Abstract

Magnesium alloys are promising biodegradable orthopedic implant materials, but their clinical translation is hindered by rapid, unregulated corrosion in physiological environments. Polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) coating has attracted substantial attention for addressing the issue above. However, it suffers from insufficient interfacial adhesion to Mg alloy substrates. In this work, we propose a Zr-based pretreatment strategy to enhance PVDF coatings. The pretreatment was performed via a chemical conversion deposition method, which fabricated a Zr-based film on AZ31 magnesium alloy and greatly promoted the adhesion of the following PVDF coating. Interface analysis showed that coating adhesion was improved from 0.44 MPa to 2.48 MPa. In light of this, corrosion protection performance was significantly improved. Electrochemical tests in simulated body fluid revealed the enhanced PVDF coating shifted the corrosion potential from −1.594 V to −1.392 V and reduced the corrosion current density by over five orders of magnitude. Immersion tests also showed stable pH level, low weight loss, and good hydrophobicity with the enhanced PVDF coating. In summary, the enhanced PVDF coating provides excellent corrosion protection for magnesium alloys, thus boosting their biomedical use.

1. Introduction

Biodegradable orthopedic implants, such as bone screws and fracture fixation plates, have attracted extensive research attention. Compared with traditional metallic materials such as Ti alloys and stainless steel, magnesium alloys stand out as promising orthopedic implants for their distinct advantages: biodegradability obviating the need for secondary removal surgery, mechanical compatibility with human bone in terms of elastic modulus, and good osseointegration [1,2,3].

However, rapid and uncontrollable corrosion of magnesium alloys in physiological environments remains a major bottleneck in their clinical translation for orthopedic use. Magnesium alloys undergo rapid degradation via electrochemical reactions, indicated by Equations (1) and (2), in Cl−-rich environments, such as body fluid and blood plasma. As reported in earlier studies, this degradation produces OH− ions (triggering local alkalization) and accumulates hydrogen gas, which not only damages surrounding tissues like osteoblasts but also perturbs the balance of pH-sensitive physiological reactions, delaying bone healing [4]. Therefore, it is imperative to achieve a controllable degradation behavior for magnesium alloys.

Mg + H2O → Mg(OH)2 + H2↑

Mg(OH)2 + Cl− → MgCl2 + OH−

Protective polymer coatings have emerged as a widely adopted, effective approach to alleviate the rapid degradation of magnesium alloys in corrosive environments [5,6]. Among various polymer materials, polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) has attracted substantial attention since the late 20th century, owing to its exceptional properties, including superior thermal and chemical stability, low friction, strong abrasion resistance, hydrophobicity [7], and piezoelectric effect [8,9,10,11]. Early research has laid a foundation for PVDF’s application in coating technologies. For instance, Munekata [12] systematically summarized the performance advantages and industrial application prospects of PVDF as coating materials, while Deflorian et al. [13] investigated the corrosion protection mechanisms of PVDF coatings on steel substrates. Later, Conceicao et al. [14,15] applied PVDF coating to magnesium alloys and opened new opportunities for PVDF-based surface modification of magnesium alloys.

However, a key challenge of PVDF coating for magnesium alloys lies in the spontaneous formation of a porous magnesium oxide layer upon the alloys’ exposure to air [16]. This native oxide layer undermines the protective efficacy of coatings in that it weakens the coatings’ adhesion to the alloy, leading to delamination and compromised long-term corrosion resistance [17]. A surface pretreatment of Mg alloys before polymer coating is an effective way to enhance interfacial adhesion. A variety of surface pretreatment methods are available for this purpose, including micro-arc oxidation (MAO) [18,19], silane coupling agent modification [20,21], and chemical conversion coating (CCC) [22,23]. Among these technologies, CCC is a relatively more effective and cheaper method widely used in industrial applications [23].

Phosphate-based pretreatment is one of the most commonly studied CCC methods for enhancing coating performance across different substrates [24,25,26,27]. Ramezanzadeh et al. [24] utilized a modified phosphate layer to enhance the anticorrosion performance and adhesion of the subsequent epoxy coating on steel. Zhou et al. [25] found that phosphate pretreatment on carbon steel improved the corrosion resistance of Sol–Gel silica coatings in NaCl solution. Li et al. [26] used dicalcium phosphate dihydrate (DCPD) as a pretreatment for AZ31 Mg alloy, followed by a biodegradable poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) coating. The morphology of the DCPD layer regulated the corrosion resistance of PLGA coating, achieving controlled degradation. Yang et al. [27] prepared phosphate conversion films on Mg alloy, finding that the phosphate layer improved interfacial bonding between substrate and electrophoretic coating and enhanced corrosion resistance as a physical barrier against corrosive media. All the above works verified the effectiveness of phosphate conversion in optimizing inorganic-organic composite coating systems. However, phosphate-based pretreatment suffers from notable limitations that restrict its practical application: the inherently porous and microcrack-prone structure of phosphate films allows for corrosive media penetration and the generation of phosphate-containing wastewater poses significant eutrophication risks to the environment.

MgF2-based conversion coatings are another widely investigated CCC methods for enhancing the interfacial adhesion between Mg alloys and polymer coatings [14,15,28,29]. It can form a relatively homogeneous MgF2 layer on the Mg alloy surface to protect the substrate. Conceição et al. [14,15] prepared an MgF2 conversion layer on AZ31 Mg alloy via hydrofluoric acid treatment, showing that the homogeneous MgF2 film considerably improved the adhesion strength of the subsequent PVDF coating by 52% compared with an untreated alloy. Liu et al. [29] applied an MgF2 pretreatment on Mg-Zn-Ca alloy before depositing a poly (lactic acid) (PLA) coating. The MgF2 layer enhanced the interfacial compatibility between PLA and the substrate and prolonged the corrosion protection lifespan of coating in vitro immersion. Even though, MgF2-based conversion coatings involve a preparation process using concentrated hydrofluoric acid, which is highly toxic. Therefore, their large-scale application is hindered.

Zr-based pretreatment has recently emerged as a promising alternative for enhancing metal-polymer coating adhesion [30,31,32], addressing the key drawbacks of phosphate-based or MgF2-based coatings while offering unique advantages. Zr-based layers form compacts, uniform amorphous zirconium oxide structures that inherently resist corrosive media penetration without additional sealing. Moreover, Zr-based pretreatments avoid the environmental or health concerns associated with phosphate wastewater or HF acid. Its efficacy has been widely validated across diverse metal substrates. Sababi et al. [30] showed that the Zr-based layer effectively boosts both dry and wet adhesion of fusion-bonded epoxy coatings on carbon steel. Ahmadi et al. [31] applied a modified Zr-based pretreatment on aluminum alloys prior to epoxy coating. The formed amorphous zirconium oxide layer not only achieves uniform coverage but also forms stable Zr-O-Al chemical bonds with the substrate and covalent linkages with epoxy. This synergy significantly enhances the Al alloy-epoxy interfacial adhesion and improves the substrate’s corrosion resistance. Jawad et al. [32] fabricated Zr-based layer on Zn-Al-Mg coated steel, and the Zr-based layer significantly improves the adhesion between Zn-Al-Mg coated steel and subsequent epoxy coatings, attributed to improved mechanical interlocking and chemical bonding. In biomedical scenarios, Zr-based pretreatment offers additional benefits. It exhibits excellent abrasion and corrosion resistance, remarkable mechanical properties, favorable biocompatibility, high osseointegration, and low toxicity [33,34]. These characteristics align well with the performance requirements for Mg alloy surface modification, making Zr-based pretreatment a highly suitable candidate for improving polymer coating adhesion and corrosion protection on Mg alloys.

While PVDF coating and Zr-based pretreatment have, respectively, received increasing attention in biomedical research, systematic studies exploring their synergistic combination to simultaneously enhance the interfacial adhesion and long-term corrosion resistance of Mg alloys remain scarce. To fill this research gap, a novel surface modification strategy was proposed in this study. A homogeneous PVDF layer was successfully deposited on Zr-pretreated AZ31 magnesium alloys via a dip coating method. Comprehensive characterizations were conducted to verify the protective performance of the composite system, and the underlying mechanism of the synergistic enhancement was also elucidated. The findings of this work offer valuable insights for developing advanced surface modification strategies for Mg alloys intended for biomedical applications.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

AZ31 magnesium alloy plates (50 mm × 25 mm × 5 mm) and rods (diameter 3 mm, length: 40 mm) were employed as substrates. The composition of the AZ31 alloy is presented in Table 1. PVDF was procured from Shanghai Adamas Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China) and used without further purification. All other reagents, such as N, N-Dimethylformamide (DMF), ethanol, and hexafluoro zirconic acid, were of analytical-purity grade and sourced from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China).

Table 1.

Composition of AZ31 Mg alloy (wt. %, bal. Mg).

2.2. Coating Preparation

Prior to surface film construction, all magnesium alloy samples were successively polished using 400, 800, 1000, and 1500-grit SiC papers. Subsequently, the samples were ultrasonically cleaned three times in ethanol and then air-dried.

Following the protocol described in a previous study [35], a standard Zr-based chemical conversion pretreatment film was prepared. The chemical bath is a dilute H2ZrF6-based solution, containing free fluoride and zirconium ions. The bath pH value was adjusted to 4.3 ± 0.1 using dilute HNO3 and NH4HCO3, while the free fluoride concentration was tuned to 50 ± 10 ppm via a dilute KF solution. The AZ31 magnesium alloy samples were soaked in this prepared bath for 5 min, allowing for the formation of a uniform Zr-based film. Afterward, all samples were washed three times with ethanol and subsequently dried in an oven at 100 °C for 15 min.

A PVDF solution was prepared in DMF at a concentration of 10 wt%. A PVDF coating was formed by immersing the Zr-treated substrate in the PVDF solution for 20 s. Subsequently, the substrate was withdrawn by a dip coater at a speed of 20 mm/min. The PVDF coating was air-dried for 10 min and then baked in an oven at 100 °C for 10 min. This process was followed by a second dipping.

2.3. Characterization

The crystal structure of the PVDF film was characterized using an X-ray diffractometer (XRD, Rigaku SmartLab SE, Rigaku Corporation, Akishima, Tokyo, Japan) with Cu-Kα incident radiation (λ = 1.5406 Å). The measurements were carried out at room temperature, with the 2θ range spanning from 10° to 80°.

The surface chemical composition was analyzed via X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS, Axis Supra, Kratos, Manchester, UK) and Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR, Vertex 70, Bruker, Billerica, MA, USA). The surface and cross-section morphologies were observed through a scanning electron microscope (SEM, SU8000, Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan). The hydrophilicity of the samples was investigated by measuring the water contact angle (WCA) with a Contact Angle Analyzer (DSA25, Kruss, Hamburg, Germany). Three parallel measurements were performed on different areas of each sample, and three replicate samples were tested per group to obtain statistically reliable results.

The adhesion of the coating to the substrate was evaluated through a mechanical pull-off test. This test was conducted on a PosiTest Pull-Off Adhesion Tester (DeFelsko, Ogdensburg, NY, USA) with a resolution of 0.01 MPa, in compliance with ASTM D 4541 and ISO 4624 standards. Three replicate samples were prepared for each group.

The corrosion protection performance of the coatings was assessed by electrochemical measurements and immersion test, both were conducted in SBF. SBF was prepared according to Kokubo’s formula, with the following composition (g/L): NaCl (8.035), NaHCO3 (0.355), KCl (0.225), Na2HPO4·3H2O (0.231), MgCl2·6H2O (0.311), CaCl2 (0.292), Na2SO4 (0.072), and Tris buffer (6.118). The pH value was adjusted to 7.4 ± 0.1 using 1 M HCl, and the solution was filtered through a 0.22 μm membrane before use. All tests using SBF were conducted at 37 ± 1 °C to simulate human body temperature.

Electrochemical measurements, which included polarization curves and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS), were performed using an electrochemical analyzer (CHI660E, Chenhua, Shanghai, China). A standard three-electrode cell of volume 100 mL was employed for these electrochemical measurements. The counter electrode was graphite, the reference electrode was an Ag/AgCl electrode (calibrated with saturated KCl solution), and the working electrode was the sample under test. Samples for electrochemical tests were cold-mounted with epoxy resin, and the exposed area was 1 cm2. Potentiodynamic polarization experiments were performed at a scan rate of 1 mV s−1, with a potential range of −2.0 V to −0.8 V. This potential window was selected based on the open-circuit potential (OCP) of the Mg alloy systems (typically around −1.5 V in SBF), ensuring complete coverage of the anodic dissolution and cathodic hydrogen evolution reactions. The polarization curves were fitted via the built-in software of the CHI660E electrochemical workstation using the Tafel extrapolation method. Furthermore, EIS was measured over a frequency range from 10−2 Hz to 105 Hz. For immersion tests, the alloys were put into SBF solution with an initial sample surface area to solution volume ratio of 0.2 cm2/mL. The SBF solution was replaced every 24 h to simulate the metabolic process of body fluids. Temporal changes in the solution pH value, sample weight, and coating surface morphology were monitored. Three replicate samples were prepared for each group.

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Characterizations of As-Prepared Coatings

PVDF is a semi-crystalline polymer with five crystalline phases (α, β, γ, δ, ε). The α-phase is the most common crystalline form of PVDF, typically obtained via direct crystallization from the melt under conventional conditions. The β-phase is the most crucial functional crystalline form of PVDF, featuring an all-trans (TTTT) planar zigzag conformation. This specific conformation enables the dipole moments of all -CF2- and -CH2- groups to align in the same direction, generating a significant molecular dipole moment and spontaneous polarization. With an orthorhombic crystal structure, the β-phase exhibits excellent piezoelectric, ferroelectric, and hydrophobicity properties critical for biomedical applications.

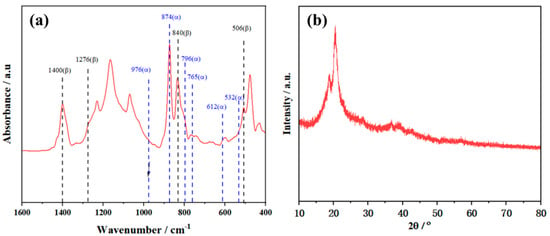

Figure 1a presents the FTIR spectroscopy pattern of the PVDF coating. In this spectrum, four distinct absorption bands are observed at 506, 840, 1276, and 1400 cm−1, all of which are associated with the polar β phase [36]. Specifically, the peak at 1400 cm−1 is assigned to the wagging vibration of CH groups; the peak at 506 cm−1 corresponds to the bending vibration of CF bonds; the peak at 839 cm−1 corresponds to three types of vibrations, namely CH rocking, CF stretching, and skeletal C-C stretching; and the peak at 1280 cm−1 corresponds to the symmetric stretching vibration of CF bonds [37,38]. Notably, the peaks characteristic of the non-polar α phase at 532 cm−1 and 976 cm−1 [39] are not detected in this film. However, peaks at 612 cm−1, 765 cm−1, 796 cm−1, and 874 cm−1 [39] are still distinguishable, which confirms that the non-polar α phase is present in the film.

Figure 1.

(a) FTIR, (b) XRD spectra of the as-prepared PVDF film.

The structural properties of the PVDF film were also analyzed by XRD, as shown in Figure 1b, where the diffraction peak at 2θ = 20.5° corresponds to the (110) and (200) crystal planes of the β-phase. The diffraction peak at 2θ = 18.4° is identified as the α crystal phase of PVDF [40]. Combining the characterization results of FTIR and XRD, it can be confirmed that the crystalline phases of the PVDF film include both α-phase and β-phase.

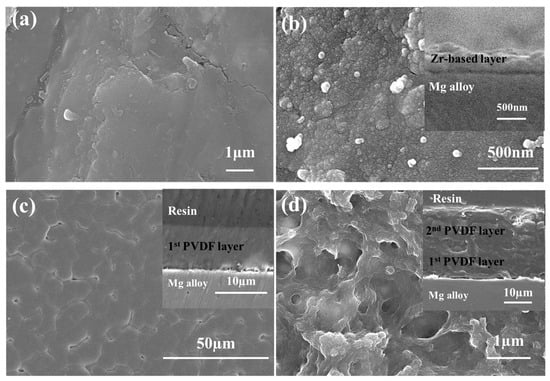

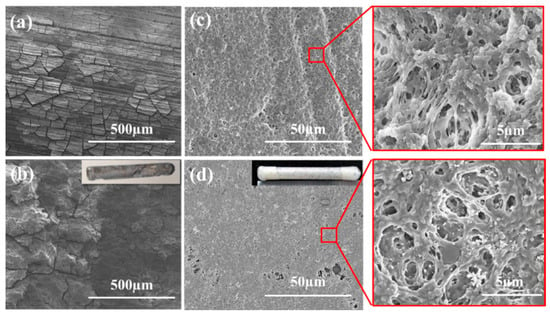

The morphology of each coating layer, including surface and cross-sectional structures, is presented in Figure 2. For the untreated Mg alloy (Figure 2a), its surface exhibits a smooth appearance with no obvious irregularities, consistent with the machining state of the substrate. After the Zr-based pretreatment process (Figure 2b), the alloy surface is covered with grains of less than 100 nm in size, forming a uniformly distributed microstructural morphology. This pretreatment, therefore, noticeably increases the roughness of the alloy surface. The cross-sectional view of the Zr-treated sample (inset of Figure 2b) further reveals that the Zr-based layer forms a continuous, thin film with a uniform thickness of 200–300 nm.

Figure 2.

Surface SEM images of AZ31 Mg alloy under different treatment conditions (insets: cross-section of each sample) (a) after cleaning, (b) Zr-treated, (c) 1st PVDF coating, (d) 2nd PVDF coating.

For the sample with the 1st PVDF coating (Figure 2c), the surface is uniform and smooth, yet features some small pinholes. These pinholes have a diameter range of 2–5 μm and are specifically localized at the grain boundaries of the semi-crystalline PVDF polymer, with their formation primarily tied to PVDF’s crystallization behavior during the dip-coating process. As the solvent evaporates, PVDF chains aggregate and crystallize into grain structures. The inherent interfacial gaps between adjacent grains, coupled with slight volume shrinkage during crystallization, collectively induce pinhole formation at the grain boundaries. The cross-sectional image corresponding to this sample (inset of Figure 2c) shows that the single PVDF coating has a thickness of ~10 μm, with a dense structure that fully covers the Zr-pretreated surface.

The sample with the 2nd PVDF coating (Figure 2d) displays a distinct porous structure, where the pores have a diameter range of 0.5–2 μm. As shown in its cross-sectional view (inset of Figure 2d), the double PVDF coating achieves a total thickness of 20–30 μm, with the two coating layers fused into a continuous film. Importantly, the observed pores do not connect to form vertical channels. This configuration ensures the coating maintains structural integrity while providing a moderately porous structure that may facilitate controlled ion transport, which is beneficial for balancing corrosion protection and potential biological compatibility of the implant system.

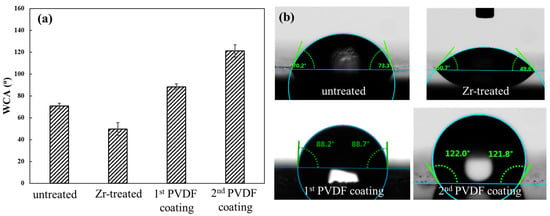

The WCA is a key parameter for evaluating the surface wettability of materials, defined as the angle formed between the tangent of the liquid–vapor interface and the solid–liquid interface when a sessile water droplet is in equilibrium on the solid surface [41,42]. Higher WCA values indicate more hydrophobic surfaces. Since the surface wettability correlates closely with coating corrosion resistance, the WCAs of untreated, Zr-treated, and PVDF-coated substrates were measured to assess the coating’s corrosion-prevention performance, as presented in Figure 3. The WCA of the untreated Mg alloy was measured as 70.7 ± 2.6°, indicating a hydrophilic surface. This hydrophilicity arises from the native oxide layer (composed of MgO and Mg(OH)2) that is inherently rich in surface hydroxyl (-OH) groups.

Figure 3.

The WCA of Mg alloy under different treatment conditions. (a) plot; (b) images.

Compared with the untreated substrate, the WCA of the Zr-treated substrate decreased considerably to 49.7 ± 5.8°, reflecting enhanced hydrophilicity. This reduction in WCA can be attributed to two synergistic factors: first, the Zr-based pretreatment layer formed on the substrate surface substantially increases the total content of surface -OH groups; second, the Zr-based pretreatment also induces a significant increase in surface roughness. This enhanced roughness not only expands the actual surface area of the substrate but also exposes a greater number of -OH groups that are distributed across the rough surface; these two effects collectively further boost the surface hydrophilicity.

When a single PVDF layer was deposited on the Zr-treated surface, the WCA of the resulting coating increased to 88.2 ± 2.7°, shifting toward hydrophobicity. This transition is primarily driven by the intrinsic property of PVDF: its molecular structure contains hydrophobic difluoromethylene (-CF2) groups, which dominate the surface chemical composition and counteract the hydrophilicity of the underlying Zr-treated layer.

Upon applying a second PVDF layer, the WCA of the coating further increased to 121.2 ± 5.6°, signifying a marked enhancement in hydrophobicity. This additional WCA elevation is closely associated with the distinct porous surface morphology of the 2nd PVDF coating, as previously illustrated in Figure 2d. For the double PVDF coating, the porous structure works in tandem with PVDF’s hydrophobicity: the pores trap air to form gas pockets on the coating surface. These gas pockets act as a physical barrier that prevents external water from directly contacting the coating surface, thereby significantly increasing the WCA. Notably, this WCA value is higher than the ~90° reported by Mohamed et al. [41] for PVDF-coated steel and the ~105° reported by Chakradhar et al. [42] for PVDF-coated Al substrate, demonstrating the effectiveness of our double PVDF coating strategy in optimizing surface hydrophobicity.

3.2. Interface Analysis

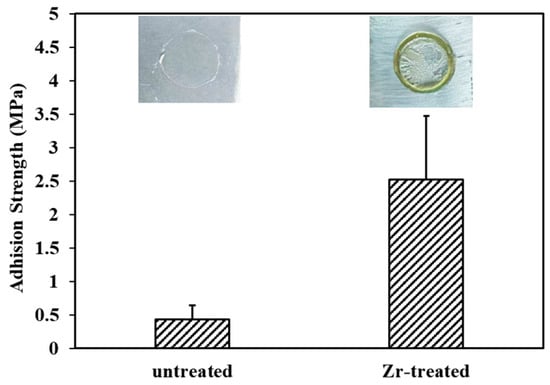

Figure 4 shows the pull-off test results of PVDF coatings applied to Mg alloys with and without Zr-based pretreatment. Clearly, a significant improvement in the adhesion strength of PVDF coatings is achieved in light of the Zr-based pretreatment. Without Zr-based pretreatment, adhesion solely depends on mechanical interlocking. SEM analysis (Figure 2a) reveals that the untreated Mg alloy surface exhibits a relatively smooth morphology. This smooth surface limits the formation of robust mechanical interlocking between the PVDF coating and the Mg substrate, resulting in a low adhesion strength of only ~0.44 MPa. A Zr-based pretreatment not only increases the surface roughness of the Mg alloy to the nanoscale but also facilitates the formation of chemical bonds at the interface between the Mg substrate and the PVDF coating. Owing to these combined effects, the adhesion strength is substantially increased to ~2.48 MPa.

Figure 4.

Pull-off adhesion strength for different samples.

To further elucidate the mechanism underlying the enhanced adhesion between Zr-pretreated Mg substrates and PVDF coatings, XPS analysis was performed on the substrates at different stages of the treatment process.

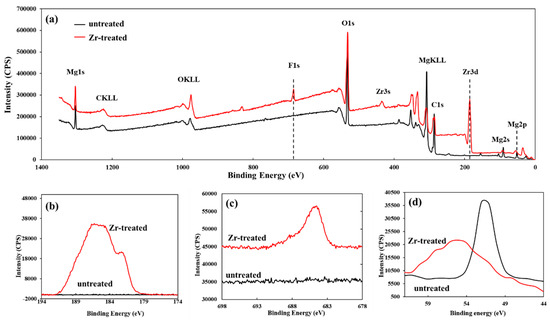

Figure 5 depicts the chemical changes occurring on the substrate surface with and without Zr-based pretreatment. As shown in the full XPS spectrum (Figure 5a), the surface of the raw Mg alloy primarily comprises O and Mg elements. In contrast, the Zr-pretreated Mg alloy surface is dominated by Zr, O, F, and Mg elements. This observation confirms the formation of a Zr- and F-containing surface layer on the Mg alloy after Zr-based pretreatment.

Figure 5.

XPS of untreated and Zr-treated samples. (a) full spectrum; (b) Zr 3d; (c) F 1s (d) Mg 2p.

The high-resolution XPS spectrum of the Zr 3d orbital (binding energy range: 180–190 eV; Figure 5b) exhibits peak positions consistent with the characteristic binding energies of Zr4+ in typical zirconium-containing compounds, including Zr(OH)4, ZrO2, and ZrF4 [43,44]. For the F 1s orbital, its high-resolution spectrum (centered at ~684 eV; Figure 5c) corresponds to metal-fluorine (M-F) bonds [45,46], which are primarily attributed to the formation of ZrF4 and MgF2 on the substrate surface. Furthermore, as to the Mg 2p orbital in Figure 5d, the Zr-treated Mg substrate shows a positive shift in the binding energy relative to the untreated substrate. This binding energy shift indicates a reduction in the electron density around Mg atoms, suggesting that the pretreated substrate surface acts as a Lewis base and donates electrons to the PVDF polymer [16]. As previously noted, the Zr-pretreated Mg alloy surface is dominated by hydroxide (e.g., Zr(OH)4) and oxide (e.g., ZrO2), these hydroxides can interact with acid-containing functional groups in the polymer. Specifically, they form interactions with the methylene (-CH2-) hydrogen atoms in PVDF, which facilitates the establishment of a stable substrate-coating interface. Notably, the Lewis basic behavior of Zr-pretreated Mg alloy surfaces has also been corroborated by other studies [15,47].

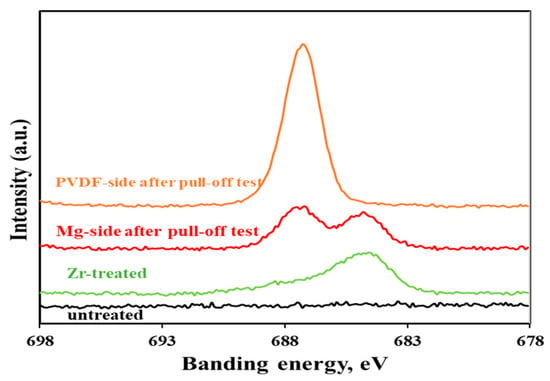

To clarify the interfacial failure mechanism of the coating system, X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) analysis was further conducted on the fracture surfaces of samples after the pull-off test, specifically targeting both the PVDF-coating side (PVDF-side) and Mg-substrate side (Mg-side) of the fractured interfaces. As depicted in Figure 6, the XPS results revealed that the Zr-treated surface contained fluoride, whereas no F signal was detected on the untreated Mg surface. Fluoride was employed as a marker element to detect residual traces of the Zr-based pretreatment film on the respective surfaces of the peeled samples. The F 1s peak in the XPS spectrum corresponds to the photoelectrons emitted from the core electrons closest to the nucleus of F atoms. These core electrons have a fixed binding energy characteristic of the F element, and their peak position and intensity can be used to confirm the presence of F-containing functional groups and analyze the chemical state of F in the coating system, with distinct binding energy ranges distinguishing metal fluorides (684–685.5 eV) from organic fluorides (688–689 eV). As illustrated in Figure 6, following the pull-off test, the PVDF-side of the fractured samples exhibited a single F 1s peak at 687.18 eV; this peak is exclusively attributed to the PVDF polymer itself. In contrast, the Mg-substrate-side of the fractured samples displayed two distinct F 1s peaks: one at 687.48 eV and another at 684.78 eV. The 687.48 eV peak corresponds to residual PVDF from the coating layer, while the 684.78 eV peak is indicative of fluoride species derived from the Zr-based pretreatment film. Collectively, these results confirm that failure occurred at the interface between the Zr-based pretreatment layer and the PVDF coating layer.

Figure 6.

F 1s peak in XPS from both the Mg-side and PVDF-side of a sample after pull-off test. (Untreated and Zr-treated samples are also shown for comparison).

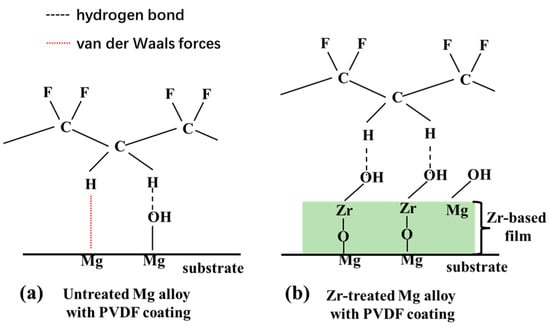

Figure 7b schematically illustrates a plausible interfacial interaction mechanism between the Zr-based pretreatment layer and the PVDF polymer. Compared with the interaction mechanism between the Mg alloy and PVDF coating (Figure 7a), the difference in interfacial forces is primarily determined by surface hydroxyl groups (-OH). Specifically, untreated magnesium alloys feature a thin native oxide film (MgO/Mg(OH)2) with sparse, unevenly distributed -OH groups, leading to weak interactions with PVDF, dominated by van der Waals forces and minimal scattered hydrogen bonds, which results in low adhesion. In contrast, zirconium treatment forms a Zr-based film (ZrO2 or hydroxylated zirconium compounds) with abundant, uniformly distributed -OH groups. These hydroxyls form dense, stable hydrogen bonds with H in PVDF’s -CH2- segments, and this effect synergizes with mechanical interlocking from the film’s micro-nano roughness to significantly enhance adhesion. This proposed interaction directly contributes to the enhanced adhesion strength of the PVDF coating, as quantified in Figure 4. Additionally, a relatively higher standard deviation was observed in the adhesion test results of Zr-pretreated samples. This variability, consistent with observations reported by Wojciechowska [47], is attributed to the non-uniform distribution of Lewis basic sites across the Mg alloy substrate surface.

Figure 7.

Schematic representation of the interface interaction. (a) between PVDF and untreated Mg alloy; (b) between PVDF and Zr-treated Mg alloy.

3.3. Anticorrosion Properties

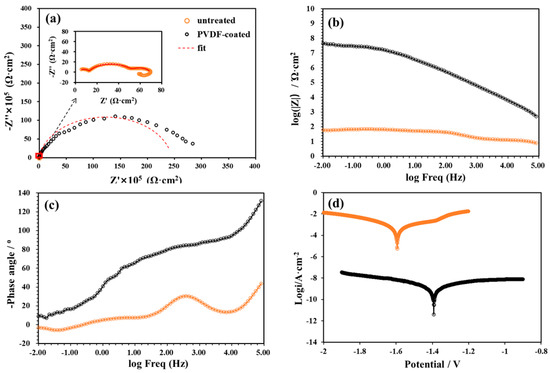

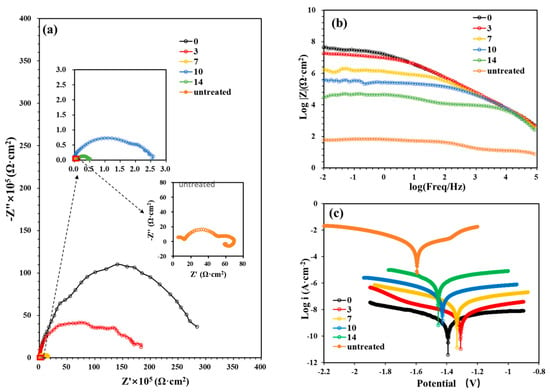

To evaluate the corrosion resistance of the as-prepared PVDF coatings, EIS and Tafel polarization measurements were conducted to investigate the instantaneous corrosion rate of the Mg alloy substrate, as shown in Figure 8. Critical electrochemical corrosion parameters, including corrosion potential (Ecorr), corrosion current density (Icorr), polarization resistance (Rₚ), and corrosion rate (CR), were extracted via the Tafel extrapolation method and summarized in Table 2. Moreover, to quantitatively assess the anticorrosion performance of the PVDF coatings, the corrosion protection efficiency (PE) was introduced. It is calculated via the Formula (3) below [48]:

where Icorr,u and Icorr,c denote the corrosion current density of the untreated and the PVDF-coated samples, respectively.

Figure 8.

EIS and Tafel spectra of untreated and PVDF-coated AZ31 Mg alloys in SBF. (a) Nyquist plot, (b) Impedance-frequency Bode plots; (c) Phase-frequency Bode plots; (d) Tafel plots.

Table 2.

Polarization parameters of different specimens from the Tafel plots.

In EIS spectra, the semicircular feature observed in the high-frequency region originates from the charge transfer reaction occurring at the metal-electrolyte interface; notably, the diameter of this semicircular impedance arc is representative of the Rp of the system [49,50]. A larger semicircular arc diameter in the Nyquist plot usually indicates better corrosion resistance of the specimen [51,52,53]. As shown in Figure 8a, the diameter of the capacitive loop for the PVDF-coated sample was significantly larger than that of the untreated sample, indicating that the hydrophobic PVDF coating substantially enhanced the corrosion protection of the Mg alloy.

Additionally, the untreated sample exhibited two capacitive loops in the middle to high frequency range, and an inductive loop in the low frequency range as shown in the magnified Nyquist plot (Figure 8a): corresponding to three independent corrosion processes: the dielectric response of the native oxide film at high frequencies, charge transfer from direct contact between the substrate and electrolyte (the core of corrosion reactions) at medium frequencies, and diffusion/accumulation of corrosion products at low frequencies. This reflects its rapid, stepwise corrosion mechanism in an unprotected state. In contrast, the PVDF-coated Mg alloy shows only one time constant due to the physical barrier effect of the coating, which couples the originally separate dielectric response of the coating and interfacial reactions while inhibiting corrosion product diffusion. This simplification of the corrosion pathway demonstrates effective protection by the coating.

The corresponding impedance modulus and phase angle plots are presented in Figure 8b,c. Typically, the impedance modulus at the lowest frequency (|Z|0.01 Hz) serves as a semi-quantitative indicator of the coating’s anticorrosion performance [54]. As depicted in Figure 8b, the |Z|0.01 Hz value of the PVDF-coated sample was higher than that of the untreated sample, demonstrating the coating’s excellent protective ability for the substrate. Additionally, the Bode-phase angle plot was analyzed to assess the coating’s protection performance. Higher phase angle values in the high-frequency range are typically associated with superior corrosion protection properties in specimens [55]. As shown in Figure 8c, the PVDF coating had a higher phase angle in the high-frequency domain. Collectively, these results confirm that the fabricated PVDF coating offers superior anticorrosive properties.

As presented in Table 2 and Figure 8d, relative to the untreated sample, the Ecorr of the PVDF-coated sample exhibited a positive shift of 0.202 V, rising from −1.594 V to −1.392 V. This positive shift in Ecorr is a clear indicator of a diminished corrosion tendency [49,50]. Concurrently, the Icorr of the PVDF-coated sample decreased by over five orders of magnitude; this is an observation that underscores the remarkable ability of the hydrophobic PVDF coating to enhance the corrosion protection of the Mg alloy in SBF. The Rp of the PVDF-coated sample was substantially higher than that of the untreated counterpart, with an approximate increase of six orders of magnitude. A higher Rp directly corresponds to a lower corrosion rate, further validating the coating’s protective efficacy. Notably, when compared to the untreated sample, the PVDF coating achieved an exceptionally high corrosion protection efficiency of 99.9998% and maintained an ultra-low corrosion rate of 1.185 × 10−3 mil/year. Collectively, these results confirm that the PVDF coating effectively impedes the penetration of corrosive ions, thereby significantly improving the corrosion resistance of the Mg alloy.

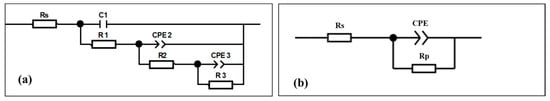

The EIS spectra can be simulated by the equivalent circuits (EC) as shown in Figure 9. The fitting results are presented in Table 3. From the table, the χ2 values of both samples are lower than 10−3, indicating excellent agreement between the experimental data and the fitted equivalent circuits. For untreated Mg alloy (Figure 9a), Rs is the resistance of electrolyte solution, R1 and C1 represent the resistance and constant phase element (CPE) of the porous corrosion product layer, which arise from the formation of corrosion products (MgO and Mg(OH)2) during immersion in SBF. R2 and CPE2 are the resistance and CPE of the native oxide layer, R3 represents the charge transfer resistance, and CPE3 indicates the CPE of the electric double layer related to the occurrence of electrochemical reactions. The fitting results show the untreated Mg alloy exhibits a relatively small charge transfer resistance R1 and R2 (11.01 and 39.93 Ω·cm2), consistent with its poor corrosion resistance. For the PVDF-coated Mg alloy (Figure 9b), the equivalent circuit is different. Rs is the resistance of the electrolyte solution, while Rp and CPE represent the resistance and constant phase element of the PVDF coating layer, respectively. The fitting results show that the PVDF-coated sample has a significantly higher Rp (2.45 × 107 Ω·cm2), confirming the coating’s effective barrier effect. This simplified circuit arises because the PVDF coating acts as a physical barrier, suppressing the independent processes observed in the untreated alloy and coupling the remaining electrochemical responses into a single time constant. It reflects the dominant role of the PVDF coating in blocking direct contact between the substrate and electrolyte.

Figure 9.

Equivalent circuits used for modelling EIS spectra. (a) untreated Mg alloy and (b) as-prepared PVDF-coated Mg alloy.

Table 3.

Fitting results of EIS.

3.4. Sustainable Anticorrosion Properties

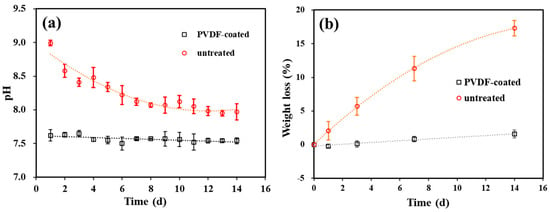

The sustainable corrosion protection performance of the PVDF coating was evaluated via an immersion test in SBF for 14 days, with the untreated Mg alloy serving as a reference. The chemical reactions during the immersion test follow Equations (1) and (2). As the reactions proceed, hydroxide ions are continuously generated; thus, the corrosion rate of the samples can be evaluated by measuring the pH value of the immersion solution, as shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

(a) pH and (b) weight loss as a function of immersion time.

Figure 10a illustrates the pH value of the SBF solution as a function of immersion time. For untreated samples, the pH value reached 9.0 on Day 1 of immersion and then declined to approximately 7.9 by Day 14. In contrast, the SBF solution for the PVDF-coated samples maintained lower and more stable pH values (ranging from 7.5 to 7.6) throughout the immersion test.

Figure 10b compares the weight-loss rates after 1, 3, 7, and 14 days of immersion. The weight-loss rate was calculated as the formula R = (W0 − Wt)/W0 × 100%, where W0 (in grams) is the initial weight of the sample before immersion and Wt is the weight after immersion. After the same period of immersion, the weight loss of the PVDF-coated sample was significantly lower than that of the untreated Mg alloy (1.6% vs. 17.3% after 14 days), indicating that the PVDF coating effectively inhibits the degradation of the AZ31 Mg alloy.

The surface morphologies of corroded samples after immersion in SBF for 1 and 14 days are shown in Figure 11.

Figure 11.

Surface morphologies of corroded samples after immersion in SBF. (a) untreated, 1 day; (b) untreated, 14 days; (c) PVDF-coated, 1 day; (d) PVDF-coated, 14 days.

The untreated substrate exhibited significant degradation after just 1 day of exposure to the SBF solution, with numerous cracks appearing on its surface. As the immersion time extended to 14 days, uneven corrosion pits and defects were formed (Figure 11b). Therefore, the geometric shape of the substrate was altered, as indicated by the inset of Figure 11b. In contrast to the untreated samples, the PVDF-coated samples maintained a surface morphology similar to their original state. Even after 14 days of immersion, only slight corrosion was found, as shown in Figure 11d. There were no cracks, but there were large holes; so, the geometric shape remained unchanged (inset of Figure 11d). The coating retained a porous structure, with some deposition products dispersed within the holes, as depicted in the zoom-in views of Figure 11c,d.

The sustainable stability and corrosion protection performance of the PVDF coating were further investigated via EIS and Tafel polarization tests, with the corresponding results presented in Figure 12. The electrochemical corrosion parameters derived from the Tafel curves are summarized in Table 4.

Figure 12.

EIS and Tafel spectra of PVDF-coated AZ31 Mg alloys in SBF as a function of immersion times. (a) Nyquist plots, (b) Impedance-frequency Bode plots, (c) Tafel plots.

Table 4.

Polarization parameters of different specimens from the Tafel curve.

As the immersion time increased, the diameters of the capacitive arcs in the EIS spectra gradually decreased, and the |Z|0.01Hz values declined (Figure 12a,b). Correspondingly, with the prolongation of immersion time, the Icorr of the PVDF-coated sample increased from 1.27 × 10−9 to 9.69 × 10−7 A/cm2, the Rp decreased from 107 to 104 Ω/cm2, the PE decreased from 99.9998% to 99.8348%, and the CR increased from 1.19 × 10−3 to 9.08 × 10−1 mil/year. These findings demonstrate that the PVDF coating’s corrosion resistance diminished slightly over the test period, probably due to the sustained penetration of corrosive agents from the immersion medium through the coating matrix.

Notably, even after 14 days of immersion, the diameter of the capacitive arc, |Z|0.01Hz values, Rp, PE, and Icorr of the PVDF-coated sample remained significantly more favorable compared to those of the untreated Mg alloy. This confirms that the PVDF coating can provide sustainable corrosion protection for Mg alloys.

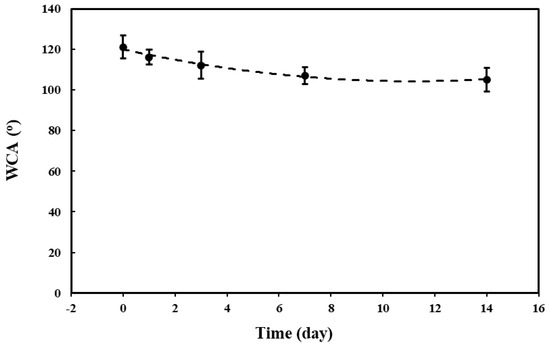

The hydrophobic stability of the PVDF coating is essential for achieving sustainable corrosion protection of the Mg alloy. Figure 13 shows the variations in the WCA of the PVDF coating immersed in SBF solution for 14 days. The results indicate that the WCA of the as-prepared PVDF coating gradually decreases with increasing immersion time, yet it maintains hydrophobic properties within the 14-day immersion period. In the early immersion stage (0–7 days), the WCA decreases from the initial ~121° to ~107° (a change of ~11.6%), which is attributed to the infiltration of SBF into the 2nd porous PVDF layer and the deposition of corrosion products on the coating surface. This deposition alters the local surface energy, resulting in the observed change in WCA. In the mid-to-late stage (7–14 days), the WCA decreases slightly, from ~107° to ~105° (a change of ~1.9%) and the curve tends to flatten. This can be attributed to the protective effect of the 1st dense PVDF layer. This negligible variation indicates that the PVDF coating has achieved stable interaction with the SBF environment. Overall, the PVDF coating demonstrates good sustainable stability and anticorrosion performance.

Figure 13.

The WCA of the PVDF coating as a function of immersion times.

3.5. Protective Mechanism Analysis

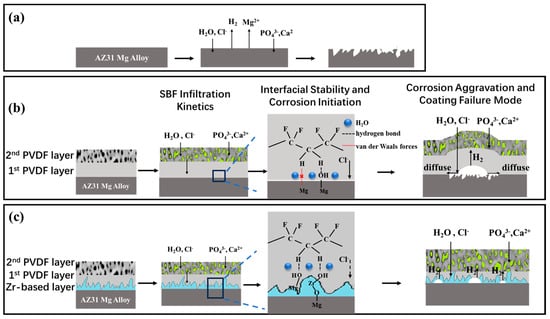

A schematic illustration of the corrosion protection mechanism of the PVDF coating on the Zr-treated Mg alloy is presented in Figure 14.

Figure 14.

A schematic illustration of the corrosion steps. (a) bare Mg alloy; (b) PVDF coating on Mg alloy; (c) PVDF coating on Zr-treated Mg alloy.

For the untreated Mg alloy (Figure 14a), aggressive agents like Cl− and H2O directly attack the substrate surface, initiating rapid corrosion, as confirmed by Figure 11a.

The corrosion protection efficacy of PVDF coatings on AZ31 magnesium alloys varies significantly with the introduction of a Zr-based pretreatment film. This difference is reflected in the dynamic evolution of electrolyte infiltration, interfacial stability, and corrosion propagation during SBF immersion, where the Zr-based film acts as a key regulatory layer. The stage-specific mechanisms of the two coating systems are systematically elaborated in the following:

- 1.

- Initial Immersion Stage: SBF Infiltration Kinetics

For both the PVDF coatings on untreated and Zr-treated AZ31 alloys, the infiltration rate of SBF into the intrinsic pores of the second PVDF layer is relatively slow in the initial immersion period, owing to the hydrophobicity of the PVDF matrix. Meanwhile, Cl− ions and H2O molecules gradually diffuse through pinholes and defects in the first PVDF layer toward the substrate. Overall, the PVDF coating mitigates electrolyte penetration and provides a temporarily intact physical barrier for the AZ31 substrate.

At this point, for the PVDF coating on the Zr-treated AZ31 alloy (Figure 14c), the Zr-based pretreatment film introduces a dual-barrier effect to slow SBF infiltration. After SBF permeates the PVDF layer, the Zr-based film (with a thickness of ~200 nm, characterized in Figure 2b) serves as an additional diffusion barrier, increasing the mass transfer resistance of SBF. The combined effect of PVDF hydrophobicity and Zr-film diffusion resistance extends the “barrier integrity period” of the coating system.

- 2.

- Mid-Term Immersion Stage: Interfacial Stability and Corrosion Initiation

For the PVDF coating on untreated AZ31 alloy, prolonged immersion causes SBF to accumulate at the PVDF-substrate interface, triggering cascading degradation processes (as shown in Figure 14b). Specifically, water molecules adsorbed in the coating pores induce hydrolysis of the weak van der Waals forces at the PVDF-Mg interface.

For the PVDF coating on Zr-treated AZ31 alloy, the Zr-based film mitigates interfacial degradation and corrosion initiation. As verified in Figure 7, the Zr-based film forms chemical bonds with both the Mg substrate and PVDF coating, thereby enhancing interfacial bonding strength. This chemical bonding resists water-induced hydrolysis and maintains interfacial integrity.

- 3.

- Extended Immersion Stage: Corrosion Aggravation and Coating Failure Mode

For the PVDF coating on the untreated AZ31 alloy, Cl− ions and H2O molecules react with the Mg substrate to produce Mg(OH)2 and H2. The generated H2 gas accumulates at the interface, creating a local pressure that exceeds the interfacial bonding strength of the PVDF-only system. This pressure causes the PVDF film to detach, forming interfacial gaps that accelerate the diffusion of corrosive species. Eventually, large H2 bubbles and local PVDF peeling are observed, with the coating losing effective protection.

For the PVDF coating on Zr-treated AZ31 alloy, the Zr-based film provides extended protection by not only reducing H2 generation but also preventing the formation of interfacial diffusion channels through maintaining interfacial bonding.

In summary, the Zr-based pretreatment film enhances the corrosion protection performance of PVDF coatings on AZ31 magnesium alloys through multi-stage regulatory effects, including slowing early electrolyte infiltration, stabilizing the interface in the mid-term, and delaying corrosion aggravation in the long term.

4. Conclusions

A hydrophobic PVDF coating was fabricated via the dip-coating method on a Zr-treated AZ31 Mg alloy to provide corrosion protection. The Zr-based pretreatment is critical for enhancing PVDF-substrate adhesion and sustainable protection. XPS, WCA, EIS, and Tafel tests validated that the proposed coating scheme offers a promising approach to improve the corrosion resistance of AZ31 magnesium alloy, enabling its potential applications in the biomedical field. Specifically, the following was observed:

- (1)

- Zr-based pretreatment significantly boosts the adhesion between PVDF and AZ31 alloy. XPS of post-pull-off surfaces confirms interfacial chemical bonding.

- (2)

- The WCA results showed that the PVDF coating achieved excellent hydrophobicity with WCA > 120°; thus, it can act as an excellent physical corrosion barrier.

- (3)

- The electrochemical and immersion test results showed PVDF-coated samples have much lower Icorr and higher Rp than untreated AZ31, validating superior corrosion protection of PVDF coating.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.F.; Methodology, Q.L.; Formal analysis, H.F. and D.W.; Investigation, C.Z., Y.J. and S.L.; Data curation, D.W.; Writing—original draft, C.Z.; Writing—review & editing, H.F.; Funding acquisition, H.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Foundation of Jinling Institute of Technology (jit-b-202155).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Li, N.; Zheng, Y.F. Novel magnesium alloys developed for biomedical application: A review. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2013, 29, 489–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, R.; Pandiaraj, S.; Muthusamy, S.; Panchal, H.; Alsoufi, M.S.; Ibrahim, A.M.M.; Elsheikh, A. Biodegradable magnesium metal matrix composites for biomedical implants: Synthesis, mechanical performance, and corrosion behavior—A review. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2022, 20, 650–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.N.; Cao, P.; Zhang, X.N.; Zhang, S.X.; He, Y.H. In vitro degradation and cell attachment of a PLGA coated biodegradable Mg–6Zn–based alloy. J. Mater. Sci. 2010, 45, 6038–6045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.; Gao, Z. Recent research advances on corrosion mechanism and protection, and novel coating materials of magnesium alloys: A review. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 8427–8463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y.; Liu, W.; Ngai, T. Polymer coatings on magnesium-based implants for orthopedic applications. J. Polym. Sci. 2022, 60, 32–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boga, K.; Pothu, R.; Arukula, R.; Boddula, R.; Gaddam, S.K. The role of anticorrosive polymer coatings for the protection of metallic surface. Corros. Rev. 2021, 39, 547–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecellio, M. Opportunities and developments in fluoropolymeric coatings. Prog. Org. Coat. 2000, 40, 225–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, N.E.; Skazik, C.; Harwardt, M.; Bartneck, M.; Denecke, B.; Klee, D.; Salber, J.; Zwadlo-Klarwasser, G. Topographical control of human macrophages by a regularly microstructured polyvinylidene fluoride surface. Biomaterials 2008, 29, 4056–4064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klee, D.; Ademovic, Z.; Bosserhoff, A.; Hoecker, H.; Maziolis, G.; Erli, H.J. Surface modification of poly (vinylidenefluoride) to improve the osteoblast adhesion. Biomaterials 2003, 24, 3663–3670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szewczyk, P.K.; Metwally, S.; Karbowniczek, J.E.; Marzec, M.M.; Stodolak-Zych, E.; Gruszczyński, A.; Bernasik, A.; Stachewicz, U. Surface-potential-controlled cell proliferation and collagen mineralization on electrospun polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) fiber scaffolds for bone regeneration. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 5, 582–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, Y.K.A.; Zou, X.; Fang, Y.M.; Wang, J.L.; Lin, W.S.; Boey, F.Y.C.; Ng, K.W. β-phase poly (vinylidene fluoride) films encouraged more homogeneous cell distribution and more significant deposition of fibronectin towards the cell–material interface compared to α-phase poly (vinylidene fluoride) films. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2014, 34, 345–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munekata, S. Fluoropolymers as coating material. Prog. Org. Coat. 1988, 16, 113–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deflorian, F.; Fedrizzi, L.; Lenti, D.; Bonora, P.L. On the corrosion protection properties of fluoropolymer coatings. Prog. Org. Coat. 1993, 22, 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Conceicao, T.F.; Scharnagl, N.; Blawert, C.; Dietzel, W.; Kainer, K.U. Surface modification of magnesium alloy AZ31 by hydrofluoric acid treatment and its effect on the corrosion behaviour. Thin Solid Film. 2010, 518, 5209–5218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Conceicao, T.F.; Scharnagl, N.; Dietzel, W.; Hoeche, D.; Kainer, K.U. Study on the interface of PVDF coatings and HF-treated AZ31 magnesium alloy: Determination of interfacial interactions and reactions with self-healing properties. Corros. Sci. 2011, 53, 712–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.Y.; Zuo, Y.; Zhao, X.H.; Tang, Y. The improved performance of a Mg-rich epoxy coating on AZ91D magnesium alloy by silane pretreatment. Corros. Sci. 2012, 60, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamshidipour, Z.; Toorani, M.; Aliofkhazraei, M.; Mahdavian, M. Reducing damage extent of epoxy coating on magnesium substrate by Zr-enhanced PEO coating as an effective pretreatment. J. Magnes. Alloys 2023, 11, 641–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Li, M.; Wang, H. Progress in Micro-arc Oxidation Pretreatment for Composite Coatings on Light Alloys. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2023, 458, 129876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Chen, J.; Zhao, Y. Enhanced Adhesion and Corrosion Resistance of Self-healing Coatings on Mg Alloys via MAO Pretreatment. Corros. Sci. 2022, 201, 110389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Bai, H.H.; Feng, Z.Y. Advances in the Modification of Silane-Based Sol-Gel Coating to Improve the Corrosion Resistance of Magnesium Alloys. Molecules 2023, 28, 2563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, N.; Li, J.; Li, W.; Lin, X.S.; Fu, Q.Y.; Peng, X.; He, W.H.; Yu, Z.T.; Chu, P.K. Poly (lactic acid) coating with a silane transition layer on MgAl LDH-coated biomedical Mg alloys for enhanced corrosion and cytocompatibility. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2023, 661, 130947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafeez, M.A.; Farooq, A.; Zang, A.; Saleem, A.; Deen, K.M. Phosphate chemical conversion coatings for magnesium alloys: A review. J. Coat. Technol. Res. 2020, 17, 827–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaghefinazari, B.; Wierzbicka, E.; Visser, P. Chromate-Free Corrosion Protection Strategies for Magnesium Alloys—A Review: PART I—Pre-Treatment and Conversion Coating. Materials 2022, 15, 8676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramezanzadeh, B.; Vakili, H.; Amini, R. The effects of addition of poly (vinyl) alcohol (PVA) as a green corrosion inhibitor to the phosphate conversion coating on the anticorrosion and adhesion properties of the epoxy coating on the steel substrate. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2015, 327, 174–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.D.; Liu, M.Y.; Chen, N.; Sun, X. Corrosion properties of Sol–Gel silica coatings on phosphated carbon steel in sodium chloride solution. J. Sol-Gel Sci. Technol. 2015, 76, 358–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Weng, Z.Y.; Yuan, W.; Luo, X.; Wong, H.M.; Liu, X.; Wu, S.; Yeung, K.W.K.; Zheng, Y.; Chu, P.K. Corrosion resistance of dicalcium phosphate dihydrate/poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid) hybrid coating on AZ31 magnesium alloy. Corros. Sci. 2016, 102, 209–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Dong, K.; Song, Y.; Cheng, X.; Han, E.H. Study on the phosphate/electrophoretic composite coatings on Mg alloy: The effect of phosphate conversion films on adhesion strength and corrosion resistance. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2024, 489, 131109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Conceição, T.F.; Scharnagl, N. Fluoride conversion coatings for magnesium and its alloys for the biological environment. In Surface Modification of Magnesium and Its Alloys for Biomedical Applications; Woodhead Publishing: Sawston, UK, 2015; pp. 3–21. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, H.; Chen, S. Comparative investigation on corrosion resistance of MgF2 coated, PLA coated and composite coated biodegradable magnesium alloy wires for medical application. Vacuum 2024, 222, 113021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sababi, M.; Terryn, H.; Mol, J.M.C. The influence of a Zr-based conversion treatment on interfacial bonding strength and stability of epoxy coated carbon steel. Prog. Org. Coat. 2017, 105, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, P.; Darvish, E.; Shahini, M.H.; Mohammadloo, H.E.; Behzadnasab, M.; Ghamsarizade, R. New hybrid organic-inorganic conversion coating applied on the Al2024 substrate: Electrochemical, adhesion and surface study. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1010, 177033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jawad, M.; Zhao, J.M.; Mubeen, M.; Tabish, M.; Mahmood, M.; Murtaza, H.; Wang, J.; Lv, Y.; Liu, H.; Fan, B. Dual-functional sodium 1-dodecanesulfonate-enhanced TiZr conversion coatings on Zn-Al-Mg coated steel: Improved adhesion and filiform corrosion resistance. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1015, 178856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.F.; Wen, C.; Hodgson, P.; Li, Y. Effects of alloying elements on the corrosion behavior and biocompatibility of biodegradable magnesium alloys: A review. J. Mater. Chem. B 2014, 14, 1912–1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Radha, A.S.D.; Dymock, D.; Younes, C.; O’Sullivan, D. Surface properties of titanium and zirconia dental implant materials and their effect on bacterial adhesion. J. Dent. 2011, 40, 146–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, H.L.; Wei, D.L.; Zhu, C.H.; Liu, S.Y.; Lin, Q. Formation and characterization of zirconium-based conversion film on AZ31 magnesium alloy. Mater. Res. Express 2024, 11, 096521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdi, R.I.; Gan, W.C.; Halim, N.A.; Velayutham, T.S.; Majid, W.H.A. Ferroelectric and pyroelectric properties of novel lead-free polyvinylidenefluoride-trifluoroethylene–Bi0.5Na0.5TiO3 nanocomposite thin films for sensing applications. Ceram. Int. 2015, 41, 13836–13843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahan, R.M.; Arshad, A.N.; Razif, M.H.M.; Mahmud Zohdi, N.S.; Mahmood, M.R. Structural and electrical properties of PVDF-TRFE/ZnO bilayer and filled PVDF-TRFE/ZnO single layer nanocomposite films. Adv. Mater. Process. Technol. 2017, 3, 300–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, R.; Mishra, S.; Unnikrishnan, L.; Mohanty, S.; Mahapatra, S.; Nayak, S.K.; Anwar, S.; Ramadoss, A. Enhanced dielectric and piezoelectric properties of Fe-doped ZnO/PVDF-TRFE composite films. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2020, 117, 105173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persano, L.; Dagdeviren, C.; Su, Y.W.; Zhang, Y.; Girardo, S.; Pisignano, D.; Huang, Y.; Rogers, J.A. High performance piezoelectric devices based on aligned arrays of nanofibers of poly (vinylidenefluoride-co-trifluoroethylene). Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, W.M.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, Q.P.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, Y. Dependence of dielectric, ferroelectric, and piezoelectric properties on crystalline properties of P (VDF-co-TRFE) copolymers. J. Polym. Sci. Part B Polym. Phys. 2012, 50, 1271–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, A.M.A.; Alateyah, A.I.; Hasan, H.; Matli, P.R.; El-Sayed Seleman, M.M.; Ahmed, E.; El-Garaihy, W.H.; Golden, T.D. Enhanced Corrosion Resistance and Surface Wettability of PVDF/ZnO and PVDF/TiO2 Composite Coatings: A Comparative Study. Coatings 2023, 13, 1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakradhar, R.P.S.; Prasad, G.; Bera, P.; Anandan, C. Stable superhydrophobic coatings using PVDF–MWCNT nanocomposite. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2014, 301, 208–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taheri, P.; Lill, K.; de Wit, J.W.H.; Mol, J.M.C.; Terryn, H. Effects of zinc surface acid-based properties on formation mechanisms and interfacial bonding properties of zirconium-based conversion layers. J. Phys. Chem. C 2012, 116, 8426–8436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdier, S.; Delalande, S.; van der Laak, N.; Metson, J.; Dalard, F. Monochromatized x-ray photoelectron spectroscopy of the AM60 magnesium alloy surface after treatments in fluoride-based Ti and Zr solutions. Surf. Interface Anal. 2005, 37, 509–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawamoto, Y.; Ogura, K.; Shojiya, M.; Takahashi, M.; Kadono, K. F1s XPS of fluoride glasses and related fluoride crystals. J. Fluor. Chem. 1999, 96, 135–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malka, I.E.; Pisarek, M.; Czujko, T.; Bystrzycki, J. A study of the ZrF4, NbF5, TaF5, and TiCl3 influences on the MgH2 sorption properties. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2011, 36, 12909–12917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojciechowska, M.; Zieliński, M.; Pietrowski, M. MgF2 as a non-conventional catalyst support. J. Fluor. Chem. 2003, 120, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.X.; Mu, P.; Wang, Q.T.; Li, J. Superhydrophobic ZIF-8 based dual-layer coating for enhanced corrosion protection of Mg alloy. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 35453–35463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.Y.; Ma, Y.B.; Sun, Y.Y.; Xiong, Z.; Qi, C.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y. Robust superhydrophobic surface based on multiple hybrid coatings for application in corrosion protection. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 6512–6526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, S.L.; Wang, Z.L.; Wang, Y.K.; Bai, X.; Fu, Y.Q.; Guo, B.; Tan, C.; Zhang, J.; Hu, P. Roll-to-roll manufacturing of robust superhydrophobic coating on metallic engineering materials. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 2174–2184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Revilla, R.I.; Liu, Z.Y.; Zhang, D.; Li, X.; Terryn, H. Effect of inclusions modified by rare earth elements (Ce, La) on localized marine corrosion in Q460NH weathering steel. Corros. Sci. 2017, 129, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.Y.; Li, X.G.; Du, C.W.; Cheng, Y.F. Local additional potential model for effect of strain rate on SCC of pipeline steel in an acidic soil solution. Corros. Sci. 2009, 51, 2863–2871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.Y.; Li, X.G.; Cheng, Y.F. Understand the occurrence of pitting corrosion of pipeline carbon steel under cathodic polarization. Electrochim. Acta 2012, 60, 259–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, J.; Zhou, G.X.; He, P.G.; Yang, Z.H.; Jia, D.C. 3D printing strong and conductive geo-polymer nanocomposite structures modified by graphene oxide. J. Carbon 2017, 117, 421–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, G.Y.; Zhang, M.; Zhao, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, H.; Zhang, X.; Yan, H. High corrosion protection performance of a novel nonfluorinated biomimetic superhydrophobic Zn/Fe coating with echinopsis multiplex-like structure. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 38205–38217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).