SnSe: A Versatile Material for Thermoelectric and Optoelectronic Applications

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials Foundations of SnSe and Methods for Single-Crystal, Polycrystal, and Thin-Film Growth

2.1. Crystal-Band-Phonon: The Key Physical Framework of SnSe

2.1.1. Orthogonal Phase and Layered Structure: Pnma/Cmcm and Anisotropy

2.1.2. Energy Valley and Bandgap Control: Electronic Structure from Bulk Phase to Low-Dimensional State

| Year | Morphology | Direct Bandgap | Indirect Bandgap | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2007 | Polycrystalline thin film | 1.15 | 0.95 | [79] |

| 2013 | Nanoflowers | 1.05 | 0.95 | [80] |

| 2013 | Nanosheets | 1.10 | 0.86 | [80] |

| 2014 | Nanowires | 1.03 | 0.92 | [81] |

| 2015 | Single layer | 1.66 | 1.63 | [68] |

| 2015 | Double layer | 1.62 | 1.47 | [68] |

| 2020 | Bulk | 1.3 | 0.9 | [42] |

| 2021 | Nanoplates | 0.96 | 0.9 | [82] |

| 2021 | Nanosheets | 1.07 | 0.9 | [83] |

| 2023 | Nanosheets | n.a. | 0.95 ± 0.05 | [84] |

| 2025 | Nanosheets | 1.35 | 1 | [85] |

2.2. From Single Crystals to Thin Films: Controlled Preparation and Process Window

2.2.1. Single Crystal Growth: Optimization of Bridgeman Method/Dose and Temperature Gradient

2.2.2. Polycrystalline Densification: Grain Boundary Engineering in SPS/HP Process

- Transient mechanisms in high-speed heating and cooling processes need to be studied in depth;

- The effects of the electric field on mass transfer, microstructure evolution, formability, and final performance during synthesis are unclear;

- The techniques for analyzing the actual behavior of materials using finite element calculations and improving the flexibility of sample size and geometry are still not mature enough.

- When the amount of reactants is 5 mmol → light gray rod-like crystals (length 0.8–1.5 cm, radius 60–100 µm) are formed;

- When the reactant dosage is 3.3 mmol → plate single crystals (size 1200 µm × 300 µm × 10 µm) are formed.

| Year | Morphology | Precursors | Other Reagents | Thickness | Temperature | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2010 | Powders | Se powder, KBH4, SnCl2 | Dl Water | ND | 0 °C | [111] |

| 2011 | Nanosheets | TOP-Se, SnCl2 | HMDS, OLA | 10–40 nm | 240 °C | [112] |

| 2011 | QDs | SnCl2·2H2O, Na2SeSO3 | HMDS, IPA, Water | 4 nm | RT | [113] |

| 2015 | QDs | Stannous octoate, NaHSe | Toluene, glycerol | 2.5 nm | 95 °C | [114] |

| 2015 | Nanosheets | SnCl2·2H2O, Na2SeSO3 | BSA, HCl, Water | 100–150 nm | RT | [115] |

| 2015 | Nanoparticles | SnCl2·2H2O, Se powder | NaOH, Water | 35 µm | RT | [116] |

| 2019 | Nanoflakes | SnCl2·2H2O, TOP-Se | PD, TGA | 1.3 µm | 180 °C | [117] |

| 2019 | Nanoparticles | SnCl2·2H2O, Na2SeSO3 | NH3, Water | ND | 50 °C | [118] |

| 2016 | Nanosheets | SnCl4·5H2O, SeO2 | OLA | 2 µm | 110 °C | [119] |

| 2020 | Nanosheets | SnCl2, SeO2 | TOP, OA, OLA | 90 ± 20 nm | RT | [120] |

| 2020 | Nanosheets | SnCl2·2H2O, NaBH4 | NaOH, DI Water | 80–500 nm | 130 °C | [121] |

| 2023 | Nanosheets | SnCl2, Se | KOH, N2H4 | ND | 180 °C | [122] |

| 2023 | Nanoplates | SnCl2·2H2O, InCl3·4H2O | Dl Water | 50–100 nm | 130 °C | [123] |

| 2025 | Nanorods | SnCl2·2H2O, Se powder | EG, HCl, NaOH | 100–400 nm | 200 °C | [124] |

- Reaction environment: In a closed system of high temperature and high pressure above the boiling point of the solvent, high-quality crystals are obtained by enhancing the crystallization driving force;

- Product diversity: Quantum dots, nanowires and two-dimensional nanosheets with different stoichiometric ratios and crystal structures have been successfully synthesized;

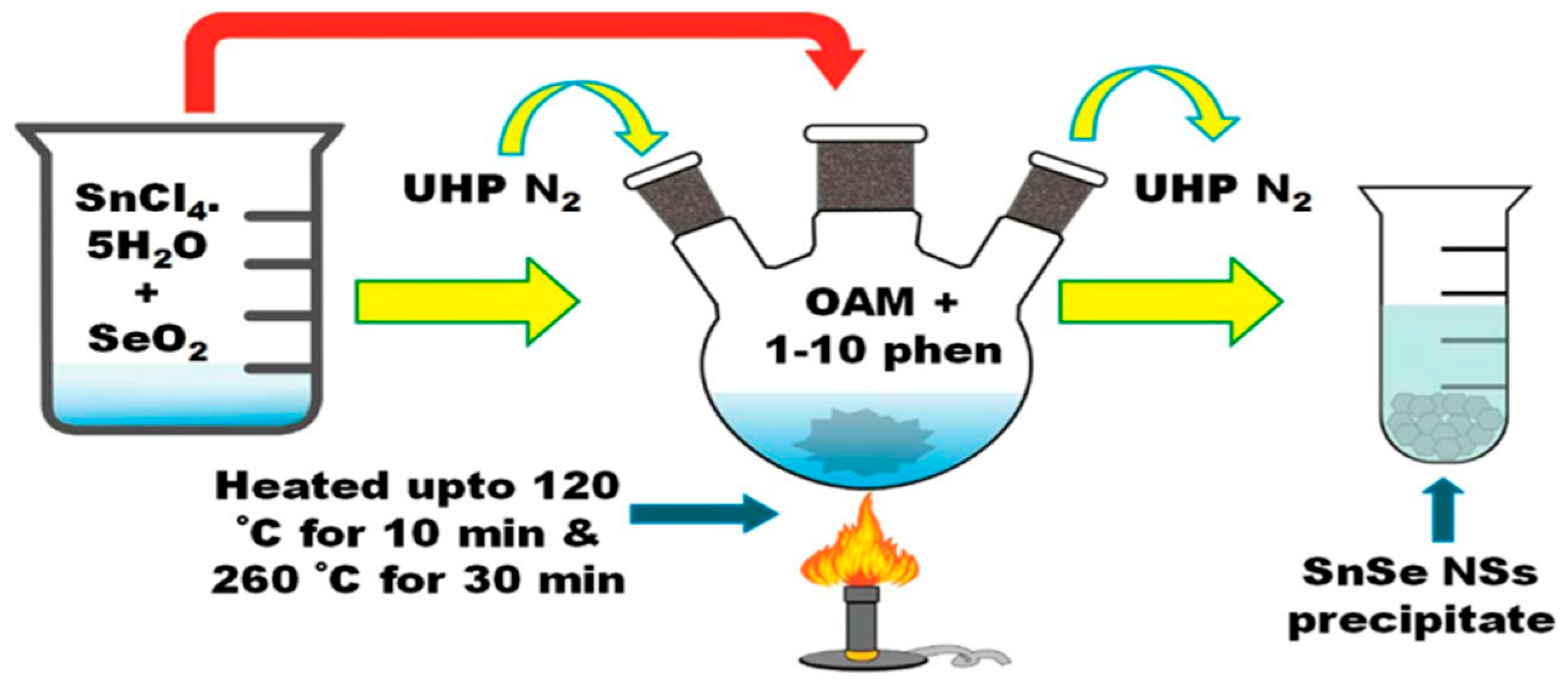

- Preparation characteristics: The reaction is usually carried out in an alkaline aqueous solution (the source material and solvent properties are similar to those of the solution method/thermal injection method, see Table 4, preparation process as shown in Figure 6). Precursors are mixed at room temperature and pressure and then transferred to a stainless steel autoclave for heating reaction [125].

| Year | Morphology | Precursors | Other Reagents | Thickness | Temperature | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | Nanorods | Stannous octoate, NaHSe | Toluene, glycerol | 100–400 nm | 180 °C | [127] |

| 2016 | Nanorods | SnCl2·2H2O, SeO2 | OLA | 100 nm | 180 °C | [128] |

| 2016 | Nanoparticles | SeSO2, SnCl2 | NaOH, Water | 150 nm | 200 °C | [129] |

| 2017 | Powders | Se powder, SnCl2 | DI water, NaOH | 90 nm | 100 °C | [130] |

| 2017 | Nanoflakes | SnCl2·2H2O, SeO2 | EG, NaOH, Ethanol | 70 nm | 180 °C | [131] |

| 2018 | Powders | Se powder, SnCl2·2H2O | CuCl, DI water, NaOH | ND | 130 °C | [132] |

| 2019 | Nanosheets | Se powder, SnCl2·2H2O | NaOH, DI water | 150 nm | 180 °C | [133] |

| 2019 | Nanoplates | Se powder, SnCl2·2H2O | Gel4, NaOH, DI water | 7–14 nm | 130 °C | [134] |

| 2020 | Powders | Se powder, SnCl2·2H2O | NaBH4, NaCl, DI water | 70 nm | 200 °C | [135] |

| 2020 | QDs | Se powder, SnCl2·2H2O | EG, Graphene | 2 nm | 180 °C | [136] |

| 2022 | Nanosheets | SeO2 | EG, NaOH | 50 nm | 170 °C | [137] |

| 2023 | Nanosheets | SnCl2, Se powder | KOH, N2H4, DI water | ND | 170 °C | [138] |

| 2024 | Nanoparticles | Se powder, SnCl2·2H2O | NaBH4 | ND | 150 °C | [139] |

| 2025 | Nanosheets | Se powder, SnCl2·2H2O, NaOH, RbCl | DI water, EtOH | ND | 130 °C | [140] |

- Phased synthesis: Inject di-tert-butylselenide into a 95 °C mixed solution (containing anhydrous SnCl2, 2.50 mL dodecylamine, 0.50 mL dodecylthiol) to form a dark brown solid. The stoichiometric ratio formed SnSe phase, and double the dosage produced SnSe2 phase [73].

- Preparation of colloidal nanosheets: The TOP-Se precursor was injected into a mixed SnCl2 solution at 230 °C (solvent: oleamine/oleic acid/dodecylamine, nitrogen protected), and the reaction was maintained at 225 °C for 5 min [144].

- Toxicity improvement process: Using oleic acid instead of toxic TOP-Se yields SnSe nanocrystals with an average diameter of 7.5 nm;

| Year | Morphology | Precursors | Other Reagents | Thickness | Temperature | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2010 | QDs | TOP-Se | OLA, Oleic acid | 4–10 nm | 65–175 °C | [111] |

| 2012 | Nanoparticles | TOP-Se, SnCl2 | OA, OLA, TAA, ODE | ND | 100 °C | [147] |

| 2014 | Nanoparticles | OA-Se, SnCl2 | OLA, ODE | 7.5–9.2 nm | 150–170 °C | [144] |

| 2014 | Nanosheets | TOP-Se, SnCl2 | OA, OLA, ODE | 25–30 nm | 218 °C | [144] |

| 2014 | Nanoplates | OAm-Se, SnCl2 | OA, DAM | 7.2 nm | 146 °C | [144] |

| 2014 | Nanorods | SnCl2·2H2O, SeO2 | OA, OLA, DDT | 14 nm | 175 °C | [148] |

| 2019 | Nanosheets | TOP-Se, SnCl2 | OLA, HMDS | 20 nm | 240 °C | [143] |

| 2020 | Nanosheets | Se, SnCl2 | OA, OLA, ODE, DDT | 11 ± 1.5 nm | 180 °C | [145] |

| 2024 | Nanosheets | Se-TOP | OLA | 49.6 ± 17.7 nm | 240 °C | [149] |

| 2024 | Nanosheets | SeO, Se | OLA, ODE | 14.8 µm | 230 °C | [150] |

| 2024 | Nanoflowers | Se, SnCl2·2H2O | OA, OLA, IPA | 30 nm | 250 °C | [151] |

| 2025 | Nanosheets | Se, SnCl2 | OLA, TOP, HMDS | 5–10 nm | 240 °C | [152] |

2.2.3. Film Manufacturing: Comparison and Selection of PVD/CVD/Solution Methods

- Developing novel precursors and reaction pathways to suppress selenium volatilization;

- Optimizing the CVD/MBE process for large-area two-dimensional SnSe single crystal growth;

- Exploring the synergy of PVD-CVD Hybrid technology with low-temperature accuracy and three-dimensional coverage capability.

3. Towards High ZT Values: Carrier-Sound Interaction Design in SnSe

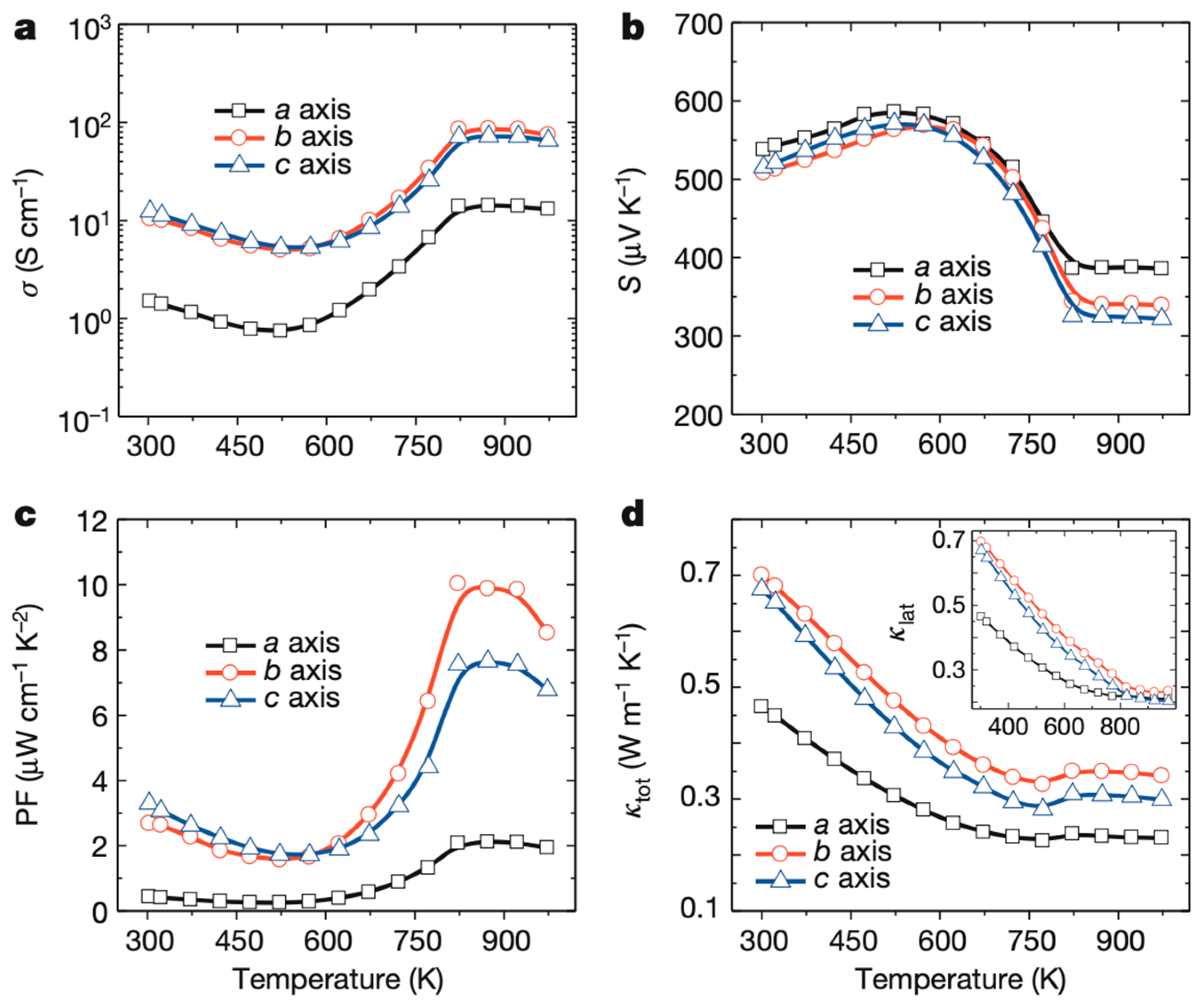

3.1. Intrinsic Performance and Temperature Zone Compatibility: Baseline of Anisotropic ZT

- 300–525 K: Shows metalloid transport behavior, that is, S increases with temperature and σ decreases. The thermal conductivity κ shows a decreasing trend. The parameter mutation at 525 K results from the thermal excitation of carriers;

- 525–800 K: Shows thermally activated semiconductor behavior, where S decreases with temperature and σ increases. κ continues to decline in this range;

- >800 K: All parameters tend to stabilize, which is likely related to the material changing from the Pnma space group phase to the Cmcm space group.

3.2. Carrier and Phonon Dual Regulation: Strategies and Effects of Chemical Doping

3.2.1. Ag/Na Co-Operative P-Type Regulation and Power Factor Improvement

3.2.2. Zn Defect Tuning: Trade-Off Between Carrier Concentration and Lattice Thermal Conductivity

3.2.3. Cu-Induced Band Engineering and Mobility Optimization

3.2.4. Anion Site Regulation: S Substitution Amplifies Phonon Scattering

| Year | Dopant | Type | ZT | T/℃ | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2009 | Undoped | Single crystal | 2.60 | 650 | [22] |

| 2011 | Cu | p-type | 0.70 | 500 | [200] |

| 2014 | Undoped | p-type | 0.50 | 550 | [191] |

| 2016 | Na | Single crystal | 2.00 | 500 | [196] |

| 2016 | Na | p-type | 0.80 | 500 | [201] |

| 2016 | Bi | Single crystal | 2.20 | 500 | [202] |

| 2016 | Tl | n-type | 0.60 | 500 | [203] |

| 2017 | Ag | Single crystal | 0.95 | 520 | [204] |

| 2017 | Ag | p-type | 1.30 | 500 | [205] |

| 2017 | Zn | p-type | 0.96 | 600 | [206] |

| 2024 | Ga | p-type | 2.2 | 600 | [207] |

| 2024 | Bi, Te | n-type | 0.055 | 400 | [208] |

| 2024 | Na | p-type | 2.0 | 500 | [209] |

| 2025 | Ag, Ga | p-type | 1.2 | 550 | [210] |

3.3. Comparative Dopant Effects on Carrier Transport and Stability

4. The Light-Matter Interaction in Tin Selenide: Absorption, Lifetime and Response

4.1. Optical Constants and Carrier Dynamics: Absorption, Lifetime and Responsivity

4.2. Performance Optimization Path: Support for Alignment and Interface Engineering

4.2.1. Doping Tuning: Trap State Management and Dark Current Suppression

4.2.2. Heterojunction Design: Band Alignment/Built-In Field and Selective Contact

5. Application Fields: Photovoltaic Technology, Thermoelectric Technology, and Potential Areas

5.1. Thin-Film Solar Cells: Junction Structure, Defect Passivation, and Efficiency Progress

- Bulk and interface defects: Deep-level defects and secondary phases (e.g., SnSe2) act as recombination centers, severely reducing carrier lifetime. This is the most critical issue, as confirmed by SCAPS-1D simulations showing that defect densities above 1016 cm−3 drastically reduce VOC and FF;

- Poor back contact and band alignment: Mismatched work functions and high interfacial recombination at the SnSe/back-contact and SnSe/buffer-layer interfaces limit VOC and JSC. Achieving ohmic contacts and proper band alignment is essential;

- Low carrier mobility and conductivity: Although SnSe exhibits high intrinsic mobility, grain boundaries and point defects in polycrystalline films reduce effective mobility, lowering FF and JSC;

- Optical and thermal losses: Parasitic absorption, reflection, and thermalization losses further cap efficiency, but these are secondary to electronic losses.

5.2. Device-Level Considerations: Average ZT, Cycle Stability, and Packaging Thermal Management

- Miniature devices: Biochip laboratory cooling, microelectronic heat dissipation (with significant advantages of small size and no mechanical parts);

- Industrial transportation: Car engine cooling, in-car air conditioning systems, and precise temperature control for lasers and chemical reactors;

- Aerospace temperature control: Cooling satellite infrared detectors to enhance detection accuracy. Balance current density with Joule heat loss and optimize film thickness to balance mechanical strength with thermal resistance control.

5.3. Cross-Border Expansion: Storage, Energy Storage, and Electrochemical Scenarios

5.3.1. Phase-Change Random Access Memory (PCRAM): Phase Change Dynamics and Durability

5.3.2. Supercapacitor: Pseudo Capacitance/EDL Control–Superior Capacitance and Rate Capability

5.3.3. Rechargeable Batteries: Layering and Conversion Mechanisms and Cycle Life

6. Conclusions and Outlook

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chu, S.; Majumdar, A. Opportunities and challenges for a sustainable energy future. Nature 2012, 488, 294–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larcher, D.; Tarascon, J.M. Towards greener and more sustainable batteries for electrical energy storage. Nat. Chem. 2015, 7, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Cheng, X.; Zhang, Q. Nanostructured energy materials for electrochemical energy conversion and storage: A review. J. Energy Chem. 2016, 25, 967–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhu, Q.L.; Zou, R.; Xu, Q. Metal-organic frameworks for energy applications. Chem 2017, 2, 52–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.; Kong, L.; Li, T.; Zhang, Q. A review of transition metal chalcogenide/graphene nanocomposites for energy storage and conversion. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2017, 28, 2180–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mochalov, L.; Kudryashov, M.; Logunov, A.; Zelentsov, S.; Nezhdanov, A.; Mashin, A.; Gogova, D.; Chidichimo, G.; De Filpo, G. Structural and optical properties of arsenic sulfide films synthesized by a novel PECVD-based approach. Superlattices Microstruct. 2017, 111, 1104–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mochalov, L.; Nezhdanov, A.; Strikovskiy, A.; Gushin, M.; Chidichimo, G.; De Filpo, G.; Mashin, A. Synthesis and properties of AsxTe100−x films prepared by plasma deposition via elemental As and Te. Opt. Quantum Electron. 2017, 49, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antunez, P.D.; Buckley, J.J.; Brutchey, R.L. Tin and germanium monochalcogenide IV–VI semiconductor nanocrystals for use in solar cells. Nanoscale 2011, 3, 2399–2411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrikosov, N.K.; Bankina, V.F.; Poretskaya, L.V.; Shelimova, L.E.; Skudnova, E.V. Semiconducting IV–VI, and V–VI Compounds; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, R.C.; Chang, Y.A. The Se−Sn (selenium-tin) system. Bull. Alloy Phase Diagr. 1986, 7, 68–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feutelais, Y.; Majid, M.; Legendre, B.; Frics, S.G. Phase diagram investigation and proposition of a thermodynamic evaluation of the tin-selenium system. J. Phase Equilibria 1996, 17, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bletskan, D.I. Phase equilibrium in binary systems AIVBVI. J. Ovonic Res 2005, 1, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pałosz, B.; Gierlotka, S.; Levy, F. Polytypism of SnSe2 crystals grown by chemical transport: Structures of six large-period polytypes of SnSe2. Cryst. Struct. Commun. 1985, 41, 1404–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pałosz, B.; Salje, E. Lattice parameters and spontaneous strain in AX2 polytypes: CdI2, PbI2 SnS2 and SnSe2. Appl. Crystallogr. 1989, 22, 622–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Kumar, P.; Yadav, S.; Kumar, V.; Bansal, M.K.; Dwivedi, D.K. Growth and characterization of tin selenide films synthesized by low cost technique for photovoltaic device applications. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2016, 27, 4043–4049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.; Gao, M.; Wei, J.; Gao, J.; Fan, C.; Ashalley, E.; Li, H.; Wang, Z. Tin selenide (SnSe): Growth, properties, and applications. Adv. Sci. 2018, 5, 1700602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Chen, X.; Li, M.; Du, A. Widely tunable and anisotropic charge carrier mobility in monolayer tin (II) selenide using biaxial strain: A first-principles study. J. Mater. Chem. C 2017, 5, 1247–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pejova, B.; Grozdanov, I. Chemical synthesis, structural and optical properties of quantum sized semiconducting tin (II) selenide in thin film form. Thin Solid Films 2007, 515, 5203–5211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Guo, X.; Li, M.; Zhang, W.H.; Liu, X.; Li, C. Solution-phase synthesis and characterization of single-crystalline SnSe nanowires. Angew. Chem.-Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 12050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, M.R.; Liu, T.; McGettrick, J.; Mehraban, S.; Baker, J.; Pockett, A.; Watson, T.; Fenwick, O.; Carnie, M.J. Thin film tin selenide (SnSe) thermoelectric generators exhibiting ultralow thermal conductivity. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, 1801357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.D.; Chang, C.; Tan, G.; Kanatzidis, M.G. SnSe: A remarkable new thermoelectric material. Energy Environ. Sci. 2016, 9, 3044–3060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.D.; Lo, S.H.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, H.; Tan, G.; Uher, C.; Wolverton, C.; Dravid, V.P.; Kanatzidis, M.G. Ultralow thermal conductivity and high thermoelectric figure of merit in SnSe crystals. Nature 2014, 508, 373–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makinistian, L.; Albanesi, E.A. On the band gap location and core spectra of orthorhombic IV–VI compounds SnS and SnSe. Phys. Status Solidi B 2009, 246, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minnam Reddy, V.R.; Gedi, S.; Pejjai, B.; Park, C. Perspectives on SnSe-based thin film solar cells: A comprehensive review. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2016, 27, 5491–5508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Guo, Y.; Zhao, F.; Nie, C.; Li, H.; Shi, J.; Liu, X.; Jiang, J.; Zuo, S. Effect of film thickness and evaporation rate on co-evaporated SnSe thin films for photovoltaic applications. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 16749–16755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guillen, C.; Montero, J.; Herrero, J. Characteristics of SnSe and SnSe2 thin films grown onto polycrystalline SnO2-coated glass substrates. Phys. Status Solidi A 2011, 208, 679–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loferski, J.J. Theoretical considerations governing the choice of the optimum semiconductor for photovoltaic solar energy conversion. J. Appl. Phys. 1956, 27, 777–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shockley, W.; Queisser, H.J. Detailed Balance Limit of Efficiency of p-n Junction Solar Cells. J. Appl. Phys. 1961, 32, 510–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturge, M. Optical absorption of gallium arsenide between 0.6 and 2.75 eV. Phys. Rev. 1962, 127, 768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aspnes, D.E.; Studna, A.A. Dielectric functions and optical parameters of si, ge, gap, gaas, gasb, inp, inas, and insb from 1.5 to 6.0 ev. Phys. Rev. B 1983, 27, 985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, F.W.; Lai, C.W. Recent developments of graphene-TiO2 composite nanomaterials as efficient photoelectrodes in dye-sensitized solar cells: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 82, 103–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irshad Ahamed, M.; Ayyappa, R.; Edward Anand, E.; Krishnamoorthy, R. Investigation of thermally evaporated SnSe nano structure layer for photovoltaic use: A structural, morphological, and electrical analysis. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2025, 36, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallavolu, M.R.; Vishwanath, S.K.; Joo, S.W. Development of indium (In) doped SnSe thin films for photovoltaic application. Mater. Lett. 2020, 281, 128714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Insawang, M.; Ruamruk, S.; Vora-ud, A.; Singsoog, K.; Inthachai, S.; Chaarmart, K.; Boonkirdram, S.; Horprathum, M.; Muntini, M.S.; Park, S.; et al. Investigation on thermoelectric properties of SnSe thin films as prepared by RF magnetron sputtering. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 2024, 222, 111789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faridah, N.; Vora-Ud, A.; Insawang, M.; Muntini, M.S. Investigation on Flexible Thin Film Thermoelectrics of Tin Selenide prepared by RF Magnetron Sputtering. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2024, 3034, 012009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.; Xie, H.; Gao, D.; Bai, S.; Shi, J.; Fu, P.; Zhao, L.-D.; Li, C. Controlled doping and growth of SnSe thin films via pulsed laser deposition. J. Mater. 2025, 11, 101121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotrla, M.; Segawa, H.; Ohsawa, T.; Matsushita, Y.; Janíček, P.; Gutwirth, J.; Nazabal, V.; Drašar, Č.; Němec, P. Phase-change Sn-Se thin films prepared via pulsed laser deposition. Ceram. Int. 2025, 51, 3109–3114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onn, T.M.; Kungas, R.; Fornasiero, P.; Huang, K.; Gorte, R.J. Atomic Layer Deposition on Porous Materials: Problems with Conventional Approaches to Catalyst and Fuel Cell Electrode Preparation. Inorganics 2018, 6, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, P.; Stickney, J.L. Photoelectrochemical Analysis of Tin Selenide (SnSex) Thin Films Formed Using Electrochemical Atomic Layer Deposition (E-ALD). Electrochem. Soc. Meet. Abstr. 2018, 233, 2099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, P.; Stickney, J.L. Electrochemical Deposition of Tin Selenide (SnSex) Thin Films. Electrochem. Soc. Meet. Abstr. 2017, 231, 1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahandal, S.S.; Sanap, P.S.; Patil, V.V.; Kim, H.; Piao, G.; Khalate, S.A.; Said, Z.; Patil, U.M.; Pawar, A.C.; Pagar, B.P.; et al. Electrochemically synthesized tin selenide thin films as efficient electrocatalyst for overall water splitting. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 61, 710–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalalian-Larki, B.; Jamali-Sheini, F.; Yousefi, R. Electrodeposition of In-doped SnSe nanoparticles films: Correlation of physical characteristics with solar cell performance. Solid State Sci. 2020, 108, 106388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamali-Sheini, F.; Cheraghizade, M.; Yousefi, R. Electrochemically synthesis and optoelectronic properties of Pb-and Zn-doped nanostructured SnSe films. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018, 443, 345–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karasi, A.A.E.M.; Seshadri, S.; Amalraj, L.; Sambasivam, R. Influence of Substrate Temperature on Physical Properties of Nebulized Spray Deposited SnSe Thin Films. ECS J. Solid State Sci. Technol. 2021, 10, 084008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.L.; Tao, X.; Zou, J.; Chen, Z.G. High-performance thermoelectric SnSe: Aqueous synthesis, innovations, and challenges. Adv. Sci. 2020, 7, 1902923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, P.; Ghorui, U.K.; Mondal, A.; Banerjee, D. Photoelectrochemical Performance of Tin Selenide (SnSe) Thin Films Prepared by Two Different Techniques. Electron. Mater. Lett. 2022, 18, 381–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Wang, Y.; Gong, Q.; Li, L.; Wu, X. An intelligent temperature control algorithm of molecular beam epitaxy system based on the back-propagation neural network. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 9848–9855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razykov, T.M.; Kuchkarov, K.M.; Tivanov, M.S.; Bayko, D.S.; Kaputskaya, I.A.; Poliak, N.I.; Korolik, O.V.; Ergashev, B.A.; Yuldoshov, R.T.; Khurramov, R.R.; et al. Surface Morphology and Phase Composition of (Zn,Sn) Se Thin Films, Obtained by Chemical-Molecular Beam Deposition. Appl. Sol. Energy 2021, 57, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Yang, F.; Li, Q.; Ruan, S.; Xiang, B. A waveguide-integrated SnSe photodetector on a lithium niobate thin film with high responsivity, fast response, and self-powered capability. J. Mater. Chem. C 2025, 13, 21196–21204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horide, T.; Murakami, Y.; Hirayama, Y.; Ishimaru, M.; Matsumoto, K. Thermoelectric property in orthorhombic-domained SnSe film. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 27057–27063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, S.; Dutta, P.; Biswas, K. High-performance thermoelectrics based on solution-grown SnSe nanostructures. ACS Nano 2021, 16, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Calcabrini, M.; Yu, Y.; Genç, A.; Chang, C.; Costanzo, T.; Kleinhanns, T.; Lee, S.; Llorca, J.; Cojocaru-Mirédin, O.; et al. The importance of surface adsorbates in solution-processed thermoelectric materials: The case of SnSe. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, 2106858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Zhu, J.; Xu, Y.; Zhou, L.; Li, Y.; Hu, L.; Yao, J.; Dai, S. SnX (X = S, Se) thin films as cost-effective and highly efficient counter electrodes for dye-sensitized solar cells. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 8108–8111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, V.R.M.; Lindwall, G.; Pejjai, B.; Gedi, S.; Kotte, T.R.R.; Sugiyama, M.; Liu, Z.K.; Park, C. α-SnSe thin film solar cells produced by selenization of magnetron sputtered tin precursors. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2018, 176, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, L.; Du, Y.; Wang, Z.; Wu, Y.; Xu, H.; Dong, S.; Liu, H.; Liu, Y.; Xue, Q.; Han, Z.; et al. Wafer-size growth of 2D layered SnSe films for UV-visible-NIR photodetector arrays with high responsitivity. Nanoscale 2020, 12, 7358–7365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, N.; Yun, B.; Song, J.; Jung, S.; Maulana, A.Y.; Seo, H.A.; Ju, H.; Kim, J. SnSe encapsulated in N-doped graphitic carbon prepared by exchange methods for a high-performance anode in potassium-ion batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A 2025, 13, 32706–32715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; Zhu, Y.H.; Li, W.; Wang, S.; Xu, D.; Li, L.; Zhang, X.B. Surfactant-free aqueous synthesis of pure single-crystalline SnSe nanosheet clusters as anode for high energy-and power-density sodium-ion batteries. Adv. Mater 2017, 29, 1602469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liu, Y.; Dai, J.; Chen, Q.; Huang, X.; Huang, W. Solution-processed p-SnSe/n-SnSe2 hetero-structure layers for ultrasensitive NO2 detection. Chem. A Eur. J. 2020, 26, 3870–3876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assili, K.; Gonzalez, O.; Alouani, K.; Vilanova, X. Structural, morphological, optical and sensing properties of SnSe and SnSe2 thin films as a gas sensing material. Arab. J. Chem. 2020, 13, 1229–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandit, B.; Jadhav, C.D.; Chavan, P.G.; Tarkas, H.S.; Sali, J.V.; Gupta, R.B.; Sankapal, B.R. Two-dimensional hexagonal SnSe nanosheets as binder-free electrode material for high-performance supercapacitors. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2020, 35, 11344–11351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, D.; Bagga, V.; Behera, N.; Thakral, B.; Asija, A.; Kaur, J.; Kaur, S. SnSe/SnO2 nanocomposites: Novel material for photocatalytic degradation of industrial waste dyes. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 2019, 2, 763–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Sun, L.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, L.; Yu, D.; Wang, Y.; Yu, M. SnSe@SnO2 core–shell nanocomposite for synchronous photothermal–photocatalytic production of clean water. Environ. Sci. Nano 2019, 6, 1507–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Zhong, Z.; Shirakawa, T.; Franchini, C.; Li, D.; Li, Y.; Chen, X.Q. Rocksalt SnS and SnSe: Native topological crystalline insulators. Phys. Rev. B 2013, 88, 235122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Li, F.; Xu, Y.; Duan, M.; Song, Y.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, H. Tin selenide: A promising black-phosphorus-analogue nonlinear optical material and its application as all-optical switcher and all-optical logic gate. Mater. Today Phys. 2021, 21, 100500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abutbul, R.E.; Segev, E.; Argaman, U.; Makov, G.; Golan, Y. π-Phase tin and germanium monochalcogenide semiconductors: An emerging materials system. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, 1706285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Liu, Y.; Wu, M.; Zhao, L.D.; Lin, Z.; Cheng, H.C.; Duan, X. Highly-anisotropic optical and electrical properties in layered SnSe. Nano Res. 2018, 11, 554–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, A.; Watson, G.W. Influence of the anion on lone pair formation in Sn (II) monochalcogenides: A DFT study. J. Phys. Chem. B 2005, 109, 18868–18875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, G.; Kioupakis, E. Anisotropic spin transport and strong visible-light absorbance in few-layer SnSe and GeSe. Nano Lett. 2015, 15, 6926–6931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, X.; Lu, P.; Wu, L.; Han, L.; Liu, G.; Song, Y.; Wang, S. Thermoelectric properties of SnSe compound. J. Alloys Compd. 2015, 643, 116–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Neupane, G.P.; Jia, G.; Zhao, H.; Qi, D.; Du, Y.; Yin, Z. 2D materials based on main group element compounds: Phases, synthesis, characterization, and applications. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020, 30, 2001127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, Z.; Wang, K.; Ji, L.; Wan, J.; Luo, Q.; Wu, H.; Liu, C. SnSe ambipolar thin film transistor arrays with copper-assisted exfoliation. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2023, 617, 156517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Mare, S.; Menossi, D.; Salavei, A.; Artegiani, E.; Piccinelli, F.; Kumar, A.; Mariotto, G.; Romeo, A. SnS Thin Film Solar Cells: Perspectives and Limitations. Coatings 2017, 7, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzman, M.A.; Schlenker, C.W.; Thompson, M.E.; Brutchey, R.L. Solution-phase synthesis of SnSe nanocrystals for use in solar cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 4060–4061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, P.K.; Barrios-Salgado, E.; Nair, M.T.S. Cubic-structured tin selenide thin film as a novel solar cell absorber. Phys. Status Solidi A 2016, 213, 2229–2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrios-Salgado, E.; Rodríguez-Guadarrama, L.A.; Garcia-Angelmo, A.R.; Álvarez, J.C.; Nair, M.T.S.; Nair, P.K. Large cubic tin sulfide–tin selenide thin film stacks for energy conversion. Thin Solid Films 2016, 615, 415–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.; Tan, G.; He, J.; Kanatzidis, M.G.; Zhao, L.D. The thermoelectric properties of SnSe continue to surprise: Extraordinary electron and phonon transport. Chem. Mater. 2018, 30, 7355–7367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, R.; Wang, X.; Kuang, Y.; Huang, B. First-principles study of anisotropic thermoelectric transport properties of IV–VI semiconductor compounds SnSe and SnS. Phys. Rev. B 2015, 92, 115202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Li, W.; Wang, Y.; Yu, X.; Liu, J.; He, Q. Pressure-induced improvement in symmetry and change in electronic properties of SnSe. J. Mol. Model. 2017, 23, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, P.A.; Sousa, M.G.; Salome, P.M.; Leitão, J.P.; Da, C.A.F. Thermodynamic pathway for the formation of SnSe and SnSe2 polycrystalline thin films by selenization of metal precursors. CrystEngComm 2013, 15, 10278–10286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Chen, Z.; Hu, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhang, T.; Chen, W.; Wang, Q. Single-layer single-crystalline SnSe nanosheets. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 1213–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butt, F.K.; Mirza, M.; Cao, C.; Idrees, F.; Tahir, M.; Safdar, M.; Ali, Z.; Tanveer, M.; Aslam, I. Synthesis of mid-infrared SnSe nanowires and their optoelectronic properties. CrystEngComm 2014, 16, 3470–3473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, T.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Z.; Yuan, G.; Liang, Y.; Tan, J.; Ren, Y.; Lei, W. SnSe nanoplates for photodetectors with a high signal/noise ratio. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2021, 4, 13071–13078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 83; Mir, W.J.; Sharma, A.; Villalva, D.R.; Liu, J.; Haque, M.A.; Shikin, S.; Baran, D. The ultralow thermal conductivity and tunable thermoelectric properties of surfactant-free SnSe nanocrystals. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 28072–28080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakay, N.; Schlesinger, A.; Argaman, U.; Nguyen, L.; Maman, N.; Koren, B.; Ozeri, M.; Makov, G.; Golan, Y.; Azulay, D. Electrical and Optical Properties of γ-SnSe: A New Ultra-narrow Band Gap Material. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 15668–15675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Li, X.; Luo, S.; Luo, S.; He, Z.; Wu, X.; Qiao, H.; Fang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Qi, X.; et al. Enhancing photocatalytic performance by one-step vapor deposition of SnSe/SnSe2 composites. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2025, 8, 13831–13839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V.Q.; Kim, J.; Cho, S. A review of SnSe: Growth and thermoelectric properties. J. Korean Phys. Soc. 2018, 72, 841–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, H.; Onodera, K.; Ohba, H. Characterization of Cd1−xMnxTe crystals grown by the Bridgman method and the zone melt method. J. Cryst. Growth 2000, 214, 885–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Hua, Y.; Li, X.; Zhang, L.; Liu, L.; Li, R.; Tao, X. Filter-free color image sensor based on CsPbBr3−3nX3n (X = Cl, I) single crystals. J. Mater. Chem. C 2021, 9, 2840–2847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Zhang, G.; Liu, L.; Ju, D.; Zhang, L.; Cheng, K.; Tao, X. Anisotropic optoelectronic properties of melt-grown bulk CsPbBr3 single crystal. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2018, 9, 5040–5046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Wang, S.; Sheng, M.; Shao, B.; He, Y.; Liu, Z.; Zhou, G. Bridgman Method for Growing Metal Halide Single Crystals: A Review. Inorganics 2025, 13, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zayachuk, D.M.; Ilyina, O.S.; Pashuk, A.V.; Mikityuk, V.I.; Shlemkevych, V.V.; Csik, A.; Kaczorowski, D. Segregation of the Eu impurity as function of its concentration in the melt for growing of the lead telluride doped crystals by the Bridgman method. J. Cryst. Growth 2013, 376, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, J.; Zhang, J.; Wang, L.; Min, J.; Wu, W.; Shen, M.; Liang, W. Comparison of cadmium manganese telluride crystals grown by traveling heater method and vertical Bridgman method. Cryst. Res. Technol. 2015, 50, 817–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyubimova, T.P.; Croell, A.; Dold, P.; Khlybov, O.A.; Fayzrakhmanova, I.S. Time-dependent magnetic field influence on GaAs crystal growth by vertical Bridgman method. J. Cryst. Growth 2004, 266, 404–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, A.; Nishizawa, J.I.; Oyama, Y.; Suto, K. InP single crystal growth by the horizontal Bridgman method under controlled phosphorus vapor pressure. J. Cryst. Growth 2001, 229, 119–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Zhang, P.; Li, Z.; Chen, Z. Thermal Field Simulation and Optimization of PbF2 Single Crystal Growth by the Bridgman Method. Crystals 2024, 14, 473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Chen, X.; Zhao, T.; Chen, C.; Han, J.; Pan, S.; Pan, J. Growth and luminescence properties of γ-CuBr single crystals by the Bridgman method. CrystEngComm 2023, 25, 1669–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akasaka, M.; Iida, T.; Matsumoto, A.; Yamanaka, K.; Takanashi, Y.; Imai, T.; Hamada, N. The thermoelectric properties of bulk crystalline n-and p-type Mg2Si prepared by the vertical Bridgman method. J. Appl. Phys. 2008, 104, 013703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Lin, D.; Chen, Z.; Cheng, Z.; Wang, J.; Li, C.; Xu, Z.; Huang, Q.; Liao, X.; Chen, L.-Q.; et al. Ultrahigh piezoelectricity in ferroelectric ceramics by design. Nat. Mater. 2018, 17, 349–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, C.; Wang, B.; Zhang, N.; Zhang, S.; Liu, J.; Walker, D.; Wang, Y.; Tian, H.; Shrout, T.R.; Xu, Z.; et al. Transparent ferroelectric crystals with ultrahigh piezoelectricity. Nature 2020, 577, 350–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Liang, Z.; Luo, L.; Ke, Y.; Shen, Q.; Xia, Z.; Pan, J. Bridgman growth, crystallographic characterization and electrical properties of relaxor-based ferroelectric single crystal PIMNT. J. Alloys Compd. 2012, 518, 63–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokita, M. Progress of spark plasma sintering (SPS) method, systems, ceramics applications and industrialization. Ceramics 2021, 4, 160–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.H.; Liu, Z.F.; Lu, J.F.; Shen, X.B.; Wang, F.C.; Wang, Y.D. The sintering mechanism in spark plasma sintering–proof of the occurrence of spark discharge. Scr. Mater. 2014, 81, 56–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillon, O.; Gonzalez-Julian, J.; Dargatz, B.; Kessel, T.; Schierning, G.; Räthel, J.; Herrmann, M. Field-assisted sintering technology/spark plasma sintering: Mechanisms, materials, and technology developments. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2014, 16, 830–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diouf, S.; Molinari, A. Densification mechanisms in spark plasma sintering: Effect of particle size and pressure. Powder Technol. 2012, 221, 220–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Li, S.; An, L. A novel oscillatory pressure-assisted hot pressing for preparation of high-performance ceramics. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2014, 97, 1012–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rondiya, S.R.; Jadhav, C.D.; Chavan, P.G.; Dzade, N.Y. Enhanced field emission properties of Au/SnSe nano-heterostructure: A combined experimental and theoretical investigation. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 2358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Zheng, K.; Hong, M.; Liu, W.; Moshwan, R.; Wang, Y.; Qu, X.; Chen, Z.-G.; Zou, J. Boosting the thermoelectric performance of p-type heavily Cu-doped polycrystalline SnSe via inducing intensive crystal imperfections and defect phonon scattering. Chem. Sci. 2018, 9, 7376–7389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Wu, A.; Feng, T.; Zheng, K.; Liu, W.; Sun, Q.; Hong, M.; Pantelides, S.T.; Chen, Z.; Zou, J. High thermoelectric performance in p-type polycrystalline Cd-doped SnSe achieved by a combination of cation vacancies and localized lattice engineering. Adv. Energy Mater. 2019, 9, 1803242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Chen, Z.G.; Liu, W.; Yang, L.; Hong, M.; Moshwan, R.; Zou, J. Achieving high Figure of Merit in p-type polycrystalline Sn0.98Se via self-doping and anisotropy-strengthening. Energy Storage Mater. 2018, 10, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Xie, Y.; Huang, J.; Qian, Y. Solvothermal route to tin monoselenide bulk single crystal with different morphologies. Inorg. Chem. 2000, 39, 2061–2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgardner, W.J.; Choi, J.J.; Lim, Y.F.; Hanrath, T. SnSe nanocrystals: Synthesis, structure, optical properties, and surface chemistry. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 9519–9521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughn, D.D.; In, S.I.; Schaak, R.E. A precursor-limited nanoparticle coalescence pathway for tuning the thickness of laterally-uniform colloidal nanosheets: The case of SnSe. ACS Nano 2011, 5, 8852–8860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Peng, L.; Fang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Pan, D.; Wu, M. Synthesis of colloidal SnSe quantum dots by electron beam irradiation. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 2011, 80, 1333–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, L.; Zhang, Q.; Zhu, L.; Wang, C.F.; Chen, S. Interfacial synthesis of SnSe quantum dots for sensitized solar cells. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 2155–2158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, L.; Guleria, A.; Adhikari, S. Aqueous phase one-pot green synthesis of SnSe nanosheets in a protein matrix: Negligible cytotoxicity and room temperature emission in the visible region. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 61390–61397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; He, Q.; Yin, A.; Xu, Y.; Wang, C.; Ding, M.; Cheng, H.-C.; Papandrea, B.; Huang, Y.; Duan, X. Cosolvent approach for solution-processable electronic thin films. Acs Nano 2015, 9, 4398–4405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, S.; Bera, S.; Afzal, H.; Kaushik, V.; Patidar, M.M.; Venkatesh, R. Influence of sulphur doping in snse nanoflakes prepared by microwave assisted solvothermal synthesis. AIP Conf. Proc. 2019, 2100, 020108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, S.H.; Jo, S.; Kim, H.S.; Choi, G.; Song, J.Y.; Kang, J.Y.; Park, N.-J.; Ban, H.W.; Kim, F.; Jeong, H.; et al. Composition change-driven texturing and doping in solution-processed SnSe thermoelectric thin films. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Z.; Xiang, J.; Wen, F.; Yang, R.; Hao, C.; Liu, Z. Enhanced photoresponse of SnSe-nanocrystals-decorated WS2 monolayer phototransistor. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 4781–4788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Xing, C.; Zhang, T.; Li, M.; Pacios, M.; Yu, X.; Arbiol, J.; Llorca, J.; Cadavid, D.; et al. Tin selenide molecular precursor for the solution processing of thermoelectric materials and devices. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 27104–27111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, J.; Liu, X.; Niu, C.; Sun, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhang, B.; Wang, G.; Zhou, X.; Han, G. Facile microwave-assisted hydrothermal synthesis of SnSe: Impurity removal and enhanced thermoelectric properties. J. Mater. Chem. C 2020, 8, 10333–10341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzoor, S.; Alsaiari, N.S.; Katubi, K.M.; Nisa, M.U.; Abid, A.G.; Chughtai, A.H.; Abdullah, M.; Aman, S.; Al-Buriahi, M.S.; Ashiq, M.N. Facile fabrication of SnSe nanorods embedded in GO nanosheet for robust oxygen evolution reaction. J. Taibah Univ. Sci. 2023, 17, 2151298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Zhang, S.; Hou, Y.; Li, S.; Wang, C.; Xiong, W.; Zhang, Q.; Miao, X.; Liu, J.; Cao, Y.; et al. Enhanced density of states facilitates high thermoelectric performance in solution-grown Ge-and In-codoped SnSe nanoplates. ACS Nano 2022, 17, 801–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Xu, H.Y.; Li, B.; Qi, S.Y.; Jin, L.G.; Shan, L.W.; Dong, L.M. Critical Influence of Morphology Regulation on the Piezocatalytic Mechanism in SnSe. Langmuir 2025, 41, 18314–18324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.H.; Chen, I.C.; Cheng, H.C.; Yu, C.F. Influence of structural defect on thermal–mechanical properties of phosphorene sheets. J. Mater. Sci. 2017, 52, 3225–3232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, G.; Wen, Q.; Yang, T.; Cao, Y.; Wei, W.; Wang, Z.; Li, Y. Rock-salt-type nanoprecipitates lead to high thermoelectric performance in undoped polycrystalline SnSe. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 8258–8263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Z.H.; Wei, K.; Lewis, H.; Martin, J.; Nolas, G.S. Bottom-up processing and low temperature transport properties of polycrystalline SnSe. J. Solid State Chem. 2015, 225, 354–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawbake, A.S.; Jadkar, S.R.; Late, D.J. High performance humidity sensor and photodetector based on SnSe nanorods. Mater. Res. Express 2016, 3, 105038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, D.; Ge, Z.H.; Wu, D.; Chen, Y.X.; Wu, T.; Li, J.; He, J. Enhanced thermoelectric properties of SnSe polycrystals via texture control. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2016, 18, 31821–31827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, D.; Ge, Z.H.; Chen, Y.X.; Li, J.; He, J. Hydrothermal synthesis of SnQ (Q= Te, Se, S) and their thermoelectric properties. Nanotechnology 2017, 28, 455707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, H.; Park, D.; Kim, J. Hydrothermal transformation of SnSe crystal to Se nanorods in oxalic acid solution and the outstanding thermoelectric power factor of Se/SnSe composite. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 18051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, Y.; Chang, C.; Wei, W.; Liu, J.; Xiong, W.; Chai, S.; Li, D.; Zhang, J.; Tang, G. Extremely low thermal conductivity and enhanced thermoelectric performance of polycrystalline SnSe by Cu doping. Scr. Mater. 2018, 147, 74–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rongione, N.A.; Li, M.; Wu, H.; Nguyen, H.D.; Kang, J.S.; Ouyang, B.; Hu, Y. High-performance solution-processable flexible SnSe nanosheet films for lower grade waste heat recovery. Adv. Electron. Mater. 2019, 5, 1800774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, S.; Biswas, K. Realization of high thermoelectric figure of merit in solution synthesized 2D SnSe nanoplates via Ge alloying. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 6141–6145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.L.; Chen, W.Y.; Tao, X.; Zou, J.; Chen, Z.G. Rational structural design and manipulation advance SnSe thermoelectrics. Mater. Horiz. 2020, 7, 3065–3096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Peng, A.; Xu, H.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, J.; Yang, H.; Chen, J.; Huang, Y.; Li, X. Amorphous SnSe quantum dots anchoring on graphene as high performance anodes for battery/capacitor sodium ion storage. J. Power Sources 2020, 469, 228414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, N.; Li, Q.; Sun, J. Heterolayered SnO2/SnSe nanosheets for detection of NO2 at room temperature. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2022, 5, 2436–2444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, M.; John, P.; Fawy, K.F.; Manzoor, S.; Butt, K.Y.; Abid, A.G.; Messali, M.; Najam-Ul-Haq, M.; Ashiq, M.N. Facile synthesis of the SnTe/SnSe binary nanocomposite via a hydrothermal route for flexible solid-state supercapacitors. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 12009–12022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samui, R.; Saha, S.; Mandal, A.K.; Bhunia, A.K. Biocompatible 2D SnSe Nanoflake Employed Enhanced Photocatalytic Degradation of Rhodamine B. ChemistrySelect 2024, 9, e202402366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, P.; Yu, X.; Wang, Z.; Cao, M.; Yang, X.; Du, Y.; Zhao, J.; Xing, J.; Zhang, J.; Guo, K. Aliovalent Doping and Texture Engineering Facilitating High Thermoelectric Figure of Merit of SnSe Prepared by Low-Temperature Hydrothermal Synthesis. Small 2025, 21, 2502827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiss, P.; Carriere, M.; Lincheneau, C.; Vaure, L.; Tamang, S. Synthesis of semiconductor nanocrystals, focusing on nontoxic and earth-abundant materials. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 10731–10819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, S.G.; Hyeon, T. Formation mechanisms of uniform nanocrystals via hot-injection and heat-up methods. Small 2011, 7, 2685–2702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.; Zhang, L.; Sun, M.; Wang, M.; Chen, W.; Lin, S.; Zhu, H. Large scale self-assembly of SnSe nanosheets prepared by the hot-injection method for photodetector and capacitor applications. Mater. Today Energy 2019, 12, 418–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Li, Y.; Zhou, B.; Wang, X.; Cartwright, A.N.; Swihart, M.T. Shape-controlled synthesis of SnE (E = S, Se) semiconductor nanocrystals for optoelectronics. Chem. Mater. 2014, 26, 3515–3521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Wu, Y.; Cui, J.; Ran, Y.; Lin, W.; Liu, L.M.; Ye, J.; Zhang, Y.; Cabot, A. Self-induced strain in 2D chalcogenide nanocrystals with enhanced photoelectrochemical responsivity. Chem. Mater. 2020, 32, 2774–2781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abutbul, R.E.; Segev, E.; Samuha, S.; Zeiri, L.; Ezersky, V.; Makov, G.; Golan, Y. A new nanocrystalline binary phase: Synthesis and properties of cubic tin monoselenide. CrystEngComm 2016, 18, 1918–1923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Kergommeaux, A.; Faure-Vincent, J.; Pron, A.; de Bettignies, R.; Malaman, B.; Reiss, P. Surface oxidation of tin chalcogenide nanocrystals revealed by 119Sn–Mössbauer spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 11659–11666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, R.; Wei, M.; Jiang, G.; Liu, W.; Zhu, C. Study of the preperation of snse nanorods with selenium dioxide as source. Chem. Lett. 2014, 43, 693–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, J.; Schindelhauer, L.; Ruhmlieb, C.; Wehrmeister, M.; Tsangas, T.; Mews, A. Controlled Growth of Two-Dimensional SnSe/SnS Core/Crown Heterostructures. Nano Lett. 2024, 24, 13624–13630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukai, K.; Wanibuchi, R.; Nunomura, Y. Improved performance of solar cells using chemically synthesized SnSe nanosheets as light absorption layers. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2024, 35, 680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barma, S.V.; Jathar, S.B.; Huang, Y.T.; Jadhav, Y.A.; Rahane, G.K.; Rokade, A.V.; Nasane, M.P.; Rahane, S.N.; Cross, R.W.; Suryawanshi, M.P.; et al. Synthesis and interface engineering in heterojunctions of tin-selenide-based nanostructures for photoelectrochemical water splitting. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2024, 7, 1986–1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wan, Y.; Wen, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, H.; Qiu, J.; Zhu, Z.; Sun, Z.; Gao, X.; Bai, S.; et al. SnSe nanosheets with Sn vacancies catalyse H2O2 production from water and oxygen at ambient conditions. Nat. Catal. 2025, 8, 465–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, G.H.; Kumar, J.N.; Rao, N.M.; Uthanna, S. Preparation and characterization of flash evaporated tin selenide thin films. J. Cryst. Growth 2007, 306, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boscher, N.D.; Carmalt, C.J.; Palgrave, R.G.; Parkin, I.P. Atmospheric pressure chemical vapour deposition of SnSe and SnSe2 thin films on glass. Thin Solid Films 2008, 516, 4750–4757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indirajith, R.; Srinivasan, T.P.; Ramamurthi, K.; Gopalakrishnan, R. Synthesis, deposition and characterization of tin selenide thin films by thermal evaporation technique. Curr. Appl. Phys. 2010, 10, 1402–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z.C.; Liu, J.D.; Wang, X.; Meng, X.D.; Wang, Y.L. Growth characteristics of Ag nanocrystalline thin films prepared by pulsed laser ablation in vacuum. Chin. J. Lasers 2019, 46, 0903003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, T.; Hiramatsu, H.; Hosono, H.; Kamiya, T. Heteroepitaxial growth of SnSe films by pulsed laser deposition using Se-rich targets. J. Appl. Phys. 2015, 118, 205302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teghil, R.; Santagata, A.; Marotta, V.; Orlando, S.; Pizzella, G.; Giardini-Guidoni, A.; Mele, A. Characterization of the plasma plume and of thin film epitaxially produced during laser ablation of SnSe. Appl. Surf. Sci. 1995, 90, 505–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, S.; Yuan, D.; Yan, G.; Wang, J.; Liang, B.; Fu, G.; Wang, S. The transverse thermoelectric effect in a-axis inclined oriented SnSe thin films. J. Mater. Chem. C 2018, 6, 12858–12863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.; Zheng, Z.; Yang, G. All-layered 2D optoelectronics: A high-performance UV–vis–NIR broadband SnSe photodetector with Bi2Te3 topological insulator electrodes. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2017, 27, 1701823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Suen, C.H.; Yau, H.M.; Zhou, F.; Chai, Y.; Tang, X.; Zhou, X.; Onofrio, N.; Dai, J.Y. A dual mode electronic synapse based on layered SnSe films fabricated by pulsed laser deposition. Nanoscale Adv. 2020, 2, 1152–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, K.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, J.; Liu, S.; Cui, Y.; Zhu, R.; Cui, Y. Pulsed laser deposited SnS-SnSe nanocomposite as a new anode material for lithium ion batteries. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2017, 12, 7404–7410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sava, F.; Borca, C.N.; Galca, A.C.; Socol, G.; Grolimund, D.; Mihai, C.; Velea, A. Structural characterisation and thermal stability of SnSe\GaSb stacked films. Philos. Mag. 2019, 99, 55–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, J.; Zang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Shi, J.A.; Jiang, T.; Gong, Y.; Song, C.; Ji, S.; Wang, L.; et al. Molecular Beam Epitaxy-Grown SnSe in the Rock-Salt Structure: An Artificial Topological Crystalline Insulator Material. Adv. Mater. 2015, 27, 4150–4154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, W.; Vishwanath, S.; Liu, J.; Kong, L.; Lou, R.; Dai, Z.; Sadowski, J.T.; Liu, X.; Lien, H.-H.; Chaney, A.; et al. Electronic structure of the metastable epitaxial rock-salt SnSe {111} topological crystalline insulator. Phys. Rev. X 2017, 7, 041020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aniagor, C.O.; Igwegbe, C.A.; Ighalo, J.O.; Oba, S.N. Adsorption of doxycycline from aqueous media: A review. J. Mol. Liq. 2021, 334, 116124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C.; Cao, X.; Wu, X.J.; He, Q.; Yang, J.; Zhang, X.; Chen, J.; Zhao, W.; Han, S.; Nam, G.-H.; et al. Recent advances in ultrathin two-dimensional nanomaterials. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 6225–6331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Li, Z.; Xia, Z.; Ci, H.; Cai, J.; Song, Y.; Yu, L.; Yin, W.; Dou, S.; Sun, J.; et al. Confining MOF-derived SnSe nanoplatelets in nitrogen-doped graphene cages via direct CVD for durable sodium ion storage. Nano Res. 2019, 12, 3051–3058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.D.; Aamir, M.; Sohail, M.; Sher, M.; Baig, N.; Akhtar, J.; Revaprasadu, N. Bis (selenobenzoato) dibutyltin (iv) as a single source precursor for the synthesis of SnSe nanosheets and their photo-electrochemical study for water splitting. Dalton Trans. 2018, 47, 5465–5473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salgado, E.B.; Llanderal, D.E.L.; Nair, M.T.S.; Nair, P.K. Thin film thermoelectric elements of p–n tin chalcogenides from chemically deposited SnS–SnSe stacks of cubic crystalline structure. Semicond. Sci. Technol. 2020, 35, 045006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Sando, D.; Nagarajan, V. Chemical route derived bismuth ferrite thin films and nanomaterials. J. Mater. Chem. C 2016, 4, 4092–4124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, G.; Xue, X.X.; Yang, M.; Yang, J.; Liu, X.; Lu, H.; Jiang, Y.; Jin, Y.; Yuan, Q.; Sun, J.; et al. Modulated anisotropic growth of 2D SnSe based on the difference in a/b/c-axis edge atomic structures. Chem. Mater. 2021, 33, 4231–4239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davitt, F.; Manning, H.G.; Robinson, F.; Hawken, S.L.; Biswas, S.; Petkov, N.; van Druenen, M.; Boland, J.J.; Reid, G.; Holmes, J.D. Crystallographically controlled synthesis of SnSe nanowires: Potential in resistive memory devices. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 7, 2000474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kevin, P.; Malik, S.N.; Malik, M.A.; O’Brien, P. The aerosol assisted chemical vapour deposition of SnSe and Cu2SnSe3 thin films from molecular precursors. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 14328–14330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmet, I.Y.; Hill, M.S.; Raithby, P.R.; Johnson, A.L. Tin guanidinato complexes: Oxidative control of Sn, SnS, SnSe and SnTe thin film deposition. Dalton Trans. 2018, 47, 5031–5048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Pang, F. A facile way to control phase of tin selenide flakes by chemical vapor deposition. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2018, 702, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallavolu, M.R.; Minnam Reddy, V.R.; Guddeti, P.R.; Park, C. Development of SnSe thin films through selenization of sputtered Sn-metal films. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2019, 30, 15980–15988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Zhang, X.; Lei, L.; Nie, Y.; Xiang, G. Rapid synthesis of thermoelectric SnSe thin films by MPCVD. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 11990–11993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyagi, S.; Yadav, S.; Wani, V.; Singh, S.; Biswas, S.; Prajapati, K.N.; Kamble, V.B. CVD Growth of Tin Selenide Thin Films for Optoelectronic Applications. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE Region 10 Symposium (TENSYMP), Mumbai, India, 1–3 July 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Wong, M.C.; Mao, J.; Wu, Z.; Hao, J. Synthesis and enhanced piezoelectric response of CVD-grown SnSe layered nanosheets for flexible nanogenerators. Nano Res. 2023, 16, 11839–11845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goswami, P.; Prajapat, P.; Vashishtha, P.; Pandey, A.; Gupta, G. Phase-controlled tin selenide photodetectors for visible blind to near-infrared optical radiation. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 2023, 6, 611–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, M.; Barman, P.K.; Chowdhury, S.; Manikandan, D.; Basu, N.; Nayak, P.K.; Sethupathi, K. In Situ Simultaneous Growth of Layered SnSe2 and SnSe: A Linear Precursor Approach. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2025, 12, e00239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drozd, V.E.; Nikiforova, I.O.; Bogevolnov, V.B.; Yafyasov, A.M.; Filatova, E.O.; Papazoglou, D. ALD synthesis of SnSe layers and nanostructures. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2019, 42, 125306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, J.W.; Yoo, C.; Kim, W.; Choi, W.; Park, B.; Lee, Y.K.; Hwang, C.S. Atomic layer deposition of SnSex thin films using Sn(N(CH3)2)4 and Se(Si(CH3)3)2 with NH3 co-injection. Dalton Trans. 2022, 51, 594–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Shi, X.; Xu, F.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, W.; Chen, L.; Li, Q.; Uher, C.; Day, T.; Snyder, G.J. Copper ion liquid-like thermoelectrics. Nat. Mater. 2012, 11, 422–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, K.F.; Loo, S.; Guo, F.; Chen, W.; Dyck, J.S.; Uher, C.; Hogan, T.; Polychroniadis, E.K.; Kanatzidis, M.G. Cubic AgPbmSbTe2+m: Bulk thermoelectric materials with high figure of merit. Science 2004, 303, 818–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heremans, J.P.; Jovovic, V.; Toberer, E.S.; Saramat, A.; Kurosaki, K.; Charoenphakdee, A.; Snyder, G.J. Enhancement of thermoelectric efficiency in PbTe by distortion of the electronic density of states. Science 2008, 321, 554–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sales, B.C.; Mandrus, D.W.R.K.; Williams, R.K. Filled skutterudite antimonides: A new class of thermoelectric materials. Science 1996, 272, 1325–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhyee, J.S.; Lee, K.H.; Lee, S.M.; Cho, E.; Kim, S.I.; Lee, E.; Kotliar, G. Peierls distortion as a route to high thermoelectric performance in In4Se3-δ crystals. Nature 2009, 459, 965–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poudel, B.; Hao, Q.; Ma, Y.; Lan, Y.; Minnich, A.; Yu, B.; Yan, X.; Wang, D.; Muto, A.; Vashaee, D.; et al. High-thermoelectric performance of nanostructured bismuth antimony telluride bulk alloys. Science 2008, 320, 634–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sassi, S.; Candolfi, C.; Vaney, J.B.; Ohorodniichuk, V.; Masschelein, P.; Dauscher, A.; Lenoir, B. Assessment of the thermoelectric performance of polycrystalline p-type SnSe. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2014, 104, 212105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Lu, P.; Shi, X.; Xu, F.; Zhang, T.; Snyder, G.J.; Chen, L. Ultrahigh thermoelectric performance in mosaic crystals. Adv. Mater. 2015, 27, 3639–3644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhao, L.D. Thermoelectric materials: Energy conversion between heat and electricity. J. Mater. 2015, 1, 92–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, K.; Lu, X.; Zhan, H.; Hui, S.; Tang, X.; Wang, G.; Dai, J.; Uher, C.; Zhou, X. Broad temperature plateau for high ZT s in heavily doped p-type SnSe single crystals. Energy Environ. Sci. 2016, 9, 454–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.L.; Wang, H.; Chen, Y.Y.; Day, T.; Snyder, G.J. Thermoelectric properties of p-type polycrystalline SnSe doped with Ag. Mater. Chem. A 2014, 2, 11171–11176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.D.; Tan, G.; Hao, S.; He, J.; Pei, Y.; Chi, H.; Wang, H.; Gong, S.; Xu, H.; Dravid, V.P.; et al. Ultrahigh power factor and thermoelectric performance in hole-doped single-crystal SnSe. Science 2016, 351, 141–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, N.K.; Bathula, S.; Gahtori, B.; Tyagi, K.; Haranath, D.; Dhar, A. The effect of doping on thermoelectric performance of p-type SnSe: Promising thermoelectric material. J. Alloys Compd. 2016, 668, 152–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Chere, E.K.; Sun, J.; Cao, F.; Dahal, K.; Chen, S.; Ren, Z. Studies on thermoelectric properties of n-type polycrystalline SnSe1-xSx by iodine doping. Adv. Energy Mater. 2015, 5, 1500360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.M.; Zhao, J.; Zhou, M.; Jiang, X.X.; Leng, H.Q.; Li, L.F. Thermoelectric performance of SnS and SnS–SnSe solid solution. J. Mater. Chem. A 2015, 3, 4555–4559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, J.; Xiao, G.; Jiang, T.; Wang, L.; Dai, Q.; Zou, B.; Liu, B.; Wei, Y.; Chen, G.; Zou, G. Shape and size controlled synthesis and properties of colloidal IV–VI SnSe nanocrystals. CrystEngComm 2011, 13, 4161–4166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chere, E.K.; Zhang, Q.; Dahal, K.; Cao, F.; Mao, J.; Ren, Z. Studies on thermoelectric figure of merit of Na-doped p-type polycrystalline SnSe. J. Mater. Chem. A 2016, 4, 1848–1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duong, A.T.; Nguyen, V.Q.; Duvjir, G.; Duong, V.T.; Kwon, S.; Song, J.Y.; Lee, J.K.; Lee, J.E.; Park, S.; Min, T.; et al. Achieving ZT= 2.2 with Bi-doped n-type SnSe single crystals. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 13713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kucek, V.; Plechacek, T.; Janicek, P.; Ruleova, P.; Benes, L.; Navratil, J.; Drasar, C. Thermoelectric properties of Tl-doped SnSe: A hint of phononic structure. J. Electron. Mater. 2016, 45, 2943–2949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, M.; Shao, H.; Hu, H.; Li, D.; Xu, J.; Liu, G.; Shen, H.; Xu, J.; Jiang, H.; Jiang, J. Single crystal growth of Sn0.97Ag0.03Se by a novel horizontal Bridgman method and its thermoelectric properties. J. Cryst. Growth 2017, 460, 112–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, J.; Sun, Q.; Qin, P.; Cheng, Z.; Ge, Z.; Dou, S. Three-stage inter-orthorhombic evolution and high thermoelectric performance in Ag-doped nanolaminar SnSe polycrystals. Adv. Energy Mater. 2017, 7, 1700573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.C.; Li, D.; Qin, X.Y.; Zhang, J. Enhanced thermoelectric performance of p-type SnSe doped with Zn. Scr. Mater. 2017, 126, 6–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, C.W.T.; Song, S.; Tseng, Y.C.; Tritt, T.M.; Bogdan, J.; Mozharivskyj, Y. Microstructural instability and its effects on thermoelectric properties of SnSe and Na-doped SnSe. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 49442–49453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shankar, M.R.; Prabhu, A.N.; Ashok, A.M.; Davis, N.; Srinivasan, B.; Mishra, V. Role of Bi/Te co-dopants on the thermoelectric properties of SnSe polycrystals: An experimental and theoretical investigation. J. Mater. Sci. 2024, 59, 13055–13077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Dou, W.; Li, Y.; Ying, P.; Tang, G. A Review of Polycrystalline SnSe Thermoelectric Materials: Progress and Prospects. Acta Metall. Sin. (Engl. Lett.) 2025, 38, 733–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Yang, X.; Shi, T.E.; Bao, W.Q.; Feng, J.; Ge, Z.H. One-Step Carrier Modulation and Nano-Composition Enhancing Thermoelectric and Mechanical Properties of p-Type SnSe Polycrystals by Introducing Ag9GaSe6 Compound. Acta Metall. Sin. (Engl. Lett.) 2025, 38, 781–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrios-Salgado, E.; Nair, M.T.S.; Nair, P.K. Chemically deposited SnSe thin films: Thermal stability and solar cell application. ECS J. Solid State Sci. Technol. 2014, 3, Q169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, V.P.; Gireesan, K.; Desai, C.F. Photoconductivity of SnSe thin films. J Mater Sci Lett 1992, 11, 380–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinde, D.V.; Min, S.K.; Sung, M.M.; Shrestha, N.K.; Mane, R.S.; Han, S.H. Photovoltaic properties of nanocrystalline SnSe–CdS. Mater. Lett. 2014, 115, 244–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathinettam Padiyan, D.; Marikani, A.; Murali, K.R. Electrical and photoelectrical properties of vacuum deposited SnSe thin films. Cryst. Res. Technol. J. Exp. Ind. Crystallogr. 2000, 35, 949–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, K.J.; Pradeep, B.; Mathai, E. Tin selenide (SnSe) thin films prepared by reactive evaporation. J. Mater. Sci. 1994, 29, 1581–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelken, R.D.; Berry, A.K.; Van Doren, T.P.; Boone, J.L.; Shahnazary, A. Electrodeposition and analysis of tin selenide films. Electrochem. Soc. 1986, 133, 581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, R.K.; Pawar, P.S.; Nandi, R.; Neerugatti, K.E.; Kim, Y.T.; Cho, J.Y.; Heo, J. A qualitative study of SnSe thin film solar cells using SCAPS 1D and comparison with experimental results: A pathway towards 22.69% efficiency. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2022, 244, 111835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Rani, S.; Singh, Y.; Kumar, A.; Singh, V.N. Strategy to improve the efficiency of tin selenide based solar cell: A path from 1.02 to 27.72%. Sol. Energy 2022, 232, 146–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Leng, M.; Xia, Z.; Zhong, J.; Song, H.; Liu, X.; Yang, B.; Zhang, J.; Chen, J.; Zhou, K.; et al. Solution-Processed Antimony Selenide Heterojunction Solar Cells. Adv. Energy Mater. 2014, 4, 1301846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, G.; Zhang, S.; Boix, P.P.; Wong, L.H.; Sun, L.; Lien, S.Y. Towards high efficiency thin film solar cells. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2017, 87, 246–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandi, R.; Pawar, P.S.; Neerugatti, K.E.; Cho, J.Y.; Kim, S.; Cho, S.H.; Heo, J. Vapor-Transport-Deposited Orthorhombic-SnSe Thin Films: A Potential Cost-Effective Absorber Material for Solar-Cell Applications. Sol. RRL 2022, 6, 2100676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd El-Rahman, K.F.; Darwish, A.A.A.; El-Shazly, E.A.A. Electrical and photovoltaic properties of SnSe/Si heterojunction. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2014, 25, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.M.; Ji, I.A.; Bang, J.H. Metal selenides as a new class of electrocatalysts for quantum dot-sensitized solar cells: A tale of Cu1.8Se and PbSe. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2014, 6, 2335–2343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, J.; Wu, J.; Jia, J.; Wu, S.; Zhou, P.; Tu, Y.; Lan, Z. Cobalt selenide nanorods used as a high efficient counter electrode for dye-sensitized solar cells. Electrochim. Acta 2015, 168, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Liang, S.; Shi, Y.; Hao, C.; Wang, X.; Ma, T. Transition Metal Selenides as Efficient Counter-Electrode Materials for Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2015, 17, 28985–28992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devendra, K.C.; Shah, D.K.; Kumar, S.; Bhattarai, N.; Adhikari, D.R.; Khattri, K.B.; Akhtar, M.S.; Umar, A.; Ibrahim, A.A.; Alhamami, M.A.M.; et al. Enhanced solar cell efficiency: Copper zinc tin sulfide absorber thickness and defect density analysis. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2023, 34, 1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinde, A.; Hingane, D.; Supekar, A.; Hande, V.; Patil, R.S. Temperature effects on Cadmium Selenide semiconductor-sensitized solar cells with SnO2 deposition as electron transport layer. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2024, 35, 1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Song, Q.; Wu, L.; Su, X.; Hu, X.; Wang, X.; Zhang, L.; Chai, J.; Wang, S. Effects of the Annealing Conditions on the Properties of Cu2ZnGeSe4 Thin Film Solar Cells. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. Mater. 2025, 35, 1426–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walake, S.; Rondiya, S.; Jadkar, S.; Jadhav, Y.A. Colloidal synthesis of high-quality Cu2MnSnS4 nanocrystals: Structural, morphological, and optoelectronic investigation for applications in thin-film solar cells. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2025, 36, 548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Du, C.; Chen, G. Thermoelectric Materials and Applications in Buildings. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2025, 149, 101402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, K.A.; Anderson, C.M. Phase-change memory devices with stacked Ge-chalcogenide/Sn-chalcogenide layers. Microelectron. J. 2017, 38, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liu, B.; Xiang, Q.; Wang, Q.; Hou, X.; Chen, D.; Shen, G. Spray-painted binder-free SnSe electrodes for high-performance energy-storage devices. ChemSusChem 2014, 7, 308–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Kim, Y.; Park, Y.; Jo, Y.N.; Kim, Y.J.; Choi, N.S.; Lee, K.T. SnSe Alloy as a Promising Anode Material for Na-Ion Batteries. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 50–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhao, X.; Li, J. SnSe/Carbon Nanocomposite Synthesized by High Energy Ball Milling as an Anode Material for Sodium-Ion and Lithium-Ion Batteries. Electrochim. Acta 2015, 176, 1296–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Chen, Y.; Yin, X.; Lai, X.; Wang, J.; Jian, J. SnSe nanosheet array on carbon cloth as a high-capacity anode for sodium-ion batteries. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 42811–42822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Li, P.; Zheng, H.; Liu, Q.; Lv, F.; Wu, J.; Wang, H.; Guo, S. Ultrathin Layered SnSe Nanoplates for Low Voltage, High-Rate, And Long-Life Alkali-Ion Batteries. Small 2017, 13, 1702228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, W.; Ma, B.; Chen, X. Rational Material Design for Ultrafast Rechargeable Lithium-Ion Batteries. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 5926–5940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, D.; Yang, L.; Hu, R.; Liu, J.; Che, R.; Cui, J.; Wu, Y.; Chen, W.; Huang, J.; Zhu, M.; et al. Sn–C and Se–C Co-Bonding SnSe/Few-Layered Graphene Micro–Nano Structure: Route to a Densely Compacted and Durable Anode for Lithium/Sodium-Ion Batteries. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 36685–36696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakim, C.; Sabi, N.; Saadoune, I. Mixed structures as a new strategy to develop outstanding oxides-based cathode materials for sodium ion batteries: A review. J. Energy Chem. 2021, 61, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Qin, L.; Xu, X.; Kim, K.; Liu, J.; Kang, J.; Kim, K.H. SnSex (x = 1, 2) nanoparticles encapsulated in carbon nanospheres with reversible electrochemical behaviors for lithium-ion half/full cells. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 431, 133463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Wang, L.; Zhuo, M.; Ni, W.; Wang, H.; Ma, J. Layered tin sulfide and selenide anode materials for Li- and Na-ion batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A 2018, 6, 12185–12214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z.; Olvera, A.; Casamento, J.; Lopez, J.S.; Williams, L.; Lu, R.; Shi, G.; Poudeu, P.F.P.; Kioupakis, E. Semiconducting High-Entropy Chalcogenide Alloys with Ambi-ionic Entropy Stabilization and Ambipolar Doping. Chem. Mater. 2020, 32, 6070–6077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Phase | Type of Structure | Space Group | Lattice Parameters [A] | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| α-SnSe | Orthogonal | Pnma | a = 11.37, b = 4.19, c = 4.44 | [22] |

| β-SnSe | Rock salt Cube | Fm-3m | a = 4.31, b = 11.71, c = 4.42 | [22] |

| π-SnSe | Hexagonal wurtzite | P63mc | a = b = c = 11.97 | [65] |

| Year | Morphology | Pressure | Gas | Sources | Thickness | Temperature | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2008 | Thin flims | 100 Torr | Ar/H2 | Se, SnSe | 300 nm | 550–700 °C | [154] |

| 2014 | Thin flims | Atmospheric | Ar | [Sn(Ph2PSe2)2] | 1.5 µm | 400 °C | [174] |

| 2014 | Nanowires | 100–250 Torr | Ar/H2 | Se, SnSe | ≈30–40 nm | 950 °C | [81] |

| 2018 | Thin flims | Atmospheric | Ar | Tin guanidinato complexes | 100 nm | 400 °C | [175] |

| 2018 | Nanoflakes | 1 Pa | Ar | Se, SeO2 | ≈59.8–95.1 nm | 850 °C | [176] |

| 2019 | Thin flims | 300 mTorr | N2 | Se, Sn | 1 µm | 300–450 °C | [177] |

| 2019 | Nanoflakes | Atmospheric | Ar/H2 | Se, Sn-MOF | ≈0.5 µm | 450 °C | [168] |

| 2020 | Thin flims | 700 Pa | Ar/H2 | SeSO2, SnCl4·5H2O | 100 nm | 380 °C | [178] |

| 2021 | Nanoflakes | Atmospheric | Ar/H2 | Se, SnBr2 | ≈1.64–37.5 nm | 500 °C | [172] |

| 2022 | Thin flims | 1 mbar | Ar | SnSe | 80–100 nm | 800 °C | [179] |

| 2023 | Nanoflakes | Atmospheric | N2 | SnSe | 27 nm | 540–570 °C | [180] |

| 2024 | Thin flims | 10−3 mbar | Ar/H2 | SnSe | 100 nm | 680 °C | [181] |

| 2025 | Nanosheets | Atmospheric | Ar/H2 | Se, SnCl2 | 1–2 µm | 405 °C | [182] |

| Year | Materials | Cell | JSC (mA/cm2) | VOC | FF (%) | η (%) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2014 | SnSe thin film | FTO/CdS/SnSe/carbon-pat | 1.70 | 215 | 26 | 0.10 | [211] |

| 2014 | SnSe thin film | ITO/CdS/SnSe/Au | 5.37 | 370 | 30 | 0.80 | [213] |

| 2014 | SnSe thin film | Al/SnSe/Si/In | 17.23 | 425 | 44 | 6.44 | [222] |

| 2014 | Cu1.8Se nanoflakes | FTO/TiO2/Cu1.8Se | 20.50 | 540 | 50 | 5.01 | [223] |

| 2014 | PbSe nanoparticles | FTO/TiO2/PbSe | 16.70 | 590 | 48 | 4.71 | [223] |

| 2015 | CoSe2 nanorods | FTO/TiO2/CoSe2 | 17.04 | 743 | 66.20 | 8.38 | [224] |

| 2015 | MoSe2 nanosheets | FTO/TiO2/MoSe2 | 1.30 | 730 | 65 | 6.70 | [225] |

| 2023 | CZTS thin film | ZnO-Al/i-ZnO/n-CdS/CZTS/Mo | 36.64 | 909 | 79.74 | 26.58 | [226] |

| 2024 | CdSe nanocrystals | FTO/SnO2/CdSe/CuS | 4.155 | 157 | 42.33 | 0.26 | [227] |

| 2025 | Cu2ZnGeSe4 thin film | Mo/CZGSe/CdS/i-ZnO/ITO/Ni/Al | 21.89 | 599.92 | 39 | 5.12 | [228] |

| 2025 | Cu2MnSnS4 nanocrystals | FTO/TiO2/n-CdS/p-CMTS | 2.30 | 680 | 68 | 1.1 | [229] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, C.; Guo, Z.; Tan, F.; Zhou, J.; Li, X.; Cao, X.; Yang, Y.; Xie, Y.; Feng, Y.; Huang, C.; et al. SnSe: A Versatile Material for Thermoelectric and Optoelectronic Applications. Coatings 2026, 16, 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16010056

Zhang C, Guo Z, Tan F, Zhou J, Li X, Cao X, Yang Y, Xie Y, Feng Y, Huang C, et al. SnSe: A Versatile Material for Thermoelectric and Optoelectronic Applications. Coatings. 2026; 16(1):56. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16010056

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Chi, Zhengjie Guo, Fuyueyang Tan, Jinhui Zhou, Xuezhi Li, Xi Cao, Yikun Yang, Yixian Xie, Yuying Feng, Chenyao Huang, and et al. 2026. "SnSe: A Versatile Material for Thermoelectric and Optoelectronic Applications" Coatings 16, no. 1: 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16010056

APA StyleZhang, C., Guo, Z., Tan, F., Zhou, J., Li, X., Cao, X., Yang, Y., Xie, Y., Feng, Y., Huang, C., Li, Z., Qu, Y., & Li, L. (2026). SnSe: A Versatile Material for Thermoelectric and Optoelectronic Applications. Coatings, 16(1), 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16010056