Abstract

Industrial heat exchangers are widely used in industries such as petrochemicals, energy and power, and food processing, making them one of the most important pieces of heat and mass transfer equipment in industry. During operation, a layer of fouling often adheres to the heat transfer surfaces, which reduces the heat transfer coefficient of the equipment and increases the thermal resistance of the surfaces. Additionally, fouling can corrode the material of the heat transfer surfaces, compromise their integrity, and even lead to perforations and leaks, severely impacting equipment operation and safety while increasing energy consumption and costs for enterprises. The application of anti-fouling coatings on surfaces is a key technology to address fouling on heat transfer surfaces. This paper focuses on introducing major types of anti-fouling coatings, including polymer-based coatings, “metal material + X”-type coatings, “inorganic material + X”-type coatings, carbon-based material coatings, and other varieties. It analyzes and discusses the current research status and hotspots for these coatings, elaborates on their future development directions, and proposes ideas for developing new coating systems. On the other hand, this paper summarizes the current research on the main factors—surface roughness, surface free energy, surface wettability, and coating corrosion resistance—that affect the anti-fouling performance of coatings. It outlines the research hotspots and challenges in understanding the influence of these three factors and suggests that future research should consider the synergistic effects of multiple factors, providing valuable insights for further studies in the field of anti-fouling coatings.

1. Introduction

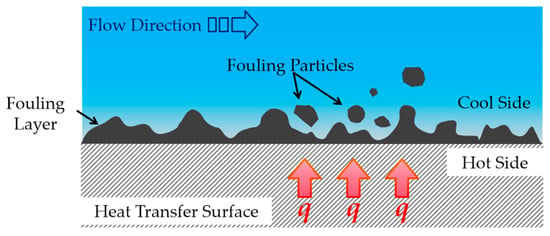

Industrial heat exchangers are widely used in industrial fields such as the chemical industry, petroleum, power generation, metallurgy, food processing, and pharmaceuticals. They are critical pieces of equipment designed to transfer heat between two or more fluids at different temperatures. For production enterprises, they represent one of the key devices for achieving energy conservation, reducing emissions, and improving energy utilization efficiency in the production process [1]. As industrial heat exchangers operate over time, fouling deposits gradually accumulate on the heat transfer surfaces, as shown in Figure 1. These deposits form solid layers resulting from combined effects of the temperature, fluid flow patterns, and chemical characteristics of the processed materials [2,3,4]. The fouling formation process involves coupled physicochemical phenomena of heat/mass transfer and momentum transfer, with biological activities also contributing under natural environmental conditions. Consequently, industrial heat exchanger fouling typically exists as complex mixtures. Based on formation mechanisms and composition, fouling can be classified into five main categories: crystallization fouling, particulate fouling, chemical reaction fouling, corrosion fouling, and biological fouling [5,6]. The deposited fouling layers create thermal barriers between heat transfer surfaces and process fluids, significantly increasing thermal resistance and reducing heat transfer coefficients. This leads to substantially diminished heat exchange efficiency, elevated energy consumption, and increased production costs. Furthermore, fouling deposits can corrode heat transfer surface materials, potentially causing perforations that lead to process fluid leakage from equipment. Such failures may result in significant economic losses or even personnel injuries.

Figure 1.

The fouling deposition process on industrial heat exchanger surfaces.

Therefore, the fouling problem has become one of the critical issues affecting the operational safety and heat transfer efficiency of industrial heat exchangers. To address this challenge, researchers have proposed three main solutions: fouling inhibitors, anti-fouling structural design optimization, and anti-fouling coatings. Each of these approaches has its own advantages and limitations. As a method that neither alters the composition of the heat transfer fluid nor significantly modifies the structure of the industrial heat exchanger, anti-fouling coatings possess substantial potential for fouling resistance and high application value, making them a favored solution among numerous researchers. This review covers prominent studies on anti-fouling coatings published between 2000 and 2025, and it focuses on the common anti-fouling coatings in the industrial heat exchange sector, analyzing and comparing the characteristics and existing issues of polymer-based anti-fouling coatings, “metal material + X”-type coatings, “inorganic material + X”-type coatings, carbon-based material coatings, and other types of anti-fouling coatings. It elaborates on the current research status of the anti-fouling mechanisms and the applicable scope of these different coatings, and it proposes their future development directions. On the other hand, regarding the three main factors influencing coating anti-fouling performance—surface free energy, wettability, and corrosion resistance of the coating—this paper describes the current research status of these influencing factors and points out that the synergistic interaction mechanisms among them need to be considered.

2. Industrial Heat Exchange Surface Anti-Fouling Coatings

To solve the problem of fouling deposition on industrial heat exchange surfaces, engineers initially adopted non-metallic coatings such as polymer materials, enamel, glass, and monomolecular polymers as protective layers to inhibit fouling adhesion. Compared to metallic materials, these non-metallic coatings exhibit lower thermal conductivity and higher inherent thermal resistance. While they effectively reduce fouling accumulation on industrial heat transfer surfaces, they simultaneously diminish the effective heat transfer efficiency of industrial heat exchangers. Consequently, such non-metallic coatings have not been widely adopted in the industry and are limited to specialized operating conditions or environments. To enhance the applicability of anti-fouling coatings, researchers worldwide have conducted extensive studies on the influence mechanisms between coating surface characteristics and fouling adhesion behavior. This research has evolved from single-component coatings to composite and gradient coatings, driving the diversification of anti-fouling coating technologies.

2.1. Polymer-Based Anti-Fouling Coatings

Polymer-based coatings offer simple preparation processes and flexible compositional combinations, enabling researchers to easily obtain composite coatings with various ratio characteristics. Förster et al. [7] investigated the crystallization fouling inhibition performance of perfluoroalkoxy copolymer (PFA), fluorinated ethylene propylene (FEP), and polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) coating materials, comparing their anti-fouling and heat transfer performance with uncoated heat exchange surfaces such as pure copper tubes, pure aluminum tubes, stainless steel tubes, and brass tubes. Experimental results showed that PFA, FEP, and PTFE polymer coatings exhibited longer fouling induction periods and significantly lower fouling thermal resistance than metal heat exchange surfaces, demonstrating superior fouling inhibition performance. However, due to the inherent properties of PTFE, it is difficult for it to firmly adhere to heat exchange surfaces, and its service life is significantly affected by working conditions. Therefore, PTFE anti-fouling coatings have limited engineering practicality.

In addition to research on polymer-based anti-fouling coatings for heat exchange tube surfaces, researchers have also conducted studies on anti-fouling coatings for plate heat exchange surfaces. Polyphenylene sulfide (PPS) and PTFE/PPS coatings [8] were investigated on carbon steel heat transfer surfaces for their performance against SiO2 particle fouling. Experimental results showed that heat exchange surfaces coated with PPS and PTFE/PPS had significantly fewer attached fouling particles compared to uncoated surfaces. Researchers attributed this result to the oxide film formed on PPS surfaces as a key factor inhibiting SiO2 particle deposition, while the high oxidation resistance of PTFE in the PTFE/PPS coating further prevented SiO2 particles from adhering effectively. Furthermore, various polymer-based coatings, including Teflon-based coatings, PPG electro-coatings, epoxy resin-based coatings, and phenolic plastic coatings, were tested on heat exchange plates of both gasketed plate heat exchangers and brazed plate heat exchangers [9]. All the polymer coatings demonstrated anti-fouling effects, but engineers concluded that PPG electro-coating offered the best balance between fouling resistance and cost-effectiveness for practical applications.

During the investigation of polymer-based anti-fouling coatings, researchers discovered that modified polymer coatings exhibit superior fouling resistance. Malayeri et al. [10] compared unstructured coatings (a blend of BN, aluminum silicate, fluorinated polyethylene wax, and silicone polyester resin) with nanostructured coatings (K–S1 and K–S2, featuring silicon nanoparticles dispersed in the matrix) for their efficacy against CaSO4 crystal fouling. By analyzing surface characteristics like roughness, contact angle, and surface energy, they demonstrated that nano-modified coatings (K–S1 and K–S2) exhibited longer fouling induction periods, lower fouling thermal resistance, and slower fouling thermal resistance curve slopes. Oldani et al. [11] employed a sol–gel method to prepare SiO2-modified fluorinated polymer coatings on heat exchanger tubes, evaluating their effectiveness in mitigating crystalline fouling deposition. In subsequent work [12], they coated heat exchanger surfaces with modified α–ω functionalized perfluoropolyethers (PFPE). Fouling resistance tests revealed that PFPE-modified coatings achieved minimal fouling accumulation, demonstrating exceptional anti-fouling performance. The PTFE coatings can also be deposited atop polydopamine-modified intermediate layers to form composite coatings [13]. The polydopamine interlayer enhances the durability of PTFE composites, enabling sustained anti-fouling performance across varying temperatures. Additionally, epoxy resin coatings modified with diatomite and polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) [14] show enhanced fouling resistance against crystalline deposits in moderate temperature media, outperforming epoxy coatings modified solely with diatomite.

The above analysis demonstrates that polymer-based coatings exhibit significant anti-fouling capabilities and deliver excellent fouling suppression effects on heat exchange surfaces. However, these coatings also face challenges with thermal stability under high-temperature conditions. Research on polymer-based anti-fouling coatings has revealed that modifying the interfacial properties of heat exchange surfaces is a critical factor in enhancing fouling resistance. Guided by this principle, studies focusing on altering surface interfacial characteristics to achieve anti-fouling performance have rapidly advanced. Researchers have developed various composite anti-fouling coatings to investigate the mechanisms by which interfacial properties inhibit fouling deposition.

2.2. “Metal Material + X” Hybrid Coatings

Anti-fouling coatings find applications across various industrial production sectors. In the food processing industry, such as the dairy sector, heat exchange equipment is essential for pasteurizing milk powder. Over prolonged use, heat exchange plates accumulate significant milk-based fouling layers and crystalline deposits, which directly impair the operational efficiency of the heat exchange equipment and the effectiveness of pasteurization. However, due to regulatory requirements in the food processing industry, polymer-based anti-fouling coatings cannot be fully utilized in this sector, necessitating the development of novel coatings tailored to meet the specific demands of the food industry.

To address this need, researchers initially adopted an approach of incorporating metallic elements into polymer-based coatings to modify their performance under high-temperature conditions, thereby developing “metal + polymer” composite anti-fouling coatings. Among these, Ni-based coatings are a typical example. Coatings such as Ni–Cu–P–PTFE, gradient Ni–P/Ni–Cu–P/Ni–Cu–P–PTFE, gradient Ni–P/Ni–P–PTFE, and Zn–Ni/PTFE have been demonstrated to effectively inhibit crystalline fouling deposition on heat exchange surfaces [15,16]. However, practical tests revealed that the same coating exhibited varying anti-fouling performance on different substrates. Furthermore, gradient Ni–P/Ni–Cu–P/Ni–Cu–P–PTFE and gradient Ni–P/Ni–P–PTFE coatings showed smaller reductions in heat transfer coefficients in fouling solutions, indicating thinner crystalline fouling layers on their surfaces. Notably, the gradient Ni–P/Ni–Cu–P/Ni–Cu–P–PTFE coating outperformed the gradient Ni–P/Ni–P–PTFE coating in fouling resistance. While the inhibition of biological fouling by such coatings is difficult to enhance solely by adjusting Ni and Cu metal content, it can be significantly improved by modulating the polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) polymer content. As the PTFE content increases, the surface energy of the coating changes accordingly. Experimental results demonstrated that composite coatings with varying PTFE content achieved biological fouling inhibition rates ranging from 68% to 94% [17,18].

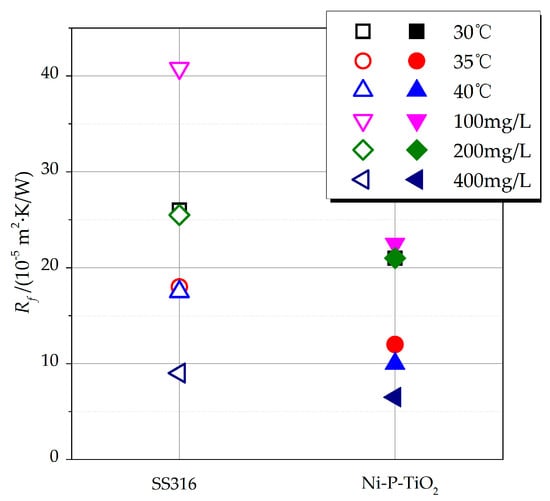

In addition to being combined with polymers to create anti-fouling coatings, Ni-based coatings such as common Ni–P and Ni–P–BN variants are also applied in fouling inhibition research. Ni–P and Ni–P–BN coatings [19] demonstrate effectiveness in suppressing CaSO4 fouling crystals on AISI304 stainless steel surfaces, though Ni–P–BN coatings exhibit inferior wear-corrosion resistance. Comparative studies between Ni–P–BN coatings and solvent-based/water-based coatings [20] reveal that Ni-based coatings deliver superior fouling inhibition and outperform their solvent-/water-based counterparts in durability. Notably, the anti-fouling performance of Ni–P coatings varies with the proportional content of amorphous, nanocrystalline, or mixed amorphous/nanocrystalline (hybrid crystal) structures [21,22]. Amorphous Ni–P coatings achieve optimal fouling resistance, while nanocrystalline coatings show declining performance with increased nanocrystalline content; hybrid crystal structures fall between these extremes. Further modifications, such as Ni–Cu–P [23] and Ni–P–PTFE [24,25] coatings, demonstrate that higher PTFE or Cu content increases crystalline fouling deposition. However, particulate fouling on Ni–P–PTFE coatings initially decreases then rises with increasing PTFE content. The anti-fouling efficacy of Ni–P coatings also stems from their surface microstructure [26,27], which inhibits biological fouling adhesion on copper heat exchanger tubes. The amorphous content nonlinearly influences microbial corrosion resistance, governed by complex mechanisms distinct from conventional chemical corrosion. Additionally, Ni–P–TiO2 composite coatings [28,29] significantly reduce MgO particulate fouling in plate heat exchanger experiments, as shown in Figure 2. The experimental results indicated a significant difference in the stable fouling thermal resistance values between the uncoated SS316 heat exchange surface and the Ni–P–TiO2-coated surface. Under the same experimental conditions, the stable fouling thermal resistance of the uncoated SS316 surface was considerably higher than that of the coated surface. Macroscopic images of the heat exchange plates after the experiment further revealed that the amount of MgO particulate fouling attached to the coated surface was significantly less. These findings demonstrate that the Ni–P–TiO2 coating possesses a remarkable ability to inhibit fouling deposition.

Figure 2.

The stable fouling resistance values of Ni-P-TiO2 coating and SS316 heat exchange surfaces under different experimental conditions.

The above analysis demonstrates that “metal material + X”-type anti-fouling coatings exhibit excellent fouling resistance performance. Their anti-fouling properties can be further enhanced by precisely controlling the crystalline structure, phase proportion, and doping elements within the coating. However, some experimental results indicate that the service life of such coatings on heat exchange surfaces is influenced by multiple factors including substrate material, heat transfer medium, and fouling type. A critical limitation arises from the gradual leaching of metal ions from the coating during prolonged service. This ion migration phenomenon not only affects heat exchange equipment performance but may also contaminate processed materials, posing potential threats to both operational safety and human health. These inherent constraints have consequently restricted the engineering application scope of “metal material + X” anti-fouling coatings in industrial settings.

2.3. “Inorganic Material + X”-Type Anti-Fouling Coating

A typical example of this type of coating is the TiO2 and SiO2 coating. Due to the excellent antibacterial properties, chemical stability, and high-temperature stability of TiO2 and SiO2, “inorganic non–metal + X” coatings show promising potential for industrial applications. However, the insufficient bonding strength between the coating and the heat exchange surface substrate severely limits the widespread adoption of this type of coating.

Professor Mingyan Liu has conducted a series of studies on anti-fouling coatings for geothermal water utilization, achieving remarkable results. Mingyan Liu et al. [30] prepared TiO2 thin films via liquid phase deposition (LPD) and pioneered the application of TiO2 micro-nano coatings for both fouling inhibition and heat transfer enhancement in heat exchangers. They found that coatings with superior anti-fouling performance exhibited lower surface energy and were thinner. Wang et al. [31] investigated the anti-fouling properties and pool boiling characteristics of vacuum-deposited TiO2 thin films. Experimental results demonstrated that nanoscale TiO2 films effectively resisted fouling, with CaCO3 deposits forming loose structures on their surfaces. Similarly, Wang et al. [32] employed LPD to fabricate TiO2 films on copper substrates and evaluated their fouling resistance in scaling solutions. Compared to polished copper surfaces, LPD–TiO2 coatings significantly prolonged the fouling induction period by hindering deposit adhesion. Further improvements were achieved by composite coatings combining TiO2 with other components. For instance, TiO2–fluoroalkylsilane (FPS) composite coatings [33,34,35] exhibited lower fouling thermal resistance and deposition rates, with loosely adhered deposits that were easily removable. When the surface roughness of TiO2–FPS coatings was modified via chemical etching, the treated surfaces showed reduced fouling thermal resistance in early-stage experiments, though the asymptotic fouling resistance in later stages remained unaffected.

Beyond TiO2, researchers have explored SiO2 as another promising inorganic material for anti-fouling applications. Song et al. [36] observed that crystalline fouling deposition rates on SiO2 coatings increased with solution temperature in geothermal water experiments. Notably, SiO2 and SiO2–FPS coatings prepared via sol–gel methods outperformed TiO2 coatings in both fouling inhibition and corrosion resistance. Chen et al. [37] deposited SiO2 coatings on copper substrates using LPD and tested their anti-fouling performance in simulated geothermal environments. The results indicated that SiO2-modified surfaces had lower fouling crystal deposition rates and quantities compared to smooth copper, though thicker SiO2 coatings provided more attachment sites, leading to higher fouling accumulation. The study highlighted SiO2 coatings’ advantages, such as excellent thermal stability, low internal stress, and absence of drawbacks common to organic/metal coatings, making them highly viable for industrial geothermal applications.

In summary, “inorganic material + X”-type anti-fouling coatings demonstrate strong potential in fouling mitigation. However, their higher thermal resistance and lower thermal conductivity relative to metallic materials necessitate further modifications, such as doping with other components to optimize heat transfer efficiency for practical applications.

2.4. Carbon-Based Anti-Fouling Coatings

In addition to polymer-based, “metal material + X”, and “inorganic material + X” anti-fouling coatings, carbon-based diamond-like carbon (DLC) coatings have also garnered significant attention from researchers. Förster et al. [7] investigated the adhesion resistance of DLC coatings against CaSO4 fouling. Experimental results demonstrated that while DLC-coated surfaces exhibited a longer fouling induction period compared to smooth heat exchange tubes, it was considerably shorter than that of PFA and PTFE polymer-based anti-fouling coatings. Although DLC coatings did not match the extended fouling induction periods of polymer-based coatings, the total crystalline fouling deposited on DLC surfaces was notably less, with a loose distribution that facilitated easy removal using soft brushes [38]. To enhance the early-stage anti-fouling performance of DLC coatings under pool boiling conditions, researchers developed fluorine-doped DLC (F–DLC) coatings [39], which successfully reduced the initial fouling thermal resistance and moderately prolonged the fouling induction period. Another carbon-based coating, amorphous carbon film, has shown exceptional anti-fouling properties due to its superior physicochemical characteristics. In one study, a hierarchical micro-nano structured amorphous carbon film was fabricated by combining surface micro-nano textures with amorphous carbon deposition [40]. Both static and dynamic fouling experiments revealed that this hierarchical structure effectively inhibited CaCO3 crystal adhesion and extended the fouling induction period on heat exchange surfaces.

Carbon nanomaterials such as carbon nanotubes (CNTs) and graphene have also been explored for anti-fouling applications. Xu et al. [41] developed Ni–P–rGO coatings to combat iron bacteria biofouling. Comparative analysis showed that the biofilm adhesion on Ni–P–rGO coatings was drastically lower (by orders of magnitude) than on bare carbon steel tubes, with the anti-fouling performance improving as the graphene content increased. At an optimal graphene concentration of 40 mg/L, biofilm adhesion was reduced to just 2.8 wt.% of that on uncoated surfaces. Kaleemullah Shaikh et al. [42] adhered multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs) to heat exchange tubes using gum arabic as a binder. Cyclic tests demonstrated that MWCNT coatings not only suppressed CaCO3 scaling but also enhanced heat transfer, with coated tubes exhibiting lower overall thermal resistance and thinner fouling layers compared to uncoated SS316L tubes. Further innovation involved blending graphene and MWCNTs as anti-fouling additives in heat transfer fluids [43], which not only inhibited fouling adhesion but also altered crystal morphology, significantly reducing fouling thermal resistance. Their research offers a novel approach for carbon-based anti-fouling material development.

In summary, carbon-based coatings exhibit promising potential in anti-fouling applications due to their stable physicochemical properties. However, challenges such as insufficient substrate adhesion, high internal stress leading to delamination, and complex fabrication processes currently limit their widespread adoption [38,39,40,41,42,43].

2.5. Other Types of Anti-Fouling Coatings

With the deepening research on anti-fouling coating mechanisms, other types of anti-fouling coatings have emerged, such as Fe–Al intermetallic compound coatings [44], Zr coatings [45], and pure Ti coatings [46], which are primarily metal-based. Additionally, there are two-dimensional anti-fouling coatings based on inorganic materials like hexagonal boron nitride (h–BN) [47], as well as superhydrophobic anti-fouling coatings formed by coupling metal ions with scale inhibitors, such as S–Cu2+/D–ACO [48] and PFSC–EDTA [49]. These coatings fill the gaps left by traditional materials in anti-fouling applications and further explore anti-fouling mechanisms.

3. Factors Influencing the Anti-Fouling Performance of Coatings

Coatings can effectively inhibit the adhesion of fouling deposits on material surfaces, prolong the fouling induction period, and reduce fouling thermal resistance. Some anti-fouling coatings also enhance heat transfer efficiency and improve corrosion resistance. This demonstrates that the surface properties of anti-fouling coatings play a critical role in their performance [50]. Therefore, it is essential to investigate the influence of coating surface characteristics on anti-fouling effectiveness and establish their structure–performance relationships. The key factors affecting anti-fouling performance include surface roughness, surface free energy, wettability, and corrosion resistance.

3.1. Surface Roughness

The surface roughness of heat exchange tubes/plates directly influences the structure of fouling crystals adhering to the interface and the fouling deposition rate. The bonding strength between adhered fouling crystals and the heat exchange interface increases with surface roughness, potentially reaching 30 times that of smooth surfaces [51,52,53]. Fouling crystal attachment also exhibits selective regional preferences [53]. However, as research progresses, some findings reveal differing mechanisms regarding how surface roughness affects fouling crystal adhesion, suggesting that describing fouling behavior solely through macro-scale roughness parameters is incomplete. Zhang et al. [54] analyzed influencing factors of the fouling induction period using an adhesion calculation model. Their model indicates that the relationship between surface roughness and the fouling induction period is complex, with a scale effect existing between fouling adhesion behavior and surface roughness. The material system of coatings also modulates the impact of surface roughness on the fouling induction period. Song et al. [36] introduced the concept of a “roughness coefficient I” to characterize coating surfaces. Based on its physical significance, they proposed that an ideal anti-scaling surface, which is resistant to both crystalline and particulate fouling, should be molecularly flat, defect-free, and hydrophobic. Liu et al. [55] concluded from experimental results that macro-scale surface roughness has limited influence on fouling adhesion, with no clear linear relationship observed; instead, anti-fouling performance correlates more strongly with substrate corrosion resistance. Other studies based on fouling adhesion models found that higher surface roughness does not linearly increase fouling deposition but asymptotically approaches an upper limit [56]. In the early stages, high roughness may accelerate crystalline fouling deposition [35]. Conversely, Yang et al. [57] reported that greater roughness shortens the fouling induction period but reduces total fouling accumulation, while smoother surfaces exhibit the opposite trend. This is because smoother surfaces require more fouling crystals to increase their roughness and reach a stable state. Kaleemullah Shaikh et al. [42] observed that MWCNT coatings having lower initial roughness had a much shorter fouling induction period than uncoated SS316L tubes having higher roughness. Within the first 20 h, the fouling thermal resistance on MWCNT coatings increased faster than that on SS316L surfaces. However, after 20 h, the fouling thermal resistance on MWCNT coatings stabilized, while it continued to rise on SS316L tubes, resulting in significantly higher total fouling thermal resistance for SS316L. The authors attributed this to fouling adhesion increasing the surface roughness of MWCNT coatings 15-fold during the induction period, which subsequently inhibited further fouling deposition before negative thermal resistance occurred. This result demonstrated that high surface roughness can suppress fouling behavior at certain stages.

Based on the research findings of the scholars mentioned above, a summary is presented in Table 1. As can be seen from the table, numerous scholars have conducted a series of studies focusing on how surface roughness inhibits the attachment of fouling deposits. These investigations primarily explore the influence of surface roughness on the patterns of fouling attachment. Some researchers have proposed inhibition mechanisms by which surface roughness affects the fouling attachment behavior. However, the related research efforts cannot fully elucidate how surface roughness inhibits the fouling attachment process. In particular, studies concerning the influence of heat exchanger surface roughness on the entire fouling attachment process—including the underlying mechanisms—are relatively limited at present. Further in-depth and systematic research is still required.

Table 1.

Research findings of the relationship between surface roughness and fouling.

In summary, while macro-scale surface roughness influences fouling crystal adhesion and may temporarily increase deposition rates during specific phases, no simple linear relationship exists between surface roughness and fouling accumulation. At micro scales, the effect of surface roughness on fouling behavior must be considered alongside other surface properties, such as surface energy, wettability, and corrosion resistance. Additionally, the scale effect between surface roughness and fouling crystal size may help explain these phenomena [36,42,51,52,53,54,55,56,57].

3.2. Surface Free Energy

Fouling ions/crystals are mixed within the heat transfer medium. When the medium comes into contact with the heat exchange surface, the fouling ions/crystals also interact with the surface. Consequently, the energy state at the interface between the heat exchange surface and the fouling ions/crystals significantly influences fouling adhesion behavior. Extensive research has been conducted to investigate this interfacial energy state. Generally, a lower surface free energy of the material correlates with reduced fouling deposition on the surface, a conclusion supported by studies on the anti-fouling properties of various materials [7,53,58,59,60,61]. Based on these findings, researchers suggest that enhancing the hydrophobicity of coatings or employing hydrophobic materials can help elucidate the interfacial forces between deposits and coatings [10].

Professor Cheng et al. [23,24] demonstrated through research on Ni-based anti-fouling coatings that fouling resistance correlates with surface energy rather than surface roughness. Their works further revealed that anti-fouling coatings exhibit optimal fouling inhibition within a specific surface free energy range, rather than relying solely on low surface free energy properties. Al–Janabi et al. [19,20,62] systematically reviewed prior studies and developed a numerical model analyzing the surface free energy–fouling relationship. This model indicates that higher electron-donating components (Lewis base) generate repulsive energy between anti-fouling coatings and fouling crystals, with this parameter being more critical than surface free energy itself in determining fouling deposition trends and coating performance. Their experimental observations on SiC surfaces [63] and nanostructured coatings (K–S1 and K–S2) [64] confirmed similar phenomena: modified surface free energy reduces fouling adhesion energy, enabling effective foulant removal through fluid shear stress, while micron-thick coatings achieved 40% surface free energy reduction. Notably, the deposition process showed no direct correlation with total surface free energy or Lifshitz–van der Waals energy. However, Al–Janabi acknowledged that current findings cannot fully explain the underlying mechanisms, warranting further theoretical investigation. To elucidate the surface free energy–anti-fouling relationship, most researchers employ DLVO theory and its extensions [28,29,65,66], establishing an optimal surface free energy formula (static) for minimal particulate fouling adhesion, as shown in Equation (1) [25,67].

In Equation (1), , , and represent the Lifshitz–van der Waals (LW) non-polar components of the heat transfer surface, particulate fouling, and water, respectively. This formula explains why the same type of fouling exhibits significant differences in adhesion amounts on different material surfaces. When the surface free energy of the coating is lower than this critical value, the adhesion behavior of particulate fouling is suppressed; conversely, when the two values are similar, the coating surface becomes prone to fouling adsorption. This indicates that there is no simple correlation between surface free energy and fouling behavior, and interfacial energy similarity between the heat transfer surface and fouling crystals may even increase fouling deposition rates. However, Cheng et al. [23,24] argue that for different types of fouling and anti-fouling coatings, the surface free energy of anti-fouling coatings exhibits optimal fouling inhibition within a specific range, suggesting that merely reducing surface free energy does not inherently enhance anti-fouling performance.

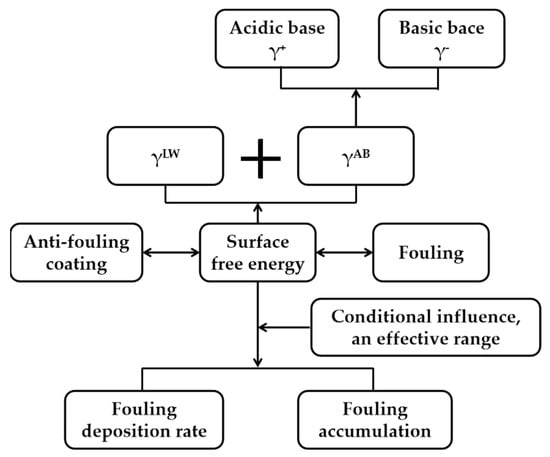

Thus, the influence of material surface energy on fouling adhesion follows complex mechanisms. The research approach on the influence of surface free energy on the adhesion behavior of foulant deposits is illustrated in Figure 3. Here, the components of surface free energy are key to revealing variations in the deposition rate and quantity of foulant attachment. A major research challenge lies in the significant differences in the surface free energy of various foulant types, which makes it difficult to establish a unified model that accurately reflects the impact of surface free energy components on foulant attachment behavior [68]. Low surface free energy reduces fouling adhesion, particularly during the early stages of fouling formation, but its effect diminishes in later stages. The polar component of surface free energy demonstrates more pronounced inhibition on fouling adhesion than the non-polar component, though the synergistic mechanism between these components requires further clarification.

Figure 3.

Research approach on the influence of surface free energy on the adhesion behavior of foulant deposits.

3.3. Wettability

Wettability characterizes the hydrophilic/hydrophobic properties of coating surfaces. For anti-fouling coatings, surface wettability influences the interaction behavior of fouling-containing media. Hydrophobic coatings can delay fouling adhesion [69], effectively prolong the fouling induction period on heat exchange surfaces, and significantly reduce the asymptotic value of fouling thermal resistance [10]. Moreover, hydrophobic surfaces restrict the size and quantity of crystalline fouling particles adhering to heat exchange surfaces [12]. Further, hydrophobic properties can be utilized to modulate the crystal structure of adhered fouling, thereby preventing the attachment of specific fouling crystal types [70].

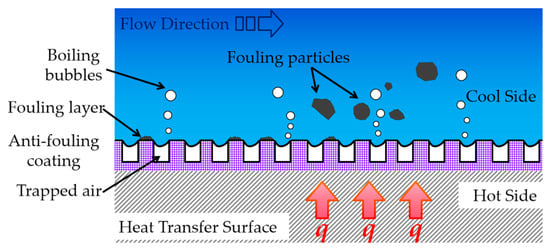

For fouling media on heat exchange surfaces, when the surface exhibits hydrophobicity, according to the Cassie–Baxter model theory, the hydrophobic surface “traps” abundant air pockets within its micro-nano hierarchical structure, preventing the heat transfer medium from contacting the surface [71,72]. Conversely, when the surface is hydrophilic, fouling nuclei in the heat transfer medium can directly contact surface crevices and adhere, subsequently growing into large-scale fouling “crystal blooms” [73], eventually covering the entire heat exchange surface with a thicker fouling layer. On the other hand, anti-fouling coatings having superior hydrophobic properties can also enhance pool boiling heat transfer [74,75]. Micro/nanostructures on the heat exchange surface generate numerous bubble nucleation sites and rising bubbles. These nucleation sites and detaching bubbles synergistically induce vibrations that dislodge loosely adhered fouling crystals from the surface, achieving anti-fouling effects [76,77], as shown in Figure 4. Nevertheless, in areas lacking boiling bubble nucleation sites, fouling will still occur. As the service time of the heat transfer surface increases, the accumulated fouling will gradually increase. Eventually, only the regions having active bubble nucleation sites will exhibit relatively less fouling deposition.

Figure 4.

Schematic diagram of the influence of wettability of anti-fouling coating on fouling.

Furthermore, with the introduction of amphiphobic (hydrophobic/oleophobic) coatings into anti-fouling applications, novel coatings leveraging dual repellency have emerged. Examples include superamphiphobic coatings for oil–water mixed environments [78], bioinspired long-term oil collectible mask (BLOCK) coatings [79], and durable bioinspired organogel coating (BIO coating) [80]. These coatings isolate fouling crystals from the material surface through their exceptional hydrophobicity and oleophobicity, preventing stable attachment and subsequent aggregation into dense fouling layers, thus achieving anti-fouling in complex multiphase environments.

However, since these novel anti-fouling coatings are primarily tested under ambient temperatures or non-heat-exchange experimental conditions, their applicability to heat exchange equipment surfaces and high-temperature durability requires further exploration [78,79,80].

3.4. Coating Corrosion Resistance

In heat exchangers, the heat transfer medium contains a substantial concentration of ions, including fouling ions and those introduced by the process fluid. These ions circulate through the tube and shell sides of the exchanger, simultaneously causing fouling deposition and corrosion on heat transfer surfaces. Consequently, anti-fouling coatings must be designed to address both challenges concurrently. Otherwise, fouling layers adhering to the surface will corrode and degrade the coating, compromising its durability.

To address these issues, researchers have integrated under-deposit corrosion studies with anti-fouling coating development. Zhao et al. [17] demonstrated that corrosion-resistant coatings exhibit inherent potential to resist both biological and crystalline fouling. Cheng et al. [81,82] proposed that fouling adhesion is not an isolated process but mediated by surface oxides or corrosion products acting as a “transitional interface” that bridges foulants and the substrate. Their findings revealed an intrinsic link between anti-fouling performance and corrosion resistance, where corrosion-prone surfaces are more susceptible to fouling. They also identified a nonlinear relationship between amorphous content in modified coatings and microbial corrosion resistance, with corrosion mechanisms being more complex than typical chemical interactions due to coating composition and microstructure. Zhang et al. [83] observed severe corrosion on anti-fouling coatings in geothermal water environments, significantly reducing service life. Although the complex fouling ion composition in geothermal water requires further mechanistic study, they emphasized that enhancing coating corrosion resistance during design is critical for durability. Wang et al. [72] developed an inorganic-filler-reinforced waterborne silicone resin coating that outperformed both filler-free counterparts and smooth copper surfaces in anti-fouling and corrosion resistance. The filler-modified coating achieved this through dual mechanisms: (1) reduced surface free energy minimized contact between foulant solutions and the coating surface, inhibiting foulant adhesion; (2) uniformly dispersed fillers created a tortuous “maze-like” barrier that impeded ion diffusion into the substrate, preserving coating–substrate adhesion and extending service life.

Thus, improving coating corrosion resistance mitigates damage from fouling crystals/ions while concurrently inhibiting fouling adhesion, ultimately enhancing the coating’s longevity.

3.5. Anti-Fouling Through Multi-Factor Synergistic Effects

The attachment behavior of fouling deposits on heat transfer surfaces is influenced by the synergistic effects of surface characteristics such as the coating material’s surface roughness, surface free energy, wettability, and corrosion resistance, which collectively inhibit fouling deposition. While the inhibitory mechanisms of individual surface properties have been relatively well described and theorized in previous sections, the synergistic mechanism by which multiple factors jointly affect fouling attachment remains unclear. Moreover, there is limited reporting on which factor plays a dominant role in the synergistic anti-fouling process.

An increase in surface roughness can enhance pool boiling heat transfer by increasing the density of bubble nucleation sites on the heat transfer surface under pool boiling conditions [84,85]. This leads to the formation and detachment of numerous microbubbles on the surface. During bubble detachment, these microbubbles exert a “scrubbing” effect on the surrounding fouling deposits [78], which helps remove loosely adhered fouling from the surface. This scrubbing effect is particularly pronounced during the initial stage of fouling attachment when deposits are not yet firmly adhered. The vibration caused by bubble detachment further loosens the initial fouling, reducing its adhesion strength and promoting its removal. However, as fouling accumulation increases, it covers the heat transfer surface, reducing the density of bubble nucleation sites originally promoted by high surface roughness. Eventually, a dense fouling layer forms. Although surface roughness does not reduce the maximum fouling thermal resistance, the scrubbing effect prolongs the fouling induction period. Additionally, changes in surface roughness affect surface wettability, altering the interaction mode between the fouling medium and the surface. A hydrophobic surface can prevent complete contact between the fouling medium and the surface. Thus, the synergy between surface roughness and wettability [86] influences fouling attachment behavior and contributes to fouling suppression.

Surface free energy and wettability are closely interrelated factors. Among various surface properties, the magnitude of surface free energy reflects the hydrophilic or hydrophobic tendency of the surface. A low surface free energy results in a hydrophobic surface, which hinders contact between the fouling medium and the surface—a mechanism similar to that influenced by surface roughness. Moreover, a surface having low surface free energy exhibits weak adsorption toward fouling deposits due to the low interfacial energy between them, inhibiting the attachment and growth of fouling nuclei. Therefore, surface free energy and wettability exhibit a synergistic mechanism in affecting fouling attachment behavior. Based on Cheng’s research [28,29], it is inferred that the synergy between surface free energy and wettability may exhibit a threshold effect, which could vary for different types of fouling. Thus, investigating the synergistic inhibition of fouling attachment by surface free energy and wettability will be a key focus of future research.

The corrosion resistance of the coating protects it from corrosive ions in the fouling medium, helping maintain desirable surface roughness, surface free energy, and wettability over an extended period. During the interaction between the coating surface and the fouling medium, improved wettability reduces the contact area between the fouling medium and the surface, thereby preserving the coating’s corrosion resistance. Conversely, good corrosion resistance ensures the structural integrity of the coating surface, maintaining its wettability. Corrosive ions in the fouling medium cause damage in two ways: first, by attacking the coating surface, which alters surface properties and reduces anti-fouling performance; second, by corroding the substrate beneath the coating, which shortens the coating’s service life. Thus, the corrosion resistance and wettability of the coating not only synergistically inhibit fouling but also interact with each other, while also having a more direct relationship with surface roughness.

4. Conclusions

With the continuous expansion of industrial production scales, enterprise energy consumption has gradually increased. Effectively controlling production energy consumption is not only an important means to reduce production costs but also a crucial measure for energy conservation, emission reduction, and reducing carbon emissions during industrial processes. The attachment and accumulation of fouling deposits on industrial heat transfer surfaces severely impair the efficiency of heat exchange equipment and significantly increase energy consumption. Additionally, fouling escalates operational costs for enterprises. Studies indicate that in highly industrialized nations, fouling-related economic losses can reach 0.25% of GDP [87]. Anti-fouling coatings for industrial heat exchanger surfaces represent one technical approach to address fouling issues. Compared to other anti-fouling methods, coatings offer the advantages of lower investment, significant effectiveness, and ease of implementation. However, several research challenges remain for the practical application of anti-fouling coatings, as detailed below.

- (1)

- Mechanism of multi-factor synergistic effects of coating surface characteristics. Previous research indicates that coating surface characteristics—such as surface roughness, surface free energy, wettability, and corrosion resistance—can influence the attachment behavior of foulants from the heat transfer medium. However, most studies have focused on the effects of single factors. Research on the synergistic interactions of multiple factors is lacking, and the inhibitory synergistic effects of various surface characteristics on fouling attachment behavior are not yet fully understood, requiring further extensive study [88].

- (2)

- Theoretical and mechanistic research on fouling attachment behavior. The attachment mechanism during the initial stage of fouling is still not clear. In-depth research in this area could further explain the reasons for the different fouling induction periods observed with different anti-fouling coatings and provide essential theoretical support for developing new types of anti-fouling coatings.

- (3)

- Development and research of anti-fouling coatings with new material systems. As research progresses, composite anti-fouling coatings have become a hotspot, replacing single-type coatings. This is because single-type coatings often cannot perform effectively in diverse and complex fouling media environments, limiting their application potential.

- (4)

- Composite coatings are developed to handle such complex conditions by combining the advantages of multiple material systems, thus holding significant research value. However, the complexity of composite coating material systems presents challenges in how to organically integrate different materials, which will be a focus of future research. Additionally, the environmental friendliness of the material systems and preparation processes will also be a characteristic of new anti-fouling coating material systems.

- (5)

- Limited variety and inadequate research on anti-fouling coatings for high-temperature conditions. There are relatively few types of anti-fouling coatings suitable for high-temperature conditions, and research on their high-temperature anti-fouling mechanisms is insufficient. The attachment behavior of foulants in non-aqueous media is also not well understood. Further in-depth research on anti-fouling coatings under high-temperature conditions is necessary.

- (6)

- Durability and service life of coatings in complex working conditions. The durability and service life of anti-fouling coatings are significantly constrained under complex working conditions, greatly limiting their industrial application. Enhancing coating durability to meet the demands of various operational environments is one of the key research priorities for anti-fouling coatings.

- (7)

- Cost-effective, efficient, and large-area coating preparation. to meet the demands of industrial application, developing methods for the low-cost, high-efficiency, and large-area preparation of various types of anti-fouling coatings is a critical issue that needs to be addressed.

In summary, anti-fouling coatings for industrial heat exchangers are an effective means to address fouling problems in the field of industrial heat exchange. Conducting research in areas related to anti-fouling coatings, refining coating anti-fouling mechanisms, elucidating fouling attachment behavior, deeply exploring the advantages of traditional coatings in new application scenarios, and developing new coating material systems to address evolving fouling challenges hold significant scientific importance and application value.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.H. and Y.L.; resources, W.L., Z.D. and Z.F.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.H.; writing—review and editing, Z.H.; project administration, Z.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Teaching Quality and Teaching Reform Engineering Construction Project for Undergraduate Universities in Guangdong Province, grant number 710135181044.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Chen, Y.; Chen, X. Technology Development of Large-scale Heat Exchanger in China. J. Mech. Eng. 2013, 49, 134–143. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller-Steinhagen, H.; Malayeri, M.R.; Watkinson, A.P. Fouling of Heat Exchangers–New Approaches to Solve an Old Problem. Heat Transf. Eng. 2005, 26, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller-Steinhagen, H.; Malayeri, M.R.; Watkinson, A.P. Heat Exchanger Fouling, Environmental Impacts. Heat Transf. Eng. 2009, 30, 773–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, N.; Nagase, M.; Higa, M. Organic fouling behavior of commercially available hydrocarbon–based anion–exchange membranes by various organic–fouling substances. Desalination 2012, 296, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoenitz, M.; Grundemann, L.; Augustin, W.; Scholl, S.J.C.C. Fouling in microstructured devices: A review. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 8213–8228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, N. Thinking about Heat Transfer Fouling, A 5 × 5 Matrix. Heat Transf. Eng. 1983, 4, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Förster, M.; Bohnet, M. Modification of molecular interactions at the interface crystal/heat transfer surface to minimize heat exchanger fouling. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2000, 39, 697–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugama, T.; Gawlik, K. Anti–silica fouling coatings in geothermal environments. Mater. Lett. 2002, 57, 667–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukulka, D.J.; Leising, P. Evaluation of heat exchanger surface coatings. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2010, 30, 2333–2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malayeri, M.R.; Al-Janabi, A.; Müller-Steinhagen, H. Application of nano–modified surfaces for fouling mitigation. Int. J. Energy Res. 2009, 33, 1101–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldani, V.; Sergi, G.; Pirola, C.; Bianchi, C.L. Use of a sol–gel hybrid coating composed by a fluoropolymer and silica for the mitigation of mineral fouling in heat exchangers. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2016, 106, 427–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldani, V.; Bianchi, C.L.; Biella, S.; Pirola, C.; Cattaneo, G. Perfluoropolyethers coatings design for fouling reduction on heat transfer stainless–steel surfaces. Heat Transf. Eng. 2015, 37, 210–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, B.; Yang, W.; Xu, Z. Anti–scale and anti–corrosion properties of PDA/PTFE superhydrophobic coating on metal surface. Chem. Ind. Eng. Prog. 2023, 42, 4315–4321. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Wang, H.; Zhang, W.; Li, H.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, Y. Effects of modified celatom and PDMS on antiscaling and corrosion resistance of epoxy coatings. China Surf. Eng. 2019, 32, 102–108. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Q.; Liu, Y. Investigation of graded Ni–Cu–P–PTFE composite coatings with antiscaling properties. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2004, 229, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Luo, X.; Jia, L. Preparation of Zn–Ni/PTFE composite coatings and their corrosion resistance and scale inhibition performance in simulated wastewater. Plat. Finish. 2023, 45, 15–22. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Q.; Liu, Y.; Wang, C.; Wang, S.; Müller-Steinhagen, H. Effect of surface free energy on the adhesion of biofouling and crystalline fouling. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2005, 60, 4858–4865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Wang, S.; Müller-Steinhagen, H. Tailored surface free energy of membrane diffusers to minimize microbial adhesion. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2004, 230, 371–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Janabi, A.; Malayeri, M.R.; Müller-Steinhagen, H. Experimental fouling investigation with electroless Ni–P coatings. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2010, 49, 1063–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Janabi, A.; Malayeri, M.R.; Müller-Steinhagen, H. Minimization of CaSO4 deposition through surface modification. Heat Transf. Eng. 2011, 32, 291–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Zou, Y.; Cheng, L.; Liu, W. Effect of the microstructure on the anti–fouling property of the electroless Ni–P coating. Mater. Lett. 2008, 62, 4283–4285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Zou, Y.; Cheng, L.; Li, J.; Liu, W. Effect of phosphorus content on anti–fouling and anti–corrosion properties of electroless Ni–P deposition. J. Synth. Cryst. 2008, 37, 1210–1214. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Y.H.; Chen, S.S.; Jen, T.C.; Zhu, Z.C.; Peng, Y.X. Effect of copper addition on the properties of electroless Ni–Cu–P coating on heat transfer surface. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2014, 76, 2209–2215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.H.; Chen, H.Y.; Zhu, Z.C.; Jen, T.C.; Peng, Y.X. Experimental study on the anti–fouling effects of Ni–Cu–P–PTFE deposit surface of heat exchangers. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2014, 68, 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Song, F.; Xu, Z.; Jia, Y. Study on the effect of Ni–P–PTFE composite coating on the deposition characteristics of particulate fouling. CIESC J. 2022, 73, 4594–4602. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Z.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, L. The experimental investigation of cooling water microbial fouling characteristics on modified heat exchanger surface. J. Eng. Thermophys. 2014, 35, 2478–2481. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Z.; Bai, W.; Liu, Z. Iron bacteria fouling and corrosion properties effect on modified surface of electroless Ni–P coating. J. Northeast. Dianli Univ. 2016, 36, 57–61. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Xing, W.; Zhao, B.; Xu, Z. Analysis of composite modified surface inhibiting particle fouling accumulation characteristics. CIESC J. 2022, 73, 4928–4937. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Li, S.; Xing, W.; Xu, Z. Characteristics of microbial fouling on Ni–P–(nano)TiO2 composite coating of plate heat exchanger. CIESC J. 2020, 71, 3535–3544. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, M.Y.; Wang, H.; Wang, Y. Enhancing flow boiling and antifouling with nanometer titanium dioxide coating surfaces. AIChE J. 2007, 53, 1075–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, L.; Liu, M. Antifouling and enhancing pool boiling by TiO2 coating surface in nanometer scale thickness. AIChE J. 2007, 53, 3062–3076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.L.; Liu, M.Y. Pool boiling fouling and corrosion properties on liquid–phase–deposition TiO2 coatings with copper substrate. AIChE J. 2011, 57, 1710–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Liu, M.; Hui, L. CaCO3 fouling on microscale–nanoscale hydrophobic titania–fluoroalkylsilane films in pool boiling. AIChE J. 2013, 59, 2662–2678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Liu, M.; Hui, L. Observations and mechanism of CaSO4 fouling on hydrophobic surfaces. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2014, 53, 3509–3527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, L.; Liu, M.; Cai, Y.; Lv, Y. Fouling resistance on chemically etched hydrophobic surfaces in nucleate pool boiling. Chem. Eng. Technol. 2015, 38, 416–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Liu, M.; Sun, X.; Wang, J.; Zhu, J. Antifouling and anticorrosion behaviors of modified heat transfer surfaces with coatings in simulated hot–dry–rock geothermal water. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2018, 132, 740–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.; Liu, M.; Zhou, W. Fouling and Corrosion Properties of SiO2 Coatings on Copper in Geothermal Water. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2012, 51, 6001–6017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reza Malayeri, M.; Evangelidou, M. Enhanced Heat Transfer and Fouling Propensity of DLC Coated Smooth and Finned Tubes during External Nucleate Boiling. J. Heat Transf.–Trans. ASME 2016, 138, 081502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Wang, X. Heat transfer surfaces coated with fluorinated diamond–like carbon films to minimize scale formation. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2005, 192, 77–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.R.; Liu, C.S.; Jie, X.H.; Lian, W.Q.; Luo, S.T. Preparation of anti–fouling heat transfer surface by magnetron sputtering a–C film on electrical discharge machining Cu surface. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2019, 369, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Sun, M.; Liu, Z.; Wang, B.; Di, H. Properties of the iron bacteria biofouling on Ni–P–rGO coating. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, K.; Kazi, S.N.; Zubir, M.N.M.; Wong, K.; Yusoff, S.A.B.M.; Khan, W.A.; Alam, M.S.; Abdullah, S.; Shukri, M.H.B.M. Mitigation of CaCO3 Fouling on heat exchanger surface using green functionalized carbon nanotubes (Gfcnt) coating. Therm. Sci. Eng. Prog. 2023, 42, 101878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, K.; Kazi, S.N.; Zubir, M.N.B.M.; Khan, W.A.; Nawaz, R.; Hasnain, S.U.; Borhanudin, A.R. Performance evaluation of green synthesized graphene nanoplatelets–multiwall carbon nanotubes hybrid nanofluids for the retardation of mineral fouling and its environmental benefits. Carbon 2025, 238, 120243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Wang, D.; Fan, Z.; Chen, Y.; Li, S.; Mo, C. Fabrication of Fe–Al coatings with micro/nanostructures for antifouling applications. Coatings 2020, 10, 902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, K.; Kazi, S.N.; Zubir, M.N.M.; Abd Razak, B.; Wong, K.; Wong, Y.H.; Khan, W.A.; Abdullah, S.; Alam, M.S. Investigation of zirconium (Zr) coated heat exchanger surface for the enhancement of heat transfer and retardation of mineral fouling. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2023, 153, 105246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oon, C.S.; Kazi, S.N.; Hakimin, M.A.; Abdelrazek, A.H.; Mallah, A.R.; Low, F.W.; Tiong, S.K.; Badruddin, I.A.; Kamanger, S. Heat transfer and fouling deposition investigation on the titanium coated heat exchanger surface. Powder Technol. 2020, 373, 671–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, K.; Zhang, X.; Huang, X.; Oliveira, E.F.; Guo, H.; Zhai, T.; Wang, W.; Alvarez, P.J.J.; Elimelech, M.; Ajayan, P.M.; et al. Ultrahigh resistance of hexagonal boron nitride to mineral scale formation. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 4523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, M.L.; Qian, H.J.; Fan, W.H.; Wang, C.J.; Yuan, R.X.; Gao, Q.H.; Wang, H.Y. Surface lurking and interfacial ion release strategy for fabricating a superhydrophobic coating with scaling inhibition. Pet. Sci. 2022, 19, 3068–3079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.L.; Qian, H.J.; Yuan, R.X.; Zhao, D.Y.; Huang, H.C.; Wang, H.Y. EDTA interfacial chelation Ca2+ incorporates superhydrophobic coating for scaling inhibition of CaCO3 in petroleum industry. Pet. Sci. 2021, 18, 951–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, O.; Nylander, T.; Rosmaninho, R.; Rizzo, G.; Yiantsios, S.; Andritsos, N.; Karabelas, A.; Müller-Steinhagen, H.; Melo, L.; Boulangé-Petermann, L.; et al. Modified stainless steel surfaces targeted to reduce fouling–surface characterization. J. Food Eng. 2004, 64, 63–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keysar, S.; Semiat, R.; Hasson, D.; Yahalom, J. Effect of Surface Roughness on the morphology of calcite crystallizing on mild steel. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1994, 162, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, C.; Peng, Z.; Day, T.; Yan, X.; Bai, X.; Yuan, C. Experimental observation of surface morphology effect on crystallization fouling in plate heat exchangers. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 2011, 38, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zettler, H.U.; Wei, M.; Zhao, Q.; Müller-Steinhagen, H. Influence of surface properties and characteristics on fouling in plate heat exchangers. Heat Transf. Eng. 2005, 26, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, B. Influence of heat transfer surface characteristics on fouling induction period. Energy Conserv. Technol. 2008, 26, 15–17, 22. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Zou, Y.; Zhao, L.; Liu, W.; Cheng, L. Investigation of adhesion of CaCO3 crystalline fouling on stainless steel surfaces with different roughness. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 2011, 38, 730–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, M.; Augustin, W.; Scholl, S. Adhesion of single crystals on modified surfaces in crystallization fouling. J. Cryst. Growth 2012, 361, 152–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Liu, J. Composition analysis and kinetic modeling of crystallization fouling in cooling seawater. Chem. Ind. Eng. Prog. 2015, 34, 3179. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Muthu, M.; Gopal, J.; Chun, S.; Lee, S.K. Hydrophobic bacteria–repellant graphene coatings from recycled pencil stubs. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2018, 43, 241–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Y.; Liu, M.; Xu, Y. Corrosion and fouling behaviors on modified stainless steel surfaces in simulated oilfield geothermal water. Prot. Met. Phys. Chem. Surf. 2018, 54, 526–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Y.; Liu, M. Corrosion and fouling behaviours of copper–based superhydrophobic coating. Surf. Eng. 2018, 35, 542–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Ye, H.; Zhao, X.; Li, P.; Chen, H.; Liu, H.; Zhang, H.; Li, W. Strategy for fabricating degradable low–surface–energy cross–linked networks with excellent anti–fouling properties. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2025, 17, 3995–4008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Janabi, A.; Malayeri, M.R. A criterion for the characterization of modified surfaces during crystallization fouling based on electron donor component of surface energy. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2015, 100, 212–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Janabi, A.; Malayeri, M.R. Innovative non–metal heat transfer surfaces to mitigate crystallization fouling. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2019, 138, 384–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Janabi, A.; Malayeri, M.R.; Guillén-Burrieza, E.; Blanco, J. Field evaluation of coated plates of a compact heat exchanger to mitigate crystallization deposit formation in an MD desalination plant. Desalination 2013, 324, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matjie, R.; Zhang, S.; Zhao, Q.; Mabuza, N.; Bunt, J.R. Tailored surface energy of stainless steel plate coupons to reduce the adhesion of aluminium silicate deposit. Fuel 2016, 181, 573–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Chen, Z.; Li, W.; Ding, Z.; Xu, Z. Composite fouling characteristics on Ni–P–PTFE nanocomposite surface in corrugated plate heat exchanger. Heat Transf. Eng. 2021, 42, 1877–1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Zhao, Q. The CQ ratio of surface energy components influences adhesion and removal of fouling bacteria. Biofouling 2011, 27, 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stärk, A.; Krömer, K.; Loisel, K.; Odiot, K.; Nied, S.; Glade, H. Impact of tube surface properties on crystallization fouling in falling film evaporators for seawater desalination. Heat Transf. Eng. 2016, 38, 762–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Lamb, R.; Lewis, J. Engineering nanoscale roughness on hydrophobic surface–preliminary assessment of fouling behaviour. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 2005, 6, 236–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidema, R.; Toyoda, T.; Suzuki, H.; Komoda, Y.; Shibata, Y. Adhesive behavior of a calcium carbonate particle to solid walls having different hydrophilic characteristics. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2016, 92, 603–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaleghi, H.; Eshaghi, A. Fabrication of superhydrophobic micro–nano structure Al2O3–13% TiO2/PTFE coating with anti–fouling and self–cleaning properties. Surf. Interfaces 2020, 20, 100559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wu, L.; Yuan, Z.; Chen, W. Characterization of water–based anti–corrosion and anti–fouling coating in the heat exchanger tube of gas water heater. Mater. Sci. 2024, 30, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Sun, N.; Ju, Y.; Li, J.; Chen, Z. Study on the effect of surfaceproperties of non–metallic materials on the growth mechanism of crystallization fouling. Processes 2023, 11, 2232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, B.; Hamazaki, T.; Ma, W.; Iwata, N.; Hidaka, S.; Takahara, A.; Takahashi, K.; Takata, Y. Enhanced pool boiling of ethanol on wettability–patterned surfaces. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2019, 149, 325–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, D.; Yang, D.; Dong, C.; Chen, C.; Jiang, H.; Li, Q.; Cheng, J.; Lu, G.; Liu, D. Enhancement of pool boiling heat transfer by laser texture–deposition on copper surface. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2024, 661, 160015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esawy, M.; Malayeri, M.R. Modeling of CaSO4 crystallization fouling of finned tubes during nucleate pool boiling. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2017, 118, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.R.; Liu, C.S.; Gao, H.Y.; Jie, X.H.; Lian, W.Q. Experimental study on the anti–fouling effects of EDM machined hierarchical micro/nano structure for heat transfer surface. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2019, 162, 114248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, J.; Shang, Z.; Feng, C.; Gu, J.; Ye, M.; Zhao, R.; Liu, D.; Meng, J.; Wang, S. Wettability–driven synergistic resistance of scale and oil on robust superamphiphobic coating. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2024, 35, 109623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, R.; Wang, Y.; Meng, J.; Chen, W.; Wang, B.; Xu, X.; He, X.; Yang, H.; Li, K.; Wang, S. Sustainable scale resistance on a bioinspired synergistic microspine coating with a collectible liquid barrier. Mater. Horiz. 2022, 9, 2872–2880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, R.; Chen, Z.; Yang, H.; Wang, Y.; Wang, S.; Meng, J. Scalable and robust bio–inspired organogel coating by spraying method towards dynamic anti–scaling. Chem. Res. Chin. Univ. 2023, 39, 127–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.H.; Zou, Y.; Cheng, L.; Liu, W. Effect of the microstructure on the properties of Ni–P deposits on heat transfer surface. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2009, 203, 1559–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zou, Y.; Cheng, L.; Zhao, L.; Zhu, Z. Effect of surface modification onanti-fouling properties of heat exchangers. J. Eng. Thermophys. 2009, 30, 1528–1530. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, F.; Liu, M.; Zhang, S.; Zhao, Q. Corrosion and fouling of different coatings in geothermal water. Acta Energiae Solaris Sin. 2015, 36, 510–516. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Messer, M.; Anderson, K.; Zhang, X.; Abbasi, B. Effect of surface roughness on mixed salt crystallization fouling in pool boiling. Desalination Water Treat. 2022, 274, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjan, A.; Priy, A.; Ahmad, I.; Pathak, M.; Khan, M.K.; Keshri, A.K. Heat transfer characteristics of pool boiling with scalable plasma–sprayed aluminum coatings. Langmuir 2023, 39, 6337–6354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Z.R.; Luo, S.T.; Liu, C.S.; Jie, X.H.; Lian, W.Q. Hierarchical micro/nano structure surface fabricated by electrical discharge machining for anti–fouling application. J. Mater. Res. Technol.—JMRT 2019, 8, 3878–3890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Gu, A.; Ding, J.; Shen, Z. Investigation of induction period and morphology of CaCO3 fouling on heated surface. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2002, 57, 921–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geddert, T.; Augustin, W.; Scholl, S. Induction time in crystallization fouling on heat transfer surfaces. Chem. Eng. Technol. 2011, 34, 1303–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.