Abstract

Niobium nitride (δ-NbN) coatings were deposited on AISI 316L austenitic steel using reactive DC magnetron sputtering. This study investigates the effects of air oxidation on the surface morphology, topography, roughness, nanohardness, adhesion, and wear resistance of NbN coatings. Their microstructure and thickness were analyzed by scanning electron microscopy (SEM), while surface morphology and roughness were assessed using atomic force microscopy (AFM), and surface topography was assessed by an optical profilometer. Nanohardness was measured using a Berkovich indenter. Adhesion was evaluated via progressive-load scratch testing and Rockwell indentation (VDI 3198 standard). Wear resistance was assessed using the “ball-on-disk” method. Both as-deposited and oxidized NbN coatings improved the mechanical performance of the substrate surface. Air oxidation led to the formation of an orthorhombic Nb2O5 surface layer, which increased surface roughness and reduced hardness. However, the brittle oxide also contributed to a lower coefficient of friction. Despite reduced adhesion and increased surface development, the oxidized coating exhibited a significantly lower wear rate than the uncoated steel, though several times higher than that of the non-oxidized NbN. Considering its good wear and corrosion performance, along with the bioactivity confirmed in earlier research, the oxidized NbN coating can be considered a promising candidate for biomedical applications.

1. Introduction

In recent years, the demand for advanced materials in various industrial applications has led to significant interest in the development of protective coatings. Among these, niobium nitride (NbN) coatings have gained attention due to their exceptional mechanical properties, including high hardness, wear resistance, thermal stability [1,2,3] and high-temperature superconductivity properties [4,5]. These characteristics make NbN coatings particularly suitable for enhancing the performance and longevity of austenitic stainless steels, such as AISI 316L, which in their uncoated form exhibit low hardness, limited resistance to frictional wear, and reduced corrosion resistance in chloride-containing environments [6]. They are still widely used in medical implants and devices [7,8,9], as well as in many other industries [10,11]. The deposition of NbN coatings can be achieved through various techniques, mainly using physical vapor deposition (PVD) methods such as high power impulse magnetron sputtering (HPIMS) [12,13], unbalanced magnetron sputtering [14,15,16], reactive pulsed laser deposition [1] and multi-arc ion plating [17]. These methods allow for precise control over the coating thickness, morphology, and stoichiometry, leading to tailored properties that meet specific application requirements. Notably, magnetron sputtering has emerged as a preferred technique due to its ability to produce dense and uniform films with excellent adhesion to substrates [18,19]. The application of a hard, ceramic NbN coating on commonly used AISI 316L steel can provide improved wear and corrosion resistance. There are relatively few reports on the coating of austenitic steels with niobium nitride that focus on both corrosion and wear resistance analysis [17,20,21,22,23,24]. The performance of NbN coatings can be further influenced by their oxidation behavior. The thermal oxidation of NbN can lead to the formation of a stable oxide layer, which may enhance its corrosion resistance while maintaining its wear-resistant capabilities. Niobium pentoxide (Nb2O5) is a desirable coating material due to its very good corrosive but also biological properties [25,26,27,28,29]. There is limited data on the production of niobium oxide coatings on austenitic steels [28,29,30,31,32], and almost no reports on niobium oxide layers produced on niobium nitride coatings [23,33]. The combination of the NbN coating production process with subsequent surface oxidation has been shown to improve the corrosion resistance of AISI 316L steel in Ringer’s solution at 37 °C and bioactivity [23]; however, the effect of oxidation on adhesion and resistance to frictional wear has not yet been investigated.

The aim of this study was to analyze the surface topography, morphology, roughness, nanohardness, adhesion, and wear resistance of the NbN coating and oxidized NbN coating with a Nb2O5 top layer produced on AISI 316L steel and to compare the properties of the produced coating and layer with the steel in its initial state.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Specimen Preparation

Ten disk-shaped samples with dimensions of Ø25 × 6 mm were cut from an AISI 316L steel bar. One of the flat surfaces was wet-ground using 240- to 1200-grit sandpaper and then degreased in an ultrasonic washer using acetone (Chempur, Piekary Śląskie, Poland). All prepared samples were coated with a NbN coating in the magnetron sputtering process, and then half of them were oxidized in a furnace in an air atmosphere. The coatings were produced using the magnetron sputtering method on the WU-1B vacuum station (National Academy of Sciences of Belarus, Minsk, Belarus) equipped with a 3″ diameter Nb 99.95% cathode (Kurt J. Lesker, Jefferson Hills, PA, USA) and a Dora’s MSS-10 power supply (Wilczyce, Poland), as previously described [23]. The initial ion etching of the niobium target lasted 3 min and was carried out in an Ar atmosphere at a voltage of 1000 V, a current of 3.22 A, a power of 1.2 kW, a pressure of 10 Pa and a substrate temperature of 360 °C. The distance between the target and the samples was 70 mm. The next step was to produce NbN coatings, which were formed in an Ar and N2 atmosphere in a ratio of 5:1 (20% N2), in 30 min, at a pressure of 0.8 Pa, a current of 4.9 A, a power of 2 kW, a substrate bias of −80 V and a deposition temperature of 438 °C. The nitrogen ratio was selected to obtain cubic δ-NbN [34], which is characterized by higher oxidation kinetics than hexagonal β-Nb2N [33]. Five samples with produced NbN coatings were oxidized in an ambient air atmosphere under atmospheric pressure for 4 h at a temperature of 480 °C using a Nabertherm RS 80/300/13 furnace (Nabertherm, Lilienthal, Germany). The oxidation temperature was selected on the basis of preliminary studies and was set at a level of 480 °C to maximize oxidation kinetics while preventing the precipitation of chromium carbides, Cr23C6, in the austenitic steel, which occurs predominantly at temperatures above approximately 500 °C [35] and causes its sensitization to intergranular corrosion [36].

2.2. Cross-Section Microstructural Analysis

The samples with the NbN coating and oxidized layer were cut in their cross-sections using a precision saw, then hot mounted using an automatic press in a conductive resin with the addition of graphite. Their surfaces in the cross-sections were ground similarly to the preparation of the sample surfaces for the processes, then polished using a diamond suspension and etched using a reagent consisting of 50% HCl + 25% HNO3 + 25% H2O (HCl and HNO3 produced by Chempur, Piekary Śląskie, Poland). The microstructures were observed using a Hitachi S-3500N scanning electron microscope (Tokyo, Japan) with a secondary electron (SE) detector at an accelerating voltage of 15 kV.

2.3. Surface Topography and Roughness Tests

The surface topography of the prepared samples was studied using a Veeco’s Wyko NT9300 optical profilometer (Veeco, Plainview, NY, USA) at 10× magnification utilizing Vision software, version 4.10, and selected 3D images of the sample surfaces were presented. The topography on a micro scale was studied using a FlexAFM atomic force microscope (AFM) (Nanosurf AG, Liestal, Switzerland) equipped with an HQ:CSC17/Al BS probe working in contact mode. The normal load was maintained at 13 nN, and the scanning speed was set to 5 µm/s. The obtained data were analyzed using the Gwyddion open-source software, version 2.68 [37]. Raw images (5 × 5 µm) were leveled by subtracting the mean plane and removing a polynomial background. Subsequently, Ra (arithmetic mean deviation of the profile from the mean line) and Rt (total height of profile, i.e., the vertical distance between the maximum profile peak height and the maximum profile valley depth) roughness parameters were determined from 5 × 5 µm areas, with at least six measurements per sample.

2.4. Nanohardness Measurements

Nanohardness measurements were performed on a Hysitron Ti-900 device (Hysitron, Minneapolis, MN, USA). The maximum loading force was 10 mN. The loading and unloading speed was 1 mN/s and the holding time was 2 s. A Berkovich-type indenter was used for the test. At least 40 indentations were made for each variant. Based on the measured hardness H and the reduced Young’s modulus Er, the resistance to plastic deformation H3/E2 was also calculated.

2.5. Adhesion Tests

Adhesion tests of the coatings were carried out on a CSM Revetest scratch-test device (CSM Instruments, Needham, MA, USA) using a Rockwell diamond indenter with a tip radius of 0.2 mm. The test sample was moved at a constant speed of 1.5 mm/min perpendicular to the tip. The scratch lengths were 8 mm, and the contact force varied linearly from 1 to 50 N. Analysis of the coatings’ adhesion was based on scratch observations using a Nikon LV 150N Eclipse optical microscope (Nikon Instruments Inc., Melville, NY, USA). Based on the conducted tests, the following parameters were determined: Lc1 (critical load attributed to cohesive failure of the coating), Lc2 (load at which adhesive damage of the coating starts), and Lc3 (critical load at which breakthrough of the coating is experienced). The adhesion of the coatings was also determined according to the Verein Deutscher Ingenieure (VDI) 3198 norm [38,39]. For each sample, three indentations were made, spaced at least 5 mm apart, using a Rockwell diamond conical indenter on a Zwick/Roell ZHR 4150LK hardness tester (ZwickRoell, Ulm, Germany), applying a main load of 1500 N for approximately 10 s. Images of the indentations were then visualized and recorded using the same microscope as used for the scratch tests. Representative indentations for the NbN coating and the oxidized coating are shown. Cracks near the indentations were additionally analyzed by energy-dispersive X-ray spectrometry (EDS), which provided elemental distribution maps of Nb, Fe and O. The analysis was conducted at an accelerating voltage of 15 kV using an Axia ChemiSEM HiVac 1247445 scanning electron microscope equipped with an EDS spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

2.6. Fiction Wear Tests

Dry “Ball-on-disk” friction wear tests were performed on a T-21 tribotester (ITEE, Radom, Poland) according to the requirements defined in standards ASTM G 99-05 and ISO 20808:2004 at an ambient temperature of ca. 22 ± 2 °C and a relative humidity of 45%. 6.35 mm diameter Al2O3 balls with a polished surface were used. The tests were carried out at a load of 5 N, a slip speed of 0.105 m/s, and a friction radius of 9 mm, whereas measurements were made over the course of 6000 revolutions. Wear resistance was determined on the basis of measuring the size of the groove profile (wear). Groove geometry was measured with the use of the Veeco optical profilometer, the same one used for surface topography testing, while its cross-section area was calculated by the Vision program, version 4.10. Wear rate (Wv) was determined according to the following equation:

where V—worn material volume calculated on the basis of the average size of the groove’s cross-section area, Fn—axial force, and s—total friction distance covered during 6000 ball revolutions. The wear indexes and changes in the friction coefficient were presented on graphs, and a Veeco optical profilometer was used to illustrate the wear tracks.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Cross-Section Microstructure

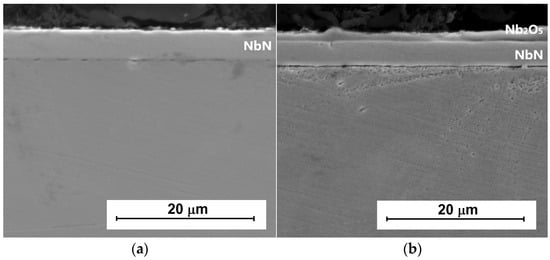

Figure 1 shows the microstructure of the NbN coating (Figure 1a) produced on AISI 316L steel and the NbN coating with an oxidized layer (Figure 1b). Previously published XRD studies have shown that the produced coating is mainly composed of cubic δ-NbN, and the oxidized layer is composed of orthorhombic Nb2O5 with a newly formed tetragonal Nb4N3 phase located beneath the oxide layer [23]. The NbN coating was 5.5 µm thick, while after oxidation its thickness decreased to 3.8 µm, in favor of the Nb2O5 layer (1.7 µm).

Figure 1.

Cross-sections of (a) NbN and (b) oxidized NbN coatings on AISI 316L steel, magnification 2500×.

3.2. Surface Topography and Roughness

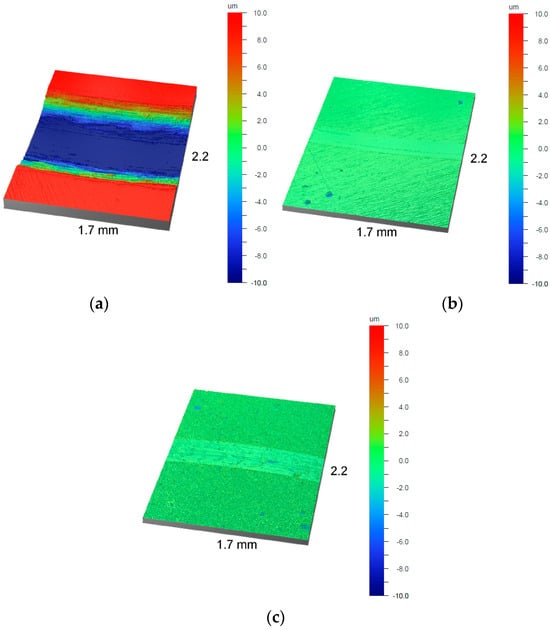

Observations using an optical profilometer were carried out to analyze the surface topography of the samples. Figure 2a presents an image of the surface of AISI 316L steel in its initial state. The image mainly shows scratches resulting from grinding the surface of the sample with sandpaper. The red peaks visible in Figure 2b refer to niobium nitrides deposited on the coating surface (nodular defects), which is a typical phenomenon for the magnetron sputtering process [40,41,42,43,44] and increases the surface roughness of the steel [23]. In the case of the oxidized layer, a clear surface development is observed and many new peaks appear on the surface, associated with the formation of new oxide agglomerates (Figure 2c), which cause even greater development of the coating surface [23].

Figure 2.

Optical profilometer images of the investigated surfaces: (a) AISI 316L steel in the initial state, (b) NbN-deposited coating, and (c) thermally oxidized NbN coating.

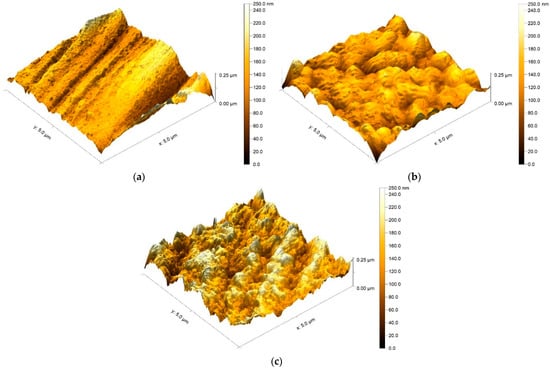

The AFM studies of the surface topography of the coatings were performed between the larger agglomerates visible in Figure 2b,c. It can be seen on a micro scale that the unevenness created by grinding the steel surface was smoothed after the NbN coating was produced, which resulted in a reduction in the Ra and Rt parameters. (Figure 3a,b, Table 1). New irregularities caused by the formation of sputtered niobium nitride are visible. Thermal oxidation of the coating surface led to its further development (Figure 3c) and a marked increase in the Ra and Rt parameters compared to the NbN coating (Table 1), but the values were not as high as those for the steel in its initial state.

Figure 3.

AFM images of the investigated surfaces: (a) AISI 316L steel in the initial state, (b) NbN-deposited coating, and (c) thermally oxidized NbN coating.

Table 1.

Roughness parameters Ra and Rt of the investigated surfaces: AISI 316L steel in the initial state, NbN-deposited coating, and thermally oxidized NbN coating.

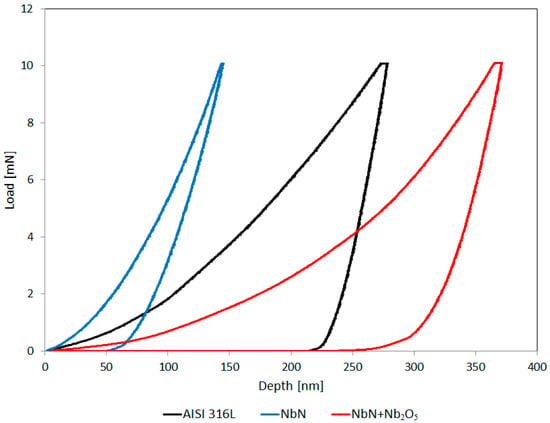

3.3. Nanoindentation

The nanohardness of the AISI 316L steel in its initial state presented in Table 2 is relatively high (5.79 GPa, i.e., approximately 590 HV), which results from the deformation of the austenitic structure in the thin surface layer during grinding and the formation of deformation martensite, which has already been discussed in other studies [6,45]. The hardness of this steel measured at 50 g is approximately 300 HV [6,23]. The NbN coating had almost five times greater hardness, a more than 80 GPa higher Young’s modulus (Er), and two orders of magnitude greater resistance to plastic deformation (H3/E2), which result from strong covalent bonds and greater toughness, compared to the steel in its initial state (Table 2). This is confirmed by the narrow hysteresis loop determined for the force versus displacement and the maximum indentation depth not exceeding 150 nm with the permanent plastic deformation to a depth of 50 nm for the NbN coating (Figure 4). In the case of the oxidized Nb2O5 layer with ionic bonds, the hardness, Young’s modulus, and resistance to plastic deformation are clearly lower, even than the values for AISI 316L steel in the initial state with deformation martensite in the surface layer. Most likely, such low values result from the high brittleness of the oxide layer. The tetragonal Nb4N3 phase, with a lower nitrogen content in relation to the cubic δ-NbN phase, which is formed under the Nb2O5 layer during oxidation [23], may also have an impact on the reduction of mechanical properties. In this case the hysteresis loop was wide, with the total elastic and plastic deformation depth reaching 370 nm and the permanent plastic deformation depth exceeding 250 nm (Figure 4). In the work of Gelamo et al. [46], a 300 nm thick N2O5 coating produced on a Ti6Al4V alloy using the reactive sputtering technique showed slightly higher nanohardness (5.62 GPa) measured under a lower load of 2 mN. Dinu et al. [47] obtained a similar nanohardness value for the Nb2O5 coating produced on the same titanium alloy by electron beam deposition, and the elastic modulus was close to that of the Nb2O5 layer produced on the δ-NbN coating in this work. On the other hand, Ding et al. [48] fabricated gradient Mg-Nb2O5 coatings with a pure Nb2O5 coating on top on an AZ31 alloy using the magnetron sputtering technique, with a total thickness ranging from 1.98 to 5.42 um, which exhibited nanohardness ranging from 2.1 to 3.6 GPa, an elastic modulus from 56.4 to 89.8 GPa and an H3/E2 ratio from 0.0029 to 0.0058, measured at a load of 2 mN. These values are similar to those obtained for the Nb2O5 layer produced in the thermal oxidation process on the δ-NbN coating with the formed Nb4N3 interlayer [23]. Microhardness tests performed using the Vickers method have shown that the tested Nb2O5 layer produced on the δ-NbN coating is almost three times harder than AISI 316L steel [23]. However, it can be concluded that this value, measured at the applied load of 50 g, is influenced by the underlying much harder NbN coating (Table 2).

Table 2.

Hardness (H), reduced Young’s modulus (Er) and resistance to plastic deformation (H3/E2) of AISI 316L steel and NbN and NbN + Nb2O5 coatings.

Figure 4.

Force-displacement curves obtained in nanoindentation tests.

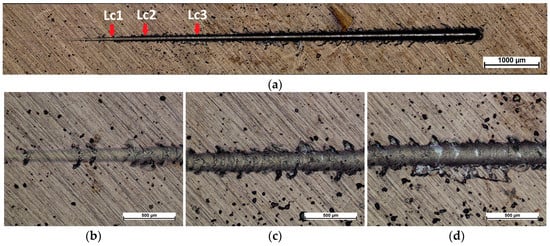

3.4. Adhesion

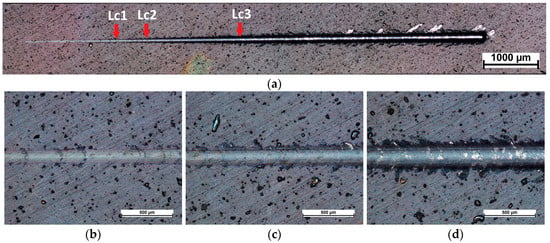

Figure 5 and Figure 6 show scratches made using the scratch-test method. In the case of the NbN coating and the NbN coating with the Nb2O5 layer, four stages are visible: initial deformation of the coating, first cohesive failures (Lc1), adhesive damages (Lc2), and breakthrough of the coating (Lc3). Minor wear is visible in the case of the NbN coating (Figure 5a), where at the beginning of the scratch mainly plastic deformation is visible, followed by cohesive cracks around the scratch (Figure 5b), with the first crack (Lc1) appearing at a load of about 8.2 N (Figure 5a,b, Table 3). Singh et al. [22] observed that, for a coating containing mainly cubic δ-NbN produced by magnetron sputtering on stainless steel, similar values of the critical load at which the first cracks appear were obtained, and they ranged from 8 to 12 N depending on the nitrogen content in the working chamber. In the case of the NbN coating with an oxide layer, the first cohesive damages (Lc1) started at a load of 7.9 N (Figure 6a,b, Table 3). Similar values were also observed for both variants in the case of the Lc2 parameter, which determines the first adhesive damage of the coating, and it was 11.9 N and 11.3 N for the NbN coating and the oxidized coating with the Nb2O5 top layer, respectively (Figure 5a,c and Figure 6a,c, Table 3). However, the Lc3 parameter was significantly higher in the case of the oxidized coating (Figure 5a,d and Figure 6a,d, Table 3), which proves that annealing at the oxidation temperature led to improved adhesion of the NbN coating to the substrate, which could be the result of diffusion processes at the substrate–coating interface. Yi et al. [49] produced a wear-resistant NbN gradient coating on TA15 titanium alloy using the double glowing plasma alloying technique, which showed mainly delamination of the coating at the edges of the scratch. The authors did not determine the type of NbN structure but showed that the adhesion of the NbN coating was significantly improved after the Nb pre-diffusion process.

Figure 5.

Images of (a) a scratch performed on the surface of NbN coating and areas of critical loads (b) Lc1, (c) Lc2, and (d) Lc3.

Figure 6.

Images of (a) a scratch performed on the surface of oxidized NbN coating and areas of critical loads (b) Lc1, (c) Lc2, and (d) Lc3.

Table 3.

Critical loads Lc1, Lc2, and Lc3 of NbN and NbN + Nb2O5 coatings obtained from scratch-test measurements.

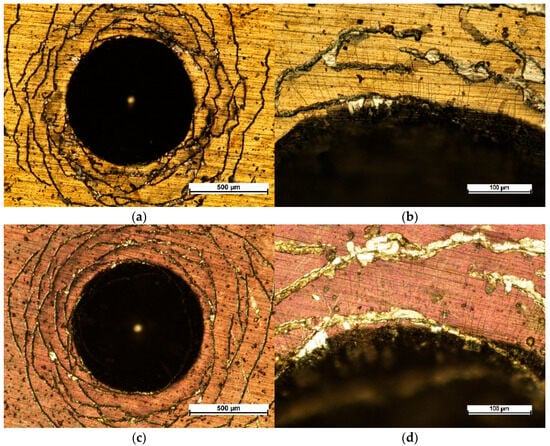

Adhesion tests performed with a Rockwell indenter showed a type of coating damage not classified in the VDI3198 standard [38,39]. A number of cracks are visible on the perimeter near the indentations (Figure 7a,c) and likely result from plastic deformation of the soft austenitic steel in the vicinity of the indentation and its impact on much harder and brittle coatings. There are also small radial cracks extending from the edges of the indentations, and minor chipping of the coatings is also visible (Figure 7b,d), but this is more pronounced for the oxidized NbN coating. Without taking into account large circumferential cracks near the indentations, this type of damage (radial cracks and chippings) would in both cases be classified as HF3 adhesion according to the VDI3198 standard.

Figure 7.

Images of indents after adhesion Rockwell tests of (a,b) NbN coating and (c,d) oxidized NbN coating, (a,c)—50×, (b,d)—200×.

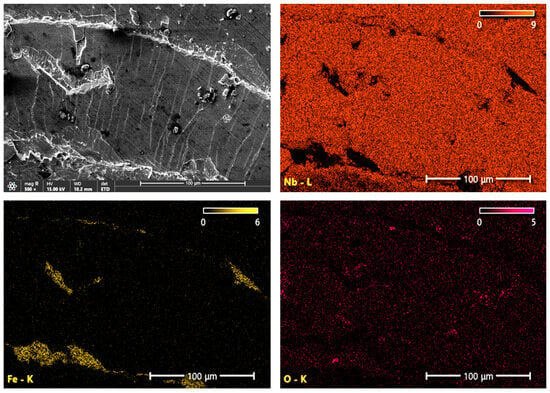

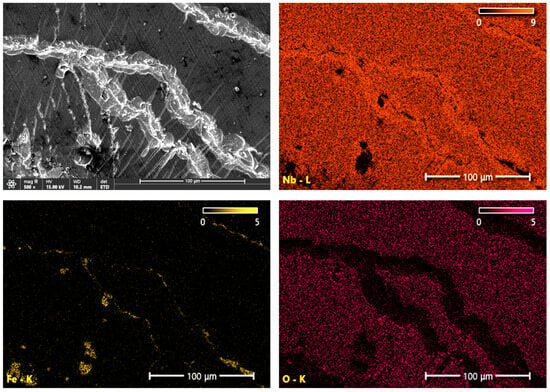

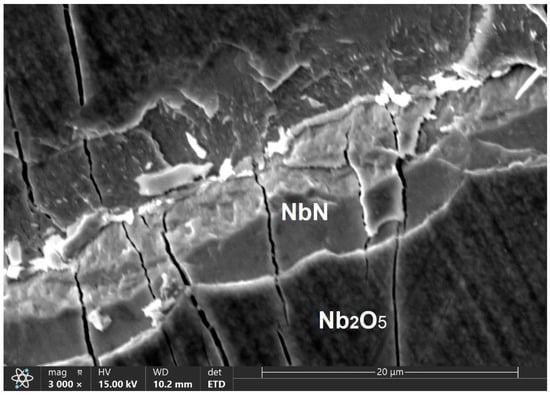

Figure 8 and Figure 9 show the distribution of Nb, Fe and O elements in the form of mappings on the surface of coating damages near the edges of the indentations made with the diamond Rockwell cone. The NbN coating shows visible flaking, exposing the substrate and revealing iron-rich, niobium-depleted areas. Small concentrations of oxygen are also visible in the damaged areas, which may be due to the substrate passivation or corrosion (Figure 8). In the case of the oxidized NbN coating, there are fewer delamination sites, which is visible in the smaller number of iron-enriched areas (Figure 9). Based on the distribution of oxygen and niobium contents, it can be concluded that the most extensive damage was mainly confined to the top Nb2O5 layer (Figure 10), but cracking of the NbN coating is also visible in the area of destruction of the oxide layer, which reveals the signal from the iron (Figure 9). The obtained results indicating lower strength of the brittle oxide layer are consistent with the results of adhesion tests using the scratch method, where the lower critical load values of Lc1 and Lc2 were obtained (Table 3). Therefore, the chipping visible in Figure 7d is mainly the result of poorer adhesion of the Nb2O5 layer to the NbN coating. Moreover, heating of the coating during oxidation could have led to a stronger bonding of the NbN coating with the substrate, which is visible by fewer damages reaching the surface of the substrate (fewer areas containing iron and depleted in niobium) (Figure 9), and which has already been confirmed by scratch test measurements (Table 3).

Figure 8.

SEM image of the studied area and images of Nb, Fe, and O element distributions on the surface of the NbN coating in the region of cracking near the edge of the Rockwell cone indentation.

Figure 9.

SEM image of the studied area and images of Nb, Fe, and O element distributions on the surface of the oxidized NbN coating in the region of cracking near the edge of the Rockwell cone indentation.

Figure 10.

Cracked region on the oxidized NbN coating near the edge of the indentation.

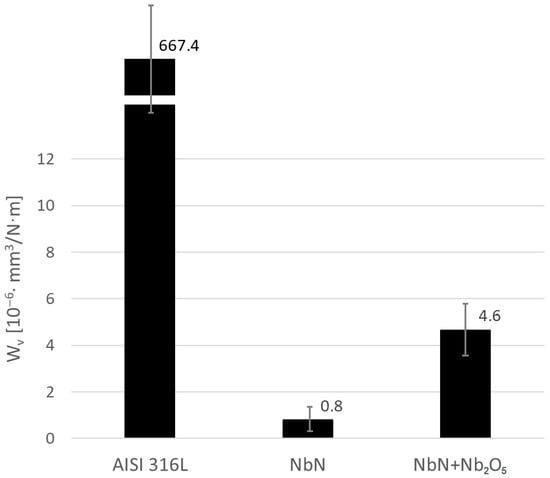

3.5. Wear

Based on the graph of the friction coefficient as a function of revolutions obtained in the “ball-on-disk” method, it can be stated that initially (up to approximately 800 revolutions) the lowest coefficient of friction of the tested surfaces was characterized by the NbN coating, while the highest was for the 316L steel (Figure 11). After running-in and exceeding 2000 revolutions, the coefficient of friction for the NbN coating reached a value of about 1 and showed the highest value compared to the other variants. Such a high coefficient may result from the presence of hard agglomerates of niobium nitrides [23] on the coating surface (Figure 2b). However, due to its high hardness (Table 2), the NbN coating showed the lowest wear index (Figure 12b and Figure 13), three orders of magnitude smaller than AISI 316L steel. Singh et al. [22] achieved a wear index higher by about 3 orders of magnitude in wear tests of a cubic δ-NbN coating produced on stainless steel by magnetron spraying, conducted using an AISI 52100 steel ball (60 HRC) under a load of 6 N. In turn, Stone et al. [16], using a 6 mm diameter Si3N4 ceramic counter-sample at a load of 1 N, obtained a friction coefficient of 0.89 for a cubic δ-NbN coating produced on Inconel 718 using an unbalanced magnetron sputtering apparatus. This value is also high, especially considering the low applied load. Subsequent researchers’ oxidation of the coating during friction at temperatures of 350 °C and 750 °C resulted in a reduction in the friction coefficient to 0.7 and 0.53, respectively, due to the formation of a monoclinic Nb2O5 layer at 750 °C. The average value of the friction coefficient of AISI 316L steel in the initial state and of the thermally oxidized NbN coating measured after running-in from a value of about 1000 revolutions was 0.72 and 0.76, respectively (Figure 11). After oxidation of the NbN coating in air at a temperature of 480 °C, a reduction in the friction coefficient of approximately 0.24 was observed as a result of the formation of an orthorhombic Nb2O5 layer [23]. Due to the low hardness of austenitic steel (Table 2), its abrasive wear was very high (Figure 12a and Figure 13).

Figure 11.

Graph of coefficient of friction as a function of revolutions for AISI 316L steel and NbN and NbN + Nb2O5 coatings.

Figure 12.

Images of wear tracks on the surface of (a) AISI 316L steel, (b) NbN coating, and (c) oxidized NbN coating.

Figure 13.

Wear indexes Wv for AISI 316L steel and NbN and NbN + Nb2O5 coatings.

It should be noted that the coefficient of friction and the wear index are not necessarily directly correlated and may be governed by different dominant wear mechanisms. The oxide layer, despite having the highest roughness (Figure 2c and Figure 3c, Table 1), showed a lower coefficient of friction than the non-oxidized NbN coating (Figure 11). The peaks originating from agglomerate and irregularities on the surface of the brittle, ceramic oxide layer (Figure 2c and Figure 3c) were lapped at the initial stage of friction, which resulted in a lower friction coefficient compared to the NbN coating. At the same time, the limited load-bearing capacity and brittle nature of the Nb2O5 layer promote microcracking and material removal during sliding. Conversely, the higher friction coefficient of the non-oxidized NbN coating is associated with hard surface asperities, while its high load-bearing capacity effectively limits material loss. The Nb2O5 layer provides constant lubrication and reduces the coefficient of friction, likely due to filling the cavities in the layer (Figure 3c) with detached oxides, which has already been confirmed for various types of oxide layers [50,51,52]. However, due to the ball running in of the brittle ceramic layer and its lower hardness, the wear index was almost 6 times greater than that of the NbN coating without the oxidation process (Figure 12c and Figure 13). Ding et al. [48] showed that with lower roughness of Nb2O5 coatings (Ra = 6.8–22.1 nm—AFM) produced on an AZ31 alloy using the magnetron sputtering technique, an average friction coefficient ranging from 0.157 to 0.408 measured at a load of 1N can be achieved, but with a significant increase in the wear rate, most likely due to the brittle coatings and the soft substrate.

Despite the lower hardness and higher wear rate, which are paradoxically accompanied by a lower coefficient of friction of the oxidized NbN, the coating with a brittle surface Nb2O5 layer compared to the non-oxidized NbN coating exhibits significantly higher corrosion resistance in the presence of chlorides, i.e., lower corrosion current density (icorr), higher polarization resistance (Rpol), with breakthrough potential (Epit) comparable to the NbN coating and higher than for the steel in its initial state, and additionally higher bioactivity in simulated body fluid (SBF) compared to AISI 316L steel with and without the NbN coating, as demonstrated in a previous study [23]. Notably, the wear rate of the oxidized NbN coating with the Nb2O5 layer remains 145 times lower than that of the steel in its initial state, which does not exclude its potential use in implantology. Furthermore, it has been proven that the thermal oxidation process can improve the adhesion of the NbN coating to the substrate.

4. Conclusions

Based on the results obtained in this and the previous study [23], the following conclusions can be drawn:

- Thermal oxidation of the NbN coating at 480 °C led to the formation of a Nb2O5 surface layer, which caused increased surface roughness, reduced nanohardness, and resistance to plastic deformation due to the brittle nature of the oxide. This confirms that the oxidation process significantly modifies the mechanical response of the NbN-based coating system rather than merely altering its surface chemistry.

- The Nb2O5 layer exhibited lower adhesion to the NbN coating, as evidenced by scratch and Rockwell tests, where earlier delamination and more severe cracking were observed, indicating a change in the dominant failure mechanism from plastic deformation to brittle fracture. At the same time, thermal oxidation additionally enhanced the bonding between the NbN coating and the steel substrate, as indicated by the fewer delamination sites reaching the steel surface and the higher Lc3 value.

- Despite the reduction in mechanical strength, the oxidized NbN coating showed a lower coefficient of friction than the as-deposited NbN coating, likely due to the wear-induced smoothing of the oxide surface. This demonstrates that the Nb2O5 layer plays an active tribological role, although the wear rate was several times higher than that of the non-oxidized coating because of its low hardness and brittleness.

- The improved bioactivity and corrosion resistance of the oxidized NbN coating (proven in a previous study), alongside a wear rate approximately 145 times lower than that of the bare steel, indicate that the oxidized NbN/Nb2O5 system represents a functional compromise between mechanical durability and surface functionality, supporting its potential use in implantological and biomedical applications.

- It has also been shown that the non-oxidized NbN coating is characterized by much higher hardness and a markedly lower wear rate than the oxidized NbN coating; however, previous studies have shown that it exhibits lower biocompatibility and corrosion resistance compared to the oxidized NbN coating with a Nb2O5 top layer. Therefore, the choice between NbN and oxidized NbN coatings should be dictated by application-specific requirements, balancing mechanical loading conditions against corrosion resistance and biocompatibility.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.B. and J.F.; methodology, T.B., J.F. and M.B.; formal analysis, T.B., J.F., M.S. and M.W.; investigation, T.B., J.F., M.S. and M.W.; writing—original draft preparation, T.B. and J.F.; writing—review and editing, T.B.; visualization, T.B., J.F., M.S. and M.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Mamun, M.A.A.; Farha, A.H.; Ufuktepe, Y.; Elsayed-Ali, H.E.; Elmustafa, A.A. Nanoindentation Study of Niobium Nitride Thin Films on Niobium Fabricated by Reactive Pulsed Laser Deposition. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2015, 330, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havey, K.S.; Zabinski, J.S.; Walck, S.D. The Chemistry, Structure, and Resulting Wear Properties of Magnetron-Sputtered NbN Thin Films. Thin Solid Film. 1997, 303, 238–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezirmik, K.V.; Rouhi, S. Influence of Cu Additions on the Mechanical and Wear Properties of NbN Coatings. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2014, 260, 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson-Elli, D.F.; Fung, C.A.; Nordman, J.E. DC Reactive Magnetron Sputtered NbN Thin Films Prepared with and without Hollow Cathode Enhancement. IEEE Trans. Magn. 1991, 27, 1592–1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ufuktepe, Y.; Farha, A.H.; Kimura, S.I.; Hajiri, T.; Imura, K.; Mamun, M.A.; Karadag, F.; Elmustafa, A.A.; Elsayed-Ali, H.E. Superconducting Niobium Nitride Thin Films by Reactive Pulsed Laser Deposition. Thin Solid Film. 2013, 545, 601–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borowski, T. Enhancing the Corrosion Resistance of Austenitic Steel Using Active Screen Plasma Nitriding and Nitrocarburising. Materials 2021, 14, 3320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nouri, A.; Wen, C. Stainless Steels in Orthopedics. In Structural Biomaterials; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 67–101. ISBN 978-0-12-818831-6. [Google Scholar]

- Heidari Laybidi, F.; Bahrami, A. Antibacterial Properties of ZnO-Containing Bioactive Glass Coatings for Biomedical Applications. Mater. Lett. 2024, 365, 136433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beni, B.H.; Bahrami, A.; Rajabinezhad, M.; Abbasi, M.S.; Laybidi, F.H. Electrophoretic Deposition of Bioactive Glass 58S-xSi3N4 (0 < x < 20 wt.%) Nanocomposite Coating on AISI 316L Stainless Steel Substrate for Biomedical Applications. Surf. Interfaces 2024, 55, 105380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, C.; De Mongeot, F.B.; Ferrando, G.; Manzato, G.; Meyer, M.; Parodi, L.; Sgobba, S.; Sortino, M.; Vaglio, E. Study on Properties of AISI 316L Produced by Laser Powder Bed Fusion for High Energy Physics Applications. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. A Accel. Spectrometers Detect. Assoc. Equip. 2023, 1055, 168459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacerda, F.G.B.; Tavares, S.S.M.; Perez, G.; Garcia, P.S.P.; Pimenta, A.R. Failure Investigation of an AISI 316L Pipe of the Flare System in an Off-Shore Oil Platform. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2025, 167, 108939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hovsepian, P.E.; Ehiasarian, A.P.; Purandare, Y.P.; Biswas, B.; Pérez, F.J.; Lasanta, M.I.; De Miguel, M.T.; Illana, A.; Juez-Lorenzo, M.; Muelas, R.; et al. Performance of HIPIMS Deposited CrN/NbN Nanostructured Coatings Exposed to 650 °C in Pure Steam Environment. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2016, 179, 110–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purandare, Y.P.; Robinson, G.L.; Ehiasarian, A.P.; Hovsepian, P.E. Investigation of High Power Impulse Magnetron Sputtering Deposited Nanoscale CrN/NbN Multilayer Coating for Tribocorrosion Resistance. Wear 2020, 452–453, 203312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Jia, J.; Cao, X.; Zhang, G.; Ding, Q. Effect of Ag Contents on the Microstructure and Tribological Behaviors of NbN–Ag Coatings at Elevated Temperatures. Vacuum 2022, 204, 111330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Peng, S.; Li, Z.; Jiang, S.; Xie, Z.-H.; Munroe, P. The Influence of Semiconducting Properties of Passive Films on the Cavitation Erosion Resistance of a NbN Nanoceramic Coating. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2021, 71, 105406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, D.S.; Migas, J.; Martini, A.; Smith, T.; Muratore, C.; Voevodin, A.A.; Aouadi, S.M. Adaptive NbN/Ag Coatings for High Temperature Tribological Applications. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2012, 206, 4316–4321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Ding, J.C.; Kwon, S.-H.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, S. Corrosion Resistance and Conductivity of NbN-Coated 316L Stainless Steel Bipolar Plates for Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cells. Corros. Sci. 2022, 196, 110042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathote, D.; Kumari, P.; Singh, V.; Jaiswal, D.; Gautam, R.K.; Behera, C.K. Biocompatibility Evaluation, Wettability, and Scratch Behavior of Ta-Coated 316L Stainless Steel by DC Magnetron Sputtering for the Orthopedic Applications. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2023, 459, 129392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, J.; Huang, S.; Guo, X.; Chen, D.; Shen, G.; Chen, Z.; Qian, J.; Liang, Y.; Kang, Z.; Lo, K.-H.; et al. Effect of Target Current on Microstructure, Color and Properties of Titanium Nitride/Titanium Carbonitride Films via Mid-Frequency Magnetron Sputtering. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2025, 333, 130375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baba, K.; Hatada, R.; Udoh, K.; Yasuda, K. Structure and Properties of NbN and TaN Films Prepared by Ion Beam Assisted Deposition. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. B Beam Interact. Mater. At. 1997, 127–128, 841–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Sun, J.; Sun, J.; Lv, Y.; Li, S.; Ji, S.; Wen, Z. Niobium Nitride Modified AISI 304 Stainless Steel Bipolar Plate for Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cell. J. Power Sources 2012, 199, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.; Krishnamurthy, N.; Suri, A.K. Adhesion and Wear Studies of Magnetron Sputtered NbN Films. Tribol. Int. 2012, 50, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borowski, T.; Rospondek, J.; Betiuk, M.; Adamczyk-Cieślak, B.; Spychalski, M. Influence of Magnetron Sputtering-Deposited Niobium Nitride Coating and Its Thermal Oxidation on the Properties of AISI 316L Steel in Terms of Its Medical Applications. Materials 2023, 16, 6890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, K.; Li, X.; Tian, L.; Dong, H. Active Screen Plasma Surface Co-Alloying of 316 Austenitic Stainless Steel with Both Nitrogen and Niobium for the Application of Bipolar Plates in Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cells. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2015, 40, 10281–10292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagarajan, S.; Raman, V.; Rajendran, N. Synthesis and Electrochemical Characterization of Porous Niobium Oxide Coated 316L SS for Orthopedic Applications. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2010, 119, 363–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivares-Navarrete, R.; Olaya, J.J.; Ramírez, C.; Rodil, S.E. Biocompatibility of Niobium Coatings. Coatings 2011, 1, 72–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenbarth, E.; Velten, D.; Breme, J. Biomimetic Implant Coatings. Biomol. Eng. 2007, 24, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PremKumar, K.; Duraipandy, N.; Kiran Manikantan Syamala Rajendran, N. Antibacterial Effects, Biocompatibility and Electrochemical Behavior of Zinc Incorporated Niobium Oxide Coating on 316L SS for Biomedical Applications. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018, 427, 1166–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katta, P.P.; Nalliyan, R. Corrosion Resistance with Self-Healing Behavior and Biocompatibility of Ce Incorporated Niobium Oxide Coated 316L SS for Orthopedic Applications. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2019, 375, 715–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Malik, G.; Adalati, R.; Chawla, V.; Pandey, M.K.; Chandra, R. Tuning the Wettability of Highly Transparent Nb2O5 Nano-Sliced Coatings to Enhance Anti-Corrosion Property. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2021, 123, 105513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieretti, E.F.; Pillis, M.F. Electrochemical Behavior of Nb2O5 Films Produced by Magnetron Sputtering. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2018, 13, 8108–8115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillis, M.F.; Geribola, G.A.; Scheidt, G.; De Araújo, E.G.; De Oliveira, M.C.L.; Antunes, R.A. Corrosion of Thin, Magnetron Sputtered Nb 2 O 5 Films. Corros. Sci. 2016, 102, 317–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Z.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, D.; Zuo, J.; Wang, Z. Microstructure, Mechanical Properties and Oxidation Behaviors of Magnetron Sputtered NbNx Coatings. J. Alloys Compd. 2016, 675, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.G.; Yuan, H.; Jiang, Z.T.; Pan, N.; Lei, M.K. Phase Composition and Mechanical Properties of Homostructure NbN Nanocomposite Coatings Deposited by Modulated Pulsed Power Magnetron Sputtering. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2020, 385, 125387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharjee, A.; Amarnath, L.; Dutta, K. Ratcheting Behaviour of a Sensitized Non-Conventional Austenitic Stainless Steel. Procedia Eng. 2017, 184, 756–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhery, M.H.; Chandrabhan, V.; Jeenat, A.; Ruby, A.; Saman, Z. Intergranular Corrosion. In Handbook of Corrosion Engineering; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; pp. 83–89. ISBN 978-0-323-95185-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nečas, D.; Klapetek, P. Gwyddion: An Open-Source Software for SPM Data Analysis. Open Phys. 2012, 10, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidakis, N.; Antoniadis, A.; Bilalis, N. The VDI 3198 Indentation Test Evaluation of a Reliable Qualitative Control for Layered Compounds. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2003, 143–144, 481–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenz, B.; Hasselbruch, H.; Mehner, A. Automated Evaluation of Rockwell Adhesion Tests for PVD Coatings Using Convolutional Neural Networks. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2020, 385, 125365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simova, V.; Zabeida, O.; Varela, L.B.; Qian, J.; Klemberg-Sapieha, J.-E.; Martinu, L. Tuning the Mechanical Properties and Toughness of TiAlN Coatings Deposited by Low Duty Cycle Pulsed Magnetron Sputtering from a Rotating Cylindrical Target. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2025, 511, 132262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.; Zhao, X.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, B.; Zhang, H.; Chen, Z.; Bao, C.; Guan, W.; Zhu, L. High Deposition Rates via Radio-Frequency Magnetron Sputtering for Thin Electrolyte Fabrication in Solid Oxide Fuel Cell Applications. J. Power Sources 2025, 646, 237259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucharska, B.; Czarniak, P.; Kulikowski, K.; Krawczyńska, A.; Rożniatowski, K.; Kubacki, J.; Szymanowski, K.; Panjan, P.; Sobiecki, J.R. Comparison Study of PVD Coatings: TiN/AlTiN, TiN and TiAlSiN Used in Wood Machining. Materials 2022, 15, 7159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucharska, B.; Bochra, K.; Wierzchoń, T.; Sobiecki, J.R. Protective Magnetron Sputtering Physical Vapor Deposition Coatings for Space Application. Coatings 2024, 14, 1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahal, Y.P.; Gu, B.; Su, Z.; Wang, S. Investigating the Effect of Sputtering Particle Energy on the Crystal Orientation and Microstructure of NbN Thin Films. Coatings 2025, 15, 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borowski, T.; Wójcik, H.; Spychalski, M.; Adamczyk-Cieślak, B. Wear and Corrosion Resistance of Thermally Formed Decorative Oxide Layers on Austenitic Steel. Metals 2025, 15, 707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentim Gelamo, R.; Bueno Leite, N.; Amadeu, N.; Reis Pedreira Muniz Tavares, M.; Oberschmidt, D.; Klemm, S.; Fleck, C.; Cakir, C.-T.; Radtke, M.; Aparecido Moreto, J. Exploring the Nb2O5 Coating Deposited on the Ti-6Al-4V Alloy by a Novel GE-XANES Technique and Nanoindentation Load-Depth. Mater. Lett. 2024, 355, 135584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinu, M.; Braic, L.; Padmanabhan, S.C.; Morris, M.A.; Titorencu, I.; Pruna, V.; Parau, A.; Romanchikova, N.; Petrik, L.F.; Vladescu, A. Characterization of Electron Beam Deposited Nb2O5 Coatings for Biomedical Applications. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2020, 103, 103582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Z.; Yuan, Q.; Wang, H.; Tang, Y.; Tan, Y.; He, Q. Microstructure and Properties of Nb2O5/Mg Gradient Coating on AZ31 Magnesium Alloy by Magnetron Sputtering. Ceram. Int. 2023, 49, 154–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, J.; Miao, Q.; Liang, W.; Ding, Z.; Qi, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, H.; Yin, M. A Novel Nb Pre-Diffusion Method for Fabricating Wear-Resistant NbN Ceramic Gradient Coating. Vacuum 2021, 185, 109993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Du, Y.; Pei, X.; Wang, H.; Hua, D.; Zhou, Q.; Wang, H. Unlocking Metallic Glasses Ultra-Low Friction via High-Entropy Effect and Oxidation. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2025, 301, 110507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, C.; Xie, H.; Liu, J.; Lei, B.; Zhang, R. Improvement of Ti3SiC2/SiC Composite Ceramic Friction and Wear Behavior by Mechanical-Friction Oxidation Synergism in a Wide Temperature Domain of SiC. Wear 2025, 572–573, 205984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Ma, X.; Zhang, S.; Hou, L.; Kim, K.H. One-Step Fabrication of Wear Resistant and Friction-Reducing Al2O3/MoS2 Nanocomposite Coatings on 2A50 Aluminum Alloy by Plasma Electrolytic Oxidation with MoS2 Nanoparticle Additive. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2025, 497, 131796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.