Abstract

Micro-arc oxidation (MAO) coatings were produced on commercially pure titanium Grade 2 using a composite electrolyte containing sodium phosphate (Na3PO4) and sodium silicate (Na2SiO3), while varying the applied voltage. The surface morphology, phase composition, and structural features of the coatings were examined using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and X-ray diffraction (XRD). The coatings exhibited a characteristic crater-like microporous surface morphology associated with the micro-arc discharge process. XRD analysis confirmed the formation of mixed TiO2 phases in the anatase and rutile modifications, with higher voltages promoting the growth of the thermodynamically stable rutile phase. Corrosion and tribological properties were evaluated in a 3.5 wt.% NaCl solution using potentiodynamic polarization and a ball-on-disc test configuration, respectively. The results revealed a substantial improvement in both corrosion resistance and wear performance compared with bare titanium. The coating formed at 300 V demonstrated the highest wear resistance due to its denser microstructure, whereas the coating produced at 350 V exhibited the lowest friction coefficient and the greatest corrosion resistance, attributed to the increased rutile content. Overall, MAO coatings fabricated in the phosphate–silicate electrolyte effectively enhance the combined operational properties of titanium and can be recommended for applications requiring improved wear and corrosion resistance.

1. Introduction

Titanium and its alloys belong to the class of strategically important structural materials widely demanded in the aviation, marine, chemical, and biomedical industries due to their unique combination of physical and mechanical properties [1]. Key advantages of titanium include a high melting point, low specific weight, considerable electrical resistivity, exceptional strength, non-magnetic nature, bioinertness, and resistance to corrosion in atmospheric, aqueous, and aggressive chemical environments [2]. Owing to these characteristics, titanium alloys are employed in the fabrication of critical components of modern aircraft, marine vessels, power-generation systems, and medical devices [3,4]. Despite these outstanding properties, titanium exhibits relatively low hardness and insufficient wear resistance, particularly under conditions involving friction, impact–abrasive interaction, and cyclic loading. These operational limitations significantly reduce the service life of titanium components and may lead to premature failure under real working conditions [5]. A conventional approach to enhancing the surface strength of titanium is hard anodizing; however, this process is associated with several drawbacks, including the limited hardness of the resulting oxide layer [6], moderate corrosion resistance [7], and the overall complexity of the technological procedure [8]. Collectively, these factors may adversely affect the fatigue strength and service lifetime of titanium parts.

Micro-arc oxidation (MAO), also referred to as plasma electrolytic oxidation (PEO), is a highly effective method for surface modification of light metals and their alloys such as Al, Mg, Ti, and related systems [9,10]. In the conventional process configuration, a specimen made of these metals serves as the anode, while stainless steel is used as the cathode, both immersed in an aqueous electrolyte [11]. When subjected to a high-voltage pulsed electric field, a ceramic oxide coating that is metallurgically bonded to the substrate is formed on the anode surface. The generation of the coating is governed by the combined action of thermochemical, plasma-chemical, and electrochemical mechanisms [12].

The operating principle of MAO is based on the utilization of high-voltage discharge energy, which initiates localized micro-melting followed by rapid solidification of metal oxides formed on the surface of the specimen immersed in the electrolyte. During electrolysis, oxygen is intensively released at the anode and subsequently activated by micro-arc discharges, resulting in oxidation of the metal surface and growth of the oxide layer [13]. Breakdown of the passive oxide film occurs extensively and is accompanied by a sharp, short-term increase in current density, which may reach up to 10 A/cm2 [14]. As the coating thickness increases and its dielectric strength improves, the intensity of micro-arc discharges gradually decreases, leading to a stabilization of the process and a transition to the stage in which a dense ceramic layer with a well-developed microstructure is formed.

Energy transfer to the metal surface during micro-arc oxidation occurs through a plasma layer in the form of nonequilibrium electrical discharges of a specific nature. According to Raizer Yu. P. [15], these discharges belong to the class of distributed (film-type) discharges and are characterized by relatively low gas temperatures. They exhibit a diffusion-type attachment to the electrolyte surface, which acts as a “liquid electrode.”

Current density is one of the key technological parameters of the micro-arc oxidation process, as it governs the behavior of plasma–electrolytic reactions and the resulting coating microstructure. To maintain stable plasma electrolysis conditions, the current density is typically kept within the range of 0.01–0.3 A/cm2 [16,17,18]. As the oxide layer grows, a characteristic change in voltage is observed: at the initial stage, the voltage increases rapidly, after which the rate of increase slows down until steady-state conditions are reached, corresponding to a stabilized plasma discharge.

The critical rate of voltage increase corresponds to the onset of spark discharge on the anode surface. The breakdown voltage strongly depends on the specific metal–electrolyte combination and typically falls within the range of 120–350 V. Once the process transitions to the stage of stable micro-arc discharges, a durable ceramic coating is formed on the surface, characterized by high hardness, wear resistance, corrosion resistance, and strong adhesion to the substrate. The thickness of the oxide layer is determined by the loading parameters and may vary from 5 to 500 µm [19,20,21,22].

The treatment of titanium and its alloys by the MAO method enables a substantial improvement in their surface properties, making these materials particularly promising for use in tribological pairs operating at high sliding speeds and elevated contact stresses. As a result, micro-arc oxidation technology is increasingly being adopted in the aerospace, aviation, automotive, energy, and mechanical engineering industries [23].

One of the key factors determining the effectiveness of micro-arc oxidation (MAO) is the proper selection of the electrolyte. The chemical composition of the solution, its ability to dissolve or passivate the metal, as well as its electrical conductivity, directly influence the onset of spark discharge, the intensity of micro-arc processes, the coating growth rate, and the development of its microstructure. Therefore, the choice of an optimal metal–electrolyte system is a critical step in establishing MAO processing conditions. Polarization tests are widely used to evaluate the behavior of metals in different solutions, allowing the assessment of tendencies toward dissolution or passivation and thereby enabling the selection of suitable electrolytes [24,25,26,27,28,29].

In the literature, electrolytes for MAO are conventionally classified into six groups.

- (1)

- The first group includes solutions that cause rapid dissolution of the metal, such as NaCl, NaClO3, NaOH, HCl, and NaNO3. These systems are rarely used for producing durable oxide coatings but are useful for preliminary surface activation.

- (2)

- The second group comprises solutions that induce slow dissolution, such as H2SO4 or Na2SO4, leading to a more stable growth of the oxide layer.

- (3)

- The third group consists of electrolytes that cause metal passivation within a narrow voltage range, for example, sodium acetate or phosphoric acid.

- (4)

- The fourth group includes fluoride-containing electrolytes (e.g., NaF, KF), which exhibit complex behavior but often facilitate a smooth transition into the spark discharge regime.

- (5)

- The fifth group contains solutions that produce weak passivation.

- (6)

- The sixth group includes electrolytes that promote strong passivation, such as boric acids and salts of phosphoric, carbonic, and inorganic acids, as well as polymeric anions (silicates, aluminates, molybdates, tungstates).

In practice, electrolytes belonging to groups 4–6 are considered the most effective for MAO because they enable relatively easy attainment of the spark discharge voltage and support stable formation of a ceramic oxide layer.

In addition to their functional classification based on dissolution behavior, electrolytes are also categorized according to their contribution to the coating composition:

- (a)

- solutions that form the layer solely through oxidation of the metal (i.e., they provide only oxygen);

- (b)

- solutions whose anions are incorporated into the coating and alter its properties (e.g., phosphates, silicate ions);

- (c)

- solutions containing cationic additives (Na+, K+, Al3+, etc.);

- (d)

- suspensions containing solid particles that are transported by cataphoresis and embedded into the growing layer.

Electrolytes of types (b) and (c) are considered particularly promising because they allow intentional modification of the coating by adjusting its phase composition, porosity, microstructure, and functional properties (hardness, wear resistance, corrosion resistance). This enables the production of layers with predefined performance characteristics.

The most widely used electrolytes are silicate-based systems, typically employing sodium or potassium silicate. These are often supplemented with additives that adjust conductivity (Na2CO3, NaOH, KOH), stabilize the structure (Na2B4O7·10H2O, glycerol), or modify the coating (NaAlO2, Na6P6O18). The incorporation of solid particles (oxides, carbides, nitrides, solid lubricants) enables simultaneous MAO and cataphoretic processes, resulting in the formation of composite ceramic layers with enhanced functional properties [30].

The micro-arc oxidation technology is characterized by its simplicity of implementation, high processing efficiency, minimal surface preparation requirements (limited to cleaning and degreasing), and environmental safety. Owing to these advantages, MAO is considered a competitive alternative to conventional vacuum-based and electrochemical coating methods [31]. More broadly, surface oxidation processes play a crucial role in various scientific and technological fields. For example, controlled oxidation of silicon surfaces is a fundamental step in semiconductor manufacturing, enabling precise tuning of electrical and interfacial properties. Similarly, surface oxidation of petroleum pitch is widely used in carbon material technologies to modify structural and physicochemical characteristics. These studies demonstrate that oxidation-based surface modification is a versatile and interdisciplinary approach applicable across materials science, electronics, and energy-related technologies. In this context, micro-arc oxidation can be regarded as an advanced oxidation technique that enables the formation of functional oxide layers with tailored microstructure and properties on valve metals, particularly titanium and its alloys [32].

The aim of the present work is to produce micro-arc oxide coatings on commercially pure titanium using a composite Na3PO4–Na2SiO3 electrolyte and to investigate the effect of the applied voltage on their microstructure, phase composition, and tribocorrosion performance.

2. Materials and Methods

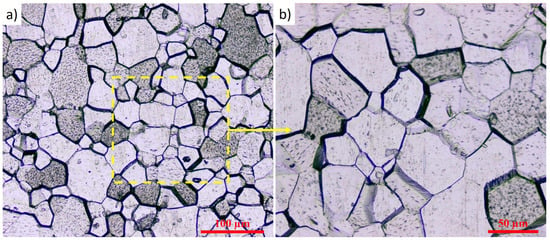

Commercially pure titanium Grade 2 with an average grain size of 34.5 µm was used as the substrate material (Figure 1). For the MAO treatment, the samples were fabricated in the form of plates with dimensions of 20 × 20 × 3 mm. Prior to micro-arc oxidation, the substrate surfaces underwent standard preparation, which included sequential grinding with waterproof abrasive papers of grit sizes #400, #800, #1500, and #2000. After grinding, the samples were polished with diamond paste to a mirror finish, cleaned in an ultrasonic bath using ethanol, and dried with a cold air stream. The chemical composition of Grade 2 titanium is presented in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Microstructure of Grade 2 titanium: (a) ×500; (b) ×1000.

Table 1.

Chemical composition of Grade 2 titanium, wt.%.

To reveal the microstructure, the titanium samples were subjected to electrochemical etching in a solution containing 5 wt.% HF, 15 wt.% HNO3, and 80 wt.% H2O. Etching was performed at 13 V for 20 s. After etching, the microstructure was examined using optical microscopy using an Olympus BX53M optical microscope (Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan).

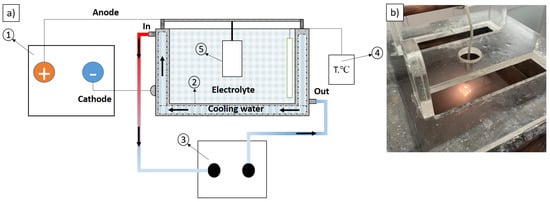

The configuration of the components being treated and the requirement for high processing efficiency impose specific demands on the design of industrial MAO equipment. The most common MAO setup involves full immersion of the sample in an electrolytic chamber (Figure 2). In this study, the anode was a commercially pure Grade 2 titanium sample, while the cathode was a plate made of 316 L stainless steel. The MAO process was carried out under constant-voltage conditions for 20 min. The electrolyte temperature during treatment was maintained below 40 °C by a water-cooling system equipped with a heat exchanger and a temperature controller. The MAO process was performed using a KP-HI-F-40A600V pulsed DC power supply (KP Power Technology Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, China).

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of the micro-arc oxidation setup (a) and the appearance of the working zone of the process (b). 1—pulsed DC power supply, 2—electrolyte tank, 3—heat exchanger, 4—temperature controller, 5—sample.

Two processing regimes were used to form the oxide coatings (Table 2), differing in the applied voltage. The electrolyte was a composite solution consisting of 20 g/L Na3PO4, 10 g/L Na2SiO3, and 10 g/L NaOH. The pulse frequency was 100 Hz. The treatment duration in all experiments was 20 min.

Table 2.

Micro-arc oxidation processing regimes.

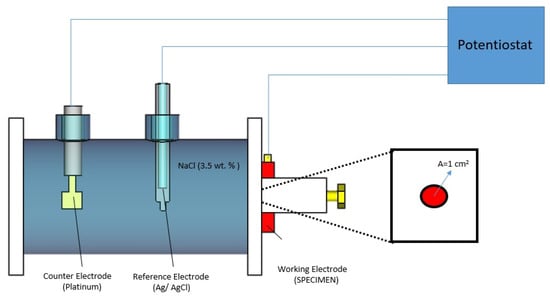

The phase composition of the initial samples and the oxide coatings produced by micro-arc oxidation was examined using a Shimadzu XRD-6000 diffractometer (Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan) (CuKα, λ = 1.54056 Å) operated at 45 kV and 30 mA, with a step size of 0.02° and a scanning range of 2θ = 20–90°. The acquired data were processed using the instrument’s built-in software, and phase identification was performed with the PDF-4+ database provided by the International Centre for Diffraction Data (ICDD). The microstructure, surface morphology, and features of the porous architecture were analyzed by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) using a SEM3200 system (CIQTEK Co., Ltd., Hefei, China). The corrosion behavior of the untreated and MAO-treated samples was evaluated by potentiodynamic polarization in accordance with ASTM G5 [33] using an AUTOLAB PGSTAT302 potentiostat (Metrohm Autolab B.V., Utrecht, The Netherlands) in a three-electrode configuration, where the tested sample served as the working electrode (exposed area ~1 cm2), platinum as the counter electrode, and Ag/AgCl (sat. KCl) as the reference electrode (Figure 3). Prior to polarization, the open circuit potential (OCP) was monitored for 30 min until a stable value was achieved. Potentiodynamic polarization measurements were then carried out in the potential range from −100 mV to +100 mV versus the OCP at a scan rate of 1 mV·s−1. Corrosion tests were performed in a 3.5 wt.% NaCl solution at 25 °C, and each measurement was repeated three times to ensure reproducibility. The corrosion current density was determined by Tafel extrapolation using the AUTOLAB Nova software (Metrohm Autolab B.V., Utrecht, The Netherlands).

Figure 3.

Schematic view of a corrosion electrochemical experiment setup [12].

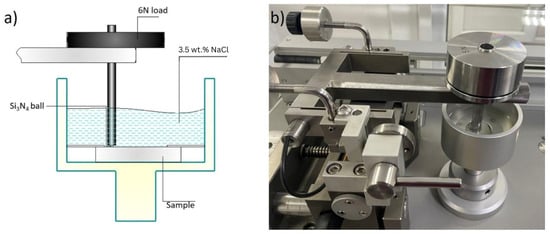

Wear resistance was assessed using a ball-on-disk configuration on an Anton Paar TRB3 tribometer in accordance with ASTM G99 [34], under a normal load of 6 N and a sliding speed of 3 cm/s, employing a 6 mm-diameter Si3N4 ball. The wear track radius was 6 mm. Tribological tests were conducted in a 3.5 wt.% NaCl solution at room temperature (Figure 4). Each test was repeated three times, and the reported friction and wear values represent the average of the measurements.

Figure 4.

Anton Paar TRB3 tribometer used for ball-on-disk testing in a 3.5 wt.% NaCl solution: (a) schematic illustration of the ball-on-disk test configuration; (b) photograph of the experimental setup on the TRB3 tribometer.

The geometry of the wear tracks, including profile depth and cross-sectional area, was measured using a Taylor Hobson profilometer in accordance with ISO 4287 [35]. The volumetric wear coefficient of worn samples was calculated by multiplying the length and cross-sectional area of the wear trace (1) [36]:

where

- •

- S is the worn track section mm2;

- •

- l is the full amplitude mm;

- •

- L is the total measurement distance m;

- •

- Fn is the normal load N;

- •

- WRs is the wear rate of the moving sample mm3/(N·m).

3. Results and Discussion

Surface treatment of titanium by MAO leads to the formation of an oxide layer whose primary crystalline constituents are TiO2 phases—anatase and rutile. The relative proportion of these phases depends on the processing conditions, electrolyte composition, and the alloying elements present in the substrate. It is well established that anatase forms during the early stages of MAO, as its formation requires less energy compared with rutile [37]. This phase remains stable only at relatively low temperatures; however, as the local temperature increases due to micro-arc discharges, anatase becomes metastable and gradually transforms into rutile—the thermodynamically stable TiO2 modification at elevated temperatures.

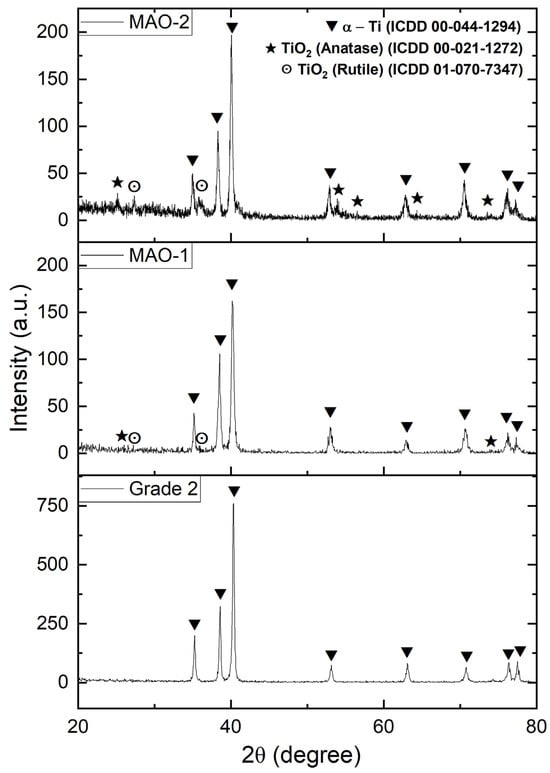

Figure 5 shows the X-ray diffraction patterns of the untreated Grade 2 titanium and the MAO coatings obtained under MAO-1 (300 V) and MAO-2 (350 V) processing conditions. The diffraction pattern of the initial material (Grade 2) contains only peaks corresponding to the hexagonal α-phase of titanium (ICDD 00-044-1294), indicating the absence of any oxide or intermetallic phases on the surface prior to treatment. After MAO processing in the composite Na3PO4–Na2SiO3–NaOH electrolyte at applied voltages of 300 and 350 V (regimes MAO-1 and MAO-2, respectively), additional reflections appear on the diffractograms corresponding to TiO2 phases—anatase (ICDD 00-021-1272, marked with ★) and rutile (ICDD 01-070-7347, marked with ⊙). At the same time, the intensity of the α-Ti peaks decreases noticeably compared with the untreated sample, indicating the formation of a surface oxide layer and partial attenuation of the diffraction signal from the metallic substrate.

Figure 5.

X-ray diffraction patterns of the untreated Grade 2 titanium and the MAO coatings obtained under MAO-1 (300 V) and MAO-2 (350 V) processing conditions.

A comparison of the MAO-1 and MAO-2 diffraction patterns shows that increasing the applied voltage from 300 to 350 V leads to an increase in the intensity of TiO2 reflections, particularly those associated with rutile, while the contribution of the anatase phase remains evident but relatively diminished. This is consistent with the fact that higher voltages enhance the energy of micro-arc discharges and increase the local temperature within the coating, thereby promoting the thermodynamically driven transformation of metastable anatase into the more stable rutile phase.

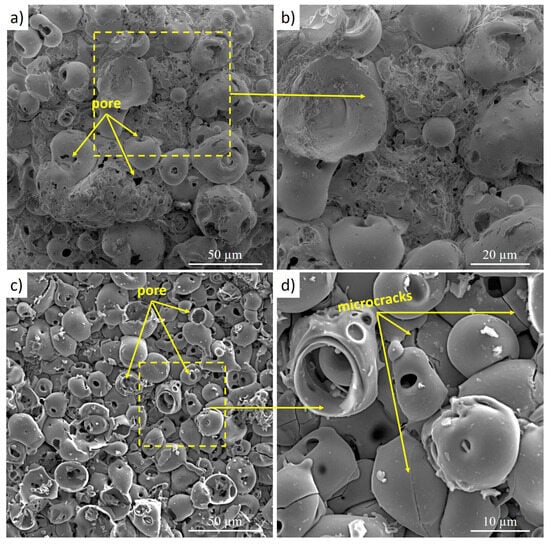

SEM images of the surface morphology of the coatings formed by micro-arc oxidation at different applied voltages are shown in Figure 6. For both MAO regimes, a typical crater-like porous structure is observed, consisting of numerous pores ranging from 1 to 9 µm, nanodefects, and a network of microcracks. The formation of these morphological features is associated with the dynamics of micro-arc discharges: micropores originate from gas bubble ejection and the redistribution of molten oxide from discharge channels, whereas microcracks form as a result of high thermomechanical stresses generated during the rapid cooling and solidification of the oxide melt in the cold electrolyte [28]. A comparison of the MAO-1 (300 V) and MAO-2 (350 V) samples clearly shows the influence of the applied voltage on coating morphology. At the higher voltage (MAO-2), the discharge energy increases, leading to elevated local temperatures and a higher density of plasma micro-explosions. As a result, the surface of the MAO-2 coating contains larger craters, a greater number of discharge openings, and more pronounced ruptured pore walls, indicating partial breakdown and remelting of the oxide layer. The increased pore diameter and enlarged microcrack patterns are consistent with intensified discharge channel activity under stronger electric fields. When the local field strength exceeds the dielectric breakdown threshold, dielectric failure of the oxide occurs, producing large openings and rougher porosity. This leads to reduced coating density and uniformity, which may negatively affect wear resistance. At the moderate voltage of 300 V (MAO-1), the coating surface is denser, contains fewer defects, and exhibits smaller and more uniformly distributed craters. Thus, increasing the applied voltage from 300 to 350 V results in more intense discharge erosion, enhanced melting, and partial destruction of the oxide layer, manifested in the enlargement of craters and the development of microcracks, whereas the MAO-1 coating demonstrates a more compact and structurally stable surface.

Figure 6.

Surface morphology of the micro-arc oxide coatings: (a,b) MAO-1; (c,d) MAO-2.

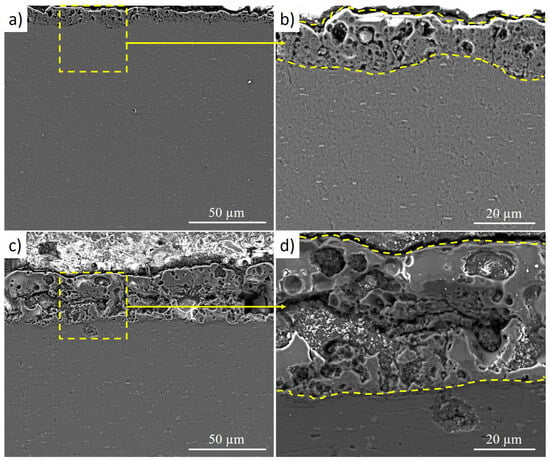

Figure 7 shows cross-sectional SEM images of the micro-arc oxidation coatings formed under two processing regimes: MAO-1 (Figure 7a,b) and MAO-2 (Figure 7c,d). In both cases, a continuous oxide layer is formed on the Grade 2 titanium substrate, indicating stable MAO processing without coating delamination. The MAO-1 coating (Figure 7a,b) exhibits a relatively uniform thickness and a typical MAO morphology consisting of an outer porous layer and a denser inner layer adjacent to the titanium substrate. The pores are predominantly fine and evenly distributed, while the coating–substrate interface is well defined and free of large interfacial cracks. Such a structure is characteristic of MAO coatings produced at moderate voltages and contributes to good mechanical integrity and wear resistance. In contrast, the MAO-2 coating (Figure 7c,d), formed at a higher applied voltage, shows a noticeably thicker oxide layer with a more developed porous structure. The outer region contains larger pores and locally interconnected cavities, which are indicative of more intense micro-arc discharges during processing. In addition, microcracks and local structural heterogeneities are observed within the coating, particularly in the outer porous layer. These features are attributed to the increased discharge energy and higher local thermal stresses associated with the elevated voltage.

Figure 7.

Cross-sectional SEM images of micro-arc oxidation coatings: (a,b) MAO-1; (c,d) MAO-2.

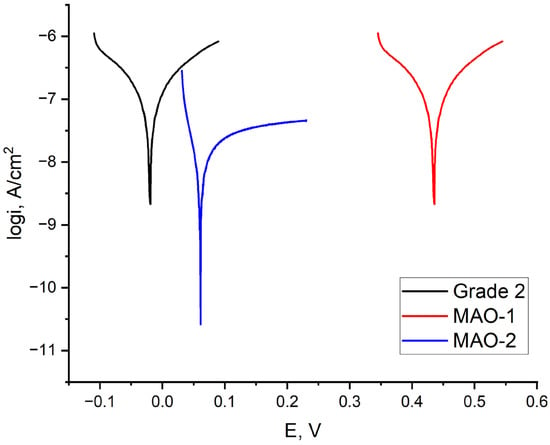

The corrosion resistance of the MAO-treated samples was evaluated primarily based on the corrosion current density (icorr). Compared with bare Grade 2 titanium, both MAO coatings exhibit a significant reduction in icorr, indicating improved corrosion resistance in a 3.5 wt.% NaCl solution [38]. The corrosion rate (CR), which is directly derived from the corrosion current density, follows the same trend and therefore provides no additional independent information (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Potentiodynamic polarization curves of untreated titanium Grade 2 and MAO-coated samples (MAO-1 and MAO-2) in 3.5% NaCl solution.

No significant difference in icorr was observed between the MAO-1 and MAO-2 coatings within the experimental uncertainty. Although the MAO-2 coating exhibits larger pores and a higher density of microcracks in the SEM images, these morphological features did not result in a measurable deterioration of corrosion resistance under the present testing conditions (Table 3).

Table 3.

Electrochemical corrosion parameters of Grade 2 titanium and MAO coatings in 3.5% NaCl solution.

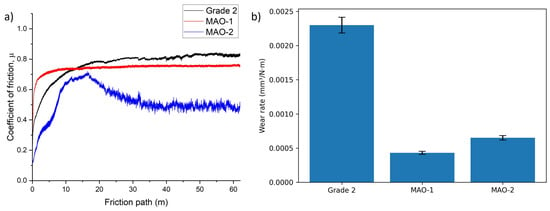

Tribological tests (Figure 9) demonstrate that micro-arc oxidation has a pronounced positive effect on the frictional behavior and wear resistance of Grade 2 titanium. The untreated titanium surface, ground to 2000 grit, exhibits the highest coefficient of friction (≈0.85) and the maximum wear rate of 2.3 × 10−3 mm3/(N·m), which can be attributed to the absence of a protective oxide layer and the relatively low hardness of α-Ti [39]. Both MAO coatings show a significant reduction in friction and a substantial decrease in wear. For the MAO-1 coating, the coefficient of friction stabilizes at approximately 0.74, while the wear rate decreases nearly fivefold to 4.35 × 10−4 mm3/(N·m). This improvement is primarily associated with the formation of a hard TiO2-based ceramic layer, which effectively protects the substrate from direct contact during sliding.

Figure 9.

(a) Friction coefficient curves for Grade 2, MAO-1, and MAO-2 samples and (b) wear rates of the tested samples.

Compared with the polished titanium substrate, the MAO-treated surfaces are characterized by increased roughness due to their porous and uneven morphology. Such surface features may influence the frictional response, particularly during the initial stages of sliding, by affecting the real contact area and local stress distribution. Nevertheless, the dominant factor governing the enhanced wear resistance is the presence of the hard ceramic oxide layer.

The MAO-2 coating exhibits a further reduction in the coefficient of friction to approximately 0.58, which correlates with its more developed porous structure observed in SEM images. The modified surface topography can alter contact mechanics and tribochemical interactions at the sliding interface, contributing to reduced friction. However, the wear rate of MAO-2 is slightly higher than that of MAO-1 (6.50 × 10−4 mm3/(N·m)), which is attributed to the presence of larger pores and microcracks formed at the higher MAO voltage. These defects act as stress concentrators and facilitate localized material removal during sliding.

Overall, despite the increased surface roughness of the MAO coatings compared with the polished titanium substrate, the formation of TiO2-based ceramic layers leads to a significant improvement in wear resistance. The friction behavior is governed by the combined effects of surface morphology, contact mechanics, and the mechanical integrity of the oxide layer rather than by any lubrication mechanism associated with porosity.

4. Conclusions

Micro-arc oxidation (MAO) coatings were successfully produced on Grade 2 titanium in a composite Na3PO4–Na2SiO3 electrolyte at applied voltages of 300 and 350 V, and their structural, corrosion, and tribological properties were systematically investigated. X-ray diffraction analysis confirmed the formation of an oxide layer after MAO treatment; however, well-defined crystalline TiO2 phases were clearly evidenced only for the coating produced at 350 V. For the MAO-1 coating (300 V), TiO2-related reflections were weak and close to the background level, indicating a low degree of crystallinity and/or a thin oxide layer. SEM observations showed that the MAO-1 coating exhibited a denser and more uniform surface morphology with relatively smaller pores, whereas the MAO-2 coating was characterized by larger pores and local defects associated with more intense dielectric breakdown at higher voltage. Electrochemical measurements in a 3.5 wt.% NaCl solution demonstrated that both MAO coatings significantly improve the corrosion resistance of titanium compared with the untreated substrate, with no pronounced difference in corrosion current density between MAO-1 and MAO-2 within experimental uncertainty. Tribological tests revealed that MAO treatment leads to a substantial reduction in friction and wear. The MAO-1 coating showed a greater reduction in wear rate, which is attributed to its denser oxide structure, while the MAO-2 coating exhibited a lower coefficient of friction, likely related to its more developed porous morphology and the associated retention of liquid media during sliding contact. At the same time, the increased porosity and presence of microcracks in MAO-2 resulted in a slightly higher wear rate compared with MAO-1. Overall, the results indicate that variations in the applied MAO voltage lead to distinct trade-offs between surface morphology, friction behavior, and wear resistance. The presented findings provide a comparative assessment of MAO coatings formed under different electrical conditions rather than defining a single optimal processing regime.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.S. and D.B. (Daryn Baizhan); methodology, B.A. and L.S.; investigation, D.B. (Dastan Buitkenov) and N.B.; writing—original draft preparation, D.B. (Dastan Buitkenov) and N.B.; visualization, B.A. and G.T.; writing—review and editing, N.B. and L.S.; supervision, D.B. (Daryn Baizhan). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Science Committee of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Republic of Kazakhstan (Grant No. BR24992879).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Wang, S.; Yu, T.; Pang, Z.; Liu, X.; Shi, C.; Du, N. Improving the Fatigue Resistance of Plasma Electrolytic Oxidation Coated Titanium Alloy by Ultrasonic Surface Rolling Pretreatment. Int. J. Fatigue 2024, 181, 108157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Feng, S.; Li, Z.; Chen, Z.; Zhao, T. Microstructure and Properties of Micro-Arc Oxidation Ceramic Films on AerMet100 Steel. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2020, 9, 6014–6027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhassulan, A.; Rakhadilov, B.; Baizhan, D.; Kengesbekov, A.; Kakimzhanov, D.; Musataeva, N. Influence of TiO2 Nanoparticle Concentration on Micro-Arc Oxidized Calcium–Phosphate Coatings: Corrosion Resistance and Biological Response. Coatings 2025, 15, 1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Shao, Z.; Jing, B. Effect of Electrolyte Composition on Photocatalytic Activity and Corrosion Resistance of Micro-Arc Oxidation Coating on Pure Titanium. Procedia Earth Planet. Sci. 2011, 2, 156–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, I.S.V.; Alfaro, M.F.; da Cruz, N.C.; Mesquita, M.F.; Takoudis, C.; Sukotjo, C.; Mathew, M.T.; Barão, V.A.R. Tribocorrosion Behavior of Biofunctional Titanium Oxide Films Produced by Micro-Arc Oxidation: Synergism and Mechanisms. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2016, 60, 8–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Z.Q.; Ivanisenko, Y.; Diemant, T.; Caron, A.; Chuvilin, A.; Jiang, J.Z.; Valiev, R.Z.; Qi, M.; Fecht, H.-J. Synthesis and Properties of Hydroxyapatite-Containing Porous Titania Coating on Ultrafine-Grained Titanium by Micro-Arc Oxidation. Acta Biomater. 2010, 6, 2816–2825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakhadilov, B.; Zhassulan, A.; Ormanbekov, K.; Shynarbek, A.; Baizhan, D.; Aldabergenova, T. Surface Modification and Tribological Performance of Calcium Phosphate Coatings with TiO2 Nanoparticles on VT1-0 Titanium by Micro-Arc Oxidation. Crystals 2024, 14, 945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, D.H.; Kim, I.; Kim, J.; Kim, Y.S.; Semiatin, S.L. Microstructure Development during Equal-Channel Angular Pressing of Titanium. Acta Mater. 2003, 51, 983–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sergueeva, A.V.; Stolyarov, V.V.; Valiev, R.Z.; Mukherjee, A.K. Superplastic Behaviour of Ultrafine-Grained Ti–6Al–4V Alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2002, 323, 318–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komarova, E.G.; Sharkeev, Y.P.; Sedelnikova, M.B.; Prosolov, K.A.; Khlusov, I.A.; Prymak, O.; Epple, M. Zn- or Cu-Containing CaP-Based Coatings Formed by Micro-arc Oxidation on Titanium and Ti-40Nb Alloy: Part I—Microstructure, Composition and Properties. Materials 2020, 13, 4116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharkeev, Y.; Komarova, E.; Sedelnikova, M.; Sun, Z.; Zhu, Q.; Zhang, J.; Tolkacheva, T.; Uvarkin, P. Structure and Properties of Micro-Arc Calcium Phosphate Coatings on Pure Titanium and Ti–40Nb Alloy. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2017, 27, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakhadilov, B.; Baizhan, D. Creation of Bioceramic Coatings on the Surface of Ti–6Al–4V Alloy by Plasma Electrolytic Oxidation Followed by Gas Detonation Spraying. Coatings 2021, 11, 1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.M.; Jiang, B.L.; Lei, T.Q.; Guo, L.X. Microarc Oxidation Coatings Formed on Ti6Al4V in Na2SiO3 System Solution: Microstructure, Mechanical and Tribological Properties. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2006, 201, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ming, X.; Ma, X.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, P.; Li, Q.; Wu, Y.; Li, Y. Microstructures and Mechanical Properties of Porous Coating Prepared by Micro-Arc Oxidation on Low-Elastic-Modulus Ti-19Zr-10Nb-1Fe Alloy. Ceram. Int. 2025, 51, 56486–56497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raizer, Y.P. Physics of Gas Discharge; Nauka: Moscow, Russia, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Hu, H.; Du, S.; Cheng, B.; Pan, Y.; Lu, H. Influence of the Dual-Current Method on the Properties and Growth Mechanisms of Micro-Arc Oxidation Coatings. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2024, 328, 130031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Fang, Y.-J.; Zheng, H.; Tan, G.; Cheng, H.; Ning, C. Effect of Applied Voltage on Phase Components of Composite Coatings Prepared by Micro-Arc Oxidation. Thin Solid Film. 2013, 544, 79–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moskalewicz, T.; Kruk, A.; Kot, M.; Kayali, S.; Czyrska-Filemonowicz, A. Characterization of Microporous Oxide Layer Synthesized on Ti–6Al–7Nb Alloy by Micro-Arc Oxidation. Arch. Civ. Mech. Eng. 2014, 14, 370–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedelnikova, M.B.; Ugodchikova, A.V.; Tolkacheva, T.V.; Chebodaeva, V.V.; Cluklhov, I.A.; Khimich, M.A.; Bakina, O.V.; Lerner, M.I.; Egorkin, V.S.; Schmidt, J.; et al. Surface Modification of Mg0.8Ca Alloy via Wollastonite Micro-Arc Coatings: Significant Improvement in Corrosion Resistance. Metals 2021, 11, 754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fattah-alhosseini, A.; Molaei, M.; Babaei, K. The Effects of Nano- and Micro-Particles on Properties of Plasma Electrolytic Oxidation (PEO) Coatings Applied on Titanium Substrates: A Review. Surf. Interfaces 2020, 21, 100659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ari, J.; Louvet, G.; Ledemi, Y.; Célarié, F.; Morais, S.; Bureau, B. Anodic bonding of mid-infrared transparent germanate glasses for high pressure–high temperature microfluidic applications. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 2020, 21, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lokeshkumar, E.; Premchand, C.; Manojkumar, P.; Shishir, R.; Rama Krishna, L.; Prashanth, K.G.; Rameshbabu, N. Effect of Electrolyte Composition on the Surface Characteristics of Plasma Electrolytic Oxidation Coatings over Ti–40Nb Alloy. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2023, 465, 129591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Qu, Y.; Yang, X.; Liao, B.; Xue, W.; Cheng, W. Characterization and First-Principles Calculations of WO3/TiO2 Composite Films on Titanium Prepared by Microarc Oxidation. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2017, 201, 311–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, E.; de Souza, G.B.; Serbena, F.C.; Santos, H.L.; de Lima, G.G.; Szesz, E.M.; Lepienski, C.M.; Kuromoto, N.K. Effect of Anodizing Time on the Mechanical Properties of Porous Titania Coatings Formed by Micro-Arc Oxidation. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2017, 309, 203–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roknian, M.; Fattah-alhosseini, A.; Gashti, S.O. Plasma Electrolytic Oxidation Coatings on Pure Ti Substrate: Effects of Na3PO4 Concentration on Morphology and Corrosion Behavior of Coatings in Ringer’s Physiological Solution. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2018, 27, 1343–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vakili-Azghandi, M.; Fattah-alhosseini, A.; Keshavarz, M.K. Optimizing the Electrolyte Chemistry Parameters of PEO Coating on 6061 Al Alloy by Corrosion Rate Measurement: Response Surface Methodology. Measurement 2018, 124, 252–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fattah-Alhosseini, A.; Vakili-Azghandi, M.; Keshavarz, M.K. Influence of Concentrations of KOH and Na2SiO3 Electrolytes on the Electrochemical Behavior of Ceramic Coatings on 6061 Al Alloy Processed by Plasma Electrolytic Oxidation. Acta Metall. Sin. (Engl. Lett.) 2016, 29, 274–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molaei, M.; Fattah-Alhosseini, A.; Gashti, S.O. Sodium Aluminate Concentration Effects on Microstructure and Corrosion Behavior of the Plasma Electrolytic Oxidation Coatings on Pure Titanium. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 2018, 49, 368–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durdu, S.; Aktuǧ, S.L.; Korkmaz, K. Characterization and Mechanical Properties of the Duplex Coatings Produced on Steel by Electro-Spark Deposition and Micro-Arc Oxidation. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2013, 236, 303–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanmohammadi, H.; Allahkaram, S.R.; Igual Munoz, A.; Towhidi, N. The Influence of Current Density and Frequency on the Microstructure and Corrosion Behavior of Plasma Electrolytic Oxidation Coatings on Ti6Al4V. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2017, 26, 931–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Shen, X. Fabrication of SiO2 Nanoparticles Incorporated Coating onto Titanium Substrates by the Micro Arc Oxidation to Improve the Wear Resistance. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2019, 364, 180–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.M.; Lee, S.H.; Jung, D.-H. Surface oxidation of petroleum pitch to improve mesopore ratio and specific surface area of activated carbon. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM G5-14(2021); Standard Reference Test Method for Making Potentiodynamic Anodic Polarization Measurements. ASTM: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2021.

- ASTM G99-17; Standard Test Method for Wear Testing with a Pin-on-Disk Apparatus. ASTM: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2023.

- ISO 4287:1997; Geometrical Product Specifications (GPS)—Surface texture: Profile method—Terms, definitions and surface texture parameters. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 1997.

- Sagdoldina, Z.; Zhurerova, L.; Tyurin, Y.; Baizhan, D.; Kuykabayeba, A.; Abildinova, S.; Kozhanova, R. Modification of the Surface of 40 Kh Steel by Electrolytic Plasma Hardening. Metals 2022, 12, 2071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, B.J.Y.; Yang, W.; Xu, D.; Chen, J. Microstructure and Properties of Graphene Oxide-Doped TiO2 Coating on Titanium by Micro Arc Oxidation. J. Wuhan Univ. Technol. Sci. Ed. 2018, 33, 1524–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantay, N.; Kasmamytov, N.; Rakhadilov, B.; Plotnikov, S.; Paszkowski, M.; Kurbanbekov, S. Influence of Temperature on Structural-Phase Changes and Physical Properties of Ceramics on the Basis of Aluminum Oxide and Silicon. Mater. Test. 2020, 62, 716–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenzhaliyev, B.; Kenzhegulov, A.; Mamaeva, A.; Panichkin, A.; Kshibekova, B.; Alibekov, Z.; Fischer, D. Tribological Characteristics of Multilayer TiN/TiCN Coatings Compared to TiN Coatings. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2025, 34, 25810–25819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.