrium molecular dynamics approaches, examined how simulation parameters and force fields affect the results, and demonstrated agreement with experimental viscosity data. Wu et al. [11] used MD simulations to examine how graphene nanosheets change the rheological properties of PAO base oil. Results indicated that graphene addition greatly increases PAO viscosity, up to about 290 percent at 0.1 MPa and 500 K, and raises its boiling point above 800 K. Nevertheless, systematic atomic scale research focused on the tribological degradation caused by abrasive particulate contamination, particularly under conditions simulating agricultural environments, is still limited. Critical unknowns persist regarding how silica nanoparticles alter energy pathways within the tribosystem, how they distort the lubricant molecular structure and disrupt its flow, and how the resulting subsurface damage in the metal substrate manifests at the atomic level.

To address these questions, this study employs large scale MD simulations to conduct a controlled atomic scale tribology simulation. We construct two molecular dynamics models: a pure PAO system and a PAO system contaminated with SiO2 nanoparticles. By analyzing friction evolution, energy dissipation, stress–strain response, interfacial temperature, and substrate structural order, this work aims to quantify the impact of SiO2 contamination on friction and lubricant stability, decipher the atomic-scale energy and damage mechanisms in both the Fe substrate and PAO, and establish a direct link between particulate abrasion and multiscale tribological degradation. The findings are expected to provide fundamental insights into abrasive wear initiation in contaminated oils, offering a theoretical basis for designing wear-resistant lubricants and coatings for agricultural and other particle-laden environments.

2. Materials and Methods

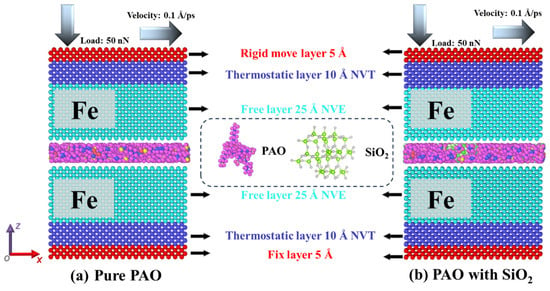

Figure 1 presents the initial atomic configurations used in this MD study. Two models were developed to examine the effect of particulate contaminants. The first model is a baseline system consisting of PAO lubricant confined between crystalline Fe substrates, as shown in the Figure 1a. The second model represents a contaminated system where silica nanoparticles make up 7 weight percent of the lubricant phase and are dispersed within the PAO matrix to simulate abrasive contamination, as shown in the Figure 1b. The simulation cell measures 60 Å by 60 Å in the periodic X and Y directions. This size allows sufficient sampling of interfacial behavior while reducing artifacts from periodic boundaries. The Z-direction is non-periodic to model a confined tribological interface. The Fe substrates are divided along the Z-axis into functionally distinct layers. These include two rigid boundary layers each 5 Å thick that act as load-bearing and sliding platens. Adjacent to these are thermostatted layers 10 Å thick maintained at 298.15 K using the NVT ensemble [12]. The central regions of the substrates are 25 Å thick dynamic layers where atoms move freely under the NVE ensemble. The space between the substrates forms the lubrication region filled with PAO molecules and in the contaminated model also with SiO2 [13]. The simulation protocol comprised sequential stages. Following energy minimization, a constant normal load of 50 nN was applied to the upper rigid layer for 50 ps to establish a stable confined state. Subsequently, a constant sliding velocity of 0.1 Å/ps was imposed on the same layer along the X-direction while maintaining the normal load, and After energy minimization, a normal load of 50 nN was applied for 50 ps to stabilize the confined state. Subsequently, a constant sliding velocity of 0.1 Å/ps was imposed along the x-direction while maintaining the normal load, and the sliding stage was simulated for 500 ps. Unless otherwise stated, all time stamps reported in the Results are measured from the onset of sliding.to capture the system’s tribological response.

Figure 1.

Schematic of the MD simulation models. Side views of the initial atomic configurations for (a) the pure PAO lubrication system and (b) the PAO system contaminated with SiO2 particles.

Interatomic interactions were modeled using a hybrid force-field framework. Fe-Fe interactions are described with an embedded atom method (EAM) potential [14]. Covalent bonding within SiO2 is represented by the Tersoff potential [15,16]. Interactions within and between PAO molecules are captured with the OPLS-AA all-atom force field [17,18,19]. Cross-interactions between different material types are handled using Lennard–Jones potentials with geometric mixing rules [20]. Long-range electrostatic forces are calculated with the particle–particle particle–mesh method [21].

All MD simulations were performed using the Large-scale Atomic/Molecular Massively Parallel Simulator (LAMMPS, version 19 Nov 2024) software package [22]. Post-processing analysis and visualization were carried out with the OVITO software [23].

3. Results and Discussion

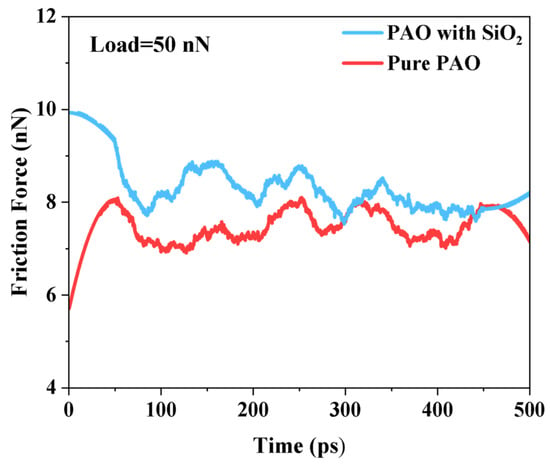

Figure 2 compares the evolution of the friction force over time for the two simulated tribological systems: the pure PAO lubricated system and the PAO system contaminated with SiO2 nanoparticles. A distinct contrast in frictional behavior is observed. In the pure PAO system, the friction force exhibits a gradual increase during the initial sliding stage, eventually reaching a stable plateau after approximately 100 ps. This behavior is characteristic of run-in processes where lubricant molecules undergo shear-induced alignment and rearrangement to form a stable boundary film. Conversely, in the contaminated system, the friction force starts at a significantly higher initial value and undergoes a marked decrease within the first 100 ps before stabilizing. This initial decrease likely corresponds to the abrasive wear-in phase, where protruding SiO2 nanoparticles are either crushed, sheared off, or embedded into the softer iron surfaces, leading to a temporary smoothing of the interface. Notably, after stabilization, the steady-state friction force in the contaminated system remains consistently higher than that in the pure system. This result directly demonstrates the detrimental impact of SiO2 particulates, which act as third-body abrasives [24], thereby increasing the overall shear resistance and energy dissipation at the sliding interface.

Figure 2.

Comparison of friction force evolution.

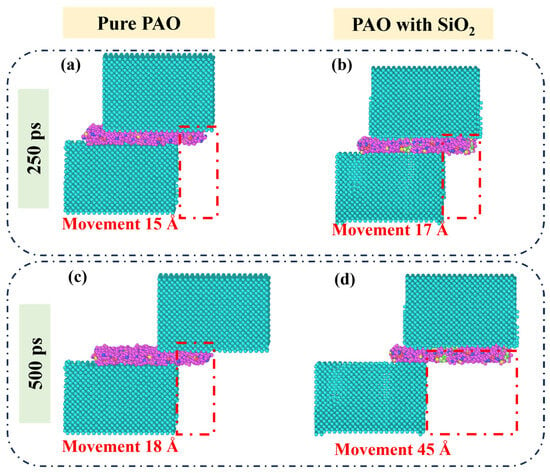

Figure 3 illustrates the progressive displacement of the polyalphaolefin lubricant layer along the sliding direction, providing direct visual evidence of the accelerated lubricant migration and film failure induced by silica contaminants. Displacement is quantified as the shift in the center of mass of the load bearing PAO domain, defined as the largest contiguous PAO cluster confined between the Fe substrates, along the sliding direction x relative to its initial position. In the contaminated system, embedded amorphous SiO2 inclusions act as a third body within the interfacial gap, promoting localized plowing and grooving of the Fe surfaces and facilitating interfacial microchannel formation. These abrasion generated defects create preferential percolation pathways and locally reduce confinement, thereby accelerating PAO expulsion from the central contact and enhancing lateral migration. Consequently, the substantially larger displacement observed at 500 ps under contamination is most consistently interpreted as evidence of boundary film destabilization and incipient breakdown of the load bearing lubricant layer, rather than beneficial lubricant transport. Figure 3a,b compares the lubricant configuration at 250 ps. In the pure PAO system, the lubricant layer has translated by approximately 15 Å, exhibiting a cohesive and relatively uniform flow. In contrast, the contaminated system shows a greater displacement of about 17 Å at the same time point, with the lubricant flow appearing more disordered. This early-stage difference suggests that the hard SiO2 particles, acting as third-body abrasives, disrupt the ordered shear of the lubricant film, leading to slightly enhanced but more erratic lubricant transport [25]. Figure 3c,d depict the state at 500 ps. The divergence becomes profoundly more significant. The displacement in the pure system reaches only about 18 Å, indicating that the lubricant film has stabilized and is undergoing steady, confined shear. Conversely, the displacement in the contaminated system dramatically increases to approximately 45 Å. This substantial, non-linear increase in lubricant migration signifies the catastrophic breakdown of the boundary lubricating film. The abrasive action of SiO2 particles likely creates deep grooves and defects in the iron substrates, facilitating the channeling and eventual large-scale displacement of the lubricant away from the central contact zone. This process directly correlates with the higher and more unstable friction observed in Figure 2.

Figure 3.

Snapshots comparing the PAO lubricant layer displacement in the pure and SiO2-contaminated systems at 250 ps and 500 ps after the onset of sliding. (a) Pure PAO system at 250 ps, (b) PAO with SiO2 at 250 ps, (c) Pure PAO system at 500 ps, (d) PAO with SiO2 at 500 ps.

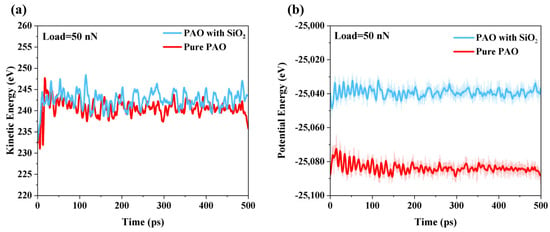

Figure 4 depicts the evolution of the kinetic and potential energy components of the Fe substrate during the friction process for both the pure and contaminated lubricating systems, providing a mechanistic view of energy dissipation at the atomic scale. Figure 4a shows the kinetic energy of the Fe substrate as a function of sliding time. The system contaminated with SiO2 nanoparticles maintains a higher average kinetic energy (approximately 243 eV) throughout the steady state compared to the pure PAO system (approximately 240 eV). This increase signifies more intense atomic vibrations and localized thermal agitation within the Fe substrate, a direct consequence of the continuous mechanical interaction and impact with the hard abrasive particles. Figure 4b presents the corresponding potential energy of the Fe substrate. A more substantial difference is evident: the potential energy for the pure system converges to around −25,080 eV, while it stabilizes at a markedly higher value of approximately −25,012 eV for the contaminated system. The elevation in potential energy (by about 68 eV) unambiguously indicates the accumulation of lattice defects, dislocations, and plastic deformation within the Fe substrate caused by the abrasive action of SiO2 particles. This raised internal strain energy represents the permanent microstructural damage inflicted by the contaminants. Together, these energy metrics quantitatively link the macroscopic frictional behavior (Figure 2) to microscopic energy pathways: the higher friction observed in the contaminated system is fundamentally driven by greater energy dissipation, which manifests as both increased atomic kinetic energy and, predominantly, as stored deformation energy within the worn substrate [26,27].

Figure 4.

Time evolution of Fe substrate: (a) kinetic energy and (b) potential energy during sliding (pure PAO vs. SiO2-contaminated PAO).

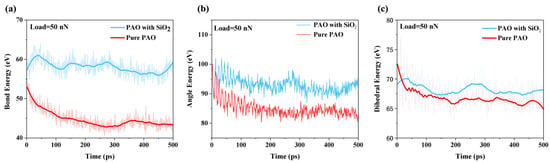

Figure 5 analyzes the intramolecular energy components of the PAO lubricant under shear, revealing how particulate contamination alters the molecular deformation and energy storage within the lubricant film. Figure 5a compares the average bond stretching energy. The PAO in the contaminated system exhibits a significantly higher bond energy (approximately 58 eV) compared to that in the pure system (approximately 42 eV). This 38% increase indicates that SiO2 particles induce severe local stress concentrations, forcing PAO molecular bonds to stretch beyond their equilibrium configurations more frequently and to a greater extent. Figure 5b presents the angle bending energy. The contaminated system also shows an elevated angle energy (approximately 93 eV) relative to the pure system (approximately 84 eV). This suggests that the presence of abrasive particles distorts the molecular backbone angles of PAO, impeding their natural flexibility and shear-induced alignment. Figure 5c details the dihedral torsion energy. A higher energy is again observed for the contaminated system (approximately 68 eV) versus the pure system (approximately 63 eV), implying that the rotational freedom of PAO chains is further restricted by interactions with or confinement near SiO2 particles. Collectively, the consistent increase across all intramolecular energy modes (bond, angle, and dihedral) in the contaminated system demonstrates that SiO2 nanoparticles mechanically perturb the lubricant layer.

Figure 5.

Time evolution of PAO intramolecular energy components under shear: (a) bond stretching, (b) angle bending, and (c) dihedral torsion, comparing pure PAO and SiO2-contaminated PAO systems.

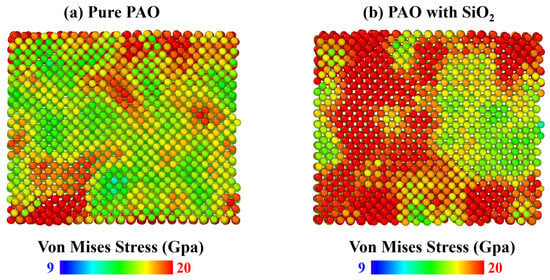

Figure 6 compares the von Mises stress distribution [28] within the iron substrates during steady-state sliding. In the pure PAO system (Figure 6a), stress concentrations are primarily confined to shallow surface regions, characteristic of controlled asperity contact. The introduction of SiO2 particles (Figure 6b) fundamentally alters this stress state: both the magnitude and spatial extent of the von Mises stress field increase substantially. This deeper, more intense stress penetration directly evidences severe subsurface plastic deformation, which is driven by the plowing action and mechanical impact of the hard abrasive particles [29]. The elevated stress fields correlate mechanistically with the observed increases in friction force (Figure 2) and PAO snapshots (Figure 3), collectively confirming that SiO2 contamination promotes abrasive wear and accelerates material damage at the atomic scale.

Figure 6.

Distribution of von Mises stress in iron substrates under sliding. (a) Pure PAO and (b) PAO with SiO2.

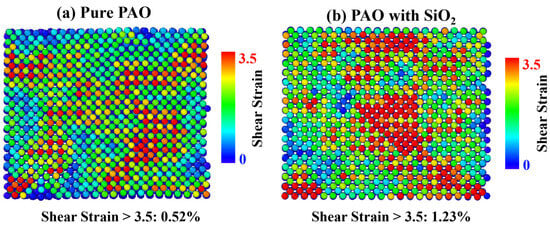

Figure 7 quantifies the extent of severe plastic deformation in the Fe substrates by analyzing the percentage of atoms exceeding a critical shear strain threshold of 3.5. In the pure PAO lubricated system (Figure 7a), only 0.52% of substrate atoms experience such extreme strain, confirming that deformation is relatively contained. In stark contrast, the system contaminated with SiO2 particles (Figure 7b) shows 1.23% of atoms exceeding this threshold, which is over twice the value observed in the pure system. This substantial rise in the volume of highly strained material provides direct statistical evidence that the abrasive action of SiO2 particles not only increases surface stress but also dramatically extends and intensifies irreversible plastic shear within the substrate. This result mechanistically links particulate contamination to accelerated wear and microstructural damage.

Figure 7.

Shear strain distribution in iron substrates after sliding. (a) Pure PAO and (b) PAO with SiO2.

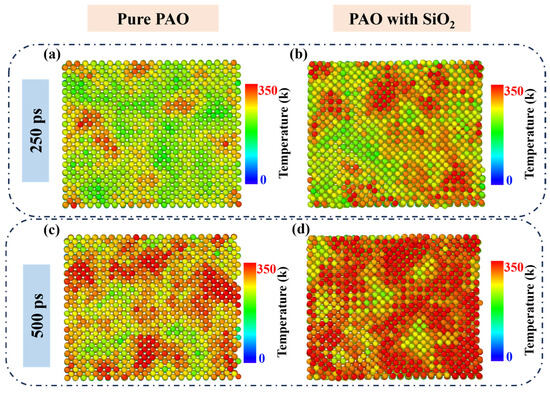

Figure 8 presents the interfacial temperature distribution at two distinct stages of sliding: 250 ps and 500 ps. A clear comparative trend is observed throughout the friction process. At 250 ps, the temperature in the pure PAO system (Figure 8a) is notably lower than that in the SiO2-contaminated system (Figure 8b). This temperature difference becomes even more pronounced by 500 ps, as shown in Figure 8c,d. The persistent elevation in interfacial temperature in the contaminated system directly evidences the intensified energy dissipation associated with abrasive wear mechanisms. The hard SiO2 particles act as additional heat sources through mechanisms such as plowing, micro-cutting, and repeated impact with the iron substrate, thereby converting a greater proportion of mechanical work into thermal energy compared to the pure lubricant system.

Figure 8.

Interfacial temperature distribution during sliding at 250 ps and 500 ps after the onset of sliding. (a) Pure PAO system at 250 ps; (b) PAO with SiO2 system at 250 ps; (c) Pure PAO system at 500 ps; (d) PAO with SiO2 system at 500 ps.

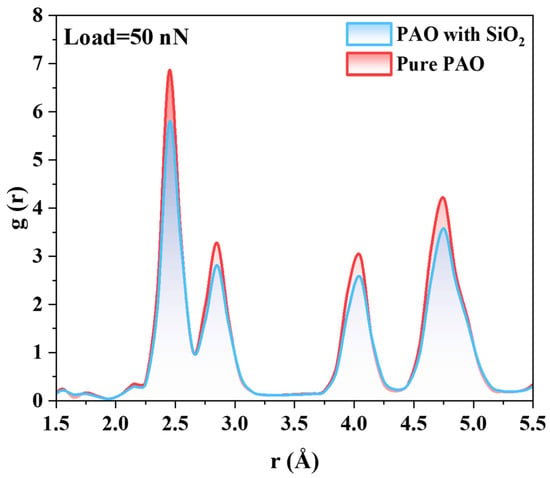

Figure 9 presents the radial distribution functions (RDF) for Fe-Fe pairs in the subsurface region of the iron substrates after the friction process [30]. A distinct difference in peak intensity is observed between the two systems. The pure PAO lubricated system exhibits relatively high and sharp RDF peaks at characteristic nearest-neighbor distances, indicating that the crystalline order of the iron lattice is largely preserved despite the sliding contact. In contrast, the system contaminated with SiO2 particles shows significantly reduced and broadened RDF peaks. The reduced and broadened Fe–Fe RDF peaks in the subsurface region indicate increased local structural disorder and defect accumulation induced by sliding, which weakens the periodic ordering compared with the less-damaged pure-PAO case. and increased atomic disorder within the iron near-surface region. The result is attributed to the abrasive action of the hard SiO2 particles, which plow through the surface, generating extensive plastic deformation, dislocations, and a substantially amorphized subsurface layer. This structural analysis at the atomic scale provides direct evidence for the abrasive wear mechanism and corroborates the higher levels of shear strain (Figure 7) and von Mises stress (Figure 6) measured in the contaminated system.

Figure 9.

Radial distribution function g(r) of Fe–Fe pairs in the subsurface region.

4. Conclusions

This MD simulation study systematically elucidates the detrimental effects of silica nanoparticle contamination on the boundary lubrication performance of polyalphaolefin between iron surfaces. The key conclusions are as follows:

- (1)

- The presence of SiO2 nanoparticles leads to a significant increase in steady-state friction force and causes catastrophic breakdown of the PAO lubricant film, evidenced by non-linear, large-scale lubricant displacement over time.

- (2)

- Contamination alters fundamental energy pathways. The iron substrate in the contaminated system stores more potential energy (increased by ~68 eV) due to accumulated lattice strain and damage, and exhibits higher kinetic energy (~243 Ev vs. ~240 eV), indicating intensified atomic vibrations. Concurrently, PAO molecules experience severe intramolecular strain, with bond, angle, and dihedral energies increasing by approximately 38%, 11%, and 8%, respectively, reflecting molecular-level confinement and distortion.

- (3)

- SiO2 particles induce profound subsurface damage. The von Mises stress field becomes more intense and penetrates deeper, while the volume of material undergoing severe plastic shear (strain > 3.5) more than doubles. This mechanical damage is corroborated by a severe loss of crystalline order in the iron near-surface region, as indicated by attenuated radial distribution function peaks.

- (4)

- The abrasive action of particles converts mechanical work into heat more efficiently, resulting in consistently higher interfacial temperatures in the contaminated system throughout the sliding process.

- (5)

- These atomic-scale insights clarify how silica dust contamination transforms PAO from a protective boundary film into a medium that promotes abrasive wear, underscoring the importance of contamination control and filtration in particle-laden applications such as agricultural machinery.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.J. and G.W.; methodology, G.W.; software, G.H.; validation, Y.Z., J.L. and C.P.; formal analysis, G.H.; investigation, G.W.; resources, X.J.; data curation, Y.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, X.J., G.H. and G.W.; writing—review and editing, X.J., G.W.; supervision, C.P.; project administration, C.P.; funding acquisition, X.J. and G.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number 52505192, Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province, grant number BK20250710, Wuxi Soft Science Research Project, grant number KX-25-B30, Natural Science Research Project of Wuxi Institute of Technology, grant number ZK2023010 and Jiangsu Qinglan Project.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Wang, Y.; Li, D.; Nie, C.; Gong, P.; Yang, J.; Hu, Z.; Li, B.; Ma, M. Research progress on the wear resistance of key components in agricultural machinery. Materials 2023, 16, 7646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, D.; Satapathy, S. Reliability and maintenance of agricultural machinery by MCDM approach. Int. J. Syst. Assur. Eng. Manag. 2023, 14, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Tang, Z.; Gu, X.; Zhang, B. Understanding the Lubrication and Wear Behavior of Agricultural Components Under Rice Interaction: A Multi-Scale Modeling Study. Lubricants 2025, 13, 388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fartash Naeimi, E.; Selvi, K.Ç.; Ungureanu, N. Exploring the Role of Advanced Composites and Biocomposites in Agricultural Machinery and Equipment: Insights into Design, Performance, and Sustainability. Polymers 2025, 17, 1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biresaw, G. Biobased polyalphaolefin base oil: Chemical, physical, and tribological properties. TriL 2018, 66, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolatabadi, N.; Rahmani, R.; Rahnejat, H.; Garner, C.P.; Brunton, C. Performance of poly alpha olefin nanolubricant. Lubricants 2020, 8, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zawawi, N.N.M.; Azmi, W.H.; Aminullah, A.R.M.; Ali, H.M. Polyalphaolefin-based SiO2 nanolubricants: Thermo-physical and tribology investigations for electric vehicle air-conditioning system. Int. J. Refrig. 2025, 178, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariño, F.; Liñeira del Río, J.M.; Gonçalves, D.E.P.; Seabra, J.H.O.; López, E.R.; Fernández, J. Effect of the addition of coated SiO2 nanoparticles on the tribological behavior of a low-viscosity polyalphaolefin base oil. Wear 2023, 530–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, R.N.R.; Azmi, W.H.; Zawawi, N.N.M. A Tribological Analysis of PAO-Based Hybrid SiO2-TiO2 Nanolubricants, 1st ed.; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2024; p. 012020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathas, D.; Holweger, W.; Wolf, M.; Bohnert, C.; Bakolas, V.; Procelewska, J.; Wang, L.; Bair, S.; Skylaris, C.-K. Evaluation of methods for viscosity simulations of lubricants at different temperatures and pressures: A case study on PAO-2. Tribol Trans. 2021, 64, 1138–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Keer, L.M.; Lu, J.; Song, B.; Gu, L. Molecular dynamics simulations of the rheological properties of graphene–PAO nanofluids. JMatS 2018, 53, 15969–15976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, A.J.; Isomoto, T.; Knaup, J.M.; Irle, S.; Morokuma, K. Effects of molecular dynamics thermostats on descriptions of chemical nonequilibrium. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2012, 8, 4019–4028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Sierra, M.T.; Báez, J.E.; Aguilera-Camacho, L.D.; García-Miranda, J.S.; Moreno, K.J.J.L. Evaluation of Aromatic Organic Compounds as Additives on the Lubrication Properties of Castor Oil. Lubricants 2024, 12, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grochola, G.; Russo, S.P.; Snook, I.K. On fitting a gold embedded atom method potential using the force matching method. J. Chem. Phys. 2005, 123, 204719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munetoh, S.; Motooka, T.; Moriguchi, K.; Shintani, A. Interatomic potential for Si–O systems using Tersoff parameterization. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2007, 39, 334–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, S.K.D. Study of the effect of sizes on the structural properties of SiO2 glass by molecular dynamics simulations. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2013, 376, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, A.; Parashar, A. Effect of the degree of polymerization, crystallinity and sulfonation on the thermal behaviour of PEEK: A molecular dynamics-based study. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2024, 26, 23335–23347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kashmari, K.; Patil, S.; Deshpande, P.; Shah, S.; Maiaru, M.; Odegard, G.M. Molecular Modeling of PEEK Resins for Prediction of Properties in Process Modeling. In Earth and Space 2021; American Society of Civil Engineers: Reston, Virginia, 2021; pp. 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broadbent, R.J.; Spencer, J.S.; Mostofi, A.A.; Sutton, A.P. Accelerated simulations of aromatic polymers: Application to polyether ether ketone (PEEK). Mol. Phys. 2014, 112, 2672–2680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, D.; Li, J.; Voon, L.C.; Wei, P. Determination of Lennard-Jones potential parameters for interfacial interaction in elemental layered crystals. J. Appl. Phys. 2024, 135, 204301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Chen, O.; Cheng, Q.; Yin, T.; Ren, K.; Ma, C.; Zhao, G.; Wang, G. Interfacial ice layer mediates anti-wear of PEEK during cryogenic sliding: An atomic-scale insight. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2026, 724, 165685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giles, R. Parallel Algorithms for Short-Range Molecular Dynamics. World Sci. Annu. Rev. Comput. Phys. 1995, 3, 119–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stukowski, A. Visualization and analysis of atomistic simulation data with OVITO–the Open Visualization Tool. Model. Simul. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2009, 18, 015012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, S.-C.; Pek, S.-S. Third-body and dissipation energy in green tribology film. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 3787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Bai, M.; Lv, J.; Kou, Z.; Li, X. Molecular dynamics simulation on the tribology properties of two hard nanoparticles (diamond and silicon dioxide) confined by two iron blocks. Tribol. Int. 2015, 90, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.Y.; Salmeron, M. Fundamental aspects of energy dissipation in friction. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 677–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singer, I.L. Friction and energy dissipation at the atomic scale: A review. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A Vac. Surf. Film. 1994, 12, 2605–2616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, A.; Dao, M.; Suresh, S. Steady-state frictional sliding contact on surfaces of plastically graded materials. Acta Mater. 2009, 57, 511–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, X.; Huang, G.; Chen, O.; Cheng, Q.; Peng, C.; Wang, G. Load and Velocity Dependence of Friction at Iron–Silica Interfaces: An Atomic-Scale Study. Coatings 2025, 15, 1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Chen, X.; Zhang, T.; Hang, J.; Tao, D. Estimation of Activity and Molar Excess Gibbs Energy of Binary Liquid Alloys Al-Cu, Al-Ni, and Al-Fe from the Partial Radial Distribution Function Simulated by Ab Initio Molecular Dynamics. Metals 2023, 13, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.