Thermal Aging-Induced Alterations in Surface and Interface Topography of Bio-Interactive Dental Restorative Materials Assessed by 3D Non-Contact Profilometry

Highlights

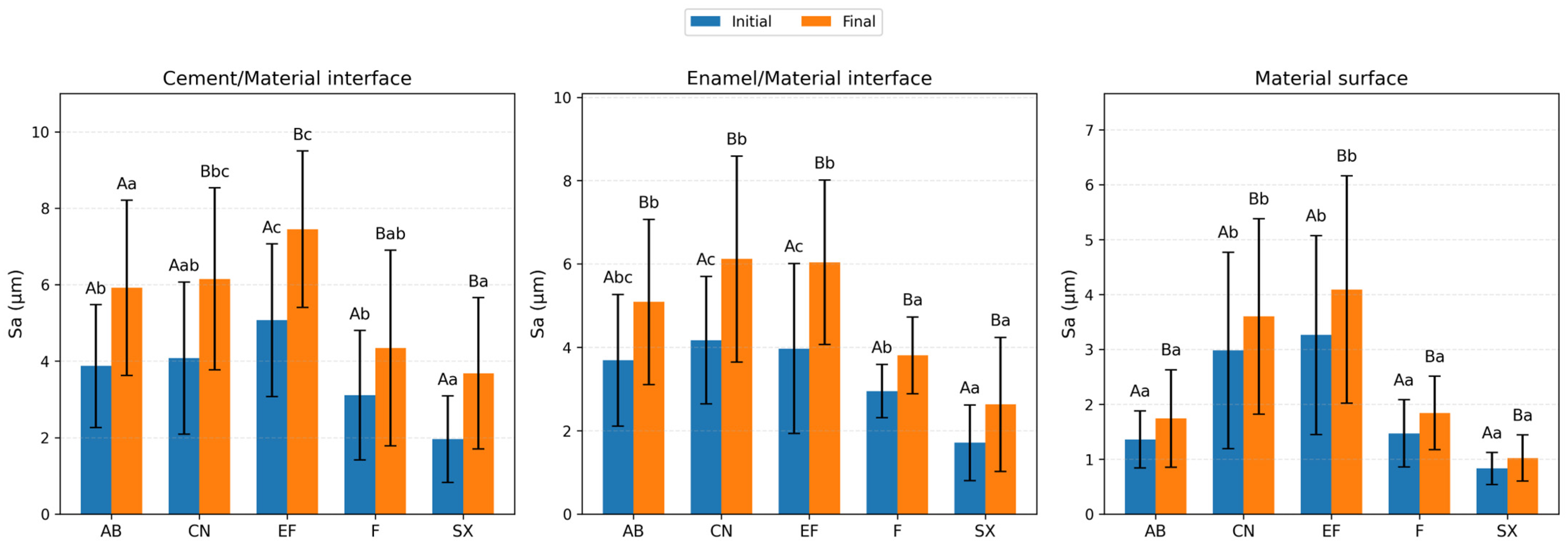

- Surface roughness changes varied among the restorative materials evaluated and thermal aging increased the areal surface roughness (Sa) of all tested restorative materials.

- Interface regions (enamel/material and cement/material) showed higher roughness values than material surfaces.

- 3D non-contact profilometry enabled detailed assessment of surface and interface topography.

- The glass-hybrid restorative system with protective coating exhibited a different roughness pattern compared with other materials.

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- Thermal aging has no significant effect on the surface roughness of different restorative materials.

- (2)

- Thermal aging has no significant effect on the surface roughness of restorative material–enamel interfaces.

- (3)

- Thermal aging has no significant effect on the surface roughness of restorative material–cement interfaces.

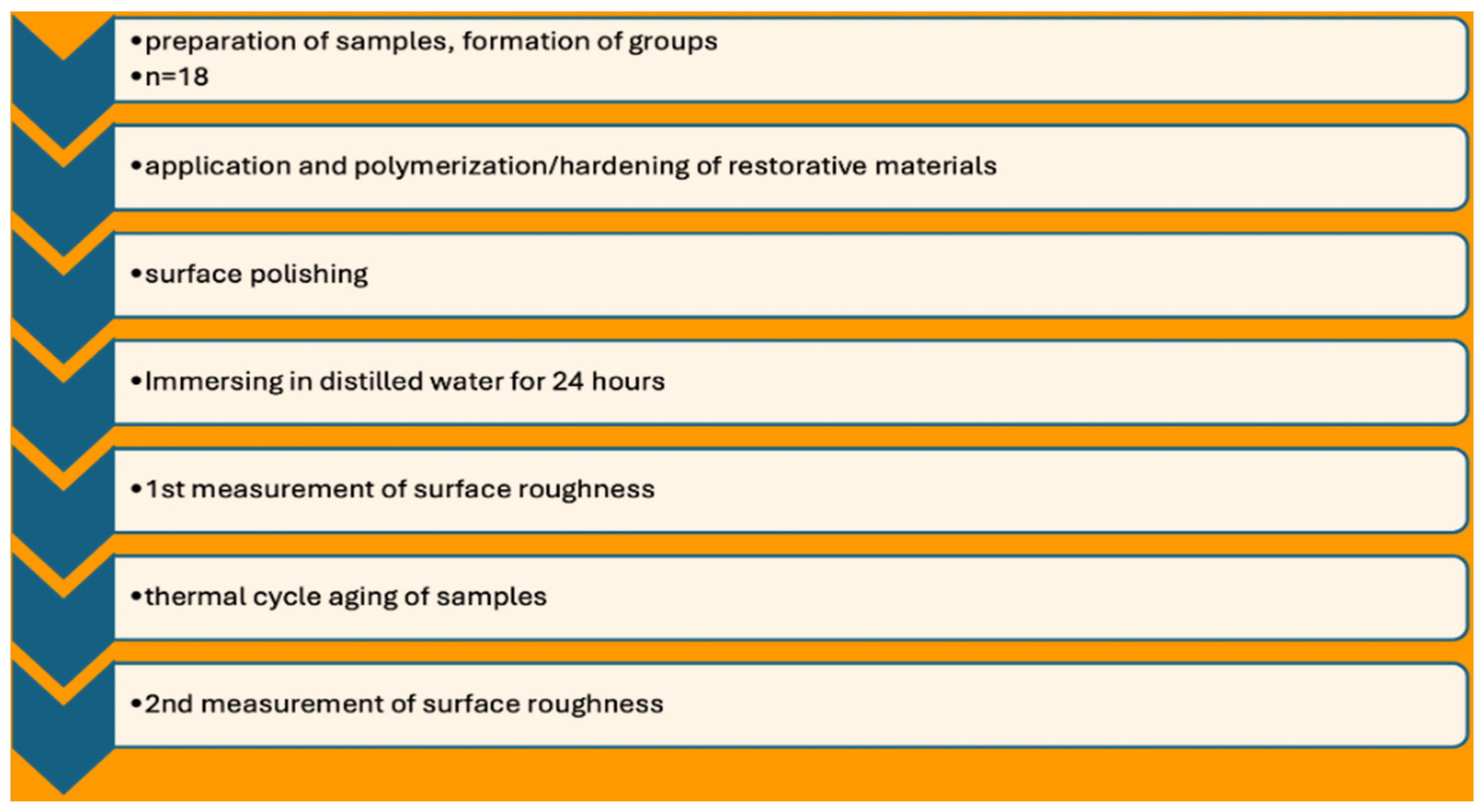

2. Materials and Methods

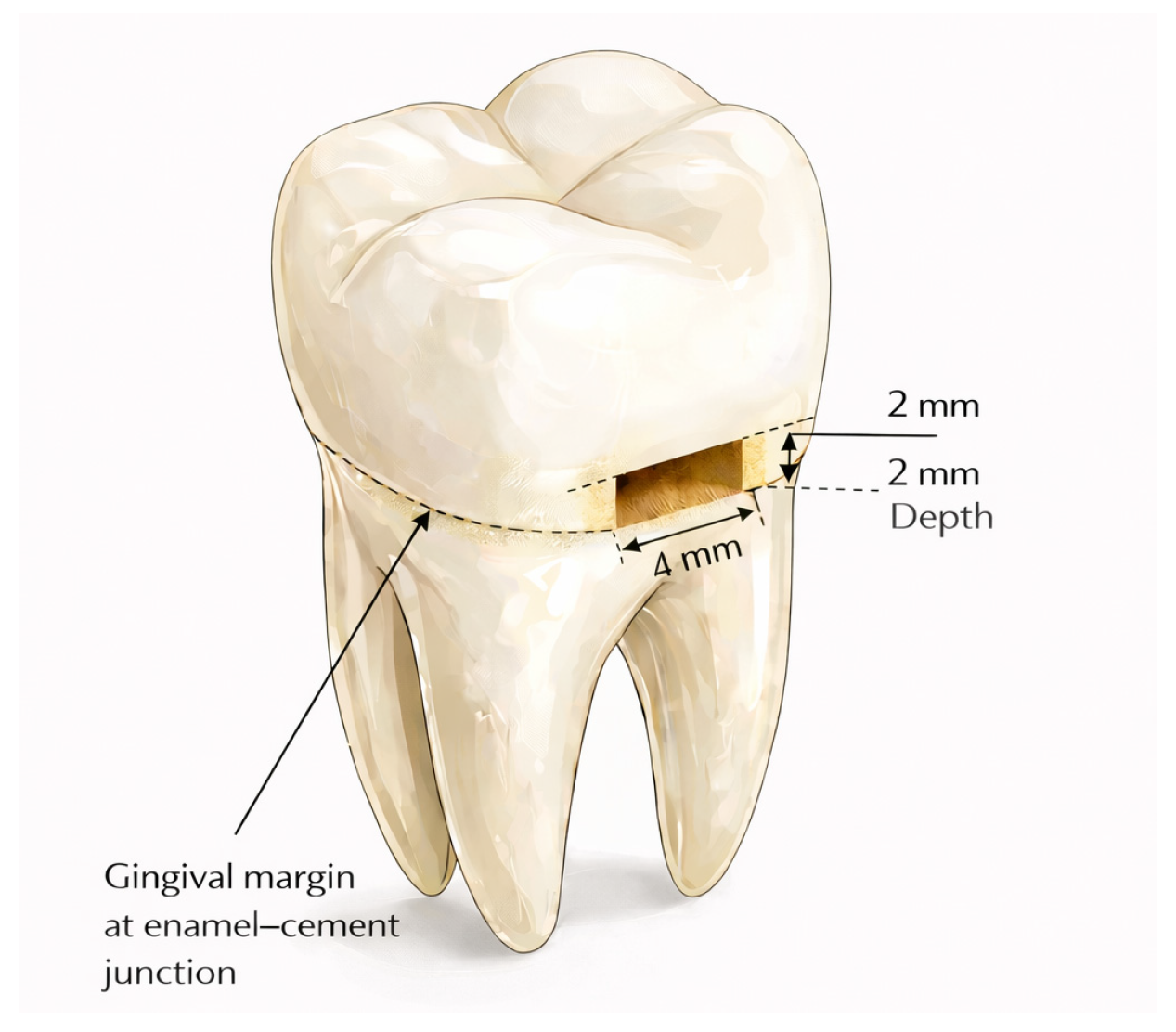

2.1. Sample Preparation

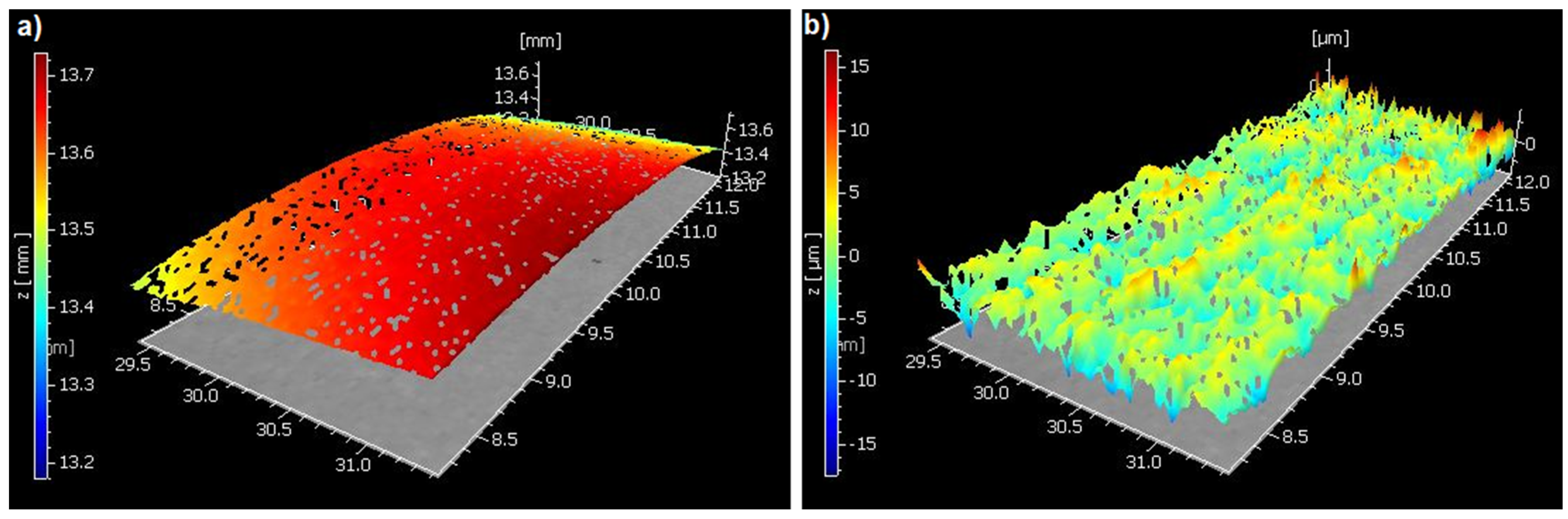

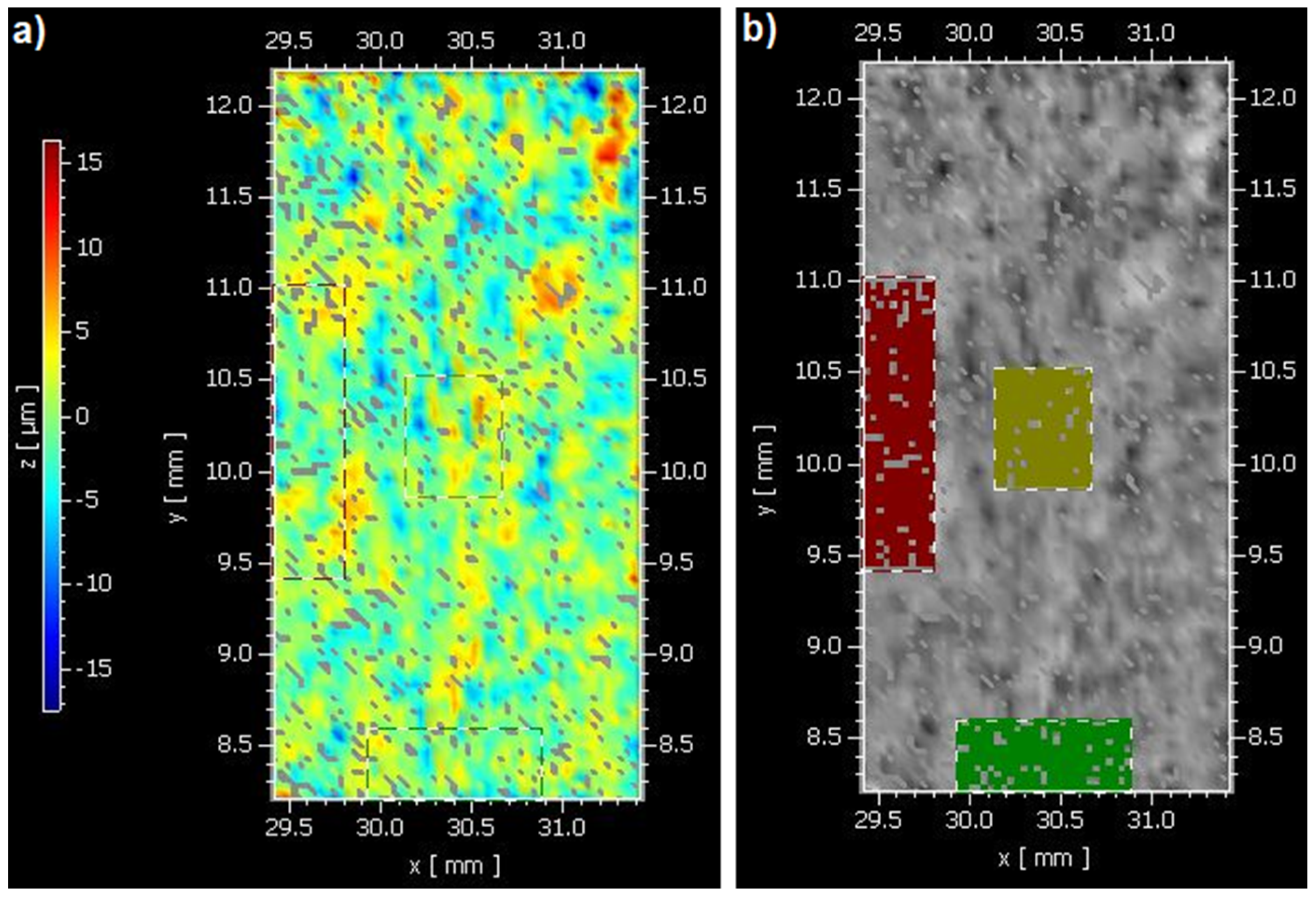

2.2. Areal Surface Roughness Measurement (Sa)

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AB | Activa BioActive Restorative |

| CN | Cention-N |

| EF | Equia Forte |

| F | Fuji II Light-cured |

| GIC | Glass ionomer cement |

| ISO | International Organization for Standardization |

| LED | Light-emitting diode |

| SX | Solare-X |

| μm | micrometer |

References

- Doğu Kaya, B.; Acar, E.; Farshidian, N.; Göçmen, G.B.; Tarçın, B.; Atalı, P.Y.; Tarçın, B. The effect of cavity disinfectant on microleakage of self adhesive composite restorations in class V cavities. Eur. J. Res. Dent. 2023, 7, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lokhande, N.A.; Padmai, A.S.; Rathore, V.P.S.; Shingane, S.; Jayashankar, D.N.; Sharma, U. Effectiveness of flowable resin composite in reducing microleakage—An in vitro study. J. Int. Oral Health 2014, 6, 111–114. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Alcaraz, M.G.R.; Veitz Keenan, A.; Sahrmann, P.; Schmidlin, P.R.; Davis, D.; Iheozor Ejiofor, Z. Direct composite resin fillings versus amalgam fillings for permanent or adult posterior teeth. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014, CD005620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favetti, M.; Montagner, A.F.; Fontes, S.T.; Martins, T.M.; Masotti, A.S.; Jardim, P.D.S.; Corrêa, F.O.B.; Cenci, M.S.; Muniz, F.W.M.G. Effects of cervical restorations on periodontal tissues: 5 year follow up of a randomized clinical trial. J. Dent. 2021, 106, 103571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slimani, A.; Sauro, S.; Gatón Hernández, P.; Gurgan, S.; Turkun, L.S.; Miletic, I.; Banerjee, A.; Tassery, H. Commercially available ion releasing dental materials and cavitated carious lesions: Clinical treatment options. Materials 2021, 14, 6272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nedeljkovic IDe Munck, J.; Slomka, V.; Van Meerbeek, B.; Teughels, W.; Van Landuyt, K.L. Lack of buffering by composites promotes shift to more cariogenic bacteria. J. Dent. Res. 2016, 95, 875–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hench, L.L. Bioceramics: From concept to clinic. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 1991, 74, 1487–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hench, L.L.; Polak, J.M. Third generation biomedical materials. Science 2002, 295, 1014–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokubo, T.; Kim, H.M.; Kawashita, M. Novel bioactive materials with different mechanical properties. Biomaterials 2003, 24, 2161–2175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.G.; Lee, B.N.; Jeong, H.J.; Kim, H.J.; Kwon, J.; Oh, S.; Kim, D.-S.; Choi, K.-K.; Kim, R.H.; Jang, J.-H. Effect of bioactive glass into mineral trioxide aggregate on biocompatibility and mineralization potential of dental pulp stem cells. Biomater. Res. 2025, 29, 0142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiremath, G.; Pramanik, S.; Horatti, P. Comparative evaluation of bioactivity of MTA Plus and MTA Plus chitosan conjugate in phosphate buffer saline: An in vitro study. Saudi Dent. J. 2024, 36, 1097–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Primus, C.; Gutmann, J.L.; Tay, F.R.; Fuks, A.B. Calcium silicate and calcium aluminate cements for dentistry reviewed. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2022, 105, 1841–1863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gündoğar, Z.U.; Keskin, G.; Yaman Küçükersen, M. Shear Bond Strength of Biointeractive Restorative Materials to NeoMTA Plus and Biodentine. Polymers 2025, 17, 3070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pires, P.M.; Neves, A.D.A.; Makeeva, I.M.; Schwendicke, F.; Faus-Matoses, V.; Yoshihara, K.; Banerjee, A.; Sauro, S. Contemporary restorative ion-releasing materials: Current status, interfacial properties and operative approaches. Br. Dent. J. 2020, 229, 450–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmalz, G.; Hickel, R.; Price, R.B.; Platt, J.A. Bioactivity of dental restorative materials: FDI policy statement. Int. Dent. J. 2023, 73, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almuhaiza, M. Glass-ionomer cements in restorative dentistry: A critical appraisal. J. Contemp. Dent. Pract. 2016, 17, 331–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atalay, C.; Yazici, A.R. Effect of radiotherapy on surface roughness and microhardness of contemporary bioactive restorative materials. Support. Care Cancer 2024, 32, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Kulkarni, G.; Kumar, R.S.M.; Jain, R.; Lokhande, A.M.; Sitlaney, T.K.; Ansari, M.H.F.; Agarwal, N.S. Comparative evaluation of biological response of conventional and resin-modified glass ionomer cement on human cells: A systematic review. Restor. Dent. Endod. 2024, 49, e41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GC Fuji II LC Capsule—Instructions for Use. Available online: https://gclatinamerica.com/assets/doctos/descargas/111/F2LCbrochure.pdf (accessed on 25 December 2025).

- Ruengrungsom, C.; Burrow, M.F.; Parashos, P.; Palamara, J.E.A. Evaluation of F, Ca, and P release and microhardness of eleven ion-leaching restorative materials and recharge efficacy using new Ca/P fluoride varnish. J. Dent. 2020, 102, 103474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theerarath, T.; Sriarj, W. An alkasite restorative material effectively remineralized artificial interproximal enamel caries in vitro. Clin. Oral Investig. 2022, 26, 4437–4445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garoushi, S.; Vallittu, P.K.; Lassila, L. Characterization of fluoride releasing restorative dental materials. Dent. Mater. J. 2018, 37, 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaramillo-Cartagena, R.; López-Galeano, E.J.; Latorre-Correa, F.; Agudelo-Suárez, A.A. Effect of polishing systems on the surface roughness of nano-hybrid and nano-filling composite resins: A systematic review. Dent. J. 2021, 9, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, Y.; Huang, X.; Zhou, X.; Li, M.; Ren, B.; Peng, X.; Cheng, L. Influence of dental prosthesis and restorative materials interface on oral biofilms. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 3157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babina, K.; Polyakova, M.; Sokhova, I.; Doroshina, V.; Arakelyan, M.; Novozhilova, N. The effect of finishing and polishing sequences on the surface roughness of three different nanocomposites and composite/enamel and composite/cementum ınterfaces. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ereifej, N.S.; Oweis, Y.G.; Eliades, G. The effect of polishing technique on 3-D surface roughness and gloss of dental restorative resin composites. Oper. Dent. 2013, 38, E1–E12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chour, R.G.; Moda, A.; Arora, A.; Arafath, M.Y.; Shetty, V.K.; Rishal, Y. Comparative evaluation of effect of different polishing systems on surface roughness of composite resin: An in vitro study. J. Int. Soc. Prev. Community Dent. 2016, 6, 166–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, Y.C.; Lai, E.H.H.; Kunzelmann, K.H. Polishing mechanism of light-initiated dental composite: Geometric optics approach. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 2016, 115, 1053–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakaboura, A.; Fragouli, M.; Rahiotis, C.; Silikas, N. Evaluation of surface characteristics of dental composites using profilometry, scanning electron, atomic force microscopy and gloss-meter. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2007, 18, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosentritt, M.; Schneider-Feyrer, S.; Kurzendorfer, L. Comparison of surface roughness parameters Ra/Sa and Rz/Sz with different measuring devices. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2024, 150, 106349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leach, R.; Haitjema, H. Bandwidth characteristics and comparisons of surface texture measuring instruments. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2010, 21, 079801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vorburger, T.V.; Rhee, H.-G.; Renegar, T.B.; Song, J.-F.; Zheng, A. Comparison of optical and stylus methods for measurement of surface texture. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2007, 33, 110–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holthuizen, P.; Çopuroğlu, O. Quantification of surface grinding during the sample preparation of cementitious materials by optical profilometry. J. Microsc. 2024, 294, 128–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demircioglu, P. A comparison between contact type profilometer and different 3D optical techniques: A case study in characterization of machined surface structures. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Quality and Innovation in Engineering and Management, Cluj-Napoca, Romania, 22 November 2012; pp. 117–122. [Google Scholar]

- EN ISO 25178-1:2016; Geometrical Product Specifications (GPS)—Surface Texture: Areal-Part 1, Indication of Surface Texture. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016.

- Park, J.-B.; Jeon, Y.; Ko, Y. Effects of titanium brush on machined and sand-blasted/acid-etched titanium disc using confocal microscopy and contact profilometry. Clin. Oral Implants Res. 2015, 26, 130–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodnar, D.; Dumitriu, A.; Suciu, I.; Dimitriu, B.; Chirilă, M.; Bartok, R.; Ciocârdel, M.; Țâncu, A.M.; Straja, D. Microscopic and statistical evaluation of the marginal defects of composite restorations: In vitro studies. J. Med. Life 2024, 17, 625–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, G.; Rehani, U.; Rana, V. A Comparative Evaluation of Marginal Leakage of Different Restorative Materials in Deciduous Molars: An in Vitro Study. Int. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 2012, 5, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuncer, S.; Demirci, M.; Tiryaki, M.; Ünlü, N.; Uysal, Ö. The effect of a modeling resin and thermocycling on the surface hardness, roughness, and color of different resin composites. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2013, 25, 404–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scholz, K.J.; Hinderberger, M.; Widbiller, M.; Federlin, M.; Hiller, K.; Buchalla, W. Influence of Selective Caries Excavation on Marginal Penetration of Class II Composite Restorations in Vitro. Eur. J. Oral Sci. 2020, 128, 405–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, M.C.; Vieira, R.S. Marginal leakage in direct and ındirect composite resin restorations in primary teeth: An in vitro study. J. Dent. 2008, 36, 322–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cenci, M.S.; Pereira-Cenci, T.; Donassollo, T.A.; Sommer, L.; Strapasson, A.; Demarco, F.F. Influence of thermal stress on marginal integrity of restorative materials. J. Appl. Oral Sci. 2008, 16, 106–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boussès, Y.; Brulat-Bouchard, N.; Bouchard, P.O.; Tillier, Y. A numerical, theoretical and experimental study of the effect of thermocycling on the matrix-filler interface of dental restorative materials. Dent. Mater. 2021, 37, 772–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.H.; Choi, Y.S.; Kang, K.H.; Att, W. Effects of thermal and mechanical cycling on the mechanical strength and surface properties of dental cad-cam restorative materials. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2022, 128, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salerno, M.; Loria, P.; Matarazzo, G.; Tomè, F.; Diaspro, A.; Eggenhöffner, R. Surface morphology and tooth adhesion of a novel nanostructured dental restorative composite. Materials 2016, 9, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Furuse, A.Y.; Santana, L.O.C.; Rizzante, F.A.P.; Ishikiriama, S.K.; Bombonatti, J.F.; Correr, G.M.; Gonzaga, C.C. Delayed light activation improves color stability of dual-cured resin cements. J. Prosthodont. 2018, 27, 449–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kose, H.D.; Giray, I.; Boyacioglu, H.; Turkun, L.S. Can energy drinks affect the surface quality of bioactive restorative materials? BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN ISO 25178-2:2022; Geometrical Product Specifications (GPS)—Surface texture: Areal-Part 2, Terms, Definitions and Surface Texture Parameters. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022.

- Kazak, M.; Koymen, S.; Yurdan, R.; Tekdemir, K.; Donmez, N. Effect of thermal aging procedure on the microhardness and surface roughness of fluoride ion containing materials. Ann. Med. Res. 2020, 27, 888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do Amaral, F.L.; Colucci, V.; De Souza-Gabriel, A.E. Adhesion to er: Yag laser-prepared dentin after long- term water storage and thermocycling. Oper. Dent. 2008, 33, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshali, R.Z.; Silikas, N.; Satterthwaite, J.D. Surface roughness evaluation of resin composites after prolonged aging and different polishing protocols. Int. J. Dent. 2023, 2023, 4078788. [Google Scholar]

- Bakar, W.; Mcintyre, W.Z. Susceptibility of selected tooth-coloured dental materials to damage by common erosive acids. Aust. Dent. J. 2008, 53, 226–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niazi, F.H.; Alotaibi, B.; Abdulla, A.M.; AlTowayan, S.A.; Ahmed, S.Z.; Alshehri, D.; Samran, A.; Alsuwayyigh, N.; Luddin, N. Modified experimental adhesive with sepiolite nanoparticles on caries dentin treated with femtosecond laser and photodynamic activated erythrosine. An in vitro study. Photodiagn. Photodyn. Ther. 2024, 49, 104306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EN ISO 25178-6:2010; Geometrical Product Specifications (GPS)—Surface texture: Areal-Part 6: Classification of Methods for Measuring Surface Texture. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010.

- EN ISO 25178-604:2013; Geometrical Product Specifications (GPS)—Surface texture: Areal-Part 604: Nominal Characteristics of Non-Contact (Coherence Scanning Interferometry) Instruments. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013.

- ISO 25178-2:2012; Geometrical Product Specifications (GPS)—Surface Texture: Areal—Part 2: Terms, Definitions and Surface Texture Parameters. Polski Komitet Normalizacyjny, Wydział Wydawnictw Normalizacyjnych: Warszawa, Poland, 2014.

- Peker, O.; Bolgul, B. Evaluation of surface roughness and color changes of restorative materials used with different polishing procedures in pediatric dentistry. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 2023, 47, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqahtani, A.S.; Al-Qutobi, I.A.; Al-Shammari, K.F.; Almutairi, A.; Al-Rabiah, A. Comparison of marginal integrity and surface roughness of CoCr copings fabricated by different fabrication techniques. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 8328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, F.G.; Romano, A.R.; Correa, M.B.; Demarco, F.F. Influence of microleakage, surface roughness and biofilm control on secondary caries formation around composite resin restorations: An in-situ evaluation. J. Appl. Oral Sci. 2009, 17, 61–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, W.-Y. Microleakage in different primary tooth restorations. J. Chin. Med. Assoc. 2016, 79, 228–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karadaş, M.; Demirbuğa, S. Evaluation of color stability and surface roughness of bulk-fill resin composites and nanocomposites. Meandros Med. Dent. J. 2017, 18, 199–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhadra, D.; Shah, N.C.; Rao, A.S.; Dedania, M.S.; Bajpai, N. A 1-year comparative evaluation of clinical performance of nanohybrid composite with activa bioactive composite in class ıı carious lesion: A randomized control study. J. Conserv. Dent. 2019, 22, 92–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraga, M.A.A.; Correr-Sobrinho, L.; Sinhoreti, M.A.C.; Carletti, T.M.; Correr, A.B. Do dual-cure bulk-fill resin composites reduce gaps and improve depth of cure. Braz. Dent. J. 2021, 32, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Liu, H.; Wang, Y. Different depth-related polymerization kinetics of dual-cure, bulk-fill composites. Dent. Mater. 2019, 35, 1095–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortengren, U.; Wellendorf, H.; Karlsson, S.; Ruyter, I.E. Water sorption and solubility of dental composites and identification of monomers released in an aqueous environment. J. Oral Rehabil. 2001, 28, 1106–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamanel, K. Effect of different prophylactic polishing procedures on the surface roughness of microhybrid and nanohybrid resin composites. Cumhur. Dent. J. 2018, 21, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güner, Z.; Köse, H.D. Evaluation of nanohardness, elastic modulus, and surface roughness of fluoride-releasing tooth-colored restorative materials. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 2024, 48, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sajini, S.I.; Mushayt, A.B.; Almutairi, T.A.; Abuljadayel, R. Color stability of bioactive restorative materials after immersion in various media. J. Int. Soc. Prev. Community Dent. 2022, 12, 418–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Mata, M.; Santos-Pinto, L.; Cilense Zuanon, A.C. Influences of the insertion method in glass ionomer cement porosity. Microsc. Res. Tech. 2012, 75, 667–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Zangana, T.; Tuygunov, N.; Yahya, N.A.; Aziz, A.A. The impact of resin coatings on the properties and performance of glass ionomer cements: A systematic review. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2025, 169, 107044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanik, Ö.; Turkun, L.S.; Dasch, W. In vitro abrasion of resin-coated highly viscous glass ionomer cements: A confocal laser scanning microscopy study. Clin. Oral Investig. 2017, 21, 821–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugurlu, M. How do the surface coating and one-year water aging affect the properties of fluoride-releasing restorative materials? Niger. J. Clin. Pract. 2020, 23, 720–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, B.; Chhabra, N.; Jain, D. Effect of different polishing systems on the surface roughness of nano-hybrid composites. J. Conserv. Dent. 2016, 19, 37–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bollen, C.M.L.; Lambrechts, P.; Quirynen, M. Comparison of Surface Roughness of Oral Hard Materials to the Threshold Surface Roughness for Bacterial Plaque Retention: A Review of the Literature. Dent. Mater. 1997, 13, 258–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehrke, P.; Dinkel, J.; Fischer, C.; Schmenger, K.; Sader, R. Surface Roughness and Necessity of Manual Refinishing Requirements of CAD/CAM-Manufactured Titanium and Cobalt-Chrome Bars—A Pilot Study. Open Dent. J. 2019, 13, 316–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchenau, T.; Mertens, T.; Lohner, H.; Bruening, H.; Amkreutz, M. Comparison of optical and stylus methods for surface texture characterisation in industrial quality assurance of post-processed laser metal additive Ti-6Al-4V. Materials 2023, 16, 4815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamczak, S.; Świderski, J.; Stępień, K.; Dobrowolski, T.; Chmielik, I.P. Comparative analysis of surface roughness measurements obtained with the use of contact stylus profilometry and coherence scanning interferometry. In Proceedings of the XXI IMEKO World Congress Measurement in Research and Industry, Prague, Czech Republic, 30 August 2015; Available online: https://www.imeko.org/publications/wc-2015/IMEKO-WC-2015-TC14-316.pdf (accessed on 25 December 2025).

- Ruzova, T.A.; Haddadi, B. Surface roughness and its measurement methods—Analytical review. Results Surf. Interfaces 2025, 19, 100441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raszewski, Z.; Brząkalski, D.; Derpeński, Ł.; Jałbrzykowski, M.; Przekop, R.E. Aspects and Principles of Material Connections in Restorative Dentistry-A Comprehensive Review. Materials 2022, 15, 7131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bourgi, R.; Kharouf, N.; Cuevas-Suárez, C.E.; Lukomska-Szymanska, M.; Haikel, Y.; Hardan, L. A Literature Review of Adhesive Systems in Dentistry: Key Components and Their Clinical Applications. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 8111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Materials | Type | Compositions | Manufacturer | LOT Numbers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Equia Forte (EF) | High-viscosity glass ionomer cement | Powder: 95 wt.% strontium fluoroaluminosilicate glass, 5 wt.% polyacrylic acid Liquid: 40 wt.% aqueous polyacrylic acid EQUIA Forte Coat: 40–50 wt.% methyl methacrylate, 10–15 wt.% colloidal silica, 0.09 wt.% camphorquinone, 30–40 wt.% urethane methacrylate, 1–5 wt.% phosphoric ester monomer | GC, Tokyo, Japan | 2307251 |

| Activa BioActive Restorative (AB) | Bio-interactive Restorative Material | Blend of diurethane and other methacrylates with modified polyacrylic acid (44.6 wt.%), amorphous silica (6.7 wt.%), sodium fluoride (0.75 wt.%); approximately 56 wt.% reactive glass particles in a patented rubberized resin matrix | Pulpdent, Watertown, MA, USA | 210324 |

| Cention-N (CN) | Dual cure bulk-fill composite | Liquid: Dimethacrylates, initiators, stabilizers, additives, flavoring agents Powder: Calcium fluorosilicate glass, barium glass, calcium–barium–aluminum fluorosilicate glass, isofillers, ytterbium trifluoride, initiators, pigments; total inorganic filler content: 78.4 wt.% (particle size: 0.1–7 μm) | Ivoclar, Schaan, Liechtenstein | Z0233Y |

| Fuji II (F) | Resin-modified glass ionomer cement | Liquid: Polyacrylic acid Powder: Al2O3–SiO2–CaF2 glass and HEMA urethane dimethacrylate | GC; Tokyo, Japan | 2302133 |

| Solare-X (SX) | Composite Resin (Nanofilled) | UDMA-based dimethacrylate resin matrix; silica nanoparticles, fluoroaluminosilicate glass fillers, and prepolymerized fillers; total inorganic filler content: 77 wt.% (mean particle size: 0.85 nm) | GC, Tokyo, Japan | 1902071 |

| Cement/Material Interface | Enamel/Material Interface | Material Surface | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial | Final | Initial | Final | Initial | Final | |

| Mean (sd) | Mean (sd) | Mean (sd) | Mean (sd) | Mean (sd) | Mean (sd) | |

| Activa BioActive Restorative (AB) | 3.87 (1.61) Ab | 5.92 (2.29) Aa | 3.69 (1.58) Abc | 5.09 (1.98) Bb | 1.36 (0.52) Aa | 1.74 (0.89) Ba |

| Cention-N (CN) | 4.08 (1.99) Aab | 6.15 (2.38) Bbc | 4.17 (1.53) Ac | 6.12 (2.47) Bb | 2.98 (1.79) Ab | 3.6 (1.78) Bb |

| Equia Forte (EF) | 5.07 (2) Ac | 7.45 (2.05) Bc | 3.97 (2.04) Ac | 6.04 (1.97) Bb | 3.26 (1.81) Ab | 4.09 (2.07) Bb |

| Fuji II LC (F) | 3.11 (1.69) Ab | 4.34 (2.56) Bab | 2.95 (0.64) Ab | 3.81 (0.92) Ba | 1.47 (0.61) Aa | 1.84 (0.67) Ba |

| Solare-X (SX) | 1.96 (1.13) Aa | 3.68 (1.98) Ba | 1.71 (0.91) Aa | 2.63 (1.61) Ba | 0.83 (0.29) Aa | 1.02 (0.42) Ba |

| Material | Cement/Material Interface | Enamel/Material Interface | Material Surface |

|---|---|---|---|

| Activa BioActive Restorative | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.010 |

| Cention-N | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Equia Forte | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.018 |

| Fuji II LC | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Solare-X | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.007 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Güner, Z.; Keçeci, G.; Olguner, S.; Çandar, H.; Güngör Borsöken, A.; Turkun, L.S. Thermal Aging-Induced Alterations in Surface and Interface Topography of Bio-Interactive Dental Restorative Materials Assessed by 3D Non-Contact Profilometry. Coatings 2026, 16, 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16010053

Güner Z, Keçeci G, Olguner S, Çandar H, Güngör Borsöken A, Turkun LS. Thermal Aging-Induced Alterations in Surface and Interface Topography of Bio-Interactive Dental Restorative Materials Assessed by 3D Non-Contact Profilometry. Coatings. 2026; 16(1):53. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16010053

Chicago/Turabian StyleGüner, Zehra, Gökçe Keçeci, Sadık Olguner, Hakan Çandar, Ayşenur Güngör Borsöken, and Lezize Sebnem Turkun. 2026. "Thermal Aging-Induced Alterations in Surface and Interface Topography of Bio-Interactive Dental Restorative Materials Assessed by 3D Non-Contact Profilometry" Coatings 16, no. 1: 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16010053

APA StyleGüner, Z., Keçeci, G., Olguner, S., Çandar, H., Güngör Borsöken, A., & Turkun, L. S. (2026). Thermal Aging-Induced Alterations in Surface and Interface Topography of Bio-Interactive Dental Restorative Materials Assessed by 3D Non-Contact Profilometry. Coatings, 16(1), 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16010053