Abstract

A vacuum-arc pulsed plasma accelerator (APPA) operating at a discharge current of 750 A and a pulse duration of 110 μs with a repetition rate of 5 Hz was employed to deposit thin films and coatings under low- and medium-vacuum conditions. The aim of this study was to obtain metal coatings suitable for potential applications in the energy and chemical industries. SEM, AFM, and XRD techniques were used to investigate the structure and morphology of coatings formed on metallic and insulating substrates under the following conditions: residual pressure of 10−2–10−4 mbar and deposition times of 10–30 min. Under medium-vacuum conditions, thin and non-uniform metallic films with thicknesses ranging from 0.4 to 1.9 μm were deposited on metal substrates. The morphology of thick films deposited under low-vacuum conditions consisted of spherical metal particles of various sizes (0.1–1 μm), containing up to 30% carbon and 28% oxygen. On silicon substrates, spherical microparticles up to 4 μm in diameter with thin shells approximately 0.3 μm thick were formed. One possible mechanism for microsphere formation—the desorption of residual gases by the coating material—is discussed. The potential of the APPA method for producing metal shells, relevant to powder manufacturing due to the high energy density of the process and the intrinsic purity of vacuum technologies, is also considered. Porous coatings obtained using the APPA technique may be applicable in the fabrication of energy-related materials, such as battery anodes.

1. Introduction

In recent years, considerable attention has been devoted to promising research in vacuum-based physical and chemical technologies, both for the synthesis of nanomaterials and for the deposition of metal coatings. Materials such as porous coatings, metal powders, and metallic microspheres are widely used in energy generation, chemical processing, and industrial applications [1,2,3]. Among plasma-based vacuum deposition techniques, arc plasma vacuum deposition (APVD) is distinguished by its high productivity [4,5]. In this work, the primary objective is to investigate the morphology and structure of coatings deposited from arc plasma with the aim of developing new materials for energy-related applications.

It is well known that, in a vacuum arc, nearly the entire discharge current is concentrated on the cathode within microscopic (~10 μm) cathode spots, each lasting approximately 10−7 s. Similar physical processes are expected to occur in the plasma of a pulsed vacuum arc if the interval between successive triggering pulses exceeds this duration by at least an order of magnitude, which is readily achievable. The relatively low arc burning voltage (20–50 V) and the high plasma density represent important advantages for the development of technologies based on this process [4,5].

A review of work on arc sources shows that several plasma-flow features raise questions regarding their applicability in coating technologies. Two key aspects are of particular interest:

- Numerous researchers have observed anomalous high-velocity ions directed toward the anode, contradicting classical plasma theory, in which positive ions should move toward the cathode [6,7].

- The plasma flow almost always contains droplets of cathode material when the cathode is metallic. Methods for suppressing droplet formation exist but are technically complex [8,9,10].

Regarding the first issue, the energies of some high-velocity ions directed toward the substrate reach 100–150 eV, which is sufficient for coating deposition. However, the resulting coating structure under such energetic particle bombardment remains insufficiently understood; therefore, the reader is referred to reviews [11,12,13], which present different viewpoints. Regarding the second issue, metallic droplets (typically 1–10 μm) are generally undesirable due to the structural inhomogeneities they create. Nonetheless, in some cases, such microparticles may be beneficial, for example, in the production of metal powders. When deposited in sufficient quantity, they can form porous coatings. We assume that the generation of microparticles from the cathode increases significantly when the discharge current consists of strong pulses rather than steady direct current. For this reason, a new setup based on a pulsed vacuum arc was developed.

The power of a stationary arc typically ranges from several kilowatts to hundreds of kilowatts [7,14]. In contrast, a pulsed arc is characterized by a low average power of about 1 kW, which is a significant advantage for PVD processes using pulsed arc plasma [8,9]. Besides the energy parameters, key factors determining the behavior of a pulsed arc discharge include plasma composition, temperature, and the presence or absence of magnetic and electric fields [10,11,12].

In general, arc plasma consists of ionic and particulate (“dust”) components, as well as radiation. When sputtering multicomponent cathodes, nonequilibrium plasma compositions may form, leading to a redistribution of species both in the plasma and within the deposited coating.

One of the pressing challenges in industry is the development of coating materials used as catalysts in electrochemistry, as well as in filters, sorbents, and related applications. Coatings containing hollow microspheres and porous structures are of particular scientific and practical interest. Various physical and chemical methods exist for producing porous coatings. Chemical methods typically require imported precursors and allow the synthesis of multicomponent compounds such as metal oxides. Physical methods—including welding-wire techniques and high-temperature coating deposition—represent a separate category of porous-material production. High-temperature methods rely on a hot gas environment to atomize metal powders and subsequently deposit particles of controlled size and morphology.

The use of porous electrodes is highly relevant in various energy technologies, including fuel cells and metal–air batteries [13,14,15,16,17,18,19]. Metal-air batteries have been extensively studied as next-generation high-energy-density storage systems. However, metal electrodes in such batteries face numerous challenges, including dendrite formation, electrode shape instability, corrosion, side reactions, and surface passivation [20]. Currently, zinc, aluminum, and iron anodes are receiving active attention. Nonetheless, several scientific and technological obstacles continue to hinder the widespread adoption and advancement of metal–air batteries [21,22,23,24,25].

One of the most effective approaches to improving anode performance is increasing their specific surface area. A larger effective contact area between the electrode and electrolyte increases the number of reactive sites, thereby reducing the local current density. Additionally, porous materials inherently possess lower density, allowing electrodes of the same geometry to be made lighter.

2. Materials and Methods

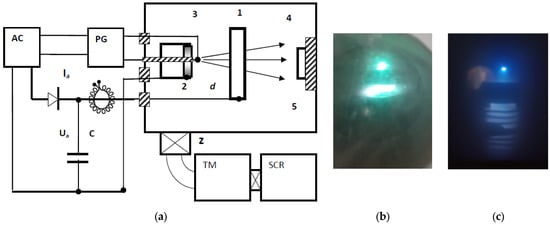

The basic schematic of the pulsed plasma accelerator is shown in Figure 1a. Inside the vacuum chamber (5), two coaxially positioned cylindrical electrodes—the anode (1) and the cathode (2)—are placed at a separation distance of d = 3–6 cm. When a constant voltage is applied across the electrodes, electrical breakdown does not occur because vacuum serves as an excellent insulator. Once the discharge is initiated by a high-voltage triggering pulse, plasma is first generated through spark breakdown between the cathode and the ignition electrode (3). The plasma then expands from the cathode surface toward the hollow anode and is subsequently directed onto the substrate (4). The substrate is mounted on a ceramic holder or can be electrically grounded.

Figure 1.

Schematic of the pulsed arc plasma accelerator (a). Emission pattern of the discharge between the anode and Cu cathode (b) and Ti cathode (c). TM and SCR denote the turbomolecular and screw pumps, respectively.

A high-voltage ignition pulse of approximately 20 kV and 300 ns duration is supplied from the secondary winding of the pulse transformer. A 60 μF, 500 V capacitor is discharged into the primary winding of the transformer through a thyristor. The pulse generator operated at a repetition rate of 5 Hz. A 220 V, 40 A AC autotransformer was used to supply power to the anode. A constant voltage U of 100–300 V was applied to the anode (+)–cathode (–) gap using a half-wave rectifier.

The discharge capacitor C consisted of a bank of IM-100 pulse capacitors, each with a capacitance of 100 μF; a total capacitance of 400 μF was used in the majority of experiments.

The vacuum chamber, with internal dimensions of 60 × 60 × 90 cm3, is equipped with a high-vacuum gate (Z) with a diameter of 200 mm. A turbomolecular (TM) pump and a screw (SCR) pump were used in series to evacuate the chamber. During the experiments, the minimum pressure achieved in the chamber was p2 = (2–4) × 10−4 mbar, and this value changed only slightly during operation. To increase the working pressure to approximately p1 ~ 10−2 mbar or higher, the gate valve was closed and atmospheric air was allowed to enter the chamber for several minutes. No buffer gas was introduced. It should be noted that the maximum residual pressure was typically reached within 30 min and varied only slightly upon ignition of the discharge. The anode was not actively cooled, while the cathode and the substrates were cooled with running water.

The cathode was assembled from segments of technical-grade copper (97.7%), duralumin (90.9%), and titanium (99.1%), as well as a standalone cathode made of high-purity aluminum (99.9%). Aluminum was of particular interest as a potential material for producing porous electrodes. Copper was included primarily to visualize the deposited coatings owing to its distinct color. The significant difference in atomic masses between Cu (63 amu) and Al (27 amu) is also useful for interpreting sputtering and plasma transport processes. All cathodes had a diameter of 50 mm and a height of 6 mm. A central axial hole was machined into each cathode for mounting the ignition electrode (3), which is convenient when the cathode assembly includes several materials. The anode was manufactured from a steel tube with a diameter of 11 cm.

Substrates for deposition included copper, duralumin, and AISI 201 stainless steel plates with dimensions of 20 × 20 × 1 mm3. A (111)-oriented silicon monocrystal substrate was also used, with deposition performed on its backside. Deposition times ranged from 10 to 30 min.

Surface topography was examined using a DM6000 optical microscope (OM) and a Quanta 3D 200i scanning electron microscope. The microscope’s microanalysis system was equipped with an energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDAX) module with an energy resolution of 132 eV (Mn Kα). The SEM operated at accelerating voltages from 200 V to 30 kV, providing a spatial resolution of 2.5 nm in high-vacuum mode. Sample topography was also analyzed with a QUANTA-200i system. Although referred to as an AFM in earlier documentation, this instrument is in fact an SEM combined with a focused ion beam (FIB), capable of high-resolution imaging, precision micromachining, and 3D surface analysis. It provides imaging resolutions of 3 nm at 30 kV in HV/ESEM mode and 12 nm at 3 kV in low-vacuum mode.

The experimental results were obtained from a series of more than 50 experiments conducted over the past three years. Overall, the trends observed in surface morphology were consistent across variations in discharge voltage (60–1800 V), capacitor capacitance (100–2000 μF), and chamber pressure (100 to 10−5 Torr). Measurement uncertainties were negligible for all parameters except film thickness, which depends on substrate quality. In the standard procedure, substrates underwent only mechanical grinding and polishing without chemical treatment.

3. Results

Before discussing the experimental results on coating deposition, it is essential to understand the operating principles of the device, as this directly influences the interpretation of the data and the conclusions drawn. A brief overview of the accelerator’s operation is provided in Section 3.1.

3.1. Testing of Device Operation

Operation in pulsed mode is possible over a wide range of vacuum levels, from 10−1 to 10−4 mbar pressure. At relatively low pressures (10−1–10−2 mbar), various forms of glow discharge were observed between the cathode, the anode, and the chamber walls. A pinkish nitrogen glow filled the entire chamber. The behavior of the system at high vacuum was of particular interest. When the pressure reached 10−4 mbar, the discharge became concentrated into an expanding beam directed from the cathode to the anode. The beam exhibited a greenish color for the copper cathode (Figure 1b), a white glow for the aluminum cathode, and a blue glow for the titanium cathode (Figure 1c). Beyond the anode, a slightly divergent plasma beam was formed and subsequently captured by the magnetic field.

Thus, both the geometry and coloration of the emission region indicate the formation of a directional flow of metallic plasma under high-vacuum conditions.

A detailed study of the characteristics of the anode pulse current, substrate pulse current, and signals from the time-of-flight sensors (two electrical probes) revealed that the processes occurring within the unit are complex and interrelated. The discharge current of the power battery (anode pulse current) and the pulse current from substrate 4 to chamber wall 5 (not shown in Figure 1) were measured using two identical Rogowski coils with a transformation coefficient of 300. The mean current was determined from oscilloscope traces as the measured voltage multiplied by 200.

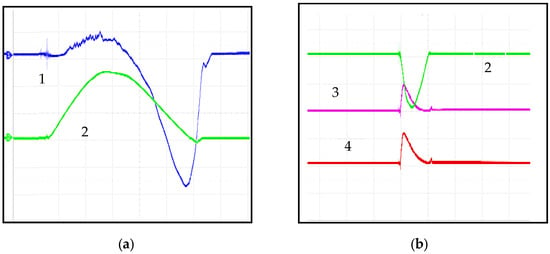

As observed in the experimental traces presented in Figure 2, the average anode pulse duration was 110 μs, with an amplitude of 750 A at an anode DC voltage of 150 V (Figure 2a). Two peaks were identified in the substrate current: the amplitude of the positive peak was independent of voltage, reaching a maximum of 90 A, while the negative peak was proportional to the anode voltage, reaching a maximum of 1200 A (signal 1 in Figure 2a). Figure 2b shows signals 3 and 4 from electrical probes positioned 10 cm apart along the plasma flow path (transient-time sensors). It is evident that the unit generates a high-velocity flow that occurs almost simultaneously with the onset of the discharge current. At this point, the flow velocity clearly exceeds 5 × 104 m/s (the smallest time division on the oscilloscope screen corresponds to 2 μs).

Figure 2.

Oscilloscope traces obtained in single-pulse mode: (a) 1—current to the substrate (500 mV/div, 20 µs/div); 2—current to the anode (1 V/div). (b); 2—anode current (1 V/div); 3, 4—signals from two electrical probes positioned along the plasma flow path (20 µs/div).

A detailed discussion of the physical processes occurring in the unit and its electrical characteristics is beyond the scope of this paper. However, it should be noted that the unit exhibits characteristics of both arc accelerators and pulsed plasma accelerators. In particular, the anode current oscillogram shows no plateau typical of an arc discharge, which is a feature of ablative plasma accelerators. Nevertheless, due to the large time constant of the discharge circuit, cathode spots have sufficient time to form on the surface, enabling the generation of metallic plasma. Plasma acceleration is driven by the anode potential. Figure 2a demonstrates that the current peak on the substrate occurs 50 μs after the maximum discharge current at the anode.

3.2. Deposition of Coatings

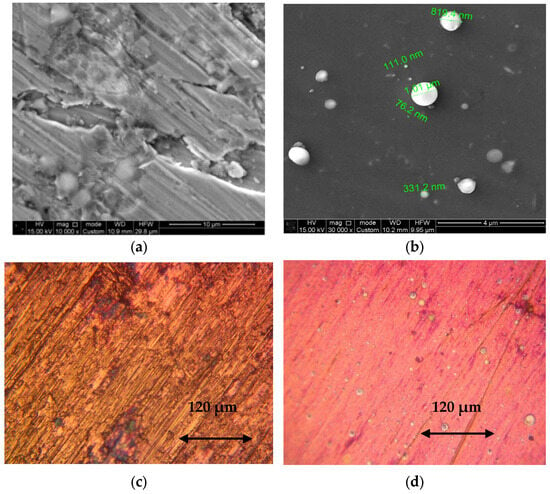

The deposition of copper and aluminum layers on metal substrates appears to be a promising approach for the development of advanced electrical materials technologies. Figure 3 presents SEM images of surfaces coated with aluminum and copper. After spraying onto the metal substrates at time intervals of 20–40 min, the topography of the deposited coatings was analyzed.

Figure 3.

Morphology of layers deposited on various coating/substrate combinations and under different pressures: (a) Thick Al layer on Al substrate deposited at 10−2 mbar (SEM); (b) Cu layer deposited at 10−2 mbar on steel substrate, showing spheroidal particles (SEM); (c) Thick Cu layer on Al substrate deposited at 10−4 mbar (OM, magnification ×20); (d) Thin Al layer deposited at 10−4 mbar on Cu substrate, featuring isolated droplet-like particles (OM, magnification ×20).

At low vacuum, copper and aluminum coatings are deposited on the metal substrate as continuous layers. As shown in Figure 3a, multiple layers of aluminum observed. Microparticles sizes ranging from 0.1 to 1 μm are also present on the Cu layer (Figure 3b). At medium and high vacuum, continuous Cu coatings are similarly formed, as illustrated in Figure 3c. However, under high vacuum, aluminum is deposited as an extremely thin layer. The red appearance of the coating is due to the thinness of the aluminum layer, which allows the underlying copper substrate to be visible. Figure 3d additionally shows the presence of microscopic aluminum droplets.

Data on the variation in elemental composition of surfaces with copper coatings on different substrates are presented in Table A1. For clarity and ease of analysis, Table A1 and Figure 3b,c indicate the copper content on steel and aluminum substrates, as well as the composition of macroparticles appearing as light inclusions on the surface. Table 1 summarizes the presence of the base metal, substrate elements, and residual gas. The concentrations of Cr, Si, F, and Mg were below 3% and are therefore not included in Table A1.

Table 1.

Elemental composition of metal coatings on silicon substrates.

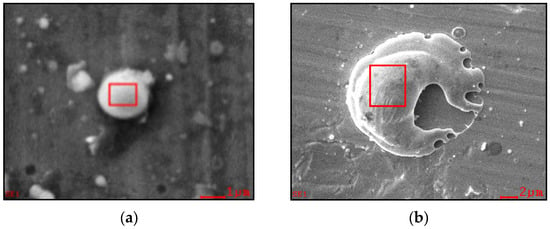

The variation in base metal content within the copper coatings (8.69%–37.89%) is attributed to the thinness of the deposited layer, as substantial amounts of iron and aluminum from the substrate were detected. In other experiments, the base metal content could be increased up to 80%. The particle shown in Figure 4a, deposited on a steel surface at 10−2 mbar, contained significant amounts of carbon and oxygen (Table A1, column 2). In contrast, the droplet of metal deposited on the steel surface at 10−4 mbar (Figure 4b) contained 82.11% copper (Table A1, column 4).

Figure 4.

SEM images of individual Cu microparticles deposited on steel substrates at pressures of 10−2 mbar (a) and 10−4 mbar (b). Red rectangles indicate scanning areas limited on the particle size.

The content of carbon and oxygen in the coatings was initially high, at 31% and 27%, respectively, but decreased three- to fourfold under a vacuum of 10−4 mbar. Carbon originated from oil vapor as well as from the anode holder (fluoroplastic), whereas oxygen was primarily introduced through the dissociation of water molecules in the chamber. Carbon generally deposited on the surface as particulate clusters, where its proportion was not less than one-third (Figure 3b,c). The oxygen content was strongly dependent on the vacuum level and penetrated the base metal, potentially forming compounds, particularly with aluminum.

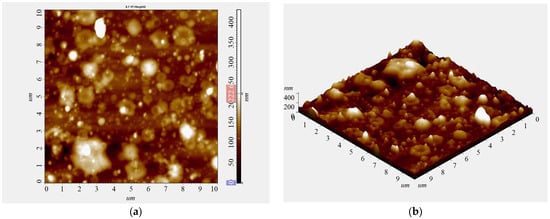

To determine the thickness of coatings on metal substrates, AFM images of the deposit surfaces at scratch locations were analyzed. Figure 5 shows copper-coated steel samples with exposure intervals of 5–20 min. Figure 5a (normal projection) reveals circular clusters smaller than 1 μm, with even smaller clusters attached to them. The 3D view (Figure 5b) indicates that the surface topography is rough, with a height of approximately 400 nm. Film thickness was assessed using the silicon crystal scratch method. Due to the porous nature of the coating caused by dust condensation, the film–substrate interface was readily accessible. Coating thicknesses, determined directly from roughness profiles, ranged from 400 nm to 1.9 μm for deposition times of 10–30 min. Thus, the top layer of the coating can be considered as consisting of agglomerated particles of varying sizes, ranging from 0.1 to 1 μm. The increase in coating thickness is explained by particle aggregation during deposition; however, no further enlargement of particles over time was observed.

Figure 5.

The AFM images of topography of copper coating deposited 10 min on steel substrate ((a)—front image, (b)—3D image). Scanning area (10 × 10) µm.

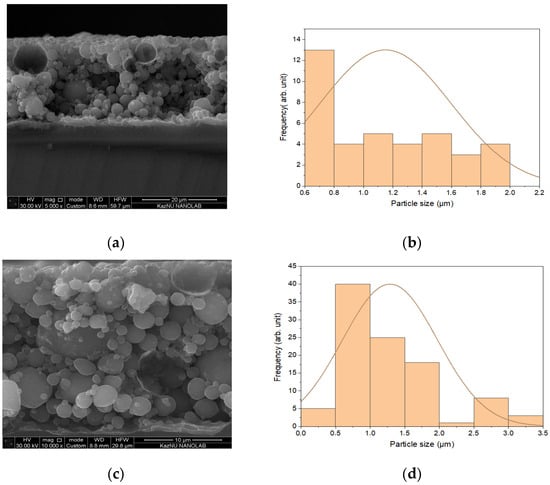

Insulating substrates, in the form of silicon wafer pieces with a resistivity of 10 Ω·m, were also tested. A copper layer deposited on a silicon substrate is shown in Figure 6a, while an aluminum layer on silicon is presented in Figure 6b. Figure 6b,d illustrate the particle size distribution within the Cu and Al layers, respectively.

Figure 6.

Structure of coatings deposited on silicon substrates: (a) Copper layer on silicon substrate exhibiting hollow spheres; (b) Particle size distribution in the Cu layer; (c) Aluminum spheres on silicon substrate with varying sizes; (d) Particle size distribution in the Al layer.

Figure 6a shows spherical Cu structures formed through chemical or other processes during deposition. Figure 6b presents a cross-section of a silicon wafer coated with Al, which similarly consists of spherical particles. Overall, Figure 6a,c indicate that the spheres tend to agglomerate and increase in size. The mechanism of their formation is discussed in Section 4.

From the particle size distribution shown in Figure 6b, it is evident that the copper layer primarily consists of particles measuring 1.0–1.2 μm. For the aluminum coating on the silicon substrate, the average particle size is slightly larger, ranging from 1.4 to 1.5 μm. Figure 6a,c reveal two fractions of spherical particles: larger intact particles and smaller particles featuring open “shells” and cavities. The lighter particles exhibit lower conductivity and are likely aluminum oxides.

The variation in base metal content on silicon substrates for different deposition times is presented in Table 1. The top row indicates deposition time, while the subsequent rows list the elemental content in atomic percent. The aluminum coating shows a slight decrease in metal content from 70% to 65% (row 1) due to gradual oxidation, while the oxygen content approximately doubles to 32% (row 2) during prolonged processing (40 min). In contrast, the copper coating (row 3) exhibits a decrease in oxygen content (row 4), as copper was only weakly oxidized, and the oxygen likely evaporated during sample heating.

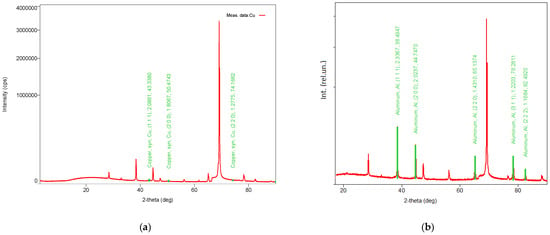

To determine the phase composition of the porous coatings on silicon, X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis was performed. Figure 7 shows that both copper and aluminum exhibit a crystalline structure, although the number of diffraction peaks varies. Since the substrate consists of silicon, the observed metal peaks can be attributed to the surface coatings.

Figure 7.

X-ray diffraction (XRD) spectra of copper (a) and aluminum (b) coatings on a silicon substrate. Deposition time 20 min; pressure 10−4 mbar.

Table 2 provides an estimate of the crystallite sizes determined using the Williamson–Hall method. Aluminum crystallites, with a density of 2.702 g/cm3, are larger (103 nm), whereas copper crystallites are significantly smaller (3.4 nm). It is also evident that aluminum exhibits a higher degree of crystallinity compared to copper. The XRD spectra further reveal numerous weak peaks characteristic of aluminum oxides, particularly corundum (Al2O3). The oxide crystallites are considerably smaller than the aluminum crystallites, suggesting that they are likely located at grain boundaries. This observation is consistent with the data in Table 1 (row 2) regarding changes in the oxygen content of the aluminum coatings.

Table 2.

Phase composition of aluminum and copper coatings on silicon.

4. Discussions

Our device generates a plasma pulse with a current of 750 A, a repetition frequency of 5 Hz, and a duration of 110 μs. We first consider the conditions for generating a predominantly microdroplet component in arc plasma under varying pressures, accelerating voltages, and capacitances. At an anode voltage of 540 V and a vacuum of 10−2 to 10−3 mbar, continuous metal layers containing numerous droplet-phase inclusions were observed on the substrate surfaces. Under the same conditions, copper coatings also formed continuous layers, although the coating color depended on the vacuum level. AFM images reveal that these continuous layers are actually agglomerates of spherical droplets measuring 0.1–1 μm.

As the pressure decreased to 10−4 mbar, the number of microdroplets decreased. Increasing the anode voltage to 750 V caused the droplets to flatten against the surface. The maximum yield of individual metal droplets was observed at anode voltages of 500–750 V and under high vacuum. However, at high vacuum, droplets were partially evaporated by the hot plasma, leading to a reduction in both their number and size. Variation in the device’s discharge capacitance from 400 to 1200 μF did not significantly affect droplet formation. This is particularly evident for aluminum (Figure 3d), where droplet sizes reached 10 μm or more. Overall, the experimental data indicate that the plasma flow initially contains a substantial droplet phase with particle sizes of at least 10 μm. At high pressure, droplets partially evaporate and decrease to approximately 1 μm, whereas at low pressure, they deposit almost unchanged but may flatten upon impact. Notably, metal droplets evaporated from the cathode can become encapsulated in an inorganic shell of carbon and oxygen at low pressure. Spherical particles with sizes of 0.1–1 μm deposited on steel surfaces (Figure 3b), as reflected in Table 1, illustrate this phenomenon, which has been studied previously in similar arc discharge setups. Recent studies on water arcs provide additional details [26].

The adhesion of thick layers formed from the droplet phase at low vacuum, as well as the stability of individual droplets on metal substrates, is poor; the coatings are easily removed. Poor adhesion is attributed to the high residual gas content, which transforms individual particles into dust. Adhesion improves significantly at high vacuum for several reasons: first, a predominantly ionic plasma flow is generated, simultaneously cleaning the substrate surface; second, residual gases are minimal; and third, the substrate is heated to approximately 200 °C, activating chemisorption. This thermal activation influences the dynamics of surface processes. Thermal balance is established such that the substrate undergoes short-term periodic ion bombardment followed by cooling. Due to the insulating nature of vacuum, the sample gradually heats with each pulse, reaching 180 °C after 40 min of operation with an aluminum cathode. Observations indicate that the surface melting temperature is not reached, though sputtering of the substrate by the plasma ion flow is possible. Nevertheless, these temperatures activate segregation processes of oxygen and hydrogen at particle or phase boundaries within the coating’s crystalline structure, as confirmed by the data in Table A1 and Table 2.

As shown in Figure 3, these processes negatively affect the quality of aluminum coatings, accelerating embrittlement and delamination from the substrate. The deposition rate of the coatings, estimated from Figure 5b, ranges from 1 to 3 nm/s. Consequently, the thickness and structure of copper coatings deposited on metal substrates are suitable for creating porous layers. In contrast, aluminum coatings under high vacuum form very thin layers, with cathode material depositing on the substrate predominantly as droplets. The limited sputtering of aluminum is primarily due to its low ion mass and low melting point. The formation of droplets in arc plasma has been extensively discussed in the literature, although the results are highly dependent on the specific details of the accelerator.

Thus, microparticles are deposited along with the ions on the substrates, although their minimum size is unknown. Although this is generally true for any vacuum arc plasma system, a fundamental question concerns the location of this particles formation. We hypothesize that metal particles first enter the plasma near the cathode from the cathode spot and are subsequently evaporated. As the hot plasma travels through the chamber, it cools, and in this region, nanoparticles form from the metal and its compounds with ambient gases, typically as oxides and hydrides. These nanoparticles are then deposited as a uniform metal layer on the substrate. Numerous studies have addressed this phenomenon; for example, in [22], spherical dust particles with sizes of 5–10 nm were deposited. According to Figure 3c, Figure 5 and Figure 6, the nanoscale dust in the thick samples deposited on our substrates has a similar order of magnitude, i.e., well below 100 nm.

Upon reaching the substrate, the particles are periodically heated and irradiated by the plasma. During this stage, gas capture and the formation of a structure of spheres of varying sizes occur, followed by growth to several micrometers via agglomeration. It should be noted that the high-velocity plasma flow from the cathode, as mentioned earlier, can significantly influence sputtering on the substrate. In this case, two pulses must be considered: the first is a flow of fast ions, followed 50 μs later by a flow of normal ions. However, given the low amplitude of the fast ion flow shown in Figure 2, this effect is likely secondary.

We further consider the formation of hollow spheres on silicon substrates. Our initial hypothesis is that shelled spheres form when filled with gas internally. Exposed to high-enthalpy plasma during transit from the cathode to the substrate, metal nanoparticles can aggregate into geometrically regular structures—spheres measuring 1–100 μm. This process is described in the review [23] and theoretically analyzed in [24]. Unlike atmospheric plasma torches and arc discharges, our setup operates under high vacuum; consequently, spheroids were observed only on the sample surfaces. The characteristics of the spheroids synthesized in our setup are as follows:

- Spheroidal particles formed on steel substrates are relatively small, ranging from 0.1 to 1 μm.

- Hollow spheroidal particles with diameters of 1–10 μm and wall thicknesses below 1 μm form on silicon surfaces.

- Merging and growth of spheres over exposure time were observed for both types of substrates.

We propose that one pathway for the formation of metallic bubbles involves filling with hydrogen. In this hypothetical mechanism, gas is first chemisorbed in the coating material and then, upon heating, desorbed from the surface, forming hollow spheres of minimal size. Supporting this hypothesis, ref. [22] reports spherical structures on the surface of an oxide coating (thin aluminum layer).

A critical question is the possibility of metal melting on the surface. With a pulsed ion beam, surface melting temperatures can be reached in short time intervals. This condition is typical for ion accelerators and also applies to plasma devices. Thus, gas evaporation from the substrate remains a working hypothesis but has not yet been experimentally verified.

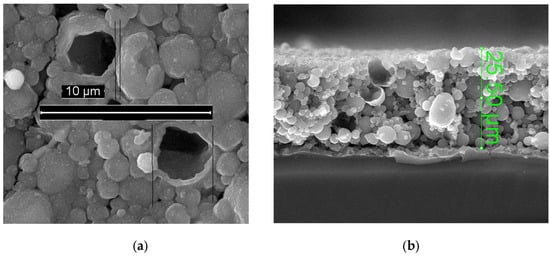

At present, the wall thickness and size of cracked hollow particles can be determined. In Figure 8a, the particle wall thickness is 0.3 ± 0.1 µm, and the two largest particles measure approximately 4 ± 1 µm. In Figure 8b, the largest particles reach sizes of 8 ± 1 µm.

Figure 8.

Hollow copper spheres on a silicon substrate: (a) Front surface view; (b) Cross-sectional view.

5. Conclusions

The developed setup generates a flow of erosive metal plasma, the composition of which is determined by the cathode material. Process parameters influencing the composition of the deposited coatings include chamber pressure, deposition time, and substrate material. At a high vacuum of approximately 10−4 mbar, thin metal layers up to a few nanometers thick with a uniform structure are deposited on metal substrates. However, high-resolution atomic microscopy reveals the presence of microparticles ranging from 0.1 to 10 µm, which exhibit strong agglomeration.

At vacuum levels above 10−2 mbar, metal vapor from the cathode interacts with residual gas, resulting in the deposition of thicker layers on metal substrates. With increasing deposition time, microscopic particles up to several microns in size condense from the plasma, containing oxygen and carbon contents up to 21% and 32%, respectively. On silicon substrates, thick layers up to 25 µm form, consisting of hollow spherical shells with wall thicknesses up to 0.3 µm. Analysis of processes within the arc device suggests that the nucleation and growth of hollow shells may be related to gas adsorbed within the coating. Further research is required, as the process can potentially be controlled by introducing a buffer gas and increasing beam energy. Unlike atmospheric plasma technologies for microsphere production, our system enables the formation of spherical particles without introducing external powders, using the cathode itself as the metal source.

At pulsed discharge currents on the order of 1 kA, severe cathode erosion occurs, releasing metal into the vacuum. During expansion into the chamber, droplets undergo various thermodynamic and electrical processes, resulting in their deposition on the substrate as microparticles. The size and density of the deposited particles can be precisely controlled, as all processes within the accelerator are governed by the electric field. Free expansion of the vapor allows rapid cooling, sufficient to initiate nucleation, followed by particle growth through coalescence. The presence of a buffer gas in the chamber plays a critical role, as high-vacuum conditions yield significantly fewer macroparticles. Determining the optimal gas pressure to achieve a desired macroparticle size requires preliminary calculations; experimental data suggest pressures above 10−2 mbar.

Future research could explore the use of buffer gases to study the dynamics of hollow shell formation and their detachment from substrates, potentially assisted by processes such as substrate rotation. Additionally, the production of metals encapsulated in carbon shells represents a promising direction for powder manufacturing, considering both the energy efficiency of the process and the high purity achievable under vacuum conditions.

Author Contributions

A.M.Z.—problem statement, references analysis, conclusions, funding of work; U.B.A.—experiments, instruments, measurements, draft text. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research funding from Ministry of Education and Science of the Republic of Kazakhstan under Grant Agreement No. AP 19676182.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm the availability of the data obtained in this work at the request to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

The chemical content of layers and particles on different substrates.

Table A1.

The chemical content of layers and particles on different substrates.

| Element, At % | 10−2 mbar | 10−4 mbar | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cu/Steel | Macroparticle a | Cu/Steel | Macroparticle b | Cu/Al | |

| № col. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Cu (Al) | 37.89 | 22.43 | 26.23 | 82.11 | 8.69 (71.3) |

| Fe | 34.78 | 21.02 | 47.77 | - | - |

| C | - | 31.61 | 24.56 | 15.95 | 8.37 |

| O | 27.33 | 21.95 | - | 1.94 | 11.06 |

References

- Li, D.; Liu, Y.; Xie, Y.; Wang, X.; He, D.; Wang, P.; Xiong, L. Porous powder anode for high performance rechargeable aluminum batteries. J. Power Sources 2025, 641, 236860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Zhang, Z.; Yan, L.; Li, C.; Li, H.; Qiao, Z.; Yu, Z.; Li, W.; Wang, N.; Jiang, Y. A novel superimposed porous copper/carbon film derived from polymer matrix as catalyst support for metal-air battery. J. Porous Mater. 2022, 29, 249–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Li, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, W.; Qin, C. Nanoporous Quasi-High-Entropy Alloy Microspheres. Metals 2019, 9, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flegel, S.; Hatada, R.; Jantsen, G.; Walbert, T.; Ensinger, W.; Morimura, T.; Muench, F. Nanoparticles as a Metal Source in Plasma Processes. Trans. Mater. Res. Soc. Jpn. 2017, 42, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golizadeh, M.; Martin, F.M.; Wurster, S.; Mogeritsch, J.P.; Kharicha, A.; Kolozsvári, S.; Mitterer, C.; Franz, R. Rapid solidification and metastable phase formation during surface modifications of composite Al-Cr cathodes exposed to cathodic arc plasma. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2021, 94, 147–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jüttner, B. Cathode spots of electric arcs. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2001, 34, R103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksenov, I.I.; Aksyonov, D.S. Physical aspects of vacuum-arc coating deposition. East Eur. J. Phys. 2014, 1, 22–39. [Google Scholar]

- Anders, A. Cathodic Arc: From Fractal Spots to Energetic Condensation; Springer Science: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegner, K.; Walker, B.; Tsantilis, S.; Pratsinis, S.E. Design of metal nanoparticles synthesis by vapor flow condensation. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2002, 57, 1753–1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesyats, G.A.; Barengol’ts, S.A. Mechanism of anomalous ion generation in vacuum arcs. Physics-Uspekhi 2002, 45, 1001–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beilis, L.L. Nature of high-energy ions in the cathode plasma jet of a vacuum arc with high rate of current rise. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2004, 85, 27392740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rysanek, F.; Burton, R.L.; Keidar, M. Macroparticle Charging in a Pulsed Vacuum Arc Thruster Discharge. In Proceedings of the 42nd AIAA/ASME/SAE/ASEE Joint Propulsion Conference & Exhibit, Sacramento, CA, USA, 9–12 July 2006; American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics, Inc.: Reston, VA, USA, 2006. AIAA 2006-4499. [Google Scholar]

- Hantzsche, E. Mysteries of the arc cathode spot: A retrospective glance. IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 2003, 31, 799–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batrakov, A.V.; Jüttner, B.J.; Popov, S.A.; Proskurovskii, D.I.; Vogel, N.I. Droplet spot as a new object in physics of vacuum discharge. J. Exp. Theor. Phys. Lett. 2002, 75, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beilis, I. Cathode Spot Jets. Velocity and Ion Current. In Plasma and Spot Phenomena in Electrical Arcs; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 347–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.; Zhou, Q.; Yang, W.; Sun, Q.; Dong, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Z. Particle simulation on the ion acceleration in vacuum arc discharge. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 2023, 32, 095002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozyrev, A.V.; Kozhevnikov, V.Y.; Semeniuk, N.S.; Kokovin, A.O. Initial kinetics of electrons, ions and electric field in planar vacuum diode with plasma cathode. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 2023, 32, 105010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muratovich, A.; Gabdullina, A.T.; Amrenova, A.; Ibraev, B. The deposition of films and particles using pulsed vacuum arc plasma at different pressure and temperature. High Temp. Mater. Process. 2020, 24, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ushakov, A.V.; Karpov, I.V.; Lepeshev, A.A.; Fedorov, L.Y.; Dorozhkina, E.A.; Karpova, O.N.; Shaikhadinov, A.A.; Demin, V.G.; Bachurina, E.P.; Lichargin, D.V. Particular Charactristics of the Synthesis of Titanium Nitride Nanopowders in the Plasma of Low Pressure Arc Discharge. In Proceedings of the XX International Scientific Conference Reshetnev Readings-2016, Krasnoyarsk, Russia, 9–12 November 2016; 2017; Volume 255, p. 012006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodionov, A.I.; Efimochkin, I.Y.; Buyakina, A.A.; Letnikov, M.N. Spheroidization of metal powders (review). Aviat. Mater. Technol. 2016, 43, 60–64. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solonenko, O.P.; Gulyaev, I.P.; Smirnov, A.V. Thermal Plasma Processes for Production of Hollow Spherical Powders: Theory and Experiment. J. Therm. Sci. Technol. 2011, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larichev, M.N.; Shaitura, N.S.; Artemov, V.V. Spherical Aluminum Shells (Bubbles) with Nanodimensional Wall Thickness: A New Class of 2D Nanoobjects. Tech. Phys. Lett. 2021, 47, 379–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Dai, L.; Luo, T.; Wang, L.; Liang, F.; Liu, S. Recent advances in solid-state metal–air batteries. Carbon Energy 2022, 1, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Sun, Y.; Ren, W.; Zhang, D.; Yang, Y.; Yang, J.; Wang, J.; Zeng, X.; NuLi, Y. Challenges and prospects of Mg-air batteries: A review. Energy Mater. 2022, 2, 200024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.-F.; Xu, Q. Materials Design for Rechargeable Metal-Air Batteries. Matter 2019, 1, 565–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Li, J.; Li, Y. A review of plasma liquid interactions for nanomaterial sinthesis. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2015, 48, 4240005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.