Abstract

The escalating global heatwave crisis demands urgent advancements in high-efficiency, energy-saving cooling technologies. Radiative cooling (RC) paints, capable of passively dissipating heat through the atmospheric transparent window (ATW, 8–13 μm) without external energy input, have emerged as a groundbreaking solution for sustainable thermal management. This perspective advocates for a paradigm shift in the field from solely focusing on optical performance optimization to comprehensive system design that simultaneously achieves high cooling power, industrial-scale manufacturability, long-term environmental durability, and customizable aesthetics. We systematically analyzed the fundamental design principles of RC paints, reviewed the construction strategy of the state-of-the-art RC paints, advanced multi-band spectral engineering, synergistic integration with complementary cooling technologies, and robust structural configurations for large-scale deployment. Addressing critical challenges for commercialization, we also proposed targeted solutions, including enhanced application-specific durability, cost-effective production scaling, and multifunctional system integration. This work provides a strategic roadmap to accelerate the transition of RC paints from laboratory prototypes to ubiquitous real-world applications, ultimately contributing to a sustainable future with improved thermal comfort.

1. Introduction

Global warming and the increasingly frequent extreme climate events pose unprecedented challenges to modern society [1,2]. Rising temperatures have dramatically amplified cooling demands in buildings [3,4], cold-chain storage [5], personal thermal comfort [6,7], aerospace [8], and outdoor electrical equipment management [9]. Conventional cooling methods, predominantly reliant on energy-intensive air conditioning systems, not only consume enormous amounts of electricity but also contribute significantly to greenhouse gas emissions, creating a vicious cycle of climate feedback [10,11]. This pressing scenario underscores the urgent need for sustainable cooling alternatives that minimize both energy consumption and carbon footprint. Objects dissipate heat continuously and spontaneously by infrared radiation (IR) [12]. Radiative cooling (RC) is a groundbreaking solution to transfer heat into outer space (~3 K), which is an ultra-cold heat sink, by IR and achieve passive sub-ambient cooling (i.e., temperature below the ambient air) without any external energy input. This process takes advantage of the atmospheric transparent window (ATW, typically 8–13 μm), a wavelength range in which the Earth’s atmosphere is nearly transparent to IR so that photons can escape directly to outer space [13,14,15]. This innovative approach presents a paradigm-shifting opportunity to substantially reduce global cooling energy demands while simultaneously addressing environmental concerns.

Paints have emerged as highly promising RC composites, demonstrating effective nighttime sub-ambient cooling capabilities as early as the 1970s due to their intrinsically high mid-infrared radiation (MIR) emissivity, mainly located in 2.5–25 μm [16]. However, conventional RC paints were ineffective for daytime sub-ambient cooling owing to their insufficient solar reflectance (Rsolar), which critically impaired their solar heat-blocking capacity [17]. This fundamental limitation primarily arises from the lack of optimized photonic design tailored for the solar spectrum, including light with a wavelength range from 0.3 to 2.5 μm [18]. A breakthrough occurred in 2014 when Fan et al. pioneered a multilayer photonic crystal structure, successfully achieving sub-ambient cooling under direct sunlight [19]. Achieving high Rsolar (>0.9) is paramount for sub-ambient cooling performance, as it enables the effective rejection of intense solar irradiance, sometimes 1000 W/m2, that far exceeds the theoretical maximum net radiative cooling power (Pnet), approximately 180 W/m2 [20]. Recent years have witnessed remarkable progress in enhancing both the Rsolar and the MIR emissivity, particularly within the atmospheric transparency window (ɛATW), through sophisticated photonic architecture design and nanoscale material engineering, driving the development of the state-of-the-art RC paints (Figure 1a) [21].

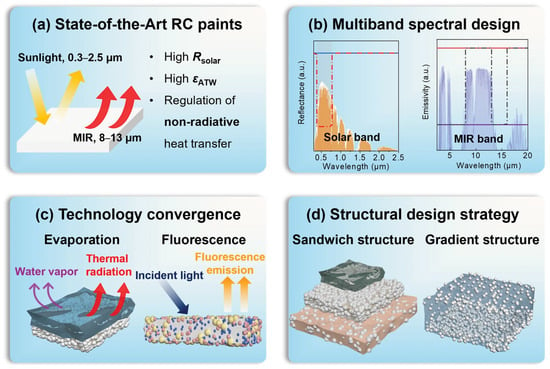

Figure 1.

The research framework of RC paints. (a) The state-of-the-art RC paints. (b) Multiband spectral design strategy of solar and MIR bands. The colored lines present the typical reflective curves (left) and emissive curves (right) of RC paints. The colored area represents the ASTM G-173-03 reference spectrum (orange) and the transmission of the atmospheric transparent window (purple). (c) The technology convergence for the improvement of Pnet. (d) The structure design for a large-scale application.

It should be emphasized that the innovative research on RC paints aims not merely to achieve near-perfect optical performance but also to enable their broad practical applications. Given the rapidly expanding application scenarios, developing multi-band spectral design strategies encompassing both solar and MIR bands is crucial to fulfill diverse requirements such as cooling efficiency, aesthetic requirements, and thermal flux regulation (Figure 1b). Moreover, integrating complementary cooling technologies with RC systems can significantly enhance Pnet through synergistic effects (Figure 1c). RC paints are especially attractive for large-scale deployment because they can be produced and applied using conventional coating processes, such as spray, blade, and roll coating [22]. However, outdoor service demands that they withstand UV radiation, temperature fluctuations, moisture, pollutants, and mechanical wear over long periods. Simple one-layer designs often cann‘t simultaneously satisfy high cooling performance and stringent durability requirements, making structural optimization a key design dimension (Figure 1d).

In this perspective, we contended that the future of RC paints hinges on closing the divide between their exceptional optical performance in laboratory settings and practical applications. We comprehensively examined recent advancements in RC paints through this viewpoint and provided a critical evaluation of design strategies spanning from fundamental principles to real-world implementation. Our analysis emphasized the pioneering design approaches that are accelerating RC paints’ evolution into a pervasive, zero-energy cooling solution poised to contribute significantly to a sustainable future.

2. The Fabrication Strategies of State-of-the-Art RC Paints

Extensive research has focused on achieving near-ideal RC parameters, targeting Rsolar and ɛATW values approaching 1 for higher Pnet based on a one-dimensional steady heat transfer model [23]. They are not only determined by macroscopic optical constants, but also by the underlying chemical and optoelectronic properties of the coating components, as well as the morphological structures. Therefore, both of the components and photonic structures should be well designed during the construction process of RC paints. Photonic structures (i.e., the designed micro-/nanostructured morphology to scatter light) optimized for enhancing the Rsolar of RC coatings primarily fall into two categories: porous structure and random particle structure. Air voids, characterized by their low refractive index (nair = 1), acted as highly efficient scatterers by large n contrast with matrix materials, thereby maximizing scattering efficiency [17]. Hierarchical porous polymer structures have demonstrated enhanced Rsolar performance owing to their broad distribution of air void diameters and optimal void density [7,24]. Typical dry coating fabrication techniques of porous structure encompass phase-separation [22,23,24], templating [25,26,27], and solvent displacement methods [28]. While the polymer framework provides strong MIR emission owing to its abundant vibrational/absorption of chemical bonds, several practical issues remain, including the loss of mechanical strength at high porosity, the release of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) during solvent-based processing, limited control over pore morphology, and the overall complexity of the fabrication procedures. These constraints currently hinder practical large-scale deployment.

Random particle structures consist of binders (typically polymer resins), particles, solvents, and additives. Its composition closely resembles that of commercial paints, ensuring compatibility with standard manufacturing processes such as mixing, dispersion, grinding, thinning, and packaging. To enhance the Rsolar, the components were meticulously engineered based on the intrinsic properties of particles (e.g., shapes, sizes [29,30,31,32], bandgaps [33,34,35,36,37], and structures [38,39]), binder characteristics (e.g., optical constants, surface wettability, and durability [40,41]), and processing parameters (e.g., particle volume concentration (PVC) [42], coating thickness [43], and application conditions [44]). Meanwhile, the chemical properties of components are also well-selected. The absorptive/emissive peak locations of chemical bond types and functional groups were selected for high ɛATW. The polymers contained chemical bonds, such as C−F, C−O−C, Si−O−Si bonds, and so on, are favorable for selective high emissivity in the ATW [45]. The film-forming properties, such as cross-linking density, glass transition temperature, and substrate adhesion, should also be considered for real applications [46,47]. Additionally, the choice of solvents (e.g., water or organic solvents) and additives must be carefully optimized, as they critically influence key paint properties, including storage stability, viscosity, wetting, leveling, film formation, drying time, and adhesion [48,49]. In recent years, water-based RC paints have gained prominence due to their environmental benefits, aligning with global sustainability policies [50,51,52]. Notably, the strategic selection of additives plays a pivotal role in enhancing the performance of water-based formulations [53,54,55]. Advances in optical engineering have enabled RC paints to achieve exceptionally high Rsolar, higher than 0.95, and high ɛATW [33]. However, random particle structures still face challenges to achieve a balance between perfect optical parameters and superior mechanical properties. Achieving optimal scattering often requires high PVC, usually exceeding 60%, which compromises mechanical strength and accelerates chalking. Conversely, reducing PVC drastically diminishes Rsolar. This trade-off highlights a critical challenge, necessitating innovative scatterer designs or high scattering efficiency pigments to achieve high performance at lower PVC [56].

To further improve the cooling capacity of RC paints, it is not sufficient to optimize their radiative properties alone. Non-radiative heat exchange with the environment–mainly conduction and convection between the coating, the substrate, and the ambient air—must also be explicitly considered because it can significantly influence the net cooling power, especially in application scenarios with inner or outer heat sources [57]. The regulation of thermal conductivity and the mitigation pathway assisted RC paints to synergistically cool down objects [58,59,60]. Additionally, machine learning presents a promising approach for navigating the complex multi-parameter formulation space, enabling simultaneous optimization of optical, mechanical, and application properties.

3. Multiband Spectral Design

While white RC paints are high-performance radiative coolers, their potential glare and aesthetic versatility require advanced spectral design in both the solar band and MIR band. For the solar band, a selective reflection mode (i.e., colored or transparent in the visible light and highly reflective in the ultraviolet (UV) and near-infrared (NIR) bands) is required to adapt to aesthetic, light, and distinctive demands. Vibrantly colored RC paints exhibit aesthetic compatibility. However, achieving an optimal balance between coloration and thermal management requires careful consideration through precise optical structural design. Various strategies for narrowband absorption were proposed, including structure coloration [61], subtractive coloration [62], decreased optical path [63], fluorescent dyes [64], etc. Nevertheless, the conflicts between simple fabrication, vivid coloration, and achieving a high Rsolar become a significant challenge, necessitating the development of innovative approaches for colorful RC paints. Transparent RC coatings are designed for devices such as vehicles, electronic devices, and photovoltaic cells with necessary light control [65]. Highly visible transmissive polymers, like poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA), polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) [21], and polyethylene terephthalate (PET) [66], can be directly applied onto substrates as standalone RC coatings or used as binders in particle–polymer composite RC paints. These polymers provide a continuous matrix that ensures good adhesion to the substrate and maintains high visible transparency. In the latter case, particles with a refractive index similar to that of the polymer matrix (n ≈ 1.4) are typically selected to minimize parasitic scattering [67], while the characteristic vibrational modes of the polymer backbones (e.g., C–O, C=O, and Si–O–Si) contribute strong MIR emissivity beneficial for radiative cooling [68]. However, the transparent coatings are difficult to filter sunlight, especially in the NIR band. The blocking of NIR radiation in visibly transparent systems is usually achieved by integrating additional transparent optical components that selectively reflect or scatter NIR light, such as indium tin oxide (ITO) glass [69,70] or stacked photonic crystals [71], which increases the manufacturing cost and process. Therefore, simple approaches based on particle mixing, where NIR-selective particles or pigments are dispersed into a transparent polymer matrix, are highly desired to construct transparent RC coatings with built-in light-filtering capability [72].

Based on the MIR responsive characteristic, the RC paints can be categorized into three categories: selective emitters with a high emissivity only in the ATW band, broadband emitters with a high emissivity in the MIR band, and low-emissive emitters with a low emissivity in the MIR band. Selective emitters are theoretically attractive for maximizing sub-ambient cooling temperature reduction by minimizing atmospheric parasitic heat absorption [13]. Zhou et al. designed a selective emissive RC paint with CaCO3 microparticles and a bottom porous polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) structure based on a machine learning assisted method [73]. Nonetheless, the practical implementation of selective RC paints remains challenging, primarily due to the contradiction between the rigorously minimized polymer content for spectral selectivity and the demand for enough binders to ensure mechanical durability. Actually, most RC paints usually exhibit broadband emission with a higher Pnet for cooling down objects with an above-ambient temperature [9]. Meanwhile, the low-emissivity RC paints provide another effective strategy for energy-saving by reducing heat gain and loss flux. Two prevalent structures have been proposed for preparing low-emissivity RC paints [20]. The first structure is a bilayer structure with a MIR transparent layer as the top layer and a high IR reflective layer composed of metal flakes (e.g., Al) as the bottom layer [3,74]. The second structure is one with a transparent low-emissive layer as the top layer and a high solar reflective layer as the bottom layer [75]. These paints are promising temperature-preserving coatings by mitigating undesired heat exchange between the coated substrate and the surrounding environment by minimizing heat radiation flux when exposed to external heat or cold environments. Except for that, various mixed spectral designs, including selective emission-transmission and selective emission-reflection, have been shown to effectively mitigate the urban heat island effect (UHI), which is the phenomenon that densely built urban areas exhibit higher surface and air temperatures than their surrounding rural regions [76,77]. But their complex fabrication processes rendered them less compatible with scalable RC paint manufacturing. For broadened application, the focus of spectral design is moving from static to dynamic and adaptive properties. The ultimate goal is no longer just a high-performance cooler, but an intelligent thermal skin that can modulate its optical properties in response to environmental stimuli (e.g., temperature, humidity) for annual net energy saving performance [78,79].

4. The Technology Convergence with RC Paints for Enhanced Pnet

Significant progress has been achieved in state-of-the-art RC paints and multi-band synergistic strategies to ensure high-performance cooling across diverse applications. However, the practical cooling efficiency of RC paints is still limited by specific environmental conditions and prevailing weather patterns. The Pnet of RC paints reaches ~180 W/m2 under clear skies and drops to ~40 W/m2 when applied to vertical surfaces [76]. In high-humidity or cloudy conditions, atmospheric transparency reduction further restricts Pnet to ~20 W/m2 [80]. Consequently, integrating additional heat dissipation mechanisms is critical for enhancing Pnet to compensate for the extra absorptive sunlight or exhibited radiative capacity. Evaporative cooling, leveraging water’s high latent heat (2256 J/g), provides a high-power cooling pathway. At night, when the surface temperature drops, water vapor from the ambient air condenses on the coating and is stored within its porous or hydrogel matrix. During the daytime, this stored water gradually evaporates, extracting a large amount of heat from the coating and underlying substrate through the liquid–vapor phase change, thereby lowering the surface temperature [81,82]. Hydrogels, with their exceptional moisture-absorption capacity, are ideal for such applications [83,84]. In practical applications, such hydrogels are typically applied onto roofs or building facades by casting, blade-coating, or spraying aqueous precursor formulations onto the substrate, followed by in-situ gelation/crosslinking, though improvements in long-term durability and building-surface adaptability remain necessary [82]. Fei et al. developed a meta-cement RC paint incorporating porous calcium silicate hydrate (C−S−H) networks, combining RC with reverse evaporative cooling. This material achieved a ~5 °C temperature reduction compared with conventional RC paints in humid climates while maintaining robust outdoor durability [85]. Nevertheless, the sustained evaporative cooling effect depends on cyclical moisture absorption and evaporation, reducing its efficacy in arid, hot environments. Additionally, water-induced substrate degradation poses challenges for long-term use.

The other enhanced strategy involves overcoming the limitations of Rsolar. Fluorescence, an emerging compensatory cooling technology, transforms high-energy short-wavelength solar radiation (e.g., UV light) into longer-wavelength emissions, releasing energy externally. This approach can boost Rsolar by more than 100% while reducing overall sunlight absorption [86]. Typical fluorescent components include inorganic phosphors (e.g., rare-earth-doped oxides) [87], and semiconductor quantum dots [88], which are chosen to exhibit strong absorption in the near-UV/blue region and high quantum yield in the visible or near-infrared band. Gong et al. developed a photoluminescent RC coating to improve the efficiency of bifacial photovoltaic (PV) panels [89]. Additionally, fluorescent dyes were proposed for use in colorful RC paint formulations, mitigating light-related coloration effects to strike an optimal balance between aesthetic appeal and cooling performance [90]. Other cooling technologies, including phase-change microcapsules (PCMs), fluid cooling systems, and engineered concentrated systems, have also been leveraged to drive breakthroughs in Rsolar.

5. The Structural Design Strategy for Practical Applications

Coatings are subjected to complex environmental conditions to test their long-term durability. In service, outdoor RC coatings are simultaneously exposed to multiple environmental stressors, including strong UV irradiation, large day–night temperature fluctuations, moisture and humidity, airborne pollutants, and mechanical abrasion, all of which together govern and often accelerate coating degradation and loss of RC performance [91]. Therefore, the polymer matrix and organic pigments may undergo photodegradation and thermo-oxidative aging, involving radical-mediated chain scission, crosslinking, and chromophore oxidation, which can lead to gloss loss, yellowing, and reduced Rsolar [92]. Moisture and pollutants can further induce hydrolysis of ester linkages in acrylics or dissolution and recrystallization of carbonate-based fillers, altering the microstructure and emissive properties [93,94]. However, conventional single-layer RC coatings often fail to satisfy these demanding requirements, particularly when confronting the inherent interfacial complexities in such applications. For instance, coatings must demonstrate robust adhesion to the underlying substrate. An excessively high PVC over 60%, which exceeded the critical pigment volume concentration (CPVC), decreases binder content, leading to interfacial stress concentration and potential micro-crack formation [33,95]. The CPVC is the pigment content at which the binder just fills the voids between adjacent particles, and any further increase in pigment inevitably introduces inter-particle voids and continuous pores. As a result, once the pigment loading exceeds the CPVC, a highly porous network is formed that greatly enhances light scattering and Rsolar, at the expense of reduced mechanical strength, increased water uptake, and poorer long-term durability [96]. Below the CPVC, the coating remains dense, with good mechanical integrity and low permeability, but the limited multiple scattering leads to only moderate Rsolar. Consequently, the optimal structural approach has evolved to strike a balance between durability and superior cooling performance.

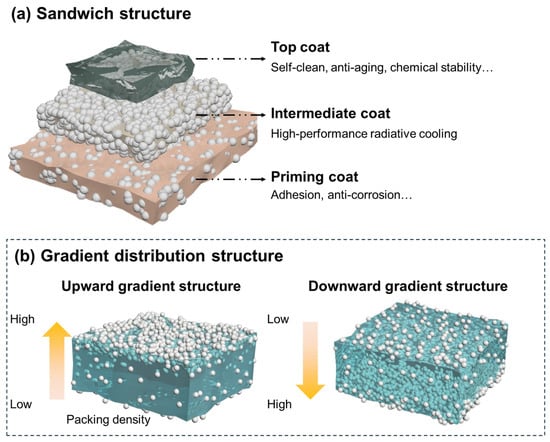

The sandwich multilayer structure is a widely adopted and highly effective strategy, particularly for commercialized RC paints. This architecture typically comprises three functional layers: the top coat, intermediate coat, and priming coat (Figure 2a) [97,98,99]. In this architecture, each layer serves a distinct function within the radiative cooling system. The top layer requires exceptional durability to withstand environmental stressors like yellowing, aging, mechanical abrasion, and surface contamination while maintaining long-term protective performance. It is commonly fabricated from optically dense, high-transparency materials (e.g., finishing layers [100], glass [101]) to preserve optical properties. The intermediate layer delivers the primary RC functionality through its high Rsolar and a high PVC. Finally, the priming layer acts as a vital adhesive bridge between the coating system and substrate, demanding robust adhesion and superior substrate wettability. In specialized applications (e.g., chemical tanks, marine settings), this layer must also incorporate anti-corrosive properties. Interlayer compatibility critically governs the coating’s overall performance, as incompatible material combinations may induce interfacial delamination, shrinkage voids, or other defects. While the sandwich structure enables multifunctional integration through layer-specific optimization, our analysis reveals persistent challenges in reconciling high radiative cooling efficiency with practical implementation. Key limitations include: (1) increased manufacturing complexity and cost due to multilayer deposition, alongside elevated interfacial failure risks [74]; (2) inherent solar absorption by organic top-coat materials (e.g., acrylic or polyurethane finishing layers) containing UV-active chromophores such as carbonyl (C=O) and conjugated C=C groups, whose π–π* and n–π* electronic transitions absorb in the UV–visible range, and NIR-active polar bonds (e.g., O–H, C–H, N–H) whose vibrational overtones and combination bands absorb in the NIR band [102,103]. Under prolonged UV exposure, thermal/oxidative aging, and moisture ingress, additional carbonyl and conjugated structures can be generated via photo-oxidation, hydrolysis, and chain scission, further increasing broadband solar absorptance and, together with reduced mechanical strength, compromising the overall solar reflectance and long-term RC performance [104].

Figure 2.

The structural design of durable RC paints. (a) The multi-layer sandwich structure. (b) The upward and downward gradient distribution structures. The white balls in both (a,b) present particles.

The gradient distribution structures have been enhanced to optimize the balance between RC performance and durability. These structures can be categorized into two main types: the upward gradient distribution, featuring a top-to-bottom decrease in pigment packing density, and the downward gradient distribution, both of which demonstrate structural advantages (Figure 2b). The upward structure scatters sunlight via concentrated particles in the upper layer while ensuring strong adhesion through abundant polymer resins at the bottom [105]. The downward gradient distribution exhibits higher Rsolar and Pnet values compared with uniform particle systems [106]. Here, a self-stratification strategy refers to a one-step coating process in which differences in surface energy, density, and solubility parameters between components, together with the preferential migration of polar particles toward the substrate, drive their spontaneous vertical segregation during drying. This mechanism enables the in-situ formation of a gradient structure within a single coating step, thereby simplifying the overall fabrication process [107,108]. The spontaneously layered coatings reduce interfacial adhesion failures and maintain integrated functionality, resembling a sandwich structure [109].

In conclusion, the structural optimization serves as a highly effective strategy to overcome the challenges posed by blocking RC paints in real-world applications. Researchers and commercial paint manufacturers have collaboratively devised diverse structural designs tailored for large-scale deployment. It is anticipated that more advanced RC paints will be widely adopted in buildings, vehicles, and equipment to effectively address high-temperature-related concerns.

6. Conclusions and Outlook for the Next Generation of RC Paints

RC paints have emerged as a highly promising passive cooling technology that significantly reduces building cooling energy demands while effectively alleviating urban heat island effects when implemented widely, thereby fostering more sustainable and thermally pleasant urban environments. In recent years, research priorities have progressively shifted from merely pursuing optimal optical properties to developing comprehensive solutions that concurrently enhance cooling efficiency, production feasibility, long-term durability, and architectural adaptability. In summary, this review systematically examines cutting-edge innovations in RC paint formulation strategies, emphasizing sophisticated material configurations, precision spectral modulation across multiple wavelength bands, synergistic integration with complementary technologies, and durable structural designs for practical implementation. Building on these advances, we further identify several critical research frontiers that merit focused exploration in future studies.

- (I)

- Standardized durability evaluation across realistic environments. While the durability of paints has been extensively studied, the long-term reliability of reinforced composite RC paints under varied service conditions remains insufficiently characterized. Environmental stressors, including UV radiation, acid rain, airborne contaminants, salt spray, and mechanical abrasion, can progressively deteriorate both the optical and mechanical performance of RC paints. Existing durability assessments are often fragmented and lack consistency, frequently falling short of replicating real-world operational environments [20,104]. Consequently, developing unified, scenario-specific evaluation frameworks is critical. Researchers are supposed to assess RC paints through more rigorous and standardized testing methodologies aligned with American Society of Testing Materials (ASTM) or International Organization for Standardization (ISO) guidelines to accurately predict service life. Beyond fundamental durability, targeted performance metrics should undergo stringent evaluation tailored to specific applications, such as building facades, marine vessels, and automotive surfaces [104].

- (II)

- Economic feasibility and scalability in manufacturing. While RC paints inherently provide a low-energy cooling solution, their practical implementation hinges on optimizing the trade-offs among material costs, production complexity, and long-term financial viability. A comprehensive assessment of lifecycle costs and projected payback periods should be integrated into formulation development to quantify economic impact. Simplified production processes, user-friendly application methods, and minimal maintenance demand further amplify the cost-effectiveness of RC paints.

- (III)

- Pioneering multifunctional and intelligent integration: The next-generation RC paints will evolve beyond single-function cooling by integrating advanced capabilities designed for complex environments and cutting-edge technologies. Emerging applications in defense (e.g., infrared camouflage, radar stealth) and smart buildings (e.g., anti-fogging, privacy glazing) necessitate synchronized control of both solar and MIR spectra [110,111]. Realizing such multifunctionality demands interdisciplinary collaboration to balance optical selectivity with mechanical durability and environmental resilience, combining expertise in nanophotonics, metamaterial engineering, polymer chemistry, and system-level design.

To effectively tackle these challenges, synergistic breakthroughs in material innovation, scalable manufacturing processes, and system-level optimization will be essential. Achieving the seamless integration of outstanding durability, precise spectral management, and economic viability will prove critical for transitioning radiative cooling paints from experimental prototypes to large-scale commercialization. Future research efforts are expected to concentrate on harmonizing superior durability, accurate spectral regulation, cost efficiency, and high Pnet, positioning this field as an exceptionally promising scientific frontier.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and methodology, Z.Z., Z.G. and R.Z.; validation, Y.H., F.L., R.L. and Y.Z.; investigation and resources, S.Z., L.F., S.T., Q.C. and M.L.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.Z.; writing—review and editing, R.Z., Y.H. and F.L.; supervision, R.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2020YFA0210702, 2020YFC2201103), the Red Avenue Innovation R&D Foundation, the CNPC Innovation Fund (2024DQ02-0409), and Ordos Laboratory (20232000757).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Tian, H.; Lu, C.; Ciais, P.; Michalak, A.M.; Canadell, J.G.; Saikawa, E.; Huntzinger, D.N.; Gurney, K.R.; Sitch, S.; Zhang, B.; et al. The terrestrial biosphere as a net source of greenhouse gases to the atmosphere. Nature 2016, 531, 225–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Global Warming of 1.5 °C: IPCC Special Report on Impacts of Global Warming of 1.5 °C Above Pre-Industrial Levels in Context of Strengthening Response to Climate Change, Sustainable Development, and Efforts to Eradicate Poverty, 1st ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, Y.; Lai, J.-C.; Xiao, X.; Jin, W.; Zhou, J.; Yang, Y.; Gao, X.; Tang, J.; Fan, L.; Fan, S.; et al. Colorful low-emissivity paints for space heating and cooling energy savings. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2300856120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, B.; Zhang, R.; Luo, Y.; Zhang, S.; Xu, L.; Min, H.; Tang, S.; Meng, X. 3D porous polymer film with designed pore architecture and auto-deposited SiO2 for highly efficient passive radiative cooling. Nano Energy 2021, 81, 105600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercier, S.; Villeneuve, S.; Mondor, M.; Uysal, I. Time–Temperature Management Along the Food Cold Chain: A Review of Recent Developments. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2017, 16, 647–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, P.-C.; Liu, C.; Song, A.Y.; Zhang, Z.; Peng, Y.; Xie, J.; Liu, K.; Wu, C.-L.; Catrysse, P.B.; Cai, L.; et al. A dual-mode textile for human body radiative heating and cooling. Sci. Adv. 2017, 3, e1700895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, C.; Lu, J.; Zhang, S.; Su, J.; Han, J. Hierarchical-porous coating coupled with textile for passive daytime radiative cooling and self-cleaning. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2022, 247, 111954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Shi, S.; Xu, H.; Li, C.; Yang, R.; Luo, Z.; Chen, W.; Chen, Y. Preparation and Properties of High-temperature Resistant Infrared Radiant Coating with High Emissivity for Spacecraft. Paint Coat. Ind. 2023, 53, 8–13+19. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, H.; Guo, C.; Fan, F.; Pan, H.; Xu, Q.; Zhao, D. Both sub-ambient and above-ambient conditions: A comprehensive approach for the efficient use of radiative cooling. Energy Environ. Sci. 2024, 17, 4498–4507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Liu, X.; Wang, Z.; Li, J.; Mu, Y.; Zhou, S.; Chen, F.; Minus, M.L.; Xiao, G.; Zheng, Y. Subambient daytime cooling enabled by hierarchically architected all-inorganic metapaper with enhanced thermal dissipation. Nano Energy 2022, 96, 107085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, E.A.; Raman, A.P.; Fan, S. Sub-ambient non-evaporative fluid cooling with the sky. Nat. Energy 2017, 2, 17143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Sun, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Alam, M.A.; Bermel, P. Radiative sky cooling: Fundamental physics, materials, structures, and applications. Nanophotonics 2017, 6, 997–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, S.; Li, W. Photonics and thermodynamics concepts in radiative cooling. Nat. Photonics 2022, 16, 182–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.; Park, C.; Park, S.; Lee, J.; Choi, J.-H.; Kim, Y.S.; Yoo, Y. Passive Daytime Radiative Cooling by Thermoplastic Polyurethane Wrapping Films with Controlled Hierarchical Porous Structures. ChemSusChem 2022, 15, e202201842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Tan, Z. Research on the Principles and Applications of Radiative Cooling Materials. Paint Coat. Ind. 2025, 55, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, A.W.; Walton, M.R. Radiative cooling of TiO2 white paint. Sol. Energy 1978, 20, 185–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Zhang, W.; Sun, Z.; Pan, M.; Tian, F.; Li, X.; Ye, M.; Deng, X. Durable radiative cooling against environmental aging. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 4805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, J.; Yang, Y.; Yu, N.; Raman, A.P. Paints as a Scalable and Effective Radiative Cooling Technology for Buildings. Joule 2020, 4, 1350–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raman, A.P.; Anoma, M.A.; Zhu, L.; Rephaeli, E.; Fan, S. Passive radiative cooling below ambient air temperature under direct sunlight. Nature 2014, 515, 540–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Zhao, S.; Xu, J.; Wu, X.; Guo, Z.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, R. Progress in passive daytime radiative cooling from spectral design to real application. Carbon Future 2025, 2, 9200033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Lin, T.; Cheng, J.; Lin, B. Research Progress of Radiative Cooling Coatings. Paint Coat. Ind. 2025, 55, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Li, C.; Qiao, Z.; Lei, C.; Ju, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Fu, Q.; Wu, K. Crack-Resistant and Self-Healable Passive Radiative Cooling Silicone Compounds. Adv. Mater. 2025, 37, 2500738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Yang, R.; Tan, G.; Fan, S. Terrestrial radiative cooling: Using the cold universe as a renewable and sustainable energy source. Science 2020, 370, 786–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, J.; Fu, Y.; Overvig, A.C.; Jia, M.; Sun, K.; Shi, N.N.; Zhou, H.; Xiao, X.; Yu, N.; Yang, Y. Hierarchically porous polymer coatings for highly efficient passive daytime radiative cooling. Science 2018, 362, 315–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, C.; Zhang, W.; Ni, J.; Li, L.; Hao, Y.; Pei, G.; Zhao, B. Multi-interface porous coating for efficient sub-ambient daytime radiative cooling. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2025, 286, 113577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.-H.; Pu, Q.-R.; Hu, W.-J.; Liu, Q.-Q.; Li, X.; Huang, W.-H.; Zhang, N.; Wang, Y. “Pore in Pore” Engineering in Poly(dimethylsiloxane)/Silicon Oxide Foams for Passive Daytime Radiative Cooling. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2025, 7, 6887–6897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Z.-C.; Zeng, F.-R.; Zeng, Z.-W.; Su, P.-G.; Tang, P.-J.; Liu, B.-W.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.-Z.; Zhao, H.-B. Scalable Low-Carbon Ambient-Dried Foam-Like Aerogels for Radiative Cooling with Extreme Environmental Resistance. Adv. Mater. 2025, 37, 2505224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Caratenuto, A.; Chen, F.; Zheng, Y. Controllable-gradient-porous cooling materials driven by multistage solvent displacement method. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 488, 150657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Zheng, W.; Singh, D.J. Light scattering and surface plasmons on small spherical particles. Light Sci. Appl. 2014, 3, e179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Peoples, J.; Huang, Z.; Zhao, Z.; Qiu, J.; Ruan, X. Full Daytime Sub-ambient Radiative Cooling in Commercial-like Paints with High Figure of Merit. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 2020, 1, 100221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felicelli, A.; Katsamba, I.; Barrios, F.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, Z.; Peoples, J.; Chiu, G.; Ruan, X. Thin layer lightweight and ultrawhite hexagonal boron nitride nanoporous paints for daytime radiative cooling. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 2022, 3, 101058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Im, D.; Sung, S.; Yu, J.; Kim, H.; Lee, J.; Yoo, Y. Scalable and efficient radiative cooling coatings using uniform-hollow silica spheres. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2024, 254, 123810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Peoples, J.; Yao, P.; Ruan, X. Ultrawhite BaSO4 Paints and Films for Remarkable Daytime Subambient Radiative Cooling. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 21733–21739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Li, S.; Zhang, Y.; Na, Y.; Sun, C.; Zhao, D.; Liu, J.; Zhou, Z. Radiative cooling performance and life-cycle assessment of a scalable MgO paint for building applications. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 380, 135035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Z.; Peoples, J.; Li, X.; Yang, X.; Bao, H.; Ruan, X. Electronic and phononic origins of BaSO4 as an ultra-efficient radiative cooling paint pigment. Mater. Today Phys. 2022, 24, 100658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Lin, C.; Li, K.; Ma, W.; Dopphoopha, B.; Li, Y.; Huang, B. A UV-Reflective Organic–Inorganic Tandem Structure for Efficient and Durable Daytime Radiative Cooling in Harsh Climates. Small 2023, 19, 2301159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.; Park, C.; Nie, X.; Lee, J.; Kim, Y.S.; Yoo, Y. Fully Organic and Flexible Biodegradable Emitter for Global Energy-Free Cooling Applications. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 7091–7099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, D.; Sun, S.; Du, P.; Lu, X.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Z. Hollow Core-Shell Particle-Containing Coating for Passive Daytime Radiative Cooling. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2022, 158, 106949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Bu, X.; Yu, T.; Wang, X.; He, M.; Zhang, Z.; Feng, M.; Zhou, Y. Design and scalable fabrication of core-shell nanospheres embedded spectrally selective single-layer coatings for durable daytime radiative cooling. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2023, 260, 112493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, E.; Feng, D.; Fang, Z.; Carne, D.; Gonzalez, O.R.; Lee, W.-J.; Vansal, N.; Raykova, K.; Ruan, X. Efficient, Hydrophobic, and Weather-Resistant Radiative Cooling Paints with Silicone-Based Binders. ACS Appl. Opt. Mater. 2025, 3, 1137–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljwirah, A.K.; Liu, X.; Rivera Gonzalez, O.; Alhammadi, K.; Lee, W.-J.; Katsamba, I.; Ruan, X. Water-Based Hydrophobic Paints for Daytime Radiative Cooling. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2025, 17, 32914–32927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, B.R.; Sundaram, S.; Sasihithlu, K. Cooling Performance of TiO2-Based Radiative Cooling Coating in Tropical Conditions. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 49494–49502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mei, X.; Wang, T.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, T.; Chen, M.; Wu, L. Scalable bilayer thin coatings with enhanced thermal dissipation for passive daytime radiative cooling. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 495, 153182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Zulfiqar, U.; Ramirez-Cuevas, F.V.; Parvate, S.; Yu, Y.; Alduweesh, A.; Parkin, I.P.; Zghaib, P.; Mead, S.; Khan, H.S.; et al. All-day radiative cooling with superhydrophobic, fluorine-free polydimethylsiloxane-embedded porous polyethylene coating. Mater. Today Sustain. 2025, 31, 101168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Li, J.; Jiang, Q.; Zhang, W.; Wang, B.; Li, R.; Zhao, S.; Wang, F.; Huang, Y.; Lyu, P.; et al. An all-weather radiative human body cooling textile. Nat. Sustain. 2023, 6, 1446–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentley, J. 2—Organic film formers. In Paint and Surface Coatings, 2nd ed.; Lambourne, R., Strivens, T.A., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 1999; pp. 19–90. [Google Scholar]

- Marrion, A.R. (Ed.) The Chemistry and Physics of Coatings; The Royal Society of Chemistry: Cambridge, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Javadi, A.; Cobaj, A.; Soucek, M.D. Chapter 12—Commercial waterborne coatings. In Handbook of Waterborne Coatings; Zarras, P., Soucek, M.D., Tiwari, A., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 303–344. [Google Scholar]

- Mohanty, D.S.M.; Kanny, K. Chapter 3—Role of Additives in Waterborne Epoxy Coatings. In Recent Advances on Waterborne Epoxy Coatings; Pradhan, S.S.M., Mohanty, S., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2025; pp. 37–62. [Google Scholar]

- Dopphoopha, B.; Li, K.; Lin, C.; Huang, B. Aqueous double-layer paint of low thickness for sub-ambient radiative cooling. Nanophotonics 2024, 13, 659–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, S.; Wang, F.; Yang, S.; Long, H.; Ju, H.; Ou, J. Water-based kaolin/polyacrylate cooling paint for exterior walls. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2023, 677, 132401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Tang, Y. Progress and Development Trend of Standardization of Coatings and Pigments. Paint Coat. Ind. 2024, 54, 81–88. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, M. Research on the Application of Substrate Wetting Agent in Water-borne Coatings. Paint Coat. Ind. 2023, 53, 76–81. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Wen, S.; Wang, J.; Wang, C.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, J.; Li, S. Water Evaporation of Waterborne Polyacrylate Coatings During the Film Formation Process. Paint Coat. Ind. 2022, 52, 15–20. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, H.; Wang, R.; Liang, F.; Xie, W.; Xu, Y.; Xu, Z.; Li, G.; Ouyang, S. Influence of Formulation Design of Waterborne Paint System on the Compatibility of “Wet-on-wet” Coating. Paint Coat. Ind. 2022, 52, 78–82. [Google Scholar]

- Li, P.; Liu, Y.; Liu, X.; Wang, A.; Liu, W.; Yi, N.; Kang, Q.; He, M.; Pei, Z.; Chen, J.; et al. Reversed Yolk–Shell Dielectric Scatterers for Advanced Radiative Cooling. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2315658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Cui, P.; Xu, M.; Ding, Z.; Zhuang, Z. Study on Thermal Properties of Inorganic Reflective Thermal Insulation Coatings. Paint Coat. Ind. 2020, 50, 30–35. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, L.; Cai, W.; Cui, T.; Li, J.; Song, L.; Gui, Z.; Fei, B.; Zhu, J.; Hu, Y.; Xing, W. Anisotropic Radiative Cooling Dynamics Enabling Efficient Thermal Hazard Mitigation via Hierarchically Engineered Thermal Diodes. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, e08101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, D.; Wang, C.; Han, C.B.; Cui, Y.; Ren, W.R.; Zhao, W.K.; Jiang, Q.; Yan, H. Highly Optically Selective and Thermally Insulating Porous Calcium Silicate Composite SiO2 Aerogel Coating for Daytime Radiative Cooling. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 9303–9312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, X.; Han, H.; Kondo, H.; Zhou, H. Flexible highly thermal conductive hybrid film for efficient radiative cooling. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2024, 266, 112660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, X.; Zhang, K.; Lai, X.; Hu, L.; Vogelbacher, F.; Song, Y.; Jiang, L.; Li, M. Brilliant colorful daytime radiative cooling coating mimicking scarab beetle. Matter 2025, 8, 101898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, D.; Witty, A.S.; Birnbaum, F.I.; Gonzalez, O.G.R.; Felicelli, A.; Lee, W.-J.; Barber, E.C.; Ruan, X. Self-Stratifying Colored Radiative Cooling Paints Through Narrow-Band Color Preservation Scheme. Adv. Mater. 2025, 37, e04382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Mandal, J.; Li, W.; Smith-Washington, A.; Tsai, C.-C.; Huang, W.; Shrestha, S.; Yu, N.; Han, R.P.S.; Cao, A.; et al. Colored and paintable bilayer coatings with high solar-infrared reflectance for efficient cooling. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eaaz5413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Liu, Y.; Dong, Y.; Yin, X.; Lei, D.; Dai, J.-G. Colored Radiative Cooling: From Photonic Approaches to Fluorescent Colors and Beyond. Adv. Mater. 2025, 37, 2414300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.W.; Yi, J.; Kim, M.K.; Kim, D.R. Transparent radiative cooling cover window for flexible and foldable electronic displays. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 4443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, H.; Wang, C.; Yu, J.; Huang, D.; Yang, R.; Wang, R. Eliminating greenhouse heat stress with transparent radiative cooling film. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 2023, 4, 101539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Geng, M.; Dong, B.; Zhao, L.; Wang, S. Transparent and robust SiO2/PDMS composite coatings with self-cleaning. Surf. Eng. 2020, 36, 643–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Liu, X.; Li, W.; Lin, Z.; Zhu, B.; Li, Z.; Li, J.; Li, B.; Fan, S.; Xie, J.; et al. Scalable and hierarchically designed polymer film as a selective thermal emitter for high-performance all-day radiative cooling. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2021, 16, 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Z.; Wang, X.; Ma, Y.; Hu, B.; Zhou, J. Transparent Polymer Coatings for Energy-Efficient Daytime Window Cooling. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 2020, 1, 100231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T.; Liu, R.; Wang, X.; Yang, Z.; Gu, X.; Yang, S.; Ye, Z.; Wen, Z.; Lu, J. Transparent Radiative Cooling Films Based on Dendritic Silica for Room Thermal Management. Carbon Neutral 2025, 4, e70020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Lee, D.; Son, S.; Yang, Y.; Lee, H.; Rho, J. Visibly Transparent Radiative Cooler under Direct Sunlight. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2021, 9, 2002226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Wang, C.; Zhu, H.; Zhou, Y.; Li, H.; Liu, L.; Ma, L. Adaptive Thermal Management Radiative Cooling Smart Window with Perfect Near-Infrared Shielding. Small 2024, 20, 2306823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, C.; Liu, M.; Yao, K.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Yan, M.; Sun, Y.; Liu, X.; Cui, X.; Fan, T.; et al. Ultrabroadband and band-selective thermal meta-emitters by machine learning. Nature 2025, 643, 80–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Tang, G.; Xiang, X.; Qin, M.; Qiu, Y.; Lai, J.-C.; Peng, Y. Self-Stratifying Colorful Low-Emissivity Paint for Thermal Regulation and Energy Saving. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 35, 2507409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Lee, W.-J.; Carne, D.W.; Tian, Y.; Felicelli, A.; Lei, Y.; Romo, J.A.; You, L.; Xiong, Z.; Gonzalez, O.G.R.; et al. High-Performance Low-Emissivity Paints Enabled by N-Doped Poly(benzodifurandione) (n-PBDF) for Energy-Efficient Buildings. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 2419685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, F.; Jin, W.; Nolen, J.R.; Pan, H.; Yi, N.; An, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Kong, X.; Zhu, F.; Jiang, K.; et al. Subambient daytime radiative cooling of vertical surfaces. Science 2024, 386, 788–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.; Sui, C.; Chen, T.-H.; Zhou, Z.; Li, Q.; Yan, G.; Han, Y.; Liang, J.; Hung, P.-J.; Luo, E.; et al. Spectrally engineered textile for radiative cooling against urban heat islands. Science 2024, 384, 1203–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, M.; Song, Z.; Ni, J.; Du, X.; Cao, Y.; Yang, Y.; Wang, W.; Wang, J. Dual-Mode Porous Polymeric Films with Coral-like Hierarchical Structure for All-Day Radiative Cooling and Heating. ACS Nano 2023, 17, 2029–2038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, W.; Qi, L.; Cui, T.; Lin, B.; Rahman, M.Z.; Hu, X.; Ming, Y.; Chan, A.P.; Xing, W.; Wang, D.-Y.; et al. Chameleon-Inspired, Dipole Moment-Increasing, Fire-Retardant Strategies Toward Promoting the Practical Application of Radiative Cooling Materials. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 35, 2412902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, D.; Ng, B.F.; Wan, M.P. Preliminary study of passive radiative cooling under Singapore’s tropical climate. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2020, 206, 110270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Li, P.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, C.; He, M.; Pei, Z.; Chen, J.; Shi, K.; Liu, F.; Wang, W.; et al. Hybrid Passive Cooling for Power Equipment Enabled by Metal-Organic Framework. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, 2409473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Huang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Rao, Z.; Li, W.; Chen, Z.; Chen, M. Self-sustained and Insulated Radiative/Evaporative Cooler for Daytime Subambient Passive Cooling. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 6513–6522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Sun, D.-W.; Tian, Y.; Sun, L.; Zhu, Z. Self-rehydrating and highly entangled hydrogel for sustainable daytime passive cooling. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 479, 147795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Q.; Chen, D.; Zhao, Z.; Yan, H.; Chen, M. Adhesive Hydrogel Paint for Passive Heat Dissipation via Radiative Coupled Evaporation Cooling. Small 2025, 21, 2412221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, J.; Zhang, X.; Han, D.; Lei, Y.; Xie, F.; Zhou, K.; Koh, S.-W.; Ge, J.; Zhou, H.; Wang, X.; et al. Passive cooling paint enabled by rational design of thermal-optical and mass transfer properties. Science 2025, 388, 1044–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.-W.; Zeng, F.-R.; Lin, X.-C.; Wang, Y.-Q.; Ma, Y.-H.; Jia, X.-X.; Zhang, J.-C.; Liu, B.-W.; Wang, Y.-Z.; Zhao, H.-B. A photoluminescent hydrogen-bonded biomass aerogel for sustainable radiative cooling. Science 2024, 385, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, X.; Fu, Y.; Liu, D.; Yang, N.; Dai, J.-G.; Lei, D. Fluorescence-Enabled Colored Bilayer Subambient Radiative Cooling Coatings. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2024, 12, 2303296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, S.; Jin, C.; Zhu, B.; Su, Y.; Dong, X.; Liang, J.; Lu, Z.; Zhou, L.; et al. Sub-ambient full-color passive radiative cooling under sunlight based on efficient quantum-dot photoluminescence. Sci. Bull. 2022, 67, 1874–1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, Q.; Chen, J.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, L. Spectrally Engineered Coatings for Steering the Solar Photons. Adv. Mater. 2025, 37, 2502542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Ma, X.; Zhang, X.-W.; Li, Z.; Wang, C.; Lin, K.; Zhou, Y.; Pan, A.; Chen, X.; Li, X.; et al. Photoluminescent radiative cooling for aesthetic and urban comfort. Nat. Sustain. 2025, 8, 1328–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ładosz, Ł.; Sudoł, E.; Kozikowska, E.; Choińska, E. Artificial Weathering Test Methods of Waterborne Acrylic Coatings for Steel Structure Corrosion Protection. Materials 2024, 17, 1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elert, K.; Cardell, C. Weathering behavior of cinnabar-based tempera paints upon natural and accelerated aging. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2019, 216, 236–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.; Martin, J.; Byrd, E. Relating laboratory and outdoor exposure of coatings: IV. Mode and mechanism for hydrolytic degradation of acrylic-melamine coatings exposed to water vapor in the absence of UV light. J. Coat. Technol. 2003, 75, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hook, J.W.; Jacox, P.J.; Spence, J.W. Acid rain effects on the exterior durability of architectural coatings on wood. Prog. Org. Coat. 1994, 24, 175–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, K. The internal stress of coating films. Prog. Org. Coat. 1980, 8, 143–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrıguez, M.T.; Gracenea, J.J.; Kudama, A.H.; Suay, J.J. The influence of pigment volume concentration (PVC) on the properties of an epoxy coating: Part I. Thermal and mechanical properties. Prog. Org. Coat. 2004, 50, 62–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaugendre, A.; Degoutin, S.; Bellayer, S.; Pierlot, C.; Duquesne, S.; Casetta, M.; Jimenez, M. Self-stratifying coatings: A review. Prog. Org. Coat. 2017, 110, 210–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bijarniya, J.P.; Sarkar, J.; Tiwari, S.; Maiti, P. Development and degradation analysis of novel three-layered sustainable composite coating for daytime radiative cooling. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2023, 257, 112386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Jiang, X.; Cheng, Z.; Hu, W.; Long, E. A sandwich-structured material with wavelength conversion functionality for all-day radiative cooling. Renew. Energy 2025, 255, 123839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Li, B.; Zheng, X.; Zhu, J.; Pi, L. Mechanism Analysis and Solution of Loss of Light on Two component Varnish under External Mixed Spraying Mode. Paint Coat. Ind. 2024, 54, 74–76. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X.; Li, T.; Xie, H.; Liu, H.; Wang, L.; Qu, Y.; Li, S.C.; Liu, S.; Brozena, A.H.; Yu, Z.; et al. A solution-processed radiative cooling glass. Science 2023, 382, 684–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallerup, R.; Foged, C. Advances in Delivery Science and Technology; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 15–29. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Z.; Ouyang, G.; Shi, X.; Ma, Q.; Wan, G.; Qiao, Y. Absorption and quantitative characteristics of C-H bond and O-H bond of NIR. Opt. Spectrosc. 2014, 117, 703–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Shen, Q.; Shao, H.; Deng, X. Anti-Environmental Aging Passive Daytime Radiative Cooling. Adv. Sci. 2023, 11, e230566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, X.; Wang, H.; Lu, Y.; Wang, M.; Wang, J.; Liu, H.; Zhou, W.; Zhao, G.; Gao, J.; Sun, F.; et al. Auto-Deposited Microparticle Composite Coating for Low-Cost and Efficient Daytime Radiative Cooling. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2025, 17, 8274–8284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; An, Y.; Xu, Y.; Dai, J.-G.; Lei, D. Polymer coating with gradient-dispersed dielectric nanoparticles for enhanced daytime radiative cooling. EcoMat 2022, 4, e12169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, S.; Wu, Q.; Zhang, W.; Xia, G.; Yang, L.; Cui, J. Slippery Passive Radiative Cooling Supramolecular Siloxane Coatings. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 4571–4578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Wei, H.; Niu, T.; Chen, P. Phase Separation Theory and Design Strategy of Gradient Self-stratifying Coating System. Paint Coat. Ind. 2025, 55, 76–82. [Google Scholar]

- Zahedi, S.; Zaarei, D.; Ghaffarian, S.R. Self-stratifying coatings: A review. J. Coat. Technol. Res. 2018, 15, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.-X.; Luo, Z.; Sun, H.; Quan, Q.; Zhou, S.; Yang, W.-G.; Yu, Z.-Z.; Yang, D. Spectral-Selective and Adjustable Patterned Polydimethylsiloxane/MXene/Nanoporous Polytetrafluoroethylene Metafabric for Dynamic Infrared Camouflage and Thermal Regulation. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2407644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, C.; Pu, J.; Chen, T.-H.; Liang, J.; Lai, Y.-T.; Rao, Y.; Wu, R.; Han, Y.; Wang, K.; Li, X.; et al. Dynamic electrochromism for all-season radiative thermoregulation. Nat. Sustain. 2023, 6, 428–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.