Abstract

This study introduces a Ni15 intermediate layer to address cracks and low laser absorption in laser cladding of pure copper on 45 steel, preventing thermal stress and improving bonding strength. TiBN ceramic particles are added to enhance laser absorption and improve surface strength and wear resistance. Cu-TiBN gradient coatings with varying TiBN contents (0–8 wt.%) were fabricated on 45 steel. The study examines the coatings’ morphology, microstructure, phase composition, hardness, tribological performance, and wear mechanisms. Results show that TiBN alters the coating’s structure, refining the grains. With TiBN content over 4%, the coating mainly consists of the CuNi phase, and strengthening phases like NiTi and Cu2Ti form. Hardness increases from 66HV0.1 to 270HV0.1. The Cu-TiBN gradient coating outperforms pure copper in mechanical properties and wear resistance. The coating with 2% TiBN has the lowest friction coefficient (0.637), but higher TiBN content increases brittleness and cannot play a good role in reducing friction. The study demonstrates that TiBN boosts laser efficiency and wear resistance in copper-based coatings, offering a novel approach to laser cladding.

1. Introduction

Based on the design concept that steel bears mechanical loads while copper provides functional characteristics, heterogeneous mechanical components composed of steel and copper have been widely employed under complex working conditions. The primary advantage lies in their ability to enhance overall performance by leveraging the complementary properties of the materials. Through strategic material selection and optimized processing protocols, steel–copper heterogeneous components demonstrate synergistically enhanced performance under extreme operating conditions, enabling their adoption as critical engineering solutions in mechanical engineering, energy systems, and transportation infrastructure. For example, in applications such as conductive contacts, internal combustion engine bearing shells, condenser tube sheets, and rocket nozzle bushings, the steel skeleton ensures structural rigidity, while copper enables high electrical and thermal conductivity, efficient heat dissipation, and self-lubrication. For reducing wear, frictional heat, and achieving other functional enhancements, various techniques have been developed to deposit copper and copper alloys onto steel surfaces, including plasma spraying [1], cold spraying [2], physical vapor deposition [3], chemical vapor deposition [4], and laser cladding [5]. Among these technologies, laser cladding technology is widely used because of its low dilution rate of the cladding layer, accurate control of the composition ratio, good metallurgical bonding with the substrate, and environmentally friendly and clean preparation process. The primary obstacles in laser cladding copper onto steel stem from their substantial thermophysical property mismatch: a ~500 °C difference in melting point and over tenfold higher thermal conductivity of copper. Compounding this, the high reflectivity of copper against infrared lasers promotes pore and crack formation in the resultant cladding layer. Nie et al. [6] investigated the melt flow behavior in relation to laser scanning speed during laser cladding of pure copper through experiments and numerical simulations. The results revealed that the temperature gradient in the molten pool increases with increasing scanning speed, which aggravates Fe segregation and increases the surface tension gradient. In an evaluation of pure copper coatings, Singh et al. [7] reported that the coating produced via laser cladding possessed roughly twice the adhesion strength of the coating deposited by cold spraying. However, coatings produced by laser cladding often exhibit pore defects. Yadav et al. [8] fabricated pure copper bulk samples with a thickness of 5 mm via direct laser deposition. These coatings exhibited various defects, including inclusions and pores. These findings indicate that pure copper coatings directly fabricated on steel substrates using infrared lasers typically suffer from defects, including elemental segregation, pores, and cracks. Tian et al. [9] demonstrated that introducing a Co06 coating with an IN718 transition layer onto a RuT450 substrate could effectively prevent elemental segregation, inhibit crack formation, and reduce the internal stress gradient. Xue et al. [10] fabricated a composite coating on damaged H13 tool steel using laser cladding, beginning with a Ni25 alloy transition layer and subsequently an Fe104 alloy reinforcing layer. It was found that the Ni25 transition layer effectively addresses the issue of poor bonding with the substrate without introducing significant defects. The use of a nickel-based alloy as a transition layer is therefore an effective method for improving interfacial bonding and enhancing the overall toughness of the coating. In response to the challenges associated with laser cladding copper powder, investigators have explored two main approaches. One is to change the laser wavelength, use a blue laser [11] or change the laser light path [12] to enhance the absorption rate of Cu powder to laser beam energy. The second strategy enhances the laser energy coupling of the powder by introducing highly absorptive alloying elements [13,14]. Our prior investigations have identified TiBN ceramic particles as a suitable reinforcing phase owing to their high hardness, strong interfacial adhesion, and superior oxidation resistance [15]. TiBN is also an excellent light-absorbing material with high light absorption capacity in the visible and infrared light range [16,17]. Adding ceramic particles with high absorbance to Cu powder can not only improve the overall hardness, wear resistance, and corrosion resistance of the cladding layer but also increase the laser beam energy absorption of pure copper powder during cladding. The incorporation of TiBN particles into the copper powder thereby provides a pathway to substantially improve the comprehensive performance of the resulting composite material.

In summary, the physical property incompatibility between 45 steel and copper, which leads to defects during laser cladding, can be mitigated by employing a Ni-based transition layer and TiBN ceramic reinforcement. This approach effectively enhances the integrity and overall performance of the resultant pure copper coating. However, the microstructural evolution mechanism of laser-cladded Cu-TiBN gradient coatings and its influence on properties has not yet been investigated. The influence of varying TiBN content on the microstructure, hardness, and wear resistance of Cu-TiBN gradient coatings remains unclear. Therefore, we first fabricated a Ni15 transition layer on the 45 steel substrate by laser cladding. Wear-resistant Cu-TiBN functional coatings with varying TiBN contents were then built up on this Ni15 interlayer. The microstructural evolution, phase formation, hardness, and wear resistance of the laser-clad Cu-TiBN gradient coatings were characterized as a function of TiBN content to establish the composition-property relationships. The results provide a theoretical basis for understanding how varying amounts of TiBN ceramic reinforcement affect the microstructure and properties of Cu-TiBN gradient coatings.

The purpose of the research is to prepare copper-steel bimetallic components by laser cladding technology and to enhance the working life of the wear-resistant working layer through the Cu-TiBN gradient coating with TiBN ceramic reinforcement.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

This study utilized a 45 steel substrate (60 mm × 40 mm × 10 mm). A KF-Ni15 interlayer was deposited to relieve thermal stress and strengthen the interfacial bond with the pure copper coating. The mechanical and tribological properties were subsequently enhanced by incorporating a self-synthesized TiBN ceramic reinforcement. The chemical compositions of the substrate and interlayer material are detailed in Table 1. TiBN powder exhibits both ceramic and metallic characteristics, and it does not readily form intermetallic compounds with copper. As a reinforcing phase, TiBN demonstrates high structural stability within the Cu matrix and contributes to reducing friction and improving wear resistance.

Table 1.

The main components (wt.%) of 45 steel and KF-Ni15.

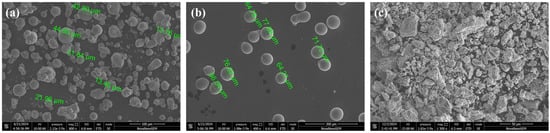

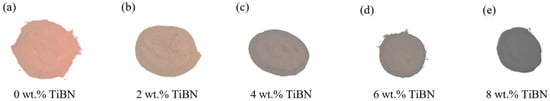

KF-Ni15 alloy powder was purchased from Beikang New Materials Technology Co., Ltd (Beijing, China). Copper powder (purity greater than 99.99%,45 μm) was purchased from Changsha Tianjiu Metal Materials Co., LTD (Changsha, China). Self-made TiBN powder (purity greater than 99.5%, 6 μm). The powders of TiBN, Cu and KF-Ni15 are shown in Figure 1. A certain amount of TiBN powder was added to the copper powder and mixed according to the specified weight ratio. It was mixed in a planetary mill at a speed of 30 rpm for 2 h, and the ball-to-powder ratio was 2:1. Cu-TiBN powders with different TiBN contents are shown in Figure 2. It can be observed that with the increase in TiBN content, the color of Cu-TiBN mixed powder changed from reddish brown to dark brown, and finally to black. Usually, the dark powder has a high laser absorption coefficient, which can effectively absorb the energy of the laser and convert it into heat to increase the melting rate of the powder [14]. Light-colored powders require more time or increase laser beam power to overcome the loss of reflected energy [18]. The addition of TiBN to pure copper powder effectively reduces its laser reflectivity while maintaining excellent sphericity and fluidity. This leads to a fundamental improvement in the coating’s formability. Before use, the powder was subjected to drying in a vacuum oven at 100 °C for 2 h.

Figure 1.

Micro-morphology of powder materials: (a) Cu; (b) Ni15 alloy; (c) TiBN [19].

Figure 2.

Cu-TiBN powder color with different TiBN contents: (a) 0 wt.% TiBN; (b) 2 wt.% TiBN; (c) 4 wt.% TiBN; (d) 6 wt.% TiBN; (e) 8 wt.% TiBN.

2.2. Preparation Process and Parameters of the Coating

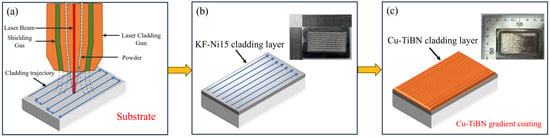

The laser cladding manufacturing process of the Cu-TiBN gradient coating consists of two main steps: preparation of the Ni15 transition layer and the Cu-TiBN wear-resistant functional layer. The preparation process is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Cu-TiBN gradient coating manufacturing process [19].

Before coating, the surface of the 45 steel substrate is successively ground and ultrasonically cleaned with 180-mesh and 320-mesh sandpapers to remove impurities on the substrate surface. The Ni15 and Cu-TiBN coatings were prepared by laser cladding equipment. The experimental laser cladding process is precisely controlled by the YLR-3000-U-K fiber laser and the FANUC six-axis industrial robot (M-10iD/16S). The protective gas is high-purity argons. Based on previous studies, the optimized process parameters are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Process parameters for the preparation of Cu-TiBN samples.

2.3. Microstructure and Phase Composition of the Cladding Layer

In order to observe the microstructure of Cu-TiBN gradient coating, the sample of 10 mm × 10 mm × 10 mm was cut by electric spark cutting machine in the middle of the cladding layer, and the XQ-2B metallographic mosaic machine was used for mosaic. The metallographic samples were prepared by 180 mesh, 320 mesh, 600 mesh, 800 mesh, 1200 mesh, 1500 mesh and 2000 mesh water sandpaper, and corroded with FeCl3 hydrochloric acid solution FeCl3: HCl: alcohol = 5 g:5 mL:95 mL, corrosion time 5–10 s, and then washed with alcohol, blown dry with a hairdryer. The surface morphology, microstructure and element distribution of the cross-section wear surface of the cladding layer were observed by IE500 OM and scanning electron microscope SEM (model Nova Nano SEM 450, Oxford electric refrigeration spectrometer, FEI company, Hillsboro, OR, USA). We analyzed the phase composition of the composite gradient coating by X-ray diffraction (XRD) to determine the constituent phases. The scanning speed is selected as 2°/min. According to the experimental materials, the 2θ Angle range is chosen as 20° to 90°. Vickers microhardness was assessed on an HVS-1000A tester under standard conditions: a 100 g load and a 15 s dwell time. To map the hardness distribution, indentations were made at 200 μm intervals along two perpendicular directions: vertically from the coating surface to the substrate, and horizontally across the entire sample width. To reduce the possible error values in the experiment, at least three measurements are conducted in each test area of each sample in the hardness test. Finally, the data is averaged to be taken as the final test result.

2.4. Friction Test Procedure

Friction and wear tests were conducted on the composite coatings with various TiBN contents using an MM-1000 isokinetic friction tester. Each group of samples should be tested at least three times as well to reduce possible errors. A WC ball (with a diameter of 6 mm) serves as a counter. The test was conducted at room temperature with a load of 100 g, a frequency of 1 hz, a sliding time of 30 min, and a single sliding distance of 6 × 10−3 m. The conditions for each test are the same to ensure the consistency of the experiment. The instrument selected for detecting the depth and width of coating wear marks is a laser scanning confocal microscope (KEYENCE, VK-X110, Osaka, Japan). The combined analysis of the wear tracks via scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) was conducted to elucidate the underlying wear mechanisms of the composite coating.

3. Results

3.1. Microstructure Analysis of Laser Cladding Layer

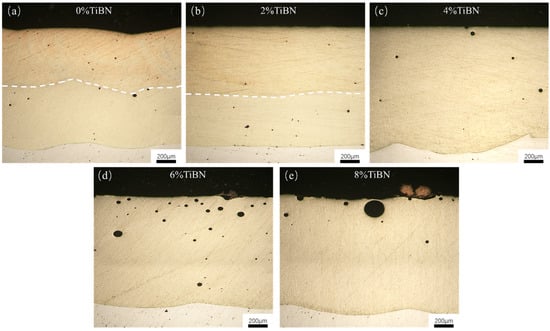

3.1.1. Macroscopic Morphology Analysis of Cu-TiBN Gradient Coatings with Different Content of TiBN

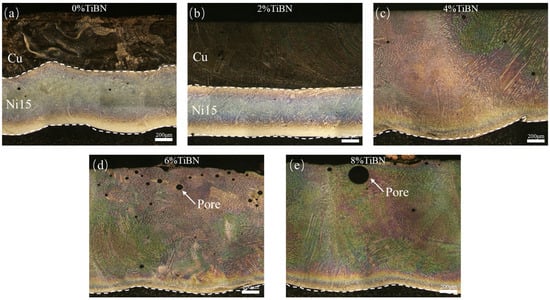

Figure 4 shows the macroscopic morphology of Cu-TiBN gradient coatings with different TiBN contents, with an average coating thickness of approximately 1.8 mm. It can be observed that a distinct interfacial layer exists between the Cu and Ni15 cladding layers in the samples without TiBN and with 2 wt.% TiBN. However, when the TiBN content increases to 4–8 wt.%, the interface between the Cu and Ni15 layers becomes indistinct, indicating improved metallurgical bonding across the layers. All coatings are free from defects and show excellent metallurgical bonding to the 45 steel substrate. Notably, the regions with 0–4 wt.% TiBN addition are virtually pore-free. As the TiBN content increases, the absorption of laser beam energy by the cladding layer is significantly enhanced, leading to the vaporization of certain elements during the cladding process and the formation of pore defects. Since laser cladding involves rapid heating and cooling, these pores are unable to escape in time and eventually accumulate at the top of the cladding layer. Therefore, an appropriate amount of TiBN can reduce the surface tension of the molten pool, enhance its fluidity, and effectively improve the structure and morphology of the cladding layer [20]. However, an excessive amount of TiBN results in large pore defects within the cladding layer.

Figure 4.

Cross-sectional morphology of Cu-TiBN gradient coatings with different contents of TiBN: (a) 0 wt.% TiBN; (b) 2 wt.% TiBN; (c) 4 wt.% TiBN; (d) 6 wt.% TiBN; (e) 8 wt.% TiBN. (Dotted lines: Interfacial layer between the Cu and Ni15 cladding layers).

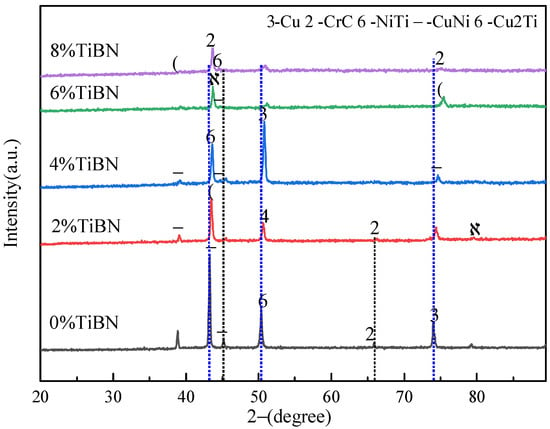

3.1.2. Microstructure of Cu-TiBN Gradient Coatings with Different Contents of TiBN

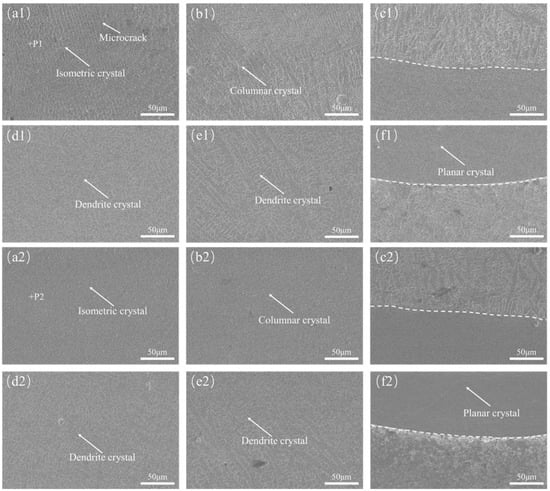

Figure 5 illustrates the microstructure of Cu-TiBN gradient coatings with varying TiBN contents. As shown, TiBN addition markedly transforms the cladding layer’s microstructure by refining grains and increasing morphological complexity. This effect is evident when comparing the pure copper to the 2 wt.% TiBN coating and becomes more pronounced at contents exceeding 4 wt.%.

Figure 5.

Overall microstructure of Cu-TiBN gradient coatings with different TiBN contents. (a) 0 wt.% TiBN; (b) 2 wt.% TiBN; (c) 4 wt.% TiBN; (d) 6 wt.% TiBN; (e) 8 wt.% TiBN. (Dotted lines: The middle part is the interface layer between the Cu and Ni15 cladding layer, and the bottom part is the interface layer between the Ni15 cladding layer and the steel substrate).

To investigate the effect of TiBN addition on the microstructure of the coating, the microstructure and morphology of the top, middle, bottom, and bonding interface of the cross-section of the Cu-TiBN gradient composite coating were examined, as shown in Figure 6 and Figure 7. Figure 6 presents the microstructure of the pure copper coating (a1–f1) and the 2 wt.% TiBN coating (a2–f2). The microstructure of the pure copper coating is similar to that of the 2 wt.% TiBN coating, with both Cu cladding layers exhibiting equiaxed grains at the top. However, some micro-cracks were observed in the Cu cladding layer. This phenomenon may be attributed to the high reflectivity of Cu to the laser, leading to excessive thermal stress during the cladding process, which results in micro-cracks. In contrast, no such cracks were found in the 2 wt.% TiBN coating. The microstructure at the middle of the Cu layer consists of columnar crystals with a certain preferred orientation. The crystal growth orientation is governed by the thermal gradient, which shifts perpendicularly to the growth direction with laser movement. Concurrently, the interfacial microstructure is refined due to the laser remelting effect during Cu layer deposition. This process remelts the Ni15 surface, forming a band of fine equiaxed crystals that serves as conclusive evidence of excellent metallurgical bonding between the Cu and Ni15 layers [21,22]. The Ni15 layer displays distinct zoning: planar crystals at the substrate interface, transitioning to dendrites upwards. This aligns with classical solidification theory, where the extreme temperature gradient (G) at the onset of cooling dictates planar growth, manifesting as a distinct bright band that evidences strong metallurgical bonding.

Figure 6.

Microstructure of top, middle, bottom and bonding interface of pure copper coating (a1–f1) and coating containing 2 wt.% TiBN (a2–f2). (Dotted lines: Interfacial layer between the Cu and Ni15 cladding layers).

Figure 7.

(a3–d3), (a4–d4) and (a5–d5) are the microstructures of the top, middle, bottom and bonding interface of the coatings with TiBN content of 4 wt.%, 6 wt.% and 8 wt.%, respectively. (Dotted lines: Interfacial layer between the Cu and Ni15 cladding layers).

When the TiBN content exceeds 4 wt.%, the microstructure of the cladding layer differs from that of the pure copper and 2 wt.% TiBN coatings, as shown in Figure 7. The bonding interface between Cu-TiBN and Ni15 cladding layer disappeared, and Cu-TiBN and Ni15 cladding layer were completely miscible. A common microstructural architecture, comprising columnar crystals in the upper regions and a dendritic-to-planar transition at the bottom, is observed across the 4–8 wt.% TiBN coatings, confirming robust interfacial bonding. The distinguishing effect of TiBN content is grain size, with a clear trend of refinement at higher additions. This is primarily caused by the role of TiBN particles as potent heterogeneous nucleation sites. Their presence enhances laser energy absorption and increases melt undercooling, which collectively elevate the nucleation rate and suppress grain coarsening, leading to a more refined microstructure.

EDS point analysis of the coatings (Table 3) was performed to investigate the elemental distribution. The data show an inverse relationship between TiBN content and Cu concentration at the coating top, with Ni content increasing accordingly. This elemental redistribution is caused by the TiBN particles, which enhance laser energy absorption, improve pool fluidity, and drive Marangoni convection, thereby entraining Ni from the transition layer. However, this enhanced convection and the increased ceramic content at higher TiBN levels (6 and 8 wt.%) also lead to pore formation, with EDS confirming these defects are enriched in Ni and B.

Table 3.

EDS results of positions 1–7.

In summary, the addition of TiBN is beneficial to improve the microstructure of the coating and can play a role in grain refinement. These changes in microstructure will lead to corresponding changes in mechanical properties.

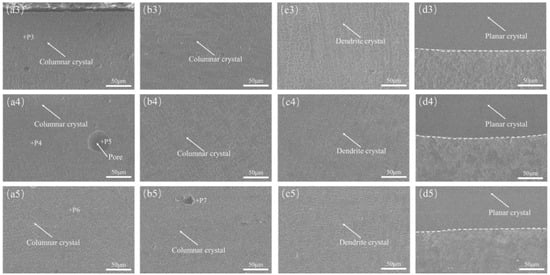

3.2. XRD Pattern Analysis of Cu-TiBN Gradient Coatings with Different Contents of TiBN

Figure 8 shows the XRD pattern analysis results of Cu-TiBN gradient coatings with varying TiBN contents. It can be observed that the phase composition of the Cu-TiBN gradient coatings changes with the increase in TiBN content. The pure copper coating without TiBN is mainly composed of Cu. With the addition of TiBN, the intensity of all Cu characteristic peaks gradually decreases. The three main peaks at (111), (200), and (220) shift to the right. This shift is attributed to the transformation of the primary phase from Cu to CuNi solid solution. Since the atomic radius of Ni is slightly smaller than that of Cu, the formation of the Cu-Ni solid solution results in a reduction in the lattice constant, leading to a decrease in the interplanar spacing. According to Bragg’s law (1), when Ni atoms replace Cu atoms in the Cu lattice, the diffraction angle increases. In the XRD pattern, the diffraction peaks of the Cu-Ni solid solution will shift towards higher angles compared to the Cu diffraction peaks. Additionally, new reinforcing phases, such as NiTi and Cu2Ti, also appear in the coating.

where is the X-ray wavelength; the interplanar spacing of crystal; diffraction angle. It was found in the experiment that under the extreme high temperature of laser cladding, TiBN ceramic particles decomposed, releasing highly active Ti. When the local concentration of Ti in the Cu melt exceeds its solid solution limit, the system will generate a huge chemical driving force to promote nucleation to reach equilibrium, and these free Ti will react with the copper melt. According to the binary phase diagram analysis of Ni-Ti and Cu-Ti, Ni and Ti, Cu and Ti began to react at 970° and 790°, respectively, to form NiTi and Cu2Ti phases. These changes indicate that as the TiBN content increases, the absorption of laser beam energy by the powder increases, thereby enhancing the fluidity of the molten pool. The Cu-TiBN and Ni15 transition layers promote the solid solution of Cu and Ni at high temperatures, leading to the formation of CuNi solid solution, NiTi, Cu2Ti, and other compounds. The overall improvement in surface properties is achieved through dispersion strengthening imparted by the TiBN particles. Phase analysis by XRD showed that the main diffraction peak remained stable around 44.5° for all coatings, with no detectable oxide phases, validating the effectiveness of the argon shielding in preventing oxidation during processing [23].

Figure 8.

XRD patterns of Cu-TiBN gradient coatings with different contents of TiBN. (Dotted lines: The Angle of the 0%TiBN characteristic peak).

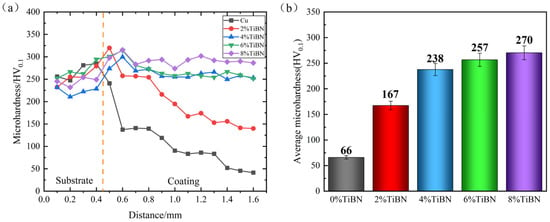

3.3. Micro-Hardness Analysis of Cladding Coating

Figure 9 demonstrates the cross-sectional hardness profiles of the Cu-TiBN composite coatings. The hardness shows a substantial improvement from 66 HV0.1 (pure Cu) with increasing TiBN content. This is directly linked to the microstructural refinement discussed earlier, confirming that the incorporated TiBN particles contribute to grain refinement strengthening.

Figure 9.

(a) The hardness of Cu-TiBN gradient coatings with different TiBN content; (b) Average hardness. (Dotted lines: The junction between the substrate and the cladding layer).

With the increase in TiBN content, the absorption of laser beam energy by cladding powder is enhanced. At the high temperature of laser irradiation, the Cu-TiBN and Ni transition layer are fully melted and CuNi solid solution, NiTi, Cu2Ti and other hard phases are formed in the coating, which plays a role in solid solution strengthening and dispersion strengthening. When the TiBN content exceeds 4 wt.%, the hardness of the coating increases significantly. At a TiBN content of 8 wt.%, the average hardness reaches 270 HV0.1.

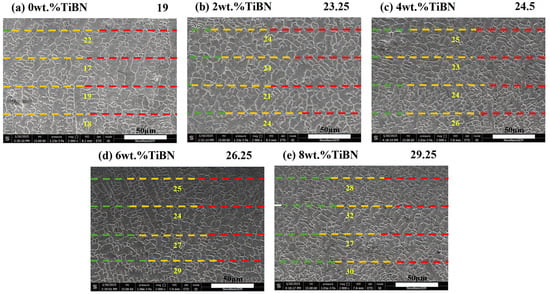

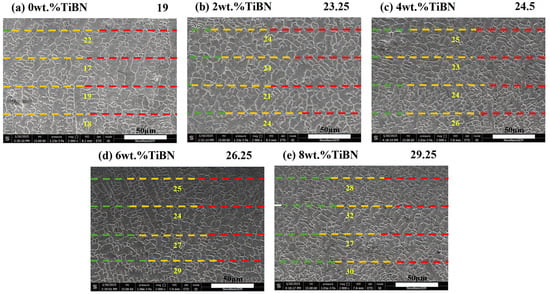

According to the ASTM E112 standard, we used the planar measurement method to test the grain size of the composite coatings with different TiBN contents. Four horizontal lines were taken in each composite coating to measure the number of grains passed through, and further the average grain number of each TiBN content composite coating was obtained (as show in Figure 10a–e. In the picture, the dotted line colors red, yellow, green and cyan respectively represent ten grain intervals. Starting from red on the right to the left, the average number of grains of each composite coating is shown in the upper right corner of the picture).

Figure 10.

The grain size of the composite coatings with different TiBN contents: (a) 0 wt.% TiBN; (b) 2 wt.% TiBN; (c) 4 wt.% TiBN; (d) 6 wt.% TiBN; (e) 8 wt.% TiBN. (In the picture, the dotted line colors red, yellow, green and cyan respectively represent ten grain intervals. Starting from red on the right to the left, the average number of grains of each composite coating is shown in the upper right corner of the picture).

In the formula: is the fine grain strengthening coefficient, is the specific surface energy, is the Petch slope, and , , and are constants.

It can be seen that when the grain size decreases, and increase, and decreases. This also means that the strength and toughness improve simultaneously. Therefore, when TiBN is added, the grain size is significantly reduced. With the increase in TiBN content, the grain size further decreases, which enhances the strength and toughness of the composite coating. Under the combined effect of the NiTi and Cu2Ti strengthening phases formed during the laser cladding process, the hardness of the composite coating is improved.

In conclusion, adding TiBN particles to the copper layer can enhance the overall hardness of the coating, and this reinforcing effect continues as the TiBN content increases.

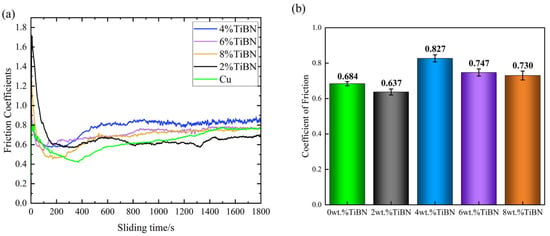

3.4. Analysis of Tribological Behavior of Cu-TiBN Gradient Coatings with Different Content of TiBN

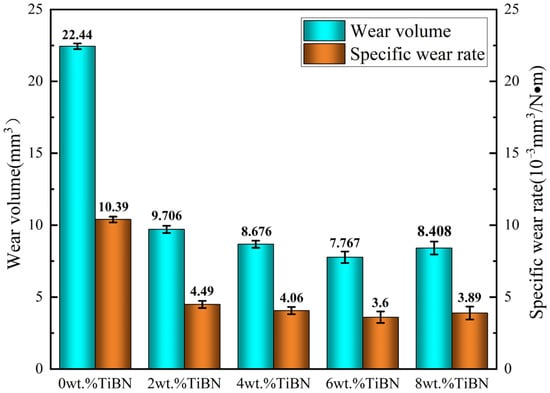

As depicted in Figure 11, the friction coefficient of the Cu-TiBN gradient coating exhibits a rapid decline in the initial stage, known as the run-in period. This decrease results from the progressive conformability of the contacting surfaces, as the actual contact area increases until a steady state is achieved. After 10 min, the friction coefficient of all samples began to stabilize, and the samples entered the stable wear stage [24]. As shown in Figure 11a, with the addition of TiBN, the friction coefficient of the cladding layer first increases and then decreases. The average friction coefficients of the composite coatings, as presented in Figure 11, are 0.684, 0.637, 0.827, 0.747, and 0.730, respectively. A distinct minimum in the average friction coefficient (0.637) is observed at 2 wt.% TiBN, which is 6.87% lower than the pure copper reference. This trend is governed by the microstructure-property relationship: optimal TiBN addition enhances laser absorption and promotes uniform dispersion strengthening without compromising the toughness of the copper matrix. Beyond this content, the friction coefficient increases, likely due to microstructural heterogeneity. When the copper cladding layer is in contact with the friction surface, a metal transfer film similar to solid lubricant will be formed under high temperature or high pressure conditions, which can reduce the friction coefficient [25]. As the TiBN content increases, the primary composition of the cladding layer gradually shifts from Cu to a CuNi solid solution. Compared to pure Cu, although the hardness increases, it cannot form a self-lubricating slip layer on the friction interface. Additionally, the formation of intermetallic compounds such as NiTi and Cu2Ti increases the brittleness of the coating, limiting or even negating the lubrication effect. The coefficient of friction of pure copper coatings without TiBN increases over time. The inferior tribological performance of the pure copper coating, characterized by a rising friction coefficient and high wear volume (22.44 × 10−9 m3), is likely due to abrasive wear induced by hard copper oxide debris. In contrast, the addition of TiBN significantly enhances wear resistance (Figure 12), reducing the wear volume to a minimum of 7.77 × 10−9 m3 at 6 wt.% TiBN. This corresponds to a substantially lower wear rate, calculated via Archard’s law [26], demonstrating the effectiveness of TiBN in improving the coating’s durability.

is the wear rate; is the amount of wear (m3); is the applied normal load (N); is the friction distance (m).

The non-monotonic trend in wear rate (Figure 12) is a direct consequence of the evolving microstructure and mechanical properties with TiBN content. An appropriate amount of TiBN enhances hardness and thus wear resistance via dispersion strengthening. However, an excessively high content may introduce brittleness or promote defect formation, ultimately degrading the coating’s tribological performance despite the higher hardness.

Figure 11.

(a) Friction coefficient curve of the coating; (b) Average friction coefficient.

Figure 12.

Wear volume and wear rate of Cu-TiBN gradient coatings with different TiBN contents after 30 min wear under 100 g normal load.

3.5. Wear Trace and Wear Mechanism of Cu-TiBN Gradient Coating with Different Content of TiBN

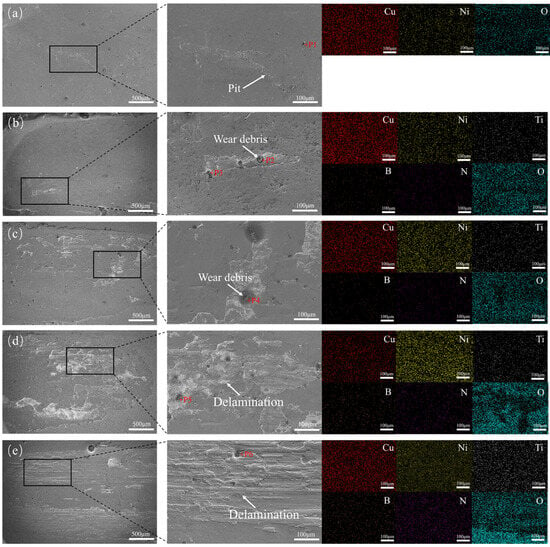

SEM analysis of the wear tracks (Figure 13) was conducted to link the wear mechanisms to TiBN content. The smooth topography of the unreinforced copper coating confirms its high ductility, which governs its initial wear behavior. Under the friction stress, it shows a slight plastic deformation, with only a small amount of peeling pits and wear debris. By analyzing the EDS point scanning combination and surface scanning results of the 1 point shown in Table 4, it can be seen that there is O element. The presence of the O element can be attributed to the oxidation process of the contact surface during friction and wear. The wear debris is mainly CuO compound, indicating that the surface of the pure copper coating mainly undergoes adhesive wear and accompanied by oxidative wear. Combined with the above hardness analysis, it can be seen that the hardness of the pure copper coating is low, and the wear resistance of the coating is limited. The surface of the coating containing 2 wt.% TiBN is smooth and flat, and slight plastic deformation occurs. Combined with the EDS point scanning at 2 and 3 points shown in Table 4, it is found that the wear debris is composed of Cu, Ni, O and other elements. Combined with the EDS surface scanning results, it is found that Ti, B, N and other elements are evenly distributed in the coating, indicating that TiBN ceramic particles can play a role in dispersion strengthening in the coating. Based on the above observations, it can be inferred that the wear mechanism transitions from adhesive wear to slight abrasive wear, accompanied by oxidative wear. As the TiBN content increases, the coating undergoes more severe plastic deformation and experiences repeated deformation under the influence of friction cycles. Based on the above microstructure and XRD spectrum analysis, it can be observed that as the TiBN content increases, CuNi solid solution and intermetallic compounds such as Cu2Ti and NiTi are formed in the coating. This leads to a significant increase in the brittleness of the coating, reducing its deformation resistance, making it more prone to delamination along the interface during the wear process. The progressive Ni enrichment and Cu depletion indicated by EDS (Points 4–6, Table 4) provide direct evidence of enhanced laser energy absorption and increased Cu-Ni mutual solubility at higher TiBN contents. The prevalence of Cu-Ni solid solution in the debris collectively indicates that the primary wear mechanism for the 4–8 wt.% TiBN coatings is a combination of abrasive and oxidative wear.

Figure 13.

Local microstructure and EDS mapping results of wear traces and wear debris of Cu-TiBN gradient coatings with different contents of TiBN at room temperature: (a) 0 wt.% TiBN; (b) 2 wt.% TiBN; (c) 4 wt.% TiBN; (d) 6 wt.% TiBN; (e) 8 wt.% TiBN. (The red font indicates the specific positions corresponding to points 1 to 6 in Table 4).

Table 4.

EDS results of positions 1–6.

In summary, a pivotal shift in the dominant wear mechanism is induced by TiBN addition. Adhesive wear, accompanied by oxidation, governs the material removal in the pure copper and 2 wt.% TiBN coatings. In contrast, abrasive wear becomes the primary mechanism for the 4–8 wt.% TiBN coatings, with oxidative wear playing a secondary role.

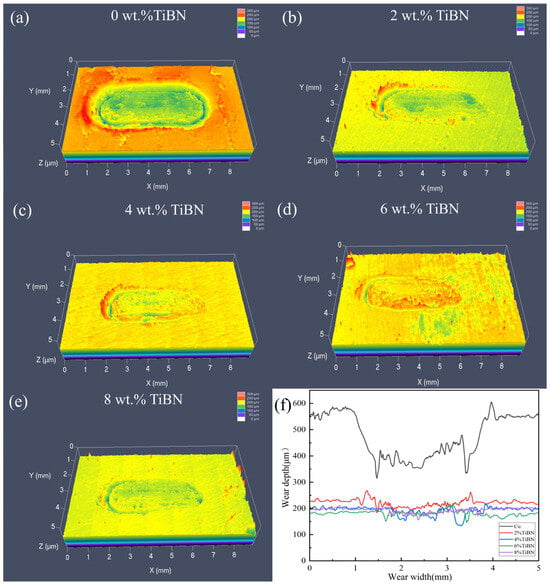

The three-dimensional wear topography and two-dimensional scar profiles characteristic of the five coatings are compared in Figure 14. Among them, the pure copper coating shows a relatively large wear depth and width, and there is a considerable accumulation of debris at the wear edge. The central area presents obvious depressions, and the wear is quite severe. After adding TiBN ceramic particles, the wear width and depth of the coating were significantly reduced compared with those before the addition. The wear depth curves in Figure 14f reveal a trend toward greater stability and shallower pits with higher TiBN content. Notably, the 8 wt.% TiBN coating shows the steadiest profile, underscoring the role of TiBN in improving the coating’s resistance to plastic deformation. This results in a notable reduction in both wear scar width and depth, coupled with superior post-wear surface uniformity.

Figure 14.

After the Cu-TiBN gradient coating with different TiBN content was worn for 30 min under normal load of 100 g, the three-dimensional wear morphology (a) 0 wt.% TiBN, (b) 2 wt.% TiBN, (c) 4 wt.% TiBN, (d) 6 wt.% TiBN, (e) 8 wt.% TiBN and (f) two-dimensional wear scar profile in the middle of the wear track.

4. Conclusions

In this investigation, Cu-TiBN gradient coatings with varying TiBN contents were fabricated on 45 steel substrates via laser cladding technology. After comprehensive testing and analysis of each composite coating, the following conclusions were drawn:

- (1)

- The friction coefficient of the composite coating underwent a multi-stage evolution with TiBN content, characterized by an initial decline, a subsequent rise, and a final reduction. The initial stage, exemplified by the 2 wt.% TiBN coating, is associated with a microstructure that retained a distinct Cu/Ni15 interface without significant morphological change, suggesting this content optimizes particle dispersion without altering the fundamental coating architecture. However, when more than 4 wt.% TiBN was added, the Cu-TiBN and Ni15 layers were completely fused, and the porosity defects in the cladding layer increased. The addition of TiBN led to a noticeable refinement of the grains, and these microstructural changes resulted in corresponding variations in the mechanical properties.

- (2)

- The main diffraction peaks of all coatings are generally located around 44°, with relatively stable phases and no oxide diffraction peaks present, indicating that no oxidation reaction occurred during the laser cladding process. As the TiBN content increases, the intensity of all Cu characteristic peaks gradually decreases. The primary phase transitions from Cu to CuNi solid solution, with the appearance of hard phases such as NiTi and Cu2Ti.

- (3)

- A substantial increase in microhardness was observed with the addition of TiBN, culminating in a value of 270 HV0.1 at 8 wt.% content. This peak hardness, which is 309% greater than that of the pure copper coating (66 HV0.1), is primarily attributed to the dispersion strengthening effect of the TiBN particles.

- (4)

- The evolution of the friction coefficient with TiBN content is characterized by an initial increase followed by a decrease, with the 2 wt.% coating yielding the minimum value of 0.637 (a 6.87% improvement over pure copper). Across this composition range, the material removal is primarily governed by the synergistic action of abrasive and oxidative wear at room temperature.

Author Contributions

F.Z. Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing. S.L. (Sen Lu) Formal analysis. J.Z. Data curation, Formal analysis, Software. B.C. Investigation, Project administration. S.L. (Shuangyu Liu) Supervision, Funding acquisition. Q.Z. Methodology, Resources, Validation. P.L. Conceptualization. B.W. Investigation, Project administration, Resources. Y.L. Investigation, Data curation, Validation. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is supported by the Innovative and Entrepreneurial Talent Foundation of Jiangsu Province (No. JSSCRC2021545), Yancheng Science and Technology Program Special Fund—Policy Guidance Program—International Science and Technology Cooperation Project (Ycgh003) and Funding for School-Level Research Projects of the Yancheng Institute of Technology (No. XJR2023003).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Binhua Wang was employed by the company Jiangsu Global Laser Box Digital Tech Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Kim, S.W.; Kim, G.Y.; Lee, Y.H.; Jang, J.H.; Lee, C.W.; Woo, J.H.; Yoon, S. Electrochemical corrosion behavior of atmospheric-plasma-sprayed copper as a coating material for deep geological disposal canisters. Nucl. Eng. Technol. 2023, 55, 4032–4038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.F.; Qu, K.; Yang, J.L. Fatigue performance of Q355B steel substrate treated by grit blasting with and without subsequent cold spraying with Al and Cu. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2021, 405, 126662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, A.; Le Pen, C.; Archambeau, C.; Reniers, F. Use of a PECVD-PVD process for the deposition of copper containing organosilicon thin films on steel. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2009, 256, S82–S85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elrefaey, A.; Wojarski, L.; Tillmann, W. Preliminary Investigation on Brazing Performance of Ti/Ti and Ti/Steel Joints Using Copper Film Deposited by PVD Technique. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2012, 21, 696–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nghia, T.V.; Sen, Y.; Anh, P.T. Microstructure and properties of Cu/TiB2 wear resistance composite coating on H13 steel prepared by in-situ laser cladding. Opt. Laser Technol. 2018, 108, 480–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, B.X.; Xue, Y.P.; Wang, X.M.; Ding, Y.H.; Fu, K.; Zhong, C.; Gui, W.Y.; Luan, B.L. On the elemental segregation and melt flow behavior of pure copper laser cladding. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2023, 452, 129085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Kumar, M.; Sodhi, G.P.S.; Buddu, R.K.; Singh, H. Development of thick copper claddings on SS316L steel for In-vessel components of fusion reactors and copper-cast iron canisters. Fusion Eng. Des. 2018, 128, 126–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, S.; Paul, C.P.; Jinoop, A.N.; Rai, A.K.; Bindra, K.S. Laser Directed Energy Deposition based Additive Manufacturing of Copper: Process Development and Material Characterizations. J. Manuf. Process. 2020, 58, 984–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.J.; Pang, M. Research on the effect of IN718 transition layer on the performance of laser cladding Co06 coating on RuT450. J. Mater. Sci. 2023, 58, 9038–9059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, K.N.; Lu, H.F.; Luo, K.Y.; Cui, C.Y.; Yao, J.H.; Xing, F.; Lu, J.Z. Effects of Ni25 transitional layer on microstructural evolution and wear property of laser clad composite coating on H13 tool steel. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2020, 402, 126488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Z.W.; Chen, C.Y.; Wang, C.Y.; Zhou, Z.K.; Zhou, J.; Long, Y. Effect of different laser wavelengths on laser cladding of pure copper. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2023, 454, 129181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, L.; Cheng, M.Y.; Fu, G.Y.; Wei, C.; Shi, T.; Shi, S.H. Annular laser cladding of CuPb10Sn10 copper alloy for high-quality anti-friction coating on 42CrMo steel surface. Opt. Laser Technol. 2023, 158, 108878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, R.; Li, S.; Misra, R.D.K.; Kondoh, K.; Yang, Y. Role of W in W-coated Cu powder in enhancing the densification-conductivity synergy of laser powder bed fusion built Cu component. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2023, 322, 118169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.P.; Gan, B.; Tan, J.; Wu, J.; Chen, S.H.; Dong, J.; Ma, Z.Q. The enhancement of laser absorptivity and properties in laser powder bed fusion manufactured Cu-Cr-Zr alloy by employing Y2O3 coated powder as precursor. J. Alloys Compd. 2022, 927, 167111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.Y.; Lu, P.; Zhang, Q.T.; Hong, J. Preparation of (B,N)-codoped TiO2 micro-nano composite powder using TiBN powder as a precursor. Ceram. Int. 2022, 48, 10079–10085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.P.; Zhu, L.H.; Huang, Q.W.; He, Z.C. The light absorption enhancement of nanostructured carbon-based coatings fabricated by high-voltage electrostatic spraying technique. Opt. Mater. 2022, 133, 112902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.P.; Zhu, L.H.; Huang, Q.W.; He, Z.C. Effect of carbon nanotubes and TiN nanoparticles on light absorption property of nanostructured carbon-based coatings fabricated by high-voltage electrostatic spraying technique. Opt. Mater. 2024, 150, 115172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, B.X.; Xue, Y.P.; Luan, B.L. Investigation on the interface microstructure and phase composition of laser cladding pure copper coating. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2024, 494, 131408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.Y.; Kong, X.Y.; Lu, P.; Zhang, F.L.; Zhang, J.Q.; Wang, B.H.; Liu, F.D.; Wang, X.; Hong, J. Study on microstructure and properties of laser cladding Cu/10Sn5Bi alternating stripe coating. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2025, 337, 130601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Li, R.Y.; Feng, A.X.; Feng, H.B. Effect of rare earth La2O3 particles on structure and properties of laser cladding WC-Ni60 composite coatings. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2024, 479, 130569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.Z.; Hu, Y.B.; Zhang, D.Z.; Cong, W.L. Laser remelting of CoCrFeNiTi high entropy alloy coatings fabricated by directed energy deposition: Effects of remelting laser power. Opt. Laser Technol. 2023, 158, 108871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.F.; Xu, Y.B.; Liao, B.Q.; Sun, Y.J.; Dai, X.Q.; Yang, J.X.; Li, Z.Y. Effect of laser remelting on microstructure and properties of WC reinforced Fe-based amorphous composite coatings by laser cladding. Opt. Laser Technol. 2018, 103, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Li, Y.J.; Wang, J.; Ma, Q.S. In-situ synthesized Ni-Zr intermetallic/ceramic reinforced composite coatings on zirconium substrate by high power diode laser. J. Alloys Compd. 2015, 624, 234–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, J.W.; Liang, H.; Zhang, A.J.; He, J.Y.; Meng, J.H.; Lu, Y.P. Tribological behavior of an AlCoCrFeNi2.1 eutectic high entropy alloy sliding against different counterfaces. Tribol. Int. 2021, 153, 106599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seynstahl, A.; Köbrich, M.; Rosnitschek, T.; Göken, M.; Tremmel, S. Enhancing the lifetime and vacuum tribological performance of PVD-MoS2 coatings by nitrogen modification. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2024, 477, 130343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.L.; Gu, D.D. Parametric analysis of thermal behavior during selective laser melting additive manufacturing of aluminum alloy powder. Mater. Des. 2014, 63, 856–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).